Henock v. Bergtraum Brief of Intervenors-Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Henock v. Bergtraum Brief of Intervenors-Respondents, 1971. 6077a9f9-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/879192c7-9c73-4615-b901-ce81ebfb2b75/henock-v-bergtraum-brief-of-intervenors-respondents. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

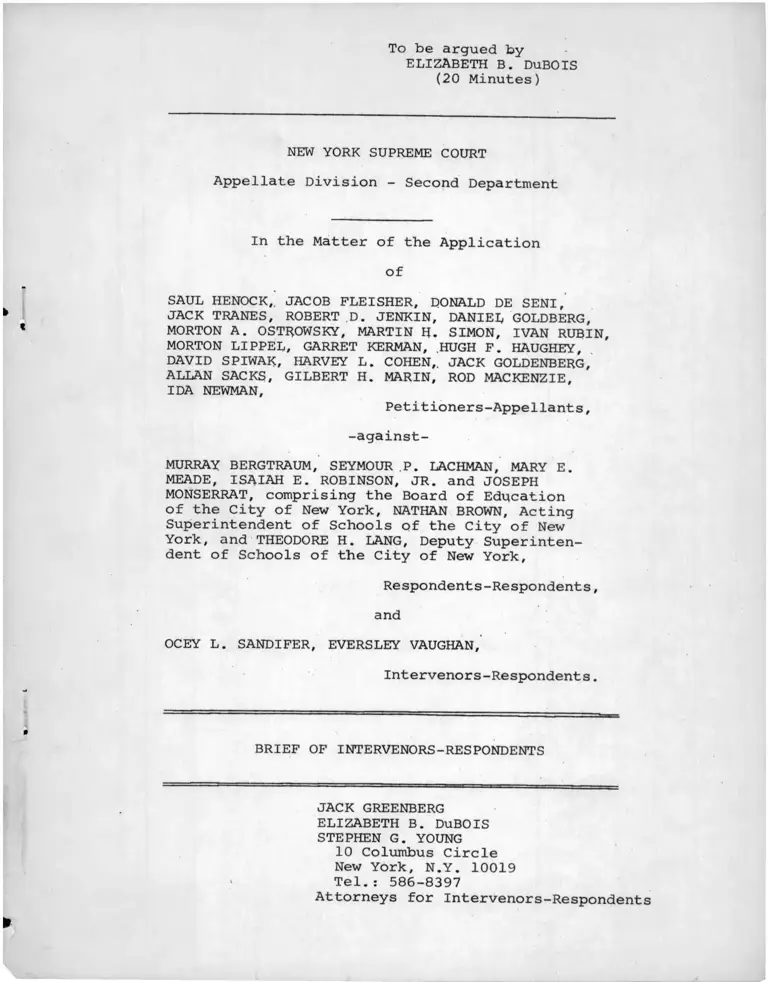

To be argued by

ELIZABETH B. DuBOIS (20 Minutes)

NEW YORK SUPREME COURT

Appellate Division - Second Department

In the Matter of the Application

of

SAUL HENOCK,. JACOB FLEISHER, DONALD DE SENI,

JACK TRANES, ROBERT D. JENKIN, DANIEL GOLDBERG,

MORTON A. OSTROWSKY, MARTIN H. SIMON, IVAN RUBIN,

MORTON LIPPEL, GARRET KERMAN, .HUGH F. HAUGHEY,

DAVID SPIWAK, HARVEY L. COHEN,. JACK GOLDENBERG,

ALLAN SACKS, GILBERT H. MARIN, ROD MACKENZIE,IDA NEWMAN,

Petitioners-Appellants,

-against-

MURRAY BERGTRAUM, SEYMOUR P. LACHMAN, MARY E. MEADE, ISAIAH E. ROBINSON, JR. and JOSEPH

MONSERRAT, comprising the Board of Education

of the City of New York, NATHAN BROWN, Acting

Superintendent of Schools of the City of New

York, and THEODORE H. LANG, Deputy Superintendent of Schools of the City of New York,

Respondents-Respondents,

and

OCEY L. SANDIFER, EVERSLEY VAUGHAN,

Intervenors-Respondents.

BRIEF OF INTERVENORS-RESPONDENTS

JACK GREENBERG

ELIZABETH B. DuBOIS STEPHEN G. YOUNG

10 Columbus Circle New York, N.Y. 10019

Tel.: 586-8397

Attorneys for Intervenors-Respondents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Facts.......................................... 1

Questions Presented............................ 6

Pertinent Constitutional and

Statutory Provisions......................... 8

Point I

The court below correctly found that

the Legislature's amendment to Section

2573 subdivision 10 of the Education

Law was a valid exercise of legislative

authority under Article V Section 6 of

the New York State Constitution, be

cause it was neither arbitrary nor

unreasonable........................... 18

Point II

The court below correctly found that

petitioners had no vested right to

have appointments, on a ranked competi

tive basis or otherwise, and that the

legislative change in Section 2573

subdivision 10 had no retroactive

effect................................. 34

Point III

The court below correctly found that

petitioners lost none of their rights

to veterans' preferences as a result either of the change in Section 2573

subdivision 10 or in the actions of

the Board of Education................. 37

Point IV

The court below correctly found that

petitioners were deprived of no contractual rights as a result of

any action by the Legislature or the

Board of Education......... ............ 39

Conclusion 40

FACTS

Having ascertained that the public school

system of New York City was in serious difficulty, the

New York Legislature, commencing in 1967, enacted a

series of reform measures. Three major bills were

1/passed during the course of three consecutive sessions.

Taken together, these measures effected a step-by-step

major restructuring and decentralizing of the system's

operations. A key focus of this legislation was person

nel practices: particularly, the licensing and appoint

ing of teachers and supervisors. It is fair to say that

this aspect of decentralization was among the most con

troversial, particularly in view of the altercations

which came to surround the Ocean Hill-Brownsville

experimental district. Indeed, the extent to which

this issue was subject to public scrutiny can hardly

be understated.

Thus, it was in the context of the developing

controversy over decentralization that the Board of

Examiners announced on April 8, 1968, an examination

for assistant principal of junior high school, to commence

1/ Laws of 1967, Chapter 484; Laws of 1968, Chapter 568;

Laws of 1969, Chapter 330.

2

the following September 3. This announcement (A. 58)

did not specify whether the examination would result in

a ranked competitive list, or simply qualifying ones.

Indeed, the portion of the announcement dealing with

grading dealt with only the criteria for passing the

examination. The appellants and intervenors-appellees

herein were among those admitted to the examination.

The conduct of the examination was completed

in or about early 1969, and a list of successful candi

dates pursuant thereto was promulgated by the Board of

Examiners on July 15, 1969. On July 25, 1969, respondent

Theodore H. Lang, Deputy Superintendent of Schools for

Personnel, sent a letter to all those on the list (A. 61)

informing them, inter alia, that names thereon were pub

lished in ranked order and therefore that appointments

would be made according to relative standing. However,

on November 19, 1969, respondent Lang sent a subsequent

letter to all such persons informing them that, pursuant

to a communication from the Corporation Counsel, the list

would be a Qualifying Eligible List rather than a Ranked

Competitive one. Because both these letters ware written

long after the examination itself had been completed,

2/

2/ Numbers in parentheses, unless otherwise indicated,

refer to pages in appellants' appendix.

3

neither of them had any effect either on the execution

of the examination or upon the obligations of the Board

of Education. Nor can it be said that candidates relied

upon these letters in their conduct in the examination.

After the examination had been completed, but

before the list had been promulgated, the Legislature

had passed, and the Governor had approved, Chapter 330

of the Laws of 1969, popularly known as the Decentrali

zation Law. This Act, inter alia, amended Section 2573

subdivision 10 of the Education Law by deleting the

supervisory service of the New York City public schools

from the class from which appointments must be made from

lists on a ranked competitive basis. Also, the Act added

§§ 2590-j(4)(b) and (d) to the Education Law to make clear

that supervisory appointments would be made from qualify-

2/ing eligible lists under the new decentralized system.

Petitioners-appellants subsequently brought

this action, contending that the amendment to said Section

2573 subdivision 10 violated Article V Section 6 of the

3/ A ranked competitive list is one in which the names

■thereon are listed in an order corresponding to the nu

merical scores achieved by the candidates. Under Sec. 2573 Subd. 10, prior to its amendment in 1969, appointments to

supervisory positions were required to be from among the top

three names on the list. A qualifying eligible is one in

which there is no ranked listing, so that an appointee may

be anyone on the list.

4

New York State Constitution. Said Article V Section 6

mandates that appointments and promotions in the civil

service be made on the basis of merit and fitness to be

determined, as far as practicable, by examination which,

as far as practicable, is to be competitive. Petitioners-

appellants also contended that this statutory change was

being applied retroactively by respondent Board of Education,

and questioned the propriety of such alleged application.

Petitioners-appellants further contended that

certain of their number were entitled to veterans' pre

ferences in the grading of the examination under Article V

Section 6 of the New York State Constitution, and that the

statutory amendment to Section 2573 subdivision 10 of the

Education Law, and respondent Board of Education's imple

mentation of same, were depriving such petitioners of

these preferences.

Intervenors-respondents are two individuals

whose names appear on the list but who opposed the peti

tion. They were granted intervention on the date of oral

argument in the court below, April 2, 1970.

The court below, in a factually detailed and

well reasoned opinion (A. 10-21) rejected the petition

on every point. It held that the amendment to Section 2573

subdivision 10 was a valid exercise of legislative power

(A. 16); and that it in no way affected any rights of

5

petitioners (A. 17). The court also ruled that none of

petitioners had lost their rights to use veterans bonus

on civil service examinations (A. 19); and the petitioners

paying of an examination fee did not give rise to any

contractual rights (A. 19).

6

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does the amendment to Section 2573 subdivision

10 of the Education Law, which removed the supervisory-

service of the New York City public school system from

the category of positions in such system for which re

commendation for appointment must be from the first three

persons on appropriate ranked competitive lists, violate

the provisions of Article V Section 6 of the New York

State Constitution? The court below answered in the

negative.

2. Did appellants gain any right to an appoint

ment, on a competitive basis or otherwise, to the posi

tion of junior high school assistant principal, by

virtue of their having taken and passed an examination

for such position? The court below answered in the

negative.

3. Did appellants lose any rights to veterans'

preferences, as provided in Article V Section 6 of the

New York State Constitution, either by the amendment to

Section 2573 subdivision 10 of the Education Law, or by

any action of any of respondents herein pursuant thereto?

The court below answered in the negative.

4. Were appellants deprived of any contractual

rights as a result of the amendment to Section 2573

subdivision 10 of the Education Law or by any action

of any of respondents herein pursuant thereto? The

court below answered in the negative.

7

8

PERTINENT CONSTITUTIONAL AND

STATUTORY PROVISIONS________

Article V Section 6 of the Constitution

of the State of New York reads as follows:

"§6. [Civil service'; veteran's preference.] - Appointments and

promotions in the civil service

of the state and all of the civil

divisions thereof, including

cities and villages, shall be

made according to merit and fit

ness to be ascertained, as far as practicable, by examination

which, as far as practicable,

shall be competitive; provided,

however, that any member of the

armed forces of the United States

who served therein in time of

war, who is a citizen and resident

at the time of his entrance into

the armed forces of the United States and was honorably discharged

or released under honorable circum

stances from such service, shall be

entitled to receive five points additional credit in a competitive

examination for original appoint

ment and two and one-half points additional credit in an examination

for promotion or, if such member

was disabled in the actual perform

ance of duty in any war, is receiv

ing disability payments therefor

from the United States veterans administration, and his disability

is certified by such administration

to be in existence at the time of his application for appointment or

promotion, he shall be entitled to

receive ten points additional credit

in a competitive examination for

9

original appointment, and five

points additional credit in an

examination for promotion.Such additional credit shall be

added to the final earned rating

of such member after he has

qualified in an examination and

shall be granted only at the

time of establishment of an eligible

list. No such member shall receive

the additional credit granted by

this section after he has received

one appointment, either original entrance or promotion, from an

eligible list on which he was al

lowed the additional credit granted by this section."

10

Prior to the amendment of April 30, 1969,

Section 2573, subdivision 10 of the Education Law of

the State of New York read in part as follows:

"10. In a city having a population

of one million or more, recommendations

for appointment to the teaching and supervising service, except for the

position of superintendent of schools,

associate superintendent or assistant

superintendent, or director of a

special branch, principal of or teacher

in a training school, or principal of

a high school, or administrative assistant in a high school, or

assistant administrative director,

shall be from the first three persons

on appropriate eligible list prepared

by the board of examiners."

Section 2573, subd. 10 of the Education Law

as amended, Laws of 1969, Chapter 330, reads in part as

follows:

"10. In a city having a population

of one million or more, recommenda

tions for appointment to the teaching

service shall be from the first three

persons on appropriate eligible lists

prepared by the board of examiners...."

11

" The interim board of education

shall prepare a tentative district

ing plan defining the boundaries

of the community districts and the

number of members on each community

board. No community district shall

contain less than twenty thousand

pupils in average daily attendance

in the schools under its jurisdiction nor shall the boundaries of any such

district cross county lines, provided

however, that residents of the county

of New York in school district ten as

it existed prior to the implementation of this paragraph, shall continue to

remain in school district ten as such

district is comprised pursuant to the

implementation of this paragraph.

There shall be no less than thirty

nor more than thirty-three community

districts."

Education Law Section 2590-b 2(b)

12

Education Law Section 2590-j subd. 4

"(b) The chancellor shall appoint and

assign all supervisory personnel for all

schools and programs under the jurisdic

tion of the city board from persons on qualifying eligible lists.

"(d) Each community board shall appoint

and assign all supervisory personnel

for all schools and programs under its

jurisdiction from persons on qualifying eligible lists.

"(e) All persons on an existing competi

tive eligible list for elementary school

principal shall be appointed to such

position prior to April first, nineteen hundred seventy.

"(f) All future eligible lists established pursuant to this section

shall remain in force and effect for

a period of four years, and no appointments shall be made from any eligible

list unless every such list promulgated prior thereto shall be exhausted or

expired, whichever first occurs."

13

Education Law Section 2590-e

"Each community board shall have

all the powers and duties, vested by law in, or duly delegated to,

the local school board districts

and the board of education of the

city district on the effective

date of this article, not incon

sistent with the provisions of

this article and the policies es

tablished by the city board, with

respect to the control and operation

of all pre-kindergarten, nursery, kindergarten, elementary, intermediate and junior high schools

and programs in connection there

with in the community district...."

14

Civil Service Law provisions

Section 35:

"The civil service of the state

and each of its civil divisions

shall be divided into the

classified and unclassified ser

vice. The unclassified service

shall comprise the following:...

(g) All persons employed by any

title whatsoever as members of

the teaching and supervisory staff

of a school district, board of cooperative educational services

or county vocational education

and extension board, as certified

to the state commission by the commissioner of education. The

commissioner of education shall

prescribe qualifications for

appointment for all classes of

positions so certified by him,

and shall establish specifications

setting forth the qualifications

for and the nature and scope of the

duties and responsibilities of such

positions."

Section 50:

" Application fees, (a) Every appli

cant for examination for a position

in the competitive or non-competitive

class, or in the labor class when

examination for appointment is required, shall pay a fee to the civil service

department or appropriate municipal

commission at a time determined by it.

Such fees shall be dependent on the

minimum annual salary announced for

the position, as follows: (1) on

salaries of less than three thousand

dollars per annum, a fee of two dollars;

(2) on salaries of more than three

thousand dollars per annum, a fee of

three dollars; (3) on salaries of more

15

than four thousand dollars and not

more than five thousand dollars per

annum, a fee of four dollars; and (4)

on salaries of more than five thousand

dollars per annum, a fee of five

dollars. If the compensation of a

position is fixed on any basis other than an annual salary rate, the appli

cant shall pay a fee based on the

annual compensation which would other

wise be payable in such position if the

services were required on a full time

annual basis for the number of hours per

day and days per week established by law

or administrative rule or order. Fees

paid hereunder by an applicant whose

application is not approved may be

refunded in the discretion of the state

civil service department 01 of the

appropriate municipal commission.

"(b) Notwithstanding the provisions of

paragraph (a) of this subdivision, the

state civil service department, subject

to the approval of the director of the

budget, a municipal commission, subject

to the approval of the governing board

or body of the city or county, as the

case may be, or a regional commission

or personnel officer, pursuant to

governmental agreement, may elect to

waive application fees, or to abolish

fees for specific classes of positions

or types of examinations or candidates,

or to establish a uniform schedule or

reasonable fees different from those

prescribed in paragraph (a) of this

subdivision, specifying in such schedule

the classes of positions or types of

examinations or candidates to which such

fees shall apply; provided, however,

that only the civil service department,

with the approval of the director of the

budget, shall have authority to waive

application fees or establish a different

schedule of fees for any examinations

16

prepared and rated by the civil

service department for positions

under the jurisdiction of a municipal commission."

Section 85, subd. 4.:

"Use of additional credit.

"(a) Except as herein otherwise

provided, no person who has received

a permanent original appointment or

a permanent promotion in the civil

service of the state or of any city

or civil division thereof from an

eligible list on which he was allowed

the additional credit granted by this

section, either as a veteran or dis

abled veteran, shall thereafter be

entitled to any additional credit

under this section either as a veteran or a disabled veteran.

"(b) Where, at the time of establish

ment of an eligible list, the position

of a veteran or disabled veteran on such list has not been affected by the

addition of credits granted under this

section, the appointment or promotion

of such veteran or disabled veteran,

as the case may be, from such eligible

list shall not be deemed to have been

made from an eligible list on which he

was allowed the additional credit granted by this section.'(c) If, at the time of certification of names fron an eligible list, a vet

eran or disabled veteran is reached for

certification and certified in the same

relative standing among the eligibles

whose names then remain on such list as

if he had not been granted the addition

al credits provided by this section, his

appointment upon such certification shall

not be deemed to have have been made from

an eligible list on which he was allowed such additional credits.

17

"(d) Where a veteran or disabled

veteran has been originally ap

pointed or promoted from an eli

gible list on which he was allowed

additional credit, but such appoint

ment or promotion is thereafter

terminated either at the end of

the probationary term or by resig

nation at or before the end of the

probationary term, he shall not be

deemed to have been appointed or

promoted, as the case may be, from

an eligible list on which he was allowed additional credit, and

such appointment or promotion shall

not effect his eligibility for

additional credit in other examinations . "

18

POINT I

THE COURT BELOW CORRECTLY FOUND

THAT THE LEGISLATURE'S AMENDMENT

TO SECTION 2573 SUBDIVISION 10

OF THE EDUCATION LAW WAS A VALID

EXERCISE OF LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY

UNDER ARTICLE V SECTION 6 OF

THE NEW YORK STATE CONSTITUTION,

BECAUSE IT WAS NEITHER ARBITRARY

NOR UNREASONABLE.

The essence of appellants' constitutional

claim is that the Legislature violated Article V

Section 6 of the New York State Constitution when

it altered the method of appointing personnel to the

supervisory service of the New York City public schools.

The alteration consisted of changing the nature of

civil service lists for these positions from 'ranked

competitive' to 'eligible qualifying'. The effect of

the change was that, whereas previously any appointee

to a vacancy had to be one of the top three persons on

a list, now such appointee could be anyone on a list.

Article V Section 6 mandates that appoint

ments and promotions in the civil service be made on

the basis of merit and fitness, to be determined, as

far as practicable, by examination, which, as far as

practicable, is to be competitive. As far back as

1898, four years after this provision was adopted -

originally as Article V Section 9 of the 1894 Consti-

19

tution, the Court of Appeals set forth its meaning in

People ex rel. Sweet v. Lyman, 157 N.Y. 368 at 375:

"It then declares that merit and

fitness shall be ascertained by

examinations, and also the extent

to which examinations are to control

is declared to be only so far as

practicable. This language clearly

implies that it is not entirely

practicable to fully determine them

in that way. it was the purpose of

its framers to declare those two

principles, and leave their appli

cation to the discretion of the

Legislature." (Emphasis added.)

Some years later, in discussing this constitu

tional provision, Judge Cardozo commented that what it

requires is that the Legislature act reasonably in clas

sifying civil service positions. He stated in Ottinger

v. Civil Service Commission, 204 N.Y. 435 and pp.440-441

"...It [the Legislature] may adopt

some other agency, and even classify

for itself, if its classification

can reasonably be regarded as genuine

endeavor to extend the constitutional

test to the limit of the practicable

...The Legislature retains the power

among means appropriate to the end,

but choice depends upon reason, not caprice."

In Meenagh v. Dewey, 286 N.Y. 292, 306 (1941),

the Court of Appeals upheld the classification, by the

State Civil Service Commission and the Governor, of

certain positions in the New York County District

Attorney's Office in the exempt and non-competitive

20

classes:

"Such rule or regulation may be

set aside by the courts, if at

all, only in an appropriate pro

ceeding upon proof that the rule

or regulation is without ration

al basis and wholly arbitrary."(Id. at 306, 307)

In Barnett v. Fields, 196 Misc. 339, (Sup.Ct.

N.Y. Co.-1949) aff'd 276 App. Div. 903, aff'd 301, N.Y.

543, the court declared:

"Legislative classification of a

position in the non-competitive

class will not be overruled in

the absence of proof that same was

clearly arbitrary and unreason

able." (196 Misc. at 343.)

Accord, Craig v. Board of Education, 173 Misc.

969, 982 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co.-1940), aff'd 262 App. Div.

706; Fuchs v. Board of Education, 143 N.Y.S. 2d 788,

789 (Sup. Ct. Kings. Co.-1955), motion for leave to

appeal denied 1 A.D. 2d 892.

The discretion granted to the Legislature by

Article V Section 6 has been specifically recognized as

it pertains to Section 2573 subdivision 10 of the Educa

tion Law, the very same subdivision at issue herein. In

Maloff v. Board of Education, 143 N.Y.S. 2d 792 (Sup. Ct.

Kings Co.-1955), appeal dismissed 1 N.Y. 2d 668 (1956),

a dispute between the Board of Education and the Board

of Examiners as to the proper classification for a

21

particular supervisory position was ultimately settled

by the Legislature's amending said Section 2573 subdi

vision 10 by placing the disputed position in the

non-competitive class. The court held:

"Against this background it would

appear that there is fair and reason—

akle ground for difference of opinion

among the intelligent and conscientious officials of the Board of

Examiners and the Board of Education of the City of New York as to the

proper mode of filling the position

of [high school] administrative assistant... in these circumstances

the placing of the position cf admini

strative assistant in the non-competi

tive class was a reasonable and valid exercise by the Legislature of its

power to classify positions in the

public service as it is authorized to

do under Article V Section 6 of the

Constitution of the State of New York "(143 N.Y.S. 2d at 796.)

Thus, the Legislature can be said to have acted

unconstitutionally in amending Section 2573 subdivision

10 and adding Sections 2590-j 4(b) and (d) only if its

decision can be said to have been arbitrary or unreason

able. Intervenors-appellees respectively submit that an

examination of the facts and circumstances surrounding

the legislative enactment demonstrates conclusively that

no such characterization is applicable.

The court below correctly took cognizance of

the extensive legislative history which preceded the

22

statutory change (A. 13-15). Chapter 330 of the Law of

1969, which embodies these changes, was the third in a

series of three Acts, passed by the Legislature over

three consecutive sessions, which mandated fundamental

alterations in the structure of the New York City public

school system. The first of these Acts, Chapter 484 of

the Laws of 1967, inter alia, directed the Mayor of the

City of New York to prepare a report on decentralizing

the system. Pursuant thereto, the Mayor's Advisory Panel

on Decentralization of the New York City Schools issued

a study entitled Reconnection for Learning, popularly

known as the Bundy Report. In discussing the supervisory

service, the Report urged changes beyond those ultimately

adopted by the Legislature:

"For a process which had great

protective value in an earlier

time is now a critical limitation

upon the ability of the school

system of New York to reverse the

current trend toward disaster. Cen

tralized examinations with numbered

rank lists are wholly inconsistent

with the requirements of effective

decentralization. The urgent need

for decentralization, the dramatic reversal of the balance between the

supply and demand of qualifying personnel, and the drastic change in

the requirements for educational

leadership today, all persuade us

that it is the time to abandon the present examining system." (Bundy

Report, p. 51; emphasis added.)

23

During the following legislative session, the

State Commissioner of Education, with Board of Regents

endorsement, also recommended abolishing the Board of

Examiners system altogether. In assessing the need for

reform, the Commissioner urged prompt action in view of

the deteriorating educational situation:

"With every passing day the tensions,

the pressures, the confusion, mount in the ghettos of New York City. It

is unnecessary to emphasize the import

ance of education in this situation

both for its results and for the sig

nificance it has come to have in the

minds and attitudes of the people.

"I recognize the extreme difficulties

of dealing with the overwhelming com

plexities of New York City and the

awesome responsibility of decisions

which will affect the education of one

million children, the careers of fifty

thousand teachers and other profes

sionals and the fate of the nation's

largest city, but I believe that further delay in taking action...will

provoke still deeper bitterness and

resistance that will heighten tension

already at the explosion point.

"... I would urge that the Regents use

the full force and influence of their

office to secure the enactment of

legislation that will carry out the

proposals outlined in this statement."

(Recommendations of the Commissioner of

Education to the Board of Regents Con

cerning Decentralization of the City

School District of the Cxty of New York,

March 27, 1968, approved by the Board

of Regents, March 29, 1968; p. 26, 27.)

24

In response the Legislature enacted Chapter

568 of the Laws of 1968, providing for an interim decen

tralization program pending a final enactment at the fol

lowing session. Meanwhile, a suit had been filed based on

Article V Section 6 challenging the appointment of acting

principals of demonstration elementary schools, thus, by-pas

sing a ranked competitive list, pursuant to the 1967 Act.

In upholding the appointments, the Court of Appeals made it

explicit that Legislative changes in the personnel practices

of the school system must be permitted the flexibility

needed to deal with grim reality. The court declared in

Council of Supervisory Associations v. Board of Education,

23 N.Y. 2d 458 (1969) at pp. 463-4:

" It became obvious the traditional

public school teaching was not suc

ceeding in imparting to a very sub

stantial segment of children the

basic educational tools needed for

ultimate economic usefulness. This

failure to teach what is indispens

able to any single person operating

in present day life had two conse

quences: it tended to compel the

child as he grew up to remain in the

dismal and ghetto-like conditions of

an economically underprivileged com

munity and to solidify the alienation

of that community with fateful consequences; and it aroused in the non

white community a quite reasonable

demand that public school teaching

methods be recast to give its child

ren the necessary essential skills...

25

No one had an adequate answer

but the strongest demands of good

sense called for a solution. The area was one in which experimenta

tion, the testing of new ideas

inductively, pointed to an obvious

direction for public policy. It

is with this background that Chapter

484 of the Laws of 1967 must be

read. The statute did not spring up

in a vacuum." (Emphasis added.)

And the court significantly concluded, (at

p. 469):

"The explanation which is the basis of this proceeding may not solve

the problem but it is not being

solved by rigid adherence to past

techniques. The Legislature and the

responsible educational officers of

the state and city have seen experi

mentation as a possibility of improv

ing the education of children in slum

areas. The court ought to give it a

reasonable chance of success."

(Emphasis added.)

Ultimately, in response to the crisis described

by the Bundy Report, the Commissioner of Education, and

the Court of Appeals, among others, the Legislature

enacted Chapter 330 of the Laws of 1969, the Community

School District System for the City of New York. In

view of the many prominent persons and groups who had

extensively studied and reported on these matters; in

view of the constant flow of publicity and events sur

rounding the issues, including the teachers' and super

visors' unions' strikes in 1968; and in view of the ex

tensive length of time over which the Legislature con

sidered this extremely complex problem, it cannot reason

26

ably be concluded that the changes effected by the 1969

Act were simply arbitrary or capricious. The Legisla

ture, though effecting significant changes in selecting

supervisory personnel, did not go nearly as far as

either the Bundy Report or the Education Commissioner,

among others, had recommended. Instead it struck the

careful balance which is at issue herein, and its judg

ment is entitled to be sustained by the courts in accord

ance with the standards established in Sweet, Ottinger,

Meenagh, Barnett, Maloff and the other precedents cited

heretofore.

In their brief, however, appellants contend

that the Legislature has not made a showing that all

supervisory positions cannot be filled on competitive

basis, and that therefore its amendment to § 2573 sub

division 10 is unconstitutional. (Appellants' Brief

p. 26.) First, in view of the legislative history that

has been detailed heretofore, intervenors thoroughly

reject the contention that the Legislature had shown no

reason why the method of appointing supervisory personnel

was in dire need of reform.

Second, appellants' argument assumes that the

burden is on the Legislature to prove its enactments'

constitutionality. In fact, the opposite is true: Any

statute is to be accorded a presumption of constitution

27

ality and validity, Klipp v. New York State Civil Service

Commission, 247 N.Y.S. 2d 632, 636 (Second Dept.-1964),

and legislative classifications of positions in the non

competitive class will not be overruled in the absence of

proof that the classifications were clearly arbitrary and

unreasonable, Barnett v. Fields, supra.

Appellants further contend that the Legislature

cannot constitutionally remove an entire category of

positions from the non-competitive category without showing

impracticability to conduct competitive examinations for

each such position (Appellants’ Brief p. 26). Actually,

appellants have no standing to raise such a claim except

as to the one position which concerns them. Nevertheless,

the court below correctly found that the deliberations

leading up to the decentralization act of 1969 contemplated

all supervisory positions, and that the amendment to Sec

tion 2573 subdivision 10, not being arbitrary or capricious,

therefore constituted a valid exercise of legislative

power (A. 14-16).

In fact, exemption from competitive requirements

of whole categories of positions is quite common. In

Felder v. Fullen, 27 N.Y.S. 2d 699 (Sup. Ct. N.Y.Co.-1941),

aff'd 263 A.D. 986, aff'd 289 N.Y. 658, the constitutiona

lity of a statute which placed in the non-competitive

class all employees of privately owned subways taken over

28

by the City of New York was upheld. In Application of

Hagan, 239 N.Y.S. 2d 913 (Sup. Ct. N.Y.Co.-1963), aff'd

19 A.D. 2d 862, aff'd 250 N.Y.S. 2d 55, the legislative

enactment that precluded examinations for any rank higher

than captain in the New York City Police Department,

was upheld.

The situation in the education field is even

more salient. By statute, all teaching and supervisory

positions in public schools throughout the State are in

the "unclassified" service. (Civil Service Law Sec.35(g)).

Jobs in the unclassifed service are excluded from the

merit system in the absence of any other statutory provi

sion providing merit testing for specific positions.

Thus, it is only because of certain sections of the Edu

cation Law - such as 2569, 2573 and 2590 - that pedagogi

cal positions in the City Schools Districts of New York

and Buffalo are subject to a merit system. The Legisla

ture has, across the board, exempted the staff of all

other public school districts throughout the state from

any testing, competitive or non-competitive, and this

has always been true since the civil service system was

introduced into the State in 1883. Such personnel are

naturally subject to miniumu certification requirements

of the State Education Commission, and the Regents (Civil

Service Law, Sec. 35(g)), but the Legislature has in

29

effect found, pursuant to Article V Section 6 of the

State Consitution, that further specific testing is

not practicable in the determination of merit and fit

ness. It has of course done this without considering

every particular teaching and supervisory position in

every department. Thus, the assertion of appellants

that the Legislature must do so is contrary to the

entire history of education and civil service in this

State. A ruling that it must do so would raise the

potential for severe disruption of public school sys

tems throughout the State.

In addition, an order requiring a ranked

competitive list for any or all supervisory positions

would substantially destroy the decentralization program

for the New York City schools. Pursuant to § 2590-b2(b)

of the Education Law, thirty-three community school dis

tricts have been created, each with a popularly elected

board. Various administrative and policy-making powers

formerly in the domain of the City Board and its Superin

tendent, have been delegated to the community boards, though

it is probably fair to say that the City Board retains

substantial power and control. However, perhaps the most

significant authority which community boards have been

granted is contained in § 2590-j 4(d):

30

"Each community board shall

appoint and assign all super

visory personnel for all schools

and programs under its juris

diction from persons on quali

fying eligible lists."

In general, the terms "all schools and programs" means

pre-kindergarten, nursery, kindergarten, elementary,

intermediate and junior high schools (§ 2590-e). The

basic thesis of the Legislature being that more community

board authority is necessary to improve a very troubled

school system, let us examine what the effects would be

if a key provision of that reform effort - the eligible

qualifying list concept for supervisory appointments -

were scrapped.

The subject of this litigation, the list for

junior high school assistant principal is presently in

effect and contains over 600 names. Suppose District F

in Brooklyn wished to fill a vacancy in one of its junior

high schools. Assume it followed all the proper advertis

ing procedures giving all persons on the list an opportu

nity to apply, and that it received some number of res

ponses. The community board and its community superinten

dent would then interview and evaluate all prospective

candidates, paying particular attention to their experience

with and responses to, the particular problems plaguing

that school: let us say, high drop-out rates, substantial

vandalism and drug abuse. Upon completion of this process

31

the board would select a candidate whom it honestly felt

was most experienced with, sensitive to, and prepared to

deal with, such problems. Let us also assume that the

selectee turned out to be number 550 on the list, and

that several hundred persons above that number had not

yet been selected for positions.

The consequences of returning to the ranked

competitive concept are obvious. Even though the elected

community board chose the person it felt most qualified,

its efforts would be futile. For only until 447 persons

above the selectee were appointed to positions throughout

the city could their choice be effected. Since there are

only 150 junior high and intermediate schools, and since

the list has only a four year life (§ 2590-j 4(f)), the

chance of this ever occurring would be very slight. At

best, substantial delay would be involved, whereas the

position was in immediate need of being filled.

Worse still, the use of the ranked competitive

list might lead to widespread abuses. For, in a situation

such as described above, enormous pressure could very well

develop to "find" jobs for those ranked on the list between

the lowest numbered person who had received an appointment,

and the choice of a particular community, so that the

latter selection could be effected.

What is true of the list for junior high school

32

assistant principal, is also true for the other super

visory positions. That is why the Legislature placed

appointment procedures for all such procedures on a

qualifying list basis. After having found a decentralization

program necessary for public education in New York City,

it found competitive examinations impracticable for the

supervisory service. This it is clearly entitled to do

under Article V Section 6 of the New York State Constitu

tion and its decision should not be distrubed.

None of the cases cited by appellants contra

dicts this view: Friedman v. Finegan, 268 N.Y. 93 (1935),

(Appellants' Brief pp. 18,20), concerned a statutory in

terpretation issue, and simply held that the Civil

Service Law was meant to apply to clerks and deputy

clerks of the Municipal Court of the City of New York. In

that case, however, the court reiterated that the Legis

lature can classify positions in the non-competitive

class but must not act unreasonably or arbitrarily in

doing so. (Id. at 98). Martin v. Burke, 25 Misc. 2d,

1042, 1047, (1960), (Appellants' Brief pp. 19, 20) was

another statutory interpretation decision, where the judg

ment of the Municipal Civil Service Commission of the

Utica that the Director of Urban Renewal was not in the

exempt category, was upheld. Matter of Carow v. Board

33

of Education, 272 N.Y. 341, 347, 348 (1936), (Appel

lants' Brief p. 19) simply upheld the right of the Legis

lature to decide under Article V Section 6 that teachers'

lists for New York City can practicably be ranked compe

titive even though such positions are in the unclassified

service. That case does not simply say that Article V

Section 6 applies to all civil service positions, as

appellants contend. Its actual ruling is as follows

Id. at p. 344:

"[Art. V Sec. 61 applies to every

position in the Civil Service of

the state but within the limits

which we have attempted to define

in other cases, the Legislature

may determine either its practi

cability to ascertain merit and

fitness for a particular position

by competitive examination, or,

indeed, by any examination.

(Emphasis added.)

Similarly, Babylon v. Stengel, 43 Misc. 2d

196, 198 (1964), (Appellants' Brief p. 19), in which

petitioner sought to have the position of assistant

public welfare officer placed in the exempt category,

explicitly reiterated the standards set forth in Ottinger

supra, p. 19.

34

THE COURT BELOW CORRECTLY FOUND

THAT PETITIONERS HAD NO VESTED

RIGHT TO HAVE APPOINTMENTS, ON

A RANKED COMPETITIVE BASIS OR

OTHERWISE, AND THAT THE LEGIS

LATIVE CHANGE IN SECTION 2573

SUBDIVISION 10 HAD NO RETRO

ACTIVE EFFECT.

POINT II

Appellants claim that under the circumstances

of this case, the law entitles them to appointment on

a ranked competitive basis (Appellants' Brief p. 27).

This contention is based on their assertion that res

pondent Board of Education considered the examination

to be a competitive one throughout the examination

process, and that this entitles petitioners to have the

examination treated as such.

Appellants however are in error on the facts.

As intervenors-respondents have pointed out herein

(supra, p. 2), nothing in the examination announcement

(A. 58) stated that the examination was to be a ranked

competitive one. Furthermore, there is absolutely no

indication that the method of administering or otherwise

"treating" the examination would have in any way differed

based on whether the ultimate list promulgated therefrom

were ranked or unranked. The fact that respondent

Theodore Lang wrote a letter long after the examination

was completed, stating that the list would be ranked,

35

confers on petitioners absolutely no right to appoint

ment on a ranked basis.

As the court below correctly pointed out (A. 17),

Section 2573 subdivision 10 deals only with appointments.

Petitioners gained no right to appointment by taking and

passing an examination. Appointments to the position in

question, as noted heretofore, are the exclusive power of

community school boards (§ 2590-j 4(d)). Thus, as the

court below correctly found, the fact that the statute

prescribed appointments on a ranked basis at the time

of the examination, endowed petitioners with no right to

actual appointments being made on such a basis. But

even under the old statute, an appointment need only be

made from among one of the top three. Even the first

name on the list could continually be passed over. Thus

appointments were never guaranteed, even under the ranked

competitive system. Nor did the former statute preclude

the Legislature from altering the method of appointment

in the future.

"There can in the nature of things

be no vested right in an existing

law which precludes its change or

repeal nor a vested right in the omission to legislate on a particu

lar subject. In no case is there an

implied promise on the part of the

State to protect its citizens against

incidental injury ordered by changes

in the law." Kornbluth v. Reavy, 261

A .D. 60, 63, motion for leave to

appeal denied, 285 N.Y. 859.

36

Thus, even if the examination had been announced

as a ranked competitive one, this would in no wise preclude

the Legislature from validly amending the statute as it

did.

Appellants contend further, however, that the

statutory change was applied retroactively in violation

of their vested rights (Appellants' Brief p. 33). Since

it has already been established that they had no such

vested rights, such retroactive application could not

aggrieve petitionevs. Howe^r, as the court below cor

rectly noted (A. 17), the statutory change was not applied

retroactively, because it dealt only with appointments

and was passed by the Legislature before the list was

promulgated. For all these reasons, appellants' citations

of cases (Appellants' Brief pp. 34-36) dealing with the un

constitutionality of taking away vested rights retroactively

by legislative or administrative action, are inapposite.

37

THE COURT BELOW CORRECTLY FOUND

PETITIONERS LOST NONE OF THEIR

RIGHTS TO VETERANS' PREFERENCES

AS A RESULT EITHER OF THE CHANGE

IN SECTION 2573 SUBDIVISION 10

OR IN THE ACTIONS OF THE BOARD

OF EDUCATION.

POINT III

Appellants assert that some of their number

have in effect been deprived of veterans1 credits due

them under Article V Section 6 of the New York State

Constitution because they applied them to the assistant

principal's list at issue herein in order to raise

their relative standing on a ranked competitive list;

but, having so applied their credits, they could not

apply them to any other civil service list because of

the one-time limit in said Article V Section 6, whereas

their application to the assistant principal's list

became worthless since the list was ultimately an un

ranked one (Appellants' Brief pp. 38-40).

This alleged grievance can be disposed of in

short order. As the court below correctly noted, Section

85 subdivision 4 of the Civil Service Law provides that

where the additional veterans' credits do not affect a

candidate's relative standing where the list is published

or names therefrom certified, the candidate is deemed

not to have used the credits. Moreover, both Section 85

subdivision 5 of the Civil Service Law, and the

official policy of the Board of Examiners (A. 92),

make it clear that such bonus points can be withdrawn

by the candidate prior to actual appointment, and

hence used at a later time. Thus, none of appellants

has suffered a grievance with regard to veterans'

38

bonus credits.

39

POINT IV

THE COURT BELOW CORRECTLY FOUND

THAT PETITIONERS WERE DEPRIVED OF

NO CONTRACTUAL RIGHTS AS A RESULT

OF ANY ACTION BY THE LEGISLATURE

OR THE BOARD OF EDUCATION.

Appellants contend that the retroactive

application of the amendment to Section 2573 subdivi

sion 10 violated the terms and conditions of an alleged

contract which had come into effect when they paid a

fee to take an examination which had been announced by

the Board of Examiners. They cite no authority for

this proposition. Even if there were a contract, none

of its terms were violated in that, as heretofore noted,

the examination announcement (A. 59) mentioned nothing

about competitive appointments.

In fact, however, the fee is a charge which

may be instituted at the discretion of the agency (Civil

Service Law, § 50 subd. 5(b)), and is analogoug to a

user fee or special assessment to offset the cost of

the service provided. The court below thus correctly

found that payment of this fee created no rights other

than the right to be admitted to the examination (A. 19)

40

CONCLUSION

The judgment appealed from should be upheld

and the petition dismissed.

Dated:

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG ELIZABETH B. DuBOIS

STEPHEN G. YOUNG

for intervenors-RespondentsAttorneys