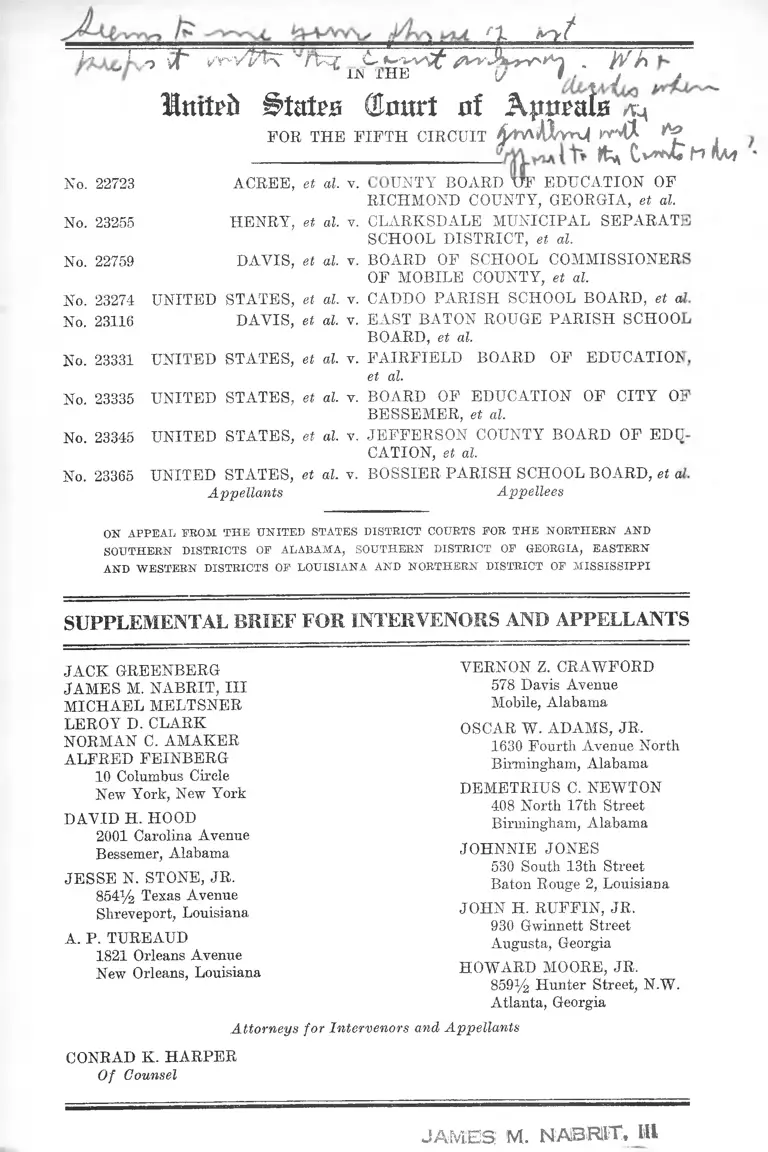

Acree v. County Board of Education of Richmond County, GA and Combined School Board Cases Supplemental Brief for Intervenors and Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Acree v. County Board of Education of Richmond County, GA and Combined School Board Cases Supplemental Brief for Intervenors and Appellants, 1966. a92c19cc-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/87e9d5f7-53ca-4771-87d1-201b56abe36c/acree-v-county-board-of-education-of-richmond-county-ga-and-combined-school-board-cases-supplemental-brief-for-intervenors-and-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

.... r^yt

l~ 1 n vf~ l/r-VptK Vfcqr t - 4 ^ ^ /v v - 'S - ry '^ 4 ^ h

1JN i l i i l j {/ f # J A

Ituted States (Emtrt of Apmafs *4

FOR THE FIFT H CIRCUIT ^m A X v » M * '* '$ ^ ,

fc* t v ^ v C h ^ U r

UNTY BOARD WNo. 22723 ACREE, et al. v.

No. 23255 HENRY, et al. v.

No. 22759 DAVIS, et al. v.

No. 23274 UNITED STATES, et al. v.

No. 23116 DAVIS, et al. v.

No. 23331 UNITED STATES, et al. v.

No. 23335 UNITED STATES, et al. v.

No. 23345 UNITED STATES, et al. v.

No. 23365 UNITED STATES, et al. v.

Appellants

EDUCATION OF

RICHMOND COUNTY, GEORGIA, et al.

CLARKSDALE MUNICIPAL SEPARAT]

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.

BOARD OF SCHOOL COMMISSIONER

OF MOBILE COUNTY, et al.

CADDO PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et a

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH SCHOO:

BOARD, et al.

FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

et al.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF CITY 0]

BESSEMER, et al.

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDO

CATION, et al.

BOSSIER PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et a

Appellees

ON A PPEA L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTRICT COURTS FOR T H E N O R T H E R N AND

SO U TH ER N D ISTR IC TS OP ALABAMA, SO U TH ERN D ISTRICT OF GEORGIA, EASTERN

AND W E ST ER N D ISTRICTS OF LO U ISIA N A AND N O R T H E R N D ISTRICT OF M IS S IS S IP P I

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR INTERVENORS AND APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, I I I

MICHAEL MELTSNER

LEROY D. CLARK

NORMAN C. AM AKER

ALFRED FEINBERG

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

DAVID H. HOOD

2001 Carolina Avenue

Bessemer, Alabama

JESSE N. STONE, JR.

854% Texas Avenue

Shreveport, Louisiana

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

VERNON Z. CRAWFORD

578 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama

OSCAR W. ADAMS, JR,

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON

408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama

JOHNNIE JONES

530 South 13th Street

Baton Rouge 2, Louisiana

JOHN Ii. RUFFIN, JR.

930 Gwinnett Street

Augusta, Georgia

HOWARD MOORE, JR.

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Intervenors and Appellants

CONRAD K. HARPER

Of Counsel

JA M ES M. NABRIT, lill

IN THE

H&nxUb ( t o r t n f A p p e a l s

FOR THE FIFT H CIRCUIT

No. 22723 ACREE, et dl. v.

No. 23255 HENRY, et al. v.

No. 22759 DAVIS, et al. v.

No. 23274 UNITED STATES, et al. v.

No. 23116 DAVIS, et al. v.

No. 23331 UNITED STATES, et al. v.

No. 23335 UNITED STATES, et al. v.

No. 23345 UNITED STATES, et al. v.

No. 23365 UNITED STATES, et al. v.

Appellants

COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION OF

RICHMOND COUNTY, GEORGIA, et al.

CLARK,SDALE MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.

BOARD OF SCHOOL COMMISSIONERS

OF MOBILE COUNTY, et al.

CADDO PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH SCHOOL

BOARD, et al.

FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF CITY OF

BESSEMER, et al.

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDU

CATION, et al.

BOSSIER PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.

Appellees

ON A PPEA L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTRICT COURTS FOR T H E N O R T H E R N AND

SO U TH ER N D ISTRICTS OF ALABAMA, SO U TH ERN D ISTRICT OF GEORGIA, EA STERN

AND W E ST ER N D ISTRICTS OF LO U ISIA N A AND N O R T H E R N D ISTRICT OF M IS S IS S IP P I

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF

FOR INTER VENOUS AND APPELLANTS

A R G U M E N T

This Court Should Rely Upon Applicable HEW Guide

lines in School Segregation Cases Provided the Guide

lines, Where Followed, Effect Actual Desegregation.

In answer to the April 21, 1966 letter of the Clerk to

this Court, the undersigned counsel urge that the HEW

guidelines1 be adopted as minimum standards for all school

1 The United States Office of Education Department of Health, Educa

tion and Welfare, Revised Statement of Policies for School Desegrega-

9,

desegregation plans, provided the guidelines, where fol

lowed, effect meaningful desegregation. Such a policy as

sures desirable uniformity among school districts within

the jurisdiction of this Court. The guidelines, moreover,

represent the expert judgment of the United States Office

of Education staff that all school districts are capable

of accomplishing certain preliminary or elementary deseg

regation goals. These expert judgments, formulated after

opportunity for fact finding and consultation not readily

available to the judiciary, are entitled to great weight,

cf. Price v. Denison Independent School District, 348

F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965); Udall v. Tollman, 380 U.S. 1

(1965), even where delicate constitutional questions are

involved, cf. Zemel v. Rush, 381 U.S. 1 (1965). Regula

tions promulgated pursuant to congressional authoriza

tion2 generally have the force of statute. Federal Crop

Ins. Corp. v. Merril, 332 U.S. 380, 385-86 (1947) (wheat

crop insurance regulations); Standard Oil Company v.

Johnson, 316 U.S. 481, 489 (1942) (War Department

regulations); Arizona Grocery Company v. Atcheson,

Topeha and Santa Fe Railroad Co., 284 U.S. 370, 386

(1932) (ICC regulations). The result should not be dif

ferent in the instant cases where either the United States

is a party or private litigants have borne the brunt of

seeking constitutionally required desegregation.

tion (March 1966) [hereinafter cited as Revised Statement] 45 CFR,

Part 181.

2 Section 602 of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 78 Stat. 252, 42 U.S.C.

§2000d-l (1964), specifically provides for the issuance of rules and regula

tions, consistent with the Act, by federal departments empowered to extend

federal financial assistance to any program, other than a program in

volving a federal contract of insurance or guaranty. Guidelines are issued

pursuant to §602. Revised Statement §181.1. Section 602 embodies a well

known congressional practice. See Shapiro, The Choice of Rulemaking

or Adjudication in the Development of Administrative Policy, 78 Harv.

L. Rev. 921, 958-71 (1965).

3

The guidelines have not been formulated in a context

unsympathetic to local problems; §§403 through 405 of

the 1964 Civil Eights Act3 provide that, upon request,

the Commissioner of Education may render technical as

sistance to public school systems engaged in desegrega

tion. The Commissioner may also establish training in

stitutes to counsel school personnel having educational

problems occasioned by desegregation; and the Commis

sioner may make grants to school boards to defray the

costs of providing in-service training on desegregation.

In short, the Commissioner may assist those school boards

who allege that they will have difficulty complying with

the guidelines. In view of these facts, especially the as

sistance which may be furnished to meet alleged difficulties,

there is a heavy burden on those who would argue that

they cannot meet HEW standards. None of the school

boards in these cases has met that burden; indeed, none

of them has indicated that it cannot desegregate its school

system by the HEW deadline of September, 1967.

The failure of this Court to adopt standards at least

as stringent as the guidelines would encourage litigation

by recalcitrant school boards, cf. Singleton v. Jackson

Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d 729, 731 (5th

Cir. 1965), because court-ordered desegregation plans are

exempted from the guidelines. Revised Statement §181.6.

Where school boards’ plans do not meet minimum stan

dards,4 this Court should invite HEW to enter such cases

3 78 Stat. 247-48, 42 U.S.C. §§2000c-l through 2000c-3 (1964).

4 As of May 6, 1966, counsel are informed that, with one exception to

be mentioned, none of the school boards, in the nine eases for which this

brief is filed, has complied with the HEW guidelines. This is so because

under Revised Statement §181.6, school boards under a court order need

only file a copy of said order, which the school boards have done. The

single exception is the County Board of Education of Richmond County,

Georgia, No. 22723 in this Court, which has filed form 441-B with the

4

with a view towards raising the plans to the level of the

guidelines. This position is, therefore, substantially similar

to that advanced by the United States in its suggested

specific decree in seven school segregation cases now pend

ing in this Court.5 We would emphasize, however, that

the adoption of a specific decree in these cases framed in

terms of the guidelines is only a partial answer to the

segregation problem. Thus, we go further than the posi

tion taken by the United States. Uppermost must be the

actual realization of desegregation. The assistance fur

nished by HEW to local school boards desegregating

under a court order would provide an effective method of

bringing about this meaningful desegregation.

Of course, the focus of the courts must be, under Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), on the realiza

tion of desegregated education, if necessary, irrespective

of the guidelines. The courts must require that those

plans conforming to the guidelines operate to provide a

desegregated education. For those matters not covered

by the guidelines, such as school construction programs

perpetuating segregated education and the need to up

grade inferior schools which in fact remain all-Negro,6

Department of Health, Education and Welfare. The Richmond County

Board has not filed any of the other extensive information necessary to

bring it into full compliance with the guidelines. This information was

obtained from the office of Mr. David S. Seeley, Assistant Commissioner

of the Equal Educational Opportunities Program in the Department of

Health, Education and Welfare.

5 Vol. IV of Appendix to briefs of the United States in Nos. 23173,

23192, 23274, 23331, 23335, 23345, 23365.

6 Revised Statement, §181.15 speaks only of closing the “small, inade

quate” Negro school.

Overcrowded Negro schools exist in Clarksdale, Miss., Brief for Appel

lants in No. 23255, pp. 10-14; East Baton Rouge, La., Brief for Appellants

in No. 23116, pp. 9-10; Fairfield, Ala., Brief for Intervenors in No. 23331,

pp. 19-20; and Jefferson County, Ala., Brief for Intervenors in No. 23345,

p. 10. Proportionally more funds are spent on white schools than on Negro

5

the courts must also frame mandates designed to make

equal educational opportunity a reality. School author

ities must be put on notice that the only valid plan is

one which effects desegregation. To this end frequent

and comprehensive court review of the facts of desegrega

tion is a necessity. See the order in Carr v. Montgomery

Board of Education, Civil No. 2072-N, M.D. Ala., March 22,

1966, requiring periodic reports from the school board.

Where the facts reveal that actual desegregation is not

taking place, courts should require school boards to take

effective affirmative steps such as ordering rezoning or

other assignment methods. The opinion in Dowell v. School

Board of Oklahoma Public Schools, 244 F. Supp. 971

(W.D. Okla. 1965) (appeal pending, 10th Circuit, No.

8523), illustrates the comprehensiveness of a court man

date designed to guarantee desegregation.

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 297 (1955),

held that:

Once such a start [toward desegregation] has been

made, the courts may find that additional time is

necessary to carry out the ruling in an effective man-

schools in Clarksdale, Miss., Brief for Appellants in No. 23255, pp. 8,

12-13; and in Fairfield, Ala., Brief for Intervenors in No. 23331, p. 20.

The physical facilities of Negro schools are inferior to those of whites in

Bossier Parish, La., Brief for Appellant Lemon in No. 23365, pp. 8-9; in

Jefferson County, Ala., Brief for Intervener in No. 23345, pp. 9-10; in

Bessemer, Ala., Brief for Intervenors in No. 23335, pp. 16-18; in Fair-

field, Ala., Brief for Intervenors in No. 23331, p. 20; and in Mobile

County, Alabama, Brief for Appellants in No. 22756, pp. 13-14. Negro

schools have course offerings inferior to those provided in white schools in

Richmond County, Ga., Brief for Appellant in No. 22723, p. 2; in Bossier

Parish, La., Brief for Appellant Lemon in No. 23365, pp. 7-8; in Jefferson

County, Ala., Brief for Intervener in No. 23345, p. 9; in Bessemer, Ala.,

Brief for Intervenors in No. 23335, p. 16; in Fairfield, Ala., Brief for

Intervenors in No. 23331, p. 21; in Mobile County, Ala., Brief for Appel

lants in No. 22759, p. 14; and in Clarksdale, Miss., Brief for Appellants

in No. 23255, p. 5, n.5.

6

ner. The burden rests upon the defendants [i.e., the

school boards] to establish that such is necessary in

the public interest and is consistent with good faith

compliance at the earliest practicable date. 349 U.S.

at 300 (emphasis supplied).

Eleven years later, none of the school boards in these

cases has given sufficient justification for any delay. None

has alleged that it cannot comply with the HEW goal of

desegregation by September 1967, thus the least that can

be required of them is conformity to HEW’s standards.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, I I I

MICHAEL MELTSNER

LEROY D. CLARK

NORMAN C. AMAKER

ALFRED EEINBERG

VERNON Z. CRAWFORD

578 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama

OSCAR W. ADAMS, JR.

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

DAVID H. HOOD

DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON

408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama2001 Carolina Avenue

Bessemer, Alabama

JESSE N. STONE, JR.

JOHNNIE JONES

530 South 13th Street

Baton Rouge 2, Louisiana854% Texas Avenue

Shreveport, Louisiana JOHN H. RUFFIN, JR.

930 Gwinnett Street

Augusta, Georgia

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana HOWARD MOORE, JR.

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Intervenors and A ppellants

CONRAD K. HARPER

Of Counsel

7

Certificate o f Service

This is to certify that a copy of the foregoing supple

mental brief has been served on each of the attorneys for

appellees and the United States, as listed below, by being

deposited in the United States mail, air mail, postage

prepaid, on this day of May, 1966:

Hon. John A. Richardson

District Attorney

1st Judicial District

Caddo Parish Courthouse

Shreveport, Louisiana

Hon. William P. Schuler

Assistant Attorney General

201 Trist Building

Arabi, Louisiana

Mr. J. Bennett Johnston, Jr.

930 Giddens Lane Building

Shreveport, Louisiana

Mr. Macon Weaver

United States Attorney

Federal Building

Birmingham, Alabama

Mr. Maurice F. Bishop

Bishop & Carlton

325-29 Frank Nelson Building

Birmingham, Alabama

Mr. Reid B. Barnes

Lange, Simpson, Robinson &

Somerville

317 North 20th Street

Birmingham, Alabama

Hon. Jack P. F. Gremillion

Attorney General

State Capitol

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Mr. David L. Norman

Department of Justice

Washington, D. C.

Mr. Edward L. Shaheen

United States Attorney

Federal Building

Shreveport, Louisiana

Mr. J. Howard McEniry

McEniry, McEniry & McEniry

1721 4th Avenue North

Bessemer, Alabama

Hon. Louis H. Padgett, Jr.

District Attorney

Bossier Bank Building

Bossier City, Louisiana

Hon. John Dear

St. John Barrett

Peter Smith

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

George F. Wood, Esq.

510 Van Antwerp Building

Mobile, Alabama

Franklin H. Pierce, Esq.

Southern Finance Building

Augusta, Georgia

Ed Foulcher, Esq.

520 Green Street

Augusta, Georgia

Semmes Luckett, Esq.

121 Yazoo Avenue

Clarksdale, Mississippi 38614

John F. Ward, Esq.

Burton, Roberts and Ward

206 Louisiana Avenue

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Attorney for Intervenors and

Appellants

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C