United States v. Nobles Court Opinion

Working File

June 23, 1975

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. United States v. Nobles Court Opinion, 1975. 78ed5480-ee92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/87feda5a-8e8d-40d7-a6bb-e8ad266e097e/united-states-v-nobles-court-opinion. Accessed March 01, 2026.

Copied!

224 OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Wrrrrr, J., dissenting 422U.5.

absolutes the Court adds nothing to First Amendment

analysis and sacrifices legitimate state interests. I

would affirm the judgment of the Florida Court of

Appeal.'

Mn. Jusrrco Wurro, dissenting.

The Court asserts that the State may shield the public

from selected types of speech and allegedly expressive

conduct, such as nudity, only when the speaker or actor

invades the privacy of the home or where the degree of

captivity of an unwilling listener is such that it is im-

practical for him to avoid the exposure by averting his

eyes. The Court concludes "that the limited privacy

interest of persons on the public streets cannot justify

this censorship of otherwise protected speech on the

basis of its content." Ante, at 212. If this broadside

is to be td<en literally, the State mny not forbid "ex-

pressive" nudity on the public streets, in the public parks,

or a,ny other public place since other persons in those

places at that time have a "limited privacy interest"

and may merely look the other way.

I am not ready to take this step with the Court.

Moreover, by the Court's orvn analysis, the step is an

unnecessary one. If, as the Court holds in Part II-B of

its opinion, the ordinance is unconstitutionally over-

broad even as an exercise of the police power to protect

children, it is fatally overbroad as to the population

generally. Part II-A is surplusage. I therefore dissent.

2 On my view of this case it is not necessary to deal with the

issues discussed in Parts II-B, II-C, and III of the Court's opinion.

I-

UNITED STATES o. NOBLES 225

Syllabus

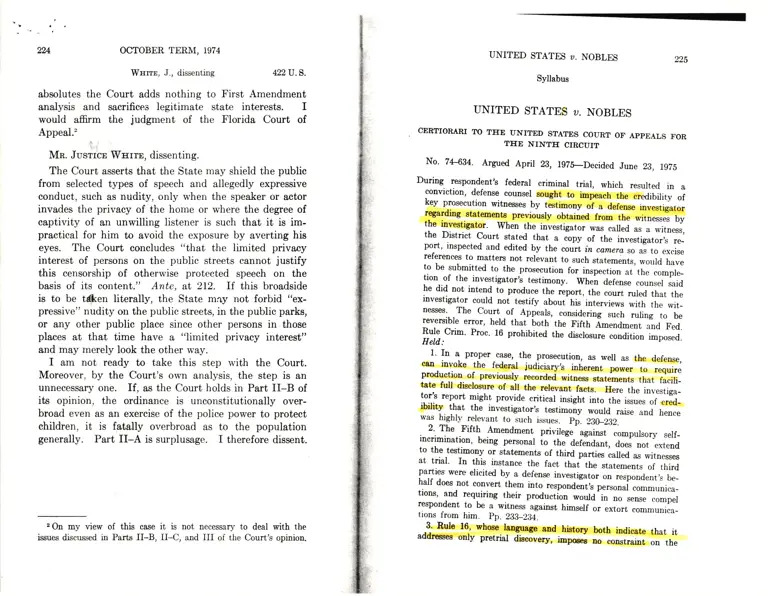

UNITED STATES a. NOBLES

CERTIORARI ?O TITE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

TEE NINTII CIBCUIT

No. 74-634. Argued April 28, l97$_Decided June 28, lgZS

During respondent's federar criminal triar, which resurted in aconviction, defense counsel sought to impeach the credibilitf oikey prosecution witnesses by testimony of u d"funo irr*ilg"t",

regarding state.ments previously obtained from the witnmsei bythe investigator. when the investigator was called as a witnmJ,the District Court stated

-that a ipy of the investigat".t .*port, inspected and edited by the

"oiit;n carnera so as to excise

references to matters not relevant to such ,tr,u*."ii ;;;;;;to be submitted to the prosecution for inspection at the eomple_tion..of the invmtigator,s testimony. Whe'n detense .oun."l .aid

f aij not intend to produce the report, thu .ourt ruled that thernvestrgator courd not testify about his interviews with the rvit-nesses. The Court of. Appealq, eonsidering such ruling to bereversible error, held that both the Fifth .fmendment nnd Fed.

]ufe. Cnn Proc. 16 prohibited the disclosure condition imposed.Held:

1' In a proper case,.the prosecution, as well as the defense,can invoke the federal judiciary,s inherent power to requireproduction of previousry re.ordei witness si"t"-urt, that facili-tate full disclosure of all the relevant facts. Here tire inr.est,ga_

l.o:! ree-ort might provide critical insight lnto ttre issues of cred_ibility that the investigator,s testimoi, ,"rfa raise and hencewas highll.' relevant to such issues. fi. ZaO_ZaZ.

2. The Fifth Amendment_ privilege'against compulsory self_incrimination, being personal to tne aete"ndant, does not extendto the iestimony or statements of third pr;i; caled a.s witnessesat trial. In this instance the fact ttri tfru statements of third

P*i:r were elicited by a defense investigator on respondent,s be_half does not convert them into ...poojuiit personal communica_tions, and requiring their productio, ;orrld.in no sense compelrespondent to be a witness against himself or extort communica_tions from him. pp. 2BB-284.

3. Rule 16, whose language and history both indicate that itaddresses only pretrial dir.Jrury, do; no constraint on the

?}6 OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Syllabus 422 U. S.

District Court's power to condition the impeachment testinony

"irop".a.ot's

witnees on the production-of the relevant por-

;;;;-ht" report. the iact it'"t tt't Rule incorporates the

i"*1.e" ri^tatiou show, uo contrary intent and does not con-

vert the Rule into "

g""tt"ifi-itatior ou the trial court'e broad

d;;;;" as to evidentiary questions at trial' Pp' 234-236'

4. The qualified pti'il;; aerivea from the. attorney work-prod-

uct doctrine i, oot a'"it"'lle to prevent disclozure of the investi-

gative report, since t*po"at"t, by electing to present the in-

?;is"* as'a witnesa, waived th: prylTe with respect to

-;#; covered in his testimony' Pp' '36-240'

5. It was within th; Dltttitt Court's discretion to assure that

the iury would hear tle investigator's full testimony rather than

"1"i.."r,.a

portion favorable to iespondent' and the court's ruli'ng'

contrary to respondentls contention' did not deprive him of the

i'iof ,i-.ta-ent rights to compulsory process and croas-exa'E-

i""ii"". fUt Ameudment does not confer the right to presel!

testimony free from the iegitim'te d9ma1$ of the adverssrisl

.;;;i ;""ot be invoied as a justificetion for preaenting

ii"t -igf,t have been a half-tmth' Pp' 24o-24L'

501 F.2d 146, reversed.

Powrr,r,, J., ddivered the opinion of the Court' in which BuRona'

C. J., and BnnxxeN, $tBwent, Mensrrer,l,' and Br'ecruuN' JJ''

j"irJ,

^ra

i" parts Ii, III, and V of which WnItp and RorxQulst'

il"-i,ir.J. \itro, J., filed a corcurring opinion' in which R^pnx-

qursr, J., joined, port,' p'- i+z' Doucr'es' J'' took no part in the

consideration or decision of the case'

Paut L. Fneilmnn argued the cause for the Unitcd

Stetes. With him on tf,e briefs were Solicztor General

_a

o,n, Acting A ssistont Att orney G en,eral K e enoy, D eplty

Sitt,lto, Gerwral Frey, Si'd'nny M' Glazur' wd luan

Mir,hael Sclwefier.

Nir,hnlo"sR.Altisarguedthecauseforrespondent.

With him on the brief was John K' Von de Kamp'*

rllriefs of onrici curinr urging rllllrtnnnee n'ere filc<l by Jolrn J'

Ctru,'li i..r, tt," California' t'rrliic Uefettdcrs Assn' et al'' ond by the

Federal Public Defeuder of New Jersey'

UNITED STATES u. NOBLES zz7

225 Opinion of the Court

Mn. Jusrrcp Powor,r, delivered the opinion of the

Court.

In a criminal trial, defense counsel sought to impeach

the credibility of key prosecution witnesses by testimony

of a defense investigator regarding statements previously

obtained from the witnesses by the investigator. The

question presented here is whether in these circumstances

a federal trial court may compel the defense to reveal

the relevant portions of the investigator,s report for the

prosecution's use in cross-examining him. The United

States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit concluded

that it ca,nnot. 501 F. 2d l4O. We granted certiorari,

419 U. S. tl20 (1975), and now reverse.

I

Respondent was tried and convicted on charges aris-

ing from an armed robbery of a federally insured bank.

The only significant evidence linking him to the crime

was the identification testimony of two witnesses, a

bank teller and a salesman who was in the bank during

the robbery.' Respondent offered an alibi but, as the

Court of Appeals recognized, bOl F. 2d,at 150, his strong-

est defense centered around attempts to discredit these

eyewitnesses. Defense efforts to impeach them gave rise

to the events that led to this decision.

In the course of preparing respondent,s defense, an

investigator for the defense interviewed both witnesses

and preserved the essence of those conversations in a writ_

ten report. When the witnesses testified for the prosecu_

tion, respondent's counsel relied on the report in conduct_

ing their cross-ex&mination. Counsel asked the bank

l The only other eyidence i.Dtroduced against respondenl wa-. a

statemeDt mede et tle rlme of erres in rhich he deaied :iur he

rr. Roben ]\-obles ald suhsequently stated that he her thar the

FBI had been looki.g for him.

228 OCTOBER TI]RM, 1974

Opinion o[ the Court 422 U. S.

teller rvhether he recalled having told the investigator

that he hacl seen only the back of the man he identified

as .".pondent. The witness replied that he did not re-

member rnaking such a statemetrt' He rvas allorved'

despite defense counsel's initial objection' to refresh his

,".o[".tior', by referring to a portion of the investigator's

report. The prosecutor also rvas allorved to see briefly

It "

."t"ru,rt portion of tlie report''' The rvitness there-

after testified that although the report indicated that he

told the investigator he hacl seeu ottly respondeut's back'

he in fact ha.d seen rnore than that artd continued to

insist that respondent was the bank robber'

The other witness acknorvledged on cross-examination

that he too had spoken to the defense investigator' Re-

spondent's "or.r."l

trvice inquired rvhether he told the

iirvestigator that "all blacks looked alike" to him' and

i"

"u.fr"

instance the witness denied having made such a

statement. The prosecution again sought inspection of

the relevant poriion of the investigator's report' and

respondent's counsel again objected' The court declined

to order disclosure at ihat time, but ruled that it would

be required if the investigator testified as to the wit-

n"rr".i alleged statements from the u'itness stand'' The

2 counsel for the Government complained that the portion of the

."p*i p.oarced at this time rvas illegible The witness' teetimony

iudicrtes, however, that he had no difficulty reading it'

3The essence of the District Court's order was as follows:

"[If the investigator] is allowed to testify it would be necessary

that those portiins of [tt"] investigative report which contain the

sta,tements of tt. impeached rvitness rvill have to be turned over

to the prosecution;

.nothing

else in.that report'

"If he testifies in any way about impeaching statements made by

either of the two *itnes.e., then it is the Court's view that the

gorrernment is entitled to look at his report and only those portions

It ,t,", rcport rvhich contaitr the rrllegcd inrpelclting statcmcnts

of the rvitnesses." APP. 31.

UNITED STATES u. NOBLES 2Zg

225 Opinion of the Court

court further advised that it would examine the investi_

gator's report ,in ca:rnera and would excise all reference to

matters not relevant to the precise statements at issue.After the prosecution completed i[s case, respondent

called the investigator as a defense witness. fh" .rurtreiterated that a copy of the report, inspected and editedin camera, would have to be submitted to Government

counsel at the completion of the investigator,s impeach_

tnent testimony. when respondent,s counsel stated thathe did not intend to produce the report, the court ruledthat the investigator would not be aliowed t" ;rtii;

about his interviews with the witnesses..

The court of Appears for the Ninth circuit, whileacknowledging that the trial court,s ruling constitutej4 "very limited and seemingly judicious restri.tlon i

501 F. 2d, at l5l, nevertheless considered it reversible

..{

Athough the portio, of the report containing the bank teller,sallqaed statemeni previously t"or ..r.uuJlna martea for identifi_cation, it was not introdueed into evidence.- wtun the discussionof the investigator,s testimony .ub*qu;;ii; arose, counsel for theGoverament noted that he had oofy

"'ti-ii.d opportunity to glauceat the statement, and he then requested arJosu.e of that portion ofthe report as well as the statement ,rrp"""al, made by thesalmman.

As indicated above, the bank teller did not deny having made thestatement recorded in the investigator's report. It is th"us por.iui.that

.the investigatorh testimon/ o" ilrilo*t would not haveconstituted an impeachment of the statements of that witness rvithinthe contemplation of the court,s

";;;-;;-*ould not ha'e gi'enrise to a duty of disclosure. Counsel diJ not pursue this point,however, and did not seek further .trrin."tioo of the issue. Re_spondent does not, nnd in view of the failu." to develop the issueat trial could not, urge this as a ground for reversal. Nor doesrespondent maintain that the initiai discrosure of the bank teiler,sstatement sufficed to satisfy the court,s order. we therefore con_sider each of the two alleged statements io-itu-."port

"

ilil;.;_ing statements that *ould h"ru b*" ,;bj..; to disclosure if theinvestigator had testffied about them.

230 OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Opinion of the Court 422rJ.s.

error. Citing Unt'teit States v' Wright' 160 U' S' App:

O. C. fZ, Og, agg F. 2d 1181, 1192 (1973)' the court found

that the Fifth Amendment prohibited the disclosure con-

ai i"" i."p"sed in this case' The court further held that

f"a. nrf" Crim. Proc' 16, while framed exclusively in

t".-.oi pretrial discovery, precluded prosecutorial dis-

covery at trial

".

*Jt. rdi r" 2d, at 157; accord 'Uy!1d

Stotni v- Wright, flPra, at 66-67' 489 F' 2d' at 1190-

1191. In each ,..p.tt, we think the court erred'

II

The dual aim of our criminal justice system is "thot

guilt shall not escape or innocence^ suffer"' Berger v'

(Jni.teil states,2g5 il. s. 78, 88 (1935)' To this end'

*e h",,,e placed our confidence in the adversary system,

"rl.urtins

to it the primary responsibility for develop-

ing ,"t"uint facLs or which a determination of guilt or

inio."n." can be made' See Umted States v' Ni*on'

418 U. S. 683, 709 (1974) ; Wiltinms v' Flonda'

igg u. s. 78, 82 (1970) ; Elkins v' united' states' 3M

U-.-S. ZOO, 234 (19d0) (Frankfurter, J', dissenting)'

-

Wt it" ih"

"dr"r.rry

system depends primarily 9" th9

parties for the pr.."nt'iion and exploration of relevant

iacts, the judiciary is not limited to the role of a referee

or-tup"."ito.. Its compulsory processes stand available

to require the presentaiion of evidence in court or be-

foru u grand iury. United States v' Nieon' supta;

-Kutisiv.

U*ei States,406 U' S' 441, &HM (19-7-2);.

iurina v. Woterlront Comm'n, 37.8 U' S' 52' 93-94

(1964) (Wurm, .i., concurring)' As we recently ob-

;;""d in United States v' Niaon, Eltpra' at 709:

"We have elected to employ an adversary system

of criminal justice in which the parties contest

-all

issues before a court of law' The need to develop

allre]evantfaptsintheadversarysystemisboth

UNITED STATES u. NOBLBS 23t

225 OPinion of the Court

fundamental and comprehensive. The ends of

criminal justice would be defeated if judgments

were to be founded on a partial or speculative

presentation of the fa,cts. The very integrity of

the judicial system and public confidence in the sys-

tem depend on full disclosure of all the facts, within

the framework of the rules of evidence' To ensure

that justice is done, it is imperative to the function

of courts that compulsory process be available for

the production of evidence needed either by the

prosecution or bY the defense."

Decisions of this Court repeatedly have recognized the

federal judiciary's inherent power to require the prose-

cution to produce the previously recorded statements of

its witnesses so that the defense may get the full bene-

fit of cross-examination and the truth-finding process

may be enhanced. See, e. g., lmnlcs v. United States,

353 U. S. 657 (1957);o Gordon v- United States,344

U. S. 414 (1953) ; Gotdmatt v. Urnted Stotes,316 U. S'

L2g (L942); Palermo v. Urui.ted States,360 U. S. 343, 361

(1959) (BnrNNeN, J., concurring in result). At issue

here is whether, in a proper case, the prosecutiou can

call upon that same power for production of witness

statements that facilitate "full disclosure of all the [rele-

vant] facts." Uni.ted States v. Ni.aun', s.LWa' at 709'

In this case, the defense proposed to call its investiga-

tor to impearh the identifieation testimony of the prose-

cution's eyewitnesses. It was evident from cross-ex&m-

ination that the investigator would testify that each

witness' recollection of the sppeara.nce of the individual

identified as respondent was considerably less clear at

6 The discretion recognized by the Court in Jerclcs subsequently

was circumscribed by Congress in the so-called Jencks Act, 18

U. S. C. S3500. See generally Palermo v. United Stotes,360 U' S'

3$ (1e59).

232 OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Opiniorr of the Court 422 U, S

an earlier time than it was at trial' It also appeared

that the investigator and one witness differed even as to

what the witness told him during the interview' The

investigator's contemporaneous report might provide

criticaiinsight into the issues of credibility that the in-

vestigator's testimony would raise' .

It could assist the

ju.y L determining the extent to rvhich the investigator's

i"rii*o.ty actually discredited the prosecution's wit-

nesses. If, for example, the report failed to ment'ion the

purported statement of one witrtess that "all blacks

ioot.a alike," the jury might disregard the investigator's

version altogether. On the other hand' if this statement

appeared in ttte contemporaneou-"ly recorded report' it

would teud strongly to corroborate tlie investigator's

version of the interview and to diminish substantially the

reliability of that witness' identification'n

It was therefore apparent to the trial judge that the

investigator's report was highly relevant to the critical

issue oI credibility. In this context' production of the

*O*, might sulstantially enhance "the search for

truth," W'it;nms v. Florida,399 U' S'' at 82' We must

determine rvhether compelling its llroductiotr rvas pre-

cluded by some privilege available to the defense in the

circumstauces of this case'

s Rule 612 of the new Federal Rules of Evidence entitles an ad-

verse party to inspect a writing relied on to refresh the recollee-

tion oi a witness while testiiying Thc Rule also authorizes

disclosure of writings relied on to refresh recollection before testi-

fyrng if the court deems it necessary in the interests of

il;i" The party obtaining the writing thereafter can use it in

"-o-.*"-inirg

tfr" witness ind tan introduce into evidence those

portiors that relate to the witness' testimony' As the Federal Rules

oi pria.n.. were not in effect at the time of respondent's trial'.we

have no occasion to consider them or their applicabilitl' to the situ-

ation here Presented.

UNITED STATES u. NOBLES

Opinion of the Court

233

III

A

The Court of Appeals concluded that the Fifth

Amendment renders crirninal discovery ,,basically a one_

way street." 501 F. 2d, at 154. Like many generaliza_

tions in constitutional law, this one is too broad. The

relationship between the accused,s Fifth Amendment

rights and the prosecution's ability to discover materiars

at trial must be identified in a more discrirninating

manner.

The Fifth Amendment privilege against compulsory

self-incrimination is an ,,intimate and persorrui oru,l,

which protects "a private inner sanctum of individual

feeling and thought and proscribes state intrusion to

extract self-condemn&tio..,, Couch v. United, Sfalcs, 40g

U. S. 322, 327 (1973); see also Bellis v. United States,

!!7 U.S. 85, 90-gl (t974); United States v. Wtite, 822

U. S. 694, 698 (1944). As we noted in Couch, surya,

at 328, the "privilege is a personal privilege: it adhlres

basically to the person, not to information that may in_

criminate him.",

In this instance disclosure of the relevant portions of

the defense investigator,s report would not impinge on

the fundamental values protected by the Fifth Amend_

ment. The court's order was limited to statements

7 "The purpose of the relevant part of the Fifth Amendment isto prevent compelled self-incrimination, not to protect private in_

formation. Testimony demanded of a witness ma1. be ver1. private

indeed, but unless it is incriminating and protected by the Amcnd_

ment or unlms protected by one of the evidentiary privileges, it must

be disclosed." Maness v. Meyers, 4lg U. S. 44g, +ZZJZi OSZS)(Wrrrro, J., concurring in result). Moreover, the constitutional guar_

lntee protects onll' against forced individual diselosure of n ,,testi-

monial or eommunicative nature,,, Schmerber v. Calilomia, Bg4 U. S.

757,761 (1966); see a.lso United Srcres v. Watte, Bgg U. S. ZlS, 222

(1967); Gilbert v. California, B88 U. S. 268 (1962)

2U OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Opinion of the Court 422 u. s.

allegedly made by third parties who were available as

witiesses to both the prosecution and the defense' Re-

spondent did not prepa,re the report, and there is no

suggestion that the portions subject to the disclosure

orIJ. ,"fl..ted any information that he conveyed to the

investigator. the fact that these statements of third

;;;i";".e elicited by a defense investigator on respond-

lnt's behalf does not convert them into respondent's per-

sonal communications. Requiring their production from

the investigator therefore would not in &ny sense com-

pel respondent to be a witness against himself or extort

communications from him.

We thus conclude that the Fifth Amendment priv-

ilege against compulsory self-incrimination, being per-

soial to the defendant, does not extend to the testimony

or statements of third parties called as witnesses at trial.

TheCourtofAppeals,relianceonthisconstitutional

guarantee as a bar to the disclosure here ordered was

misplaced.

B

The Court of Appeals also held that Fed' Rule Crim'

hoc.16deprivedthetrialcourtofthepowertoorderdis.

closure of ihe relevant portions of the investigator's re-

port.8 Acknowledging that the Rule appears to control

Otg*lqtcovery onty, thu court nonetheless determined

ERule 16 (c), which egtablishe the Government's reciprocal right

of pretrial discovery, excepts "reports, memoranda, or other internal

definse documents made by the defendant, or his attorneys or agents

in conuection with the investigation or deferse of the case, or of state-

ments made by the defendant, or by government or defense wit-

nesses, or by prospective government or defeuse witnesses' to the

defendant, his agents or attorneys'" That Rule therefore would

not authorize pretrial discovery of the investigator's report' Th"

propooed amendments to the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure

ieave this subsection substa.ntially unchanged. See Proposed Rule

16 of Criminal Procedure,62 F. P,'D'271,305-306 (1974)'

UNITED STATES u. NOBT.L\

Opiniou of the Court

235

?25

that its reference to the Jencks Act, lg U. S. C. $ 8500,

signaled an intention that Rure 16 should control triai

practice as well. We do not agree.

Both the language and history of Rule 16 indicate thatit addresses only prehial discovery. Rule 16 (f) requires

that a motion for discovery be filed ,,within l0 days'after

arraignment or such reasonable later time as the

court may permit," and further commands that it in-

clude all relief sought by the movant. When this pro-

vision is viewed in light of the Advisory Committee,s ad_

monition that it is designed to encourage promptness in

filing and to enable the distriet court to avoid unneces_

sary delay or multiprication of motione, see Advisory

Committee's Not€s on RuIe 16, lg U. S. C. App., p,. i;;,the pretrial focus of the RuIe becomes apparent. The

Go-vernment,s right of discovery arises only after thedefendant has successfully sought discovery under sub_

sectione (a)(2) or (b) and is,*n,ua to matters ,,which

the defendant intends to produce at the trial.,, Fed. Rule

$im.-Pr9c. lG (c). This haxdly suggests any intention

that the Rule would limit the court,J[o*er to order pro-

duction once trial has begun." pinaUy, tfre ea"iJo"v

Committee's Notes emphi,size ik fretrial character.

th.o* notes repeatedly characterizu tt

" Rule as

"

pio-

vision governing pretriel-disclosure, never once suggest-ing that it was intended to constrict a district court,s

0 Rulg 1-6 (S) impoees a duty to notify opposing couneel or thecourt of

'he

additional materials previouary

-requested

or inspectedthat are subject to discovery or inspection under the Rule, and itcontemplates thst this obligation wiU continue during trial. Th;obligatiou under Rule tO (g) jepe+e, no**.", on a previous requestfor or order of discovery. tnl faci tt , U* provision may have

::^i g"gt on the p"Iif, conduct during t.iU ao" oot

"oo*"tthe RuIe into a general limitation o" tU"Tou.t,6 inhsrest, power tocontrol evidmtiary Dsttem.

236

T"::J:::"::' 422rrs

control over evidentiary questions arising at trial' 18

U. S. C. APP., PP. 4493-495'

The incorporation of the Jencks Act limitation on the

pretrial right of discovery provided by Rule 16 does not

express a contrary intent. It only restricts the defend-

ani's right of pretrial discovery in a manner that recon-

ciles that provision with the Jencks Act limitation on

the trial court,s discretion over evidentiary matters. It

certainly does not convert Rule 16 into a general limita-

tiononthetrialcourt'sbroaddiscretionastoevidenti-

ary questions at trial. Cf ' Gites v' Margland' 386 U' S'

OO, fOf (1967) (Fortas, J', concurring in judgment)''o We

conciude, therefore, that Rule l6 in-rposes no constraint on

the District Court's power to condition the impeachment

testimony of respondent's witness on the production of

the relevant portions of his investigative report' In ex-

tending the Rule into the triai context, the Court of

Appeals erred.

IV

Respondent contends further that the work-product

doctrine exempts the investigator's report from disclosure

at trial. While we agree that this doctrine applies to

criminal litigation as well as civil, we find its protection

unavailable in this case.

The work-product doctrine, recognized by this Court

in Hirkm,on i. Taylor,329 U. S. 495 (1947), reflects the

strong "public policy underlying the orderly prosecution

ro we note also that the commentators who have considered Rule

16 have not suggested that it is directed to the court's control of

evidentiary questions arising at trial' See, e' g', Nakell, Criminal

Oir.o"urrjio. the Defense and the Prosecution-the Developing Con-

stitutional Considerations, 50 N. C' L' Rev' 437, 49+5L4 (1972);

R"rnu.k, The New Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, 54 Geo'

L. J. r2i6, 1279, 1282 n. 19 (1966); Note, Prosecutorial Discovery

Under Proposed Rule 16, 85 Harv. L' Rev' 994 (1972)'

UNITED STATES a. NOBLES 2gZ

225 Opinion of the Couri

arrd defense of legal claims.,, Id., at b10; see also fd.,

at 514-515 (Jackson, J., concurring). As the Court there

observed:

"Historically, a lawyer is an officer of the court

and is bound to work for the advancement of justice

while faithfully protecting the rightful interests of

his clients. In performing his various duties, how_

ever, it is essential that a lawyer work with & cer_

tain degree of privacy, free from unnecessary in_

trusion by opposing parties and their counsel.

Proper preparation of a client,s case demands that

he assemble information, sift what he considers to

be the relevant from the irrelevant facts, prepare his

legal theories and plan his strategy withoui undue

and needless interference. That is the historical and

the necessary way in which lawyers act within the

framework of our system of jurisprudence to pro_

mote justice and to protect their clients, interests.

This work is reflected, of course, in interviews,

statements, memor&nd&, correspondence, briefs,

mental impressions, personal beliefs, and count_

less other tangible and intangible ways_aptly

though roughly termed by the Circuit Court of Ap_

peals in this case as the ,work product of the Iawyer.,

Were such materials open to opposing

"oun..l on

mere demand, much of what is now put down in

writing would remain unwritten. An attorney,s

thoughts, heretofore inviolate, would not be his

own. Inefficiency, unfairnes,s and sharp practices

would inevitably develop in the giving of Lgat ad_

vice and in the preparation of cases for trial. The

effect on the legal profession would be demoraliz-irg. And the interests of the clients and the cause

of justice would be poorly served.,, 1d,., at Sl0_Ell.

The Court therefore recognized a qualified privilege for

238 OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Opinion of the Court 422U.5.

certein materials prepa,red by an a,ttorney "acting for

his client in anticipation of litigation." .Id., at 508."

See generaily 4 J. Moore, Federal Practice f[26.63 (2d ed.

L97D; E. Cleary, McCormick on Evidence 2M-209 (2d

ed.L972); Note, Developments in the Law-Discovery,74

Harv. L. Rev. 940,L027-1046 (1961).

Although the work-product doctrine most frequently

is asserted as a bar to discovery in civil litigation, its

role in assuring the proper functioning of the criminal

justice system is even more vital. The interests of so-

ciety and the accused in obtaining a fair and accurate

resolution of the question of guilt or innocence demand

that adequate safeguards assure the thorough prepara-

tion and presentation of each side of the case."

At its core, the work-product doctrine shelters the

mental processes of the attorney, providing a privileged

a,rea within which he can analyze and prepare his client's

c&se. But the doctrine is an intensely practical one,

grounded in the realities of litigation in our adversary

system. One of those realities is that attorneys often

must rely on the assistance of investigators and other

agents in the compilation of materials in preparation

for trial. It is therefore necessary that the doctrine

protect material prepared by agents for the attorney as

11 As the Court recognized in Hirkman v. Toylot,329 U. S., at

508, the work-product doctrine is distinct from and broader than the

attorney-client privilege.

12 A number of state and federal decisious heve recognized the

role of the work-produet doctrine in the criminal law, and have

applied its protections to the files of the prosecution and the ac-

cused alike. See, e. g., State v. Bowen, 104 Ariz. 138,449 P.2d

603, cert. denied, 396 U. S. 912 (1969); State et rel. PoUey v.

Supeior Ct. ol Santo Cntz County, 81 Ariz. 127,302 P.2d 263

(1956); Peel v. Stot,-, Lu So. 2d 910 (Fla. App. 1963); In re

Grond. Jurg Proceedin4s (Dufla v. United Stotes), 473 F. 2d' W

(CA8 1973); In re Terheltoub,256 F. Supp. 683 (SDNY 1966).

UNITED STATEII a. NOBT.r.s

225 Opinion of the Court

well as those prepared by the attorney himself.

over, the concerns reflected in the work_product

do not disappear once trial has begun. Discl, --s ot

an attorney's efforts at trial, as surely as disclosure dur_

ing pretrial discovery, could disrupt the orderly develop_

ment and presentation of his case. 'We need not, how_

ever, underta^ke here to delineate the scope of the doc-

trine at trial, for in this instance it is clear that the

defense waived such right a^s may have existed to invoke

its protections.

The privilege derived from the work-product doc_

trine is not absolute. Like other qualified privileges, it

may be waived. Here respondent sought to adduce ihe

testimony of the investigator and contrast his recollec-

tion of the contested statements with that of the prose-

cution's witnesses. Respondent, by electing to present

the investigator as a witness, waived the privilege with

respect to mattere covered in his testimony.r. Respond-

rs The sole issue in Hickmon related to materiars prepared by anattorney, and courts thereafter disagreed over whether ilu ao.irio.

applied as well to materiqtc p."prr"a on his behalf. S"" p;;;;J

Amendments to the Federal Rr-rres of civil procedr." na^trig-io

Discovery,48 F. R. D.4g7,50l (lg70); 4 J. Moore, f,uau.rf p-ra._

tic-e T26.63 tSl (2d ed. 1974). Necessarity, it must. This view isreflected in the Federal Rules of Civil procedure, see Rule 26 (b)(B),

and in Rule 16 of the Criminal Rules as well, see Rules fO (b)-anJ(c); cf. E. Cleary, McCormick on Evidence ios pa ed. l9z2i.1{ what constitutes a waiver wittr respect to work-product ma-terials depeuds, of cource, upon the circumstances. Counsel neces_sarily makes use throughout trial of the notes, documents, ana otlu.internal Eeterials prepared. to preseut adequately fi, Ai"rti *r",and often relies on them in eiamining witnesses. IVhen so used,there normally is no waiver.

-

But wheie, as here, counsel 611emptsto make s testimoniar use of these maieriars the normal rures'of

evidence come into play with respect to cross-examination andproduction of docu.ments.

2q OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Ophion r.rf the Court 422 U. S,

ent c&n no more advance the work-product doctrine to

sustain a unilateral testimonial use of work-product ma-

terials than he could elect to testify in his own behalf and

thereafter assert, his Fifth Amendment privilege to re-

sist cros-exarnination on matters reasonably related to

those brought out in direct examination. See, e' g', Mc-

Goutha v. Colifomit,402 U. S. 183' 215 (197L)."

v

Finally, our examination of the record persuades us

that the District Court properiy exercised its discretion

in this instance. The court authorized no general "fish-

ing expedition" into the defense files or indeed even into

the defense investigator's report' Cf' United States v'

Wright,160 U. S.App.D' C. 57,489 F. 2d 1181 (1973)'

Rather, its considered ruling was quite limited in scope,

opening to prosecution scrutiny only the portion of the

report that related to the testimony the investigator

would offer to discredit the witnesses' identification testi-

mony. The court further afforded respondent the ma:ri-

15 We cannot accept respondent's contention that the disclosure

order violated his sixth Amendment right to effective assistance

of counsel. This claim is predicated on the assumption that dis-

closure of a defeuse investigator's notes in this and similar cases

will compromise counsel's ability to investigate and prepare the

defense case thoroughly. Respondent maintains that even the

limited disclosure required in this case will impair the relationship

of trust and confidence between client and attorney and will inhibit

other members of the "defense team" from gathering information

essential to the effective preparation of the case' See American Bar

Association Project on Standards for Criminal Justice, The Defense

Function $3.1 (a) (App. Draft l97l). The short answer is that

the disclosure order resulted from respondent's voluntary electiou

to make testimonial use of his investigator's report. Moreover,

apart from this waiver, we think that the concern voiced by re-

spondent fails to recoguize the limited and conditional nature of the

court's order,

UNITED STATES u. NOBLES 24r

225 Opinion of the Court.

mum opportunity to assist in avoiding unrvarranted

disclosure or to exercise an informed choice to call for

the investigator's testimony and thereby open his report

to examination.

The court's preclusion sanction w&s an entirely proper

method of assuring compliance with its order. Re_

spondent's argument that this ruling deprived him of

the Sixth Amendment rights to compulsory process and

cross-ex&rnination misconceives the issue. The District

Court did not bar the investigator,s testimony. Cf.

l{oshington v. Teras, 888 U. S. 14, lg (1967). It

merely prevented respondent from presenting to the jury

a partial vierv of the credibility issue by adducing the

investigator's testimony and thereafter refusing to ais_

close the contempor&neous report that might offer fur_

ther critical insights. The Sixth Amendment does not

confer the right to present testimony free from the legiti_

mate demands of the adversarial system; one cannot

invoke the Sixth Amendment as a justification for pre_

senting what might have been a half-truth. Deciding,

as we do, that it was within the court,s discretion to as_

sure that the jury would hear the full testimony of the

investigator rather than a truncated portio. favorable

to.respondent, we think it would be artificial indeed to

deprive the court of the power to effectuate that judg_

ment. Nor do we find constitutional significance in th1

fact that the court in this instance was able to excrude

the testimony in advanee rather than receive it in evi_

dence and thereafter charge the jury to disregard it when

respondent's eounsel refused, as he said he rvould, to

produce the report.ru

16 Bespondent additionalry argues that certain statements by the

prosecution and the District court's excrusion of purported &pert

testimony justify reversal of the verdict, and that ihe Court of Ap_

peals' detision should be afrrmed on those grouuds. The Court of

2t2 OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Opinion of Wnrtn, J' 422U.5.

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Ninth

circuit is therefore

Reuersed.

Mn. Jusrrco Doucr,eg took no part in the consideration

or decision of this case.

Mn. Justrcn Wultr, with whom Mn. Jusrrco RosN-

eursr joins, concurring.

I concur in the judgment and in Parts II, III, and V of

the opinion of the Court. I write only because of mis-

givings about the meaning of Part IV of the opinion'

The Court appears to have held in Part IV of its opinion

only that whatever protection the defense investigator's

notes of his interviews with witnesses might otherwise

have had, that protection would have been lost when

the investigator testified about those interviews' With

this I agree also. It seems to me more sensible, how-

ever, to decide what protection these notes had in the

first place before reaching the "waiver" issue' Accord-

ingly, and because I do not believe that, the work-product

Appeals rejected respondent's challenge to the exclusiou of the testi-

*o.y of the proffered expert, 501 F. 2d, at 150-151' Respondmt

did uot present this issue or the qirestion involving the challenged

prosecutorial statements to this court in a cross-petition for

certiorari. without questioning our jurisdiction to consider these

alternative grounds for afrrmance of the decision below, cf. Lon4rws

v. Qreen,2S2 U. S. 531, 538 (1931); Dmtridge v' Willbms,397

U. S. 47i, 47H76, n. 6 (1970); see generally Stern, When to Cross-

Appeal or Cross-Petition--Certainty or Confusion?, 87 Harv' L' Rev'

Zria- (tSZa), we do not consider these contentions worthy of con-

sideration.' Each involves an issue that is committed to the trial

court,s discretion. In the abseuce of a strong suggestiou of an abuse

of that discretion or an indication that the issues are of suffcient

general importance to justify the grant of certiorari we decline to

entertein them.

UNITF;D STATES u. NOBLES 24J

225 Opinion of lVrrrrp, J.

doctrine of Hirkmonv. Taylor, B2g U. S. 4gS (tg47), canbe extended wholeeale frorn its iistoric ,ole as a rimitation

on the nonevidentiary material which may be tf,u

"uiljl.iof pretrial discoveryto an unprecedented role as a limita_tiorr on. the trial judge,s power to compel production ofevidentiary matter at trial, I add tt e ilUowing.

I

Up until now the work-product doctrine of Hirkmon v.Taylor, s,upra, has been ,iuwed almort o"frriulfy

as a limitation on the ability of a party to obtain pretriJldiscovery. It has not been ,ie*"a'r^. J,,lirnitrtion on thetrial court's broad discretion as to evidentiary O;;;;;at lliul." Ante, _at 296. The problern ai..r.*Jin Hickman v. Taylor

-&rose p."Ji.uty because, inaddition to accelerating the tim" *fr"" a party could

3btain-evidentiary matter from his &dversary,, the newFederal Rules of Civil procedure ,*"U, expanded thenature of the material subject to- pretrial

-disclosure.,

l Under criminal discovery rules the timc fa*tor is uot as great asmight otherwise appear. Federal nur. crlm. proc. 16 permits dis-covery through the time of trial; and under Fed. Rrr.'cil.-p;;.17 (c), evidentiary matter may be obtained punsuant to subpoenain advanee of triat in the discreilo, of tl"-nU iuagu.2 Prior to the Federal Rules, request" ioi witneo statements weregrant& or denied on the baeis of'*ilth;; ,h"y *u* evidence andnonprivileged. In the main, production was alniea, eitnei becarilwitness statemeats were not uriduo"" (rtuv-". inadmissible hearsayuntil and unless the wjtness testifies); b".;; a party is not en_titled to advance knowledge of fri, adrers&Ot .*, or because thestaternents were made by the client or his agent to his attornel. andthus eovercd by the attorney_client privileg-e. 4 J. Moore, FederalPractiee-T20.68t3l (2d ea. tSZ+1,'*t;;. cited therein. Thecases did not hold that witness statements *"i" gun...Ity privileged,if they were evidentiary, and had no .ru." to aeciae whether a work_product notion should protect them from discovery, .ir;; ;;;were nondiscoverable *yy3l under applicable discovef rules. B;ise Walker v. Strttthera, 2ZB llt. lg1,'il2 w.-p. SOf (1916).

2U OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Opinion of Wnrrn, J. 422 U. S.

Under the Rules, e party was, for the first time, entitled

to knorv in advance his opponent's evidence and w&s en-

titled to obtain from his opponent nonprivileged "infor-

mation as to the existence or whereabouts of facts"

relevant to a case even though the "information" w&s

not iLself evidentiary. Hickman v. Taglor, zupra, at 501.

Utilizing these Rules, the plaintiff in Hickman v. Taylor

sought discovery of statements obtained by defense coun-

sel from witnesses to the events relevant to the lawsuit,

not for evidentiary use but only "to help prepare himself

to examine witnesses and to make sure that he ha[d]

overlooked nothing." 329 U. S., at 513 (emphasis added).

In concluding that these statements should not be pro-

duced, the Court treated the matter entirely as one in-

volving the plaintiff's entitlement to pretrial discovery

under the new Federal Rules,' and carefully limited its

opinion accordingly. The relevant Rule in the Court's

view, Rule 26, on its face required production of the wit-

ness statements unless they were privileged. Nonethe-

Iess, the Court expressly stated that the request for wit-

ness statements was to be denied "not because the subject

matter is privileged" (although noting that a work-

product "privilege" applies in England, 329 U. S., at 510

n. 9) as that concept was used in the Rules, but because

the request "falls outside the &rena of discouery." Id., at,

510 (emphasis added). The Court stated that it is essen-

tial that a lawyer work with a certain degree of privacy,

and concluded that the eflect of giving one lawyer's work

(particularly his strategy, legal theories, and mental im-

pressions) to another would have a "demoralizing" effect

on the legal profession. The Court then noted that wit

3 Mr. Justice Jackson's concurrence is even more express on this

point. It states: "[T]he question is simply whether such a demrnd

is authorized by the rules relating to various aspects of 'discovery."'

329 U. S., at 514.

UNITED STATES a. NOBLES 245

225 Opinion of Wrrrrn, J.

ness statements might be admissible in evidence under

sorne circumstances and might be usable to impeach orcorroborate a witness. However, it concluded that inthe case before it the plaintiff wanted the statements forpreparation only and had shown no re&son why he

could not obtain everything he sought by doing his ownwork rather than utilizing that of hi" adrr"rsary.

The conclusion that the work product of a iawyer isnot "privileged,, made it much more difficult ior tt eCourt to support its result. Nothing expressed in theRule supported its resurt, and the court was forced toexplain its decision by stating:

"When Rule 26 and the other discouery rules were

adopted, this Court and the members o1 thu bar ingeneral certainly did not believe or contemplate thatall the fi"les and mental processes of lawyers were

thereby opened to the frel scrutiny of their adver-

s&ries." Id., at 514. (Emphasis added.)

I am left with the firm conviction that the Court

avoided the easier route to its decision for a reason. iohave held an attorney,s work product to be ,,privit"gud;

would have been to limit its use at trial as evidencle inthose cases in which the work product qualified as evi_

{eace, see Report of proposed Amendments to Rules ofCi'il Procedure for the District Courts of the Linited

States, S F. R. D.4A8,460 (1946), and, as Mr. Justice

Jackson stated in his concurring opinion, a party is en_titled to anything which is "evldence in his case.,, B2gU. S., at 515..

a Mr' Justice Jackson also emphasized that the witness statementsinvolved in Hickman v. Taylor were neither evidence ,ro, p.inil.SJI-d.,.at 576. .Indeed, most of the m.aterial iesc.i."d bi.the Court asfalling under the work-product umbrella Joo ,ot qualify as evi-dence' A lawyer's menta.l impressions

"* ,r*o.t never evidence and

Since lliclc'ttw,n Y. Taylor, supra' Congress' the cases'

snd the commentators have uniformly continued to view

ti" "*ort product" doctrine solely as a limitation on

pretrial discovery and not as a qualified evidentiary priv-

it"g". In 1970, Congru,'became involved with the prob-

t"ri fo, the first tirie in the civil area' It did so solely

by accepting e proposed amendme.nt to Fed' RuIe Civ'

pr*. 26, *'hi.t incorporated much of what the Court

held in Hickmanv. Tiylor, supra,with respect to pretrial

ai*.tr. See Advisory Committeds explanatory state-

*"rrt, Zg U. S. C. App', p' 7778'- In the criminal area'

Congress has enactei'ig-u' S' C' S3500 and accepted

tr'ed]nule Crim. Proc. 16 (c) ' The former prevenLs pre-

trial discovery of witness statements from the Govern-

ment; the latter prevents fretlla'| discovery of witness

statements f"om ihe defense' Neither limit's the power

of the trial court to order production as evidence of prior

statements of witnesses who have testified at trial'o

Withthe"*."p,i*-ofmaterialsofthetypediscussed

in Part ill, infra, reseaxch has uncovered no application

of the work-product rule in the lower courts since Hb'k-

mon to prevent production of evidenc+-impeaching or

out-of-court statements of witnesses are generally inadmissible

hearsay. Such t*i"^t"L become evidence only when the

witness testifies at- irial, and &re then usually impeachment

evidence only. This ;'of course' iuvolves a situation in which

the relevant witness was to testify and thus preseuts the ques-

tion"not involved b Hiclunon v' Taylnt-whether prior :i::-

-"o," .frorfa be disclosed under the trial judge's power over evl-

UNTTED STATES a. NOBLES 242

225 Opinion of Warra, J.

otherwise-at trial; 6 and there are several examples of

cases rejecting such an approach.'

Similarly. the commentators have all treated the at_torney work-product rule solely as a limitation on pr"_

!1t-aiscovory, a.g.,4 J. Moore, Federal practice fitiO._63-26.64 (2d ed. r9z_g;8 c. wright & A. Miller, FederalPractice and Procedure g 2026 f fgZOi; 2A W. Ba^rron &A. Holtzoff, Federal practice ana'no"edure g 682 fW.iglried. 1961), and some have expressly stated that it does not

Tlly to evidentia^ry matter. F. James, Civil hocedure

?1, I 13 (tgOS) ; 4 J. Moore, F,ederal practice ll l6rtt8.{l (1e63).

OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Opinion of Wnrrn, J' aza.s.

The reasons for largely confining the work_product

rule to its role as a limitation on pletrial discorery 8rucompelling. First of all, the injury to the factfinding

deutiary matters at trial'

5In n. 13 of rts opiJoo, the Court cites Fed' Rule Crim' Proq'

16 (c), as containing ti"-*oif-ptoduct n:le' In n' 10' the Cou+ I

correctly notes that nJ iO i.l'i" not "directed to the court'e co{- |

trol of evidentiary Ot*io; "*tg

at trial'"- It eeems to'ne' tU{g/\

this suppliea a better ;; i"i tn-" Court's decigion tha'n "waiver'" \

^

oThe- majority doT^^liF one case, In re Terkeltoub, 256 F.Supp. 683 (SDllY 1966), in ,hi.h' th; court referred to thework-product doctrine in preventing th" Goven nent fmm inquiringof a lawyer before the gr&nd jury-whuth".-;u had participated inylornins lerjury of a prospective witness while preparing a crim_inal sase for trial. I *, ev.e1t, a grand jury investigation is insome respects nimital t9 nretrial discovery.

-Cb.p"r"

fi i" errfr

!:l_P,o:?rar!ss (Dufiy

" -yitr! ltiiy,4zz F. 2d s4o (cAs1973), wirh Schwimmcr^:.lyi?a Stotes,'ZZZ f. Za SSS-fieillcert. denied,352 U. S. gSB (1956). tre pmper scope of inquiry isas broad, and it cau be-used aa's way Ji ir.pn iog for the latercriminql trial' There is for-example

" rprii i authority on whetherthe work-product nrre applies to'Ins L-_ iivestgatious. compareUnited States v. McKay,B!2 F. Za Ui f,i,s 196Z), wirh UnitedSrates v. Broutn,4ZBF.2d 10SS (CAt 19ZSi.---

1 Shw v. 'Wuttke,2g

Wis. ?1, W, lfusl, rB7 N. W. 2d 649,652-653 (1965); State ez-rcL S-tate ti;siiou do*m,n u. S;ri;;;,,7j { M. 6t7,62M2t, 4t7 p.2d +sr, isz;e (1966); E. r. du pont

de Nemours & Co. v. philtips-petrotur* eo, U F. R. D. 416 (Del.7959); United Staies ":y*Iu,154 F. Srp;. 524 (EDNi ir5?i,United States v. Sun Oil Co.,.ro f. n.-5.-sae tnO pa. 1954);United Stat44 v. Gateq 85 F. R: D. SZ tCofo.' fg64l .

28 OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Opinion of WnIte, J. 422U.5.

process is far grea,ter where a' rule keeps euidence from

ihe factfinder than when it simply keeps advance dis-

closure of evidence from a party or keeps from him leods

to evidence developed by his adversary and which he is

just as well able to frnd by himself' In the main, where

a party seeks to discover a statement made to an oppos-

irg purtv in order to prepare for trial, he can obtain the

"rib.turti"t equivalent ' . . by other means," Fed' Rule

Civ. Proc. 26 (b)(3), i. e., by interviewing the witness

himself. A prior inconsistent statement in the possession

of his adversary, howel'er, when sought for evidentiary

purpo,ses.-i. e., tn impeach the witness after he testifies--

is for that purpose unique. By the same token, the dan-

g". p"r".iu"d,in Hickman that each party to a case will

decline to prepare in the hopes of eventually using his

adversary's preparation is absent when disclosure will

take place only at trial. Indeed, it is very difficult to

articulate & reaaon why statements on the same subject

matter as a witness' testimony should not be turned

over to an adversa.ry after the witness has testified' The

statement will either be consistent with the witness'

testimony,inwhichcaseitwillbeuselessanddisclosure

will be harmless; or it will be inconsistent and of un-

questioned value to the jury. Any claim that disclosure

of such a statement would lead the trial into collateral

and confusing issues was rejected by this Court rn Jenclcs '

v. Unitetl States,3s3 U. S. 657 (1957), and by Congress

in the legislation which followed'

The strong negative implication in Hi'ckman v' Taylor'

tutpra, that the work-product rule does not apply to

evidentiary requests at trial became a holding in Jercks

v. Uniteit States, supra- There a defendant in a

criminal case sought production by the Government at

trial of prior statements made by its witnesses on the

same subject matter as their testimony' The Govern-

UNITED STATES u. NOBLES 249

225 Opinion of \Vrrrru, J.

ment argued, inter alia, that production would violate the

"'legitimate interest that each party-including the Gov-

ernmenL-has in safeguarding the privacy of its files., ,,

353 U. S., at 670. The Court held against the Govern-

ment. The Court said that to deny disclosure of prior

statements which might be ured to impeach the witnesses

was to "deny the accused euidence relevant and material

to his defense," id., at 667 (emphasis added). Also re-

jected as unrealistic was any rule which would require the

defendant to demonstrate the impeachment value of the

prior statements belore disclosure,' and the Court held

that entitlement to disclosure for use in cross-examina-

tion is "established when the reports are shown to relate

to the testimony of the witness." Id., at 66g. Thus,

not only did the Court reject the notion that there was

& "work product" limitation on the trial judge,s discre-

tion to order production of evidentiary matter at trial,

but it was affirmatively held that prior statements of a

witness on the subject of his testimony are the kind of

evidentiary matter to which an adversary is entitled.

Indeed, even in the pretrial discovery area in which

the work-product rule does apply, work-product notions

have been thought insufficient to prevent discovery of

eui.dentiliry ond impeochment material. In Hirkmon v.

Taylor,329 U. S., at 511, the Court stated:

"We do not mean to say that aJI written materials

obtained or prepared by an adversary,s counsel with

an eye toward litigation &re necessa^rily free from

discovery in all cases. Where relevant and non-

8 The Court tn Jencks quoted the language of Mr. Chief Justice

Marshall n United States v. Burr, 25 F. Ca.s. 187, 191 (Va. ig07):

"'Now, if a paper be in possession of the opposite par[y, what

statement of its contents or applicability can be expected from the

person who claims its production, he not precisely knowing its con-

tents?'" 353 U. $., at 668 n. 12.

250 OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Opinion of Wxrtr, J. 422U.5.

privileged facts remain hidden in an attorney's file

urrd *hu." production of those facts is essential to

the preparation of one's case, discovery ma'y prop-

erly be had. Such written statements and docu-

merts might, under certain circumstances' be od-

missible in euiilence or give clues as to the existence

or location of relevant facts' Or they might be use-

ful for purposes of impeachment or corroboration'"

(Emphasis added.)

Mr. Justice Jackson, in concurring, was even more ex-

plicit on this point. See zupro, at245' Pursuant to this

irrgurgu, the lower courts have ordered euidence to be

;;;;d ";"r

pretrial even when it came into being as a

result of the a.dversary's efiorts in preparation for trial''

A member of a defense team who witnesseg &n out-of-

.ouri statement of someone who later testifies at trial

in a contradictory fashion becomes at that moment a

witness to a relevant and admissible event' and the cases

cited above would dictate disclosure of any reports he

sClntmilLgsv.BeLlTelephoneCo'olPen'nwluania'47F'R'D'

3ru

-iED

P;. 1968) ; Mo,tu v' Gos Seruice Co'' 168 f' Surn' !!l

iWr- nn"- iSSA);

'

Mqin'nis v' Westinghouse Electric Corp'' 2Ul

i'. S"pp Zm tBO f"' 862); Julitts Hgmon' & Co' v' Ameican

Moto*ts Ins. Co.,17 F. R. O' S86 (Colo' 1955); Ponett v' Fgxl

Motor Co.,47 F. if. D. 22 (WD Mo' 1968) ;-Scrd'ei v' Bostqn lru'

Co., U F. R. D' 463, 468 (Del' 1964) (each involving a situation

in which a member of a litigation team witnessed au event or scene

in the course of preparing-" t'"" for trial and the court ordered

disclosure of his report of the event) ; Bourget v' Gouetnment Em-

;l":s;;t Ins. Co.,€ f. n. D.29 (Conn' 1969); McCu)loush Tool Co'

,. ion Geo Atlas corp.,40 F. R. D. 490 (sD Tex. 1966) ; o'Boyle v.

t;fitns. Co. ol Notih Amenco,299 F' Supp' 704 (WD Mo' 1969)'

Ci. Loilorro r. Stot" Farm Mutual Automobi)e Ins' Co'' 47 F' R' D'

278 (WD Pa' 1969), and, Kenncdy v' Sengo,s2 F' R' D' 34 (WD

Pa. 1971) (in each of which the preparation for trial was the sub-

jeet of the suit); see also Notto v' Hogan,392 F' 2d 686' 693 (CA10

isos); F. Ja.mes, Civil Procedure 211 (1965)'

UNITD STATE u. NOBT,ES 2Sr

?25 Opinion of Wrrnr, J.

may have written about the event.'o Since prior state-

ments are inadmissible hearsay until the witness testifies,

there is no occasion for ordering reports of such state-

ments produced as evidence pretrial. However, some

courts have ordered witness statements produced pretrial

in the likelihood that they will become impeachment

evidence.tt Moreover, where access to witnesses or to

their information is unequal, discovery of their state-

ments is often grented solely to help a party prepare f.or

trial regardless of any eventual evidentiary value of the

out-of-court statements. See Proposed Amendments to

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Relating to Dis-

covery,48 F. R. D., at 501.

Accordingly, it would eppear that with one exception

to be discussed below, the work-product notions of Hink-

trutn v. Toylor, iltpro, impose no restrictions on the trial

judge's ordering production of evidentiary matter at trial;

that thege notions spply in only a very limited way, if

at all, to a party'e efrorts to obtain eui.d,ence pretrial pur-

suent to available discovery devices; and that these

notions supply only e qualified discovery immunity with

respect to witness sta,tements in any event.r2

10The holding':m Jencks v. United States, B5B U. S. 652 (1957),

would put to rest any claim that zueh prior statement would be

disdossble only if the adversary est&blishd its evidentiary value

a.head of time by specifc proof that it was inconsistent.

rrVetter v. Louett,,l4 F. R. D. 465 (WD Tex. lgffi); McDonatil

v. Proudl,cy, 38 F. R. D. I (WD Mich. l96E); Tanrunbaum v.

Walker, 16 F. R. D. 570 (ED Pa. 1954); Futton v. Suift,4B

F. R. D. 166 (Mont. 1967); Bepublic Geor Co. v. Borg-Worncr

Cory.,38L F. 2d 551, 557-558 (CA2 1967) (in camera inspection).

Cl. Goosrnan v. A. Duie Pyle, 1nc.,320 F. 2d 4E (CA4 1968). For

caaes contr& see 4 J. Moore, Federal Practice 120.64 [B] n. 1a (2d

'ed. 1974).

trThe majority stat€s:

"Moreover, the coucems reflected in the work-product doctrine

do not disappear onee trial h8s begun. Disclosure of an attorney,e

252 OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Opinion of WHrtP, J' 422 U. S.

II

In one of its a^spects, the rule of' Hickman v' Taylor'

supra, has application to evidentiary requests "t -1t]{'

Both the majority and the concurring opinions in Hick-

rnanv. Taylor were at pains to distinguish between pro-

duction of statements written by the witness and in the

,or**i"" of the lawyer, and those statements which were

;;" orally bv the *it"tt" and written down by the

i"*ru". Production and use of oral statements written

down by the lawyer would create a substantial risk that

,i" iu*i"" *ould have to testify'" The majority said

that this would "m&ke the attoruey much less an officer

effortsattrial,assurelyasdisclosureduringpretrialdiscovery'

."rfi-ai.*rt the orderlydevelopment and.presentation of his case'

We need not, however,

-uoitttutt"

here to delineate the scope of the

doctrine at trial, for in this instance it is clear that the defense

waived such right ," -uV hn* existed to invoke its protections'"

Ante, at 239'

not when the docu-

As noted above, the important questron rs

ment in issue is ueat;;';;- ;"n *he" it is to be produced'

The important q,r.stion i'

-whether

the document is sought for

evidentiary o, i-p."ti--t* pu'pot"t or whether it is sought for

preparation purposes ffi' df *u"t' a party should not be able

to discover ni" oppootois legat tt-oond" or statements of wit-

nesses not called whethl, ni ,"quust is at trial or before triel'

Insofar as such u ,"quo, is made under the applicable discovery

rules, it is within tne Je of Hhkmon v' Toytor even though made at

triat. Insofar ". tU" I"quttt ttuttt to invoke the trial judge's dis-

cretion over evidentiary-matters a,t trial' the rule of Hickmon v'

Toylar is unnecessary,"io* 'o

oie could,ever sugget that legal

memoranda o, l*oti t*it^*" are evidence' If this is all the

;;;il' ;.*" bv the above-quoted language' I agree'

13 If the witness ao""

-'ot

acknowledge making an inconsistent

statement to th. h;;;;;n though the lawyer recorded-it-the

cross-examine, -"y oJ offer the documeot -in evidence without et

least calliug tne bwyer as a witness to authenticate the documeut

and otherwise testify to the prior statelnent'

UNITED STATEII u. NOBT.rs 253

225 Opinion of Wnrru, J.

of the court and much more &n ordinary witness." 329

U. S., et 513. Mr. Justice Jackson, in concurring, stated:

"Every lawyer dislikes to take the witness stand

and will do so only for grave reasons. This is partly

because it is not his role; he is almost invariably a

poor witness. But he steps out of professional cha,r-

acter to do it. He regrets it; the profession dis.

courages it. But the practice advocated here is one

which would force him to be a witness, not as to

what he has seen or done but as to other witnesses'

stories, and not beeause he wants to do so but in

self-defense." Id., at 517.

The lower courts, too, have frowned on a.ny practice under

which an attorney who tries a c&se also testifies as a

witness, and trial attorneys have been permitted to testify

only in certain circumstances."

The remarks of the Court in Hitkmnn v. Taylor,

$tpra, while made in the context of a request for pretrial

discovery have application to the evidentiary use of

lawyers' memoranda of witness interviews at trial. It is

unnecess&ry, however, to decide in this case whether the

policies against putting in issue the credibility of the

lawyer who will Bum up to the jury outweigh the jury's

interest in obtaining all relevant information; and

whether lencks v. United States, $tpra, and 18 U. S. C.

rrUnited States v. Porter, 139 U. S. App. D. C. 19, 429 F.24,

203 (1970) ; United Srates v. Fiorillo, 376 F. 2d 180 (CA2 1967) ;

Gajewski v. United Statu,32l F. 2d.261 (CA8 1963), cert. deu.,

375 U. S. 968 (196a); United Statet v. Newmon,476 F. 2d.733

(CA3 1973) ; Trauelers Ins. Co. v. Dykes, 395 F. 2d 747 (CAi

1968); United. States v. Alu, 246 F. 2d 29 (CA2 1957); United

Stores v. Chiarella, 184 1'. 2d 903, modified on rehearing, 187 F. 2d

L2 (CA2 1950), vacated as to one petitioner, S4l U. S.946, cert.

deniqC as to other petitioner sub nom. Stancin v. United. Srares, 341

U. S. 956 (1951); United Stales v. Clnnr,y,276 F.2d 617 (CA7

1960), rev'd on other grounds, 365 U. S.312 (1961).

2U OCTOBER TERM, 1974

Opinion of Wnrtn, J. 422 U. S.

$ 3500 are to be viewed as expressing a, preference for

disclosure of all fapts." In this case, the creator of the

memorandum was not the trial lawyer but an investi-

gator'6 and he was, in any event, to be called as a witness

by the defense. Accordingly, I would reverse the judg-

ment below because, quite apart from waiver, the work-

product rule of Hitkman v. Taylor, su'pra, has no appli-

cation to the request at trial for evidentiary and impeach-

ment material made in this case.

15 The cases have held records of witness statements made by

prosecutors to be disclosable uoder 18 U. S. C. $ 3500, Uniteil Statas

v. Hilbich,341 F.2d 555 (CA7), cert. den.,38l U. S.941, reh. den.,

382 U. S. 874 (1965), and 384 U. S. 1028 (1966); United Stdes v.

Aui)es,3l5 F.2d 186 (CA2 1963); Saunders v. United States, ll4

U. S. App. D. C. 345, 316 F. 2d 346 (1963); United Stajes v.

Smaldone,4&t F. 2d 311 (CA10 1973), cert. den., 415 U. S. 915

(1974). Cf. Conaday v. United States,354 F.2d 849 (CA8 1966)'

It Stote v. Bouten, 104 Ariz. 138, 449 P. 2d 603 (1969), tle court

rea,ched a contrary result under state law.

ro A conflict aro6e smoDg lower federal courts over the questiou

whether the work product of members of a litigation team otler than

the lawyer was protected from discovcry by the nrle of Hickman

v. Toylor, supro. Ghent, Development, Since Hickman v. Taylor, of

Attorney's "Work Product" Doctrine, 35 A. L. R. 3d 438-440 (S$ 7

[a] and [b]) and 45H55 ($$15[a] and [b]) (1971); Proposed

Amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Relating to

Discovery, 48 F. R. D. 487, 501-502 (1970). With respect to

discovery in civil cases under Fed. RuIe Civ. Proc. 26,

the conflict was resolved in the 1970 amendments by af-

fording protection to documents by a party's "representative,"

whether a lawyer or not. Where the purpose of the rule protecting

the work product is to remove the incentive a party might other-

wise have to rely solely on his opponent's preparation, it is sensible

to treat preparation by an attorney and an investigator alike'

However, the policy against lawyers testifying applies only to the

lawyer who tries the case.

FAA ADMINISTRATOR u. ROBERTSON 255

Syllabus

ADMINISTRATOR, FEDERAL AVIATION ADMIN-

ISTRATION, nt

^L.

u. ROBERTSON nr er'.

CERTIORANI TO TIIE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

TEE DISTRICI OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 74450. Argued April 15, 1976-Decided June 24, L975

Respondents requested the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

to make available Systems Worthiness Analysis Program (SWAP)

Reports which consist of the FAA's analyses of the operation and

ma.intenance performance of eomnrercial airlines. Section I104 of the

Federal Aviation Act of 1958 permits the FAA Administrator,

upon receiving an objection to public disclosure of information

in a report, to witlthold disclosure when, in his judgment, it wor:Id

adversely affect the objecting party's interest and is not required in

the public's interest. The Administrator declined to make the

reports available upon receiving au objection from the Air Trans-

port Association, which claimed that confidentialitl' was nece-

sary to the effectiveness of the program. Respondents sued in the

District Court seeking, inter alio, the requested documents' The

District Court held that the documents were "as a matter of

law, public and non-exempt" within the meaning of thc Freedom

of Inlormstion Act (FOIA). The Court of Appeals affirmed the

judgment of the D.strict Court "insofar as appellants rely upon

Exemption (3)" of the FOIA. Held: The SWAP Reports are ex-

empt from public disclmure under Exemption 3 of the FOIA as

being "specifically exempted from disclosure by statute'" Pp'

26L-267.

(a) Exemption 3 contains no "built-in" standard as do some

of the exemftions under the FOIA and the Ianguage is zufficiently

ambiguous to require resort to the legislative history' That his-

tory-reveal"thatCongresswas..&wareofthenecessitytodeal

expressly with inconsistent laws," and, as indicated in its com-

miitee report, did not intend, in enacting the FOIA, to modify

the numerous statutes "which restrict public access to specific

Government records." Respondents can prevail only if the FOIA

is read to repeal by implication all such statutm' To interpret

"specific" as used in sueh committee reference as meaning that

Exemption 3 applie only to precisely uamed or described docu-

mentqwouldbeaskingCongresstoperformanimpossibletask