Lasky v. Quinlan Opinion

Public Court Documents

July 29, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lasky v. Quinlan Opinion, 1977. 297e58b0-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8814b283-3cbd-49d6-a2e6-54f35ce0c783/lasky-v-quinlan-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

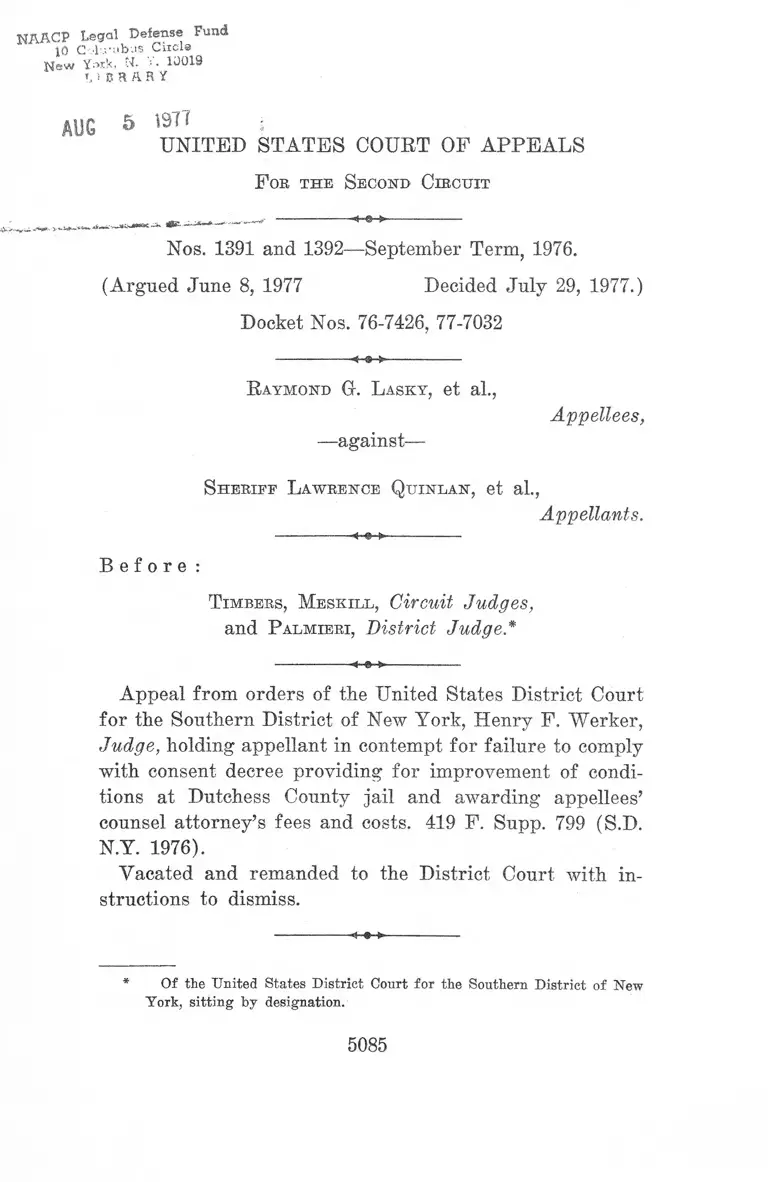

ACP L egal D efense Fund

10 C'.lu’ubus Circle

New Y.-wk, N. V. 10019

», > B R A R Y

AUG 5 1977 *

UNITED STATES COUNT OF APPEALS

F or the Second Circuit

Nos. 1391 and 1392— September Term, 1976.

(Argued June 8, 1977 Decided July 29, 1977.)

Docket Nos. 76-7426, 77-7032

R aymond G-. L asky, et al.,

—against—

Appellees,

Sheriff Lawrence Quinlan, et al.,

Appellants.

B e f o r e :

T imbers, Meskill, Circuit Judges,

and P almieri, District Judge.*

Appeal from orders of the United States District Court

for the Southern District of New York, Henry F. Werker,

Judge, holding appellant in contempt for failure to comply

with consent decree providing for improvement of condi

tions at Dutchess County jail and awarding appellees’

counsel attorney’s fees and costs. 419 F. Supp. 799 (S.D.

N.Y. 1976).

Vacated and remanded to the District Court with in

structions to dismiss.

Of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New

York, sitting by designation.

5085

Jack P. L evin, Esq., 1 Chase Manhattan Plaza,

New York, New York 10005, for Appellees.

P eter E. K ehoe, Esq., 37 First Street, Troy,

New York 12180, for Appellants.

Palmieri, J .

This action was commenced on April 16, 1973 by the

filing of a pro se class action complaint by five inmates

at the Dutchess County Jail (the “ jail” ) in Poughkeepsie,

New York. The complaint sought injunctive and declar

atory relief, and alleged violations of the inmates’ consti

tutional rights and violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1983 by Sheriff

Lawrence M. Quinlan and certain jail personnel. Juris

diction was invoked under 28 IT.S.C. §§ 1343 and 2201 and

42 IT.S.C. § 1983.

The District Court appointed counsel to represent the

inmates, conducted an evidentiary hearing, and made a

personal inspection of the jail in the company of counsel

for both sides and a court reporter. Thereafter, at the

suggestion of the District Court, counsel for both sides

entered into a stipulation, dated July 25, 1973, providing

for the implementation of improvements by the Sheriff

with respect to certain conditions at the jail. The Court

approved the stipulation by order dated July 30, 1973 and

added as a further requirement that the Sheriff post a

new set of rules and regulations consistent with the stip

ulation and provide each inmate with a copy of it upon

his admission. The Court stated that as a result of the

hearing and inspection of the facility it was of the opinion

that the jail was “a generally acceptable institution in con

stitutional terms . . . [with] room for improvement in

certain respects.” The Court determined that in view of

the stipulation “ there is no need to declare this a class

5086

action, since I can find nothing substantial in a constitu

tional sense that is likely to be added because of a class

determination.” The Court dismissed the action upon the

filing of the stipulation, “ subject to reopening- or the in

stitution of contempt proceedings in the event of a willful

failure to comply with the aforesaid order of the Court.”

The stipulation provided for the improvement of condi

tions in ten general areas. First, it required that pre-trial

detainees not occupy the same rooms with convicts under

sentence and that minors not be housed in the same rooms

with adults. Second, it set forth certain requirements with

respect to personal hygiene, including the laundering of

linen, bedding, and institutional clothing and the bathing of

inmates. Third, it provided for several changes in the ad

ministration of health services, including the availability

of medical examinations and treatment, the maintenance

of records, and the improvement of present health service

facilities. Fourth, the stipulation set forth certain min

imum sanitation standards for the jail’s kitchen and food

service staff and required that these facilities be inspected

regularly by public health authorities on the same basis as

restaurants serving the public. The fifth provision re

quired that the jail’s outdoor exercise and recreational

area become operational within six months of the Court’s

approval of the stipulation.

The sixth, seventh and eighth provisions of the stipula

tion concerned inmate communication, reading materials

and legal assistance, respectively. With respect to com

munication, the stipulation provided for notice to inmates

of any restrictions on correspondence, set forth the basis

on which incoming mail could be censored and the pro

cedures to be followed for censored mail, and established

rules for inmates’ use of telephones. With respect to read

ing materials, the stipulation set forth the basis on which

5087

reading material could be censored. With respect to legal

assistance, the stipulation provided that inmates who were

unable to secure counsel in civil or criminal matters would

be permitted to consult with other inmates for such pur

poses.

The ninth provision set forth a series of conditions to be

observed in the event that an inmate was disciplined by

way of confinement in a cell apart from other inmates or

placed on a restricted diet. It further provided for the

supervision and, if necessary, the medical examination of

inmates whose physical or mental conditions created a risk

of their endangering themselves or other inmates or a need

for requiring protection from other inmates. In addition,

the Sheriff was required to promulgate and post in a

prominent place a list of the rules and regulations govern

ing inmate conduct and the standardized procedures re

lating to it.

Finally, the tenth provision required that alterations

and repairs to the physical plant be effectuated to provide

for adequate lighting, heating, ventilation and plumbing

facilities. Within thirty days of the approval of the stip

ulation, the Sheriff was required to submit to the District

Court a plan for the implementation of the third, fifth and

tenth provisions of the stipulation.

On December 8, 1975, plaintiffs’ counsel moved for an

order (1) adjudging Sheriff Quinlan in civil contempt for

his alleged failure to comply with the Court’s order of

July 30, 1973, approving the stipulation; (2) compelling

compliance with that order; and (3) awarding plaintiffs’

counsel reasonable attorney’s fees and the costs incurred

in prosecuting the contempt action. The matter was re

opened, and a four day hearing on the motion was held

before Judge Werker of the Southern District of New

York. In an opinion dated June 21, 1976, Judge Werker

5088

held that Sheriff Quinlan had failed to comply with sub

stantially all of the provisions of the stipulation in the

lengthy period following its approval. 419 F. Supp. 799

(S.D.N.Y. 1976). Although the Court stated that it was

unnecessary for its adjudication of contempt to find that

the Sheriff willfully failed to comply, it found that plain

tiffs had demonstrated such willfulness with respect to

several provisions of the stipulation. In an order dated

July 7, 1976, pursuant to this opinion, the Court assessed

a fine of $500 against the Sheriff, ordered that he pay the

attorney’s fees and expenses incurred in connection with

the contempt proceeding, and ordered that he comply with

the stipulation or submit a plan for compliance within 30

days or be fined $50 per day thereafter until he filed such

a plan and it was approved by the Court. After a hearing,

the Court allowed plaintiffs’ counsel attorney’s fees in the

amount of $35,000 and disbursements in the amount of

$9,573.48. Judgment in the amount of $44,573.48 was en

tered on December 13, 1976, and Sheriff Quinlan filed a

timely notice of appeal.

Although Sheriff Quinlan has asserted several arguments

on appeal, the Court need not reach any of the issues raised

because it has concluded that the judgment of contempt

must be vacated on the ground that the action is moot. All

five of the named plaintiffs were no longer in custody in

the Dutchess County jail at the time the contempt pro

ceeding was commenced. Since the District Court denied

class certification in its order approving the stipulation,

there is no longer any party to this action having an in

terest in the enforcement of the consent decree. Thus, the

case is moot and this Court is without jurisdiction. See

North Carolina v. Rice, 404 U.S. 244, 246 (1971); Ringgold

v. United States, 553 F.2d 309, 310 (2d Cir. 1977).

In the absence of a class certification, the plaintiffs can

not prosecute the action on behalf of present inmates of

5089

the Dutchess County jail under the relaxation of the moot

ness doctrine provided by Sosna v. Iowa, 419 U.S. 393

(1975). Board of School Commissioners v. Jacobs, 420 U.S.

128 (1975); Boyd v. Justices of Special Term, Part I, 546

F.2d 526 (2d Cir. 1976). Moreover, the exception to the

timely certification requirement established in Gerstein v.

Pugh, 420 U.S. 103 (1975), for persons who are similarly

situated to the plaintiffs and have “ a continuing live in

terest in the issues” is inapplicable. In Gerstein, the Su

preme Court found that there was no indication in the

record whether any of the named plaintiffs were still in

custody awaiting trial at the time the District Court cer

tified the class. Nevertheless, it held that the case was not

moot because the controversy was so transitory that moot

ness might inevitably intervene before the District Court

could reasonably be expected to certify the class. See also

Sosna, supra, 419 U.S. at 402 n .ll ; Boyd, supra, 546 F.2d

at 527 n.2. While under Gerstein and Sosna a belated cer

tification may be said to “ relate back” to the filing of the

complaint, such an argument is unavailable where, as here,

the District Court expressly denied class certification and

there was no apjjeal from that determination. Cruz v.

Hauch, 515 F.2d 322 (5th Cir. 1975), cited by the plain

tiffs, is distinguishable for the same reason. In Cruz, the

Court was “unable to find any certification of this pro

ceeding as a class action” but the parties had treated the

litigation “ as though the District Court made an appro

priate certification.” 515 F.2d at 325, n.l.

The plaintiffs contend that Rule 71 of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure provides a basis on which to seek to en

force the contempt judgment. We disagree. Rule 71 pro

vides, in pertinent part:

When an order is made in favor of a person who is

not a party to the action, he may enforce obedience

5090

to the order by the same process as if he were a

party; . . . .

It seems clear that Bale 71 was intended to assure that

process be made available to enforce court orders in favor

of and against persons who are properly affected by them,

even if they are not parties to the action. 7 J. Moore,

F ederal P ractice, 1J71.02 (1975). While Buie 71 may

support a separate action by a present inmate to enforce

the order obtained by the plaintiffs, it cannot be used by a

party to enforce an order in an action in which he no

longer has standing to sue. The cases cited by the plain

tiffs in this regard are clearly distinguishable since each

deals with a situation in which a non-party sought to en

force an order obtained by a party to the action by a

motion for contempt.

Finally, while it may be argued that the Court itself has

an interest in assuring that litigants comply with its or

ders, it is well established that a “civil contempt proceed

ing is wholly remedial, to serve only the purposes of the

complaint, not to deter offenses against the public or to

vindicate the authority of the court.” United States v. In

ternational Union, etc., 190 F.2d 865, 873 (D.C. Cir. 1951);

see also MacNeil v. United States, 236 F.2d 149, 153-54 (1st

Cir.), cert, denied, 352 TT.S. 912 (1956).

Since there is no individual plaintiff still in custody at

the Dutchess County jail, no class certification by the Dis

trict Court, and no basis on which the Court can vindicate

its own authority in the context of a civil contempt pro

ceeding, the Court is constrained to conclude that the case

is moot. Accordingly, the judgment of the District Court is

vacated and the case remanded to the District Court for

dismissal. Nothing in this opinion is intended to prejudice

the reinstitution of these proceedings on behalf of any

present inmate of the Dutchess County jail.

5091

480-8-2-77 USOA—4221

MEIIEN PRESS INC, 445 GREENWICH ST., NEW YORK, N. Y. 10013, (212) 966-4177

«efgs^. 219