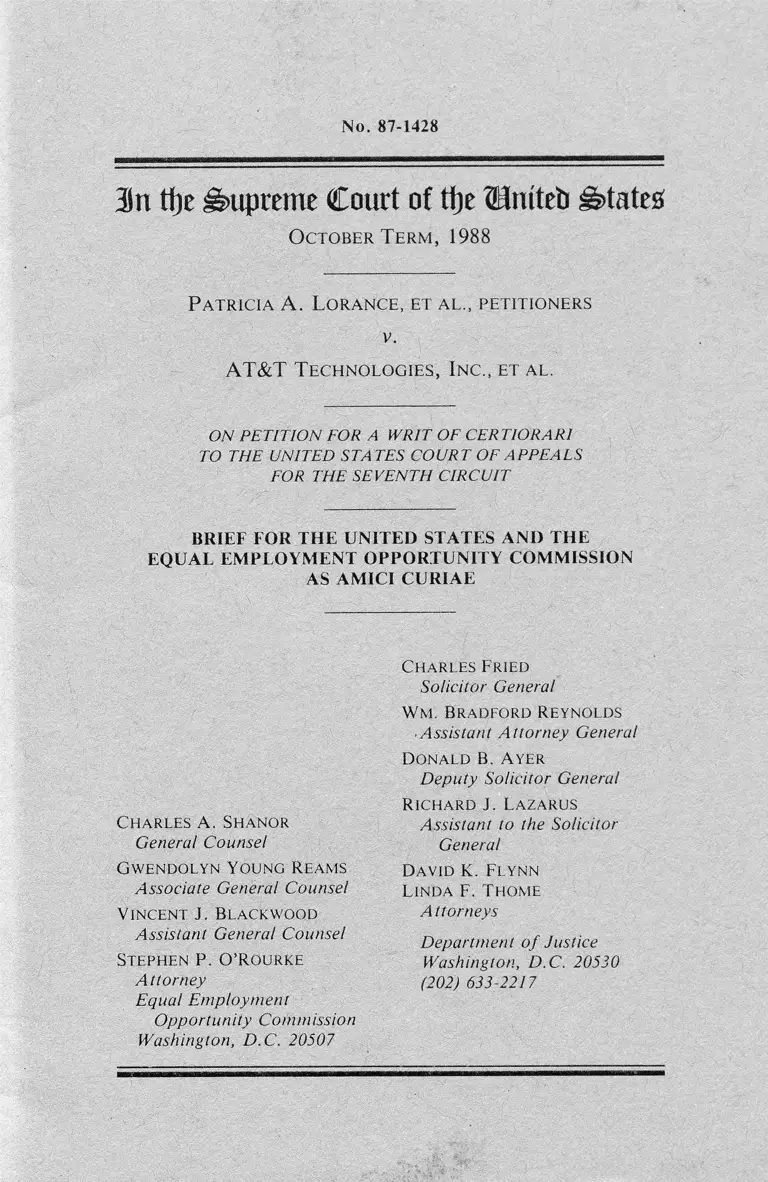

Lorance v. AT&T Technologies, Inc. Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 30, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lorance v. AT&T Technologies, Inc. Brief Amicus Curiae, 1988. eec28f9d-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8817784f-3a3f-4b8d-8d4c-67ff9a1ad1c7/lorance-v-att-technologies-inc-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

No. 87-1428

tfjc S u pre m e C o u rt of tf)e U m te b iktate#

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1988

P a t r ic ia A. L o r a n c e , e t a l ., p e t it io n e r s

AT&T T e c h n o l o g ie s , I n c ., e t a l .

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AND THE

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

AS AMICI CURIAE

V.

Charles Fried

Solicitor General

W m . Bradford Reynolds

■ Assistant Attorney General

Donald B. A yer

Deputy Solicitor General

C harles A. Shanor

General Counsel

R ichard J. Lazarus

Assistant to the Solicitor

General

G wendolyn Young Reams

Associate General Counsel

David K. F lynn

L inda F. T home

AttorneysVincent J. Blackwood

Assistant General Counsel Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 633-2217

Stephen P. O ’Rourke

Attorney

Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission

Washington, D.C. 20507

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether in the case of an employment discrimination charge

alleging that the complainant was demoted pursuant to a

facially-neutral, but intentionally discriminatory seniority

policy, the statute of limitations of Section 706(e) of Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(e), begins to run

when the employer first adopts the seniority policy, when the

employee first becomes subject to the policy, or when the

employee is first notified of the demotion.

(1)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Statement ..................................... ...................................... 1

Discussion ............................................................................ 6

Conclusion ......................... 19

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Abrams v. Baylor College of Medicine, 805 F.2d 528 (5th

Cir. 1986)................................................................... 12-13

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974) . . . 17

Association Against Discrimination in Employment, Inc.

v. City of Bridgeport, 647 F.2d 256 (2d Cir. 1981), cert.

denied, 455 U.S. 988 (1982) ......................................... 13

Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986) . . . . . . . . . . . 7 , 8, 1 1, 12

California Brewers Ass’n v. Bryant, 444 U.S. 598 (1980). . 18

Char don v. Fernandez, 454 U.S.6(1981)........................ 8

Cook v. Pan American World Airways, Inc., 771 F.2d

635 (2d Cir. 1985), cert, denied, 474 U.S. 1109 (1986).. 14,

15, 16

Crosland v. Charlotte Eye, Ear & Throat Hospital, 686

F.2d 208 (4th Cir. 1982)................... 13

Delaware State College v. Ricks, 449 U.S. 250 (1980) . . . . 6, 7,

8, 9, 10, 16

EEOC v. Commercial Office Products Co., No. 86-1696

(May 16, 1988) .......................................................... 6, 14

EEOC v. Westinghouse Electric Corp., 725 F.2d 211 (3d

Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 469 U.S. 820 (1984)................ 13

Florida v. Long, No. 86-1685 (June 23, 1988).................. 7

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747

(1976) ............................ ....................................... 7, 10, 17

Furr v. AT&T Technologies, Inc., 824 F.2d 1537 (10th

Cir. 1987)................... 12

Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433 U.S.

299 (1977) ............................................... 11

Heiar v. Crawford County, 746 F.2d 1190 (7th Cir.

1984) ............................ 8

Humphrey v. Moore, 375 U.S. 335 (1964)....................... 17

International Ass’n of Machinists v. NLRB, 362 U.S.

411 (1960) ................................................................. 11

( I I I )

IV

Cases —Continued: Page

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977) .................. ............................... 10, 11

Johnson v. General Electric, 840 F.2d 132 (1st Cir.

1988) .................................................... .............. . 12

McKenzie v. Sawyer, 684 F.2d 62 (D.C. Cir. 1982)......... 13

Morelock v. NCR Corp., 586 F.2d 1096 (6th Cir. 1978),

cert, denied, 441 U.S. 906 (1979) ................................ 14, 16

Nashville Gas Co. v. Satty, 434 U.S. 136 (1977).............. 18

Oscar Mayer & Co. v. Evans, 441 U.S. 750(1979) .......... 14-15

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 634 F.2d 744 (4th

Cir. 1980), vacated, 456 U.S. 63 (1982).................... . 9, 10,

14, 15, 17, 18

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982)............ 10, 11

Satz v. ITT Financial Corp., 619 F.2d 738 (8th Cir.

1980) ........................................................................ 13

Torres v. Wisconsin Dep’t o f Health & Social Services,

838 F.2d 944 (7th Cir. 1988) ....................................... 13

United Air Lines, Inc. v. Evans, 431 U.S. 553 (1977)....... 6, 7,

8, 10, 12

Williams v. Owens-Illinois, Inc., 665 F.2d 918 (9th Cir.),

cert, denied, 459 U.S. 971 (1982) ................................ 13

Statutes:

Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 § 4(f)(2),

29 U.S. C. 623(0(2)....... ............................................ 15

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Tit. VII, 42 U.S.C. 2000e et

seq............................................................................. 3, 9

§ 703(h), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(h) .............................. 6, 9, 10,

11, 15, 16, 17

§ 706(e), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(e) .............................. .3, 6, 7,

8, 9, 10, 17, 18

§ 706(f), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(f).............. .................. 3

National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. 160(b)............ 11

3) n tfje Supreme Court of tfje Uniteti

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1988

No. 87-1428

P a t r ic ia A. L o r a n c e , e t a t ., p e t it io n e r s

v .

AT&T T e c h n o l o g ie s , I n c ., e t a l .

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AND THE

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

AS AMICI CURIAE

This brief is submitted in response to the Court’s invitation to

the Solicitor General to express the views of the United States.

STATEMENT

1. Petitioners Patricia A. Lorance, Janice M. King, and

Carol S. Bueschen are hourly wage employees at the Mont

gomery Works plant of respondent AT&T Technologies, Inc.

(AT&T), in Aurora, Illinois.1 They are also members of re

spondent Local 1942, International Brotherhood of Electrical

Workers, AFL-CIO (Union). Pet. App. 4a. Petitioners Lorance

and Bueschen have been employed at the plant by AT&T since

1 Because the courts below awarded summary judgment to respondents

based solely on the untimeliness of the charge, our statement, like those con

tained in the lower courts’ opinions, is based on the facts alleged in petitioners’

complaint.

(1)

2

1970, and petitioner King commenced work there in 1971

(ibid.). At that time, promotions and demotions at the plant

were based on plant-wide seniority (ibid.).

Most hourly wage jobs at the plant are semi-skilled jobs and

have traditionally been filled by women (Pet. App. 15a).

Among the highest paying hourly wage jobs at the plant are

“tester” jobs (id. at 4a, 15a). Tester positions were traditionally

filled by men who were either promoted from among the

relatively few men in the lower paying wage jobs or hired direct

ly into tester positions (id. at 15a). All three petitioners were

originally employed in nontester positions.

By 1978, an increasing number of women obtained tester

positions based on their plant-wide seniority (Pet. App. 4a). In

July 1979, AT&T and the Union modified the collectively

bargained seniority system applicable to the Montgomery

Works plant to provide that promotions and demotions of

testers with less than five years of tester service, who have not

completed a training program for the tester job would be

governed by seniority as a tester rather than plant-wide seniority

(ibid.\ Compl. ̂ 17).2 3 The new seniority plan was known as the

“Tester Concept” (Pet. App. 4a). Petitioner Lorance was a

tester at the time the seniority system was changed (id. at 5a).

Petitioners Bueschen and King became testers in 1980 (ibid.).

In late 1982, AT&T began a reduction in force and, based on

its new seniority system, demoted all three petitioners (Pet.

App. 5a). Petitioners Lorance and King were demoted from

senior testers to junior testers and petitioner Bueschen was

demoted to a nontester position (ibid.)J Petitioners would not

have been demoted if AT&T had implemented the reduction in

force on the basis of each petitioner’s plant-wide seniority

(ibid.). Within 300 days of their demotions, petitioners filed ad

ministrative charges with the Equal Employment Opportunity

2 The Union approved the new plan by a vote of ninety votes to sixty, which

was approximately the ratio of men to women (Pet. App. 5a).

3 King was downgraded on August 23, 1982. Lorance and Bueschen were

downgraded on November 15, 1982, and Bueschen was downgraded a second

time on January 23, 1983. Pet. App. 17a.

3

Commission (EEOC) claiming that their demotions violated

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000e ei

seq,4 The EEOC determined that there was not reasonable cause

to believe that petitioners allegations were true and, according

ly, issued them right-to-sue letters (Pet. App, 5a).

2. Petitioners subsequently brought this lawsuit in the

United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois

pursuant to Section 706(f) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(f).5

In their complaint, petitioners allege that respondents AT&T

and Union changed the seniority system in 1979 “in order to

protect incumbent male testers and to discourage women from

promoting into the traditionally-male tester jobs” (Compl.

H 14). They also allege that application of this provision has had

the effect of favoring male testers over female testers (id. H 18;

see also id. 1 6(f)).

The district court granted respondent AT&T’s motion for

summary judgment and, sua sponte, also granted summary

judgment in favor of respondent Union (Pet. App. 12a~33a).6

The court agreed with AT&T that petitioners’ challenge was

time-barred because they had failed to file their charges with the

EEOC within the applicable limitations period established by

Section 706(e) of Title VII (42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(e)).7 The court

ruled that the limitations period started to run when each peti

tioner first became subject to the new seniority policy as a tester

(Pet. App. 26a, 32a). In doing so, it rejected petitioners’ conten

tion that the limitations period commenced when they were de

4 Petitioners Lorance and Bueschen filed charges with the EEOC on April

13, 1983, and petitioner King filed her charge on April 21, 1983 (Pet. App.

18a).

5 Petitioners brought this suit as a class action, but the district court has yet

to rule on their motion to certify the class (see Pet. App. 6a n.l).

6 The district court adopted the recommendation of the magistrate that

summary judgment should be entered in favor of respondents (Pet. App.

34a-50a).

1 AT&T argues that Title VIPs 180-day limitation period applies rather than

its 300-day limitations period, but the courts below did not address the issue

because under their analysis petitioners’ charges were untimely in either event

(see Pet. App. 6a n.2, 19a-20a n.3).

4

moted in 1982 (id. at 25a-27a), and likewise rejected AT&T’s

claim, which the magistrate had accepted (id. at 43a-44a), that

the limitations period commenced for all petitioners in 1979

when AT&T first adopted the seniority policy (id. at 27a-31a).

Because, as the court found, each petitioner filed his charge

more than 300 days after the time each first became subject to

the new policy as a tester, the court concluded that petitioners’

complaint should be dismissed because none had timely filed her

charge with the EEOC (id. at 32a-33a n.6).

3. The court of appeals affirmed (Pet. App. 3a-1 la). The

court agreed that petitioners’ argument was “logically appeal

ing,” but concluded that it was “compelled to reject it” because

“[i]f we were to hold that each application of an allegedly dis

criminatory seniority system constituted an act of discrimina

tion, employees could challenge a seniority system indefinitely”

(id. at 8a). Like the district court, however, the court of appeals

also rejected AT&T’s argument that the “adoption” of the

seniority system constituted the relevant act that triggered the

running of Title VII’s limitations period (ibid.). According to

the court, such a rule would “encourage needless litiga

tion” by employees not even yet formally subject to the seniority

plan and would also “frustrate the remedial policies that are the

foundation of Title VII” by providing future employees with no

recourse against a seniority system they thought discriminatory

(ibid.).

The court of appeals determined that to strike a “balance that

reflects both the importance of eliminating existing discrimina

tion, and the need to insure that claims are filed as promptly as

possible,” the rule should be that “the relevant discriminatory

act that triggers the period of limitations occurs at the time an

employee becomes subject to a facially-neutral but discrimina

tory seniority system that the employee knows, or reasonably

should know, is discriminatory” (Pet. App. 9a). The court con

cluded that because affidavits submitted by petitioners estab

lished that they knew they were subject to the new seniority

policy on the day they became subject to it as testers, the limita

tions period commenced on that date. Hence, the court found,

petitioners’ charges were not timely filed with the EEOC be

5

cause they were filed two to three years after each petitioner was

first subject to the new policy, which is far beyond the 300-day

limitations period provided by Title VII (ibid.). See note 4,

supra.8

Judge Cudahy dissented (Pet. App. lOa-lla). He agreed that

the majority’s policy concerns were “important,” but contended

that they “find dubious application in the result here” (id. at

11a). He explained that the majority’s rule would not achieve its

goal of preventing suits against seniority plans adopted long

ago, but instead would merely limit the plaintiffs who could

maintain a lawsuit to those more recently hired (id. at 10a).

Judge Cudahy also faulted the majority for announcing a legal

rule that would require employees to bring premature lawsuits.

When an employee is first subject to a seniority policy, the dis

sent explained, he has not yet been injured by it and does not

know whether he ever will be. Ibid.9

DISCUSSION

Like petitioners, we believe that the decision of the court of

appeals is incorrect, conflicts with decisions of other courts of

appeals, and presents an important question of federal employ

ment discrimination law. We accordingly urge the Court to

grant the petition for a writ of certiorari.

1. Section 706(e) of Title VII provides that where, as in this

case, there is a state fair employment practice agency with over

lapping jurisdiction, an employment discrimination charge must

be filed with the EEOC within 300 days “after the alleged unlaw

ful employment practice occurred” (42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(e)).10

8 The court described (Pet: App. 9a) its holding as “a narrow one,” noting

that the relevant act of discrimination may be different where, unlike this case,

the seniority policy is facially discriminatory or the employer exercises discre

tion provided by the plan in a discriminatory fashion.

9 The court of appeals denied petitioners’ petition for rehearing and sugges

tion for rehearing en banc (Pet. App. la-2a). Judges Easterbrook, Ripple, and

Cudahy voted in favor of rehearing en banc (id. at 2a n.*).

10 As previously noted (see note 7, supra), AT&T claims that the applicable

limitations period in this case is 180 (not 300) days because, although there is a

6

Hence, “[determining the timeliness of [petitioners’] EEOC

complaint, and this ensuing lawsuit, requires us to identify

precisely the ‘unlawful employment practice’ of which [they]

complain[ ].” Delaware State College v. Ricks, 449 U.S. 250,

257 (1980). “[T]he critical question is whether any present viola

tion exists.” United Air Lines, Inc. v. Evans, 431 U.S. 553, 558

(1977) (emphasis omitted).

The gravamen of petitioners’ complaint is that respondent

AT&T violated Title VII by demoting them pursuant to a

seniority policy that, while facially neutral, intentionally

discriminates against them on the basis of their sex and, hence,

falls outside the protective ambit of Section 703(h).11 Hence, if,

as respondent AT&T contends, the unlawful practice

“occurred” when AT&T first adopted the seniority policy or, as

the court of appeals held, when it was made known to each peti

tioner that her seniority rights would be determined under the

new policy, then petitioners’ charges would clearly be time-

barred because petitioners did not file their charges within 300

days of either of those events. If, on the other hand, the

unlawful practice occurred on the date of petitioners’ demotion,

their filings with the EEOC would be timely.

state fair employment practice agency with overlapping jurisdiction,

respondents “failed to file timely charges with the applicable state ‘deferral’

agency” (Appellee AT&T C.A. Br. 12 n.10). The lower courts did not address

this question because the resolution of that issue would not have affected their

disposition of the case (see Pet. App. 6a n.2, 19a-20a n.3). We note, however,

that to the extent that respondent AT&T’s assertion rests on an allegation that

state proceedings were not timely instituted under state law, it cannot survive

this Court’s recent decision in EEOC v. Commercial Office Products Co., No.

86-1696 (May 16, 1988), slip op. 14 (“state time limits for filing discrimination

claims do not determine the applicable federal time limit”). In any event, the

question whether the 180 or 300-day limitations period applies does not

preclude review of the question presented by the petition because petitioners

Lorance and Bueschen filed their charges with the EEOC within 180 days after

their demotions (see notes 3, 4, supra).

11 See 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(h) (“[I]t shall not be an unlawful employment

practice for an employer to apply * * * different terms, conditions, or

privileges of employment pursuant to a bona fide seniority or merit system

* * * provided that such differences are not the result of an intention to

discriminate * * *.”).

7

We agree with petitioners that their charges were timely filed

because the date of their demotions was the date on which the

“alleged unlawful employment practice occurred,” within the

meaning of Section 706(e). Each application of a discriminatory

seniority system to alter an employee’s employment status, like

each application of a discriminatory salary structure to deter

mine an employee’s weekly paycheck, “is a wrong actionable

under Title VII.” Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385, 396 (1986)

(discriminatory salary structure).12 In our view it is no bar to the

bringing of a challenge confined to the current application of an

allegedly discriminatory seniority policy that its previous ap

plications of the same policy are not now subject to legal

challenge under Title VII, either because the limitations period

has expired or because Title VII was not then in effect. Cf. id. at

395.

Contrary to the court of appeals’ decision, neither this

Court’s decision in United Air Lines, Inc. v. Evans, 431 U.S.

553 (1977), nor its ruling in Delaware State College v. Ricks, 449

U.S. 250 (1980), compels a different result.13 In both of those

cases, the Court held that employment practices that merely

perpetuate the consequences of prior discrimination are not

themselves actionable wrongs under Title VII and, hence, the

applicable limitations period begins to run on the date of the

prior discriminatory act. Thus, in Evans, the limitations period

began to run at the time the employee was allegedly discharged

in violation of Title VII and was not restarted when the

employer subsequently refused the employee’s request to restore

12 Indeed, seniority systems and salary may merge because under some

employment contracts “earnings are * * * to some extent a function of seniori

ty.” Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 767 (1976).

13 This Court’s more recent decision in Florida v. Long, No. 86-1685 (June

23, 1988), also does not support the court of appeals’ decision in this case.

Current seniority rights, like current salary payments, relate to “work present

ly performed” (slip op. 15). They are not akin to the pension plan at issue in

Florida v. Long, which, “funded on an actuarial basis, provides benefits fixed

under a contract between the employer and retiree based on a past assessment

of an employee’s expected years of service, date of retirement, average final

salary, and years of projected benefits” (slip op. 15).

8

seniority rights she would have accrued had she remained em

ployed instead of being discriminatorily discharged (431 U.S. at

557-558). Likewise, in Ricks the limitations period began to run

at the time the employer notified the employee of his denial of

tenure and not when, as the “inevitable consequence” of that

denial, the employee was later discharged upon completion of a

one-year terminal contract (449 U.S. at 256-259).

In this case, however, petitioners’ demotions were not merely

present consequences of a previous, time-barred discriminatory

decision or act. They were instead a direct, present application

of AT&T’s intentionally discriminatory seniority system, and

thus were themselves “unlawful employment practices” capable

of triggering the Section 706(e) limitations period. Evans differs

from this case in that the plaintiff there did not allege that her

employer’s seniority system was itself discriminatory, but in

stead urged as the source of the wrong the earlier discriminatory

discharge (431 U.S. at 560; see Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. at

396 n.6). And, while in Ricks the employer was, in a manner of

speaking, applying its prior tenure decision in subsequently

discharging the employer, the latter action was, unlike the

demotion in this case, the “inevitable[ ] consequence” of the

prior decision (449 U.S. at 257-258). Hence, the announcement

of the tenure denial in Ricks also amounted to formal prior

notification of termination of his employment and, for that

reason, triggered the running of Title VII’s limitations period.

Cf. Chardon v. Fernandez, 454 U.S. 6, 8 (1981) (footnote

omitted) (limitations period begins to run in a Section 1983 ac

tion based on unlawful employment discrimination at the time

“the operative decision was made —and notice given —in ad

vance of a designated date on which employment termi

nated”).14 By contrast, AT&T’s announcement of its new

14 We assume that petitioners did not receive formal prior notification of

their imminent demotion prior to the demotion itself. If they did, the limita

tions period might be deemed to have commenced at that earlier time. See

Heiar v. Crawford County, 746 F.2d 1190, 1194 (7th Cir. 1984) (While

“specific notice of termination * * * starts the * * * statute of limitations run

ning, it does not follow that the notice an employee receives when he is first

hired would also set the statute to run; it surely would not.”).

9

seniority policy in this case did “not abundantly forewarn[ ]”

petitioners (449 U.S. at 262 n.16). It did not notify petitioners

that they would in fact be demoted based on that policy at some

future date certain. It merely created the theoretical possibility

of some undefined future adverse consequences.

Nor is there any merit in either the court of appeals’ (Pet.

App. 8a) or respondent AT&T’s suggestion (Br. in Opp, 5-7)

that Section 706(e) should be applied more strictly where the

challenge is to the lawfulness of a seniority system because

seniority systems are accorded special status in Title VII. Sec

tion 706(e) nowhere provides that challenges to seniority sys

tems are governed by a different limitations period than other

types of discrimination claims. Moreover, Section 703(h), which

is the only provision in Title VII that identifies seniority systems

for special treatment, does not speak, explicitly or implicitly, to

limitations issues (see 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(h)). It simply provides

that differences in treatment that would otherwise be unlawful

under Title VII are lawful where they are “pursuant to a bona

fide seniority * * * system * * * provided that such differences

are not the result of an intention to discriminate” (ibid.).15

Unlike AT&T, we do not believe that the legal effect of Sec

tion 703(h) is to require that any challenge to a seniority plan

under Title VII must be brought, at most, within 300 days of the

plan’s adoption.16 Section 703(h) requires that the employee in-

15 The court of appeals, unlike AT&T, never relied on Section 703(h) to

support its ruling.

16 Indeed, as the court of appeals recognized (Pet. App. 8a), such a view

leads to nonsensical results. An individual injured by a seniority system

adopted long before he became employed by the company would have no

standing to complain until after his claim was time-barred. Seniority systems,

however discriminatory in purpose and effect, would operate with impunity,

immune from legal challenge, just 300 days after being put into effect, as

would all of those enacted before the adoption of Title VII. This Court’s deci

sions, however, reflect a quite different view of the import of Section 703(h).

See, e.g., American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, 456 U.S. 63, 69-70 (1982)

(“The adoption of a seniority system which has not been applied would not

give rise to a cause of action. A discriminatory effect would arise only when

the system is put into operation and the employer ‘applies’ the system. Such

application is not infirm under § 703(h) unless it is accompanied by a dis

10

elude in his proof of unlawful discrimination a showing “of ac

tual intent to discriminate on * * * the part of those who

negotiated or maintained the system.” Pullman-Standard v.

Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 289 (1982); American Tobacco Co. v. Pat

terson, 456 U.S. 63, 65, 69-70 (1982).17 It does not suggest that

only the adoption of the seniority system, as distinguished from

its specific applications to define employee rights, can be an

“alleged unlawful employment practice” that triggers the run

ning of Section 706(e)’s limitations period. Indeed, Section 703(h)

does not define what is unlawful under Title VII in the first in

stance at all. It simply provides that “[notwithstanding any

other provision of [Title VII],” certain employment practices

criminatory purpose.”); United Air Lines, Inc. v. Evans, 431 U.S. at 560 (Sec

tion 703(h) “does not foreclose attacks on the current operation of seniority

systems which are subject to challenge as discriminatory.”); Franks v.

Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 761 (1976) (“[T]he thrust of [Sec

tion 703(h)] is directed toward defining what is and what is not an illegal

discriminatory practice in instances in which the post-Act operation of a

seniority system is challenged as perpetuating the effects of discrimination oc

curring prior to the effective date of the Act.”). Nor can we suppose that Con

gress intended such a harsh result, particularly in Title VII where this Court

has recognized “that the limitations periods should not commence to run so

soon that it becomes difficult for a layman to invoke the protection of the civil

rights statutes” (Delaware State College v. Ricks, 449 U.S. at 262 n.16) and

“the difficulty of fixing an adoption date” (American Tobacco Co. v. Patter

son, 456 U.S. at 76 n.16).

17 AT&T’s erroneous contention (Br. in Opp. 7) that the court of appeals’

decision in this case is “compelled” by this Court’s decision in American

Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, supra, rests on a mischaracterization of the Court’s

opinion in that case. The Court in American Tobacco Co. found that, “taken

together, Teamsters and Evans stand for the proposition stated in Teamsters

that ‘[sjection 703(h) on its face immunizes all bona fide seniority systems, and

does not distinguish between the perpetuation of pre- and post-Act’ discrimi

natory impact” (456 U.S. at 75-76 (emphasis and brackets in original), quoting

International Brotherhood o f Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 348

n.30 (1977) (emphasis added)). AT&T omits the Court’s critical qualification

that the seniority system must be “bona fide.” The Court’s statement does not

“compel” a particular result in this case because petitioners assert that AT&T’s

seniority system was adopted with a discriminatory intent and, hence, is not

“bona fide” within the meaning of Section 703(h).

11

shall not be unlawful.18 In this case, therefore, Section 703(h)

does not shift the focus of petitioners’ discrimination claim

away from its assertion that AT&T’s current operation of the

plan (in demoting petitioners pursuant to that plan) constitutes

a present violation of Title VIL19

Finally, there is likewise no merit in respondent AT&T’s im

plicit suggestion that its seniority policy should be

separated into two distinct parts in considering the timeliness of

18 Indeed, Section 703(h) does not even require an employee to show that a

seniority system was adopted with discriminatory intent. It is well settled that a

seniority system loses its exemption under Section 703(h) if it is either adopted

or maintained for discriminatory reasons. International Brotherhood o f

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. at 355-356; Pullman-Standard v. Swint,

456 U.S. at 289.

19 While proof of AT&T’s discriminatory intent at the time its seniority plan

was adopted or maintained is necessary in order to overcome the Section

703(h) defense, it is not alone sufficient to establish petitioners’ claim that the

seniority plan amounts to a present violation of Title VII. Cf. Bazemore\. Fri

day, 478 U.S. at 396-397 n.6, 402; Hazelwood School District v. United States,

433 U.S. 299, 309-310 & n.15 (1977). For this reason, AT&T’s reliance (Br. in

Opp. 7) on International Ass’n o f Machinists v. NLRB, 362 U.S. 411 (1960) is

misplaced. In International Machinists, the Court held that a claim of unfair

labor practice based on the enforcement of a clause in a collective bargaining

agreement was untimely under the National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C.

160(b), because the exclusive ground for the clause’s asserted illegality was an

error in its execution and challenges to the execution itself were no longer time

ly. The Court explained that “the use of the earlier unfair labor practice * * *

serves to cloak with illegality that which was otherwise lawful. And where a

complaint based upon that earlier event is time-barred, to permit the event

itself to be so used in effect results in reviving a legally defunct unfair labor

practice” (362 U.S. at 417). In this case, however, petitioners have not sought

“to cloak with illegality that which was otherwise lawful.” Petitioners instead

were simply overcoming a possible defense to their claim based on Section

703(h), and —as we understand them —contend only that “earlier events may

be utilized to shed light on the true character of matters occurring within the

limitations period” (362 U.S. at 416). Hence, in this case, unlike International

Machinists, the contractual provision being challenged is not “wholly benign”

and the evidence of AT&T’s motive in adopting and maintaining the seniority

plan is simply evidence deemed necessary by Congress to prove “the true

character” of the plan’s current operation (id. at 416-417 (footnote omitted)).

12

a Title VII claim: (1) a rule that the seniority of testers will be

decided by service as a tester, not plant-wide service; and (2) a

rule that employees will be entitled to certain benefits and the

avoidance of certain burdens according to their seniority.

AT&T argues, in effect, that petitioners cannot rely on the date

of their demotions to support the timeliness of their charges

because the only seniority rule applied by AT&T in demoting

petitioners was the second rule, while petitioners’ discrimination

challenge is confined to the lawfulness of the first seniority rule,

which was adopted and applied to petitioners at much earlier

dates. There is no more merit to this argument, however, than

there would have been to an analogous contention in Bazemore

that each weekly paycheck is not an actionable wrong under Ti

tle VII because it is simply the product of the application of a se

cond, wholly benign, discrete rule —that individuals would be

paid salaries pursuant to the salary structure —while the em

ployees’ discrimination charge focussed on the salary structure

itself, which had been adopted at an earlier time. In neither in

stance is the so-called second aspect of the employer’s policy

truly separable from the admittedly discriminatory portion of

the policy, because in each case the second necessarily incor

porates and applies the substance of the first.20

2. We also agree with petitioners that there is a conflict in

the circuits. As the First Circuit recently explained in the course

of sharply criticizing the Seventh Circuit’s decision in this case,

“[m]ost circuit courts have * * * rejected [its] analysis. They

have reasoned, instead, that the application of a discriminatory

system to a particular substantive decision (e.g., to promote,

demote, fire, or award benefits) constitutes an independent dis

criminatory act which can trigger the commencement of the

statute of limitations.” Johnson v. General Electric, 840 F.2d

132, 135 (1st Cir. 1988).21

20 In contrast, the seniority policy at issue in Evans was wholly benign and

distinct from the employer’s prior discriminatory discharge of the employee.

21 See, e.g., Furr v. AT&T Technologies, Inc., 824 F.2d 1537, 1543 (10th

Cir. 1987) (systematic company policy restricting promotions; Age

Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA)); Abrams v. Baylor College of

13

There is a conflict in the circuits warranting this Court’s

review, moreover, even if the Seventh Circuit’s analysis can, as

AT&T suggests (Br. in Opp, 1), somehow be confined “to

unique issues presented by seniority systems.” 22 As petitioners

explain (Pet. 16-20), the Second, Fourth, and Sixth Circuits

have, unlike the Seventh Circuit, each treated the application of

facially neutral but discriminatory seniority plans as providing

the basis for continuing violations of federal employment dis

Medicine, 805 F.2d 528, 532-533 (5th Cir. 1986) (policy restricting

assignments; Title VII); EEO C\. Westinghouse Electric Corp., 725 F.2d 211,

219 (3d Cir. 1983) (policy restricting layoff benefits; ADEA), cert, denied, 469

U.S. 820 (1984) ; Crosland v. Charlotte Eye, Ear & Throat Hospital, 686 F.2d

208, 211-212 (4th Cir. 1982) (policy restricting pension plan benefits; Title

VII); McKenzie v. Sawyer, 684 F.2d 62, 72 (D.C. Cir. 1982) (policy restricting

promotions; Title VII); Williams v. Owens-Illinois, Inc., 665 F.2d 918,

924-925 (9th Cir.) (systematic discrimination with respect to assignments and

promotions; Title VII), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 971 (1982); Association Against

Discrimination in Employment, Inc. v. City o f Bridgeport, 647 F.2d 256, 274

(2d Cir. 1981) (giving and using discriminatory hiring examination; Title VII),

cert , denied, 455 U.S. 988 (1982) ; Satz v. IT T Financial Corp., 619 F.2d 738,

743-744 (8th Cir. 1980) (discriminatory pay and denial of promotions as

evidenced by discrete acts over a period of time; Title VII).

22 A subsequent Seventh Circuit opinion authored by Judge Cudahy, who

dissented in that court’s decision below (see Pet. App. lOa-lla), also suggests

that possibility. In Torres v. Wisconsin Dep’t o f Health & Social Services, 838

F.2d 944, 948 n.3 (1988), a Seventh Circuit panel rejected an employer’s claim

that the plaintiffs’ complaints were not timely filed with the EEOC, where

plaintiff-employees were challenging a facially discriminatory employer plan

adopted in 1980 that restricted certain jobs to women, but did not file charges

“until after their demotions, pursuant to the full implementation of the Plan,

in September 1982.” The court ruled “that the relevant discriminatory act was

the Plan’s implementation and the plaintiffs’ resulting demotions in 1982. The

plaintiffs’ status * * * was not directly affected by the mere adoption of the

Plan in 1980, nor were their future demotions assured at that time” (ibid.). The

court preceded a cite to its prior decision in this case with a “But, cf.” signal

and intimated that its holding there was confined to a “ ‘narrow’ set of cases

involving ‘facially-neutral but discriminatory seniority systemjs]’ ” (ibid.,

quoting 827 F.2d at 167 (Pet. App. 9a)). The Seventh Circuit has since vacated

its opinion in Torres and agreed to hear the case en banc. See 838 F.2d at

957-958. There is no indication, however, that the full court agreed to rehear

the case in order to address the timeliness issue.

14

crimination law. See Cook v. Pan American World Airways,

Inc., 771 F.2d 635, 646 (2d Cir. 1985) (“[T]he alleged discrimi

natory violations in the present case must be classified as con

tinuous ones, giving rise to claims accruing in favor of each

plaintiff on each occasion when the merged seniority list was ap

plied to him.”), cert, denied, 474 U.S. 1109 (1986) ; Patterson v.

American Tobacco Co., 634 F.2d 744, 751 (4th Cir. 1980)

(“[C]ontinuing” violations of Title VII caused by the application

of an employer’s discriminatory seniority system were “not

barred by failure to have challenged at its inception the policy

which gave continuing rise to them.”), vacated on other

grounds, 456 U.S. 63 (1982); Morelock v. NCR Corp., 586 F.2d

1096, 1103 (6th Cir. 1978) (“[T]he adoption of a seniority system

* * * constitutes a continuing violation * * * as long as that

system is maintained by the employer. An employee’s cause of

action for an alleged act of * * * discrimination caused by a

discriminatory seniority system, does not accrue until his

employment opportunities are adversely affected by the applica

tion to him of the provisions of that seniority system.”), cert,

denied, 441 U.S. 906 (1979).23

Contrary to respondent AT&T’s submission (Br. in Opp.

8-9), the force of this circuit conflict is not dissipated by any

meaningful distinction that can be made between the rulings of

the Second, Fourth, and Sixth Circuits and the Seventh Circuit’s

decision in this case. To be sure, both Cook and Morelock in

volved allegations of age discrimination under the Age

Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) and not, as in this

case, gender discrimination under Title VII, but as this Court

has repeatedly noted, “the filing provisions of the ADEA and

Title VII [are] ‘virtually in haec verba,’ the former having been

patterned after the latter.” EEOC v. Commercial Office Pro

ducts Co., slip op. 15 (quoting Oscar Mayer & Co. v. Evans, 441

23 The Seventh Circuit in this case implicitly acknowledged that its ruling

conflicted with the Fourth Circuit’s decision in American Tobacco Co., which

it cited as supporting petitioners’ contention “that the continued application of

any intentionally discriminatory seniority system constitutes a continuing

violation of Title VII” (Pet. App. 7a).

15

U.S. 750, 75 5 (1979)).24 Hence, the circuit courts’ conflicting

construction of these provisions in Title VII and the ADEA pre

sent a circuit conflict warranting further review.

Nor is there any persuasive reason to expect that any of these

other circuits might reconsider their prior rulings in light of in

tervening developments. Contrary to AT&T’s suggestion (Br. in

Opp. 8), the Fourth Circuit’s ruling in American Tobacco that

the application of a discriminatory seniority system constituted

a “continuing” violation of Title VII was not in any manner

“premised” or otherwise dependent on its other ruling in that

case that “Congress intended the immunity accorded seniority

systems by § 703(h) to run only to those systems in existence at

the time of Title VII’s effective date, and of course to routine

post-Act applications of such systems” (634 F.2d at 749). In

deed, the two rulings were made with respect to two different

seniority systems —a pre-Act seniority system and a post-Act

system of lines of progression. The Fourth Circuit first conclud

ed that Section 703(h) did apply to the pre-Act seniority system,

and remanded to the district court for further fact-finding (see

634 F.2d at 747, 750). The court of appeals then concluded that

the employees’ challenge to that system was not time-barred

because the system constituted a “continuing violation” (id. at

751). It is that holding that conflicts with the Seventh Circuit’s

ruling here. The Fourth Circuit’s conclusion that Section 703(h)

did not apply to seniority systems adopted after the effective

date of the Act applied only to the post-Act lines of progression

also at issue in the case (see 634 F.2d at 748-750); American

Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, 456 U.S. 63, 67-68 & n.2 (1982). This

Court reversed only the latter holding (see id. at 68-77). Hence,

this Court’s subsequent reversal of the Fourth Circuit’s con

struction of Section 703(h) (see 456 U.S. at 68-77) provides no

basis for speculating that the Fourth Circuit might now recon

24 The Second Circuit in Cook stressed (771 F.2d at 644) the common

features shared by Section 703(h) of Title Vli and the ADEA’s analogous pro

vision governing seniority systems (§ 4(f)(2)). See 29 U.S.C. 623(f)(2) (“it shall

not be [an] unlawful [practice] to observe the terms of a bona fide seniority

system * * * which is not a subterfuge to evade the purposes of th[e]

[ADEA].”).

16

sider its ruling on the timeliness issue. As discussed above,

moreover, we find unpersuasive AT&T’s argument that the

meaning of Section 703(h) bears on the timeliness issue and ex

pect that the Fourth Circuit would be equally unreceptive to

that contention.

We also find unconvincing AT&T’s contention (Br. in Opp.

9) that the Sixth Circuit might reconsider its decision in

Morelock in light of this Court’s subsequent decision in Ricks.

As described above, Ricks, is distinguishable from the present

case because while the denial of tenure provided the employee in

Ricks with formal notification of the “inevitable” termination of

his employment, neither the adoption of the seniority plan nor

petitioners’ becoming subject to it provided them with formal

notification of their subsequent demotion. There is, for that

reason, no grounds for supposing that Ricks would (or should)

persuade the Sixth Circuit to reconsider its ruling in Morelock.25

We do not share respondent AT&T’s view that the in

consistent statements in both Cook and Morelock should be

given no significance by this Court on the ground that they are

mere “dictum” (Br. in Opp. 9). Both courts squarely addressed

the same basic legal issue presented in this case and expressly

described their conclusions of law as holdings (see 771 F.2d at

646; 586 F.2d at 1103). That the Seventh Circuit’s rationale in

this case would have led the Second Circuit in Cook to the same

result it actually reached does not alter the fact that it rested its

judgment on starkly conflicting reasoning. Nor does the fact

that the Sixth Circuit in Morelock ultimately upheld the em

ployer’s claim that his seniority policy was lawful convert that

court’s flat rejection of the employer’s threshold timeliness

defense into mere dictum. As the employer argued in that case,

had the court accepted that threshold procedural defense, it

would have “eliminatejdj the necessity for th[e] Court to reach

the merits of th[e] appeal” (586 F,2d at 1102).

3. Finally, review is warranted because the question pre

sented by the petition is important. Congress “ordained that its

25 Morelock, like this case and unlike Ricks, involved a challenge to the ap

plication of an allegedly discriminatory seniority system.

17

policy of outlawing * * * * discrimination should have the

‘highest priority’ ” (Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424

U.S. at 763 (citations omitted), quoting Alexander v. Gardner-

Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 47 (1974)) and, as this Court has

repeatedly recognized, “[seniority rights are of ‘overriding im

portance’ in collective bargaining” (American Tobacco Co. v.

Patterson, 456 U.S. at 76 (quoting Humphrey v. Moore, 375

U.S. 335, 346 (1964)); see Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co., 424 U.S. at 766 (citation omitted) (“Seniority systems and

the entitlements conferred by credits earned thereunder are of

vast and increasing importance in the economic employment

system of this Nation.”)). This case concerns the intersection of

these two important rights of an employee and the relationship

of Sections 703(h) and 706(e) of Title VII.

The decision of the court of appeals warrants review because

it threatens these important employee rights and the employ^

ment relationship. As described by Judge Cudahy in dissent in

this case (Pet. App. 10a), employees would under this rule be re

quired to bring suit at a time when “they had not really been in

jured and might never be injured.” The likely upshot of the

Seventh Circuit’s rule will therefore be, on the one hand, the

proliferation within that jurisdiction of unnecessary and

premature lawsuits against employers to the detriment of the

employer/employee relationship and, on the other hand, the

dismissal of any suit by an employee who, like each of the peti

tioners in this case, awaits the development of a concrete injury

prior to taking the drastic action of suing his employer.26

We cannot estimate what proportion of the millions of

employees who are subject to seniority systems will be affected

by the court of appeals’ ruling either within the jurisdiction of

the Seventh Circuit, or in other circuits, should any of them

adopt a similar construction of Title VII. The EEOC has con

26 As Judge Cudahy also explained (Pet. App. 10a), the majority’s rule will

not even ably serve the one objective it sought to promote— prompt resolution

of challenges to seniority systems —because under the majority’s rule (unlike

AT&T’s), future employees are “not barred by the statute of limitations and

* * * can bring challenges to tester seniority in the future.”

18

sidered the date of the application of the allegedly

discriminatory seniority system as the most logical date for the

running of Section 706(e)’s limitations period, and has not

heretofore compiled data regarding either the date on which a

discriminatory seniority plan was first adopted or the date on

which the complaining employee first became subject to the

plan now being challenged.27

Although we have not undertaken an empirical study, we ex

pect that the relatively low number of decisions raising this

question in the seniority context under either Title VII or the

ADEA can be similarly explained. Unlike AT&T and the

Seventh Circuit in this case, employers have most likely assumed

that where, as in this case, the employee was claiming that the

seniority system was itself discriminatory, the limitations period

logically began to run on the date that they allegedly injured the

employee through the application of their seniority systems.28

Until the court of appeals’ ruling in this case, every court to

reach the issue had adopted that very view. The defense will un

doubtedly now be increasingly raised in the aftermath of the

Seventh Circuit’s ruling, but because of the existing circuit con

flict there is no need to await further development of the issue in

the lower courts.

27 For the reasons described by this Court in American Tobacco Co. v. Pat

terson, fixing an adoption date is often a difficult task (456 U.S. at 76 n.16).

28 For instance, as described by petitioners (Pet. 31-32 & n.18), in at least

two cases previously before this Court, it seems that neither employer ques

tioned the timeliness of Title VII charges challenging the lawfulness of seniori

ty plans where the plaintiff-employee had first become subject to the plan long

before the bringing of the lawsuit, which instead was filed following injury

caused by the plan’s operation. See California Brewers Ass’n v. Bryant, 444

U.S. 598, 601-602, 610-611 (1980); Nashville Gas Co. v. Satty, 434 U.S. 136,

138-143 (1977).

19

CONCLUSION

The petition for a writ of certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted.

C harles F ried

Solicitor General

W m . Bradford Reynolds

Assistant Attorney General

Donald B. A yer

Deputy Solicitor General

R ichard J. Lazarus

Assistant to the Solicitor

General

David K. Flynn

L inda F. T home

Attorneys

C harles A. Shanor

General Counsel

G w endolyn Young Reams

Associate General Counsel

Vincent J. Blackwood

Assistant General Counsel

Steph en P. O ’Rourke

Attorney

Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission

Septem ber 1988

U S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1988— 202-037/60637