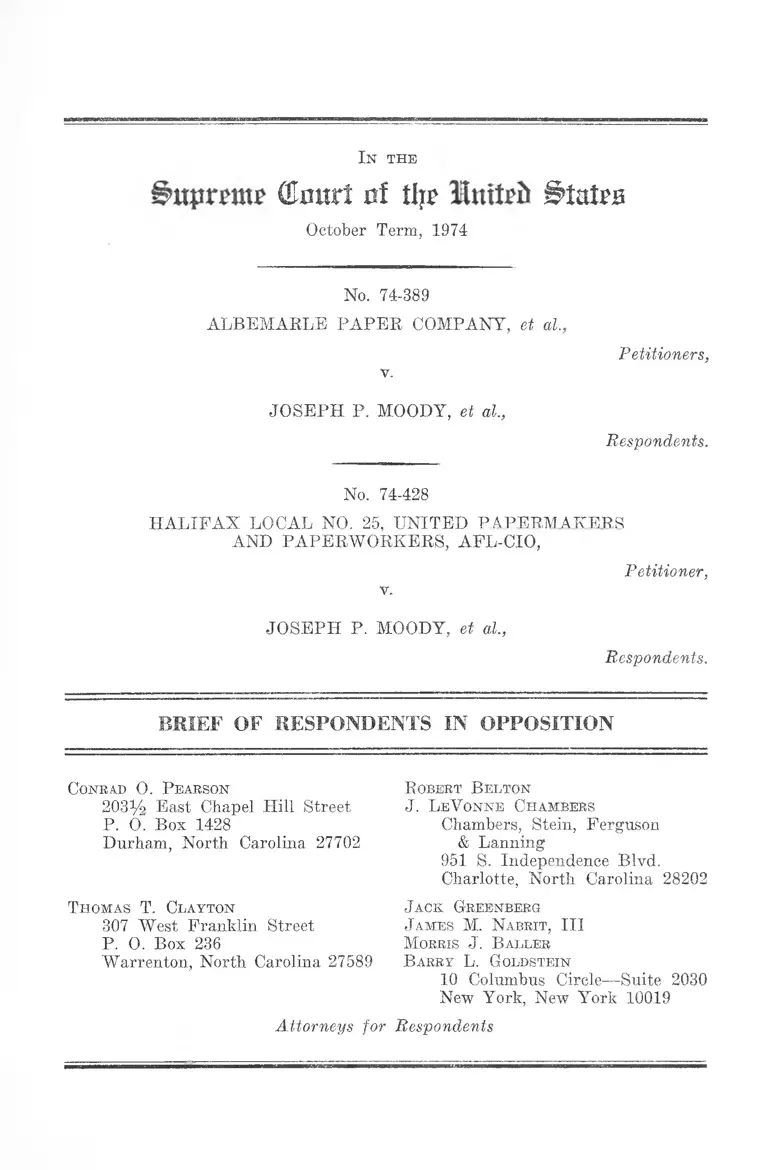

Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody Brief of Respondents in Opposition

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody Brief of Respondents in Opposition, 1974. bdb26167-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8895b7d5-3e69-4caa-b389-ec454ad3f3cc/albemarle-paper-company-v-moody-brief-of-respondents-in-opposition. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

(Enurt 0! tip States

October Term, 1974

No. 74-389

ALBEMARLE PAPER COMPANY, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

JOSEPH P. MOODY, et al,,

Respondents.

No. 74-428

HALIFAX LOCAL NO. 25, UNITED PA PERM AKERS

AND PAPERWORKERS, AFL-CIO,

v.

Petitioner,

JOSEPH P. MOODY, et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

Conrad O. P earson

203Yo East Chapel Hill Street

P. 0. Box 1428

Durham, North Carolina 27702

Thomas T. Clayton

307 West Franklin Street

P. 0. Box 236

Warrenton, North Carolina 27589

Robert Belton

J. LeVonne Chambers

Chambers, Stein, Ferguson

& Lanning

951 S. Independence Blvd.

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

J ack. Greenberg

J ames M. Nabkit, III

Morris J . Baller

Barry L. Goldstein

10 Columbus Circle—Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondents

I N D E X

PAGE

Questions Presented ........ ......................................... . 2

Statement of the Case ............................ ...................... 3

1. Seniority and Promotional Practices .............. 3

2. Testing and the Validation Study _______ 4

A r g u m e n t—

I. This Court Should Not Review the Back Pay

Award ....... ..................................................... 5

A. There Is No Significant Conflict Among the

Circuits as to the Propriety of Class Back

Pay in Title VII Cases ................................ 5

B. The Court of Appeals Opinion States an

Appropriate Standard for the Exercise of

Discretion to Award Back P a y .................. 7

C. The Court of Appeals Properly Rejected the

Trial Court’s Findings of Special Circum

stances ................................... 10

D. Class Back Pay Is Compatible With Rule 23

and the Congressional Purpose Expressed in

Title VII ........................................ 13

II. This Court Should Not Review the Testing

Decision......................................... 15

A. The Court of Appeals Correctly Considered

the EEOC Guidelines in Evaluating and Re

jecting Albemarle’s Valuation Study ............ 15

B. The Court of Appeals Properly Ordered

That Albemarle Be Enjoined From Using

Unvalidated Discriminatory Tests .............. 16

C o n clu sio n 18

11

T able op A u t h o r it ie s

Cases: page

Baxter v. Savannah. Sugar Refining Corp., 495 F.2d

437 (5th Cir. 1974) ......... ........................................ 6,11

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 489 F.2d 496 (7th Cir.

1973) ......................................................... ................. 6

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7th Cir.

1969) .................................... 9,14

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Bridgeport Civil Ser

vice Commission, 482 F.2d 1333 (1973) ................. 16

Carey v. Greyhound Bus Co., Inc., 500' F.2d 1372 (5th

Cir. 1974) ....... 11

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315, adopted in relevant

part, 452 F.2d 327 (8th Cir. 1971) (en banc), cert,

denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972) .................................... 16

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398

(5th Cir. 1974) .......... ......... ............................... ........ 6, 9

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ...... 4,15,

16,17

Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870 (6th

Cir. 1973) ......... 6,9,11

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321 (1944) .............. 8

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364

(5th Cir. 1974) ......... .... ..................................6, 7, 9,11,13

Kober v. Westinghouse Electric Corp., 480 F.2d 240

(3rd Cir. 1973) .......................................................... 6, 7

Langnes v. Green, 282 U.S. 531 (1931) ....................... 8

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971) .... 9

Ill

PAGE

LeBlanc v. Southern Tel. & Tel. Co., 333 F. Supp. 602

(E.D. La. 1971), aff’dper curiam 460 F.2d 1228 (5th

Cir. 1972), cert, denied 409 U.S. 990 (1972) .............. 6, 7

Manning v. International Union, 466 F.2d 812 (6th Cir.

1972), cert, denied 410 U.S. 946 (1973) ................... 6,7

Miller v. International Paper Co,, 408 F.2d 283 (5th

Cir. 1969) ...... ............................................................. 14

Mitchell v. DeMario Jewelry, Inc., 361 U.S. 288 (1960) 9

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 41 L.Ed. 2d 358 (1974) 8

Oatis v. Crown-Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496 (5th Cir.

1968) .............. ........................................................ !3,14

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1974)..............................................6, 9,11,14,16

Roberts v. Hermitage Cotton Mills, Inc., 498 F.2d 1397

(4th Cir. 1974), a fg 8 EPD Tf9589 (D.S.C. 1973) .... 9

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.

1971) , cert, dismissed 404 U.S. 1006 (1972) ....6,11,12,13

Rosen v. Public Service Gas & Electric Co., 409 F.2d

775 (3rd Cir. 1973) ..................................................... 12

Rosenield v. Southern Pacific Co., 444 F.2d 1212 (9th

Cir. 1971) ..... .............. .................... ........................... 6

Sanchez v. Standard Brands, Inc., 431 F.2d 455 (5th

Cir. 1971) ...... ................... ............................... ......... 14

Schaeffer v. Yellow Cabs, Inc., 462 F.2d 1002 (9th Cir.

1972) ........................................................................... 6, 7

Schultz v. Parke, 413 F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1964) .......... 9

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th

Cir. 1974) ................................................... .............. ..9,16

IV

PAGE

United States v. Hayes International Corp., 456 F.2d

112 (5th Cir. 1972) .......... .......... ................................ 12

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d

418 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 406 U.S. 906 (1972) 16

United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354

(1973) ............................... ........... ............. ................. 11

United States v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railway, 464

F.2d 301 (1972), cert, denied 409 U.S. 1116 (1973) .... 11

Vulcan Society v. Civil Service Commission, 490 F.2d

387 (2nd Cir. 1974) .................................. .................. 16

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester Co., ----- F.2d ----- , 8 EPD If 9658 (7th

Cir. 1974) ......... ............... ......... .... ...................... ...... l l

Wirtz v. B. B. Saxon Co., 365 F.2d 457 (5th Cir. 1966) 9

Statutes, Rules and Regulations:

EEOC Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures,

29 C.F.R. §§ 1607.1 et seq. .................... .............. ...... 5

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 23 ................. 2,13

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e

el se9.......................................—- ............. ..............passim

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-6(g) ..................9,10

Other Authorities:

Advisory Committee’s Notes, 39 F.R.D. 69 (1966) ....... 13

Conference Committee of Senate and House, Section-

by-Section Analysis of H.R. 1746, reprinted by Sub

committee on Labor of the Senate Subcommittee on

Labor and Public Welfare, Legislative History of

the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972

(1972) .......................... .............................. ................ 10

I n t h e

OInurt at % InttTft

October Term, 1974

No. 74-389

A lbem a rle P a per C o m pa n y , et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

J o se ph P . M oody, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 74-428

H alifax L ocal N o. 25, U n ited P a perm a k ers

and P aperw orkbrs , APL-CIO,

V.

Petitioner,

J o se ph P . M oody, et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

Respondents Joseph P. Moody, et al., file this single brief

in opposition to the Petitions for a Writ of Certiorari filed

by Albemarle Paper Company, et al., in No. 74-389 and by

Halifax Local No. 25, United Papermakers and Paper-

workers, AFL-CIO in No. 74-428.

2

Questions Presented

The issues in Nos. 74-389 and 74-428 arising from the

grant of class-wide back pay are:

1. Whether, in determining whether to award compen

satory back pay, a private employer’s voluntary practices

of racial discrimination should be treated like those man

dated by state “protective” statutes which some courts

have decided justify withholding back pay in sex discrim

ination cases! (Nos. 74-389 and 74-428)

2. Whether the district courts, in the exercise of their

discretion to award back pay, should be free of appellate

guidelines effectuating the statutory purpose of according

full relief to victims of employment discrimination! (Nos.

74-389 and 74-428)

3. Whether the Court of Appeals erroneously decided

that no “special circumstances” justify denial of back pay

in this case! (No. 74-389)

4. Whether a class back pay award is incompatible with

Rule 23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, or the Con

gressional purpose of Title VII! (Nos. 74-389 and 74-428)

The issues in No. 74-389 arising from the injunction

against the testing program are:

5. Whether the EEOC Guidelines embody standards

which may be considered in evaluating an employer’s at

tempt to validate its discriminatory employment aptitude

tests!

6. Whether an employer may continue to utilize unlaw

ful employment aptitude tests while making further at

tempts to justify the tests!

3

Statement of the Case

Petitioner Albemarle’s statement of the proceedings be

low (Co. Pet. 3-4, 6-7)1 is generally accurate. In stating

the facts, however, both Petitioners neglect to mention

that Respondents and their class of black employees suf

fered severe loss of income as a result of Petitioners’

continuing practices of systemic employment discrimina

tion. The Petitions raise issues related to two distinct

aspects of those discriminatory policies: seniority and

promotional practices, and written aptitude testing.

1. Seniority and Promotional Practices.

Petitioners kept all jobs and departments strictly segre

gated until 1964 under an express policy of discrimination

(Co. Pet. App. 7-12). Segregated “extra boards” assured

that the, racial staffing of lines of progression would be

breached neither by regular promotions nor by employee

recalls (Co. Pet. App. 12-13). The district court found that

Petitioners had “intentionally” perpetuated this overtly

discriminatory system after 1965, by means of an unlawful

job seniority system (Co. Pet. App. 22-24). Neither Peti

tioner took an appeal from this obviously correct finding

although Albemarle’s Petition now implies (the record

notwithstanding) that judicial intervention was only the

handmaiden to a benevolent employer’s voluntary reform

(Co. Pet. 5).2

1 Citations in the form of “Co. Pet.” are to the Petition filed by

Albemarle Paper Company in No. 74-389. Citations to “U. Pet.”

are to the Petition of Halifax Local No. 25, the Union, in No.

74-428. The respective Petitioners are sometimes referred to as

“Albemarle” or the “Company” and the “Union” hereinafter.

2 Albemarle’s assertion that the 1968 contract adopted “plant

seniority” is erroneous. In fact that contract only allowed carry

over of job seniority into the lowest job of the transferee’s new

4

The district court found that this unlawful seniority

system limited black workers to the lower-paying depart

ments and, within “integrated” departments, to the lower-

paying jobs (Co. Pet. App. 7-13). As of June 30, 1967

there was an average pay differential between white and

black workers of approximately $0.55 per hour or $1,144.00

per average work year; in excess of 200 white workers

earned a wage a quarter per hour or more above the high

est black wage at the mill.

2. Testing and the Validation Study.

At all times since 1963, Albemarle has required satisfac

tory scores on two “paper and pencil” tests as a prerequisite

to hiring or transfer into most of the more desirable and

lucrative, i.e. all-white, jobs (Co. Pet. App. 13-14). These

tests, which included the Wonderlic (declared unlawful in

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 TT.S. 424 (1971)), dispro

portionately screened out black employees (Co. Pet. App.

38). Albemarle used its tests in precisely the same manner

condemned by Griggs.3 This case differs from Griggs only

in that here the Company made a belated effort to justify

its testing under the Griggs rule.

Albemarle made no effort to study whether its test usage

(begun in 1963) was job-related, until several months be

fore trial (Co. Pet. 5). Then it hired an expert who per-

line of progression; it did not allow for subsequent use of plant

seniority in competing for promotions'up the line (Co. Pet. App.

6). Moreover, the contract gave no one a right to transfer, but

rather left transfer requests within the Company’s sole discretion

(id.). Petitioners did not completely eliminate the unlawful fea

tures of their contract until over six years after Title VII became

effective, when they were enjoined to do so by the district court.

3 That is, blacks were required to pass the tests to gain access

to white jobs after 1965, even though many white incumbents had

not had to take or pass the tests in order to get or keep the same

jobs (Co. Pet. App. 15).

5

formed a hurried validation study riddled with manifest

deficiencies which violated EEOC Guidelines on Employee

Selection Procedures, 29 C.F.R. §§ 1607.1 et seq. (see Co.

Pet. App. 36-43). Based on this study, the expert recom

mended that the tests were valid for some jobs for which

Albemarle had required them (Co. Pet. App. 38). Albe

marle, however, continued to require tests in all instances,

using them and relying on them for its legal defense, to

screen applicants for many jobs for which there was no

evidence of job-relatedness because no study had been per

formed, or for which the study demonstrated no sig

nificant degree of job-relatedness {id.)}

ARGUMENT

I.

This Court Should Not Review the Back Pay Award.

A. There Is No Significant Conflict A m ong the Circuits as to

the P ropriety o f Class Back Pay in T itle V II Cases.

Petitioners’ arguments about a conflict of Circuits on

class back pay awards in Title VII cases overlooks the

fact that the Courts of Appeals have developed two well-

established, consistent lines of cases.

The first line arises from cases in which a private

employer and/or union voluntarily commit unlawful em

ployment discrimination not required by any state law.

Such cases typically involve racially restrictive seniority,

promotion, or transfer systems, non-job-related testing-

practices, or unjustifiable educational requirements, which

4 The same expert also studied the job-relatedness of Albemarle’s

high school education requirement and concluded that it was valid

(Co. Pet. App. 19-20). The district court rejected his conclusion

and held the requirement unlawful (id. 24) ; Albemarle did not

appeal this finding.

6

inflict economic injury on members of the class. See,

e.g., Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir,

1971) , cert, dismissed 404 U.S. 1006 (1972); Johnson v.

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Go., 491 F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974);

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211 (5th

Cir. 1974); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495

F.2d 398 (5th Cir. 1974), cert, filed October 15, 1974, No.

74-424; Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., 495 F.2d

437 (5th Cir. 1974), cert, filed September 28, 1974, No.

74-351; Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870

(6th Cir. 1973); Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 489 F.2d

496 (7th Cir. 1973), following 416 F.2d 711 (7th Cir. 1969).

The case at bar closely resembles these cases on its facts

and in the decision of the Court of Appeals.5

The cases that Petitioners rely on, denying back pay—

Kober v. Westinghouse Electric Corp., 480 F.2d 240 (3rd

Cir. 1973); Manning v. International Union, 466 F.2d 812

(6th Cir. 1972), cert, denied 410 U.S. 946 (1973); and

Schaeffer v. Yellow Cabs, Inc., 462 F.2d 1002 (9th Cir.

1972) —are from a second, easily distinguishable mold.

Each involved an employer practice limiting women’s em

ployment opportunities in obedience to mandatory state

female protective statutes. In each,6 the employer faced

a dilemma created by conflicting state and federal regula

tory statutes. In this line, the Courts of Appeals hold

that back pay should not be awarded where the employ

er’s practice was required by state legislation presump

tively valid until declared illegal under Title VII.

6 Indeed, the Fifth Circuit in Johnson and Pettway and the

Sixth Circuit in Head approve and adopt the decision of the

Fourth Circuit in this case. That decision, in turn, approves and

relies on Robinson and Bowe.

6 See also, LeBlanc v. Southern Tel. <£- Tel. Co., 333 F. Supp.

602 (E.D. La. 1971), aff’d per curiam 460 F.2d 1228 (5th Cir.

1972), cert, denied 409 U.S. 990 (1972); Rosenfeld v. Southern

Pacific Co., 444 F.2d 1219 (9th Cir. 1971).

7

Kober v. Westinghouse Electric Gorp., supra, follows the

same reasoning. There the Third Circuit rests its opinion

squarely on the logic of Manning, Schaeffer, and LeBlanc,

see 480 F.2d at 24T-248.7

Here, Petitioners’ discrimination was not required by

law but, on the contrary, violated all applicable statutes.8

There is no conflict among the Circuits on back pay on

the facts of this case.

B. T he Court o f Appeals O pinion States an A ppropriate

Standard fo r the Exercise o f D iscretion to Award B ack

Pay.

Both Petitioners direct their attack more to the standard

announced by the Court of Appeals—

a plaintiff or a complainig class who is successful in

obtaining an injunction under Title VII of the Act

should ordinarily be awarded back pay unless special

circumstances would render such an award unjust

[Co. Pet. App. 46-47]

■—than to the result in this case. But the Union Petitioner’s

Statement (and its statement of the Question Presented)

7 Kober, notwithstanding its reference to Judge Boreman’s dis

sent as noted by Petitioners, 480 F.2d at 247, in no way conflicts

with the holding in this case. The Kober holding can be read at

most to require that a district judge not be deprived of discretion

to deny back pay in the circumstances of the state protective law

eases. The Fourth Circuit’s opinion in this action allows for and

contemplates the Kober result, see Co. Pet. App. 47 n.5.

8 Faced with the same argument made by Petitioners here, the

Fifth Circuit wrote in Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.,

supra, 491 F.2d at 1377,

“Goodyear has failed to disclose to us any Texas laws which

required the invidious employment discrimination revealed

here. The reason for this efficacious omission is manifest; no

similar “protective” legislation based on racial grounds has

ever been enacted in Texas. Such an argument falls of its

own weight.”

8

seriously mischaracterizes the holding below. Contrary to

the Union’s assertions, the opinion does not “preclude the

trial court, in this and future cases, from exercising any

degree of discretion” in back pay cases (U. Pet. 8, em

phasis added); it does not “predetermine all present and

potential suits . . . within the aegis of the Fourth Circuit”

{id. 9); nor does it state an “inflexible position” {id. 9) or

a “hard and fast rule” of “mandatory back pay” {id. 10).

Rather, the Fourth Circuit has done no more or less than

decide a case and state its rationale, which will have ap

propriate precedential effect.

One of the most important functions of an appellate

court is to maintain consistency of decisions within its

Circuit, cf. Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 41 L.Ed.2d 358,

362 (1974). The Fourth Circuit’s articulation of a standard

for district courts’ exercise of discretion for awarding back

pay, an issue frequently litigated in the Circuit, promotes

and is essential to consistency.9

A standard ensuring the exercise of discretion in con

formity with statutory purposes is proper and necessary

to assure that discretionary powers are correctly utilized.

As this Court has held,

When [discretion is] invoked as a guide to judicial

action, it means a sound discretion, that is to say, a

discretion exercised not arbitrarily or willfully, but

with regard to what is right and equitable under the

circumstances and the law.

Langnes v. Green, 282 U.S. 531, 541 (1931). See also, Hecht

Co. v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321, 331 (1944) (exercise of dis-

9 This standard is not an “advisory opinion” {of. U. Pet. 11),

since it was reached and applied in hotly contested litigation of

immediate importance to the parties; rather it states a rationale

for the court’s holding in the case.

9

cretion must further legislative objectives)10; United States

v. Georgia Poiver Co., 474 F.2d 906, 921 (5th Cir. 1974);

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra, 495 F.2d at

421.

In order to effectuate the statutory purposes of Title VII,

the Fourth Circuit’s standard carefully delineates limita

tions on a district court’s discretion based on the “special

circumstances” test (Co. Pet. App. 45-47). In some “spe

cial circumstances” a denial of back pay will be appro

priate. Footnote 5 of the opinion (Co. Pet. App. 47) in

dicates at least one such circumstance, where conflicting-

mandatory state legislation is present (cf. pp. 5-7,

supra).11 The same standard has been adopted by the

Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Circuits.12 Cf. Mitchell v. De-

Mario Jewelry, Inc., 361 U.S. 288, 291-292, 296 (1960).

Petitioners urge that this Court allow district courts to

exercise an essentially standardless and unfettered dis

cretion. Their position that “discretion” allows different

district judges to read the basic remedial provision of

Title VII (Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g)) in

fundamentally different ways invites arbitrary or willful

decisions, cf. Langnes v. Green, supra. This result would

10 Accord: Schultz v. Parke, 413 F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1964);

Wirtz v. B. B. Saxon Co., 365 F.2d 457 (5th Cir. 1966).

11 Subsequently, the Fourth Circuit has affirmed another district

court’s denial of back pay based on different “special circum

stances,” Roberts v. Hermitage Cotton Mills, Inc., 498 F.2d 1397

(4th Cir. 1974), aff’g 8 BPD f 9589 (D.S.C. 1973). Moreover, back

pay will be limited to compensation for actual losses, as in Lea

v. Cone Mills Corp., 438 F.2d 86 (4t,h Cir. 1971) (Co. Pet. App.

47).

12 See, e.g., Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., supra, 491

F.2d at 1375; Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., supra, 494

F.2d at 252-253; Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., supra, 486

F.2d at 876; Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., supra, 416 F.2d at

719-720.

10

be at odds with the thrust of Title VII as remedial legisla

tion of national scope.

The legislative history of Section 706(g) demonstrates

the purpose for which Congress confided discretion to the

district courts:

The provisions of this subsection are intended to give

the courts wide discretion exercising their equitable

powers to fashion the most complete relief possible.

In dealing with the present section 706(g) the courts

have stressed that the scope of relief under that sec

tion of the Act is intended to make the victims of un

lawful discrimination whole, and that the attainment

of this objective rests not only upon the elimination of

the particular unlawful practice complained of, but

also requires that persons aggrieved by the conse

quences and effects of the unlawful employment prac

tice be, so far as possible, restored to a position where

they would have been were it not for the unlawful

discrimination, [emphasis added]

Conference Committee of the House and Senate, Section-

by-Section Analysis of IT.R. 1746, reprinted by Subcom

mittee on Labor of the Senate Committee on Labor and

Public Welfare in Legislative History of the Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Act of 1972 (1972), pp. 1844, 1848.

The Court of Appeals correctly applied the “special cir

cumstances” test.

C. The Court of Appeals P roperly Rejected the Trial Court’s

Findings of Special Circumstances.

Without fully or accurately setting out what facts and

principles the courts below relied on, Petitioner Albemarle

attacks the Court of Appeals’ failure to excuse it from

liability because of purported “special circumstances” (Co.

11

Pet. 9-11). Those facts and principles show that the Peti

tion raises no significant issue of whether “special cir

cumstances” were present here.

Albemarle incorrectly asserts that the Fourth Circuit

held the question of Petitioners’ good faith “totally ir

relevant to the question of hack pay” (Co. Pet. 9, emphasis

supplied). The Court of Appeals made no such holding;

the Court simply ruled that the district court erred in

denying back pay because it had found no “bad-faith”

Title VII violations by Petitioners (Co. Pet. App. 43-46).

The Court of Appeals decision is consistent with this

Court’s pronouncement on “intent” in Griggs v. Duke,

Power Co., supra.13 Appellate courts have uniformly held

that “good faith” imposes no bar to a back pay award.14

Similarly, Albemarle misstates the issue in contending

that a “tardy” assertion of Respondents’ back pay claim

“prejudiced” Petitioner (Co. Pet. 10). In fact Petitioner

13 [G]ood intent or absence of discriminatory intent does not

redeem employment procedures or testing mechanisms that operate

as “built-in headwinds” for minority groups and are unrelated to

measuring job capability . . . Congress directed the thrust of the

Act to the consequences of employment practices, not simply the

motivation.” 401 U.S. at 432.

14 See, e.g., Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., supra, 444 F.2d at 804;

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., supra, 491 F.2d at 1376;

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., supra, 494 F.2d at 253;

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., supra, 495 at F.2d 443;

Carey v. Greyhound Bus Co., Inc., 500 F.2d 1372, 1378-79 (5th

Cir. 1974) ; Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., supra, 486 F.2d

at 876; Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of I n f l Harvester Co.,

------ F.2d ------, 8 EPD 1J9658 (7th Cir. 1974) at pp. 5787-88.

The two Eighth Circuit cases cited by Albemarle—United States

v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry., 464 F.2d 301 (1972), cert, denied

409 U.S. 1116 (1973) ; and United States v. N. L. Industries, Inc.,

479 F.2d 354 (1973)—do not turn on the effect of good faith or

its absence, but on the proof of causal relationship between dis

crimination and economic injury and on the effect of notice of

changes in the law.

12

had express notice that Respondents sought hack pay over

one year before the start of trial. Moreover, as the Fourth

Circuit noted, the defenses to back pay in this case are

the same as the general defenses to the claim for injunc

tive relief (Co. Pet. App. 44).15 Nevertheless, Albemarle

relies on a memorandum filed early in the case in which

Respondents stated that they sought no “money damages

. . . for any member of the class not before the court” (Co.

Pet. 10 n.10) (emphasis supplied). Before the trial, the

district court entered an order on Albemarle’s motion re

quiring non-plaintiff back pay claimants to file individual

claim forms.16 Nearly one hundred persons (the majority

of the class) filed such claims which were, therefore, in

dividually “before the court” at trial. Petitioners were not

prejudiced by the assertion of the class back pay claim

below.17

Albemarle argues further that back pay should be denied

because the Company might not have dragged out this

litigation for so long, had it had specific notice that its

unlawful discrimination would prove so costly (Co. Pet. 10).

This plea is hardly cognizable in a court of equity sitting

in a Title VII case. The enactment of Title VII was suf-

15 This ruling is in accord with rulings of the Third, Fourth,

and Fifth Circuits in cases where the hack pay claim, although

not even raised until after trial, was allowed. Rosen v. Public

Service Gas & Electric Co., 409 F.2d 775, 780 n.20 (3rd Cir.

1973) ; Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., supra, 444 F.2d at 803; and

United States v. Hayes International Corp., 456 F.2d 112 121

(5th Cir. 1972).

16 Orders entered June 15, 1971 and July 8, 1971.

17 Albemarle also argued below that the early disclaimer should

now bar the back pay remedy, but the district court refused to

rely on this ground, and the Court of Appeals rejected it. A

similar disclaimer was no bar to back pay in Robinson v. Lorillard

Corp., supra.

13

ficient legal notice to discriminatory employers, see John

son v. Goodyear Tire & Rubier Co., supra, 491 F.2d at

1377.

Moreover, the district court has not yet determined how

much back pay particular class members are due; that is

its assigned task on remand. Whether or not, or to what

extent, potential liability would be affected by the equi

table factors Albemarle asserts as “special circumstances”

cannot be determined at this stage.

D. Class Back Pay Is Com patible W ith Pule 23 and the Con

gressional Purpose Expressed in Title VII.

Both Petitioners argue that as a general proposition

class back pay cannot be awarded consistent with the

provisions of Rule 23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

and the Congressional intent underlying Title VII. (See

Co. Pet. 11, U. Pet. 12-13.) These same arguments have

been uniformly rejected by the Circuits, at least six of

which now recognize the availability of class back pay,

see nn. 14, 15, supra.

Albemarle opines that a Rule 23 proceeding is “in

herently” inappropriate for a Title VII back pay case (Co.

Pet. 11). But the Advisory Committee’s Notes, 39 F.R.D.

69, 102 (1966), specifically state that the authors of

amended Rule 23 contemplated its use for civil rights

cases. See Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., supra, 444 F.2d

at 801-802. Petitioners’ theory that each class member

should be required to process his individual EEOC charge

and thereby qualify as a named plaintiff blinks at the

whole purpose of the Rule 23 amendments permitting

like claims to be joined.18

18 In the leading ease of Oatis v. Crown-Zellerlach Corp., 398

F.2d 496, 499 (5th Cir. 1968), the Court held:

Racial discrimination is by definition class discrimination,

and to require a multiplicity of separate, identical charges

14

Finally, the Fourth Circuit’s standard does not conflict

with the Congressional policy favoring an opportunity for

conciliation (cf. Co. Pet. 11, U. Pet. 12-13). That policy is

well served by the requirement that a Title VII class

action may only be maintained after exhaustion of admin

istrative remedies before the EEOC upon a charge “like

or related to” the subject matter of the suit. See, e.g.,

Sanches v. Standard Brands, Inc., 431 F.2d 455, 466 (5th

Cir. 1971) ; Miller v. International Paper Co., 408 F.2d

283, 290-291 (5th Cir. 1969). Once such a charge has been

filed, giving EEOC and respondents an opportunity to

conciliate the allegations of discrimination, further EEOC

charges from other class members would be superfluous,

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., supra, 494

F.2d at 256; and they may, without filing redundant

administrative charges, join in the class representative’s

lawsuit, Oatis v. Crown-Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496,

499 (5th Cir. 1968); Bowe v. Colgate Palmolive Co.,

supra, 416 F.2d at 720. The contrary rule urged by

Petitioners would frustrate the goal of providing mean

ingful conciliation opportunities. It would allow a dis

criminatory employer or union to evade charges of

class-wide or systemic discrimination with impunity and

to confront only the individual claims of the person who

files the EEOC charge. Such a result would be squarely

contrary to Congress’ basic purpose in enacting Title VII.

before the EEOC, filed against the same employer, as a pre

requisite to relief through resort to the court would frustrate

our system of justice and order.

Accord: Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., supra, 416 F.2d at 720.

15

II.

This Court Should Not Review the Testing Decision.

A. The Court of Appeals Correctly Considered the EEOC

Guidelines in Evaluating and Rejecting Albem arle’s Val

idation Study.

The decision below is consistent with the holding and

spirit of Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971),

which requires that Title VII courts prohibit use of dis

criminatory tests not shown to measure an employee’s abil

ity to succeed on the job. The facts are strikingly similar

to those of Griggs; Albemarle attempts to distinguish itself

from Duke Power solely on the basis of its belated valida

tion study.

The Court of Appeals did not reject that study by re

quiring “detailed and rigid compliance” with the EEOC

Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures, as Albe

marle claims (Co. Pet. 13). Rather, it criticized the expert’s

validation methods for severe inadequacies that render his

conclusions unreliable and insufficient as proof of a “man

ifest relationship” between test success and job performance

(see Co. Pet. App. 37-43).19

The majority opinion carefully analyzed the validation

study’s defects and evaluated the propriety of applying the

EEOC Guidelines standards. The opinion’s common-sense

analysis supports its legal conclusion that, as illustrated by

the facts here, the Guidelines do generally set out appro-

19 Even if the study were held to have proved what it purports

to show—limited and partial test validity—it would not justify the

Company’s overbroad test usage, see p. 5, supra. Albemarle’s

testing is thus “unvalidated” in the same sense as Duke Power’s.

16

priate standards for this case (Co. Pet. App. 38-42).20 This

is far from the slavish adherence to dry technicalities with

which Albermarle charges the court below.

B. The Court of Appeals P roperly Ordered Thai Albem arle

Be Enjoined From Using Unvalidated Discrim inatory

T ests.

The court below acted properly in directing the district

court to enjoin the testing program. Since Albemarle’s

defense failed to prove the tests job-related, Griggs for

bids their current use. Nothing in the Court of Appeals

opinion or the EEOC Guidelines would prevent the Com

pany from utilizing a testing program after it had been

properly shown to be “manifestly job related.” Yet Peti

tioner seeks an individual exemption from the rule of

Griggs: it seeks leave to use tests detrimental to black

employees before proving them valid. Indeed, Albemarle’s

argument is little more than a request for license to de

lay compliance with Title VII for a few more years.21

Not only does the Company urge that black employees be

made to wait patiently for equal job opportunities while it

20 Moreover, those Guidelines are reasonable and reflect a general

professional consensus, as numerous appellate courts have noted in

following Griggs’ suggestion that the courts accord great deference

to the Guidelines. See, e.g., United States v. Jacksonville Terminal

Co., 451 F.2d 418, 456 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 406 U.S. 906

(1972); United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906, 913 (5th

Cir. 1973) - Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211,

221 (5th Cir. 1974). Cf. Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Bridgeport

Civil Service Commission, 482 F.2d 1333, 1337 n.6 (1973); Vulcan

Society v. Civil Service Commission, 490 F.2d 387, 394 n.8 (2nd

Cir. 1974) ; Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315, 320, 326, adopted

in relevant part, 452 F.2d 327 (8th Cir. 1971) (en banc), cert,

denied 406 TJ.S. 950 (1972).

21 Since the mandate below was stayed, the Company presumably

continues to apply its tests, ten years after Title VII made them

unlawful and nearly four years after the Griggs decision.

17

litigates interminably in defense of its discredited tests;

Albemarle boldly asserts that by refusing its proposal the

Fourth Circuit abused its remedial discretion (Co. Pet.

14-15).

The order and burden of proof established for the testing

issue in Griggs would be subverted by adoption of Albe

marle’s argument. Respondents have made out their case

for relief under Griggs by proving that the tests have an

adverse impact on black employees. Albemarle cannot ask

plaintiffs, who have met their initial burden, to stand pa

tiently by as laborers while their employer seeks “ulti

mately” to meet its burden (Co. Pet. 14).

18

CONCLUSION

The Petitions for a Writ of Certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

R obert B elto n

J . L e V o n n e C h a m bers

Chambers, Stein, Ferguson

& Lanning

951 S. Independence Blvd.

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

J ack Green berg

J am es M . N abrit , III

M orris J . B aller

B arry L. G oldstein

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

C onrad O . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

P.O. Box 1428

Durham, North Carolina

T hom as T . Clayton

307 West Franklin Street

P.O. Box 236

Warrenton, North Carolina

Attorneys for Respondents

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219