Hall v. Coburn Corporation of America Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hall v. Coburn Corporation of America Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1969. 164f9221-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8897c3b9-bc69-4ad5-92eb-e837c85dab27/hall-v-coburn-corporation-of-america-brief-of-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

C j W a d . H u

L-x;nuoD K)

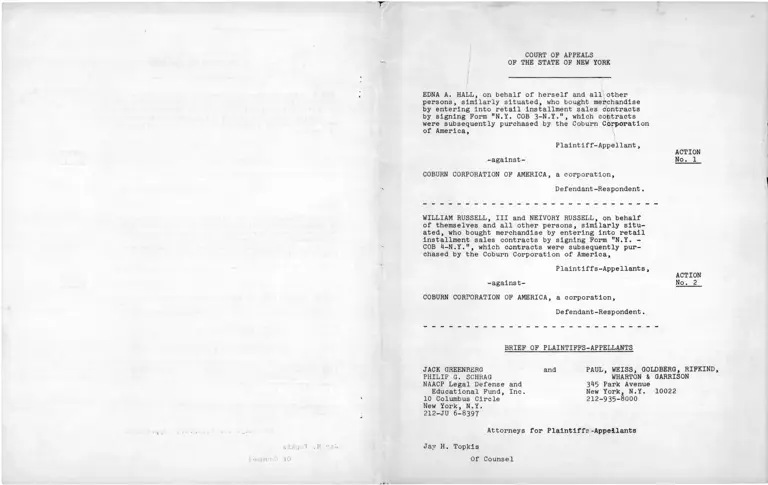

COURT OF APPEALS

OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

EDNA A. HALL, on behalf of herself and all other

persons, similarly situated, who bought merchandise

by entering into retail installment sales contracts

by signing Form "N.Y. COB 3-N.Y." , which contracts

were subsequently purchased by the Coburn Corporation

of America,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

-against-

COBURN CORPORATION OF AMERICA, a corporation,

Defendant-Respondent.

ACTION

No. 1

WILLIAM RUSSELL, III and NEIVORY RUSSELL, on behalf

of themselves and all other persons, similarly situ

ated, who bought merchandise by entering into retail

installment sales contracts by signing Form "N.Y. -

COB 4-N.Y.", which contracts were subsequently pur

chased by the Coburn Corporation of America,

Plaintiffs-Appellants, ACTION

-against- No. 2

COBURN CORPORATION OF AMERICA, a corporation,

Defendant-Respondent.

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG and

PHILIP G. SCHRAG

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y.

212-JU 6-8397

PAUL, WEISS, GOLDBERG, RIFKIND,

WHARTON & GARRISON

345 Park Avenue New York, N.Y. 10022

212-935-8000

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Jay H. Topkis

Of Counsel

COURT OP APPEALS

OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

EDNA A. HALL, on behalf of herself and all other

persons, similarly situated, who bought merchandise

by entering into retail installment sales contracts

by signing Form "N.Y. COB 3-N.Y.", which contracts

were subsequently purchased by the Coburn Corporation

of America,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

-against-

COBURN CORPORATION OF AMERICA, a corporation,

Defendant-Respondent.

WILLIAM RUSSELL, III and NEIVORY RUSSELL, on behalf

of themselves and all other persons, similarly situ

ated, who bought merchandise by entering into retail

installment sales contracts by signing Form "N.Y. -

COB 4 - N.Y.", which contracts were subsequently pur

chased by the Coburn Corporation of America,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

-against-

COBURN CORPORATION OF AMERICA, a corporation,

Defendant-Respondent.

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Questions Presented

Pursuant to leave granted by this Court on July

1969, plaintiffs-appellants ("plaintiffs") appeal from the

orders of the Appellate Division, First Department, dated

ACTION

No. 1

ACTION

No. 2

February 6, 1969, affirming without opinion the dismissal of

their complaints. These appeals raise these questions:

1. Defendant, a sales finance company, has prepared,

printed and distributed to retailers thousands of standard-

form instalment sales contracts which violate the Retail

Instalment Sales Act in the identical way: major portions of

the contracts are printed in type smaller than the 8-point man

dated by the statute. May plaintiffs and others who made pur

chases under these contracts enforce their identical statutory

rights by means of a class action?

2. Did the courts below, in denying plaintiffs and

their fellow class members effective access to the judicial

process, thereby violate their rights under the Federal and

State constitutions?

Statement of the Case

In November, 1965, plaintiff Edna Hall purchased

carpeting from a New York City merchant. In September, 1965,

Mr. and Mrs. William Russell, the other plaintiffs, purchased

carpeting from another merchant. Like thousands of other con

sumers, they signed retail instalment sales contracts which

defendant Coburn, a sales finance company, had supplied to

the merchants with whom plaintiffs dealt. As was its practice,

Coburn acquired the signed contracts from the merchants im

mediately upon consummation of the transactions.

The Coburn contract forms plainly violated Section 1

of the Retail Instalment Sales Act, Pers. Prop. L., Sec. 402(1),

in that portions were printed in type smaller than 8-point.

Mrs. Hall and the Russells brought actions to obtain

the statutory remedy conferred by Pers. Prop. L., Sec. 414(2):

recovery of the service charges paid under the unlawful contracts.

The cash price of Mrs. Hall's carpet was $580; the credit service

charge, $183.73. The cash price of the Russells' carpet was

$549-02; the credit service charge, $166.77 (64-67).*

Since Coburn's unlawful contract forms have been widely

used and have inflicted identical wrongs upon thousands of low-

income consumers, and since individual suits to recover the

small amounts at issue are practical for neither plaintiffs nor

the courts,**plaintiffs have brought these actions not only on

their own behalf but also on behalf of the other buyers whose

rights Coburn had violated in the same way.

*A11 references are to the Record on Appeal.

**New York City's Small Claims Court, whose jurisdiction is in

any event limited to $300, is not available here because Coburn

is headquartered outside of the City. N.Y.C. Civ. Ct. Act §1801

The two actions were heard together in the Supreme

Court, New York County. Special Term (Culkin, J.) dismissed

the complaints, holding that a class action could not be main

tained (25-36).

Plaintiffs took timely appeals to the Appellate Divi

sion, First Department, which affirmed unanimously, without

opinion, and denied leave to appeal (ix-xi).

On July 2, 1969, this Court granted leave to appeal

(viii) .

ARGUMENT

I.

THESE ARE PROPER CLASS ACTIONS

The Substantive Right

In 1957, in the Retail Instalment Sales Act, the

Legislature sought to correct

"[a]buses [that] have devloped over the

years in the rapidly expanding business

of instalment selling— exorbitant charges,

failure to disclose terms when a 'time

sale' was made . . . and other improper

practices."

Memorandum of Governor's Consumer Council, 1957, McKinney's

Session Laws 2113-1^-

So that consumers might know what they are buying,

the Legislature acted to compel meaningful disclosure of the

terms of all instalment sales contracts. In the very first

operative sentence of the statute, the Legislature required

that all instalment sales contracts be in writing and that

they be printed "in at least 8-point type." Pers. Prop. L.

Sec. 402(1).

The case at bar underscores the importance of the

type-size mandated by the Legislature. Coburn printed these

provisions, among others, in type too small to be comprehen

sible (65) :

— A clause whereby the buyer agrees to pay a

20$ attorney's fee for collection after

default.

— A clause whereby title to the merchandise

does not pass to the buyer until the mer

chandise is fully paid for in cash, yet

the buyer remains liable for loss or

damage.

— A clause giving the seller the right to

repossess the merchandise "without notice,

demand or legal process," and the right

to accelerate payments due, at any time

the buyer is in default.

And most important,

— A clause whereby the buyer waives, under

certain circumstances, all claims and

defenses against a good faith purchaser

for value.*

*It is perhaps unnecessary to observe that Coburn knows the

importance of ready legibility: none of its standard dunning

and collection letters is printed in type of less than 8-point

(83-84).

The Legislature provided both public and private

sanctions for violations of the Act. Willful violations are

punishable as misdemeanors, Pers. Prop. L., Sec. 414(1). And,

by way of private remedy, Section 4l4(2) provides:

"In case of failure by any person to comply

with the provisions of this article, the

buyer shall have the right to recover an

amount equal to the credit service charge

or service charge imposed in the amount of

any delinquency, collection, extension,

deferral or refinance charge imposed."

Consumers must, therefore, pay in full for merchandise purchased

under an unlawful instalment sales contract, but they have the

right to recover all service charges.

The Class Action Statute

Thus Coburn has violated the most basic provision of

the Retail Instalment Sales Act, and plaintiffs seek the remedy

which the Legislature has provided.

In these actions, plaintiffs invoke that remedy by

the only means economically feasible: a class action on behalf

of themselves and the thousands of others who have been victim

ized by Coburn's illegal conduct. The trifling recoveries to

which each member of the plaintiff class is entitled, the unavail

ability of a small claims court remedy, and the inadequacy of one

were it available--these circumstances make separate actions

inconceivable.

This State's class action statute, CPLR §1005(a),

would seem to have been tailored to deal with this situation:

"Where the question is one of common or

general interest of many persons or where

the persons who might be made parties are

very numerous and it may be impracticable

to bring them all before the court, one

or more may sue or defend for the benefit

of all."

Surely the statute's first simple and explicit test

is here met. The "question" as to all members of the plaintiff

class is the same: the size of Coburn's type. And there are

"many" persons who are interested: the thousands who have been

victimized by Coburn's intentional illegibility. Hence, "one

or more may sue . . . for the benefit of all."

The statute's second, alternative test is also satis

fied here: "the persons who might be made parties are very numer

ous and it may be impracticable to bring them all before the

court."

The simplest way to dispose of this appeal, we respect

fully submit, is to ignore all distractions and keep in mind

the statute's plain language. It is not ambiguous. It is not

imprecise. It is not subtle. Its command is clear. It requires

not construction, but application. As Mr. Justice Frankfurter

remarked for the Court in a related context, Greenwood v. United

8

States, 350 U.S. 366, 37^ (1956):

"But this is a case for applying the canon

of construction of the wag who said, when

the legislative history is doubtful, go

to the statute."

And there is further reason to read the statute as

permitting a class action here: it makes sense to do so.

Plaintiffs will be advantaged: they will be able to

have their rights vindicated in an economically feasible manner.

No purchaser victimized by Coburn could prosecute his suit alone--

today, lawyers will not take cases involving $183 or $166. But,

in a class action, the rights of all may be vindicated and counsel

may be fairly compensated.

The courts, too, will be advantaged: instead of the

thousands of litigations which might possibly be brought against

Coburn, there will be one.

And for the same reason, defendant Coburn will itself

be advantaged: it will need defend but one case, instead of

thousands.

And no one will be hurt: no members of the plaintiff

class will have his rights adjudicated in a way he might not

desire (as where possible plaintiffs in a class action have

9

several possible remedies). For here, If the class action

succeeds, each member of the plaintiff class will receive the

only remedy to which he Is entitled: there Is no other.

In the courts below, defendant suggested with an ad

mirably straight face that a class action might thrust recoveries

upon some members of the class which they did not really desire:

many would prefer, said defendant, not to enforce their statutory

rights. Perhaps this is so, perhaps Coburn is the favorite object

of charity in the ghetto— and perhaps not. In any event, any

member of the plaintiff class will surely be free to waive his

rights once they have been established in a class action the

class action will merely operate to have the rights established

economically.

Defendant, of course, professes not to see it this way.

But let us be blunt: defendant's real reason for opposing a class

action is its hope— indeed, its confidence— that, if separate

actions must be brought, they won't be brought. Because a remedy

is denied, defendant will be able to keep thousands and thousands

of dollars which under our law belong to the members of the plain

tiff class.

The CPLR was not enacted, we respectfully submit, so

to sanctify lawlessness.

10

The Prior Decisions

Special Term cited several cases— and we may antici

pate that defendant will cite more — in which class actions were

not permitted. None of these cases, we suggest, is really

apposite, for none presented the combination we have here:

thousands of prospective plaintiffs who have been wronged in

exactly the same way and who all have exactly the same remedy

and no other. And Special Term failed.to cite this Court's most

recent class action ruling broadly interpreting CPLR §1005 to

permit use of the procedure. Llchtyger v. Franchard Corp.,

18 N.Y.2d 528 (1966).

In various cases, this Court has held the class action

unavailable because the members of the asserted class had been

wronged in different ways— e.g., different representations had

made to them, Onofrio v. Playboy Club of New York, 20 A.D.2d 3

(1st Dep't 1963), reversed on dissent below, 15 N.Y.2d 7^0 (1965);

Brenner v. Title Guaranty and Trust Company, 276 N.Y. 230 (1937).

Or there were different factual situations as to each plaintiff—

e.g., those claiming racial discrimination, Gaynor v. Rockefeller,

15 N.Y.2d 120 (1965), or reliance on representations, Coolidge

v. Kaskel, 16 N.Y.2d 559 (1965). Or a class action limited to

one remedy might deprive members of the plaintiff's class of other

remedies— e.g., Societe Mlllon Athena v. National Bank of Greece,

11

281 N.Y. 282 (1939). Or defendant might have different factual

defenses to raise against individual claims, Gaynor v. Rockefeller,

supra.

But none of these differentiating factors is here pres

ent. Here, all plaintiffs have the same claim— illegally small

type. And they have only one remedy— that which the Legislature

has given. In very real terms, there is required here not adjudi

cation but administration: the simplest and most sensible course

might well be merely to require defendant to order its computer

(which has on file the names and addresses of class members) to

mail out refund checks to all whom it has wronged.

In short: this case satisfies the requirements of the

plain language of the class action statute. And nothing in the

prior decisions of this Court precludes applying that language

here.

II.

IMPORTANT CONSIDERATIONS OF PUBLIC

POLICY SUGGEST ALLOWING A CLASS

ACTION HERE-_______________ _

Success by plaintiffs in this case, involving type

size, will not remove all the evils in present-day retail sales

practices: it will not bring peace to the ghetto nor will it

12

Introduce an era of social justice.*

But the Legislature has perceived at least one vicious

wrong and afforded a clear remedy. If our society is to be per

formance rather than mere promise, this legislative plan must

not be gutted by pointless procedural hocus-pocus.

The language of the Supreme Court in Bell v. Hood, 327

U.S. 678, 684 (1946), is pertinent:

"[W]here federally protected rights have

been invaded, it has been the rule from

*For a broad view of the dangerous irritations, indeed dynamite,

generated by some consumer sales practices, see Matter of the

State of New York v. ITM, Inc. 52 Misc.2d 39 (1968); Note,

Consumer Legislation and the Poor, 76 Yale L.J. 745 (1967);

Kripke, G*esture and Reality in Consumer Credit Reform, 44 N.Y.U.

L.Rev. 1 (1969): Caplovitz, The Poor Pay More (paperback ed.

1967).

Among the more serious problems are default judgments obtained

by "sewer service," and the practice whereby sales finance com

panies supply credit forms to merchants, purchase the commercial

paper after a credit transaction, and then insist upon "holder

in due course" status so as to preclude consumer defenses. This

latter practice, not challenged in this litigation, is presently

under judicial and administrative attack. See Unieo v. Owens,

50 N.J. 101, 232 A.2d 405 (1967). This summer in New York, the

Attorney General's office held public hearings to ascertain whether

legislation is required. Antitrust and Trade Regulation Report,

September 9, 1969» ut A—21. And the Federal Trade Commission

has recently indicated it will direct its attention to the prob

lem. Antitrust and Trade Regulation Report, October 7, 1969,

at A-25.

the beginning that courts will be alert to

adjust their remedies so as to grant the

necessary relief. And it is also well

settled that where legal rights have been

invaded, and a federal statute provides

for a general right to sue for such inva

sion, federal courts may use any available

remedy to make good the wrong done."

The importance of making the class action remedy

available to enforce consumer rights cannot be overemphasized.

The difficulty and expense of vindicating consumer rights, and

the ease with which defendants are able to buy off those few

claimants who learn of and assert their rights, has made those

rights largely ineffective.

For example, Professor Kripke, long-time counsel to

the consumer credit industry, has observed that

"The question [of class suits] is of vital

importance because a broadening of the

availability of the class suit under state

procedural systems is one remedy for the

flood of litigation in which the legal ser

vices offices are presently engulfed. Its

use could end the difficulties of which the

legal services attorneys now complain— that

the individual cases brought by the small

percentage of clients who seek redress are

bought off by settlement, and that the

oppression continues unchecked for the

ignorant consumer or one who does not find

his way to a legal services office."

Kripke, supra, 44 N.Y.U. L.Rev. at 50.

See also, Comment, Translating Sympathy for Deceived Consumers

into Effective Programs for Protection, 114 U.Pa. L.Rev. 395

(1965); Note Consumer Legislation and the Poor, 76 Yale L.J.

745 (1967).

The class action remedy is, in many respects, the key

to making reality of consumer rights. Many years ago, Kalven

& Rosenfeld noted:

"Modern society seems increasingly to expose

men to such group injuries for which indi

vidually they are in a poor position to seek

legal redress, either because they do not

know enough or because such redress is dis

proportionately expensive. If each is left

to assert his rights alone if and when he

can, there will at best be a random and frag

mentary enforcement if there is any at all.

This result is not only unfortunate in the

particular case, but it will operate seriously

to impair the deterrent effect of the sanc

tions which underlie much contemporary law."

Kalven & Rosenfeld, The Contemporary Function

of the Class Suit , 8 U .Chi . L .Rev . 68J], 686 ("19̂ 1)

Ralph Nader has focused upon this particular case:

"In modern mass merchandising, fraud naturally

takes the form of cheating a great many cus

tomers out of a few pennies or dollars: the

bigger the store or chain of stores, the greater

the gain from gypping tiny amounts from indi

viduals who would not find it worthwhile to

take formal action against the seller. Class

actions solve this problem by turning the ad

vantage of large volume against the seller

that made predatory use of it in the first place.

Poverty lawyers, supported by the U.S. Office of

Economic Opportunity, are just beginning to use

thie important technique. A case of great po

tential significance for developing broad civil

deterrence has been brought in New York City

against Coburn Corp., a sales finance com

pany, by two customers who signed its retail

installment contracts. They are being assisted

by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

The plaintiffs charge that Coburn violated Sec

tion 402 of the New York Personal Property Law

by not printing its contracts in large type as

specified by law. They are asking recovery of

the credit service charge paid under the con

tracts for themselves and all other consumers

similarly involved. If the plaintiffs win,

consumers in New York will be able to bring

class actions against any violations of law

contained in any standard form contracts."

Nader, The Great American Gyp, New York Review

of Books’̂ November 21, 196 8 , p . 27 at 30.

Legal scholars agree that the present case is appro

priate for the class action remedy. See Dole, Consumer Class

Actions under Recent Consumer Credit Legislation, 44 N.Y.U. L.

Rev., 80, 105-106, 114 (1969); Starrs, The Consumer Class Action;

Considerations of Equity and Procedure, Part 2, 49 B.U. L.Rev.

407, 455-458 (1969). Cf., Weinstein-Korn-Miller, New York Civil

Practice, Para. 1005*11 (1963).

The New York City Consumer Affairs Commissioner advised

a congressional subcommittee this summer of the grant of leave to

appeal in the present cases and informed it that

"The law of our state and of all states and

the nation as well, has often been hypocri

tical as far as the consumer is concerned.

It gives him rights, but then creates economic

barriers so high that it is impossible to en

force those rights. It tells him to spend

thousands of dollars on a law suit to recover

hundreds of dollars which he lost in a swindle."

Testimony of Mrs. Grant to the Subcommittee

on the Improvement of Judicial Machinery, U.S.

Senate, July 29, 1969.

There is nothing more frustrating, or more poten

tially inflammatory and dangerous to the fabric of society,

than to legislate rights into existence, but then to make their

enforcement impossible. From this perspective, the President's

Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders has urged that the courts

take particular care to open their doors to the poor, stating

that "resourceful and imaginative uses of available legal pro

cesses could contribute significantly to the alleviation of ***

tensions." Report, at 152. And William T. Gossett, recently

president of the American Bar Association, has said,

"If we are to permit trust in a lawful society

as the straightest and broadest avenue to a

better society, we must be skillful in struc

turing all the machinery of the law [for the

benefit of everyone]." N.Y. Law Journal, p.

1, col. 3, October 29, 1968.

If the Retail Instalment Sales Act and other consumer

legislation are to be something more than promises made to the

ear but broken to the heart, the present class actions must be

permitted.

17

OTHER JURISDICTIONS HAVE READ PARALLEL

STATUTES SO AS TO PERMIT SIMILAR CLASS

ACTIONS_______________________________

A dozen jurisdictions have adopted legislation which

parallels the New York "Field Code" class-action statute.* Many

of these have construed their statutes to permit maintenance of

class actions in circumstances like those here.

III.

The leading case is Daar v. Yellow Cab Company, 67 Cal.

2d 695, 433 P.2d 732 (1967). There, an individual user of taxi

cabs in Los Angeles was permitted to bring a class action under

a California statute, C.C.P., Section 382, worded precisely like

§1005, to recover overcharges on behalf of all taxicab users who

paid their fares with scrip book coupons. The California Supreme

Court held that

"To preclude representative litigation [the

claims] must be separate and distinct in

the sense that every member of the alleged

class would have to litigate numerous and

substantial questions determining his indi

vidual right to recovery . . . following

the rendering of a ’class judgment' . . .,"

433 P.2d at 741

*Calif. CCP §382; Ohio Rev. Code Ann. §23-0721 (1953); Ark. Stat.

Ann. §27-809 (1947); Fla. R. Civ. Proc. §1.220; Okla. Stats. Ann.

§12-233; S.C. Laws §10-205 (1962); Ore. Rev. Stat. §13-170 (1967);

Conn. Gen. Stats. Ann. §52-105 (I960); Burns Ind. Stats. §2-220

(1967); Wis. Stats. Ann. §260.12 (1957); Md. Ann. Code Vol. 9B

rule 209 (1961); N.C. Gen. Stats. §1-70. See Starrs, supra, at

433ff.

18

The court noted that individual litigation would im

pose multiple burdens upon the parties and the court system,

and that without resort to the class action device no effective

remedy was available. It observed that "absent a class suit,

defendant would retain the benefits from its alleged wrongs."

433 P.2d at 746.

Other jurisdictions have similarly construed "Field

Code" class action statutes with the same wording as ours. See,

for example, Robnet v. Miller, 105 Ohio App. 536, 152 N.E.2d

763 (1957); Duke v. Boyd County, 225 Ky. 112, 7 S.W.2d 839 (1928);

Skinner v. Mitchell, 108 Kan. 86l, 197 Pac. 569 (1921).

Common law states have likewise permitted broad use of

the class action remedy in consumer litigation. For example, in

Holstein v. Montgomery Ward, No. 68 C.H. 275 (111. Sup. Ct. Cook

Co., March 11, 1969), reported in 2 C.C.H. Poverty Law Reporter,

Para. 9652, pp. 10,784-95 (1969), use of a class action was per

mitted in a suit on behalf of six million revolving charge account

customers who alleged that the defendant unlawfully charged them

for credit life insurance although they had not affirmatively

asked for it.

Finally, the federal courts have made the class action

sanctioned by Rule 23(b), F.R.C.P., an invaluable tool in effectu

ating the rights of people whose individual claims would not support

litigation or would burden the parties and the judicial system.

See, for example, Eisen v. Carlisle and Jacquelin, 391 F .2d 555

(2d Cir. 1968) (suit by odd-lot purchasers challenging the stan

dard odd-lot differential); Dolgow v. Anderson, 43 F.R.D. 472

(E.D.N.Y. 1968) (class action on behalf of purchasers of stock);

and Siegel v. Chicken Delight, Inc., 271 F .Supp. 722 (N.D.Cal.

1967) (suit on behalf of 700 franchisees).

In Eisen, supra, Judge Medina noted that

"Class actions serve an important function

in our judicial system. By establishing a

technique whereby the claims of many indi

viduals can be resolved at the same time,

the class suit eliminates the possibility

of repetitious litigation and provides

small claimants with a method of obtaining

redress for claims which would otherwise be

too small to warrant individual litigation

. .~ [This is particularly important where]

there is no public administrative body that

could ensure repayment, so the responsibility

must ultimately rest on the judicial system."

391 F.2d 560, 567 (Emphasis added.)

Of course, these decisions are not binding upon this

Court. But they do demonstrate the tremendous utility of the

class action, and they indicate that there is nothing in the

language of the New York statute or in the concept of the class

action which requires the denial of the relief sought here.

20

TO DENY THE CLASS ACTION REMEDY HERE

WOULD DEPRIVE PLAINTIFFS OF THEIR

CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS_______________

The effect of the decision below is to deny plaintiffs,

as well as the thousands of people who signed identical unlawful

agreements, an opportunity to use this State's judicial machinery

to enforce substantive rights granted by the Legislature.

Of course, if plaintiffs had larger individual claims,

they could easily find counsel to plead for them— a plaintiff

wealthy enough to purchase a Cadillac under an illegal instalment

sales contract could press his suit to recover thousands of dollars

of service charges.

Thus the effect of the decision below is to bar the

courts to the poor when they are open to the wealthy. Both

Federal and State constitutions preclude this result.

No state may bar access to its facilities on the basis

of economic status. Harper v. Virginia Bd. of Electors, 383 U.S.

663 (1966); Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956): see, also,

People v. Montgomery, 24 N.Y.2d 130 (1969)• Nor many unessen

tial procedural requirements be used to obstruct access to the

courts. Lefton v. City of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, 333 F . 2d

280 (5th Cir. 1964) (procedures on removal). Appellant's right

to a day in court, even in a suit for money damages, is a political

right and a fundamental requisite of due process of law, Railway

IV.

21

Trainmen v. Virginia Bar, 377 U.S. 1 (1964); Mine Workers v.

Illinois Bar Ass'n, 389 U.S. 217 (19 6 7) 5 Schroeder v. New York,

371 U.S. 208 (1962). See Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483 (1969).

Any barrier to effective implementation of their rights

by the poor or by those otherwise unable economically to vindi

cate them is not permissible absent an "appreciable public interest"

to the contrary. Railway Trainmen v. Virginia Bar, 377 U.S. at 8;

Lefton v. City of Hattiesburg, Mississippi. None has been sug

gested in the present case, and none exists.

CONCLUSION

As so often, Cardozo gives us our guide, Falk v. Hoffman,

233 N.Y. 199, 202 (1922)

"Equity will not be over-nice in balancing

the efficacy of one remedy against the

efficacy of another when action will baffle,

and inaction may confirm, the purpose of

the wrongdoer."

We ask that the judgments below be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

PAUL, WEISS, GOLDBERG, RIFKIND,

WHARTON & GARRISON

JACK GREENBERG

PHILIP G. SCHRAG

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Jay H. Topkis

Of Counsel