Norwood v. Harrison Motion to Dismiss or Affirm and Brief in Support of Motion to Dismiss

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Norwood v. Harrison Motion to Dismiss or Affirm and Brief in Support of Motion to Dismiss, 1972. a4c9c1fc-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/88bff057-8405-4762-aca7-60842b8e79c5/norwood-v-harrison-motion-to-dismiss-or-affirm-and-brief-in-support-of-motion-to-dismiss. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

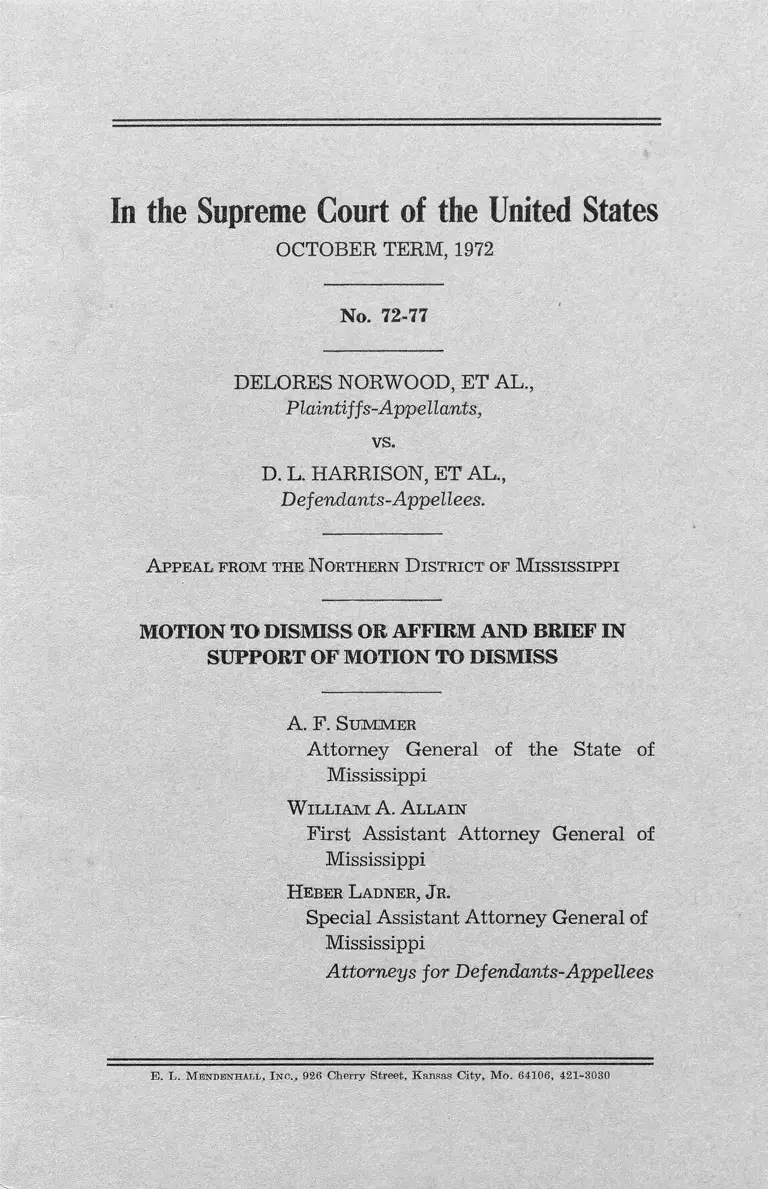

In the Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1972

No. 72-77

DELORES NORWOOD, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

D. L. HARRISON, ET AL.,

Defendants-Appellees.

A ppeal from the Northern D istrict of M ississippi

MOTION TO DISM ISS OR AFFIRM AND BRIEF IN

SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS

A. F. Summer

Attorney General of the State of

Mississippi

W illiam A. A llain

First Assistant Attorney General of

Mississippi

Heber Ladner, Jr.

Special Assistant Attorney General of

Mississippi

Attorneys for Defendants-Appellees

E. L . M endenhall,. I n c ., 926 Cherry Street, Kansas City, M o. 64106, 421-3030

TABLE OF CONTENTS

MOTION TO DISMISS OR AFFIRM.............. ,............. 1

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS—

Facts ......................... - .......-...... ...... ...... -....................... 3

A. The Claim ........................... ..................... -.......3

Argument—

I. Aid to Students in Private and Parochial

Schools by Lending Them Textbooks Does Not

Violate the Fourteenth Amendment .............. 5

II. The Mississippi Statute Does Not Foster Seg

regated Schools in Purpose or E ffect.............. 8

Conclusion ................................-...................-...........—- 10

Table of Authorities

Cases

Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203, 83

S.Ct. 1560, 10 L.Ed.2d 844 (1963) ........................... ..... 5

Board of Education v. Allen, 392 U.S. 236, 88 S.Ct. 1923,

20 L.Ed.2d 1060 (1968) ................................................ 5, 7

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715,

81 S.Ct. 856, 6 L.Ed.2d 45 (1961) ........................... . 7

Cochran v. Louisiana State Board of Education, 281

U.S. 370, -50 S.Ct. 335, 74 L.Ed. 913 (1930) .............. 6

Coffey v. Education Finance Commission, 275 F. Supp.

854 (S.D. Miss.) ................................................. ........... 9

Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1, 67 S.Ct. 504,

91 L.Ed. 711 (1947) ....................................................... 5

Follett v. Town of McCormick, 321 U.S. 573, 64 S.Ct.

717, 88 L.Ed. 938 (1944) ............................................. 5

II

Irvis v. Moose Lodge #107, 40 L.W. 4715 (No. 70-75,

June 12, 1972) ..................................................... -........ 7,8

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602, 91 S.Ct. 2105, 29

L.Ed.2d 745 (1971) ................................................... 5,6

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 395 U.S. 298, 83 S.Ct.

1119, 10 L.Ed.2d 323 (1963) ........................................ ?

Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance Commis

sion, 275 F. Supp. 833 (S.D. La., 1967), affirmed, 389

U.S, 571 (1968) ........................................ 8,9

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369, 87 S.Ct. 1627, 18

L.Ed.2d 830 (1967) ....................................................... 9

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, 68 S.Ct. 836, 92 L.Ed.

1161 (1948) .................................................................... ?

Walz v. Tax Commission, 397 U.S. 664, 90 S.Ct. 1409, 25

L.Ed.2d 697 (1970) ................................-.............. — 6

Constitutional Provisions

and' Statutes

Constitution of the United States—

First Amendment........................................... ------.......... 5

Fourteenth Amendment............................ -.............. 5, 7,10

Section 6656, Mississippi Code of 1942 ......................... 4,7

In the Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1972

No. 72-77

DELORES NORWOOD, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

D. L. HARRISON, ET AL.,

Defendants-Appellees.

A ppeal from the Northern D istrict of M ississippi

MOTION TO DISMISS OR AFFIRM

Appellees move the Court, under Supreme Court Rule

16, to dismiss the appeal in that it does not present a sub

stantial federal question as to the claim that (1) a 1940

law providing loaned textbooks to all individual students

in both public and private schools violates equal protec

tion.

Alternatively, appellees move the Court to affirm the

final judgment of the District Court on the ground that

it is manifest that the questions upon which the decision

of the cause depends are so insubstantial as not to need

further argument: (1) Because the claim that textbook

loans to individual students in both public and private

schools is unconstitutional is obviously without merit and

2

because its unsoundness is unmistakably clear from the

previous decisions of this Court.

It is, therefore, respectfully moved that this appeal

be dismissed and, in the alternative, that the judgment of

the District Court denying all relief be affirmed.

Respectfully moved this 8th day of August, 1972.

A. F. Sum m er

Attorney General of the State of

Mississippi

W illiam A. A llain

First Assistant Attorney General of

Mississippi

Heber L adner, Jr.

Special Assistant Attorney General of

Mississippi

3

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO DISMISS

FACTS

A. The Claim.

Delores Norwood and other members of the plaintiffs’

class are black public school students of the Tunica County,

Mississippi, School District. The defendants, D. L. Harri

son, et al., are members of the Mississippi State Textbook

Purchasing Board. The plaintiffs, in attendance at the de

segregated unitary Tunica County School System, brought

suit to enjoin the defendants from providing or permitting

the distribution or sale of state owned textbooks to private

racially segregated schools and academies. Their standing

to sue was alleged to spring from their right to a totally

nondiscriminatory school system and their further right to

elimination of state support for racially segregated schools,

which right had allegedly been frustrated by the creation

of a racially segregated Tunica County institute of learning.

The statistical and empirical evidence marshalled by

the plaintiffs to show a supposed connection between the

growth and health of a private school system in Mississippi

and the provision for textbooks cannot obscure the thrust

of their complaint. The plaintiffs are enjoying their con

stitutionally grounded right to a unitary public school

system. While the trial produced evidence of a with

drawal from public education in several Mississippi school

districts, there was no proof that the statutory promise,

existent since 1940, of provision for textbooks wherever a

given student attended, was any moving force in the

changes which ensued in student population. The three-

judge Court found that ninety per cent (90%) of those

students previously in public schools remain there.

4

Section 6656 of the Mississippi Code of 1942, mandates

the distribution of free textbooks to Mississippi school

children:

“This act is intended to furnish a plan for the

adoption, purchase, distribution, care and use of free

textbooks to be loaned to the pupils in all elementary

and high schools of Mississippi. The books herein pro

vided by the board shall be distributed and loaned free

of cost to the children of the free public schools of the

state, and all other schools located in the state which

maintain educational standards equivalent to the

standards established by the State Department of Edu

cation for the state schools.”

Children in private schools have access to these books

based on only one discretionary factor. The school attended

must maintain educational standards equivalent to the

standards of the State Department of Education.

The terms of the statute leave no room for interpreta

tion. Since 1940, free textbooks have been provided to

the children attending all private schools in each instance

where textbook aid has been requested or recommended

by representatives of the children or upon recommenda

tion of a third party. Children attending all private and

parochial schools located in the State are entitled to free

textbooks under the statute if the school they are attending

is located in the State and maintains the standards of the

State Education Department. It is significant to note that

the textbooks are loaned to individual students, even

though distribution is handled through the school. The

subsidy, if it be a subsidy, is certainly de minimis. The

annual per pupil expenditure for new or replacement books

is a mere six dollars.

5

Unquestionably, children attending newly formed pri

vate schools are enjoying the textbooks. The board, with

out an alternative, had to provide books to these students.

Otherv/ise, thousands of carefully selected state owned

textbooks would have been rendered useless, since they

had already been allocated to each child.

ARGUMENT

I.

Aid to Students in Private and Parochial Schools

by Lending Them Textbooks Does Not Violate the

Fourteenth Amendment.

For the purposes of constitutional adjudication, the

contours of forbidden action under the First Amendment’s

establishment of religion clause, should be analogous to

but more stringent than standards applicable to forbidden

state action under the Fourteenth Amendment.1 Just as

a state action may not foster an established religion, it may

not support racial discrimination. This Court’s precedents

concerning state provision for assistance to pupils in sec

tarian schools require affirmance in this case. Board of

Education v. Allen, 392 U.S. 236, 88 S.Ct. 1923, 20 L.Ed.2d

1060 (1968); Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1,

67 S.Ct. 504, 91 L.Ed. 711 (1947); Abington School District

v. Schempp, 374 U.S, 203, 83 S.Ct. 1560, 10 L.Ed.2d 844

(1963).

It is likewise certain from Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403

U.S, 602, 91 S.Ct. 2105, 29 L.Ed.2d 745 (1971) that state

aid to religious institutions which offends the First Amend

ment is direct institutional aid which results in an inter

1. The rights protected or secured from abridgment under

the First Amendment are said to occupy a preferred position.

Follett v. Town of McCormick, 321 U.S. 573, 64 S.Ct. 717, 88

L.Ed. 938 (1944).

twined relationship between the government and the re

ligious authority. Id. at 757. “ Neutral, or nonideological

services, facilities or materials” may be provided free of

the Establishment clause if they are given in common to

all students. In striking down Pennsylvania’s aid to de

fray teachers’ salaries in church related schools, the Kurtz-

man Court found that the aid ran afoul of the carefully

preserved distinction that aid must flow to the student and

not to the church related school per se. Id. at 760. Non

student centered financial assistance has likewise been up

held for churches but only in the context where the in

volvement of the state is not excessive and where there

is no continuing call for state surveillance or entangle

ment. Walz v. Tax Commission, 397 U.S. 664, 90 S.Ct. 1409,

25 L.Ed.2d 697 (1970). While the tax exemption was to

benefit the institution directly, it was saved by virtue of

its application to all denominations and by the harshness

that might be worked by taxing church property.

This Court has unerringly considered whether a given

enactment has “a secular legislative purpose and a primary

effect that neither advances nor inhibits religion.” Ever

son, supra, at 858. The fact that aid may have assisted a

given religious institution did not, in the cited cases, de

flect this Court from considering the recipient of the aid

and not the institutional by-product of that assistance.

Specifically, the Allen Court reaffirmed Cochran v. Louisi

ana State Board of Education, 281 U.S. 370, 50 S.Ct. 335,

74 L.Ed. 913 (1930), holding that state wide provision for

free textbooks to all students was permissible under the

Fourteenth Amendment in that the state may further sec

ular education through private schools as a proper public

concern.

This Court treated the argument that free school books

assist students in attending sectarian and parochial schools

6

7

as of no consequence. Even though the textbook aid was

certainly of some value to the religious school, this Court

acknowledged that line drawing was necessary, and that

the aid was not so direct or substantial as to violate the

Establishment clause. Allen, supra, at 1065. This line

drawing function is more sharply delineated in the Four

teenth Amendment cases in which the Court’s formulation

has been that the state must “ insinuate itself into a position

of interdependence [with otherwise private persons] . . .

so that they must be recognized as a joint participant in

the challenged activity.” Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U.S. 715, 81 S.Ct. 856, 6 L.Ed.2d 45 (1961).

Surely six dollars ($6.00) per year per pupil expenditure,

when all students of every race enjoy that benefit, cannot

be said to be unconstitutional state aid. Furthermore, the

notion that Section 6656 aids schools is at variance with

the facts. No funds are provided to the school because the

textbooks are loaned to the students, and ownership of

the books remains in the state. These were significant

facts in Allen, and they are significant facts here.

The Court has lately addressed itself to the degree

of state action necessary to bring the Fourteenth Amend

ment into play. Irvis v. Moose Lodge #107, 40 L.W. 4715

[No. 70-75, June 12, 1972]. There our position was re

affirmed in the assertion that private discrimination does

not offend equal protection merely because “the private

entity receives any sort of benefit from the State . . .” Id.

at 4718. To violate equal protection the state must be

commanding a discriminatory result by its machinery.

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S, 1, 68 S.Ct. 836, 92 L.Ed. 1161

(1948); Peterson v. City of Greenville, 395 U.S, 298, 83

S.Ct. 1119, 10 L.Ed.2d 323 (1963). Here, the Mississippi

statute providing textbooks is in no such “symbiotic” re

8

lationship with private discrimination. Irvis, supra, at

4718.

One final factor cuts in favor of affirmance. Should

the case be reversed, the District Court must decide which

of 107 private schools can receive books. Stated “open

door” policies must be looked into. Determinations must

be reached as to the quantity of integration necessary to

avoid the textbook ban. Further, what standard should

be used for the state’s Catholic schools which have scant

numbers of black students?

II.

The Mississippi Statute Does Not Foster Segre

gated Schools in Purpose or Effect.

Judge John Minor Wisdom, writing for a three-Judge

Court which enjoined Louisiana’s tuition grant system,

distinguished this case:

“Any aid to segregated schools that is the product

of the State’s affirmative, purposeful policy of fos

tering segregated schools and has the effect of en

couraging discrimination is significant state involve

ment in private discrimination. (We distinguish,

therefore, state aid from tax benefits, free school

books, and other products of the State’s traditional

policy of benevolence toward charitable and educa

tional institutions.)” Poindexter v. Louisiana Finan

cial Assistance Commission, 275 F. Supp. 833.

This ipse dixit from Judge Wisdom seems particu

larly appropriate since his rationale would void “any state

aid” if the purpose and effect were suspect.

The proscription on state aid fostering private dis

crimination has fallen upon

9

“aid which is the product of the state’s affirmative,

purposeful policy of fostering segregated schools and

has the effect of encouraging discrimination . .

Coffey v. Educational Finance Commission, 275 F.

Supp. 854 (S.D. Miss.).

The state must significantly encourage private dis

crimination both in purpose and effect. Reitman v. Mul-

key, 387 U.S. 369, 87 S.Ct. 1627, 18 L,Ed.2d 830 (1967).

The purpose is to be judged by the natural and probable

effect of the legislation. Poindexter v. Louisiana Finan

cial Assistance Commission, 275 F. Supp. 833 (S.D. La.,

1967), affirmed, 389 U.S. 571 (1968).

Neither in purpose nor effect does the Mississippi Text

book law foster segregated schools. Unlike the tuition

grants, it is a “neutral statute” without racial motivation.

On the other hand, all the tuition grants were thinly

veiled segregation statutes. Tuition grants were direct

aid. As stated in Poindexter, “The private schools es

tablished in Louisiana are direct beneficiaries of the

grants in aid; the children or the parents are conduits

to the school.” Poindexter, supra, at 852. Here textbook

aid goes directly to the student.

The relationship between the growth of private schools

in step with the increased revenue from tuition grants is

well documented. Here, no such link is established and

cannot be in the face of the unchallenged finding that

90% of the students remain in public schools.

10

CONCLUSION

State statute’s provision for loans of textbooks to

all students in both public and private schools does not

offend the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Neither does the Mississippi statute foster

segregated schools in a way which would invalidate the

statute.

Appellees submit that the appeal from the judgment

of the District Court denying all relief should be dis

missed, or, in the alternative, that the Judgment and

Opinion upon which it is based should be affirmed with

out further briefing and argument.

Respectfully submitted,

A. F. Summ er

Attorney General of the State of

Mississippi

W illiam A. A llain

First Assistant Attorney General of

Mississippi

Heber Ladner, Jr.

Special Assistant Attorney General of

Mississippi