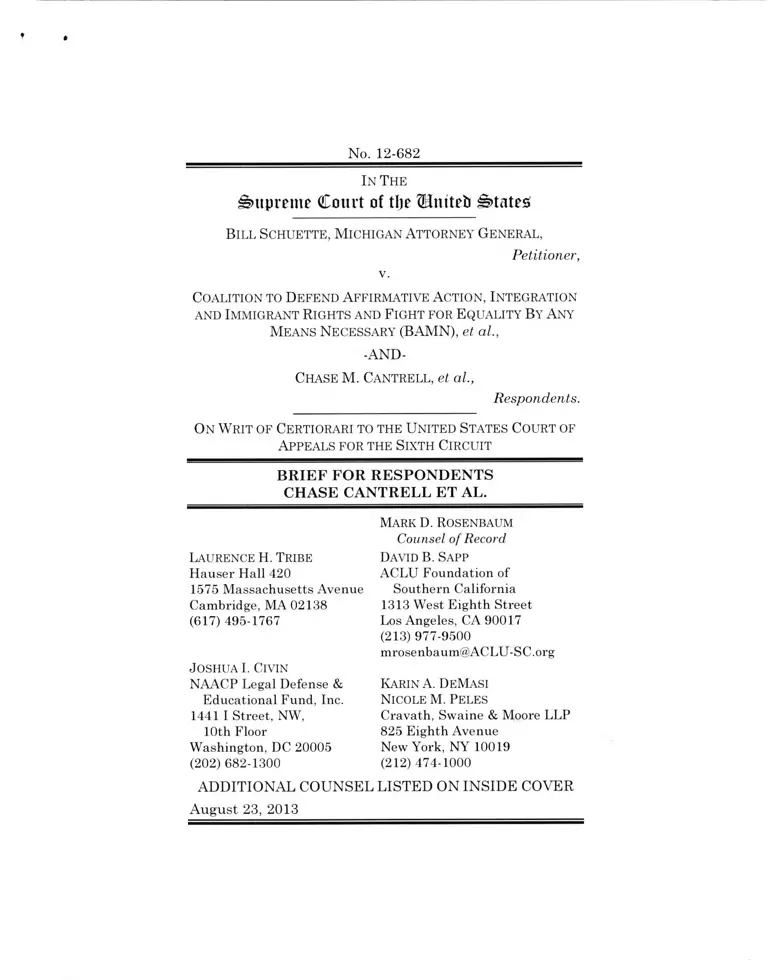

Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

August 23, 2013

74 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action Brief for Respondents, 2013. c71c8cc8-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/88d6debc-f1f0-4b95-a17e-f1cdb7f2b0f0/schuette-v-coalition-to-defend-affirmative-action-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

t

In T h e

Supreme Court of tlje SJnttet) States

________________No. 12-682________________

B il l S c h u e t t e , M ic h ig a n A t t o r n e y G e n e r a l ,

Petitioner,

v.

C o a l it io n to D e f e n d A f f ir m a t iv e A c t io n , In t e g r a t io n

a n d Im m ig r a n t R ig h t s a n d F ig h t fo r E q u a l it y B y A n y

M e a n s N e c e s s a r y (BAMN), et al,

-AND-

C h a s e M . Ca n t r e l l , et al.,

Respondents.

O n W r it o f C e r t io r a r i t o t h e U n it e d S t a t e s C o u r t of

A p p e a l s f o r t h e S ix t h C ir c u it

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

CHASE CANTRELL ET AL.

La u r e n c e H. Tribe

Hauser Hall 420

1575 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

(617) 495-1767

Jo sh u a I. Civin

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

1441 I Street, NW,

10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

M a r k D. Ro se n b a u m

Counsel of Record

David B. Sapp

ACLU Foundation of

Southern California

1313 West Eighth Street

Los Angeles, CA 90017

(213) 977-9500

mrosenbaum@ACLU-SC.org

Ka r in A. D eMa si

N icole M. Peles

Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP

825 Eighth Avenue

New York, NY 10019

(212) 474-1000

ADDITIONAL COUNSEL LISTED ON INSIDE COYTIR

August 23, 2013

mailto:mrosenbaum@ACLU-SC.org

E r w in Ch e m e r in s k y

University Of California,

Irvine School Of Law

401 East Peltason Drive,

Suite 1000

Irvine, CA 92697

(949) 824-7722

S h e r r il y n If il l

D a m o n T . H e w it t

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

40 Rector Street,

5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

(212) 965-2200

S t e v e n R. S h a p ir o

D e n n is D . Pa r k e r

ACLU Foundation

125 Broad Street,

18th Floor

New York, NY 10004

(212) 549-2500

M e l v in B u t c h

H o l l o w e l l , J r .

Detroit Branch NAACP

8220 Second Avenue

Detroit, MI 48202

(313) 980-0102

K a r y L. M o ss

M ic h a e l J. St e in b e r g

M a r k P. Fa n c h e r

ACLU Fund Of Michigan

2966 Woodward Avenue

Detroit, MI 48201

(313) 578-6814

Je r o m e R. W a t s o n

Miller, Canfield, Paddock

And Stone, P.L.C.

150 West Jefferson,

Suite 2500

Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 963-6420

D a n ie l P. T o k a ji

The Ohio State University

Moritz College Of Law

55 West 12th Avenue

Columbus, OH 43206

(614) 292-6566

Counsel for Cantrell Respondents

1

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether a state violates the Equal Protection

Clause by amending its constitution to prohibit

race- and sex-based discrimination or preferential

treatment in public-university admissions decisions.

11

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING

Petitioner is Bill Schuette, Michigan Attorney

General. Respondents are Chase Cantrell, M.N., a

minor child, by Karen Nestor, Mother and Next

Friend, Karen Nestor, Mother and Next Friend of

M.N., a minor child, C.U., a minor child, by Paula

Uche, Mother and Next Friend, Paula Uche, Mother

and Next Friend to C.U., a minor child, Joshua Kay,

Sheldon Johnson, Matthew Countryman, M.R., a

minor child, by Brenda Foster, Mother and Next

Friend, Brenda Foster, Mother and Next Friend of

M.R., a minor child, Bryon Maxey, Rachel Quinn,

Kevin Gaines, Dana Christensen, T.J., a minor child,

by Cathy Alfaro, Guardian and Next Friend, Cathy

Alfaro, Guardian and Next Friend of T.J., a minor

child, S.W., a minor child, by Michael Weisberg,

Father and Next Friend, Michael Weisberg, Father

and Next Friend of S.W., a minor child, Casey

Kasper, Sergio Eduardo Munoz, Rosario Ceballo,

Kathleen Canning, Edward Kim, M.C.C., II, a minor

child, by Carolyn Carter, Mother and Next Friend,

Carolyn Carter, Mother and Next Friend of M.C.C.,

II, a minor child, J.R., a minor child, by Matthew

Robinson, Father and Next Friend, and Matthew

Robinson, Father and Next Friend of J.R., a minor

child (together, the “Cantrell Respondents”).

In the consolidated case, there is a separate

group of Respondents, which includes the Coalition

to Defend Affirmative Action, Integration and

Immigrant Rights and Fight for Equality by Any

Means Necessary (BAMN), United for Equality and

Affirmative Action Legal Defense Fund, Rainbow

Push Coalition, Calvin Jevon Cochran, Lashelle

Benjamin, Beautie Mitchell, Denesha Richey, Stasia

iii

Brown, Michael Gibson, Christopher Sutton, Laquay

Johnson, Turqoise Wiseking, Brandon Flannigan,

Josie Human, Issamar Camacho, Kahleif Henry,

Shanae Tatum, Maricruz Lopez, Alejandra Cruz,

Adarene Hoag, Candice Young, Tristan Taylor,

Williams Frazier, Jerell Erves, Matthew Griffith,

Lacrissa Beverly, D’Shawn Featherstone, Danielle

Nelson, Julius Carter, Kevin Smith, Kyle Smith,

Paris Butler, Touissant King, Aiana Scott, Allen

Vonou, Randiah Green, Brittany Jones, Courtney

Drake, Dante Dixon, Joseph Henry Reed, AFSCME

Local 207, AFSCME Local 214, AFSCME Local 312,

AFSCME Local 386, AFSCME Local 1642, AFSCME

Local 2920, and the Defend Affirmative Action Party

(together, the “Coalition Respondents”)- Additional

defendants below are the Regents of the University

of Michigan, the Board of Trustees of Michigan State

University, the Board of Governors of Wayne State

University, Mary Sue Coleman, Irvin D. Reid, and

Lou Anna K. Simon.

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTION PRESENTED............................................. i

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING............................. ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES......................................... vi

INTRODUCTION............................................................1

STATEMENT..................................................................7

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT..................................... 13

ARGUMENT.................................................................19

I. THE POLITICAL RESTRUCTURING

DOCTRINE IS CONSISTENT WITH, AND

A NECESSARY COMPONENT OF, THIS

COURT’S EQUAL PROTECTION

JURISPRUDENCE............................................... 19

A. This Court Has Long Recognized That

the “Peculiar and Disadvantageous”

Treatment of Racial Matters in the

Political Process Is a Racial

Classification Subject to Strict

Scrutiny......................................................... 19

B. Structuring the Political Process Based

on Racial Considerations Is

Particularly Likely To Underscore That

Race Is a Significant and Outcome-

Determinative Factor Within Our

Political System............................................27

V

C. The Political Restructuring Doctrine

Applies to All Manipulations of the

Political Process That Cannot Be

Explained on Grounds Other Than

Race................................................................33

D. The Political Restructuring Doctrine

Entails Straightforward Factual

Inquiries and Is Integral to a Coherent

Equal Protection Doctrine............................36

II. PROPOSAL 2 VIOLATES THE EQUAL

PROTECTION CLAUSE UNDER THE

POLITICAL RESTRUCTURING

DOCTRINE............................................................ 47

A. Proposal 2 Created a Racial

Classification................................................. 47

B. Proposal 2 Does Not Advance a

Compelling Interest...................................... 56

C. Proposal 2 Is Not Narrowly Tailored.........57

III. STARE DECISIS COUNSELS AGAINST

THE DRAMATIC STEP OF OVERRULING

OR SUBSTANTIALLY LIMITING THE

POLITICAL RESTRUCTURING

DOCTRINE............................................................ 60

Page

CONCLUSION 62

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page(s)

Cases

Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena, 515

U.S. 200 (1995)..............................................passim

Allen v. State Bd. of Elections, 393 U.S.

544 (1969)............................................................... 25

Avery v. Midland. Cnty., 390 U.S. 474

(1968)...................................................................... 25

Bd. of Regents of the Univ. of Mich. v.

Auditor Gen., 132 N.W. 1037 (Mich.

1911).........................................................................53

Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996).....................passim

City of Arlington v. FCC, 133 S. Ct. 1863

(2013)........................................................................45

City of Richm ond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488

U.S. 469 (1989)................................... 28, 45, 51, 57

Crawford u. Bd. of Educ., 458 U.S. 527

(1982).................................................................. 5, 42

Easley v. Crornartie, 532 U.S. 234 (2001)......... 22, 56

Fisher v. Univ. of Tex., 133 S. Ct. 2411

(2013)............................................................... passim

Gornillion v. Light foot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960)..... 25, 38

Gordon v. Lance, 403 U.S. 1 (1971)...........................22

vi

Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 244 (2003)..................... 7

Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003)........ passim

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347

(1915)...................................................................... 25

Hormel v. Helvering, 312 U.S. 552 (1941)............... 56

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969)..........passim

Hunter v. City of Pittsburgh, 207 U.S. 161

(1907)...................................................................... 39

Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985).............. 49

James v. Valtierra, 402 U.S. 137 (1971)............ 38, 59

League of United Latin Am. Citizens v.

Perry, 548 U.S. 399 (2006)............................. 24, 25

Lee v. Nyquist, 318 F. Supp. 710 (W.D.N.Y.

1970), aff’d, 403 U.S. 935 (1971).................. 20, 41

Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995)............. 22, 30

Mistretta v. United States, 488 U.S. 361

(1989)........................................................................54

New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S.

262 (1932)............................................................... 39

Parents Involved in Cmty. Sell. v. Seattle

Sch. Dist. No. 1, 551 U.S. 701 (2007).......... passim

V ll

Page(s)

vm

Pers. Adm’r of Mass. v. Feeney, 442 U.S.

256 (1979)......................................................... 37, 50

Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 505 U.S.

833 (1992)....................... ....................................... 60

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964).............. 25, 26

Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996).................. 4, 50

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993)...................passim

Singleton v. Wulff, 428 U.S. 106 (1976)................... 56

United States v. Carotene Prods. Co., 304

U.S. 144 (1938)................................................. 27, 35

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metro.

Housing Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252

(1977)............................................................... passim

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976)..............37

Washington v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1, 458

U.S. 457 (1982)............................................... passim

Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52 (1964)................25

Statutes & Rules

Mich. Const, art. I, § 26........................................... 9, 48

Mich. Const, art. VIII, § 5 ......................................... 7, 52

Mich. Const, art. XII, §§ 1 & 2 ...................................55

Page(s)

IX

Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. §§ 390.3-.5 (West

2011)....................................................................... 52

Other Authorities

League of Women Voters 2005 General

Election Voter Guide, available at

http://www.lwvka.org/guide04/regents.

htm l.........................................................................53

Page(s)

http://www.lwvka.org/guide04/regents

INTRODUCTION

Before Proposal 2 was enacted in November

2006, the Michigan Constitution granted plenary

authority over all matters relating to the state’s

public universities, including authority to establish

admissions criteria, to each university’s Board of

Regents. Supporters of Proposal 2 mobilized in

direct reaction to this Court’s decision in Grutter v.

Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 340, 343 (2003), holding that

Michigan Law School’s policy of considering race as

one factor among many in a holistic, individualized

review of admissions applications was

constitutionally permissible. Proposal 2’s supporters

sought not only to repeal the constitutionally

permissible race-conscious admissions policies that

universities had developed in the wake of Grutter,

instead, they sought to permanently ban such

policies by embedding a prohibition against them in

the state constitution and thereby changing—along

explicitly racial lines—the political structure

traditionally employed by the State of Michigan to

make higher educational policy.

Following Proposal 2’s enactment, the Boards of

Regents are prohibited by the state constitution from

retaining their constitutionally permissible race

conscious admissions programs or from adopting new

constitutionally permissible policies. They retain

plenary authority over all other matters, however,

including whether to include countless other

constitutionally permissible criteria in their

admissions programs. Consequently, a student who

believes that her family’s alumni connections (or

experience as a member of a Christian service group

or living in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula) should

2

receive greater weight in the admissions process can

advocate to the Boards of Regents—or to the

university officials to whom they have delegated

authority over admissions policy—with a chance of

success. In contrast, post-Proposal 2, if a student

believes that the admissions process should consider

how she would contribute to promoting diversity

within the university community based on her

experiences as an African-American woman, she has

no choice but to undertake the far more onerous

process of amending the state constitution to

authorize again constitutionally permissible race

conscious admissions programs.

Launched by opponents of constitutionally

permissible race-conscious admissions programs

after they lost in Grutter, Proposal 2 explicitly refers

to race and was unquestionably about race. It not

only prohibited constitutionally permissible race

conscious admissions programs but also made it

substantially more onerous for proponents of such

programs to advocate their adoption successfully in

the future, thereby (among other consequences)

reducing the enrollment of underrepresented

minorities on individual campuses. Based on

overwhelming evidence, the Sixth Circuit adopted

the district court’s factual findings that Proposal 2

effected a significant change in the ordinary political

process and that it was fundamentally about race.

Relying on Washington v. Seattle School District

No. 1, 458 U.S. 457 (1982), and Hunter v. Erickson,

393 U.S. 385 (1969), the Sixth Circuit, sitting en

banc, concluded that Proposal 2 was therefore a

racial classification subject to strict scrutiny under

the Equal Protection Clause and, because the state

3

did not advance a compelling governmental interest,

was unconstitutional.

In the context of racial classifications, this Court

has most often applied strict scrutiny when the

government expressly classifies individuals by race

and differentially allocates benefits and burdens

based upon individual membership in a racial or

ethnic group. See, e.g., Fisher v. Univ. of Tex., 133 S.

Ct. 2411 (2013) (reviewing public university

admissions program); Parents Involved in Cmty. Sch.

v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1, 551 U.S. 701 (2007)

(reviewing programs to assign individual students to

particular K-12 public schools); Grutter, 539 U.S. 30G

(2003) (reviewing public law school admissions

program); Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena, 515

U.S. 200 (1995) (reviewing program to award

government contracts).

But this Court also has identified a category of

cases where strict scrutiny applies to governmental

action that does not allocate benefits or burdens

directly to individuals but rather controls how

decisions related to that allocation occur. When race

is “the predominant factor,” Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S.

952, 959 (1996), motivating the manipulation of the

political process, that change in the political process

itself creates a racial classification that is subject to

strict scrutiny. For example, this Court has held

that redistricting decisions are subject to strict

scrutiny when they disregard traditional race-

neutral districting principles and otherwise are

“unexplainable on grounds other than race,” even

when there is no resulting substantive harm to any

individual’s voting strength. Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S.

630, 641-43 (1993); see also Bush, 517 U.S. at 958.

4

Likewise, strict scrutiny applied in Hunter and

Seattle, which this Court subsequently characterized

as “precedents involving discriminatory

restructuring of governmental decisionmaking,”

Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620, 625 (1996), because

the challenged governmental action in those cases

created uniquely onerous political processes for

deciding whether to adopt constitutionally

permissible race-conscious programs.

The narrow application of strict scrutiny beyond

decisions that directly allocate governmental benefits

and burdens reinforces the core rationale supporting

this Court’s conclusion that all racial classifications

must be subject to strict scrutiny: they “delay the

time when race will become a truly irrelevant, or at

least insignificant, factor” in society. Adarand, 515

U.S. at 229. It is, of course, the political process that

determines the allocation of governmental benefits

and burdens, so efforts like Proposal 2 to structure

the political process along overtly racial lines

unmistakably mandate that race be “outcome

determinative,” Grutter, 539 U.S. at 389 (Kennedy,

J., dissenting), in the way government operates and

“threaten[j to carry us further from the goal of a

political system in which race no longer matters—a

goal that the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments

embody, and to which the Nation continues to

aspire,” Shaw, 509 U.S. at 657. The suggestion that

changing the political process along racial lines to

prevent the state from taking constitutionally

permissible race-conscious action is somehow

justified because it may ultimately reduce the

importance of race within society is irreconcilable

with settled doctrine. See, e.g., Parents Involved, 551

5

U.S. at 782 (Kennedy, J., concurring) (“To make race

matter now so that it might not matter later may

entrench the very prejudices we seek to overcome.”).

Because the state plainly has a compelling

interest in prohibiting race-conscious action that

violates the Equal Protection Clause, the political

restructuring doctrine is necessarily implicated only

in the limited circumstances where race-conscious

governmental action is constitutionally permissible.

Under those circumstances, the state must make a

choice whether to take race into account; there is

consequently a need for public discourse regarding

whether or not to adopt such measures. In this case,

for example, Michigan was free to maintain the race

conscious admissions program upheld in Grutter or

to abandon it. See, e.g., Crawford v. Bd. of Educ.,

458 U.S. 527, 539 (1982). Proposal 2, however,

effected far more than a mere repeal of race

conscious legislation. While otherwise leaving intact

the Boards of Regents’ plenary authority over

university affairs, Proposal 2 stripped the Boards’

power only with respect to an inherently racial issue

and entrenched that issue at a higher and more

burdensome level of political decisionmaking.

Although history instructs that the targeted

restructuring of the political process has often been

used, as here, to the disadvantage of racial

minorities, this Court has cautioned that allowing

either side of a debate to manipulate the political

process for making such decisions introduces a racial

divide into the political system. See Shaw, 509 U.S.

at 650-51 (“[E]qual protection analysis is not

dependent on the race of those burdened or

benefited” (internal quotation marks omitted)).

6

Recent empirical analysis demonstrates that racial

polarization was substantially greater in Michigan

on the question of whether to amend the constitution

to prohibit race-conscious admissions programs than

on the more general question of whether affirmative

action programs should be adopted. See generally

Brief of Amici Curiae Political Scientists Donald

Kinder et al. (hereinafter “Kinder Br.”).

The political restructuring doctrine is a

necessary bulwark of equal protection jurisprudence:

it ensures that the debate over whether to adopt

constitutionally permissible race-conscious programs

does not lead to racial balkanization if one side

attempts to racially gerrymander the political

process to rig the outcome in its favor. It also

reflects a clear and narrow rule: when race is the

predominant factor explaining a state’s decision to

establish a distinct political process, the

governmental action creates a racial classification

subject to strict scrutiny. Although courts may be

called upon to determine whether race is the

predominant factor behind the governmental action

and whether the action creates a distinct political

process, those determinations are guided by tests

that are amenable to commonsensical and objective

application.

Accordingly, the Court should affirm the Sixth

Circuit’s conclusion that Proposal 2 was a distortion

of the political process related to constitutionally

permissible race-conscious policies and therefore a

racial classification that is subject to, and fails, strict

scrutiny, especially in light of Petitioner’s failure

even to articulate a compelling state interest.

7

STATEMENT

A. Background

Under its state constitution, Michigan’s public

universities are controlled by independent Boards of

Regents, each of which has the power of “general

supervision of its institution and the control and

direction of all expenditures from the institution’s

funds.” Mich. Const, art. VIII, § 5. Board members

have always enjoyed autonomy over admissions

policies, and they have delegated the responsibility

to establish admissions standards, policies, and

procedures to units within the institutions, including

central admissions offices, schools, and colleges. Pet.

App. 27a-29a; Supp. C.A. Br. of Universities 19-21.

Students, faculty, and other individuals have always

been free to lobby Michigan’s public universities for

or against the adoption of particular admissions

policies. They have histoi'ically done so on numerous

occasions. By the 1990s, for example, in response to

decades of robust, hard-fought political debate,

admissions decisions in many of Michigan’s public

universities’ graduate and undergraduate programs

included consideration of race as one of a multitude

of factors. Supp. Pet. App. 270a-71a.

In 2003, this Court in Grutter, 539 U.S. 306,

upheld as constitutional the University of Michigan

Law School’s holistic, race-conscious admissions

policy. On the same day, the Court invalidated the

admissions policy of the University of Michigan’s

undergraduate college as not narrowly tailored to

serve the State’s compelling interest in obtaining the

educational benefits of student-body diversity. See

Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 244 (2003).

8

Following these decisions, Michigan’s public

universities amended their admissions policies as

needed to comply with Grutter. For instance, the

University of Michigan’s undergraduate admissions

officers crafted a policy that engaged in an

“individualized inquiry into the possible diversity

contributions of all applicants,” Grutter, 539 U.S.

at 341, considering race along with another “50 to 80

different categories,” such as personal interests and

achievements, geographic location, alumni

connections, athletic skills, socioeconomic status,

family educational background, overcoming

obstacles, work experience, and any extraordinary

awards, both inside and outside the classroom, Supp.

Pet. App. 283a-284a.

As Petitioner acknowledges, Pet. Br. 7, in direct

response to this Court’s rulings in Gratz and Grutter,

opponents of race-conscious admissions programs

organized to place a proposal to amend the Michigan

Constitution on the November 2006 statewide ballot.

The initiative, Proposal 2, sought “to amend the

State Constitution to ban affirmative action

programs,” Pet. App. 8a, and its principal author

stated that its purpose was “to prohibit programs

that granted racial preferences, that is, affirmative

action programs,” Supp. Pet. App. 327a. Once

adopted by the voters, Proposal 2 amended the

Michigan Constitution to include the following

provisions, entitled “Affirmative Action,” in Article I:

(1) The University of Michigan, Michigan

State University, Wayne State University,

and any other public college or university,

community college, or school district shall

not discriminate against, or grant

9

preferential treatment to, any individual or

group on the basis of race, sex, color,

ethnicity, or national origin in the operation

of public employment, public education, or

public contracting.

(2) The state shall not discriminate against,

or grant preferential treatment to, any

individual or group on the basis of race, sex,

color, ethnicity, or national origin in the

operation of public employment, public

education, or public contracting.

(3) For the purposes of this section “state”

includes, but is not necessarily limited to,

the state itself, any city, county, any public

college, university, or community college,

school district, or other political subdivision

or governmental instrumentality of or

within the State of Michigan not included in

sub-section 1.

Pet. App. 8a-9a (citing Mich. Const, art. I, § 26). No

prior constitutional amendment in Michigan had

dealt with any matter relating to university

admissions or, for that matter, with anything related

to higher education governance or affairs.

In December 2006, Proposal 2 took effect and

generated two major changes to the admissions

policies at Michigan’s public universities. First,

Proposal 2 mandated that Michigan’s public

universities remove “race, sex, color, ethnicity, or

national origin” as potential factors in the

admissions process even though the Boards and their

designated admissions committees could continue to

10

consider any and all other factors. Pet. App. 9a.

Second, Proposal 2 “entrenched this prohibition at

the state constitutional level, thus preventing public

colleges and universities or their Boards from

revisiting this issue—and only this issue—without

repeal or modification of [Proposal 2].” Pet. App. 9a.

B. Proceedings Below

On November 8, 2006, the day after Proposal 2

was approved, the Coalition to Defend Affirmative

Action, Integration and Immigration Rights and

Fight for Equality By Any Means Necessary

(“Coalition Plaintiffs”) filed suit in the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan.

About a month later, the Michigan Attorney General

filed a motion to intervene as a defendant, which the

court granted. Pet. App. 9a-10a.

On December 19, 2006, the Cantrell Plaintiffs, a

group of students, faculty, and prospective applicants

to Michigan’s public universities, filed a separate

suit in the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Michigan. Pet. App. 10a. The

Cantrell Plaintiffs sought to prohibit Proposal 2's

enforcement only as applied to university

admissions, Pet. App. 10a, on the ground that

Proposal 2 violates the Fourteenth Amendment by

creating a separate and more burdensome

governmental decisionmaking process for

determining whether or not universities may adopt

race-conscious admissions policies that satisfy the

Fourteenth Amendment. The district court

consolidated the two cases in January 2007. See Pet.

App. 109a.

11

In reviewing Michigan law and the historical

record, the district court found that “governance of a

university, including the regulation of admissions

criteria, is part of the political process” and that

“race-conscious admissions programs developed”

through this process “in the first place.” Supp.

Pet. 327a. After discovery and consideration of

expert testimony, the court further found that, in

terms of enrollment numbers, “Proposal 2’s

elimination of affirmative action programs will fall

the heaviest on minorities,” Supp. Pet. App. 316a, a

finding that was borne out after Proposal 2 went into

effect. Brief for Respondents the Regents of the

University of Michigan et al. 23-25.

The district court also found “no question” that

“Proposal 2 makes it more difficult” for proponents of

constitutionally permissible race-conscious programs

to achieve their adoption. Supp. Pet. App. 328a.

Expert testimony established that the process of

amending Michigan’s Constitution is “lengthy,

complex, difficult and expensive,” J.A. 40, and ballot

initiatives in Michigan can cost as much as $15

million, “with $5 million being a practical minimum,”

J.A. 47. Because Michigan requires “signatures from

10% of the total vote cast for all candidates” in the

last gubernatorial election and has a relatively short

window for gathering signatures, the cost of simply

securing enough signatures to place an initiative on

the ballot could approach $1 million. J.A. 44, 47-48.

Nonetheless, the district court denied the

Plaintiffs’ motions for summary judgment and

granted the Attorney General’s motion for summary

judgment, stating that “the political restructuring

effectuated by Proposal 2 does not offend the Equal

12

Protection Clause.” Supp. Pet. App. 330a; see Pet.

App. lla-12a. The district court subsequently

denied the Cantrell Plaintiffs’ motion for

reconsideration, and both Plaintiff groups appealed.

Pet. App. 12a.

On appeal, the Sixth Circuit, sitting en banc,

invalidated Proposal 2. Relying on Seattle and

Hunter, the Sixth Circuit held that a political

enactment denies equal protection when it (1) has a

“racial focus” and (2) “reallocates political power or

reorders the decisionmaking process” in a way that

“places special burdens on racial minorities.” Pet.

App. 21a-22a.

As the Sixth Circuit recognized, it is undisputed

that after Proposal 2, the only recourse available to a

person seeking to restore the constitutionally

permissible consideration of race as one factor in

higher education admissions would be to mount a

successful statewide electoral campaign to amend

the Michigan Constitution, which, as the district

court found, is “an extraordinarily expensive process

and the most arduous of all the possible channels for

change.” Pet. App. 36a. In contrast, a Michigan

citizen lobbying for or against consideration of such

non-racial factors as religious group membership,

legacy status, geographic origin, athletic skill or

virtually any other dimension of experience or

background treated as an identifying characteristic

may use any number of less burdensome avenues to

change or maintain admissions policies. For

example, such a citizen could directly engage in

discourse with the Boards, the appropriate

university committees, or other university officials.

See Pet. App. 35a. The Sixth Circuit also affirmed

13

the district court’s finding that “the admissions

policies affected by Proposal 2 are part of a political

process,” canvassing in detail Michigan law and

relying also on briefing by University defendants

“clarifying] their admissions practices.” Pet.

App. 27a-33a (internal quotation marks omitted).

As the Sixth Circuit explained, “[b]ecause less

onerous avenues to effect political change remain

open to those advocating consideration of nonracial

factors in admissions decisions, Michigan cannot

force those advocating for consideration of racial

factors to traverse a more arduous road without

violating the Fourteenth Amendment.” Pet.

App. 37a-38a. The Sixth Circuit recognized that the

State of Michigan had made no attempt to justify

Proposal 2 by advancing a putative compelling

interest. Pet. App. 45a (“Likewise, because the

Attorney General does not assert that Proposal 2

satisfies a compelling state interest, we need not

consider this argument.”).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This Court has held that all racial classifications

are subject to strict scrutiny. See Fisher, 133 S. Ct.

at 2421. Thus, strict scrutiny applies when the

government classifies “individuals by race” and

differentially “allocate[s] benefits and burdens on

that basis,” Parents Involved, 551 U.S. at 783, 789

(Kennedy, J., concurring). Strict scrutiny also

applies when race is “the predominant factor,” Bush,

517 U.S. at 959, in determining how the political

process is structured because this Court has

recognized that the allocation of government benefits

and burdens cannot be separated from the process by

14

which those political decisions are made. See Bush,

517 U.S. 952; Shaw, 509 U.S. 630; Seattle, 458

U.S. 457; Hunter, 393 U.S. 385. Proposal 2 falls into

this second, narrower category of racial

classifications because it requires a distinct and, as

the district court explicitly found and the Sixth

Circuit affirmed, more onerous process for deciding

whether to adopt constitutionally permissible race

conscious admissions programs than the process that

applies to other decisions related to admissions

criteria.

This Court should affirm the Sixth Circuit’s

decision and decline the invitation by Petitioner and

Russell to overrule the political restructuring

doctrine embodied in Hunter and Seattle, for three

principal reasons:

1. The political restructuring doctrine is

consistent with, and a necessary component of, this

Court’s equal protection jurisprudence.

This Court has long recognized that the

“peculiar and disadvantageous” treatment of racial

matters in the political process is a racial

classification subject to strict scrutiny. See Seattle,

458 U.S. at 485. Like decisions impacting voting

rights and the redistricting of legislative boundaries,

decisions to modify other facets of the political

process directly impact the allocation of

governmental benefits and burdens to individuals.

Applying strict scrutiny to decisions that create

“distinctions based on race,” id.., within our political

system is thus consistent with longstanding doctrine.

15

This Court has also repeatedly explained that

all racial classifications must be subjected to strict

scrutiny because treating race differently may

increase the salience of race in our constitutional

democracy and sanction the view that race remains

outcome determinative in our political processes. See

Shaw, 509 U.S. at 657. These risks are particularly

likely when the classification directly affects the

individual allocation of governmental benefits and

burdens on the basis of race. But they are equally

likely when the political process itself contains a

distinct decisionmaking process for racial issues.

States will always have a compelling interest in

prohibiting race-conscious conduct that violates the

Equal Protection Clause. Changes to the political

process can therefore violate the Fourteenth

Amendment under the political restructuring

doctrine only in the narrow circumstances in which a

state has the choice whether or not to adopt a

constitutionally permissible race-conscious program.

In this context, the political restructuring doctrine

plays an indispensable role by assuring that the

process through which the state resolves that

question does not needlessly heighten the focus on

race as an overly salient or outcome-determinative

feature of our political system.

In Hunter and Seattle, the political process was

manipulated to prohibit constitutionally permissible

race-conscious programs or policies. In decisions

that post-date Hunter and Seattle, this Court has

held that all racial classifications, including those

intended to benefit minorities, are subject to strict

scrutiny. See, e.g., Adarand, 515 U.S. 200.

Application of the political restructuring doctrine

16

does not, therefore, turn on whether the state has

mandated or prohibited constitutionally permissible

race-conscious policies. Rather, this Court’s current

understanding of the Equal Protection Clause

requires strict scrutiny whenever racial issues are

subject to a distinct and more burdensome

decisionmaking process, regardless of outcome.

The political restructuring doctrine thus applies

in narrow circumstances delineated by a clear rule

that enforces this Court’s core equal protection

principles. In the limited context of constitutionally

permissible race-conscious action, when race is the

predominant factor explaining a state’s decision to

establish a distinct political process, the

governmental action creates a racial classification

subject to strict scrutiny. Race is the predominant

factor behind the creation of a distinct

decisionmaking process when, as here, the creation

of the separate decisionmaking process is

“unexplainable on grounds other than race,” see

Shaw, 509 U.S. at 643-44 (quoting Village of

Arlington Heights v. Metro. Hons. Dev. Corp., 429

U.S. 252, 266 (1977), due to the racial character of

the issue subject to the distinct process. When, as

also occurred here, “race” expressly appears on the

face of the political restructuring measure to define

how (or to which types of action) a distinct

decisionmaking process applies and nothing in the

record otherwise dispels the conclusion that its

application to “race” was the predominant factor

behind the measure, the racial character of the issue

is clear. See Hunter, 393 U.S. at 390-91. And a

distinct political process exists when plenary

decisionmaking authority resides at one

17

governmental level, e.g., the Board of Regents, but

the decision whether to take constitutionally

permissible action with respect to race is situated at

a different governmental level, e.g., the state

constitution, in which advocacy is necessarily

substantially more burdensome. By contrast,

decisions to enact (or not enact) or to repeal (or leave

in place) constitutionally permissible race-conscious

legislation or policies are not subject to strict

scrutiny under the political restructuring doctrine

because they do not create a distinct decisionmaking

process.

2. The Sixth Circuit correctly concluded

that Proposal 2 created a racial classification subject

to strict scrutiny. Proposal 2 explicitly established a

distinct political process for race-conscious

admissions programs. Under Proposal 2, the Boards

of Regents retain plenary authority over all other

university matters, including general authority to set

admissions criteria. But the specific decision

whether to adopt constitutionally permissible race-

conscious admissions programs was uprooted from

that locus of political decisionmaking and entrenched

at the state constitutional level. As a direct response

to Grutter and framed by its principal author as

prohibiting consideration of race in college

admissions, Proposal 2 cannot be rationally

explained or understood on grounds other than race.

Both Petitioner and Russell argue that

Proposal 2 should not be subject to strict scrutiny

because many considerations other than intent to

harm minorities might lead a state to prohibit race

conscious college admission programs. But requiring

plaintiffs to prove animus toward a particular racial

18

group as part of an equal protection claim would be

incompatible with decades of this Court’s precedents,

including Shaw, Bush, Adarand, Parents Involved,

and Fisher. The district court and the Sixth Circuit

both found that, in addition to targeting race

explicitly for different treatment, the fundamental

aims of Proposal 2 were to prohibit race-conscious

admissions programs and to create a different and

more burdensome decisionmaking process to block

any future effort to alter that outcome. The

underlying attitudes of voters toward particular

racial groups are irrelevant.

Because the state chose not even to venture to

identify a compelling interest for the racial

classification embodied in Proposal 2, and because

Proposal 2 is not narrowly tailored even if such an

interest were deemed to exist, Proposal 2 is

unconstitutional. Petitioner’s argument that strict

scrutiny should not apply to Proposal 2 because it

seeks ultimately to minimize the salience of race by

prohibiting race-conscious admission programs

cannot be squared with settled Fourteenth

Amendment doctrine. All racial classifications are

subject to strict scrutiny, however laudable a goal

they purport to advance and even if their supporters

believe the racial classification will ultimately reduce

the prominence of race in society.

3. Stare decisis counsels against taking

the dramatic step to overrule or substantially limit

such longstanding precedent as Hunter and Seattle.

The attacks by Petitioner and Russell on the wisdom

of race-conscious admissions programs, which serve

only to catalogue their continuing disagreement with

19

this Court’s holdings in Grutter and Fisher, are

irrelevant to the question presented in this case.

ARGUMENT

I. THE POLITICAL RESTRUCTURING

DOCTRINE IS CONSISTENT WITH, AND A

NECESSARY COMPONENT OF, THIS

COURT’S EQUAL PROTECTION

JURISPRUDENCE.

A. This Court Has Long Recognized That

the “Peculiar and Disadvantageous”

Treatment of Racial Matters in the

Political Process Is a Racial

Classification Subject to Strict

Scrutiny.

More than a quarter century ago, this Court

held that the ordinary political processes of

government decisionmaking may not be intentionally

skewed against particular policies because their

subject matter is racial in nature. Seattle, 458 U.S.

at 470 (holding that strict scrutiny is triggered

whenever “the State allocates governmental power

nonneutrally, by explicitly using the racial nature of

a decision to determine the decisionmaking process”).

In Seattle, blacks and other citizens had achieved

school board approval of a busing plan to lessen the

de facto segregation in Seattle’s schools.1 Opponents

1 The constitutionality of Seattle’s “race-conscious student

assignments for the purpose of achieving integration, even

absent a finding of prior de jure segregation” was not

challenged, so the constitutionality of the plan was assumed.

20

then mounted a successful campaign to pass a

statewide initiative, Initiative 350, prohibiting school

boards from using busing to accomplish racial

integration, while permitting the continued use of

busing for all other purposes of school transportation

and otherwise leaving school governance processes

intact. Initiative 350 “nowhere mention[ed] ‘race’ or

‘integration,’” but it “in fact allow[ed] school districts

to bus their students ‘for most, if not all,’ of the

nonintegrative purposes required by [the state’s]

educational policies.” Id. at 471.

This Court held that Initiative 350 created a

racial classification subject to strict scrutiny:

“ [W]hen the political process or the decisionmaking

mechanism used to address racially conscious

legislation—and only such legislation—is singled out

for peculiar and disadvantageous treatment, the

governmental action plainly rests on distinctions

based on race.” Id. at 485 (internal quotation marks

omitted); see also id. at 480 (“By placing power over

desegregative busing at the state level, then,

Initiative 350 plainly ‘differentiates between the

treatment of problems involving racial matters and

that afforded other problems in the same area.’”

(quoting Lee v. Nyquist, 318 F. Supp. 710, 718

Seattle, 458 U.S. at 472 n.15. Unsurprisingly, Petitioner cites

no authority supporting his contention that this Court’s

decision not to resolve a question that the parties did not raise

undermines the precedent on the issue the Court did resolve.

Cf. Fisher, 133 S. Ct. at 2421 (assuming, for purposes of

decision, that Grutter is good law); id. at 2422 (Scalia, J.,

concurring) (concurring because petitioner did not ask Court to

overturn Grutter).

21

(W.D.N.Y. 1970), aff’d, 403 U.S. 935 (1971))). This

Court thus affirmed that a state could not selectively

gerrymander the political process to impose more

rigorous political burdens on those citizens seeking

to promote constitutionally permissible race

conscious approaches than it imposed on those

pursuing other policy agendas involving public

education. See Seattle, 458 U.S. at 474-75; see also

id. at 474 n.17 (noting that the constitutional evil

was the creation of a “comparative structural

burden” for advocating otherwise constitutionally

permissible race-conscious policies within the

political process).

This Court in Seattle relied on Hunter, 393

U.S. 385, which had articulated the same rule more

than a decade earlier. In Hunter, the Court struck

down an amendment to the City of Akron’s charter

because it explicitly established a process for

deciding racial housing matters that was distinct

from the process for all other housing matters. See

id. at 389. The charter amendment provided that

“(a]ny ordinance enacted by the Council of Akron

which regulates the use, sale, advertising, transfer,

listing assignment, lease, sublease or financing of

real property of any kind or of any interest therein

on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin or

ancestry must first be approved by a majority of the

electors . . . before said ordinance shall be effective.”

Id. at 387 (emphasis added). The requirement of

voter approval for certain ordinances duly enacted by

the city council was unique within the city charter,

applying only to “laws to end housing

discrimination.” Id. at 390; see also id. at 391 (noting

that “[t]he automatic referendum system” did not, for

2 2

example, “affect tenants seeking more heat or better

maintenance from landlords, nor those seeking rent

control, urban renewal, public housing, or new

building codes”). The charter amendment thus

forced those who sought protection from private

racial or religious discrimination to run a “gauntlet”

that those who sought to prevent other abuses in real

estate did not have to run. Id. at 390.

As such, the amendment “was an explicitly

racial classification treating racial housing matters

differently from other . . . housing matters.” Id. at

389; see also id. at 395 (Harlan, J., concurring)

(observing that the amendment was a racial

classification because it was not “grounded in neutral

principle”); Gordon v. Lance, 403 U.S. 1, 5 (1971)

(distinguishing facts of case from Hunter “in which

fair housing legislation alone was subject to an

automatic referendum requirement”). “Because the

core of the Fourteenth Amendment is the prevention

of meaningful and unjustified official distinctions

based on race,” the “racial classification” embodied in

the charter amendment was subject to strict scrutiny

under the Equal Protection Clause. Hunter, 393 U.S.

at 391-93.

This Court thereafter relied on similar

considerations in a series of cases alleging racial

gerrymandering when states created majority-

minority electoral districts in the wake of the 1990

Census. See Bush, 517 U.S. at 958-1002; Shaw, 509

U.S. at 642-58; Easley v. Cromartie, 532 U.S. 234,

241-58 (2001); Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900, 904-

28 (1995). In those cases, the Court held that using

race as the predominant factor in structuring the

political process through electoral district boundaries

23

creates a racial classification subject to strict

scrutiny under the Equal Protection Clause. The

holdings in Shaw and Bush did not rest on the direct

allocation of particular governmental benefits and

burdens based on the race of the individuals seeking

those benefits.2 Rather, the rationale supporting

application of strict scrutiny was the state’s reliance

on race as the predominant factor in drawing

electoral district boundaries and thus in ultimately

structuring the legislative process that is responsible

for allocating governmental benefits and burdens to

individuals.

For example, the plaintiffs in Shaw did not

claim that the challenged reapportionment plan

unconstitutionally diluted white voting strength, or

even that they themselves were white. See 509 U.S.

at 641. Instead, their claim focused on the

application of race as the essential mechanism by

which electoral lines were determined and

government decisionmaking organized: “Racial

gerrymandering, even for remedial purposes, may

balkanize us into competing factions; it threatens to

carry us further from the goal of a political system in

which race no longer matters—a goal that the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments embody, and

to which the nation continues to aspire.” Id. at 657.

2 As Justice Souter observed in Bush, rather than

“addressing any injury to members of a class subjected to

differential treatment, the standard presupposition of an equal

protection violation, Shaw I addressed a putative harm subject

to complaint by any voter objecting to an untoward

consideration of race in the political process.” Bush, 517 U.S.

at 1045 (Souter, J., dissenting).

24

Although the Court reiterated that it “never has held

that race-conscious state decisionmaking is

impermissible in all circumstances,” id. at 642, the

Court concluded in Shaw that the State of North

Carolina’s decision to enact redistricting legislation

that “is so bizarre on its face that it is ‘unexplainable

on grounds other than race’” was subject to strict

scrutiny as a racial classification, id. at 644 (quoting

Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 266).

Likewise, in Bush, the Court relied on Shaw to

apply strict scrutiny to, and ultimately void, a plan

to redraw Texas electoral district lines because the

plaintiffs established that race was “the predominant

factor motivating the legislature’s redistricting

decision.” 517 U.S. at 959, 970-72 (internal

quotation marks and alterations omitted); accord id.

at 996 (Kennedy, J., concurring); id. at 1001

(Thomas, J., concurring). The constitutional vice was

not any resulting substantive harm to any

individual’s voting strength, but rather “the

legislature’s reliance on racial criteria” as the

predominant factor in their redistricting efforts. Id.

at 958. In other words, the Texas redistricting failed

under the Equal Protection Clause because the

“contours” of the lines drawn were “unexplainable in

terms other than race,” id. at 972, and not narrowly

tailored to serve a compelling state interest, see id.

at 976-83. Cf. League of United, Latin Am. Citizens v.

Perry, 548 U.S. 399, 475 & n.12 (2006) (Stevens, J.,

concurring in part and dissenting in part)

(recognizing on behalf of himself and one other

Justice that compliance with the Voting Rights Act

can be a compelling interest in legislative

redistricting); id. at 485 n.2 (Souter, J., concurring in

25

part and dissenting in part) (same, on behalf of

himself and one other Justice); id. at 518-19 (Scalia,

J., concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting

in part) (same, on behalf of himself and three other

Justices).

Notably, the Court in Shaw drew from the same

body of case law addressing attempts to restrict the

political power of minority groups through

manipulations of the machinery of governmental

power upon which the Court relied in Hunter and

Seattle. Compare Shaw, 509 U.S. at 639-41, 644-46

(discussing Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347

(1915), Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960),

Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52 (1964), Reynolds u.

Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964), and Allen u. State Bd. of

Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969)) with Hunter, 393 U.S.

at 391, 393 (citing Gomillion, 364 U.S. 339, Reynolds,

377 U.S. 533, and Avery v. Midland Cnty., 390

U.S. 474 (1968)), and Seattle, 458 U.S. at 485-86

(discussing Hunter’s reliance on voting rights cases).

These cases recognized that, although

government can discriminate directly in the

allocation of benefits and burdens based on the race

of individuals, subtle changes in the political process

can accomplish essentially the same ends because

decisions about the allocation of governmental

benefits and burdens ultimately flow from the

political process. See generally Brief for Amici

Curiae Constitutional and Local Government

Scholars Michelle Wilde Anderson et al. in Support of

the Cantrell Respondents. Gomillion dramatically

illustrates this functional equivalence: the City of

Tuskegee had been “square in shape,” but the law

challenged in that case “transformed it into a

26

strangely irregular twenty-eight-sided figure” that

“deprived the petitioners of the municipal franchise

and consequent rights.” 364 U.S. at 341, 347.

Likewise, in Reynolds, the Court anchored the “one

person, one vote” principle on the importance of

“equal representation” within our country’s

“representative government,” thereby recognizing

that election results dictate governmental decisions.

377 U.S. at 560-61.

In Shaw, the Court relied on the ugly history of

efforts by state and local governments to limit

minority access to the franchise to demonstrate that

the machinery of political power can be corrupted

“through the use of both subtle and blunt

instruments” to limit, along racial lines, the ability of

citizens to influence governmental decisions. 509

U.S. at 639-41 (internal quotation marks omitted).

And in Hunter and Seattle, these historical examples

illustrated an analogous means through which the

political system could be manipulated along racial

lines to affect the allocation of governmental benefits

and burdens to individuals. See Hunter, 393 U.S. at

391 (holding that restructuring the political process

to disadvantage advocates of programs that benefit

minorities “is no more permissible than denying

them the vote, on an equal basis with others”); id. at

392-93 (comparing political restructuring to efforts to

“dilute any person’s vote or give any group a smaller

representation than another of comparable size”);

accord, Seattle, 458 U.S. at 486-87.

The shared reliance on this case law underscores

that Hunter and Seattle, like Shaw and Bush, rest on

the recognition that, because governmental decisions

regarding the allocation of benefits and burdens

27

among individuals flow directly from the political

process, using race as the predominant factor in

restructuring that process is no less suspect than

using race to decide directly which individuals will

receive which benefits or be subject to which burdens

and can be sustained only if narrowly tailored in

support of a compelling state interest. That

conclusion is fully consistent with this Court’s

longstanding principle that “legislation which

restricts those political processes which can

ordinarily be expected to bring about repeal of

undesirable legislation” should “be subjected to more

exacting judicial scrutiny.” United States v. Carotene

Prods. Co., 304 U.S. 144, 152 n.4 (1938) (cited in

Seattle, 458 U.S. at 486). Hunter and Seattle thus fit

within the framework of cases that pay close

attention to devices that preordain the distribution of

benefits and burdens as a function of race.

Unsettling those precedents would erode the

foundations of the entire theory of strictly

scrutinizing racial classifications.

B. Structuring the Political Process

Based on Racial Considerations Is

Particularly Likely To Underscore

That Race Is a Significant and

Outcome-Determinative Factor Within

Our Political System.

The political restructuring doctrine plays an

indispensible role in the limited context where states

must decide whether or not to adopt constitutionally

permissible race-conscious programs by ensuring

that the processes through which states and their

political subdivisions resolve that debate do not

entrench race as a central, outcome-determinative

28

feature of our political system. Failing to apply strict

scrutiny where the political process governing that

debate is transparently restructured around race

would strip equal protection doctrine of any

principled coherence.

This Court has held that all racial classifications

are subject to strict scrutiny because they pose the

risk of lasting harm to our society. See Fisher, 133

S. Ct. at 2421 (holding that “all racial classifications

imposed by government must be analyzed by a

reviewing court under strict scrutiny” (internal

quotation marks omitted)); City of Richmond v. J.A.

Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469, 493-94 (1989) (“ [Ajbsent

searching judicial inquiry . . . , there is simply no

way of determining what classifications are ‘benign’

or Temedial’ and what classifications are in fact

motivated by illegitimate notions of racial inferiority

or simple racial politics.”).

This is true even when the classifications do not

differentially allocate governmental benefits and

burdens among individuals. See Shaw, 509 U.S. at

651 (“[Rjacial classifications receive close scrutiny

even when they may be said to burden or benefit the

races equally.”). And even purportedly benign racial

classifications receive strict scrutiny because they

may “lead to a politics of racial hostility” and

“endorse race-based reasoning,” which contribute to

“an escalation of racial hostility and conflict.”

Parents Involved, 551 U.S. at 746 (plurality opinion)

(internal quotation marks and citations omitted).

The most sincere belief that a racial classification

will reduce racial differences in the long run is

insufficient to avoid the application of strict scrutiny.

Id. at 782 (Kennedy, J., concurring) (“To make race

29

matter now so that it might not matter later may

entrench the very prejudices we seek to overcome.”).3

Of course, strict scrutiny is not triggered merely

because governmental action is taken “with

consciousness of race.” Bush, 517 U.S. at 958; see

also Shaw, 509 U.S. at 642 (“This Court never has

held that race-conscious state decisionmaking is

impermissible in all circumstances.”). Race

conscious action that does “not lead to different

treatment based on a classification that tells each

[person] he or she is to be defined by race” ordinarily

need not satisfy “strict scrutiny to be found

permissible.” Parents Involved, 551 U.S. at 789

(Kennedy, J., concurring).4 Accordingly, the state

may pursue any number of legitimate ends with race

in mind without risking this harm. For example, the

inclusion of race and ethnicity in the federal census,

collection of such data by law enforcement or other

governmental agencies, or the enactment of

3 Applying strict scrutiny, the question is whether the risk

of societal harm from the racial classification is outweighed by

the compelling governmental interest advanced by the narrowly

tailored program. As Grutter demonstrates and Fisher

confirms, the answer to that question may be yes in some

circumstances.

4 For this reason, efforts to promote diversity in K-12

public schools through “strategic site selection of new schools;

drawing attendance zones with general recognition of the

demographics of neighborhoods; allocating resources for special

programs; recruiting students and faculty in a targeted fashion;

and tracking enrollments, performance, and other statistics by

race” do not require strict scrutiny, even though they involve

consciousness of race. Parents Involved, 551 U.S. at 789

(Kennedy, J., concurring).

30

antidiscrimination laws designed to promote equal

treatment by eradicating racial discrimination do not

trigger strict scrutiny because they do not involve the

differential distribution of finite governmental

resources to individuals based on their race or the

redesign along racial lines of the decisionmaking

processes that generate such differential

distribution. See Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. at 916

(“Redistricting legislatures will, for example, almost

always be aware of racial demographics; but it does

not follow that race predominates in the redistricting

process.”). This Court has never suggested that the

mere consideration of racial demographics, much less

the mere utterance of the word “race,” by

governmental actors risks lasting (or indeed any)

harm to society so as to trigger strict scrutiny.

In contrast, the manipulation of the political

process along racial lines, like the use of race at issue

in Shaw and Bush, does trigger strict scrutiny. This

Court has described the ultimate goal of the

Fourteenth Amendment as advancing our society to

a point where race structures neither individual

opportunity nor the governmental decisions that

ordain how such opportunity is allocated, and

premised its decisions on precisely these grounds.

See, e.g., Adarand, 515 U.S. at 229 (“ [I]t will delay

the time when race will become a truly irrelevant, or

at least insignificant, factor.”); Shaw, 509 U.S. at 657

(identifying ultimate goal of Reconstruction

amendments as creating “a political system in which

race no longer matters”). Hunter itself rested on an

understanding that “the core of the Fourteenth

Amendment is the prevention of meaningful and

31

unjustified official distinctions based on race,” 393

U.S. at 391.

The political restructuring doctrine vindicates

that core equal protection principle in the limited

contexts where race-conscious action is

constitutionally permissible by ensuring that the

political process for making that decision is not itself

skewed on the basis of race.5 In such circumstances,

the state has a choice whether or not to take race

conscious action, so there will always be a need for

public discourse regarding the enactment of such

measures. Because ours is a democratic system, this

Court’s recognition that race-conscious action can be

constitutionally permissible necessitates that the

decision whether to take such action must be made

through the political process. Allowing one side of

the debate to selectively change the rules of the

political process along racial lines to make it

substantially more likely that its preferred outcome

will prevail in perpetuity would demonstrate with

inescapable clarity that race remains a uniquely

central feature of our “political system.” Shaw, 509

U.S. 657.

5 Russell observes that the Equal Protection Clause

protects individuals, not groups. Russell Br. at 15-17. Exactly

so. A distinct decisionmaking process makes it more difficult

for one side of the debate over whether to adopt a

constitutionally permissible race-conscious program to advocate

successfully for its position, so a racialized restructuring injures

either the proponents or opponents of the program. As Shaw

recognized, the race of those impacted by conduct that

underscores the importance of race in our political process is

not relevant. See 509 U.S. at 641 (emphasizing plaintiffs did

not “even claim to be white”).

32

On the other hand, states plainly have a

compelling interest in prohibiting racial

classifications that violate equal protection. Any

change to the political process to prohibit

unconstitutional conduct is therefore justified and

cannot cause any societal harm because any

distinction based on race that it would reinforce

merely repeats the Fourteenth Amendment.

Petitioner makes a superficially plausible

observation that it is “curious to say that a law that

bars a state from discriminating on the basis of race

or sex violates the Equal Protection Clause by

discriminating on the basis of race and sex.” Pet

Br. 4. But that completely misses the point. State

actions that discriminate on the basis of race or sex

are substantively unconstitutional absent adequate

justification without regard to the political

restructuring doctrine. Petitioner glaringly leaves

out the language of Proposal 2 that the Cantrell

Respondents challenge: its prohibition on racial

“preferences.” The political restructuring doctrine is

implicated in this case only because Proposal 2 also

prohibits state universities in Michigan from

adopting precisely the kinds of race-conscious

admissions programs that this Court upheld in

Grutter. Indeed, that was its explicit purpose.

Contrary to Petitioner’s assertion, therefore,

Proposal 2 is not a race-neutral enactment designed

to further the goals of the Equal Protection Clause.

Just the opposite. By creating a two-tier system of

political decisionmaking, Proposal 2 needlessly

heightens the salience of race in the political process

and, by so doing, “contributes] to an escalation of

racial hostility and conflict.” Parents Involved, 551

33

U.S. at 746 (plurality opinion) (internal quotation

marks omitted). This concern is far from theoretical.

Empirical analysis of public polling and voting

polarization data demonstrates that Proposal 2

engendered racial polarization that was

unprecedented in Michigan. See generally Kinder

Br. (finding, to a high degree of statistical certainty,

that Proposal 2 caused racial polarization to an

unprecedented degree, whether compared to the

most racially contentious issues of the past several

decades or to the division over the underlying

question of whether affirmative action is desirable

policy).

C. The Political Restructuring Doctrine

Applies to A ll Manipulations of the

Political Process That Cannot Be

Explained on Grounds Other Than

Race.

Because all racial classifications are

constitutionally suspect, see, e.g., Adarand, 515 U.S.

at 227, the political restructuring doctrine focuses on

the manner in which racial issues are resolved

rather than the outcome of that political debate.

Accordingly, had Proposal 2 been written to mandate

permanent race-conscious admissions policies and

embed that admission criterion in the state’s

constitution while otherwise leaving the Boards of

Regents’ plenary authority intact, the measure would

also be subject to strict scrutiny as a suspect

restructuring of the political process along racial

lines. That the group with the deck stacked against

it would have been the one that opposes race

conscious admissions programs would not affect the

application of strict scrutiny (although a different set

34

of interests might lead to a different result in

applying strict scrutiny).

The Court’s observations in Hunter and Seattle

that the programs affected by the restructuring of

the political process “inure[d] primarily to the benefit

of the minority,” Seattle, 458 U.S. at 472, and that

the restructuring thus “place [d] special burden on

racial minorities,” Hunter, 393 U.S. at 391, were

empirically accurate based on the record in each case

and do not limit the political restructuring doctrine’s

application, in light of Croson and Adarand.G

The Akron city council passed a fair housing

ordinance because African-American citizens were

experiencing overt racial discrimination, see Hunter,

393 U.S. at 386, and the Seattle schools experiencing

the most dire crowding and racial isolation were

predominantly located in minority neighborhoods,

see Seattle, 458 U.S. at 464. The Court recognized

the broader benefits of the race-conscious legislation

in these contexts, see id. at 472 (“And it should be

equally clear that white as well as Negro children

benefit from exposure to ethnic and racial diversity

in the classroom.” (internal quotation marks

omitted)), but the record in each case also

demonstrated that members of the racial minority 6

6 Russell makes much of the Court’s observation that

“[t]he majority needs no protection against discrimination,”

Hunter, 393 U.S. at 391 (quoted in Seattle, 458 U.S. at 468).

Russell Br. 19-20. The political restructuring doctrine,

however, does not depend on this observation and applies to all

racial classifications in a straightforward manner.

35

had a distinct interest in whether the race-conscious

legislation was enacted.7

As such, it was unsurprising that the record in

each case reflected the reality that members of

minority groups generally supported and had been

integral to securing the enactment of the policies

affected by the political restructuring. Cf. Carolene

Prods., 304 U.S. at 152 n.4 (holding that changes to

the political process that harm “discrete and insular

minorities” should be of particular concern under the

Equal Protection Clause) (cited in Seattle, 458 U.S.

at 486). The Court nonetheless made clear that

these findings did not rest on an assumption that

racial identity dictates individual beliefs or that the

views held by members of a racial group are

monolithic. See Seattle, 458 U.S. at 472 (stating that

“the proponents of mandatory integration cannot be

classified by race” and “Negroes and whites may be

counted among both the supporters and the

opponents of Initiative 350”); id. (“ [W]e may fairly

assume that members of the racial majority both

favored and benefited from Akron’s fair housing

ordinance [at issue in Hunter].”).

7 Petitioner’s argument that “a Grutter policy” cannot

benefit “all students” while also benefiting “primarily a

minority group,” Pet. Br. 22, is simply wrong, as he plainly

admits by conceding that representation of certain minority

groups increased after universities changed their policies to

comply with Grutter, Pet. Br. 7. In any event, this argument is

beside the point because the political restructuring doctrine

applies to all racial classifications.

36

The Court’s focus in Hunter and Seattle on the

distinct harm to minorities of government action

that, in fact, distinctly affected those minorities does

not vitiate the doctrine articulated in those cases,

just as the recognition in early voting rights cases

that the challenged actions were motivated by the

desire to prevent racial minorities from participating

equally in our political system did not prompt the

Court to revisit or revise these decisions in Shaw and

its progeny. See Shaw, 509 U.S. at 639-41, 644-46

(relying on cases that emerged from our Nation’s

history of pervasive discrimination that uniquely

harmed African-Americans to conclude that the

majority-minority districts at issue were

unconstitutional).

D. The Political Restructuring Doctrine

Entails Straightforward Factual

Inquiries and Is Integral to a Coherent

Equal Protection Doctrine.

The political restructuring doctrine provides a

clear test for determining whether strict scrutiny

applies. When race is the predominant factor

explaining a decision by the state or its political

subdivision to establish a distinct political process,

the governmental action creates a racial

classification subject to strict scrutiny. See, e.g.,

Seattle, 458 U.S. at 485 (“ [W]hen the political process

or the decisionmaking mechanism used to address

racially conscious legislation—and only such

legislation—is singled out for peculiar and

disadvantageous treatment, the governmental action