Mount Vernon City School District Board of Education v. Allen Brief of Respondent-Intervenors

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mount Vernon City School District Board of Education v. Allen Brief of Respondent-Intervenors, 1969. 321de8d8-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/890cc181-236e-49f5-a7f2-3f5b76f1c4d5/mount-vernon-city-school-district-board-of-education-v-allen-brief-of-respondent-intervenors. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

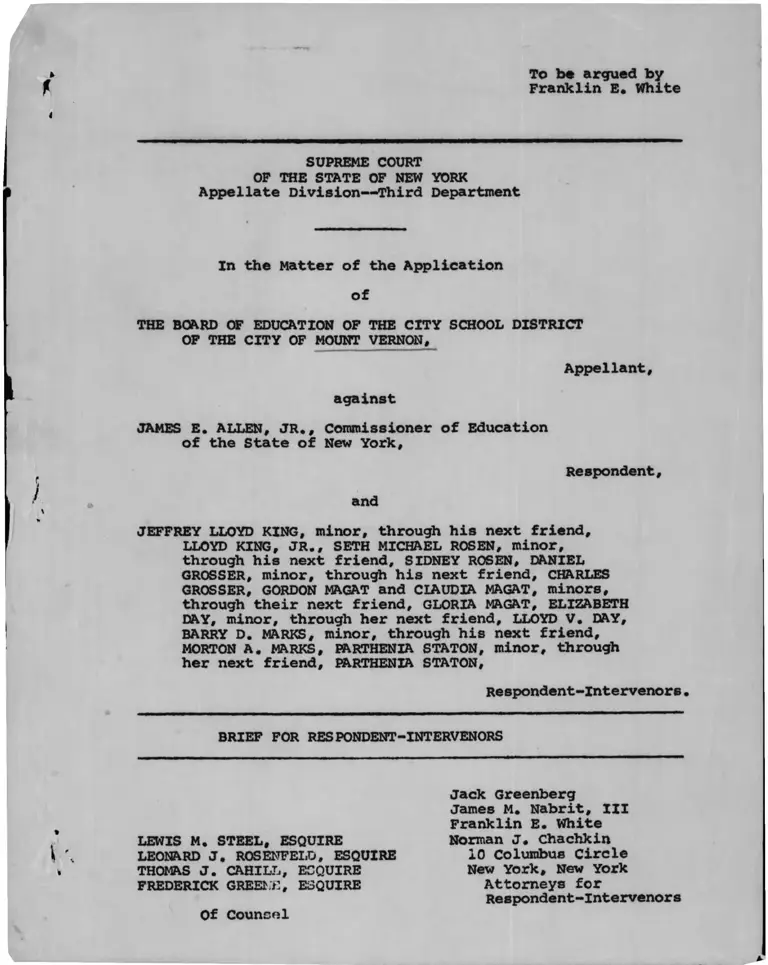

To be argued by

Franklin E. White

SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Appellate Division-Third Department

In the Matter of the Application

of

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT

OF THE CITY OF MOUNT VERNON,

Appellant,

against

JAMES E. ALLEN, JR., Commissioner of Education

of the State of New York,

Respondent,

and

JEFFREY LLOYD KING, minor, through his next friend,

LLOYD KING, JR., SETH MICHAEL ROSEN, minor,

through his next friend, SIDNEY ROSEN, DANIEL GROSSER, minor, through his next friend, CHARLES

GROSSER, GORDON MAGAT and CIAUDIA MAGAT, minors,

through their next friend, GLORIA MAGAT, ELIZABETH

DAY, minor, through her next friend, LLOYD V. DAY,

BARRY D. MARKS, minor, through his next friend,

MORTON A. MARKS, PARTHENIA STATON, minor, through

her next friend, PARTHENIA STATON,

Respondent-intervenorB•

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT-INTERVENORS

LEWIS M. STEEL, ESQUIRE

LEONARD J. ROSENFEI.O, ESQUIRE

THOMAS J. CAHILL, ESQUIRE

FREDERICK GREEK*:, ESQUIRE

Jack Greenberg James M. Nabrit, III

Franklin E. White

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Respondent-lntervenors

Of Counsel

TART.K OF CONTENTS

STATEMENT..............................

COUNTER STATEMENT OF QUESTION PRESENTED

ARGUMENT

I. The Commissioner of Education

may require action to alleviate

racial imbalance on the basis of its educationally beneficial

effects......................

II. The Record Conclusively Shows

That Appellant Is Financially

Able to Implement The Commissioner's Order.....

III. The May 2, 1969 Amendment IsUnconstitutional On its Face..

CONCLUSION

PAGE

1

1

1

10

18

21

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE 22

Statement

Respondent-Intervenors are satisfied with the state

ment of the case and of the facts already related by the

Commissioner in his brief.

Counter Statement of Question Presented

Whether the absence of alleged facts which could be

resolved in petitioner-appellants' favor, or which, if

proven, would demonstrate that the Commissioner's order

was "purely arbitrary," warranted dismissal of the petition.

The Court below answered in the affirmative.

Argument

1. The Commissioner of Education may require

action to alleviate racial imbalance on

the basis of its educationally beneficial

effects.

Respondent-Intervenors Negro and white minors have,

since 1963, sought to enjoy their statutory and

constitutional rights to equal educational opportunities

in the Mount Vernon Public Schools. Five years later,

these rights have been and continue to be denied because

of the deep-seated intransigence of the appellants.

The Commissioner's order of June 13, 1968, is now

attacked by appellant as one dealing solely with race and

having "no comitant educational benefit" (Appellant's

F

Brief, p.21). It argues:

the consideration of race as a factor in establishing or altering educational

practices and procedures is permissible

only where such actions are combined with

legitimate educational purposes, i.e.,

where they are educational rather than

purely racial. (Id. at 22)

But appellant has missed the point. The Board of Regents

has directed that racial imbalance in schools be eliminated

NOT for race itself, but because of the educational

advantages to be gained thereby:

Schools enrolling students largely on

homogenous ethnic origins may damage

the personality of minority group

children. Such schools decrease their

motivation and thus impair the ability

to learn (Policy Statement, January

28, 1960).

The foreword to the most recent policies, "Integration

and the Schools, issued January 1968," states:

Equality of educational opportunity

is being denied to large numbers of

boys and girls — white as well as

Negro and other minority group

children — because of racially

segregated schools.

In that report the Regents state:

Educational considerations are primary

in eliminating school segregation.

The elimination of racial imbalance is

not to be sought as an end in itself but because it stands as a deterrent

and handicap to the improvement of

education for all. ^Emphasis added—/

(Id. at p.12).

2

Appellant is mistaken, therefore, in characterizing the

reason for the Commissioner's order as race and race alone.

Nor do the cases support appellant's argument, in

some,other benefits unrelated to race accrued from programs

eliminating racial imbalance. But those benefits were

merely incidental. The overriding and compelling purpose

of the challenged plans was to eliminate racial imbalance.

See e.g., Matter of Vetere v. Mitchell, 21 A.D. 2d 561,

251 N.Y.S. 2d 480, 483 (3rd Dpt. 1964), aff'd sub nom.

Vetere v. Allen, 15 N.Y. 2d 259, 258 N.Y.S. 2d 77, cert.

denied, 382 U.S. 825 (1965), supra, Steinberg v. Donovan,

45 Misc. 2d 432, 257 N.Y.S. 2d 306 (1965); Van Blerkom

v. Donovan. 15 N.Y. 2d 399 N.Y.S. 2d 825 (1965); Schrepp v.

Donovan, 45 Misc. 2d 917, 252 N.Y.S. 2d 543 (1964). As

the Court stated in Katalinic v. City of Syracuse, 44 Misc.

2d 734, 254 N.Y.S. 2d 970 (Sup. Ct. 1964):

even if the court were convinced, that

the sole purpose /. of the plan_J was

for the correction of a situation of

racial imbalance . . . the court would

be of the opinion that at this time it

has no power to hold that said action

would be arbitrary and capricious or a

constitutional violation.

While appellant has not openly stated it, we believe

it seeks really to contest the findings of the Board of

Regents that racial^ segregation in schools impedes the

furnishing of equal educational opportunities to all students

- 3 -

As this Court well knows this judgment had its genesis in

the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483, 494 (1954) which established the basic principle that

racial segregation in public schools denies Negro children

the opportunity to achieve the full benefits of the

1/

educational process.

Nor does it matter whether the segregation is state-

imposed or a consequence of residential patterns. Thus

California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Wisconsin,

as New York, have taken the position in executive or judicial

statements, that racial isolation in the schools has a

damaging effect on the educational opportunities of Negro

pupils. See <5.£., Jackson v. Pasedena City School District,

59 Cal. 2d 876, 31 Cal. Rep. 606, 382 P 2d 878, 888 (1963);

Kiernan Report, Mass. State Board of Education, April 1965;

Pa. Human Relations Comm., "Guidelines for Fuller

Integration of Elementary and Secondary Schools, July 17,

1964; Policy Statement of Conn. State Board of Education,

Concerning Quality Education for Minority Groups, Dec.

7, 1966; Statement by Wisconsin State Superintendent of

Public Instruction," Department Policy Statement on

De Facto Segregation and Disadvantaged conditions# March

1/ Said the Court:

"Segregation of white and colored children

in public schools has a detrimental effect

on colored children (347 U.S.494)

4

1966; See also U.S. Civil Rights Commission Report,

Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, 1967, 228-236.

It is settled that state Educational authorities are

free to take affirmative action to eliminate de. facto

segregation because of its educationally harmful effects.

See, e.g,. # Matter of Vetere v. Mitchell, supra,; Strippoli

v. Bickal, 21 A.D. 2d 365, 250 N.Y.S. 2d 969 (1964);

Matter of Balaban v. Rubin, 20 A.D. 2d 438, 248 N.Y.S. 2d

574, aff'd. 14 N.Y. 2d 193, 250 N.Y.S. 2d 281 (1964);

Addabbo v. Donovan, 22 App.Div. 2d 383, 256 N.Y.S. 2d 178

(2nd Dpt. 1965), aff'd 16 N.Y.2d 619, 261 N.Y.S. 2d 68,

cert, denied 382 U.S. 905 (1965); Morean v. Board of Education

of Montclair, 42 N.J. 237, 200 A.2d 97 (1964); Fuller v. Volk

230 F. Supp. 25 (1964).

integrated public education, as one of many educational

goals, necessitates a balancing of interests. Appellant

herein is concerned with modification of the neighborhood

school concept. As the Court stated in Jackson v. Pasadenja

City School District;

The interest of Negro child in an

integrated education might outweigh

the district's interest in maintaining

neighborhood schools. 382 P.2d at 881.

The result of tenacious adherence to the concept of

neighborhood schools was clearly perceived by Judge Skelly

Wright in Hobson v. Hansen:

5

It would be wrong to ignore or belittle

the real social values which neighborhood

schools doubtlessly promote. But due

appreciation of these values must not

obscure the fact that the price society

pays for neighborhood schools in Washington

and other urban centers is in racially

segregated public education. 269 F.Supp at 504.

Numerous New York decisions have held that implementation

of plans to eliminate racial imbalance constituted no

violation of the neighborhood school concept. See, e,.£. #

Balaban v. Rubin, 20 A.D. 2d 438, 248 N.Y.S. 2d 574, aff'd

14 N.Y. 2d 193, 250 N.Y.S. 2d 281 (1964), Addabbo v. Donovan,

22 App. Div. 2d 383, 256 N.Y.S. 2d 178, aff'd 16 N.Y. 2d 619,

261 N.Y.S. 2d 68 (1965), Van Blerkom v. Donovan, 15 N.Y. 2d

399, 259 N.Y.S. 2d 825 (1965).

Appellant urges further that the Commissioner's order

is arbitrary and capricious because its implementation will

require the busing of large numbers of children across the

district. But despite the Board's impassioned language

("a waste of valuable hours intransit" (p.13) ) the city

is so small (four miles square R.33) that bus trips will be

a matter of minutes. In any event, busing plans have been

upheld as a valid method of eliminating racial imbalance in a

number of cases both in New York and elsewhere. See, e.g.,

Addabbo v. Donovan, 22 App. Div. 2d 383, 256 N.Y.S. 2d 178

(2nd Dpt. 1965) aff'd, 16 N.Y. 2d 619, 261 N.Y.S. 2d 68,

cert, denied 382 U.S. 905; Strippoli v. Bickal, 21 App. Div.

2d 365, 250, N.Y.S. 2d 969 (4th Dpt. 1964), aff'd without

6 —

opinion 16 N.Y. 2d 652 261 N.Y.S. 2d 84 (1965), Vetere v.

Allen, 41 Misc. 2d 200 rev’d 21 A.D. 2d 561, aff'd 15 N.Y.

2d 259 cert, den., 382 U.S. 825 (1965); Guida v. Board of

Education of New Haven 26 Conn. Supp. 121, 213 A 2d 843 (1965);

School Committee of Boston v. Board of Education,(Mass)

227 N.E. 2d 729 (1967); Hobson v. Hanson, 269 F.Supp. 401

(D.C. D.C. 1967); Penn. Human Relations Comm, v. Chester

School District, 427 Pa. 157, 233 A. 2d 290 (1967); United

States v. School District 151 of Cook County,___ F 2d ____

(7th Cir. 1968). The important consideration in evaluating

the Commissioner's order is not that busing is required, but

that some new method of eliminating racial imbalance was

necessary since the board's plan (open enrollment) has failed

2/to reach the desired result. As the Court in Hobson v. Hansel

supra, faced with the same situation, stated:

"The Board's open transfer policy

. . . is unacceptably meagre. The

transfer right which places the

burden of arranging and financing

transportation on the elementary

school children is, particularly

for the poor, a sterile right, one

in form only." 269 F.Supp. at 499

Appellant urges that the Commissioner's order is

arbitrary because it substitutes his judgment for that of a

2/ Such integration as there is in white schools on the

North side is due to open enrollment. A vote to continue

the program for the 1969-70 school year has failed to pass,

and as of this moment, there is no assurance that any

Negro children will be in those schools this fall.

7

local board. But nothing in the cases or statutes suggests

that the power of the Board of Regents to determine the

educational policies of the state, or of the Commissioner to

implement those policies, are diminished when particular

policies are opposed by a local board. Indeed in Board of

Education of the City of New York v. Allen, 6 N.Y. 2d 127,

188 N.Y.S. 515 (1959) the Court of Appeals sustained the

Commissioner's decision in the face of an attack by the local

board. And in Vetere v. Allen, supra, the court stated that

the Commissioner "could substitute his judgment for that of

the local board, even where the action of the local board

was not arbitrary." 15 N.Y. 2d at 267. Cf. Board of Education

of the City of New York v. Allen, supra, at 6 N.Y. 2d 140, 141

("The Commissioner was free to overrule the use of the . . .

method /_ selected by the local board__/ without having to

find that it was totally unreasonable.").

In any event the local board — elected by a majority of

the community — feels under an obligation to represent what

it deems to be the desires of its constitutents. But policies

and practice in conflict with the public policy of the state

may not be maintained simply because they are preferred by a

locality or by its school board. Thus, southern school boards

are not permitted to maintain dual public school systems, see

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 349 U.S. 294, or

to use plans not promising effectively to dismantle such

8

systems, because they believe them to be the most

suited for their particular community. See Green v.

County School Board of New Kent Ccvnty _Va«j. 391 u*s-

430 (1968), invalidating free choice plans of desegration

utilized by the overwhelming majority of southern

boards.

Unless the Commissioner ultimately has the power

to direct that a particular assignment plan be used,

he might in a particular case be unable to carry out

his statutory duty to "execute the policies" of the

Board of Regents. Recalcitrant boards, such as petitioner,

would forever be able to shirk their constitutional

duty of providing to all their children equal educational

opportunities in a system free of racial imbalance. The

Legislature was well aware of the problem of enforcement.

For in section 311(4) of the Education Law it granted

to the Commissioner the power "to make all orders which

may, in his judgment, be proper or necessary to give

effect to his decision. (Emphasis added)." This section

in our view is ample justification for the Commissioner s

formulation of a particular plan wherever he feels such

action is warranted by the circumstances.

- 9 -

II.

The Record Conclusively Shows

That Appellant Is Financially

Able To implement The Commissioner1s

Order

Just as if we had not responded to this argument below,

appellant just as vigorously pursues it here. And, incredibly

it does so without even acknowledging or attempting to deal with

the serious shortcomings in their argument to which we previously

adverted. The plain fact is that appellant insists on using the

entire cost of the BEST Plan when the Commissioner ordered merely

one feature pairing.

Appellant alleges that the June 13th order of the Commissioner

was arbitrary and capricious because "implementation of the plan

(presumably Allen's plan) was financially impossible"; attached

to the petition is an affidavit of John F. Blank, Clerk of the

Board of Education in which he states that implementation is

financially impossible (R. 44-45). More recently, appellant has

submitted a letter dated November 18, 1968, from Lipsitz and Nadler,

Certified Public Accountants, in support of that contention.

At the outset this Court must assume that the Commissioner

would not have directed implementation of the plan without ample

basis for believing that the district could implement it. His

decision indicates his awareness of its financial implications:

10

I am of course mindful that the steps contemplated

by this decision, both with respect to the elimination

of racial imbalance and with respect to improvement

and innovation in the educational programs of the

school system, will require the expenditure of funds

not presently budgeted by the school district. It

should be noted in this connection that in addition

to other provisions for State aid available to the

district, including transportation aid, the recently

enacted program of special aid for urban school districts having a heavy concentration of pupils with

special educational needs associated with poverty will provide an allocation to the Mount Vernon district

of substantial funds for locally administered program

for such pupils, in accordance with regulations

promulgated by the Commissioner of Education.

It should also be noted that special financial

assistance is available to school districts, such as

Mount Vernon for programs designed to correct racial

imbalance. Careful consideration will of course be

given to any proposal which may be submitted by the

respondent district for the allocation of such assistance in connection with programs developed m

accordance with this decision (R. 4).

Beyond that, however, the allegation is insufficient for two

reasons:

a. it is conclusory and the supporting affidavits and

attachments grossly overstate the cost of implemen

tation ; and

b. proof of financial inability, not having been

presented to the Commissioner, may not be considered

by this Court. The Commissioner, moreover, is still

free to vacate his own order on a finding of

impossibility.

11

a. Appellant's Estimate Is Overstated Since It

includes Costs For Items Not Ordered By The

Commissioner

Appellant argues in its brief that it is "totally unable"

to undertake implementation of the Commissioner's order and that

implementation of the proposed plan of the

Black Community planning Board, which the

Commissioner, in effect, has done, will

speed immediate and irrevocable social,

financial and educational disaster for the

City of Mount Vernon [Brief, p. 13].

But the underscored language points up appellant's error. The

Commissioner never ordered that the BEST Plan be implemented.

He ordered merely that the elementary schools be paired. That

was coincidentally one of the features of both the BEST Plan and

the Dodson Report. As we show later there were other features

of the BEST Plan not ordered by the Commissioner.

Appellant also states that:

Respondents own task force came to the same conclusions as the Lipsitz and Nadler analysis

. . . Nevertheless, respondent apparently

chose to disregard the findings of his own task

force (id at 15) ;

and that

In his opinion the Commissioner stated: (R. 70-71):

I therefore direct that as early as possible in

the school year commencing in September 1968,

but in any event not later than November 4, 1968,

the Board of Education provides for full integration in grades one through six by assigning

all pupils in grades one through three to

existing elementary schools in either the north

or south half of the district, and all pupils in

grades four through six to schools in the other

half of the district.

The only other order was that quarterly reports be filed

commencing September 1, 1968.

- 12

Again, nothing could be further from the truth.

In the first place — and as appellant well knows — the

task force made no single recommendation since its members were

2/ .unable to agree. Some members favored the Board's plan with

modifications, others favored the BEST Plan with modifications.

It was decided instead to make both proposals to the Commissioner

leaving to him the decision of which alternative to choose (R. 78).

To be sure all members of the task force agreed that the

entire BEST Plan was financially impossible (R. 76). Besides

pairing the schools, the BEST Plan would have required the hiring of

additional teachers, teacher aids, social workers and the addition

of more classrooms (R. 75, 77-78). But it was the cost of

implementing this entire plan that was deemed to be beyond the

financial means of the district. Contrary to appellant's

assertion the task force never reported that the pairing feature

was financially impossible.

Lipsitz and Nadler estimate the cost of implementing the

Commissioner's order to be $2,888,543 and $3,344,913 for the

first and second years respectively (R. 97-103). But, as is

evident from their computations and from the erroneous assumption

in appellant's brief, these estimates are for implementing the3/

entire BEST Plan. They, therefore, may be disregarded.

2/

3/

The entire Task Force Report is included in the record

as Exhibit B annexed to the affidavit of Louis H. J. Welch,

at pp. 73-95.

It should not go unnoticed that neither in its brief or

at the oral argument did appellant attempt an explanation

of why it purposely priced a plan not ordered by the

Commissioner.

13

Indeed Lipsitz and Nadler's letter and the report of the

task force show unequivocally that the district ^s financially

capable of implementing the pairing order. The only^additional

cost that the pairing would entail was transportation and

conceivably the cost of providing hot lunches at each school.

(See cost estimate included in Report of Task Force.) Appellant's

own accountants state that "there is available to the City School

District additional funds amounting to $439,136 for the current

school year over and above the amount which it has budgeted."

(R. 98). They estimate, at p. 4, that $636,299 of the district's

own money will be available during the second year (R. 100). Yet

transportation, the only mandated additional cost, is only

$193,00 the first year (R. 85) and, using appellant's own figures,

$105,140 the second year (R. 85, 99). Thus, the district clearly

has enough funds to achieve the pairing ordered. Moreover, even

if hot lunches would now have to be available at each school that

could still be done out of the $439,136 and $636,299 available

since the annual expenditure for lunch would be only $155,000 and

$148,800 during the first and second years (R. 86). (Report of

Task Force).

We are aware that transportation would not be required

by State law. Nonetheless appellees-intervenors desire

transportation and apparently the Board is willing to

provide it if forced to comply. The Commissioner adverted

to it in his order and it was one of the factors considered by the task force. We will, therefore, treat the furnishing

of transportation as a necessary result of the pairing

ordered.

- 14

The following table

anticipated expenses for

summarizes the funds available and

the first two years:

First Year Second Year

Available $439,136 $636,299

Expenses: 6/

Transportation 193,000 105,150

Amortization-Lunchrooms 155,000 148,800

Total Expenses $348,000 $253,950

This analysis reveals the wisdom rather than arbitrariness

of the Commissioner's action for which he should be praised

rather than criticized. While he recognized the value of the

other recommendations contained in the BEST Plan, he knew also,

as he was told by the task force, that implementation of the plan

in its entirety was not possible. A part of his task force

recommended the BEST Plan with modifications. They concluded

that while full integration by pairing was presently financially

feasible most of its features were not (Memorandum of Johnson to

5/ These figures suggest merely what is possible: that the

district by taxing at its constitutional limit can raise

enough funds to meet the modest expenses caused by the

order. But there is little likelihood that it will have

to do so. The Commissioner plainly informed the district

of the several sources of State aid available to it that

it is not now receiving (p. 6, supra). in addition there

are numerous other federal programs under which appellant

may receive funds. While we could catalogue such programs

we think it hardly necessary to do so since the amount

needed is small and the district can probably raise a

substantial portion from the State.

6/ Although the task force estimated only $61,000 for the

second year (R. 85), Lipsitz and Nadler concludes that the

true figure was understated by $45,150 (R. 99).

15

Nyquist, R. 74 et seq.). Heeding their advice he decided to

order pairing only and to suggest to the Board that it continue

its efforts in other areas.

In sum, the short answer to appellant1s allegation of

financial inability is that the allegation is unsupported by the

record or by the affidavits filed in this court, and, indeed, that

the record conclusively shows that appellant is financially able

to implement the Commissioner's order.

Not content with having misrepresented the cost of what the

Commissioner ordered, appellant now argues that the lower court

conceded that there was a "dispute," was obliged to deny the

motions to dismiss. To be sure there was a "dispute," but it was

8/plainly resolvable on the record, that being the case the Court

was entitled to ignore the allegation and grant the motion.

7/ The memorandum pointed to precisely what the Commission

ultimately did (R. 76):

Everyone realized that the BEST Plan is not

feasible financially even if there were agreement

on its desirability. . . . Some members, however,

favored implementing the pairing feature even

though the augmented staff and other instructional

improvements cannot be adopted because of financial reasons (Emphasis added).

8/ Appellant mistakenly assumed they were entitled to a de

novo review of the Commissioner's order in the lower court.

But the proceeding before the Commissioner was quasi

judicial Vetere v. Allen, 15 NY 2d 259, 258 NYS 2d 77; City

of Albany v. McMorron, 34 Misc. 2d 316, 230 N.Y.S. 2d 434

(1962)',' Hecht v. Monaghan, 307 NY 461 (1954). Thus, review

is in the nature of certiorari and the reviewing court is

limited, on the merits of the action taken, to the record

before the Commissioner. Miller, etc, v. Kling, 291 NY

65, 69 (1943); Newbrand v. Yonkers, £85 NY 164, 177-8 (1941);

Schiletti v. Sheridan, 12 App. Div. 2d 801, 210 NYS 2d 20

(ind Depart. 1961); Brody's Auto Wrecking Inc. v. O'Connell,

311 Misc. 2d 466, 220 N.Y.S.2d 936 (1961).

16

b. The Lipsitz and Nadler Letter Should Be

Disregarded

Even if appellant had not grossly overstated the cost of

implementing the Commissioner's order, appellee-intervenors believe

the petition should still be dismissed. The letter of Lipsitz

and Nadler is not a part of the record and was never submitted to

the Commissioner, indeed, although appellant sought rehearing

after the commencement of this action the letter was not submitted

at that time. This court may not rely on financial analyses and

conclusions not furnished the Commissioner, cf. Application of

Kuhn. 145 N.Y.S. 2d 879, "The court may [in an Article 78

Proceeding] consider only such evidence as was presented to the

Commissioner." This is not unimportant for the Commissioner has

traditionally concerned himself with the ability of a district

to implement his orders. Thus, in this very case, when appellant's

Children's Academy plan proved financially unworkable, the

Commissioner by letter dated November 6, 1967 (appellant's Exhibit

H) granted permission to develop another plan. Here, appellant

would have this Court overturn the Commissioner's order for

arbitrariness on data, analyses, and conclusions not presented

to him.

17

Ill

The May 2, 1969 Amendment Is

Unconstitutional On Its Face

Appellee-intervenors respectfully direct this Court's

attention to Chapter 342, Laws of 1969, passed by the New York

State Legislature May 2, 1969 and subsequently signed by the

Governor of New York, (A fascimile reproduction of the Act is

appended hereto as Exhibit "A",) The Act by its terms purports to

divest the Commissioner after August 31, 1969 of any authority to

require compliance by the Mount Vernon Board of Education with the

outstanding order of June 13, 1968,

As a technical matter the Act need not affect this appeal

since it does not become effective until September 1, 1969. Beyond

that, however, we submit that it is so clearly unconstitutional

that this court can so find and accordingly affirm the judgment

below. Should the court be reluctant to pass upon its

constitutionality now it can ignore the statute because of its

effective date and rule on the merits. In the alternative, it

could remad the case to Special Term for a determination of its

constitutionality before ruling on ther merits.

In Matter of Vetere v. Mitchell, 21 A.D. 2d 561, 251 N.Y.S. 2d

480, 483 (3d Dpt. 1964), aff*d sub nom. Vetere v. Allen, 15 N.Y.

2d 259, 258 N.Y.S. 2d 77, 206 N.E. 2d 174, cert, denied. 382 U.S.

825 (1965), this Court stated that if the guarantee of nondiscrimi-

9/nation contained in §3201 of the Education Law were construed to

9/ Retained in very slightly modified form in the 1969 Act

which amends §3201. See Exhibit "A."

- 18

prevent implementation of an order issued by the Commissioner of

Education requiring school pairings to overcome racial imbalance,

the statute would be unconstitutional for the reason that it would

actively preserve racial imbalance by force of law. The statute,

said the Court, would thereby convert de facto segregation into de

jure segregation.

The new law stands on no firmer a constitutional footing. The

fact that it may, in some instances, at the option of local elective

school boards, not perpetuate segregation does not save its

constitutionality. Cf. Griffin v. County School Bd. of prince

Edward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) (striking down a Virginia law

which permitted a local county school district to close down its

schools to avoid integration). Constitutional rights "may not be

submitted to vote; they depend upon the outcome of no elections."

West Virginia State Bd, of Educ, v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624, 638

(1943).

A separate and equally egregious defect of the measure is that

it accomplishes a significant involvement of the State of New York

in private discrimination. The new law grafts onto the prohibition

of racial attendance policies in New York public schools an

exception providing that a child may be racially assigned if such

10/is the wish of his parent or guardian. Compare Reitman v. Mulkey,

387 U.S. 369 (1967), striking down a constitutional amendment

guaranteeing the right to refuse to sell property to any person

(even on grounds of racial discrimination) enacted by referendum

against a background of statutotry prohibitions of racial

10/ The "right" of the child, parent or guardian to select the

school he shall attend rather than remaining subject to assign

ment is entirely new to New York law. Education Law §§2556,

2503(4)(d).

19

discrimination.

Similarly, examination of the law "in terms of its 'immediate

objective,' its 'ultimate effect' and its 'historical context and

the conditions existing prior to its enactment,'" Reitman v.

Mulkey, 387 U.S. at 373, reveals the discriminatory purpose of the

legislation. The history of local resistance to orders of the

Commissioner which require the elimination of segregated public

schools is well documented. E.£., Vetere v. Allen, 41 Misc. 2d 200,

245 N.Y.S. 2d 682 (Sup. Ct. Albany Co. 1963), rev'd sub nom,

Vetere v. Mitchell, 21 A.D. 2d 561, 251 N.Y.S. 2d 480 (3d Dept 1964),

aff'd sub nom. Vetere v. Allen, 15 N.Y. 2d 259, 258 N.Y.S. 2d 77,

206 N.E. 2d 174, cert, denied, 382 U.S. 825 (1965); Addabo v.

Donovan. 22 A.D. 2d 383, 256, N.Y.S. 2d 178 (2d Dept.), aff^d 16

N.Y. 2d 619, 261 N.Y.S. 2d 68, 209 N.E. 2d 112, cert., denied, 382

U.S. 905 (1965): Balaban v. Rubin, 20 A.D. 2d 438, 248 N.Y.S. 2d

574 (2d Dept.), aff'd 14 N.Y. 2d 193, 250 N.Y.S. 2d 281, 199 N.E. 2d

375, cert, denied, 379 U.S. 881 (1964). The very tortured history

of this case — five years' time during which the Mount Vernon

Board of Education failed to develop a plan which would adequately

redress the segregation of its school system — demonstrates such

resistance to be present here. There can be little doubt that the

design, intent and effect of the new law is to reverse the

Commissioner's rulings and to provide encouragement and solace to

parents who desire to maintain segregated attendance patterns.

Finally, we would reemphasize, that respondents are entitled

to an adjudication of the constitutionality of this statute before

it affects their case. Such a course is entirely consistent with

- 20

» sound judicial practice. This court may not, therefore, reverse

the judgment below relying upon the statute. As we have

demonstrated the statute is defective on its face and should be

ignored. In the alternative the case should be remanded for

Special Term so that its constitutionality may thereupon be

adjudicated.

I

CONCLUSION

For all the above reasons the judgment below should be

affirmed.

Respectfully submitted.

\ JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

FRANKLIN E. WHITE

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN 10 Columbus Circle New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondents-

Intervenors

LEWIS M. STEEL, ESQUIRE

LEONARD J. ROSENFELD, ESQUIRE

THOMAS J. CAHILL, ESQUIRE

FREDERICK GREENE, ESQUIRE

Of Counsel

- 21 -

*V