Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board Reply Brief and Brief as Cross-Appellee

Public Court Documents

May 20, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board Reply Brief and Brief as Cross-Appellee, 1983. db0d0228-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/892424ab-555c-4365-bbaa-d599b3ac5b4f/davis-v-east-baton-rouge-parish-school-board-reply-brief-and-brief-as-cross-appellee. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

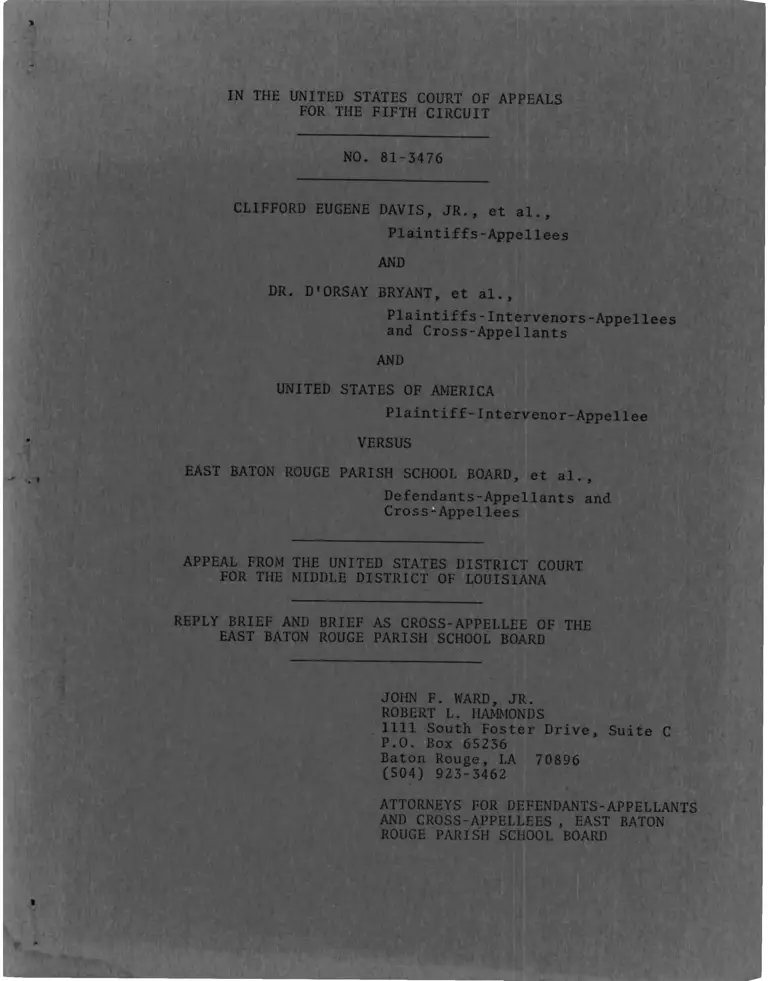

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 81-3476

CLIFFORD EUGENE DAVIS, JR., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

AND

DR. D'ORSAY BRYANT, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellees

and Cross-Appellants

AND

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellee

VERSUS

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants and

Cross-Appellees

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

REPLY BRIEF AND BRIEF AS CROSS-APPELLEE OF THE

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD

JOHN F. WARD, JR.

ROBERT L. HAMMONDS

1111 South Foster Drive, Suite CP.O. Box 65236

Baton Rouge, LA 70896

(504) 923-3462

ATTORNEYS FOR DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS AND CROSS-APPELLEES , EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

STATEMENT WITH REGARD TO ORAL ARGUMENT (i)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (ii)

QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 2

(i) Course of Proceedings and Disposition

in Court Below 2

(ii) Statement of Facts 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT 15

ARGUMENT 19

I. The District Court erred in not giving the

local school authorities an opportunity to

try their preferred magnet school concept

plan, or, at the very least, in not pointing

out the deficiencies in that plan and giving

the local school authorities an opportunity

to correct same before imposing its own plan

which was clearly based on an impermissible

racial balancing standard 19

II. The position of plaintiff-intervenors-

appellants 31

CONCLUSION 35

CERTIFICATE 56

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Defendant -appel

Parish School Board

these appeals are of

system, this communi

circuit as to make o

lant-cross-appellee, East Baton Rouge

believes that the issues presented in

sufficient importance to this school

ty, and other communities within this

ral argument useful and desirable.

(i)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGE

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of

Education, 396 U.S. 19, 90 S.Ct.

29, 2 4 L i'Ed. 2d 19 (1969)...................... 32

Austin Independent School District v.

United States, 429 U.S. 990, 50 L.Ed.2d

"603 , 97 S.Ct. 517 (1977)...................... 32

Brown v. Board of Education (Brown I), 347

U.S. 483 , 74 S.Ct. 686 (1954) ................. 27 , 32

Brown v. Board of Education (Brown II),

349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 753, 99 L.Ed.2d

1083.......................................... 15 , 32 , 33

Calhoun v. Cook, 522 F. 2d 717, rehearing en

banc denied, 525 F. 2d 1203 (5th Cir.

1975)........................................ 20

Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education,

377 F. Supp. at 1131..........................28

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board,

498 F. Supp. 580 (M.D. La. 1980).............. 3 , 8 , 9

Davis v. School Commissioners, 402 U.S. 3357 . . . . It), 29, 33

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 948 U.S. 498, 483, 65

L.Ed.2d 902, 927-928, 100 S.Ct. 2758 (1980) . . 15, 29

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430,

88 S.Ct. 1689 , 20 L.Ed. 2d 716 (1968).......... 16, 26, 29 , 32 , 33

Keyes v. School District Number 1, 413 U.S.

189 (1973)................................

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 94 S.Ct. 3112,

41 L.Ed.2d 1069 ..........................

Ross v. Houston Independent School District,

F. 2d ___ (No. 81-2323, 5th Cir.

February 16, 1983)....................

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

537 F. 2d 800 (5th Cir. 1976) ........

21 , 33

16, 21, 22, 29, 32

(ii)

CASES PAGE

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklinberg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1, 91 S.Ct.

1267 , 28 L. Ed. 2d 554 , at 571 .................. 15 , 18 , 25 , 26 , 27 ,

29, 32, 53United States v. Gregory-Portland

Independent School District, F. 2d

__ (No. 80- 1943 , 5th Cir. 1981)..............32

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board

of Education, 407 U.S. 84 (1 972).............. 21

United States v. Texas Education Agency,

et al., CA No. 81-2257, __ F. 2d _

(5th Cir. March 1 , 1982)......................32

Valley v. Rapides Parish School Board, 646

F. 2d 925 (5th Cir. 1981) cert, denied

455 U.S. 939, 102 S.Ct. 1430, 71 L.Ed.2d

650 (1982)....................................32

1 (iii)

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 81-3476

CLIFFORD EUGENE DAVIS, JR., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

AND

DR. D'ORSAY BRYANT, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellees

and Cross-Appellants

AND

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellee

VERSUS

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants and

Cross-Appellees

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

REPLY BRIEF AND BRIEF AS CROSS-APPELLEE OF THE

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the District Court erred in not permitting

the School Board and its Superintendent to try their own compre

hensive magnet school concept desegregation plan, or, in not,

at the very least, pointing out the deficiencies in the School

Board's plan and giving them an opportunity to modify their

plan to overcome those deficiencies, before imposing its own

plan based upon an impermissible racial balancing standard?

2. If the Court below did not err in the respects indicated

above and as otherwise contended by appellant School Board, is

its present plan constitutionally insufficient as contended by

private plaintiffs-appellants?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

(i) Course of Proceedings and Disposition in Court Below

(ii) Statement of Facts

The procedural history of this school desegregation case

is described in detail in the prior brief for the East Baton

Rouge Parish School Board as appellant in these consolidated

case, No. 80-3922 and No. 81-3476, filed on or about May 24,

1982. See brief for appellant-cross-appellee East Baton Rouge

Parish School Board at 2-8 and 9-11. Accordingly, we include here

only the procedural history and facts that are relevant to the

issues presented by this appeal: The improper racial balancing

standard applied by the District Court in fashioning its plan, its

failure to permit the local school authorities to try their magnet

school concept plan (or at least permit them an opportunity to modify

-2-

their plan to correct any deficiencies found by the District

Court), the over-reach of the District Court's plan, and its

constitutional sufficiency over the objection of private plain

tiffs- appellants .

This brief will serve as the reply brief for the East Baton

Rouge Parish School Board to the brief of the United States in

No. 8105476 and as the brief of the East Baton Rouge Parish School

Board as cross-appellee to private plaintiffs-appellants in No.

81-3476. We will address first the position of the United States

and secondly the position of plaintiffs-appellants.

On September 11, 1980, the District Court granted partial

summary judgment as to the School Board's responsibility to further

desegregate this school system and ordered the School Board to

submit a desegregation plan to the District Court by October 15,

1980, barely one month later, even though the School Board had

requested 120 days to prepare and submit its plan. Davis v. East

Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 498 F. Supp. 580 (M.D. La. 1980)

(R, 1329-1344).1 At the time of this order, the school system had

just employed a new Superintendent of Schools, Dr. Raymond G.

Arveson. Although Dr. Arveson had had prior experience with big

city school systems and school desegregation, having been Superin

tendent of Schools in Minneapolis, Minnesota, he was not thoroughly

familiar with this school system and, obviously, would need some

time to formulate a comprehensive desegregation plan.

■̂ The designation "R" followed by a page number refers to the con

secutively paginated 16-volume record.

Utilizing his own prior experience with school desegregation

in Minneapolis and being aware of this school system's own previous

success with magnet schools, Dr. Arveson obtained School Board

approval to create a community advisory council, bi-racial in

nature and composed of citizens from all walks of life in the

community, for community input and to employ outside nationally

recognized experts in school desegregation."' Superintendent

Arveson also created a desegregation task force composed of school

employees to assist in the gathering of necessary data, etc. to 1

1The nationally recognized experts in school desegregation employed

by the Board was the firm of HGH, Inc. The principals of this

firm are Larry IV. Hughes, William M. Gordon, and Larry W. Hillman.

Larry Hughes is a professor and the chairman of the Department of

Administration and Supervision at the University of Houston, Texas.

Dr. Hughes specialized in the personnel programming side of school

desegregation. William M. Gordon is a professor of education at

Miami University, Oxford, Ohio. He specialized in pupil assignment

and curriculum development. Larry W. Hillman is a professor of

education at Wayne State University, Detroit. His specialty is

pupil transportation and metropolitan plan development.

Together the authors have been the principal designers or significant

contributors to over 75 desegregation plans. Most recently, they

were the architects of the plans submitted by the State Board of

Education of Ohio in the Cleveland and Columbus cases. Tye have

served as experts in developing desegregation plans for the United

States in school cases in this state as well as elsewhere. One or

more of them recently participated in developing the magnet school

plan (very similar to the plan developed for this school system) for

Chicago, Illinois, which has recently been approved by the United

States and the District Court.

Although the principals in HGH, Inc. were familiar with the desegre

gation expert employed by the United States, Dr. Gordon Foster, and

his belief in mandatory reassignment plans utilizing the tools of

pairing, clustering, non-contigious zones, cross-town busing, etc.,

they concluded that such a plan would not work in this community,

would be detrimental to the school system, and that a magnet school

concept, incentive-type approach would accomplish substantially the

same amount of desegregation without the detrimental effects.

-4-

assist him and the outside experts in developing such plan.

The school system expended some $400,000.00 in developing its

magnet school concept plan.

Due to Dr. Arveson having only recently become Superinten

dent and the magnitude of developing a comprehensive desegregation

plan for a metropolitan school system of this size, he repeatedly

requested the Court for additional time to develop a plan in

accordance with the guidelines established by the Court which the

Court, albeit reluctantly, granted permitting the filing with the

Court on January 9, 1981, a 185 page document entitled "A Proposal

for the Further Desegregation of the East Baton Rouge Parish

Schools". (R 1378-1428). This plan utilized mandatory reassignments

such as rezoning, pairing, etc., with a comprehensive use of magnet

schools, special focus schools, and special programs at all levels

of the school system.

At the commencement of trial on the merits of the School Board's

plan on March 4, 1981, the District Court read a 16 page statement

into the record. This statement warned the parties, particularly

the School Board, as to what the school system would face at the

opening of schools, indicated the Court was not satisfied with

either the plan proposed by the United States and plaintiff inter-

venors or the plan proposed by the School Board and ordered the

parties to commence private negotiations looking toward a consent

decree with such negotiations to begin at 9:00 a.m. on Wednesday,

March 11, 1981 and continue through at least March 24, 1981.

(R 1590-1607).

-5-

These court - ordered, three-cornered negotiations continued

on an almost daily basis until April 15, 1981 when the parties

advised the Court that they were unable to reach agreement on a

proposed consent decree. On April 16, 1981, the Court issued an

order terminating such discussions.

A short 15 days later, on May 1, 1981, the District Court

issued its findings and conclusions rejecting both the School

Board's plan and the Government's plan and ordering its own plan

to be implemented. However, rather than, taking the plan preferred

by the local school authorities and modifying it, or granting the

school authorities an opportunity to modify their plan to correct

what the District Court perceived as deficiencies, the Court

basically adopted the mandatory reassignment plan prepared by the

Government's expert, including pairing, clustering, rezoning, and

cross-town busing, with modifications reducing a few of the longest

cross-town busing components, closing some schools, etc.

The Court's plan closed fifteen elementary schools and one

high school. Of the sixteen middle schools (serving grades 6-8),

it converted fourteen of them to single-grade centers and two of

them to two-grade centers. It left six predominantly white schools

and seven predominantly black schools. It paired and clustered

( 3 8 4 school clusters) all of the remaining elementary schools.

Some bus routes, due to distance, heavy traffic, etc., are as

long as twenty-five miles and taking 45 minutes to one hour

in time, one way. The Court's plan also required the

- 6 -

removal of all temporary classroom buildings (being utilized

in order to alleviate overcrowding at particular schools) at

the remaining few predominantly one-race schools and established

a maximum student capacity of 27 students per classroom. In at

least 1 rapidly growing residential area of the parish, this in

ability to admit newly resident students has resulted in having

to utilize one 60 passenger school bus to transport only twelve

students to other schools with the bus route being approximately

39 miles long and taking 1 hour to complete.

The Court's plan also converted the school system's middle

schools (grades 6-8) to single-grade centers. Under this proposal,

a child could go to five different schools from the fifth to the

ninth grade. Its effect would have been absolutely disastrous.

It was only after repeated urging from Superintendent Arveson that

the Court finally approved, in part, a proposal maintaining the

middle school concept. The Board's proposal for middle schools

would have left one additional one-race school, Scotlandville

Middle School (adjacent to Scotlandville High School which the

Court had closed as being too isolated to be desegregated). The

Court rejected that portion of the proposal, requiring Scotlandville

Middle School to remain open but ordering the School Board to

maintain an actual enrollment of at least 101 white and not more

than 40% black (Order of May 7, 1982).

The Court's order directed implementation of its plan with

respect to elementary schools with the opening of schools in

August 1981 with the provisions applying to the secondary schools

- 7 -

to be implemented with the opening of schools in August 1982.

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 514 F. Supp.

869, 874 (M.D. La. 1981). The District Court (R 2010-2011),

and this Court, denied the School Board's applications to stay

implementation of the plan. Implementation of the plan, even

after elimination of the single-grade centers, resulted in the

loss of approximately 4,000 students after one year and now,

after two years, approximately 6,500 students.

The School Board and private plaintiff-intervenors both

noticed appeals from that judgment. The United States did not.

Those appeals (No. 81-3476 in this Court) have been consolidated

with the School Board's previous appeal (No. 80-3922 in this

Court). The District Court, thereafter continued to hear various motions

filed by the parties and continued to issue orders placing additional

requirements on the School Board. Some of these additional motions, rulings,

etc. are found in the record in Volume V, Page 1620 and proceeding

through Volume VI and Volume VII of the record.

Since the record was completed and forwarded to this Court

as of October 31, 1981, the District Court has continued to hold

hearings on various matters and issue orders generally placing

other additional requirements on the School Board. None of these

additional orders are contained in the record presently before this

Court and are not before this Court in this appeal. However, the

School Board timely filed notices of appeal from those orders

which are presently pending before this Court as Numbers 82-5̂ .98

and 82-3412, consolidated.

-8-

In the meantime, the School Board sought a stay of imple

mentation of the District Court's secondary school plan on

August 11, 1982. The Board's motion was denied by the District

Court on August 16, 1982 and its request to this Court for a

stay was denied on August 30, 1982.

Thereafter, on August 6, 1982, after approximately one year

of implementation of the Court's elementary school plan, the

United States filed in this Court a motion to stay further proceedings

in this appeal to afford the District Court an opportunity to re

evaluate and modify its plan in light of actual experience. That

motion advised this Court that the United States would prepare and

provide for the District Court and the parties an alternative to

the Court's existing desegregation plan. See Government Motion

to Stay Further Proceedings in this Court of August 6, 1982, Page

9. In that motion, the United States also stated that the District

Court accurately described the plan of their expert, Dr. Foster,

as a "classic pair 'em, cluster 'em, and bus 'em plan." Davis v.

East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 514 F. Supp. 869, 873 (M.D.

La. 1981).

The Government also in that motion labeled court - ordered

transportation "...generally to be a failed experiment...". See

Government Motion to Stay Further Proceedings in this Court of

August 6, 1982 at Page 3.

On August 30, 1982, this Court granted that motion, and on

September 15, 1982, this Court entered an order deferring for

-9-

sixty days action on a motion to reconsider its August 30 order

filed by private plaintiffs, by which time the parties were to

advise this Court "concerning the steps actually taken toward

seeking modification of the District Court's desegregation orders

and such further facts and circumstances on why the appeal should

be or should not be further delayed." The District Court then

issued a subsequent order requiring the Government to file its

proposed alternative plan within certain time limits.

The United States indicated a particular concern with the

School Board assertion that the Court's plan had caused approximately

4,000 students to leave the system in that first year of implementa

tion. In August 1982, the United States retained another school

desegregation expert, Professor Christine Rossell of Boston Univer

sity to undertake a study of this school system and the operation

of the court-ordered desegregation plan. Dr. Rossell's preliminary

study confirmed the Board's assertion finding that 4,244 students

had left the system since the year before the Court's plan went

into effect. See brief of United States in 81-3476, Page 4 and

Footnote 7.

On December 10, 1982, the United States filed with the

District Court and the parties its proposed alternative to the

District Court's plan "...designed to desegregate the public

schools in a more effective manner...." As stated by the Government

in its brief in 81-3476, at Page 5, the Rossell plan,

-10-

"...Rather than relying on mandatory assign

ment techniques ... employed educational incen

tives to attract departing students back to

the system and achieve a level of desegregation

comparable to that sought by the District

Court. Under the Rossell plan, desegregation

was to be accomplished by court - ordered school

closings, by encouraging the use of majority

transfers and by magnet schools...."

In fact, the Rossell plan drew freely from, including specific references

to, the magnet school plan originally proposed by the School Board.

Upon reviewing the proposed Rossell plan, Superintendent

Arveson and his staff and the School Board understood the Rossell

plan to be an alternative plan to be implemented in lieu of the

District Court's plan for the opening of schools for the 1983-84

school year. Superintendent Arveson and his staff also felt that

the Rossell plan had considerable merit.

On January 7, 1983, under the auspices of the District Court,

representatives of the Department of Justice met with members of

the School Board and Superintendent Arveson and his staff to explain

in greater detail the Rossell plan. It was at this meeting that

Superintendent Arveson and the School Board received their first

indication that this was not an alternative to the Court's plan,

but was to be gradually phased in over a period of time. No phase-

in implementation program had yet been devised by the Government..

On that same day, and again under the auspices of the District Court,

Superintendent Arveson and the School Board met with attorneys for

the NAACP to hear their objections to the Government's proposal.

Department representatives and Professor Rossell subsequently

met with members of the School Board staff on January 10-11, 1983

for a more detailed discussion. During these discussions, Super

intendent Arveson and his staff learned that the Government's

views with regard to gradual phasing-in of the Rossell plan would

offer no relief from the District Court cross-town busing, etc.

for several years. Later in January, the United States filed

with the District Court and the parties a comprehensive phase-in

implementation procedure, guidelines, quotas, a requirement -for

the expenditure of almost Two Million Dollars initially but with

no relief from the District Court's cross-town busing plan for

almost four years.

On February 7, 1983, Justice Department representatives met

with the School Board in a specially called public meeting to make

a formal presentation of the Rossell plan and to answer questions

about its implementation. Following that session, and a separate

meeting with NAACP representatives, the School Board on February 10,

1983 voted not to endorse the United States proposal at that time.

Because the United States believes that the success of the Rossell

plan depended on the full and complete support of the School Board,

they informed the District Court that it would be premature to press

for alternative remedial action and requested this Court to lift

the stay entered in this appeal at their request on August 50, 1982.

This Court, in response to that request, lifted the stay on March 18,

1983.

-12-

We agree with the United States that any plan imposed on

the school system should have the full and complete support of

the School Board. We would also hope they would have the full

and complete support of the United States. It would have been

helpful to have their support for the "incentive" or magnet school

concept two years ago when Superintendent Arveson and his staff

were developing the magnet school plan proposed by the Board.

As indicated heretofore, Superintendent Arveson and his staff

felt that the Government's incentive plan had considerable substan

tive merit and still feel that it does. At the time, however,

School Board elections had just been concluded and a virtually new

School Board had taken office on January 1, 1985. Six of the twelve

members of the Board had just been elected to the Board. In addition,

strong opposition from the N.AACP indicated that discovery, etc.

District Court hearings, etc. on the Government's plan could well

run into the summer before the Board would have any new order from

the District Court permitting it to make changes. With schools

opening in August 1983 for the 1983-84 school year, there was

simply not time to implement a comprehensive and complex proposal

for the 1983-84 school year, much less have the new members of the

Board fully understand the Governmen't meritorious and comprehensive

but complicated plan. Superintendent Arveson and his staff will,

of course, continue to look for modifications to the Court's plan,

or even an alternative plan, which does have a realistic chance

to work.

- 15 -

At present, the school system is completing its second

year under the Court's busing plan having lost something over

6,000 students. As indicated heretofore, that plan has been

made even more onerous by subsequent orders of the District Court

issued since this appeal and since the District Court record was

made up for this appeal. Those orders are not before this Court

on this appeal, but are the subject of other pending appeals

docketed in this Court as Numbers 82-3298 and 82-3412, consolidated.

Those appeals were also covered by the previous stay of proceedings

in this Court, but have now been released from such stay and a

new briefing schedule is being established for them.

-14-

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN NOT GIVING THE LOCAL

SCHOOL AUTHORITIES AN OPPORTUNITY TO TRY THEIR

PREFERRED MAGNET SCHOOL CONCEPT PLAN, OR, AT THE

VERY LEAST, IN NOT POINTING OUT THE DEFICIENCIES

IN THAT PLAN AND GIVING THE LOCAL SCHOOL AUTHORI

TIES AN OPPORTUNITY TO CORRECT SAME BEFORE IMPOSING

ITS OWN PLAN WHICH WAS CLEARLY BASED ON AN IMPER

MISSIBLE RACIAL BALANCING STANDARD.

The law in school desegregation cases is clear with respect

to the following principles:

(1) There is no universal answer to complex problems

of desegregation; there is obviously no one plan

that will do the job in every case. Green v.

County School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 88 S.Ct. 1689,

TO L.Ed.2d 716 (1968) ;

(2) The aim of the Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of

equal protection on which this litigation is

based is to assure equal educational opportunity

without regard to race; it is not to achieve

racial integration in public schools. Mi 11iken v .

Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 94 S.Ct. 3112, 41 L.Ed.2d

1069 (1974);

(3) The Constitution does not require any particular

racial balance in schools and district courts that

attempt to achieve such racial balance should be

reversed. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklinberg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1, 91 S.Ct. 1267, 28 L.Ed.2d

1541

(4) In the first instance, school authorities have the

primary responsibility for elucidating, assessing,

and solving these problems. Brown v. Board of

Education, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 755, 99 L.Ed.2d

1083 (Brown II - 1955);

(5) Only if school authorities fail, may judicial

authority be invoked. Swann, supra.

(6) Even when the Federal Court devises its own plan,

its power to restructure the operation of local

school systems is not plenary, the Court should

tailor the scope of the remedy to fit the violation

-15-

in light of the circumstances present and

the options available, taking into account

the practicalities of the situation, and

should defer to the preference of the local

school authorities wherever possible.

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 948 U.S. 498, 65

L.Ed.2d 902, 100 S.Ct. 2758 (1980); Green v.

County School Board, supra.; Davis v. School

Commissioners, 402 U.S. 3357 (1971 ) and

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

537 F. 2d 800 (5th Cir. 1976).

In the instant case, the School Board has not failed. It

has on repeated occasions voluntarily moved to meet constitutional

requirements as declared by decisions of this Court, and the Supreme

Court. In 1970, when advised by the District Court that its

existing operation did not meet the constitutional requirements

as expressed by later decisions, it voluntarily appointed a bi-

racial committee and ultimately submitted a new desegregation plan

which the District Court accepted as converting the system to a

unitary school system under existing decisions and from which

decision no party appealed. In 1980, when the Court again advised

that its existing operation, although previously approved by the

District Court, no longer met constitutional requirements as

established by newer decisions of the Supreme Court and this Court,

it immediately developed and filed with the Court a new comprehensive

plan designed to meet constitutional requirements and the criteria

established by the District Court itself.

The District Court should have deferred to the preference of

the local school authorities and given them an opportunity to try

their proposed magnet school-incentive plan. At the very least,

-16-

the District Court should have pointed out to the School Board

any deficiencies which it found in the School Board's plan and

given the School Board an opportunity to correct those deficien

cies before it imposed its own plan on the school system without

affording the opportunity for a hearing thereon. The District

Court, in devising its own plan, should have again deferred to

the expressed preference of the local school authorities for a

magnet-incentive type plan in building its own plan rather than

building its own plan off of the pairing-clustering-busing plan

then proposed by the United States.

This Court, at the very least, should reverse and remand to

the District Court with specific directions that racial balancing

is not required and that it should defer to the expressed preference

of the local school authorities for a magnet-incentive type plan

even though the District Court may feel some modifications to their

preference is necessary.

II. THE POSITION OF PLAINTIFF-INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS

COMPLETELY FAILS TO ESTABLISH ANY ABUSE OF DIS

CRETION IN THE DECISION OF THE DISTRICT COURT

WHICH WOULD JUSTIFY ITS REVERSAL ON THE GROUNDS

THAT IT DOES NOT GO FAR ENOUGH

Plaintiff-intervenors-appellants contend that the plan and

judgment of the District Court does not go far enough. They contend

that it should eliminate every racially identifiable school regard

less of the practicalities of the situation, the existing facts,

problems, obstacles, etc. and that it places the burden of desegre

gation only upon black citizens. Most of what they contend is

-17-

simply not correct. The District Court's plan leaves only a

very few one-race schools which the Court concluded were too

residentially, geographically, and racially isolated to be

desegregated without extreme long distance bus routes which

would impinge on the educational and physical well-being of

students under Swann, supra. In order to eliminate the totally

objectionable long distance busing as much as possible, he closed

both white schools and black schools. The rest of the schools

he either paired or clustered, which by their very nature equally

distributes the burden of desegregation as between black students

and white students.

It would be incomprehensible for this Court to order the

District Court to inflict more damage on this school system and

this community under the circumstances here present.

-18-

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN NOT GIVING THE LOCAL

SCHOOL AUTHORITIES AN OPPORTUNITY TO TRY THEIR

PREFERRED MAGNET SCHOOL CONCEPT PLAN, OR, AT THE

VERY LEAST, IN NOT POINTING OUT THE DEFICIENCIES

IN THAT PLAN AND GIVING THE LOCAL SCHOOL AUTHORI

TIES AN OPPORTUNITY TO CORRECT SAME BEFORE IMPOSING

ITS OWN PLAN WHICH WAS CLEARLY BASED ON AN IMPER

MISSIBLE RACIAL BALANCING STANDARD.

As stated by the United States in its brief at Page 11,

"...Once a constitutional violation is found,

it is in the first instance the responsibility

of local school officials to remedy that vio

lation. The District Court here recognized

that fact and encouraged the Board to devise

an acceptable desegregation plan. The Board's

preference for voluntary student transfers

triggered by educational incentives was well

founded.. . . "

We agree with that statement, but would point out that in every

instance this School Board has always come forth with a plan to

remedy such violation. In 1970, this Board voluntarily appointed

a bi-racial committee to devise an acceptable desegregation plan

and then adopted and filed with the Court the bi-racial committee's

plan with virtually no change. The School Board's 1970 desegrega

tion plan met constitutional requirements as indicated by the

jurisprudence at that time, was approved by the District Couit as

converting this school system to a unitary school system, and no

appeal was taken by any party.

When the District Court in 1980 finally rendered partial

summary judgment declaring that the Board's existing plan vas no

longer constitutionally sufficient under the new jurisprudence and

ordered the Board to submit a new plan, it immediately did so. And,

-19-

even though the District Court gave the local school authorities

a very short time within which to develop a new plan to meet

new jurisprudential constitutional requirements, the local

school authorities did not submit just a meager, hastily thrown

together plan. Under the guidance of a new Superintendent of

Schools, Dr. Raymond G. Arveson, with past experience in school

desegregation as Superintendent of the Minneapolis, Minnesota

School System, the School Board employed, at considerable expense,

a nationally recognized firm of experts in devising desegregation

plans, HGH, Inc. These experts believed, as did Superintendent

Arveson, that this school system could build upon its previous

success with magnet schools to formulate an incentive-type

desegregation plan which would acheive substantially the same

success as the "busing" type plan then proposed by the United States

and one which truly gave "realistic" promise of "working" and

working now. Equally important, they felt that it would "work"

without converting the system to a segregated all black system as

had occurred in other metropolitan areas such as Dallas, Atlanta,

Houston, New Orleans, Chicago, Detroit, and others, under the

mandatory assignment busing-type plans then proposed by the United

States.

This Court has previously noted the ineffectiveness of these

pairing-clustering-busing plans when it said in Calhoun v. Cook,

522 F. 2d 717, rehearing en banc denied, 525 F. 2d 1205 (5th Cir.

1975) at Page 718,

-20-

"Since 1958 when this school desegregation

suit was filed, the winds of legal effort

have driven wave after wave of judicial

rhetoric against the patrons of the Atlanta

public school system. Today, hindsight high

lights the resulting erosion, revealing that

every judicial design for acheiving racial

desegregation in this system has failed. A

totally segregated system which contained

115.000 pupils in 1958 has mutated to a sub

stantially segregated system serving only

80.000 students today. A system with a 70%

white pupil majority when the litigation began

has now become a district in which more than

85% of the students are black...Out of 148

schools in the city system, Atlanta still

operates 92 schools with student bodies which

are over 90% black."

Present information indicates that the Atlanta school system is

now approximately 95% black. See also Ross v. Houston Independent

School District, ____ F. 2d ____ (No. 81-2523, 5th Cir. February 16,

1983) in which this Court affirmed the District Court in refusing

to impose additional pairing, busing requirements on HISD and

instead permitted them to continue to implement and expand their

magnet school program.

Although the School Board was aware of the Supreme Court's

holding that fear of white flight cannot be accepted as a reason

for acheiving anything less than the Constitution requires,

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education, 407 U.S.

84 (1972), it was also aware of the disastrous effect that these

pairing-clustering-busing plans had had on metropolitan areas such

as Atlanta, New Orleans, Houston, Dallas, Detroit, Chicago, Cleve

land, etc. Furthermore, it was also aware of this Court's holding in

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 557 F. 2d 800 (5th

-21 -

Cir. 1976) that in considering various permissible plans, a plan

"calculated to minimize white boycotts” may be preferred.

In attempting to develop an acceptable plan as permitted

under Stout, supra. , the School Board spared neither effort nor

expense. It utilized the past experience in school desegregation

in Minneapolis, Minnesota of its new Superintendent, it employed

a nationally recognized firm of desegregation experts at consider

able expense, created a community advisory committee, a working

desegregation task force of its own employees taken away from

their normal duties and ultimately developed and presented to the

Court a comprehensive magnet-incentive type plan which had real

promise of "working realistically".

Superintendent Arveson and his staff also spent a great deal

of time studying the already successful Houston Independent School

District's magnet school program and the School Board's plan was

modeled, to a great extent, after the Houston plan. The School

Board also employed Mr. Larry Marshall, a black Assistant Super

intendent for HISD, in charge of their magnet school program, to

review and assist the Board in their proposed magnet school plan,

and he testified during the trial as to the succes of the magnet

school program in Houston and the likelihood of its success in

Baton Rouge.

Mr. Marshall also testified that based upon his experience

in Houston and studies of desegregation plans in other school

systems that pairing-clustering-cross - town busing as desegregation

tools were obsolete. He further testified that such pairing had

-22-

not worked in Houston and that ultimately the Courts had unpaired

the schools which had previously been paired. As a matter of

fact, the end result had been that they were busing black children

from a formerly all black school to a school which had now become

also all black.

In spite of this good faith effort and expense, the District

Court announced, at the outset of the trial, that the School Board’s

magnet school plan was not acceptable, ordered the trial to commence,

and ordered the parties into private negotiations as soon as the

trial was completed. (R, 1590-1607). The trial itself consisted

primarily of presentation of the Board's plan by the Board's

Superintendent and expert and the Government's plan by the Govern

ment's expert. The private, three-cornered, negotiations commenced

on March 11, 1981 as specified and continued on an almost daily

basis until April 15, 1981 (most of the negotiating was between

the School Board and the United States with the NAACP giving little

indication as to what, if anything, that it would agree to) when

the parties advised the Court that they had been unable to reach

agreement as to a consent decree. Approximately 15 days thereafter,

on May 1, 1981, the District Court issued its findings, conclusions,

and order rejecting the School Board's magnet school proposal and

ordering its own plan implemented without ever pointing out to

the School Board the perceived deficiencies in its plan and giving

them an opportunity to correct same. No hearing was held on the

Court's plan before it was imposed.

-23-

An examination of the Court's plan (R, 1555-1607, 514 F.

Supp. 869) clearly indicates that the Court built its plan off

of the mandatory assignment, pairing-clustering-busing plan

proposed by the United States with certain modifications elimina

ting a few of the longest (time and distance) cross-town bus

routes. The Court did so by closing fifteen elementary schools

and one high school, converting fourteen of sixteen middle schools

to one-grade centers and two middle schools to two-grade centers,

leaving six predominantly white schools and seven predominantly

black schools due to their complete racial and geographic isolation

and pairing and clustering (3 § 4 school clusters) of all the

remaining elementary schools. An examination of the projected

student enrollment by race attached to the Court's plan indicates

clearly that except for the schools closed or left alone because

of racial and geographic isolation, the Court's primary purpose

was to achieve, as closely as possible, a 601 white and 401 black

racial balance in all of the remaining schools. (Findings, Con

clusions, and Plan, Record, Vol. V, Pages 1555-1588, also found

at 514 F. Supp. 869).

We respectfully submit that the Court's plan makes it clear

that the Court started out with the goal of acheiving a racial

balance in as many of the schools to remain open as possible by

using the tools of closing schools, pairing and clustering to

do so. Additional orders of the District Court issued subsequent

to the record before the Court in this appeal, which established

-24-

a mandatory perpetual racial balance of 601 white and 401 black

at Scotlandville Middle School and a 601 white 401 black quota

for admission to the Baton Rouge High Magnet School are further

examples of the Court's racial balancing intent. We suggest

that such is clearly contrary to the holding of the Supreme Court

in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklinberg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1,

91 S.Ct. 1267, 28 L.Ed.2d 554, at 571, that requiring or attempting

to racially balance every school goes beyond constitutional

requirements.

This principle was again expressed by the Supreme Court in

1974 in Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 94 S.Ct. 3112, 41 L.Ed.2d

1069 when it said:

"...The aim of the Fourteenth Amendment

guarantee of equal protection on which this

litigation is based, is to assure that state

supported educational opportunity is afforded

without regard to race; it is not to acheive

racial integration in public schools..."

[Emphasis Added].

We respectfully submit that the District Court's plan is fatally

defective in attempting to acheive a racial balance in all schools

and then imposing a remedy which goes far beyond the scope of the

existing violation under the circumstances and facts here present.

In addition, we respectfully submit that the District Court

further erred in not pointing out its perception and conclusion

as to specific deficiencies in the School Board's plan and giving

the School Board an opportunity to correct those deficiencies and

make their plan a constitutionally acceptable plan. It is true

-25-

. W .— * * K

that during the course of the proceedings in the Court below ,

the United States and private plaintiffs raised objections to

the plan and the United States pointed out what it perceived

to be certain deficiencies in the plan. They have reiterated

some of those deficiencies in their brief. It must be remembered,

however, that at that time the parties were in trial proceedings

and the School Board, its Superintendent, and its outside experts

disagreed with the Government as to those deficiencies and were

trying to convice the’ District Judge that they were not deficiencies.

We respectfully submit that after the trial was completed,

the District Court as the final arbiter, should, at the very least,

have advised the Board of what it perceived and had concluded to

be fatal deficiencies and given the Board an opportunity to correct

those decisions before inserting itself into the educational process

and drawing its own plan.

Our courts have long recognized that there is no one desegre

gation plan that is the only solution in eradicating a formerly

dual school system. The Supreme Court noted as far back as 1968

in Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 , 88 S.Ct. 1689, <-0

L.Ed.2d 716 (1968), at 439, that there is

"...no universal answer to complex problems

of desegregation; there is obviously no one

plan that will do the job in every case. The

matter must be assessed in light of the cir

cumstances present and the options available

in each instance...".

This principle is still in effect today. See Swann v . Chailotte

Mecklinberg Board of Education, supra., at 16.

-26-

V • •*. • V ’

4 6 f ~ 2 * r * - -v -

W l < 7

Another principle established by the Supreme Court early

on, and which still exist today, as the rule in desegregation

cases, is that,

"...School authorities have the primary

responsibility for elucidating, assessing,

and solving these problems;..."

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 753, 99 L.Ed.2d

1085 (Brown II) at 299-300 and Swann, supra., 402 U.S. at 15-16.

Only if school authorities fail, may judicial authority be invoked.

Swann, supra., 402 U.S. at 15-16. Here, the School Board has not

failed. In 1970, when the District Court told the School Board

it must further desegregate its schools, the School Board voluntarily

appointed a bi-racial committee and subsequently filed a desegregation

plan which the District Court found to be constitutionally acceptable

under existing law and from which no appeal was taken by any party.

In 1980, when the District Court again told the School Board

it must further desegregate its schools in compliance with present

judicial decisions, the School Board through Superintendent Arveson

and his staff immediately commenced full scale, good faith efforts

to provide the Court with a constitutionally acceptable plan under,

and in accordance with, the guidelines specifically established by

the Court. (R, 1329-1344 at 1343). This plan, prepared by profes

sional educators with the assistance of nationally recognized

desegregation experts, was based upon and designed to meet the

specific criteria established by the District Court in its order.

-27-

the

, J55 •

Considering the specific criteria established by

District Court, it should not have come as a surprise to anyone

that professional educators would try to develop some type of

plan, some alternative, to the experience proven disruptive and

disastrous pairing-clustering-busing type plan then proposed by

the United States and plaintiff-intervenors. Those specific

criteria were:

"1. To acheive a unitary school system.

2. To provide an organizational structure

which will ensure optimum educational

opportunities for all children with a

minimum of disruption.

5. To adjust the assignment of students to

available physical facilities .

4. To utilize available funds to the great

est educational advantage.

5. To acheive the maximum possible community

acceptance of the plan thereby resulting

in minimal resegregation.

6. To reassign students in a manner which

enhances the instructional program of the

system.

7. To provide for maximum teachability through

the matching of assignments with teacher

competencies and training.

8. To utilize the existing transportation in

a supportive role to the instructional and

organizational framework of the system.

9. To minimize disruptive transition for

students, school personnel, and parents

and at the same time comply with the man-

date of the courts in achieving a unitary

system." (Carr v. Montgomery County Board

of Education, 377 F. Supp. at 1131).

[Emphasis Added].

-28-

The School Board's plan met these criteria and had

of "working" and working "realistically", that is,

constitutional requirements and perserving a first

tional system for all students regardless of race.

real promise

meeting

class educa-

The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that school authorities

have broad discretionary powers in the area of educational policy

and that courts have this power only if a constitutional violation

takes place. Swann, supra. , 28 S.Ct.2d at 567. It has also said

"...The power of the federal courts to restruc

ture the operation of local and state governmental

entities is not plenary... federal court is required

to tailor the scope of the remedy to fit the

nature and extent of the...violation." (Citations

Omitted). Fullilove v. Klutznick, 948 U.S. 498,

483, 65 L.Ed.2d 902, 927-928, 100 S.Ct. 2758

(1980).

Court orders to remedy constitutional deprivations, the Supreme

Court has said, must be drawn

"...in light of the circumstances present and

the options available..." Green, supra. , 391

U.S. at 439 (1968), "taking into account the

practicalities of the situation..." Davis v.

School Commissioners, 402 U.S. 3337 (1971) .

The law of the Fifth Circuit is the same.

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

537 F. 2d 800 (5th Cir. 1976).

In view of those decisions, the practicalities of the s

here existing, the geographic obstacles to be faced, the res

preferences of individual citizens, the very emotional impac

by judicial decrees affecting peoples children, the dismal r

of pairing-clustering-busing plans in other metropolitan are

the good faith effort of this school system, Dr. Arveson and

ituation

idential

t caused

esul t

as and

his

-29-

staff, to provide the Court with a plan which would meet

constitutional requirements and the Court's own criteria,

Ithe District Court should have afforded the local school

authorities with an opportunity to try their preferred plan.

At the very least, before imposing its own plan without giving

the parties an opportunity to be heard with respect to that plan,

the District Court grievously erred in not pointing out to the

School Board the deficiencies he perceived in their plan and

giving them an opportunity to correct same.

As noted heretofore, the United States noted certain claimed

deficiencies in the Court below as they do in their present brief.

We believe it is also worth noting, however, that the alternative

proposal which they submitted to the Court and the parties in

December 1982 (the Rossell plan) specifically refers, basically

with approval, to the School Board's original magnet school pro

posal approximately 20 times (Rossell plan Pages 1415, 1417, 1418,

1419, 1420, 1421, 1422, 1423, 1424, 1425, and 1429 - However, such

plan is not contained in this record and is not before this Court

on appeal) and either approved or adopted and expanded most of

the concepts and programs in the School Board's original magnet

school proposal.

If the United States had learned by 1979- 80 wThat it apparently

learned by December 1982, that busing plans are a "...failed

experiment..." and if the cooperative reasonable and responsible

attitude exhibited by the United States in 1982 had also been

-30-

present in 1979-80, it is highly probable that this school

system would today be operating under a constitutionally

acceptable plan providing a better educational opportunity

for all children without the catastrophic loss of some 6,500

students. That liklihood would also be present if the Court

below had given the school system an opportunity to correct

any deficiencies which the Court found in Superintendent Arveson's

plan.

. Defendants-appellants, East Baton Rouge Parish School Board,

its Superintendent and staff, respectfully submit that the decision

and judgment of the Court below should be reversed and remanded

back to that Court for further proceedings with specific directions

to the District Court to defer to the local school authorities

preference for a magnet school-incentive type desegregation plan

without the disastrous pairing-clustering-cross-town busing except

where absolutely necessary, as a last resort, to meet constitutional

requirements. Such remand should also contain directions regarding

limitations on the racial balancing approach and intrusion by the

Court into the daily operation of the school system.

II. THE POSITION OF PLAINTIFF-INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS

Plaintiff-intervenors urge

of the District Court primarily

Court's order and plan does not

Court to remand to the District

this Court to reverse the judgment

on the grounds that the District

go far enough and urges this

Court with directions to eliminate

-51-

• >

every predominantly one-race school regardless of the consequences

and regardless of the effect on children, whether black or white.

They also urge the prohibition of any magnet schools, special

programs, etc., in which parents would have any choice regarding

the educational opportunities of their children, whether white

or black. We respectfully submit that such action by this Court

would have an absolutely disastrous effect, not only on this school

system, but on this community as a whole.

We would also respectfull-y suggest that such a decision would

be contrary to the holdings, spirit, and intent of every decision

of the Supreme Court beginning with Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686 (1954)(Brown I), Brown II, supra.,

Green v. County School Board, supra., Alexander v. Holmes County

Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19, 90 S.Ct. 29, 24 L.Ed.2d 19 (1969),

Keyes v. School District Number 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973), Swann,

supra., Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 94 S.Ct. 3112, 41 L.Ed.2d

1069 and Austin Independent School District v. United States, 429

U.S. 990, 50 L.Ed.2d 603, 97 S.Ct. 517 (1977). We would also

respectfully submit that such decision would be contrary to, and

go far beyond, the decisions of this Court in this area of the law

including United States v. Texas Education Agency, et al., CA No.

81-2257 ____ F. 2d ____ (5th Cir. March 1, 1982); Stout v. Jefferson

County Board of Education, supra.; Valley v. Rapides Parish School

Board, 646 F. 2d 925 (5th Cir. 1981), cert, denied 455 U.S. 939,

102 S.Ct. 1430, 71 L.Ed.2d 650 (1982); United States v. Gregory-

Portland Independent School District, ___ F. 2d ____ (No. 80-1943,

-32-

5th Cir. 1981); and Ross v. Houston Independent School D i s t r i c t ,

No. 81-2523 (5th Cir. February 16, 1983).

As indicated heretofore, it is clear that,

"...School authorities have the primary

responsibility for elucidating, assessing,

and solving these problems;..." Brown 11,

supra., at 299-300 and Swann, supra., at

15-16

and only if school authorities fail, may judicial authority be

invoked. Swann, supra., 402 U.S. at 15-16. Beyond that point,

it is also clear that the District Courts are accorded broad and

flexible powers in fashioning an appropriate remedy for the

particular facts of the case before it. Such remedies and plans

should be drawn "in light of the circumstances present and the

options available..." Green, supra., 591 U.S. at 439, "...taking

into account the practicalities of the situation..." Davis v.

School Commissioners, 402 U.S. 33 at 37 and such plan should

reconcile "...the competing interests involved..." Swann, supra. ,

402 U.S. 1, at 26.

As indicated heretofore, there is no one plan that is sacrosanct

in desegregating a school system. Here, plaintiff-intervenors never

submitted a desegregation plan of their own. They only supported

the Government's plan. The District Court tried to reconcile the

competing interests and take into consideration the practicalities

of the situation, the geography of the parish, the location of

schools, and to minimize, at least to some extent, the objectionable

long distance cross-town busing.

The District Court found it necessary to close some formerly

all black schools and some formerly all white schools. In fact,

the closure of some of the black schools complained of by

plaintiff-intervenors such as Hollywood Elementary School, Fair-

field Elementary School, and Wyandotte Elementary School, were

actually formerly white schools which had gradually become black

schools due to residential population changes.

With regard to plaintiff-intervenors' contention that the

busing is one way with only black students being bused to white

schools, this is simply not true. The great majority of the

schools in the system under the Court's plan were either paired

or clustered. A pair or a cluster, by its very nature, calls for

assigning black students from a formerly all black school to

formerly all white schools and reassigning white students from

formerly all white schools to formerly all black schools. For

example, the Court's order pairs Pride (formerly white) and

Cheneyville (formerly black); it .pairs Baker Heights (formerly

white) and Beechwood (formerly black); and it paired Jefferson

Terrace (formerly white) and Mayfair (formerly black). The Court's

three and four school clusters included one formerly black and

either two or three formerly white schools, and all the students

in the cluster, white and black, were reassigned within those four

schools. Obviously, more white students are being reassigned than

are black students.

Insofar as plaintiff-intervenors contend that the Court

below did not go far enough, defendants respectfully submit that

- 54 -

it is clear that there has been no abuse of discretion on

the part of the District Court. To the contrary, if anything,

the District Court went too far.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, and for the reasons contained

in prior briefs of appellant, East Baton Rouge Parish School

Board, we respectfully urge the Court to reverse the decision

of the District Court and, at the very least, remand to that

Court with directions to give preference to the magnet - incentive

type plan preferred by the local school authorities and, hopefully,

by the United States.

Respectfully submitted

JOHN F. WARD, JR.

ROBERT L. HAMMONDS

1111 South Foster Drive, Suite C

P.0. Box 65236

Baton Rouge, LA 70896

(504) 923-3462

ATTORNEYS FOR DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

‘AND CROSS-APPELLEES, EAST BATON

ROUGE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD

-55-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that two copies of the above and

foregoing Brief has this day been mailed, postage prepaid,

to Ms. Mildred Matesich, Civil Rights Division, Department

of Justice, Washington, DC 20530; Mr. Robert C. Williams,

1822 N. Acadian Thruway (W), Baton Rouge, LA 70802; and to

Mr. Theodore Shaw and Mr. Napoleon Williams, 10 Columbus

Circle, Suite 2030, New York, NY 10019.

BATON ROUGE, LOUISIANA, this 20th day of May, 1983.

- 36-