Ford v. Wainwright Brief of Respondent

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ford v. Wainwright Brief of Respondent, 1985. f4cfaa1b-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/89278f8b-9d01-4604-94e8-4084200b084f/ford-v-wainwright-brief-of-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

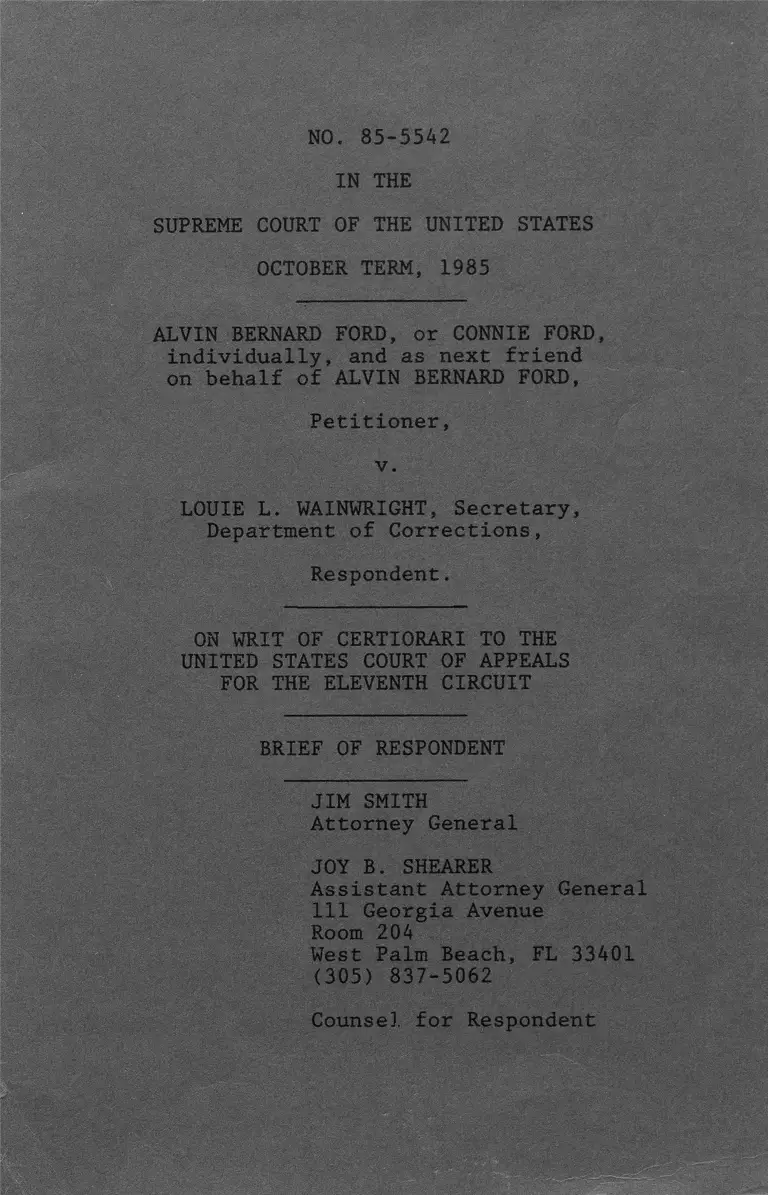

NO, 85-5542

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1985

ALVIN BERNARD FORD, or CONNIE FORD,

individually, and as next friend

on behalf of ALVIN BERNARD FORD,

Petitioner,

v.

LOUIE L. WAINWRIGHT, Secretary,

Department of Corrections,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF RESPONDENT

JIM SMITH

Attorney General

JOY B. SHEARER

Assistant Attorney General

111 Georgia Avenue

Room 204

West Palm Beach, FL 33401

(305) 837-5062

Counsel for Respondent

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I.

WHETHER THE HUMANITARIAN

POLICY DEFERRING EXECUTION

OF AN INSANE PRISONER UNTIL

HIS SANITY IS RESTORED SHOULD

BE ELEVATED TO AN EIGHTH

AMENDMENT RIGHT?

II.

WHETHER, IF AN EIGHTH AMEND

MENT RIGHT TO BE SANE AT

THE TIME OF EXECUTION EXISTS,

FLORIDA'S PRESENT PROCEDURE

ADEQUATELY PROTECTS IT?

III.

WHETHER, PURSUANT TO THIS

COURT'S CONTROLLING PRECEDENT

OF SOLESBEE v. BALKCOM,

339 U.S. 9 (1950), FLORIDA'S

PROCEDURE FOR DETERMINING

SANITY OF CONDEMNED PRISONERS

MEETS THE REQUIREMENTS OF

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT PROCEDURAL

DUE PROCESS?

11

Page

Questions Presented i

Table of Authorities iv-xiv

Opinions Below 1

Jurisdiction 2

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved 2

Statement of the Case 2-11

Summary of the Argument 12-18

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Argument

I. THE HUMANITARIAN

POLICY DEFERRING

EXECUTION OF AN INSANE

PRISONER UNTIL HIS

SANITY IS RESTORED

IS NOT A FUNDAMENTAL

RIGHT OF THE INDIVIDUAL

REQUIRING EIGHTH

AMENDMENT PROTECTION. 19-43

II. SHOULD THE COURT FIND

THERE IS AN EIGHTH

AMENDMENT RIGHT TO

BE SANE AT THE TIME

OF EXECUTION, THE

PRESENT FLORIDA PROCEDURE

ADEQUATELY PROTECTS IT. 44-56

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS - CONTINUED

Page

III. PURSUANT TO

CONTROLLING

PRECEDENT OF THIS

COURT, SOLESBEE

v. BALKCOM,

339 U.S. 9 (1950),

FLORIDA'S PROCEDURE

FOR DETERMINING

SANITY OF CONDEMNED

PRISONERS MEETS

THE REQUIREMENTS

OF FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENT

PROCEDURAL DUE

PROCESS. 57-80

Conclusion 81

IV

Cases Page

Ake v. Oklahoma,

U.S.

105 S.Ct. 1090 (1985) 40,67

Allen v. McCurry,

449 U.S. 90 (1980) 49

Barclay v. Florida,

463 U.S. 939 (1983) 38

Barefoot v. Estelle,

463 U.S. 880 (1983) 72

Board of Curators of the

University of

Missouri v. Horowitz,

435 U.S. 78 (1978) 78

Brown v. Wainwright,

392 So.2d 1327 (Fla.),

cert, denied,

454 U.S. 1000 (1981) 3

Cabana v. Bullock,

U.S.

5T“U.S.L.W. 4105

(op. filed January 22,

1986) 53

Caldwell v. Line,

679 F.2d 494

(5th Cir. 1982)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

49

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - CONTINUED

Cases Page

Caritativo v. California,

357 U.S. 549 (1958) 60

Coker v. Georgia,

433 U.S. 584 (1976) 25

Coolidge v. New Hampshire,

403 U.S. 443 (1971) 53

Delaney v. Giarrusso,

633 F .2d 1126

(5th Cir. 1981) 49

Dusky v. United States,

362 U.S. 402 (1960) 29

Engle v. Issac, 456 U.S. 107

(1982) 47

Estelle v. Gamble,

429 U.S. 97 (1976) 23

Estelle v. Smith, 451 U.S. 454

(1981) 45

Fisher v. United States,

425 U.S. 391 (1976) 29

Ford v. State, 374 So.2d 496

(Fla. 1979), cert,

denied, Ford v. Florida,

445 U.S. 972 (1980) 2

Ford v. State,

407 So.2d 907

(Fla. 1981) 2

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - CONTINUED

Cases Page

Ford v. Strickland,

676 F .2d 434

(11th Cir. 1982) 3

Ford v. Strickland,

696 F .2d 804

(11th Cir.),

cert, denied,

464 U.S. 865 (1983) 3

Ford v. Strickland,

734 F .2d 538

(11th Cir. 1984) 9

Ford v. Wainwright,

451 So.2d 471

(Fla. 1984) 1,8,66

Ford v. Wainwright,

752 F .2d 526

(11th Cir. 1985) 10

Furman v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238 (1972) 24

Gardner v. Florida,

430 U.S. 349 (1977) 17,62,63

Gerstein v. Pugh,

420 U.S. 103 (1975) 50

Gilmore v. Utah,

429 U.S. 1012 (1976) 76,77

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - CONTINUED

Cases Page

Goode v. Wainwright,

448 So.2d 999

(Fla. 1984) 45

Goode v. Wainwright,

731 F .2d 1482

(11th Cir. 1984) 10,65

Graham v. Richardson,

403 U.S. 365 (1971) 60

Gray v. Lucas,

710 F .2d 1048

(5th Cir. 1983) 27

Gregg v. Georgia,

428 U.S. 153 (1976) 25,38,63

Hewitt v. Helms,

459 U.S. 460 (1983) 68

Hickey v. Morris,

722 F .2d 543

(9th Cir. 1983) 69

Hill v. Johnson,

539 F .2d 439

(5th Cir. 1976) 49

Hortonville Joint School

District No. 1 v.

Hortonville Education

Association,

426 U.S. 482 (1976) 69

V l l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - CONTINUED

Cases Page

Ingraham v. Wright,

430 U.S. 651 (1977) 25,26

Kirby v. Illinois,

406 U.S. 682 (1982) 51

Lee v. Winston,

718 F .2d 888

(4th Cir. 1983) 48

Mathews v. Eldridge,

424 U.S. 319 (1976) 17,74

Meachum v. Fano,

427 U.S. 215 (1976) 61

Morrissey v. Brewer,

408 U.S. 471 (1972) 68

Nobles v. Georgia,

168 U.S. 515 (1897) 58,79

Palmer v. Thompson,

403 U.S. 217 (1971) 43

Pate v. Robinson,

383 U.S. 375 (1966) 67

People v. Eldred,

103 Colo. 334,

86 P .2d 248 (1938) 22

People v. Preston,

345 111. 11,

177 N.E. 761 (1931) 22

ix

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - CONTINUED

Cases Page

People v. Riley,

37 Cal.2d 510,

235 P .2d 381 (1951) 23

Phyle v. Duffy,

34 Cal.2d 144,

208 P .2d 668 (1949) 31

Powell v. Texas,

392 U.S. 514 (1968) 25

Preiser v. Rodriguez,

411 U.S. 475 (1973) 48

Rhodes v. Chapman,

452 U.S. 337 (1981) 38,39

Roberts v. United States

391 F .2d 991

(D.C. Cir. 1968)

>

41,42

Robinson v. California,

370 U.S. 660 (1962) 25

Ross v. Moffitt,

417 U.S. 600 (1974) 28,52

Schick v. Reed,

419 U.S. 256 (1974) 61

Shadwick v. Tampa,

407 U.S. 345 (1972) 50

Smith v. Estelle,

602 F .2d 694

(5th Cir. 1979) 45

X

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - CONTINUED

Cases

Solesbee v. Balkcom,

339 U.S. 9 (1950)

Page

1,10,12,16,

18,22,37,

52,57,58,

60,61,62,

63,64,65,

79

Spinkellink v. Wainwright,

578 F .2d 582

(5th Cir. 1978) ,

cert, denied,

440 U.S. 976 (1979) 37,61

Stone v. Powell,

428 U.S. 465 (1976) 49

Sumner v. Mata, 449 U.S. 539

(1981) 47

Trop v. Dulles,

356 U.S. 86 (1958) 42

United States v. Gouveia,

U.S.

104 s!ct.~2292 (1984) 51

Wainwright v. Ford,

U.S.

104 S.Ct. 3498 (1984) 9

Wainwright v. Torna,

455 U.S. 586 (1982) 28,52

Williams v. New York,

337 U.S. 241 (1949) 62,63

XI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES -- CONTINUED

Cases Page

Williams v. Wallis,

734 F .2d 1434

(11th Cir. 1984) 69,76

Statutes and Rules Page

Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann.,

§13-4021 (1982) 36

Ark. Stat. Ann.,

§43-2622 (1977) 36

Calif. Penal Code,

§3701 (1979) 36

Conn. Gen. Stat.,

§54-101 (1980) 36

Fla. Stat.,

§922.07 (1983) 3,8,9,12,

14,16,21,

30,32,44,

64,65,73,

78

Fla. Stat.,

§922.07(1) 7,54

Georgia Code Ann.,

§17-10-61 36

Illinois Rev. Stat.

(1982), Ch. 38,

§1005-2-3(a) 55

xii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - CONTINUED

Statutes and Rules Page

Kan. Stat.,

§22-4006 (Supp. 1981) 36

Md. Ann. Code,

Art. 27, §75(c) 36

Mass. Gen. Laws Ann.,

Ch. 279, §62

(1984 Supp.) 36

Miss. Code Ann.,

§99-19-57

(1983 Supp.) 36

Neb. Rev. Stat.,

§29-2537 (1979) 36

Nev. Rev. Stat.,

§176.425 (1983) 36

New Mex. Stat. Ann.,

§31-14-4 (1978) 36

N.Y. Corr. Law,

§665 (1983 Supp.) 36

Ohio Rev. Code Ann.,

§2949.28 (1982 Supp.) 36

Okla. Stat. Ann.,

§1005 (1983) 36

Utah Code Ann.,

§77-19-13(1) (1982) 36

X1X1

Statutes and Rules Page

Wyo. Stat.,

§7-13-901

(1984 Cum. Supp.) 36

Rule 9(b), Rules Governing

28 U.S.C. §2254

Proceedings 29

28 U.S.C.,

§2254(a) 47,53

28 U.S.C.,

§2254(d) 47

Other Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - CONTINUED

4 Blackstone,

Commentaries,

395-396 (13th Ed. 1800) 28

Comment, Execution of

Insane Persons,

23 So.Cal.L.Rev. 246

(1950) 41

Granucci, Nor Cruel and

Unusual Punishments

Inflicted: The

Original Meaning,

57 Cal.L.Rev. 839 (1969) 24

X X V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - CONTINUED

Other Page

Hazard and Louisell,

Death, the State

and the Insane:

Stay of Execution,

9 UCLA L.Rev. 381 (1962) 27

E. Kubler-Ross,

On Death and Dying

(1969) 33

Coke, Third Institute 6

(1797) 30

LaFave and Scott,

Handbook on Criminal Law

(1972) 55

J. Story, On the

Constitution of the

United States,

§1908 at 680

(3rd Ed. 1858) 24

Tribe, American

Constitutional Law

(1978) 65

Van den Haag, In Defense

of the Death Penalty:

A Legal-Practical-Moral

Analysis, 14 Crim. L.

Bull. 5 (1978) 32

Van den Haag, Punishing

Criminals (1975) 32,35

1

NO. 85-5542

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1985

ALVIN BERNARD FORD, or CONNIE FORD,

individually, and as next friend

on behalf of ALVIN BERNARD FORD,

Petitioner,

v.

LOUIE L. WAINWRIGHT, Secretary,

Department of Corrections,

Respondent.

OPINIONS BELOW

Respondent accepts the

Petitioner's citations. In addition,

the Florida Supreme Court's opinion

on the issues raised in this case

is reported as Ford v. Wainwright,

451 So.2d 471 (Fla. 1984), and it is

set out at A 5.

2

JURISDICTION

Respondent accepts the

Petitioner’s statement.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

Respondent accepts the

Petitioner’s statement.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On July 21, 1974, the Petitioner,

Alvin Bernard Ford, murdered a police

officer in the course of an attempted

robbery. After years of litigation,

his direct and collateral appeals

were concluded. Ford v. State,

374 So.2d 496 (Fla. 1979), cert.

denied, Ford v. Florida, 445 U.S. 972

(1980) [direct appeal]; Ford v. State,

407 So.2d 907 (Fla. 1981) [a

3

consolidated collateral appeal and

original habeas corpus action];

Ford v. Strickland, 676 F.2d 434

(11th Cir. 1982) [panel decision]

and Ford v. Strickland, 696 F.2d 804

(11th Cir), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 865

(1983) [a federal habeas corpus denial

which was affirmed by a panel and

ultimately the en banc Eleventh

Circuit]. Ford was also a named

party in Brown v. Wainwright,

392 So.2d 1327 (Fla.), cert, denied,

454 U.S. 1000 (1981).

In late 1983, the governor of

Florida appointed a commission of

three psychiatrists pursuant to the

provisions of Fla. Stat. §922.07

(1983) to evaluate Ford's sanity for

execution. The commissioners were

directed to examine Ford for the

4

purpose of determining whether he

understood the nature of the death

penalty and why it was to be imposed

upon him. The commissioners examined

Ford on December 19, 1983. They also

reviewed materials submitted to them

by counsel for Ford, inspected Ford's

prison cell and spoke to his guards,

and reviewed his prison medical

records. Each commissioner then

submitted a written report to the

governor stating his findings.

In his Statement of the Case,

Ford describes the findings as

"conflicting." The record shows

otherwise, for all three commissioners

independently concluded that Ford

understood the death penalty and

why it was to be imposed on him.

5

Dr. Ivory reported:

I formed the opinion that

the inmate knows exactly

what is going on and is able

to respond promptly to ex

ternal stimuli. In other

words, in spite of the verbal

appearance of severe in

capacity, from his consistent

and appropriate general

behavior he showed that he

is in touch with reality

. . . (A 98)

This inmate's disorder,

although severe, seems

contrived and recently

learned. My final opinion,

based on observation of

Alvin Bernard Ford, on

examination of his environment,

and on the spontaneous comments

of group of prison staff,

is that the inmate does

comprehend his total situa

tion including being sentenced

to death, and all of the

implications of that penalty.

(A 100)

Dr. Mhatre's report to the

governor stated:

The conversation with the

guards at Florida State Prison

who have been working with

Mr. Ford, furnished the

6

following information. His

jibberish talk and bizarre

behavior started after all

his legal attempts failed.

He was then noted to throw

all his legal papers up in

the air and was depressed

for several days after that.

He especially became more

depressed after another inmate,

Mr. Sullivan, was put to death

and his behavior has rapidly

deteriorated since then. In

spite of this, Mr. Ford

continues to relate to other

inmates and with the guards

regarding his personal needs.

He has also borrowed books

from the library and has been

reading them on a daily basis.

A visit to his cell indicated

that it was neat, clean and

tidy and well organized . . .

It is my medical opinion that

Mr. Ford has been suffering

from psychosis with paranoia,

possibly as a result of the

stress of being incarcerated

and possible execution in the

near future. In spite of

psychosis, he has shown ability

to carry on day to day

activities, and relate to his

fellow inmates and guards,

and appears to understand

what is happening around him.

It is my medical opinion

7

that though Mr. Ford is

suffering from psychosis

at the present time, he has

enough cognitive function

ing to understand the nature

and the effects of the death

penalty, and why it is to

be imposed upon him. (A 103)

Dr. Afield concluded:

. . . Although this man

is severely disturbed, he

does understand the nature

of the death penalty that

he is facing, and is aware

that he is on death row

and may be electrocuted.

The bottom line, in summary

is, although sick, he does

know fully what can happen

to him. (A 105-106)

By signing a death warrant for

Ford on April 20, 1984, the governor

determined Ford was sane within the

meaning of Fla. Stat. §922.07(1).

Ten days prior to Ford's scheduled

May 31, 1984, execution, Ford's

counsel filed in the state trial

court a motion for hearing and

8

appointment of experts for a determina

tion of competency to be executed.

The motion was denied. The Florida

Supreme Court affirmed the trial

court's order. Ford v. Wainwright,

451 So.2d 471 (Fla. 1984). The

Florida Supreme Court held that the

gubernatorial proceeding outlined

in Fla. Stat. §922.07 is the

exclusive means for determining

competency to be executed and there was

no right to a judicial determination

(A 9-10).

Ford's counsel then filed his

second Petition for Writ of Habeas

Corpus in the United States District

Court, Southern District of Florida,

on May 25, 1984 (A 11-124). The

State filed a response (A 125-140).

The District Court heard legal

9

argument on May 29, 1984. At the

conclusion of the hearing, the court

announced its ruling orally. It found

the petition constituted an abuse of

the writ (A 164). Alternatively, on

the merits, the District Court ruled

the gubernatorial proceeding

under Fla. Stat. §922.07, was

properly followed and relief was

denied (A 164).

A divided panel of the United

States Court of Appeals for the

Eleventh Circuit granted a certificate

of probable cause and a stay of

execution on May 30, 1984. Ford v .

Strickland, 734 F.2d 538 (11th Cir.

1984). By a vote of 6-3, this Court

denied the State's motion to vacate

the stay. Wainwright v. Ford,

___U.S. ____, 104 S.Ct. 3498 (1984).

10

After a full briefing and oral

argument, a panel of the Eleventh

Circuit affirmed, by a 2-1 vote,

the District Court's order. Ford v .

Wainwright, 752 F.2d 526 (11th Cir.

1985). The majority held this Court's

opinion in Solesbee v. Balkcom,

339 U.S. 9 (1950), which had been

recently applied by a panel of the

Eleventh Circuit in Goode v .

Wainwright, 731 F.2d 1482 (11th Cir.

1984), was controlling. The portion

of Solesbee v, Balkcom, supra, quoted

by the Court of Appeal as dispositive,

states:

We are unable to say that

it offends due process

for a state to deem its

governor an 'apt and

special tribunal' to pass

upon a question so closely

related to powers that

from the beginning have

been entrusted to governors.

11

Id. at 12 (quoted at A 187).

Rehearing en banc was denied

(A 202-203). This Court granted

Ford's Petition for Certiorari on

December 9, 1985 (A 207).

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

12

I. The execution of Alvin Bernard

Ford, a state death row inmate who

has had over eleven years to challenge

his conviction, and whose sanity to

be executed has been determined by

Florida's governor pursuant to

Fla. Stat. §922.07 (1983), will not

offend the cruel and unusual punish

ment clause of the Eighth Amendment.

At common law, it was recognized

an insane man should not be executed,

as a matter of humanitarian principle.

This was not considered an individual

right, but rather, an appeal was

made to the discretion of the

tribunal having authority to post

pone sentence. Solesbee v. Balkcom,

339 U.S. 9 (1950) . Thus, the Framers

could not have intended that this

social policy be incorporated in the

Eighth Amendment as a fundamental

personal right.

Deferment of an insane man's

execution does not fall within the

scope of the Eighth Amendment for

several reasons. First, it operates

as a temporary reprieve only and

not as a permanent bar to execution,

unlike this Court's past interpreta

tion of the Eighth Amendment as

setting substantive limits on punish

ment. Second, there has never been

a single agreed-upon rationale under

lying the policy of postponing the

execution of an insane man, so there

is no compelling premise to support

Ford's argument that his execution

would offend the dignity of man.

13

Third, an examination of contemporary

standards as revealed by present state

statutes, confirms that the common

law view equating deferment of the

execution of the insane with clemency

is still accepted today. Finally,

this Court should not find an Eighth

Amendment right because post-conviction

insanity occurs at a stage outside

the criminal process after the

validity of the conviction and

sentence are no longer in dispute.

II. If this Court determines the

Eighth Amendment prohibits the

execution of the insane, the Florida

procedure outlined in Fla. Stat.

§922.07 (1983), adequately prevents

it. Ford was examined by an

appointed commission of three

psychiatrists who reported to the

14

governor their conclusion that he was

sane. Counsel for Ford was present

at the examination, and was permitted

to submit written material to the

commissioners and to the governor.

Ford is not entitled to a federal

habeas corpus evidentiary hearing to

determine his present sanity because

he is not challenging his conviction.

The function of habeas corpus is to

secure release from illegal custody.

The issue of post-conviction sanity

is outside the criminal process. Less

stringent procedural requirements

apply. The governor, acting as a

neutral and detached decisionmaker,

with the aid of psychiatrists, was

a proper party to make the determination

that Ford was sane for purposes of

15

execution.

Florida's standard of competency

to be executed is that a prisoner

understands the nature of the death

penalty and why it is to be imposed

upon him. This is an adequate

standard, for Ford has no further

right of access to the courts.

Ill. In Solesbee v. Balkcom,

339 U.S. 9 (1950), this Court upheld

a procedure like Florida's for

determining sanity to be executed as

comporting with due process. Solesbee

is still valid and it should be dis

positive of Ford's claim that Fla.

Stat. §922.07 fails to satisfy

procedural due process. Solesbee

held the determination of post

conviction insanity could be deemed

an executive function, akin to the

clemency authority. It has not been

16

overruled by Gardner v. Florida,

430 U.S. 349 (1977), because Gardner

deals with sentence imposition,

whereas the issue of competency to

be executed arises long after

sentencing and is not part of the

judicial process.

Due process is flexible and

what process is due depends upon

the situation. The Florida procedure

allows the governor to make the

determination of sanity to be executed,

subsequent to the receipt of reports

from a commission of appointed experts.

The procedure was followed in this

case and all three members of the

commission concluded Ford was sane.

The balancing test of Mathews v .

Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319 (1976) is

17

satisfied. Ford's private interest

is insubstantial because he has had

full review of his conviction. The

State has a valid and compelling

interest in an end to litigation.

The risk of error is minimized by

the Florida statute which provides

for experts to advise the governor.

To require an adversarial judicial

proceeding, subject to appellate

review, will invite endless litigation.

Solesbee v. Balkcom, supra, should

be reaffirmed by upholding the

Florida procedure for determining

competency to be executed.

18

19

ARGUMENT

I.

THE HUMANITARIAN POLICY

DEFERRING EXECUTION OF AN

INSANE PRISONER UNTIL HIS

SANITY IS RESTORED IS NOT

A FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT OF THE

INDIVIDUAL REQUIRING EIGHTH

AMENDMENT PROTECTION.

Alvin Bernard Ford murdered a

helpless, wounded police officer--

Dimitri Walter Ilyankoff--on July 21,

1974, by shooting him in the back

of the head at close range. He was

tried and sentenced to death. His

challenges to the validity of his

conviction and sentence were rejected

by the state and federal courts in

the ten year period following the

commission of the crime.

Although the legality of the

conviction is no longer at issue,

Ford's sentence has not been carried

out. His remaining challenge to

the State's right to execute him

is his assertion that the Eighth

Amendment proscribes the execution

of an insane person as "cruel and

unusual" punishment. Ford alleges

he is presently insane^" and the

Florida procedure for determining

sanity to be executed is inadequate

to satisfy the federal due process

standards which would inexorably

follow if the court accepts his

Eighth Amendment claim. The State

maintains the humanitarian principle

deferring execution of an insane

person is not a substantive Eighth

^This claim was never presented

to any court until ten days prior to

his scheduled 1984 execution, although

according to his pleadings, his mental

problems began in December, 1981.

20

Amendment right of the condemned.

21

Moreover, even if the court determines

there is such a right, the Florida

gubernatorial proceeding adequately

protects it.

The Florida procedure, which

was followed in this case, is outlined

in Fla. Stat. §922.07 (1983). When a

condemned prisoner's sanity is in

question, the governor appoints a

commission of three psychiatrists.

The commissioners are directed to

examine the prisoner and advise the

governor whether he understands the

nature of the death penalty and why

it is to be imposed upon him. In

this case, all three psychiatrists

reported to the governor that Ford

was sane within the meaning of the

statute. By signing Ford's death

warrant, the governor determined he

was sane for purposes of execution.

The present Florida procedure

reflects the common law policy. As

described in this Court's decision

in Solesbee v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9,

13 (1950), "the heart of the common

law doctrine has been that a suggestion

of insanity after sentence is an

appeal to the conscience and sound

wisdom of the particular tribunal

which is asked to postpone sentence."

Stated another way, it is "an appeal

to the humanity" of a tribunal to

postpone execution. People v. Preston,

345 111. 11, 177 N.E. 761 (1931);

People v. Eldred, 103 Colo. 334,

86 P .2d 248 (1938) . At common law,

a stay of execution due to insanity

was discretionary with the court

22

or the executive in the exercise of

23

clemency; there was no absolute right

to a hearing and no provision for

judicial review. People v. Riley,

37 Cal.2d 510, 235 P.2d 381, 384 (1951).

The decision to spare an insane

person from execution was not deemed

to be an individual right and the

Framers of the Constitution could

not have intended that it be included

within the "cruel and unusual"

punishment clause of the Eighth

Amendment. The primary concern of

the drafters of the Eighth Amendment

was to proscribe torture and other

barbarous methods of punishment.

Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97, 101

(1976). The "cruel and unusual

punishment" clause was taken from

the English Bill of Rights adopted

24

Oin 1689, and due to the prevailing

view that the clause only prohibited

certain methods of punishment, it was

rarely invoked throughout the

nineteenth century. Granucci, Nor

Cruel and Unusual Punishments Inflicted

The Original Meaning, 57 Cal.L.Rev.

839 (1969).

The fact that no court has ever

held execution of the insane to be

forbidden by the Eighth Amendment is

itself evidence that the Framers did

not so intend. The common law

prohibition against executing the

insane operates only as a temporary

reprieve; since the validity of the

original judgment and sentence is not

9See, J. Story, On the Constitu

tion of the United States, §1908 at

680 (3rd Ed. 1858), cited in Furman v .

Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 317 (1972).

at issue, the prisoner can be executed

once his sanity has been restored.

The postponement of an execution is

not within the scope of the Eighth

Amendment, which has always been

considered to be directed at the

method or kind of punishment imposed

for the violation of criminal

statutes. Powell v. Texas,

392 U.S. 514, 531-532 (1968). It

bans punishments that are barbaric

and excessive in relation to the

crime committed, Coker v. Georgia,

433 U.S. 584, 592 (1976), and imposes

substantive limits on what can be

made criminal and punished as such.

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153,

172 (1976), citing Robinson v .

California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962).

25

See also, Ingraham v. Wright,

26

430 U.S. 651. 667 (1977). To accept

Ford's position would not prevent

his eventual execution, but would

mean only that states cannot execute

condemned prisoners who are allegedly

insane until their sanity is restored.

Such a deferment of execution does

not merit Eighth Amendment protection,

and, in Florida, is properly left to

the governor.

Aside from the fact that the

issue before this Court is not one

which would fall within the traditional

purview of the Eighth Amendment, an

examination of the common law reasons

and those urged by Ford establishes

there is no consistently applied

rationale underlying the policy

27

against executing the insane. There

are various justifications which all

reflect humanitarian concerns and

are in the nature of clemency; these

justifications do not cancel the

punishment or suggest its imposition

was wrong.^ This general lack of

agreement supports the State's

position that the policy does not

create an Eighth Amendment right in

the individual, for how can execution

of the insane be said to offend the

concept of human dignity when there

is no consensus as to why this is so?

~̂Gray v. Lucas, 710 F.2d 1048,

1054 (5th Cir. 1983) [. . . the under

lying social principle . . . is unclear

and not the subject of general

agreement . . .]

^The following discussion of the

common law is based upon Hazard and

Louisell, Death, the State and the

Insane: Stay of Execution. 9 UCLA

L.Rev. 381 (1962).

3

Blackstone and Hale explained

the rule by saying if the prisoner

is sane he may urge some reason why

the sentence should not be carried

out. 4 Blackstone, Commentaries,

395-396 (13th Ed. 1800). Ford re

states this in contemporary terms as

access to the courts: a prisoner

must be competent to meaningfully

exercise his right of access to

collateral remedies. ̂ Ford

acknowledges he has fully availed

himself of his judicial remedies;

his pleadings allege his mental

28

The existence of this "right"

is questionable; this Court has held

there is no right to counsel to

pursue discretionary applications for

review, Ross v. Moffitt, 417 U.S. 600

(1974), and counsel's failure to file

such an application cannot constitute

the basis for a claim of ineffective

ness. Wainwright v. Torna,

455 U.S. 586 (1982).

incompetency began in December, 1981,

seven years after his trial. Every

conceivable claim which could be

advanced on Ford's behalf has been

raised. The filing of any further

collateral proceedings would be an

abuse of process and an abuse of the

writ. Rule 9(b), Rules Governing

28 U.S.C. §2254 proceedings. Ford

has no standing to assert the rights

of others on this issue. Fisher v .

United States, 425 U.S. 391 (1976).

Blackstone also stated that the

prisoner's insanity is itself

sufficient punishment, but this

is not convincing, for at common law

gMoreover, since collateral

proceedings review the conviction,

and it is constitutionally required

that a prisoner have been competent

at his trial, Dusky v. United States,

362 U.S. 402 (1960), the access to

the courts argument is not persuasive.

29

30

it was recognized that when the

prisoner regained his sanity he was

again subject to execution. This is

true today, for Fla. Stat, §922.07

(1983), provides that if a prisoner

is found insane, after treatment, he

may be restored to sanity and

executed.

Coke theorized the rule is one

of humanity--a refusal to take the

life of the unfortunate prisoner,

Coke, Third Institute 6 (1797). This

rationale has been characterized

thusly:

Is it not an inverted

humanitarianism that

deplores as barbarous the

capital punishment of those

who have become insane

after trial and conviction,

but accepts the capital

punishment for sane men,

a curious reasoning that

would free a man from

capital punishment only

31

if he is not in full

possession of his senses?

Phyle v. Duffy, 34 Cal.2d 144, 159,

208 P .2d 668, 676-77 (1949) (Traynor,

J., concurring).

Coke has also suggested there

is no deterrent value in executing

an insane person. Ford restates this

theory by alleging execution of the

insane is excessive for it does not

serve the penological justifications

of retribution and deterrence.

This argument concerns a societal

interest which does not create a

right in the prisoner, who is still

subject to execution upon restoration

to sanity. Furthermore, these

interests are served. Ford is to

be executed for murder, and his

execution should deter potential

murderers. The purpose of retribution

is to place value on the life of the

victim and it exists as an alternative

to private vengeance. Van den Haag,

In Defense of the Death Penalty: A

Legal-Practical-Moral Analysis,

14 Crim. L. Bull. 5 (1978). The

societal objective of retribution,

the enforcement of laws, matters

more than the individual wish and

is quite independent of it.

Van den Haag, Punishing Criminals

(1975). In light of the fact that

Ford's sanity has been determined

pursuant to Fla. Stat. §922.07 (1983)

the State has adequately protected

society.

The theological reason advanced

for the rule at common law is that

the condemned should be afforded one

last opportunity to make his peace

32

33

with God. The religious rationale

is difficult to assess in a judicial

proceeding, particularly in modern

society where there is no consensus

as to doctrine. Accordingly, Ford

restates this principle as an entitle

ment to face death and die with

dignity. He cites to studies which

describe the deaths of terminally ill

patients who are victims of circum

stances beyond their control. E,g.,

E. Kubler-Ross, On Death and Dying

(1969) ["in the following pages is

an attempt to summarize what we have

learned from our dying patients in

terms of coping mechanisms at the

time of a terminal illness", page 33]

The situation of a dying patient

cannot be analogized to Alvin Bernard

Ford's. Ford chose to place himself

34

on death row at the time he committed

murder and he has had many years to

ponder his fate.^ A death from ill

ness is not comparable to capital

punishment:

To be put to death because

one's fellow humans find

one unworthy to live is a

very different thing from

reading the end of one’s

journey naturally, as all

men must. To be condemned,

expelled from life by one's

fellows, makes death not a

natural event or a mis

fortune but a stigma of

final rejection. The

knowledge that one has been

found too odious to live is

bound to produce immense

anxiety. Threatened by

disease or danger, we

usually feel that death is in

an indecent hurry to overtake

us. We appeal to friends and

physicians to save us, to

Certainly, he has had far more

time than the few seconds he allowed

his unfortunate victim.

35

help delay it, and we expect

a comforting response. Death

is the common enemy, and it

calls forth human solidarity.

Not for the condemned man.

He is pushed across by the

rest of us.

Van den Haag, Punishing Criminals,

page 212 (1975).

Therefore, Ford has presented

no compelling justification to

support his claim that he has an

individual right, protected by the

Eighth Amendment's concept of human

dignity, to have a stay of execution

based on post-conviction insanity.

The arguments Ford has advanced as

to contemporary standards of decency

are based on the existence of state

laws which provide the insane are not

to be executed. The existence of

these laws does not ipso facto create

an Eighth Amendment right; an

36

examination of the process they

provide shows that in modern times,

as at common law, the determination

of post-sentence insanity is a matter

8for the executive or the prisoner's

custodianf to inquire into for

humanitarian reasons.

Georgia Code Ann,, §17-10-61;

N.Y. Corr. Law, §665 (1983 Supp.);

Md. Ann. Code, Art. 27 §75(c);

Mass. Gen. Laws Ann., Ch. 279 §62

(1984 Supp.).

Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann., §13-4021

(1982); Ark. Stat. Ann., §43-2622

(1977); Calif. Penal Code, §3701

(1979) ; Conn. Gen. Stat., §54-101

(1980) ; Kan. Stat., §22-4006 (Supp.

1981); Miss. Code Ann., §99-19-57

(1983 Supp.); Neb. Rev. Stat.,

§29-2537 (1979); Nev. Rev. Stat.,

§176.425 (1983); New Mex. Stat. Ann.,

§31-14-4 (1978); Ohio Rev. Code Ann.,

§2949.28 (1982 Supp.); Okla. Stat, Ann.,

§1005 (1983); Utah Code Ann.,

§77-19-13(1) (1982); Wyo. Stat.,

§7-13-901 (1984 Cum. Supp.).

37

In bringing the court's view to

bear on the subject, the State submits

Ford has failed to establish a right

under the Eighth Amendment. In

Spinkellink v. Wainwright., 578 F. 2d 582,

617-619 (1978), cert, denied,

440 U.S. 976 (1979), the defendant

argued that Florida's clemency

procedures must be governed by the

due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The Fifth Circuit

rejected the claim, finding the

clemency power vested exclusively

in the executive branch and it was

a discretionary decision, not the

business of judges. As authority,

the court cited Solesbee v. Balkcom,

339 U.S. 9 (1950), in which this

Court held the function of

determining post-conviction insanity

38

was properly vested in the state

governor. Like clemency, the fact

there is long-standing recognition

that the insane should not be executed

until their sanity is restored, see,

Gregg v, Georgia, 428 U.S. 153,

200 n. 50 (1976), does not suffice

to elevate the principle to a right

etched in constitutional stone. Just

as not all errors of state law in a

capital sentencing proceeding are

violative of the Eighth Amendment,

Barclay v. Florida, 463 U.S. 939 (1983),

the determination of post-conviction

sanity need not be viewed as an

Eighth Amendment right. As the court

noted in Rhodes v. Chapman, 452 U.S.

337, 351 (1981), the courts should

proceed cautiously in making Eighth

Amendment judgments because revisions

39

cannot be made (short of a constitu

tional amendment) in the light of

further experience.

This Court's conclusions cannot

be the subjective views of the judges

but should be formed by objective

factors such as history and the action

of state legislatures. Rhodes v .

Chapman, 452 U.S. 337, 346-47 (1981).

As the State has discussed, history

shows that the policy against

executing the insane is primarily

for humanitarian reasons and it is

not viewed as a right of the condemned

prisoner. The existing statutes of

the states provide for procedures

akin to the executive clemency function.

There are valid reasons for

distinguishing the determination of

post-conviction insanity from earlier

40

stages of the judicial process.

The State, when it prosecutes

someone for a crime, must prove the

defendant was sane at the time of

its commission, for sanity at the time

of the crime is an element of guilt

itself.̂ Likewise, sanity at the

time of trial is essential to an

effective defense, and trial must be

postponed if a defendant is in

competent . However, post-trial

insanity commencing after judgment

operates only to delay execution and

so it is not deserving of the same

^The court' s holding in Ake v.

Oklahoma, ___ U.S. ___, 105 S.Ct. 1090

(1985), that an indigent defendant

must have access to the psychiatric

assistance necessary to prepare an

effective defense at trial has no

bearing on the instant case, which

concerns post-conviction insanity.

41

protections afforded at the trial

stage. Comment, Execution of Insane

Persons, 23 So.Cal.L.Rev. 246 (1950).

In Roberts v. United States,

391 F .2d 991 (D.C. Cir. 1968), the

court was presented with a prisoner's

contention that due to his mental

condition he would not be able to

conform to prison regulations and

so he would not become eligible for

parole. He argued the prospect of a

long incarceration was, as to him,

cruel and unusual punishment for

bidden by the Eighth Amendment. The

court rejected the claim, noting

there is nothing unique in the

development of mental or emotional

disorders as a result of imprisonment.

Writing for the court, Circuit Judge

(now Chief Justice) Burger quoted

42

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 100

(1958) :

While the state has the

power to punish, the

[Eighth] Amendment stands

to assure that this power

be exercised within the

limits of civilized standards.

Fines, imprisonment and

even execution may be imposed,

depending on the enormity of

the crime, but any technique

outside the bounds of these

traditional penalties is

constitutionally suspect.

The court concluded that since the

case involved no technique "outside

the bounds of these traditional

penalties," the claim was without

merit. Roberts v. United States,

supra, at 992.

The present case, as did

Roberts, involves a penalty within

"traditional bounds" which has been

justly imposed. Ford's Eighth

Amendment claim of "right" to a

43

determination of post-conviction of

insanity must likewise be held to be

lacking in merit. "All that is good

is not commanded of the Constitution

and all that is bad is not forbidden

by it." Palmer v. Thompson,

403 U.S. 217, 228 (1971).

44

II.

SHOULD THE COURT FIND THERE

IS AN EIGHTH AMENDMENT

RIGHT TO BE SANE AT THE

TIME OF EXECUTION, THE

PRESENT FLORIDA PROCEDURE

ADEQUATELY PROTECTS IT.

If this Court does conclude there

is an Eighth Amendment right to be

sane at the time of execution, the

State maintains the procedures set

forth in Fla. Stat. §922.07 (1983),

adequately vindicate it. Ford

invoked the statutory procedure.

Three psychiatrists examined him,

and all three doctors reported to

the governor in writing that Ford

was competent to be executed, i,e .,

he understood the nature of the death

penalty and why it was to be imposed

upon him. Ford's counsel was allowed

to be present at the examination,

45

which, constitutionally is not even

required.^ There is absolutely

nothing in the statute to prevent

defense counsel from submitting any

pertinent material to the governor.

Ford excerpts a sentence from the

Florida Supreme Court's decision in

Goode v. Wainwright, 448 So.2d 999

(Fla. 1984), to support this portion

of his argument, but the opinion states

only, "He [Goode] complains about the

governor's publicly announced policy

of excluding all advocacy on the part

of the condemned from the process of

■^See, Smith v. Estelle,

602 F.2d 694, 708 (5th Cir. 1979);

vacated on other grounds but cited with

approval as to point that counsel not

entitled to be present at psychiatric

examination. Estelle v. Smith,

451 U.S. 454, 470, n. 14 (1981).

46

determining whether a person under

sentence of death is insane."

448 So.2d 999. In fact, Ford’s

counsel did prepare materials which

were submitted to and considered by

the commissioners (A 103, 105), and

he asserted in the District Court he

had been able to submit information

to rebut the conclusions of the

commissioners to the governor.

(A 75-76, n. 6). ["In the 922.07

proceeding before the governor,

counsel and Mr. Ford demonstrated

that the conclusions of the . . .

commission members . . . were flawed"].

Nevertheless, Ford insists he

is entitled to a federal evidentiary

determination of competency because

the Florida proceeding was not

conducted in a court and therefore

47

the presumption of correctness of

28 U.S.C. §2254(d) is inapplicable.

The State maintains a determination

of Ford's competency in a federal

habeas corpus proceeding would be

wholly inappropriate. Pursuant to

28 U.S.C. §2254(a) a person in custody

pursuant to a state court judgment

may apply for habeas corpus "only

on the ground that he is in custody

in violation of the Constitution . . .

of the United States." The federal

court's habeas corpus jurisdiction is

defined and limited by the statute.

Engle v. Issac, 456 U.S. 107, 110,

n. 1 (1982); Sumner v. Mata,

449 U.S. 539, n. 2 (1981). Section

2254 is "primarily a vehicle for

attack by a confined person on the

legality of his custody and the

48

traditional remedial scope of the

writ has been to secure absolute

release--either immediate or

conditional--from that custody."

Lee v. Winston, 718 F .2d 888, 892

(4th Cir. 1983). Ford is not attack

ing the validity of his judgment and

sentence or the lawfulness of the

Respondent's custody, since even

if there is a right not to be

executed while insane, once sanity

is restored, the execution can proceed.

The essence of habeas corpus is an

attack by a person in custody upon

the legality of that custody, and the

traditional function of the writ is

to secure release from illegal

custody. Preiser v. Rodriguez,

411 U.S. 475, 484 (1973). The sole

function of the writ is to grant

49

relief from unlawful imprisonment or

custody, and it cannot be used properly

for any other purpose. Hill v .

Johnson, 539 F.2d 439 (5th Cir. 1976);

Caldwell v. Line, 679 F.2d 494

(5th Cir. 1982); Delaney v. Giarrusso,

633 F .2d 1126, 1128 (5th Cir. 1981).

There is no universal right to litigate

a federal claim in a federal court;

the Constitution makes no such

guarantee. Allen v. MeCurry,

449 U.S. 90, 103-104 (1980); Stone

v. Powell, 428 U.S. 465 (1976).

The determination of sanity

to be executed is not a stage of the

criminal process, as a death-sentenced

prisoner is not subject to execution

until the criminal process has been

completed. Events which are not

critical stages of a criminal

50

proceeding are not subject to stringent

procedural requirements to vindicate

constitutional rights.

In Gerstein v. Pugh, 420 U.S. 103

(1975), this Court held that while the

Fourth Amendment requires a judicial

determination of probable cause as a

prerequisite to extended restraint of

liberty following arrest, full

adversary hearing safeguards were

not necessary. An informal procedure

could be used and appointment of

counsel was not required.

In Shadwick v. Tampa, 407 U.S. 345

(1972), this Court held municipal

court clerks qualified as neutral

and detached magistrates capable of

issuing arrest warrants for purposes

of the Fourth Amendment, and concluded

not all warrant authority must reside

51

exclusively in a lawyer or judge.

It has been determined the

Sixth Amendment right to counsel

attaches only when formal judicial

proceedings are initiated against

an individual. Kirby v. Illinois,

406 U.S. 682 (1982). Thus, prison

inmates closely confined in administra

tive detention while being investigated

for criminal activity were held not

to be entitled to the appointment of

counsel, for there is no Sixth Amend

ment right until adversary proceedings

are initiated. United States v .

Gouveia, ___ U.S. ___, 104 S.Ct. 2292

(1984). The right to counsel, once

it has attached, concludes after

direct appeal. A criminal defendant

has no right to counsel to pursue

discretionary applications for review,

52

Ross v. Moffitt, 417 U.S. 600 (1974),

and counsel's failure to file such an

application cannot constitute the

basis for a claim of ineffectiveness.

Wainwright v. Torna, 455 U.S. 586

(1982) .

Therefore, any Eighth Amendment

right Ford has to be sane when he is

executed can be addressed in a non

judicial setting, since the issue

arose after the criminal (and in this

case, extensive collateral) proceed

ings were completed. The decision

as to post-conviction sanity has

been properly vested by Florida in

the governor, for, as this Court

held in Solesbee v. Balkcom,

339 U.S. 9 (1950), the decision bears

a close affinity not to trial for

a crime but to clemency powers in

53

general. The Constitution is

satisfied because the decisionmaker

is a neutral and detached official.

Coolidge v. New Hampshire, 403 U.S. 443,

453 (1971). Therefore, Ford's argu

ments as to the applicability of

28 U.S.C. §2254(a) are not material

to the issue since there is no judicial

proceeding required under the

12Constitution.

Ford's additional argument that

the Florida competency standard is

inadequate because it does not require

that the prisoner be able to prepare

for death and consult with counsel is

12If this Court does find a

judicial proceeding is required, the

Florida courts, rather than the federal

District Court, should be given the

first opportunity to act. Cabana v.

Bullock, ___ U.S. ___, 54 U.S.L.W.

4105, 4109 (op. filed January 22,

1986).

54

a repeat of his death with dignity

and access to the courts arguments.

As the State has pointed out earlier,

Ford has litigated this case for years

and he has already exercised all his

rights of access to the courts.

Concerning the dubious nature of

Ford's claim to a right to prepare

for death, the State submits the

statute's requirement that the

condemned prisoner understand the

nature of the death penalty and why

it is to be imposed on him^4 satisfies

this purpose.

The competency standard asserted

by Ford is simply an invitation to

endless litigation. The legislature

~̂ See pages 33-35, supra.

14Fla. Stat. §922.07(1)

55

has wisely set a standard which is

appropriate to the situation and left

the determination to the governor.

The Florida statutory standard is the

standard cited in LaFave and Scott,

Handbook on Criminal Law (1972) at

page 303:

The common law was quite

vague on the meaning of

insane in this context

[time of execution], but

it is usually taken to

mean that the defendant

cannot be executed if he

is unaware of the fact that

he has been convicted and

that he is to be executed.

Stated another way, he

must be so unsound mentally

as to be incapable of

understanding the nature

and purpose of the

punishment about to be

executed upon him.

It is also the standard in at least

one other state, Illinois, where the

applicable statute, Illinois Rev.

Stat. (1982), Ch. 38, §1005-2-3(a),

56

provides:

A person is unfit to be

executed if because of a

mental condition he is

unable to understand the

nature and purpose of

such sentence.

The State maintains the Eighth

Amendment requires no more.

57

PURSUANT TO CONTROLLING

PRECEDENT OF THIS COURT,

SOLESBEE v. BALKCOM,

339 U.S. 9 (1950), FLORIDA'S

PROCEDURE FOR DETERMINING

SANITY OF CONDEMNED

PRISONERS MEETS THE REQUIRE

MENTS OF FOURTEENTH AMEND

MENT PROCEDURAL DUE PROCESS.

Ford argues in the alternative

that even if there is no Eighth

Amendment right to be sane at the time

of execution, Florida has created

such a right and its procedure for

protecting it fails to satisfy due

process. The State maintains this

Court's decision in Solesbee v .

Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9 (1950), wherein

it held a gubernatorial determination

of sanity to be executed satisfies

due process, is still good law and

should therefore be applied as

controlling precedent to reject Ford's

III.

58

contentions.

The decision in Solesbee was

preceded by Nobles v. Georgia,

168 U.S. 515 (1897). In Nobles, the

court held the question of insanity

after verdict did not give rise to

an absolute right to have the issue

tried before a judge and jury, but

was addressed to the discretion of

the judge. The court concluded the

manner in which the sanity question

was to be determined was purely a

matter of legislative regulation.

This decision led to Solesbee v .

Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9 (1950), where the

court held the Georgia procedure

whereby the governor determined the

sanity of an already convicted

defendant did not offend due process:

59

We are unable to say that

it offends due process for

a state to deem its governor

an "apt and special tribunal"

to pass upon a question so

closely related to powers

that from the beginning have

been entrusted to governors.

And here the governor had

the aid of physicians

specially trained in

appraising the elusive and

often deceptive symptoms of

insanity. It is true that

governors and physicians

might make errors of judgment.

But the search for truth

in this field is always

beset by difficulties that

may beget error. Even

judicial determination

of sanity might be wrong.

* * * * *

To protect itself society

must have power to try, con

vict, and execute sentences.

Our legal system demands

that this governmental duty

be performed with scrupulous

fairness to an accused. We

cannot say that it offends

due process to leave the

question of a convicted

person's sanity to the

solemn responsibility of

a state's highest executive

with authority to invoke

60

the aid of the most skill

ful class of experts on

the crucial questions

involved.

Id. at 12-13.

Solesbee was reaffirmed by this

Court's decision in Caritativo v .

California, 357 U.S. 549 (1958).

Ford argues Solesbee is no

longer valid because it was decided

at a time when the right/privilege

distinction was thought to be

determinative of an individual's

constitutional rights, a concept

which has since been rejected. See,

e.g., Graham v. Richardson,

403 U.S. 365, 374 (1971). However,

the thrust of the court's holding

in Solesbee was the determination

of post-conviction insanity could

properly be deemed an executive

function because it was akin to

61

clemency and it did not offend due

process for the governor, with the

aid of physicians, to make the

determination. The court's decision

did not turn on the right/privilege

distinction but on the authority

traditionally vested in the executive.

Its analysis was adopted in

Spinkellink v. Wainwright,

578 F .2d 582, 617-619 (5th Cir. 1978),

cert, denied, 440 U.S. 976 (1979).

There the court, which in addition

to Solesbee, cited Schick v, Reed,

419 U.S. 256 (1974) and Meachum v .

Fano, 427 U.S. 215 (1976), held that

where the governor and the cabinet,

pursuant to established procedures,

chose to consider whether the defendant

was entitled to mercy, there was no

Fourteenth Amendment due process

62

violation, for clemency is an

executive function. In the case

sub judice, it should be recognized

that enforcement of the law, like

clemency, is traditionally an executive

function. Accordingly, the governor,

who is charged with carrying out the

sentence by signing the warrant, is

the proper party to determine sanity

in this context.

Ford also argues the decision

in Gardner v, Florida, 430 U.S. 349

(1977), revisited Williams v. New York,

337 U.S. 241 (1949), and since

Solesbee cited to Williams, Solesbee

must be reevaluated as well. The

State maintains this Court's holding

in Gardner that the sentencing phase

of a capital murder trial, as well

as the phase on guilt or innocence,

63

must satisfy the requirements of the

due process clause, does not call

into question the continued validity

of Solesbee. In both Williams and

Gardner, the court was concerned with

the imposition of sentence. As Justice

White noted, concurring in Gardner,

"The issue in this case . . . involves

the procedure employed by the state in

selecting persons who will receive

the death penalty." Gardner v .

Florida, supra, 430 U.S. at 363. By

contrast, Solesbee dealt with the

determination of post-sentence

insanity, which is not part of the

judicial process, and it is done

subsequent to the imposition of

sentence. It is a discretionary

stage with which, as stated in

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 199

64

[, . . "a defendant who is convicted

and sentenced to die may have his

sentence commuted by the governor . . .

The existence of these discretionary

stages is not determinative of the

issues before us . . . Nothing in any

of our cases suggests that the decision

to afford an individual defendant

mercy violates the Constitution."]

Therefore, since Fla. Stat. §922.07

(1983) is not part of the sentence

imposition or process, pursuant to

this Court's still controlling

decision in Solesbee, it satisfies

due process.

Ford's argument that Florida

has created a right and it is subject

to procedural due process protections

is a restatement, in different terms,

(1976), the courts are not concerned.

65

of his contention that Solesbee v .

Balkeom is no longer valid, since

under Solesbee, Fla. Stat. §922.07

(1983), does satisfy due process.

The State therefore reiterates its

position that Solesbee is dispositive.

In any event, if the State is

free to define and limit an entitle

ment, there seems no good reason why

it should not be equally free to define

the procedure that goes with that

entitlement. Tribe, American

Constitutional Law, page 536 (1978).

An examination of Fla. Stat. §922.07

(1983), reveals that the statute does

no more than provide that the prisoner

^Goode v. Wainwright, 731 F .2d

1482, 1483 (1984),Lthe Eleventh

Circuit, citing Solesbee, held the

Florida statute meets the minimum

standards required by procedural

due process.]

66

or someone on his behalf may inform

the governor of his alleged insanity.

This procedure has superseded the

earlier Florida decisions which held

an application to the trial court may

be made for a determination of sanity.

Ford v. Wainwright, 451 So.2d 471,

475 (Fla. 1984). The only expectation

that has been created by first the

common law and then the statute is

the opportunity to petition for a

sanity determination.

Ford's argument that he is

entitled to the same due process

protections that are applicable to

a determination of competency to

stand trial ignores the qualitative

and obvious distinctions between the

trial on guilt or innocence and a

last-ditch attempt to avoid execution

67

many years later after all other legal

efforts have failed. At trial,

competency is necessary to ensure the

effectiveness of the fundamental rights

inherent therein such as the right to

counsel, to confront and cross-examine

witnesses, the decision whether to

testify, etc. In short, as a matter

of Fourteenth Amendment fundamental

fairness, an accused must be competent

at trial so he will be able to

participate meaningfully in the

judicial proceeding in which his life

is at stake. Pate v. Robinson,

383 U.S. 375 (1966); Ake v. Oklahoma,

___ U.S. ___, 105 S.Ct. 1087, 1093

(1985). It is appropriate that the

court before whom he is to be tried

determines his competency to stand

trial.

68

By contrast, at the time of

execution, the prisoner has exhausted

his remedies and has no further

avenues of relief. It is well

established, as the phrase implies,

that "due process" is flexible and

calls for such procedural protections

as the particular situation demands;

not all situations calling for

procedural safeguards require the

same kind of procedure. Morrissey v .

Brewer, 408 U.S. 471, 481 (1972);

see also, Hewitt v. Helms, 459 U.S. 460

(1983). In the instant case, the

statutory procedure which provides

for the appointment of a commission

of experts, an examination at which

counsel for the prisoner may be

present, and a submission of a report

to the governor, is sufficient.

69

Due process does not always

require an adversarial hearing.

Williams v. Wallis, 734 F.2d 1434,

1438 (11th Cir. 1984); Hickey v. Morris,

722 F .2d 543, 549 (9th Cir. 1983).

In Hortonville Joint School District

No. 1 v. Hortonville Education

Association, 426 U.S. 482 (1976), the

court held that where the state law

vested a governmental function in the

school board and had an interest in it

remaining there, the school board's

review of teacher firing decisions

satisfied due process. The court

further noted there is a presumption

of honesty and integrity in policy

makers with decisionmaking power.

Id. at 497. Likewise in this case

the legislature has enacted a

statutory procedure which vests the

70

determination of sanity to be executed

in the governor, subsequent to the

receipt of a report from a commission

of experts, and there is a presumption

the executive has acted with integrity.

This presumption is well founded in

the instant case, for the commission

appointed by the governor unanimously

concluded Ford was sane.

Counsel for Ford and for amici

criticize the fact that the mental

examination was just for a half-hour

period and contend this was insufficient

to make an accurate diagnosis. They

appear to ignore the facts that the

commissioners also spoke to prison

personnel who had daily contact with

Ford, reviewed his prison medical

records, observed the condition of

his cell, and considered material

71

submitted by Ford's attorneys, which

included reports by Doctors Kaufman

and Amin (A 98-106).16 The three

psychiatrists drew the conclusion

that Ford understood the nature of

the death penalty and why it was to

be imposed upon him and reported this

to the governor in writing.

16For example, Dr. Afield's

report states: "I had an in depth

conference with both attorneys for

the inmate and reviewed the medical

records that they had available. I

talked at length with a variety of

guards who had dealings with the

inmate and reviewed the contents of

Mr. Ford's writings in his cell. I

discussed his medical condition with

the prison psychiatrist and examined

the man in the presence of all counsels

and two other state-appointed

psychiatrists. My examination con

sisted of a complete mental status

examination. Subsequently, I spoke

at length with attorney Burr and

reviewed complete medical records from

the prison, which included psychiatric

evaluations and reports from several

prison psychologists. I reviewed in

depth Dr. Kaufman's findings."

72

In Barefoot v. Estelle,

463 U.S. 880 (1983), this Court

refused to accept the view propounded

by the American Psychiatric Association

that experts cannot accurately predict

the future dangerousness of a convicted

criminal. The court noted there were

doctors who disagreed with this

position and would be quite willing

to testify on the matter at a

sentencing proceeding. Id., 463 U.S.

899. In this case, three doctors

followed the Florida procedure for

determining competency to be executed

and were able to make a diagnosis.

In Barefoot, this Court additionally

concluded that psychiatric testimony

on future dangerousness need not be

based on personal examination and may

be given in response to hypothetical

73

questions. Therefore, in the instant

case, the methodology used, which

included a mental examination, did

not violate due process.

Further evidence that the

Florida procedure provides for

accurate fact finding is available

from the case of Gary Eldon Alvord.

a death row inmate who invoked

Fla, Stat. §922.07 (1983), in

November, 1984. In Alvord's case,

the governor appointed two of the

same three commissioners who had

examined Ford, Doctors Ivory and

Mhatre, to examine Alvord.

(Respondent's Appendix 1-4). Based

on their reports, the governor

determined Alvord was insane and

committed him for treatment.

(Respondent's Appendix 5-7).

74

Florida's statutory procedure

therefore satisfies the three-part

balancing test of Mathews v. Eldridge,

424 U.S. 319 (1976). At this point in

the proceeding--post trial, post appeal,

and post collateral attack, Ford's

private interest is insubstantial.

He has had many years to prepare for

death, and he is not entitled to

further access to the courts to

attack his conviction.

The State has a valid and

compelling interest in an end to

litigation and the carrying out of

its lawfully imposed sentence. In

the present case, the District Court

found Ford’s habeas corpus petition

to be an abuse of the writ (A 164),

as did the dissenting judge on the

Eleventh Circuit’s stay panel

75

(A 179). Ford's pleadings allege

his mental deterioration began in

December, 1981, yet he never sought

treatment, nor did he bring the matter

of his alleged insanity to any court

until ten days prior to his scheduled

1984 execution (A 4). The Florida

statutory procedure prevents such

abuses, for by permitting the governor

to be the decisionmaker with the aid

of an appointed commission of

psychiatrists, eleventh hour post

ponements of executions will not be

obtained by frivolous claims of

incompetence.

The risk of an erroneous depriva

tion is negligible since the statute

provides for experts to advise the

"^The merits panel did not reach

the issue (A 184, n. 1).

76

governor. in Williams v. Wallis,

734 F .2d 1434 (11th Cir. 1984), the

court upheld Alabama's nonadversary

procedures for determining whether

insanity acquitees should be released

from state mental hospitals, noting

that medical professionals have no

bias against release and it can be

safely assumed they are disinterested

decisionmakers. The court stated

"neither judges nor administrative

hearing officers are better qualified

than psychiatrists to render

psychiatric judgments" [ ] . Id. at

1439.

In Gilmore v. Utah, 429 U.S. 1012

(1976), the court terminated a stay

of execution, after reviewing state

records, having concluded "the State's

determinations of his [Gilmore's]

77

competence knowingly and intelligently

to waive any and all such rights were

firmly grounded." The concurring

opinion pointed out that the state

determinations were based on reports

of doctors ordered by the court to

examine Gilmore prior to his trial

and reports of prison psychiatrists

who had seen him after his conviction.

Id. at 429 U.S. 1015, n. 5. Since

in Gilmore the court was willing to

accept state determinations of

competency in a situation where the

prisoner was waiving his appellate

rights less than five months after

committing his crimes, it does not

offend due process to allow a state

governor, aided by a commission of

experts to determine competency to

be executed many years later.

78

See also, Board of Curators of the

University of Missouri v. Horowitz,

435 U.S. 78 (1978) [dismissal of

student for academic reasons requires

expert evaluation and is not readily

adapted to the procedural tools of

judicial or administrative decision

making.] Accordingly, in this case

where pursuant to Fla. Stat. §922.07

a commission of three psychiatrists

examined the Petitioner, found him

sane, so advised the governor, and

the governor thereupon issued a death

warrant, a proper balance was struck.

To accept amici 1s and Ford's

contention that due process requires

the State to provide full adversarial

judicial proceedings, subject to

appellate review, is to invite never-

ending litigation. Ford's execution

79

was stayed on May 30, 1984. By the

time this case is resolved, two more

years will have gone by. The concern

expressed by this Court long ago in

Nobles v. Georgia, 168 U.S. 398,

405-406 (1897), is just as valid

today:

If it were true that at

common law a suggestion

of insanity after sentence

created on the part of a

convict an absolute right

to a trial of this issue

. . . it would be wholly

at the will of the convict

to suffer any punishment

whatever, for the

necessity of his doing

so would depend solely

upon his fecundity

in making suggestion after

suggestion of insanity,

to be followed by trial

upon trial.

The State urges this Court to re

affirm Solesbee v. Balkcom, supra,

by holding that the Florida procedure

for determining competency to be

80

executed satisfies procedural due

process.

81

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, based on the foregoing

reasons and authorities, the

Respondent respectfully requests

that the decision of the Circuit

Court of Appeals for the Eleventh

Circuit be affirmed.

JIM SMITH

Attorney General

JOY B. SHEARER

Assistant Attorney General

111 Georgia Avenue

Room 204

West Palm Beach, FL 33401

(305) 837-5062

Counsel for Respondent

APPENDIX

A-l

STATE OF FLORIDA

OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR

EXECUTIVE ORDER NUMBER 84-214

(Commission to Determine Mental

Competency of Inmate)

WHEREAS, the Governor has been

informed that GARY ELDON ALVORD, an

inmate at Florida State Prison, under

sentence of death, may be insane, and

WHEREAS, pursuant to Section

922.07, Florida Statutes, it is

necessary to appoint a Commission of

three competent, disinterested

psychiatrists to inquire into the

mental condition of the aforesaid

inmate, and to suspend the execution

of the death sentence imposed upon

said inmate during the course of the

medical examination;

NOW, THEREFORE, I, BOB GRAHAM,

as Governor of the State of Florida,

by virtue of the authority vested in

me by the Constitution and Laws of the

State of Florida, specifically Section

922.07, Florida Statutes, do hereby

promulgate the following Executive

Order, effective immediately:

1. The following persons, who

are competent, disinterested

psychiatrists, are hereby appointed

as a Commission to examine the mental

condition of GARY ELDON ALVORD, an

inmate at Florida State Prison,

pursuant to Section 922.07, Florida

Statutes:

1. Peter B.C.B. Ivory, M.D.

2. Gilbert N. Ferris, M.D.

3. Dr. Umesh M. Mhatre

2. The above-named psychiatrists

as and constituting the "Commission

to Determine the Mental Condition of

GARY ELDON ALVORD" shall examine

GARY ELDON ALVORD to determine whether

he understands the nature and effect

of the death penalty and why it is

to be imposed upon him as required by

Section 922.07. The examination

shall take place with all three

psychiatrists present at the same

time. Counsel for the inmate and the

State Attorney may be present but

shall not participate in the examina

tion in any adversarial manner.

3. The psychiatric examination

shall be conducted expeditiously.

Upon completion of the examination,

said Commission shall report to me

their findings.