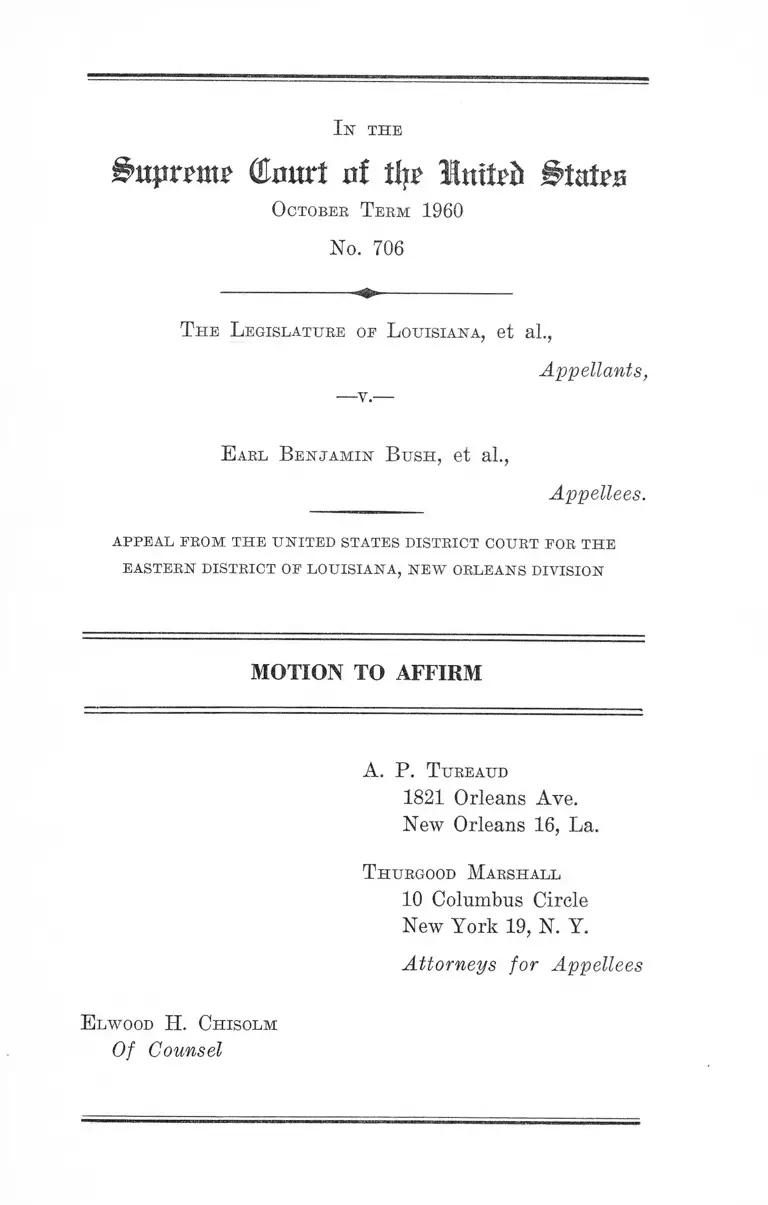

The Legislature of Louisiana v. Earl Benjamin Bush Motion to Affirm

Public Court Documents

December 21, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. The Legislature of Louisiana v. Earl Benjamin Bush Motion to Affirm, 1960. 634a4bc2-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8955e0e5-d701-4ce4-9883-a8e1a55ce4bb/the-legislature-of-louisiana-v-earl-benjamin-bush-motion-to-affirm. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

I n THE

ii’tfprm? OInurt nf tlf? UnttTft States

O ctober T eem 1960

No. 706

T h e L egislature oe L ouisiana, et al.,

Appellants,

E arl B e n ja m in B u sh , et al.,

Appellees.

a p p e a l p r o m t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s d i s t r i c t c o u r t f o r t h e

EASTERN DISTRICT OF L O U ISIA N A , N E W ORLEANS DIVISION

MOTION TO AFFIRM

A. P. T ureaud

1821 Orleans Ave.

New Orleans 16, La.

T hurgood M arshall

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellees

E lwood H . Chisolm

Of Counsel

I n t h e

Qlatirt of tlj£ Unttefc

O ctobee T eem 1960

No. 706

T he L egislature oe L ouisiana, et al.,

Appellants,

E ael B e n ja m in B u sh , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTRICT COURT FOR TH E

EASTERN DISTRICT OF L O U ISIA N A , N E W ORLEANS DIVISION

MOTION TO AFFIRM

Appellees move to affirm the judgments below on the

ground that the questions presented are so unsubstantial

as not to need further argument.

Opinions Below

Neither the opinion filed November 30, 1960, nor the

one issued December 21, 1960, is reported. The former,

however, was printed by appellants (Appx. A, pp. 26-50)

and the latter is appended by appellees {infra, p. la et

seq.).

2

Questions Presented

For the purposes of this motion, appellees adopt the

“ Questions” as presented by appellants at pages 3-5 of

the Jurisdictional Statement.

Statement of the Case

Though it contains a description of the several proceed

ings and the rulings in the court below, the statement

of the case given by appellants at pages 5-12 of the Juris

dictional Statement omits many facts material to consid

eration of the questions presented and includes, partic

ularly in the last three paragraphs, much that is more argu

ment than exposition. Nevertheless, appellees will not

burden the Court with a counter-statement inasmuch as

the omissions are covered in the opinions below and the

statements on file here in Orleans Parish School Board

v. Bush, 5 L. ed. 2d 36; United States v. Louisiana, 5 L. ed.

2d 245; Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, No. 589,

October Term 1960; Id., No. 612, October Term 1960.

Reasons for Granting the Motion

This latest appeal in the New Orleans school desegre

gation litigation brings into focus two attempts of the

Louisiana Legislature to “war against the Constitution.”

As such, the questions urged have been so plainly fore

closed by decisions of this Court and the court below so

manifestly decided them correctly that further argument

is unnecessary. See United States v. Louisiana, 5 L. ed. 2d

245; Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 5 L. ed. 2d 36;

Fauhus v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197, affirming 173 F. Supp. 944

(E.D. Ark. 1959); Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 16-19. See

3

also James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E.D. Va. 1959),

appeal dismissed 359 U.S. 1006; James v. Duckworth, 170

F. Supp. 342 (E.D. Va, 1959), affirmed 267 F. 2d 224 (4th

Cir. 1959), cert, denied 358 U.S. 829; Orleans Parish School

Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156 (5th Cir. 1957), cert, denied

354 U.S. 921. Cf. Riggs v. Johnson, 6 Wall. 166, 195 ; United

States v. Peters, 5 Cranch. 115, 136.

Despite the vigor of those decisions, appellants earnestly

argue that three of the eight “ questions presented” are

so substantial as to require plenary consideration. They,

in turn, have been converted into the following claims : one,

“ that the district court was without jurisdiction or power

to enjoin the Legislature of Louisiana or to interfere with

the state’s control over its local affairs and the exercise of

its [police] power;” two, “ that the United States has no

right to appear as amicus curiae for the purpose of insti

tuting action for further relief;” and three, that “ the

suits of the Louisiana plaintiffs against the state, without

its consent, should be dismissed as in violation of the 11th

Amendment” (Juris. Statement, p. 20).

None of these claims, appellants submit, has such sub

stantiality that this case ought to be held for further

argument.

1. Whatever its merit in the abstract, the lack of merit

in the first claim is demonstrated at the outset by the legis

lation which these appellants were enjoined from enforcing.

By Act No. 17 of the First Extraordinary Session (Appel

lants’ Appx. D, p. 22) and its reenactment in Act No. 2

of the Second Extraordinary Session {Id., p. 55) plus the

laws and resolutions by which they implemented those

Acts (see, e.g., Id., pp. 39, 42, 45, 48, 52, 54), the Legisla

ture and its individual members reserved to itself and

undertook to exercise “ all administrative authority” for

4

the maintenance and operation of the New Orleans public

school system.

Therefore, as the District Court said (Appellants’ Appx.

A, pp. 31-32),

there is no merit in the claim of “ legislative immunity”

put forward on behalf of the committee of the Legis

lature and its members who are sought to be enjoined

from enforcing measures which grant them control of

the New Orleans public schools. The argument is

specious. There is no effort to restrain the Louisiana

Legislature as a whole, or any individual legislator,

in the performance of a legislative function. It is only

insofar as the lawmakers purport to act as admin

istrators of the local schools that they, as well as

others concerned, are sought to be restrained from

implementing measures which are alleged to violate

the Constitution. Having found a statute unconstitu

tional, it is elementary that a court has power to en

join all those charged with its execution. Normally,

these are officers of the executive branch, but when the

legislature itself seeks to act as executor of its own

laws, then, quite obviously, it is no longer legislating

and is no more immune from process than the admin

istrative officials it supersedes. As Chief Justice Mar

shall said in Marburg v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch)

137, 170; “ It is not by the office of the person to whom

the writ is directed, but the nature of the thing to be

done, that the propriety or impropriety of issuing (an

injunction) is to be determined.”

See also the December 21, 1960 opinion of the court below

(Appellees’ Appx., at pp. la -lla ). Cf. Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1, 1619; Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 346-347;

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313, 318; Riggs v. Johnson,

5

6 Wall. 166, 195; United States v. Peters, 5 Cranch 115,

136.1

2. Appellants’ second claim, in effect, challenges the

jurisdiction of the District Court to entertain—and issue

an injunction upon—the amicus petition filed by the United

States in connection with the proceedings which culminated

in the opinion and judgment of December 21, 1960. Ap

pellees say that this contention also lacks merit.

The inherent authority of the District Court to call upon

the law officers of the United States for assistance to pro

tect the integrity of the judicial process and maintain

the due administration of justice is so settled as to require

no further argument. See, Universal Oil Co. v. Root Re

fining Co., 328 U.S. 575, 580, 581; Hazel-Atlas Glass Co.

v. Hartford Empire Co., 322 U.S. 238, 246; Faubus v.

United States, 254 F. 2d 797 (8th Cir. 1958), cert, denied

358 U.S. 829; Kasper v. Brittain, 245 F. 2d 97 (6th Cir.

1957). And see The Exchange, 7 Cranch 116, 118-119;

Northern Securities Co. v. United States, 191 U.S. 555, 556;

Howard v. Illinois Central R. Co., 207 U.S. 463, 490; A. B.

Dick Co. v. Marr, 197 F. 2d 498, 502, cert, denied 344 U.S.

905.

In addition, the District Court had authority to entertain

the amicus petition of the United States for an injunction

against appellants as an exercise of its ancillary jurisdic

tion to effectuate its orders and prevent them from being

frustrated. 28 U.S.C.A. §1651. See Local Loan Co. v.

Hunt, 292 U.S. 234, 239; Julian v. Central Trust Co., 193

U.S. 93, 112; Root v. Woolworth, 150 U.S. 401, 410-413;

Steelman v. All Continent Corp., 301 U.S. 278, 288-289;

1 For further enlightenment on the role of the Pennsylvania

legislature in this historic controversy, see Mr. Justice Douglas,

“ United States v. Peters, 5 Cranch 115,” 19 F.R.D. 185 passim.

6

Dugas v. American Surety Co., 300 U.S. 414, 428; Looney

v. Eastern Texas Railroad Co., 247 U.S. 214, 221.

Furthermore, the authority given the Attorney General

of the United States and United States Attorneys by

statutes such as 5 U.S.C.A. §§ 306, 309, 316, is obviously

not limited to cases in which the Government is a formal

party. See Booth v. Fletcher, 101 F. 2d 676, 681-682 (D.C.

Cir. 1938). See also Florida v. Georgia, 17 How. 478, 492-

495. For these statutes grant the Government’s law officers

broad power to initiate proceedings to safeguard national

interests. See United States v. California, 332 U.S. 19, 27;

Sanitary District of Chicago- v. United States, 266 U.S. 405,

425-426; Kern River Co. v. United States, 257 U.S. 147, 154-

155; United States v. San Jacinto Tin Co., 125 U.S. 273,

278-280, 284-285; United States v. Throckmorton, 98 U.S.

61, 70; Vitamin Technologists, Inc. v. Wisconsin Alumni

Research Foundation, 146 F. 2d 941, 946 (9th Cir. 1945).

Finally, the authority of the United States to intervene

as amicus curiae in this action is not limited by the fact

that it does not involve a property interest of the Govern

ment. See In re Dels, 158 U.S. 564, 584; United States v.

American Bell Telephone Co., 128 U.S. 315, 357-358, 367-

368; United States v. United States Fidelity d Guaranty

Co., 106 F. 2d 804, 807 (10th Cir. 1939), reversed on other

grounds 309 U.S. 506.

Accordingly, the right of the United States to appear as

amicus curiae in the proceedings below and the jurisdic

tion of the District Court to grant an injunction on its

petition are beyond dispute.2

2 Even if the cases looked the other way, appellants were not

prejudiced inasmuch as they concede that appellees “also filed a

petition for preliminary injunction against all defendants from

enforcing the provisions of the same Acts of the Legislature”

(Juris. Statement, p. 9). Such admission would also appear to

make a determination of this claim unnecessary.

7

3. The third claim pressed by appellants attempts to

resuscitate the Eleventh Amendment argument previously

held to be without merit in Orleans Parish School Board v.

Bush, 242 F. 2d 156, 160-161 (5th Cir. 1957), cert, denied

354 U.S. 921 and School Board of City of Charlottesville

v. Allen, 240 F. 2d 59, 62-63 (4th Cir. 1956).

Moreover, although appellants seem to be unaware of it,

the difference between using the injunctive power of fed

eral courts to direct the exercise of discretion by state

officers the situation where the Eleventh Amendment is

applicable—and using it to enjoin violation of constitu

tional rights under authority of state office—where, as

here, that Amendment does not apply—was definitively

settled in Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123. Therefore, the

District Court’s refusal to dismiss the complaints and peti

tions filed in the several proceedings brought up on this

appeal follows an unbroken course of decisions in this

Court for over fifty years. See, e.g., Lane v. Watts, 234

U.S. 525,̂ 540; Truax v. Raich, 239 U.S. 33; Sterling v.

Constantin, 287 U.S. 378, 393, and cases cited therein;

Georgia R. & Big. Co. v. Redwine, 342 U.S. 299, 303-306

and cases cited therein.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the questions presented by

appellants are manifestly unsubstantial and this motion

to affirm should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

A. P. T ureaitd

T hurgood M arshall

Attorneys for Appellees

E lwood H . Chisolm

Of Counsel

la

APPENDIX

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

E astern D istrict or L ouisiana

N ew O rleans D ivision

No. 3630— Civil Action

E arl B e n ja m in B u sh , et al.,

Plaintiffs,

versus

Orleans P arish S chool B oard, et al.,

Defendants.

A. P. Tureaud

Attorney for Plaintiffs

M. Hepburn Many, United States Attorney

Attorney for United States of America, Amicus

Curiae

Samuel I. Rosenberg

Attorney for Orleans Parish School Board, Board

Members Lloyd Rittiner, Louis G. Riecke, Matthew

R. Sutherland and Theodore H. Shepherd, Jr., and

Dr. James P. Redmond, Superintendent of Orleans

Parish Schools

Jack P. F. Gremillion, Louisiana Attorney General

Michael E. Culligan, Assistant Attorney General

John E. Jackson, Jr., Assistant Attorney General

Weldon Cousins, Assistant Attorney General

Henry Roberts, Assistant Attorney General

Attorneys for Jack P. F. Gremillion as Louisiana

Attorney General, A. P. Tugwell as State Treas-

2a

urer, Shelby M. Jackson as State Superintendent

of Education, Members of the State Board of

Education, and Boy M. Theriot as State Comp

troller

Monroe & Lemann

J. Baburn Monroe

Attorneys for the Whitney National Bank of New

Orleans

Phelps, Dunbar, Marks, Claverie & Sims

Louis B. Claverie

Attorneys for the Hibernia National Bank in New

Orleans

Sehrt & Boyle

Clem H. Sehrt

Attorneys for the National ■ American Bank of

New Orleans

Jones, Walker, Waechter, Poitevent, Carr ere & Denegre

George Denegre

Attorneys for the National Bank of Commerce in

New Orleans

Alvin J. Liska, New Orleans City Attorney

Joseph Hurndon, Assistant City Attorney

Ernest L. Salatich, Assistant City Attorney

Attorneys for the City of New Orleans

W. Scott Wilkinson

Gibson Tucker, Jr.

Attorneys for Edward LeBreton and Seven Others

Constituting the Committee of Eight of the Legis

lature of Louisiana

B ives, Circuit Judge, and Christenberey and W righ t , Dis

trict Judges;

3a

In these proceedings, we consider again1 * * * * * the progress of

desegregation in the public schools of the Parish of Orleans

and the additional efforts made to interfere with that

achievement. Because of what has been said and done by

the government of Louisiana in all its branches, it becomes

necessary to restate the fundamental principles that gov

1 The Orleans Parish school desegregation controversy has been

in the federal courts for eight years.

In 1954, the state adopted a constitutional amendment and two

segregation statutes. The amendment and Act 555 purported to re

establish the existing state law requiring segregated schools. Act

556 provided for assignment of pupils by the school superintendent.

On February 15, 1956, this court held that both the amendment

and the two statutes were invalid. The court issued a decree en

joining the School Board, “ its agents, its servants, its employees,

their successors in office, and those in concert with them who shall

receive notice of this order” from requiring and permitting segre

gation in the New Orleans schools. Bush v. Orleans Parish School

Board, 138 F. Supp. 336, 337, aff’d, 242 F. 2d 156, cert, denied,

354 U.S. 921.

Not only was there no compliance with that order, but immedi

ately thereafter the Legislature produced a new package of laws,

in particular Act 319 (1956) which purported to “freeze” the

existing racial status of public schools in Orleans Parish and to

reserve to the Legislature the power of racial reclassification of

schools. On July 1, 1956, this court refused to accept the School

Board’s contention that Act 319 had relieved the Board of its

responsibility to obey the desegregation order. In the words of

the court, “any legal artifice, however cleverly contrived, which

would circumvent this ruling [of the Supreme Court, in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483] and others predicated on it, is

unconstitutional on its face. Such an artifice is the statute in suit,”

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 163 F. Supp. 701, aff’d, 268

F. 2d 78. See also, Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268.

Nevertheless, the Legislature continued to contrive circumventive

artifices.

In 1958 a third group of segregation laws was enacted, including

Act 256, which empowered the Governor to close any school under

court order to desegregate, as well as any other school in the system.

In the first court test of this law7 it was struck down as unconsti

tutional by this court on August 27, 1960. Bush v. Orleans Parish

School Board, 187 F. Supp. 42.

On July 15, 1959, the court ordered the New Orleans School

Board to present a plan for desegregation, Bush v. Orleans Parish

School Board, No. 3630, but there was no compliance. Therefore,

4a

ern this controversy. Under the circumstances, they can

not be declared too often or too emphatically. These prin

ciples are:

1. That equality of opportunity to education through

access to non-segregated public schools is a right secured

by the Constitution of the United States to all citizens

regardless of race or color against state interference.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347, U.S. 483.

2. That, accordingly, every citizen of the United States,

by virtue of his citizenship, is bound to respect this con-

on May 16, 1960, the court itself formulated a plan and ordered

desegregation to begin with the first grade level in the fall of 1960.

For the fourth time, in its 1960 session, the Legislature produced

a packet of segregation measures, this time to prevent compliance

with the order of May 16, 1960. Four of these 1960 measures—

Acts 333, 495, 496 and 542—and the three earlier acts referred to

above—Act 555 of 1954, Act 319 of 1956 and Act 256 of 1958—

were declared unconstitutional by a three judge court on August

27, 1960, in the combined cases of Bush v. Orleans Parish School

Board and Williams v. Davis, and their enforcement by “ the Honor

able Jimmie H. Davis, Governor of the State of Louisiana, and all

those persons acting in concert with him, or at his direction, in

cluding the defendant, James F. Redmond,” was enjoined. Bush

v. Orleans Parish School Board, 187 F. Supp. 42, 45. At the same

time, the effective date of the desegregation order was postponed

to November 14, 1960.

Again, at the First Extraordinary Session of 1960, the Louisiana

Legislature adopted a series of measures designed to thwart the

orders of this court. Even after integration was an accomplished

fact, the Legislature sought to defeat it. On November 30, 1960,

this court held Acts numbered 2, 10 through 14, and 16 through 23,

as well as House Concurrent Resolutions Nos, 10, 17, 18, 19 and 23,

unconstitutional. Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, —— F.

Supp.------ (Nov. 30, 1960).

Undeterred, in its Second Extraordinary Session for 1960, the

Louisiana Legislature passed the measures here under considera

tion.

At this writing the Legislature has entered into an unprecedented

third special session, from which another “segregation package” is

presumably to be expected.

5a

stitutional right, and that all officers of the state, more

especially those who have taken an oath to uphold the

Constitution of the United States, including the governor,

the members of the state legislature, judges of the state

courts, and members of the local school boards, are under

constitutional mandate to take affirmative action to accord

the benefit of this right to all those within their jurisdiction.

U. S. Const., Art. VI, cl. 2, 3; Cooper v. Aaron, 358, U. S. 1.

3. That when, notwithstanding their oath so to do, the

officers of the state fail to obey the Constitution’s com

mand, it is the duty of the courts of the United States to

secure the enjoyment of this right to all who were deprived

of it by action of the state. Brown v. Board of Education,

349, U.S. 294, 299-301.

4. That the enjoyment of this constitutional right can

not be denied or abridged by the state, and that every law

or resolution of the legislature, every act of the executive,

and every decree of the state courts, which, no matter how

innocent on its face, seeks to subvert the enjoyment of this

right, whether directly through interposition schemes, or

indirectly through measures designed to circumvent the

orders of the courts of the United States issued in protec

tion of the right, are unconstitutional and null. Cooper v.

Aaron, supra; United States v.. Louisiana,------ U.S. ------

(Dec. 12, 1960), denying stay in United States v. Louisiana,

------ F.Supp.------- (Nov. 30,1960).

All this has been clear since 1954 when the Supreme

Court announced its decision in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483. Yet, Louisiana’s record since that time

has been one of stubborn resistance.2 With singular per

sistence, at every session since 1954, its Legislature has

continued to enact, and re-enact, measures directly in

2 See Note 1.

6a

tended to deny colored citizens the enjoyment of their

constitutional right, the most recent and the most flagrant

being the interposition declaration of the First Extraor

dinary Session of 1960 which purports to nullify the right

itself. In each instance, this court has patiently examined

the legislation and explained the reason why it could not

stand. The segregation packages enacted at the Regular

Sessions of 1954, 1956, 1958 and 1960, and at the First

Extraordinary Session of 1960, have all been considered

in detail.3 The basis of these rulings is obvious enough.

But, when this court, with what no one dare term undue

haste, finally set a date for the practical enjoyment of the

constitutional right already so long delayed, and invited

the School Board of Orleans Parish, where implementa

tion was to begin, to submit a plan of desegregation, a

new line of attack was initiated. Orleans Parish and its

School Board now became the prime target.

The Louisiana Legislature initially enacted measures to

deprive the Board of the power to comply with the orders

of the court. In consequence, the Orleans School Board

offered no suggestions and this court was compelled to

devise its own plan of desegregation, admittedly a modest

one involving initially only the first grade. On the plea

of the Board, the effective date for the partial desegrega

tion of the public schools of New Orleans was delayed two

months to November 14, 1960. At length, the Orleans

Parish School Board realized its clear duty and announced

its proposal to admit five Negro girls of first-grade age to

two formerly all-white schools. But for obeying the con

stitutional mandate and the orders of this court, the Board

brought on itself the official wrath of Louisiana. Despite

reiterated injunctions expressly prohibiting them from

“ interfering in any way with the administration of the

public schools for Orleans Parish by the Orleans Parish

3 See Note 1.

7a

School Board,” 4 the members of the Legislature, already

called into special, now apparently continuous, session,5

took every conceivable step to subvert the announced in

tention of the local School Board and defy the orders of

this court. Acts and resolutions were passed to abolish

the Orleans Parish School Board and transfer the admin

istration of the New Orleans schools to the Legislature,

and when the enforcement of these measures was restrained,

four members of the local Board were attempted to be

addressed out of office. As we noted in declaring these acts

and resolutions unconstitutional,6 they were of course part

of the general scheme to deny the constitutional rights

of the plaintiffs here. But, more than that, there was in this

legislation a deliberate defiance of the orders of this court

issued in protection of those rights. If for no other rea

son, the measures were void as illegal attempts to thwart

the valid orders of a federal court.

Against this background, it is nevertheless asserted that

the present acts and resolutions, Act 27 and House Con-.

4 See, e.g., Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 187 F. Supp.

42; id .,------ F. Supp.------- (Nov. 30, 1960).

5 At this writing, the legislators are in their third successive

special session.

6 Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board,------ F. Supp.------- (Nov.

30, 1960).

7 At the outset the defendants represented by the Attorney Gen

eral of Louisiana, citing Title 28, U. S. Code, Section 2284, moved

for a stay of these proceedings insofar as they relate to Act 2 of

the Second Extraordinary Session of 1960 on the ground that a

state court, in litigation challenging the constitutionality thereof,

has issued a temporary restraining order against its enforcement.

The action in the state court is a taxpayers’ suit seeking, not the

enforcement of, but an injunction against the enforcement of Act

2. Since 28 U. S. C. §2284 requires a stay in this court only where

the state court action in which the stay has been granted is a suit

to enforce the statute rather than to enjoin its enforcement, that

section appears inapplicable here.

If this be deemed a too technical reading of §2284, still that

section has no application here because the stay in state court

8a

current Resolutions 2, 23 and 28, are invulnerably insulated

from federal judicial review. Yet they are no different in

kind, or in purpose, from those just discussed. Again the

plain object of the measures is to frustrate the Orleans

Parish School Board in its effort to comply with this court’s

orders,8 and, again, the effect of the measures is to defy

this court’s injunction prohibiting interference with the

administration of the local schools by its own elected school

board.9 Thus, Act 2 of the Second Extraordinary Session

of 1960 expressly purports to vest primary control of the

New Orleans schools in the Legislature itself under the

very acts and resolutions already declared unconstitutional

enjoins the enforcement of only one section of the state statute in

question, the section which relates to the appointment of a school

board with only fiscal functions. It does not in any way enjoin the

meat of the statute, the section providing for the control and

operation of the Orleans Parish schools by the Louisiana Legis

lature rather than the Orleans Parish School Board. It is this

latter section which is of primary importance here. Since the state

court stay is not broad enough to protect the parties here in suit,

§2284 has no application. Dawson v. Kentucky Distilleries Co., 255

U.S. 288, 297. Moreover, and perhaps this should have been men

tioned first in order of importance, the state court stay, initially

granted at the district court level, has now been “hereby dissolved,

recalled and set aside” by the Supreme Court of Louisiana. George

L. Singelmann, et al. v. Jimmie H. Davis, et al., La. Sup. Ct., No.

45,477 (Dec. 15, 1960).

8 The Orleans Parish Board is more than an original defendant

in these proceedings. As noted, it is itself under a constitutional

duty, and court order, to implement the right in question, and,

may assert the right of its wards, the school children of Orleans

Parish. Moreover, it has a right to be free from interference in

complying with the orders of this court. Unquestionably, this right

is a federal right. It will be protected by this court to the full

extent of the law. See Brewer v. Hoxie School District No. 46,

8 Cir., 238 F. 2d 91.

9 The United States obviously has a vital interest in vindicating

the authority of the federal courts. It is therefore appropriate that

the Government, as amicus curiae, institute proceedings herein to

protect the court against illegal interference. Faubus v. United

States, 8 Cir., 254 F. 2d 797, 804-805.

9a

by this court, and, for fiscal matters, to create a new board.

House Concurrent Resolutions 2, 23 and 28 of the same

session attempt to deny the School Board control of its

own funds deposited in local banks and warn the banks

against honoring the Board’s checks. However local in

character Act 2 and Resolutions 2, 23 and 28 may appear,

since they would discriminate against Negro children

through interference with the orders of this court, they

are invalid. Gomillion v. Lightfoot, ------ U.S. ------ (Nov.

14, 1960); Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1: Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U.S. 483.

Before the court also is the application of the Orleans

Parish School Board for a temporary injunction requiring

certain banks in the City of New Orleans to honor its

checks drawn on its accounts in those banks. Because of

the resolutions warning the banks not to recognize the

Orleans Parish School Board as such, the banks, pending

court direction, have blocked the accounts and refused to

honor checks drawn on them by anyone. In addition, the

Board asks that the City of New Orleans, as the tax col

lector for the Board, be directed, by temporary injunction,

to remit to the Board the taxes so collected as required by

law.

In view of our holding herein that Act 2 and House Con

current Resolutions 2, 23 and 28 of the Second Extraor

dinary Session of the Louisiana Legislature of 1960 are

invalid, the Orleans Parish School Board, as the duly

constituted and elected authority to operate the public

schools of New Orleans, is the owner of the bank accounts

in question and the proper party to draw checks thereon.

By the same holding the City is required to remit to the

Board its tax monies.

Finally, the United States, amicus curiae, has moved for

a temporary restraining order against Act 5 of the Second

Extraordinary Session of 1960. This Act would make the

10a

Attorney General of Louisiana counsel for the Orleans

Parish School Board, replacing counsel named by the

Board. The Attorney General argues that certainly the

Legislature has the right to name counsel for a state hoard

which it created, certainly this is a local matter unaffected

hy any federal constitutional considerations.

Unquestionably, the appointment of counsel for the

Board is a local matter. I f the appointment is not part

of the legislative scheme of discrimination, it is insulated

from federal judicial review. Cooper v. Aaron, supra.

Let us see then what the purpose of Act 5 is, what its effect

would be. Gomillion v. Lightfoot, supra.

The Orleans Parish School Board is under the injunction

of this court to desegregate the public schools in the City

of New Orleans. After several years resistance, it is now

making a good faith effort to comply. In this effort it is

being harassed by the Louisiana Legislature which has

been sitting in successive extraordinary sessions solely

for this purpose. During these sessions, the Legislature,

in it determination to preserve racial segregation in the

Orleans Parish schools, has on four occasions sought to

wrest control of the schools from the Board and on one

occasion sought to address its majority out of office. The

Legislature has also brought financial chaos to the Board

through a series of statutes and resolutions denying the

Board control of its fisc, one resolution even warning the

banks not to honor the Board’s checks drawn on its own

accounts.

Against this harassment the Board, through its counsel,

has sought the protection and the aid of this court in carry

ing out its orders. In these present proceedings, for ex

ample, the Board, through its counsel, has sought the aid

of the court in unfreezing its bank accounts so that the

salary checks of its employees will be honored. The At

torney General, pursuant to Act 5, has sought to replace

11a

counsel for the Board, and without consulting his new

client, moved to withdraw the Board’s motion against the

banks. Thus the purpose of Act 5 becomes clear, if indeed

there was ever doubt. Its purpose is to require the Board,

in its effort to comply with the orders of this court, to use

the opposition’s lawyer to protect itself from the opposi

tion. Thus Act 5 is exposed as one of the Legislature’s less

sophisticated attempts to preserve racial discrimination in

the public schools of New Orleans.

The temporary injunction will issue as prayed for, as

will the temporary restraining order. Decree to be drawn

by the court.

/ s / R ichard T. R ives

Richard T. Rives, Judge

United States Court of Appeals

/ s / H erbert W. Christenberby

Herbert W. Christenberry, Chief Judge

United States District Court

/ s / J. S helly W right

J. Skelly Wright, Judge

United States District Court

New Orleans, Louisiana

December 21st, 1960

SUITE 1790

10 COLUMBUS

NEW YORK 19,