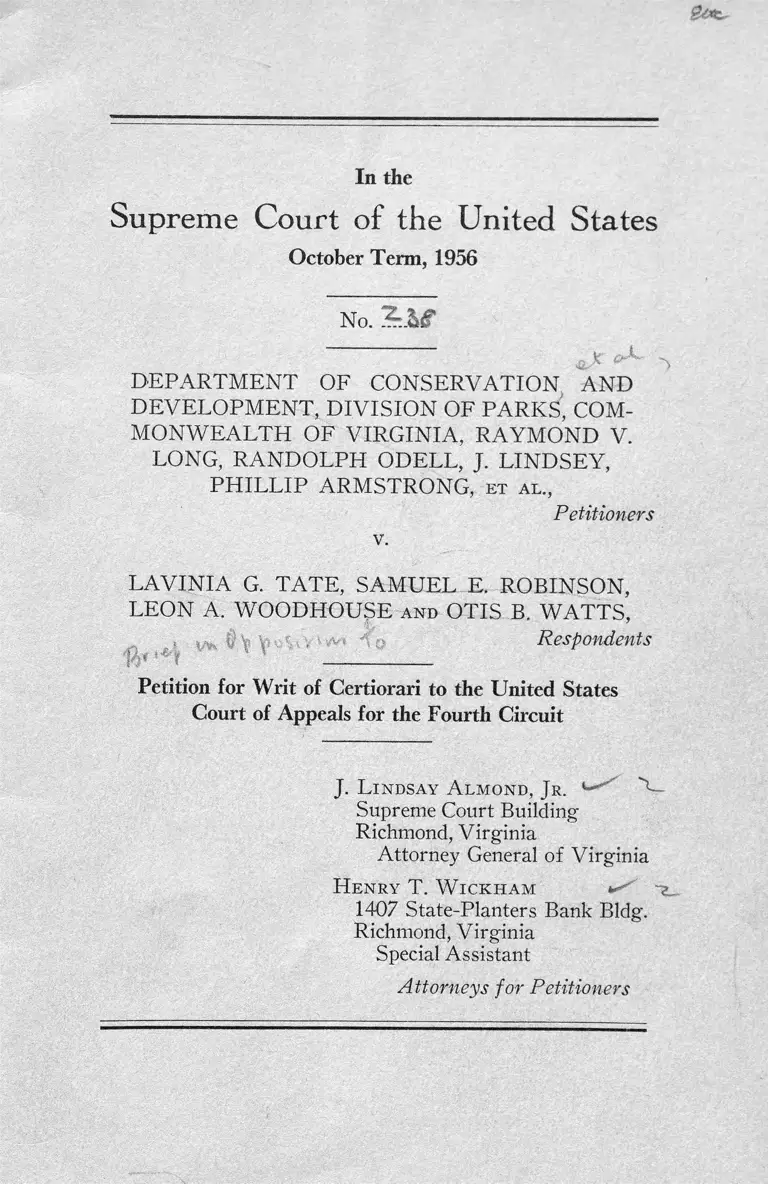

Department of Conservation and Development v. Tate Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

July 5, 1956

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Department of Conservation and Development v. Tate Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1956. 33e8ad29-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8988237a-c156-40ec-bbea-821f91f53a10/department-of-conservation-and-development-v-tate-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1956

No.

D EPARTM EN T OF CON SERVATION AN D

DEVELOPM EN T, D IVISIO N OF PARKS, COM

M O N W E A LTH OF VIRG IN IA, RA YM O N D V.

LONG, RAN DO LPH ODELL, J. LIN DSEY,

PH ILLIP ARM STRONG, et al.,

Petitioners

v.

L A V IN IA G. TATE, SAM U EL E. ROBINSON,

LEON A. W O OD H O U SE and OTIS B. W A TTS,

Respondents

| /VI' ? * * | _______________________

Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

J. L indsay A lmond, Jr.

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia

Attorney General o f Virginia

H enry T. W ickham

1407 State-Planters Bank Bldg.

Richmond, Virginia

Special Assistant

Attorneys for Petitioners

TABLE OF C O N TE N TS

O p in io n s of C ourts B e l o w ................. - ......................... ............................ 2

S t a t e m e n t of J u risdiction ....................................................................... 2

Q u estion s P r e s e n t e d ......................................... 2

T h e C o n s t it u t io n a l P rovisions a n d S tatu tes I n v o l v e d ....... 3

S t a t e m e n t of t h e C a s e ................................................................................ 4

A r g u m e n t .................................................................................. 8

I. The Action of the District Court Was Premature for It Has

No Authority to Dictate the Provisions, or the Operations

of, a Lease That May Be Executed by the State at Some

Future T im e................................................................................ 8

II. State Action Under the Fourteenth Amendment................... 12

A ppe n d ix :

I. Opinion of Court of Appeals for Fourth Circuit....... App. 1

II. Final Decree of District C ourt................................... . App, 3

TABLE OF C IT A T IO N S

Cases

Barney v. City of New York, 193 U. S. 430 (1904) ........................ 13

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 (1953) ...................................... 13

Page

Blease v. Safety Transit Co., 50 F. (2d) 852, 856 (4th Cir. 1931) .. 9

Brunswick v. Elliott, 103 F. (2d) 746 (D. C. App. 1939) ............ 9

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 11 (1883) .................................. 12

Connecticut v. Massachusetts, 282 U. S. 660, 674 (1931) .............. 9

Culver v. City of Warren, 83 N. E. (2d) 82 (Ohio, 1948) ............ 14

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corporation, 229 N. Y. 512, 87 N. E.

(2d) 541 (1949), cert, denied, 339 U. S. 981 (1950) .............. 13

Irwin v. Dixon, 50 U. S. 10 (1850) ................................................. 9

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library of Baltimore City, 149 F. (2d)

212 (4th Cir. 1945) ........................................................................ 14

King v. Buskirk, 78 F. 233, 235 (4th Cir. 1897) ..... ........................ 9

Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (D.C.S.D. W . Va.

1948) ................................................................................................. 14

Michael v. Cockerall, 161 F. (2d) 163, 165 (4th Cir. 1947) .......... 9

Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938) ........... 12

Norris v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 78 F. Supp. 451

(D. Md. 1948) ................................................................................ 13

Raymond v. Chicago Traction Co., 207 U. S. 20 (1907) ............... 13

Rice v. Sioux City Memorial Cemetery, 349 U. S. 70 (1955) ....... 13

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) ............................................. 12

Snowden v. Hughes, 321 U. S. 1 (1943) .......................................... 13

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461 (1953) ............................................. 13

Page

Page

Truly v. Wanzer, 46 U. S. 141, 142-143 (1847) .............................. 9

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75, 89-90 (1947) .... 9

U. S. v. Appalachian Elec. Power Co., 107 F. (2d) 769, 790 (4th

Cir. 1939) ........................................................................................ 9

U. S. v. Williams, 341 U. S. 70, 77 (1951) ....................................... 12

Other Authorities

Code of Virginia (1950) :

Section 10-21.1 ............................................................................ 2, 11

Constitution of United States:

Fourteenth Amendment .................................................................... 3

51 C. J. S., Landlord and Tenant:

Section 2, p. 510................................................................................ 10

11 M. J. Virginia and West Virginia, Landlord and Tenant:

Section 29, p. 684 ............................................................................ 10

United States Code:

Title 28, Section 1254 ..................................................................... 2

Title 28, Section 1343 ........................................................................ 8

Title 28, Section 2201 ........................................................................ 8

Title 28, Section 2202 ........................................................................ 8

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1956

No.

D EPARTM EN T OF CO N SERVATION AN D

DEVELOPM EN T, D IVISIO N OF PARKS, COM

M O N W EALTH OF VIRG IN IA, RAYM O N D V.

LONG, RAN D O LPH ODELL, J. LINDSEY,

PH ILLIP ARM STRONG, et a l .,

Petitioners

L A V IN IA G. TATE, SAM U EL E. ROBINSON,

LEON A. W O OD H O U SE an d OTIS B. W A TTS,

Respondents

Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

To the Honorable the Chief Justice and the Associate

Justices of the Supreme Court o f the United States:

Your petitioners, Department of Conservation and De

velopment of the Commonwealth of Virginia, et al., respect

fully pray that a writ of certiorari be issued out of and under

the seal of the Court to review the decision of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit hereinafter

set forth and represent as follows:

2

O P IN IO N S OF C O U R T S BELO W

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is found as Depart

ment of Conservation and Development v. Tate, 231 F. (2d)

615, and is printed as Appendix I to this petition.

The opinion of the District Court for the Eastern District

of Virginia, at Norfolk, is found as Tate v. Department of

Conservation and Development, 133 F. Supp. 53, and is

printed as Appendix II of “ Brief and Appendix on Behalf

of Appellants,” which is made a part of the record in this

case in accordance with Paragraph 4 of Rule 21 of this

Court. In accordance with Rule 23, paragraph l ( i ) of this

Court, it is not reprinted here.

ST A T E M E N T OF JU R ISD IC TIO N

The final decree of the District Court for the Eastern

District of Virginia, at Norfolk, was entered on October 6,

1955, and the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

affirmed said decree on April 9, 1956.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title 28,

United States Code, Section 1254 (June 25, 1948, c. 646,

62 Stat. 928).

Q U EST IO N S PRESENTED

I .

Were the respondents entitled to injunctive relief with

respect to future actions of the State and an unknown lessee

when there had been no equitable or legal rights of the

respondents threatened thereby ?

II.

Does the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

3

the United States require a State, when leasing its property,

to provide in the lease, or otherwise, that the lessee must not

discriminate against the members of any race?

III.

Do independent actions of a lessee fall within the “ State

action” prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment?

TH E C O N S T IT U T IO N A L PR O VISIO N S AN D

STA TU TES IN V O L V E D

The pertinent part of the Fourteenth Amendment reads

as follows:

“ Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the

United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,

are citizens of the United States and of the state where

in they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law

which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of

citizens of the United States; nor shall any State de

prive any person of life, liberty, or property, without

due process of law; nor deny to any person within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Section 10-21.1 of the Code of Virginia, as amended

(1954 Cumulative Supp., Vol. 3, p. 14), reads as follows:

“ The Director is hereby authorized and empowered,

subject to the consent and approval of the Governor, to

convey, lease or demise to any responsible individual,

organization, association or corporation for such con

sideration and on such terms as the Board may pre

scribe, by proper deed or other appropriate instrument

signed and executed by the Director, in the name of the

Commonwealth, any lands or other properties held for

general recreational or other public purposes by the

Commonwealth, for the Department, or over which it

4

has supervision and control, or any part or parts there

of, or right or interest therein or privilege with respect

thereto. The Governor is also hereby authorized and

empowered to direct the discontinuance of the opera--

tion of any or all State parks when in his judgment the

public interest so requires.

“ (3 ) Any such conveyance, lease or grant herein

authorized shall be subject to such further provisions,

conditions, restrictions and reservations as may be ap

proved by the Governor and prescribed by the Direc

tor.”

ST A T E M E N T OF TH E CASE

The case below came on to be heard on April 26, 1955,

and again on June 29, 1955, upon the complaint and amend

ed and supplemental complaint of the respondents for de

claratory judgment and a preliminary and permanent in

junction and answer of the petitioners. The respondents

prayed that the petitioners, their lessees, agents and successors

in office be restrained from denying them and others simi

larly situated, the use and enjoyment of the Seashore State

Park on account of race and color.

It was stipulated and conceded by counsel for the peti

tioners that the Seashore State Park, located in Princess

Anne County, Virginia, is a state park maintained and

operated as part of the recreational facilities under the

supervision and control o f the Department of Conservation

and Development of the Commonwealth of Virginia, that

the said Park is supported by public funds and is the only

state park operated by the petitioners in Princess Anne

County, Virginia.

It was further conceded by counsel that the respondents

sought the use of the recreational facilities of the aforesaid

Seashore State Park and that they were denied admission

thereto solely because they were members of the Negro race.

5

Furthermore, the petitioners, in denying the respondents

admission to Seashore State Park, admittedly violated the

rights of the appellees guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the United States Constitution, as that amendment

has recently been construed by this Court and the Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.

On July 7, 1955, the District Court rendered its opinion,

and on October 6, 1955, a final decree was entered enjoining

not only the petitioners, but also unknown lessees of the

petitioners. The District Court further ordered that if the

Seashore State Park were leased, “ the lease must not, di

rectly or indirectly, operate so as to discriminate against the

members of any race.”

An appeal was taken from the above-mentioned decree

and argument thereon was heard on March 21, 1956. On

April 9, 1956, the Court of Appeals affirmed the decree of

the District Court in a per curiam opinion.

The original bill of complaint for injunctive relief was

filed in the District Court on June 21, 1951, and the peti

tioners filed their answer on July 16, 1951. The case was

subsequently set for trial but upon the request of the re

spondents, it was continued generally. The case remained

dormant on the docket until counsel for all parties received

a notice of conference for trial assignment from the Clerk

of the District Court stating that the case had been set for a

pre-trial conference, report and fixing of date of trial in the

Judge’s Chambers at Norfolk, Virginia, on November 5,

1954.

At the hearing in the District Court on April 26, 1955,

the petitioners filed the affidavit of Raymond V. Long, Di

rector of the Department of Conservation and Development

of the Commonwealth of Virginia, wherein it was stated

that the Director had been empowered to enter into negoti

ations for the lease of the Seashore State Park. It was fur

6

ther stated that the lease would not contain a provision which

could be construed as restricting the use of the Park to

members of the white race. The Director also stated in his

affidavit that he had never made a statement to the press con

ceding that the segregation issue was a prominent factor

in the decision to lease the Seashore State Park. This last

statement was deemed material to the proceedings at that

time, since at the hearing on the motion for preliminary

injunction held on March 12, 1955, both counsel for the re

spondents and the District Court had referred to alleged

newspaper reports concerning the reasons for leasing Sea

shore State Park.

After the affidavit was filed with the District Court on

April 26, 1955, counsel for petitioners filed their motion

to dismiss the preliminary injunction which had been granted

on March 12, 1955, on the ground that there were no allega

tions in any affidavit or in the verified complaint showing

specific facts that would result in immediate and irreparable

injury to the respondents. The District Court did not rule

upon this motion.

Thereafter, counsel for the petitioners stipulated the facts

hereinabove set forth and stated that they would consent to

a decree enjoining the petitioners either directly or through

their agents, servants or employees, and each o f them, their

successors in office and their agents and employees, from

refusing, on account of race or color to admit the respond

ents, and other Negroes similarly situated, to the Seashore

State Park.

The respondents would not agree to such a decree but

insisted that the decree o f the District Court should also

enjoin a lessee who was not a party to this action and was

not, in fact, in existence. The District Court then directed

counsel to submit briefs on the power of the Court to enjoin

an unknown lessee, and stated that all parties would be given

7

the opportunity to present additional evidence if they so

desired.

After briefs were submitted to the District Court, counsel

for the respondents requested permission to interrogate the

Director of the Department of Conservation and Develop

ment and also requested oral arguments in support of their

brief. This hearing was set for June 29, 1955, at which

time, the testimony of Raymond V. Long was taken.

The facts of the case are not in dispute. Seashore State

Park, located in Princess Anne County, near Cape Henry,

is the only one of nine State parks located in that area.

All of these parks have been maintained and operated

under the supervision and control o f the Department of

Conservation and Development, an agency of the Common

wealth of Virginia. The parks were built and maintained

by public funds, but in 1950 revenue bonds in the amount

of $600,000 were issued to cover the erection of sixty-seven

cabins throughout the State Park system at the cost of about

$8,000.00 each. Nine of these cabins are at Seashore State

Park, and it is estimated that a yearly revenue of approxi

mately $8,000 is required to pay Seashore’s proportionate

share of the Revenue Bond expenditures. An outstanding

indebtedness of about $415,000 remains. In case of default,

there is no legal duty on the part o f the State to pay the

bondholders. They are payable only out of revenue derived

from the rental of cabins. The trust indenture, however,

gives the bondholders wide authority, and under certain cir

cumstances, the trustee may take over and operate the cabins

on behalf of the bondholders.

The present litigation arose when the respondents were re

fused admittance to Seashore State Park, solely by reason of

the fact that they were members of the Negro race. Between

this incident on June 16, 1951, and the time the case finally

came before the District Court, the State of Virginia, real

8

izing it could not operate the parks in a segregated manner,

and feeling that it could not run the parks profitably on an

unsegregated basis, had investigated the possibilities of leas

ing the park to a private lessee who would be bonded to

guarantee sufficient income to meet the bond requirements.

The lessee would be free to operate the park in any manner

he saw fit.

The State possesses the power to lease its property under

Section 10-21.1 of the Code of Virginia, as amended, and

made a press release on February 25, 1955, indicating that

the Park might be leased. In response to this information,

eighteen applicants indicated interest in this matter. No

lease had been drawn up or signed, however, nor did the

State know who the prospective lessees were. It was in

tended that the lease would be a negotiated one, thus guar

anteeing to the State the high quality of management and

necessary experience that are a requisite in the running of

recreational facilities. The provisions of the lease, however,

had been discussed only in the most general terms.

The jurisdiction of the District Court for the Eastern

District of Virginia, Norfolk Division, was invoked pur

suant to Title 28, United States Code, Section 1343, and

Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2201 and 2202.

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Action of the District Court Was Premature for It Has

No Authority to Dictate the Provisions, or the Operation

of, a Lease That May Be Executed by the State at Some

Future Time.

Section 2, of Article III, of the Constitution of the United

States has been uniformly construed as prohibiting the

9

rendering of advisory opinions. Furthermore, the existence

of an actual controversy is necessary for an adjudication of

a constitutional issue. See, United Public Workers v.

Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75, 89-90 (1947), and Michael v. Cock-

erall, 161 F. (2d) 163,165 (4th Cir. 1947).

It is hard to conceive that the possibility of a discrimina

tory practice on the part of an unknown lessee, bound by

a non-existent lease, could give the respondents a concrete

legal issue upon which the District Court could render a

decree. The record is devoid of probative facts which could

tend to sustain the District Court’s decree to that extent.

There are three elementary doctrines concerning the issu

ance of injunctions that the District Court has discarded in

this proceeding.

First, “ there is no power, the exercise of which is more

delicate, which requires greater caution, deliberation, and

sound discretion, or more dangerous in a doubtful case, than

the issuance of an injunction.” Truly v. Wanzer, 46 U. S.

141, 142-43 (1847) and King v. Buskirk, 78 F. 233, 235

(4th Cir. 1897).

Second, “ the plaintiff must show that the injury sought to

be avoided by the injunction will be necessarily or practically

certain, and not merely the probable, result of the acts

whether intended or not.” United States v. Appalachian

Electric Power Co., 107 F. (2d) 769, 790 (4th Cir. 1939).

See, also, Connecticut v. Massachusetts, 282 U. S. 660, 674

(1931) and Blease v. Safety Transit Co., 50 F. (2d) 852,

856 (4th Cir., 1931).

Third, courts will not apply their equitable powers merely

to allay litigants’ fears. Irwin v. Dixon, 50 U. S. 10 (1850)

and Brunswick v. Elliott, 103 F. (2d) 746 (D. C. App.

1939).

The Commonwealth of Virginia, as already pointed out,

10

readily admits that the respondents had been denied admit

tance to Seashore State Park solely by reason of the fact

that they were members of the Negro race. The petitioners

also admit that such an act constitutes state action which is

properly enjoinable by the District Court. However, the

record in the proceedings below show that there is no lease,

thus there can be no lessee. The respondents have not been

denied admission to the park by any lessee for any reason

whatsoever, nor does the record show that there is any

reasonable certainty that such an action will take place.

Under such circumstances, it is inconceivable that the re

spondents have been so injured or so threatened with injury

as to warrant the enjoining of an unknown lessee, or to

warrant the mandate directing that if the park is leased,

“ the lease must not, directly or indirectly, operate so as to

discriminate against the members of any race.”

This unwarranted injunctive relief is based on mere con

jecture, speculation and hypothetical threats. It is certainly

not based on the evidence in the record or on any legal

authority or sound reasoning. At best, it is premature.

Generally speaking, the relation of landlord and tenant,

or lessor and lessee, is one which exists between two inde

pendent parties and does not involve an agency relation, a

master-servant relation, an employer-employee relation, or

a licensor-licensee relation. The lessor transfers both pos

session and right of possession. 11 M. J., Virginia and West

Virginia, Landlord and Tenant. Section 29, p. 684. See

also, 51 C. J. S., Landlord and Tenant, Section 2, p. 510.

There was no evidence before the District Court that there

would be anything other than a normal landlord-tenant re

lation if the petitioners should lease the Seashore State Park.

Absent such evidence, it is clear that the Court did not have

the power to include an unknown lessee in its injunction

order.

11

If, of course, at a later date the petitioners do lease the

Seashore State Park and it is found, as a fact, that Negroes

are excluded and that the normal lessor-lessee relation does

not exist, and there is privity between the petitioners and the

then known lessee, contempt proceedings could be brought

against the petitioners, as well as the so-called lessee, even

though the latter was not a party defendant below. This is

true, since the petitioners conceded that they should be en

joined from denying admission to Negroes on racial grounds.

The District Court stated that it was not necessary to

decide whether it was proper to enjoin an unknown lessee in

this case, since the lessors were before the court. The lan

guage of the final decree, to-wit: “ * * * the lease must not,

directly or indirectly, operate so as to discriminate against

the members of any race, * * *” does by indirection what

the court could not accomplish directly. It not only restricts

the State, but it restricts an unknown lessee.

Section 10-21.1 of the Code of Virginia provides that a

lease shall be subject only to the conditions, restrictions and

reservations prescribed by the Director of the Department

of Conservation and Development and approved by the Gov

ernor. No State would intentionally write a provision in any

lease that would violate the Federal Constitution or any

Federal or State law. If the rights of any citizen of this

State are denied because of any lease or any action on the

part of the State, such citizen can always go into Court and

ask for protection. Until, however, such rights are denied

or have been threatened, no action will lie. This is the situ

ation there.

The District Court has placed the cart before the horse,

and has attempted to decide a purely abstract question, which

is premature at this time because of lack of evidence.

12

II.

State Action Under the Fourteenth Amendment

The record is devoid of any evidence that the State has

acted in bad faith; that the respondents will be injured; or

that a prospective lessee will be an agent of the State, rather

than an independent principal. Yet the Courts below, in their

opinions, have relied upon “ state action” cases that were

based upon facts that either indicated bad faith on the part

o f the “ state” or clearly showed privity between the lessor

and lessee, or both.

Subject to constitutional restraints, a State may dispose

of its property as any private citizen. The State’s power to

lease Seashore State Park cannot be denied. See Section 10-

21.1 of the Code of Virginia, as amended.

Individual invasion of individual rights is not protected

by the Fourteenth Amendment. Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.

S. 3, 11 (1883). Thus, the only protection against discrim

ination that the District Court could afford the respondents

is protection against discrimination by the Commonwealth

of Virginia. United States v. Williams, 341 U. S. 70, 77

(1951).

The question to be decided, then, is whether or not the

actions of an independent lessee, in operating Seashore State

Park in any manner he saw fit, constitute “ state action.”

The precise question of what constitutes “ state action”

under the Fourteenth Amendment has come before the

courts many times, and reasonably clear and definable lines

of demarcation have appeared. Thus, if a state court en

forces a private restrictive covenant, it will be “ state action,”

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948); and where a State

and university are closely tied, the amendment will apply.

Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938).

13

See, also, Rice v. Sioux City Memorial Cemetery, 349 U. S.

70 (1955); Snowden v. Hughes, 321 U. S. 1 (1943) ; Ray

mond v. Chicago Traction Co., 207 U. S. 20 (1907); Bar-

rows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 (1953); Terry v. Adams,

345 U. S. 461 (1953). But private, individual, or corporate

affirmative action without State support will not be consid

ered “ state action.” Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corpora

tion, 229 N. Y. 512, 87 N. E. (2d) 541 (1949), cert, denied,

339 U. S. 981 (1950) ; Norris v. Mayor and City Council

of Baltimore, 78 F. Supp. 451 (D. Md. 1948); see, also,

Barney v. City of New York, 193 U. S. 430 (1904).

While the petitioners readily admit that they were prop

erly enjoined from denying the respondents, by reason of

race, the right to use and enjoy the facilities of the Seashore

State Park, it is earnestly contended that the actions of an

independent future lessee are not limited by the provisions

of the Fourteenth Amendment. Accordingly, the District

Court has no authority to limit the actions of a future lessee,

either directly or indirectly, under the facts of this case.

Modern social concepts have caused an ever-increasing

area wherein Federal courts have declared “ state action” to

exist, but, while conclusions have been varied, the test of

“ state action” has remained constant. A factual analysis is

the key to proper determination of this question.

Once there is a material identification or a substantial

degree of control by the State over so-called independent

actions of a private individual or association, those actions

become state actions within the meaning of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

For example, in Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, there was a

substantial degree of state control, since there was judicial

enforcement by state courts of restrictive covenants against

certain races. Flowever, in Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town

Corporation, supra, it was held that there was no substantial

14

degree of control by the “ state” and thus no “ state action,”

even though a life insurance company had obtained land

from the City of New York upon which to build a housing

development and had obtained a tax exemption on the

property.

In Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library of Baltimore City,

149 F. (2d) 212 (4th Cir. 1945), the court below found

“ state action” in that the State, through the City of Balti

more, continued to supply a private library corporation with

means of existence. Thus, there was a substantial degree of

control by the State.

But, in Norris v. Mayor and City Council o f Baltimore,

supra, the District Court found no substantial degree of

control by the state, since the mechanical institute was a

private corporation and was not subject to control of public

authority, notwithstanding receipt o f public funds in consid

eration of free scholarships and favored treatment as lessee

of public property.

The case of Terry v. Adams, supra, is an example of

“ state action” because of material identification. There, it

was held that a Texas political organization which dupli

cated the State’s election process could not exclude Negroes

from voting in its “ primary.” The organization was mate

rially identified with the State through the Democratic

Party.

The conclusions reached in the cases relied upon by the

District Court in its opinion are justified under the material

identification test; but the facts therein are readily distin

guishable from the facts in the instant case. In the swim

ming pool cases, Culver v. City of Warren, 83 N. E. (2d)

82 (Ohio 1948) and Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp.

1004 (D.C.S.D. W. Va. 1948), it was found that the private

associations were mere municipal instrumentalities through

15

which the cities operated the pools. Both of the associations

were non-profit, both were formed shortly before the leases

were executed, and both paid nominal rent.

In the Lawrence case, all of the net revenues derived by

the lessee were required to be used to improve and develop

the property and the evidence clearly showed that the mu

nicipality was acting in bad faith, the purpose of the lease

being to discriminate against Negroes.

In the Culver case, the city had the duty to make repairs.

Further, it was found that the lessee confined approved

applications to members of the white race, and Negro vet

erans were rejected. The court, in effect, held that there

was merely a “ colorable” lease.

In the instant case, the Department of Conservation and

Development has advertised for bids from individuals or

profit-making associations or corporations for the purpose

of procuring a lessee who will be able to operate the park at

sufficient profit to guarantee the financial return of a mini

mum of $8,000.00 per annum, which amount the State is

required to pay the holders of the revenue bonds issued to

finance the construction of eight cabins at Seashore State

Park.

Since there is evidence that there will be normal lessor-

lessee relationships and that the Department of Conserva

tion and Development, in fact, does not know who has made

application to lease the park, there can be no charge of bad

faith. Furthermore, under such circumstances, there is no

material identification or substantial degree of control by the

State to warrant a finding of “ state action.”

This Court’s previous decisions and the decisions of lower

Federal courts do not justify the decisions of the courts be

low. The so-called “ state action” doctrine has been extended

for the first time to unknown lessees of the State, acting as

16

independent parties. The State should be free to dispose of

its property under applicable State law without interference

from the Federal courts. The decision in the instant case

does not permit this. To the contrary, the decision below

indicates that the State is now compelled to place an affirma

tive provision in every lease to which it is a party stating, in

terms, that the lessee will not discriminate against the mem

bers o f any race, whether the lease be for a term of months

or for a period of ninety-nine years.

Accordingly, it is respectfully submitted that the court

below has decided an important question under the Four

teenth Amendment in a way that has extended, and, in fact,

departed from, applicable decisions of this Court, and thus

calls for the exercise of the supervisory power of this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

J. L indsay A lmond, Jr.

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia

Attorney General of Virginia

FIenry T. W ickham

1407 State-Planters Bank Bldg.

Richmond, Virginia

Special Assistant

Attorneys for Petitioners

Dated: July 5, 1956.

17

C E RTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the aforegoing petition

have been served by mailing the same, with first class post

age prepaid, to the following counsel of record:

Victor J. Ashe, Esquire

1134 Church Street

Norfolk 10, Virginia

J. Hugo Madison, Esquire

1017 Church Street

Norfolk 10, Virginia

James A. Overton, Esquire

801 High Street

Portsmouth, Virginia

Oliver W. Hill, Esquire

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

Spottswood W. Robinson, III, Esquire

623 North Third Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

on this..... day of July, 1956.

H enry T. W ickham

A P P E N D I X

APPENDIX I

O P IN IO N OF C O U R T OF APPEALS

FO R F O U R T H C IR C U IT

Per Curiam :

This is an appeal in an action instituted by Negro citizens

of Virginia against the Department of Conservation and

Development, Division of Parks, of the Commonwealth of

Virginia and the individual park commissioners to enjoin

threatened racial discrimination in the operation of Sea

shore State Park. Decree was entered therein enjoining

the defendants, their “agents, lessees and successors in

office” from denying to “ any person of the Negro race, by

reason of his race and color, the right to use and enjoy the

facilities” of the park. The decree further provided “ that if

said Park or any part thereof is leased, the lease must not,

directly or indirectly operate so as to discriminate against

the members of any race.” The defendants have appealed

complaining especially of the provision last quoted.

W e think that the decree appealed from is correct for

reasons adequately stated in the opinion of the District

Judge and that little need be added thereto. See 133 F. Supp.

53. It is perfectly clear under recent decisions that citizens

have the right to the use o f the public parks of the state

without discrimination on the ground of race. Dazvson et

al v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore 4 Cir. 220 F.

2d 386, aff. 350 U. S. 877; Holmes v. Atlanta 350 U. S.

879. And we think it equally clear that this right may not be

abridged by the leasing of the parks with ownership re

tained in the state. See Lawrence v. Hancock 76 F. Supp.

1004, 1009; Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n 347

U. S. 971. And it is no ground for abridging the right that

the parks cannot be operated profitably on a non segregated

App. 2

basis. Since the park here could not be operated profitably

on such basis and leasing was being contemplated for that

reason, it was proper to insert in the decree a provision

which would protect the rights of plaintiffs in the event of

lease. Cf. Regal Knitware Co. v. N. L. R. B. 324 U. S. 9,

14-16. As said by the District Judge:

“ The short answer to the argument advanced by de

fendants, that there is insufficient evidence to justify

a permanent injunction based upon future threatened

irreparable injury, lies in the testimony of the Director

(Long) in that he admits that Seashore State Park

cannot be operated profitably on an ‘unsegregated’

basis by the Department o f Conservation and Develop

ment. While this Court is inclined to agree with this

statement, if this be true, it stands to reason that no

individual may operate the park at a profit without

enforcing segregation. Should the successful lessee

elect to admit Negroes only, then the members of the

white race have just cause to complain. If it is operated

for the benefit of only the members of the white race,

the Negroes may complain. Accordingly, the defend

ants are required to elect to operate on a non-discrimi-

natory basis, or, if leased, to see that the park is

operated by the lessee without discrimination.”

There is no merit in the contention of appellants that the

decree appealed from is too vague and indefinite.

Affirmed.

APPENDIX II

FIN AL DECREE OF D IST R IC T C O U R T

This cause came on this day to be heard upon the pleadings

filed herein, the stipulations of counsel, the evidence heard

in open court, and was argued by counsel.

It appearing to the Court that all parties are properly

before said Court and that the plaintiffs have presented a

proper case to enjoin the defendants from denying the use

of the recreational facilities o f the Seashore State Park;

and it further appearing to the Court that the prayer of

said plaintiffs to enjoin the defendants, their lessees, their

agents and their successors in office, from denying to said

plaintiffs and other persons of a similar class and similarly

situated the use and enjoyment of the Seashore State Park

and its recreational facilities is proper;

lit is ADJUDGED, ORDERED and DECREED that

the Department of Conservation and Development of the

Commonwealth of Virginia, its Director, agents, lessees and

successors in office, are hereby permanently enjoined and

restrained from denying any person of the Negro race, by

reason of his race and color, the right to use and enjoy the

facilities at Seashore State Park; it is further ADJUDGED,

ORDERED and DECREED that if said Park or any part

thereof is leased, the lease must not, directly or indirectly,

operate so as to discriminate against the members of any

race{

The Clerk will assess the costs in this proceeding against

the defendants herein, said costs to include an item of $23.10

due to the Court Reporter for her services in preparing the

transcript in accordance with an order of this Court.

(s ) W alter E. H offman

United States District Judge

October 6, 1955

Norfolk, Virginia