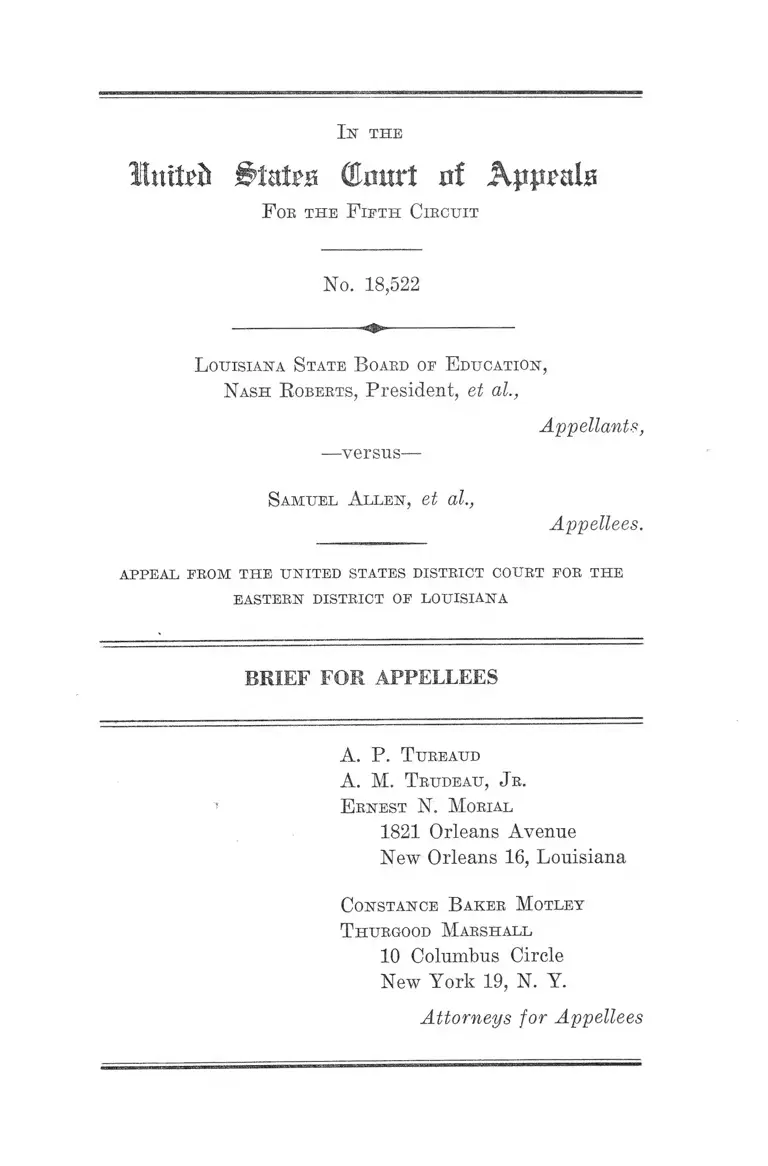

Louisiana State Board of Education v Samuel Allen Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Louisiana State Board of Education v Samuel Allen Brief for Appellees, 1959. eeab44bc-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/89aa3c04-ee90-4149-936c-2ecb711f0264/louisiana-state-board-of-education-v-samuel-allen-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

llnlttb IHatrs ©ami 0! Appeals

F oe t h e F if t h C ir c u it

No. 18,522

L o u isia n a S tate B oard of E d u c a tio n ,

N a s h R oberts, President, et al.,

—versus—

Appellants,

S a m u e l A l l e n , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

A. IJ. T ureaud

A. M. T r u d e a u , Jr.

E rn est N . M orial

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

C o n stan ce B ak e r M o tley

T hurgood M a r s h a ll

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellees

In th e

Mnxtvb States (Emtrt of Appeals

F or t h e F if t h C ir c u it

No. 18,522

L o u isia n a S ta te B oard of E d u c a tio n ,

N a s h R oberts, President, et al.,

—versus-

Appellants,

S a m u e l A l l e n , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Statement of the Case

The Statement of the Case as set forth by appellants in

their brief is not controverted; however, appellees believe

that appellants’ Statement of the Case should be supple

mented by the following facts appearing in the record on

appeal:

The injunctive order entered by the court below, from

which appellants appeal, enjoins appellants:

“ . . . from continuing to enforce a policy, practice,

custom and usage of excluding plaintiffs and other

2

qualified Negro students from the Shreveport Trade

School located in the City of Shreveport, Louisiana,

solely because of their race and color (R. 47).”

One of the affidavits submitted by appellees in support of

their motion for summary judgment has attached thereto

a bulletin of the Shreveport Trade School (R. 32). This

bulletin states as follows:

“ . . . The Shreveport Trade School was created and

established by the Legislature of the State of Louisiana

on July 9, 1936, by House Bill No. 428, Act No. 265,

for the education of the white people of the State of

Louisiana, in Shreveport, Caddo parish, Louisiana,

under the supervision of the State Board of Education.”

(Emphasis added.)

Appellants did not challenge the validity of the docu

ment in which this statement was contained by counter

affidavit or otherwise.

The racial policy of the Louisiana State Board of Educa

tion with respect to the Shreveport Trade School was thus

before the court below on motion for summary judgment.

One of the affidavits of the director of the Shreveport

Trade School, which was submitted in opposition to motion

for summary judgment, admits that on December 17, 1957

appellee Ed. S. Allen made application for admission to

the Shreveport Trade School to pursue a course of instruc

tion in sheet metal work (R. 43).

In opposition to appellees’ motion for summary judg

ment, appellants also submitted the affidavit of one John

Toler, who described himself in his affidavit as secretary of

the Shreveport Sheet Metal Workers Joint Apprenticeship

Committee. In his affidavit, Mr. Toler states that:

“ . . . he has conducted . . . a survey of . . . job open

ings and placements in the sheet metals trade in

3

Shreveport with the various contractors and individual

members of the trade union, and such survey reflects

that no person of the negro race is now employed in

such trade and that no such job opening or placement

presently exists in said trade in Shreveport for such

a person” (R. 45).

Toler’s affidavit was submitted in support of another

affidavit of Jerry Willard Moore, director of the Shreveport

Trade School, who stated in his affidavit:

“ THAT, the policy of this trade school, in accordance

with the Louisiana State Plan for Vocational Educa

tion and the United States Administration of Voca

tional Education, is to admit students for training only

in those areas in which the student has employment

opportunities in the area” (R. 43).

This affidavit of Mr. Moore then stated:

“ THAT, your affiant is familiar with the sheet metal

trade in the Shreveport area, and is familiar with the

employment practices in said trade. In the Shreveport

area there is presently not a single negro engaged in

the sheet metal trade, and absolutely no demand for

negroes to pursue said trade” (R. 43-44).

“ THAT, in view of the employment opportunities as

hereinafter stated, it would be impossible to employ

a negro in the sheet metal trade in the Shreveport

area” (R. 44).

Another affidavit of the director admits that appellee

Green L. Pearrie made application on December 16, 1957 to

be enrolled in the Shreveport Trade School to pursue train

ing as a barber (R. 24). This affidavit alleges that this

applicant was denied admission “because he had not re

ceived prior approval of the Louisiana State Board of

Barber Examiners, said approval being a requisite of the

4

school in order to be admitted” (R. 24). However, the

bulletin of the school sets forth no such requirement in

describing the barbering course (R. 36) .

Other affidavits of the director admit that the other

appellees applied for admission (R. 23, 42).

Upon the hearing of appellees’ motion for summary

judgment, the court below did not immediately grant the

motion. Both parties were given additional time .within

which to submit additional documentary evidence and affi

davits (R. 28). It wasn’t until after these additional affi

davits and the additional documentary evidence was sub

mitted that a summary judgment was granted (R. 46) and

an injunction issued (R. 47).

ARGUMENT

I.

Appellants’ contention that the court below erred in

holding that the Louisiana State Board of Education

could be made a party defendant to this suit is frivolous

and wholly without merit.

In Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156

(5th Cir. 1957), this Court expressly considered the question

whether a .suit against an agency of the State of Louisiana

to enjoin unconstitutional action by such state agency is

such a suit against the State of Louisiana as is prohibited

by the Eleventh Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

This Court held in that case that where a suit does not

seek to compel state action, but merely seeks to prevent

action by state officials which is unconstitutional, such a

suit is not a suit against a state.

5

In that case the state agency sued was a parish school

board. The relief sought was an injunction enjoining racial

segregation in the parish schools.

In Board of Supervisors of L. S. U. ete.’ V. Fleming, 265

F. 2d 736 (5th Cir. 1959), this Court ruled that a. suit

against the Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State Uni

versity, a special agency of the State of Louisiana, was

likewise not a prohibited suit against the state where the

plaintiffs sought to enjoin their exclusion from the state

university solely on account of their race and color.

This Court’s ruling in the Bush case was relied upon by

a three judge district court in Dorsey v. Slate Athletic

Commission (E. D. La. 1958), 168 F. Supp. 149, ail’d 359

U. S. 532 (1959) holding that it had jurisdiction of a suit

against the Louisiana State Athletic Commission, a cor

porate agency of the State of Louisiana, to enjoin the

enforcement of a rule of the Commission and a statute of

the State of Louisiana prohibiting boxing matches between

Negro and white contestants.

The order entered by the court below does not seek to

compel any action by the State of Louisiana. It prevents

action by the State Board of Education of Louisiana, and

its agents, which violates the constitutional rights of appel

lees, i.e., it prevents the State Board of Education and its

agents from continuing to enforce a policy, practice, custom

and usage of excluding appellees and other qualified Negro

students from the Shreveport Trade School solely because

of race and color.

The same type of relief against agencies of the State of

Louisiana was granted in the Bush case, supra, the Fleming

case, supra, and the Dorsey case, supra.

Consequently, the contention made by appellants has

been considered by prior recent decisions of this Court and

6

by the United States Supreme Court in the recent Dorsey

case, supra, and has been decided adversely to appellants’

contention. It is, therefore, clear that the first contention

of appellants on this appeal is so unsubstantial as to be

patently frivolous and wholly without merit.

II.

A summary judgment was properly granted by the

court below.

Appellees supplemented the Statement of the Case made

by appellants in their brief for the reason that the record

in this case discloses that there was clearly no genuine

issue as to any fact material to the question whether appel

lants are enforcing a policy, custom and usage of exclud

ing plaintiffs and other qualified Negroes from the Shreve

port Trade School solely because of race and color.

The appellees’ racial policy was set forth in the official

bulletin of the Shreveport Trade School (R. 32). There

all applicants were put on notice that the institution was

limited to white citizens of the State.

Moreover, the affidavit of the director of the school to

the effect that there was no employment for Negroes in the

sheet metal field in Shreveport, and the affidavit of John

Toler in support thereof, confirmed appellees’ contention

that race was the controlling consideration in the denial of

their admission.

The bulletin also revealed that with respect to the appel

lee who applied for admission to the school in order to take

a barbering course, the reason given for the denial of his

admission was not based on fact. No such qualification, as

Mr. Moore, the director, alleged this appellee failed to meet,

appears in the official bulletin of the Shreveport Trade

School (R. 24, 36).

7

Finally, appellants admitted by the affidavits of the direc

tor of the school that appellees had applied for admission

to certain courses (R. 23, 24, 42, 43) and in no case did

appellants, in their opposition affidavits, challenge the

qualifications of the applicants for admission.

There was, therefore, no genuine issue as to any material

fact and appellees were entitled to judgment as a matter of

law. Board of Supervisors of L. S.U. v. Fleming, 265 F.

2d 736 (5th Cir. 1959); Ludley v. Board of Supervisors of

L. S. V. (E. D. La. 1957), 150 F. Supp. 900, aff’d 252 F. 2d

372, cert. den. 358 U. S. 814; Tureaud v. Board of Super

visors of L. S. V., 116 F. Supp. 248 (E. D. La. 1958), rev’d

207 F. 2d 807 (5th Cir. 1953), vacated 347 IT. S. 971 (1954),

225 F. 2d 434 (5th Cir. 1955), 228 F. 2d 859; Wilson v. Board

of Supervisors of L. S. U 92 F. Supp. 986 (E. D. La. 1950),

aff’d 340 IT. S. 909.

CONCLUSION

For all of the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the

court below should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

A. P. T ureaud

A. M. T ru d e au , Jb.

E rnest N. M ortal

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans 16, Louisiana

C o n stan ce B a k e r M o tley

T hurgood M a r sh a ll

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y. .

Attorneys for Appellees

3 8