Miller v. Continental Can Company Plaintiffs' Reply Brief to Defendants' Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion for Fees and Costs

Public Court Documents

September 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Miller v. Continental Can Company Plaintiffs' Reply Brief to Defendants' Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion for Fees and Costs, 1982. 723b12a6-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/89bec6d6-2f4f-457e-9ba0-e9748d29b920/miller-v-continental-can-company-plaintiffs-reply-brief-to-defendants-opposition-to-plaintiffs-motion-for-fees-and-costs. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

€

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

SAVANNAH DIVISION

x

0Ud3rnJUf*

to if

JL)

{p>J Uxm JL us. ^ V

(b) kX'sforicJl*. OUHUtr

CO (XjIUaxJIaJI

Kr C ^ . *****

*) M aaI J ^ U A /

CHARLIE MILLER, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

-against-

CONTINENTAL CAN COMPANY, et al.,

_i ujueXtdU-* (iixd lcxd to^ .

Io'SLiÛ

Civil Action No. 2803 .

i rn.

De fendants.

x

PLAINTIFFS' REPLY BRIEF TO DEFENDANTS'

OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS' MOTION FOR FEES AND COSTS

Introduction

Before the Court is a motion for an award of fees and

costs for time expended by plaintiffs' attorneys in the

instant litigation through December 1981. (Plaintiffs will

be filing shortly a supplemental motion for fees that will

set forth the hours spent on this litigation during 1982,

and any expenses and costs incurred in connection with those

hours.) As of that date plaintiffs' attorneys had spent

only slightly more than 1200 hours prosecuting a complex

civil rights case that had been pending for more than ten

years when settlement was reached.

Plaintiffs submitted with their motion for fees detailed

affidavits of counsel that set forth their experience and

the nature of the services performed. In addition, pursuant

to informal and formal discovery requests, plaintiffs have

responded to two sets of interrogatories and provided copies

of all available original time records to defendants, among

other requested documents.

Plaintiffs have prevailed against both the remaining

defendants, Continental Can Company, Inc. (the "Company")

and United Paperworkers International Union and its Locals

576 and 638 ("UPIU"), in a case that was vigorously defended,

during a time when the courts were fine-tuning standards of

liability and methods of proof. These evolving standards

ultimately led to motions for reconsideration of the liability

decisions issued August 1976. It is beyond reasonable dispute

that class actions are complex and employment discrimination

case are no less so, particularly in the area of seniority

after the decision in International Brotherhood of Teamsters

v. United States, 431 U.S. 328 (1977) ("Teamsters"). Yet,

plaintiffs were successful in defending against the motions

for reconsideration and in obtaining a total of $225,000 in

backpay for a class of 47 persons.

While neither defendant contests plaintiffs' entitlement

to fees as prevailing parties in this litigation, pursuant

to Title VII 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) and the Civil Rights

Attorney's Fees Award Act 42 U.S.C. § 1988, as amended by

Pub. L. 94-559, the defendants oppose plaintiffs' motion for

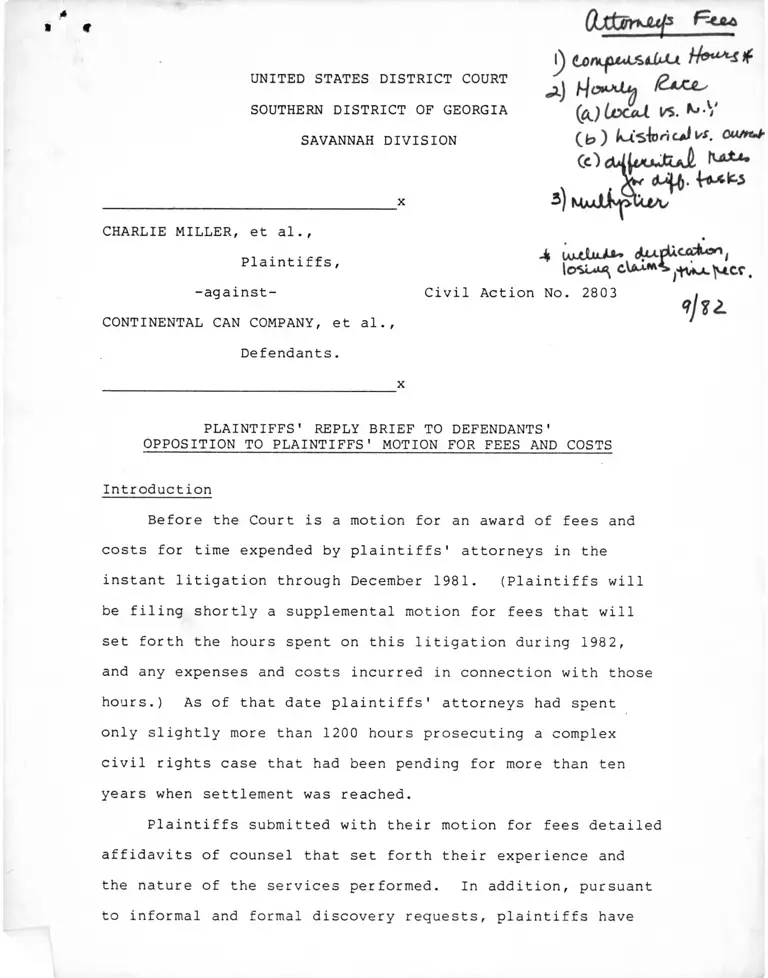

fees with regard to the following issues: (1) Compensable

Hours; (2) Hourly Rate; (3) Use of a Multiplier; and (4)

Costs and Expenses. This reply brief addresses each of

these issues.

I

» I

- 2-

I

(1) Plaintiffs Are Entitled To Be Compensated

For All Hours Requested

In order to determine the fees that should be paid to

plaintiffs' counsel the Court must first establish a lodestar

figure. That figure is arrived at by an examination of the

hours for which compensation has been requested and a sub

sequent setting of the appropriate rate to be applied to

those hours. Fitzpatrick v. Internal Revenue Service, 665

F.2d 327, 332 (11th Cir. 1982). Plaintiffs are entitled to

be compensated at a reasonable rate for all hours claimed in

their motion for fees.

(a) Alleged duplication

The Company contends that all hours of attorneys Sherwood

and Teitelbaum should be disallowed because of duplication.

It also urges the Court to disallow a certain portion of the

time spent by lead counsel, Judith Reed, specifically, that

time it ironically denominates as "catch-up" time, much of

which was spent responding to the Company's motion for re

consideration.

Plaintiffs were opposed by several attorneys from the

prominent Chicago firm of Pope, Ballard, Shepard & Fowle, as

well as local counsel, who represented the Company.—^ UPIU

was represented at trial by local counsel, with post-

Teamsters work being performed by two New York attorneys,

1/ At trial, the transcript reflects that three attorneys,

two from Pope, Ballard plus local counsel, appeared on behalf

of the Company. During the post-Teamsters phase, plaintiffs'

counsel have been in personal contact at one time or another

with no fewer than three other attorneys representing the

Company, in addition to Mr. Ryza (Patricia Brandin, Terry

Satinover, and Alex Barbour).

- 3-

Benjamin Wyle and Gene Szuflita, in addition to local counsel.

In a complex case such as this, with multiple defendants,

for the Company to argue that in the critical post-Teamsters

phase of this litigation it would have been appropriate and

consistent with the requirements of adequate representation

to have had one lawyer assigned to represent plaintiffs

flies in the face of reality. Such an argument would be

entirely inconsistent with the overriding policy of encouraging

the enforcement of civil rights litigation through private

attorneys general. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc.,

390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968) (per curiam). The limited number

of attorneys who worked on this case actually demonstrates

2/an attempt by plaintiffs to avoid duplication of effort.—

At any given stage of this litigation plaintiffs were repre

sented by two lawyers one of whom usually had principal

responsibility for the case; on rare occasions there were

three attorneys. During the pre-trial, trial and immediate

post-trial phase Fletcher Farrington and Mike Bailer performed

3 /virtually all the work on this case.— During the trial,

2/ Plaintiffs have requested, through formal discovery,

information regarding the time spent by defendants in this

litigation, including the number of attorneys and the hours

spent by those attorneys. Thus, far, defendants have refused

to provide any of the requested information, and plaintiffs'

motion to compel this discovery is before this Court. Any

claim by defendants that duplication has occurred should be

measured against the hours expended by defendants. Selzer

v. Berkowitz, 477 F. Supp. 686 (E.D.N.Y. 1979).

3/ The transcript reflects that Bobby Hill was present and

examined certain witnesses; however, the time he seeks to be

compensated for amounts to only 63 hours, much of it expended

after trial of this action.

- 4-

three attorneys were present for the Company, and presumably

the two most active of those attorneys, Mike Warner and Bill

Ryza, expended as much or more time than plaintiffs' attorneys

in this phase, mounting a vigorous defense. UPIU was also

represented by an attorney at this stage.

During the post-Teamsters phase of this litigation,

when the liability judgment was clearly in jeopardy, Judith

Reed and Herbert Teitelbaum were responsible for successfully

protecting the previous liability findings and reaching an

ultimate backpay settlement. Peter Sherwood initially assumed

primary responsibility for the case. Mr. Sherwood, an LDF

attorney and a Title VII litigator who has developed a special

expertise in paper industry seniority issues, seeks compensation

for 7.7 hours at a current rate of $125.00 an hour.—^ Mr.

Sherwood's time should be compensated as productive work,

most of which occurred at a time when Mr. Sherwood was the

only LDF attorney working on the case. The time was necessitated

by the Teamsters decision and the scheduling by the Court of

a May 1978 hearing on this matter. The minimal research

done by Mr. Sherwood was for the purpose of discovery on

Teamster s issues not relevant at the time of the first trial,

and on which the Court had granted the right to take discovery.

4/ Plaintiffs agree with defendants that they are not

liable for compensation for time spent responding to IBEW's

motion for fees. Where time on that motion was inadvertently

included in the original motion, it will be excluded from

corrected calculations that will be filed with this Court in

the near future. Plaintiffs do not agree, however, with the

Company, which contends that all Sherwood's time should be

disallowed or with UPIU's contention that 4.3 hours should

be disallowed.

- 5-

After Ms. Reed joined LDF's staff in July 1978, Mr. Sherwood's

time expended in this litigation dropped considerably. Further

more plaintiffs have not requested compensation for any

intra-office conferences between Sherwood and Reed or the

time spent by Sherwood attending a three-hour settlement

conference with opposing counsel.-/

Herbert Teitelbaum, an attorney with considerable experience

in both general and civil rights litigation, seeks compensation

for fewer than 100 hours. Mr. Teitelbaum's hours were expended

principally in the review of briefs filed in the post-Teamsters

phase (40.75 hours) and two court appearances (27.5 hours)

It is not unusual, and indeed is standard practice, for more

than one attorney to prepare memoranda and briefs in cases

of the degree of complexity found here. The extensive briefing

done on the Teamsters issue was required by the changing

parameters in the law and the fact that the proof in this

litigation spanned close to thirty years. Both defendants

added to the already sizeable record with further evidence.—

The entire record as supplemented had to be analyzed and

responded to by plaintiffs in their briefs.

Mr. Teitelbaum's presence at two court appearances is

5/ It should also be noted that Mr. Sherwood is one of the

attorneys who represented plaintiffs in Meyers v. Gilman

Paper Co., 556 F.2d 758 (5th Cir. 1977), where UPIU was

also a defendant and similar issues raised in the post-

Teamsters phase of that litigation.

6/ Teitelbaum's remaining hours were spent in conferences

with other counsel for plaintiffs (Reed, Bailer or Sherwood)

(11.8 hours), meeting with class members (10 hours) and

negotiating the backpay settlement (7.5 hours).

1_/ The Company submitted the affidavit of the Plant Manager

Claude Adams, while UPIU submitted summaries of collective

bargaining agreements as well as lengthy affidavits by union officials.

- 6-

challenged by both defendants (Co. Memo. p. 14; UPIU Memo,

Schedule C). The first court appearance was the scheduled

argument on the motion for reconsideration (January 16,

1980) . The issues before the court were novel and complex,

and the outcome of that motion was crucial. Hence, plaintiffs

were justified in having both attorneys present. See North

Slope, 515 F. Supp. at 966, n. 21 (supplementary counsel may

be needed where issues are complex and defense counsel able).

In addition, there were two defendants, each represented at

the January hearing by one out-of-town counsel, with the

Company's local counsel also appearing.

During the first court appearance Ms. Reed argued the

motion; however, attorneys Teitelbaum and Reed had conferred

regarding this important argument. At the second court

appearance, Mr. Teitelbaum and Ms. Reed were both active

participants, and the result of that conference, with a

great deal of assistance from the Court's prodding, was the

confirmation of a settlement that defendants had attempted

to retract. It ill behooves defendants to criticize the

relatively small number of hours devoted to settlement of the

backpay issues by either attorney.—^ Had plaintiffs' counsel

not devoted time and energy to reviewing carefully its position

8/ As noted earlier Mr. Teitelbaum devoted 7.5 hours to

settlement and approximately 9 hours to the settlement con

ference called by the court at the request of plaintiffs.

Ms. Reed devoted a total of 31.9 hours to settlement including

9 hours for the court appearance, as well as a number of

hours devoted to negotiating with the defendants on the

degree and the amount of backpay.

- 7-

and weighing the interests of their clients, the result

would have been a Stage II hearing. Such a hearing would

have, doubtless, consumed far more hours of plaintiffs'

counsel, as well as the time of opposing counsel and the

Court.

It is clear that Mr. Teitelbaum's hours are reasonable,

and he performed a valuable role, similar to that of a senior

partner in a law firm. Mr. Teitelbaum efficiently reviewed

court submissions before filing, consulted with Ms. Reed on

litigation strategy, and participated in the settlement

of the backpay issue. The bulk of the work was "appropriately

allocated ... to [a] less experienced [attorney], with review

of that work by the senior attorney." North Slope Borough v.

Andrus, 515 F. Supp. 961, 967 (D.D.C. 1981). See also,

McPherson v. School District #186, 465 F. Supp. 749, 757

(S.D. 111. 1978) and Copeland v. Marshall (Copeland III),

641 F.2d 903 n. 50. (". . . young associates' efforts will

be fully productive only if guided by proper supervision by

9 /experienced litigators.")—

Finally, the Company attempts to justify a percentage

deduction from the hours of Ms. Reed based solely on the

fact that she replaced Mr. Bailer as the LDF attorney assigned

to the case. The Company would have the court assume the

9/ In McPherson, the court approved the compensation of

all hours put by Norman Chachkin, then an attorney with

LDF, despite the fact that he acted in an "advisory" capacity. Id. at 760.

- 8-

fact of duplication, despite the fact that after the decision

in Teamsters, the prospect of a second trial in a case already

seven years old was very real. The Company makes the unsup

ported statement that had Farrington and Bailer remained in

the litigation the total time would be less.— ^

As the Company admits, the time it chooses to subsume

under the term "catch-up" was spent on preparation of

responses to motions for reconsideration filed by the defend

ants.— ^ The review of the record was necessary in order to

provide record cites to that evidence already in the record

that supported a finding of liability under the newer, stricter

12/standard announced under Teamsters.— It is doubtful that

10/ It is not unexpected in protracted litigation for a

change in attorneys to occur. However, where as here, the

attorneys maintain close contact and confer about the case,

the possibility for duplication is minimized.

11/ UPIU contends that time spent in reviewing the record,

meeting with class members and the visit to the Port

Wentworth Plant should be disallowed because it constitutes

duplication. The purpose of this time expenditure was to

determine whether there was evidence bearing on the Teamsters issue, either testimony from class members or of a documentary

nature that should be added to the record. Prior testimony

was developed under a different standard of proof and the

documents inspected at the Plant, which consisted of Company-

union minutes relevant only after Teamsters had not been

produced prior to this time.

12/ In James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings Co., 559 F.2d

310 (5th Cir. 1977), after listing the four factors gleaned

Teamsters, the Court noted that "a case-by-case analysis of

seniority systems in light of section 703(h) is necessary."

The Fifth Circuit went on to suggest the type of evidence

that might be relevant, concluding that the parties should

be given the opportunity to submit additional evidence. Id.

at 352-53.

- 9-

any counsel would have been able to assess whether or not

the record as made before Teamsters was sufficient to support

liability under the new standard, without a thorough review

of that record. While an alternative might have been to do

a less scrupulous review, the result would have been an

evidentiary hearing to clarify the record, with the concomit

ant delay, expansion of the record and a wasting of the time

and energy of the Court and counsel. Instead, based on

their review, plaintiffs' counsel pointed out, successfully,

that the record supported a finding of liability under Teamsters,

entitling the affected class members to substantial backpay.

To the extent that plaintiffs' review was a thorough one,

obviating the need for a further evidentiary hearing on the

matter, the interests of all parties and judicial economy

were served, and plaintiffs' counsel should be compensated

for all time spent on this task.

(b) original time records

Pursuant to a request by the Company, plaintiffs have

produced all available, contemporaneously maintained time

slips from which the exhibits for each attorney's affidavit

were prepared. While neither defendant disputes the accuracy

of the hours and the accompanying description of the work

performed, defendants contend that simply because plaintiffs

were unable to produce time records for all hours worked by

Mr. Bailer there should be a reduction in those hours. (Co.

Mem p. 18.) The exhibit to Mr. Bailer's affidavit was

prepared by reference to time slips kept by Mr. Bailer

- 10-

while he was employed at LDF. Defendants can cite to no

case where the party seeking fees has been disallowed those

fees where specific details on hours have been provided,

simply because original time records have been lost; indeed,

attorneys have been compensated for reconstructed time, see,

e.g., Harkless v. Sweeney Independent School District, 608

F.2d 594 (5th Cir. 1979), aff1g 466 F. Supp. 457 (S.D. Tex.

1978); Hedrick v. Hercules, Inc. 658 F.2d 1088, 1099 (5th

Cir. 1981) (plaintiffs' attorney compensated for 200 hours,

Gautreaux v. Landrieu, 523 F. Supp. 684 (N.D. 111. 1981)

(counsel compensated for estimated time). What is required

from plaintiffs is that their application be "sufficiently

detailed" to enable the Court to reach an informed decision.

National Ass'n of Concerned Vets, v. Secretary of Defense

Case, 675 Fed. 1319 at 1326 (D.C. Cir. 1982); this plaintiffs

13/have provided.— 7 Nor is it appropriate to follow the Company's

suggestion of placing a ceiling on the number of hours for

which Bailer should be compensated by reference to the number

of hours claimed on Farrington's behalf. A considerable

amount of Bailer's time was devoted to time-consuming task

researching and the preparation of briefs. After the last

13/ The cases cited by the Company simply have no relevance

to the instant case application (Co. Memo p. 17, nn. 12 and

13). Inthose cases, the courts indicated disapproval of

records that are "casual, contradictory and confusing"

(Cohen v. Community College of Philadelphia, 522 F. Supp.

879 (E.D. Pa. 1981) at 881) or were vague (Richardson v.

Jones, 1506 F. Supp. 1259 (E.D. Pa. 1981) or that didn't

provide enough information on hours (Wehr v. Burroughs Corp.,

477 F. Supp. 1012 (E.D. Pa. 1979), aff'd on other grounds,

619 F.2d 276 (3d Cir. 1980) .

- 11-

entry for Farrington (12/30/74), Bailer continued to spend

time working on the instant litigation (see entries 9/75

through 10/15/75). Between March 1974 to October 1975, Bailer

expended a total of 122 hours in post-trial briefing and

attempting to work out a settlement

(c) Successful vs. unsuccessful claims

The legislative history indicates that counsel for

civil rights plaintiffs are to be "paid, as is traditional

with attorneys compensated by a fee-paying client, 'for all

time reasonably expended on a matter.'" [Citations omitted].

S. Rep. No. 94-1011 94th Cong. 2d Sess. 5 (1976). As the

Sixth Circuit commented in Northcross v. Board of Education,

Memphis City Schools, 611 F.2d 624, 635 (1979), cert, denied,

100 S. Ct. 2999 (1980) "we know of no 'traditional' method

of billing whereby an attorney offers a discount based upon

his or her failure to prevail on 'issues or parts of

issues. ' /

14/ Based on defendants' notation that the trial lasted

nine days, plaintiffs arrive at a corrected total of 360

hours for which Bailer should be compensated. (This figure

also reflects a deduction of 2.25 hours spent on IBEW's

motion for attorneys' fees on 1/21/74 and the addition of

10.0 hours estimated as Bailer's post-'76 time, including

the preparation of an affidavit in connection with the motion

for fees.) By deducting the 122 hours referred to in the

text, one arrives at the total of about 240 hours, which is

very close to the approximately 218 hours listed in the

exhibit to Farrington's affidavit. To limit Bailer's hours,

would mean that the time spent by plaintiffs' attorneys on

extensive pretrial briefing would go uncompensated.

1_5/ See also Allen v. Terminal Transportation Co., 486 F.

Supp. 1195, 1201 (N.D. Ga. 1980); Davis v. County of Los

Angeles, 8 FEP 244 (N.D. Cal. 1974); Stanford Daily v.

Zurcher, 64 F.2d 680 (N.D. Cal. 1974).

- 12-

In Jones v. Diamond, 636 F.2d 1364, 1382 (1981) cer t.

denied, 453 U.S. 950 (1981). The Fifth Circuit cautioned

against a liberal deduction of the hours expended in pursuit

of issues that were ultimately lost, noting that "in complex

civil rights litigation ... issues are overlapping and

intertwined," and "attorneys must explore fully every aspect

of the case, develop the evidence and present it to the

court." See also United States v. Terminal Transport Co.,

563 F.2d 1016 (5th Cir. 1981) .16/ In Miller v. Carson, 628

F.2d 346, 348 (5th Cir. 1980) the court recognized the

interrelationship of issues:

Because issues may at times be reasonably related,

we reject anything in Nadeau or Sethy which insists

that a district court must always sever an attorney's

work into 'issue parcels' and then assess that work

for purpose of a fee award in terms of the outcome

of each issue standing alone.

See also Tasby v. Wright, Civ. Action No. 3-4211-H (N.D. Tex.,

August 1982); and Dowdell v. Apopka, 521 F. Supp. 297, 301

(M.D. Fla. 1981); Dunten v. Kibler, 518 F. Supp. 1146 (N.D.

Ga. 1981) .

The Company

fee awarded (Co.

hours as well as other issues

to deduct fully 10% of any

while UPIU identifies 12.35

for which an unspecified amount

urges this Court

Mem,, p. 25),

16/ Other circuits have also taken the

should be allowed for

losing issues as well

See, e.g., Manhart v.

652 F.2d 904

Kansas City v

all time expenses

as those spent on

Los Angeles Dept.

position that fees

on nonfrivolous

winning issues.

of Water and Power,

9th Cir. 1981) ____________

Ashcroft, 655 F.2d 848 (8th

2d 5 (1st Cir.

680 (N.D. Cal.

Planned Parenthood Ass'n of

, 675 F.

64 F.R.D.

Cir. 1981); but

1982). Stanford

1974), cited with

cf. Miles v. Sampson

Daily v. Zurcher,

approval in the legislative history, long ago noted that

"... courts should not require attorneys (often working in

new or changing areas of the law) to define the exact para

meters of the courts' willingness to grant relief." _Id. at 684 .

- 13-

of time should be excluded (UPIU Memo, p. 3, Schedule A) ^

Both positions are untenable, and there should be no deduction

with the sole exception of those hours spent on IBEW's motion

for attorney's fees (supra, n. 4).

Plaintiffs commenced this litigation by the filing of a

complaint that alleged a pervasive pattern of discrimination

practiced by the Company and a member of Union defendants

against the class of black plaintiffs. As class counsel,

plaintiffs' attorneys were obligated to investigate and

18/present evidence on all potential claims.— ' None of the

""losing claims" in this case were "clearly meritless" Dowdell,

521 F. Supp. at 301. Rather, this is a case where the losing

claims are not separate causes of action but are "part and

parcel of one matter" (Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d 880,

892 n. 18 (D.C. Cir. 1980)— 7 In addition, it is clear that proof

17/ Defendants claim there should be no compensation for cTaims against former defendants IAM and IBEW, or for time

expended in preparation of the claim that UPIU had breached

its duty of fair representation. The Company makes much of

the fact that the claim of discrimination in supervising and

clerical positions was ultimately lost.

18/ As one commentator has noted:

Class action counsel are ethically bound to

initially pursue all theories which appear

warranted at the outset of the litigation. Unlike

their peers in more pedestrian practice, they are

not able to secure informed consent from their

class 'client' to narrow the action of the easier

issues. These lawyers constitute the backbone of

the Title VII bar, yet are subjected to the largest

disincentives to continue in this capacity.

Ramey, "Calculation of Attorneys' Fees Awards in Title VII

Action Against Private Defendants," 58 J. Urb L. 690, 637

(1981).

19/ UPIU's claim that time shall be deducted for the fair

representation claim has no merit. First, any such time is

- 14-

on the losing claims "overlapped" with the success claims.

Cf. Hardy v. Porter, 613 F.2d 112, 114 (5th Cir. 1980) (while

plaintiffs did not prevail on one separable claim, entitlement

to backpay predicated on the finding the defendant had followed

a practice of discrimination).

Plaintiffs succeeded in proving that discrimination had

been practiced against an identified class of black plaintiffs;

in so doing an award of backpay was obtained. The mere fact

that plaintiffs did not prevail against all defendants or

under each and every legal theory raised initially does not

mean that counsel is not to be compensated for all reasonable

hours. As the court noted in Allen v. Terminal Transport Co.

Inc., 486 F. Supp. 1195, 1201 (N.D. Ga. 1980) aff1d 653 F.2d

1016 (5th Cir. 1981) :

All of the efforts of plaintiffs' attorneys were

necessary and warranted in light of the law at that

time. Indeed, as they note, plaintiffs'counsel would

have been remiss in their duties as representatives

of the class had they not pressed all these allega

tions. The defendants are responsible for the situation

that developed into this action, and in fairness to the

plaintiff class and their counsel, the defendants must

bear the burden of this litigation.

19/ continued

minimal. Secondly, to do so on that or any of the losing

claims would go against congressional policy. See, Maher v.

Gagne, 448 U.S. 122, 133 (1980); H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th

Cong., 2d Sess. 4 n. 7 (1976). Finally, most of the time

spent pursuing the claim against a specific union, was directed

toward proof of discrimination by any union and the pattern

of practice of discrimination at the Company. See, e.g.,

Washington v. Kroger Co., 671 F.2d 1072, 1079 (8th Cir.

1982) (court recognizes that it is not always "practicable"

to separate time between winning and losing defendants.

- 15-

In so holding the court relied on Johnson v. Georgia Highway

Express, 488 F.2d 714, 719-720 (5th Cir. 1974), where the

court noted the fairness of placing the economic burden of

Title VII litigation defendants. In order to prove that

pervasive discrimination existed at the Port Wentworth

Plant, it was necessary to conduct discovery against all

. . 20 / unions with which the Company had bargained.— The fact

that no relief was granted against any unions aside from

UPIU does not mean that any deduction of fees should be

made. See, Disabled in Action v. Mayor and City Council of

Baltimore, ____ F.2d ____ (4th Cir. August 9, 1982) Nos. 81-

1846, -1896, where, in its first ruling on this issue, the

Circuit Court reversed the trial court, holding attorney

20/ It cannot be gainsaid that IBEW has had a history of

discrimination against blacks. For years blacks were totally

excluded from the union. (Grand Secretary Report 1900 Con

vention of IBEW American Labor Unions' Constitutions and

Proceedings. The microfilm Edition Part 1. 1836-1974 Reel

57, D3.) In a number of cases IBEW has been found to have

engaged in unlawful discriminatory practices. Myers v.

Gilman Paper, 556 F.2d 758 (5th Cir. 1977); United States v.

International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Local NoT

38 , 428 F.2d 144 (6th Cir. 1970), United States v. Local

Union No. 212, etc., 472 F.2d 634 (6th- Cir. 1973); Stamps v.

Detroit Edison, et al., 365 F. Supp. 87 (E.D. Mich. 1973);

United States v. Virginia Electric and Power Co., et al.,

327 F. Supp. 1034 (E.D. Va. 1971). Nor was it unreasonable

for plaintiffs to seek to keep the IBEW unions in the litigation

as a Rule 19(a) defendant.

- 16-

time spent on TRO on which they lost should be compensated.

Kennelly v. State of Rhode Island, 682 F.2d 282, 283 (1st

Cir. 1982) (fees awarded for all time despite plaintiffs'

failure to prevail against one set of defendants, the ground

that discovery conducted was necessary part of plaintiffs'

preparation for trial); Syvok v. Milwaukee Boiler Mfg. Co.,

665 F.2d 149 (7th Cir. 1981) (time compensable for all claims,

not clearly severable, since they prevailed on major issues);

Busche v. Burkee, 649 F.2d 509, 521 (7th Cir. 1981) (court

found significant that prevailed on major issues at trial

despite failure to prevail against all defendants or on all

issues).

Nor was the claim of discrimination by the Company in

the selection of supervisory/clerical staff. The findings

of fact made after trial make clear that a prima facie case

existed and the case was initially determined to be unrebutted.

12 EPD 1[ 11,191 at 5480. Until shortly before trial one

found the "inexorable zero", Teamsters 431 U.S. at 342 n.

23. Two witnesses testified on this issue, and the statis

tical evidence alone was sufficient to trigger the pursuit

of that claim.

Plaintiffs would respectfully submit that they are

entitled to recover for all time reasonably spent, including

that time spent pursuing claims against unions other than

UPIU and for time spent on the supervisory/clerical issue,

because plaintiffs prevailed in the "ultimate goal of the

lawsuit." Rivera v. City of Riverside, 679 F.2d 795, 797

(9th Cir. 1982) (plaintiffs awarded fees requested, despite

their failure to prevail against 18 individual defendants).

- 17-

(2) The Hourly Rate

(a) Counsel should be paid at the rate prevailing

in the area in which they practice

In this litigation plaintiffs were represented by

counsel who practice in both New York city and Savannah,

Georgia. (Mike Bailer, formerly with LDF, now practices in

San Francisco, where the rates are comparable.) Plaintiffs

seek rates that would compensate counsel at the rate

prevailing in the geographical area in which they practice,

while defendants oppose this, contending that counsels are

limited to the prevailing hourly rate in the Southern

District of Georgia. The Company cites Chrapliwy v. Uniroyal,

Inc., 670 F.2d 760 (7th Cir. 1982) for the proposition that

computation of out-of-town counsel's rate at a higher level

than that in the district where the case is tried must be

justified by a showing that plaintiffs were unable to secure

local counsel. (Co. Mem. p. 27). The Company deliberately

21/misreads the court's holding on that issue.— The Court

did note that a district court might have the discretion to

21/ Similarly, the Company's reliance on the cases cited as

authority for the "settled proposition" they urge (Co. Memo,

p. 27, n. 19) is misplaced. In most of those cases, the

issue was not squarely before the court, because attorneys

involved were local or nearly so, Neely v. City of Grenada,

624 F.2d 547 (5th Cir. 1980); Cohen v. West Haven Board of

Police Commissioners, 638 F.2d 496 (2d Cir 1980); or the

opinion is silent as to whether attorneys were actually from

out-of-town (Clanton v. Orleans Parish School Board, 649

F.2d 1084 (12th Cir. 1981). In Goff v. Texas Instruments,

429 F. Supp. 973, (N.D. Tex. 1977), the court was awarding

fees to defendants under a Christiansburg standard rather

than that applicable here and the Court was obviously

considering the plaintiff's ability to pay, again a factor

not relevant here. Id. at 978. In McPherson, 465 F. Supp. at 760, Wisconsin counsel was indeed compensated at Illinois

rates; however, the court noted that "any difference between

that rate will be considered in the adjustment factor."

18

inquire as to whether the services might have been performed

by a local attorney, the plaintiff was not required to make

a showing of diligent effort to find local counsel. 670

F. 2d at 768-69. In the instant case plaintiffs found

competent local counsel who, despite his considerable

experience, would have doubtless had difficulty in the

management of a broad based class action litigation, while

at the same time taking care of fee-generating matters in

his practice.— ^ Instead, Mr. Farrington prudently

associated himself with an organization possessing a

"corporate reputation for expertise in presenting and the

difficult questions of law that frequently arise in civil

rights litigation." NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 422

(1963). In addition, LDF was able to provide the financial

resources to "engage in the extensive discovery . . .

necessary to effectively pursue a class action." Dowdell v.

Sunshine Biscuits, Inc., 90 F.R.D. 107, 115 (M.D. Ga.

1981).— / The legislative history recognized the need for

21/ continued

In Brown v. Culpepper, 559 F.2d 274 (5th Cir. 1977) (Co.

Mem. p. 28 n.20) the attorney simply as "Attorney B" was

Charles Stephen Ralston, an LDF attorney who received a

higher rate than "Attorney A," the local attorney.

22/ See, Dowdell v. Sunshine Biscuits, Inc., 90 F.R.D. 107,

115 (M.D. Ga. 1981) where the district court expressed

... its growing concern with the increasing

tendency of some local attorneys to "bite

off more than they can chew" in taking on

employment discrimination cases, particularly

when they undertake to pursue the case in the

form of a class action.

23/ See also Lockheed Minority Solidarity Coalition v.

Lockheed Missiles & Space Co., 406 F. Supp. 828, 830 (N.D.

Cal. 1976), where the Court noted:

19

"fees which are adequate to attract competent counsel, but

which do not produce windfalls to attorneys." S. Rep. No.

1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 6, citing Stanford Daily v. Zurcher,

64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal. 1974); Davis v. County of Los

Angeles, 8 FEP Cases 244 (C.D. Cal. 1974); Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 66 G.T.F. 483 (W.D.N.C. 1975).

Surely, compensating attorneys at the hourly rate that

reflects the high overhead of practicing in New York is in

keeping with the legislative intent. See also Jones v,

Armstrong Cork Co., 630 F .2d 324, 325 (5th Cir. 1980).— ^

To do as defendants suggest would be to penalize plaintiffs

for choosing out-of-town counsel, Dunten v. Kibler, 518 F.

Supp. at 1152 n.5.

23/ continued

Litigation in this area often involves

extraordinarily complex legal and factual

issues that many attorneys would simply be

unable to handle successfully. The important

individual and societal issues at stake in

such litigation may not be adequately protected

unless attorneys possessing the requisite skills

can be induced to take Title VII cases.

24/ Additionally, it should be noted that both defendants

have relied on out-of-town counsel (New York and Chicago) to

mount a proper defense. See Chrapliwy, 670 F.2d at 768 n. 18.

20

(b) Current Rates May Be Applied to

Compensate for Delay in Payment

Plaintiffs have applied for compensation at current

hourly rates without regard to when the work was performed

on the ground that to do so was more convenient than

25/adjusting through use of a multiplier— or directly

adjusting for inflation by reference to the consumer price

26/index.— ' See In re Ampicillin Antitrust Litigation, 81

F.R.D. 395 (D.D.C. 1978):

The rates used are based upon current normal

billing rates, despite the fact that the services

were provided over an eight-year period. This use

25/ see, e.g., National Ass'n of Concerned Vets v. Secretary

of Defense, 675 F .2d 1319, 1328 (D.C. Cir. 1982) ("The

lodestar may be adjusted upward to compensate counsel for

the lost value of the money he would have received resulting

from the delay in receipt of payment. . . ."); Environmental

Defense Fund, Inc, v. Environmental Protection Agency, 672

F.2d 42, 59-60 (D.C. Cir. 1982) ("We agree that there

should be a modest adjustment, in the neighborhood of 15-

20%, to reflect 'benefits to the public from suit' . . . and

the delay in receipt [six months] for services rendered.");

Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F .2d 880, 893 (D.C. Cir. 1980)

(en banc); Northcross v. Board of Education of Memphis

County Schools, 611 F.2d 624, 640 (6th Cir. 1979), cert.denied,

447 U.S. 911 (1980); see also, North Slope Borough v. Andrus,

515 F. Supp. 970 (increase of lodestar by 15% to account for

inflation; Harkless v. Sweeney ISD, 466 F. Supp. 457, 472

(S.D. Texas 1978), aff'd 608 F.2d 594 (5th Cir. 1979)

(prejudgment interest on out-of-pocket costs and expenses);

Morrow v. Finch, 642 F.2d 823, 826 (5th Cir. 1981) (prejudg

ment interest on attorney's fees for end of each historic

period).

26/ See Northcross, 611 F.2d at 640. There are two ways to

compensate for inflation and the lost potential for

investment: through use of the consumer price index or by

use of the prime rate. An explanation of these adjustments

and the results on the rates requested will be submitted

with plaintiffs' supplemental motion for fees.

21

of current rates simplifies the Court's task and

roughly couterbalances the inflatibnary loss suffered by

the attorneys because of the long delay in the recovery

of their fees.

81 F.R.D. at 402. A similar rationale was used by the court

in McPherson v. School District #186, 465 F. Supp. 749

(S.D. 111. 1978) [§ 1988 and ESAA]:

The attorneys here are being compensated for

past services at current rates in order to account

for two factors: first, rising overhead and

expenses have forced attorneys to increase their

fees over the past four years and second, increasing

inflation has reduced the purchasing power of the

dollars earned in a prior year but not received

until the present.

465 F. Supp. at 760. See also, Northcross on remand, ____,

F. Supp. ____ , (Slip. op. at 13. Plaintiffs' counsel have

not received any compensation for work performed in this

litigation begun in 1971. Compensation of plaintiffs'

attorneys at historical rates with no adjustment, will mean

that counsel will not be receiving the "adequate compen

sation" envisioned by the various fee statutes Knighton v.

Watkins, 616 F.2d 795, 801 (5th Cir. 1980), and would

constitute an incentive for defendants to protract

litigation^

27/ UPIU attempts to make the disingenious argument that

Farrington, Hill and Teitelbaum have received much of the

compensation due them. As discussed infra pt. (3)(a), this

argument ignores the fact that LDF has not received any of

the litigation expenses it has advanced for the entire

duration of this lawsuit.

22

(c) A Single Rate Should be Applied

To All Time Expended

The Company proposes a different compensation for work

at "non-legal," such as travel time (Co. Mem., p.20) at a rate

equal to 50% of the historical rate (^d., p.22). Yet, as the

court noted in McPherson, "a lawyer's time is his stock in

trade." 465 F.Supp. at 758. The Company suggests a lower

rate for a category it calls "informal communications," con-

28/ferences with witnesses, meetings and attorney conferences.—

Such a broad category would include much of the preparation

for trial, eventual settlement and devising of legal strategy

for this litigation. The utility of attorney conferences is

obvious, "on the theory that attorneys must spend at least

some of their time conferring with colleagues, particularly

their subordinates, to ensure that a case is managed in an

effective as well as efficient manner." National Assn, of

Concerned Vets., 675 F.2d 1337 (D.C. Cir. 1982). As discuss

ed, in the post-Teamsters phase, attorney conferences and

meetings with class members resulted in avoidance of an

evidentiary hearing and eventual settlement of backpay matters.

Interviewing of witnesses for trial is of course an important

part of trial preparation.

28/ Additionally, the Court would be aided in deciding this matter by information on the manner in which counsel for

defendants were compensated.

23

The legislative history makes clear that counsel

in civil rights cases are to be compensated in the same manner

as, for example, those attorneys handling antitrust and secur

ities litigation. Differential rates are not normally applied

29/m such cases.— Further, in each of three cases cited with

approval in the legislative history, Stanford Daily, Davis, and

30/Swann, the same rate was applied to all work. The time spent

on this litigation was reasonable and should be compensated at

a flat hourly rate for all work performed.

29/ See, e.g., Mills v. Eltra Corp., 663 F.2d 760 (7th Cir.

1981) (flat rates of $150/hour awarded); In re Cenco, Inc., 519

F.Supp. 322 (N.D. 111. 1981) (flat rates of up to $150/hour);

Van Gimmert v. Boeing Co., 516 F.Supp. 412 (S.D.N.Y.

1981)(current flat rates up to $160/hour); Krasner v. Dreyfus

Corp., 90 F.R.D. 665 (S.D.N.Y. 1981) (flat rates of

$65-200/hour); In re Gas Meters, 500 F.Supp. 956 (E.D. Pa. 1980) (flat rates of $50-250/hour); Trist v. First Federal Savings &

Loan Assn., 89 F.R.D. 8 (E.D. Pa. 1980) (flat rate of up to

$150/hour); Charal v. Andes, 88 F.R.D. 265 (E.D. Pa. 1980) (flat

rates of $50-250/hour).

30/ See also, Hedrick v. Hercules, Inc., 658 F.2d 1088 (5th Cir.

1981) ; Harceg v. Brown, 536 F.Supp. 125 (N.D. 111. 1982); Laje v.

R.E. Thomason General Hospital, 502 F.Supp. 185 (W.D. Tex.

1982) , aff'd, 665 F.2d 724 (5th Cir. 1982); Halderman v.

Pennhurst State School and Hospital, 533 F.Supp. 649 (E.D. Pa.

1982) ; cases summarized in 6 Class Action Reports, No. 2 (1980).

24

(3) Plaintiffs are Entitled to a Multiplier

As plaintiffs noted in their fee application

star figure should be enhanced by a multiplier to

for contingency and quality factors.— ^

any lode-

account

(a) Contingency

Only last year, the Fifth Circuit

"[1 lawyers who are to be compensated o

victory expect and are entitled to be

cessful than those who are assured of

of result" (emphasis added:

en banc stated that

nly in the event of

paid more when suc-

compensation regardless

No one Johnson criterion should be stressed

to the neglect of others. However, because the

fee in this case was contingent on success, it

is appropriate for the court to consider Johnson

criterion number six, "whether the fee is.fixed

or contingent." This reflects the provisions

of the ABA Code of Professional Responsibility,

DR 2 106(B)(8), and the practice of the bar.

Lawyers who are to be compensated only in the

event of victory expect and are entitled to be

paid more when successful than those who are

assured of compensation regardless of result.

This is neither less nor more appropriate in civil

rights litigation than in personal injury cases.

The standard of compensation must enable counsel to

accept apparently just causes without awaiting sure

winners.

Jones v. Diamond, 636 F.2d 1364, 1382 (5th Cir. 1981.— ^

31/ Of course, the court,

for delay in payment by the

lodestar be calculated with

rates; however, contrary to

do not seek to "double-dip"

in its discretion, may account

use of a multiplier, should the

reference to unadjusted historical

defendants' suggestion, plaintiffs

for delay.

32/ Failure to consider the contingent nature of a case may Be error. Knighton v. Watkins, 616 F.2d 795, 800-80 (5th

Cir. 1980); Miller v. Mackey International, Inc., 515 F.2d

241 (5th Cir. 1975) .

- 25-

Harris v. City of Fort Myers, 624 F.2d 1321, 1325-1326 (5th

Cir. 1980). Other circuits agree that a contingency is ap

propriate in some cases. Northcross v. Board of Education,

611 F.2d 624, 638-39 (6th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 447 U.S.

911 (1980) (normal hourly rates increased by 10% to reflect

contingency of nonpayment); Manhart v. City of Los Angeles,

652 F.2d 904, 908 (9th Cir. 1981) (1.32 enhancement factor

for complexity, uncertainty and results). Indeed, in two of

the three cases that the legislative history of § 1988 indicates

"correctly applied" the Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express,

Inc. , criteria, a contingency above the hourly base rates

was authorized. Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680,

686-688 (N.D. Cal. 1974); Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 8

E.P.D. 11 9444 at p. 5048 (C.D. Cal. 11974, cited in S. Rep.

No. 74-1011, supra, at 6. Moreover, the same legislative

history states that the amount of the fee should be "governed

by the same standards which prevail in other types of equally

3 2/complex federal litigation, such as antitrust cases," .id.— * &

3 2/ See, e.g. , Lindy Bros. Builders, Inc, v. American Radiator

& Standard Sanitary Corp., 540 F.2d 102 (3d Cir. 1976) (en

banc), cited with approval in Knighton v. Watkins, supra,

616 F.2d at 801; Wolf v. Frank, 555 F.2d 1213 (5th Cir.

1977) (enhancement of 33%).

- 26-

Recent cases in which contingency or incentive awards have

been found appropriate include Wells v. Hutchinson, 499 F. Supp.

174, 211 (E.D. Tex. 1980), an employment discrimination action

against the Texas Agricultural Extension Service and Panola

County in which the court ordered enhancement of the base rate

by a factor of two.

It is apparent on the record that plaintiff

has no obligation to pay attorney's fees and that

plaintiff's counsel's right to a fee would only

be realized through a court award. When plain

tiff's counsel accepted this case, his prospect

of recovery was totally dependent upon victory and

a court award. Moreover, at the outset of the

litigation, it was not at all obvious that plain

tiff, as prevailing party, would be entitled to

attorney's fees.

Id. Keith v. Volpe, 501 F. Supp. 403 (C.D. Cal. 1980) (a challenge

to a highway project filed in 1971 pursuant to § 1983 in which the

court found that "a multiplier of 3.5 properly reflects the con

tingent nature of the case and the quality of counsel's efforts

as well as delay in payment and impact of inflation in making a

total award of attorneys' fees of $2,204,534.99); Carter v. Shop

Rite Foods, Inc., 503 F. Supp. 680, 693 (N.D. Texas 1980) (an

employment discrimination action in which enhancement of 33% and

11% above the $90 per hour noncontingent hourly rate was found

appropriate for two stages of the litigation); Northcross v. Board

of Education of Memphis, supra (10% enhancement of normal hourly

rates in school desegregation action); Parker v. Mathews, 411 F.

Supp. 1059 (D.D.C. 1976), aff'd sub nom. Parker v. Califano, 561

F.2d 320 (D.C. Cir. 1977) (base fee award increased by 25%);

Western Addition Community Org. v. Alioto, C-70-1335 WTS (N.D.

Cal. 1974) (employment discrimination action in which base rates of

- 27-

$100 per hour increased by incentive award of 100%) Thompson

v. Cleland, 74-C-3719 n.d. 111. 1979) (employment discrimina

tion action in which incentive multiplier of 2 used to increase

base rates of between $55-$85 per hour); Kelsey v. Weinberger,

C.A. 1660-73 (D.D.C. 1975) (faculty desegregation suit against

HEW in which 50% enhancement was added to $100 per hour base

rate for all counsel). Defendants concede that this litigation

at the very least took on a contingent aspect after Teamsters.

Thus at a minimum a multiplier should be applied to all post-

33/Teamsters hours.—

Both defendants contend that the fact that LDF were

salaried somehow makes a difference as to contingency. However,

we know of no lawyer employed who does not draw a salary,

partnership share, or other compensation while his firm

prosecutes a case on a contingent basis. To do as defendants

suggest would mean treating salaried public interest attorneys

on a different basis than private practitioners -- contrary

to established law. See, New York Gaslight Club v. Carey,

447 U.S. 54, 70 n. 9 (1980), citing Reynolds v. Coomey, 576

F.2d 1166 (1st Cir. 1978) and Torres v. Sachs, 538 F.2d 10,

13 (2d Cir. 1976) with approval; Harris v. Tower Loan, 609

F. 2d 120 , 123-24 (5th Cir. 1980); Morrow v. Finch, 642 F.2d

823, 825 (5th Cir. 1981); Harkless v. Sweeney, supra,

Northcross, 611 F.2d at 637. Similarly the fact that attorneys

33/ See also Lamphere v. Brown University, 610 F.2d 46,

47 (1st Cir. 1979) (10% enhancement); Gonzales v. Van's

Chevrolet, Inc. 498 F. Supp. 1102 (D. Del. 1980) (enhancement

of nearly 50%); Ste. Marie v. Eastern Railroad Assn., 497

F. Supp. 800 (S.D.N.Y. 1980) (enhancement of 10%); McPherson

v. School District No. 186, 465 F. Supp. 749 (S.D. 111. 1978)

(lead counsel's normal rate increased by $20 per hour).

- 28-

Teitelbaum, Hill and Farrington may have received some compensa

tion does not entirely remove the contingent aspect of this

litigation. As the court noted in Env. Def. Fund, 672 F.2d

at 63-64:

The 'contingency' in question is not whether

[the attorneys retained to litigate the fee

issue on a contingency basis] will recover

under their agreement with EDF, but whether

EDF will recover fees under [the applicable

fee statute].

Thus, throughout this litigation, LDF ran the risk of receiving

no compensation whatsoever if plaintiffs had not prevailed,

and it is sufficient that there was "at least some risk of

failure." Concerned Vets, 675 F.2d at 1333.— ^

(b) Preclusion of other work

As the affidavits of counsel and discovery provided by

applicants have indicated, each of the attorneys for whom

compensation is sought have been precluded from performing-

34/ UPIU makes several other arguments, none of which has

any merit. First, it is argued that somehow because LDF is

an organization that consists of lawyers and non-lawyers, it

is not entitled to fees (UPIU Memo, p. 5, n. 3). The Carey

decision is a complete answer to this patently absurd propo

sition. (Additionally, it may be noted that LDF is chartered

under New York State laws and is authorized to practice law

as a corporation, whose board, incidentally, is composed

primarily of lawyers.) Cf. Watkins v. Mobile Housing Board,

632 F.2d 565 (5th Cir. 1980) Secondly, UPIU contends that

Messrs. Farrington and Hill should be limited to an hourly

rate based on the advances they have received from LDF (i.e.,

$50 and $100 per day). This argument fails on two counts:

it would be tantamount to taking into account the salaries

of public interest attorneys, an action that would clearly

be contrary to established caselaw, see, cases cited in text

and relied upon by the district court in Allen v. Terminal

Transport Co., Inc., 486 F. Supp. 1195, 1199 (N.D. Ga. 1980)

(attorney in private practice, compensated for expenses plus

$30 per hour, held not limited to that amount). In addition,

- 29-

other work, some of which may have been fee-generating, in

the case of private practitioners, such as Farrington, Hill

and Teitelbaum, or some of which may have been equally

meritorious litigation that would have resulted in court

awarded fees. This consideration does not lose force because

LDF is a public interest organization, as the court noted

in West v. Redman, 530 F. Supp. 546, 549 (D. Del. 1982)

("Because funding is limited and demand for representation

exceeds the ability to provide it, decisions must constantly

be made on the costs and benefits of various alternative

time allocations.")

(c) Other Johnson factors

Courts have taken several factors, which are present

here, into account in determining a contingency or incentive

award: (a) contingency, e.g . , Jones v. Diamond, supra, Harris

v. City of Fort Myers, supra; Wells v. Hutchinson, supra;

(b) results obtained, e. g. , Keith v. Volpe, supra; Kelsey

v. Weinberger, supra; (c) the hard-fought and protracted

nature of the litigation, Keith v. Volpe, supra, — ' (d)

34/ continued

as the court noted in Clark v. American Marine Corp., 320

F. Supp. at 711, "[t]he criterion for the court is not

what the parties agreed but was is reasonable." Nor is

UPIU correct in its contention that any amount finally

awarded for Farrington or Teitelbaum's time should be offset

by amounts advanced by LDF, since as stated earlier all money will be paid by LDF.

35/ The factor is decisive in many antitrust cases. See,

e.g., Northeastern Tex. Co. v. A.T.T., 497 F. Supp. 230,

252 (D. Conn. 1980) (30% enhancement); In re THC Financial

Corp. Litigation, 86 F.R.D. 721 (D. Hawaii 1980) (1.4 and 1.5

contingency multipliers); Jezarian v.. Csapo, 483 F. Supp.

383 (S.D.N.Y. 1979) (2.0 and 1.5 enhancement factors); Hew

Corp. v. Tandy Corp., 480 F., Supp. 758 (D. Mass. 1979) (1.25

- 30-

the quality of the representation, e.g., Keith v. Volpe.

36/sjjjpra; and (e) the novelty of the issues, Kelsey v.

Weinberger, supra.

(4) Plaintiffs Are Entitled To Recover All Costs And Expenses

Both defendants choose to ignore unequivocal law of the

Circuit that costs and expenses are recoverable. Jones v.

Diamond, 636 F.2d 1364, 1382 (5th Cir. 1981) (en banc) (and

authorities cited) (expert witness fee); Fairley v. Patterson.

493 F.2d 598, 606 n. 11, 607, n. 17 (5th Cir. 1974) ("Court

costs not subsumed under federal statutory provisions normally

granting such costs against the adverse party, Fed. R. Civ.

P. 54(d) . . ., are to be included in the concept of attorney's

fees," and "In public interest litigation, . . . the.expenses

of preparing and conducting the litigation require direct

out-of-pocket expenditures by a party, which should be com

pletely recoverable") (Title VII case);- see also Harkless v.

Sweeney ISP, supra, 466 F. Supp. at 465, 469-470.— ^

35/ continued

enhancement although counsel had received $58,400 in retainers);

Weiss v. Drew National Corp., 465 F. Supp. 548 (S.D.N.Y.

1979) (15% enhancement); In re Coordinated Pretrial Proceedings

in Antibiotic Antitrust Actions, 410, F. Supp. 680 (D. Minn.

1975) (2.0 and 2.5 enhancement factors.

36/ Quality of representation, along with contingency, is

often cited in antitrust and securities cases. See, e.g.,

In re Gas Meters Antitrust Litigation, 500 F. Supp. 956

(E.D. Pa. 1980) (2,5 multiplier); Charal v. Andes, 88 F.R.D.

265 (E.D. Pa. 1980) (1.5 multiplier); In re Ampicillin Anti-

trust Litigation, 81 F.R.D. 395 (D.D.C. 1978) (1.5 multiplier

In re Equity Funding Corp. of America Securities Litigation,

438 F. Supp. 1303 (C.D. Cal. 1977) (factor of 3); In re

Gypsum Cases, 386 F. Supp. 959 (N.D. Cal. 1974), aff'd, 565

F.2d 1123 (9th Cir. 1977) (factor of 3).

37/ Legislative history of § 1988 is clear. Among the three

cases which Congress considered to have "correctly applied

- 31-

Indeed, the Court of Appeals has held that interest on out-

of-pocket costs and expenses is permitted by § 1988. Gates

v. Collier, 616 F.2d 1268 (5th Cir. 1980), modified on rehearing,

OO /636 F.2d 942 (5th Cir. 1981.— 7 Similarly, plaintiffs are

entitled to recover fees paid to expert witnesses. Berry v.

McLemore, 670 F.2d 30, 34 (5th Cir. 1982), citing Jones v.

Diamond, 638 F.2d 1364, 1382 (5th Cir. 1982).

37/ continued

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express criteria were Davis v.

County of Los Angeles, 8 E.P.D. M 944 (C.D. Cal. 1974), and

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 66 F.R.D.

483 (W.D.N.C. 1975), S. Rep. No. 94-1101, supra, at 6, in

which courts awarded costs and expenses without comment.

The bill's sponsor in the House of Representatives and the

author of the House report plainly explained that "the phrase

'attorney's fees' would include the values of the legal

services provided by counsel, including all incidental and

necessary expenses incurred in furnishing effective and

competent repreentation." 122 Cong. Rec. H. 12159-12160

(daily ed., Oct. 1, 1976) (Rep. Drinan); see also, 122 Cong.

Rec. H. 12150 Z(daily ed., Oct. 1, 1976) (Rep. Anderson,

floor manager).

38/ In contrast, the Sixth Circuit has ruled that certain

out-of-pocket costs and expenses are not permitted under 42

U.S.C. § 1988, but are permitted under Rule 54, Fed. R. Civ.

Pro. and 28 U.S.C. § 1920. Northcross v. Board of Education,

supra, 611 F.2d at 639-640. Rule 54(d) states that "costs

shall be allowed as of course to the prevailing party unless

the court otherwise directs." As we have shown Teitelbaum's

participation in the two court appearances was reasonable

and in accord with the requirement of adequate representation;

therefore, his expenses should be reimbursed by defendants.

With regard to Bailer's expenses, the Company resorts to

precisely the sort of "nit-picking" one judge has stated

should not be "countenanced." Concerned Vets., 675 F.2d

at 1339 (Tamm, J., concurring). The expenses the Company would

disallow amount a total of $15.18. Quite apart from the in

significance of the amount, we would submit that the reasoning

is incorrect. First, the length of the trial necessitated

Bailer's presence away from his home, and it is not unreasonable

that additional laundry expenses would be incurred. The $7.40

taxi expense incurred is rightfully reimbursed as it came at

the end of an uncontested trip to Savannah. The fact that

Bailer chose to go on vacation instead of returning to New York

(where, incidentally, a taxi ride would have been considerably

more costly) is irrelevant.

- 32-

Conclusion

Based on the foregoing and the reasons set forth in

plaintiffs' motion for fees, plaintiffs are entitled to

recover their requested attorneys' fees and costs, in addition

to fees for time expended during 1982 and additional costs

and expenses

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JUDITH REED10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

HERBERT TEITELBAUM

Teitelbaum & Hiller

1140 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10036

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

- 33-