Milliken v. Bradley Supplemental Brief for Respondents Bradley

Public Court Documents

June 14, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Milliken v. Bradley Supplemental Brief for Respondents Bradley, 1972. 7d0213b8-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/89c379a6-26e5-4ae7-8302-12734837d217/milliken-v-bradley-supplemental-brief-for-respondents-bradley. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

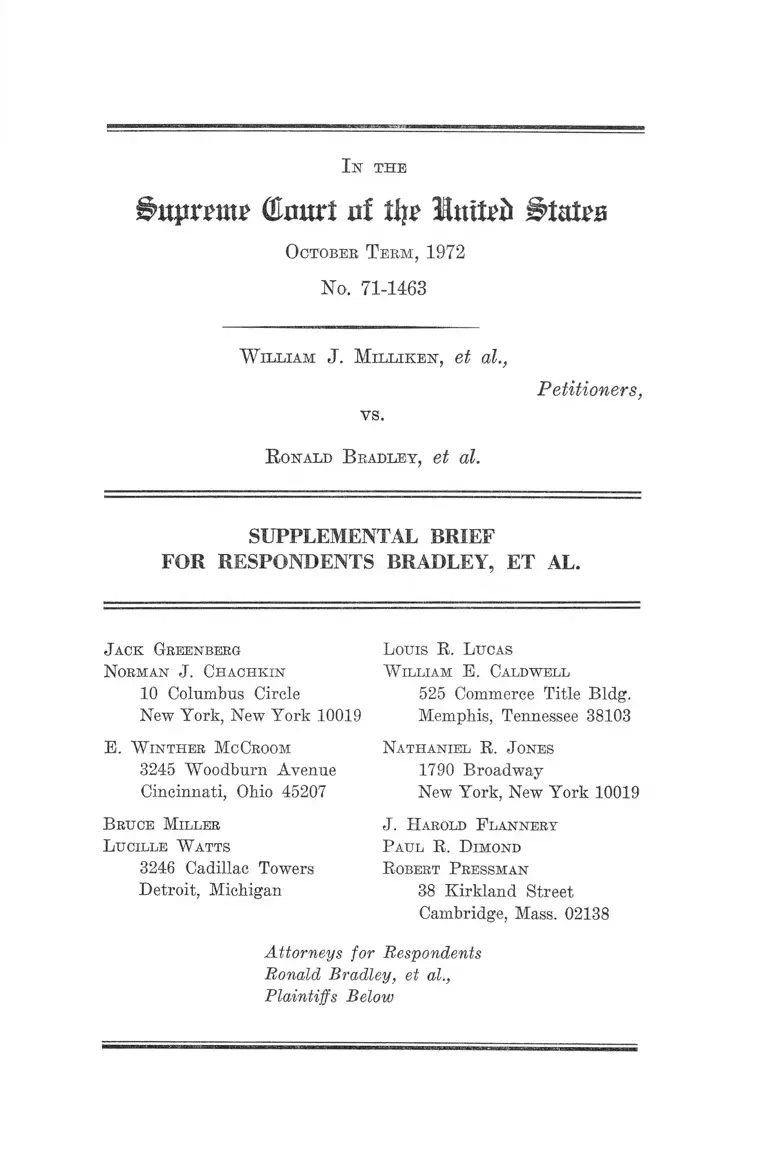

I n the

Glnurt ni % Itttftd States

O ctober T erm , 1972

No. 71-1463

W illiam J. M il l ik e n , et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

R onald B radley, et al.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF

FOR RESPONDENTS BRADLEY, ET AL.

Jack Greenberg

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E. W inther M cCroom

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

B ruce Miller

Lucille W atts

3246 Cadillac Towers

Detroit, Michigan

L ouis R. Lucas

W illiam E. Caldwell

525 Commerce Title Bldg.

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Nathaniel R. J ones

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

J. H arold F lannery

Paul R. D imond

R obert Pressman

38 Kirkland Street

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

Attorneys for Respondents

Ronald Bradley, et al.,

Plaintiffs Below

I n the

(tort of % luttrii States

O ctober T erm , 1972

No. 71-1463

W illiam J. M il l ik e n , et al.,

—vs.—

Petitioners,

R onald B radley, et al.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF

FOR RESPONDENTS BRADLEY, ET AL.

Pursuant to Rule 24(5) of the Rules of the Supreme

Court, respondents Bradley, et al. respectfully file this

Supplemental Brief to advise the Court of proceedings in

this cause before the district court and the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit which have taken

place since the filing, by respondents school districts on or

about June 21, 1972, of a Supplemental Brief and Supple

mental Joint Appendix in support of the Petition. In light

of these proceedings the question properly presented by the

Petition is now moot.

In our Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, pages 6-7, we

noted that the question of appealability of the district

court’s September 27, 1971 opinion and order was likely to

become moot prior to a decision on the merits by this Court

even if certiorari were granted. We now can advise the

Court that such issue is indeed moot at the present time,

and there is no reason to grant the writ of certiorari in this

case.

2

After entry of the district court’s June 14, 1972 ruling

and order, which is the subject of the Supplemental Brief

and Joint Appendix filed last spring by other respondents,

appeals were noted and various interlocutory proceedings

transpired before the Sixth Circuit on matters of stays,

mandamus and prohibition sought by various parties. On

July 20, 1972, the district court entered an order pursuant

to F.R.C.P. 54(b), directing entry of judgment as to certain

claims, and pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b), certifying the

existence of controlling questions of law as to which sub

stantial ground for difference of opinion existed, authoriz

ing appeal of all its previous rulings (dated September 27,

1971, March 24, 1972, March 28, 1972, June 14, 1972 and

July 11, 1972).1 On the same day the Court of Appeals

granted leave to appeal and stayed the July 11,1972 district

court order “ and all orders of the district court concerned

with pupil and faculty reassignment within the metropoli

tan area beyond the geographic jurisdiction of the Detroit

Board of Education, and all other proceedings in the dis

trict court other than planning proceedings” pending ap

peal. (See Appendix A hereto).

The appeal was also expedited and scheduled for hearing

on August 24, 1972; the parties submitted lengthy and

thorough briefs on all issues, including those concerning the

correctness of the September 27, 1971 district court order

and opinion finding unlawful segregation of the Detroit

public schools, as well as the subsequent orders of the dis

trict court concerned with devising a remedy for that con

stitutional violation. At the close of the argument on Au

gust 24, 1972, the Court of Appeals denied an oral motion

to vacate its stay.

1 On July 11, 1972, the district court entered an order directing

the purchase of transportation equipment in order that capability

to implement the Court’s June 14 order might be available during

the 1972-73 school year.

3

Thus the issue presented by the Petition for Writ of

Certiorari is m oot; petitioners have obtained their hearing

before the Court of Appeals and all district court decrees

which might affect the operation of the Detroit area public

schools have been stayed pending the outcome of the appeals

now under submission in the Sixth Circuit. Whatever rea

son might once have existed for reviewing the dismissal of

the prior appeal by the Sixth Circuit, or the orders of the

district court, the proper course at this time is to deny the

Petition and permit the Court of Appeals to complete its

consideration of the matter, which may render unnecessary

any further proceedings before this Court on behalf of

petitioners.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, respondents Bradley et al.

respectfully pray that the writ be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg L ouis R. Lucas

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

W illiam E. Caldwell

525 Commerce Title Bldg.

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

E. WlNTHER McCROOM

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

Nathaniel R. Jones

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

B ruce Miller

Lucille W atts

J. H arold Flannery

P aul R. D imond

Robert Pressman3246 Cadillac Towers

Detroit, Michigan 38 Kirkland Street

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

Attorneys for Respondents

Ronald Bradley, et al.,

Plaintiffs Below

APPENDIX A

#72-8002

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob th e S ix t h C ircuit

R onald B radley, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

W illiam Gr. M il l ik e n , et al.,

Defendants-Appellants,

and

D etroit F ederation op T eachers L ocal 231,

A merican F ederation of T eachers, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Intervenor,

and

D enise M agdowski, et al.,

Defendants-Intervenors.

Before:

P h ill ip s , Chief Judge, E dwards and P eck , Circuit Judges.

O r d e r

The District Court has certified that certain orders en

tered by him in this case involve controlling questions of

law, as provided by 28 U. S. C. §1292 (b), and has made a

determination of finality under Rule 54(b), Fed. R. Civ. P.

2a

Appendix A

This court concludes that among the substantial questions

presented there is at least one difficult issue of first im

pression which never has been decided by this court or the

Supreme Court. In so holding- we imply nothing as to our

view of the merits of this appeal. We conclude that an im

mediate appeal may materially advance the ultimate termi

nation of the litigation. Accordingly, it is O rdered that the

motion for leave to appeal be and hereby is granted.

It is further Ordered that the appeal in this case be ad

vanced on the docket of this court and scheduled for hearing

Thursday, August 24, 1972, at 9. a.m. The appendix and

simultaneous briefs of all parties shall be filed not later

than 25 days after the entry of this order. Reply briefs

shall be filed not later than August 21, 1972. Typewritten

appendix and briefs may be filed in lieu of printed briefs,

together with ten legible copies produced by Xerox or simi

lar process. An appendix must be filed. The court will not

entertain a motion to hear the appeal on the original record.

The motion for stay pending appeal having been con

sidered it is further Ordered that the Order for Acquisition

of Transportation, entered by the District Court on July 11,

1972, and all orders of the District Court concerned with

pupil and faculty reassignment within the Metropolitan

Area beyond the geographical jurisdiction of the Detroit

Board of Education, and all other proceedings in the Dis

trict Court other than planning proceedings, be stayed pend

ing the hearing of this appeal on its merits and the disposi

tion of the appeal by this court, or until further order of

this court. This stay order does not apply to the studies and

planning of the panel which has been appointed by the Dis

trict Court in its order of June 14, 1972, which panel was

charged with the duty of preparing interim and final plans

of desegregation. Said panel is authorized to proceed with

3a

Appendix A

its studies and planning during the disposition of this ap

peal, to the end that there will be no unnecessary delay in

the implementation of the ultimate steps contemplated in

the orders of the District Court in event the decision of the

District Court is affirmed on appeal. Pending disposition

of the appeal, the defendants and the School Districts in

volved shall supply administrative and staff assistance to

the aforesaid panel upon its request. Until further order

of this court, the reasonable costs incurred by the panel shall

be paid as provided by the District Court’s order of June

14, 1972.

Entered by order of the Court.

/ s / J ames A . H iggins

Clerk

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219