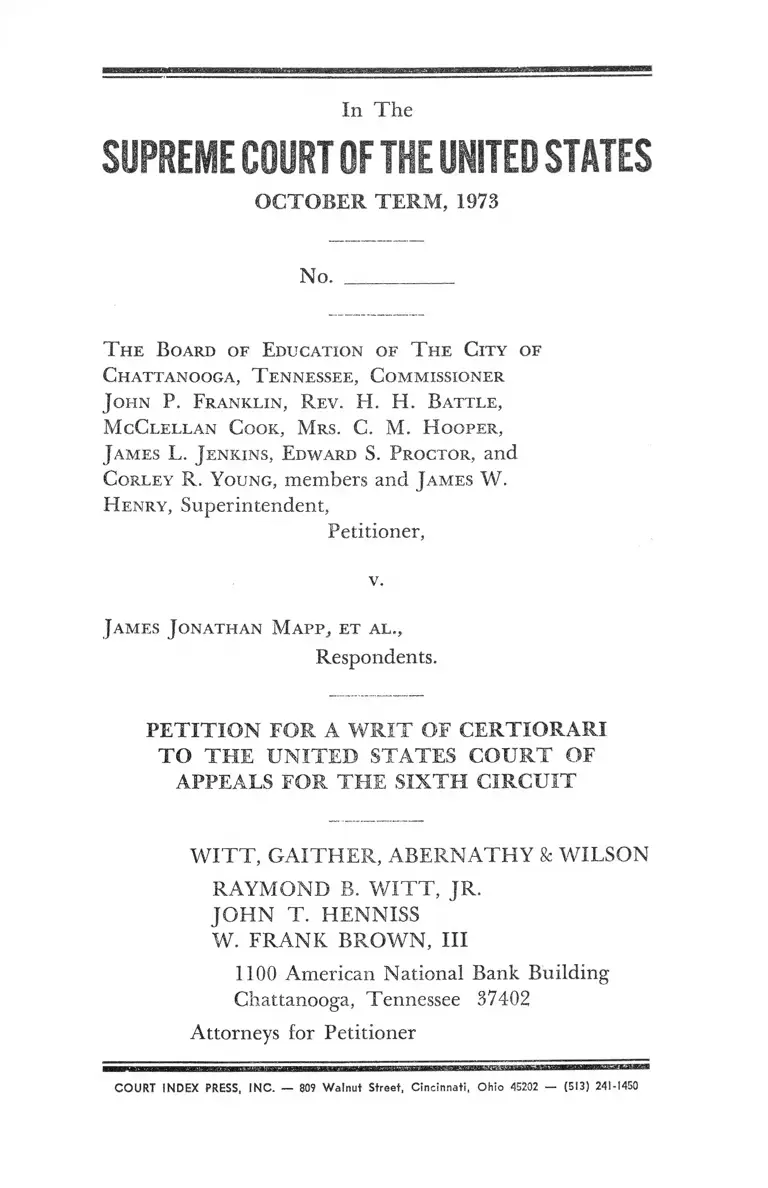

Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga, Tennessee v. Mapp Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (Witt)

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

87 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga, Tennessee v. Mapp Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (Witt), 1973. d4486061-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/89f1d55e-4dfc-46c2-9a9f-e1317319d2a2/board-of-education-of-the-city-of-chattanooga-tennessee-v-mapp-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-sixth-circuit-witt. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

O CTO BER TERM , 1973

N o .__________

T h e B oard o f E d u catio n o f T h e C it y o f

C h a tta n o o g a , T e n n e s s e e , C o m m issio n e r

J o h n P. F r a n k l in , R e v . H. H. B a t t l e ,

M cC l e l l a n C o o k , M r s . C . M . H o o pe r ,

J a m es L. J e n k in s , E dw ard S. P ro cto r , and

C o r le y R. Y o u n g , members and J a m e s W.

H e n r y , Superintendent,

Petitioner,

v.

J a m e s J o n a th a n M a p p , e t a l .,

Respondents.

P E T IT IO N FO R A W R IT OF C ER T IO R A R I

TO T H E U N IT ED STA TES C O U R T OF

APPEALS FO R T H E SIX T H C IR C U IT

W ITT, G A ITH ER , A BERN A TH Y & WILSON

RAYMOND B. W ITT , JR .

JO H N T . HENNISS

W. FRA NK BROW N, III

1100 American National Bank Building

Chattanooga, Tennessee 37402

Attorneys for Petitioner

COURT INDEX PRESS. INC. — 809 Walnut Street, Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 — (513) 241-1450

IND EX

Title Page

IN TRO D U C TO RY PRAYER ....................................... I

OPINIONS BELOW ..................... 1

JU R ISD IC TIO N .......... 2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ........................... 2

STA TEM EN T OF T H E C A S E ........................... 3

REASONS FOR G RA N TIN G T H E W R I T ............... 5

CONCLUSION ..................... 20

APPENDIX:

Opinion of the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Tennessee, 329 F. Supp.

1374 (July 26, 1 9 7 1 )................ 21

Opinion of the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Tennessee, 341 F. Supp.

193 (Feb. 4, 1972 )....................... 50

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit, en banc,--- F .2 d -----(April

30, 1973) 66

II.

TA BLE OF A U TH O R ITIES

Cases: Page

Bradley v. M illiken,----F .2 d---- (6th Cir., 1973) . . . . 12

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (I), 347

U.S. 483 (1954) ................... 6, 10, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (II), 349

U.S. 294 (1955) .......... 6, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18

Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville,

444 F.2d 632 (6th Cir. 1971) . . ................................... 8

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) .............................................. 10, 17

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education

of Nashville and Davidson County, 436 F.2d 856

(1971) ................... ................ .......................................... 12

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado,

41 U.S.L.W. 5002 (1973) ........................... 5, 6, 13, 16

Mapp v. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga,

— F .2d ----(6th Cir. 1973) ................................ . 6

Mapp v. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga,

341 F. Supp. 193 (E.D. Tenn. 1972) ....................... 10

Mapp v. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga,

329 F. Supp. 1374 (E.D. Tenn. 1971) ............... 8, 11

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenhurg Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ............. 5, 6, 7, 8, 14, 15, 16

Other Authorities:

The Supreme Court, 1970 Term, 85 Harvard L.

Rev. 3, 74 (1971) ................................................... 16

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

O CTO BER TERM , 1973

No.

T h e B oard o f E ducation o f T h e C ity o f

C h a tta no o g a , T e n n e sse e , e t a l .,

Petitioner,

v.

J a m e s J o nath an M a p p , e t a l .,

Respondents.

P ET ITIO N FOR A W RIT OF C ERTIO R A RI

TO T H E U N ITED STA TES CO U RT OF

APPEALS FOR T H E SIX T H C IR C U IT

The petitioner, the Board of Education of the City of

Chattanooga, respectfully prays that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgment and opinion of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit entered in

this proceeding on April 30, 1973.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals, not yet reported,

appears in the appendix hereto at pp. 66 to 83. The

opinions of the District Court were rendered on Feb

ruary 4, 1972, 341 F. Supp. 193, and on July 26, 1971,

2

329 F. Supp. 1374, and are printed in the appendix hereto

at pp. 50 to 65 and 21 to 49, respectively.

JU R ISD IC TIO N

The judgment and opinion of the Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit, sitting en banc, was entered on April

30, 1973. No petition for rehearing of that opinion was

filed and this petition for certiorari was filed within ninety

(90) days of April 30, 1973. This Court’s jurisdiction is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Whether the District Court correctly applied the proper

legal standards enunciated in the school desegregation cases

in:

1. Placing upon petitioner the burden of proof (initial

ly going forward with the evidence and the ultimate bur

den) in resisting respondents’ motions for further relief;

2. Confusing the distinction between the right and the

remedy by inferring a status of default solely from admitted

racial statistics without any proof or explanation of such

statistics;

3. Ignoring completely the threshold question as to

the necessity of default as a condition precedent to any

consideration of a remedy, and along with the means per

missible in effectuating an adequate remedy;

4. Ordering the petitioner to maximize integration,

above all other factors, notwithstanding this Court’s un-

s

qualified rejection of racial balance as a constitutional

right; and

5. Construing the legal standards to require that the

burden of proof could be met only by showing Board

decisions (based upon race) made with the specific intent

to maximize integration.

STA TEM EN T OF T H E CASE

The jurisdiction of the District Court was invoked under

28 IJ.S.C. § 1343 (3) upon respondents’ complaint based

upon 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment. This suit was originally

filed on April 6, 1960 by the respondents as a class action

against the Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga,

its members and superintendent, for the desegregation of

the Chattanooga Public School System. Since filing the

original complaint, respondents have from time to time

filed various “ Motions for Further Relief” seeking addi

tional relief, relief often contradictory to the relief sought

previously and relief based upon pleadings inconsistent

with previous findings and opinions of both the District

Court and the Court of Appeals. For example, on March

29, 1965, respondents filed a motion for further relief

asking the District Court to order petitioner to operate its

system “without regard to race.”

The District Court received evidence in April and May

of 1971 upon the respondents' motion for further relief

and motion for immediate relief. Petitioner had the bur

den of proof to show that it was operating a unitary school

system. Notwithstanding the fact that the respondents

made the allegations as to racial discriminatory actions by

the petitioner, the petitioner was forced to have the burden

of initially going forward with the evidence. On the

4

completion of that evidentiary hearing, the District Court

on May 19, 1971 orally ordered the petitioner to file an

amended plan of desegregation which would maximize

integration. That plan was submitted according to the

instructions of the Court. The plan was approved, with

the exception of the high school portion, after a hearing,

and ordered implemented to the extent the Board had

the necessary funds. (The petitioner does not have the

power to raise funds and is dependent upon the City of

Chattanooga for such funds as would be needed to provide

student transportation. The City was not made a party

defendant in this case until January 26, 1972.) From such

approval the respondents first, and then the petitioner,

appealed.

On October 11, 1972, a panel of the Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit voted two-to-one to remand the case

to the District Court. The majority held that the District

Court had erred on the burden of proof issue and stated

several other guidelines for the District Court to follow

in any further hearing upon the cause. Even though the

Court of Appeals had initially refused to grant petitioner’s

suggestion that the case should be heard en banc, the Court

of Appeals voted to hear the case en banc upon the respon

dents’ suggestion after the adverse decision was rendered.

After the rehearing on December 14, 1972, the Court of

Appeals on April 30, 1973 entered a per curiam opinion

in which seven judges voted to affirm the District Court.

Two judges dissented and one judge concurred in the

action of the majority, but did not approve all of the

District Court’s language and opinion. (A more complete

statement of the facts is found in Petitioner’s Brief filed

with the Court of Appeals at pp. 5-16 inclusive.)

5

REASONS FO R G RA N TIN G T H E W RIT

Petitioner respectfully requests the Petition for Writ of

Certiorari issue to the United States Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit because the District Court applied in

correct legal standards by:

(1) Erroneously applying the guidelines in Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklen burg Board of Education, 402 U.S. I

(1971) to the facts in the Chattanooga Public School Sys

tem, and specifically:

(a) in applying the racial balance thrust of the remedy

approved in Swann as the exclusive constitutional criteria

for formerly dual systems, and thus ignoring completely

the threshold question of default by directing attention to

the required remedy without first determining the existence

of a constitutional violation.

(b) emphasizing the supposed constitutional command

to maximize integration, above all other factors, and in

so doing reduced to a nullity this Court’s absolute rejection

of “any particular degree of racial balance” as a constitu

tional right.

(2) In such failure to interpret Swann correctly, the

District Court’s decisions are now in conflict with the de

cision of this Court in Keyes v. School District A'o. 1, Den

ver, Colorado, 41 U.S.L.W. 5002, decided June 21, 1973.

particularly with reference to the nature of the presump

tion created by the presence of schools substantially dispro

portionate in their racial composition, the essentiality of

segregative intent, and the recognition that it is possible to

overcome such presumption of an unconstitutional act and

resulting condition.

(3) As this Court recognized in Swann as a possible

future necessity, school boards now desperately need a

6

further definition of guidelines as to their constitutional

obligation to provide an equal educational opportunity.

The District Court requested clarification on appeal. The

petitioner raised ten issues in addition to those raised by

the NAACP. The en banc decision of April 30, 1973 pro

vided not one sentence of clarification.

Default

The abbreviated chronology that follows, considered

alone, reflects that the District Court did not interpret

Swann as requiring a factual finding of default upon the

part of petitioner as the condition precedent to the necessity

for the second step, that is, what constitutional means are

“ legally tolerable” for a District Court once total default

is found as a fact.

Are the remedial racial means first permitted in Swann

available only where school boards are found to be totally

in default, or is Swann to be read as an expansion of Brown

v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

and 349 U.S. 294 (1955) commanding all formerly statu

tory dual school systems (and now, since Keyes, supra, all

school systems with segregative intent) to enforce racial

decisions as a means available to eliminate racial segrega

tion in public schools?

(The default aspect of Swann is covered in petitioner's

reply brief at pp. 16-22 inclusive as filed with the Sixth

Circuit.)

Chronology

1. On February 19, 1971, the District Court denied

respondents’ motion for summary judgment and set the

case for evidentiary hearing upon respondents’ motion for

further relief filed December 31, 1968 and a motion for

immediate relief on November 14, 1969. As invited by

7

the order of February 19, 1971, petitioner responded by

objecting to the appropriateness of the burden of proof

being placed upon petitioner, particularly when that bur

den was to prove, in effect, that the petitioner Board had

taken the necessary affirmative steps to establish a unitary

school system as to school zones, no zoning in high schools,

transfers, faculty and construction (Joint App. Vol. I, p.

82) . The uncertainty of meaning associated with this

unitary school system concept, in addition to the burden

of proof placed upon petitioner by the District Court,

made the nature of the proof which could be adequate

virtually impossible of achievement. Petitioner requested

a pretrial conference prior to the hearing for purposes of

clarification, but none was held.

2. Following the decision in Siuann of April 20, 1971,

petitioner filed a motion for summary judgment under

Rule 56. The essence of the motion and accompanying

brief was that Swann did not apply to the Chattanooga

school system because it was not in default; and further

that Swann held that decisions made solely or primarily

upon race might be used in desegregation plans only where

the petitioner Board was in default in the sense that the

Charlotte Board was totally in default; and further that

the burden of proof placed upon school boards in default

“ to satisfy the court that their racial composition is not

the result of present or past discriminatory action” on their

part, also did not apply to the Chattanooga Board. (See

explanation of motion for summary judgment beginning at

page 32 of brief for petitioner in the United States Court

of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.)

3. Frequent references during the course of the hearing

by the District Court clearly reflect that no significance was

attached to this motion nor the rationale supporting said

motion by the District Court- To illustrate, references

8

to counsel for petitioner having admitted that the Board

was not in compliance reflected no consideration of the

default contention laid before the Court by the motion

for summary judgment. Such admissions were clearly con

ditional upon a resolution of the default aspect of Swann

as applicable to Chattanooga.

4. The initial decision of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Sixth Circuit following the decision by

this Court in Swann, was on June 22, 1971, Goss v. Board

of Education of City of Knoxville, 444 F.2d 632. The Dis

trict Court Judge filed an order on June 29, 1971 after the

Amended Plan of Desegregation had been submitted to the

Court on June 16, 1971 and attached to such order on

June 29, 1971 a copy of the Goss, supra, opinion. The

Court directed the petitioner to review its plan filed earlier

on June 16, 1971 to the extent the language of Goss, supra,

might appear to be applicable.

5. In response, on July 12, 1971, petitioner filed a mo

tion under Rule 60 (b) asking the Court to vacate and set

aside its orders of May 19, 1971 and June 23, 1971, and

for a rehearing limited to faculty desegregation. Petitioner

interpreted Goss, supra, as action by the Sixth Circuit limit

ing the means approved in Swann to school boards found

totally in default by the District Court Judge. This motion

to reconsider was denied in the July 26, 1971 decision by

the District Court. Mapp v. Board of Education of City

of Chattanooga, 329 F. Supp. 1374 (E.D. Tenn. 1971).

6. In the District Court’s opinion, supra, the following

language was used, reflecting findings of fact and conclu

sions of law.

The Court said, at page 1380:

“The purpose of this lawsuit since its filing in 1960

has been to remove that dual system of schools and

9

replace it with a unitary system in which all vestiges

of racial discrimination have been eliminated. In the

intervening years very substantial progress has been

made. Following appellate guidelines as they then

existed, this Court believed upon each previous occa

sion it entered desegregation orders, first in 1962, then

in 1965 and 1967, that all vestiges of the dual system

of schools would be removed upon fulfilment of its

orders and only a unitary system remain. Experience

and appellate redefinition of the concept of a unitary

school system have now mandated that further steps

be taken to accomplish the full and final desegregation

of the Chattanooga schools.” (Emphasis ours)

At page 1381:

“ It is also appropriate to note in this regard that both

the administrative staff and the Chattanooga Board of

Education are themselves fully desegregated, and this

by voluntary or elective action. The Board of Educa

tion is comprised of seven members. Three of these

members, including the Commissioner of Education,

a duly elected official of the City of Chattanooga, are

black. Four of the Board members are white. Three

of the top school staff officials who testified at the hear

ings held recently were black, including the Assistant

Superintendent of Schools and the Director of Teacher

Recruitment.”

Then at page 1387:

“ Moreover, the evidence is undisputed that the de

fendants have heretofore administered their previous

transfer plan in a manner that was wholly free from

racial or other discrimination.”

Then again at page 1387:

“ There appears to be no purpose in multiplying re

strictions for which no need or justification in fact

exists. A school system that has voluntarily placed a

10

black staff member in charge of teacher recruitment

and assignment needs no Court-imposed restrictions

on potential forms of faculty discrimination which

the record clearly and affirmatively shows it does not

practice.”

7. The above quotes reflect a recognition by the District

Court that appellate courts have given new definition to the

constitutional mandate of Brown I and II.

8. The above quotes are completely inconsistent with

a finding of bad faith or even an intimation of bad faith

upon the part of petitioner Board. Chattanooga is thus

distinguished from Detroit, Nashville and Denver on an

essential - segregative intent.

9. On February 4, 1972 in an opinion, Mapp v. Board

of Education of City of Chattanooga, 341 F. Supp. 193

(E.D. T enn .), the following quote appears at pages 200-

201 :

“Turning finally to the motion for the allowance

of attorney fees for all legal services performed on

behalf of the plaintiffs since the filing of this lawsuit,

the Court is of the opinion that the motion should be

denied. In the absence of a showing of bad faith

on the part of the defendants, the Court is of the

opinion that the allowance of attorney fees would not

be proper. This lawsuit has been in an area where

the law has been evolving, and the Court cannot say

that the defendants have acted in bad faith in failing

always to perceive or anticipate that development of

the law. For example, in all of its orders entered prior

to the decision of the United States Supreme Court

in the case of Green v. School Board of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430, 88 S. Ct. 1689, 20 L.Ed.2d 716

(1968) , this Court was itself of the opinion that gen

uine freedom of choice on the part of students in

school attendance was compliance with the Equal Pro

11

tection Clause of the Constitution. While the Board

has vigorously contested the plaintiff’s contentions at

every stage of this lawsuit, it further appears to the

Court that when factual and legal issues have been

resolved, the Board has at all times complied or at

tempted to comply in good faith with the orders and

directions of the Court. Accordingly, it has never

been necessary for this Court to direct that outside

persons or agencies, such as the United States Depart

ment of Justice or the United States Department of

Health, Education and Welfare, enter into the lawsuit

in aid of the development of a lawful plan of desegre

gation or in aid of enforcement. As recently as in its

opinion entered upon July 26, 1971, the Court had

this to say:

“ ‘The wisdom and appropriateness of this pro

cedure (i.e., looking to the School Board for the

development of a desegregation plan) is further

enhanced in this case by the apparent good faith

efforts of the Chattanooga school authorities and

the School Board to come forward with a plan

that accords with the instructions of the Court

and its order of May 19, 1971, and with the appel

late guidelines therein cited.’

“ Under these circumstances the Court is of the opinion

that an award should not be made taxing the defen

dant Board of Education with the plaintiff’s attorney

fees.” (Emphasis added)

10. The actual findings reflected in the above quotes

cannot be made consistent with a finding of default with

respect to the Chattanooga Board.

11. In an addendum to the July 26, 1971 decision,

Mapp, supra, at page 1388, the District Court had this to

say:

“Although the Court has tried earnestly to -weigh the

evidence and to follow the law, if errors have been

12

made by the Court in what has been here decided,

judicial processes are available to correct those errors.”

12. While the appellate court affirmed the District

Court judge in the en banc hearing which reversed the

decision of the three-judge panel, no clarification or ex

planation was given to the District Court Judge in the

course of the brief opinion. The ten issues raised by

petitioner Board received not one sentence of explanation

or clarification. Nor did the issues raised by the respon

dents. Only the dissent and concurrence developed any

explanation.

13. At the time that the burden of proof was assigned

to petitioner in February of 1971 by the District Court, the

most recent decision in the Sixth Circuit with reference

to Broivn I and II was the case of Kelley v. Metropolitan

Comity Board of Education of Nashville and Davidson

County, 436 F.2d 856 which had been filed during Decem

ber 1970. However, the opinion of the District Court in

Kelley, supra, is replete with unqualified findings of fact

to the effect that the Davidson Board had taken many

actions based upon race for the purpose of creating or

maintaining or resisting desegregation. There is no evi

dence and no factual findings by the District Court with

reference to Chattanooga that can be placed in the same

category as such referenced findings of fact as applicable

to Davidson County.

14. Bradley v. M illiken ,----F.2d —— (6th Cir.) de

cided on June 12, 1973 with reference to the City of De

troit is replete with factual findings to the effect that the

Detroit Board of Education “ formulated and modified at

tendance zones to create or perpetuate racial segregation.”

(Slip Opinion, page 9) It was also found that the Board

in Detroit in the operation of its transportation policy to

13

relieve overcrowding had admittedly bused black pupils

past or away from closer white schools with available space

in black schools (Slip Opinion, page 21) - The Sixth Cir

cuit summed up the constitutional violations of the Detroit

School Board with this language at page 48, Slip Opinion:

“The discriminatory practices on the part of the

Detroit School Board arid the State of Michigan re

vealed by this record are significant, pervasive and

causally related to the substantial amount of segrega

tion found in the Detroit school system by the District

judge.”

Default is obvious, and based upon current board actions

reflecting segregative intent.

15. In Keyes, supra, it is clear that the District Court

found that the Denver School Board “had engaged in over

almost a decade after 1960 in an unconstitutional policy

of deliberate racial segregation with respect to the Park

Hill schools.” 41 U.S.L.W. 5002. There is ample

additional factual findings in the opinions to indicate that

the Denver School Board was making decisions upon the

basis of race for the purpose of creating or maintaining

segregation or minimizing desegregation. The presence

of default is obvious.

16. This Court may not have had before it a factual

situation from a formerly statutory dual school system

which made an initial unqualified commitment to abide

by the mandate of Brown I and II while attempting to

maintain the viability of its school system, and a school

board which could justify the factual findings referenced

above by the District Court and affirmed by the Court

of Appeals by inference.

17. Brown I focused upon the importance of education

with these words:

14

“Today, education is perhaps the most important

function of state and local governments.” (page 493)

18- In Brown 11, with reference to implementation,

school boards were given the following directive:

“Full implementation of these constitutional princi

ples may require solution of varied local school prob

lems. School authorities have the primary responsi

bility for elucidating, assessing, and solving these

problems; courts will have to consider whether the

action of school authorities constitutes good faith im

plementation of the governing constitutional princi-

pies.

19. When the record indicates that a school board has

accepted this responsibility, and has discharged this re

sponsibility in good faith, and has had its efforts in several

stages approved by appellate courts, the harsh and experi

mental means permitted in Swann should not be required

of such board upon the same basis as if it had made no

effort to comply with the Constitution, and when such

means may be inconsistent with the best judgment of the

local school authorities whose responsibility for education

is primary.

20. How can a school board be characterized as in the

posture of default when the trier of the facts specifically

finds said Board to have acted in good faith, and has spe

cifically recognized that the constitutional principles appro

priate to said board have been redefined in a field where

the law is evolving, and this evolutionary aspect of the

constitutional requirement is recognized by the District

Court, appellate judges and by the Supreme Court of the

United States?

21. The evolutionary aspect of the constitutional obli

gation of school boards is reflected in several instances by

language used in Swann. At page 6:

15

“ Understandably, in an area of evolving remedies,

those courts had to improvise and experiment without

detailed or specific guidelines. This Court, in Brown

I, appropriately dealt with the large constitutional

principles; other federal courts had to grapple with

the flinty, intractable realities of day-to-day implemen

tation of those constitutional commands. Their efforts,

of necessity, embraced a process of ‘trial and error,’

and our effort to formulate guidelines must take into

account their experience.”

Then again at page 14:

“ The problems encountered by the district courts and

courts of appeals make plain that we should now try

to amplify guidelines, however incomplete and imper

fect, for the assistance of school authorities and courts.”

22. The partial implementation of the plan approved

on July 26, 1971 has resulted in a school system pre

dominantly black although statistical data would indicate

that the community served by petitioner Board still re

mains predominantly white when all ages are considered.

The fears and the concerns and the uncertainty present in

the Chattanooga system in the last several years is pro

ducing resegregation, and there is continuing evidence in

various areas of the city that the resegregation will con

tinue to move with the overwhelming power of a glacier

to the point where any meaningful desegregation within

the Chattanooga system will be token and without sub

stance as to the equal educational opportunity envisioned

by Brown I and II. Under such circumstances, how the

constitutional rights of the black children in the Chatta

nooga area are to be provided remains an enigma if an

all-black school is unconstitutional.

16

Maximize Integration

The District Court assigned such emphasis to the essen

tiality of student racial ratios, and upon a school-by-school

basis, as to reflect only passing attention to that portion of

Swann where this Court clearly stated that there is no

constitutional requirement for a racial balance in public

education. An examination of the July 26, 1971 opinion

reflects a judicial procedure during the course of the draft

ing of this opinion that is structured in a racial ratio man

ner, and with each school deviation from the 70%-30%

ratio requiring separate analysis and requiring some proof

to justify the deviation from the racial ratio or balance

suggested by Dr. Stolee, the expert witness for the NAACP.

As was made reference to in The Supreme Court, 1970

Term, 85 Harv. L. Rev. at page 83:

‘A district judge faced with pressures for a lesser de

gree of integration might justify his use of percentages

by reference to Swann: since the Court has never ap

proved a plan in which racial percentages varied more

widely, the only way to he sure of compliance with

the constitutional command is to approximate Swann’s

scheme.” (Emphasis ours)

The Burden of Proof

Keyes, supra, makes the intent of the school board the

key factual determination as to the existence of a constitu

tional violation where actual racial student segregation

admittedly exists in a Northern (de facto) school system

(thus a system that has never practiced such segregation

at the direction of a state statute) .

Keyes, supra, requires the plaintiffs to carry the burden

of proving (1) the necessary intent and (2) causal con

nection between such intent and the racial segregation

giving rise to the inquiry. Once these two factors are

17

determined to be present “ in a meaningful portion of a

school system . . . ” such establishes “a prima facie case of

unlawful segregative design on the part of school author

ities” and shifts the burden of proof to school authorities,

to prove such segregation is not the result of intentionally

“segregative actions.” (41 U.S.L.W. 5002 at 5007)

Such principle must admit of (and permit) special cir

cumstances within a single school system where unconsti

tutional segregation and constitutional segregation exist

within that one system. And the sole distinguishing factor

is either the board so intended and so caused the segrega

tion or the board did not so intend.

Intent is the key.

Then take a look at a school board where substantial

racial segregation continues, but where the record shows,

and is unquestioned by both the District Court and the

Court of Appeals, that there has been no intent to create

or maintain such segregation since 1966. And, on the

contrary, the record shows continued effort to achieve

greater desegregation with stability and with due consid

eration of basic educational requirements; and where the

Board did not interpret Green, supra, as a directive to

reverse course and make decisions upon the basis of race

as a remedial necessity. Proof of the absence of such intent

will clear Denver, but not Chattanooga.

Brown I and II condemned racial segregation in public

schools as resulting in inherently unequal educational treat

ment. The presence of state action, coupled with its direct

causal relationship to such segregation, made the Four

teenth Amendment applicable and controlling. Intent was

implicit in state statutes requiring racial segregation. Does

the taint of this pre-1954 intent (expressed in a state law)

continue to contaminate 19 years later despite a major

effort to avoid such objectionable intent, and to remove

the continuing effects of pre-1954 intent, but all the while

18

under severe restrictions as to the practical scope of the

power available to a local school board? Racial segregation

in public schools wherever it is to be found is objectionable

and results in unequal treatment of children. However,

such condition is not per se illegal for state action is a

prime ingredient in order to trigger the protective force

of the Fourteenth Amendment. In addition to state action

there must be coupled a causal connection between such

state action and the complained of racial segregation. Un

less both are judicially found, the racial segregation is out

side the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment and cannot

be characterized as unconstitutional. Unfair? Yes, but

not unconstitutional.

With the affirmance of the District Court’s decisions by

the en banc, per curiam opinion of April 30, 1973, the

Disti'ict Court’s decisions are the only reality as to what

the Constitution and Brown I and II mean to the petitioner

and its constituency. Without consideration by this Court,

the students within the Chattanooga system, and petitioner,

will be denied the opportunity to negate segregative intent

by appropriate proof.

Denver was found to have segregative intent as late as

1970, some 17 years after Brown I. Yet such has not yet

required desegregation of the entire Denver system. And

unequal racial student segregation exists. Petitioner, per

the record, has had no segregative intent since 1966. Such

segregation as continues to exist in petitioner’s school sys

tem remains because of factors over which petitioner had

no control as long as it was under injunctive command to

avoid making decisions with reference to students upon

the basis of race. Such was in response to and as a result

of respondents’ motion for further relief in 1965 requesting

that all decisions be made “without regard to race.”

Petitioner’s actions reflect no intention to maintain

segregation upon its part. Denver’s segregation exists but

19

becomes unconstitutional only if the necessary intent is

found as a fact coupled with the requisite causal connection.

Denver will have adequate time to make preparation to

meet this burden of proof. Petitioner has not had this

opportunity, and without review by this Court, will never

have such an opportunity. Thus the intent of a state legis

lature sometime prior to 1954 will continue to have its

influence even though the petitioner as a Board has not

possessed such intent since 1966, and has attempted to

remove continuing effects of past intent with the tools at

its command.

If petitioner had relied upon the burden of proof aspect

of Swarm as to justification of a plan, such could have had

the effect of waiving the threshold question of default in

Swarm. And this posture would have served also to de-

emphasize the importance of the default aspect. Petitioner

believed its posture to be that of compliance.

Need for Guidance

Petitioner has been committed to compliance since 1955

enduring the hostility such commitment engendered. Peti

tioner seeks clarification of the nature of its constitutional

responsibility based upon the facts existent in the Chatta

nooga community. The April 30, 1973 en banc decision

by the Sixth Circuit overruling an earlier two-to-one de

cision by a three-judge panel indicates that able appellate

judges read the same language and then interpreted such

language in a contradictory manner. With such learned

conflict in interpretation, it is next to impossible for a

board such as petitioner to perform in accordance with the

Constitution. And particularly when certain interpreta

tions if applied would, in the judgment of petitioner, cause

grievous harm to the school system and the quality of the

available educational opportunity.

20

The Chattanooga situation is desperate. Unless clarifi

cation is provided quickly, the confusion will expand, the

mistrust and misunderstanding will spread, resegregation

will accelerate to the point where meaningful desegregation

will not be possible within the system. Unless integration

is defined and clarified as a constitutional goal with volun

tary action an essential element, instead of forced integra

tion, or desegregation, dis-integration of our public school

system will be the result.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, a writ of certiorari should

issue to review the judgment and opinion of the Sixth

Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

RAYMOND B. W ITT , JR .

JO H N T . HENNISS

W. FRANK BROWN, III

1100 American National Bank

Building

Chattanooga, Tennessee 37402

Attorneys for Petitioner

21

A P P E N D I X

U N ITED STA TES D IST R IC T CO U RT

E. D. TENNESSEE, S. D.

Civ. A No. 3564

JAM ES JO N A TH A N MAPP, E T A L„

v.

T H E BOARD OF EDUCATION OF T H E CITY OF

CHATTANOOGA, H AM ILTO N COUNTY,

TENNESSEE, E T AL.

OPINION

(Filed July 26, 1971)

FRANK W. WILSON, Chief Judge.

This case is presently before the Court for settlement

upon a plan that will accomplish full and final desegrega

tion of the Chattanooga, Tennessee public schools in ac

cordance with recent decisions of the United States Supreme

Court and of the United States Court of Appeals for this

Circuit. The case has a lengthy history. A recitation of

that history is set forth in an opinion of this Court en

tered upon February 19, 1971, wherein the Court also

set forth certain guidelines that were to be followed in

conducting further hearings upon the present phase of the

lawsuit. Pursuant to the guidelines referred to, extensive

22

further hearings were held regarding the effectiveness of

prior desegregation plans to accomplish the establishment

of a unitary school system in Chattanooga as that concept

has been defined in recent appellate court decisions, in

cluding the decision of the United States Supreme Court

in the case of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1, 91 S.Ct. 1267, 28 L.Ed.2d 554

(1971) . At the conclusion of the evidentiary hearing on

May 19, 1971, this Court entered an opinion from the

bench finding that previous plans had not succeeded in ac

complishing a unitary school system, basing its finding in

this regard upon the undisputed evidence, and directing

the defendants to submit further plans for the final accom

plishment of a unitary school system in Chattanooga in

accordance with the Swann decision and other recent ap

pellate court decisions. Following the submission of de

segregation plans both by the plaintiff and by the defen

dants, a further hearing was held upon July 19, 1971,

at which evidence was received in support of and in oppo

sition to the respective plans before the Court. Also at

that time argument was received and a decision was re

served upon certain motions pending in the case.

PENDING M OTIONS

Turning first to the pending motions upon which de

cision has been reserved, these include:

(1) A motion by four citizens and residents of Chatta

nooga, Tennessee, to be allowed to intervene;

(2) A motion by the defendants seeking reconsidera

tion of the Court’s findings and order entered May 19,

1971, wherein the Court directed the defendants to sub

mit further desegregation plans; and

(3) A motion by the defendants to strike the plain

tiffs’ objections to the defendants’ desegregation plan.

23

Regarding the motion to be allowed to intervene, the

intervenors assert various objections to the proposed de

segregation plans submitted by the present parties to this

litigation. The relief sought by the intervenors is to be

allowed to present their objections to the desegregation

plans now before the Court, to be allowed to join the Ham

ilton County, Tennessee, Board of Education as a party

defendant, and to establish a uniform racial ratio in the

combined City of Chattanooga and Hamilton County School

Systems. The defendants have raised no objection to the

intervention, but the plaintiffs have objected. Having

considered the briefs and arguments of counsel, the Court

is of the opinion that the motion to intervene must be

disallowed and this for more reasons than one.

In the first place, it does not appear that the motion has

been timely filed. This lawsuit has now been in litigation

for more than 11 years. Extensive hearings and extensive

relief has heretofore been granted and appellate review of

that relief has been had upon three prior occasions. See

Mapp v. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga, D.C.,

295 F.2d 617 (1961) ; D.C., 203 F.Supp. 843 (1962) : 6

Cir„ 319 F.2d 571 (1963); 6 Cir„ 373 F.2d 75 (1967);

D.C., 274 F.Supp. 455 (1967). The present phase of the

lawsuit has been in active litigation for more than a year.

Evidentiary hearings extending over a period of ten days

were completed within the past two months. Both the

plaintiff and the defendants have now submitted desegre

gation plans. The motion to intervene came only seven

days before a hearing was scheduled to commence for final

approval of a desegregation plan which in part, if not in

its entirety, must be implemented in the six weeks that

remain before the opening of school in September 1971.

To allow intervention at this advanced stage of the litiga

tion, particularly intervention which seeks to add new

parties, to litigate the legality as well as the propriety

24

of adding the new parties, and to litigate all relevant

issues regarding a school system not presently before the

Court, could only unduly burden and delay the present

litigation. See Kozak v. Wells, 278 F.2d 104, (C.A. 8,

1960) ; Pyle-National Co. v. Amos, 172 F.2d 425, (C.A.

7, 1949), note, “The Requirements of Timeliness Under

Rule 24 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,” 37

Va.L.Rev. 563.

Insofar as the intervenors seek the right to interpose

objections to the desegregation plans now before the Court

it is believed that all matters in this regard are being vig

orously and extensively contested by the present litigants.

There is nothing in the record or history of this litigation

to indicate any inadequate representation of any relevant

viewpoint regarding any issue that has heretofore been

before the Court or that is now before the Court. Rather,

every issue throughout the long history of this litigation has

been vigorously and resourcefully contested and has been

resolved only by decision of the Court. In 11 years there

has been no significant issue resolved by agreement of the

parties. In this connection it may be further noted that

while the intervenors are critical of the transportation pro

visions in the plans now before the Court, the proposed

relief sought by them would require much more exten

sive transportation than proposed in any plan now be

fore the Court.

Finally, insorfar as the intervenors seek to join the Ham

ilton County Board of Education and to establish a uniform

racial ratio in the combined City of Chattanooga and

Hamilton County School Systems, they appear to be as

serting a new lawsuit based upon new and untested legal

theories. No direct authority has been cited for the con

solidation of two school systems by judicial fiat. Rather,

such matters have historically been left for legislative, ex

ecutive, or political resolution, all as borne out by the

25

numerous statutory citations in the interveners’ briefs, all

of which without exception contemplate resolution by such

means. Although the interventors assert that they do not

seek consolidation, but only a joint unitary school plan, it

does not readily appear how this would differ from con

solidation when it is borne in mind that transportation

and other facilities would be subject to joint use, and that

staff, teachers and students would be subject to inter

change between the systems. Likewise, the geographical,

political or other limitations for determining which school

systems might be joined for such relief is new matter upon

which no prior authority appears to exist. Additionally, the

entire matter of whether the Hamilton County School Sys

tems was or was not itself operating a unitary school sys

tem would appear to be a subject for new litigation.

For all of the foregoing reasons the Court is of the opin

ion that the motion to intervene must be denied.

Taking up next the defendants’ motion seeking reconsid

eration by the Court of its decision upon May 19, 1971,

wherein the Court found that the present Chattanooga

School System was not a unitary one as required by recent

Supreme Court and other appellate court decisions, the

motion is predicated upon the contention that the issue of

whether the Chattanooga schools were unitary had been

decided in the course of previous hearings and was there

fore res judicata. The motion appears to be based largely

upon the recent Sixth Circuit decision in the case of Goss

v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville, Tennessee,

(decided June 22, 1971) 444 F.2d 632. Although that case

spoke of prior court findings of a unitary school system

within the Knoxville schools, and suggested that upon tra

ditional principles of res judicata such findings might con

stitute the law of the case, three matters must be noted

in this regard. First, it must be noted that the Court went

on to conclude: “We believe, however, that Knoxville

26

must now conform the direction of its schools to what

ever new action is enjoined upon it by the relevant 1971

decisions of the United States Supreme Court.” Second,

it must be noted that in the face of prior findings of a uni

tary system, the Court of Appeals nevertheless remanded

the case for redetermination by the District Court of the

unitary school issue “consistent with Swann v. Bd. of Ed.,

402 U.S. 1, 91 S.Ct. 1267, 28 L.Ed.2d 554, and other rele

vant Supreme Court opinions announced on April 20,

1971.” Finally, as noted in the Goss decision, the law in the

field of school desegregation has been in the process of

development over the past 17 years, and concepts once

thought adequate have been replaced by new and more

definitive instructions from the Supreme Court. Findings

of fact and conclusions of law based upon legal concepts now

discarded form no basis for applying the principles of res

judicata or determining the law of the case. The defen

dants’ motion to reconsider will accordingly be denied.

Turning finally to the defendants’ motion to strike the

plaintiffs’ objections to the amended plan for desegregation

submitted by the defendants, it would appear that this

motion might more appropriately be considered in connec

tion with a review of the defendants’ plan upon its merits,

as will be hereinafter undertaken by the Court.

LEGAL GUID ELINES

At the conclusion of the hearing upon May 19, 1971,

the Court in its opinion reviewed the relevant decisions of

the United States Supreme Court and the Court of Ap

peals for this Circuit and set forth the legal guidelines

that should direct the defendant School Board in prepar

ing its plan for further and final desegregation of the Chat

tanooga schools. Without attempting again to repeat in

27

full those guidelines, it does seem appropriate again to

refer to certain of those guidelines.

In the first place, the fundamental proposition bears re

peating that the legal basis for this lawsuit is that pro

vision of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution which requires that no state shall “deny to

any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of

the laws.” This Court is charged with the responsibility of

requiring nothing less of the Chattanooga schools than

full compliance with the Equal Protection Clause. This

Court is permitted to require nothing more of the Chatta

nooga schools than such full Constitutional compliance.

In the second place, full compliance with the Equal Pro

tection Clause of the Constitution requires the elimina

tion from public schools of “all vestiges of state imposed

segregation” and in this connection “ the burden upon

school authorities will be to satisfy the Court that their

racial composition (z. e., the racial composition of each

school) is not the result of present or past discrimination

upon their part.” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 91 S.Ct. 1267, 28 L.Ed.2d 554

(1971) . The responsibility of the Court is to assure that

the Chattanooga schools “operate now and hereafter only

unitary schools,” that is, schools “ in which no person is

to be effectively excluded from any school because of race

or color.” Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U.S. 19, 90 S.Ct. 29, 24 L.Ed.2d 19 (1969) .

In the third place, while freedom of choice in matters

of school attendance may have appealing features, “ if it

fails to undo segregation, other means must be used to

achieve this end” and “ freedom of choice must be held

unacceptable.” Green v. County School Board of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430, 88 S.Ct. 1689, 20 L.Ed.2d 716

(1968).

28

Finally, it should be remembered that the initial re

sponsibility for devising and implementing constitutionally

adequate plans for the full and final desegregation of the

Chattanooga schools lies with the school authorities and

that “judicial authority enters only when local authority

defaults.” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Edu

cation, supra. It should accordingly be the purpose of the

Court to leave unto the School Board the maximum discre

tion and responsibility for all phases of the operation of the

Chattanooga Public Schools, limited only by constitutional

requirements. Absent a constitutional violation, the wis

dom or lack of wisdom of any plan or policy established

by the Board is not a proper subject for judicial interven

tion or direction. The Court should not substitute its

judgment for that of the School Board in areas where the

exercise of judgment does not violate some principle of the

law. Mapp v. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga,

D.C., 203 F.Supp. 843 (1962), aff. 6 Cir., 319 F.2d 571.

PLANS FOR T H E FINAL DESEGREGATIO N OF

T H E CH ATTANO O GA SCHOOLS

Before undertaking an analysis and evaluation of the de

segregation plans submitted by the respective parties, a

statement of certain relevant historical matters and back

ground data regarding the City of Chattanooga and its

schools would be helpful. The City of Chattanooga, lo

cated upon the southeastern border of the State of Tennes

see, was a part of the Southern Confederacy during the War

Between the States. Although the City in modern times

has become one of the most progressive and forward look

ing cities of the South, traditions of the past have their

role and their influence. Memories of the past linger,

with innumerable historical monuments marking the sites

of some of the most significant events of the War Between

29

the States and with the City’s rich lore of history being

recalled by such names and places as Missionary Ridge,

Lookout Mountain, Signal Mountain, Orchard Knobb, and

Chickamauga Battlefield. Among other traditions inherited

from the past, the City inherited the practice of operating

a dual system of schools for its black and white citizens.

Pursuant to the decision of the United States Supreme

Court in the case of Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686, 98 L.Ed. 873 (1954), this lawsuit

was instituted. The purpose of this lawsuit since its filing

in 1960 has been to remove that dual system of schools

and replace it with a unitary system in which all vestiges

of racial discrimination have been eliminated. In the in

tervening years very substantial progress has been made.

Following appellate guidelines as they then existed, this

Court believed upon each previous occasion it entered de

segregation orders, first in 1962, then in 1965 and 1967,

that all vestiges of the dual system of schools would be

removed upon fulfillment of its orders and only a unitary

system remain. Experience and appellate redefinition of

the concept of a unitary school system have now mandated

that further steps be taken to accomplish the full and final

desegregation of the Chattanooga schools. As reflected by

the undisputed evidence, a number of the Chattanooga

schools remain racially identifiable.

Turning to certain relevant data, it may first be noted

that the City of Chattanooga, according to the 1970 census,

has a population of 118,661 persons. Of these 43,199

or 36.4% were black. These population statistics reflect

that even in the face of some annexation by the City,

there has been a net decline in the City’s population since

1960 of 11,321 persons with all but 27 of this decline being

in the white population. In the 1970-71 school year, the

total school enrollment was 25,967 students. Of this total,

30

12,669, or 48.8% were black students and 13,298, or 51.2%

were white students.

At the time of the recent evidentiary hearing upon the

issue of compliance, the plaintiff submitted a plan for the

desegregation of the Chattanooga schools. That plan is set

forth in Exhibits 124 thru 135. In essence the plaintiff’s

plan calls for the establishment of a racially balanced

faculty and staff in each school and the establishment of

racial ratios among students in each school, with no school

having less than 30% nor more than 70% of one race. The

racial balance of faculty and staff in each school is to be

accomplished by administrative assignment. The racial

ratios among students is to be accomplished by rezoning,

pairing, grouping and clustering elementary schools, by

rezoning and reordering the feeder systems into the junior

high schools, and by rezoning of the high schools. Extensive

transportation of students, both to contiguous and non

contiguous school zones, would be required to effectuate

the plaintiff’s plan.

As stated in the legal guidelines set forth above, the initial

responsibility for devising and implementing constitution

ally adequate plans for full and final desegregation of the

Chattanooga schools lies with the school authorities. Ac

cordingly, before giving further consideration to the plain

tiff’s desegregation plans, it is appropriate that the Court

should first turn its attention to the defendants’ plan for

desegregation of the Chattanooga schools. The wisdom

and appropriateness of this procedure is further enhanced

in this case by the apparent good faith efforts of the Chatta

nooga school authorities and School Board to come forward

with a plan that accords with the instructions given by the

Court in its order of May 19, 1971, and with the appellate

guidelines therein cited. It is also appropriate to note in this

regard that both the administrative staff and the Chatta

nooga Board of Education are themselves fully desegregated,

3 1

and this by voluntary or elective action. The Board of

Education is comprised of seven members. Three of these

members, including the Commissioner of Education, a

duly elected official of the City of Chattanooga, are black.

Four of the Board members are white. Three of the top

school staff officials who testified at the hearings held re

cently were black, including the Assistant Superintendent

of Schools and the Director of Teacher Recruitment.

Turning to the defendants’ plan, a few words in regard

to its organization are in order. The plan, as set forth in

Exhibit 146, consists of an introduction, stating policy,

Paragraphs 1 thru VIII, stating the plan, and Appendices

A and B, setting forth the statistical justification and illus

trating the plan. Illustrative school zoning maps for the

elementary, junior high and high schools are shown in Ex

hibits 143, 144, and 145 respectively.

No criticism of the enrollment projections set forth in

Paragraph I of the plan are made by the plaintiff and none

are found by the Court. This portion of the plan is ac

cordingly approved.

Paragraph II of the plan, when read in conjunction with

the statistical data set forth in Appendix A and the illus

trative matter set forth in the school attendance zone maps

(Exhibits 143, 144 and 145) defines the new proposed

student attendance zones and sets forth the methods pro

posed for accomplishing full and final student desegregation.

The sufficiency of [sic] insufficiency of these proposals can

best be determined by considering the elementary, junior

high and high school plans in order.

Elementary Schools

During the school year 1970-71, the Chattanooga School

System operated 33 elementary schools. Of the ten former

black elementary schools within the system, four remained

32

all black and a total of only 30 white students attended the

other six. In the 23 former white elementary schools there

were 13,250 white children and 3,446 black children. Four

former white elementary schools (Cedar Hill, Normal Park,

Pineville, and Rivermont) remained all white. Barger had

only two black students and East Lake had only three black

students. Two former white elementary schools (Avondale

and Glenwood) had changed to all black schools, having

only three white students between them. The remainder

of the former white elementary schools had ratios of black

students varying from a low of 4% to a high of 64%.

The School Board proposes the accomplishment of a

unitary system within the elementary schools by the closing

of five elementary school, by the pairing of 16 elementary

schools, by the clustering of six elementary schools, by the

rezoning of three elementary schools, leaving the attendance

zones of only three elementary schools unchanged. The

overall result of the defendants’ plan is to achieve a racial

ratio of not less than 30% nor more than 70% of any race

in each elementary school within the system with but five

exceptions (Barger-20% black and 80% white; Carpenter

86% black and 14% white; Long—16% black and

84% white; Rivermont-12% black and 88% white; and

Sunnyside—15% black and 85% white). These five schools

will be discussed further shortly.

Turning first to the five elementary schools that are

proposed for closing, three were substantially all black

last year (Davenport, Glenwood, and Trotter), one was

substantially all white last year (Cedar H ill), and the fifth

(Amnicola) had a majority of black students but was quite

small. No meritorious objections are believed to have been

raised by the plaintiffs to the selection of schools for closing.

Furthermore, their closing contributes to the overall plan

for desegregation and sound fiscal, safety, and administra

33

tive reasons were given by school authorities for each school

so selected for closing.

With regard to the five elementary schools that will

retain racial ratios of less than 30% or more than 70%

of one race, the Court is of the opinion that the Board has

carried the burden of establishing that their racial compo

sition is not the result of any present or past discrimination

upon the part of the Board or other state agency. Rather,

such result is the consequence of demographic and other

factors not within any reasonable responsibility of the

Board.

Barger, having a proposed racial ratio of 20% black and

80% white, is paired with Sunnyside with the effect of

giving that school a racial ratio of 15% black and 85%

white. These schools, particularly Sunnyside, are located

in an area of the City where the residential patterns are

rather rapidly becoming more black. The completion of

housing projects now in progress in the area will speed up

this trend. No purpose of discrimination appears with

regard to pairing of these two schools. Rather, sound plan

ning for the elimination of racial discrimination supports

the plan of the Board in this regard.

Carpenter, having a proposed racial composition of 86%

black and 14% white, is located within a sizeable area of

the City that has a heavily black private residential pattern.

Further, due to commercial expansion and expansion of

the University of Tennessee within this area, and the con

sequent decline of elementary students, Carpenter is sched

uled for closing within one or two years. Not only will

time shortly remove any problem at Carpenter, but the

inclusion of the school in some pair or cluster at this time

would only serve to shortly impair the overall plan.

Elbert Long, having a proposed racial ratio of 16% black

and 84% white, is located on the eastern extremity of the

34

City. It is located within a sizeable area of the City having

a private residential pattern that is substantially white.

There are no contiguous areas having a significant number

of blacks, other than possibly areas outside the present

municipal limits. Any significant annexation that may

occur is likely to occur within this area and will include

additional blacks. No purpose of discrimination appears

regarding the zoning of this school.

Much that has been said regarding the Elbert Long

School, which is also true of the Rivermont School, which

under the defendants’ plan will have a racial ratio of 12%

black and 88% white. This school is located in the northern

extremity of the City, and was recently acquired from the

County by annexation. At the time it was acquired, it was

all white and remained all white during the past school

year. T o accomplish desegregation the defendants propose

to close Amnicola School, which is located across the Ten

nessee River, and place those students in Rivermont. This

involves transportation of students for a substantial distance,

but is nevertheless the nearest area having any significant

black residential population. No purpose of discrimination

appears regarding the consolidation and rezoning of these

schools.

All 27 of the remaining elementary schools not hereto

fore discussed will have racial ratios of not less than 30%

nor more than 70% of any race in each school. The Court

has carefully reviewed the treatment proposed for each

school, together with all statistical demographical and other

data available in the record. To the extent that any student

racial imbalance exists in any of the elementary schools, the

Court is of the opinion that the Board has carried the bur

den of establishing that such racial imbalance as may remain

is not the result of any present or past discrimination upon

the part of the Board or other state agency. Rather, such

35

limited racial imbalance as may remain is the consequence

of demographical, residential, or other factors which in no

reasonable sense could be attributed to School Board action

or inaction, past or present, nor to that of any other state

agency.

The Court is accordingly of the opinion that the de

fendants’ plan for desegregation of the Chattanooga elemen

tary schools will eliminate “all vestiges of state imposed

segregation” as required by Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklen-

burg Board of Education, supra. Under these circum

stances, it is accordingly not necessary for the Court to

consider other or alternate plans. Likewise it would not be

proper for the Court to pass judgment upon whether an

other plan would accomplish a “better” result from the

viewpoint of educational policy and apart from any issue

of legality.

Junior High Schools

During the school year 1970-71, the Chattanooga School

System operated 12 junior high schools. Of the four former

ly black junior high schools within the system, two remained

all black and a total of only 9 white students attended the

other two. In the eight formely white junior high schools,

there were 3,341 white students and 908 black students.

One formerly white junior high school (East Lake) had

only one black student. The remainder of the formerly

white junior high schools had ratios of black students

varying from a low of 8% to a high of 70%.

The School Board proposes the accomplishment of a

unitary system within the junior high schools by closing

two junior high schools and by rezoning the remaining ten

junior high schools, tying them into the restructured ele

mentary school system. The overall result of the defendants’

plan is to achieve a racial ratio of not less than 30% nor

36

more than 70% of any race in all but three junior high

schools. Those three schools are Hardy, with 73% black

and 27% white, Dalewood, with 29% black and 71%

white, and Long, with 15% black and 85% white. Further

discussion will be given to these three schools.

Turning first, however, to the two junior high schools

that are proposed for closing, one is a former black school

and the other is a former white school. The former black

school, Howard Junior High School, was all black last year.

The former white school, Lookout Junior High School,

was 37% black and 63% white last year. No objections

were raised by the plaintiffs to the selection of schools for

closing. The Board represents that the closing of Howard

Junior High School was necessary to the effectiveness of

their overall plan. They represented that the closing of

Lookout Junior High School was necessary in order to

obtain desegregation of Alton Park Junior High School,

one of the former all black junior high schools. Alton Park

is stated to be a new school with greater capacity, whereas

Lookout is one of the older and smaller junior high schools.

Furthermore, financial economies, along with optimum

development of quality instruction programs, were given

as additional reasons for the selection of the junior high

schools to be closed.

Turning to the three junior high schools that will retain

a racial ratio of less than 30% or more than 70% of one

race, Hardy Junior High School is expected to have a ratio

of 73% black and 27% white. Until 1965 Hardy was an

all white school. Changing residential patterns have gradu

ally changed the racial composition of the school to its

present pattern. The proposed zone for Hardy is bounded

by obstacles to its enlargement, including Missionary Ridge

on the east, the Tennessee River on the west, the city limits

on the north, and predominantly black residential areas on

37

the south. Under all of these circumstances, the Court is of

the opinion that the Board of Education has carried the

burden of establishing that such racial imbalance as remains

at Hardy Junior High School arises from conditions beyond

the responsibility of the Board and is not the result of any

present or past discrimination on the part of the Board or

of any state agency.

Dalewood Junior High School, a former white school,

is expected to have a ratio of 29% black and 71% white

under the present plan. However, the trend in residential

patterns in the zone is toward increasing the black popula

tion. Apartments now under construction will shortly

increase the ratio of black students to a point in excess of

30%. No purpose of discrimination appears in the zoning

of the Dalewood Junior High School.

The final junior high school having a ratio in excess of

70% is the Elbert Long Junior High School. Under the

defendants’ plan this school will have a racial composition

of 15% black and 85% white. Everything that the Court

has heretofore said in regard to the Elbert Long Elementary

School is applicable to the junior high school. Additionally,

the Elbert Long junior High School is the smallest junior

high school in the system, having an enrollment of only

166 students.

All of the remaining junior high schools not heretofore

discussed will have ratios of not less than 30% nor more

than 70%, of any race in each school. The Court has care

fully reviewed the proposed racial composition of each

school and all of the relevant statistical, residential, demo-

graphical, and other data available in the record. The Court

has also considered the manner in which the junior high

schools are tied into the elementary school plan which the

Court has hereinabove approved. In this connection the

Court cannot overlook the fact that it is a matter of great

importance to proper school administration that school

38

authorities be able to make reasonably reliable forecasts

of school enrollments. T o do this there needs to be a

carefully devised system of feeder schools. In the light of

all the record, the Court is of the opinion that the junior

high school plan as submitted by the defendants removes

all state created or state imposed segregation. T o the extent

that any student racial imbalance exists in any of the junior

high schools, the Board has carried the burden of estab

lishing that such racial imbalance as remains is not the

result of any present or past discrimination upon the part

of the Board or upon the part of other state agencies.

Rather, such limited racial imbalance as may remain is the

consequence of demographical, residential, or other fac

tors which in no reasonable sense could be attributed to

School Board action or inaction, past or present, nor to

that of any other state agency. The Court is accordingly

of the opinion that the defendants’ plan for desegregation

of the Chattanooga junior high schools will eliminate “all

vestiges, of state imposed segregation” as required by the

Swann decision. It is accordingly unnecessary to consider

other or alternate plans.

High Schools

During the school year 1970-71, the Chattanooga School

System operated five high schools. These included four

general curricula high schools and one technical high school.

Kirkman Technical High School offers a specialized cur

ricula in the technical and vocational field and is the only

school of its kind in the system. It draws its students from

all areas of the City and is open to all students in the City

on a wholly nondiscriminatory basis pursuant to prior

orders of this Court. Last year Kirkman Technical High

School had an enrollment of 1218 students, of which 129

were black and 1089 were white. The relatively low en

39

rollment of black students was due in part to the fact that

Howard High School and Riverside High School, both

of which were all black high schools last year, offered many

of the same technical and vocational courses as were offered

at Kirkman. Under the defendants’ plan these programs

will be concentrated at Kirkman with the result that the

enrollment at Kirkman is expected to rise to 1646 students,

with a racial composition of 45% black students and 55%

white students. No issue exists in the case but that Kirkman

Technical High School is a specialized school, that it is

fully desegregated, and that it is a unitary school.

While some variation in the curricula exists, the remain

ing four high schools, City High School, Brainerd High

School, Howard High School, and Riverside High School,

each offer a similar general high school curriculum. At

the time when a dual school system was operated by the

School Board, City High School and Brainerd High School

were operated as white schools and Howard High School

and Riverside High School were operated as black schools.

At that time the black high schools were zoned, but the

white high schools were not. When the dual school system

was abolished by order of the Court in 1962, the defendants

proposed and the Court approved a freedom of choice plan

with regard to the high schools. The plan accomplished

some desegregation of the former white high schools, with

City having 141 black students out of an enrollment of 1435

and Brainerd having 184 black students out of an enroll

ment of 1344 during the 1970-71 school year. However,

both Howard, with an enrollment of 1313, and Riverside,

with an enrollment of 1057, remained all black. The free

dom of choice plan “having failed to undo segregation

* * * freedom of choice must be held unacceptable.” Green

v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U S.

430, 88 S.Ct. 1689, 20 L.Ed.2d 716 (1968).

40