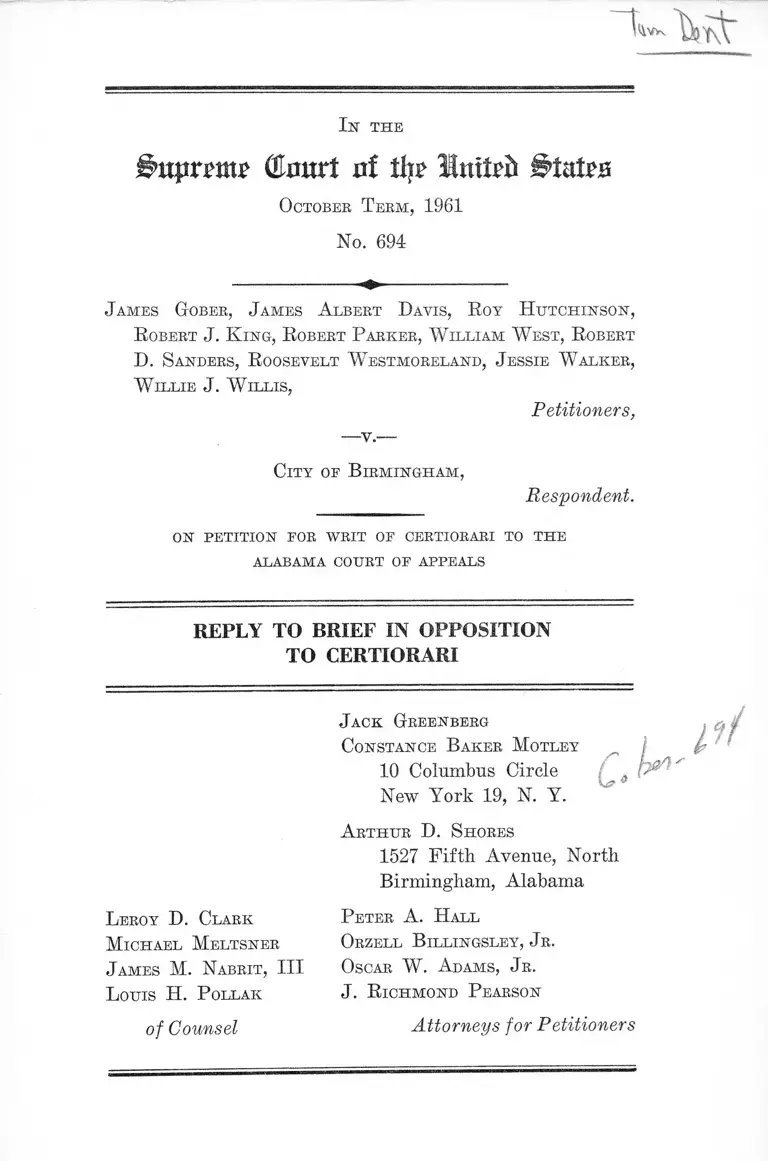

Gober v. City of Birmingham Reply to Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

February 23, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gober v. City of Birmingham Reply to Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1962. cc7d3a83-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8aae0cab-4417-4756-8bcd-c6535d395305/gober-v-city-of-birmingham-reply-to-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

1 st t h e

^nprrnt ©curt ni lit? United

October T erm, 1961

No. 694

J ames Gober, J ames Albert Davis, R oy H utchinson,

R obert J . K ing, R obert P arker, W illiam W est, R obert

D. Sanders, R oosevelt W estmoreland, J essie W alker,

W illie J . W illis,

Petitioners,

—v..

City of B irmingham,

Respondent.

on petition for writ of certiorari to the

ALABAMA COURT OF APPEALS

REPLY TO BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

TO CERTIORARI

L eroy D. Clark

Michael Meltsner

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Louis H. P ollak

of Counsel

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

A rthur D. Shores

1527 Fifth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama

P eter A. H all

Orzell B illingsley, J r.

Oscar W. Adams, J r .

J . R ichmond P earson

Attorneys for Petitioners

I n the

j ^ u p r p m p O X m trt o f tly ? H t t i te i* Butts

October T erm, 1961

No. 694

J ames Gober, J ames Albert Davis, R oy H utchinson,

R obert J . K ing, Robert P arker, W illiam W est, Robert

D. Sanders, R oosevelt W estmoreland, J essie Walker,

W illie J . W illis,

Petitioners,

■—v.-

City of B irmingham,

Respondent.

on petition for writ of certiorari to the

ALABAMA COURT OF APPEALS

PETITIONERS’ REPLY TO BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

TO CERTIORARI

Petitioners have received respondent’s Brief in Opposi

tion to the Petition for Certiorari filed in this case and

hereby reply pursuant to Rule 24(4) of the Rules of this

Court.

I.

A dequacy o f service.

Respondent claims (Br. of Respondent, 3, 9, 10) that

this Court lacks jurisdiction to entertain the Petition be

cause the Petition and Notice of Piling* of the Petition were

served upon MacDonald Gallion, Attorney General of the

2

State of Alabama, and James M. Breckenridge, rather than

Watts E. Davis and William L. Walker. Messrs. Walker

and Davis are Assistant City Attorneys of Birmingham;

Mr. Breckenridge, upon whom service was made, is their

superior, the City Attorney, as is evidenced by copy of

the letter accompanying Respondent’s Brief in Opposition,

reproduced, infra, p. la. Petitioners submit, therefore,

that this objection is without merit, see infra, p. la.

II.

Mode of raising constitutional questions.

Respondent implies that petitioners did not properly

raise constitutional objections in the courts below and

that petitioners’ constitutional objections were not passed

upon by the Alabama Courts.

Specifically, respondent argues that Birmingham’s segre

gation in eating facilities ordinance was not pleaded in

the trial court and does not appear in the records and that,

therefore, this Court should not consider it now. The

theory of judicial notice is, however, that regarding

propositions involved in the pleadings, or relevant thereto,

proof by evidence may be dispensed with. 9 Wigmore,

§2565, p. 531. As it is beyond question that the Courts of

Alabama are required to judicially note ordinances of the

City of Birmington, see Br. of Petitioners, 7, n. 4,1 the

only possible objection which can be made is that the

1 Title 7, Code of Alabama, 1940, Section 429(1) (Approved

June 18, 1943) states:

“ J u d ic ia l N o tic e op t h e O r d in a n c e s o p Ce r t a in C it ie s .— All

courts in or of the State of Alabama shall take judicial notice

of all the ordinances, laws and bylaws of cities of the State of

Alabama which may now or hereafter have a population of

200,000 or more people according to the last or any succeeding

federal census.”

3

ordinance is not relevant to questions raised by the plead

ings. Petitioners, however, clearly raised the contention

that they were arrested, prosecuted and convicted because

of state enforcement of segregation (e.g. Gober, 5-7, 9-11).

Moreover, these contentions were rejected by the Alabama

Courts (e.g. Gober, 8, 9, 11, 62, 63, 64). Finally, petitioners

attempted to interrogate concerning the ordinance (Br.

of Petitioners, 6, 7; Gober, 22-24; Davis, 23-25), but the

evidence was excluded (Gober, 24; Davis, 25).

Respondent argues that no Motion to Exclude the Evi

dence is shown by the record in the case of Roosevelt West

moreland. It is true that no Motion to Exclude is in the

record of the Westmoreland Case, but it is clear from

the Westmoreland record that such a motion was made

and denied by the trial court. The judgment entry in

Westmoreland states that (Westmoreland, 5):

“ . . . and the defendant files motion to exclude the

evidence, and said motion being considered by the

Court, it is ordered and adjudged by the Court that

said motion be and the same is hereby overruled, to

which action of the Court in overruling said motion,

the defendant hereby duly and legally excepts.”

Moreover, the Motion for New Trial in the Westmoreland

Case alleges that the Court refused to grant the Motion to

Exclude (Westmoreland, 8) and the Assignments of Error,

Assignment 3 alleges error in refusing to grant the Motion

to Exclude (Westmoreland, 32). Finally, the trial court

ruled that, by stipulation, the motions in all the cases

would be identical (Hutchinson, 33).

Respondent argues that the Motions to Exclude the Evi

dence did not contain a prayer for relief. This objection

has no merit. The purpose of these motions is clear on their

4

face, and the Alabama Courts raised no question as to their

form.

Respondent argues that the Motions to Strike and the

demurrers did not specifically raise the question of the

need for some identification of authority to ask Peti

tioners to leave the luncheon areas. This issue was, how

ever, raised properly in the Motions to Exclude and the

Motions for New Trial (e.g., Gober, 5-7) and was decided

adversely to petitioners, on the merits, by the Alabama

Courts (e.g., Gober, 8, 62, 63).

It is clear from the face of the records of these cases

that petitioners raised constitutional questions at every

opportunity in both the trial and appellate courts and

that these questions were considered by the Alabama Courts

and rejected on their merits. The Alabama Court of Ap

peals stated:

Counsel has argued among other matters, various

phases of constitutional law, particularly as affected

by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Federal Constitu

tion, such as freedom of speech, in regard to which

counsel state: “What has become known as a ‘sit-in’

is a different, but well understood symbol, meaningful

method of communication.” Counsel has also referred

to cases pertaining to restrictive covenants. We con

sider such principles entirely inapplicable to the pres

ent case. (Emphasis added.) (Br. of Petitioners, 8a.)

5

T he im portance o f the issue: reasons why these cases

should be heard here prior to d isposition o f other sit-in

litigation .

Counting the ten convictions embraced by the instant

certiorari petition, there are now pending before this Court,

eleven separate certiorari petitions and jurisdictional state

ments dealing with state court criminal convictions growing

out of the “sit-in” movement.2

It seems almost beyond dispute that each of these con

victions poses constitutional issues of major dimension.

Cf. Garner v. Louisiana, 7 L. ed. 2d 207. And their humble

facts only serve to highlight the importance of the issues

posed. Cf. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356; Thompson

v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199.

But this concentration of cases poses a real problem of

judicial administration. These multiple convictions merit

careful review in the light of relevant constitutional prinei-

2 Brews v. State (Jurisdictional Statement filed 29 U. S. L. Week

3286, T3o7~SlhrT960 term ; renumbered No. 71, 1961 te rm ); WiU—JVVcs

liams v. North Carolina (Petition for Cert, filed 29 U. S. L. Week

33l9, No. OlbyiOOTTTefm; renumbered No. 82, 1961 te rm ); A v e n t .

v. North Carolina (petition for eert. filed 29 U. S. L. Week 1)336^

No. 943, 195IFEerm; renumbered No. 85, 1961 te rm ); Fox v. North »

Carolina (petition for cert, filed Id. No. 944, 1960 term ; renum

bered No. 86, 1961 term ). Randolph v. Commonwealth of Virginia,.. \

(petition for cert, filed 30 U) S.:tTW BBk^0l3?(T^o7^8jTir6rferm) ;

Commonwealth of Virginia (petition for cert, filed 30

tJ. S7LTWreel~31‘28^7^Tr^?6)‘W9fiTTerm) ; Lombard v. Louisiana^-~^'V<~>)

(petition for cert, filed 30 U. S. L. Week 3234, N(57ir387^^81~tSnH(r;

, Gober. v. City of Birmingham (petition for cert, filed 30 U. S. L.

Week 3250,'""No. 694, 1961 term) ; Thompson v. Commonwealth of _____

c y Virginia* (petition for cert, filed 30 l5. S. TrWTEElr'3234yN67~B55,

1961 term) ; P eterson v. City of Greenville (petition for cert, filed A

30 U. S. L. Week 3274, No. "7HTT9FrWerm). Cf. also S huttles-

worth and Billups v. City of Birmingham (petition for cert, filed

3TTTJTS. L.'WeeF32'58, N o77?irT 99rtt!rm ).x

III.

6

pies. And yet it may be, in view of this Court’s manifold

responsibilities in so many realms of public adjudication,

that detailed sifting of the scores of somewhat varying

factual situations underlying these eleven pending ap

plications for review cannot be forthcoming immediately.

Institutional limitations counsel recognition that this Court

may feel compelled to select for initial adjudication from

among the pending eleven applications the one or more

whose facts may best illuminate constitutional judgments

of widespread application and implication. Just as “wise

adjudication has its own time for ripeness”, Maryland v.

Baltimore Radio Store, Inc., 338 U. S. 912, 918, so too it

may flower best when rooted deep in rich factual soil.

Viewed in this light, the instant petition for certiorari

presents cases which seem peculiarly apt prototypes of

the entire corpus of “sit-in” litigation. Another case which

presents issues in almost the same way as the instant one,

and to which much of what is said here applies, is Peterson

v. City of Greenville, No. 750, October Term, 1961. In the

cases represented by this certiorari petition, (1) there was

a municipal ordinance requiring restaurant segregation;

(2) at least one of the proprietors demonstrably shaped his

business practices to conform to the segregation ordinance

(although inquiry into the general impact of the ordinance

was foreclosed by judicial rulings below); (3) in each case

the proprietor welcomed Negro patronage in the part of

his establishment not covered by the ordinance; (4) in none

of the cases was a defendant ordered from the store by

the proprietor or his agent; (5) in none of the cases were

the police summoned by the proprietor or his agent; and

(6) in each of the cases the defendant was arrested for

and convicted of trespass notwithstanding the non-asser

tion by the proprietor of whatever theoretical claims he

may have had to establish a policy of excluding Negroes

(a) from his premises as a whole or (b) from his restaurant

7

facilities (assuming there had been no segregation ordi

nance precluding any such discretionary business judgment

on the proprietor’s part).

In short, the salient facts summarized above illustrate

with compelling specificity many separately identifiable

(albeit integrally connected) aspects of state action enforc

ing racial segregation. Thus, the cases represented in this

certiorari petition seem particularly apt vehicles for fur

ther judicial exploration of the problems to which this

Court first addressed itself in Garner v. Louisiana, supra.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, fo r the foregoing reasons, i t is respectfully

subm itted tha t the petition for w rit of certio rari should be

granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Arthur D. Shores

1527 Fifth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama

P eter A. H all

O r z e l l B i l l i n g s l e y , J r.

Oscar W. Adams, J r.

J. R ichmond P earson

Attorneys for Petitioners

Leroy D. Clark

Michael Meltsner

J ames M. Nabrit, III

L ouis H. P ollak

of Counsel

8

(See opposite) ESP3

la

JOHN M. BRECKEN RID OE

C ITY A TTO R N EY

ASSISTANT C IT Y A TTO R N EY S

E A R L MCBEE

WATTS E . DAVIS

WM. A . THOMPSON

JAM ES G .ADAMS,

W M .C .W A LK E R

THOMAS J .H A Y D E N

III

Mr. Ja c k G reenberg

10 Columbus C i r c le

New York 19, New York

R e: James G ober, e t a l

v s , CITY OP BIRMINGHAM

D ear Mr. G reen b e rg :

E n c lo sed p le a s e f in d copy o f B r ie f f i l e d on b e h a lf

01 R esponden t to P e t i t i o n f o r W rit o f C e r t i o r a r i .

W atts E. D avis

A s s i s ta n t C ity A tto rn e y

WED:ng

E n e l.

AIR MAIL

- y :

*