Correspondence from Martin to Hershkoff Re: Summaries and Reviews of Articles by Jencks

Working File

July 17, 1990

13 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Correspondence from Martin to Hershkoff Re: Summaries and Reviews of Articles by Jencks, 1990. 19ad34b9-a346-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8b041ce2-d1b2-4d4e-87fb-a8e67498727d/correspondence-from-martin-to-hershkoff-re-summaries-and-reviews-of-articles-by-jencks. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

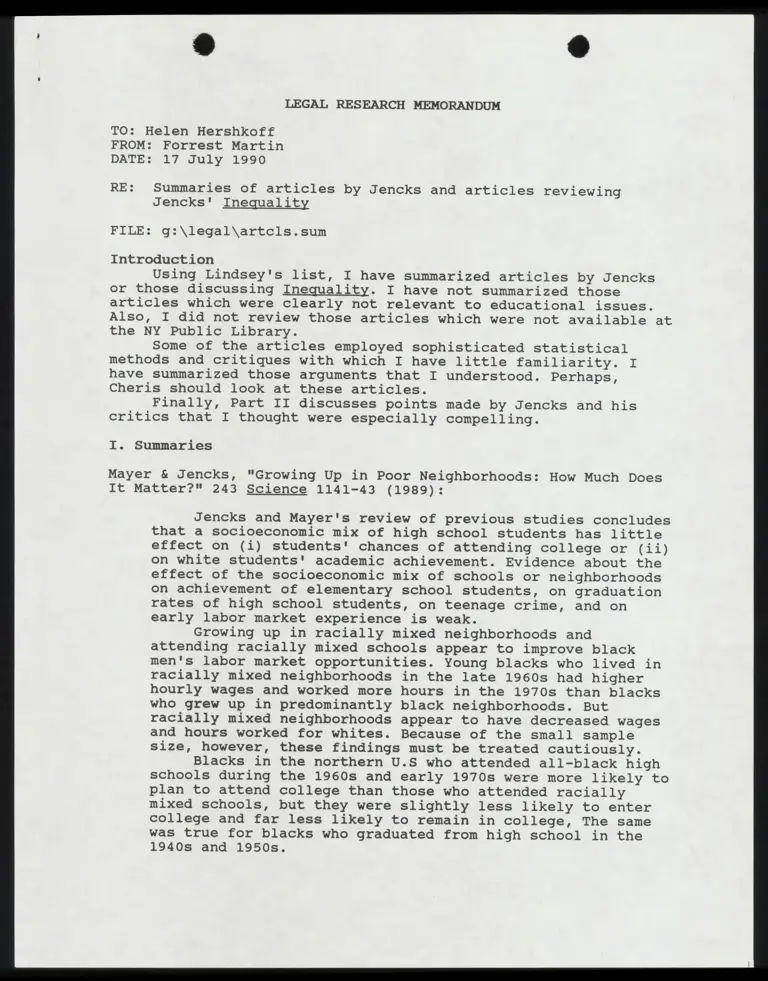

LEGAL RESEARCH MEMORANDUM

TO: Helen Hershkoff

FROM: Forrest Martin

DATE: 17 July 1990

RE: Summaries of articles by Jencks and articles reviewing

Jencks' Inequality

FILE: g:\legal\artcls.sum

Introduction

Using Lindsey's list, I have summarized articles by Jencks

or those discussing Inequality. I have not summarized those

articles which were clearly not relevant to educational issues.

Also, I did not review those articles which were not available at

the NY Public Library.

Some of the articles employed sophisticated statistical

methods and critiques with which I have little familiarity. I

have summarized those arguments that I understood. Perhaps,

Cheris should look at these articles.

Finally, Part II discusses points made by Jencks and his

critics that I thought were especially compelling.

I. Summaries

Mayer & Jencks, "Growing Up in Poor Neighborhoods: How Much Does

It Matter?" 243 Science 1141-43 (1989):

Jencks and Mayer's review of previous studies concludes

that a socioeconomic mix of high school students has little

effect on (i) students' chances of attending college or {ii)

on white students' academic achievement. Evidence about the

effect of the socioeconomic mix of schools or neighborhoods

on achievement of elementary school students, on graduation

rates of high school students, on teenage crime, and on

early labor market experience is weak.

Growing up in racially mixed neighborhoods and

attending racially mixed schools appear to improve black

men's labor market opportunities. Young blacks who lived in

racially mixed neighborhoods in the late 1960s had higher

hourly wages and worked more hours in the 1970s than blacks

who grew up in predominantly black neighborhoods. But

racially mixed neighborhoods appear to have decreased wages

and hours worked for whites. Because of the small sample

size, however, these findings must be treated cautiously.

Blacks in the northern U.S who attended all-black high

schools during the 1960s and early 1970s were more likely to

plan to attend college than those who attended racially

mixed schools, but they were slightly less likely to enter

college and far less likely to remain in college, The same

was true for blacks who graduated from high school in the

1940s and 1950s.

Blacks who attended racially mixed schools in the

Hartford suburbs in the late 1960s were more than twice as

likely as similar blacks who attended predominantly black

inner-city Hartford schools to work in white-collar

occupations in 1982. (I have given this study's citation to

Adam Cohen.)

Jencks & Brown, "Research Note: The Effects of Desegregation on

Student Achievement: Some New Evidence from the Equality of

Educational Opportunity Survey," 48 Sociology of Education 126-40

(Winter 1975):

Based on the Equality of Educational Opportunity Survey

(EEOS) of 1966, Jencks concludes that both black and white

elementary school children improved their test scores when

the racial mix of schools ranged from 51-75% white. Black

students' performance slightly declined if they were in 76-

100% white schools. Black student test performance stayed

constant when the mix was 0-50%. Racial composition of high

schools had no appreciable effect on test performance.

Symposium on Jencks' Inequality, 43 Harvard Educational Review

51-164 (Feb. 1973):

Jackson, "After Apple-Picking," at 51-60:

Jackson criticizes Jencks for seeing schools

merely as factories. Jencks limits the social function

of education as an investment in securing greater

earnings in the future ("human capital" perspective).

However, Jackson's criticism is unfair. Jencks

does recognize that education has other social

functions. Jencks wishes only to refute the commonly

held belief that education is a good investment for

reaping economic benefits in the future.

Rivlin, "Forensic Social Science," at 61-75:

Rivlin's is concerned about the possible political

fallout from Inequality. Rivlin points out that Jencks!’

arguments can be used to undermine educational reform

and compensatory education programs. Inequality will

probably weaken the cause for better schools for

everyone, especially the poor, which the authors

support.

She also attacks Jencks' use of "luck" as a device

in explaining why some students eventually do well

financially and others do not. This can be explained,

however, by Jencks' attempt to explain individual (vs.

group) differences.

Edmonds, et al., "A Black Response to Christopher Jencks's

Inequality and Certain Other Issues," at 76-91:

Edmonds et al. argue that Jencks falsely assumes

that compensatory education programs were truly

compensatory and well executed. Therefore, the failure

of these programs should not entail that truly

compensatory educational programs would not work.

Inequality also fails to consider certain intangible

factors (e.g., internal life of the school, student-

teacher relationship) because these factors cannot be

measured with the tools Jencks employs. Related to this

is that relationships may not be linear. Jencks relies

upon path analysis for his method. Also, Jencks uses

achievement tests as a measure of a pupil's success

although he recognizes that these tests are too narrow

a measure.

Edmonds et al. also fault Jencks' extension of his

conclusions to blacks when his analysis intentionally

eliminated data on blacks. This criticism is not quite

fair. Jencks is interested in explaining individual

variation--not group variation. Therefore, a homogenous

survey group (in this case, native born white nonfarm

men) is appropriate because it eliminates many

extraneous variables. They also unfairly fault Jencks

for his use of genetic studies. They claim that Jencks

implies a genetic basis for the black deficit in IQ.

This is patently false: Jencks states that difference

in IQ genotypes is conceivable.

Finally, Edmonds et al. point out the significance

of cultural differences among students in discussions

of equality and the efficaciousness of education.

Jencks 1s preoccupied with income as the vehicle and

measure of social equality. For different ethnic

communities, equality may be defined in terms other

than income. Also, "objective" measures of cognitive

skills rests on assumptions that may not be valid for

culturally different children. Current sociolinguistic

data suggest that poor children, particularly black

ones, have developed a different language by the time

they enter school. Many such children speak a well-

ordered, highly structured, but different, dialect from

standard English.

Michelson, "The Further Responsibility of Intellectuals," at

92-105:

Michelson also attacks Jencks' limited "human

capital" perspective. He shares Jencks' commitment to

socialism as the answer, but thinks that such a

conclusion from the evidence presented in Inequality is

a non sequitur. There is no substantial discussion on

the merits of socialism; rather, the book is devoted to

demonstrating the inefficacy of education in acquiring

greater future income. Jencks in his response, below,

agrees that his discussion on income redistribution is

inadequate.

* *

Thurow, "Proving the Absence of Positive Associations," at

106-112:

Thurow discusses Jencks' use of luck for

explaining individual income variation. Thurow

concludes, correctly I believe, that Inequality still

allows attacks on group income differentials by

education; it does not allow attacks on individual

income differentials by education. Thurow adds that

Jencks is right to argue that education is an end in

its own right. The only difficulty is that the American

public has been sold on education as a means to other

social and economic ends. Thurow also attacks

Inequality's reliance upon path analysis.

Clark, "Social Policy, Power, and Social Science Research,"

at 113-121:

Clark picks up Rivlin's theme of the potential bad

political consequences of Inequality. Clark claims that

Jencks has only given ammunition to those opposed to

desegregation, decentralization of schools, and the

equalization of expenditures for schools.

He also states that the evidence presented in

Inequality is countered by general observation, folk

knowledge, insight, and our national history. Previous

groups of European immigrants handicapped by the

burdens of language and cultural differences used the

public schools as the chief instrument for their own

economic and social mobility.

Duncan, "Comments on Inequality," at 122-28:

Duncan does not dispute the findings and conclusions of

Inequality; she merely makes some comments on Jencks'

use of the role of luck in explaining the evidence in

Inequality, his focus on explaining inequality between

individuals rather than groups, the role of opportunity

in explaining inequality, earning power, and the social

function of schools.

Jencks, "Inequality in Retrospect," at 138-64:

Jencks responds to the above criticisms. I have

incorporated Jencks responses in the above summaries.

"Symposium Review: Inequality, Jencks et al," 46 Sociology of

Education 427-70 (Fall 1973)

Miller, "On the Uses, Misuses and Abuses of Jencks'

Inequality," at 427-32:

% *

Miller makes three good points:

1. Jencks' contention that schools and

specific programs have little effect on IQ

scores is based on little data. The data on

compensatory education comes from a period

before there was much research on the topic.

(429)

2. Miller agrees with Jencks that students

should not be regarded as human capital and

education as investment. Rather, education

should be regarded as amenities or utilities:

things which make life easier or better for

its recipients. Education should not be

considered in instrumental terms. (431)

3. Jencks conclusion that education cannot

effect certain socioeconomic benefits is

probably because he fails to focus on

statistically significant differences among a

variety of variables. Rather, in his attempt

to explain total variance, he looks for one

key variable and finds nothing. A variety of

variables acting together would probably

explain the total variance. (428)

Taylor, "Playing the Dozens with Path Analysis:

Methodological Pitfalls in Jencks et al., Inequality," at

433-50:

This article is statistically abstruse; I

cannot understand most of it. However, there are

some significant points which I was able to glean

from it. Jencks employs path analysis, and every

path analysis which he employs leaves out blacks

altogether because the study's pool employs only

native white nonfarm males who took an armed

forces IQ test. (439) Jencks admits that curently-

used IQ tests carry a heavy culture-bias, but he

nonetheless uses these tests in his own analysis

without employing newer test especially designed

for minorities. (447) Finally, Taylor faults

Jencks for his failure to consider institutional

racism, the omission of which in a book

"presumably analyzing 'inequality' in society is

an omission almost beyond conception." (448)

Jencks, "The Methodology of Inequality," at 451-70.

Again, the statistical discussion is impossible

for me to follow. As to Taylor's criticisms noted

above, Jencks notes that since blacks constitute

only 11% of the population, their omission is not

a serious distortion of his conclusions. Also,

Jencks does devote certain chapters of Inequality

to racism as a determinate of economic success.

+ »

Jencks & Brown, "Effects of High Schools on their Students," 45

Harvard Educational Review 273-324 (Aug. 1975):

Again, the statistical discussion is impossible for me

to follow. Jencks turns his attention to the quality of high

schools and their effects on test scores, eventual

educational attainment, and occupational status. He finds

few relationships and concludes that high schools should

concentrate on eliminating intramural inequities.

Most importantly for our purposes, he makes clear that

his study says nothing about the effects of racial

desegregation because he excluded schools with more than 24%

black enrollment.

Jencks, "Whom Must We Treat Equally for Educational Opportunity

to be Equal?" 98 Ethics 518-33 (April 1988):

Article categorizes five common ways of thinking about

educational opportunity: (i) democratic equality, (ii)

moralistic justice, (iii) weak human justice, (iv) strong

human justice, and (v) utilitarianism. Jencks finds that

each prescriptive paradigm taken to its logical conclusion

can conflict with the other. Relative weight of each

principle varies from situation to situation. Presence of

each paradigm in educational context explains why everyone

supports equal educational opportunity in principle.

Jencks, "Affirmative Action for Blacks: Past, Present, and

Future," 28 American Behavioral Scientist 731-60 (July/Aug.

1985) :

Article discusses history and future of affirmative

action for blacks. Article adds nothing new to literature on

affirmative action.

Jencks, "Heredity, Environment, and Public Policy Reconsidered,"

45 American Sociological Review 723-36 (Oct. 1980):

Article not relevant for our purposes.

II. Conclusions

1. If the Sheff defendants decide to use Inequality for

buttressing their arguments against desegregation, they

would face a very serious counterargument: the study is

irrelevant because it eliminated blacks from its data.

2. Inequality attempts to explain individual differences--

not group or racial differences.

3. Thurow, Taylor, and Edmond et al's arguments against

Jencks' use of path analysis is important. The relationships

# Re

between certain variables may not reflect a path analysis

model.

4. Rivlin and Edmonds et al. point out that attacks on

compensatory education made on the basis of the history of

alleged compensatory programs should not be made because

those programs were hardly compensatory.

5. Although Inequality says nothing about the effects of

school desegregation, Jencks' 1975 article in Sociology of

Education does address the beneficial effects of

desegregation on elementary school student test performance.

U.S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 58 L Ed 2d

(439 US 1380)

BUSTOP, INC., Applicant,

v

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF LOS ANGELES et al.

439 US 1380, 58 L Ed 2d 88, 99 S Ct 40

[No. A-249)

September 8, 1978.

SUMMARY

After the Supreme Court of California had vacated a supersedeas or stay

issued by the Court of Appeal of California, staying an order of the Superior

Court of Los Angeles County which prescribed a desegregation plan for the

schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District, an organization repre-

senting students who would be bused under the plan applied to an individ-

ual Justice of the United States Supreme Court, as Circuit Justice, for a

stay of the California Supreme Court's order, pending the filing of a petition

for certiorari or an appeal.

Rennquisr, J., as Circuit Justice, denied the application for a stay for the

reasons stated in headnote 1 below.

Briefs of Counsel, p 975, infra.

HEADNOTES

Classified to U. S. Supreme Court Digest, Lawyers’ Edition

Appeal and Error § 913 — stay order Justice, will deny an application for a

— individual Justice stay, pending the filing of a petition for

la, 1b. An individual Justice of the certiorari or an appeal, of an order of a

United States Supreme Court, as Circuit state's highest court which had vacated

ANNOTATION REFERENCES

Supreme Court's views as to what constitutes appropriate relief under provisions of Federal

Constitution in school desegregation cases. 53 L, Ed 2d 1228.

Considerations affecting grant or vacation of stay or injunction by individual Justice of

Supreme Court. 24 L Ed 2d 925.

Racial discrimination in education. 24 L Ed 2d 765.

Relief against school board's “busing” plan to promote desegregation. 50 ALR3d 1089.

88

E

E

—

rr

fi

ca

—

BUSTOP, INC. v BOARD OF EDUCATION

439 US 1380, 58 L Ed 2d 88, 99 S Ct 40

an intermediate state appellate court’s

supersedeas or stay of a state trial

court's school desegregation order that

apparently required the reassignment of

over 60,000 students in a school district

and the busing of some students involv-

ing a one and one half hour ride to

school—the applicant urging on behalf of

students who would be transported pur-

suant to the desegregation order that the

order of the state's highest court was

contrary to recent school desegregation

decisions of the United States Supreme

Court, and that a state could not use the

doctrine of independent state grounds to

ignore the federal rights of its citizens to

be free from racial quotas and extensive

pupil transportation which destroy fun-

damental liberty and privacy rights—

where (1) the state's highest court prem-

ised its decision not on the equal protec-

tion clause of the Fourteenth Amend-

ment, but on the state constitution,

which it had construed to require less of

a showing on the part of plaintiffs who

seek court-ordered busing than the

United States Supreme Court had re-

quired of plaintiffs who sought similar

relief under the Federal Constitution, (2)

thus, it was not probable that four Jus-

tices of the Supreme Court would vote to

grant certiorari, (3) even if the applicant

was viewed as having a stronger federal

claim on the merits, the fact that the

schools were scheduled to open in four

days was an equitable consideration

counselling against once more upsetting

the expectations of the parties in the

case, and (4) the school board raised no

objection to the plan and the state's

highest court had apparently placed its

imprimatur on it, the complaints of the

parents and children being complaints

about state law, and it being in the

forums of the state that such questions

must be resolved. [Per Rehnquist, J., as

Circuit Justice.)

Civil Rights § 8 — school desegrega-

tion — busing

2. The only authority that a federal

court has to order desegregation or bus-

ing in a local school district arises from

the Federal Constitution, but state

courts are free to interpret the state

constitution to impose more stringent

restrictions on the operation of a local

school board. [Per Rehnquist, J., as Cir-

cuit Justice.)

OPINION

[439 US 1380)

Mr. Justice Rehnquist, Circuit

Justice.

Applicant Bustop, Inc., supported

by the Attorney General of Califor-

nia, requests that I stay, pending the

filing of a petition for certiorari or

an appeal, the order of the Supreme

Court of California. That order va-

cated a supersedeas or stay issued by

the California Court of Appeal,

which had in turn stayed the en-

forcement of a school desegregation

order issued by the Superior Court

of Los Angeles County.

The desegregation plan challenged

by applicant apparently requires the

reassignment of over 60,000 stu-

dents. In terms of numbers jt is one

of the most extensive desegregation

plans in the United States. The es-

sential logic of the plan is to pair

elementary and junior high schools

having a 70% or greater Anglo ma-

jority with schools having more than

a 70% minority enrollment. Paired

schools are often miles apart, and

the result is extensive transporta-

tion of students. Applicant contends

that round-trip distances are gener-

ally in the range of 36 to 66 miles.

Apparently some students must

(439 US 1381]

catch buses before 7 a. m. and have

a 1%-hour ride to school. The objec-

tive of the plan is to insure that all

schools in the Los Angeles Unified

School District have Anglo and mi-

nority percentages between 70% and

30%.

89

Applicant urges on behalf of stu-

dents who will be transported pursu-

ant to the order of the Superior

Court that the order of the Supreme

Court of California is at odds with

this Court’s recent school desegrega-

tion decisions in Dayton Board of

Education v Brinkman, 433 US 4086,

53 L Ed 2d 851, 97 S Ct 2766 (1977),

Brennan v Armstrong, 433 US 672,

53 L Ed 2d 1044, 97 S Ct 2907 (1977),

and School District of Omaha v

United States, 433 US 667, 53 L Ed

2d 1039, 97 S Ct 2905 (1977). The

California Court of Appeal, which

stayed the order of the Superior

Court, observed that the doctrine of

these cases “reflects a refinement of

earlier case law which should not

and cannot be ignored.” The major-

ity of the Supreme Court of Califor-

nia, however, in a special session

held Wednesday, September 6, va-

cated the supersedeas or stay issued

by the Court of Appeal and denied

applicant’s request for a stay of the

order of the Superior Court.

[1a] Were the decision of the Su-

preme Court of California premised

on the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution, I would

be inclined to agree with the conclu-

sion of the California Court of Ap-

peal that the remedial order entered

by the Superior Court in response to

earlier decisions of the Supreme

Court of California was inconsistent

with our decisions cited above. But

the earlier opinion of the Supreme

Court of California in this case,

Crawford v Board of Education, 17

Cal 3d 280, 551 P2d 28 (1976), and

Jackson v Pasadena City School Dis-

trict, 59 Cal 2d 876, 382 P2d 878

(1963), construe the California State

Constitution to require less of a

showing on the part of plaintiffs who

seek court-ordered busing than this

90

U.S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS

58 L Ed 2d

Court has required of plaintiffs who

seek similar relief under the United

States Constitution. Although the

California Court of Appeal is of the

view that this Court’s cases would

require a different result

[439 US 1382)

from that

reached by the Supreme Court of

California in Crawford, and although

the order of the Supreme Court of

California issued Wednesday was not

accompanied by a written opinion,

in the short time available to me to

decide this matter I think the fairest

construction is that the Supreme

Court of California continues to be

of the view which it announced in

Jackson and adhered to in Crawford.

Quite apart from any issues as to

finality, it is this conclusion which

effectively disposes of applicant’s

suggestion that four Justices of this

Court would vote to grant certiorari

to review the judgment of the Su-

preme Court of California, which in

effect overturned the order of the

Court of Appeal and reinstated the

order of the Superior Court.

[2] Applicant relies upon my ac-

tion staying the judgment and order

of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit in Columbus Board of Educa-

tion v Penick, ante, p 1348, 58 L Ed

2d 55, 99 S Ct 24 but that case is, of

course, different in that the only

authority that a federal court has to

order desegregation or busing in a

local school district arises from the

United States Constitution. But the

same is not true of state courts. So

far as this Court is concerned, they

are free to interpret the Constitution

of the State to impose more strin-

gent restrictions on the operation of

a local school board.

Applicant phrases its contention

in this language:

“Unlike desegregation cases

coming to this Court through the

lower federal courts, of which

there must be hundreds, if not

thousands, here the issue is novel.

The issue: May California in an

attempt to racially balance schools

use its doctrine of independent

state grounds to ignore the federal

rights of its citizens to be free

from racial quotas and to be free

from extensive pupil transporta-

tion that destroys fundamental

rights of liberty and privacy.” Ap-

plication for Stay 16.11.

But this is not the traditional argu-

ment of a local school board contend-

ing that it has been required by

court order to implement

[439 US 1383]

a pupil assignment plan

which was not justified by the Four-

teenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution. The argument is

indeed novel, and suggests that each

citizen of a State who is either a

parent or a schoolchild has a “fed-

eral right” to be “free from racial

quotas and to be free from extensive

pupil transportation that destroys

fundamental rights of liberty and

privacy.” While I have the gravest

BUSTOP, INC. v BOARD OF EDUCATION

439 US 1380, 58 L Ed 2d 88, 99 S Ct 40

doubts that the Supreme Court of

California was required by the

United States Constitution to take

the action that it has taken in this

case, I have very little doubt that it

was permitted by that Constitution

to take such action.

[1b] Even if I were of the view

that applicant had a stronger federal

claim on the merits, the fact that

the Los Angeles schools are sched-

uled to open on Tuesday, September

12, is an equitable consideration

which counsels against once more

upsetting the expectations of the

parties in this case. The Los Angeles

Board of Education has been ordered

by the Superior Court of Los Angeles

County to bus an undoubtedly large

number of children to schools other

than those closest to where they

live. The Board, however, raises be-

fore me no objection to the plan, and

the Supreme Court of California has

apparently placed its imprimatur on

it. I conclude that the complaints of

the parents and the children in

question are complaints about Cali-

fornia state law, and it is in the

forums of that State that these ques-

tions must be resolved. The applica-

tion for a stay is accordingly denied.

U.S. SUPREME COURT REPORTS 58 L Ed 2d

[439 US 1384)

BUSTOP, INC., Applicant,

v

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF LOS ANGELES et al.

439 US 1384, 58 L Ed 2d 92, 99 S Ct 44

[No. A-249)

September 9, 1978.

SUMMARY

After Rehnquist, J., as Circuit Justice, had denied an application by an

organization representing certain school students for a stay, pending certio-

rari or an appeal, of an order of the Supreme Court of California (Bustop,

Inc. v Board of Education (1978) 439 US 1380, 58 L. Ed 2d 88, 99 S Ct 40)—

the California Supreme Court having vacated a supersedeas or stay issued

by the Court of Appeal of California, staying an order of the Superior Court

of Los Angeles County which prescribed a desegregation plan for the schools

in the Los Angeles Unified School District—the organization applied to

another individual Justice of the United States Supreme Court for a stay of

the California Supreme Court’s order.

PoweLL, J., as individual Justice, being in accord with the reasons

advanced by the Circuit Justice, also denied the application for a stay.

Briefs of Counsel, p 975, infra.

HEADNOTE

Classified to U. S. Supreme Court Digest, Lawyers’ Edition

Appeal and Error § 913 — stay order States Supreme Court will deny an ap-

— individual Justice plication for a stay, pending the filing of

An individual Justice of the United a petition for certiorari or an appeal, of

ANNOTATION REFERENCES

Supreme Court's views as to what constitutes appropriate relief under provisions of Federal

Constitution in school desegregation cases. 53 L Ed 2d 1228.

Considerations affecting grant or vacation of stay or injunction by individual Justice of

Supreme Court. 24 L Ed 2d 925.

Racial discrimination in education. 24 L Ed 2d 765.

Relief against school board's “busing” plan to promote desegregation. 50 ALR3d 1089.

92

s

e

An

a

a

S

E

g

e

s

BUSTOP, INC. v BOARD OF EDUCATION

439 US 1384, 58 L Ed 2d 92, 99 S Ct 44

an order of a state's highest court which

had vacated an intermediate state appel-

late court's supersedeas or stay of a state

trial court’s school desegregation order

that apparently required the reassign-

ment of over 60,000 students in a school

district and the busing of some students

involving a one and one half hour ride to

school, where the individual Justice was

in accord with the reasons advanced by

another individual Justice of the Su-

preme Court who, as Circuit Justice, had

previously denied the application for a

stay. [Per Powell, J., as individual Jus-

tice.]

OPINION

[439 US 1384)

Mr. Justice Powell.

The application for a stay in this

case, denied by Mr. Justice Rehn-

quist by his in-chambers opinion and

order of September 8, 1978, ante, p

1380, 568 LL Ed 2d 88, has now been

referred to me.

As I am in accord with the rea-

sons advanced by Mr. Justice Rehn-

quist in his opinion, I also deny the

application.