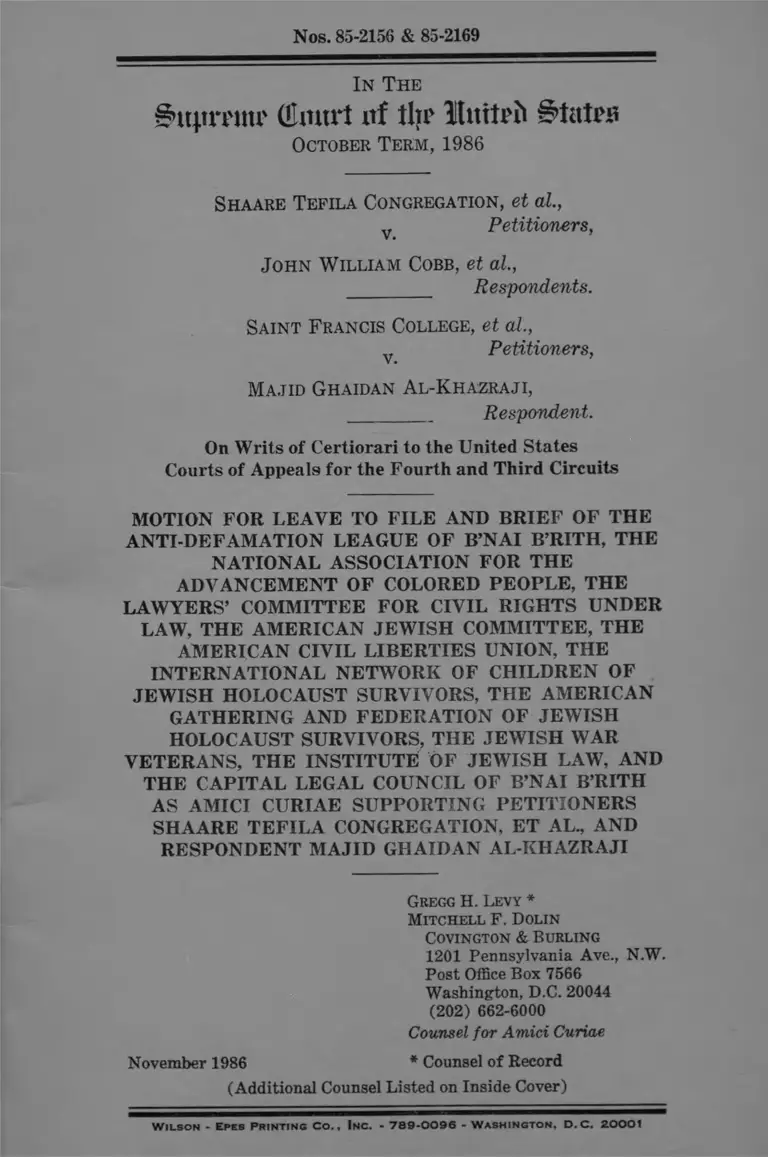

Shaare Tefila Congregation v Cobb Brief of Amici Curiae and Motion to Leave

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1986

36 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shaare Tefila Congregation v Cobb Brief of Amici Curiae and Motion to Leave, 1986. e14cd4da-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8b1a73d9-7a31-46e4-89c8-4730462c3098/shaare-tefila-congregation-v-cobb-brief-of-amici-curiae-and-motion-to-leave. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 85-2156 & 85-2169

I n T h e

§«|jmnp QJmtrt itf tin' Stairs

O c to ber T e r m , 1986

S h a a r e T e f il a C o n g r e g a t io n , et al,

v Petitioners,

J o h n W il l ia m C o b b , et al.,

Respondents.

S a i n t F r a n c is C o l l e g e , et al.,

v Petitioners,

M a j id G h a id a n A l - K h a z r a j i ,

______________Respondent.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United States

Courts of Appeals for the Fourth and Third Circuits

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AND BRIEF OF THE

ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE OF B’NAI B’RITH, THE

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, THE

LAW YERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER

LAW, THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE, THE

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, THE

INTERNATIONAL NETWORK OF CHILDREN OF

JEWISH HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS, THE AMERICAN

GATHERING AND FEDERATION OF JEWISH

HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS, THE JEWISH WAR

VETERANS, THE INSTITUTE OF JEWISH LAW, AND

THE CAPITAL LEGAL COUNCIL OF B’NAI B’RITH

AS AMICI CURIAE SUPPORTING PETITIONERS

SHAARE TEFILA CONGREGATION, ET AL., AND

RESPONDENT MAJID GHAIDAN AL-KHAZRAJI

Gregg H. Levy *

Mitchell F. Dolin

Covington & Burling

1201 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W.

Post Office Box 7566

Washington, D.C. 20044

(202) 662-6000

Counsel for Amici Curiae

November 1986 * Counsel of Record

(Additional Counsel Listed on Inside Cover)

W il s o n - Ep e s P r in t in g C o . , In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h in g t o n , D .C . 2 0 0 0 1

Of Counsel:

Michael Schultz

Meyer Eisenberg

David Brody

Edward N. Leavy

Steven M. Freeman

Jill L. Kahn

A nti-Defamation League

of B ’nai B ’rith

823 United Nations Plaza

New York, New York 10017

(212) 490-2525

and

1640 Rhode Island Ave., N.W .

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 857-6660

Menachem Z. Rosensaft

International Network

of Children of Jewish

Holocaust Survivors

425 Park Avenue

New York, New York 10022

(212) 407-8000

Robert S. R ifkind

Samuel Rabinove

Richard T. Foltin

A merican Jewish Committee

165 East 56th Street

New York, New York 10002

(212) 751-4000

E ileen Kaufman

Institute of

Jewish Law

300 Nassau Road

Huntington, New York 11743

(516) 421-2244

Harold R. Tyler

James Robertson

Norman Redlich

W illiam L. Robinson

Judith A. W inston

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Rachael P ine

A merican Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 944-9800

Joseph A. Morris

Capital Legal Council

of B ’nai B’rith

5500 Friendship Boulevard

Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815

Grover G. Hankins

Joyce H. Knox

National A ssociation

for the Advancement of

Colored People

4805 Mount Hope Drive

Baltimore, Maryland 21215

(301) 358-8900

I n T h e

§npnmu' (fknxrt nf %

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1986

Nos. 85-2156 & 85-2169

S h a a r e T e f il a C o n g r e g a t io n , et al,

Petitioners,

J o h n W il l ia m C o b b , et al.,

_________ Respondents.

Sa i n t F r a n c is C o l l e g e , et al.,

Petitioners,

M a j id G h a i d a n A l -K h a z r a j i ,

_________ Respondent.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United States

Courts of Appeals for the Fourth and Third Circuits

MOTION OF THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE OF

B’NAI B’RITH, THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE,

THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW, THE AMERICAN JEWISH

COMMITTEE, THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION, THE INTERNATIONAL NETWORK OF

CHILDREN OF JEWISH HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS,

THE AMERICAN GATHERING AND FEDERATION OF

JEWISH HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS, THE JEWISH WAR

VETERANS, THE INSTITUTE OF JEWISH LAW, AND

THE CAPITAL LEGAL COUNCIL OF B’NAI B’RITH FOR

LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

(i)

11

The Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, the Na

tional Association for the Advancement of Colored People,

the American Jewish Committee, the American Civil Lib

erties Union, the International Network of Children of

Jewish Holocaust Survivors, the American Gathering and

Federation of Jewish Holocaust Survivors, the Jewish War

Veterans, the Institute of Jewish Law, and the Capital

Legal Council of B’nai B’rith, pursuant to Rule 36.3,

hereby move for leave to file the attached brief amici

curiae supporting the petitioners in Shaare Tefila Con

gregation v. Cobb, No. 85-2156, and the respondent in

Saint Francis College v. Al-Khazraji, No. 85-2169. Con

sent to file this brief has been obtained from counsel for

all parties to No. 85-2169; letters expressing that consent

have been lodged with the Clerk of the Court. With re

spect to No. 85-2156, consent to file the brief has been

obtained from all of the petitioners and from the only

respondent who has entered an appearance in this Court;

letters expressing such consent have been filed with the

Clerk of this Court. Because the amici have been unable

to obtain consent from the remaining respondents in No.

85-2156, most of whom could not be located, this motion

is necessary.

The background and concerns of the amici are fully set

forth in the Interest of Amici Curiae section of the at

tached brief. In sum, the Anti-Defamation League, the

NAACP, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under

Law, the American Jewish Committee, and the American

Civil Liberties Union have sought for several decades to

promote good will and mutual understanding among all

Americans and to combat racial and religious prejudice

in the United States. Over the years, each organization

has appeared frequently before this Court as amicus

curiae to advance constructions of the constitution and

federal civil rights laws that would ensure appropriate

federal remedies for victims of racial, religious, and other

forms of discrimination. The International Network and

the American Gathering are organizations of Jewish

iii

survivors of the Nazi holocaust and their children. The

Jewish War Veterans is comprised of Jewish individuals

who have served in the American armed forces. The In

stitute of Jewish Law is concerned with research and

scholarship in the field of Jewish legal studies. The

Capital Legal Council of B’nai B’rith is comprised of

Jewish members of the bench, bar, and related profes

sions.

The amici believe that this Court should confirm the

rule of law that extends to Arabs, Jews, and other minor

ity and ethnic group members the remedies provided in

section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1981 & 1982. The amici organizations and their mem

bers bring to the issues raised in this case perspectives

and experiences that are broader than and different from

those of the parties. On October 6, 1986, many of these

amici were granted leave to file a brief, and did file a

brief, urging that certiorari be granted in No. 85-2156.

The amici now respectfully seek the Court’s leave to file

the attached brief on the merits.

Respectfully submitted,

Gregg H. Levy *

Mitchell F. Dolin

Covington & Burling

1201 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W.

Post Office Box 7566

Washington, D.C. 20044

(202) 662-6000

Counsel for Amici Curiae

* Counsel of Record

IV

Of Counsel:

Michael Schultz

Meyer E isenberg

David Brody

Edward N. Leavy

Steven M. Freeman

Jill L. Kah n

A nti-Defamation League

of B ’nai B ’rith

823 United Nations Plaza

New York, New York 10017

(212) 490-2525

and

1640 Rhode Island Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.G. 20036

(202) 857-6660

Menachem Z. Rosensaft

International Network

of Children of Jewish

Holocaust Survivors

425 Park Avenue

New York, New York 10022

(212) 407-8000

Robert S. Rifkind

Samuel Rabinove

Richard T. F oltin

A merican Jewish Committee

165 East 56th Street

New York, New York 10002

(212) 751-4000

E ileen Kaufman

Institute of

Jewish Law

300 Nassau Road

Huntington, New York 11743

(516) 421-2244

Harold R. Tyler

James Robertson

Norman Redlich

W illiam L. Robinson

Judith A. W inston

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Rachael P ine

A merican Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 944-9800

Joseph A. Morris

Capital Legal Council

of B ’nai B’rith

5500 Friendship Boulevard

Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815

Grover G. Hankins

Joyce H. Knox

National A ssociation

for the Advancement of

Colored People

4805 Mount Hope Drive

Baltimore, Maryland 21215

(301) 358-8900

November 1986

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether Arabs, Jews, and other minority group mem

bers who do not belong to distinct “non-white races,” but

who are the victims of racially-motivated discrimination,

are entitled to seek relief under section 1 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 & 1982.

(v)

Page

MOTION OF THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE

OF B’NAI B’RITH, ET AL., FOR LEAVE TO FILE

A BRIEF AMICI CU R IAE............................................... i

QUESTION PRESENTED ................................................... v

TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................ vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................................ viii

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ....................................... 2

SUMMARY OF AR GU M ENT............................................. 5

ARGUM ENT.............................................................................. 6

I. The Language and Legislative History of the

Civil Rights Act of 1866 Confirm That the Stat

ute Protects White and Non-White Minority and

Ethnic Group Victims of Racially-Motivated

Discrimination.............................................................. 6

A. The Racial Character of the Discrimination

Rather Than the Racial Status of the Plain

tiff is the Focus of the Statute ........................... 7

B. The Statute Was Intended to be Construed

Broadly and to Protect Minority and Ethnic

Group Members Regardless of Whether They

Belong to Distinct Non-White Races ............ 10

II. Federal Remedies for Racially-Discriminatory

Conduct Should Not be Limited by Narrow and

Arbitrary Definitions of “Race” ............................. 13

III. Section 1981 and 1982 Plaintiffs Should be Per

mitted to Proceed With Their Claims Unless

Their Allegations Are Clearly Inconsistent With

the Possibility That They Were the Victims of

Racial Discrimination ................................................ 20

CONCLUSION .......................................................................... 22

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(vii)

viii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Alizadeh V. Safeway Stores, Inc., 802 F.2d 111 (5th

Cir. 1986) ....................................................................... 21

Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S,

574 (1983).......................................................... 3

Brownw. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).. 3

City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808

(1966) ............................................................................. 8

City of Memphis V. Greene, 451 U.S. 100 (1981).... 10

Delaware State College v. Ricks, 449 U.S, 250

(1980) ............................................................................... 21

Erebia V. Chrysler Plastic Products Corp., 772 F.2d

1250 (6th Cir. 1985), cert, denied, 106 S.Ct. 1197

(1986) ...................................................................... _______ 22

Ex parte Mohriez, 54 F. Supp. 941 (D. Mass.

1944) ................................................................................ 19

Frank V. Mangum, 237 U.S. 309 (1915) ....... ........ . 2

Georgia V. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966) ...................... 8

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943).. 18

In re Hassan, 48 F. Supp, 843 (E.D. Mich. 1942).... 19

In re Mohan Singh, 257 F. 209 (S.D. Cal. 1919).... 20

Jones V. AlfredH. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968).. 3 ,8,

10,14

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co.,

427 U.S. 273 (1976)................................ 3, 6, 7, 8, 9 ,10 ,11

Manzanares V. Safeway Stores, Inc., 593 F.2d 968

(10th Cir. 1979) ........................ ...... ....... ................... u , 22

Mayers v. Ridley, 465 F.2d 630 (D.C. Cir. 1972).... ’ 16

Morrison V. California, 291 U.S. 82 (1934) ........ 13

Near V. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931).................. 18

Ortiz v. Bank of America, 547 F. Supp. 550 (E.D.

Cal. 1982) ............................................................11,15,17, 22

Ramos V. Flagship International, Inc., 612 F. Supp.

148 (E.D.N.Y. 1985)................................................... 22

Runyon V. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976).................. 6

Shelley V. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).......... ........... 3

Sidlivan V. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229

_(1969) ...............................................................................3, 9, 10

Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Ass’n, 410

U.S. 431 (1973)............................................................ 6, 8> 9

IX

Page

United States V. Price, 383 U.S. 787 (1966)........... 10

United States V. Bhagat Singh Thind, 261 U.S. 204

(1923)..........................................................................13,17, 20

Woods-Drake v. Lundy, 667 F.2d 1198 (5th Cir.

1982) ................................................................................ 9

Statutes and Legislative Materials:

Civil Rights Act of 1866

42 U.S.C. § 1981.......................... ............................. passim

42 U.S.C. § 1982..................................... passim

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866)........... 10, 11,12

Miscellaneous:

G. Barton, A Sketch of Semitic Origins (1902)—. 16

J. Barzun, Race: A Study in Superstition (1965).. 17

R. Benedict, Race and Racism (1942)................... . 19

I. Berlin, Against the Current: Essays in the His

tory of Ideas (1980).................................................... 18

Dickey, Falling Out of Love with the Arabs, News

week, Aug. 25, 1986, at 4 4 ........................................ 16

G. Eliot, Daniel Deronda (1876) .................................. 18

T. Gossett, Race: The History of An Idea in

America (1963)..... 15

Greenfield & Kates, Mexican Americans, Racial

Discrimination, and the Civil Rights Act of 1866,

63 Ca l . L. Rev. 662 (1975) ................................12,17, 22

L. Hand, The Spirit of Liberty (3d ed. 1974) ........ 18

B. Lewis, Semites and Anti-Semites (1986)............. 15,16

S. Molnar, Races, Types, and Ethnic Groups

(1975)............................................................................... 17

A. Montagu (ed.), The Concept of Race (1964).... 14,17

A. Montagu, Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The

Fallacy of Race (5th ed. 1974) ............ 18

Newell, Arab Bashing in America, Newsweek,

Jan. 20, 1986, at 2 1 ..................................................... 16

Note, Legal Definition of Race, 3 Race Rel. L. Rep.

571 (1958)...................................................................... 20

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

X

Page

Note, National Origin Discrimination Under Sec

tion 1981, 51 F ordh am L. Re v . 919 (1983)........ 11,22

M. Schappes (ed.), A Documentary History of the

Jews in the United States (3d ed. 1971) ............ 18

N. Webster, An American Dictionary of the Eng

lish Language (C. Goodrich rev. Springfield,

Mass. 1860) .................................................................... 12,18

Webster’s Third New International Dictionary

(1981) ............................................................................. 17, 18

J. Worcester, A Universal and Critical Dictionary

of the English Language (Boston, Mass. 1874).. 16

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

I n T h e

l$itpran? (Emrrt at % lUmtvh

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1986

Nos. 85-2156 & 85-2169

S h a a r e T e f il a C o n g r e g a t io n , et al.,

Petitioners,

J o h n W il l ia m C o b b , et al.,

________ Respondents.

S a i n t F r a n c is C o l l e g e , et al.,

Petitioners,v.

M a j id G h a id a n A l -K h a z r a j i ,

________ Respondent.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United States

Courts of Appeals for the Fourth and Third Circuits

BRIEF OF THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE OF

B’NAI B’RITH, THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE,

THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW, THE AMERICAN JEWISH

COMMITTEE, THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION, THE INTERNATIONAL NETWORK OF

CHILDREN OF JEWISH HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS,

THE AMERICAN GATHERING AND FEDERATION OF

JEWISH HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS, THE JEWISH WAR

VETERANS, THE INSTITUTE OF JEWISH LAW, AND

THE CAPITAL LEGAL COUNCIL OF B’NAI B’RITH AS

AMICI CURIAE SUPPORTING PETITIONERS SHAARE

TEFILA CONGREGATION, ET AL., AND RESPONDENT

MAJID GHAIDAN AL-KHAZRAJI

2

This brief is submitted on behalf of the Anti-Defama

tion League of B’nai B’rith, the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People, the Lawyers’ Com

mittee for Civil Rights Under Law, the American Jewish

Committee, the American Civil Liberties Union, the In

ternational Network of Children of Jewish Holocaust

Survivors, the American Gathering and Federation of

Jewish Holocaust Survivors, the Jewish War Veterans,

the Institute of Jewish Law, and the Capital Legal Coun

cil of B’nai B’rith in support of the petitioners in Shaare

Tefila Congregation v. Cobb, No. 85-2156, and the re

spondent in Saint Francis College v. Al-Khazraji, No.

85-2169. The brief is being filed jointly in the two cases

because they pose similar issues, as recognized by this

Court’s Order of October 6, 1986, setting their oral argu

ments in tandem.

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

B’nai B’rith, which was founded in 1843, is the oldest

civic service organization of Jews in this country. The

Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith was formed in

1913, partially in response to the virulent anti-Semitism

surrounding the Atlanta trial of Leo Frank, see Frank v.

Mangum, 237 U.S. 309, 349-50 (1915) (Holmes &

Hughes, JJ., dissenting). Throughout its history, the

Anti-Defamation League has sought, as its charter pre

scribes, ̂ “ to secure justice and fair treatment to all citi

zens alike and to put an end forever to unjust and unfair

discrimination against and ridicule of any sect or body of

citizens.” The Anti-Defamation League remains vitally

interested in protecting the civil rights of all persons and

in assuring that every individual receives equal treatment

under the law regardless of his or her race, religion, or

ethnic origin.

In support of these objectives, the Anti-Defamation

League has for several decades filed amicus curiae briefs

in this and other courts. These briefs, including several

3

dealing with the statute at issue in this case, have, as

appropriate, urged the unconstitutionality or illegality of

racially-discriminatory laws and practices and the pro

vision of appropriate federal remedies to victims of such

discrimination. See, e.g., Bob Jones University v. United

States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983) ; McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail

Transportation Co., 427 U.S. 273 (1976); Sullivan v.

Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229 (1969) ; Jones v.

Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) ; Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1964); Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

The Anti-Defamation League’s interest in these cases

arises both from its general goals of promoting and se

curing tolerance and equal justice and from its history of

fighting anti-Semitic hatred and violence. The Fourth

Circuit decision in the Shaare Tefila case, if left standing,

would deprive victims of anti-Semitic conduct of an impor

tant federal civil rights remedy. Moreover, the rule ar

ticulated in that decision would bar this essential remedy

to members of many other minority or ethnic groups,

including Arabs such as respondent in the Saint Francis

College case. Accordingly, the Anti-Defamation League

and the other amici appear to urge this Court clearly to

hold that section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42

U.S.C. §§ 1981 & 1982, protects all victims of racially-

motivated discrimination.

The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People is a New York non-profit corporation.

Among its principal aims are the promotion of equality

of rights and the eradication of caste or race prejudice

among the citizens of the United States.

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

is a national civil rights organization that was formed

in 1963 at the request of President Kennedy to provide

legal representation to blacks who were being deprived of

their civil rights. The Lawyers’ Committee has been ac-

4

tive throughout its history in pursuing legal remedies on

behalf of the victims of racial discrimination.

The American Jewish Committee is a national organ

ization, founded in 1906 and dedicated to the preserva

tion of civil rights and harmonious relations among

Americans of different backgrounds. The Committee

believes that the protection of civil rights for all best

secures the rights of Jewish Americans.

The American Civil Liberties Union is a non-profit

membership organization dedicated to protecting the fun

damental rights of the people of the United States.

The International Network of Children of Jewish Holo

caust Survivors, through affiliated groups in the United

States, Canada, Israel, and Europe, represents five thou

sand sons and daughters of European Jews who survived

the Nazi holocaust. The American Gathering and Federa

tion of Jewish Holocaust Survivors is an umbrella organ

ization representing the interests of tens of thousands

of survivors of the holocaust living in the United States.

The Jewish War Veterans, founded in 1896, is the

oldest active veterans’ organization in the United States.

It was established to oppose anti-Semitism and to call

attention to the contributions of Jews to American mili

tary history.

The Institute of Jewish Law, an organization affiliated

with Touro College Jacob D. Fuchsberg Law Center, was

founded in 1980 to facilitate research and scholarship in

the field of Jewish legal studies.

The Capital Legal Council of B’nai B’rith is a joint

unit of B’nai B’rith and B’nai B’rith Women. Composed

of Jewish members of the bench, bar, and related profes

sions, it seeks to strengthen through study and advo

cacy those traditional Jewish precepts— the rule of law,

the freedom and dignity of the individual, and the impor

tance of religious freedom— that are at the core of the

American experiment.

5

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

These cases present the issue of whether minority

and ethnic group members who do not belong to distinct

“non-white races,” but who allege discrimination of a

racial or racist character, are entitled to invoke section

1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 &

1982. In one case, a Jewish congregation’s lawsuit seek

ing relief for the admittedly racist desecration of its

synagogue was dismissed because Jews are not members

of a distinct “non-white” race. Shaare Tefila Congrega

tion, Pet. App. A, at 7a. In the other case, the lower

court expressly rejected such a narrow construction of the

statute and held that an Arab alleging racially-motivated

discrimination, despite his taxonomic classification as a

Caucasian, could state a cause of action under the statute.

Saint Francis College, Pet. App. at 25a-27a. Presumably

because of this clear conflict, the Court granted certio

rari and has set the cases for argument in tandem.

The controlling precedents of this Court, the legislative

history of the statute, and the plain realities of racial

prejudice require that the Court confirm that the Civil

Rights Act of 1866 protects all victims of racial dis

crimination. While this Reconstruction-era statute was

intended principally to protect blacks from victimization

by whites, this Court previously has removed any doubt

that the Act protects whites and non-whites alike from

discrimination that is racial in character. Accordingly,

and notwithstanding their Caucasian racial status, Arab

and Jewish victims alleging racially-motivated discrimi-

tion do in fact state claims under the Civil Rights Act

of 1866. Unless the plantiff’s allegations are inconsistent

with the notion of racial discrimination broadly con

strued, the plaintiff is entitled to proceed to his or her

proof and, if successful, to obtain the relief provided

by sections 1981 and 1982.

6

ARGUMENT

I. The Language and Legislative History of the Civil

Rights Act of 1866 Confirm That the Statute Protects

White and Non-White Minority and Ethnic Group

Victims of Racially-Motivated Discrimination.

Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1981 & 1982, extends to “all persons” various enumer

ated rights on the same terms as those rights are “en

joyed by white citizens.” 1 Ten years ago, this Court

held unambiguously that one need not be “non-white” to

invoke the statute. McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Trans

portation Co., 427 U.S. 273, 287 (1976). Prompted how

ever by McDonald's, dictum that the statute deals with

discrimination that is racial in character, id., the lower

federal courts, in the intervening years, have devised

numerous and conflicting tests by which the statute’s

coverage is withheld from or extended to various groups

that may not technically qualify as distinct “non-white

races.” The decisions of the courts of appeals in the

cases below, involving Jewish and Arab plaintiffs, reflect

at least two of the different and inconsistent approaches.

The decision of the Fourth Circuit in the Shaare Tefila

case clearly conflicts with the statute and its legislative

history. That decision would require a plaintiff to

1 While respondent in Saint Francis College invoked section

1981, petitioners in Shaare Tefila sought relief under sections 1981

and 1982. Presumably because their section 1981 claim was dis

missed on alternative grounds, including the one at issue here,

petitioners in Shaare Tefila sought review only of the lower courts’

disposition of their section 1982 claim. Recognizing the congruence

of the statutory language, legislative history, and decided cases for

purposes of resolving the question presented, this brief does not

distinguish between the two sections. Sections 1981 and 1982 both

originated in section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Where, as

here, the relevant language is the same in both statutes, there is

“no reason to construe these sections differently.” Tillman v.

Wheaton-Haven Recreation Ass'n, 410 U.S. 431, 440 (1973) ; ac

cord, Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160, 171 (1976).

7

establish his membership in a distinct “non-white race”

in order to invoke the Act. As the discussion below con

firms, the language of the statute contains no such

restriction, and instead was intended to protect all victims

of discriminatory conduct of a racial or racist character;

Congress clearly anticipated that such conduct would be

actionable when directed at members of a wide array of

minority or ethnic groups.

A. The Racial Character of the Discrimination Rather

Than the Racial Status of the Plaintiff is the Focus

of the Statute.

This Court’s inquiry in the first instance should focus

on the language of the statute. In sweeping terms, the

Act’s protections are afforded to “all persons.” There

are no words specifically limiting the class of intended

beneficiaries to members of certain races, “white” or

“non-white.” Indeed, the word “race” does not appear

in the statute as presently codified.

Despite the apparent breadth of the Act, the Fourth

Circuit panel below affirmed the dismissal of petitioners’

claims because Jews are not members of a “racially

distinct group” that is “commonly considered to be non

white [] .” Shaare Tefila, Pet. App. A, at 7a. The un

articulated rationale must have been that because Jews

are “white,” they cannot suffer discrimination cognizable

under the statute at the hands of other whites. As the

majority and concurring opinions of the Third Circuit

panel in Saint Francis College demonstrate, the statute

and this Court’s prior constructions of the statute will

not allow such a limited reading. Pet. App. at 23a-24a;

id. at 31a-32a (Adams, J., concurring).

In McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co.,

427 U.S. 273 (1976), the Court considered whether white

persons alleging that they had suffered discrimination

resulting from favoritism to blacks could invoke the

8

statute. Construing the same statutory language— “ all

persons” entitled to the same rights “enjoyed by white

citizens”— the Court squarely held that one need not be

“non-white” to state a claim under the statute. Id. at

287.

The Court in McDonald emphasized that “ the statute

explicity applies to ‘all persons’ (emphasis added), in

cluding white persons.” Id. (emphasis and parenthetical

in original). The statute’s qualifying phrase— “ as is

enjoyed by white citizens”— was designed not to limit

the statute’s applicability to non-whites, but rather “ to

emphasize the racial character of the rights being pro

tected.” Id. (quoting Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780,

791 (1966)). Rachel, upon which the Court relied in

McDonald, and its companion case, City of Greenwood v.

Peacock, 384 U.S. 808 (1966), decided under the re

moval provisions of the 1866 Civil Rights Act, involved

state criminal prosecutions of groups of civil rights

workers. As in McDonald, the Court considered the na

ture of the conduct, not the race of the person alleging

discrimination, in determining the availability of the fed

eral remedy. Rachel, 384 U.S. at 791, 805.

This Court adopted precisely the same construction—

one stressing the character of the rights being protected,

rather than the “race” of the plaintiff— in Jones v.

Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968), where the

Court pointed out that “all racially motivated depriva

tions of the rights enumerated in the statute” are

covered. Id. at 426 (emphasis in original). Indeed, once

one accepts McDonald’s holding that whites and non

whites alike can invoke the statute, racial status should

become largely irrelevant; racial motivation and char

acter should become the central issues. This conclusion is

also supported by the consistent line of cases permitting

a white associating with a black to seek relief under the

statute for discriminatory conduct motivated by that as

sociation. See Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation

9

Ass’n, 410 U.S. 431, 434 (1973); Sullivan v. Little Hunt

ing Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229, 237 (1969); Woods-Drake

V. Lundy, 667 F.2d 1198, 1201 (5th Cir. 1982). In such

cases, the plaintiff’s claim is based not on his or her

racial status, but on the racial character of the rights

protected.

The panel in Shaare Tefila disregarded the holdings of

this Court and refused to consider the racial character of

the conduct and rights involved. Instead, looking solely

at the “race” of the plaintiffs, it held that since Jews

are not “non-whites,” no cause of action possibly could be

stated. But given the uncontradicted admissions that the

defendants in Shaare Tefila acted upon a belief that their

Jewish victims belonged to a distinct and inferior non

white race,2 a cause of action premised on the established

racial character of defendants’ conduct was stated under

this Court’s holding in McDonald.3 As the panel in Saint

Francis College recognized, the statute does not require

a plaintiff to prove his “racial pedigree,” but rather to

allege that his membership in a distinct group has sub

jected him to “racially-based” prejudice. Pet. App. at

26a. This Court should reverse the Fourth Circuit’s de

cision and reaffirm that neither the statute nor this

Court’s prior decisions require a section 1981 or 1982

plaintiff to establish membership in a distinct “non

white” race.

2 See Shaare Tefila, Pet. App. A, at 12a-13a (Wilkinson, J., dis

senting) ; Brief for Appellees at 5, Shaare Tefila V. Cobb (4th Cir.

1986).

3 The “racial character” of alleged discrimination may be pleaded

in a variety of ways, and could include allegations of racial ani

mosity on the part of the defendants, plaintiff’s membership in a

group perceived to constitute a “race” or that is typically subject

to prejudice with racial overtones, or by other assertions that sug

gest racial or racist conduct. The types of allegations that would

satisfy a “racial character” requirement are explored more fully in

Part III, infra.

10

B. The Statute Was Intended to be Construed Broadly

and to Protect Minority and Ethnic Group Members

Regardless of Whether They Belong to Distinct

Non-White Races.

This Court has repeatedly emphasized that the Civil

Rights Act of 1866 should be generously applied and it

has insisted that “ ‘ingenious analytical instruments’ . . .

[not be employed] to carve . . . exception [s]” from the

statute. Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 437

(1968) (quoting United States v. Price, 383 U.S. 787,

801 (1966)).4 The McDonald Court rejected such an

“ analytical instrument” when it determined to empha

size the “ racial character” of the rights and conduct in

volved, rather than the racial status of the plaintiff. In

giving content to this concept of “racial character” and

determining the rights Congress intended to protect un

der sections 1981 and 1982, the Act should be construed

broadly. The propriety of such a broad construction is

clearly justified by the legislative history of the statute,

which demonstrates that the concept of “race” as under

stood and used by the 39th Congress was meant to

encompass a far broader range of groups than just the

“ non-whites” protected by the Fourth Circuit below.

Introducing the Civil Rights Act of 1866, Senator

Trumbull described the bill as intended “ to protect all

persons in the United States in their civil rights” and

emphasized that it applied to “every race and color.”

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 211 (1866). Repre

sentative Wilson, Chairman of the House Judiciary Com

mittee and the bill’s floor manager in the House, stressed

that the measure would “protect our citizens, from the

4 See City of Memphis v. Greene, 451 U.S. 100, 120 (1981)

(statute’s language to be “broadly construed” ) ; Sullivan v. Little

Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229, 237 (1969) ( “narrow construc

tion of the language . . . would be quite inconsistent with the

broad and sweeping nature of the protection meant to be af

forded” ) .

11

highest to the lowest, from the whitest to the blackest, in

the enjoyment of the great fundamental rights which

belong to all men.” Id. at 1118.

While there can be no doubt that the Act was intended

primarily to protect the rights of blacks, it is likewise

clear that Congress did not intend to limit “race” by a

color-based definition. In overriding President Johnson’s

veto of the Act, Congress reaffirmed that:

“This bill, in that broad and comprehensive philan

thropy which regards all men in their civil rights as

equal before the law, is not made for any class or

creed, or race or color, but in the great future that

awaits us will, if it become a law, protect every

citizen, including the millions of people of foreign

birth who will flock to our shores to become citizens

and to find here a land of liberty and law.”

Id. at 1833 (emphasis supplied). As this passage demon

strates, sections 1981 and 1982 were never intended by

Congress to apply solely to non-whites, but rather, as the

statute provides, to “all persons.” 5

The term “ race,” as used in the debates, was meant

to be given a broad meaning so that it would encompass

every “class or creed, or race or color.” Id. This broad

meaning is evident in Representative Shallabarger’s state

ment:

5 In an extended analysis of the statute’s legislative history, this

Court observed in McDonald that the Act “was routinely viewed, by

its opponents and supporters alike, as applying to the civil rights

of whites as well as non-whites.” 427 U.S. at 289. After examining

the background of the statute’s enactment, one district court re

cently concluded that “the legislative history indicates that (per

haps except for distinctions based on gender and age) Congress

intended to ensure that all citizens were to enjoy the same civil

rights.” Ortiz v. Bank of America, 547 F. Supp. 550, 555 (E.D.

Cal. 1982) ; see also Note, National Origin Discrimination Under

Section 1981, 51 F ordham L. Rev. 919, 934 & n.104 (1983) (indi

cating that Congress intended gender and age to be the only limi

tations on the statute’s scope).

12

“Who will say that Ohio can pass a law enacting

that no man of the German race, and whom the

United States has made a citizen of the United

States, shall ever own any property in Ohio . . . .

If Ohio may pass such a law, and exclude a German

citizen . . . because he is of the German nationality

or race, then . . . you have the spectacle of an Ameri

can citizen admitted to all its high privileges and en

titled to the protection of his Government . . . and

yet that citizen is not entitled to either contract,

inherit, own property, work, or live upon a single

spot of the Republic, nor to breathe its air.”

Id. at 1294; see also id. at 1757 (noting President John

son’s objection that the bill would make citizens of

“ Chinese and Gypsies” ).

The legislative history of the statute, including the

generalized comments in that history about members of

different “races,” must also be read in light of the com

mon understanding of the term “race” at the time.8 A

leading contemporary dictionary defined “race” as fol

lows: “A race is the series of descendants indefinitely.

Thus all mankind are called the race of Adam; the Is

raelites are of the race of Abraham and Jacob.” N.

Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Lan

guage 903 (C. Goodrich rev. Springfield, Mass. 1860)

(emphasis in original). This sweeping contemporaneous

understanding of “race” confirms that all types of groups

were intended to benefit from the Act.

This Court should embrace that common and broad

understanding of “race,” not only because it conforms to

the legislative history context, but because it is the cor

rect and traditional method of interpreting the statute.

In addressing the meaning of racial terminology, this

Court has previously noted: 6

6 At least one of the opponents of the Act noted during floor

debate the imprecise and potentially boundless meaning of “race.”

See Greenfield & Kates, Mexican Americans, Racial Discrimination,

and the Civil Rights Act of 1866 , 63 Cal . L. Rev. 662, 672 (1975).

13

“ It is in the popular sense of the word, therefore, that

we employ it as an aid to the construction of the

statute, for it would be obviously illogical to convert

words of common speech used in a statute into words

of scientific terminology when neither the latter nor

the science for whose purposes they were coined was

within the contemplation of the framers of the stat

ute or of the people for whom it was framed. The

words of the statute are to be interpreted in ac

cordance with the understanding of the common man

from whose vocabulary they were taken.”

United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, 261 U.S. 204, 208

(1923) ; see also Morrison v. California, 291 U.S. 82, 85-

86 (1934). Against this background, the legislative his

tory demonstrates that any “scientific” limitation of the

Act to distinct “non-white races” would be ill-founded.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was adopted against the

background of sectional conflict by men who had seen the

Nation’s future threatened by issues of race and status.

They were determined that, henceforth, “all persons”

would be relieved of disabilities and harm by reason of

any involuntary status attributed to ancestry, physiog

nomy, or ethnicity. Knowing well the dangers of group

antagonism, they sought safety for the Nation by declar

ing that no American could be treated as an alien sub

ject to intimidation, suppression, or expulsion from the

civic community. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 must be

read to have a reach as broad as this purpose.

II. Federal Remedies for Racially-Discriminatory Conduct

Should Not be Limited by Narrow and Arbitrary Defi

nitions of “Race.”

The Fourth Circuit panel below— despite the uncon

tradicted evidence of the racist character of the syna

gogue desecration— dismissed petitioners’ claims because

Jews do not belong to a distinct “non-white” race. Shaare

Tefila, Pet. App. A, at 7a. The panel determined that

the defendants’ belief that Jews are members of a

14

separate and inferior “race” was unfounded and hence

held that their conduct could not be actionable as racial

discrimination. In essence, the lower court purported to

“excuse” defendants’ admitted racism because defend

ants’ racist conduct lacked a sound scientific basis. Such

a narrow interpretation of the statute’s scope both ig

nores the true character of racism and illustrates the

inappropriateness of restrictive judicial definitions of

race.7

Judge Seth, in considering the applicability of the stat

ute to minority groups, aptly observed that racists are

“poor anthropologists” and that racial “ [prejudice

is based on all the mistaken concepts of ‘race.’ ” Manza-

nares v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 593 F.2d 968, 971 (10th

Cir. 1979) ; see also Shaare Tefila, Pet. App. A, at 11a

(Wilkinson, J., dissenting); S. Washburn, The Study of

Race, in The Concept of Race 243, 254 (A. Montagu ed.

1964). This connection between misbegotten notions of

race and racial prejudice is a commonplace. But such

misbegotten notions must not be ignored if the statute is

to apply to “all racially motivated deprivations of . . .

rights,” Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 426

(1968) (emphasis in original).

On the theory that defendants’ “ subjective, irrational

perceptions” that Jews are a race should not be con

trolling, the Fourth Circuit panel below refused to permit

the plaintiffs to invoke the statute. Shaare Tefila, Pet.

App. A, at 7a. This holding not only clashes with this

Court’s recognition that the statute applies to “all racially

motivated” conduct; it also ignores the fact that anti-

Semitism has long been the product of such racial mis

perceptions. The racist motivations of defendants in

7 The amici reject the notion that Arabs or Jews should be

classified as members of a distinct “race,” but, as made clear

throughout this brief, submit that the statute must be construed

to cover acts of racism against Arabs and Jews.

15

Shaare Tefila are similar to the motivations that have

animated anti-Semitic conduct for centuries.

A recent study of the character of anti-Semitism

observed that:

“ In medieval times hostility to the Jew, whatever

its underlying social or psychological motivations,

was defined primarily in religious terms. From the

fifteenth century onward this was no longer true,

and Jew hatred was redefined, becoming at first

partly, and then, at least in theory, wholly racial.”

B. Lewis, Semites and Anti-Semites 81 (1986). The pre

dominantly racist content of anti-Semitism, from at least

the time of the Spanish Inquisition through Nazi Ger

many to present-day America, is a matter of historical

record. See id. at 26-33, 81-100; T. Gossett, Race: The

History of an Idea in America 9-12, 292-93, 371-72, 449

(1963) ; see also Shaare Tefila, Pet. App. A, at 16a-17a

(Wilkinson, J., dissenting) ; Ortiz v. Bank of America,

547 F. Supp. 550, 567 (E.D. Cal. 1982). Six million

Jews were not murdered in the holocaust as a result of

differences in religious doctrine; they were the victims of

a twisted and avowedly racist Nazi ideology that meas

ured Jewishness by blood rather than belief. Hence, ap

plication of the statute to Jews would not require a court

to indulge the isolated racist idiosyncracies of individual

defendants. The history of anti-Semitism amply, if not

tragically, demonstrates its pervasive racist character.

Similarly, discrimination against Arabs has long as

sumed a decidedly racist cast. Arabs include natives of

Near Eastern countries such as Syria, Egypt, Yemen,

Lebanon, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, and their descendants.

Though Arabs are taxonomically classified as Caucasian,

they often (though certainly not invariably) have a skin

color darker than that of Caucasians of European descent.

Bigots have seized upon Arabs’ supposedly distinctive

physical and ethnic qualities in stereotyping and dis

criminating against them. Examples of explicitly racist

16

anti-Arab epithets and conduct have surfaced with dis

maying frequency in recent years.8

An obvious irony of the consolidation of these cases is

that both Jews and Arabs fall within the crude rubric

“ Semite,” which technically is a language classification,

though it also has long had racial connotations. See G.

Barton, A Sketch of Semitic Origins 28 (1902) ; B.

Lewis, Semites and Anti-Semites 44-45, 50 (1986).9

Racists, among others, have lumped Arab and Jew to

gether as targets of discrimination. For example, a re

strictive land covenant successfully challenged in the

early 1970’s forbade transfer “ ‘to any person of the

Semitic race, blood or origin, which racial description

shall be deemed to include Armenians, Jews, Hebrews,

Persians and Syrians. . . ” Mayers v. Ridley, 465 F.2d

630, 631 n.2 (D.C. Cir. 1972) (emphasis supplied). It is

clear that bigots have historically treated Jews and

Arabs— sometimes separately, sometimes together—as

racially distinct from the “white” majority.

The test of the Fourth Circuit, which requires proof

of actual membership in a separate “ non-white” race,

ignores the fact that discrimination against Caucasian

sub-groups such as Arabs and Jews frequently assumes

an undeniably racist quality. Racially-motivated discrim

ination against Arabs and Jews is no different in kind

or character from the bigotry directed at taxonomically-

8 See, e.g., Dickey, Falling Out of Love with the Arabs, News

week , Aug. 25, 1986, at 44 (describing a recent “surge of anti-

Arab jingoism [and] increasing bigoted talk about ‘camel jockeys’

and ‘sand niggers’ ” ) ; Newell, Arab-Bashing in America, News

week, Jan. 20, 1986, at 21.

9 See also J. Worcester, A Universal and Critical Dictionary of

the English Language 656 (Boston, Mass. 1874) (defining “She-

mitic” as relating to various languages, including Arabic and

Hebrew; defining “ Shemitism” as “ [t]he Shemitic race” ) . The

term “Shemite” preceded that of “ Semite,” and is traceable to

Shem, one of Noah’s sons and the mythological forebear of the

Shemites.

17

defined racial minorities. Adoption of a scientific “ race

test” would thus deny real victims of racist conduct an

important remedy.10

Even if a “ race test” arguably were appropriate for

determining eligibility to invoke the Act, a restrictive,

pseudo-scientific, color-based “race test” would be both

improper and unseemly. In interpreting “ race” for pur

poses of this civil rights law, even if the contemporary

definition of race were not as broad as that at issue here,

the correct approach would be to define the term and the

statute as broadly as necessary to cover acts that are

racial or racist in character. Both lay and scientific

meanings admit to such sweeping applications.

It is commonly acknowledged that there is no defini

tional consensus in the scientific or academic community

about “ race.” See generally A. Montagu (ed.), The Con

cept of Race (1964) (collecting various scholarly essays

on topic); see also United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind,

261 U.S. 204, 212 (1923); J. Barzun, Race: A Study in

Superstition 203-07 (1965). Indeed, to the extent that

there is agreement, it is on the proposition that the

purpose of any racial classification dictates its scope and

content. See Ortiz v. Bank of America, 547 F. Supp. 550,

565-67 (E.D. Cal. 1982); S. Molnar, Races, Types, and

Ethnic Groups 13 (1975). In the lay community, “ race”

remains an extraordinarily open-ended concept; it is de

fined as broadly in today’s leading dictionaries as it was

over 100 years ago, when the Civil Rights Act was

passed.11

10 “Since the evil at which the statutes are aimed is discrimina

tion, the scientific validity of the discriminator’s racial definition

is irrelevant.” Greenfield & Kates, Mexican Americans, Racial Dis

crimination, and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 63 Cal . L. Rev. 662,

678 (1975). In enforcing a statute designed to remedy racist con

duct, the defendants’ racist misperceptions must be considered,

even if they are irrational and confused.

11 Compare Webster’s Third New International Dictionary 1870

(1981) (“descendants of a common ancestor” or “a class or kind of

18

Despite the fact that Arabs and Jews should not be

classified as scientifically distinct “ races,” it is nonethe

less true that each group has been considered to consti

tute a “ race.” The mistaken belief that Jews belong to

a separate “ race” is not only held by anti-Semites; many

with benign attitudes towards Jews have referred to

them as a “race.” See A. Montagu, Man’s Most Dan

gerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race 353 (5th ed. 1974).12

In fact, a standard dictionary in America still illustrates

its definitions of “race” with unfortunate references to

the “ Hebrew race” and the “Jewish race.” Webster’s

Third New International Dictionary 1870 (1981). Cf.

N. Webster, An American Dictionary of the English

Language 903 (C. Goodrich rev. Springfield, Mass. 1860)

(“ the Israelites are of the race of Abraham and Jacob” )

(emphasis in original).

Arabs are also popularly thought of as a separate

“ race.” In terms that today would be regarded as racist,

individuals with common characteristics, interests, appearance, or

habits” ) with N. Webster, An American Dictionary of the English

Language 903 (C. Goodrich rev. Springfield, Mass. 1860) (“the

series of descendants indefinitely” ).

12 See, e.g., Hirabayashi v. United, States, 320 U.S. 81, 111

(1943) (Murphy, J., concurring) (wartime treatment of Japanese

Americans “bears a melancholy resemblance to the treatment ac

corded to members of the Jewish race in Germany and in other

parts of Europe.” ) ; Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697, 703 (1931)

(Hughes, C.J.) (“Jewish Race” ) ; I. Berlin, Against the Current:

Essays in the History of Ideas 274-75 (1980) (describing Dis

raeli’s theory of the “Jewish race” ) ; G. Eliot, Daniel Deronda

(1876) (sympathetic 19th Century fictional treatment of Jews

laced with references to the “Jewish race” ) ; Letter from Learned

Hand to Charles H. Grandgent (Nov. 14, 1922) (urging that Har

vard College not impose a “limitation based upon race” to restrict

admission of Jews), reprinted in L. Hand, The Spirit of Liberty 21

(3d ed. 1974) ; The Sun (New York), Sept. 19, 1870, at 2, cols. 2-3

(“ The Jews are not merely a church; they are a race. . . . The Jewish

race is one of the most tenacious and strongly marked in all the

history of man.” ), reprinted in M. Schappes (ed.), A Documentary

History of the Jews in the United States 541 (3d ed. 1971).

19

a district court opinion dating back several decades

soberly analyzed the group characteristics of Arabs and

concluded that “as a class they are not white” and would

not have been considered “white” by the Congress that

enacted this country’s first naturalization statute in 1790.

In re Hassan, 48 F. Supp. 843, 845-46 (E.D. Mich.

1942). But see Ex parte Mohriez, 54 F. Supp. 941 (D.

Mass. 1944). The notion that Arabs constitute a distinct

race is not a new or novel one. See R. Benedict, Race

and Racism 13 (1942) (describing different groupings of

the Arab race).

While most racial labelling is misguided, the reality

is that Arabs, Jews, and many other ethnic or minority

groups have been widely, though erroneously, regarded

as belonging to “ races.” Such beliefs merely reflect the

way “ race” has been understood from at least the 19th

Century to this day in popular and even academic par

lance. In the face of such open-ended understandings of

“ race” and the express purpose of the statute to remedy

all racially-motivated acts of discrimination, a construc

tion of the statute that seeks to limit its coverage to

scientifically-verifiable “non-white races” is a misguided

enterprise. Moreover, such an abstract and restrictive

reading of the statute would leave countless victims of

discrimination plainly racist in character without any

effective remedy. The correct result is to apply the stat

ute to all victims of racially-motivated discrimination

and to avoid formulation of a technical “ race test.”

A restrictive reading of the statute— one which ig

nores the racial motivations of defendants and the

broader understandings of “ race” prevalent at the time

of the Act or in some modem lay usage— would require

the federal courts to devise such a “ scientific” definition

of “race” and to assume the role of arbiter of racial clas

sifications. It could result in unseemly judicial inquiries

into the racial background of litigants and the formula-

20

tion of artificial and technical racial distinctions.13 * The

breadth of the statute, however, renders such a defini

tional role unnecessary because of its sweeping prohibi

tion of all racially-motivated discrimination. This Court

therefore should reject the color-based, “ scientific” test of

the Fourth Circuit panel below and make it clear that a

plaintiff need not “prove his [racial] pedigree,” Saint

Francis College, Pet. App. at 26a, before he is permitted

to invoke a statute that by its terms protects “ all

persons.”

III. Section 1981 and 1982 Plaintiffs Should be Permitted to

Proceed With Their Claims Unless Their Allegations

Are Clearly Inconsistent With the Possibility That

They Were the Victims of Racial Discrimination.

The central flaw of the Fourth Circuit’s decision in

Shaare Tefila is that it dismissed the Congregation’s

claim in the teeth of allegations of conduct that was un

mistakably racial or racist in character. The defendants

conceded that they believed Jews to constitute a separate

and inferior non-white race. They desecrated plaintiffs’

synagogue with anti-Semitic emblems redolent of racially-

inspired Jew hatred. Moreover, Jews, though members

of a religion, for centuries and to this day commonly

have been thought of, albeit mistakenly, as a separate

“race.”

The correct rule of law at the pleading stage should be

that ̂allegations which, if proven, would establish dis

crimination that is racial in character are adequate to

state a cause of action. In light of the purpose of the

13 See Note, Legal Definition of Race, 3 Race Rel. L. Rep. 571

(1958) (reviewing- statutory definitions of racial groups and judi

cial interpretations thereof, particularly as applied in the mis

cegenation context) ; compare United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind,

261 U.S. 204, 209-15 (1923) (high caste Hindu not a “free white

person” for naturalization purposes) with In re Mohan Singh, 257

F. 209 (S.D. Cal. 1919) (reaching opposite result apparently under

mined by the Thind case).

21

statute to combat racial discrimination in its various

forms and the open-ended and imprecise meanings of

“race” since 1866, it would be improper to screen poten

tial plaintiffs by requiring allegations of membership in

a “non-white race.” The better approach would be to

require only allegations of discrimination of a racial

character.14

There are numerous factors—none of which is ex

clusive— that the courts should consider in determining

whether a plaintiff has adequately pleaded and can plaus

ibly assert that he was the victim of racial discrimina

tion, as opposed to discrimination on some other basis not

prohibited by the statute. The factors to be considered

should include the plaintiff’s allegations concerning the

racial or racist motivations of the defendant. In addi

tion, the court should weigh the plaintiff’s allegations

regarding his own race or skin color. Equally important

factors are the extent to which the plaintiff belongs to

an identifiable group that is commonly or historically re

garded by bigots or lay persons as constituting a “ race,”

as the term is understood in a broad sense. Unless the

plaintiff’s allegations are inconsistent with the notion

that he or she has suffered discrimination that is racial

or racist in character, a cause of action has been stated

and the plaintiff should be entitled to prove his or her

claim.15

14 Because the Arab and Jewish plaintiffs in these cases allege

racial discrimination, the Court need not determine the extent to

which the statute protects individuals claiming discrimination

solely on the basis of national origin, cf. Delaware State College v.

Ricks, 449 U.S. 250, 256 n. 6 (1980) (reserving question), or some

other criterion.

15 Numerous courts and commentators endorse an approach that

goes beyond) the “scientific” racial status of the plaintiff and in

cludes inquiry into one or more additional factors, such as those

described above, that are relevant to the racial character of dis

criminatory conduct. See Alizadeh v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 802 F.2d

111, 114-15 (5th Cir. 1986); Saint Francis College, Ret. App. at

22

The test proposed is flexible and directs the court’s

attention to any and all factors relevant to the existence

of racial discrimination. It recognizes that the racial

status of the victim is not the only measure of racism.

This test would also relieve the courts of the impossible

and unseemly task of analyzing in a pseudo-scientific

fashion the “races” of litigants. In short, it would ac

knowledge the true nature of racism and afford the

statute’s protection to all victims of racial discrimina

tion. By any measure, the Arab and Jewish plaintiffs in

these cases have pleaded discrimination that is racial in

character.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the amici urge this Court

to reverse the decision of the Fourth Circuit below, to

affirm the ruling of the Third Circuit below, and to’ re

solve these cases in a manner making clear that the Civil

Rights Act of 1866 is available to all Arab and Jewish

victims of racial discrimination.

25a-27a; Erebia v. Chrysler Plastic Prod. Corp., 772 F.2d 1250,

1253-54 (6th Cir. 1985), cert, denied, 106 S. Ct. 1197 (1986);

Ramos v. Flagship International, Inc., 612 F. Supp. 148, 151

(E.D.N.Y. 1985); Greenfield & Kates, Mexican Americans, Racial

Discrimination, and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 63 Cal. L. Rev.

662 (1975). Other authorities maintain that there is no “racial”

requirement and that virtually any victim of group-based: discrimi

nation may invoke the Act. See Manzanares v. Safeway Stores,

Inc., 593 F.2d 968, 971-72 (10th Cir. 1979); Ortiz v. Bank of

America, 547 F. Supp. 550, 568 (E.D. Cal. 1982); Note, National

Origin Discrimination Under Section 1981, 51 F ordham L. Rev.

919, 939, 942 (1983).

23

Of Counsel:

Michael Schultz

Meyer E isenberg

David Brody

Edward N. Leavy

Steven M. Freeman

Jill L. Kahn

A nti-Defamation League

of B ’nai B ’rith

823 United Nations Plaza

New York, New York 10017

(212) 490-2525

and

1640 Rhode Island Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 857-6660

Menachem Z. Rosensaft

International Network

of Children of Jewish

Holocaust Survivors

425 Park Avenue

New York, New York 10022

(212) 407-8000

Robert S. R ifkind

Samuel Rabinove

Richard T. Foltin

A merican Jewish Committee

165 East 56th Street

New York, New York 10002

(212) 751-4000

E ileen Kaufman

Institute of

Jewish Law

300 Nassau Road

Huntington, New York 11743

(516) 421-2244

November 1986

Respectfully submitted,

Gregg H. Levy *

Mitchell F. Dolin

Covington & Burling

1201 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W.

Post Office Box 7566

Washington, D.C. 20044

(202) 662-6000

Counsel for Amici Curiae

Harold R. Tyler

James Robertson

Norman Redlich

W illiam L. Robinson

Judith A. W inston

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Rachael P ine

A merican Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 944-9800

Joseph A. Morris

Capital Legal Council

of B’nai B’rith

5500 Friendship Boulevard

Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815

Grover G. Hankins

Joyce H. Knox

National A ssociation

for the Advancement of

Colored People

4805 Mount Hope Drive

Baltimore, Maryland 21215

(301) 358-8900

* Counsel of Record