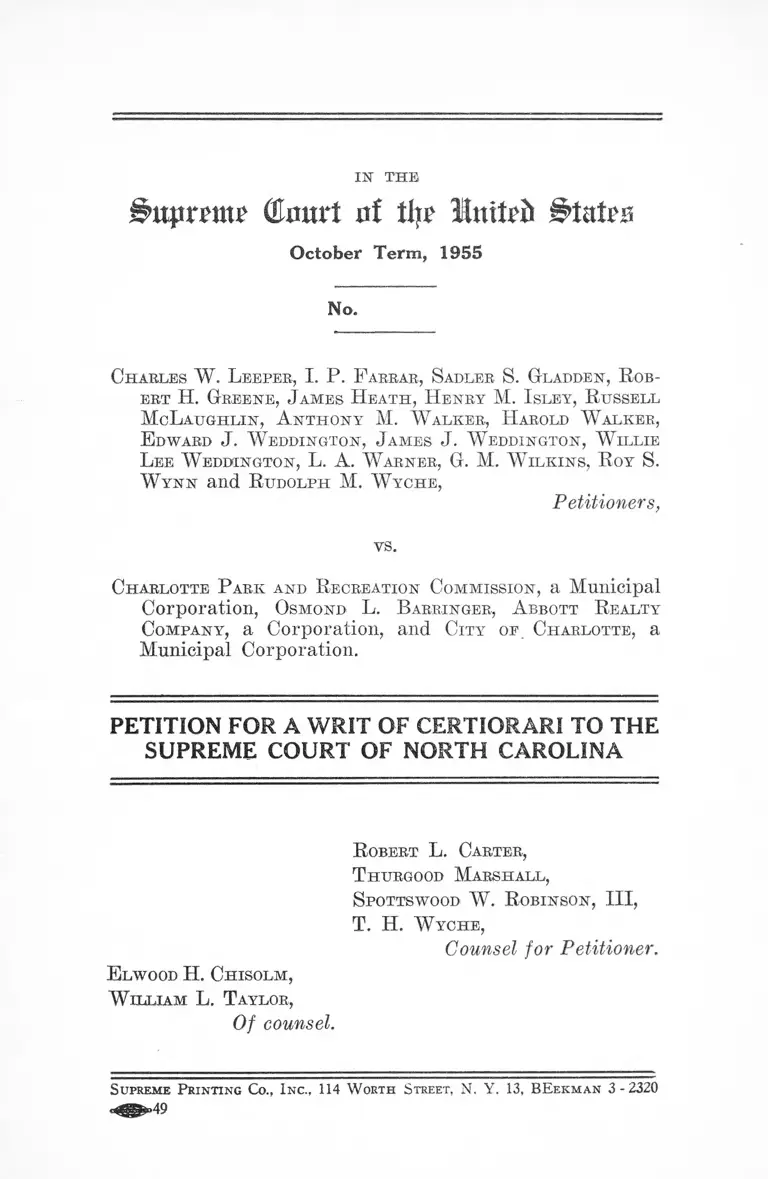

Leeper v. Charlotte Park and Recreation Commission Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1955

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Leeper v. Charlotte Park and Recreation Commission Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1955. 927a6af2-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8b304076-4eaa-40ab-b76f-9e76bd4746e4/leeper-v-charlotte-park-and-recreation-commission-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IK THE

©Hurt nf % § U tn \

October Term, 1955

No.

Charles W. P eeper, I. P. F arrar, Sadler S. Gladden , R ob

ert H . Greene, J am es H ea th , H enry M. I sley, R ussell

M cL au g h lin , A n th o n y M. W alker , H arold W alker ,

E dward J. W eddington , J am es J. W eddington , W illie

L ee W eddington, L . A. W arner , G. M. W il k in s , R oy S.

W y n n and R udolph M. W yghe ,

Petitioners,

vs.

C harlotte P ark and R ecreation C om m ission , a Municipal

Corporation, Osmond L. B arringer, A bbott R ealty

Co m pan y , a Corporation, and C ity of C harlotte, a

Municipal Corporation.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood M arshall ,

S pottswood W. R obinson , III,

T. H. W y ch e ,

Counsel for Petitioner.

E lwood H. Ch iso lm ,

W illiam L. T aylor,

Of counsel.

S upreme P r in t in g Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekm an 3 - 2320

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinions Below ...............................................................

Jurisdiction .....................................................................

Question Presented .......................................................

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved . . .

Statement of the C a se ...................................................

Reasons for Allowance of the W r it ..............................

Conclusion.........................................................................

PAGE

2

2

2

3

3

7

18

Appendix A :

Opinion of the Supreme Court of North Caro

lina entered June 30, 1955 ............................... 19

Judgment of the Supreme Court of North Caro

lina entered June 30, 1955 ............................... 37

Appendix B :

Petition for Rehearing D enied............................. 38

Appendix C

An Ordinance to Set Aside and Dedicate Certain

Lands of the City of Charlotte for Park and

Recreation Purposes ......................................... 39

Exhibit “ A ” ....................................................... 42

Appendix D :

An Ordinance Amending the Ordinance Entitled

“ An Ordinance to Set Aside and Dedicate Cer

tain Lands of the City of Charlotte for Park

and Recreation Purposes” ............................... 47

11

Table of Cases

PAGE

Allison v. Sharpe, 209 N. C. 477, 184 S. E. 27 (1936) l ln

American Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312 U. S.

321 .................................................................................. 13

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 ..............8, 9,10,13,15,17

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ................................... 7,17

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252..........................

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 .......... 7

Brown v. Independent Baptist Church of Woburn,

325 Mass. 645, 91 N. E. ed. 922 (1950) ..................12n, 17

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 ............................... 8

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 ...................... 13

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ..................................... 12

Claremont Improvement Club v. Buckingham, 89

Cal. App. 2d 32, 200 P. 2d 47 (1948) ...................... 16

Clifton v. Puente, 218 S. W. 272 (Tex. Civ. App.

1949).............................................................................. 16

Collette v. Town of Charlotte, 114 Vt. 357, 45 A. 2d

203 (1946) ................................................................... 12n

Copenhaver v. Pendleton, 155 Va. 463, 155 S. E. 802

(1930) ........................................................................... 12n

Ex Parte Laws, 31 Cal. App. 846,193 P. 2d 744 (1948) 15

First Universalist Society v. Boland, 155 Mass. 171,

29 N. E. 524 (1892 )..................................................... 12n

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 ........................ 9n

Hall v. Turner, 110 N. C. 292,14 S. E. 791 (1892) . . . 21n

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668, rev’g, 160 La. 943,

107 So. 704 (1926) ..................................................... 8,10

Holmes v. Atlanta, — U. S. — 100 L. ed. (Advance p.

76) ............................................................................. 7,8,9,17

Home Building & Loan Assn. v. Blaisdell, 290 U. S.

398 .................................................................................. 14

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 2 4 ......................................... 15,17

I l l

PAGE

Kern v. Newton, 151 Kan. 565, 100 P. 2d 709 (1940) 9n

Land Development Co. v. New Orleans, 17 F. 2d 1016

(CA 5th 1927), rev’g, 13 F. 2d 898 (E. D. La. 1926) 10

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 ..................................... 8, 9n

Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (S. D. W. Ya.

1948) ............................................................................. 9n

Liberty Annex Corp. v. Dallas, 289 S. W. 1067 (Tex.

Civ. App. 1927), 19 S. W. 2d 845 (Tex. Civ. App.

1929) .................................................. 15

Lide v. Mears, 231 N. C. I l l , 56 S. E. 2d 404 (1949) lln

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 8

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 5 0 1 ................................. 14

Mayor & City Council of Baltimore City v. Dawson,

— U. S. —, 100 L. ed. (Advance p. 75) ..............7, 8, 9,17

Nixon v. Condon, 286 IT. S. 7 3 .......................................

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 ................................. 9n

Norman v. Baltimore & O. R. Co., 294 U. S. 240 ........ 14

Republic Aviation Corp. v. National Labor Rela

tions Board, 324 U. S. 793 ........................................ 14

Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387 (CA 4th 1947), cert.

denied, 333 U. S. 875 ............................................ 9n

Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704, aff’g 37 F. 2d 712

(CA 4th 1930) ........................................................... 8 ,9n

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ..........8, 9,10,13,14,16,17

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U, S. 649, ............................... 9n

Turpin v. Jarrett, 226 N. C. 135, 37 S. E. 2d 124

(1946) ........................................................................... 12n

Twining v. New Jersey, 211 U. S. 7 8 ..........................

Tryon v. Duke Power Co., 222 N. C. 200, 22 S. E.

2d 450 (1942) ............................................................... l ln

Woytus v. Winkler, 357 Mo. 1082, 212 S. W. 2d 411

(1948) .......................................................................... 16

IV

PAGE

Williams v. Blizzard, 176 N. C. 146, 96 S. E. 957

(1918) ........................................................................... 12n

Other Authorities

American Jurisprudence, “ Estates,” Sec. 2 9 ......... 12n

Borchard, Declaratory Judgments 22 et seq. (2 Ed.

1941) ..................... l ln

Tiffany, Law of Real Property (3rd Ed.), Sec. 217 12n

IN THE

Shtpmttr (Unurt af tht Intt^ B utts

October Term, 1955

No.

---------------------- o-----------------------

Charles W. L eeper, I. P. F arrar, Sadler S. Gladden , R ob

ert H. Greene, J am es H ea th , H en ry M. I sley, R ussell

M cL a u g h lin , A n t h o n y M. W alker , H arold W alker ,

E dward J. W eddington, J am es J . W eddington , W illie

L ee W eddington, L. A. W arner, G. M. W il k in s , R oy S.

W y n n and R udolph M. W y ch e ,

Petitioners,

vs.

Charlotte P ark and R ecreation Comm ission , a Municipal

Corporation, Osmond L. B arringer, A bbott R ealty

Com pan y , a Corporation, and C ity of C harlotte, a

Municipal Corporation.

----------------------o----------------------

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the

United States and the Associate Justices

of the Supreme Court of the United States:

Petitioners respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgment of the Supreme Court of

North Carolina modifying, and affirming as modified, a

final judgment of the Superior Court of Mecklenburg

County, North Carolina, wherein originally the Charlotte

Park and Recreation Commission was plaintiff and the re

maining parties were defendants.

2

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of North Carolina is

reported at 242 N. C. 311 and at 88 S. E. 2d 114 and appears

as Appendix A to this petition. The opinion of the Superior

Court of Mecklenburg County is unreported and appears at

pages 86-94 of the record as printed for use of the Supreme

Court of North Carolina.1

Jurisdiction

The judgment sought to be reviewed was entered by the

Supreme Court of North Carolina on June 30, 1955 and

appears at page 37, Appendix A to this petition. Peti

tioners’ timely petition for rehearing was denied Novem

ber 1, 1955. This order appears at Appendix B to this peti

tion. The jurisdiction of this Court to review by writ of

certiorari the judgment in question is conferred by Title 28,

United States Code, Section 1257(3).

Question Presented

Can a state effectuate provisions contained in a deed

conveying real property for a public park to a municipal

recreation commission, purporting to cause a reverter of

part of the park property upon use by Negroes of a public

golf course therein, without denying to petitioners rights

secured by the due process and equal protection clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment and by Title 42, United States

Code, Section 1981?

1 Copies of the record as printed for use of the Supreme Court

of North Carolina, including the accompanying “ Pertinent Provi

sions of the Charter of the City of Charlotte As Taken from Exhibit

X III ,” are filed herein pursuant to Rule 21(4 ). References are to

the pages of this record.

3

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved

This case involves constitutional provisions, statutes and

ordinances as follows:

1. United States Constitution, Amendment 14, Section 1.

2. Title 42, United States Code, Section 1981.

3. Ordinance entitled “ An Ordinance to Set Aside And

Dedicate Certain Lands of the City of Charlotte for

Park and Recreation Purposes ’ ’ adopted by the City

Council of the City of Charlotte, North Carolina, on

February 21, 1929 (Appendix C).

4. Ordinance entitled “ An Ordinance Amending the

Ordinance Entitled ‘ An Ordinance to Set Aside and

Dedicate Certain Lands of the City of Charlotte for

Park and Recreation Purposes’ ” adopted by the

City Council of the City of Charlotte, North Caro

lina, on May 7, 1929 (Appendix D).

Statement of the Case

The facts are undisputed. They are established by the

findings of the Superior Court (R. 86-92), based upon an

agreed statement of facts (R. 60-86), and were relied upon

by the Supreme Court of North Carolina (242 N. C. at 312-

315, 88 S. E. 2d at 116-118) as the basis for its conclusions.

The City of Charlotte is a municipal corporation of the

State of North Carolina discharging governmental func

tions (R. 61, 87, 104). The Charlotte Park and Recreation

Commission is a public body corporate having ownership

of, general jurisdiction and control over all recreational

facilities in Charlotte, North Carolina (R. 60, 86-87,

103-104).

The Commission brought this action for a judgment

declaratory of the effect and validity of provisions in deeds

4

conveying to the Commission the real estate upon which is

presently located Revolution Park, a municipally owned and

operated park, in a portion of which the Commission oper

ates the Bonnie Brae Golf Course. The provisions in ques

tion purport to restrict the use of these public facilities to

white persons only; and, in the event such restriction is

violated, the land is to revert.

On or about August'31, 1927, several landowners offered

real estate to the City “ to be used by the City of Charlotte

through its Park and Recreation Commission for white

people’s parks and playgrounds, parkways and municipal

golf courses only” (R. 2-3, 7-8, 10-12, 61, 87, 104-105). The

offer further specified that in the event that the lands

should not be so used, the properties would revert to each

donor (R. 12, 61, 87, 105). On February 21, 1927, the City

enacted an ordinance accepting the offer and designating

the property “ as a park and recreation area for use by

people of the white race only” (Appendix C ; R. 3, 7-12,

62, 88, 105). On May 7, 1929, it adopted another ordinance

eliminating certain land from the park area and confirm

ing the original ordinance as so amended (Appendix D;

R. 3, 13-14, 62, 88, 105).

The park properties were conveyed to the Commission

by four separate deeds: Osmond L. Barringer, Abbott

Realty Company and City of Charlotte are three of the

grantors. Each provided that the properties should be

maintained as an integral part of a park and recreation area

(R. 3-4, 17-18, 25, 33, 38, 62-63, 88-89, 105-106). Each deed,

except that from the City, provided that the properties were

“ to be kept and maintained for the use of, and to be used

and enjoyed by, persons of the white race only” (R. 3-4,

17-18, 25, 33, 62-63, 88-89, 105-106); and all, except the deed

from Abbott Realty Company, contained provisions pur

porting to cause a termination of the Commission’s estate

5

in and a reverter of the property to the grantor thereof

upon use by Negroes of any portion of the park properties

(B. 3-4, 19, 27, 34, 38, 62-63, 88-89, 105-106).

The Bonnie Brae Golf Course is maintained and oper

ated by the Commission as a part of a system of supervised

recreation of the City (R. 64, 90, 107). It is the only course

provided or operated by the Commission or the City that

affords opportunities or facilities for playing the game of

golf (E. 64, 90, 107). The Commission maintains and

operates this course, the remainder of Revolution Park,

and all facilities therein exclusively for the use and enjoy

ment of white persons (R. 5, 64, 90, 107). All white persons

who pay the fees and charges and comply with the rules

and regulations relating to use of the course have been and

are afforded the right and privilege of admission thereto

and use thereof (R. 64, 90, 107). On the other hand, peti

tioners and all other Negroes, because of race or color, are

denied admission to and the use of the course (R. 64,

90,107).

On or about December 20, 1951, petitioners presented to

the Commission a petition alleging that they had been

denied the right and privilege of admission to and the use

of the Bonnie Brae Golf Course in violation of rights

secured to them by the Constitution and law of the United

States, and requesting that such discrimination cease

(R. 5-6, 64-65, 74-86, 90-91, 107-108). Shortly thereafter,

the Commission instituted this suit. The Commission did

not change its policy, and a suit was filed in the Superior

Court by petitioners seeking to enjoin the Commission from

refusing to bar them from the golf course.

From the outset and throughout these proceedings, peti

tioners have claimed that the operation of the reverter pro

visions upon use by Negroes of the Bonnie Brae Golf

6

Course, in consequence of the action, authority or sanction

of the State of North Carolina, would deny petitioners due

process of law and the equal protection of the laws and

would violate Title 42, United States Code, Section 1981

(R. 44-46). They specifically requested declarations to

that effect (R. 52-53). On the other hand, throughout this

litigation the Commission, along with Barringer and Abbott,

Realty Co. have asserted that the reverter provisions are

constitutionally valid and automatically operative.

The Superior Court concluded: (a) that the deeds in

question created valid determinable fees in the Commis

sion with possibilities of reverter to the grantors (R. 92-93,

109-110); (b) that in the event of the admission of Negroes

to any part of Revolution Park, the properties conveyed by

Barringer and Abbott Realty Company would immediately

re-vest in them by operation of law (R. 93, 94, 110, 111) ;

and (c) that, because the City had only one golf course,

the use of that course by Negroes would not cause a rever

sion to the City of that parcel conveyed to the Com

mission by the City since this would violate the Fourteenth

Amendment (R. 93-94, 110).

Petitioners excepted to the Superior Court’s conclu

sions insofar as they would sustain the operation of the

reverter provisions upon non-white use of the park prop

erties (R. 92-95). They perfected an appeal to the Supreme

Court of North Carolina on assignments of error (R. 95-

102), appropriately raising the federal questions presented

by this petition. That court modified the judgment of the

Superior Court, holding upon a construction of the deed

from the Abbott Realty Company that no reverter would

result, and, as modified, affirmed the judgment of the court

below on the ground that no state action would be involved

in the operation of the reverter provisions. 242 N. C. at

7

322, 88 S. E. 2d at 123 (see Appendix A ). The federal

questions were preserved by petitioners in their applica

tion for rehearing,2 which was denied.3

Reasons for Allowance of the Writ

1. It is clear that the state cannot directly or indirectly

burden the use and enjoyment of public parks and recrea

tional facilities with restrictions based upon race or color.

Mayor v. Dawson, ------ U. S. ------ , 100 L. ed. (Advance

p. 75); Holmes v. City of Atlanta,------U. S .------- , 100 L. ed.

(Advance p. 76). This is exactly what the Commission has

done. Moreover, it sought to shield its illegal conduct

against the reach of the Fourteenth Amendment on the

ground that the terms of 'the grants required imposition

of the assailed restrictions and that the property must

revert to the grantors if Negroes used the golf course.

The opinion below sanctions and sustains this position with

respect to the Barringer parcel and vindicates the Com

mission’s discriminatory policy. We submit that the Com

mission’s action and the decision below are in direct con

flict with the decisions of this Court condemning state en

forced racial distinctions in the use and enjoyment of public

facilities. Mayor v. Dawson, supra, and Holmes v. City of

Atlanta, supra. See also the School Segregation Cases

(Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, Bolling v.

Sharpe, 347 TJ. S. 497).

The City sought to implement the deed restrictions by

ordinances barring Negroes, solely as Negroes, from use of

Revolution Park (see Appendices C and D), and by restric

tions in its own deed to the Commission. This whole course

of conduct is illegal, and it is clear that these restrictions,

2 See pages 1-3 of the petition for rehearing in the record.

3 See Appendix B.

standing alone, could not be enforced or given court

sanction.

The ordinances are obviously unconstitutional. See

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60; Harmon v. Tyler, 273

U. S. 558, rev ’g, 160 La. 943, 107 So. 704 (1926); Richmond

v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704, alPg, 37 F. 2d 712 (CA 4th 1930).

Equally obvious, we submit, is the unconstitutional char

acter of the racial restrictions set out in the City’s convey

ance. Compare Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 and Bar-

rows v. Jachson, 346 U. S. 249, with Buchanan v. Warley,

supra-, Harmon v. Tyler, supra; and Richmond v. Deans,

supra.

The public parks belong to the citizens of Charlotte and

neither the City nor the Commission can impose racial con

ditions with regard to their use. Both seek to defeat this

constitutional proscription by imposing consequences on the

use of the park by Negroes totally different from those

involving use by white persons. It is clear, we submit, that

no governmental agency can operate a public facility for

the exclusive use of white persons, nor enforce, as to the

park, a condition that if Negroes use it, the park can no

longer remain in the public domain.

A state cannot impose unconstitutional conditions upon

the exercise by a Negro of his constitutional rights.

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637. But

here Negroes are told that a consequence of exercising

their constitutional right to play golf on the Bonnie Brae

Golf Course will be that another part of Revolution Park

will revert to its grantor. This is as effective an enforce

ment of racial distinctions in the use and enjoyment of

public park facilities as those condemned by this Court in

the Dawson and Holmes cases. The protection of the Con

stitution extends to ‘ ‘ sophisticated as well as simple-minded

modes of discrimination.” Lane v. Wilson, 307 IT. S. 268,

9

275. The state here cannot be permitted by this device to

deny these petitioners their right to equal protection ot

the laws where it is clear that restrictions of this char

acter directly imposed by the state could not be sustained.4

It is respectfully submitted that this petition should be

granted to determine whether the state action here involved

and the decision below are violative of principles announced

by this Court in Mayor v. Dawson, supra, and Holmes v.

City of Atlanta, supra.

2. The decision of the court below in sanctioning and

validating the reverter provision in the Barringer deed is

in apparent conflict with the decisions of this Court in

Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, and Barrows v. Jackson, supra.

In Shelley v. Kraemer this Court held that enforcement

by injunction of a racially restrictive covenant, directed

pursuant to the state’s common law policy as formulated

in earlier decisions, denies the equal protection of the laws

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment. In that case, this

Court recognized that the Amendment is not rendered in

effective “ simply because the particular pattern of dis

crimination, which the State has enforced, was defined

initially by the terms of a private agreement,” 334 U. S.

at page 20, and “ that the action of state courts in enforcing

a substantive common-law rule formulated by those courts,

may result in the denial of rights guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment . . S ’ Id, at 17. It concluded “ that

judicial action is not immunized from the operation of the

4 Compare Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, with Buchanan v. Warley,

supra; Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 and Nixon v. Condon,

286 U. S. 73 with Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536; Lane v.

Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 with Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347.

See Richmond v. Deans, supra-, Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387 (CA

4th 1947), cert, denied, 333 U. S. 875; Lawrence v. Hancock,

76 F. Supp. 1004 (S. D. W . Va. 1948) ; Kern v. Newton, 151 Kan.

565, 100 F. 2d 709 (1940).

10

Fourteenth Amendment simply because it is taken pursu

ant to the state’s common law policy.” Id. at 20.

Similarly, in Barrows v. Jackson, this Court held that

a state court’s award of damages for a party’s nonobserv

ance of such a covenant would likewise infringe the Four

teenth Amendment. There the court concluded, “ The

action of a state court at law to sanction the validity of

the restrictive covenant here involved would constitute state

action as surely as it was state action to enforce such cove

nants in equity, as in Shelley, supra.” 5 346 U. S. at 254.

Petitioners submit that the Supreme Court of North

Carolina has misconstrued the rationale of the Shelley and

Barrows cases. In those cases the Court held that the

Fourteenth Amendment precludes a court from sanctioning

a discriminatory agreement either by the enforcement of

the agreement or by the imposition of penalties for breach

thereof. It is precisely this kind of sanction that the North

Carolina courts have given to the reverter provision in the

Barringer deed. Already they have adjudged that it will

cause a reverter of the Barringer tract upon use of the

golf course by Negroes. If the Commission should fail to

5 And, see Harmon v. Tyler, supra, where a Louisiana statute, and

a New Orleans ordinance as well, made it unlawful for any white

person to establish his residence on any property located in a Negro

community without the written consent of a majority of the Negroes

inhabiting the same, or for any Negro to establish his residence on

any property located in a white community without the written

consent of a majority of the white persons inhabiting the community.

These were held unconstitutional on authority of Buchanan v.

Warley, supra. The refusal of a landowner, unassisted by govern

mental authority, to sell or lease to another citizen would not of

itself involve any Fourteenth Amendment implications. The vice

lay in the sanctions— here criminal penalties— supplied by the State

and the city. Cf. Land Development Co. v. New Orleans, 17 F. 2d

1016 (C A Sth 1927), rev’g, 13 F. 2d 898 (E. D. La. 1926).

11

obey the state court judgment by refusing to yield posses

sion to Barringer on the occurrence of this event, ample

judicial sanctions will be available to compel obedience, just

as sanctions would have been available to the plaintiff in

Shelley had the defendant refused to move, and to the plain

tiff in Barrows, if defendant had refused to pay damages

awarded by the state court.6

Moreover, when the basis for the holding of the Supreme

Court of North Carolina is examined, the presence of state

action becomes even more apparent. The State of North

Carolina, as a part of its common law, recognizes the deter

minable fee simple estate and the concomitant possibility

of reverter. Its common law rules also cause an automatic

termination of the grantee’s estate and conversion of the

grantor’s nonpossessory possibility into a possessory estate,

upon the happening of the stated event. These propositions

the Supreme Court of North Carolina stated in its opinion

6 See 1A, Gen. Stats, of North Carolina, No. 1-253,259. The

fact that declaratory judgments are not self-executing does not make

them unique. In almost all actions, whether at equity or at law, a

recalcitrant party can be made to comply with a judgment only by

a new invocation of the judicial process. Borchard, Declaratory

Judgments 22 et seq. (2 ed. 1941). Thus, this case cannot be dis

tinguished from the Shelley and Barrows decisions on the ground

that here a declaratory judgment was sought rather than equitable

relief or legal damages. If the judgment here complained of was

merely an advisory opinion, there might be some basis for a distinc

tion, but the Supreme Court of North Carolina has expressly negated

its power to render advisory opinions under its Declaratory Judg

ments Act. See Lide v. Mears, 231 N. C. I l l , 56 S. E. 2d 404

(1949) ; Tryon v. Duke Power Co., 222 N. C. 200, 22 S. E. 450

(1942) ; Allison v. Sharpe, 209 N. C. 477, 184 S. E. 27 (1936).

12

and applied in the instant case.7 Conformably thereto, it

held that ownership of the disputed property would “ auto

matically” revest in Barringer upon the happening of a

stated event, i. e., the admission of the petitioners to the

golf course. Thus, under the Court’s judgment, Barringer

will be able to exercise the incidents and benefits of owner

ship (although not necessarily of possession) as soon as

petitioners are admitted to the golf course, without the

necessity of invoking further judicial sanctions to execute

the judgment.

As was pointed out in the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S.

3, 17, racial discrimination by individuals escapes the ban

of the Fourteenth Amendment only so long as such dis

crimination is “ unsupported by state authority in the shape

of laws, customs or judicial or executive proceedings” and

that immunity is lost the moment such discrimination is

“ sanctioned in some way by the state. . . . ” The reverter

provision obtains its automatic operation and title-trans

7 In addition to reference to many decisions, the Court spe

cifically stated at 242 N. C. at 320, 321, 88 S. E. 2d at 122, 123:

“ In North Carolina we recognize the validity of a base, qualified

or determinable fee. Hall v. Turner, supra [110 N. C. 292, 14 S. E.

791 (1892)] ; Williams v. Blizzard, 176 N. C. 146, 96 S. E. 957

(1918) ; Turpin v. Jarrett, 226 N. C. 135, 37 S. E. 2d 124 (1946).

* * * *

“ It is a distinct characteristic of a fee determinable upon limi

tation that the estate automatically reverts at once on the occurrence

of the event by which it is limited, by virtue of the limitation in the

written instrument creating such fee, and the entire fee automatically

ceases and determines by its own limitations. Collette v. Town of

Charlotte, supra [114 Vt. 357, 45 A. 2d 203 (1 9 4 6 )]; First

Universalist Society v. Boland, supra [155 Mass. 171, 29 N. E.

524 (1 8 9 2 )]; Brown v. Independent Baptist Church of Woburn,

supra [325 Mass. 645, 91 N. E. 2d 922 (1950)] ; Copenhaver v.

Pendleton, 155 Va. 463, 155 S. E. 802 [1930] ; Tiffany: Law of

Real Property, 3rd Eel., Section 217. No action on the part of the

creator of the estate is required, in such event, to terminate the

estate. 19 Am. Jur., Estates, Section 29.”

13

ferring characteristics from the significance that North

Carolina attaches to the deed limitations. The highest

court in that State has adjudged that, by operation of its

common law rules, there will occur a reverter to Barringer

if Negroes are admitted to the golf course. That such a

judicial declaration of rights and liabilities accorded by

common law rules is state action within the meaning of the

Fourteenth Amendment is abundantly established by the

decisions of this Court. See Shelley v. Kraemer, supra;

Barrows v. Jackson, supra-, American Federation of Labor

v. Swing, 312 U. S. 321; Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S.

296; Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252.

The state action here is indistinguishable from that con

demned by this Court in Barrows v. Jackson as violative

of the Fourteenth Amendment. In the Barrows case, this

Court held that a state court could not award damages for

breach of a restrictive covenant without invading the con

stitutionally protected rights of Negro citizens to acquire

land, even though the granting of damages would have left

the Negro purchaser totally undisturbed in the enjoyment

of his land. The Court stated at page 254:

To compel respondent to respond in damages

would be for the State to punish her for her failure

to perform her covenant to continue to discriminate

against non-Caucasians in the use of her property.

The result of that sanction would be to encourage the

use of restrictive covenants. To that extent, the

State would act to put its sanction behind the

covenants.

This rationale is precisely applicable to the instant case,

for the giving of judicial sanction to the reverter provi

sions operates to penalize the City and Commission for

failure to obey discriminatory provisions in the deed. More

over, the effect of the court sanction is more direct here for

14

it operates to deprive the petitioners of the right to use

public facilities, while in the Barrows case, a damage judg

ment would not have affected the Negro purchaser’s enjoy

ment of his land.

Further, the Court held that failure to give force and

effect to the reverter would violate due process. But an

individual’s right to contract and a property owner’s

right to exercise the incidents of his ownership are each

subordinate to paramount constitutional considerations.

Norman v. Baltimore ■& 0. R. Co., 294 U. S. 240; Home

Building and Loan Association v. Blaisdell, 290 U. S. 398.

From its inception every individually created property

interest is subject to the infirmity that the state cannot

sanction its operation if a violation of constitutionally-

protected rights will follow. Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S.

501; Republic Aviation Corp. v. National Labor Relations

Board, 324 U. S. 793. The state may effectuate property

interests and give operation to contracts so long as those

things may be done consistently with the Constitution. But

the state cannot avoid the prohibitions of the Fourteenth

Amendment by seeking to protect a right that cannot con

stitutionally obtain. The desire of the state to promote

private or public interests must be subordinated to its obli

gation to respect fundamental constitutionally-protected

civil rights. In all cases, the state must square its action

with the overriding mandate of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, regardless of how it squares with other interests.

The right of an individual to make a contract or to own

and dispose of his property does not vest in him the privi

lege of directly or indirectly requiring a governmental

agency to discriminate against its citizens on racial grounds.

Nor does it invest him with power to create a device the

legal operation of which offends the Constitution. As in

Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, the Court said at page 22:

The Constitution confers upon no individual the

right to demand action by the State which results in

15

. the denial of equal protection of the laws to other

individuals. And it would appear beyond question

that the power of the State to create and enforce

property interests must be exercised within the

boundaries defined by the Fourteenth Amendment.

See also Barrows v. Jackson, supra; Hurd v. Hodge, 334

U. S. at 24, 34-35. Indeed this is the ratio decedendi of the

Shelley and Barrows cases. Petitioners submit that review

of this case is necessary if this Court’s decisions in Shelley

and Barrows barring judicial sanction and enforcement of

racially restrictive covenants are not to be sapped of their

vitality.

3. The decision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

in this case conflicts with decisions of other state courts

holding that a state may not indirectly accomplish a denial

of civil rights by sanctioning privately-initiated property

restrictions.

In Liberty Annex Corp. v. Dallas, 289 S. W. 1067 (Tex.

Civ. App. 1927), 19 S. W. 2d 845 (Tex. Civ. App. 1929), it

was held that a municipal ordinance making it a criminal

offense to violate a pre-existing segregation agreement

privately-made between certain whites and Negroes rela

tive to certain property is violative of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Voluntary adherence to the terms of the

agreement would have occasioned no constitutional diffi

culties, but the criminal sanctions supplied by the city made

the difference.

Similarly, in Ex parte Laws, 31 Cal. App. 846, 193 P. 2d

744 (1948), petitioners sought discharge by habeas corpus

from imprisonment for contempt for refusing to obey a

court order to vacate restricted property entered pursuant

to a final judgment enjoining the petitioners from using

or occupying the land in violation of privately-imposed

racial restrictions. The court held that petitioners must be

16

discharged, since the commitments amounted to state action

in indirect enforcement of the restrictions within the pur

view of the decision in Shelley v. Kraemer, supra.

In Claremont Improvement Club v. Buckingham, 89 Cal.

App. 2d 32, 200 P. 2d 47 (1948), a California court of

appeals reversed the judgment of a lower court which had

granted an injunction against the breach of a private

racially restrictive covenant. The appellee contended that

even if Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, prohibited the issuance

of an injunction, its prayer for a declaratory judgment

that the covenant was valid should be sustained. The

appellate court denied this relief also, holding that if the

covenant was unenforceable, the whole purpose of the liti

gation failed.

Similarly, in Woytus v. Winkler, 357 Mo. 1082, 212 S. W.

2d 411 (1948), the court affirmed the dismissal of an action

brought to divest title to real estate and enjoin breach of

a racial restrictive covenant between property owners which

provided against sale of the land to or occupancy thereof by

any Negro. In this case the Negro defendants had been

vested with title and were in possession. The affirmance

was on authority of Shelley v. Kraemer, supra.

And, in Clifton v. Puente, 218 S. W. 272 (Tex. Civ. App.

1949), a deed contained a restriction against sale to persons

of Mexican descent and a provision for reverter in that

event. The property was sold to Puente, a naturalized

American of Mexican descent. In a suit for cancellation

of Puente’s deed, the court sustained his demand for title

and possession against the claim that the restrictive and

reverter provisions constituted a defense thereto. It said:

“ It is as much an enforcement of the covenant to deny to

a person a legal right to which he would be entitled except

for the covenant as it would be to expressly command by

judicial order that the terms of the covenant be recognized

and carried out . . . judicial recognition or enforcement

17

of the racial covenant involved here by a state court is pre

cluded by the ‘ equal protection of the laws’ clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.”

It is respectfully submitted that this petition should be

granted to resolve this conflict in decisions of state courts.

4. The instant case raises questions of great public im

portance which should be determined by this Court. Peti

tioners do not know how many conveyances for public use

with reverter provisions of this character have been made.

One need not be a student of American race relations, how

ever, to realize that the arrangement here involved, reflect

ing as it does local custom, usage and attitudes, cannot be

regarded as an isolated phenomenon. Indeed, such provi

sions are probably attached to many public facilities in use

throughout the United States. This decision places a cloud

upon any public property where the grantor made enforce

ment of racial discrimination a condition of his grant.

The immediate effect of the decision of the North Caro

lina Supreme Court, therefore, goes beyond the narrow

facts of the instant case. Its ramifications promise to be

widespread indeed. For, in the light of this case, the right

of Negroes and other minority groups to use public recrea

tional facilities without discrimination, see Dawson and

Holmes cases, supra, to enjoy nonsegregated public educa

tional facilities, see Brown v. Board of Education, supra;

Bolling v. Sharpe, supra, and to acquire housing though

encumbered by racial covenants, see Shelley v. Kraemer,

supra; Barrows v. Jackson, supra; Hurd v. Hodge, supra,

all become questionable.

This device provides a method for full frustration of

constitutional doctrines evolved in those cases. Racial

restrictive covenants, declared unenforceable by injunction

in Shelley and by an award of damages in Barrows, may

now be enforced by judicial sanction of reverter provisions

18

sustained in this case. Property owners need only provide

that in event the contract is violated, the property shall

revert to render Shelley and Barrows completely mean

ingless.

The decision below poses a gross danger to the strength

and vitality of the Constitution’s proscription against gov

ernmental enforcement of racial distinctions and differen

tiations, and this petition should be granted to resolve this

important public question.

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the reasons hereinabove stated, it is

r e s p e c t fu lly s u b m itte d that this petition for writ of cer

tiorari should be granted.

R obert L. Carter,

T htjrgood M arshall ,

S pottswood W. R obinson , III,

T. H . W y c h e ,

Counsel for Petitioner.

E lwood H. C h iso lm ,

W illiam L. T aylor,

Of counsel.

19

APPENDIX A

Opinion of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

entered June 30, 1955

Appeal by all the defendants, except Osmond L. Bar

ringer, Abbott Realty Company and the city of Charlotte,

from Patton, Special Judge, Extra February Civil Term

1955 of Mecklenburg.

Civil action to have determined questions of the con

struction or validity of provisions in certain deeds restrain

ing the use of the lands conveyed, and requiring that the

lands revert to the grantors if such restrictions are not

carried out.

All parties to the action, by written stipulation filed with

the court, waived a jury trial, and consented that the court

find the facts. The facts found by the Judge necessary for

a decision of the questions presented are summarized as

follows:

One. Charlotte is a municipal corporation of the State

of North Carolina. General control, management and au

thority over the parks and playgrounds of Charlotte are

vested by law in the plaintiff, a public body corporate

known as Charlotte Park and Recreation Commission.

Two. On 31 August 1927 W. T. Shore and T. C. Wilson,

and the defendants Barringer and Abbott Realty Com

pany, offered to give to the city of Charlotte through plain

tiff for park and playground purposes certain lands free

from encumbrance upon the following conditions:

1. “ Said lands are to be used by the city of Charlotte

through its Park and Recreation Commission for white

people’s parks and playgrounds, parkways and municipal

golf courses only.”

20

2. Provisions that the lands shall be beautified and

maintained so as to keep them suitable for parks, etc., at

a cost of not less than $5,000.00 annually for the first 8

years.

3. Provisions for construction of driveways.

4. Adjacent lands now owned by city of Charlotte shall

be set aside by it as a part of this proposed park.

5. In the event the lands are not kept and maintained

at an expenditure as aforesaid and are not used for parks

and playgrounds only, the “ said lands shall revert in fee

simple to the undersigned donors” ; each donor to have

reverted back to him the land he gave.

Three. On 18 February 1929 plaintiff approved said

offer. On 21 February 1929 the city of Charlotte accepted

said offer, and agreed to the terms thereof by ordinance

duly passed and adopted.

Four: On 22 May 1929 the defendant Barringer, and

wife, by deed properly recorded, conveyed as a gift certain

lands therein described to plaintiff for use as a park, play

ground and recreational system of the city of Charlotte to

be known as Revolution Park. This deed in the granting

clause conveys the land to the plaintiff here “ upon the

terms and conditions, and for the uses and purposes, as

hereinafter fully set forth.” The habendum clause is to

have and to hold the land “ upon the following terms and

conditions, and for the following uses and purposes, and

none other, ’ ’ which are set forth as follows: 1. The land

conveyed by this deed, together with other lands conveyed

to plaintiff by W. T. Shore, and wife, T. C. Wilson, and

wife, Abbott Realty Co. and the city of Charlotte shall be

maintained and operated by plaintiff as an integral part

of a park, playground and recreational area, to be known

as Revolution Park, “ for use of, and to be used and enjoyed

Appendix A

21

by persons of the white race only.” 2. Here follows the

other conditions of the offer. Then the deed contains this

language:

“ In the event that the said lands comprising the

said Revolution Park area as aforesaid, being all of

the lands hereinbefore referred to, shall not be kept

and maintained as a park, playground and/or rec

reational area, at an average expenditure of five

thousand dollars ($5,000) per year, for the eight-

year period as aforesaid, and/or in the event that

the said lands and all of them shall not be kept, used

and maintained for park, playground and/or recrea

tional purposes, for use by the white race only, and

if such disuse or non-maintenance continue for any

period as long as one year, and/or should the party

of the second part, or its successors, fail to construct

or have constructed the roadway above referred to,

within the time specified above, then and in either

one or more of said events, the lands hereby con

veyed shall revert in fee simple to the said Osmond

L. Barringer, his heirs or assigns; provided, how

ever, that before said lands, in any such event, shall

revert to the said Osmond L. Barringer and as a

condition precedent to the reversion of the said

lands in any such event, the said Osmond L. Bar

ringer, his heirs or assigns, shall pay unto the party

of the second part or its successors the sum of

thirty-five hundred dollars ($3500).”

Five. On 22 May 1929 W. T. Shore, and wife, T. C.

Wilson, and wife, by deed properly recorded, conveyed as

a gift certain lands therein described to plaintiff upon the

terms and conditions and for the same uses and purposes

as set forth in the defendant Barringer’s deed. The provi

sions in this deed as to the use of the land, and the lan

Appendix A

22

guage as to reversion to the donors, are similar to the

Barringer deed, except there is no provision that as a

condition precedent to a reversion the grantors shall pay

any money to the grantee. A number of years later a con

troversy arose between W. T. Shore and T. 0. Wilson on

the one side and the plaintiff here on the other over this

land they conveyed as a gift. Action was instituted by

W. T. Shore and T. C. Wilson against the plaintiff here,

which action was compromised and settled by the plaintiff

here, the defendant in that case, paying to W. T. Shore

$3,600 for all rights of reversion, forfeiture, re-entry and

interest which Shore had, has, or might have in the lands

he conveyed by gift, and paying to the heirs of Wilson

$2,400 for the same rights. As a part of the compromise

and settlement, W. T. Shore and the heirs of Wilson, by

separate deeds, remised, released and forever quit-claimed

unto the plaintiff here all rights of reversion, forfeiture,

entry, re-entry, title, interest, equity and estate, and all

other rights of every nature, kind and character, which

they had, now have, or might have hereafter in the said

lands.

Six. On 22 May 1929 Abbott Realty Company, by deed

properly recorded, conveyed as a gift certain lands there

in described to plaintiff upon the terms and conditions and

for the same uses and purposes, and for use of the white

race only, as set forth in the defendant Barringer’s deed.

This deed contains a reverter provision, but it does not

provide that if the lands conveyed are used by members

of a non-white race that the lands conveyed as a gift shall

revert back to the grantor. Nor does it contain a provision

that as a condition precedent to reversion Abbott Realty

Company shall pay to the grantee any money.

Seven. On 22 May 1929 the city of Charlotte conveyed

to plaintiff certain adjacent lands owned by it to form a

Appendix A

23

part of Revolution Park. This park is composed of this

land and the lands conveyed to Barringer, Shore, Wilson

and Abbott Realty Company. The city’s deed provides

that should the lands conveyed by it and the lands con

veyed by the other parties named above shall not at any

time for 12 consecutive months be used for park, play

ground or recreational purposes for use by persons of the

white race only, then the land conveyed by the city shall

cease to be a park, playground, etc., and shall revert to the

city of Charlotte.

Eight. Plaintiff has in Revolution Park a municipal

swimming pool, municipal tennis courts and the Bonnie

Brae Golf Course, which it operates and maintains as a

part of the recreational system of Charlotte. Bonnie Brae

Golf Course is situated on the lands given to plaintiff by

Shore and Wilson, and conveyed to plaintiff by the city of

Charlotte. This golf course is the only one operated and

maintained by plaintiff, and it and the other recreational

features of Revolution Park are operated by plaintiff for

the exclusive use of members of the white race. All Negroes

are denied the use of this golf course because of the re

strictions in the above deeds.

Nine. In December 1951 all the defendants, except Bar

ringer, Abbott Realty Company and the city of Charlotte

presented to plaintiff a petition stating1 that they are Ne

groes, and because they are Negroes, they have been denied

the right to use this golf course, in violation of their con

stitutional rights, and demanding that they be permitted

to use this golf course.

Ten. Plaintiff by operation of law is charged with the

duty of operating and maintaining recreational facilities

for the citizens of Charlotte, and does not desire to deprive

any of its citizens of their legal rights, nor does plaintiff

Appendix A

24

desire to lose by reverter any of the properties entrusted

to it for recreational purposes, nor does it desire to fail to

comply with the terms of any gifts made to it by any of its

citizens. Therefore, by reason of the aforesaid petition the

plaintiff immediately instituted suit against the grantors

of the lands composing Revolution Park to obtain a judicial

determination of the effect of allowing Negroes to use the

golf course in said park, because of the reverter provisions

and the restrictions as to use in their deeds. The appel

lants were made parties to the suit. Pending a final deci

sion in such suit plaintiff refused petitioner’s request.

Eleven. The defendant Barringer is ready, able and

willing to pay the sum of $3,500 as a condition precedent

to the reversion of the land to him as provided in his deed

of gift to the plaintiff.

Upon these facts found the judge made following con

clusions of law and entered judgment accordingly:

1. The court has jurisdiction of the property and the

parties, and is empowered to enter judgment under the

Declaratory Judgment Act. G. S. N. C. 1-253 et seq.

2. The deeds from Osmond L. Barringer, and wife,

and from Abbott Realty Company vested in plaintiff a

valid determinable fee with the possibility of reverter in

and to the lands described in the deeds.

3. In the event any of the reverter provisions in the

Barringer deed or the Abbott Realty Company deed be

violated, then and in such event title to the lands conveyed

in said deeds will by operation of law immediately revert

title in the grantors: and the admission of Negroes on the

Bonnie Brae Golf Course to play golf will cause the re

verter provisions in said deeds immediately to become

operative, and title to revert.

Appendix A

25

4. The deed from the city of Charlotte vested in plain

tiff a valid determinable fee with the possibility of reverter.

That the use of Bonnie Brae Golf Course by negroes as

players would not cause a reversion of the property con

veyed by the city of Charlotte to plaintiff, for that the

reversionary clause in the city’s deed is, under such cir

cumstances, void as being in violation of the 14th Amend

ment to the U. S. Constitution.

5. The plaintiff is the owner in fee, free of any condi

tions, reservations or reverter provisions of the lands con

veyed to it by Shore and Wilson.

6. Revolution Park was created as an integral area of

land, and to permit negroes to play golf on any part of said

land will cause the reverter provisions in the Barringer

and Abbott Realty Company deeds immediately to become

effective and result in the title of plaintiff terminating and

the lands reverting to Barringer and Abbott Realty Com

pany.

From the judgment entered the defendants, except Os

mond L. Barringer, Abbott Realty Company and the city

of Charlotte, appealed, assigning error.

T. H. Wyche and Spottswood W. Robinson, III, for

Charles W. Beeper, I. P. Farrar, Sadler S. Gladden, Robert

H. Greene, James Heath, Henry M. Isley, Russell Mc

Laughlin, Anthony M. Walker, Harold Walker, Edward

J. Weddington, James J. Weddington, Willie Lee Wedding-

ton, L. A. Warner, G. M. Wilkins, Roy S. Wynn, and

Rudolph M. Wyche, Defendants, Appellants.

Cochran, MeCleneghan & Miller and F. A. MeCleneghan

and Lelia M. Alexander for Osmond L. Barringer, Defend

ant, Appellee.

John D. Shaw for Charlotte Park and Recreation Com

mission, Plaintiff, Appellee.

Appendix A

26

Appendix A

P arker , J.

The decision of the Trial Judge that he had jurisdiction

of the property and the parties, and was empowered to

enter judgment under the Declaratory Judgment Act is

correct. G. S. 1-253 et seq., Lide v. Mears, 231 N. C. I l l ,

56 8. E. 2d 404.

There are no exceptions to the Judge’s findings of fact.

We shall discuss first the Barringer Deed, which by

reference, as well as all the other deeds mentioned in the

statement of facts, is incorporated in the findings of fact,

and made a part thereof. The first question presented is:

Does the Barringer Deed create a fee determinable on

special limitations, as decided by the Trial Judge!

This Court said in Hall v. Turner, 110 N. C. 292, 14 S. E.

791: “ Whenever a fee is so qualified as to be made to

determine, or liable to be defeated, upon the happening of

some contingent event or act, the fee is said to be base,

qualified or determinable.”

“ An estate in fee simple determinable, sometimes re

ferred to as a base or a qualified fee, is created by any

limitation which, in an otherwise effective conveyance of

land, creates an estate in fee simple and provides that the

estate shall automatically expire upon the occurrence of a

stated event. . . . No set formula is necessary for the crea

tion of the limitation, any words expressive of the grantor’s

intent that the estate shall terminate on the occurrence of

the event being sufficient. . . . So, when land is granted for

certain purposes, as for a schoolhouse, a church, a public

building, or the like, and it is evidently the grantor’s inten

tion that it shall be used for such purposes only, and that,

on the cessation of such use, the estate shall end, without

any re-entry by the grantor, an estate of the kind now under

consideration is created. It is necessary, it has been said,

that the event named as terminating the estate be such that

it may by possibility never happen at all, since it is an

27

essential characteristic of a fee that it may possibly endure

forever.” Tiffany: Law of Eeal Property, 3rd Ed., Sec.

220.

In Connecticut Junior Republic Association v. Litch

field, 119 Conn. 106, 174 A. 304, 95 A. L. R. 56, the real

estate was devised by Mary T. Buell to the George Junior

Republic Association of New York with a precatory provi

sion that it be used as a home for children. The New York

association by deed conveyed this land to plaintiff, “ its

successors and assigns, in trust, as long as it may obey the

purposes expressed in . . . the will . . . and as long as the

(grantee) shall continue its existence for the uses and

purposes as outlined in the preamble of the constitution of

the National Association of Junior Republics, but if at

any time it shall fail to so use said property for said pur

poses . . . then the property hereby conveyed shall revert

to this grantor, or its successors.” The Supreme Court of

Connecticut said: “ The effect of the deed was to vest in

the plaintiff a determinable fee. Here, as in First Univer-

salist Society v. Boland, 155 Mass. 171, 174, 29 N. E. 524,

15 L. R. A. 231, the terms of the deed ‘ do not grant an

absolute fee, nor an estate or condition, but an estate which

is to continue till the happening of a certain event, and

then to cease. That event may happen at any time, or it

may never happen. Because the estate may last forever,

it is a fee. Because it may end on the happening of the

event it is what is usually called a determinable or qualified

fee.’ See, also, City National Bank v. Bridgeport, 109

Conn. 529, 540, 147 A. 181; Battistone v. Banulski, 110

Conn. 267, 147 A. 820.”

In First Universalist Society v. Boland, 155 Mass. 171,

29 N. E. 524,15 L. R. A. 231, “ the grant of the plaintiff was

to have and to hold, etc., ‘ so long as said real estate shall

by said society or its assigns be devoted to the uses, inter

ests and support of those doctrines of the Christian re-

Appendix A

28

ligion’ as specified; ‘ and when said real estate shall by said

society or its assigns be diverted from the uses, interests,

and support aforesaid to any other interests, uses, or pur

poses than as aforesaid, then the title of said society or its

assigns in the same shall forever cease, and be forever

vested in the following named persons, etc.’ ” The Su

preme Court of Connecticut in Connecticut Junior Republic

Association v. Litchfield, supra, has quoted the language

of this case holding that the grant creates ‘ ‘ a determinable

or qualified fee.” Immediately after the quoted words, the

Massachusetts Court used this language: “ The grant was

not upon a condition subsequent, and no re-entry would be

necessary; but by the terms of the grant the estate was to

continue so long as the real estate should be devoted to the

specified uses, and when it should no longer be so devoted

then the estate would cease and determine by its own limi

tation. ’ ’

In Brown v. Independent Baptist Church of Woburn,

325 Mass. 645, 91 N. E. 2d 922, the will of Sarah Converse

devised land “ to the Independent Baptist Church of W o

burn, to be holden and enjoyed by them so long as they

shall maintain and promulgate their present religious belief

and faith and shall continue a church; and if the said

church shall be dissolved, or if its religious sentiments

shall be changed or abandoned, then my will is that this

real estate shall go to my legatees hereinafter named.”

The Court said: “ The parties apparently are in agree

ment, and the single justice ruled, that the estate of the

church in the land was a determinable fee. We concur.

(Citing authorities.) The estate was a fee, since it might

last forever, but it was not an absolute fee, since it might

(and did) ‘ automatically expire upon the occurrence of a

stated event.’ ”

In Smith v. School Dist. No. 6 of Jefferson County

(Missouri), 250 S. W. 2d 795, the deed contained this pro-

Appendix A

29

vision: “ The said land being hereby conveyed to said

school district for the sole and express use and purpose of

and for a schoolhouse site and it is hereby expressly under

stood that whenever said land shall cease to be used and

occupied as a site for a schoolhouse and for public school

purposes that then this conveyance shall be deemed and

considered as forfeited and the said land shall revert to

said party of the first part, his heirs and assigns.” The

Court held that the estate conveyed was a fee simple

determinable.

In Collette v. Town of Charlotte, 114 Vt. 357, 45 A. 2d

203, the deed provided that the land “ was to be used by said

town for school purposes, but when said town fails to use

it for said school purposes it shall revert to said Schofield”

(the grantor), “ his heirs and assigns, but the town shall

have the right to remove all buildings located thereon. The

town shall not have the right to use the premises for other

than school purposes.” The Supreme Court of Vermont in a

well reasoned opinion supported by ample citation of au

thority said: “ It was held in Fall Creek School Twp. v. Shu

man, 55 Ind. App. 232, 236,103 N. E. 677, 678, that a convey

ance of land ‘ to be used for school purposes’ without further

qualification, created a condition subsequent. The same

words were used in Scofield’s deed to the Town of Char

lotte, but they were followed by the provision that ‘when

said Town fails to use it for said school purposes it shall

revert to said Scofield, his heirs or assigns,’ clearly indi

cating the intent of the parties to create a determinable

fee, which was, we think, the effect of the deed. North v.

Graham, 235 111. 178, 85 N. E. 267, 18 L. R. A., N. S., 624,

626, 126 Am. St. Rep. 189.”

In Mountain City Missionary Baptist Church v. Wag

ner, 193 Tenn. 625, 249 S. W. 2d 875, the deed is an ordi

nary deed conveying certain real estate. After the haben

dum clause there appears the following language: “ But

Appendix A

30

it is distinctly understood that if said property shall cease

to be used by the said Missionary Baptist Church (for any

reasonable period of time) as a place of worship, that said

property shall revert back to the said M. M. Wagner and

his heirs free from any encumbrances whatsoever and this

conveyance become null and void. ’ ’ The g’rantor was M. M.

Wagner. The Court said: “ When we thus read the deed,

as a whole, we find that the unmistakable and clear inten

tion of the grantor was to give this property to the church

so long as it was used for church purposes and then when

not so used the property was to revert to the grantor or

his heirs. The estate thus created in this deed is a deter

minable fee.”

In Magness v. Kerr, 121 Ore. 373, 254 Pac. 1012, 51

A. L. R. 1466, the deed contained the following provision,

to-wit: “ Provided and this deed is made upon this condi

tion, that should said premises at any time cease to be used

for cooperative purposes, they shall, upon the refunding

of the purchase price and reasonable and equitable ar

rangement as to the disposition of the improvements, re

vert to said grantors.” The Court held that this was a

grant upon express limitation, and the estate will cease

upon breach of the condition without any act of the grantor.

For other cases of a determinable fee created under

substantially similar language see: Doff'elt v. Decatur

School District No. 17, 212 Ark. 743, 208 S. W. 2d 1; Regular

Predestinarian Baptist Church of Pleasant Grove v. Park

er, 373 111. 607, 27 N. E. 2d 522, 137 A. L. R. 635; Board of

Education for Jefferson County v. Littrell, 173 Ky. 78, 190

S. W. 465; Pennsylvania Horticultural Society v. Craig,

240 Pa. 137, 87 A. 678.

We have held in Ange v. Ange, 235 N. C. 506, 71 S. E.

2d 19, that the words “ for church purposes only” appear

ing at the conclusion of the habendum clause, where there

Appendix A

31

is no language in the deed providing for a reversion or for

feiture in event the land ceases to be used as church prop

erty, does not limit the estate granted. To the same effect:

Shaw University v. Ins. Co., 230 N. C. 526, 53 S. E. 2d 656.

In Abel v. Girard Trust Co., 365 Pa. 34, 73 A. 2d 682,

there was in the habendum clause of the deed a provision

for exclusive use as a public park for the use and benefit

of the inhabitants of the Borough of Bangor. The Supreme

Court of Pennsylvania said: “ An examination of the deed

discloses that there is no express provision for a reversion

or forfeiture. The mere expression of purpose will not

debase a fee.” To the same effect see: Miller v. Village

of Brookville, 152 Ohio St. 217, 89 N. E. 2d 85, 15 A. L. R.

2d 967; Ashuelot Nat. Bank v. Keene, 74 N. H. 148, 65 A.

826, 9 L. R. A. (NS) 758.

In North Carolina we recognize the validity of a base,

qualified or determinable fee. Hall v. Turner, supra;

Williams v. Blizzard, 176 N. C. 146, 96 S. E. 957; Turpin

v. Jarrett, 226 N. C. 135, 37 S. E. 2d 124. See also:

19 N. C. L. R. pp. 334-344: in this article a helpful form is

suggested to create a fee determinable upon special limi

tation.

When limitations are relied on to debase a fee they

must be created by deed, will, or by some instrument in

writing in express terms. Abel v. Girard Trust Co., supra;

19 Am. Jur., Estates, Section 32.

In the Barringer Deed in the granting clause the land is

conveyed to plaintiff “ upon the terms and conditions, and

for the uses and purposes, as hereinafter fully set forth.”

The habendum clause reads, “ to have and to hold the

aforesaid tract or parcel of land . . . upon the following

terms and conditions, and for the following uses and pur

poses, and none other, to-wit. . . . The lands hereby con

veyed, together with the other tracts of land above referred

to (the Shore, Wilson and City of Charlotte lands) “ as

Appendix A

32

forming Revolution Park, shall be held, used and main

tained by the party of the second part” (the plaintiff

here, “ . . . as an integral part of a park, playground and

recreational area, to be known as Revolution Park and

to be composed of the land hereby conveyed and of the

other tracts of land referred to above, said park and/or

recreational area to be kept and maintained for the use

of, and to be used and enjoyed by persons of the white race

only.” The other terms and conditions as to the use and

maintenance, etc., of the land conveyed are omitted as not

material. The pertinent part of the reverter provision of

the deed reads: “ In the event that the said lands com

prising the said Revolution Park area as aforesaid, being

all of the lands hereinbefore referred to . . . and/or in

the event that the said lands and all of them shall not be

kept, used and maintained for park, playground and/or

recreational purposes, for use by the white race only . . .

then, and in either one or more of said events, the lands

hereby conveyed shall revert in fee simple to the said

Osmond L. Barringer, his heirs and assigns,” provided,

however, that before said lands shall revert to Barringer,

and as a condition precedent to the reversion, Barringer,

his heirs or assigns, shall pay unto plaintiff or its suc

cessors $3,500.00.

Barringer by clear and express words in his deed lim

ited in the granting clause and in the habendum clause the

estate granted, and in express language provided for a

reverter of the estate granted by him, to him or his heirs,

in the event of a breach of the expressed limitations. It

seems plain that his intention, as expressed in his deed,

was that plaintiff should have the land as long as it was

not used in breach of the limitations of the grant, and, if

such limitations, or any of them, were broken, the estate

should automatically revert to the grantor by virtue of

Appendix A

33

the limitations of the deed. In our opinion, Barringer

conveyed to plaintiff a fee determinable upon special limi

tations.

It is a distinct characteristic of a fee determinable upon

limitation that the estate automatically reverts at once

on the occurrence of the event by which it is limited, by

virtue of the limitation in the written instrument creating

such fee, and the entire fee automatically ceases and de

termines by its own limitations. Collette v. Town of Char

lotte, supra; First Universalist Society v. Boland, supra;

Brown v. Independent Baptist Church of Woburn, supra ;

Copenhaver v. Pendleton, 155 Va. 463, 155 S. E. 802, 77

A. L. R. 324; Tiffany: Law of Real Property, 3rd Ed., Sec

tion 217. No action on the part of the creator of the

estate is required, in such event, to terminate the estate.

19 Am. Jur., Estates, Section 29.

According to the deed of gift “ Osmond L. Barringer,

his heirs and assigns” have a possibility of reverter in the

determinable fee he conveyed to plaintiff. It has been

held that such possibility of reverter is not void for re

moteness, and does not violate the rule against perpetuities.

19 Am. Jur., Estates, Section 31; Tiffany: Law of Real

Property, 3rd Ed., Section 314.

The land was Barringer’s, and no rights of creditors

being involved, and the gift not being induced by fraud or

undue influence, he had the right to give it away if he chose,

and to convey to plaintiff by deed a fee determinable upon

valid limitations, and by such limitations provide that his

bounty shall be enjoyed only by those whom he intended to

enjoy it. 24 Am. Jur., (lifts, p. 731; Devlin: The Law of

Real Property and Deeds, 3rd Ed., Section 838; 38 C. J. S.,

Gifts, p. 816. In Grossman v. Greenstein, 161 Md. 71, 155

A. 190, the Court said: “ A donor may limit a gift to a

particular purpose, and render it so conditioned and de

pendent upon an expected state of facts that, failing that

Appendix A

Appendix A

state of facts, the gift should fail with it.” The 15th head-

note in Brahmey v. Rollins, (N. H.) 179 A. 186, reads:

“ Right to alienate is an inherent element of ownership of

property which donor may withhold in gift of property.”

We know of no law that prohibits a white man from con

veying a fee determinable upon the limitation that it shall

not be used by members of any race except his own, nor of

any law that prohibits a negro from conveying* a fee deter

minable upon the limitation that it shall not be used by

members of any race, except his own.

If negroes use the Bonnie Brae Golf Course, the deter

minable fee conveyed to plaintiff by Barringer, and his

wife, automatically will cease and terminate by its own

limitation expressed in the deed, and the estate granted

automatically will revert to Barringer, by virtue of the

limitation in the deed, provided he complies with the con

dition precedent by paying to plaintiff $3,500.00, as pro

vided in the deed. The operation of this reversion provi

sion is not by any judicial enforcement by the State Courts

of North Carolina, and Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 92

L. Ed. 1161, has no application. We do not see how any

rights of appellants under the 14th Amendment to the

U. S. Constitution, Section 1, or any rights secured to them

by Title 42 U. S. Code, Sections 1981 and 1983, are violated.

If negroes use Bonnie Brae Golf Course, to hold that

the fee does not revert back to Barringer by virtue of the

limitation in the deed would be to deprive him of his prop

erty without adequate compensation and due process in

violation of the rights guaranteed to him by the 5th Amend

ment to the U. S. Constitution and by Art. 1, Sec. 17 of

the N. C. Constitution, and to rewrite his deed by judicial

fiat.

The appellants’ assignment of error No. 1 to the

conclusion of law of the court that the Barringer deed

vested a valid determinable fee in plaintiff with the pos

35

sibility of a reverter, and assignments of error No. 3 and

No. 4 to the conclusion of the court that in the event any of

the limitations in the Barringer deed are violated, title to

the land will immediately revert to Barringer and that the

use of Bonnie Brae Golf Course by negroes will cause a

reverter of the Barringer deed, are overruled.

The case of Bernard v. Bowen, 214 N. C. 121, 198 S. E.

584, is distinguishable. For instance, there is no limita

tion of the estate conveyed in the granting clause.

Now as to the Abbott Realty Company deed. This deed

conveyed as a gift certain lands to plaintiff upon the same

terms and conditions, and for the same uses and purposes,

and for the white race only, as set forth in the Barringer

deed. This deed contains a reverter provision, if there is

a violation of certain limitations of the estate conveyed, but

the reverter provision does not provide that, if the lands

of Revolution Park are used by members of a non-white

race, the lands conveyed by Abbott Realty Company to

plaintiff shall revert to the grantor. In our opinion, the

estate conveyed by Abbott Realty Company to plaintiff is

a fee determinable upon certain expressed limitations set

forth in the deed, with a possibility of reverter to Abbott

Realty Company if the limitations expressed in the deed

are violated and the reverter provision states that such

violations will cause a reverter. That was the conclusion

of law of the Trial Judge, and the appellants’ assignment

of error No. 2 thereto is overruled. However, the reverter

provision does not require a reverter to Abbott Realty

Company, if the lands of Revolution Park are used by

negroes. Therefore, if negroes use Bonnie Brae Golf

Course, title to the lands conveyed by Abbott Realty Com

pany to plaintiff will not revert to the grantor. See:

Tucker v. Smith, 199 N. C. 502, 154 S. E. 826.

The Trial Judge concluded as a matter of law that if

any of the reverter provisions in the Abbott Realty Com

Appendix A

3 6

pany deed were violated, title would revert to Abbott

Realty Company, and that if negroes use Bonnie Brae Golf

Course, title to the land granted by Abbott Realty Com

pany will revert to it. The appellants’ assignments of

error Nos. 5 and 6 are to this conclusion of law. These

assignments of error are sustained to this part of the con

clusion, that if negroes use Bonnie Brae Golf Course, title

to the land will revert to Abbott Realty Company: and

as to the other part of the conclusion the assignments of

error are overruled.

The appellants’ assignment of error No. 7 is to this