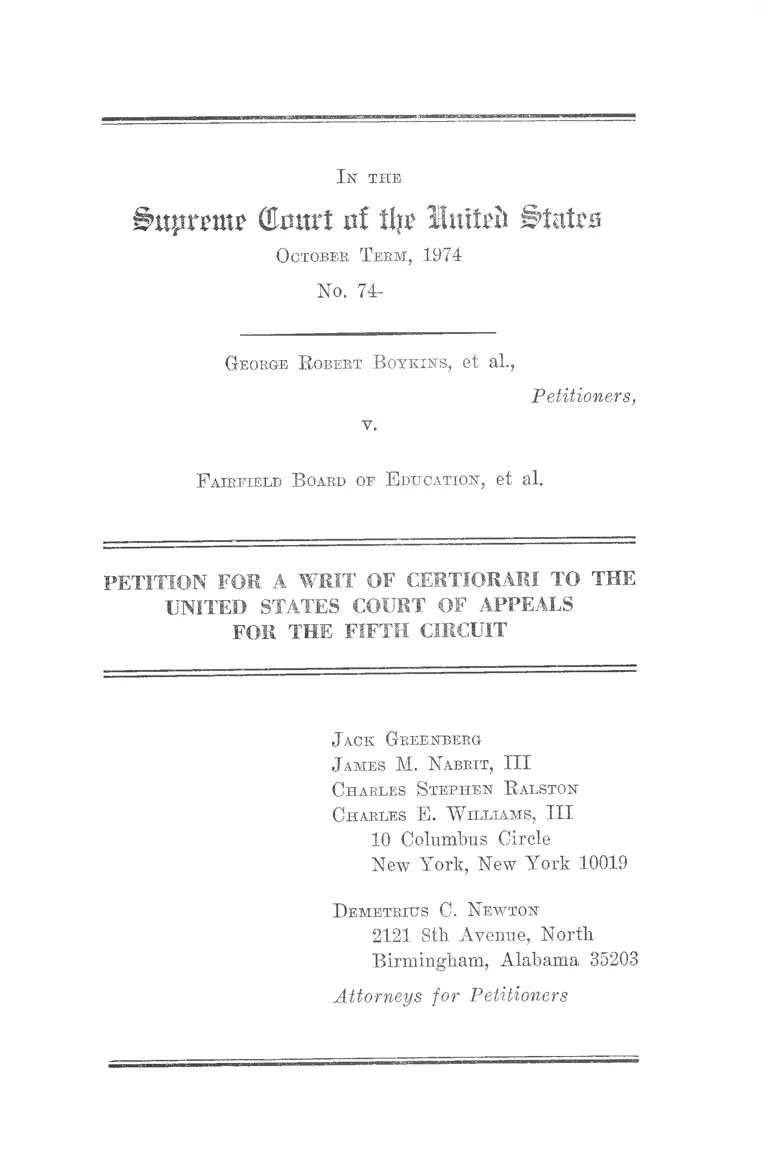

Boykins v. Fairfield Board of Education Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boykins v. Fairfield Board of Education Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1974. c0d59290-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8b4127d5-bd40-4807-b919-63c95b95293d/boykins-v-fairfield-board-of-education-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

SkiptcitiT (Emtrt ni W\t Untfrii States

O ctober T e e m , 1974

No. 74-

G eorge E gbert B o t k in s , e t a l.,

v.

Petitioners,

F a irfield B oard oe E d u cation , e t a l.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

J ack G reen berg

J am es M. N abrit , III

C harles S t e p h e n R alston

C h a rles E. W il l ia m s , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

D e m e t r iu s C. N ew to n

2121 8th Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Petitioners

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinion Below................................................................ 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................... 1

Question Presented ................................ ......................... 1

Constitutional Provision Involved ..... 2

Statement ............................................................ —....... 2

Reasons Why The Writ Should Be Granted ............. 9

Certiorari Should Be Granted Because the Issue

of the Due Process Rights of Public School Pupils

in Disciplinary Hearings Is of National Impor

tance and Because the Decision of the Fifth Circuit

Conflicts With Those of This Court and Other

Federal Courts ............................ 9

A. The Question of the Requirements of Due Pro

cess in School Disciplinary Proceedings Is of

Great National Importance ............................ 9

B. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Resolve the

Conflict Between Decisions of This Court and

the Decision Below ..................................... 12

C. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Resolve the

Conflict Between the Decision Below and Deci

sions of Another Circuit and of District Courts

in Other Circuits ............................................. 15

C o n c l u s io n ................................................. ................... 16

A p p e n d ix

11

T able oe A ttthobities

p a g e

Cases:

Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535 (1971) ..... ...................... 14

Betts v. Bd. of Ed. of City of Chicago, 486 F.2d 629

(7th Cir. 1972) ................. ....................................... . io

Bishop v. Colaw, 450 F.2d 1069 (8th Cir. 1971) .......... 10

Black Coalition v. Portland School District No. 1, 484

F.2d 1040 (9th Cir. 1973) ........ ............. .................... 15

Board of School Commissioners v. Jacobs, No. 73-1347

(cert, granted, June 3, 1974) ...... .................. ......... 12

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed., 399 F.2d 11 (5th Cir.

1968) .......................................................................... 2

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed., 421 F.2d 1330 (5th Cir.

1970) ............ .......... ........................................... 3

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed., 429 F.2d 1234 (5th Cir.

1970) ........... .... ................. ....................................... . 3

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed., 446 F.2d 973 (5th Cir.

1971) ......... ................... ....................................... 3

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed., 457 F.2d 1091 (5th Cir.

1972) ............................... .......... ......... .................... . 3

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) __ 10

DeJesus v. Penberthy, 344 F. Supp. 70 (D. Conn. 1972) 15

Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F.2d

150 (5th Cir. 1961) ...... ................................... .......4, 5, 9

Gagnon v. Scarpelli, 411 U.S. 778 (1973) ..................... 14

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970) .... ................13,14

Goss v. Lopez, No. 73-898 (proh. juris, noted, Feb. 19,

1974) ............... ............................. ..... .............. .......... 12

Hawkins v. Coleman-----F. Supp. ------ (Civ. Action

No. 3-5774-B, June 5, 1974) 11

I l l

PAGE

In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967) ........... ........................... 13

Karp v. Beckeu, 477 F.2d 171 (9th Cir. 1973) .............. 10

Madera v. Bd of Ed. of City of New York, 386 F.2d

778 (2nd Cir. 1967) ........................................... ........ 10

Mills v. Board of Ed. of District of Columbia, 348 F.

Supp. 866 (D.D.C. 1972) ........................................ . 15

Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471 (1972) .................. 13

People v. Overton, 201 N.Y.2d 360, 283 N.Y.S.2d 22, 229

N.E.2d 596 (1967), vacated and remanded, 393 U.S.

85 (1968), reinstated, 24 N.Y.2d 523, 301 N.Y.S.2d

479, 249 N.E.2d 366 (1966) ________ ____ ______ 10

Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School Disk, 393

U.S. 503 (1969) .......................................... - ............ 10

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Ed., 372 F.2d

836 (5th Cir. 1966), aff’d en banc, 380 F.2d 385 ...... 2

Wave v. Estes, 328 F. Supp. 657 (N.D. Tex. 1971), aff’d,

458 F.2d 1360 (5th Cir. 1972) ................. ................. 10

Wolff v. McDonnell, ----- U.S. ----- , 42 U.S.L. Week

5191 (1974) .................- ........................ ................... 14

Wood v. Strickland, No. 73-1285 (cert, granted, April

15, 1974) ................................. ..................... .............. 12

Statute:

Code of Alabama, Title 52, §§ 579 and 598 ............... . 14

Other Authorities:

Bell, Race and School Suspensions in Dallas, 62 Inte

grated Education 66 (March-April 1973) _______ 10

XV

PAGE

Clarke, Race and Suspensions in New Orleans, 63 Inte

grated Education 30 (May-June, 1973) ........... ........ 11

Developments in the Law: Academic Freedom, 81

H arvard L aw R ev iew 1045, (1968) ............................ 10

Goldstein, Reflections on Developing Trends in the Law

of Student Rights, 118 U. P a. L. R ev . 612 (1970) .... 10

Goldstein, The Scope and Sources of School Board

Authority to Regulate Student Conduct and Status:

A Nonconstitutional Analysis, 117 U. P a. L. Rev. 373

(1969) ................. ........................................ ........... ...... 11

Hudgins, Discipline of Secondary School Students and

Procedural Due Process: A Standard, 7 Wake

Forest L. Rev. 32 (1970) ............... .......................... 11

The Student Pushout, Victim of Continued Resistance

To Desegregation (Southern Regional Council and

Robert F. Kennedy Memorial, 1973) ........................ 11

Wright, The Constitution on Campus, 22 V and . L. R ev .

1027 (1969) .............................................. ............. ...... 10

Wright, The New Word Is “Pushout”, 4 Race Relations

Reporter 8 (May 1973) .............................................. 10

I n- t h e

0 H!Jr«!i£ GImtrt of tip United States

O ctober T e r m , 1974

No. 74-

G-eorge E gbert B o y k in s , et a l.,

v.

Petitioners,

F a ir field B oard of E dit cation , e t al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is reported at

492 F.2d 697 and is reprinted in the Appendix to this

Petition, pp. la-17a. The opinions and orders of the dis

trict court are unreported and are reprinted in the Ap

pendix at pp. 18a-26a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

April 12, 1974. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Question Presented

Following a disturbance at a recently desegregated pub

lic high school twenty-one students were suspended and

2

faced expulsion. At a hearing before the school board,

hearsay, in the form of written statements, was introduced

and relied upon by the board. Eight of the twenty-one were

permanently expelled, although a number were shown to

have done no more than others who were readmitted. The

school board gave no reasons for singling out the eight, but

apparently expelled them because they were believed to be

leaders of the disturbance.

Were the eight permanently expelled students denied due

process of law—including the right to cross-examine and

confront witnesses—as guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment?

Constitutional Provision Involved

This matter involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States, which pro

vides :

All persons born or naturalized in the United States,

and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of

the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall

abridge the privileges and immunities of citizens of

the United States; nor shall any State deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due process

of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdic

tion the equal protection of the laws.

Statement

This case commenced as a school desegregation suit in

1965.1 Petitioners are black school children who are mem-

1 Reported decisions relating to desegregation are as follows:

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Ed., 372 F.2d 836 (5th

Cir. 1966), aff’d en bane, 380 F.2d 385; Boykins v. Fairfield Bd.

3

bers of the class on whose behalf it was filed. They seek

review of the decision of the Fifth Circuit which upheld

their permanent expulsion from the schools of the City of

Fairfield, Alabama. Following* a remand in 1972, by the

Court of Appeals, a final plan for the desegregation of

the schools was put into effect by the district court.

However, in the fall term of 1972, difficulties arose with

the implementation of the plan, which in turn resulted in

dissatisfaction on the part of black students at Fairfield

High School.2 In late October and early November, 1972,

black students conducted a boycott of the school. Motions

were filed in the district court seeking to correct problems

in implementing the desegregation plan and to reinstate

students suspended because of the boycott. On November

9, 1972, the district court ordered that the suspended stu

dents be reinstated and set a hearing to review the prob

lems that had given rise to the boycott. As part of its

order, the district court required the students to end the

boycott and return to class.

Nevertheless, difficulties persisted. On November 10,

1972, an incident occurred involving a black student and

a black faculty member.3 When other black students heard

of Ed., 399 F.2d 11 (5th Cir. 1958) ; Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of

Ed., 421 F.2d 1330 (5th Cir. 1970) ; Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of

Ed., 429 F.2d 1234 (5th Cir. 1970); Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of

Ed., 446 F.2d 973 (5th. Cir. 1971) ; Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of

Ed., 457 F.2d 1091 (5th Cir. 1972). As Judge Godbold noted in

dissent, the desegregation of the school district “has been a fruitful

source of litigation” because of the resistance to desegregation. 492

F.2d at 703, Appendix, p. 9a.

2 The problems included the alleged inability of black students

to participate as cheerleaders or as members of certain clubs, the

administration of discipline, particularly as it regarded tardiness,

and the lack of a Black Studies program.

8 The student was Clarence Young, one of those subsequently

expelled.

4

of the incident, a number of them left their classes. As

a result, the principal decided to close the school and send

all students home. Subsequently, notices were sent to

twenty-one students informing them that they had been

suspended for their actions of November 10 and would

receive notices later as to Board of Education conducted

hearings to decide whether they would be reinstated.

Before the hearings were held, a motion was filed in

the district court challenging the suspension of the twenty-

one students. Decision on the motion was deferred pend

ing the outcome of the administrative hearings, which were

held on November 25, 1972. (The transcript of the hear

ing was introduced in district court; record references

herein are to the Appendix filed in the Court of Appeals,

“A.” )

As the hearing commenced, the board’s attorney ex

plained the procedure. He began by reading an excerpt

from Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294

F.2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961), including language to the effect

that there was no right to cross-examination and that

written testimony could be presented (A. 53). The attor

ney then continued with the statement quoted by the Court

of Appeals at 492 F.2d 700. (See Appendix, infra at 4a-

5a.) tie said that the “School Administrator” presenting

the evidence could be questioned by the school board and

cross-examined by the attorney representing the children.4

However, as it developed, this purported right to cross-

examine was illusory. Each student charged was called in

with his or her parent and informed of the charges. The

principal presented the evidence against the student, but

4 Shortly thereafter, during a preliminary discussion regarding

another procedural issue, the school board attorney stated: “You

can cross-examine . . . any person who has presented evidence”

(A. 59).

5

with two exceptions5 it was hearsay and consisted of

written statements by teachers who were not available for

cross-examination. In most instances the statement was

limited to an assertion that the pupil either had not re

ported for class or had left class without permission.

While no overall objection was made to the introduction

of this hearsay, on two occasions objections were made to

specific testimony as hearsay (A. 73; 194). In any event,

both the district court and the Court of Appeals ruled

on and upheld the use of hearsay (Appendix, 5a-7a; 21a).

And, as the appeals court noted in rejecting petitioners’

claim, it had been the rule since 1961 in the circuit that

hearsay in the form of written statements could be used

under the decision in Dixon relied upon by the school board

attorney.

After the principal had presented evidence each stu

dent was allowed to present his or her story as to what

happened, although two of the expelled students were not

present when their names were called at the school board

hearing. It was clear that they had been waiting outside,

but left sometime during the five-hour proceeding because

they were not allowed to use the bathroom. Since they

had no transportation, they had to walk home and had not

returned by the end of the hearing (A. 338-339). Thus,

the only testimony against them was hearsay in the form

of a written statement from their first-period teacher al

leging merely that they had left her class without permis

sion.

Of the 21 students accused, four were readmitted im

mediately as of November 27, 1972; eight others were re

admitted one week later as of December 4; one student

was suspended for the remainder of the semester; and eight

5 Clarence Young and Beverly Claiborne.

6

others, petitioners here, were expelled permanently. Since

the school hoard did not state the reasons for its decisions,

it gave no explanation for the disparate results. As Judge

Godbold noted in dissent (492 F.2d at 705, Appendix, pp.

13a-14a), the only apparent basis for the expulsions was

that the school board concluded that the eight were leaders

in the disturbance. However, as he also correctly pointed

out, there was nothing introduced at the board hearing

that showed that most of those expelled did anything more

than numerous other students who were readmitted {Ibid.)6

Indeed, given the evidence concerning the eight students

selected for expulsion and the lack of explanation for their

being so selected, Judge Godbold’s conclusion that the pen

alties were arbitrarily severe because of their being based

upon matters outside the record (Appendix, 15a) is un

avoidable. Thus, Darlene Phelps and Cathy Scott testified

that they had been given permission to leave their class

(this testimony was corroborated by another student), con

trary to the written statement of their teacher. They fur

ther denied doing anything disruptive. To the contrary,

they had attempted to find a representative of the Com

munity Relations Service of the United States Department

of Justice, who had been sent to the school, to get his help

in calming the situation.

Jacques Guest and Linda Meadows testified that they

had left class because they had heard that another black

student was in trouble. Guest admitted that he went to one

class and told students that they should leave, but said it

was the teacher who actually dismissed the class (A.

203-04). Miss Meadows was also accused in a written

6 For example, the charge and evidence against Anthony. Wil

liams was exactly the same as against Cathy Scott and Darlene

Phelps, i.e., having Mrs. Sexton’s class without permission (A. 329-

330; see n. 18, infra)'. Nevertheless, Williams was readmitted

to school and Phelps and Scott were permanently expelled.

7

statement from one of the teachers that when he told her

to leave the classroom she cursed him. Miss Meadows, how

ever, testified that she did not actually go into his class

room (although she was standing outside in the hall) and

denied using profanity. The teacher himself did not testify

(A. 131-32).

Beverly Claiborne was presented with a written charge

that she failed to report to her first-period class. The prin

cipal also testified, based on his own knowledge, that when

Miss Claiborne was told that she would be expelled she

responded with profanity. Miss Claiborne, however, testi

fied that she had in fact reported to her first-period class

and had been excused by the teacher (A. 121.)7 With regard

to the profanity, she said that she made a statement to

herself and did not expect it to be heard (A. 127).

Clarence Young was the student who had the altercation

with a teacher that precipitated the disturbance. He had

gotten into an argument over whether the teacher should

apologize to a girl because he had accidentally hit her when

he opened a door. Words were exchanged that included

some insults hv Young, and he was taken into the prin

cipal’s office. He was there when the students began to

leave their classes.

John Hall and Beverly Law were the two students who

had left the hearing before their names were called. The

only evidence was written statements that they had left

class without permission; there was no testimony that they

had gone to other classes or had done anything more than

many of those readmitted.

The district court, in an order dated December 14, 1972,

held that due process had been complied with and that the

7 Another student, Beverly Williams was also accused of leaving

the same class without permission. She also testified that she had

been excused (A. 106). She was readmitted.

8

action of the school hoard was justified (Appendix, pp.

18a-23a).8 A timely Notice of Appeal was filed on Decem

ber 2, 1972.

In the meantime, the expelled students made efforts to

continue their education. A number of them enrolled in

private parochial schools at which they paid for tuition

and textbooks. Four of the students attempted in early

January, 1973, to enroll in public schools in neighboring

districts in order to complete their education. They were

informed, however, that they could not be accepted unless

the schools received from the superintendent of the Fair-

field schools approval of their enrollment. When they re

quested such approval, the superintendent refused on the

ground that they had been expelled from the Fairfield

school system.

Another motion for emergency relief was filed in the

district court on February 21, bringing these facts to the

court’s attention and requesting an order permitting the

students to be allowed to continue their public education

in some way. A hearing was held on the motion on March

2, 1973, and the motion was denied the same day by the

district court (Appendix, pp. 24a-26a). A notice of appeal

was filed with regard to that order, and that matter was

consolidated with the appeal already pending in the Fifth

Circuit.

On April 12, 1974, the Court of Appeals affirmed the

decision of the district court, over a dissent from Judge

Godbold. AH three judges, however, concurred in reject-

8 Thy Court also, in an order dated November 27, 1972, ruled on

the plaintiffs’ motion to correct the administration of the school

desegregation plan. I t granted relief with regard to monitoring

transfers of white students out of certain schools in the district,

the correcting of imbalances in the racial makeup of faculty at one

school, and the ending of three all-black classes at another, but

denied all other relief. This order is not at issue in this proceeding.

9

ing petitioners’ argument that they were entitled to con

frontation and cross-examination of the witnesses against

them; rather, the school board conld rely on written state

ments by teachers presented to it by the principal of the

school.

As of the date of filing this petition, one of the students

(Jacques Guest) remains out of school and is without a

high school diploma. The other seven were able to finish

high school, some at parochial schools, and two by going

to live with relatives in Mississippi. At least one student

was admitted to college. All eight retain on their records,

however, that they were permanently expelled from the

schools of Fairfield. Further, the school board is free to

continue to impose discipline upon other members of the

class pursuant to the procedures upheld by the Court of

Appeals.

REASONS WHY THE WRIT SHOULD BE GRANTED

Certiorari Should Be Granted Because the Issue of

the Due Process Mights of Public School Pupils in

Disciplinary Hearings Is of National Importance and

Because the Decision of the Fifth Circuit Conflicts

With Those of This Court and Other Federal Courts.

A. The Question of the Requirements o f Due Process in

School Disciplinary Proceedings Is o f Great National

Importance.

In recent years the lower federal courts have dealt with

increasing frequency with questions relating to school dis

cipline procedures. Beginning with Dixon v. Alabama State

Board of Education, 294 F.2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961), the courts

of appeals have attempted to apply, in school eases, deci-

10

sions of this Court dealing with procedural rights in other

areas.9

The rapid increase in the amount of litigation is a reflec

tion of the growing awareness and concern for the legal

rights of students generally. Stimulated by this Court’s

decisions in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954), and Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School Dist.,

393 U.S. 503 (1969), the area of concern has encompassed

issues such as the extent of the rights to free speech, press,

and association,10 the legality of searches and seizures,11

hair and dress regulations,12 and corporal punishment.13

See, Developments in the Law: Academic Freedom, 81

H arvard L aw R ev iew 1045, 1128-1159 (1968); Goldstein,

Reflections on Developing Trends in the Law of Student

Rights, 118 U. P a. L . R ev . 612 (1970); Wright, The New

Word Is “Pushout”, 4 Race Relations Reporter 8 (May

1973); Wright The Constitution on Campus, 22 V axd . L .

R ev . 1027 (1969).

With regard to student discipline in particular, concern

with what has been termed the “pushout” problem has

focused on the disproportionate number of black students

being subjected to severe punishment, particularly in school

systems in the process of desegregating. See, e.g., Bell,

Race and School Suspensions in Dallas, 62 Integrated Edu-

9 See, e.g., Madera v. Board of Ed. of City of New York, 386

F.2d 778 (2nd Cir. 1967) ; Williams v. Dade County School Board

441 F.2d 299 (5th Cir. 1971) ■ Betts v. Bd. of Ed. of City of Chi

cago, 466 F.2d 629 (7th Cir. 1972).

10 E.g., Karp v. Becken, 477 F.2d 171 (9th Cir. 1973).

11 E.g., People v. Overton, 20 N.Y.2d 360, 283 N.S.Y.2d 22, 229

N.E.2d 596 (1967), vacated and remanded, 393 U.S 85 (1968)

reinstated, 24 N.Y.2d 523, 301 N.Y.S.2d 479, 249 N E 2d 366

(1969).

12 E.g., Bishop v. Colaw, 450 F.2d 1069 (8th Cir. 1971).

13 E.g., Ware v. Estes, 328 F. Supp. 657 (N.D. Tex. 1971), aff’d,

458 F.2d 1360 (5th Cir. 1972).

11

cation 66 (Marcb-April 1973) ;14 Clarke, Race and Suspen

sions in New Orleans, 63 Integrated Education 30 (May-

June, 1973); The Student Pushout, Victim of Continued

Resistance to Desegregation (Southern Regional Council

and Robert F. Kennedy Memorial, 1973).16 Recently, the

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, has begun

a comprehensive investigation into this question as a result

of the accumulation of evidence indicating a relationship

between discipline and desegregation.

To reduce the opportunity for racial discrimination, the

procedures used for pupil discipline must be adequate to

ensure that proper and non-arbitrary decisions are made.

Thus, while much of the discussion of student discipline

to date has dealt with procedural questions as such,16 the

relationship between those issues and the substantive bases

for imposing discipline should not be overlooked.

14 In an opinion as yet unreported, the United States District

Court for the Northern District of Texas has found “white institu

tional racism” in the operation of the school discipline system in

Dallas because of the disproportionate number of black students

subjected to harsh discipline. Hawkins v. Coleman,----- F. Supp.

----- (Civ. Action No. 3-5774-B, June 5, 1974). Thus in 1973-74,

while blacks were 40.9% of the students, they accounted for 59.4%

of the suspensions. Moreover, blacks were suspended for signifi

cantly longer periods than were whites.

16 According to The Student Pushout, 71% of the pupils expelled

or suspended in Dade County, Florida, in 1972 were black; in the

Charlotte-Mecklenburg' County system, suspensions rose from 1.544

in 1968-69 to 6,652 in 1970-71, and declined to 6,201 in 1971-72.

The vast majority of those suspended were blacks. Similarly, while

25 blacks and 11 whites were expelled in 1968-69, 94 blacks and 14

whites were expelled in 1971-72 (The Student Pushout, pp. 4-5).

A study prepared by the Office1 of Civil Eights of the Department

of Health, Education, and Welfare, indicates that the expulsion

rate nationwide for black students-during the 1970-71 school year

•was three dimes that of non-minority students (Id. at pp, 5-6). -

16 See, e.g., Goldstein, The Scope and Sources of School Board

Authority ; to Regulate Student Conduct apd Status: A 'Nonconsti

tutional Analysis, 117 IJ. Pa. L. Rev. 373 (1969) ; Hudgins, Disci

pline bf Secondary School Students and Procedural Due Process:

A Standard, 7 Wake Forest L. Rev.; 32 (1970) A

12

To date, this Court has not addressed itself to the ques

tion of the procedural rights of students. It has recognized

the importance of the issue, however, by its grant of review

in two cases to be argued during the October 1974 Term.17

Petitioners urge that this case presents, as will be dis

cussed below, additional issues of great importance that

are not raised in the other cases before the Court. There

fore, this case is an appropriate one for a grant of cer

tiorari.

B. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Resolve the Conflict

Between Decisions o f This Court and the Decision

Below.

It is clear that the school board, in order to decide both

whether to impose any discipline and what discipline was

appropriate, had to resolve disputed questions of fact. For

example, in the case of Cathy Scott and Darlene Phelps

it had to determine whether the teacher had or had not

given permission to leave, or if the teacher had said

something* that might have been interpreted as giving

permission. Depending on how the facts were resolved,

the board might have decided to impose no discipline or

a lesser punishment than permanent expulsion. To have

decided on the harshest punishment possible, the board

must either have concluded that the teacher had not given

permission or have decided, on some ground not pre

sented at the hearing, that the two students were leaders

of the disruption.

Of course, the only basis for concluding that no per

mission was given was hearsay in the form of the signed

17 Goss v. Lopez, No. 73-898 (prob. juris, noted, Feb. 19, 1974) ■

Wood v. Strickland, No. 73-1285 (cert, granted, April 15,’ 1974) •

See also, Board of School Commissioners v. Jacobs, No.’73-1347

{cert, granted, June 3, 1974).

13

statement by the teacher.18 The teacher was not present

to be questioned either by counsel for the students or by

the school board itself.

The court below rejected petitioners’ argument that this

Court’s decisions in Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471

(1972) and Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970), re

quired “confrontation and cross-examination of witnesses,

especially where severe punishments are meted out on

disputed facts.” 492 F.2d at 701. Although the court found

the argument “seductive,” it concluded that “it will not

do” to apply those protections to school disciplinary pro

ceedings, because such proceedings were “disparate” from

parole and welfare revocation hearings and a body of lay

men could not be required to apply strict rules of evi

dence. 492 F.2d at 701-702; Appendix, pp. 5a-7a.

In recent years this Court has handed down a series of

decisions that establish procedural rights when a govern

ment agency acts to deprive a person of a benefit. In ad

dition to Morrissey and Goldberg, they include: In re

18 The entire testimony was as follows:

Mr. Sweeney: What evidence do you have?

Mr. Turner: A signed statement from her teacher saying

she left class without her permission.

Mr. Sweeney: Who is the teacher?

Mr. Turner: Mrs. Sexton, first period history.

Mr. Sweeney: What does the statement say?

Mr. Turner: I t says that Darlene Phelps left class without

permission on Friday, November the 10th, 1972 (A. 288.)

* * *

Mr. Sweeney: Give us the details that support this.

Mr. Turner: Cathy was in the first period class of Mrs. Sex

ton and left that class without permission of the teacher.

Mr. Newton: Do you have a written statement from Mrs.

Sexton to that effect ?

Mr. Turner: Yes. (A. 303.) ., ,

14

Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967) (juvenile court) ;19 Bell v. Burson,

402 U.S. 535 (1971) (automobile license revocation);

Gagnon v. Scarpelli, 411 U.S. 778 (1973) (probation re

vocation) ; Wolff v. McDonnell, ----- U.S. ----- , 42 U.S.L.

Week 5191 (1974) (prison discipline). This Court has rec

ognized, in the words of Goldberg, that, “in almost every

setting where important decisions turn on questions of

fact, due process requires an opportunity to confront and

cross-examine adverse witnesses.” 397 U.S. at 269.

Only in Wolff v. McDonnell, did this Court find an ex

ception to the general rule. Wolff makes it clear, however,

that the decision is based on the inherent dangers that

exist in prison society and on the fact that the deprivation

imposed as a result of discipline was not that serious. Thus,

the Court would not apply “procedural rules designed for

free citizens in an open society.” 42 U.S.L. Week at 5197.

The requirement of confrontation and cross-examination,

of course, is but one protection against decisions that de

prive persons of benefits arbitrarily. If a school board

does not, because it cannot, fairly resolve disputed factual

issues, and if it can impose severe discipline on the basis

of evidence that cannot be challenged because the accuser

is absent, then it can and will act arbitrarily.

On the other hand, the basis for the school board’s

actions in this case might have been either a conclusion that

those expelled were leaders, or some unarticulated ad hoc

determination that they had done something warranting

more severe punishment. As Judge Oodbold pointed out,

in most instances the evidence introduced showed that they

19 I t is ironic that the petitioners would have been better off, in

some respects, in juvenile court both because cf the procedures that

would have been afforded and because even if they had been adjudi

cated delinquent they would have been entitled, under Alabama

law, to an education. See, Code of Alabama, Title 52, §§ 579 and

598.

15

liad done nothing more than others who were readmitted.

Needless to say, such arbitrariness would he a violation

of due process and could only be protected against by the

imposition of adequate procedural safeguards. Further, by

requiring that proper procedures be followed, the federal

courts will not be required to act as boards of review of

school discipline proceedings. It is one thing, a matter of

perhaps considerable burden to the courts, to review myriad

disciplinary hearings. It is another to set standards of fair

ness and due process by which the hearings are to be con

ducted.

This case, therefore, presents squarely an issue not yet

resolved by this Court, whether pupils in public schools are

to be afforded the same protections against arbitrary

actions as are other “free citizens” or whether they are to

be dealt with as if the school were a prison. In light of

the general importance of that question as demonstrated

above, the petition should be granted to resolve the appar

ent conflict of the decision below with the decisions of this

Court.

C. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Resolve the Conflict

Between the Decision Below and Decisions of Another

Circuit and of District Courts in Other Circuits.

Finally, the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit has

held that it was a denial of due process to expel students

without a hearing at which they could “cross-examine ad

verse witnesses.” Black Coalition v. Portland School Dis

trict No. 1, 484 F.2d 1040, 1045 (9th Cir. 1973). District

Courts in two other circuits have made similar rulings.

DeJesus v. Penberthy, 344 F. Supp. 70 (D. Conn. 1972);

Mills v. Board of Ed. of District of Columbia, 348 F. Supp.

866 (D.D.C. 1972). Certiorari should therefore be granted

to resolve these conflicts.

16

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the petition for writ of certi

orari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reen berg

' J am es M. N a brit , III

C h a r les S t e p h e n R alston

C h a rles E. W il l ia m s , III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

D e m e t r iu s C. N ew to n

2121 8th Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

Decision of Fifth Circuit, April 12, 1974

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

GEE, Circuit Judge:

As the Fairfield, Alabama, school case comes before us for

the seventh time,1 the great issues of segregation and integra

tion which were, for our circuit, largely fought out on this

very field 2 have departed like the Captains and the Kings, to

be replaced by the petulance which this record reveals and the

spectre of resegregation by white flight from the school

system. As the trial court observed:

The Court has had many hearings in the Fairfield School

Case. When the hearings began there was a white majority

in the school system. There is now a black majority and

this majority is growing with every term and with every

court order. The number of students in the System is

dropping every year with the consequent loss of revenue.

The cooperation between the races apparently has disap

peared. Picayunish claims are being made on the one hand

and vigorously contested on the other. If this System is to

survive this continued litigation must come to an end.

Many of the black students appear to have overlooked the

point that the object of attending Fairfield High is to

obtain an education and not merely to maintain a point of

which an issue may be made.

Appellants are Negro school children who are members of

the class who brought this suit originally. They complain of

the process by which nine Negro students were punished for

misconduct, of the severity of the punishment which some

received, and of the refusal of the district court to order the

school authorities to grant various demands which the Negro

1. United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Ed., 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir.

1966), aff’d en banc, 380 F.2d 385; Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed.,

399 F.2d 11 (5th Cir. 1968); Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed., 421 F.2d

1330 (5th Cir. 1970); Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed., 429 F.2d 1234

(5th Cir. 1970); Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed., 446 F.2d 973 (5th

Cir. 1971); Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed., 457 F.2d 1091 (5th Cir.

1972).

2. See the landmark panel and en banc opinions at 372 F.2d 836

(1966) and 380 F.2d 385 (1967).

la

2a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

students had sought to enforce by the boycott which led

indirectly to their expulsion. We affirm.

Following the most recent remand of this case to the

district court, a final plan for the desegregation of the Fair-

field schools was put into effect. When school next com

menced, however, Negro students conducted a boycott of the

school, seeking to enforce demands such as that the School

Board:

1. Prohibit the practice of requiring spring pre-registration

of classes although, as the court below found, all students,

Negro and white, were required to pre-register and no dis

crimination was shown.

2. Prohibit school authorities from allowing white students

to leave campus for lunch since it was generally more conve

nient for them to go home for lunch than for Negro students.

3. Prohibit the school from serving inferior food to Negro

students, although all students eat in the same two cafeterias.

4. Increase the time for lunch, and the time between

classes.

5. Order that more Negro students become cheerleaders

and members of the band, even though the present selection

process was found by the district court to involve no racial

discrimination.

6. Order more Negro students to become members of the

Pep Club even though membership is open to all students.

7. Require a Negro History Week, and a Black Studies

curriculum.

8. Require “sock hops” and school proms.

9. Change the school disciplinary policy which makes it a

school offense to be late for class an excessive number of

times.

10. Require the school to open the school doors before 7:30

each morning.

3a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

11. Order teachers at the Fairfield School System to re

frain from using profanity.

12. Allow Negro students to attend dancing class without

paying the fee required of other students.

13. Require the school officials to distribute textbooks

which are in better condition.

This boycott, commenced in late October and carried over

into early November, resulted in the suspension of over 100

students, all but three of them Negro, from school. A series

of motions by counsel for plaintiffs followed, seeking enforce

ment of such demands as the above and reinstatement of the

suspended students. On November 9, 1972, the court below

entered its order requiring the readmission of the suspended

students and setting a hearing on the motion seeking review

of the demands upon which the boycott had been based. The

ordered readmission was contingent upon termination of the

boycott, return to class by all students, and an end of disrup

tive activities.

Most students returned to class the next day. Almost

immediately, however, the same sort of difficulties which had

plagued the school term recommenced. Clarence Young, one

of the students who was later expelled, intervened in a trivial

incident and undertook to instruct a Negro faculty member as

to the proprieties of his behavior. An altercation between

them followed. Young berated the instructor, using such

epithets as “Uncle Tom” and “half whitey.” He was taken to

the principal’s office, and word of the incident immediately

spread through the school. Various students, including the

other expellees, left class without permission. Some, urging

others to join them, went from classroom to classroom calling

for students to leave classes to participate in a meeting to

discuss what should be done to rescue Clarence Young. Many

students left class, the police were called, and attempts were

made to persuade the students to return to class without much

4a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

success. School was therefore closed in the middle of the

morning and all students sent home.

Twenty-one students were subsequently sent notices of sus

pension from school for their participation in the disruptions

of November 10 and were also informed that individual hear

ings would later be held by the Board of Education to decide

whether they should be reinstated. These hearings were held

on November 25, 1972. As a result of the hearings, four of

the students were immediately readmitted, eight were read

mitted after a week’s further suspension, one was suspended

for the remainder of the semester, and eight were expelled.

The record indicates that, as a result of the expulsion, difficul

ty was later encountered by the expelled students in obtaining

entrance to other public schools. As of a hearing held by the

district court in March of 1973, none of these students had

reapplied to the Fairfield School Board, so that what the

consequences of such a reapplication would have been are

unknown. However, at oral argument the court was advised

by counsel for plaintiffs that all but one of these students

were attending school somewhere as of that time.

The procedures which were followed in the hearing, and of

which complaint is here made, were outlined by counsel for

the Board as follows:

Let me ask you if this procedure will be agreeable. We

will call each student from outside into the conference room

with his parent or guardian. We will explain to the child

what he has been charged with, and ask him if it is clear in

his mind what school rules he has violated. If he has no

questions, we will then present the evidence against the

child to support the accusations. Having done that, we will

ask the student if he has anything to say to contradict the

charges that have been made against him, or the evidence

to support charges that have been made against him. After

that we will—I think the Board should ask the School

Administrator that is presenting the evidence any—and the

child—any questions that you think are relevant In order to

5a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

resolve any conflict. We’re going to accord Mr. Newton the

privilege of cross-examination. It is not a right that he can

insist on, but we are showing him that courtesy. After the

Board, after the school and the child have presented what

ever evidence they want, then we will excuse the child and

go on to the next student. Is that an agreeable process?

Each student was represented by the same counsel, Mr.

Demetrius C. Newton, and the only objection to the suggested

procedure voiced by him was a desire on his part to himself

determine and declare whether the student understood the

charge against him rather than have the student make and

state his determination of that matter.3 The suggested proce

dures were uniformly followed in conducting the Board’s

hearings.

[1] Appellants principally complain that much of the evi

dence upon which the expulsions were based consisted of what

was technically hearsay. This is undoubtedly correct. The

main witness against the students was the school principal,

Mr. Hershell Turner, who had investigated the charges

against the students and who presented the results of his

investigation of each incident to the School Board. In some

instances Turner had first-hand knowledge, and in others his

testimony was based on attendance records and other reports

which could likely have been qualified under exceptions to the

hearsay rule; but in main it consisted of reading or reciting

statements made by teachers in response to his inquiries.

xAs to this contention, appellants correctly concede that the

present rule of this circuit in school discipline cases affords

them no comfort. “[T]he student should be given the names

of the witnesses against him and an oral or written report on

the facts to which each witness testifies.” Dixon v. Alabama

State Board of Education, 294 F.2d 150, 159 (5th Cir. 1961).

They contend, however, that we should read the Supreme

3. In the event, the charges were of such a simple nature, e. g.,

reviling the teacher before the class, or leaving class after having

been told not to do so, that no problem was presented.

6a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

Court’s Goldberg4 and Morrissey5 decisions as expanding the

requirements of Dixon to add to them universal confrontation

and cross-examination of witnesses, especially where severe

punishments are meted out on disputed facts. We decline to

do so.

There is a seductive quality to the argument—advanced

here to justify the importation of technical rules of evidence

into administrative hearings conducted by laymen—that, since

a free public education is a thing of great value, comparable

to that of welfare sustenance or the curtailed liberty of a

parolee, the safeguards applicable to these should apply to it.

At argument appellants’ counsel, in response to questions,

opined that a right to appointed counsel was probably also

existent. In this view we stand but a step away from the

application of the strictissimi juris due process requirements

of criminal trials to high school disciplinary processes. And if

to high school, why not to elementary school? It will not do.

[2] The requirements of due process are sufficiently flexi

ble to accommodate themselves to various persons, interests

and tribunals without reduction to a stereotype and hence to

absurdity.6 As Mr. Justice Stewart, writing for the Court,

stated in Cafeteria Workers v. McElroy, 367 U.S. 886, at 895,

81 S.Ct. 1743, at 1748, 6 L.Ed.2d 1230 (1961):

The very nature of due process negates any concept of

inflexible procedures universally applicable to every imagi

nable situation, [citations omitted] “ ‘[D]ue process,’ unlike

some legal rules, is not a technical conception with a fixed

content unrelated to time, place and circumstances.” It is*

4. Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254, 90 S.Ct. 1011. 25 L,Ed.2d 287

(1970).

5. Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471, 92 S.Ct. 2593, 33 L.Ed.2d 484

(1972).

6. “[T]he standards of procedural due process are not wooden abso

lutes. The sufficiency of procedures employed in any particular

situation must be judged in the light of the parties, the subject

matter and the circumstances involved.” Ferguson v. Thomas, 430

F.2d 852, 856 (5th Cir. 1970).

7a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

“compounded of history, reason, the past course of decisions

. ” Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v.

McGrath, 341 U.S. 123, 162-163, 71 S.Ct. 624, 643, 95 L.Ed.

817, 848, 849 (concurring opinion).

Basic fairness and integrity of the fact-finding process are the

guiding stars. Important as they are, the rights at stake in a

school disciplinary hearing may be fairly determined upon the

“hearsay” evidence of school administrators charged with the

duty of investigating the incidents. We decline to place upon

a board of laymen the duty of observing and applying the

common-law rules of evidence.

Indeed it is plain that Morrissey does not go so far as

appellants would have us take the Fairfield Board of Educa

tion. The right of confrontation and cross-examination there

discerned in the parolee is not absolute but may be denied for

good cause, and the receipt of evidence which would be barred

by the hearsay rule is specifically suggested. Morrissey, supra

408 U.S. note 5, at 489. It well may be that all Morrissey

contemplates on this head is precisely what appellants were

accorded: a right to confront and cross-examine such adverse

witnesses as appear, without the technical strictures upon

their testimony of the hearsay rule. But whether or no, we

reject the attempted analogy of student discipline to parole

revocation or the termination of welfare benefits. Cf. Stu

dent Discipline, 45 F.R.D. 133, at 142. The situations treated

are simply too disparate to permit an uncritical transfer of

specific due process requirements from one to the other.

[3, 4] Complaint is also made of the severity of the punish

ment imposed on those who were expelled. The punishment

was severe, but we cannot say that it was so severe as to have

been arbitrary or clearly unreasonable. It is agreed on all

hands that school officials exercise a comprehensive authority,

within constitutional bounds, to maintain good order and

discipline on school grounds. E. g., Tinker v. Des Moines

Community School Dist., 393 U.S. 503, 507, 89 S.Ct. 733, 21

L.Ed.2d 731 (1969); Bright v. Nunn, 448 F.2d 245, 249 (6th Cir.

8a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

1971). And in Ferguson v. Thomas, supra note 6, 430 F.2d at

859, we noted that the findings of school agencies “ .

when reached by correct procedures and supported by sub

stantial evidence, are entitled to great wreight. . . . ”

The Fairfield School Board was presented with a situation

of recurring disorder which bid well to disrupt finally a school

year already crippled. Firm action was called for and was

taken, but no indiscriminate or mass discipline was imposed.

The punishment meted out was such as has traditionally been

imposed by school authorities in severe cases. The district

court has reviewed the evidence supporting the Board’s action

in each instance, as have we, and has concluded that it is

substantial. We have held that due process was accorded, and

we cannot say that the findings of the court below were

erroneous.

[5] Finally, appellants complain of the refusal of the dis

trict court, in the name of integration, to require the Board to

accede to such demands as are quoted above. Whatever merit

these propositions may have as suggestions to the School

Board, on the record they are not for our cognizance. The

court did not err in finding from the evidence presented that

each of them was either insubstantial or involved no racial

discrimination. It appears that Fairfield’s dual school system

is drawing to a close and with it, we may hope, this long case.

Affirmed.

GODBOLD, Circuit Judge (dissenting in part):

I must record a partial dissent, to that part of the decision

which affirms the expulsion of eight black students.

The power to expel students is not unlimited and cannot be

arbitrarily exercised. Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Edu

cation, 294 F.2d 150, 157 (C.A.5, 1961).

Turning then to the nature of the governmental power to

expel the plaintiffs, it must be conceded . . . that

that power is not unlimited and cannot be arbitrarily exer-

9a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

cised. Admittedly, there must be some reasonable and

constitutional grounds for expulsion or the courts would

have a duty to require reinstatement.

Only recently we said that there can be such shocking dispari

ty between an offense by a pupil and the disciplinary penalty

imposed upon him by school authorities that the commands of

the Fourteenth Amendment have not been met. Lee v.

Macon County Board of Education (Randolph County), 490

F.2d 458 [C.A.5, 1974], Accepting the foregoing principle, the

majority hold, though without discussion of the underlying

facts, that the expulsions of eight pupils were not so severe as

to have been arbitrary or clearly unreasonable.

1. The facts.

The background is as stated in the majority opinion. Oper

ation of the Fairfield school system has been a fruitful source

of litigation. The Board is now before us for at least the

seventh time. This is not to say that the Board cannot be

right and blacks cannot be wrong, but that the Board’s track

record in desegregating the system must be considered as part

of the overall circumstances of the present case. More than

100 students were suspended from the Fairfield High School

I. United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Ed., 372 F.2d 836 (C.A.5,

1966), aff’d en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (1967) [reversing decision in favor

of Board, ordering desegregation of schools and permitting freedom

of choice]; Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed., 399 F.2d 11 (C.A.5, 1968)

[reversing Board’s denial of freedom-of-choice applications of blacks

to transfer to formerly all-white schools]; Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of

Ed., 421 F.2d 1330 (C.A.5, 1970) [reversing because freedom-of-

choice not operating acceptably and school attendance zones drawn

by Board in a manner reducing rather than furthering desegrega

tion]; Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed., 429 F.2d 1234 (C.A.5, 1970)

[remanding because desegregation plan of Board did not change

status of integration in elementary schools and did not explore

possible alternatives as to junior and senior high schools]; Boykins

v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed., 446 F.2d 973 (C.A.5, 1971) [remanding for

reconsideration in the light of new Supreme Court decision]; Boy

kins v. Fairfield Bd. of Ed., 457 F.2d 1091 (C.A.5, 1972) [reversing

and remanding for failure to desegregate an ali-biack school and for

additional hearing on issue of whether black high school students

were being purposefully segregated by being placed in classes held

in a separate building].

10a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

because of repeated absences during a black boycott. On

November 9, 1972, those suspended were ordered by the

District Court to be readmitted, contingent upon termination

of the boycott, return of all students to classes, and an end to

disruptive activities. Readmissions began on the morning of

November 10. The Board takes the position, and the District

Court agreed, that the eight pupils were expelled for what

they did that day. Let us see what it was.

Clarence Young: Events involving him triggered the diffi

culties of November 10. The charge against him was:

He was disrespectful for authority and carrying on in the

hall as in the sense of inciting something among the stu

dents.

The testimony against him came from Coach Evans, a Negro,

plus a brief statement by Principal Turner. From the testi

mony the Board could conclude that the following events

occurred. It was necessary for suspended students to get

passes from the guidance office to return to classes. On the

morning of November 10 students began walking into the

building where the guidance office was located. Young

seemed to be directing other students to come in the build

ing because he stopped at the front door at the main

entrance up there mouthing off at the other students, and

getting, like he was getting everything together for them to

march in the room.

Coach Evans opened a door and the door struck a male and

then a female student in the line of students waiting to get

passes. Evans apologized to them. Either before he apologiz

ed, or while he was doing so, or immediately after he had done

so—the facts are unclear—Young told him he owed an apolo

gy to the female.2 Immediately thereafter other students

began talking with Young. Evans considered that Young

2. This is the incident that the majority opinion describes as Young’s

“undertaking] to instruct a Negro faculty member as to the proprie

ties of his behavior.”

11a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

“was trying to bring the crowd on,” that Young was “for the

wrong thing.” Coach Evans felt “in my expectation, he didn’t

come there to go to school that day. That is my expectation.

I could be wrong.” Evans secured a pass for Young and gave

it to him so that he would go on to class. As Young walked

away he referred to Evans as “Uncle Tom” and “Half Whi-

tey”. As Young crossed an open area en route to his class he

was seen to be “carrying on.” A city councilman present saw

him and told Evans he should have a talk with Young because

“it looks like he is for the wrong thing.”

Coach Evans engaged Young in conversation, and Young

took the position he had done no wrong and was being “picked

on.” Possibly he repeated the racial epithets he had earlier

used. Evans took him to the principal’s office and talked with

him. Young was excited and talked sufficiently loudly that a

staff member suggested that the principal also go into the

office, and Principal Turner went in and stayed briefly. A

friend of Young’s called his mother, she came to the office,

and in the ensuing conversation she twice told her son to

“simmer down.”

Evans testified that he did not consider Young to be a

leader of the other students. He did, however, hear Young

telling other students to get their passes. Evans disapproved

of this, though his reason is unclear, since without dispute the

necessity for passes was being communicated by word of

mouth.

As Judge Gee’s opinion points out, word spread about the

difficulty with Young, some black students left their classes,

and some went to other rooms and called for other students to

leave classes and join in a meeting to discuss what should be

done about the incident. A group gathered outside the princi

pal’s office where conversations with Young were, or had

been, going on. That, brings us to the facts concerning the

other expellees.

12a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

Jacque Guest: The charge was that he left class without

permission and encouraged other students either not to go to

class or to walk out of classes. He admitted the offense,

including going to another classroom and encouraging stu

dents to leave.

Beverly Claiborne: The charge against her was twofold:

first, that she obtained a pass but did not go to her first

period class; second, that subsequently Principal Turner told

her she was expelled and began to explain something to her

[apparently her right to a hearing], whereupon she got up and

left his office and in an outer office, in the presence of

members of his staff and other students, used profanity

concerning him.3 Miss Claiborne admitted saying the words

but claimed she had said them to herself and not “out loud.”

Linda Meadows: The charge was that she came to a class

room other than that to which she was assigned, the teacher

told her to leave, and she cursed him in the presence of the

class and left. The Board was entitled to accept the written

statement of the teacher that this occurred. It could accept

Miss Meadows’ testimony that her purpose in going to the

classroom was to see if other students who had participated in

the walkout were in the room. There is, however, no evidence

that she or anyone with her urged students in the classroom to

leave class or indeed said anything to them. On cross exami

nation of Miss Meadows the Board attorney questioned her

concerning whether she went to classrooms other than to one

to which she admitted going, and she denied doing so, and

there is no evidence that in fact she did.

Darlene Phelps and Cathy Scott: The charge was leaving

their first period classroom without permission. The Board

could accept their teacher’s statement that they did so. Miss

Phelps acknowledged going to another classroom, stating that

she went to a study hall and complained to the teacher about

3. The verbiage is unrevealed because at the Board hearing it was not

verbalized but written on a piece of paper that was handed around

and discussed.

13a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

what was occurring [presumably the events of the morning].

That teacher neither testified nor gave a statement, and there

is no evidence that Miss Phelps attempted to get students to

leave the study hall, or indeed that she said anything to the

students, or that her conduct was disruptive. Faculty mem

ber Bird testified that in the presence of Cathy Scott he told a

group of students to return to their classes.

John Hall and Beverly Law: They were present for the

hearing before the Board but, after several hours, left before

their cases were reached. The Board heard their cases in

their absence. The evidence against them, which the Board

could accept, was the written statement of their teacher that

they left class without permission after being told repeatedly

to remain.

2. The District Court order.

In reviewing the Board action, the District Court recog

nized, citing Dixon, that part of its function was to determine

“whether there was evidence of some reasonable or constitu

tional ground for the action taken in imposing the sentence of

expulsion.” In rejecting plaintiffs’ contention that the expel

lees were punished because they had been leaders in the

boycott before November 10, the court said:

The evidence does not show that these students were

disciplined for being leaders in the boycott prior to Novem

ber 10, 1972, but the fact that they became leaders in the

continuation of the demonstration on November 10, 1972,

was a matter certainly material for the consideration of the

school authorities in view of the Court’s order of November

9, 1972, and the school authorities’ attempt to prevent

further demonstrations and disturbances when school recon

vened on November 10, 1972. (Emphasis added.)

The facts, as set out above, reveal that the District Judge’s

premise that the eight expellees were “leaders in the continu

ation of the demonstration on November 10” was wrong, at

least with respect to Phelps, Scott, Hall and Law. Phelps’

14a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

offense was to leave her class, go to another classroom and

register a complaint with the teacher. Scott left her class and

later was where she could have heard a teacher tell students

to return to class. Hall and Law left their class after being

told not to. Turning to the other four, the Board could accept

that part of Evans’ testimony tending to describe the actions

of Young as a leader.4 Guest’s actions were those of a leader.

Claiborne and Meadows cannot accurately be described as

leaders.

The situation on November 10 was volatile. School officials

were attempting to defuse it and get on with the primary job

of educating young people. It was important that students go

to and remain in their classrooms. Conduct that in a different

atmosphere might have called for less severe punishment

could, under these particular circumstances, justify more se

vere penalties. Cf. Dunn v. Tyler Independent School Dis

trict, 460 F.2d 137 (C.A.5, 1972). In my view the expulsions of

Young and Guest were within constitutional bounds. I am

much less certain as to Claiborne and Meadows—I have the

feeling that in the calm light of another day the District

Court might not have sustained their expulsions but for the

fact he erroneously thought they were leaders in re-igniting

disorder. I am not uncertain as to Phelps, Scott, Hall and

Law. What they did, and all that they did, was to leave their

classrooms without authority just as did numerous others on

the same occasion. With respect to these four, there is no

evidence that any one of them urged any other student to

leave class or disturbed any classroom, participated in any

disorder (other than leaving class) or committed any act of

leadership. A sentence of lifetime exile from the public school

system of the place where they reside cannot stand under

these circumstances.

[A] sentence of banishment from the local educational sys

tem is, insofar as the institution has power to act, the

4. Also Young’s expulsion was independently sustainable on the

basis of his use of expithets directed at Coach Evans.

15a

BOYKINS v, FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

extreme penalty, the ultimate punishment. In our increas

ingly technological society getting at least a high school

education is almost necessary for survival. Stripping a

child of access to educational opportunity is a life sentence

to second-rate citizenship, unless the child has the financial

ability to migrate to another school system or enter private

school.

Private citizens, law making bodies, and the media all

bend their efforts toward encouraging children to complete

their high school educations and to avoid becoming dropouts

and burdens to society. In the twenty years since Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686, 98 L.Ed. 873

(1954), this country has committed itself to a policy against

state-imposed public school segregation. It is not lesser but

more stringent state action to bar a child forever from

public school, with the result that he secures no education at

all.

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, supra, 490 F.2d p.

460.

The plaintiffs urge that they were singled out for expulsion

for reasons other than what they did on November 10. There

is good circumstantial evidence supporting that claim. After

their expulsion at least four of them attempted to enroll in

other public high schools in adjacent geographical areas, and

were informed that each would have to secure an “OK” from

the Fairfield superintendent to do so. They approached him,

asked his approval, and it was refused. The superintendent

testified that all transcripts and other required records were

furnished but that affirmative statements in the form of any

“OK” or “recommendation” were denied. Obviously the su

perintendent had no legal duty to assist these young people to

get into schools elsewhere. But I confess my inability to

understand the unwillingness to lift a finger—even to the

extent of a statement saying “we expelled them for good

reasons, but if you want to accept them we do not object.”

Sentence of exile was coupled with a specific refusal to act,

16a

BOYKINS v. FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

with the consequence that the effective scope of exile was

broadened to include adjoining geographical areas as well.

The Board’s argument that it does not control the admission

policies of other schools is a subterfuge. No one contends that

it does. The Superintendent’s refusal cut off at the threshold

the possibility that other systems, pursuant to their own

admission policies, might have been willing to accept the

students.

Secondly, there was obvious disparity in penalties. Numer

ous students left their classes without permission. A number

of those charged for doing so were not expelled, including one

who left ostensibly to go home but remained on the school

grounds knowing that he was not supposed to do so; another

who left and went home; a third who left class in response to

students coming to his classroom and telling him about Clar

ence Young.

Thirdly, the Board declined to receive evidence of prior

conduct, good or bad, by the charged students. It announced

that it was limiting itself to consideration of events of No

vember 10. This, of course, makes the disparity in punish

ments more suspect. It leaves no explanation, or even at

tempt at explanation, for the wide disparities. The Board’s

response is that it is entitled to impose differing penalties.

Indeed it has that authority but the presence of power is not

an explanation for the manner of exercise. Additionally, this

limitation of evidence by the Board accentuates more sharply

the erroneous premise by the District Judge that all expellees

were leaders on November 10.

With apparent determination to drive every nail into the

coffin, the majority make the point that none of the students

reapplied for admission, so that what the consequences of

reapplication would have been are unknown. This was hardly

a promising request to be made to a system that would not

even “OK” an attempt to apply for admission to another

system, but pretermitting that point, there is no such require

ment as a condition precedent to judicial consideration or

17a

BOYKINS v, FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION

judicial relief, nor does failure to reapply diminish the finality

of the Board’s decision of permanent expulsion. Also, while it

is not a matter of formal record, the court inquired at oral

argument about the ultimate fate of the expellees. We were

told that some were admitted to parochial schools where

tuition is required, at least two are attending schools in

another state, and one is known to be out of school. The

Fairfield system records on each of the eight students contin

ue to reflect that he or she was permanently throwm out of

the system and imply that each was guilty of conduct justify

ing that penalty. This impediment to college admission and

to public and private employment is now' made immutable.

Thus the statement by the majority that all but one of the

eight were able to find schooling elsewhere is mere legal

soothing syrup neither mitigating the wrong nor mooting the

case.

18a

Decision of District Court, December 14, 1972

Opinion in L ieu or F ormal F indings

By this Court’s opinion of November 27, 1972, the plain

tiffs’ motion seeking relief from explusion or suspension of

certain students was continued pending administrative

hearing. The Fairfield Board of Education held the ad

ministrative hearings on November 25, 1972. It is not

questioned that the students involved had advanced writ

ten notice of the charges against them and that upon the

hearing each one was advised of the charges and later of

the action taken by the Board. Twenty-one students were

involved. The following students were readmitted as of

November 27,1972: Marsha Gulley, Randy Lawrence, Linda

Watts and Anthony Williams. The following students

were readmitted as of December 4, 1972: Cleophus Carter,

David Coleman, Roland Lawrence, Richard McCurtis, Eddie

McKenzie, Roger McLin, Falenza Pickens and Beverly Wil

liams. Vanessa Arrington was suspended for the remainder

of the semester. The following students were expelled:

Beverly Claiborne, Linda Meadows, Clarence Young,

Jacques Guest, Darlene Phelps, Cathy Scott, John Hall

and Beverly Law.

The motion as it now stands challenges the suspension of

Vanessa Arrington for the remainder of the semester and

the expulsion of the eight students above named.

As found by the order of November 9, 1972, some 114

students who were involved in the boycott were dropped

from the roll because of absences of 20 or more days, in

violation of Board of Education Rule 20. The Court di

rected the readmittance of these students, including those

later involved in the expulsion and suspension action.

The Court was assured by the counsel for the plaintiffs

that if these students were readmitted, plaintiffs and their

19a

Decision, of District Court, December 14, 1972

counsel would exercise every reasonable effort to terminate

the boycott by November 10, 1972, inasfar as the students

themselves at Fairfield High School were concerned. In

the order of November 9, 1972, the Court stated that:

“The Court does not look with favor upon any action

that contravenes the principle that he who seeks equity

must offer to do equity. Consequently, the relief af

forded the movants is conditioned upon the abandon

ment of the boycott by all of the students in the Fair-

field system simultaneously with re-admission of the

students who are involved under the motion.”

Under the Court’s order the re-admission was to take effect

on November 10, 1972. The tumult that had existed during

the boycott was continued on the tenth. Police officers had

to be called in to police the school.

After Beverly Claiborne had obtained her readmittance

slip from the counselor’s office she did not report to her

first period class with Mr. Craig, and on Monday when

she was informed that she had been expelled she used vile

and profane language in Mr. Turner’s (principal) pres

ence. She denied using the language but on cross-examina

tion she admitted that she made the statements “To myself.

I didn’t say it out loud, to myself I did, but not out loud.”

She also contended that she had been excused. The evi

dence sustained the charges against her.

Linda Meadows went to a room to which she was not

assigned and when instructed to leave cursed the teacher

in front of the class and then left. She denied using the

profane language. She admitted looking into the various