United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education Opinion

Public Court Documents

March 29, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education Opinion, 1967. a17a0f82-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8b47b583-55d6-428b-95b9-96e9975b9a24/united-states-v-jefferson-county-board-of-education-opinion. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

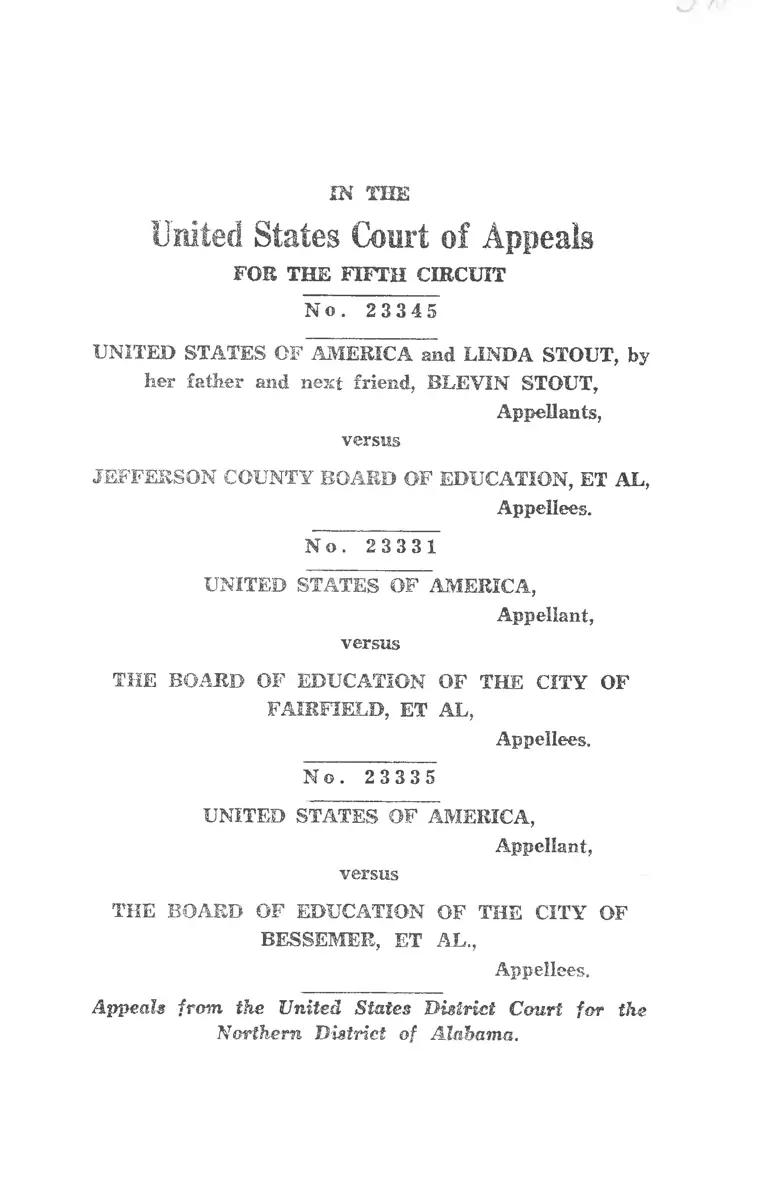

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH dRCUTT

N o . 2 3 3 4 5

UNITED STATES OF AIVIEKICA and LINDA STOUT, by

her father and next friend, BLEVIN STOUT,

Appellants,

versus

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL,

Appellees.

N o . 2 3 3 3 1

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant,

versus

THE BO^ABD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

FAIRFIELD, ET AL,

Appellees.

N o . 2 3 3 3 5

UNITED STATES OF AJWERICA,

Appellant,

versus

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

BESSEMER, ET AL.,

Appellees.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Alabama.

2 JJ. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

N o . 2 3 2 7 4

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant,

versus

CADDO PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL.,

Appellees.

N o . 2 3 3 6 5

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant,

versus

THE BOSSIER PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL.,

Appellees.

N o . 2 3 1 7 3

MARGARET M. JOHNSON, ET AL.,

Appellants,

versus

JACKSON PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL.,

Appellees.

U. S., et al . V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 3

N o . 2 3 1 9 2

YVORNIA DECAROL BANKS, ET AL.,

Appellants,

versus

CLAIBORNE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL.,

Appellees.

N o . 2 3 2 5 3

JIMMY ANDREWS, ET AL.,

Appellant,

versus

CITY OF MONROE, LOUISIANA, ET AL.,

Appellees.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Louisiana.

4 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

N o . 2 3 1 1 6

CLIFFORD EUGENE DAVIS, JK., ET AL.,

Appellants,

versus

e a s t b a t o n r o u g e PAIMSH SCHOOL BOARD, ET

AL.,

Appellees.

Appeal from ike United States District Cmirt for the

Eilstem District of Louisiana.

ON PETITIONS FOE REHEARING EN BANC

(March 29, 1967.)

Before TUTTLE, Chief Judge, BROWN, WISDOM,

GEWIN, BELL, THORNBERRY, COLEMAN, GOLD

BERG, AINSWORTH, GODBOLD, DYER, and SIMP

SON, Circuit Judges.

P E R CURIAM : 1. The Court sitting en banc

adopts the opinion and decree filed in these cases De

cem ber 29, 1966, sub ject to the clarifying statem ents

in th is opinion and the changes in the decree a ttached

to th is opinion.

2. School desegregation cases involve m ore than

a dispute betw een certa in Negro children and certain

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

schools. If N egroes a re ever to en ter the m a in s tream

of A m erican life, a s school children they m ust have

equal educational opportunities w ith w*hite children.

3. The Court holds th a t boards and officials ad,-

m in istering public schools in th is circuit^ have the af

firm ative duty under the F ourteenth A m endm ent

to b ring labout an in tegrated , unitary school system

in w hich th e re a re no Negro schools and no w hite

schools—^just schools. E xpressions in our ea rlie r opin

ions distinguishing between in teg ra tion and desegre

gation® m ust yield to th is affirm ative duty v/e now

recognize. In fulfilling th is duty it is not enough for

school au thorities to offer N egro children the oppor

tunity to a ttend fo rm erly all-White schools. The neces

sity of overcom ing the effects of the dual school sys

tem in th is c ircu it requ ires in tegration of faculties,

̂ “In the South”, as the Civil Rights Commission has pointed

out, the Negro “has struggled to get into the neighborhood school.

In the North, he is fighting to get out of it,” Civ. Rts. Comm. Rep.,

Freedom to the Free. 207 (1963).

This Court did not “excuse” neighborhood schools in the

North and West which have de facto segregation. No case involv

ing that sort of school system was before the Court.

School segregation is “inherently unequal” by any name and

wherever located. But de facto segregation resulting from resi

dential patterns in a non-racially motivated neighborhood school

system has problems peculiar to such a system. The school

system is already a unitary one. The difficulties lie in finding

state action and in determining how far school officials must go

and how far they may go in correcting racial imbalance. In such

cases Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) may turn out to be

as important as Brown. A broad-brush doctrinaire approach,

therefore, that Brown's abolition of the dual school system solves

all problems is conceptually and pragmatically inadequate for

dealing with de facto-segregated neighborhood schools.

We leave the problems of de facto segregation in a unitary

system to solution in appropriate cases by the appropriate courts.

2 This distinction was first expressed in Briggs v. Elliott,

E.D.S.C. 1955, 132 F. Supp. 776: “The Constitution, in other

words, does not require integration. It merely forbids discrimina

tion.”

6 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

facilities, and activ ities, as well as students. To the

extent th a t ea rlie r decisions of this Court (m ore in

the language of the opinion than in the effect of the

holding) conflict w ith th is view, th e decisions a re

overru led . We re fe r specifically to the cases listed

in footnote 2 of th is opinion.®

4. F reedom of choice is not a goal in itself. I t is a

m eans to an end. A schoolchild has no inalienable

righ t to choose h is school. A freedom of choice p lan

is bu t one of the tools availab le to school officials at

th is stage of the process of converting th e dual sys

tem of sep a ra te schools for N egroes and w hites into

a un ita ry system . The governm ental objective of this

conversion is—educational opportunities on equal

term s to all. The crite rion for determ ining the^ valid ity

of a provision in a school desegregation p lan is w heth

e r the provision is reasonab ly re la ted to accom plish

ing th is objective.

5. The percen tages re fe rred to in the Guidelines

and in this C ourt’s decree a re sim ply a rough ru le of

thum b for m easuring the effectiveness of freedom of

choice as a useful tool. The percen tages a re not a

m ethod for setting quotas or strik ing a balance. If the

p lan is ineffective, longer on prom ises th an p erfo rm

ance, the school officials charged w ith in itiating and

3 Avery v. Wichita Falls Independent School District, 1956, 241

F.2d 230; Borders v. Rippy, 1957, 247 F.2d 268; Rippy v. Borders,

1957, 257 F.2d 73; Cohen v. Public Housing Administration, 1958,

257 F.2d 73; City of Montgomery v. Gilmore, 1960, 277 F.2d 364;

Boson V. Rippy, 1960, 285 P.2d 43; Stell v. Savannah-Chatham

County Board of Education, 1964, 333 F.2d 55; Evers v. Jackson,

1964, 328 F.2d 408; Lockett v. Board of Education of Muscogee

County, 1965, 342 F.2d 225.

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 7

adm inistering a u n ita ry system have not m e t the con

stitu tional req u irem en ts of the F ourteen th A m end

m en t; they should try o ther tools.

6. In constructing the orig inal a n d rev ised decrees,

the C ourt gave g re a t w eight to the 1965 and 1966 HEW

Guidelines. These G uidelines estab lish m inim um

s tan d ard s c learly app licab le to d isestablishing state-

sanctioned segregation . These Guidelines and our de

cree a re w ithin the decisions of th is Court, com ply

w ith the le tte r and sp irit of the Civil R ights A ct of

1964, and m ee t the requirem ents of the U nited S ta tes

Constitution. Courts in th is c ircu it should give g rea t

w eight to fu tu re HEW G uidelines, when such guide

lines a re applicable to th is c ircu it and a re w ithin law

ful lim its. We express no opinion as to the applicabil

ity of HEW Guidelines in rac ia lly im balanced s itua

tions such as occur in som e o ther c ircu its w here it is

contended th a t s ta te action m ay be found in s ta te tol

erance of de facto segregation o r in such action as

the draw ing of a ttendance boundaries based on a

neighborhood school system .

The Court rea ffirm s the rev e rsa l of the judgm ents

below and the rem and of each case for en try of the

decree a ttached to th is opinion.

The m andate will issue im m ediately .

8 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

CORRECTED D EC R EE.

It is O RD ERED , ADJUDGED and D EC R EED th a t

the defendants, the ir agents, officers, employees and

successors and all those in ac tive concert and par

ticipation w ith them , be and they a re perm anently

enjoined from discrim inating on the basis of race O'r

color in the operation of the school system . As

set out m ore particu la rly in the body of the decree,

they ^ a l l take a ffirm ative action to d isestablish all

school segregation and to e lim inate the effects of the

dual school sy s te m :

I.

SP E E D OF DESEGREGATION

Com m encing w ith the 1967-68 school year, in ac

cordance w ith th is decree, all g rades, including kin

dergarten grades, shall be desegregiated and pupils

assigned to schools in these g rades w ithout reg a rd to

race or color.

II.

EX ERC ISE OF CHOICE

The following provisions Shall apply to all g rades:

(a) Who M ay E xercise Choice. A choice of schools

m ay be exercised by a p a re n t or o ther adult person

serv ing a s th e s tuden t’s parent. A studen t m ay ex er

cise his own choice if he (1) is exercising a choice

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 9

for the n inth o r a h igher g rade, or (2) has reached

the age of fifteen at the tim e of th e exercise of choice.

Such a choice by a s tuden t is controlling unless a dif

feren t choice is exercised for h im by his p a ren t or

other adu lt person serving as his p a re n t during the

choice period o r a t such la te r tim e as the studen t ex

erc ises a choice. E ach refe rence m th is decree to a

studen t’s exercising a choice m eans the exercise

of the choice, as appropria te , by a p a re n t o r such

o ther adult, o r by the studen t himseK.

(b) Annual E xerc ise of Choice. All students, both

white and Negro, shall be requ ired to exercise a free

choice of schools annually.

(c) Choice Period. The period for exercising

choice shall com m ence M ay 1, 1967 and end June 1,

1967, and in subsequent y ears shall com m ence M arch

1 and end M arch 31 preceding the school y ear for

which the choice is to be exercised. No studen t or

prospective student who exercises his choice w ithin

the choice period shall be given any preference be

cause of the tim e w ithin the period w hen such choice

w as exercised.

(d) M andatory E xercise of Choice. A failu re to

exercise a choice w ithin the choice period shall not

preclude any studen t from exercising a choice a t any

tim e before he com m ences school for the y ear w ith

respec t to w hich the choice applies, bu t such choice

m ay be subordinated to the choices of students who

exercised choice before the expiration of the choice

10 U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

period. Any studen t wiho h a s not exercised h is choice

of school w ithin a w eek a f te r school opens shall be

assigned to the school n e a re s t his hom e w here space

is available under s tan d a rd s for determ ining avail

ab le space w hich shall be applied uniform ly through

out the system .

(e) Public Notice. On or w ithin a w eek before

the date the choice period opens, the defendants shall

a rran g e for the conspicuous publication of a notice

describ ing the provisions of this decree in the new s

p ap er m ost generally c ircu lated in the com m unity.

The tex t of the notice shall be substantia lly s im ila r to

th e tex t of the explanatory le tte r sen t hom e to paren ts.

Pub lication as a legal notice will not be sufficient.

Copies of th is notice m u st also be given a t th a t

tim e to all rad io and television stations located in the

com m unity. Copies of th is decree shall be posted in

each school in the school system and a t the office of

the Superin tendent of Education.

(f) M ailing of E xp lanatory L e tters and Choice

Form s. On the firs t day of the choice period there

shall be d istribu ted by first-c lass m ail an exp lanatory

le tte r and a choice form to the p a ren t (or o th e r adult

person acting as paren t, if known to the defendants)

of each student, together w ith a re tu rn envelope ad

dressed to the Superintendent. Should th e defendants

satisfac to rily dem onstrate to the court th a t they a re

unable to com ply w ith the requ irem en t of distributing

the exp lanatory le tte r and choice form by first-class

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 11

m ail, they shall propose an alternative m'ethod which

will m axim ize individual notice, i.e., personal notice

to p a ren ts by delivery to the pupil w ith adequate pro

cedures to insure the delivery of the notice. The text

for the exp lanatory le tte r and choice fo rm shall es

sen tia lly conform to the sam ple le tte r and choice

form appended to th is decree.

(g) Extra Copies of the Explanatory Letter and

Choice Form . E x tra copies of the exp lanato ry le tte r

and. choice fo rm shall be free ly available to paren ts,

students, prospective students, and the general public

a t each school in the system and a t the office of the

Superintendent of E ducation during the tim es of the

y e a r w hen such schools a re usually open.

(h) Content of Choice Form . E ach choice form

shall se t fo rth the nam e and location and the g rades

offered a t each school and m ay req u ire of the person

exercising the choice the nam e, address, age of s tu

dent, school and grade currently or m ost recen tly a t

tended by the student, the school chosen, the signa

tu re of one p a ren t or other adult person serv ing as

paren t, or w here appropria te the s ignatu re of the stu

dent, and the identity of the person signing. No state

m en t of reasons for a p a rticu la r choice, o r any o ther

inform ation, or any w itness or other authentication,

m ay be requ ired or requested , w ithout approval of

the court.

(i) R eturn of Choice Form . A t the option of the

person com pleting the choice form , the choice m ay

12 U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

be re tu rn ed by m ail, in person, o r by m essenger to

any schoo'l in the school system or to the office of the

Sup er in tenden t.

(j) Choices not on O fficial Form . The exercise of

choice m ay also be m ade by the' subm ission in like

m an n er of any other w riting w hich contains in fo rm a

tion sufficien t to identify the studen t and indicates

th a t h e h a s m ad e a choice of school.

(k) Choice F orm s Binding. W hen a choice form

has once been subm itted and the choice period has ex

pired , the choice is binding for the en tire school year

and m ay not be changed except in cases of paren ts

m aking d ifferen t choices from th e ir children under

the conditions se t fo rth in p a ra g rap h II (a) of th is

decree and in exceptional cases w here, absen t the

consideration of race, a change is educationally

called fo r or w here com pelling hardsh ip is shown by

the student. A change in fam ily residence from one

neighborhood to ano ther shall be considered an ex

ceptional case for purposes of th is p a rag rap h .

(l) P reference in A ssignm ent. In assigning stu

dents to schools, no p re fe ren ces shall be given to any

student fo r p rio r attendance a t a school and, except

w ith the approval of court in ex trao rd in ary c ircum

stances, no choice shall be denied fo r any reason other

than overcrow ding. In case of overcrowding' at any

school, p reference shall be given on the basis of the

proxim ity of the school to the hom es of the students

choosing it, w ithout reg a rd to race or color. S tandards

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al . 13

for determ ining overcrovv^ding ahall be applied uni

form ly throughout the system .

(m ) Second Choice w here F irst Choice is Denied.

Any student whose choice is denied m u st be prom ptly

notified in w riting and given h is choice of any school

in the school system serving h is g rade level w here

space is available. The studen t shall have seven days

from the receip t of notice of a denial of f irs t choice in

which to exercise a second choice.

(n) Transportation. W here tran spo rta tion is gen

erally provided, buses m u st be routed to the m ax i

m um extent feasib le in ligh t of the geographic d is tri

bution of students, so as to serve each studen t choos

ing any school in tlie system . E very student choosing

either the fo rm erly w hite o r the fo rm erly Negro

school n ea res t his residence m ust be transpo rted to

the school to w hich he is assigned under these pro

visions, w hether or not it is his f irs t choice, if that

school is sufficiently d is tan t from his hom e to m ake

him eligible for transpo rta tion under generally appli

cable transpo rta tion rules.

(o) O fficials not to Influence Choice. At no tim e

shall any official, teacher, or em ployee of the school

system influence any paren t, o r o ther adult person

serving as a paren t, or any student, in the exercise

of a choice or favor or penalize any person because of

a choice m ade. If the defendant school board em

ploys professional guidance counselors, such persons

shall base their guidance and counselling on the in

dividual s tuden t’s p a rticu la r personal, academ ic,

14 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

and vocational needs. Such guidance and counselling

by te ach e rs as well as professional guidance counsel

lors shall be available to a ll s tuden ts w ithout regard

to race o r color.

(p) Protection of Persons E xercising Choice. W ith

in th e ir authority school officials a re responsible for

the pro tection of persons exercising righ ts under or

otherw ise affected by th is decree. They shall, w ithout

delay, tak e app rop ria te action w ith re g a rd to any stu

dent or staff m em b er who in te rfe res w ith the success

ful operation of the plan. Such in terference shall in

clude harassm en t, in tim idation, th rea ts , hostile words

or acts, and s im ila r behavior. The school board shall

not publish, allow, or cause to be published, the nam es

or add resses of pupils exercising righ ts o r otherwise

affected by th is decree. If officials of the school sys

tem a re not able to provide sufficient protection, they

shall seek w hatever assistance is necessary from

other app ro p ria te officials.

III.

PRO SPECTIV E STUDENTS

E ach prospective new studen t shall be requ ired to

exercise a choice of schools before or a t the tim e of

enrollm ent. All such studen ts known to defendants

shall be fu rn ished a copy of the p rescribed le tte r to

parents, and choice form , by m ail or in person, on

the d a te the choice period opens or as soon th e rea fte r

as the school system learns th a t he p lans to enroll.

U. S., et al. V. Jejj. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 15

W here th e re is no p re-reg istra tion p rocedure for new

ly entering students, copies of the choice fo rm s shall

be availab le a t the Office of the Superintendent and

a t each school during the tim e the school is usually

open.

IV.

TRA N SFERS

(a) Transfers for S tudents. Any student shall

have the righ t a t the beginning of a new te rm , to

tran sfe r to any school from w hich he w as excluded or

would otherw ise be excluded on account of his race or

color.

(b) Transfers for Special Needs. Any student

who requ ires a course of study not offered a t the

school to which he h as been assigned m ay be p e rm it

ted, upon h is w ritten application, a t the beginning of

any school te rm or sem ester, to tran sfe r to another

school which offers courses for his special needs.

(c) Transfers to Special Classes or Schools. If

the defendants operate and m ain ta in special classes

or schools fo r physically handicapped, m en ta lly re

tarded , o r gifted children, the defendants m ay assign

children to such schools or classes on a basis related

to th e function of the special class or school th a t is

o ther than freedom of choice. In no event shall such

assignm ents be m ade on the basis of race or color or

in a m an n er whidh tends to perpetuate a dual school

system based on race or color.

16 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

V.

SERVICES, FACILITIES, ACTIVITIES AND PRO

GRAMS

No studen t shall be seg rega ted or d iscrim inated

against on account of race o r color in any service,

facility , activ ity , or p rog ram (including tran sp o rta

tion, a th le tics , or o ther ex tracu rricu la r activ ity) that

m ay be conducted or sponsored by th e school in which

he is enrolled. A studen t attending school for the firs t

tim e on a desegregated basis m ay not be sub jec t to

any disqualification or w aiting period for p a rtic ip a

tion in activities and p rog ram s, including athletics,

w hich m igh t otherw ise app ly because he is a tran sfe r

or new ly assigned studen t except .that such tra n s

ferees shall be subject to longstanding, non-racially

based ru les of city, county, or s ta te athletic associa

tions dealing w ith the eligibility of tran sfe r students

for athletic contests. All school use or school-spon

sored use of ath letic fields, m eeting room s, and all

o ther school re la ted services, facilities, activities, and

p ro g ram s such as com m encem ent exercises and p a r

ent-teacher m eetings which a re open to persons other

th an enrolled s tuden ts, shall be open to all persons

w ithout reg ard to race or color. All special education

al p ro g ram s conducted by the defendan ts shall be

conducted w ithout reg a rd to. ra c e or color.

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd.. of Educ., et al. 17

VI.

SCHOOL EQUALIZATION

(a) In ferior Schools. In schools heretofore m ain

ta ined for Negro students, the defendants shall take

prom pt steps necessa ry to provide physical facili

ties, equipm ent, courses of instruction, and instruc

tional m aterials of quality equal to th a t provided in

schools previously m ain ta ined for w hite students.

Conditions of overcrow ding, as de term ined by pupil-

teacher ra tios and pupil-classroom ratios shall, to the

extent feasible, be d istribu ted evenly betw een schools

fo rm erly m ain ta ined for Negro students and those

form erly m aintained for w hite students. If for any

reason i t is not feasible to im prove sufficiently any

school form erly m aintained for Negro students, w here

such im provem ent would otherw ise be requ ired by

this p a rag rap h , such school shall be closed as soon

as possible, and students enrolled in the school

shall be reassigned on the basis of freedom of choice.

By October of each year, defendants shall rep o rt to

the Clerk of the Court pupil-teacher ra tios, pupil-class

room ratios, and per-pupil expenditures both as to

opera ting and capital im provem ent costs, and shall

outline the steps to be taken and the tim e within

which they shall accom plish the equalization of such

schools.

(b) R em ed ia l Program s. The defendants shall p ro

vide rem ed ial education p rog ram s which p e rm it s tu

dents attending or who have previously attended seg-

18 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

regated schools to overcom e past inadequacies in

th e ir education.

VII.

NEW CONSTRUCTION

The defendants, to the extent consistent w ith the

p roper operation of the school system as a whole,

shall locate any new school and substan tia lly expand

any existing schools w ith the objective of ©radicating

the vestiges of the dual system .

VIII.

FACULTY AND STAFF

(a) F aculty E m ploym en t. R ace or color shall not

be a fac to r in the hiring, assignm ent, reassignm ent,

prom otion, demotion, or d ism issal of teach ers and

other professional staff m em bers, including student

teachers, except th a t race m ay be tak en into ac

count for the purpose of counteracting or correcting

the effect of the segregated assignm ent of facu lty and

staff in the dual system . Teachers, p rincipals, and

staff m em bers shall be assigned to schools so th a t the

faculty and staff is not com posed exclusively of m em

bers of one race. W herever possible, te ach e rs shall

be assigned so th a t m ore th an one teach e r of the m i

nority race (white or Negro) shall be on a desegre

gated faculty . D efendants shall take positive and af

firm ative steps to accom plish the desegregation of

their school faculties and to achieve substan tia l de-

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 19

segregationi of faculties in as m any of the schools as

possible for the 1967-68 ischool y e a r notw ithstanding

th a t teacher con tracts for the 1967-68 or 1968-69 school

y ears m ay have a lready been signed and approved.

The tenure of teachers in the system shall not be used

as an excuse for fa ilu re to com ply w ith th is provision.

The defendants shall estab lish as an objective tha t

the p a tte rn of teach er assignm ent to any p articu la r

school not be identifiable as ta ilo red for a h eav y con

centration of e ither Negro or white pupils in the

school.

(b) D ism issals. T eachers and other professional

staff m em bers m ay not be d iscrim inatorily assigned,

dism issed, dem oted, or passed over for retention,

prom otion, or reh iring , on the ground of race or color.

In any instance w here one or m ore teachers o r other

professional staff m em bers are to be d isplaced as a

resu lt of desegregation, no staff vacancy in the school

system shall be filled through rec ru itm en t from out

side the system unless no such displaced staff m em

ber is qualified to fill the vacancy. If, as a resu lt of

desegregation, there is to be a reduction in the to tal

professional staff of the school system , the qualifica

tions of all staff m em bers in th e syshetrL-shaU.,bemiial--

ua ted in selecting the staff m em ber to be released

w ithout consideration of race or color. A repo rt con

taining any such proposed dism issals, and the re a

sons therefor, shall be filed w ith the Clerk of tiie

Court, serving copies upon opposing counsel, w ithin

five (5) days a fter such dism issal, demotion, etc., as

proposed.

20 U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

(c) P ast A ssignm ents. The defendants shall take

steps to assign and reass ig n teachers and other p ro

fessional staff m em bers to elim inate the effects of

the dual school system .

IX.

B EPO R TS TO THE COURT

(1) R eport on Choice Period. The defendants

shall serve upon the opposing p a rtie s and file w ith the

C lerk of tihê Court on or before A pril 15, 1967, and on

or before June 15, 1967, and in each subsequent year

on o r before June 1, a rep o rt tabu la ting by race the

num ber of choice applications and tran sfe r applica

tions received for enrollm ent in each g rad e in each

school in the system , and the' num ber of choices and

transfers granted and the num ber of denials in each

grade of each school. The report shall also s ta te any

reasons re lied upon in denying choice and shall tab

ulate , by school and by race of student, the num ber

of choices and transfers denied for each such reason.

In addition, the rep o rt shall show the percen tage

of pupils actually tra n sfe rre d or assigned from seg-

re giite d : g r a d e s o r tô .schools a ttended predom inantly

by puphs of \a race other than the race of the appli

cant, for a ttendance during the 1966-67 school year,

w ith com parable da ta for the 1965-66 school year.

Such additional inform ation shall be included in the

rep o rt served upon opposing counsel and filed w ith

the Clerk of the Court.

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 21

(2) R eport A fter School Opening. The defend

ants shall, in addition to repo rts elsew here described,

serve upon opposing counsel and file w ith th e Clerk

of th e C ourt w ithin 15 days a fte r the opening of

schools for the fa ll sem este r of each y ear, a rep o rt

setting fo rth the following inform ation:

(i) The nam e, address, g rade, school of

choice and school of present a ttendance of

each studen t who h as w ithdraw n or requested

w ithdraw al of h is choice of school o r who has

tra n s fe rre d a fte r the s ta r t of the school year,

together w ith a description of any action taken

by the defendants on his request and the re a

sons therefor.

(ii) The num ber of facu lty vacancies, by

school, th a t h av e occu rred o r been filled

by the defendants since the order of th is Court

o r the la te s t rep o rt subm itted pursuan t to this

sub-paragraph . This rep o rt shall state the race

of the te ac h e r em ployed to fill each such va

cancy landi indicate w hether such te ach e r is

newly em ployed or w as tra n s fe rre d from With

in the system . The tabu la tion of the num ber of

tra n s fe rs w ithin the system shall indicate the

schools from which and to w hich the tra n s fe rs

w ere m ade. The rep o rt shall also se t fo rth the

num ber of facu lty m em bers of each race a s

signed to each school for the cu rren t year.

(iii) The num ber of students by race,

each g rad e of each school.

in

22 17. S., et al. v. Jejj. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

EXPLANATORY LE TT ER

(School System N am e an d Office A ddress)

(D ate Sent)

D ear P aren t:

All g rad es in our school system will be desegre

gated nex t year. Any studen t who will be en tering

one of these g rades nex t year m ay choose to attend

any school in our system , reg ard less of w hether th a t

school w as fo rm erly all-white or all-Negro. I t does

not m a tte r w hich school your child is a ttending th is

year. You and your child m ay select any school you

wish.

E v ery student, w hite and Negro, m u st m ake a

choice of schools. If a child is entering the n in th or

h igher g rade , o r if the child is fifteen years old or old

er, he m ay m ake the choice him self. O therw ise a p a r

ent o r o ther ad u lt serving as p a re n t m u st sign the

choice form . A child enrolling in the school sy stem for

the f irs t tim e m u st m ake a choice of schools before or

at the tim e of his enrollm ent.

The fo rm on w hich th e choice should be m ade is a t

tach ed to th is le tte r. I t should be com pleted and re

tu rned by Ju n e 1, 1967. You m ay m ail it in the en

closed envelope, or deliver it by m essenger or by

hand to any school p rinc ipal or to the Office of the

Superintendent a t any tim e betw een M ay 1 and June

1. No one m ay requ ire you to re tu rn your choice form

before Ju n e 1 an d no p reference is given for re tu rn

ing th e choice fo rm early .

U. S., e t a l . V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et a l . 23

No principal, teacher or o ther school official is p e r

m itted to influence anyone in m aking a choice or to

requ ire early re tu rn of the choice form . No one is p e r

m itted to favo r or penalize any studen t or o ther p e r

son because of a choice m ade. A choice once m ade

cannot be changed except for serious hardship .

No child will be denied his choice unless fo r re a

sons of overcrow ding a t the school chosen, in which

case children living n ea res t the school will have p re f

erence.

T ransporta tion will be provided, if reasonably pos

sible, no m a tte r w hat school is chosen. [Delete if the

school system does not provide transporta tion .]

Y our School B oard an d the school staff w ill do

everything w e can to see to i t th a t the rig h ts of all

students a re pro tected and th a t desegregation of our

schools is carried out successfully.

Sincerely yours,

Superintendent.

CHOICE FORM

This fo rm is provided for you to choose a school for

your child to a ttend next year. You have 30 d ay s to

m ake your choice. It does not m atte r w hich school

your child attended la s t y ear, and does not m a tte r

w hether the school you choose w as fo rm erly a w hite

or Negro school. This fo rm m ust be m ailed or brought

24 17. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

to th e p rinc ipa l of any school in the system or to the

office of the Superintendent, [address], by June

1, 1967. A choice is req u ired for each child.

Name of c h i ld ..............................................................................

(Last) (First) (Middle)

A d d ress ..........................................................................................

N am e of P a re n t or o ther

adult serving as parent .............................................................

If child is entering f irs t g rade, date of b irth :

(Month) (Day) (Year)

G rade child is entering . . .

School attended la s t y ea r

Choose one of the following schools by m ark ing an X

beside the nam e.

N am e of School G rade Location

Signature

Date

To be filled in by Superintendent:

School Assigned .

1 In subsequent years the dates in both the explanatory letter

and the choice form should be changed to conform to the choice

period.

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 25

GEWIN, C ircuit Judge, w ith whom Judge Bell con

curs, DISSENTING:

The opinioh of the m a jo rity and the proposed de

cree a re long, com plicated, som ew hat am biguous

and ra th e r confusing. The p e r cu riam opinion of the

m ajo rity of the en banc court does not substantia lly

clarify , m odify o r change anything said in the orig

inal opinioh filed D ecem ber 29, 1966. Only m inor and

inconsequential changes w ere m ad e in the proposed

decree.^ In m y view both the opinion and decree con

stitu te an ab ru p t and unauthorized dep artu re from

the m a in s tream of jud ic ia l thought both of this C ir

cuit and a hum ber of o ther C ircuits. I am unable to

ag ree e ither w ith the opinion or the decree, e sp e

cially those provisions dealing w ith the following: (1)

de facto and de ju re segregation ; (2) the guidelines;

(3) the proposed decree; (4) a ttendance percen tages,

proportions, and freedom of choice; and (5) enforced

in tegratioh .

De Facto and De jure Segregation

The thesis of the m ajo rity , lik,e M inerva (A thena)

of the classic m yths,^ w as spaw ned full-grown and

̂ “The opinion” and “the decree” as used herein refer to the

opinion and decree filed in these cases by the three judge

panel on December 29, 1966, wherein two of the judges agreed

and one dissented. Of necessity, references to page numbers

of the opinion refer to the slip opinion.

̂ See Gayley, The Classic Myths, (Rev. ed. 1939) page 23

“She sprang from the brain of Jove, agleam with panoply

of war, brandishing a spear and with her battle-cry

awal^ening the echoes of heaven and earth,”

26 U. S., et a l . V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et a l .

fu ll-arm ed. I t h as no su b stan tia l legal ancestors.®

We m u st w a it to see w h a t progeny it will produce.

While professing to fashion a rem edy under the

benevolent canopy of the F ed era l Constitution, the

opinion and the decree a re couched in divisive te rm s

and proceed to dichotom ize the union of s ta tes into

two sep ara te and d istinc t p a rts . B ased on such re a

soning the Civil R ights A ct of 1964 is s tripped of its

national ch arac te r, the national policies there in

s ta ted a re nullified, and in effect, the rem edial p u r

poses of the A ct a re held to apply to approx im ately

one-third of the s ta tes of the union and to a m uch

sm alle r p e rcen tage or proportion of the to ta l popu

lation of the country. I am unable to believe th a t

the Congress had any such in tent. If it did, a serious

constitu tional question would be p resen ted as to the

valid ity of the en tire A ct under our concepts of A m er

ican constitu tional governm ent.

The Negro children in Cleveland, Chicago, Los

Angeles, Boston, New York, o r in any o ther a re a of

the nation w hich the opinion classifies u n d e r de facto

segregation , would receive little com fort from the a s

sertion th a t the ra c ia l m ake-up of th e ir school system

does not vio late their constitu tional righ ts because

® However, compare the doctrine of the majority and the

theme of an article in the Virginia Law Review entitled “Title

VI, The Guidelines and School Desegregation in the South”,

by James R. Dunn. Virginia Law Review, Vol. 53, page 42

(1967). According to footnote 85 of the law review article,

the majority opinion was released “as this article was going

to press.” Mr. Dunn is Legal Adviser, Equal Educational

Opportunities Program, United States Office of Education,

HEW, Washington, D.C.

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 27

they w ere born into a de facto society, w hile the

exact sam e ra c ia l m ake-up of the school system in

the 17 Southern and bo rder s ta tes vio lates the con

stitu tional righ ts of th e ir coun terparts, o r even their

blood b ro thers , because they w ere born into a de ju re

society. All ch ildren everyw here in the nation a re

p ro tec ted by the Constitution, and tre a tm e n t which

violates their constitu tional righ ts in one a re a of the

country, also v iolates such constitu tional rig h ts m

ano ther a rea . The details of the rem ed y to be applied,

how ever, m ay v a ry w ith local conditions. B asically ,

a ll of them m u st be given the sam e constitutional

protection. Due process and eq u al pro tection will not

to le ra te a low er standard , and su re ly not a double

s tandard . The prob lem is a na tional one.

R egard less of our decrees, in spite of our hopes and

notw ithstanding our disappointm ents, th e re is no in

fallible and certa in process of a lchem y w hich will

e rase decades of h isto ry and tran sm u te a d istastefu l

set of c ircum stances into a utopia of perfection. All

who have studied the sub jec t recognize th a t d iscrim

inato ry p rac tices did not a rise from a single cause.

Such p rac tices had th e ir origin and b irth in social,

economic, educational, legal, geographical and nu

m erous o ther considerations. These fac to rs tend to

be self-perpetuating. We m u st e rad ica te them , and I

have the fa ith th a t they will be e rad ica ted and elim

inated by responsible and responsive governm ental

agencies acting p u rsuan t to the best in te rests of the

com m unity. There is no social antibiotic w hich will

28 U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

effect a sudden or overnight cure. I t is not possible

to specifically fix the b lam e or to a ttrib u te the origin

of d iscrim inato ry p rac tices to isolated causes, and

it is su re ly inappropria te to undertake to fa s ten guilt

upon ahy segm ent of the population. In th is a re a of

our n a tion ’s h istory em inent histo*rians still dis

ag ree as to causes and effects. Some studies have

p laced em phasis on the slave tra d e r or the im porter

of slaves, o thers have b lam ed the slave holder, while

o thers have tried to tra ce the guilt back to trib a l

ch ieftans in A frica. P e rh a p s the m ost com m on under

standing am ongst all the h isto rians and students of

the problem is the conclusion th a t causes cannot be

isolated and responsibility cannot be lim ited to a p a r

ticu la r group. W hatever the cause or explanation, it

is c lea r th a t the responsibility rests on m ahy ra th e r

than few.

A t th is tim e, a lm ost 13 y e a rs a fte r the decisions in

Brow n v. Board of Education (1954) 347 U.S. 483, 98

L.ed. 873 (Brow n I) and Brow n v. Board of Education

(1955) 349 U.S. 294, 99 L.ed. 1083 (Brown II), there

should be no doubt in the m inds of anyone th a t com

pulsory segregation in the public school system s of

this nation m ust be elim inated. Negro ch ildren have

a personal, p resen t, and unqualified constitutional

rig h t to a ttend the public schools on a rac ia lly non-

d iscrim inato ry basis.

A lthough espousing the cause of un iform ity and a s

serting th e re m u st not be one law fo r A thens and

ano ther for Rom e, the opinion does Pot follow th a t

thesis o r principle. One of the chief difficulties

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 29

w hich I encounter w ith the opinion is th a t it con

cludes th a t the Constitution m ean s one thing in 17

s ta tes of the nation and som ething else in the rem ain

ing sta tes. This is done by a ra th e r ingenious though

illogical distinction between the te rm s de facto seg

regation and de ju re segregation. While the opinion

recognizes the evils com m on to both types, it relies

heavily on background fac ts to justify the conclusion

th a t the evil will be corrected in one a re a of the n a

tion and not in the other. In m y view the Constitution

cannot be bent and tw isted in such a m an n er as to

justify or support such an incongruous result. The

very subj ect m a tte r under consideration tends to nul

lify the assertion th a t the constitutional prohibition

against segregation should be applied in 17 s ta tes

and not in the re s t of the nation.

Legislative h istory c learly supports the idea th a t

no distinction should be m ade v/ith respect to the

various s ta tes in dealing w ith the problem . Senator

P asto re w as one of the p rincipal spokesm en who

handled this legislation. He gave the follov/ing ex

planation:

“ F ran k ly I do not see how we could have

gone any fu rther, to be fa ir . . . Section 602

of Title VI, not only requ ires the agency to

p rom ulgate rules and regulations, but all

p rocedure m u s t be in accord w ith these

ru les and regulations. They m ust have

broad scope. They m ust be national. They

m ust apply to all fifty states. We could not

30 U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

draw one ru le to apply to the S ta te of M issis

sippi, ano ther ru le to apply to the S ta te of

A labam a, and ano ther ru le to apply to the

S ta te of Rhode Island. T here m u st be only one

ru le , to apply to every s ta te . F u rth e r, the

P resid en t m u s t approve the ru le .” (110 Cong.

Rec. 7059, A pril 7, 1964)

“ MR. PASTORE. . . We m ust do w hat Title

VI p rovides; and we could do it in no m ilder

fo rm th an th a t now provided by Title VI. The

Senator from Tennessee says, ‘Let us read

th is title ’. I say so, too. W hen we read these

two pages, we understand th a t the whole phil

osophy of T itle VI is to prom ote volun tary

com pliance. I t is w ritten righ t in the law.

T here shall be the volun tary com pliance as

the firs t step, and then the second step they

m u st inaugura te and prom ulgate , ru les th a t

have a national effect, not a local effect.

They shall apply to Tennessee, to Louisiana,

to Rhode Island, in equal fash ion .” (110 Cong.

Rec. 7066, A pril 7, 1964)

In connection w ith the distinction w hich the opin

ion undertakes to m ake, it is p e rtin en t to observe the

following strong and unequivocal pronouncem ent in

the v e ry beginning of the decision in Brown II:

“All provisions of federal, sta te , or local law

requiring or perm itting such discrim ination

m u st yield to this principle. T here rem ains

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 31

for consideration the m anner in w hich relief

is to be accorded .” (E m phasis added) (page

298)

It should be observed th a t all public school seg reg a

tion w as de ju re in the b road sense of th a t te rm p ri

or to the f irs t Brown decision, in th a t segregation

w as perm itted , if not required , by law.

It is undoubtedly tru e th a t any problem which

reaches national proportions is often generated by

vary ing and different custom s, m ores, laws, habits

and m anners. Such differences in the causes which

contributed to the creation and existence of the

p roblem in the firs t instance, do not justify the appli

cation of a fundam ental constitutional princip le in

one a re a of the nation and a fa ilu re to apply it in an

other.

While all the au thorities recognize the existence

and operation of d ifferent causes in the h isto rica l

background of rac ia l segregation, th e re a re also

m ark ed sim ilarities. This fac t is noted in the recen t

ly re leased study by the U nited S tates Com m ission

on Civil R ights, RACIAL ISOLATION IN THE

SCHOOLS, 1967, Vol. I (pp. 39, 59-79). In discussing

the sub ject the following observation is m ade early

in the re p o r t;

“ Today it [racia l isolation or segregation]

is a ttrib u tab le to rem nan ts of the dual school

system , m ethods of studen t assignm ent, re s

idential segregation, and to those discretion-

32 U. S., et al . V. Jejf. County Bd. of Educ., et al .

a ry decisions fam ilia r in the North—site se

lection, school construction, tran sfe rs , and

the determ ination of w here to p lace students

in the event of overcrow ding.” (E m phasis

added)

In its su m m ary the Comimissien notes th a t the causes

of rac ia l isolation or school segregation a re com

plex and self-perpetuating. I t speaks of the N ation 's

m etropolitan a reas and re fe rs to social and eco

nomic fac to rs as well as geographical ones. A ccord

ing to the sum m ary , not only do sta te and local gov

ernm ents sh are the blam e, it is ca tegorica lly a sse rt

ed th a t “ The Federal G overnm ent also sh ares in

this responsib ility .” (E m phasis added) P e rtin en t

s im ilarities in the problem , applicable to the en tire

nation, a re forcefully a sse rted in the final sentence

of the Com m ission’s. S u m m ary ;

“In the North, w here school segregation w as

not generally com pelled by law, these [dis

crim inatory] policies and p rac tices have

helped to increase rac ia l separation . In the

South, w here until the Brown decision in 1954

school segregation w as requ ired by law, s im

ilar policies and practices have contributed to

its perp e tu a tio n .” (E m phasis added)

By a process of syllogistic reasoning based on fa

tally defective m ajo r p rem ises the opinion has dis

to rted the m eaning of the te rm segregation and has

segm ented its m eaning into de facto and de ju re seg

regation. All segregation in the South is classified as

17. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 33

de jure^ while segregation in the N orth is classified

as de facto. D ifferent ru les apply to the different

types of segregation. The South is heavily con

dem ned. The opinion approaches the p roblem on a

sectional basis and fails to consider the sub jec t ex

cept on a sectional or regional basis. T here a re m any

references to “ the eleven” Southern s ta te s and “ the

seven” border sta tes. This a re a of the nation is v a ri

ously ch arac te rized as “The eleven s ta tes of the Con

federacy ,” “ the en tire region encom passing the

southern and border s ta te s” , “w earing the badge of

s lav e ry ” , and “ a rp a rth e id ” . F inally , the opinion

concludes th a t the two types of segregation a re dif

ferent, have different origins, c rea te different

p roblem s and requ ire d ifferent corrective action. It

is suggested th a t there is no p resen t rem edy fo r de

facto segregation but th a t the problem s and questions

arising from de facto segregation m ay som eday be

answ ered by the Suprem e Court.®

* At one place in the opinion pseudo de facto segregation in

the South is mentioned, but it is asserted that any similarity

between pseudo de facto segregation in the South and actual

de facto segregation in the North is more apparent than real

(p. 68)

® The case of Blocker v. Ed. of Educ. of Manhasset, N.Y. (E.D.

N.Y. 1964) 226 F. Supp. 208 cited and relied on by the ma

jority does not support the de facto-de jure distinction. In

fact Judge Zavatt disavows any such distinction. The fol

lowing is from the opinion:

“On the facts of this case, the separation of the Negro

elementary school children is segregation. It is segre

gation by law—the law of the School Board. In the light

of the existing facts, the continuance of the defendant

Board’s impenetrable attendance lines amounts to nothing

less than state imposed segregation.”

* * 4 :

“This segregation is attributable to the State. The

prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment ‘have refer

ence to actions of the political body denominated a State,

by whatever instruments or in whatever modes that ac-

34 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

This Court, and the d is tr ic t courts w ithin the six

s ta tes em b raced w ith in ou r ju risd iction like m any

o ther fed era l courts of the nation have given m uch

tim e and a tten tion to the solution of the problem s

aris ing a fte r the Brown decisions. M uch has been a c

com plished, m uch rem ain s to be done. It is not pos

sible fo r m e to jo in in the expressions of pessim ism

contained in the opinion or to approve the insinua

tions th a t the courts have failed in the perfo rm ance

of th e ir duty.® E ven Congress is tak en to ta sk for

fa ilu re to ac t e a r lie r and fo r fa ilu re to recognize

tion may be taken. * * *Whoever, by virtue of public

position under a State government, * * ♦ takes away the

equal protection of the laws, violates the constitutional

inhibition; and as he acts in the name and for the State,

and is clothed with the State’s power, his act is that of

the State.’ Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 346-347, 25

L.Ed. 676,679 (1880). ‘The situation here is in no dif

ferent posture because the members of the School Board

and the Superintendent of Schools are local officials;

from the point of view of the Fourteenth Amendment,

they stand in this litigation as the agents of the State.’

Cooper V. Aaron, supra, 358 U.S. at 16, 78 S.Ct. at 1408,

3 L.ed.2d 5.”

® See for example the following statements from the opinion:

“The courts acting alone have failed.’’ (p. 7)

* * *

“Quantatively, the results were meager.’’ (p. 20-21)* * *

“And most judges do not have sufficient competence—

they are not educators or school administrators—to

know the right questions, much less the right answers.”

(p. 24)

♦ * ♦

“In some cases there has been a substantial time-lag be

tween this Court’s opinions and their application by

the district courts. In certain cases—^which we consider

unnecessary to cite—there has even been a manifest

variance between this Court’s decision and a later dis

trict court decision. A number of district courts still

mistakenly assume that transfers imder Pupil Placement

Laws—superimposed on unconstitutional initial assign

ment—satisfy the requirements of a desegregation plan,”

(p. 36)

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 35

school desegregation “ as the law of the lan d ,” ̂ In

the Brown cases the Court c learly and w isely recog

nized the fa c t th a t those decisions had changed the

law w hich had been in effect for decades. Due notice

w as taken of the fa c t th a t the new o rd e r of the day

would “ involve a varie ty of local problemjs.” The

court recognized “ the conaplexities arising from the

transition to a system of public educatioh freed of

rac ia l d iscrim ination .” M oreover, the C ourt stated ,

“ F ull im plem entation of these constitutional p rinc i

ples m ay requ ire solution of varied local school p rob

lem s.” The courts w ere instructed to be “ guided by

equitable p rinc ip les ,” to give consideration to “ p ra c

tical flexibility in shaping rem ed ies” and observed

th a t equity courts have a pecu liar “ facility for ad

justing and reconciling public and p riv a te needs.”

The Brown decisions em phasized the concept th a t

courts of equity a re p a rticu la rly qualified to shape

such rem edies as would “ call for elim ination of a

v a rie ty of obstacles in m aking the transition to

school system s operated in accordance w ith the con

stitutional p rinc ip les” pronounced in the firs t Brown

decision. C ontrary to the tone and expressions of the

m ajo rity opinion, the Suprem e Court early announced

the policy of heavy reliance on the d istric t courts and

tha t policy has continued to this date.

’’ See item (5), page 24 of the opinion:

“(5) But one reason more than any other has held

back desegregation of public schools on a large scale.

This has been the lack, until 1964, of effective congres

sional statutory recognition of school desegregation as

the law of the land.”

36 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

II

Guidelines

W ith re sp ec t to the guidelines, it should be noted

th a t they w ere not an issue p resen ted to the D istric t

Court. The cases h e re involved had been tried in the

respective d is tric t courts, appeals tak en to th is Court

and w ere pending on the docket of this Court before

the 1966 Guidelines w ere p rom ulgated . G uidelines

w ere not m ade an issue by the p leadings or otherw ise

in the d is tric t courts and no evidence w as taken w ith

respect to them . The issue of the guidelines a re be

fore th is Court because the Court, sua sponte,

brought the issue before it.** In m y v iew their valid

ity is not an issue to be decided in th is Court. See

United S ta tes v. Petrillo (1947) 332 U.S. 1,5,6; United

S ta tes V. International Union (1957) 352 U.S. 567,590;

ConnoT V. N ew Y o rk T im es (5 Cir. 1962) 310 F.2d 133,

135; Gibbs v. B lackw ell (5 Cir. 1965) 354 F.2d 469,471.

In its f irs t approach to the question the C ourt in

d icated th a t it would not p ass upon the constitu tional

ity of the guidelines bu t would give w eight to or rely

upon them as a m a tte r of jud icia l policy. When con-

® See opinion, page 10, footnote 13.

It should be noted that v/hen the panel which originally

heard this case invited briefs no mention was made of any

constitutional question or issue with respect to the HEW

guidelines. Rather, the questions posed related to whether

it was “permissible and desirable” for the court to give

weight to or rely on the guidelines; and if so, what practical

means or methods should be employed in making use of the

guidelines. From the questions raised by the court, counsel

could not have gained the impression that the court was to

make a full scale determination of the constitutional ques

tions involved.

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 37

fronted w ith the fa c t th a t the guidelines w ere not ap

proved by the P resid en t a s req u ired by the Civil

R ights A ct of 1964, the opinion then concluded th a t

they do not constitu te o r pu rp o rt to be rules or reg u la

tions or o rders of general application. I t w as then

sta ted th a t since they w ere not a rule, regulation o r

order, they constitu te “ a s ta tem en t of policy” , and

while HEW ‘‘is under no s ta tu to ry com pulsion to issue

such s ta tem en ts” it w as decided th a t it is “ of m an i

fest ad v an tag e” to the general public to know the

basic considerations which the Com m issioner uses

“ in determ ining w hether a school m eets the requ ire

m ents fo r eligibility to receive financial a ss is tan ce .”

Im m edia te ly the opinion recognizes the inherent un

fa irness and vices of such pronouncem ents of adm inis

tra tiv e policy w ithout an ev identiary hearing . “ The

guidelines have the vices of all adm in istra tive policies

established un ila te ra lly w ithout a h earin g .” * Finally ,

the opinion concludes th a t the guidelines a re fully con

stitutional, recognizing as it is bound to do, th a t a fa il

u re to com ply w ith them cuts the purse strings and

closes the tre a su ry to all who fail to com ply:

“The g re a t bulk of the school d is tric ts in this

c ircu it have applied for federa l financial as

sistance and therefore opera te under volun

ta ry desegregation plans. A pproval of these

p lans by the Office of Education qualifies the

schools for federal aid. In th is opinion we

have held tha t the H EW G uidelines now in

ef fect are constitutional and are w ith in the

sta tu tory authority created in the Civil R ights

See opinion page 30.

38 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

A c t of 1964. Schools therefore, in com pliance

w ith the G uidelines can in g enera l be re g a rd

ed a s d ischarg ing constitu tional obligations.”

(E m phasis added) (p. 112)

W hether view ed from a substan tive o r p rocedural

point of view, due process and sound jud ic ia l ad

m in istra tion requ ire , a t the very least, an eviden

tia ry hearing on a m a tte r so v ita l to so m any people.^®

Not only a re num erous people affected , bu t those

m ost affected a re the school children of the nation.

The m ost v ita l segm ent of our dem ocratic society is

our school system . The operation and adm in istra tion

of th e public school system s of th is nation a re essen

tia lly a local business. I t is unthinkable th a t m a tte rs

th a t so v ita lly affect th is phase of the national w elfare

should be decided in such su m m ary fashion. In the

The 1966 Guidelines were promulgated on March 7, 1966, after

these cases were docketed in this Court. The fact that the

appellees had no opportunity to have a hearing and that the

guidelines were unilaterally issued without receipt of evi

dence from the numerous school districts was called to the

attention of this Court by one of the briefs for appellees:

“As pointed out in detail below, the Constitutional and

legi-slative principles applicable to the expenditures of fed

eral funds, the legislative and administrative discretion

placing conditions upon the receipt and use thereof, the lack

of due process in the adoption thereof and the lack

of any opportunity to be heard by those affected thereby

all render such Guidelines inapplicable to the pending

“The 1966 Guidelines (as well as the 1965 Guidelines)

were not approved by the President. They were issued

by the Office of Education unilaterally without an op

portunity for the representatives of the thousands of

school districts affected thereby to be heard. As

unilateral directives they have not been subject to

judicial review.”

See consolidated brief Jefferson County Board of Education,

pp. 76-77.

U. S., e t a l . V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., e t a l . 39

two m o st recen t pronouncem ents by the Suprem e

Court dealing w ith the p roblem of segregation as re

la ted to facu lty and staff, th a t C ourt refused to ac t

w ithout an ev iden tiary hearing . In both decisions the

cases w ere rem anded to the d is tric t court “ fo r eviden

tia ry h earin g s .” B radley v. School Bd. of R ichm ond

(1965) 382 U.S. 103, 15 L.ed.2d 187; R ogers v. Paul

(1965) 382 U.S. 198, 15 L.ed.2d 265. S im ilarly , in Cal

houn V. L a tim er (1964) 377 U.S. 263, 12 L.ed.2d 288, the

Court h ad for consideration a desegregation p lan of

the A tlan ta B oard of Education. D uring the a rgum en t

before the Suprem e C ourt counsel for the B oard of E d

ucation inform ed the Court th a t subsequent to the de

cision of the low er court, the B oard had adopted addi

tional provisions authorizing “ free tra n s fe rs w ith cer

ta in lim ita tions in the city high schools” . The petition

ers contended th a t the changes did not m eet constitu

tional s tan d ard s and a sse rted th a t w ith resp ec t to ele

m en tary students the changed p lan would not achieve

desegregation until som etim e in the 1970’s. The Su

p rem e C ourt did not “ g rasp the n e ttle ” bu t vaca ted

the o rd e r of the lower court and rem anded the case to

“ be ap p ra ised by the d is tric t court in a p roper eviden

tia ry hearing.” (E m phasis added)

III

D ecree

I now com e to a consideration of the decree o rdered

to be en tered and its re la tion to the opinion. I t is im

possible to consider the decree and the opinion sep-

40 U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

ara te ly ; they a re inex tricab ly interw oven. N either

takes into account “ m ultifarious local difficulties” ,

and therefore, any p a rtic u la r or p ecu liar local p rob

lem s a re subm erged and sacrificed to the ap p aren t

determ ination , evident on the face of both the opin

ion and the decree, to achieve percen tage enrollm ents

w hich w ill re flec t the kind of ra c ia l ba lance the

opinion seeks to achieve.

The opinion a sse rts th a t uniform ity m ust be

achieved forthw ith in everyone of the six s ta tes em

braced w ithin the F ifth C ircuit. No consideration is

given to any distinction in any of the num erous school

system s involved. U rban schools, ru ra l ones, sm all

schools, la rg e ones, a reas w here ra c ia l im balance is

la rg e or sm all, the re la tiv e num ber of N egro and w hite

children in any p a rtic u la r a rea , or any of the other

m y riad problem s w hich a re known to every school

ad m in is tra to r, a re taken into account. All th ings m ust

yield to speed, uniform ity , p e rcen tages and propor

tional rep resen ta tion . T here a re no lim itations and

there a re no excuses. This philosophy does not com

p ort w ith the philosophy w hich has guided and been

inheren t in the segregation problem since Brown II.

As the C ourt th e re s ta te d :

“ B ecause these cases arose under d ifferen t

local conditions and th e ir disposition will in

volve a v a rie ty of local problem s, we requ ired

fu rth e r argum ent on the question of re lie f.”

(p. 298) (E m phasis added)

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 41

See also D avis v. Bd. of Com m, of Mobile Co., A la.,

322 F.2d 356 (5 Cir. 1963) -wherein this Court m ade a

distinction in the ru ra l and u rban schools of Mobile

County, A labam a. We held;

“The D istric t C ourt m ay m odify th is o rder

to defer desegregation of ru ra l schools in

M obile County until Septem ber 1964, should

the D istric t C ourt a fte r fu rther hearing con

clude th a t special planning of adm in istra tive

problem s fo r ru ra l schools in the county m ake

it im prac ticab le for such schools to s ta r t de

segregation in Septem ber 1963.”

The effectiveness of the d is tric t courts h a s been

seriously im paired , in a re a l sense, co n tra ry to the

teachings of all the decisions of the Suprem e Court

since Brow n II. U nder the opinion and decree a

U nited S ta tes D istric t Judge serves essen tially as a

referee, m a ste r, or hearing exam iner. Now his only

functions a re to o rder the enforcem ent of the de

tailed, uniform , stereotyped fo rm al decree, to super

vise com pliance w ith its detailed provisions as th e re

in o rdered and directed , and to receive periodic re

ports m uch in the sam e fashion as reports a re re

ceived by an o rd inary clerk in a la rge business es

tablishm ent.

Such a detailed decree on the appellate level not

only v io la tes sound concepts of jud ic ia l ad m in is tra

tion, bu t it v io lates a longstanding philosophy of the

federal jud ic ia l system , and indeed all jud icia l sys

tem s com m on to this country, w hich vest wide dis-

42 17. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

cretion and au thority in tr ia l courts because of their

closeness to and fam ilia rity w ith local problem s. See

the opinions in Brown II, B radley, Rogers, and Cal

houn. F o r exam ple, in Brow n II the Court s ta ted :

“F u ll im plem entation of these constitu tional

p rinc ip les m a y requ ire solution of varied local

school problem s. School au thorities have the

p rim ary responsibility for elucidating, a ssess

ing, and solving these p rob lem s; courts w ill

have to consider w hether the action of school

au thorities constitutes good fa ith im p lem en ta

tion of the governing constitu tional principles.

B ecause of their p roxim ity to local conditions

and th e possible need for fu rth er hearings,

the courts w hich originally heard these cases

can best perform th is judicia l appraisal. Ac

cordingly, we believe it app rop ria te to rem an d

the cases to those courts.

“ In fashioning and effectuating the decrees,

the courts w ill be guided by equitable p rin

ciples. T raditionally , equity h a s been char

acterized hy a practical flex ib ility in shaping

its rem ed ies and by a fac ility for ad justing

and reconciling public and p riv a te needs.

T hese cases call for the exercise of these tra

ditional a ttribu tes of equity power. At stake is

the personal in te rest of the p lain tiffs in adm is

sion to public schools as soon as p rac ticab le

on a nondiscrim inatory basis. To effectuate

th is in te re s t m ay call for elim ination of a va

rie ty of obstacles in m aking the transition to

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 43

school system s opera ted in accordance w ith

the constitu tional principles set fo rth in our

M ay 17, 1954, decision.” (E m phasis added)

The opinion a sse rts th a t “m ost ju d g es” do not

possess the necessa ry com petence to deal w ith the

questions p resen ted , and do not “ know the righ ts

questions, m uch less the rig h t an sw ers .” N otwith

standing the foregoing assertion , the judges of the

m ajo rity , acting on the appellate level, p roceed to

fashion a decree of such m inu te detail and specificity

as to rem ove all d iscretion and au thority from the

d is tric t judges on w hom the Suprem e Court has relied

so heavily . In m y view the d istric t judges a re in m uch

b e tte r position to know the questions and the answ ers

than appellate judges who necessarily function som e

d istance aw ay from an evidentiary hearing and a re

rem oved fro m the “m ultifarious local p rob lem s” and

“ the v a rie ty of obstac les” inheren t in the solution of

the issues p resen ted .

IV

Percentages, Proportions and Freedom of Choice

F reed o m of choice m eans the unrestric ted , unin

hibited, u n restra in ed , unhurried , and u n h arried righ t

to choose w here a studen t will a ttend public school

sub jec t only to adm in istra tive considerations w hich

do not tak e into account or a re not re la ted to con

siderations of race . If there is a free choice, free in

every sense of the word, exercised by students or by

th e ir p a ren ts , or by both, depending on the c ircum

stances, in accordance w ith a p lan fa irly and ju stly

44 U. S., et al. v. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al.

adm in istered fo r the purpose of elim inating segrega

tion, the dual school system as such w ill u ltim ate ly

d isappear. Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683

(1963); B radley v. School Board, 345 F .2d 310,318 (4

Cir. 1965), vaca ted and rem anded on o th er grounds,

382 U.S. 108 (1965 per cu riam ). See also Clark v.

Board of Educ. of L ittle R ock, 369 F .2d 661 (8 Cir.

1966); Deal v. C incinnati Bd. of E duc., 369 F.2d 55,59

(6 C ir. 1966); Lee, et al. v. M acon County Board of

Education, et al. (D.C. M.D. Ala. 1967) C.A. 604-E,

. . . . F . Supp...........If the com pletely fi^ee choice is a f

forded and neither the students nor th e ir p a re n ts de

sire to change the schools the students h ave hereto

fore attended, th is C ourt is w ithout au thority under

the Constitution or any enactm en t of C ongress to com

pel them to m ake a change. Im plic it in freedom of

choice is the rig h t to choose to rem a in in a p a rtic u la r

school, pe rh ap s the school hereto fore attended . T h a t in

itself is the exercise of a free^ choice. The fac t th a t

N egro children m ay not choose to leave th e ir asso

ciates, friends, or m em bers of the ir fam ilies to a ttend

a school w here those associates a re elim inated does

not m e an th a t freedom of choice does not w ork or is

not effectively afforded. The assertion by the m ajo rity

th a t “ the only school desegregation p lan th a t m eets

Constitutional s tan d ard s is one th a t w orks’’ as in te r

p re ted by th a t opinion, sim ply m eans th a t students

and p a ren ts w ill not be given a free choice if the re

sults envisioned by the m a jo rity a re not actually

achieved. T here m u st be a m ixing of the races ac

cording to m a jo rity philosophy even if such m ixing

can only be achieved under the lash of compul-

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 45

sion. If the percen tage of Negro and w hite chil

dren attending a p a rticu la r school does not con-

fornn to the percen tage of N egro and white

school population p reva len t in the com m unity, the

m ajo rity concludes th a t the p lan of desegregation

does not work. A ccordingly, w hile professing to vouch

safe freedom and liberty to Negro children, they have

destroyed the freedom and liberty of a ll students,

Negro and w hite alike. T here m ust be a m ixing of the

races, or in tegra tion a t all costs, or the p lan does not

w ork according to the opinion. Such has not been

and is not now the sp irit or the le tte r of the law.

The a im and a ttitude of the m ajo rity is reflected

by the following s ta te m e n t:

“ In review ing the effectiveness of an ap

proved p lan it seem s reasonable to use som e

so rt of y a rd stick or objective percen tage

guide. The percen tage requ irem en ts in the

G uidelines a re m odest, suggesting only th a t

system s using free choice p lans for a t leas t

two y e a rs should expect 15 to 18 p e r cent of

the pupil population to have selected desegre

gated schools.”

F u rth e r the Court equates the percen tage attendance

test w ith p e rcen tag es in ju ry exclusion^ cases and

One of the leading and most recent cases on jury exclusion

is Swain v. Alabama (1965) 380 U.S. 202, 13 L.ed.2d 759.

With respect to proportional representation on juries the

Court concluded:

“Venires drawn from the jury box made up in this

manner unquestionably contained a smaller proportion

46 U . S., e t a l . V. J e f f . County Bd. o f Educ., e t a l .

voter reg istra tion cases. I t should be pointed out th a t

such cases had no e lem ent of free choice in them ,

and therefore, the com parison is inapposite. In the

in s tan t cases the m a jo rity condem ns a free choice

p lan unless it achieves the percetitage re su lt w hich

suits the m ajo rity . A ccordingly, the opinion con

cludes ;

“ P ercen tages have been used in o ther civil

righ ts cases. A s im ila r inference m ay be

d raw n in school desegregation cases, when

the num ber of N egroes attending school w ith

w hite children is m an ifestly out of line w ith

the ra tio of N egro school children to w hite

school ch ildren in public schools. Common

sense suggests th a t a gross d iscrepancy be

tween the ra tio of N egroes to w hite children

in a school and the HEW p ercen tag e guides

ra ise s an inference th a t the school p lan is not

working as it should in providing a un itary ,

in teg ra ted sy stem .”

T here is no constitu tional requ irem ent of p ropor

tional rep resen ta tion in the schools according to race.

of the Negro community than of the white community.

But a defendant in a criminal case is not constitutionally

entitled to demand a proportionate number of his race

on the jury which tries him nor on the venire or jury

roll from which the petit jurors are drawn.” (p. 208)

Further, the Court; in Stvain quoted with approval the fol

lowing statement from Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282, 286-

287, 94 L.ed. 839, 847:

“Obviously the number of races and nationalities appear

ing in the ancestry of our citizens would make it im

possible to meet a requirement of proportional representa

tion. Similarly, since there can be no exclusion of

Negroes as a race and no discrimination because of color,

proportional limitation is not permissible.”

U. S., et al. V. Jeff. County Bd. of Educ., et al. 47

F u rth erm o re , sihce th e re can be no exclusion based

on race , proportional lim itation is likewise im perm is

sible under the Constitution.

We should be concerned w ith the elim ination of