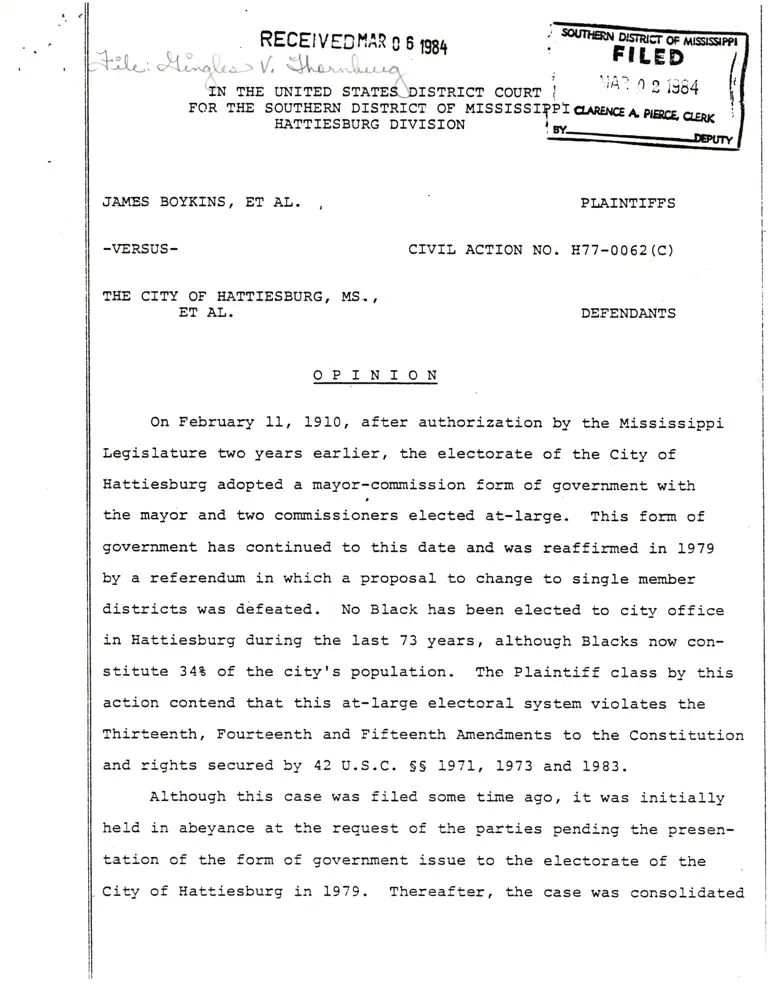

Boykins v. City of Hattiesburg Opinion

Public Court Documents

February 29, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Schnapper. Boykins v. City of Hattiesburg Opinion, 1984. 1755a8b8-e292-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8b4ac583-86cf-4739-8d8c-e01b0d305f88/boykins-v-city-of-hattiesburg-opinion. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

RECEIvEBtlAR o 6 pgrrtiL, "!{J"..,.,-,.

'. v', $L0.,,', ..,,.i

.IN TtsE I'NITED STNTE(JDISTRTCT COURT i

FOR THE SOUTIIERN DTSTRICT OF MISSTSSI}I

HATTIESBURG DIVISION

JAMES BOYKINS, ET At.

-VERSUS-

THE CITY OF HATTIESBURG, MS.,

ET A],.

CIVIL ACTION NO.

PI,AINTIPTS

fi,77-0052 (C)

DEFENDAI{TS

OPINION

On February 11, 1910, after authorization by the Mississippi

Legislature two years earlier, the electorate of the City of

Hattiesburg adopted a mayor-commission form of government with

the maydr and, two comrnissiorr"r" elected, at-large. This form of

governmeat has continued to this d,ate and was reaffirmed in L979

by a referendum in which a proposal to change to single member

districts was difeated. No Black has been elected to city office

in Hattiesburg during the last 73 years, al.though Blacks now con-

stitute 34t of the city's popuJ-ation. The Plaintiff class by this

action contend that this at-Iarge electoral system violates the

Thirteenth, E'ourteenth and E'ifteenth AmenCments to the Constitution

and rights secured by 42 U.S.C. SS 1971, L973 and 1983.

Although this case was filed some time dgo, it was initially

held in abeyance at the request of the parties penCing the presen-

tation of the form of government issue to the electorate of the

City of Hattiesburg in L979. Thereafter, the case tras consolid,ated

with a new case filed by the United, States also challenging the

form of eity government and discovery in the consolid,ated cases

proceeded in an orderJ-y fashion.

In 1980 the United States Supreme Court decided the case of

City of llobile v. Bolden, 445 U.S. 55, 64 L.Ed.2d 47 (1980), estab-

lishing the purposeful discrimination standard in challenges to

eLectoral systems. The United States then dismissed its challenge

to the form of government and the earlier filed case proceeded to

trial in late 1980.

This Court has deliberately proceeded slowIy in this case in

order to prevent the turmoil and, unnecessary taxpayer costs inher-

ent in any possible change in the form of governnent, including

the great expense of repetitive appeals tc the Circuit Court. In

early 1981, the Fifth Circuj.t Court of Appeals began consid,eration

of a factual-1y si:uilar situation regarding the City of Jackson,

wherein a class action chal.lenged the at-large mayor-comrnissioner

system adopted in L9L2 and, reaffirmed by referend,um in L977 .

Kirksetz v. City of Jackson, Mississippi, 663 F.2d 559 (5th Cir,

1981). This case had been remanded to the district court in 1980

for reconsideration in light of the Supreme Courtrs decision in

Bol-den. Ir. December of 198L the Circuit Court affirmed the

District Courtrs determination that the record did not d,emonstrate

a ra.cially discriminatory purpose in the establishment or mainten-

ance of the Jackson at-1arge mayor-commj-ssioner forrn of government.

Significantly, the Fif*l Cj.rcuit Court of Appeals noted in that

d.ecision that "[O]ur path has been blazedi ]/e do not write on a

'1

clean sIate". Kirksey, supra at 553.

Shortly thereafter, Congress blazed a new path by the enacErcrrE

of a new S 2 in the extension of the VotS.ng Rights Act in 1982.

This amendment wilL be discussed, in detail hereinafter. Neverthe-'

less, in earLy 1983 the Plaintiffs in this action sought and. were

granted permission to amend their complaint to allege violations

of nev, S 2 of the Voting Rights Act and, both sides were given the

full oPPortunity to supplement the record. in any manner desired.

Thereafter, ad,d,itional evidence bras filed with the Court directed

toward the S 2 issue. This Court has now examined this matter

pursuant to new S 2 of the Voting Rights Act and finds that the

"results" alternative of ghat Act necessitates a different

result from the determinati-on to date in Kj.rksey, =onr".I' This

finding by the Court obviates the necessity of the dj-fficult d,eter-

mination regarding purposeful discrimination in the enactment or

maintenance of an at-large mayor-commissioner system of government

for the City of Hattiesburg. In the Courtrs opinion, the status

of the law is nov, sufficiently stable to enable the Court to make

the following determinatj-on in this matter.

Prior to June 29, 1982 amen&tents to S 2 of the Voting Rights

L/

The Court would note that there have been three separate

Iower court opinions and appeals to the Fifth Circuit in

Kirksey, supra, since that suit was instituted, in L977,

and the matter remains in almost the identj-cal posture

as the case at bar, with a pending challenge now pursuant

to new S 2 of the Voting Rights Act in a separate casd.

-3-

2/

Actl Plaintiffs who sought to establish that an at-large votj.ng

scheme (such as the one challenged in the instant case) unlawfully.

d,iluted minority voting strengtt in violation of the Voting Rights

Act, had to prove purposeful d,iscrinj.nation in either the enactment

or maintenance of the challenged electoral system, CiBr of ttobiJ.e v.

Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 64 L.Ed.2d 47 (1980).

However, when Congress enacted the new S 2 as part of its 1982

extension of the Voting Rights Act it specifically rejected the

Bolden intent standard. and eLiminated the requirement that S 2 plain-

tiffs demonstrate purposeful d.iscri,rnination, see S. Rep. No. 97-147,

97 Con., 2 Sess., 15 & 27-30, !4cMj-LIan v. Escanbia Co:nty, Flonida, 688

r.2d 960, 961 n. 2 (5th Cir. 1982) [hereinafter ]1c!4i11an III . Under

amend,ed, S 2, while a court in vote dilution cases may continue to

consider purposeful discriminatj-on, it must also consider, if aLlegred,

The amendment read.s as follows: Sec. 2(a). No voting qualifica-

t,ion or prerequisite to voting or standard., practice, or procedure

shall be imposed applied by any State or political subdivision in a

manner which results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any

citizen of the United States to vot-e on account of race or coIor,

or in contraventj-on of the guarantees set forth in Section 4(f) (2) ,

as provided in subsecti-on (b) .

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is established j.f, based on

the totality of circumstances, it is shown that the political

processes leading to nomination or election in the State or polit-

ical subdivisions are not equal-Iy open to participation by mernbers

of a class of citizens protected by subsection (a) in that its

members have less opportunity than other mernbers of the electorate

to participate in the political process and to elect representatives

of their choice. The extent to which members of a protected class

have been elec',-ed to office in the State or political subdivision

is one circumstance which may be considered: Provided, that nothing

in this section establishes a right to have members of a protected

class elected in numbers equal to their proportion in the population

Pub L. No. 97-205, S 3, 96 Stat. 131, 134 [to be cod,ified at 42

U.S.c. S 1973) reprinted, in 51 U.S.c.w. 2 1l-982) tr. s. code Cong.

& Admin. News No. 5 (Ju1y, 1982) .

2/

-4-

the discriminatory results of the challenged practice, procedure or

rule.

Plaintiffs must either provide such

intentr oE alternatively, must shorrr

that the challenged system or practice,

in the context of all the circumstances

in the jurisdiction in questionr l€srlts

in minorities being denied equal access

to the political process.

S. Rep. No. 97-4L7 | 97th. Ccng. 2d, Sess. 27 (1982) (footnote omitted),

reprinted in [1982] U. S. Code Cong. & Adrnin. News 2AS (Ju1y 1982)

lhereinafter Senate Report] .

The legislative history makes .it clear that S 2 amendment was

explicitly written to overruLe Bo1d,enrs holding that proof of a

d,iscrj:ninatory intent was the sole means of establishing a vote

dilution case (S. Rep. 36). Indeed, Congress concluded that Bolden

had represented a d.eparture from the origi-naI 1955 statutory standard

and that the L982 amendment was simply to re-estahlish that a "results

standard is the appropriate standard, under which S 2 vote dilution

cases should be considered (Senate Report 17-27).

Congress noted that the "results" standard is particularly

well suited for evaluation of challenges to at,-large voting schemes.

The House of Representatives Judiciary Conunittee, assigned to j-nves-

tigate and report to the full house on the Votj.ng Rights Extension,

noted that at-large electoral systems tended to d,ilute minority

voting strength:

The comrnittee heard numerous reports

of how at-large elections are one of

the most effective methods of diluting

minority strength in the covered juris-

d,ictions ' (H Rep. 97-227 , 98 Cong. lst

Sess. 18 ( t19811 [hereinafter llouse

Reportl ) ;

and

to

of

but

of

to

for

Numerous empirical studies based on

d,ata collected from many communities

have found a strong link betrveen at-

large elections and Lac!: of minority

representation" (Id. at 30) (footnote

omjtted).

The Senate Jud,iciary Committee reported several challenges

at-1arge voting schemes where there has been strong evidence

present day discriminatory effects resulting from the system,

where proof of motivation i.n the enactment or maintenance

the system has for various reasons been difficult or i-rnpossible

obtain (Senate Report 36-39). Congress noted several reasons

these proof difficultj-es.

First, where the system was established a number of years d9o,

the challenged, scheme "cannot be

i

testimony about the motives behind

i

Proof of motivations therefore

I

j

and expensive historical investi-

available at all (Senate Report

the pubi-ic officials who enacted,

subpoenaed from their graves for

their actions" (Senate Report).

invol.ves arduous, tirne consr:ming

gation, even if evidence is sti1l

35) .

second,ly, current public officiars, although subject to

subpoena and, examination regarding their individual motivations,

have a strong personal interest in maintaining the status guo,

and are easily able to develop non-racial rationalizations to

defeat challenges to racially d,iscri:ninatory electoral systems

(Senate Report 37).

Finally, congress acknowled.ged that requiring inquiry into

officialsrmotivations can have an ad.verse social cost: it can be

-5-

"unncesssarily divisive" and even destructive of any existing

attempt,s at racial progress in a community (Senate Report 36).

In order to avoid these and other difficulties created by

the "intent" standard of Bolden, Congress a^mended S 2 of the Voting

Rights Act to protect the right of minority voters to be free from

gg1 election policy which denies them equal access to the political

process. The focus is on the results of the election policy, not

on the hearts and minds of governmental policymakers. Thus, if an

at-large election scheme results in a denial of the opportunity for

egual access, it is prohibited by S 2 regard,less of whether the

prohibited result can be shown to be the result of subjective

intent.

This finaing Uy the Court is supported by the recent d,ecision

in Jordan v. City of Greenwood, l,lississippi, 7LL F.2d 567 (5th Cir.

1983) in which the Circuit Court noted,:

New S 2 [ot the Voting Rights Act] r orr the

other hand, outlaws any voting practice

that results in a denj.al or abri.dgement

of the right to vote on account of race

or color. This change from purpose to

effect represents a significant legisla-

tive departure from theory on which lCitv

of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 198OT-

The legislative corunittees reporti.ng to Congress on the pro-

posed amend,ment S 2 also offered guidance as to the proof which may

be consid,ered in determining whether or not the "totality of the

circumstances" test set forth in the statu.te has been rnet. The

tlpical factors to be considered by the court include:

1. The extent of any history of official discrimina-

tion in the state or political subdivision

that touched the right of the members of the

-7-

rtinority group to register, to voter oE

otherwise to participate in the democratic

Process;

The extent to which voting in the elections

of the state or political subdivision is

racially polarized;

The extent to which the state or political

subdivision haq unusually large electj.on

districts, majority vote requirements,

antj.-single shot provisions, or other

votj-ng practices or proeedures that may

enhance the opportunity for d.iscrimination

against the minority group;

If there is a candidate slating process,

whether the members of the minority group

have been denied, access to that process;

5. The extent to which members of the minority

group in the state or political subdivision

bear the effects of d,iscrimination in such

areas as education, employment and health,

which hinder their abilj-ty to participate

i effectively in the political process;

S.,Whether political campaigns have been

, characterized by overt or subtle racial appeals;

7. 'The extent to which members of the minority

igloup hqvq.been elected, to public office iir

, the jurisdiction.

206-07 (footnotes omitted) .

Violations of the statutory standard, estabLished by S 2 are

proved by showing the existence of an aggregate of these factors.

Both reports note.that not all need, to be shown in order to prove

a S 2 violation (House Report at 30, Senate Report at 28-29). Which

factors are relevant and how many need. to be shown depends on the

circumstances of the particular case and their effect on whether

minority voters have equal opportunity to elect represenlatives of

their choice.

[T] he factors were considered as part

of the total circumstances and in light

of the ultirnate issues to be decided, i.e.,

whether the political processes were equally

open. (Senate Report at 34-35).

)

3.

4.

[\po clistrict courts in the Fifth Circuit have, with explicit

reference to the Senate Report, adopted the factors and anai.ytical

approach suggested by Congress, Jones v. City of Lubbockr Ctv1l

Actloa No. Ca-5-76-?4 (N.D.Tex. Jan 30,11t83); Alonzo v- JonPs,

-

F.Supp (s.D.Tx. 'Feb. 3, 1983) . In both these cases, despi

the fact that not all listed, factors $rere present, the Court con-

cluded that the requisite "totality of circumstances" proof had be

presented and a violation of S 2 had been established in the main-

tenance of at-large voting schemes. The Fifth Cireuit has also

cited with approval and relied on the Senate Report as the basis

for its conclusion that amended S 2 eliminated the Bolden intent

requirement, McMillan If , 588 F.2d at 96L, n.2.

This Court is of the opinion that the evidence in this case

establishes that the mayor-commission at-large voting election

scheme used.'in Battiesburg, Mississippi results in a denial to

Black Eattiesburg voters of an equal opportunity with Whites 'to

parti.cipate in the political process and, to elect representatives

of their choice" (95 Stat. at L34), and therefore violates

Plaintiffs' rights as secured by S 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as

amended.

Evidence

or political

to register,

makes a strong

tioned first

at 28i House

of a history of official discrimination in the state

subdivision affecting the right of minority citizens

to vote, oE to particiPate in the electoral process

case of a Section 2 violation. This factor is men-

in both the Senate and llouse reports (Senate Report

Report at 30). In White v. Regester, 4)-2 U- S. 755,

93 S.Ct. 2332, 37 L.Ed. 2d 314 (1973),the Supreme Court re1led

heavily on Ehe factor of whether there lraa a hlstory of officlal dlscrlmioatioa

ro Ehow that at-large legislative elections denied black voter

an equal opportunity to participate in the political processes:

with d,ue regard f or these standards, the

District iourt first referred to the history

of of f j-ciaL racial discrimination in Texas,

which at times touched' the right of Negroes

to register and vote and to participate in the

democratic Processes.

4L2 U.S. at 765. This factor was considered important in a recent

District Court decision appJ-ying thg new Section 5 standard to

hold at-large city counsel elections in Lubbock, Texas, unlawfuL:

In view of the Courtrs finding in its original

opinion that there was a history of official

discri:nination in the State of Texas and that

tir€s€ discriminatory practices and procedures

were in existence in the City of Lubbock in

the earlier years in the century, such factor

(the extent of the history of official discrim-

ination) points to the conclusion that the

present election Proced'ures in Lubbock result

from past d,iscriraination.

Jonesv.cr@,Civi1ActionNo.Ca-5-76-34(N.D.Tex.*

January 30, 1983) (sliP oP- at 5).

The Mississippi Constitution of 1890 d,isfranchised the Black

citizens of tlississippi through a variety of technigues, including

the poll tax, literacy clause, and understanding clause (R 219) -

In 1910, in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, only seven Black voters

remained on the registration list out of over 700 voters (R221).

By L9L2, the City included seven B1ack registered voters out of

almost I,4OO voters (n 221-222). Mr. Boykins testifj.ed that by

1951 he was the second Black person on the voter registration li-st

of Forrest County, Mississippi (n 361). The United States Justice

Department engaged in extensive litigation includigg contempt

- 10-

citations from 1961 through 1965 in order to reguire Theron Lynd,,

then Circuit Clerk and Registrar of Forrest County, tlississippi,

to register Blacks to vote (See P 70). The Fifth Circuit Court of

Appeals noted in L955:

Obviously thg deni-al of these rights--at one' and the same time in violation of the Constitu-

tion and the ord,ers of this Court--demands

correction. At the snaj.l's pace to date, it

will take decades to eradicate the evil lrEusal

unty,

Mississippil.

Exhibit P 70 at 793) (ernphasis added)

The evidence also reveals that pursuant to the Voti.ng Rights

Act, federal registrars were sent to Eattiesburg, Forrest County,

Mississippi, to register Blacks to vote in 1967 and 1968 (p 82 at

8-10) and federal observers were sent to observe an election in

L967 (P 87, 88, Admission 24).

Theron Lynd remained Circuit Clerk until his death in 1978.

At that time Marian Brown, who had worked as a Deputy Clerk for

Theron Lynd for sixteen years, vron election as Circuit Clerk and

Registrar of Forrest County, !4ississippi (n 818-819). The Circuit

Clerkrs office remained staffed by all White persons as late as

1978 (p 87-88), Admission 26) . Furthermore, as late as 1980 the

Circuit Clerkrs office, which issues marriage licenses and, keeps

the marriage records for the County, kept the marriage records

segregated by race, one in a book marked, "colored" and one marked

"white" (n 828), and refused to issue marriage licenses to inter-

racj.al couples (at least until April of 1978) (n 829-830) .

In regard.s to present registration of voters in Forrest County

it is still the practice to keep registratj.on lists which identify

'voters by their race (n 828). Furthermore, it is the practice to

refuse to register any student who Lives on the cElmpus of the

Unj.versity of Southern l{ississippi, in Eattiesburg, Forrest County

Mississippi., and therefore to refuse to register Black Persons

residing in llattiesburg , Lf they give a residence add.ress on the

caupus_ of the Universlty of Southern l,lississippi (n 832-833) . Fina1.L'

it is the local practice to refuse to register any Person includ

Black persons within thirty days of any electj-on.

This evidence clearJ-y shows that there remains today the

lingering effect of past discrimination in the operation of the

office of the Circuit Cl-erk of Forrest County, which directly

affects the right of Black persons residing in Eattiesburg to

to register to vote.

Not only were Blacks in Hattiesburg previously not allowed

to vote, they were not allowed to participate in the Democratic

Party and enter Democratic primary elections. In L976, following

extensive f-itigation within the national Democratic ,Party as well

as federal court suits, the Democratic Party of Mississippi was

integrated. In L976, for the first ti:ne, Blacks were allowed on

the Forrest County Democratic Party Executi-ve Committee (n 267) .

However, a't the time of the trial in 1980, Do B1ack had ever been

nominated in a party primary to run for City goverrurent (StiPula-

tion 6). Furthermore, the Democratic Party of Forrest County,

tlississippi, which includes Hattiesburg, Mississippi, had, not soug

out a Black candidate. Whereas Blacks were first admitted into

the Democratic Party of Porrest County in L976, Blacks did not

sit on the Executive Committee of the Republican Party of Forrest

County, Mississ.ippi until 1980 (n 732). Further, it was not until

1980 that the first Black person ever qualified to run for office

on a Republican ticket in Forrest County, Mississippi (R 732).

-L2-

In addition to the present effects of Past discrirnination in

the Circuit Clerkrs offj.ce, the Democratic Party, and the Republ:lcart

party, Blacks face additional obstacl-es to equal participation in

the politicaL process. The prejudices of the l{hite community, and

f ear of Black participa.tion in the political process, has not sirp

d.isappeared. Both Deborah Garnbrell and Percy Watson, in L979, the

first two B1ack persons ever elected to office from Forrest.County,

testified concerning racial bigotry that they confronted (n 325-326,

274, 277-278). Judge GambreLl testified, in part:

I recall sending out literature lin L97 ? ] after

I becane a Democratic Party nominee. . . thanking

everybody f or supporting me, and I ' d get letters

back that said, t r lor things like th@e most dramatic

was on election day. . . in

front of my ca.rtpaign workers I got some brochures

back that I had mailed. I had a Person in

my court last Thursday that said 'I'm just fed

niggersr' . . . (F.277-278)with aL1 vou nissers,' . . . (F.277-278) .

The testimony from the Black community was unanimous to the

effect that it remained. impossible in 1980 to obtain any substan-

tial support from the White community in terms of money or votes

(n 272, 303-304, 355, 400), and, that the White community still

feared and opposed the participation of Blacks in the poJ-itical

process (R 279-81, 393, 354, 405, 407). Judge Deborah Gambrell

testified in this regard as folLows:

Q: Nor,r, what about getting Blacks eLected

into the City Commission?

A: I think it is utterlY i:nPossible

itts a futile effort; . . .there is no

way a Black can win in an at-large election

in the City of llattiesburg. . .because the

Whites tend to bloc vote for the White

candid,ates, and Whites are the majority-

Q: And in your estimation why do Whites

vote for White candidates?

A: Because they fear blacks in political

povrer.

Representative PercY

(n 275-2761.

Watson testified in this regard, in part:

...From your experience in these political

campaigns . . . do you have an opinion as to

whether or not a Black candidate can get

any substantial support in terms of money

or votes .from the white voters of this

district?

My opinion is that you cannot get substan-

tial-support, votesr ot monetary co!tribu-

tions flem the White conuounity (at 303) '

Q: Why were you able to win that election

lfor State Representative in 19791 ?

A: ...The [reapportj-onment] lawsuit gave

District 104 the majority Black d'istrict

y€s r tthatl was the primary factor; - . -

Q: And in your opinion can a qualified Black

candidate. . .get elected as a CitY

Commissioner in the City of Eattiesburg

in an at-large election?

A. !'ty opinion is that a qualified Black

candiaate .could not. . . lbecause] Whites

generally wiJ-I not vote for or support

i gtack Landidate. . . [because] it's that

they [WhitesJ desire to keep Blacks out

of office (n 340-342).

The testimony from the Black corununity of Hattiesburg was

confirmed, and corroborated by expert testirnony at trial. Dr'

James Loewen, a sociologist, testified that because of racial bloc

voting, it was impossib3-e for a Bl-ack candidate to win office in

the City of ttattiesburg (85, 144). Dr. Loewen further testified

based upon voting patterns as well as his study of l"lississippi

history, race relations and polj-ticaI sociology, that many White

voters in gattiesburg remained d.etermined. to deny Blacks participa

tion in the political system because of the history of racial

prejud,ice dating back through segregation and slavery (A 51-53, 67

Q:

A.

Dr. Gordon Henderson, a political scientist, testj.fied that it was

impossible for B1acks to hoi,d elective office under the at-large

system of elections in Hattiesburg because the White conununity

opposed the election of Blacks (n I85, 2L2).

Not only did the experts at trial corroborate the experience

and 1ay opinions of the Black community, but also lay witnesses

from the White corununity, including ex-Mayor Gerrard (p 76 at 9-10

confirmed that members of the White community continue to opPose

and fear the election of B1acks to office (e.9- n 485-485). Karen

Fawcett testified in regards to her'discussions with members of

the White courmunity concerning a change in the form of government

to mayor-council with wards:

Even though these people lwhite residents of

Hat,tiesburgl would have dissatisfactions with

this form of goverrurent [commission form with

at-large electionsl, they seem to feel that

. . .there was a very true possibility that we

would have a Black rePresentative, and thj-s

seemed to be a very overriding fear in the

change of government. . .they would say that

[the election of Black rePresentatives] would

be worse than what we have (n 485-585).

In add.ition to the attitude of the White corununity presently

hindering Black participation in the political Process, the Black

conununity remains discouraged from even mounting additional effo

to win elective office in Hattiesburg, !'lississippi. The Black

candidates and people of political experience all believe that it

is "futile" and "utterly impossible" for a Black Person to win

eLective office in at-Iarge elections (n 275, 345) . Representativ

Percy Wat,son testified':

The Blacks are realIy deterred, from running

for City Commission positions; it's futile

. . .you know, in all honesty, there's just

no chance (n 345) .

Representative !{atson further testified that in his campaign in

L975 he actively sought White support and, campaigned in the White

conmunity. Based upon his experience, he determined that he had

actually canpaigned for his White opponents because he brought out

a very large, adverse White vote (309, 339). Representative Watsqr,

in Lg7g, determined that he should. not campaign actively in the

White community because the effect of such a strategy would, be to

bring out votes for his Whj.te opponent (n 338). Sirnilarly, Judge

Garnbrell determined that she could not carrpaign face to face and

docr to door in the White comnunity without fear of white backlash

(n 27 4) . Judge Gambrell opted to campaign in the White community

through mailings (n 274). Because of the large amount of ma5.Iing

necessitated by this type of campaign, the cost of her campaign to

win office was over I00 times as expensive as a normal Justice of

the Peace campaign (n 29l.),

The foregoing evidence makes it abundantly clear that the

massj.ve, historical, official d,iscrimination against B1acks in

Hattiesburg affecting the right to vote continues to restrict the

present access of Blacks to the political process. The challenged,

at-large election system is part and parcel of both the historical

official discrirnination and its present d,iscriminatory results and,r

is therefore maintained in vioLation of the Voting Rights Act, as

amended.

Pursuant to the Sectj-on 2 standard, the existence of a high de-

gree of polarized voting is a factor indj-cating ihat the rights of

minorities have been abridged or diluted because of their race or

color. rn enacting the section 2 "results' test, congress made

- 16-

clear its intention that under the new stand.ard,

til t would be illegal for an at-large election

scheme for a particular state or local body to

permit a bloc voting majority over a substantial

period of time consistently to d,efeat minority

candidates or candidates identified with the

interests of a racial or language minority.

House Report at 30. :l

In Eattiesburg, the evidence shows that thj.s is exactly what

has happened. Not only do we have the sworn testi:nony of Black

candidates and. voters regard,ing this (see pp. l2-L4 supra), there

exists statistical proof of massive long-term raci-al polarj-zation

in Hattiesburg voting. Dr. Loewen conducted, an extensive statis-

tical anal.ysis of the election in which Quincy Dent was the Black

candidate running against White cand,idates for the itattiesburg

City Corumission. Dr. Loewen aLso analyzed, all other known elec-

tions in Forrest County, Mississippi, in which B1ack candid,ates

ran for office against White candj.dates and, voters in the City of

Eattiesburg qrere involved,. Finally, DE. loewen analyzed the voting

patterns in a referendrur held, on August 7, L979, in llattiesburgr.

Mississippi on whether or not to change the form of government to

a mayor-council which would, end at-large elections for the city

council and replace them with nine d,istricts or wards. (fx. P 105).

Dr. Loewen found that there was racial bloc voting in every

election analyzed. In the two exclusively municipal elections, the

Quincy Dent and Form of Government contests, Dr. Loewen noted that

the evidence of racial bloc voting in the White community was "over

whelming" and "extremely high" under three different forms of

statistical voting analysis (n 55). Dr. Loewen concluded from his

analysis of voting patters in Hattiesburg, Mississippi,

That race is the be-all and end-all of

Hattiesburg city politics at this point.

(n 1s1) .

The test5:nony of Dr. Loewen concerning racial bloc voting was

corroborated by the testimony of Flaintiffs' political science

expert, Dt. Henderson, and also by Defendantst experts (n 879 ' R

and by Defendant, Mayor A. L. Gerrard (p ll1, D 2L at 27-281 ' as

well. only Dr. LOewen performed a statistical analysis of the vot-

ing patterns in Eattiesburg, Mississippi, and his analysis and

conclusions stand as unrebutted in the record' Plaintiffs have

clearly established this factor of proof of a section 2 violation'

The City of Hattiesburg uses the largest possible voting

d,istrict in terms of both geographic size and popuLation' The

lggo census refiects a population of 40,829, of which whj-tes make

up a political majority (1980 Census, General Pupulation character

istics, Part 26, Table 32) . As a result of racial pol-arization in

voting, tlre at-large elections permit the white majority to elect

all representatives in this large poJ-itical subdivision' Moreovet'

the large sLze of the district further enhances the lack of access

by Blacks to the political Process by requiring more expensive

campaigns tc win office. In Lg77, it cost l{ayor Gerrard approxi-

mately $8,000.00 to win office (O 2L, at 13)' The record is unre-

butted to the effect that the income of Blacks in Eattiesburg is

approximately one-half the income of whites; the mean income for

White farailies in 1980 \ras $22,300 and for Blacks' $11'8?0 (1980

census of populati , Tape Files 3A, Table 51) ' (n 761

Thus, it is significantly more difficult'for a Black Person to

compete for office in a larger dj.strict which requires more cam-

paign contributions (n 82)'

state Iaw controlling Eattiesburg municipal elections, Miss'

CodeAnn.ss23-3-7land7g(L972),requiresamajorityvotefor

- 18-

party nomination for any nunicipal elective office and in any

special election to f ill a vacancy for ru:nici.pal office (P 87-88) .

As a result, a Black candidate will always face in the primary

a White candidate in a one-on-one contest and if the vote is pola

ized, the Black will lose, a fact also noted by the U.S. Supreme

Court in Rogers v. Lodge t ].O2 U.S. 3272t 73 L.Ed.2d at L024. (1982)

The State of 'llississippi specifically prohibits single shot

voting in municipal elections, Miss. Code Ann. SS 21-11-5; 21-11-I

(L972) (p 87-88; Admission 9). Minority voters are therefore un-

able to concentrate their vote on a single candid.ate in a multi-

candidate fieLd and are, in effect, required to cast votes for

their candidaters opponents if they wish to vote Eor the cand.idate

they prefer. This electoral mechanism was specifically found to

enhance a racially d.iscriminatory election scheme proposed, in the

Ivery county where Eattiesburg is located,. U.S. v. Board of

Supervisors of Forrest Countv | 371 F.2d 951 (5th Cir. f97B).

Miss. Code Ann. SS 21-5-5 and 21-5-11 (].972) authorize munici

palities operating under a commission form of government to desig-

nate specific posts for each conuuissioner. Ilattiesburg requires

candidates to run for one of three designated City Commission

seats (O 2l at 19-20); electors must vote on each seat separately.

This reguirement minj:nizes the voting strength of the Black conmun-

ity because, like the anti-singJ-e shot rule, it prevents a cohesive

political group from concentratj-ng on a single candidate. That

such a requirement results in discrimination was recently affirmed

by the Supreme Court: A numbered post reguirement "enhances [the

t

minority'sl lack of access because it prevents a cohesive politi-

cal group from concentrating on a single candid,ate", Rogers v.

Lodge, supra, 73 L.Ed.2d at L024.

Finally, in tsattiesburg there is no election district residenqr

requirement, except to live within the City of llattiesburg (Stipu-

lation 11). Thus, the lack of residency reguirement combined with

segregated housing patterns (n 84-85) results in ttre possibiJ-ity

that all cand,idates and,,/or officials reside in predominantly white

neighborhoods. This same practice was considered recently in

Rogers v. Lodge, supra. The Court noted that in the absence of a

district residency reguirement " I Ia] 11 candidates could reside

. in "1iJ-1y-white" [sic] neighborhoods. To that extent, the

denj-a1 of access becomes enhancedr" (73 L.Ed.2d at 1024) .

All of these d.iscrj:nination-enhancing features were consider

by the Hcuse Committee on the Judiciary which noted that "indivi-

dually or in combination lthey] result in inhibiting or diluting

minority voting strength," (House Report at 18) and accomplish

this more frequently "in covered jurisdictions where there is

severe racially polarized voting" (!!) .

Al1 of these enhancing features exist in Eattiesburg and have

resulted in further impairing Black access to llattiesburg's

political process.

The evidence does not show that "slating" has played any role

in Eattiesburg municipal politics, although a Ilemocratic ?arty

primary nomination has often in the past been tantamount to vi

in tlississippi politics. The Eouse Report suggests, however,

that the failure of minority condidates to win primary nomination

may be ttre equivalent of racial discrimination in slating: "An

aggregate of objective factors should be consid.ered, such as.

discriminatorys1atingorthefai1uqeofminoritie@

nomination" (ilouse Report at 30 (footnote omj.tted) (emphasis

added). No Black from Hattiesburg or Forrest.county has ever won

a democratic party primary nomination'.until after redistricting

had eliminated racial gerrlzmandering '

Ilowever, the absence of proof of slating, o! racial discrim-

ination in slating per se, does not preclude findS.ng a Section 2

violation or count against Plaintiffs in weighing whether an at-

large system denies minority voters egual access to the political

process. Both the Senate and House Reports emphasize that "there

is no requirement that any particular nr:mber of factors be proved,

or that a majority of thern point one way or the other" (Senate

Report at 29i also House Report at 30). The evidentiary factors

listed in the Committee Reports are not. intended to be used

as a mechanical "point counting" device-

The failure of Plaintiff to establish

any particular factor, is not rebuttal

il:*i:i3""t,Xl[:i';i'iL,i,.]3!"iil: !3i'.' "overalL jud,grment, based on the totality of

the circumstances and guided by those

relevant factors in the particular case,

of whether the voting strength of

minority voters is, in the language

of Fortson and Burns, "mini:nized or

canffie out"

Senate Report at 29 n. 118 [1982) U.S. Cod,e Cong. & Admin. News

207. In Jones v. City of Lubbock, 93p3., the District Court in

applying the new Section 2 standard held that the absence of

evidence of d,iscriarinatory slating Cid not mitigate agaS.nst find-

ing that at-large elections violated Section 2-

There is ample evidence in Hattiesburg that even without

slating, the challengeC at-large election scheme is invalid under

the totality of the circumstances test prescribed by Section 2.

' In enacti-ng the new S 2 amendment, Congrress indicated that

d,emographic data reflectj.ng a disparately low socio-economic statu

of a minority group arising from past d,iscrimination are sufficien

to demonstrate a lack of equal access to the political process.

The courts have recognized. that

d,isproportionate educationaL [,J

employm€4t, income level and J.iving

cond,itions arising from past d,iscrim-

ination tend to d,epress minority

political. participation, e.9., White,

4L2 U.S. at 758i Kirksey v. Board-of

supervisors, 554 tr:m 1a-5:_-

Where these cond,j.tions are shovrn, and,

where the level of Black participation

in politics is depressed, plaintiffs

need not prove any further causal

nexus between their disparate socio-

economic status and the depressed

leve1 of political participation.

Senate Report at 29 n. 1L4 [1982] U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News

207, The Fifth circuit court of Appeals, in a decision which

Congress endorsed in enacting the new statute, held,:

The Supreme Court and this Court

have recognS.zed that d,j.sproportionate

education, employment, income level

and living conditions tend to operate

to deny access to political Life . .

It is not necessary in any case that

a minority prove such a causal link.

Inequality of access is an inference

which fLows from the existence of

economic and educational inegualities.

Kirksev v. Board of Suoervisors of Hinds Countv, !,lississippi, 554

E'.2d 139, 145 (sth cir. 1977 ) (en banc) , cert. denied, 434 u.s.

958 (L977 ) (cited with approval in Senate Report).

DemograPhic data for Eattiesburg reveal that Blacks suffer '1

from a disproportj-onately low socio-economic status in Hattiesburg

which results in i:npaired access to the political process. At

trial, Dr. James Loewen testified to the substantial socio-ecurcrnic

'disparities revealed by the 1970 Census in income (n 76), education

-22-

and f-iteracy (_R 77-78) i kind of enplolzuent Cn 77) i housing gualit

(n 77-7U and access to transportation (n 791 between Blacks and

Whites in Ilattiesburg (see also Post Hearing Trial Brief for P1ain

tiffs, pp. 13-15). L98O Census figures, not available until after

the trial reveal that these disparities persist. Mean Black fanil-

income is only half that of whites, (1980) Census of Population

and llousing, summary Tape File 3a, Item 53). Forty percent of

Black and, only 15t of White families are below the poverty level

(Id., Item 53) .

Massive disparity of educational levels in adults persists as

weII. Blacks constitute 30 percent of the population of Eattieslurg

25 and over. Eowever, they make up 58 percent of those who have

only an elementary school or less education and only 12 percent of

those with four or more years of college (Id., Item 50) - Thirty-

three percent of the total BLack (25 and over) population have

only eLement,ary or lower educations but onLy nine percent have

four-year colJ-ege educations. For Whj-tes the proportions are

reversed: 30 percent of all 25 and over Whites have four years or

more of college; only 10 percent have elementary or lower educa-

tions (Id., Item 50; and l-980 census of Population, General

Population Characteristics, Part 26, Table 32\ '

Blacks in llattiesburg aLso continue to suffer from inferior

living-housing conditions. The med,ian value of Black-owned homes

in Eattiesburg j-s less than half that of White-owned hcnes ($19,400

for Blacks; $41,000 for whites). In 1980, di.sproportionately

more Blacks lived in substand,ard, housi.g; ten percent of all Black

houses lack complete plumbing for exclusive use as compared to only

one percent of aL1 White households (Table 32, General Housing

Characteristicsl. Similarly, 12 percent of all Black occupied hous-

ing units have overcrowded conditions (more than one person Per

room) as opposed to only one percent of Whj-te occupied housing uni

(Table 33, Id. ) .

Dr. Loewen testified that these demographic disparities arose

directly out of Mississippi and Hattiesburg's "history of racial

discrimination" (R 79). Dr. Loewen stated, in part:

There is a history of raciaL d'iscrimination,

getting back into slavery. . .untiI, reaIly,

the present. . . under segregation, Blacks

were not allowed among occupations, Blacks

rdere not allowed in many schools in Mississippi,

such as the medical school and so ollr up until

the recent past. . .In other words, raciaL

d,iscrimination in employment, in education,

in housing, and thatrs what lies behj-nd these

statistics. (79-80).

As a result of these socio-economic dJ-sparities, Dr. Loewen testi-

fied, Blacks have "substantiall.y less access" (R 82) to the polit-

ical process because of their lack of income and ed,ucati.on. Dr.

Loewen stated, in Part:

The political process. . .certainly is made

easier by having money available, .having

an automobiLe that you can drive to the pol1s

in, having enough money land education for]

the daily newspapers so that you know there

is an election, who the cand,idates are, and

have gotten involved in some of the issues,

or having money to give to campaigns. So

the Black office-seeker is going to be so

much less likely to get. . .contributi.ons

from people whose family income is $3 ,'772,

compared to the White office-seeker. . ..

Certainly the access -to the poj-itical

process is more difficult for Blacks than

Whites in Hattiesburg accord.ing to these

socio-economic statistics (n 82).

Loewen aLso stated that the- d,epressed socio-economic s"atus tea::ea

the ability of the Black community to effectively participate in

the political process by making it more difficult for the B1ack

conrmunity to forn coalitions with White yoters (.R 83) and by caus-

ing an out-migration of Black young adults, thus red,ucing the Blac

percentage of the voting age population (n 74, 81-2).

In the instant case, the evid,ence is ove:*rhelming that

Hattiesburg Blacksr ES a result of massive historical discrimina-

tion, are at a serious'socio-economic disadvantage. In the contex

of the at-large electoral systen maintained in Hattiesburg, this

has resulted in.almost totaL preclusion of Blacks from effective

participation in Eattiesburg's political process.

The record before the Court is replete with evidence of racia

polarization and. racial animus in every election where there has

been either a B1ack candidate or a Black identified issue on the

battot. The extensive polarizat,ion and animus itself give rise

to the assumption that racial appeals were oceurring in aII those

elections (n 5L). '

The issue of racial appeals was dealt with directly in testi-

mony concerning the L979 citywide referend.um conducted on the ques-

tion of whether Eattiesburg should change from its €xisting

at-large voting form of government to a mayor-council form of

government with council members elected from single member riist=:icts

It was acknowledged by both supporters and, opponents that change ,r

to a mayor-council form would, probably result in the election of at

least one Black council member. Consequently, support for the

change to the mayor-council form of government was generally assoc-

j.ated with support for electj-on of a Black city official (e.9.

P. s5).

It is absolutely undisputed in the record that the actual

'voting in the 1979 referendum was severely polarized, along racial-

-25-

Iines. Dr. James Loewenrs analysis of the L979 election establis

that, by a 5-to-1 margin, Whites voted to reject the change and to

maintain the existing form of government which had previously fore-

closed Blacks from eLection to office. Conversely' Black voters

supported the change by a sirnilar 5-to-1 margin (n 43-44) , Exhibit

p IO5, IV p. 3). Dr. Loewen found a statistical correlation bet:eest

the percent of White voters who voted and the Percent of votes cast

against the change to district elections so high that, he testified

the correlati-on was "one of the highest correlation coefficients

that I or any other social scientiest has ever encountered (n 46-

47." On the basis of the racj.al polarization alone, therefore,

Dr. Loewen concluded, that'race is without a doubt the prinary

factor explaining the outcorne in this election" (n 51).

Dr. Jerry Eimelstein was accepted by the Court as a sociologi-

cal expert in the areas of minority group relations and content

analysis (n 592). Dr. Bi:nelstein testified regarding a content

analysis study he had made of the campaign lj-terature and rhetoric

used in the L979 referendum. In particular, Df,. Eirnel-stein testi-

fied that the rhetoric used by tlrose who supported maintaining

the existing at-large voting scheme made frequent reference to the

avoidance of nsectionalism" which would arise if a single-member

dj-strict representation scheme were enacted. Conmission supporters

raised the issues the "threat of fed,eral government or federaL

court intervention" anC attacked the supporters of the change to

,

single-meruber district elections as "outsiders". (n 508-612. Dr.

Himelstein compared the uses of these particular words and concepts

to the use of the same words and concepts in the explicit, overtly

racist and segregationist speeches made in the context of resist-

ance to school desegregation (n 515-624). He concluded on the

basis of the common use of these words and concepts that clear

racial appeals had been mad,e in 1979.

Dr. Himelstein testified there were also overt racial appeals

but that code word. references to race in the campaign vrere used,

more often because by the time of the L979 campaign, it had become

"unfashionable" to make overt racial or segregationist statements.

Thus , the more subtle code word devic e was the dominant lrEans

racial appeals were made to the referendum electorate (n 603-605).

There j-s also extensive evidence that these racial appeals

were suceessful. Several Whites, including Karen Fawcett (n 489-9

Lou Miron (n 520-220) , and Orazio Ciccarelli (n 537-39), testified

to incidents where other Whites expressed racially based opposi-

tion to the change to mayor-council form of government. Plaintiff

Eenry l{cFar1in, a Black, testified that he was personally subj

to racial slurs from White citizens while he campaigned for the

change (n 415-17).

Although Defendants presented testimony from individuals who

asserted they had not personally observed incid,ents of racial

appeal or influence, Defendants offered no evidence whatsoever to

refute the testi-urony that these incidents were witnessed by others.

l'loreover, both e:<grert witnesses who testified for the Defend,-

ants, historian William Scarborough and political scientist Richar

Hatcher, readi-ly conceded that racial considerations influenced

at least some of the voters in the election (n 879i R 786), and

agreed that the racial polarization of the vote was "obvious"

1/(n 889)

The parties have stipulated' that no black person has been

elected to the Hattiesburg City Corunission (StiPu1ation 5).

1/ An example of the existence of racial appeals in the campaign

was an exchange which occurred during a speech by the then Mayor

of llattiesburg to an all,-White audience at a Rotary Club luncheon.

Mayor A. L. "Bud' Gerrard addressed the Rotary Club in support

of maintaining the at-large-commission form of goverrrment shortly

before the August 7, L979 referend.um. Although the Mayor could.

not remember the exchange (p 76 at 10) r a Rotarian present, the

White administrator of the Hattiesburg Clinic, P.A., testified

that Mayor Gerrard affirmed that the mayor-council form was "justto get the nj-ggers in the government" (n 452-453) . The transcript

reads:

A. tal member of the [Rotary Club]

stood up and mad,e the remark

or asked the question lto the

l'layorl that werenrt there people

pushing the change [to mayor-counei]-ljust to get the niqrgers in government?

O. What happened after he made this remark?

A. The Mayor said, . weIl, he wasnrt

sure about that, but he supposed you

could, sav that.

-

O. Did the mayor in hj.s comments affi:m

or deny the truth of the statement rnad,e

by the question.

A. Wel1, from my point of vj-ew lthe

MavorJ af f irmed it.

-'O. Did the Mayor criticize---make any

comment about the use of the word

"nigger" by the questioner?

A. None whatsoever.

(n 452, 453) (emphasis added)

Furtherr Do BLack person has ever been nomlnated in a party prima

to run for city government office (Stipulation 5). There has been

't

one Black candidate for office, Quincy Dent, in 1977. He was

defeated, in an election characterized as racial bloc vot5.ng, by

the City Commissioner, W. U. Sigler

The statutory language of the new S 2 states that a signifi-

cant factor to be considered in determining whether minorities

have less opportunity to participate in the political process is

" [the] extent to which members of a protected. class have been

elected to off ice in the Stat,e or political subdivision. . ."

96 Stat. at 134). ALthough the election of minority candidates

does not preclude a finding of a S 2 violation (Senate Report at

29 n. 115) , the failure of any Black candid,ates to win election

under an at-Iarge election system, given racial bloc voting, pro-

vides strong evidence that BLack citizens in llattiesburg "have less

opportunity. . .to elect representatives of ,,thelr choice" (95 Stat.

at 134).

According to the 1980 Census, the Black corununity conprised

34t of the population of the City of Hattj.esburg, 29* of the

voting age population (1980 Census of Population, Gen. Pop. Char.

Table 32) and an average of 20t of the actual voters turning out

in elections (P 105. II), It is further established that the

Black community has been approximately 30t of the population of

the City since it adopted the conunission form of government in

1910 (n 902). Because of its distinct socio-economj.c status,

Hattiesburg's Black community is an identifiable socio-economic

grouping (n 80-8L) with distinct political goa1s, and is therefore

-29-

a politically identifiable group G 811.

Since this poU.tically identifiable. group comprises nearly

3Ot of the voting age population of Hattiesburg the Court is of

the opinion that members of this group, if given the opportunity,

would have been elected to Hattiesburg municipal. office in the 73

years since the conurission form of government was estabU.shed in

1910.

The fact that none have been is evidence of the discriminato

Eatti.esburg offi-nature of the at-Iarge election scheme by whi-ch

cials are elected, (96 Stat. at 134) .

Under the S 2 "results" test, evidenee of unresponsiveness

is not required, for proof of a violation. Senate Report at 29 n.

1L5, [1982] U. S. Code Cong. & Adnin. News 207, cf . Zi-nnrer v.

l4cKeithe4, 485 F.2d L297 ,, 1306 (5ttr Cir. 1973) (en banc) , aff 'd

other grounds sub nom., East Carroll Parish School Board, v.l,1arshalL,

424 U. S. 636, 95 S.Ct. 1083, L.Ed. 296 (19761(absence of evidence

of unresponsiveness "not d.ecisive" to showing a denial of equal

4/ :

access to the political process.)-' On the other hand, evid,ence

of insensitivity or unresponsiveness can serve to strengthen a

plaintiffrs case that "the challenged electoral scheme has had the

effect of depriving minority members of equal representation. . .'

Cross v. Baxtert 604 F.zd 875, 882 (5th Cir. 1979).

4T

See also, Rogers v. Lodge, supra. In determining whether an

at-Iarge election system was maintained for purposes of discrimin-

ation, the Supreme Court specificalJ-y disapproved the appeal court

holding that proof of unresponsiveness was an essential element

of a vote d,j-lution claim under the Fourteenth Amendment, 73 L.Ed.

2d at 1023 n. 9.

-30-

In the instant case thene is evidence that Hattiesburg

officials have been unresponsive to the needs of the BLack commun-

ity by, inter alia:

a. Failing to eradicate past racial discrimina-

tion without litj.gation;

b. Failing to aPPoint Blacks to municipal

boards and commissions or othervise

involve them in municipal policymaking;

c. Being ind,ividually hostj.le or insensitive

to Black needs; and

d.ProvidinginferiorcityservicestoBlack

Eattiesburg residents.

Each area will be dealt with separately:

Ex-Mayor and party defendant Gerrard adsritted that the City

of Eattiesburg had maintained, racially segregated public schools,

fire department, police department, cemeteries, recreation facil-

ities, public bathrooms, drinking fountains, public buses, court-i

room seats, among other areas, until the late 1950s and generally

until at least 1973 (p 2L, P 29-32). These admissions are gener-

ally consistent with facts that this Court can take judicial noti-

of regarding the his,tory of the state of Mississippi (p 80 and 81,

Admissions, set forth many of the Mississippi statutes requiring

segregation) . Furthermore, these discriminatory practices ended

I

only after the passage of civil Rights Acts and litigation, and

many have been replaced by policies which have tended to maintain

a Status quo where B1acks continue to be disadvantaged'

The public schools of Hattiesburg, pursuant to statute, were

segregated by race until long after Brown v. Board of Education

in 1954. As the superintendent of the Eattiesburg Public Schools

Dr. Spinks testified, a freedom of choice plan was phased in from

I

I,!

I

the 1954-65 school year through the L966-67 school year (p 87, 88,

Adgission 73, 74, 75) but failed to produce adequate d,esegregation

The Hattiesburg Pub1ic Schools vrere, in 1970, finally desegregated

pursuant to Consent Decree, Order and SuppJ.emental Order of the

United States Federal District Court for the Southern District of

t{ississippi (P 63, 64,' 55). These Orders did not reguire the bus-

ing of elementary schooL children based on the assu:rances of City

officials that racial balance would be achieved by other means.

Nonetheless, student assignment to elementary school-s has remained

substantially segregated (Reports tc the Court filed pursuant to

the above-described Orders in United States of Anerica v. the

State of t4ississippi, Civil Action No. 4706 (Hattiesburg l"lunicipal

School Districtr surnnrarized by P 87 and 88, Admission 81, Exb. D).

The llhttiesburg Police Department was also the subject of a

successful federal Court challenge to discriminatory employment

practices, Alvin Eaton, et a1 v. Citv of llattiesburq (Judgrment

l

entered. Jan. 24, 1975) (P 62). That Defendants may have comPlied

witfi this Court Order does not disprove unresPonsiveness: nTo the

extent that this evidence tend.s to prove anything, it is that

litigation was reguired to remove discrimination in lthis) impo

area, and that litigation has worked. "

Supervisors of HindP Countv, llississippi, EE, 554 F.2d at 146-

lloreover, notwithstanding litigation, Black employment by the

City renains disproportionately low in jobs of responsibility, high

pay and other areas. Specifically, the City of Hattiesburg has

ad'mi-tted that in L977 al1 department heads of the ciQr of llattieshlrg

were White, with no Black having held any of these positions

(p 87, 88, Admission 17) . Further, the City admitted to the

-32-

following facts tP 87, 88, Admission 71):

1. AlL 60 employees earning a base salary

of more than $101000 in 1977 not includ.-

ing overtime, were White;

2. That all 28 official administrators of

the City of Hattj.esburg $rere White;

3. That of 5L office and clerical workers,

48 were Whit,e;

4. That of the 89 full-time employees of

the Fire Department, 87 were White;

5. That of the 84 full-time employees of

the Police Department, 74 were White.

The Housing Authority of the Cj.ty of Flattiesburg has operated

two projects which were segregated by race, one for Blacks and one

for Whites, and which remained segregated until one Black family

moved into the Whj.te project in L979. (Judicial notice, Deposition

of Bi11ie W. O'NeaL, Executj.ve Director Of the Housing Authority

of the City of Hattiesburg filed in this cause).

Similarly, as llayor Gerrard testified,, although in the 1970s

the City stopped reguiring ttre segregation of cemeteriies, the

practice since that time has resulted in maintaining the status

quo of segregated cemeteries (p 2L at P 29). Also, the current

City Ordinances require all common carriers to have separate facil-

ities for White and, Black races (p 74 S 15-52-1). Furthermore, it

remains a misdemeanor for any person of the White race to use rooms

provided for the Colored race and for any person of the Colored

race to use rooms provided for the White race (p 74, S 15-52-.2-4).

Finally, S 15-45 of the City Code adopts all State misdelneanors,

which have. included many discriminatory laws (p 80-81).

In regard,s to appointments to boards and conunission, !{ayor

.Gerrard testified that there was no Black member of a city eqrudssicrt

-??-

prior to his first election as City Comrnissioner in L972 (p 2L at

75). Although the segregation of these Board,s ended,r Ers of Jaru:ar1z,

1978 the complete list of appointments to boards and conunissions

made by the City Cornmission of Eattiesburg totaled. fifty-six

appointments , ef which only f ive were Bl-ack (p 87 , Ad.mission L2) .

Thus, alti:ough the Black population of Eattiesburg was approxi-

mately thirty percent (30*), the appointments to board,s and com-

missions consisted of approximately eight percent (88) Black.

Even in 1980, Mayor Bobby Chain testified that, the City boards

and commissions totaled sixty-three appointments. of which only

ten (10) h,ere Black (n 961 P (2). Thus, even in 1980, fifteen

percent (15t) of the Cityrs appointments to board,s and, commissions

were Blackr dn und,er-representation of almost 100 percent (1008).

Furthermore, these figures do not include the members of the

Mayor I s Committee f or Downtown Revitalization f omed, in 19 80

(n 962) which consisted of one Black out of tweLve to eighteen

members (n 962) .

Commissioner W. u. Sigler previously served, as a Supervisor

of the Forrest County Board of Supervisors from 1965 until- L974,

and in that capacity was a Defendant in the suit titled United

States v. Board of Supervisors of Forrest Countv, Mississippi,

875-71(C) of the Southern Distr:-ct of Mississippi. the suit

was finally d,ecid,ed by the Fifth Circuit which held that the

Forrest County Board, of Supervisors d.istrict boundaries perpetua-

ted the denial to Blacks of equal access to the polj-tica1 process.

- 34-

United States v. Board of Sup. of Forrest Ctv., supra (p 30).

Commissioner Sigler testified as follows:

Q: Did you know that the NAACP had

endorsed the mayor-council form

of government?

A: Donrt know and donrt care.

***

O. Do you know whether or not Blacks

were allowed to vote in 1910?

A. Donrt care.

***

O. So how long have you lived. in

Hattiesburg?

A. Sixty-one years.

O. All right, and are you avrare during

your 61 years that there is any form

of racial discrimination?

A. Not particularly, no.

***

O. And isn't it true that the two

Blacks who won office lin L979)

were Percy Watson and Deborah

Garnbrell from . they won

from Forrest County?

A. As far as I know, those are

the two, y€sr sir.

-35

And isntt it true that both '-hose d,istricts

that they ran for office in were created by

court order after redistricting suits srere

brought?

. been going on L2 or 15 years for a

total waste of taxpayerrs monev.

***

Were you aware that in the referendum c'anpaign

of L979 regard.ing the form of city governnent

that integrating city government was the issue.

WelI, it wasn't on my part. It might have

been on the opponents' , but it wasn I t on my

part. I eouldn't care less.

lP 77 at 6-Ul) (eplrasis added)

Dr. Gordon Henderson, a polit,ical scientist, recognized

specifically as an expert in politicaL attitudes and behavior

(n L55), .concluded from examination of Commissioner Sigler's testi

IDOD! r

I can I t think of anything better designed

to tell a B1ack person that this is not

a responsive municipal government.

I t d like to f ind a Bl-ack person who is

asrare of ttre reapportj-onment matters who

can say that those suits were a waste of

the taxpayersr money. , . .these statements

are realIy, truly, preposterous. . . (R 174-175).

Dr. Henderson's analysis of these statements is unrebutted in the

record, and simply states the obvious: Cornrnissioner Sig1er has

clearly in the past been insensitive and, unresponsive to the Black

community.

In regards to the provision of City services, the Defendants

have admitted and Conunissioner Williamson, a party Defendant, has

testified, that of the complaints received regard,ing city services

by hirn, approximately one-half comes from the Black conununity.

Since the Black community comprises onLy one-third of llattiesburg's

Q:

A:

Q:

A:

-3 5-

population, this means that Black citizens are having to complain

about services significantly more than the White communi,ty (p 87

and 88, Ad.mission 110). Secondly, an examination of Eattj.esburg,

l'lississippi Comprehensive Plan #8, Neighborhood Analysis, 1965

(p 85), reveals that the neighborhood enumeration d.istricts iden-

tified as BLackr or predominantly B1ack, (P 84-85), have been

identified as the areas most lacking in city services such as

adequate d,rainage.

Taken together, the f oregoing evid,ence provides proof that

Hattiesburgts at-large election scheme violates S 2 of the Voting

Right.s Act, as amend,eC.

llississippi Law provid.es for several forms of municipal

government, none of which purports to reguire at-J.arge elections

except the commis s ion f orm, see lvlis s . Code Arrn . Title 2L. Only

six cities in the State of Mississippi operate und.er the commissi

f orm of government (n :..62') , and one of these has provid.ed for its

three cornmissioners to be elected by d.istriet rather than at-J.arge

(n 795). Thus, there is clearly no overalL policy of the State of

Mississippi that municipal goverrunents be' elected at-Iarge. Ind,eed

the only time the State of Mississippi ever exhibited a generalized

pol.icy in favor of at-large city elections was in L962 when, faced

with the prospects of Blacks regaining the right to vote, it

enacted Dtiss. Code Ann. S 21-3-7. That law required lulississippi

municipaLitj-es to change from ward election of al.dermen, council-

men and select:nen to at-large elections. The law was struck dor,m

under the Fourteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution "as a

purposeful device conceived and operated to further racial dis-

crimination in the voting process'. Stewart v. Vf,a1ler, 404 F.Supp.

206 (rl.o.l'llss.1975) (. 29).

-37 -

Political scientists agree that functj.onal justifications for

maintining the commission form of government with its at-large

elections are extremely tenuous. Dr. Richard Hatcher, who testi-

fied as the Defendants' expert witness stated, that,

""rra*",

scientists are hard

pressed these days to find very

many advantages in the commission

form of citir government, particu-

larly in view of the fact thatother more effective for:ms areavailable to the people. (n 794,

P 54).

Dr- Gordon Henderson, Plaintiffs t political scienee expert, testi-

fied that the trend i-n municipal government since ww Ir has been

"emphatically away from the rise of the conunj.ssion form and in

favor of the mayor-council and counciL-manager plans', (R L6z),

and t'hat this trend, was not surprising to political scientists

since the commission form, in comparison to either mayor-council

or councj-l-manager forms, is "neither particularly responsive nor

particularly responsible', (n IG33) .

Both exPert political scientists testified, that one of the

major recognized d.j-sadvantages of the comnrission form of govern-

ment is that its at-large electi.on scheme prevents ethnic or

racial minorities and their interests from being fully represented

in municipal government (n 796i R 1G5-166). Dr. Itenderson tes_

tified that the data regard,ing voting patterns in Hattiesburg

lead,s to the inevitable conclusion that this d,isad,vantage is

operative under Hattiesburg's at-large voting system (n 167), a

proposition with which Dr. Hatcher agreed (n 796).

The evidence is thus overwhelming that the policy und.erlying

Hattiesburg's election scheme is, at best, tenuous. The evid,ence

is absorutely uncontrad.icted, that the at-large elections result is

a barrier to Black participation in Hattiesburg government, in

viol-ation of S 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The evidence before

this Court amply establishes almost every element of proof out-

Iined by Congress as probative of a S 2 violation, except for

evidence of racial discrimination in slating. What this evidence

makes abundantly clear is that the maintenance of the at-large

election system in Eattiesburg, Mississippi has the effect of

leaving Blacks with less opportunj-ty than Whites to participate

in the political process and to elect representatives of their

choice.

This Court finds that the potential for dilution of minority

voting strength is inherent in any at-Iarge electoral system.

Plaintiffs have established, by the evidence presented that Hattiesburg

at-Iarge electoral scheme is being maintained in violation of S 2

of the VotJ.ng Rights Act and, this Court shall require the estab-

Iishment of a single merober district system for the City of

Hattiesburg.

As heretofore noted, l,lississippi Law provid,es for several

fo:ms of municipal government which do not require at-large elec-

tj.ons. Thj-s Court will not at this time attempt to d.ictate the

precise form of government to be utilized by the City of Hattiesburg

in converting to a single member d,istrict system. This decision

in the first instance is left to the duly eLected. representatives

of the people of this City, the Mayor and Conunissioners, to pre-

sent a proposal acceptable to the Plaintiffs, the Court, and most

irnportantly, the people of the city of Hattiesburg. The

are directed to confer and thereafter report to the court

parties

proposals

- ?o-

itr for accomplishing the reguirements of this decision.

This Court wil1, Qf course, oversee the transition in form

of governnent to assure that one Iegally infira system is not re-

placed by another also violative of S 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

or one in which by racial gerrymandering of geographical districts

accomplishes the same unlawful results found in the present system.

This Court is fully aware that thj-s opinion may not be well-

received by all citizens of the city of Eattiesburg and may be

cited, by many as another example of Federal Court medd,ling in

loca1 affairs. The court would hope, however, that the majority

of the citizens of this City look upon this decision as an oppor-

tunity to finally and forever erad.icate both past and present

vestiges of racj-al discrj:nination and seek a new beginning in race

relations. In weighing the merits of this decision a citizen

should attempt to place himself in the shoes of the minority voter,

comprisi.ng 34t of the population of this city, who has not had a

meruber of the Black race to represent him in City government d,uring

the 73 years the Mayor-Commission form has been in effect. Aside

from the legaI reguirements of S 2 of the voting Rj.ghts Act, a

dissatisfied citizen should ask himself whether this results is

faj.r to one-third, of the citizens of this City. If the situation

hrere reversed, and the now majority White population of the City

comprised only one-third of the electorate, would, not the Vfhite

community be seeking in this Court the same type relief no$r re-

guested by the Black conununity?

This Court d,oes not intend by these rernarks ;" encouragie

racial bloc voting. ?he evidence is over:whelming, however, unfor-

tunately such is the case not only in this City but throughout the

-dn-

a

nation. It is the hope of this Court that one day the voters of

this country, both Black and White, wilL judge a cand,id,ate by his

gualifi-cations and not by the color of his skin. When this occurs,

vre as a nation will have achieved true democracy.

A Judgrment in accordance with the :hove findings shall

submitted to the Court within the tj:ne a.nd, manner prescribed

be

by

the Ru1es. \t^

^qvTHIS the cL t day of ,1984.

- 4I-