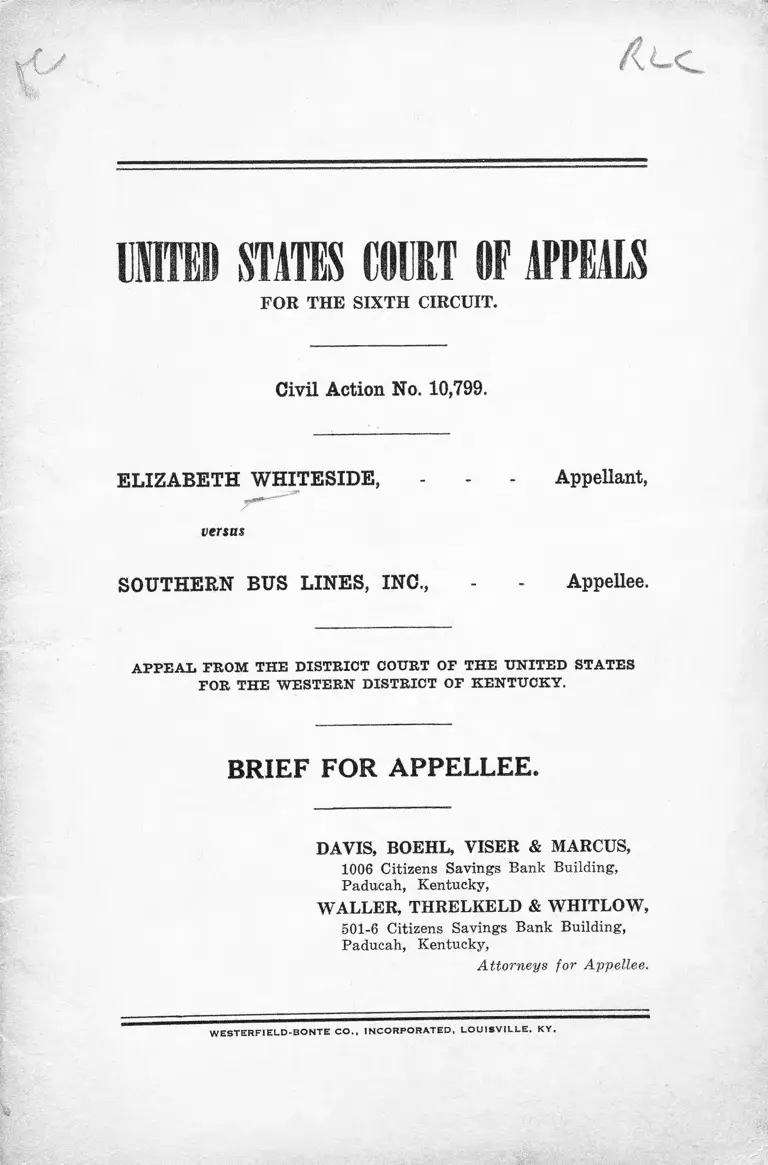

Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, Inc. Brief for Appellee

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, Inc. Brief for Appellee, 1948. 58da130b-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8b52a9c3-5f8e-4cbd-9336-7d4a542906cc/whiteside-v-southern-bus-lines-inc-brief-for-appellee. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

/ t ^ - c

l\ m :n S T M S M E T HP APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT.

Civil Action No. 10,799.

E LIZAB ETH W H ITE SID E, - - - Appellant,

versus

SOUTHERN BUS LINES, INC., - - Appellee.

A P P E A L FR O M TH E D ISTR ICT COURT OF TH E U N IT E D STATES

FO R TH E W E STE R N D ISTR ICT OF K E N TU C K Y.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE.

DAVIS, BOEHL, VISER & MARCUS,

1006 Citizens Savings Bank Building,

Paducah, Kentucky,

WALLER, THRELKELD & WHITLOW,

501-6 Citizens Savings Bank Building,

Paducah, Kentucky,

Attorneys for Appellee.

W E S T E R F IE L D -B O N T E C O . , IN C O R P O R A T E D , L O U IS V IL L E . K Y .

COUNTER-STATEM ENT OF QUESTIONS INVOLVED.

1. Did appellee, as a common carrier of passen

gers by motor bus in interstate commerce, have the

right and duty to establish reasonable rules for the

safety, comfort and convenience of its passengers'?

2. Was the rule of appellee at Wiekliffe in West

ern Kentucky, providing for the loading of white

passengers from the front and colored passengers from

the rear of the bus, reasonable for the safety, com

fort and convenience of the passengers'?

I N D E X

PAGE

Counter-Statement of F a c ts ................................................... 1

Argument:

1. Did appellee, as a common carrier of passengers

by motor bus in interstate commerce, have the

right and duty to establish reasonable rules for

the safety, comfort, and convenience of its pas

sengers ? ............................................................... 3

2. Was the rule of appellee at Wickliffe in Western

Kentucky, providing for the loading of white

passengers from the front and colored passengers

from the rear of the bus, reasonable for the

safety, comfort, and convenience of the passen

gers ? .................................................................... 9

3. Appellant’s Argument and Authorities are not

Applicable.............................................................. 12

Conclusion 17

TABLE OF CASES.

PAGE

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28,

92 L. Ed. 455....................................................... 14

Brumfield v. Consolidated Coach Corp., 240 Ky. 1,

40 S. W. 2d 356................................................... 6,10

Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio R. Co., 218 U. S. 71,

54 L. Ed. 936.................................................. 5,10,15

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485, 24 L. Ed. 547. .5, 7, 9,14,15,16

Henderson v. Interstate Commerce Commission, 80

Fed. Supp. 32.......................................... 14

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24, 92 L. Ed. 1187............... 14

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373, 90 L. Ed.

1317............................................................ 7, 12, 14, 16

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, 41 L. Ed. 256......... 9

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 92 L. Ed. 1161...........13,15

Simmons v. Atlantic Greyhound Corp., 75 Fed. Supp.

166............................................. ...................... 7, 12, 16

Table of Statutes.

Federal Constitution Art. 1, Sec. 8.............................. 5

49 USCA Sec. 316 (a).................................................. 7

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT.

Civil Action No. 10,799.

E lizabeth W hiteside, - Appellant,

v.

Southern B us L ines, I nc., - - - Appellee.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE.

COUNTER-STATEM ENT OF FACTS.

This action was initially instituted as a civil action

for damages arising out of the eviction of appellant,

an interstate passenger, from a motor bus of the ap

pellee at Wickliffe in Western Kentucky. In this ac

tion, recovery was sought for personal injury and

property damage. On the trial of the case before

the Judge of the District Court, appellant, by the

direct evidence of a local colored physician (R. 56)

and the deposition of two colored doctors of St. Louis,

Missouri (R. 22), failed to connect any substantial

2

physical injury to the alleged eviction. In fact, ap

pellant testified that after completing her trip to

Paducah, Kentucky, on the day of the incident com

plained of, she saw her lawyer long before she saw

her doctor (R. 104). The cause was submitted in the

District Court principally upon the alleged technical

invasion of appellant’s rights, there being no sub

stantial proof that excessive force was used or that

there was malice or improper conduct on the part of

any of the agents or servants of the appellee.

The proof of appellee before the District Court

was to the effect that there was in force at Wick-

iiffe in Western Kentucky a rule of appellee that

colored passengers would be loaded from the rear of

the bus and white passengers from the front. The

reasonableness and necessity for this rule were proved

by Mr. Martin Robinson (R. 157-162), the Town

Marshall of the City of Wickliffe; Mr. Jesse Sullivan

(R. 171-173), Sheriff of Ballard County, Kentucky,

of which county Wickliffe is the county seat; Mr.

L. E. Carter (R. 178-180), County Judge of Ballard

County, Kentucky; Mr. J. B. Martin (R. 125-130),

driver of appellee’s bus; and by Mr. F. S. Keaton (R.

151), vice-president and general manager of all of

appellee’s operations east of the Mississippi River.

There was no proof to the effect that this rule was not

reasonable or necessary for the safety, comfort and

convenience of the general traveling public at W ick

liffe, Kentucky.

There appears to be a typographical error in the

statement of facts in appellant’s brief in that it is

3

stated on page 1 that appellant’s motion in the Dis

trict Court to set aside its decision and judgment was

overruled on June 28, 1949, when, in fact, said motion

was overruled on June 28, 1948.

There being no proof clearly connecting any sub

stantial injury with the eviction complained of, but

little proof of excessive force or malice in. connection

with the eviction, and no proof to counter appellee’s

proof that the rule of appellee was reasonable and

necessary for the safety, comfort and convenience of

the general traveling public, this cause was submitted

to the District Court, as can be readily seen from the

entire context o f appellant’s brief, on the mere claim

that any rule providing for the separate seating of

white and colored passengers is per se invalid.

ARGUMENT.

Did Appellee, As a Common Carrier of Passengers by

Motor Bus In Interstate Commerce, Have the Right

and Duty to Establish Reasonable Rules for the

Safety* Comfort and Convenience of Its Passengers?

THE D ISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY AN

SW ERED—YES.

When appellee dedicated its property as a common

carrier to the service of the general traveling public,

it assumed one of the most rigid obligations known to

the law. Common carriers of passengers for hire have

always been required to exercise the highest degree of

care for the safety, comfort and convenience of their

4

passengers. Pursuant to this duty, it is, and was at

the time of the incident complained of by appellant,

incumbent upon all carriers—including appellee—to

inform themselves of their duties under the laws then

in force and to inform themselves as to all facts which

affected the performance of their high duty of care

to their passengers and to adopt such measures, con

sistent with the laws and facts, as would he reason

ably expedient in carrying out their duties to the gen

eral traveling public. So long as appellee remained a

common carrier, it had no choice in this matter, but

was required at its peril to faithfully and capably

carry out these duties.

This high duty to the general traveling public was

of primary concern to appellee and it could have had

no other interest in the seating of its passengers. The

seating arrangement, as well as all other matters re

lating to the conduct o f its business, was not a matter

to be determined according to some whim or fancy

of appellant (it being far easier to pay no attention

to the seating of passengers than to make an effort to

supervise some orderly arrangement), and any action

which appellee may have taken in this connection

could have been no more than its sincere judgment as

to what, in its opinion, was reasonably necessary to

discharge its exacting duties. Under the proof in this

cause, appellant cannot claim, and, in fact, she does

not claim in her brief, that appellee had any personal

or malicious motive in the promulgation and enforce

ment of its rule relative to the seating of white and

colored passengers.

5

The foregoing principles are abundantly sup

ported by current authorities in Kentucky and in

Federal Jurisdictions. Under the Constitution (Art.

1, Sec. 8), the regulation of interstate commerce is

vested exclusively in Congress and it has long been

settled that the failure o f Congress to act within this

exclusive area is equivalent to a declaration that com

merce shall be free from legislative regulation and

that, in the absence of regulation by Congress, car

riers are free to, and are required to, adopt reasonable

rules for the conduct of their business, and to insure

the safety, comfort and convenience of their passen

gers. In the case of Chiles v. C. & O. Railroad Com

pany, 218 U. S. 71, 54 L. Ed. 936, the Court discussed

and quoted from the earlier case of Hall v. DeCuir,

95 U. S. 485, 24 L. Ed. 547, as follows:

“ In Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485, 24 L. Ed.

547, the court passed on an act of the State of

Louisiana, which required those engaged in the

transportation of passengers among the States

to give all passengers traveling within that State,

upon vessels employed in such business, equal

rights and privileges in all parts of the vessel,

without distinction on account of race or color,

and subjected to an action for damages the owner

of such vessel who excluded colored passengers on

account of their color from the cabin set apart

for whites during the passage. It was held that

the act was a regulation of interstate commerce

and was void. The court said, by Chief Justice

Waite, after stating that the power of regulating

interstate commerce was exclusively in Congress,

‘ This power of regulation may be exercised with

6

out legislation as well as with it.’ And that, ‘ by

refraining from action, Congress, in effect, adopts

as its own regulations those which the common

law or the civil law, where that prevails, has pro

vided for the government of such business.’ The

court further said, quoting from Welton v. Mis

souri, 91 U. S. 282, 23 L. Ed. 350, that ‘ inaction

[by Congress] . . . is equivalent to a declara

tion that interstate commerce shall remain free

and untrammeled.’ And added: ‘Applying that

principle to the circumstances of this case, con

gressional inaction left Beason [the shipowner]

at liberty to adopt such reasonable rules and

regulations for the disposition of passengers upon

his boat while pursuing her voyage within

Louisiana or without as seemed to him most for

the interest of all concerned. ’ This language is

pertinent to the case at bar, and demonstrates

that the contention of the plaintiff in error is

untenable. In other words, demonstrates that the

interstate commerce clause of the Constitution

does not constrain the action of carriers, but, on

the contrary, leaves them to adopt rules and regu

lations for the government of their business, free

from any interference except by Congress.”

The power and duty of common carriers to adopt

reasonable rules is also well-settled in Kentucky. In

the case of Brumfield v. Consolidated Coach Corpora

tion, 240 Ky. 1, 40 S. W. 2d 356, the Court stated:

“ A carrier of passengers not only has the

power, but it is its duty, to adopt such rules and

regulations as will enable it to perform its duties

to the traveling public with the highest degree of

efficiency, and to secure to its passengers all pos

sible convenience, comfort and safety.” (Citing

numerous authorities.)

In the more recent Supreme Court case of Morgan

v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373, 90 L. Ed. 1317, the case of

Hall v. DeCuir was cited and reaffirmed.

The only regulation of the seating of interstate

passengers which has been undertaken by an Act of

Congress appears in 49 U. S. C. A., Section 316(a).

This subsection provides in part as follows:

“ It shall be the duty o f every common carrier

of passengers by motor vehicle to establish rea

sonable through routes with other such common

carriers and to provide safe and adequate serv

ice, equipment, and facilities for the transporta

tion of passengers in interstate or foreign com

merce; to establish, observe, and enforce just and

reasonable individual and joint rates, fares, and

charges, and just and reasonable regulations and

practices relating thereto, and to the issuance,

form, and substance of tickets, the carrying of

personal, sample, and excess baggage, the facil

ities for transportation, and all other matters re

lating to or connected with the transportation of

passengers in interstate or foreign commerce;

The recent case of Simmons v. Atlantic Greyhound

Corporation, 75 Fed. Sup. 166 (Dec; 30, 1947), in

volved facts almost identical with those in the present

case, and the Court upheld the enforcement by a motor

bus carrier of a rule providing for the seating of white

passengers from the front and the colored passengers

from the rear. The Court recognized that the legis

lative regulation of the seating of interstate passen

gers was exclusively within the control of Congress

and that no regulation had been enacted by Congress

except the above-mentioned statute which required car

riers to adopt reasonable rules on the subject, and the

Court stated:

“ The fact remains that neither Congress nor

any agency created by it has sought to impose

any regulation dealing with the separation of

passengers in interstate commerce. The fact that

such separation has long been enforced in a num

ber of States by custom and by the rules of com

mon carriers operating in such States is a matter

of public knowledge of which the members of

Congress are fully aware. In fact, although

efforts have been made over some years to induce

Congress to enact legislation on this subject, it

has consistently refused to attempt such regula

tion. There can be no other inference than that

Congress has thought it wise and proper that the

matter should be left for determination to such

reasonable rules as the carriers might themselves

adopt and that it considered that rules providing

for the segregation of passengers in those sections

where they were applied were reasonable ones.

By its refusal to nullify the practices and regu

lations of these carriers in respect to the separa

tion of passengers, Congress has by the strongest

implication given its approval to them. This is

a field of Congressional duty and responsibility.

This court cannot invade it and, by usurping the

powers of Congress, lay down rules by which this

9

defendant must guide the operation of its busi

ness—rules which Congress, in, the exercise of

power specifically and solely entrusted to it, has

refused to lay down.”

From the foregoing, it is evident that appellee, as

a common carrier of passengers by motor bus in inter

state commerce, has not only the right but the positive

duty to establish reasonable rules for the safety, com

fort and convenience of its passengers.

W as the Rule of Appellee At Wiekliffe in Western Ken

tucky, Providing for the Loading of White Passen

gers From the Front and Colored Passengers From

the Rear of the Bus Reasonable in Order to Promote

the Safety, Comfort and Convenience of the Passen

gers?

THE D ISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY AN

SW ERED—YES.

Appellee, on the occasion complained of by appel

lant—on May 6, 1946—was operating under the prin

ciples of law announced in the early case of Hall v.

DeCuir, supra. These principles have been reaffirmed

many times. In fact, appellant in her brief (pp. 28-

35) does not contend that these principles have been

overruled by any decision of any Court, or any Fed

eral statute regulating interstate commerce, but

appellant complains merely of, “ the synical sophistry

of Justice Brown,” the Supreme Court Justice who

delivered the opinion in the case of Plessy v. Ferger-

son, 163 U. S. 537, 41 L. Ed. 256, which case reaffirmed

10

the principle that separate seating of white and

colored passengers was not a violation of any con

stitutional right. Furthermore, in the above cited

Chiles case, the Court stated:

“ We have seen that it was decided in Hall v.

DeCuir that the inaction of Congress was equiva

lent to the declaration that a carrier could, by

regulations, separate colored and white interstate

passengers. ’ ’

The Court further stated:

“ The opinion, of the court, which was by Mr.

Justice Brown, reviewed prior eases, and not only

sustained the law, but justified as reasonable the

distinction between the races on account of which

the statute was passed and enforced. It is true

the power of the legislature to recognize a racial

distinction was the subject considered, but if the

test of reasonableness in legislation be, as it was

declared to be, The established usages, customs,

and traditions of the people,’ and the ‘ promotion

of their comfort and the preservation of the pub

lic peace and good order,’ this must also be the

test of the reasonableness of the regulations of a

carrier, made for like purpose and to secure like

results. Regulations which are induced by the

general sentiment of the community for whom

they are made and upon whom they operate can

not be said to be unreasonable.”

Also in the Kentucky ease o f Brumfield v. Consoli

dated Coach Corporation, supra, the Court stated:

“ We know of no rule that requires a common

carrier of passengers for hire to yield to the dis

11

position of passengers, arbitrarily to determine

for themselves as to the coach or vehicle in which

they may take passage. They are entitled to be

transported within a reasonable time without dis

crimination and without favoritism or partiality,

but are without right to select the coach or vehicle

or the seat thereon which they wTill occupy.”

On the trial, appellee produced abundant proof by

leading citizens and public officials of Wickliffe, Ken

tucky, who testified as to the reasonableness of, and

necessity for, the separate seating of white and colored

passengers at Wiekliffe, Kentucky. The proof was

based upon their observations and experiences in this

community. It was also proved by the driver, and

the vice-president and general manager of all opera

tions of appellee east of the Mississippi River that

such a rule was reasonably necessary to promote the

safety, comfort and convenience of the passengers.

Kone of this proof was contradicted. Appellee was

presumed to, and did, know the customs and general

sentiment of the people at Wiekliffe, Kentucky, and,

as a common carrier, it was required to make some

decision relative to the seating of its passengers. I f it

had failed to make or enforce any regulation and had

been faced with an action for damages as a result of

this failure, it would have been met with the same

proof which it produced upon the trial of this ease,

and, in such event, could it have been heard to say

that it was diligent in promoting the safety, comfort

and convenience of its passengers?

12

The separate seating of white and colored passen

gers having been repeatedly upheld by the Courts as

being reasonable and the proof of the necessity of such

seating arrangements at Wicklitfe, Kentucky, being

uncontradicted, the rule o f appellee was clearly rea

sonable.

Appellant’s Argument and Authorities Are Not

Applicable.

Appellee is here defending an action which was in

stituted as a civil suit for damages arising under facts

where appellee was discharging its duties as required

by the laws in force at the time complained of by ap

pellant. A reading of appellant’s entire brief evi

dences appellant’s conviction that the controlling

cases sustain appellee’s position, but after complain

ing of, “ the synical sophistry of Justice Brown”

(p. 28), appellant argues that the prior eases (which,

incidentally, are reaffirmed as late as Morgan v. V ir

ginia (1946); and Simmons v. Atlantic Greyhound

Corporation, supra (1947)) are outmoded by present-

day thinking. Appellant has apparently converted

this action from a civil suit for damages to a vehicle

by which she hopes to obtain some ex post facto judi

cial legislation at the expense of appellee. It is un

fortunate that appellee, having diligently followed all

reasonable requirements of which it could have been

apprised at the time complained of by appellant,

should be required to participate in this crusade. In

the Congress appellant has the only forum to which

she can direct her complaint.

13

In the learned brief for appellant, a great number

of propositions are advanced and a great many au

thorities are cited and discussed which we feel are not

applicable, and we shall not undertake to discuss all

of them in detail.

It is contended that the ejection from appellee’s

bus and the upholding of the rule of appellee by the

Federal Court was action of the State and Federal

governments and not the act of a private party (pp.

6-11). I f such ejection should be held to be not the

individual action o f appellee, we do not understand

how or why appellee should be here defending a claim

for damages in this litigation, or why appellant filed

this suit. We have always understood that judicial

issues should be limited to conduct complained of

against parties to the litigation, and it would seem that

appellant’s claim that the eviction was the result of

State and Federal action would per se relieve appellee

of any responsibility in this connection and entitle ap

pellee to an affirmance of the judgment dismissing the

cause as to appellee.

There is also a scholarly, but we think irrelevant,

treatment of the effect of judicial decisions as govern

mental action within the prohibitions of the Fifth and

Fourteenth Amendments (pp. 11-20). The author

ities referred to in support of these propositions, how

ever, deal with situations where judicially recognized

constitutional rights were involved. In the leading

case on restrictive covenants, Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. 1, 68 Sup. Ct. 836 (1948), and the other cases of

this type, the Court was dealing with the fundamental

14

rights relating to the ownership and occupancy of real

property and the basis for the decisions was that this

was one o f the constitutional rights which could not be

violated. Appellant recognizes this in her brief (p.

11) when she refers to the case of Hurd v. Hodge as

holding that a “ discriminatory” regulation or cove

nant could not be enforced by an agency of the Fed

eral Government.

In attempting to establish an analogy to the pres

ent case, appellant has failed to recognize that the

courts have uniformly, since the DeCuir case in 1878,

held that a passenger has no vested right to any par

ticular seat on a common carrier, but that his only

right is that he shall have equal accommodations with

others and that there shall be no discrimination and,

further, that providing for separate seating of white

and colored passengers is not discrimination. In the

present case, there can be no question of denial of the

service of a common carrier for, if the rule as to

separate seating was valid, then refusal of a passen

ger to abide by the rule would automatically terminate

his right to remain on the bus. Appellant’s argu

ments and authorities in this connection, therefore, are

not applicable here since there has been no discrimina

tion and no invasion of appellant’s constitutional

rights.

In the recent case of Henderson v. Interstate Com

merce Commission, 80 Fed. Sup. 32 (Sept. 1948), the

Court reviewed the leading cases cited in appellant’s

brief, such as Morgan v. Virginia, 328 H. S. 373,

66 Sup. Ct. 1050, 90 L. Ed. 1317; Bob-Lo Excursion

15

Company v. Michigan, 333 XL S. 28, 68 Sup. Ct. 358;

and Shelley v. Kraemer, together with the prior cases

of Chiles v. C. & O. Railroad Company and Hall v.

DeCuir, and stated:

. “ To summarize and conclude: (1) Racial

segregation of interstate passengers is not for

bidden by any provision of the Federal Constitu

tion, the Interstate Commerce Act or any other

Act of Congress as long as there is no real in

equality of treatment of those of different races.

(2) Allotment of seats in interstate dining cars

does not per se spell such inequality as long as

such allotment, accompanied by equality of meal

service is made and is kept proportionately fair. ’ ’

The dissenting opinion in this case was based on

the theory that the segregation rule upheld by the

majority of the Court would, in some instances, re

sult in denial of accommodations to colored people

when there were vacant seats, but even in this dis

senting opinion, the Judge stated:

“ Segregation in railroad traffic may be main

tained if there are sufficient accommodations for

all; but a vacant seat may not be denied to a pas

senger simply because of his race. The decisions

of the Supreme Court support this view.”

The rule of the appellee in the present case could

never deny accommodations when there were any va

cant seats, since it merely provides for the loading of

white passengers from the front and colored passen

gers from the rear. Under this rule, it would be

16

entirely possible that the majority, or even all, of the

bus could be occupied by colored people, and there

could be no question of denial of accommodations or

the invasion of any constitutional rights.

Reference is also made to the rule of appellee as

constituting a “ burden” on interstate commerce (pp.

36-49), and the case of Morgan v. Virginia is discussed

at length. It is true that the Supreme Court in that

case held that a State statute requiring segregation

was a burden placed on interstate commerce by the

State of Virginia, but it must not be overlooked that

this same case is based upon and reaffirms the holding

in the case of Hall v. DeCuir where a State statute was

declared invalid which prohibited the separate seat

ing of white or colored passengers. These cases,

then, cannot be construed to hold that separate seat

ing is a burden on interstate commerce, but only that

legislation by the State on the subject in either direc

tion is an invasion of the exclusive power of Congress.

This argument was made in the case of Simmons v.

Atlantic Greyhound Corporation, supra, and the Court

stated:

“ It is argued that the defendant is merely at

tempting to accomplish by a rule of its own the

same result which the State of Virginia sought to

accomplish by Statute; and that the defendant

cannot, by a company rule, do something which

the State could not lawfully do. This argument

misses the point. It assumes that the separation

of passengers on racial grounds has been held to

be unlawful under any circumstances. And it

17

fails to recognize the distinction between the ac

tion of a State in attempting to regulate the busi

ness o f a carrier in respect to matters which are

the sole concern of Congress, and the right of the

carrier to operate its own business subject to such

regulations as Congress may impose.”

CONCLUSION.

The plaint ill' and her counsel complain of and seek

to avoid a legal principle that has been unfailingly

and repeatedly upheld by the Courts since the DeCuir

case in 1878, and are evidently dissatisfied with the

idea that Congress through the years, could have, if it

would have, changed the rule and made it imperative

that the colored and white passengers be intermingled.

Whether Congress should have taken action in the

matter is not a part of this litigation. The fact is that

Congress has not taken any part in the matter and,

therefore, there is left upon this carrier, and all other

carriers, the obligation or duty in certain sections of

America to see that white patrons and colored patrons

are seated separately. The law still imposes upon the

carrier the duty of safe carriage of its white patrons

and the safe carriage of its colored patrons, and all its

patrons, as its primary duty. Neither white nor

colored patrons can he heard to complain of their

separation if their transportation is across a section

where fights and discord would occur by reason of

their intermingling for, after all, the principal duty

is to the great traveling public and that duty is safe

18

transportation, safe from discord; safe from bicker

ings, safe from fights and safe from fears that such

discord, bickering and strife will endanger the other

patrons.

The indisputable proof is that safe passage for

passengers at Wickliffe, Kentucky, requires their

separation and that requirement is upon this carrier

and placed upon it by the law of the land, written re

peatedly by its highest courts for nearly seventy-five

years. It is the appellee’s insistent plea that, since

it is charged with the responsibility of safely con

ducting its white and colored passengers in an area

such as Western Kentucky, that this Court protect

appellee against the individual suits of white or

colored passengers who may be unwilling, in their in

dividual cases, to a harmonious and orderly seating

arrangement as required of common carriers under

long-settled law, and that the judgment of the District

Court be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

D avis, B oehl, V iser & M arcus,

By George R. E ffinger,

1006 Citizens Savings Bank Building,

Paducah, Kentucky,

W aller, T hrelkeld & W hitlow ,

By T. S. W aller,

501-6 Citizens Savings Bank Building,

Paducah, Kentucky,

Attorneys for Appellee.

■

f"'•r

■Jvsv

V ‘ .

■

; ‘i ■

'y ' , ' J ' i r ‘ y\ ;

•

1^1;: .

- ,

. . . v l i ; , . a "

" ■" " y;:Vf

. • ■

: f - -

■

-■ * - . .:

- ■ v v.:'V . • , -•

' ' r ' . ‘ ' : - w " ; ^ ' ■

■ @

-

i

* »

V‘

■ Z ' t - ' - t

<\ . ■ 1..

■ ■ ....................

■

■

■■

s

, -

ySr-' •

I

i

; j

'

' ,1

4

: ' I

- • ■■ ■ - ■ .

• ■; ,xY* V;> :

*.<1, '

•V> • V '

■••:■ ■ ••

■: '■ V-:->*'■' -

- ■ i!<