Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Reply Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant

Public Court Documents

August 16, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Reply Brief for Plaintiff-Appellant, 1990. 92ad32a6-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8b7c2d49-3640-446a-bbd1-02ad4ba6a362/patterson-v-mclean-credit-union-reply-brief-for-plaintiff-appellant. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

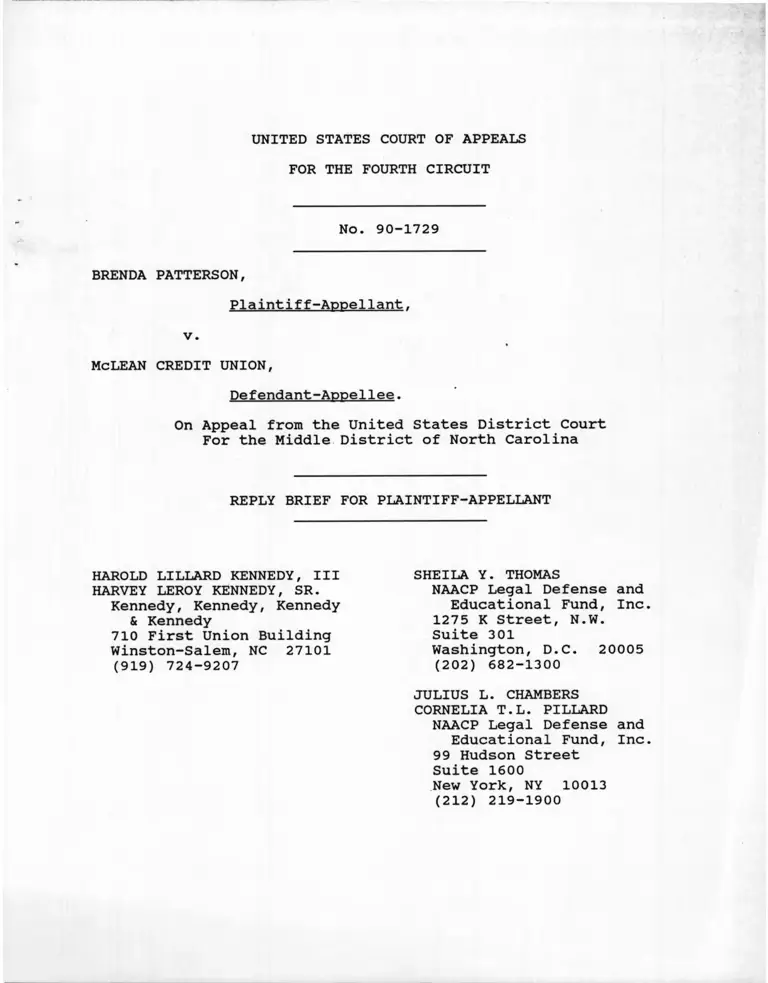

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 90-1729

BRENDA PATTERSON,

Plaintiff-Appellant.

v.

MCLEAN CREDIT UNION,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Middle District of North Carolina

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

HAROLD LILLARD KENNEDY, III

HARVEY LEROY KENNEDY, SR.

Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy

& Kennedy

710 First Union Building

Winston-Salem, NC 27101

(919) 724-9207

SHEILA Y. THOMAS

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ii

INTRODUCTION ...................................... 1

I. THE DISTRICT COURT'S SUA SPONTE

DISMISSAL OF MRS. PATTERSON'S

PROMOTION CLAIM IS REVERSIBLE ERROR ......... 2

II. THE DEFENDANT'S TEST ARBITRARILY

EXCLUDES PROMOTION CLAIMS THAT MEET

THE "NEW AND DISTINCT RELATION" TEST ....... 5

III. THE DISTRICT COURT'S DECISION MUST BE

VACATED BECAUSE IT DEPENDS ON FACTUAL

DETERMINATIONS THAT ONLY A JURY CAN MAKE ..... 9

IV. IF THE WAIVER DOCTRINE APPLIES IN THIS

CASE, IT DOES NOT PREVENT PLAINTIFF

FROM CONDUCTING FURTHER DISCOVERY, BUT

PRECLUDES MCLEAN FROM RAISING NOW FOR

THE FIRST TIME THE DEFENSE THAT

SECTION 1981 DOES NOT COVER MRS.

PATTERSON'S PROMOTION CLAIM ................. 13

V. THE QUESTION OF WHETHER THE DISTRICT

COURT HAD PENDENT JURISDICTION IS NOT

BEFORE THIS COURT ........................... 15

CONCLUSION 16

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Bennun v. Rutgers State University. 737 F. Supp. 1393

(D.N.J. 1990) 6

Chicaao-Midwest Meat Association v. City of Evanston. 589

F.2d 278 (7th Cir.), cert, denied. 442 U.S. 946 (1979),

affirmed . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Figures v. Board of Public Utilities. 731 F. Supp. 1479 (D.

Kan. 1990)................................................. 10

Griddine v. Dillard Department Stores. 51 FEP 306 (W.D. Mo.

1 9 8 9 ) ...................................................... - 1 0

Hudgens v. Harper-Grace Hospitals. 728 F. Supp. 1321

(E.D.Mich. 1990) ........................................ 6

Literature. Inc, v. Quinn. 482 F.2d 372 (1st Cir. 1973) . . 2

Luna v. City and County of Denver Department of Public

Works, et al.. 718 F. Supp. 854 (D. Colo. 1989) . . . 6

Malhotra v. Cotter & Co.. 885 F.2d 1305 (7th Cir. 1989) . . 6

Mallory v. Booth Refrigeration Supply Co.,

Inc. . 882 F. 2d at 910 (4th Cir. 1989)............................ 5

Miller v. Shawmut Bank of Boston. 726 F. Supp. 337 (D.Mass.

1 9 8 9 ) .............................................. 6, 10

Miller v. Svissre Holding Co., Inc.. 731 F. Supp. 129

(S.D.N.Y. 1990) ........................................ 6

Mobley v. Pigglv Wiggly. No. 687-66, slip op. (S.D. Ga.

Dec. 19, 1989) ........................................ 10

Norman v. McCotter. 765 F.2d 504 (5th Cir. 1985) . . . . 3

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 105 L. Ed. 2d 132 (1989) 2, 4,13, 14

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 729 F. Supp. 35 (M.D.N.C. •

1 9 9 0 ) 9

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 887 F.2d at 485 . . . . 4

Powell v. United States. 849 F.2d 1576 (5th Cir. 1988) . . 4

CASES PAGE

ii

CASES PAGE

Rivers v. Baltimore Department of Recreaion and Parks

51 FEP 1886 .......................................... 8

Square D Co. v. Niagara Frontier Tariff Bureau. Inc.. 760

F. 2d 1347 (2d Cir. 1 9 8 5 ) ................................ 2

Tinaler v. Marshall. 716 F.2d 1109 (6th Cir. 1983) . . . 2

United States Development Coro. v. People's Federal Savings

& Loan. 873 F.2d 731 (4th Cir. 1 9 8 9 ) ................ 2, 3,4

United States v. One Mercedez-Benz. 542 F.2d 912 (4th Cir.

1 9 7 6 ) ..................................................... 13

Utility Control Corp. v. Prince William Const'. . 558 F.2d 716

(4th Cir. 1 9 7 7 ) ............................................. 3

Washington v. Union Carbide. 870 F.2d 957 (4th Cir. 1989) . . 15

Webb v. Bladen. 480 F.2d 306 (4th Cir. 1 9 7 3 ) ................ 15

White v. Federal Express. 729 F. Supp. 1536 (E.D. Va. 1990) 7, 10

Williams v. Miracle Plywood Corp.. 1990 U.S. Dist.

Lexis 2502 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 8, 1990)......................... 10

Winborne v. Eastern Airlines. 632 F.2d 219 (2d Cir. 1980) . . 4

STATUTES

42 U.S.C. § 1 9 8 1 ........................................... Passim

Fed.R.Civ.P. 56(c) ...................................... 4

Fed.R.Civ.P. 56(f) . . . . . . . . . . . 13

iii •

• -..... - , • . , - - • -

INTRODUCTION

McLean contends that the district court's summary dismissal

of Mrs. Patterson's promotion-denial claim should be affirmed

because even full presentation and proper review of the evidence

on remand could not salvage plaintiff's claim. Plaintiff has,

however, pointed to evidence already in the record that warrants

a jury trial on whether the promotion she was denied would have

placed her in a "new and distinct relation" to McLean.

In order to support its position that no jury findings are

needed, McLean proposes a drastic narrowing of the "new and

distinct relation" standard which would be so categorical that

few findings of fact would be relevant: Defendant contends that

only denial of those promotions that would involve a change from

a non-supervisory to a supervisory job should be covered by

section 1981. Although the Supreme Court in this case could

readily have articulated such a standard if that is what it

intended, what the Court's opinion requires is merely that the

promotion involve an opportunity for a "new and distinct"

relation between employer and employee. Lower courts have held

that many kinds of distinctions — including but certainly not

limited to the distinction between non-supervisory and

supervisory work — may meet the Supreme Court's test. In this

Circuit, the crucial factors are whether the promotion would

involve a increase in pay and in responsibility.

The record here includes sufficient evidence of both factors

to preclude summary judgment, but because application of this

test depends on facts not relevant under prior law, discovery

•mtriy r w *■ iL ■' 5.--__

should be reopened and the record completed prior to trial.

Defendant contends that plaintiff has waived her right to

discovery, but if the waiver doctrine applies at all in this

case, it precludes McLean from arguing that Mrs. Patterson's

promotion claim is not actionable, because until now, as the

Supreme Court observed, McLean "has not argued at any stage that

[Mrs. Patterson's] promotion claim is not cognizable under §

1981." Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 105 L.Ed. 2d 132, 156

(1989) '.

I. THE DISTRICT COURT'S SUA SPONTE DISMISSAL OF MRS.

PATTERSON'S PROMOTION CLAIM IS REVERSIBLE ERROR

Defendant incorrectly asserts that the district court's

failure to notify plaintiff of its intention to dismiss her case

sua sponte and to give her an opportunity to oppose the dismissal

is harmless error. Deft. Br., at 24-25. In this and other

Circuits, a district court's sua sponte dismissal without notice

and an opportunity to respond is an independent ground for

reversal. See. e.g.. United States Dev. Corp. v. People's

Federal Sav. & Loan. 873 F.2d 731, 736 (4th Cir. 1989); Square D

Co. v. Niagara Frontier Tariff Bureau. Inc.. 760 F.2d 1347, 1365

(2d Cir. 1985); Tinqler v. Marshall. 716 F.2d 1109, 1112 (6th

Cir. 1983); Literature. Inc, v. Quinn. 482 F.2d 372, 374 (1st

Cir. 1973). This is true even if the court of appeals believes

that a full briefing and presentation of evidence in the district

court might not cause the dismissed claim to be revived.

Defendant contends that no amount of further discovery could

2

salvage plaintiff's promotion-denial claim. Deft. Br. at 27.1

This Court has held, however, that a requirement that additional

facts sufficient to defeat summary judgment be identified "misses

the point" of the per se rule against sua sponte dismissals in

the absence of the proper procedure. United States Dev. Corp..

873 F.2d at 736. "Appellants' right to notice and an opportunity

to be heard on its claim has nothing to do with the merits of its

case," id, and enforcement of that right here requires reversal.

Cases upon which defendant relies in support of its

"harmless error" exception to the rule against premature sua

sponte dismissals do not support its position. The Courts of

Appeal in Norman v. McCotter. 765 F.2d 504, 508 (5th Cir. 1985),

and Chicago-Midwest Meat Ass'n v. City of Evanston. 589 F.2d 278,

282 (7th Cir. 1978), cert, denied. 442 U.S. 946 (1979), affirmed

the district courts' failure to give notice of their sua sponte

decisions to convert motions to dismiss into motions for summary

judgment, not sua sponte decisions to enter judgment on claims

where no motion has been filed. Even in the context of

conversion of a motion to dismiss to a motion for summary

judgment, failure to give notice is reversible error in the

Fourth Circuit. See Utility Control Corp. v. Prince William

Const.. 558 F.2d 716, 719 (4th Cir. 1977). This rule is

consistent with "the majority of the Circuits that have

1As plaintiff has argued, the evidence already in the record

precludes entry of summary judgment, and additional discovery

relating to the distinctions between the two positions at issue

would further support the claim. See Pltf. Br., points II-IV.

3

considered the effect of noncompliance with the advance notice

provision of Rule 56(c)[, which] have held that such a procedural

defect vitiates the entry of summary judgment against the non

moving party.” Winborne v. Eastern Airlines. 632 F.2d 219, 223 &

n. 5 (2d Cir. 1980) (citing cases).2

Defendant also cites Powell v. United States. 849 F.2d 1576,

1580-82 (5th Cir. 1988), which, even if it were not directly

contrary to the law in this Circuit, see United States Dev.

Coro.. 873 F.2d 731, is inapposite here. The district court in

Powell gave notice of its intention to grant summary judgment,

but did not give the full 10 days' notice required by Rule 56(c),

and the plaintiffs responded that they had no additional evidence

to present. Here, in contrast, no notice whatsoever was given,

and plaintiff seeks to discover and introduce additional evidence

in support of her claim. See Pltf. Br., Point IV; infra, Point

IV.3

2 There is more reason to reaffirm the rule against sua

sponte dismissals in this case than in the context of converting

a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to a Rule 56 motion. In the conversion

context, motion papers referring to matters outside the pleadings

have been filed, which at least alerts a plaintiff to the

possibility that judgment will be entered, and to the defendant's

grounds.

In view of the fact that the Supreme Court contemplated

"further proceedings,” Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 105 L.

Ed. 2d at 158, and that the Fourth Circuit instructed that the

promotion-denial claim "should be considered an open one” on

remand, Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 887 F.2d at 485, it is

unclear why defendant believes the "law of the case" doctrine

obviates the requirement of notice and an opportunity to respond.

See Deft. Br. at 23-24. Mrs. Patterson does not dispute that the

district court is bound by the decisions of the Supreme Court and

the Court of Appeals. Those decisions did not, however, purport

4

II. THE DEFENDANT'S TEST ARBITRARILY EXCLUDES PROMOTION CLAIMS

THAT MEET THE "NEW AND DISTINCT RELATION” TEST

McLean erroneously contends that Mallory v. Booth

Refrigeration Supply Co.. Inc.. 882 F.2d 908 (4th Cir. 1989),

requires that a plaintiff's promotion-denial claim involve a

promotion from a non-managerial to a managerial position before

it is actionable under § 1981. Deft. Br., at 15. This Court

held in Mallory that an "increase in responsibility and pay

satisfies" the Supreme Court's "new and distinct relation"

standard. 882 F.2d at 910. There is nothing in the opinion to

support the defendant's assertion that the fact that the

plaintiffs in that case sought supervisory positions was

"critical" to this Court's determination that their promotion

claims were cognizable under § 1981. Deft. Br. at 13. Indeed,

the district court in this case did not even view supervisory

responsibilities as relevant to whether the promotion denial is

covered by § 1981.

Defendant asserts that denial of "a move from a non-

supervisory to a supervisory position" is required by the Supreme

Court's "new and distinct relation" standard. Deft. Br. at 15.

Although denial of such a promotion is generally cognizable, a

promotion-denial under § 1981 need not involve a lost opportunity

to decide whether plaintiff's promotion claim is actionable under

the standard the Supreme Court announced. Decisions in other

cases that do interpret and apply the "new and distinct relation"

standard indicate that plaintiff is entitled to proceed to

discovery and trial on her promotion claim. See Pltf. Br., Point

II; infra. Point II.

5

to become a supervisory employee. Discriminatory denial of a new

employment relationship that is genuinely "distinct" from the

former relationship in any number of ways violates § 1981. See.

Malhotra v. Cotter & Co.. 885 F.2d 1305, 1317 n.6 (7th Cir.

1989)(Cudahy, J., concurring); Hudgens v. Harper-Grace Hosps..

728 F. Supp. 1321 (E.D.Mich. 1990) (promotion from supervisory

position to technical position); Miller v. Swissre Holding Co..

Inc.. 731 F. Supp. 129 (S.D.N.Y. 1990) (promotion from production

coordinator to supervisor of production control); Miller v.

Shawmut Bank of Boston. 726 F. Supp. 337 (D.Mass. 1989)

(promotion from customer service representative to personal

banker); Luna v. City and County of Denver Department of Public

Works. et al.. 718 F.Supp. 854 (D. Colo. 1989) (promotion from

Project Inspector I to Engineer III); Bennun v. Rutgers State

University. 737 F. Supp. 1393 (D.N.J. 1990)(promotion from

associate professor to full professor).

Mrs. Patterson, undoubtedly, meets this standard. Pltf. Br.

at 21-24. The defendant concedes that Mrs. Patterson's job and

the promotion she sought "may have been different", Deft. Br. at

14, but argues that Mrs. Patterson's claim must fail because both

jobs were "clerical" positions. However, the record reflects

that the jobs were not similar in levels of responsibility or pay

and that Mrs. Williamson's promotion resulted in her obtaining

some of her supervisor's responsibilities.4 Pltf. Br. 21; 2 Tr.

4 McLean further argues that the "differential in pay is not

significant," Deft. Br. at 14, and misrepresents to the court

that Mrs. Patterson argues that a pay increase alone would meet

6

56 (2 JA 23-24). McLean cannot escape its obligation under the

Supreme Court's decision not to discriminate by sweeping a wide

range of jobs with significantly different responsibilities into

a catch-all "clerical" category. Application of the 1866 Act

does not depend on whether two jobs in 1990 be characterized as

clerical in the particular organizational structure of McLean

Credit Union.

Neither of the two opinions of district courts in this

Circuit upon which defendant relies support its argument that

Mrs. Patterson's promotion-denial claim must fail. Both cases

require an examination of job requirements, levels of

responsibility and pay and neither holds that only a promotion

from a non-managerial to a managerial position meets the Supreme

Court's standard.

The court in White v. Federal Express. 729 F.Supp. 1536,

1546 (E.D. Va. 1990), held that significant changes in

responsibilities and pay must be shown to meet the "new and

distinct relation" standard. The court concluded that Mr.

White's job as a courier and the dispatcher position that he

the Mallorv standard, Deft. Br. at 13. The defendant is mistaken

on both accounts. First, the relevant differential is between

the pay Mrs. Patterson would have received if she had been in

Mrs. Williamson's position and what her pay was at the time

Williamson was promoted, and not, as defendant contends, between

Mrs. Williamson's salary as an accountant intermediate and an

accountant junior. Second, Mrs. Patterson does not argue that an

increase in salary alone is sufficient to meet the "new and

distinct relation" test, but instead, asserts that under Mallorv

a pay increase should be considered in relation to other relevant

factors in a court's inquiry into the difference between a

plaintiff's job and the promotion she seeks..

7

sought had "essentially the same" levels of responsibility and no

significant difference in pay, but noted that Mr. White "state[d]

a substantial, but not sufficient, case for meeting the contract

test."

Similarly, the court in Rivers v. Baltimore Department of

Recreation and Parks, et al.. 51 FEP 1886, 1896 (D.Md 1990),

dismissed the plaintiff's promotion-denial claims because

although it was a "close call", the promotion would have resulted

in "little change in responsibilities, duties, or authority...."

Mrs. Patterson's claim meets the standard in White and Rivers,

since there was a substantial difference in the levels of

responsibility between file coordinator and accountant

intermediate — a difference which McLean repeatedly stressed at

trial in its effort to show that Mrs. Patterson was not qualified

for the intermediate accountant job — and a significant increase

in pay of almost two dollars per hour.

Neither this Court nor the district courts in this circuit

have adopted the narrow interpretation of the "new and distinct

relation" test that the defendant espouses. McLean's proposed

test would arbitrarily exclude from § 1981's coverage many

promotion claims that meet the "new and distinct relation"

requirement. Whether a promotion is actionable properly depends

on a wide range of factors showing the degree of difference

between the plaintiff's former job and the job into which she

seeks to be promoted, and does not require that the promotion

8

result in the elevation from a non-supervisory to supervisory

role.

III. THE DISTRICT COURT'S DECISION MUST BE VACATED BECAUSE IT

DEPENDS ON FACTUAL DETERMINATIONS THAT ONLY A JURY CAN MAKE

Defendant concedes that the district court was not empowered

to make factual determinations; rather it is merely "as a

threshold inquiry [that] the court determines as a matter of law

whether there is sufficient evidence to create a material issue

of fact for the jury." Deft. Br. at 21. But making factual

findings is precisely what the district court did when it

determined that Mrs. Patterson's and Mrs. Williamson's

compensation, the locations and offices in which they worked, and

their working conditions were not sufficiently distinct that a

promotion into Mrs. Williamson's job would have placed Mrs.

Patterson in a "new and distinct relation" with McLean.

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 729 F. Supp. 35, 36 (M.D.N.C.

1990).5 Under the summary judgment standard, defendant

acknowledges, the court must view the evidence "in the light most

favorable to plaintiff." Deft. Br. at 19. Because the district

court failed to do so here, but instead resolved factual

Defendant contends that working conditions "relate to

post-formation conduct and are no longer actionable under Section

1981." Deft. Br. at 27. Plaintiff is not seeking to challenge

Brenda Patterson's working conditions. Rather, she is entitled

to discover and introduce evidence relating to the relative

working conditions of her job and the intermediate accountant job

because the district court viewed working conditions as one

factor relevant to the determination whether the promotion would

have created a "new and distinct relation" between Brenda

Patterson and McLean. See. Patterson. 729 F. Supp. at 36.

9

conflicts and drew inferences in favor of defendant, see, id..

Pltf. Br. at 25-28, 12 (citing to material record evidence

supportive of plaintiff's claim but disregarded by the district

court), its decision must be vacated.

McLean contends that the district court made no factual

findings because "whether a promotion claim is actionable is a

legal standard rather than a question of fact." Deft. Br. at 21.

Defendant does not argue that there are no factual disputes

relating to the factors that the district court identified as

legally relevant. Instead, defendant simply makes the untenable

assertion that only legal determinations were required.

Plaintiff agrees that it is for the judge to construe the legal

standard, but where the facts to which the standard applies are

disputed, the disputes must be resolved by a jury before the

ultimate issue of liability on the promotion claim can be

resolved.6

6 The cases upon which defendant relies do not support

its contention that application of the Supreme Court's section

1981 promotion standard is a purely legal matter. The courts in

Rivers v. Baltimore Dept, of Recreation. 51 FEP Cases 1886 (D.

Md. 1990), and Williams v. Miracle Plywood Corp.. 1990 U.S. Dist.

Lexis 2502 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 8, 1990), reviewed the allegations of

the complaints in light of motions to dismiss — a function that

is always the exclusive province of the judge. The court in

White v. Federal Express Corp.. 729 F. Supp. 1536, 1541 (E.D. Va.

1990), did not rule that facts are irrelevant, but merely that

the facts material to the plaintiff's promotion-denial claim were

not in dispute, and that judgment as a matter of law was

therefore appropriate.

Several courts have specifically emphasized that the

promotion-denial inquiry is fact-intensive, Mobley v. Piggly

Wiggly. No. 687-66, slip op. at 8-9 (S.D.Ga. Dec. 19, 1989),

Luna. 718 F. Supp. at 857, that further discovery is appropriate

in light of the Supreme Court's decision in this case, Griddine

10

In proposing alternative bases on appeal for affirming the

decision of the district court, defendant repeatedly relies on

additional factual assertions beyond those facts "found" by the

district court. The dismissal of plaintiff's promotion claim

cannot be affirmed on the basis of defendant's assertions

relating to factual issues that the district court did not even

purport to address, and which remain in dispute. Affirmance on

such grounds would only compound the problem of lack of notice to

plaintiff, see Point I, supra. and would commit the same error

the district court made in usurping the jury's factfinding role.

In an effort to compensate for the district court's utter

failure to examine the important question whether the promotion

Brenda Patterson sought would have changed her responsibilities,

defendant makes the factual assertion that Mrs. Patterson's level

of responsibility would have remained the same had she been

promoted from file coordinator to accountant intermediate. Deft.

Br. at 12. The job descriptions in the record show, however,

that if Mrs. Patterson had received this promotion, she would

have had increased responsibilities. Deft. Ex. 14, 15 (SA 26,

27). This evidence alone precludes this Court from crediting

defendant's assertion that the promotion Mrs. Patterson sought

"is properly characterized as a lateral transfer ...." Deft. Br.

v. Dillard Department stores. 51 fep cases 306 (W.D.Mo. 1989),

and that summary judgment must be denied where facts material to

the distinction between a plaintiff's job and the position she

sought remain in dispute, Figures v. Board of Public Utilities.

731 F. Supp. 1479, 1482 (D. Kan. 1990); Miller v. Shawmut Bank of

Boston. 726 F. Supp. at 342.

11

at 14.

Defendant makes the additional factual assertion that there

was no opening for the job into which Mrs. Patterson sought to be

promoted. Deft. Br. at 6-8. To support this contention,

defendant also makes the factual assertion that Susan Williamson

performed the identical job functions before and after her

promotion from junior accountant to intermediate accountant, and

that the promotion was therefore really just a "title change" for

Mrs. Williamson. Deft. Br. at 1. There is testimony in the

record, however, that Mrs. Williamson received additional

training for the intermediate accountant position (2 JA 81, 3 JA

48), that her duties changed (2 JA 24), and that Mrs. Williamson

herself considered the change a promotion (2 JA 22). A jury

could reasonably infer from this evidence that Mrs. Williamson's

new job involved different skills and responsibilities from her

former one. A jury could further infer that where a new job is

available within an organization, it creates an opening available

to other qualified employees, including Mrs. Patterson.

The question whether a job opening existed, unlike the

issues raised by the "new and distinct relation" standard, was

not created by the Supreme Court's decision in this case, but was

specifically addressed by McLean's motion for a directed verdict

during the first trial.7 The district court denied the directed

Defendant argued then, as it does again here on appeal,

that "[i]t wasn't a job vacancy. [Mrs. Williamson] was doing the

same thing before the promotion that she was doing after. She

got a raise, she got a change in title, but there was no vacancy

created by her position." 3 Tr. 48 (SA 19).

12

verdict motion and permitted the promotion-denial claim to go to

the jury, 3 Tr. 76 (3 JA 47), presumably because there was enough

evidence of a job opening to create a genuine factual issue.

Because the jury rendered a general verdict on the promotion

claim, it is not possible to determine whether it credited

defendant's position that there was no job opening, or whether it

rendered a verdict for defendant on some other ground. The

Supreme Court thus properly identified this as an open issue to

be determined on remand. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 105

L. Ed. 2d at 157 n. 7.

IV. IF THE WAIVER DOCTRINE APPLIES IN THIS CASE, IT DOES NOT

PREVENT PLAINTIFF FROM CONDUCTING FURTHER DISCOVERY, BUT

PRECLUDES MCLEAN FROM RAISING NOW FOR THE FIRST TIME THE

DEFENSE THAT SECTION 1981 DOES NOT COVER MRS. PATTERSON'S

PROMOTION CLAIM

Defendant contends that Mrs. Patterson is not entitled to

further discovery because she did not seek to reopen discovery in

the district court. Under exceptional circumstances, however, an

appellate court is entitled to consider an issue not raised

below. United States v. One Mercedez-Benz. 542 F.2d 912, 915

(4th Cir. 1976). The district court's precipitous dismissal of

the case in the absence of a motion by McLean for summary

judgment denied plaintiff notice that the court was preparing to

review the evidence in the record, and deprived her of an

opportunity to file an affidavit pursuant to Federal Rule of

Civil Procedure 56(f) requesting an opportunity to conduct

further discovery. Under these circumstances, the case should be

13

remanded for further discovery, properly briefed motions for

summary judgment, and a trial if necessary.

If this Court views the promotion-denial standard announced

by the Supreme Court as insufficiently changed to warrant new

discovery beyond that which plaintiff conducted prior to the

original trial in this case, then it should by the same token

determine that defendant has waived its defense that section 1981

does not apply to Mrs. Patterson's promotion-denial claim.

McLean's current Brief on appeal raises for the first time in the

six years that this case has been litigated the defense that Mrs.

Patterson's promotion-denial claim is not cognizable under

section 1981. Indeed, defendant has consistently contended that

promotion claims are actionable under the statute, and that Mrs.

Patterson's promotion claim should fail for other reasons.

Because McLean did not argue in the trial court, on appeal, or in

the Supreme Court that section 1981 does not cover all or some

claims of discriminatory promotion-denial, the Supreme Court

viewed this defense as waived. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

105 L. Ed. 2d at 156 (commenting that "[b]ecause respondent has

not argued at any stage that petitioner's promotion claim is not

cognizable under § 1981, we need not address the issue further

here"). The district court thus acted improperly in disposing of

plaintiff's promotion claim on this ground.

14

V. THE QUESTION OF WHETHER THE DISTRICT COURT HAD PENDENT

JURISDICTION IS NOT BEFORE THIS COURT

McLean argues that the Court lacks jurisdiction to hear Mrs.

Patterson's claim of intentional infliction of emotional distress

because it dismissed her § 1981 claim, but it is well established

that a federal court may exercise its discretion and decide a

pendent state claim even after a federal claim has been

dismissed. Washington v. Union Carbide. 870 F.2d 957 (4th Cir.

1989); Webb v. Bladen. 480 F.2d 306 (4th Cir. 1973). (Deft. Br.

34-35). Nothing in the district court's opinion indicates that

the court concluded it lacked jurisdiction to decide the pendent

state claim. Consequently, the defendant has no basis for its

assertion.8

8 However, if this Court were to affirm the dismissal of

plaintiff's federal claim and determine that it shall not

exercise its discretion to retain jurisdiction over the state

claim, the plaintiff requests that this Court dismiss her state

claim without prejudice and grant her leave to file suit in the

North Carolina Courts. See. Webb v. Bladen, supra at 309.

15

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision below should be

vacated and the case be remanded to the district court for

further discovery and a trial on the merits

HAROLD LILLARD KENNEDY, III

HARVEY LEROY KENNEDY, SR.

Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy

& Kennedy

710 First Union Building

Winston-Salem, NC 27101

(919) 724-9207

THOMAS 1/

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

August 16, 1990

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This will certify that I have this date served counsel

for defendant in this action with true and correct copies of the

foregoing Reply Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant by placing said copies

in the U.S. Mail at New York, New York, First-Class postage thereon

fully prepaid addressed as follows:

George Doughton, Jr., Esq.

H. Lee Davis, Jr., Esq.

Thomas J. Doughton, Esq.

114 W. Third Street

Winston-Salem, NC 27101

Executed this 16th day of August, 1990 at New York, New

York.

1

_ _ _ . v w ’

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE ',7

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

STATESBORO DIVISION p-r ! ' J -7 '1 - . C w

HENRY MOBLEY,

CIVIL ACTION

CV687-66

Defendants *

O R D E R

Before the Court are defendants' self-styled "motion

to dismiss and/or motion for summary judgment" on plaintiff's

claims brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. section 1981 and

defendants' motion to strike plaintiff's supplemental response

to the motion to dismiss. The Court allowed defendants to

file their out of time motion because of the Supreme Court's

recent holding in Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, ___ U.S.

_, 109 S.Ct. 2363 (1989). Defendants contend that

plaintiff's section 1981 claim is roreclosed by the Patterson

decision, which clarified and restricted the applicability of

section 1981 to claims of racial discrimination. Plaintiff

counters that his section 1981 claim is not foreclosed by

Patterson, and that in any event Patterson should not be

applied retroactively to the instant case. I will first rule

on the motion to strike.

Plaintiff

vs .

★

★

PIGGLY WIGGLY SOUTHERN, INC,

and STEVE STANLEY COOPER, *

•k

• ■ • ' \ :

<0 7 2 A •!>

Rrv 0/TT2)

Plaintiff was hired as a meat clerk in defendant Piggly

Wiggly's Sylvania, Georgia store in May, 1976. The following

year plaintiff became a meat cutter, and in early 1983

plaintiff became the cutting.room manager in the store s meat

department. In December, 1985 defendant Cooper became the

meat department manager, thereby becoming plaintiff's

supervisor. Plaintiff alleges that defendant Cooper promised

plaintiff that he would be promoted to assistant manager of

the meat department, but that instead a white male was brought

in to be the assistant manager in April, 1986, resulting in

plaintiff's constructive discharge. Plaintiff subsequently

brought suit pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1981, claiming that he

was denied a promotion and constructively discharged because

of his race. Defendants are moving to dismiss and/or for

summary judgment as to plaintiff's section 1981 claims.

Defendants contend that the Supreme Court's decision in

Patterson holds that plaintiff's claim that he was

constructively discharged because of his race is no longer

actionable under section 1981, and that defendants are

entitled to summary judgment on plaintiff's section 1981

claim that he was denied a promotion because of his race.

Plaintiff contends that Patterson does not require that the

Court either dismiss or grant summary judgment as to

plaintiff's section 1981 claims, and that in any event

Patterson should not be applied retroactively.

The motion to dismiss and/or for summary judgment

2

presents two issues. First, whether Patterson should be given

retroactive effect so as to apply to the instant case, and

second, whether the holding in Patterson requires the Court

to either dismiss or grant summary judgment as to either of

plaintiff's section 1981 claims. I will first decide whether

Patterson should be applied to the instant case. However,

before reaching the merits of this issue I must resolve

defendants' motion to strike.

Defendants contend that I should not reach the issue of

whether Patterson should be applied retroactively because

plaintiff raised the issue in a supplemental response which

was not timely filed. Thus, they argue, the supplemental

response should be stricken and the issues raised therein not

reached. However, I believe that such issues should be

decided on the merits rather than on the basis advocated by

defendants, particularly where the case law on the issue

presented is just now being developed. In any event, my

decision on this issue makes defendants' argument moot.

In support of his argument that Patterson should not

apply retroactively to the case at bar plaintiff cites an

unpublished opinion from the district court of Kansas, Thomas

v. Beech Aircraft Corporation, No. 78-4338 (D. Kan. Sept, -u,

1989). In Thomas the Court, applying Chevron— OjJL— Co^— v^

Huson. 404 U.S. 97 (1971), concluded that Patterson should

not be applied retroactively because the complaint had been

filed in 1978, over ten years before the Patterson decision

had been rendered, and therefore it would be inequitable to

apply Patterson retroactively.

Conversely, the complaint in the instant case was filed

in June, 1987. While plaintiff may protest that two years is

a long time to wait for his case to be tried, it is certainly

not an unreasonable length of time. This court currently has

well over 300 cases on its active docket.1 2 Moreover, many of

these cases are criminal cases, which must take priority over

civil matters. Thus, it would not be inequitable to apply

Patterson to the instant case, and I can find no cause to

depart from the general rule that decisions rendered while a

case is pending must be applied to the pending case.

Having concluded that Patterson applies to the case at

bar, I must now decide whether that decision mandates that

"defendants' motion to dismiss and/or for summary judgment on

plaintiff's section 1981 claims be granted. In Patterson the

plaintiff alleged that defendant harassed, failed to promote,

and discharged her on account of her race. The Court held

that only conduct related to "the formation of a contract, but

not to problems that may arise later from the conditions of

continuing employment," was actionable under section 1981.

1 Additionally, the recuperative period required by the

presiding judge following his accident in May, 1989 nas no

doubt contributed significantly to the current backlog of

cases on the Court's docket.

2 In this regard I note that the vast majority of courts

which have considered this issue have reached the same

conclusion. See, e.g., Prather v. Dayton Power & Light Co_̂ ,

No. C-3-85-491 (S.D. Ohio Sept. 7 , 1989 ).

4

AO 72A O

|R « v . 8 /8 2 )

* : •/' ~ cr.T**r - '~\'7 r*'." jr vr-.j-v-*,. .V • • • ' :i • . r V - •______ ___________

The CourtPatterson, ___ U.S. ___/ 109 S.Ct. at 2372.

expressly stated that "the right to make contracts does not

extend...to conduct by the employer after the contract

relation has been established, including breach of the terms

of the contract or imposition of discriminatory working

conditions." Id- at 2373.

In applying these principles to plaintiff's discharge

claim it is apparent that plaintiff's discharge claim is not

actionable under section 1981 because such an action is, at

worst, a post-formation "breach of the terms of the

contract." Id. Plaintiff argues that his constructive

discharge was actually the result of defendant's failure to

enter into a contract on racially neutral terms at the time

of plaintiff's hire. However, no such allegation is in the

complaint. Furthermore, no evidence has been submitted to

substantiate such a claim. Accordingly, plaintiff s

discharge, even if it resulted from a discriminatory motive,

cannot form the basis for a cause of action under section

1981.

Plaintiff also argues that his constructive discharge

"resulted" from the defendants' failure to enter into a

contract because of plaintiff's race, i.e., defendants

failure to promote plaintiff. Employing the jargon of

Patterson, plaintiff contends that defendants' failure to

enter into a contract with plaintiff on account of his race

caused plaintiff to breach his contract with defendant Piggly

5

A O 77A D

(R * v . 8 /87 )

Wiggly. However, under Patterson the breach is not actionable

in a section 1981 suit, even if caused by a failure to enter

into a contract with plaintiff on account of his race. Any

conduct relating to the original "contract" between plaintiff

and defendant, even a refusal to enter into a new contract,

would necessarily constitute post-formation conduct as to the

original contract. Post-formation conduct is not actionable

under section 1981, and plaintiff therefore cannot maintain

an action under section 1981 for his allegedly discriminatory

constructive discharge.

Although plaintiff's discharge claim is not actionable

under section 1981, defendants are not entitled to summary

judgment on plaintiff's claim that he was denied a promotion

in violation of section 1981. Summary judgment should be

granted only if "there is no genuine issue as to any material

fact and the moving party is entitled to a judgment as a

matter of law." Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(c). The party moving for

summary judgment bears the burden of showing that there is no

genuine dispute as to any material fact in the case. Adickes

v. S.H. Kress & Co-. 398 U.S. 144, 157 (1970 ); Clemons v ..

Dougherty County, Ga., 684 F.2d 135c, 1368 (11th Cir. 1982).

The party moving for summary judgment may meet this burden by

showing that the nonmovant has failed to make a showing

sufficient to establish the existence of an element essential

to the nonmovant's case, and on which the nonmovant will bear

the burden of proof at trial. Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477

6

A O 7 2 A 'D {Rrv. 8/B2)

U .S. 317 ( 1986) . If there is any factual issue in the record

that is unresolved by the motion for summary judgment, then

the Court may not decide that matter. See Environmental

Dpfense Fund v. Marsh, 651 F,2d 983, 991 (5th Cir. 1981). All

reasonable doubts must be resolved in favor of the party

opposing summary judgment. Casey— Enterprises— v_.— American

Hardware Mutual Insurance Co;_, 655 F.2d 598, 602 (5th Cir.

1981). When, however, the moving party's motion for summary

judgment has pierced the pleadings of the opposing party, the

burden then shifts to the opposing party to show that a

genuine issue of material fact exists. Anderson v. Liberty

Lobby. Inc., 477 U.S. 242 ( 1985). This burden cannot be

carried by reliance on the pleadings, or by repetition of the

conclusory allegations contained in the complaint. Mgrri_§__v_j_

Ross. 653 F . 2d 1032, 1033 ( 11th Cir. 1981). Rather, the

opposing party must respond by affidavits or as otherwise

provided in Fed. R. Civ. P. 56.

The file indicates that the clerk notified the nonmovant

of the consequences for failure to respond to the motion for

summary judgment. Griffith v. Wainwriqht, 722 F.2d 822 (11th

Cir. 1985) . The nonmovant having had a reasonable opportunity

to respond to the motion, I will now rule on movant's motion

for summary judgment.

In Patterson the Supreme Court held that an employee s

claim that she had been denied a promotion on account of her

race was actionable under section 1981 if the "nature of the

A O 7 2 A O IRn. 8/82)

1 O'' '. '■

change in position was such that it involved the opportunity

to enter into a new contract with the employer." id at — ,

109 S.Ct. at 2377. The promotion involves " the opportunity

to enter into a new contract with the employer" only if the

"promotion rises to the level of an opportunity for a new and

distinct relation between the employee and the employer...."

Id.

Defendants argue that the promotion involved in the

instant case, a promotion from cutting room manager to

assistant manager of the meat department, did not involve a

new and distinct relation between defendant Piggly Wiggly and

plaintiff. Defendants claim that because plaintiff was

"acting assistant market manager" and performing all the

duties of an assistant manager, a promotion to assistant

market manager would not constitute a new and distinct

relation between plaintiff and defendant Piggly Wiggly.

However, an "acting" or interim assistant manager, who

occupies another position but is temporarily filling the

position of assistant manager, can certainly not be said to

occupy the same relation with the employer as would a

permanent assistant manager who may be subject to demotion to

his old position when a permanent assistant manager is hired.

Whether this different relation would constitute a new and

distinct relation" is a question of fact.

Furthermore, plaintiff testified that during this interim

period he did not receive the pay of an assistant manager.

8

V ■; • . • ' r,T-r '

A O 73A ‘T>

(R * v . 8 /8 3 )

See Mobley deposition at 81. Under these circumstances, to

determine whether plaintiff's promotion would constitute a

"new and distinct relation” between plaintiff and defendant

Piggly Wiggly would require that I make a factual

determination as to the respective jobs. See Mallory v. Booth

In ruling on a motion for summary judgment a court may not

make such factual determinations.

Based on the foregoing, defendants' motion to dismiss

plaintiff's section 1981 discharge claim is GRANTED.

Defendants' motion for summary judgment as to plaintiff's

section 1981 promotion claim is DENIED. Lastly, defendants'

motion to strike is DENIED as moot.

Refrigeration Supply Co., Inc^, 882 F.2d 908 (4th Cir. 1989).

ORDER ENTERED at Augusta,

December, 1989.

9