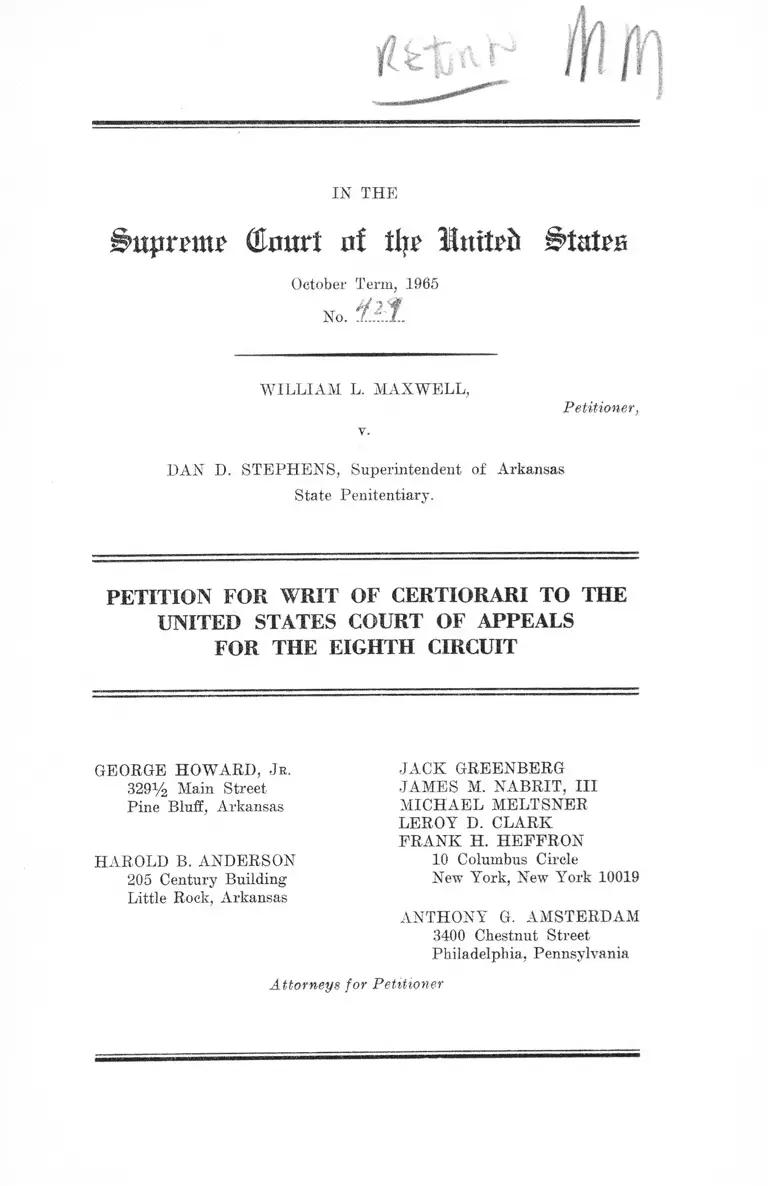

Maxwell v. Stephens Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maxwell v. Stephens Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, 1965. 15eede50-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8b9d755a-69fa-4c74-a5cc-fcb6a765fa2f/maxwell-v-stephens-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-eighth-circuit. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

£>tfpmn£ (tart of % States

October Term, 1965

No. t f j. l . .

WILLIAM L. MAXWELL,

Petitioner,

DAN D. STEPHENS, Superintendent of Arkansas

State Penitentiary.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

GEORGE HOWARD, Jr,

329% Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

HAROLD B. ANDERSON

205 Century Building

Little Rock, Arkansas

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

MICHAEL MELTSNER

LEROY D. CLARK

FRANK H. HEFFRON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

3400 Chestnut Street

Phi la delpli ia, Pennsylvania

Attorneys {or Petitioner

I N D E X

Opinions B elow .............................. -.................................... 1

Jurisdiction ..................... ................................................... 2

Questions Presented ......................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 4

Statement ......- ................................................ -................... 7

Search and Seizure...................................................... 8

Capital Punishment for Rape .......................... ....... 13

Selection of Jury Panels .................-........................ 17

Jurisdiction of the District Court .......................... 18

Reasons for Granting the W r it .................... ................. 18

I. Certiorari should be granted to determine the

legality of search of petitioner’s home without a

warrant, in petitioner’s absence, under purported

consent of his mother ............................................. 18

A. The search and seizure issues are important,

requiring consideration by this Court on certi

orari .................................. -.................................... 22

B. The decision below is wrong and sends peti

tioner to death in violation of his Fourth-

Fourteenth Amendment rights ............................. 29

II. Certiorari should be granted to determine

whether Arkansas’ death penalty for rape is un

constitutional because (A) an unrebutted prima

PAGE

facie showing has been made of its racial applica

tion, in violation of the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment, or (B) its allowance

to the jury of unfettered discretion to impose

capital punishment for all offenses of rape, in

the absence of aggravating circumstances, permits

cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments ..................... 33

A. Petitioner’s Equal Protection contention,

wrongly rejected below presents an impor

tant question for consideration by this Court

on certiorari ..................... ........ .......... ................ 33

B. The Court should grant certiorari to consider

petitioner’s contention that his sentence is un

constitutional under the Eighth and Fourteenth

Amendments ........ ......... ........... ............................ 44

III. Certiorari should be granted to determine

whether use of poll tax books containing racial

designations, as required by statute, in the system

of jury selection is constitutional ...................... . 46

Conclusion __ _____ ______ ______ _________________ _ 51

Table op Cases

Aaron v. Holman, U.S. Dist. Ct., M.D. Ala., C.A.

No. 2170-N ................ ..................... ............ ..... ........ ...... 36

Abel v. United States, 362 U.S. 217 (1960) .................. 21

Alabama v. Billingsley, Cir. Ct. Etowah County,

No. 1159 . ............. .................... ...................... ............... 36

Allison v. State, 204 Ark. 609, 164 S.W.2d 442 (1942) 44

Amos v. United States, 255 U.S. 313 (1921) ...........25, 29, 31

11

PAGE

Ill

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964) .....-............ 37,48

Arnold v. North Carolina, 376 U.S. 733 (1964) ........... 39

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953) .......................... 48

PAGE

Bailey v. Henslee, 287 F.2d 936 (8th Cir. 1961), cert.

denied, 368 U.S. 877 ...................-.................................. 39

Boyd v. United States, 116 U.S. 616 (1886) ................... 32

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (19o4) .... 31

Burge v. United States, 332 F.2d 171 (8th Cir. 1964),

cert, denied, 379 U.S. 938 ....... ......... -........................ 24, 25

Burge v. United States, 342 F.2d 408 (9th Cir. 1965) 28

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U.S. 110 (1882) ..................... —- 33

Calhoun v. United States, 172 F.2d 457 (5th Cir.

1949) ........ .................... -.......... -................................. .....27,28

Carroll v. United States, 267 U.S. 132 (1925) ........... 21, 28

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950) ........................ ----- 46

Channel v. United States, 285 F.2d 217 (9th Cir. 1960) 24

Chapman v. United States, 365 U.S. 610 (1961) .......21, 29

Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274 U.S. 445 (1927) ............. 43

Cobb v. Balkcom, 339 F.2d 95 (5th Cir. 1964) ............... 50

Cofer v. United States, 37 F.2d 677 (5th Cir. 1930) .... 27

Commonwealth v. Wright, 411 Pa. 81, 190 A.2d 0̂9

(1963) ________ ____ ___-................................................22> 26

Communist Party v. Subversive Activities Control

Board, 367 U.S. 1 (1961) .............................................. 39

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U.S. 385

(1926) ........................................-....... -.............................- 43

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965) .................-.......... 43

Craig v. Florida, Sup. Ct. Fla., No. 34,101 ...........—.... 3®

Cutting v. United States, 169 F.2d 951 (9th Cir. 1948) 28

Davis v. United States,

1964) ____ ____________

327 F.2d 301 (9th Cir.

................................. 23, 26, 28, 29

IV

Davis v. United States, 328 U.S. 582 (1946) ................... 26

Doxnbrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965) .............. .... 43

Driskill v. United States, 281 Fed. 146 (9th Cir. 1922) 28

Elmore v. Commonwealth, 282 Ky. 443, 138 S.W.2d 956

(1940) ............ ......... ......... ...... ........................................ 31

Entick v. Carrington, 19 How. St. Tr. 1029 (C.P. 1765) 32

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 (1964) ..................... 32

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958) ............... 40

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963) .................................. 50

Fisher v. United States, 324 F.2d 775 (8th Cir. 1963),

cert, denied 377 U.S. 999 ________ _______ ____ ____ _ 28

Foster v. United States, 281 F.2d 310 (8th Cir. 1960) 27

Fowler v. Rhode Island, 345 U.S. 67 (1953) .......... 37

Frank v. Maryland, 359 U.S. 360 (1959) ....................... 32

Fredricksen v. United States, 266 F.2d 463 (D.C. Cir.

1959) ......................... ....................................................... 28

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51 (1965) ................... 43

Frye v. United States, 315 F.2d 491 (9th Cir. 1963),

cert, denied, 375 U.S. 849 ..................... ........................ 22

Gatlin v. United States, 326 F.2d 666 (D.C. Cir. 1963) 22

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ................. 40

Gouled v. United States, 255 U.S. 298 (1921) ........... .... 25

Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U.S. 650 (1964) ___ ____ 37

Hamm v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 230 F.

Supp. 156 (E.D. Va. 1964) aff’d sub nom. Taneil v.

Woolls, 379 U.S. 19 ...................... ................................46, 47

Hart v. United States, 316 F.2d 916 (5th Cir. 1963) .... 24

Henslee v. Stewart, 311 F.2d 691 (8th Cir. 1963),

cert, denied, 373 U.S. 902 ............................................ 39

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954) ...................38,40

PAGE

V

PAGE

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242 (1937) ....................... 42

Hester v. United States, 265 U.S. 57 (1924) ....... ....... 21

Higgins v. United States, 209 F.2d 819 (D.C. Cir.

1954) .......... ....................................................................... 24

Holt v. State, 17 Wis.2d 468, 117 N.W.2d 626 (1962) 22

Holzhey v. United States, 223 F,2d 823 (5th Cir. 1955) 28

Johnson v. United States, 333 U.S. 10 (1948) —21, 25, 30

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938) .................- 30, 50

Jones v. United States, 357 U.S. 493 (1958) ................... 21

Joseph Bnrstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U.S. 495 (1952) .... 43

Judd v. United States, 190 F.2d 649 (D.C. Cir. 1951) .... 24

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267 (1963) ................. 42

Louisiana ex rel. Scott v. Hanchey, 20th Jud. Dist. Ct.,

Parish of West Feliciana .............................................. 36

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (196o) ........... 43

Lustig v. United States, 338 U.S. 74 (1949) ............. 29

McDonald v. United States, 307 F.2d 272 (10th Cir.

1962) ........ . ..- ........ ..................... -.................................... 25

McDonald v. United States, 335 U.S. 451 (1948) ........... 27

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) ............. 40

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961) ........................... 23,32

Martinez v. United States, 333 F.2d 405 (9th Cir.

1964) ............ ......... -............ - ............... ........ - .............. 23, 24

Mitchell v. Stephens, 232 F. Supp. 497 (E.D. Ark.

1964) ..............- ...........-----...........-.... - ......................... - 36

Moorer v. MacDougall, U.S. Dist. Ct., E.D.S.C., No.

AC-1583 ........................................... -....... ......... ............. 36

Mosco v. United States, 301 F.2d 180 (9th Cir. 1962),

cert, denied, 371 U.S. 842 ........................... -............. 22

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 (1958) 37

VI

N.A.A.C.P. V. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) ................... 43

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370 (1881) — ..... ............... 38

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 (1951) .................. 37

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) ...................... 40

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948) .................. 40

Pekar v. United States, 315 F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1963) 24

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 (1963) .. 42

Preston v. United States, 376 U.S. 364 (1964) .............. 21

Ralph v. Pepersack, 335 F.2d 141 (4th Cir. 1964) 44

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 (1955) ............................ 40

Reed v. Rhay, 323 F.2d 498 (9th Cir. 1963), cert,

denied, 377 U.S. 917 ......................... ............... ............ 24

Rees v. Peyton, 341 F.2d 859 (4th Cir. 1965) ........... 26, 28

Reszutek v. United States, 147 F.2d 142 (2d Cir. 1945) 28

Rios v. United Stales, 364 U.S. 253 (1960) ...............21, 23

Roberts v. United States, 332 F.2d 892 (8th Cir.

1964) ......................................................................... 27, 28, 29

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153 (1964) ..................... 42

Robinson v. United States, 325 F.2d 880 (5th Cir. 1964) 22

Romero v. United States, 318 F.2d 530 (5th Cir. 1963),

cert, denied, 375 U.S. 946 .............................................. 28

Rorie v. State, 215 Ark. 282, 220 S.W. 2d 421 (1949) 44

Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U.S. 889 (1963) ............. 13,44,45

Sartain v. United States, 303 F.2d 859 (9th Cir. 1962),

cert, denied, 371 U.S. 894 .......................................... 28

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) .......................... 37

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942) .................. 45

Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U.S. 553 (1931) .................... .......... 43

State v. Hanna, 150 Conn. 457, 191 A.2d 124 (1963) .... 22

State v. Scrotsky, 39 N.J. 410, 189 A.2d 23 (1963) ..... 22

Stein v. United States, 166 F.2d 851 (9th Cir. 1948) .... 29

PAGE

PAGE

Stoner v. California, 376 U.S. 483 (1964) ......... 21, 29, 32,

Swain v. Alabama, Ala. Sup. Ct., 7 Div. No. 699 .........

Tatum v. United States, 321 F.2d 219 (9th Cir. 1963)

Teasley v. United States, 292 F.2d 460 (9th Cir. 1961)

United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d 71

(5th Cir. 1959), cert, denied, 361 U.S. 838 ...............

United States ex rel. McKenna v. Myers, 232 F. Supp.

65 (E.D. Pa. 1964) .......................................... -.... 26,28,

United States ex rel. Puntari v. Maroney, 220 F. Supp.

801 (W.D. Pa. 1963) ............................... ......................

United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53 (5th

Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 372 U.S. 924 ............ ............

United States ex rel. Stacey v. Pate, 324 F.2d 934 (7th

Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 377 U.S. 937 (1964) .............

United States v. Arrington, 215 F.2d 630 (7th Cir.

1954) .... ........................... ........... -.......... -.............. -.........

United States v. Block, 202 F. Supp. 705 (S.D.N.Y.

1962) ........................ - ................................- ....................

United States v. Blok, 188 F.2d 1019 (D.C. Cir. 1951)

United States v. Boston, 330 F.2d 937 (2d Cir. 1964),

cert, denied, 377 U.S. 1004 ............................................

United States v. Eldridge, 302 F.2d 463 (4th Cir. 1962)

United States v. Evans, 194 F. Supp. 90 (D.D.C. 1961)

United States v. Goodman, 190 F. Supp. 847 (N.D. 111.

1961) ............................................ -................ -..................

United States v. Haas, 106 F. Supp. 295, 109 F. Supp.

443 (W.D. Pa. 1952) ......................... ...................... -24,

United States v. Heine, 149 F.2d 485 (2d Cir. 1945) —

United States v. Hilbrieh, 341 F.2d 555 (7th Cir. 1965)

United States v. Horton, 328 F.2d 132 (3rd Cir. 1964),

cert, denied, 377 U.S. 970 ........ ....................................

United States v. Jeffers, 342 U.S. 48 (1951) ...........21,

33

36

24

28

50

29

27

50

26

23

26

32

28

28

24

26

25

25

22

22

29

V l l l

United States v. MacLeod, 207 F.2d 853 (7th Cir.

1953) ............................... ................................................24,25

United States v. Minor, 117 F. Supp. 697 (E.D. Okla.

1953) ................................. ............ ................................... 24

United States v. Mitchell, 322 U.S. 65 (1944) ................. 25

United States v. Page, 302 F.2d 81 (9th Cir. 1962) ....... 23

United States v. Pugliese, 153 F.2d 497 (2d Cir. 1945) 27

United States v. Rabinowitz, 339 U.S. 56 (1950) ......... 21

United States v. Rivera, 321 F.2d 704 (2d Cir. 1963) .... 25

United States v. Roberts, 179 F. Supp. 478 (D. D.C.

1959) ........................... 24,25

United States v. Ruffner, 51 F.2d 579 (D. Md. 1931) 27

United States v. Rykowski, 267 Fed. 866 (S.D. Ohio

1920) .................................................................................. 27

United States v. Sergio, 21 F. Supp. 553 (E.D.N.Y.

1937) ........................................................... 27

United States v. Sferas, 210 F.2d 69 (7th Cir. 1954),

cert, denied, 347 U.S. 935 .......................... ................. 26, 27

United States v. Smith, 308 F.2d 657 (2d Cir. 1962-63),

cert, denied, 572 U.S. 906 .............................................. 22

United States v. Walker, 197 F.2d 287 (2d Cir. 1952),

cert, denied, 344 U.S. 877 ................... 27

United States v. Walker, 190 F.2d 481 (2d Cir. 1951),

cert, denied, 342 U.S. 868 ......................... ...... ....... . 27

United States v. Ziemer, 291 F.2d 100 (7th Cir. 1961),

cert, denied, 368 U.S. 877 ............................... .............. 24

United States v. Zimmerman, 326 F.2d 1 (7th Cir.

1963) ............... ...... .................... ...................................... 28

Villano v. United States, 310 F.2d 680 (10th Cir. 1962) 22

Von Eichelberger v. United States, 252 F.2d 184 (9th

Cir. 1958)

PAGE

28

Waldron v. United States, 219 F.2d 37 (D.C. Cir.

1955) ................... ...........................................................26,29

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) ......... 37

Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1964), cert.

denied, 379 U.S. 931 ..................................................-.... 50

Williams v. United States, 263 F.2d 487 (D.C. Cir.

1959) ................... ................ -..... -----......... ....................... 26

Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507 (1948) ................... 43

Wion v. United States, 325 F.2d 420 (10th Cir. 1963),

cert, denied, 377 U.S. 946 ................. ......... ....... -...... . 28

Woodard v. United States, 254 F.2d 312 (D.C. Cir.

1958), cert, denied, 357 U.S. 930 .................................. 28

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) ------------ ---- - 37

Zap v. United States, 328 U.S. 624 (1946) .................... 26

Statutes

10 U.S.C. §920 (1964) ............................... *...... -................. 34

18 U.S.C. §2031 (1964) ..................................... -......... -.... 34

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) (1948) ............................................ - 2

28 U.S.C. §2241 (1958) ....................................................- 18

Rev. Stat. §1977 (1875), 42 U.S.C. §1981 (1964) ......... 37

Supreme Court Rule 19(1) (b) ....-.... -......................... - 22

Civil Rights Act of 1866, Ch. 31, §1, 14 Stat. 27 .........36, 38

Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §§16, 18,

16 Stat. 140, 144 ............................ -............................ 36

Ala. Code §§14-395, 14-397, 14-398 (1958) ................... 33

Auk. Stat. A nn. §3-118 (1956) ......................................4,17

IX

PAGE

I

A rk. Stat. A nn . §3-227 (1956) ........................................ 4,17

A rk. Stat. A nn . §39-208 (1962) ........................................6,17

A rk. Stat. A nn . §§41-805 to 41-810 (1964) ............. 42

A rk. Stat. A nn . §41-3403 (1964) ........................ 7 ,8 ,13,33

A rk. Stat. A nn . §41-3405 (1964) .................................. 33

A rk. Stat. A nn . §41-3411 (1964) .... 33

A rk. Stat. A nn . §43-2153 (1964) .................. ..........7,13,33

A rk. Stat. A nn . §§46-144, 145 (1964) ..... 42

A rk. Stat. A nn . §§55-104, 105 (1947) ........................ 42

A rk. Stat. A nn . §73-1218 (1957) ...... 42

A rk. Stat. A nn . §73-1614 (1957) .................................. 42

A rk. Stat. A nn . §73-1747 (1957) ............. . 42

A rk. Stat. A nn . §76-1119 (1957) ................. 42

A rk. Stat. A nn. §80-509 (1960) ......................... ............... 42

A rk. Stat. A nn . §80-2401 (1960) .................................. 42

A rk. Stat. A nn . §84-2724 (1960) ....... 42

D. C. Code A nn . §22-2801 (1961) ..................... 34

F la. Stat. A nn . §794.01 (1964) .......... 33

G.v. Code A nn . §26-1302 (1963) ............... 33

Ga. Code A nn . §26-1304 (1963) ............ 34

K y. R ev. Stat. A nn . §435.090 (1963) ............................ 34

L a. R ev. Stat. A nn . §14:42 (1950) .............................. ...... 34

Md. A nn . Code, art. 27, § 1 2 ................................................. 34

Md. A nn . Code, art. 27, §§461, 462 (1957) ..... .......... 34

Miss. Code A nn . §2358 (1956) ........................................ 34

V ernon’s Mo. Stat. A nn . §559.260 (1953) .................... 34

Nev. R ev. Stat. §200.360 (1963) ................................... . 33

Nev. R ev. Stat. §200.400 (1963) .......................... .............. 33

N.C. Gen. Stat. §14-21 (1953) .............................. .......... 34

PAGE

Okla. Stat. A nn ., tit. 21, §1111 (1958) ............... 34

Okla. Stat. A nn ., tit. 21, §§1114, 1115 (1958) ............ 34

S.C. Code A nn . §16-72 (1962) .......... ............................. 34

S.C. Code A nn. §16-80 (1962) ............................................. 34

Tenn. Code A nn . §§39-3702, 39-3703, 39-3704, 39-3705

(1955) ..................... .............................................................. 34

Tex. P en. Code A nn., art. 1183 (1961) ............................ 34

Tex. P en. Code A nn ., art. 1189 (1961) ........ 34

V a. Code A nn . §18.1-16 (1960) ........................................ 34

V a. Code A nn . §18.1-44 (1960) ............................................. 34

Other A uthorities

W eihofen, T he Urge to Punish, 164-165 (1956) ....... 42

Bullock, Significance of the Racial Factor in the Length

of Prison Sentences, 52 J. Cbim. L., Grim. & P ol.

Sci. 411 (1961) ............... ........................... ...................... 42

Fairman, Does the Fourteenth Amendment Incorporate

the Bill of Rights, 2 Stan. L. R ev. 5 (1949) ........... 36

Hartung, Trends in the Use of Capital Punishment, 284

A nnals 8 (1952) ................................ ..................... ....... 42

Lewis, The Sit-In Cases: Great Expectations, [1963]

Supreme Court R eview 101 ............................................ 43

Packer, Making the Punishment Fit the Crime, 77

H arv. L. R ev. 1071 (1964) .......... .................................. 44

tenBroek, Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, 39 Calif L. R ev. 171 (1951) .... 36

Weinstein, Local Responsibility for Improvement of

Search and Seizure Practices, 34 R ocky Mt. L. R ev.

150 (1962) .............. ........................................................ . 23

XI

PAGE

Wolfgang, Kelly & Nolde, Comparison of the Executed

and the Commuted among Admissions to Death

Row, 53 J. Crim. L., Grim. & P ol. Sci. 301 (1962) .... 42

Comment, 69 D ick. L. R ev. 69 (1964) ..... ...................... 22

Note, 51 Calif. L. R ev. 1010 (1963) ................................. 22

Note, U. III. L. F orum (1964) .......... ............................. 22

Note, 109 U. P a. L. R ev. 67 (1960) ............................ 35

Note, 113 U. Pa. L. R ev. 260 (1964) ............................... . 22

Note, Wis. L. R ev. 119 (1964) ..... .................................. 22

Annul., 31 A.L.R. 2d 1078 (1953) ......... .......................... 22

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 475 (Jan. 29, 1866)

1759 (4/4/1866) ................................................................. 38

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1758 (April 4, 1866) 38

New York Times, July 24, 1965, p. 1, col. 5 ............. ....... 45

United States Department of J ustice, B ureau of

P risons, National Prisoner Statistics, No. 32:

Executions, 1962 (April 1963) ..................................... 43

xii

PAGE

I n the

Supreme (tort of the Intteii Btdits

October Term, 1965

No..............

W illiam L. M axw ell ,

Petitioner,

v.

D an D. S teph en s , Superintendent of Arkansas

State Penitentiary.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Eighth Circuit entered in the above-entitled case on June

30, 1965.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Eighth Circuit (C.A. I ) 1 and the dissenting opinion of Judge

Ridge (C.A. 24) are as yet unreported. They are set forth in

1 The certified record, which is not printed, consists of six volumes.

Volume I contains the record of proceedings in the district court except

for the transcript of the hearing. It is cited as D.C. ------ .

Volumes II and III, paginated consecutively, contain the complete

record of proceedings in the Garland County Circuit Court and are cited

as A rk .------ .

Volume IV is the transcript of the hearing in the district court and is

cited as T r . ------ .

Volume V contains depositions and is not cited in this petition.

Volume VI contains the opinion and orders of the court of appeals and

is cited as C.A. ------ .

2

the appendix,2 pp. 2a, 26a. The opinion of the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas

(D.C. 39) is reported at 229 F. Supp. 205 and is set forth

in the appendix, p. 30a. The opinion of the Supreme Court

of Arkansas is reported at 236 Ark. 694, 370 S.W. 2d 113

and is set forth in the appendix, p. 55a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit was rendered on June 30, 1965

(C.A. 28). The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pur

suant to 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Petitioner, a Negro, was detained at the police station

on suspicion of rape of a white woman. His requests to use

a phone to call a lawyer or his family at home were denied.

Two white policemen went to his home at 5 :00 a.m. to obtain

evidence. They had no warrant. Only petitioner’s mother

and two younger brothers were at home. The policemen

were admitted by petitioner’s mother. They searched peti

tioner’s room and obtained a coat belonging to him. The

coat was used at his trial, which resulted in a sentence of

death.

a) Where petitioner’s mother was visibly upset, did not

know of her right to resist a warrantless search, and was

not informed of that right, did her acquiescence in the

search and seizure satisfy the requirements of voluntari

ness and understanding requisite to waiver of Fourth-

Fourteenth Amendment rights?

2 The appendix is separately bound.

3

b) If the answer to question (a) is yes, did acquiescence

by petitioner’s mother waive petitioner’s Fourth-Four

teenth Amendment rights as well as her own?

2. Where petitioner, a Negro sentenced to death for the

rape of a white woman, has shown that nine times as many

Negroes as whites have been executed for rape in Arkansas

although in three representative counties (to which inquiry

was limited) an equal number of Negroes and whites have

been convicted of rape, may the State deny that racial dis

crimination violating the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment produced such a result without

submitting proof that impartial and non-arbitrary factors

explain the grossly disproportionate number of Negro exe

cutions ?

3. Does Arkansas’ granting to the jury of unfettered

discretion to impose capital punishment for all offenses of

rape, irrespective of the existence of aggravating circum

stances, permit cruel and unusual punishment in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment? 4

4. Did the system of selecting petit jurors used in Gar

land County satisfy the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment where the qualifications of all pro

spective jurors wrere determined by reference to poll tax

books which, pursuant to state statute, designated the race

of each elector?

4

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the Fourth, Fifth, Eighth, and Four

teenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United States.

This case also involves the following Arkansas statutes:

A rkansas S tatutes A nnotated , §3-118 (1956) :

3-118. List of poll tax payers furnished county cleric

and election commissioners.—Not later than the 15th day

of October of each year the collector shall file with the

county clerk a list containing the correct names, alpha

betically arranged (according to the political or voting

townships, and according to color) of all persons who have

up to and including October 1st of that year paid the poll

tax assessed against them respectively. The correctness of

this list shall be authenticated by the affidavit of the col

lector in person. The county clerk shall at once record the

said list in a well bound book to be kept for that pur

pose . . . .

A rkansas S tatutes A nnotated , §3-227 (1956):

3-227. Evidence of right to vote—Filing and return of

documents—Additional list of voters—Poll tax receipts,

requirements— Certified poll tax lists—Rejection of bal

lots.—No person shall be allowed to vote at any primary

election held under the laws of this State, who shall not

exhibit a poll tax receipt, or other evidence that he has

paid his poll tax within the time prescribed by law to en

title him to vote at the succeeding general State election.

Such other evidence shall be:

(a) A copy of such receipt duly certified by the clerk of

the county court of the county where such tax was paid.

5

(b) Or, such person’s name shall appear upon the list

required to be certified to the judges of election by section

three of Act 320 of Acts of 1909 [§3-118].

Or, if any person offering to vote shall have attained the

age of twenty-one [21] years since the time of assessing

taxes next preceding such election, which period of assess

ment is here declared to mean between the second Monday

in May and the second Monday in September of each year,

and possesses the other necessary qualifications, and shall

submit evidence by written affidavit, satisfactory to the

judges of election, establishing that fact, he shall be per

mitted to vote.

All such original and certified copies of poll tax receipts

and written affidavits shall be filed with the judges of elec

tion and returned by them with their other returns of

election, and the said judges of election shall, in addition

to their regular list of voters, make an additional list upon

their poll books of all such persons permitted by them to

vote, whose names do not appear on the certified list of poll

tax payers, and such poll books shall have a separate page

for the purpose of recording names of such persons.

It shall be the duty of each elector, at the time of pay

ment of his poll tax, to state, and it shall be the duty of the

collector to record and certify in his receipt evidencing the

payment of such poll tax, the color, residence, postoffice

address (rural route, town or street address), voting pre

cinct, and school district, of such person at the time of the

payment of such tax, and all poll tax receipts not containing

such requirements shall be void and shall not be recognized

by the judges of election; provided, however, it shall not be

necessary to state or have certified the street address of

any such person in cities and towns where the numbering

of houses is not required by the ordinances thereof.

6

The certified lists required by section 3 of Act 320 of

1909 [§3-118] shall contain, in addition to the name of the

person paying such poll tax, his color, residence, post-

office address (rural route, town, or street address where by

ordinance the numbering of houses is required), the school

district and voting precinct, and such list shall be arranged

in alphabetical order, according to the respective voting

precincts. The county election commissioners shall supply

the judges of primary elections with printed copies of such

lists. . . .

A rkansas Statutes A nnotated §39-208 (1962) :

Preparation of lists of petit jurors and alternates—In

dorsement of lists.-—The commissioners shall also select

from the electors of said county, or from the area constitut

ing a division thereof where a county has two [2] or more

districts for the conduct of circuit courts, not less than

twenty-four (24) nor more than thirty-six (36) qualified

electors, as the court may direct, having the qualifications

prescribed in Section 39-206 Arkansas Statutes 1947 Anno

tated to serve as petit jurors at the next term of court;

and when ordered by the court, shall select such other num

ber as the court may direct, not to exceed twelve [12]

electors, having the same qualifications, for alternate petit

jurors, and make separate lists of same, specifying in the

first list the names of petit jurors so selected, and certify

the same as the list of petit jurors; and specifying in the

other list the names of the alternate petit jurors so se

lected, and certifying the same as such; and the two [2]

lists so drawn and certified, shall be enclosed, sealed and

indorsed “ lists of petit jurors” and delivered to the court

as specified in Section 39-207, Arkansas Statutes 1947,

Annotated for the list of grand jurors.

7

A rkansas S tatutes A nnotated §41-3403 (1962):

41-3403. Penalty for Rape.—Any person convicted of the

crime of rape shall suffer the punishment of death [or life

imprisonment], [Act Dec. 14, 1842, §1, p. 19; C. & M. Dig.,

§2719; Pope’s Dig., §3405.]

A rkansas S tatutes A nnotated §43-2153 (1962):

43-2153. Capital cases— Verdict of life imprisonment.—

The jury shall have the right in all case where the punish

ment is now death by law, to render a verdict of life im

prisonment in the State penitentiary at hard labor.

Statement

Petitioner William L. Maxwell, a Negro, was charged by

information for the crime of rape on November 7, 1961

( Ark. 1). He was convicted in the Circuit Court of Garland

County, Arkansas, and sentenced to death on April 5, 1962

(Ark. 42). The conviction was affirmed by the Supreme

Court of Arkansas, and rehearing was denied.

A petition for writ of habeas corpus was filed in the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas on January 20, 1964 (D.C. 1). It alleged, inter

alia, that the number of Negroes on jury panels in Gar

land County was systematically and intentionally limited

through the use of poll tax books designating the race of

qualified jurors (D.C. 2-3). On January 21, 1964, the dis

trict court issued an order to show cause and a stay of exe

cution (D.C. 6). On January 31, 1964, the court permitted

an amendment to the habeas corpus petition alleging that

clothing of petitioner was seized during an unlawful search

and introduced at trial (D.C. 11-13). On February 12, 1964,

petitioner filed a second amendment, alleging that Ark.

8

Stat. Ann. §41-3403 (1962 Repl. Vol.), providing for the

death penalty upon conviction of rape, was applied with

unequal severity against Negroes (D.C. 33). It was al

leged that imposition of the death penalty in rape cases not

involving loss of life was erratic and in conflict with the

mores, principles and basic concepts of fairness of civil

ized societies (D.C. 34). At the hearing on February 12,

1964, the district court permitted the filing of the second

amendment (Tr. 22).

Following the hearing held on February 12, 13, and 27,

the district court dismissed the petition for writ of habeas

corpus and vacated the stay of execution on May 6, 1964

(D.C. 62). On May 19,1964, petitioner filed notice of appeal

(D.C. 70). The district court granted a petition for cer

tificate of probable cause for appeal and stayed execution

pending appeal (D.C. 67).

The United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Cir

cuit affirmed on June 30, 1965 (C.A. 1, 28), Judge Ridge

dissenting on the search and seizure issue (C.A. 24).

On July 13, 1965, the court of appeals granted a stay of

the mandate for thirty days. If the clerk of the court of

appeals receives within that time period a certificate from

the clerk of this Court that a petition for writ of certiorari

has been filed, the stay is to continue in effect until final

disposition of the ease by this Court (C.A. 29).

Search and Seizure

In his amended petition for the writ of habeas corpus,

petitioner contended that his Fourteenth Amendment rights

against unreasonable search and seizure had been violated

by the use made at his trial of a blue coat seized from his

9

bedroom closet by police officers acting without a warrant

(D.C. 11). The court of appeals found that the

blue coat in question was obtained from that closet.

It was eventually sent to the FBI laboratory. At the

trial there was expert testimony that fibers in the coat

matched others found on the victim’s pajamas and on

part of a nylon stocking picked up near the scene of

the crime, and that fibers in the pajamas matched those

found on the coat (C.A. 17).

Accordingly, the court of appeals—as had the district court

—entertained petitioner’s Fourth-Fourteenth Amendment

contentions on the merits (C.A. 16; see D.C. 45). It rejected

those contentions, finding that the warrantless seizure of

the coat was validated by consent given the officers, in

petitioner’s absence following his arrest, by petitioner’s

mother (C.A. 23).

The facts surrounding the search and seizure may be

concisely stated by adopting the findings of the court of

appeals, with a few additions supported by the testimony

of police officers or by the uncontradicted testimony of

petitioner’s witnesses in the district court. In the para

graphs which follow, the quoted portions are taken from

the circuit court’s opinion (C.A. 16-18) ; bracketed inser

tions with record references are from the transcript in the

district court.

“ . The offense took place at approximately three

o'clock in the morning of November 3, 1961. It was raining

and wet. The victim was promptly taken by the police to

a hospital. At the hospital she described her assailant to

Captain Crain of the Hot Springs Police Department and

to Officer O.D. Pettus, a Negro. She stated that the man

had told her he was Willie C. Washington. Two persons

with that name, senior and junior, were brought before her

10

but she identified neither. [A third Negro man was also

brought in but not identified. (Tr. 256, 258, 262-263; testi

mony of Captain Crain and of the victim.)] She described

her attacker in greater detail. Pettus thereupon suggested

that it might have been Maxwell. Officer Childress, who

was on car patrol duty and in uniform at the time, was

directed by radio to pick up Maxwell. He went to the

Maxwell home. The defendant’s mother, then age 38, an

swered his knock. [Maxwell’s father was then away from

home at work. (Tr. 159; uncontradicted testimony of Max

well’s father.)] He told her he wanted to talk to William.

She let him enter, checked to see if her son was in, and

led Childress to the bedroom occupied by Maxwell and two

younger sons. [Childress awakened Maxwell by shining a

flash in his face. (Tr. 135, 186-187; uncontradicted testi

mony of Maxwell’s mother and Maxwell.)] Childress told

Maxwell he wanted to talk to him down town and asked

him to dress. Childress testified that Maxwell went to the

closet for clothes that were hanging there in a wrapper,

and that he asked him ‘to put on these other clothes here

that he had on.’ The latter were wet. Maxwell testified

that he was told to put on the clothes he had on that night,

that he went to the closet to get these, that he was then

told to put on the clothes folded on the chair, that he was

going to take those clothes to the cleaners, and that they

were not his. [It is uncontested that Maxwell objected to

wearing the clothes on the chair, which he said were wet

and not his, but that Childress told him to put them on

anywrny. (Tr. 267; testimony of Officer Childress.)]

[Maxwell’s mother testified that she was upset at this

time. (Tr. 135.) At the hearing below, Childress was asked

whether he had advised Maxwell or his parents (sic) that

they were entitled to consult with an attorney, and replied:

“ No, I didn’t give them any advice at all because I didn’t

11

know whether he was being arrested or what. I just re

ceived the call over the radio to go pick him up. I didn’t

know what it was.” (Tr. 267.)]

“Maxwell was taken to the hospital and before the victim.

She at first did not identify him as her attacker but wit

nesses described her as visibly disturbed and shaking when

he stood before her. She later said she recognized him but

feared for her life if she identified him. Maxwell was

taken from the hospital to the police station.

[The district court found “ that when petitioner was

taken into custody and incarcerated in the City Jail he

was not permitted to see his parents or a lawyer.” (D.C.

49.) This finding was based on petitioner’s testimony that

“I asked them could I use the telephone to call my—my

mother, somebody to come up, a lawyer or something, and

they told me I weren’t going to use the phone or nothing

. . . ” (Tr. 189; see also Tr. 190.) The testimony is un

contradicted; Captain Crain testified only that he did not

advise petitioner of his right to consult an attorney (Tr.

250), and that he made no attempt to bring petitioner

before a magistrate because there was no magistrate’s court

until 9:00 a.m., the magistrate had traffic court at that

time, and “We still had not completed our investigation.”

(Tr. 253.) Petitioner’s incommunicado detention continued

for two or three days thereafter in the jail to which he

had been removed to avoid mobbing. (Tr. 192-196; uncon

tradicted testimony of petitioner.)]

“Both sides admit that the exact times and place of

Maxwell’s arrest ‘is not entirely clear from the record’.

It might have been at the home at about four a.m. or

shortly thereafter at the hospital.

“ Captain Crain, with Officer Timms, went to the Maxwell

home about five a.m. to get, as he testified at the habeas

12

corpus hearing, ‘some more clothes that we thought might

help us in our investigation of this case’ or, as he testified

at the trial, ‘I was looking for a particular object . . . I

wanted what he was wearing that night’. They had no

search warrant. Mrs. Maxwell permitted them to enter.

[She testified below: “I did not know nothing about ask

ing the officer for a search warrant. I didn’t—I just didn’t

know . . . ” (Tr. 146.) And, again, responsive to a question

why she had not asked the officers for a warrant: “Be

cause I didn’t know—know to just quite honestly I didn’t

know—I was—well, I was half asleep and I just wasn’t—

didn’t think to ask him. And I kept-—my children were

all at home and I just didn’t think anything were wrong.”

(Tr. 156.)] They were in uniform. The testimony is in

conflict as to whether Mrs. Maxwell was then informed

of any charge against her son; Crain said he so advised

her but she stated, ‘He didn’t say nothing about no rape

case’. (The district court found she had been so advised).

She directed the officers to the clothes closet. . . . [Captain

Crain testified that Officer Timms checked the closet while

he, Crain, talked to petitioner’s mother. “Well, we—I felt

sorry for her. She was in—well, she wasn’t feeling any

too good being—having a thing like that happen and her

son being accused.” (Tr. 243.)]

“ Mrs. Maxwell was understandably upset at the times

the officers called at her home. In the margin we quote

her testimony as to both the first call12 and the second call.13

12 “ . . . it was late and I was asleep and someone knocked on

the door and I woke op and I asked who was it and he said the

policeman and I went to the door to let him in. He asked me did

I have a son here by the name of William and I told him yes and

he jost come on in, he didn’t have a search warrant or anything

and I let him. I didn’t know any better myself but I—I didn’t

know that he— you know, everything was all right, my children

were at home and all and I just let him in.”

13 “ I opened the door and I was afraid not to let them in because

—you know— when they said they were police officers—well, you

13

just—I ’ve just always— I just let the police officers in because I

just feel like he is for peace and all, and I just— I don’t know, I

didn’t know anything—I never been in anything like this and

I just let them in and I still didn’t think anything, didn’t any of

those officer (sic) have any search warrant or anything, didn’t

show me anything like that.”

Maxwell’s father worked at night and was not home when

the officers called.”

[Asked at the hearing below whether he had told Mrs.

Maxwell that she did not have to relinquish the items of

clothing to him, Captain Crain replied that he did not

recall. (Tr. 248.) He testified flatly that he did not men

tion to Mrs. Maxwell that things taken could he used in

evidence against her son. (Tr. 249.)]

Capital Punishment for Rape

Petitioner’s second amended petition in the district court

challenged the constitutionality in their application to him

of the Arkansas statutes allowing capital punishment for

rape in the discretion of the jury. Ark. S t a t . A xn . §§41-

3403, 43-2153 (1964 Repl. Vols.), p. 7, supra. He con

tended that prosecutors and juries applied the statutes

racially, in that Negroes convicted of rape upon white

women were usually sentenced to death, while other classes

of rape convicts usually received lesser sentences (D.C.

33); that the death sentence in his case “where life has

not been forfeited is so erratic so as to deny due process

of law” and equal protection of the laws (D.C. 34); and

that in such a case the death sentence constituted cruel

and unusual punishment (D.C. 34).8 In support of the 3

3 The language of part (2), para. 3, of the second amendment to the

petition paraphrases the language of the opinions dissenting from denial

o f certiorari in Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U.S. 889 (1963) (D.C. 34), and

was understood by the district court to raise an Eighth-Fourteenth Amend

ment issue (Tr. 10-13).

14

claim of racial discrimination, petitioner’s counsel sought

leave to take testimony of certain state officials, and to

submit to the prosecutors or clerks of court of the 72

Arkansas counties not to be covered by oral testimony

interrogatories or questionnaires inquiring with respect

to all rape prosecutions after January 1, 1954 the name

and race of the defendant, the race of the prosecutrix, the

extent to which deadly force was attempted or employed

in the course of the offense, and the disposition including

sentence.4 Counsel for the State expressed doubt that such

information could be supplied by the prosecutors or county

clerks (Tr. 312-313), and the district court thereupon

declined “ to go into an expedition of trying to submit it

to the 72—72-—75 clerks when I am convinced that they

cannot furnish most of it.” (Tr. 313.) However, over the

strenuous objection of State’s counsel (Tr. 314-317), and

notwithstanding the court’s disposition to believe “that

the information that the petitioner is trying to obtain

can’t be obtained” (Tr. 317), the court did agree, as a

“ trial run” (Tr. 317) to hear testimony of state officials

for three counties, in order to “ see how fruitful it might

be on a smaller basis” (Tr. 318; see Tr. 317-321). Ac

cordingly, petitioner presented the testimony of the cir

cuit clerk, sheriff and prosecuting attorney of Garland

County (Tr. 327-356), the circuit clerk and prosecuting

attorney of Pulaski County (Tr. 357-385), and the circuit

4 The request to take depositions and to submit interrogatories and

questionnaires was first made in the second amendment to the petition

(D.C. 34). It was pressed at the hearing (Tr. 6-10, 14-26) and, following

an initially inconclusive disposition (Tr. 25-26), renewed (Tr. 227). The

district eourt asked counsel for the petitioner to prepare for the court’s

consideration the sort of interrogatories he wished to submit (Tr. 228-229) ;

this was done (Tr. 311-312); and petitioner’s request for leave to submit

the interrogatories renewed again (Tr. 310-311). After the district court

determined to permit testimony limited to three counties as a “ trial run”

(see text infra), petitioner’s counsel put the draft questionnaire into the

record to preserve his point (Tr. 321).

15

clerk, sheriff and prosecuting attorney of Jefferson County

(Tr. 386-421). The evidence given by these officials is

summarized in the margin, substantially in the words of

the court of appeals.5 It demonstrated, first, that the in

formation sought by the petitioner was, for the most part,

available: of 59 defendants charged in three counties over

ten years, the race of all but four defendants was known;

the race of 47 of their 63 victims was known; and dispo

5 The quoted passage which follows is from the opinion of the court of

appeals (C.A. 7-8). Bracketed insertions supply omitted information,

derived from the testimony of the state officials at Tr. 327-421.

“As to Garland County, for the decade beginning January 1, 1954,

Maxwell’s evidence was to the effect that seven whites were charged

with rape (two of white women and the race of the other victims not

disclosed), with four whites not prosecuted and three sentenced on

reduced charges; that three Negroes were charged with rape, with one

of a Negro woman not prosecuted and another of a Negro receiving

a reduced sentence, and the third, the present defendant, receiving

the death penalty. With respect to Pulaski County for the same

decade, there were 11 whites (two twice) and 10 Negroes charged,

with the race of the victim of two whites and one Negro not dis

closed. Three whites received a life sentence. [Two of these had white

victims; the third, a victim of undisclosed race.] One white was ac

quitted of rape of a Negro woman. One received a sentence on a

reduced charge [victim, white], two were dismissed [victims, white],

two cases remained pending [victims, white], one was not prosecuted

[victim of undisclosed race], and the last was executed on a convic

tion for murder [victims, white; two rape charges were nol prossed].

Of the Negroes, three with white victims and two with Negro victims

received life. One case was dismissed [victim of undisclosed race],

one was not arrested [victim, white], two with Negro victims were

sentenced on reduced charges, and one, Bailey, with a white victim,

was sentenced to death. In Jefferson County eight Negroes were

charged, with the cases against five dismissed [victims, one white, one

Negro, three of undisclosed race], another dismissed when convicted

on a murder charge [victim of undisclosed race], and two receiving

sentences on reduced charges [victims, Negro], Sixteen whites were

charged. One was charged three times with respect to Negro victims

and as to two of these charges received five years suspended on a

guilty plea. [The remainder had white victims, except in the single

case indicated infra.] Two others received three year sentences. One

is pending, one was executed, and the rest were dismissed [one of

these latter having a victim of undisclosed race.] The race of four

defendants was not disclosed; three of these cases were dismissed and

one is pending.”

16

sitions of all prosecutions, including sentence, were known.

Second, the evidence showed that for the counties and

period covered, Negroes were charged with rape consider

ably less frequently than whites (by a ratio of 2:3) and

were convicted o f rape no more frequently than whites.

Specifically, the figures a re :

Garland Pulaski Jefferson Total

Number of White 7 11 (two twice) 16 (one thrice) 34 (two twice)

defendants (one thrice)

charged Negro 3 10 8 21

Total 10 21 28 (four un- 59

known race)

Number of

defendants White 0 3 4 (one twice) 7 (one twiee)

convicted Negro 1 6 0 7

of rape Total 1 9 4 14

Number of

defendants White 0 0 1 1

sentenced Negro 1 1 0 2

to death Total 1 1 1 3

On the basis of evidence in the state court transcript, it

further appears, as found by the court of appeals, “ that,

in the 50 years since 1913, 21 men have been executed for

the crime of rape [in Arkansas]; that 19 of these were

Negroes and two were white; that the victims of the 19

convicted Negroes were white females; and that the vic

tims of the two convicted whites were also white females.”

(C.A. 7.) The court of appeals held, as did the district

court, that this was an insufficient showing of racially

discriminatory application of the death penalty for rape

(C.A. 8; see D.C. 60), and both courts refused to give

consideration to petitioner’s contention that capital pun

ishment for rape was cruel and unusual punishment, the

circuit court saying that a declaration of the unconstitu

tionality of the death penalty on this ground “must be

for the Supreme Court in the first instance and not for

17

us.” (C.A. 11-12; and see the district court’s similar dis

position at D.C. 61).

Selection of Jury Panels

In Garland County, Arkansas, petit jury lists were se

lected by a jury commission consisting of three commis

sioners, who met periodically to draw up a list of names

(Tr. 47, 64). They relied primarily on their knowledge

of persons in the community (Tr. 61), but also used a

telephone book (Tr. 60, 77) and a list of persons who had

previously served (Tr. 55, 77).

At the time of petitioner’s trial, only qualified electors

who had paid the poll tax were eligible to be jurors. Ark.

Stat. Ann. §3-227 (1956); §39-208 (1962). The jury com

missioners checked the poll tax books to determine

whether the persons they had selected were qualified

(Tr. 70, 80). An Arkansas statute required that poll tax

books designate the race of all qualified electors. Ark.

Stat. Ann. §3-118. The poll tax book for September 1961,

introduced in evidence as Exhibit I, showed a small “ c”

after the names of Negro electors (Tr. 57, 59).

After the jury commission completed the jury list, the

commission transmitted the list to the circuit clerk (Tr.

99-101). The circuit clerk for Garland County between

1955 and 1963 testified that the lists had “c’s” after the

names of Negroes when he received them (Tr. 48-50).

The clerk also testified that he copied the lists, placing the

names and racial markings into a jury book (Tr. 42).

The issue of discriminatory selection of jury panels was

not raised in the state courts. Following petitioner’s ap

prehension on November 3, 1961, two attorneys were ap

pointed to defend him on November 28, 1961 (Ark. 2).

They were discharged at their request on February 5,

18

1962 (Ark. 15). On January 31, 1962, Attorney Christopher

C. Mercer was hired to defend petitioner (Ark. 13). Mercer

discussed many aspects of the case with petitioner, in

cluding the jury panel, but he did not discuss with peti

tioner whether to raise the issue of racial discrimination

in the jury selection process (Tr. 298, 305-306).

Jurisdiction of the District Court

Jurisdiction of the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Arkansas was based on 28 U.S.C. §2241.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Certiorari should be granted to determine the legal

ity of search of petitioner’s home without a warrant,

in petitioner’s absence, under purported consent of

his mother.

Two issues arising out of the search of petitioner’s home

and seizure of his clothing without a warrant call for the

exercise of this Court’s certiorari jurisdiction. The State

of Arkansas seeks to support the search and seizure under

consent given by petitioner’s mother in his absence fol

lowing his arrest. Petitioner contends, first that his

mother’s acquiescence in the search and seizure was not

voluntary and understanding; second, that her acquiescence

could in no event effect a waiver of petitioner’s Fourth-

Fourteenth Amendment rights. The district court rejected

petitioner’s contentions on one theory and the court of

appeals on another, Judge Ridge dissenting. On this foun

dation, relief against the death penalty has been denied.

19

The facts surrounding the search and seizure issues have

been set forth at pp. 8-13, supra. Except in a minor point,

they are uncontested. A white police officer went to the

home of petitioner’s Negro family in Hot Springs, Arkan

sas, shortly before 4 :00 a.m. Petitioner’s father was away

at work; petitioner’s 38 year old mother, petitioner, and

two brothers were at home asleep. The officer woke peti

tioner’s mother by knocking at the door. She asked who

was there; he said it was a policeman; she let him in.

“He asked me did I have a son here by the name of

William and I told him yes and he just come on in, he

didn’t have a search warrant or anything and I let him

in. I didn’t know any better myself, but I—I didn’t know

that he—you know, everything was all right, my children

were at home and all and I just let him in.” P. 12, supra.

Once inside, the officer awakened petitioner by shining

a flashlight in his face and told him to get dressed. He

refused to permit petitioner to put on the clothing chosen

by petitioner, ordered him to put on other clothing. Peti

tioner was told that he was being taken to the police

station, that the police wanted to talk to him. He was not

told why. Petitioner’s mother was not told that she could

call an attorney; she was not told the charges against

petitioner; the officer “ didn’t give them any advice at all

because I didn’t know whether he was being arrested or

what.” Pp. 10-11, supra.

Petitioner was taken to a hospital for identification by

a white rape victim, then to the police station where he

was held incommunicado and refused permission to phone

a lawyer or his parents. One hour later, two white police

officers returned to petitioner’s home. Petitioner was then

incarcerated; it was about 5:00 a.m.; and although the

officers went for the specific purpose of obtaining clothing

which would incriminate petitioner, they sought no search

warrant. Petitioner’s father was still not home. They

20

asked petitioner’s mother if they could come in take some

of petitioner’s clothing. She let them in and directed them

to the closet. “ I opened the door and I was afraid not to

let them in because— you know—when they said they were

police officers—well, you just—I ’ve just always— I just

let the police officers in because I feel like he is for peace

and all, and I just—I don’t know, I didn’t know anything—

I never been in anything like this and I just let them in

and I still didn’t think anything, didn’t any of those officer

have a search warrant or anything, didn’t show me any

thing like that.” P. 12, supra. “ I did not know nothing

about asking the officer for a search warrant.” P. 12, supra.

Petitioner’s mother testified below that the officers had not

told her the charges against her son. Crain contradicted

this, said that he told her the charges and—as might be

expected of a Negro mother whose son is charged with

rape of a white woman in Arkansas—“well, she wasn’t

feeling any too good being—having a thing like that hap

pen and her son being accused.” P. 12, supra. In any

event, the mother’s testimony that she did not know the

officers needed a warrant to make the search was uncon

tested. Captain Crain said he did not recall that he told

Mrs. Maxwell she need not relinquish the clothing, and

testified flatly that he did not advise her the clothing

could be used against her son. While he was talking to

her, his companion officer took the coat which provided a

damaging link in the evidence later used to support peti

tioner’s conviction and sentence of death.

On this record, the district court found that it was the

mother’s “ free and voluntary choice to permit the police

to enter and search the closet.” (D.C. 49.) “However, the

propriety of the search and seizure need not rest solely

upon the consent given by petitioner’s mother. The law

fulness of this search and seizure is based upon a eonsi-

2 1

deration of all the facts and circumstances. . . . [TJhere

was nothing unfair, unreasonable or oppressive in the

conduct of the police in the performance of the search

and seizure. . . .” (D.C. 49.) Apparently recognizing the

untenability of this latter ground,6 the court of appeals

6 Although language in some of this Court’s eases has suggested that the

test of validity of a search and seizure under the Fourth Amendment is

general reasonableness, e.g., United States v. Rabinowitz, 339 U.S. 56

(1950), the Court has never sustained the warrantless search of a dwelling

not incident to arrest unless validated by consent. And, at least since 1950,

the Court’s decisions have made clear that a warrantless search is eo ipso

unreasonable and unconstitutional, e.g., United States v. Jeffers, 342 U.S.

48 (1951) ; Chapman v. United States, 365 U.S. 610 (196.1), unless “ ‘ .

brought . . . within one of the exceptions to the rule that a search must

rest upon a search warrant.’ ” Stoner v. California, 376 U.S. 483, 486

(1964), quoting Rios v. United Slates, 364 U.S. 253, 261 (1960). See also

Jones v. United States, 357 U.S. 493 (1958). Those exceptions are

specific. There are special rules relating to search o f moving vehicles,

stemming from Carroll v. United States, 267 U.S. 132 (1925), not in

volved here. There is the doctrine allowing search incident to a valid ar

rest, United States v. Rabinowitz, supra, which cannot validate the present

search. Preston v. United States, 376 U.S. 364 (1964). Cases involving

“ abandoned property,” see Abel v. United States, 362 U.S. 217 (1960),

fall outside the scope of “ persons, houses, papers, and effects” in which

the Fourth Amendment guarantees the citizen against unreasonable search

and seizure. See Hester v. United States, 265 U.S. 57 (1924). But peti

tioner’s home and clothing are clearly within the protection of the Amend

ment and, inside that sphere, the Court’s decisions allow only the excep

tions enumerated above to the warrant requirement. Dictum in a few

cases also suggests that a warrant may be foregone if compelling neces

sity to seize easily transported or destroyed contraband or instruments of

crime makes resort to a magistrate impossible. Johnson v. United States,

333 U.S. 10 (1948) ; Chapman v. United States, supra. But no such

necessity has been found by any of the courts below; nor could it have

been on this record. Hence, absent consent, the search and seizure here

were unconstitutional.

However, even were the question under the Fourth Amendment one—

as the district court believed—of general reasonableness, fairness and un

oppressiveness, it would be difficult to imagine a more unreasonable, unfair

and oppressive search. Having petitioner in their custody and seeking

items of his clothing to incriminate him, the police did not ask his per

mission to seize them. Instead, they detained him incommunicado, re

fused him leave to phone a lawyer or the persons at his home. Then,

without a warrant, at 5 :00 a.m., they went to petitioner’s dwelling and

intruded on his mother for the second time that night. Uniformed, and

without explaining that she had a right to refuse them entry, they asked

permission to come in, which she—unknowing—granted.

rested the validity of the search solely upon its finding

of consent. (C.A. 19, 23.)

A . The search and seizure issues are important,

requiring consideration by this Court on

certiorari.

The two issues thus presented—the requisites for valid

waiver of the requirement of a search warrant, and the

effect of waiver by one cotenant upon the Fourth-Four

teenth Amendment rights of another—clearly present “an

important question of federal law which has not been, but

should be, settled by this court.” Supreme Court Rule

19(1) (b). The circuit courts are in conflict on both issues.

(1) No issue under the Fourth Amendment is more fre

quently litigated than the validity of consent to a war

rantless search.7 Nor is any issue more critical to the

Amendment’s effective protection, for where consent is

found all of the scrupulous safeguards preserved by this

Court’s decisions as limitations upon official intrusion are

nullified. Not only is no warrant required, but—the pro

tection of the Amendment being deemed waived—searches

7 In addition to the cases collected in the following pages, see, e.g., these

recent federal circuit court decisions: Mosco v. United States, 301 F.2d

180 (9th Cir. 1962); United States v. Smith, 308 F.2d 657 (2d Cir. 1962)

Villano v. United States, 310 F.2d 680 (10th Cir. 1962); Frye v. United

States, 315 F.2d 491 (9th Cir. 1963) ; Robinson v. United States, 325 F.2d

880 (5th Cir. 1964) ; Gatlin v. United States, 326 F.2d 666 (D.C. Cir.

1963) ; United States v. Horton, 328 F.2d 132 (3d Cir. 1964) ; United

States v. Hilbrich, 341 F.2d 555 (7th Cir. 1965). Litigation of the issue

in the State courts is not less frequent, see e.g., the California cases col

lected in Note, 51 Calif. L. R ev. 1010 (1963); State v. Hanna, 150 Conn.

457, 191 A.2d 124 (1963) ; State v. Scrotsky, 39 N.J. 410, 189 A.2d 23

(1963) ; Commonwealth v. Wright, 411 Pa. 81, 190 A.2d 709 (1963) ; Holt

v. State, 17 Wis.2d 468, 117 N.W.2d 626 (1962), and the importance of

the question has made it the subject of much recent law review comment,

e.g., Comment, 69 D ick . L. R ev. 69 (1964) ; Comment, [1964] U. III. L.

F orum 653; Note, 113 U. Pa . L. R ev. 260 (1964); Note, [1964] W is. L.

R ev. 119. For earlier state cases, see Annot., 31 A.L,R.2d 1078 (1953).

23

and seizures may proceed without probable cause8 and

unfettered of any other constraint of reasonableness.9

Little wonder that “consent” is the policeman’s preferred

authority to search; that in 1954 a federal circuit court

remarked upon “this increasing practice of federal officers

searching a home without a warrant on the theory of

consent . . .” ;10 that the response of more than one state

police official following Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961),

was, in substance: “We are going to get consent to search

forms similar to the ones used by the F.B.I.” 11

(2) Noth withstanding frequent litigation, the decisions

of the lower courts are in irresolvable conflict and con

fusion. All courts agree, of course, that consent must be

“voluntary” to be effective. But, as the Ninth Circuit has

recently said, “ In other contexts the word voluntary might

connote anything from enthusiastic action taken on one’s

own initiative, at one extreme, to grudging action just

short of being compelled by what the law would regard

as duress, at the other.” Martinez v. United States, 333 F.2d

405, 407 (9th Cir. 1964). Far from giving meaning to the

concept of voluntariness as respects consent to a warrant

less search, the circuit courts of appeals have more or

less explicitly declared the concept not susceptible of

reasoned analysis. “ Each case necessarily depends upon

its own facts. The mere fact that a particular panel of

this court may feel that another panel, in a prior decision,

was mistaken in holding that a finding was ‘clearly erro

neous’ is not a basis for convening the court in bank and

overruling the prior decision.” United States v. Page, 302

8 See Rios v. United States, 364 U.S. 263 (1960).

9 See, e.g., Davis v. United States, 327 F.2d 301 (9th Cir. 1964).

10 United States v. Arrington, 215 F.2d 630, 637 (7th Cir. 1954).

11 See the Appendix to Weinstein, Local Responsibility for Improve

ment of Search and Seizure Practices, 34 R ocky Mt . L. R ev. 150, 176, 177

(1962). For similar responses, see id. at 178-179.

24

F.2d 81, 86 (9th Cir. 1962), distinguishing Channel v. United

States, 285 F.2d 217 (9th Cir, 1960). See also Hart v.

United States, 316 F.2d 916, 920 (5th Cir. 1963); United

States v. Ziemer, 291 F.2d 100, 103 (7th Cir. 1961); Burge

v. United States, 332 F.2d 171, 173 (8th Cir. 1964); Tatum

y. United States, 321 F.2d 219, 220 (9th Cir. 1963). Ex-

pectably, the result of thus calling consent a “question of

fact,” without attempting to formulate any general prin

ciples of law which tell the trier what facts he is to in

quire about and what he is to do if he finds one set of

facts rather than another, has been serious inter-circuit

conflict.12 In United States v. Roberts, 179 F. Supp. 478

(D.D.C. 1959), Judge Youngdahl found a mother’s con

sent involuntary on facts virtually indentieal with those of

the present case. This sort of fortuitous result may be

blinked away, under the prevailing lore of the circuit courts,

by saying that two district judges took different views

on the same question of fact. But when the cases are closely

compared, it becomes apparent that what controlled the

differing results were differing views on an unarticulated

question of law: whether one who does not know and is

not told that officers cannot make a search without a war

rant should be held to waive the warrant requirement by

agreeing to a request for leave to search. Judge Young-

12 Compare Pekar v. United States, 315 F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1963), with

United States v. Ziemer, 291 F.2d 100 (7th Cir. 1961). Compare Jliggins

v. United States, 209 F.2d 819 (D.C. Cir. 1954), with United States v.

MacLeod, 207 F.2d 853 (7th Cir. 1953). Compare Heed v. Rhay, 323 F.2d

498 (9th Cir. 1963), with United States v. Evans, 194 F. Supp. 90 (D.D.C.

1961). Compare United States v. Haas, 106 F. Supp. 295, 109 F. Supp.

433 (W.D. Pa. 1952), with United States v. Minor, 117 F. Supp. 697

(E.D. Okia. 1953). Underlying these inconsistent results are large in

consistencies of attitude. Compare the inhospitality toward a finding of

consent by the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit,

e.g., Judd v. United States, 190 F.2d 649, 651-652 (D.C. Cir. 1951), with

the hospitality toward such a finding by the Court of Appeals for the

Ninth Circuit, e.g., Martinez v. United States, 333 F.2d 405, 407 (9th

Cir. 1964).

25

dahl assumed that the answer to this question was nega

tive;18 District Judge Young below assumed that it was

positive; the Court of Appeals below affirmed without dis

cussing the question; and, indeed, the question has not

been explicitly framed in any circuit court decision.13 14 Surely

this question is one which permits and rationally demands

an answer in law; but until this Court grants review to

frame and decide such subordinate questions underlying

the issue of consent, circuit court decisions in cases involv

ing life or death will continue to be made lawlessly.

This Court has not decided a case involving the volun

tariness of consent to search and seizure in almost twenty

years. The few decisions prior to that time do not squarely

address the questions arising in case after case today.15 16

13 In Roberts, defendant’s mother had been told by the searching officers

that they were not permitted to search without a warrant unless she con

sented. But Judge Youngdahl found: “ It is difficult to believe that this

particular woman understood the significance of what the officers told her;

it is quite implausible to believe she was aware a search warrant was a

prerequisite to a valid search.” 179 F. Supp. at 479. Therefore, Judge

Youngdahl found her consent ineffective. In the present case, Judge

Young found consent by petitioner’s mother effective on a record which

makes clear that she did not know and was not told that a search warrant

was a prerequisite to a valid search.

14 In a number of cases where effective consent has been found, it ap

pears the person consenting' was told that, unless he consented, a search

could not be made without a warrant. United States v. Heine, 149 F.2d

485 (2d Cir. 1945) ; United States v. Rivera, 321 F.2d 704 (2d Cir. 1963) ;

United States v. MacLeod, 207 F.2d 853 (7th Cir. 1953) ; Burge v. United

States, 332 F.2d 171 (8th Cir. 1964); United States v. Haas, 106 F. Supp.

295, 109 F. Supp. 443 (W.D. Pa. 1952). But consent has also been found

where no such warning was given, e.g., McDonald v. United States, 307

F.2d 272 (10th Cir. 1962) (alternative ground), and petitioner has found

no circuit decisions squarely facing the question.

16 Gouled v. United States, 255 U.S. 298 (1921), where consent was

procured by misrepresentation, and Johnson v. United States, 333 U.S. 10

(1948), where entry “was granted in submission to authority,” id. at 13,

have been viewed as extreme cases. United States v. Mitchell, 322 U.S. 65

(1944), considers only the effect of the McNabb rule on consent to search.

McDonald v. United States, 335 U.S. 451 (1948), does not distinctly ad

dress the question of voluntariness of consent. The Amos ease is discussed

at p. 31, infra.

26

Worse still, the Court’s most extended discussion of the

consent principle came in the “public documents” cases,

Davis v. United States, 328 U.S. 582 (1946), and Zap v.

United States, 328 U.S. 624 (1946); and notwithstanding

the admonition that “Where officers seek to inspect public

documents at the place of business where they are required

to be kept, permissible limits of persuasion are not so

narrow as where private papers are sought,” 16 the courts

of appeals have relied on Davis and Zap in sustaining

searches for entirely private items.16 17 The circuit court

below thus erroneously relied on Davis. (C.A. 20.) Peti

tioner respectfully submits the question is ripe for renewed

consideration by the Court.

(3) Similarly, the question under what circumstances,

if any, consent to search given by one cotenant can affect