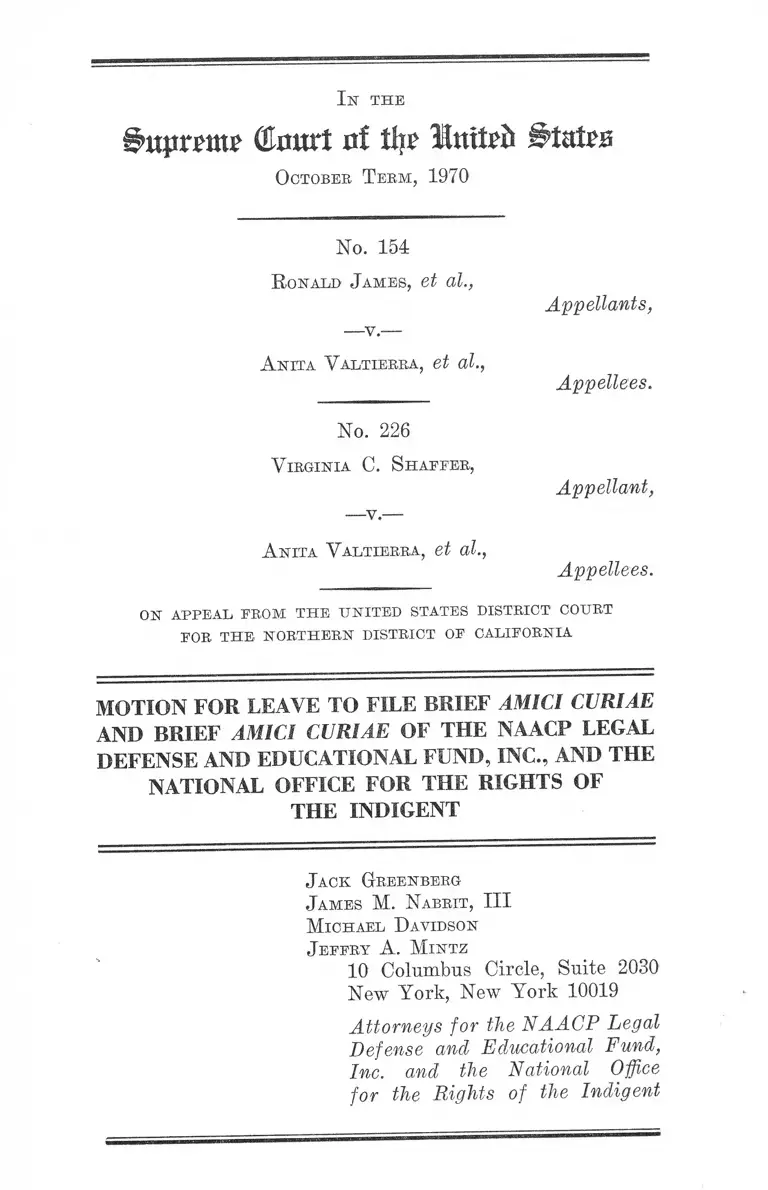

James v. Valtierra Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. James v. Valtierra Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and Brief Amici Curiae, 1970. 4fa4de1c-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8bccccd5-bf08-4c8d-9943-df3b7d0be345/james-v-valtierra-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amici-curiae-and-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

^ttptptttr Court rtf tl|r Unttrfr #tutrB

October T erm , 1970

No. 154

R onald J ames, et al.,

Appellants,

—v.—

A nita V altierea , et al.,

Appellees.

No. 226

V irginia C. S h a ffer ,

—v.—

A nita V altierra, et al.,

Appellant,

Appellees.

O N A P P E A L FR O M T H E U N IT E D STA TES D IS T R IC T COU RT

FO R T H E N O R T H E R N D IS T R IC T O F C A L IFO R N IA

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

AND BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AND THE

NATIONAL OFFICE FOR THE RIGHTS OF

THE INDIGENT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, I I I

M ichael D avidson

J effry A . M in tz

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. and the National Office

for the Rights of the Indigent

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and State

ment of Interest of the A m ici.....................................1-M

Brief Amici Curiae........................ 1

Statement ........................................................................ 1

Summary of Argument..................... 4

A rgum ent

I. Article 34 Enshrines in California’s Constitution

a Discrimination Based on Poverty In Violation

of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment ........................................................... 8

A. Article 34 Is .Repugnant to the Equal Protec

tion Clause Because It Imposes a Special

Burden on the Poor That Is Not Rationally

Related to Any Legitimate Governmental Ob

jective ............................................................... 8

B. Even If There May Be Some Rational Justi

fication For Article 34, This Justification Does

Not Rise to the Level of a Compelling State

Interest in the Measure. Absent Such an In

terest, Article 34 Is Constitutionally Defective

Under the Equal Protection Clause ............... 15

II. Article 34 Establishes an Official Racial Classifi

cation Which Is Arbitrary, Invidious, Discrim

inatory, and Violative of the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment ................ 21

A. The Scheme of Article 34 Sets up an Official

Classification Which Unequally Affects Dif

ferent Racial Groups ....................................... 21

PAGE

11

B. The Unequal Burden of Article 34 Is But One

Aspect of a Pervasive Pattern of Racial Dis

crimination. This Pattern Perpetuates Resi

dential Segregation and Discriminatorily De

nies to Minorities a Wide Range of Oppor

tunities ...................... ....................................... 26

C. The Racial Classification Inherent in Article

34 Cannot Be Constitutionally Justified. It

Should Be Declared Invalid Under Appropri

ate Equal Protection Standards ................... 31

III. By Effectively Denying to Negroes Access to

Housing Equal to That Available to White Per

sons, Article 34 Imposes on Negroes a Badge

and Incident of Slavery, and Constitutes A De

nial of the Equal Rights to Purchase, Lease and

Hold Real Property, Mandated by 42 U.S.C.

§1982 ...................................................................... 33

C o n c lu sio n .................................................................. 36

T able of A u t h o r it ie s

Cases:

Alexander v. Holmes, 39 U.S. 19 (1969) ......................... 30

Arrington v. City of Fairfield, 414 F.2d 687 (5th Cir.

1969) ............................................................................ 18

Arrington v. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Au

thority, 306 P. Supp. 1355 (D. Mass. 1969) .............. 30

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ..... 19

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) ..................... 17

PAGE

I l l

Carrington v. Bash, 380 U.S. 89 (1965) ......................... 13

Cipriano v. City of Houma, 395 U.S. 701 (1969) .......... 30

City of Redondo Beach v. Taxpayers, Property Owners,

etc., City of Redondo Beach, 54 Cal.2d 126, 325 P.2d

170 (1960) .................................................................. 11

Dandridge v. Williams, 397 U.S. 471 (1970) ................. 17

Edwards v. California, 314 U.S. 160 (1941) ................. 19

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 296 P. Supp.

907 (N.D. 111. 1969) ......................................... .........18, 28

Gomillion v. Ligthtfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) _______ 19, 30

Green v. New Kent County School Board, 391 U.S. 430

(1968) ....................................................................... 30

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) .................. .......... 15

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 420 F.2d 1225 (4th Cir.

1970), cert, granted 399 U.S. 926 (1970) ....... .......... 30

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915) ................. 30

Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 383 U.S.

663 (1966) .................................................. 5,13,15,16,30

Hicks v. Weaver, 302 F. Supp. 619 (E.D. La. 1969) .... 28

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 P. Supp. 401 (D.D.C. 1967),

aff’d sub nom. Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 179 (D.C.

Cir. 1969) ............................................ ............ .........19, 25

Holmes v. Leadbetter, 294 P. Supp. 991 (E.D. Mich.

1968) ..............................................................-.... -....... 18

Housing Authority v. Superior Court, 35 Cal.2d 550,

219 P.2d 457 (1950) ....................................................2,12

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) ..........9,10,17, 21,

23, 28, 31, 32

In Re Appeal of Girsh, ----- Pa. ----- , 263 A.2d 395

(1970)

PAGE

17

IV

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) ..7, 17, 28,

33, 34, 35

Kennedy Park Homes Assn. v. City of Lackaivanna,

----- F. Supp. ----- (W.D.N.Y, Aug. 13, 1970) (ex

pedited appeal pending, No. 35320, 2nd Cir.) .......... 18, 28

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Cory.,----- F.2d------ (5th

Cir. No. 28167, July 13, 1970) .................................... 28

Lindsley v. National Carbonic Gas Co., 220 IT.S. 61

(1911) .......................................................................... 15

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969) .............. 30

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) .......... 30

Liucas v. Colorado General Assembly, 377 U.S. 713

(1964) .......................................................................... 32

McDonald v. Board of Elections, 394 U.S. 802 (1969) .... 15

McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 (1961) ................. 15

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) ..............14, 31

Mulkey v. Reitman, 50 Cal. Rptr. 881, 413 P.2d 825

(1966) .......................................................................... 23

Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, 395

F.2d 920 (2nd Cir. 1968) ....................................14,17, 28

Otey v. Common Council of Milwaukee, 281 F. Supp.

264 (E.D. Wise. 1968) ................................................. 18

Powelton Civic Home Owners Assn. v. HUD, 284

F. Supp. 804 (E.D. Pa. 1968) ...................................... 18

Quarles v. Philip Morris, 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Va.

1968)

PAGE

30

V

Ranjel v. City of Lansing, 293 F. Supp. 301 (W.D.

Mich. 1968), rev’d Ranjel v. City of Lansing, 417

F.2d 321 (6th Cir. 1969), cert. den. 397 U.S. 980

PAGE

(1970) ......................................... ......................... 18,25,29

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) .......... 12,17, 22, 28

Rinaldi v. Yeager, 384 U.S. 305 (1969) ......................... 13

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) ....15,16,19, 20, 32

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) .......................... 17

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942) ..................... 13

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966) .... 30

Southern Alameda Spanish Speaking Organization v.

City of Union City, 424 F.2d 291 (9th Cir. 1970) ...16,18,

25, 29

Spaulding v. Blair, 402 F.2d 862 (4th Cir, 1968) .......... 29

Triangle Improvement Council v. Ritchie,----F.2d-----

(4th Cir. No. 14033, May 14, 1970, reh. denied July

14, 1970), pet. for cert, pending, O.T. 1970 No. 712 .... 14

Valtierra v. Housing Authority of the City of San Jose,

313 F. Supp. 1 (N.D. Cal. 1970) ................................ 3

Westbrook v. Mihaly, 2 C.3d 765, 471 P.2d 487 (1970) 11

Western Addition Community Organisation v. Weaver,

294 F. Supp. 433 (N.D. Cal. 1968) ............................ 18

Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23 (1968) ......................... 16

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 357 (1886) ..................... 22

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions:

Calif. Const. Art. 4 §1 ............ 11

Calif. Const. Art. 11 §18 ...... ............. ..................... ....11,12

Calif. Const. Art. 34...................................................passim

VI

12 U.S.C. §1701 (t) ....

23 U.S.C. §§101 et seq

42 U.S.C. §1401 ........

42 U.S.C. §1409 ........

42 U.S.C. §1441 ........

42 U.S.C. §1973 ....... .

42 U.S.C. §1982 ....... .

Other Authorities:

Black, The Supreme Court 1966 Term, Foreward:

“State Action,” Equal Protection, and California’s

PAGE

Proposition 14, 81 H arv. L. R ev . 69 (1967) ..............10,12

B u il d in g t h e A m er ic a n C it y , R epo r t oe t h e N a

tio n a l C o m m issio n on U rban P roblem s (D ouglas

C o m m is s io n ) (1968) ..................................... 3-M, 9,19, 25

R eport of t h e N a tio n a l A dvisory C o m m issio n on C iv il

D isorders ( K e e n e r C o m m .) (Bantam Ed. 1968) ...... 3-M,

19, 25, 26

R epo rt on H o u sin g in Ca l ifo r n ia , Governor’s Advisory

Commission on Housing in California (1963) .......... 10

Sager, Tight Little Islands: Exclusionary Zoning,

Equal Protection, and the Indigent, 21 S t a n . L. R ev .

767 (1968) ............................... , ................................... 28

Proposed Amendments to Constitution, Propositions

and Proposed Laws, Together with Arguments (to

be submitted to the Electors of the State of California

at the General Election Tuesday, November 3, 1964) 23

........... 18

.......... 13

.........18, 34

............. 12

.........18, 34

........... 30

.7, 33, 34, 35

I n t h e

^upratte (Emtrt of %

October T erm , 1970

No. 154

R onald J a m es , et al.,

A n ita V altierra , et al.,

No. 226

V ir g in ia C. S h a f f e r ,

— v .—

Appellants,

Appellees.

Appellant,

A n ita V altierra , et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

AND STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF THE AMICI

Movants NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., and the National Office for the Rights of the Indigent

respectfully move the Court for permission to file the

attached brief amici curiae, for the following reasons. The

reasons assigned also disclose the interest of the amici.

(1) Movant NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., is a non-profit corporation, incorporated un

der the laws of the State of New York in 1939. It was

formed to assist Negroes to secure their constitutional

1-M

2-M

rights by the prosecution of lawsuits. Its charter declares

that its purposes include rendering legal aid gratuitously

to Negroes suffering injustice by reason of race who are

unable, on account of poverty, to employ legal counsel on

their own behalf. The charter was approved by a New

York court, authorizing the organization to serve as a

legal aid society. The NAACP Legal Defense and Edu

cational Fund, Inc. (LDF), is independent of other organ

izations and is supported by contributions from the public.

For many years its attorneys have represented parties in

this Court and the lower courts, and it has participated

as amicus curiae in this Court and other courts, in cases

involving many facets of the law.

(2) A central purpose of the Fund is the legal eradica

tion of practices in our society that bear with discrimina

tory harshness upon Negroes and upon the poor, deprived,

and friendless, who too often are Negroes. In order more

effectively to achieve this purpose, the LDF in 1965 estab

lished as a separate corporation movant National Office

for the Eights of the Indigent (NORI). This organization,

whose income is provided initially by a grant from the

Ford Foundation, has among its objectives the provision

of legal representation to the poor in individual cases and

the presentation to appellate courts of arguments for

changes and developments in legal doctrine which unjustly

affect the poor. Thus NORI is engaging in legal research

and litigation (by providing counsel for parties, as amicus

curiae, or co-counsel with legal aid organizations) in cases

in which rules of law may be established or interpreted

to provide greater protection for the indigent.

(3) In carrying out this program to establish the legal

rights of Negroes and of the poor, LDF and NORI attor

neys have handled numerous cases involving public and

private housing, particularly ones challenging the denial

of housing opportunities to those groups as a result of both

3-M

private and public discriminatory conduct. E.g., Thorpe v.

Housing Authority, 386 U.S. 670 (public housing); Wil

liams v. Schaffer, 385 U.S. 1037 (summary eviction of indi

gent tenant); Triangle Improvement Council v. Ritchie,

----- F.2d ------ (4th Cir. No. 14033, May 14, 1970, reh.

denied, July 14, 1970) pet. for cert, pending, O.T. 1970, No.

712 (displacement of poor blacks by federally assisted high

way) ; Ranjel v. City of Lansing, 417 F.2d 321 (6th Cir.

1969), cert, denied, 25 L.Ed.2d 390 (referendum denying

zoning change to permit low cost housing); Arrington v.

City of Fairfield, 414 F.2d 687 (5th Cir. 1969) (displace

ment of poor blacks by publicly aided construction); Ken

nedy Park Homes Association v. City of Lackaivanna, ——

F. Supp. ----- (W.D.N.Y. August 13, 1970), appeal pend

ing, No. 35320, 2d Cir. (refusal by city to permit develop

ment of low cost, black owned subdivision); Western Ad

dition Community Organization v. Weaver, 294 F. Supp.

433 (N.D. Cal. 1968) (Urban renewal).

(4) It has become increasingly clear in recent years, if

it was not so before, that the denial of opportunities for

decent housing to the poor and particularly to members

of minority groups is a major contributing factor to social

unrest, see R epo rt op t h e N atio n a l A dvisory C o m m issio n

on C iv il D isorders ( K e r n e r C o m m issio n ) 266-274; 467-482

(Bantam Ed. 1968), and that it has a multiplier effect in

restricting the availability of educational, employment and

other opportunities. It is likewise manifest that the pri

vate sector of the economy is unable to meet the needs of

the poor for housing, and that the public sector has woe

fully failed to meet even the goals set in legislation. 42

U.S.C. §§1401, 1441; 12 U.S.C. §1701 ( t ) ; B u il d in g t h e

A m er ic a n C it y , R eport of t h e N atio n a l C o m m issio n on

U rban P ro blem s (D ouglas C o m m is s io n ) , passim. Part of

the reason for this failure is found in local requirements,

such as the provision of the California Constitution chal

4-M

lenged in this case, which set up harriers to the construc

tion of low cost housing. Perhaps reflecting “the self-

righteous opposition often expressed toward subsidized

housing for the poor,” id. at 66, these requirements place

burdens on the efforts of the poor to obtain decent housing

which do not exist for those who are able to afford the cost

of private housing. Article 34 of the California Constitu

tion is particularly onerous, and has contributed to the

fact that California has a much lower per capita avail-

abilty of public housing than other comparable states.

(5) The amici believe that the attached brief will assist

the Court by placing the California provision at issue here

in a national perspective. We submit that it helps demon

strate that restrictions such as this have a racially dis

criminatory effect, which works to undo much of what this

Court and the Congress have done to guarantee equal

rights and equal opportunity.

(6) The individual appellees and the appellee Housing

Authority of San Jose have consented to the filing of this

brief amici curiae. This motion is filed because counsel for

each of the appellants has refused consent.

W h e r e f o r e , movants pray that the attached brief amici

curiae be permitted to be filed with the Court.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reen berg

J am es M . N abrit , III

M ic h a e l D avidson

J e f f r y A. M in t z

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. and the National Office

for the Rights of the Indigent

In t h e

( t a r t n f t l j r l m t r i » :

O ctober T e r m , 1970

No. 154

R onald J a m es , et al.,

Appellants,

A n ita V altierra , et al.,

Appellees.

No. 226

V ir g in ia C. S h a f f e r ,

— v.—

Appellant,

A n ita V altierra , et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AND THE NATIONAL OFFICE FOR THE

RIGHTS OF THE INDIGENT

Statement

This action challenges the validity, under federal con

stitutional standards, of Article 34 of the Constitution of

2

the State of California.1 That provision requires that be

fore any low rent housing- project can be built in any

municipality, the project must be approved by the voters

of the “city, town or county” at a general or special elec

tion, specifically defining “low rent housing project” as one

“financed in whole or in part” by federal or state subsidies,

and further defining “persons of low income,” those to be

served by such projects, as those who, as determined by

public housing authority standards, “lack the amount of

income which is necessary . . . to enable them, without

financial assistance, to live in decent, safe and sanitary

dwellings, without overcrowding.” It became a part of the

state constitution in 1950, as a result of a state-wide ref

erendum, purportedly in response to the decision of the

California Supreme Court in Housing Authority v. Supe

rior Court, 35 Cal.2d 550, 219 P.2d 457 (1950), which held

that decisions by a local housing authority to build public

low-rent housing were administrative and not legislative de

cisions, and thus not subject to review by subsequent refer

endum, as, for example, would be an enactment by a city

council.2

Two separate actions were filed in the district court—one

by residents of the city of San Jose against the housing

authority3 and city council of that city,4 as well as the

1 The full text of Article 34 appears at pp. 2-4 of the brief of

appellant Shaffer in No. 226, and at pp. 7-9 of the brief of appel

lants James, et al., in No. 154.

2 As discussed in Part I of the argument, infra, Article 34 over

shoots the possible need of filling the referendum gap created by

that decision, in that it requires a prior referendum, rather than

simply authorizing a subsequent one.

3 The Housing Authority of San Jose has not appealed and ap

pears in this Court as an appellee. It has filed a brief in support

of the individual appellees, challenging the validity of Article 34.

4 The Mayor and all but one member of the City Council of San

Jose appear as appellants in No. 154. One member of the Council,

Virginia C. Shaffer, is separately represented, and is the appellant

in No. 226.

3

United States Department of Housing and Urban Develop

ment,5 6 and one by residents of San Mateo County against

the housing authority of that County.6 The two cases were

consolidated for all purposes by the district court, and are

therefore joined in this appeal. The plaintiff-appellees are

all poor persons who live in deteriorated housing in the

two municipalities, and with few exceptions, they have been

certified by the respective housing authorities as eligible

for public housing. As a result of the shortage of public

housing, which they contend is in large measure a result

of the operation of Article 34,7 they have not been placed

in such housing.8

Ruling on motions for summary judgment filed by the

plaintiffs in both actions, the three-judge district court

held that Article 34 is invalid as a denial of equal protec

tion, in that it constitutes an impermissible classification

on the basis of wealth and further that, since the “low-

income projects . . . will be predominantly occupied by

Negroes or other minority groups” (App. p. 174), “the

law’s impact falls on minorities” (App. p. 175), creating a

classification on the basis of race. Valtierra v. Bousing

Authority of the City of San Jose, 313 F. Supp. 1 (N.D.

Cal. 1970) (App. pp. 168-179). This appeal, under 28 U.S.C.

§1253, followed.

5 The federal defendants were dismissed on their motion by the

district court. App. pp. 171-2. That action is not questioned in

this appeal.

6 The San Mateo defendants chose to stand mute in the district

court and do not appear in this appeal.

7 In both areas, recent public housing proposals have been de

feated in the referenda required by Article 34. App. pp. 28-29

(San Jose) ; App. pp. 118-121 (San Mateo).

8 The affidavits of the plaintiffs, describing their present circum

stance and their efforts to obtain public or other decent housing

appear at App. pp. 14-20 (San Jose) and App. pp. 104-110 (San

Mateo).

4

Summary of Argument

I

A. Article 34 on its face creates a classification on the

basis of wealth. It requires the approval of the voters in

a prior referendum before any subsidized housing for “per

sons of low income” can be built, but creates no such bar

rier to the housing needs of persons whose income enables

them to purchase housing in the private market. More

over, no other provision of California law imposes a simi

lar obstacle on other than persons of low income, although

various types of financial assistance are provided to as

sist the more affluent to obtain housing.

Article 34 serves no legitimate state interest. Assuming,

arguendo, that the residents of a municipality have an

interest in reviewing decisions which affect the develop

ment of their community, this interest could be satisfied

by providing for subsequent referendum review of deci

sions to build public housing, initiated, when desired, by

the opponents of the project, rather than prior referendum

approval, which must be initiated in every case by its

proponents. This would place public housing on a par

with, for example, zoning changes which may benefit pri

vate housing for the wealthy, and which is subject to such

review. Similarly, the state policy in favor of referenda

and local democracy would be satisfied by providing for

the possibility of subsequent review by the voters of pub

lic housing decisions.

The state policy requiring prior approval of legislative

decisions which incur major long-term indebtedness is not

relevant to public housing, as substantially all of the capi

tal costs are met by federal subsidies. Article 34 also re

sults in an impermissible distinction between federally

subsidized public housing which benefits the poor and

5

housing assistance provided to the more wealthy, as well

as other public projects which receive substantial federal

assistance, such as highways, and which are not burdened

even with the availability of subsequent popular review.

B. Even if there were some legitimate state interest

served by Article 34, it is not a “compelling state interest”

such as is required to justify a classification on the basis

of wealth. This Court has held that “lines drawn on the

basis of wealth or property . . . are traditionally dis

favored.” Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections,

383 U.S. 663, 668 (1966). Where such classifications are

found, a higher standard of justification is required than

where typical, non-discriminatory state economic regula

tions are involved. Housing is a matter of vital importance

to all and particularly to those who lack the income to

obtain it in the private market. A burden placed on the

availability of decent housing to the poor results in the

deprivation of other fundamental rights, and thus has an

effect beyond its immediate impact. No “compelling state

interest” supports the burden on the poor which Article 34

creates.

II

A. While Article 34 on its face creates a classification

only on the basis of wealth, it is well established that courts

may look beyond to the actual effect of a challenged provi

sion to determine its ultimate effect. The fact that an

enactment is racially neutral does not bar a determination

that its impact falls on minorities. The history of Article

34 strongly suggests a racially discriminatory motivation

for its enactment. However, even in the absence of such

motivation, the effect remains a relevant area of inquiry.

The record in this case demonstrates, and the opinion

below, in harmony with decisions in similar cases, holds

6

that an enactment which discriminates against the poor

has an inordinate impact on racial minorities, in this con

text, blacks and Mexican-Americans, because of the strong

correlation between minority group status and poverty.

B. The racially discriminatory effect of Article 34 re

inforces other discriminatory devices and serves to perpetu

ate segregation. It is particularly severe, because the denial

of housing opportunities effectively restricts minority

group members from access to other opportunities. Ar

ticle 34 is an example of numerous public and private

devices which promote discrimination in housing. The ref

erendum procedure, highly desirable in most circumstances

in a democracy, has frequently been misused for such pur

poses. In areas other than housing, subtle, facially neutral

devices have been used commonly to discriminate against

racial minorities, but have been invalidated by the courts.

A like analysis applied to this case will reveal, as it did to

the lower court, that Article 34 is discriminatory.

C. Since it has an inordinate impact on racial minorities,

Article 34 is inherently suspect, and must overcome an

extremely heavy burden of justification. No such showing

exists here, for the reasons discussed in Part I, supra. Ad

ditionally, the fact that Article 34 was originally adopted by

a state-wide majority vote and requires in its operation

a decision by a local majority is irrelevant to its validity,

since the majority may not act to limit the constitutional

rights of minorities. Article 34 denies to racial minorities

equal protection of the laws.

7

Tlie direct effect of Article 34 of placing a special burden

on the access of the poor to decent housing, and the inci

dental effect, resulting from the correlation between race

and poverty, of restricting the availability of housing to

racial minorities has a combined result of denying to many

Negro Americans in California access to housing equal to

that of whites. This result constitutes, as to them, the im

position of a badge or incident of slavery, prohibited by

the Thirteenth Amendment, and constitutes a violation of

the mandate of 42 U.S.C. § 1982, as interpreted by this

Court in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968).

III

8

ARGUMENT

I.

Article 34 Enshrines in California’s Constitution a

Discrimination Based on Poverty In Violation of the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Article 34 establishes a formidable obstacle to the con

struction of federally aided public housing within the

means of poor people, in the absence of any analogous

provision with respect to other housing or to other fed

erally aided public benefit programs. In so doing Article 34

operates arbitrarily, irrationally, and invidiously to deny

poor people the equal protection of the laws.

A. Article 34 Is Repugnant to the Equal Protection

Clause Because It Im poses a Special Burden on the

Poor That Is Not Rationally Related to Any Legiti

m ate Governm ental Objective.

According to its own terms, Article 34 applies exclu

sively to low rent housing projects. It defines a low rent

housing project as “any development composed of urban

or rural dwellings, apartments, or other living accommoda

tions for persons of low income”, Calif. Const. Art. 34 §1

(emphasis added). By further definition, these are persons

who “lack the amount of income which is necessary . . . to

enable them, without financial assistance, to live in decent,

safe, and sanitary dwellings, without overcrowding.” Ibid.

This language is explicit: it singles out for special gov

ernmental treatment only such housing as would benefit

persons unable to provide adequate housing for themselves

without public assistance.

On its face Article 34 openly differentiates between the

poor and all other people. The impact of a restrictive

classification falls on those who would benefit from the

9

programs hampered, cf. Hunter v. Erickson, 393 TT.S. 385,

391 (1969). In this ease low income persons stand pri

marily to benefit. "Wealthy persons need little or no assist

ance in finding housing. Cf. Hunter v. Erickson, supra at

391, where this Court noted, “the majority needs no

protection against discrimination.” As appellant Shaffer

somewhat misleadingly notes, “Directing legislation as to

the problem of poverty is not classification on the basis of

poverty.” Brief of Appellant Shaffer in No. 226 at 44.

But Article 34 is not a legislative enactment to deal with

“the problem of poverty.” It erects a barrier against leg

islative programs that provide for the housing needs of

the poor.

The fact that California has, with limited exceptions, not

yet chosen to provide public assistance for any housing

other than low income housing9 is irrelevant. California

9 Even this analysis ignores the participation of Californians in

federally-financed programs to assist moderate-income housing in

the form of private homes, such as the Federal Housing Adminis

tration (FHA), Veteran’s Administration (VA), and Federal Na

tional Mortgage Association (FNMA) programs.

Such programs have been of major importance in increasing the

housing supply available to moderate and upper income groups.

See, e.g., Building the Amebican Citt , Report op the National

Commission on Urban P roblems (T he Douglas Commission), at

66 (1968) :

The Nation has made a phenomenal record over the last two

decades in building housing for the middle and affluent classes

. . . Government policy has provided significant incentives

and help through mortgage guarantees, secondary credit facil

ities, and Federal income tax deductions for interest payments

and local property taxes. . . .

The extent to which Government policy has subsidized the

private homeowner is not generally recognized or acknowl

edged. . . . This generous but generally unacknowledged Fed

eral subsidy to the affluent or middle-class homeowner needs

to be emphasized in view of the self-righteous opposition often

expressed toward subsidized housing for the poor. . . .

In contrast to its truly amazing record in housing construc

tion for the upper half of America’s income groups, the Na

tion has made an inexcusably inadequate record in building

1 0

could legislatively decide to provide such assistance, with

out encountering any constitutional restrictions on its

actions like those encumbering low income housing. The

discrimination lies in the establishment of two different

legislative processes: one, more arduous, for measures

that would particularly benefit a disfavored minority

group; and the other, more routine, for measures of bene

fit to the majority. Cf. Hunter v. Erickson, supra at 390 ;

Black, The Supreme Court 1966 Term, Foreward: “State

A ctionE qua l Protection, and California’s Proposition 14,

81 H arv. L. R ev . 69, 75-76 (1 9 6 7 ). Article 34 offends pre

cisely because it singles out the poor with the effect and

for the apparent purpose of reducing the already limited

housing opportunities available to them. Article 34 lends

the weight of constitutional restriction to all the other

forces and handicaps that the poor must contend with in

their efforts to achieve the minimum of human dignity.

We submit that the District Court below properly held

Article 34 an “unequal imposition of burdens upon groups

that are not rationally differentiable in light of any legiti

mate state legislative objective.” Appendix, p. 173. An

examination of the interests and objectives asserted by

appellants should lead this Court to agree that the dis

crimination embodied in Article 34 is not rationally re

lated to any of these interests.

Appellants contend in justification of Article 34 that it

merely reasserts California’s strong policy in favor of

referenda and local democracy. This contention distorts

or upgrading housing for the poor to provide them with decent,

standard housing at rents they can afford, [footnote omitted.]

Moderate and upper-income Californians participate in these

programs on a vast scale. See Repoet on H ousing in California,

Governor’s Advisory Commission on Housing in California (1963),

especially the Appendix. California has imposed no legislative

restrictions of any kind on participation in these federal programs.

1 1

both the substance of California’s referendum policy and

the nature of Article 34, as a brief description of the

Article’s history will indicate. California’s general con

stitutional reservation of referendum powers to the people

secures the popular option “to so adopt or reject any Act,

or section or part of any Act, passed by the Legislature,”

and extends to local review of local legislative actions.

Calif. Const. Art. 4 § 1. Nothing in this language requires

or permits the imposition of a prior referendum require

ment. I t simply reserves to the people the power to ap

prove, alter, or amend legislative actions already taken.

With particular reference to local bond issues, appellants

also assert that California policy requires prior approval

of any local action incurring indebtedness, Brief of Appel

lant Shaffer in No. 226 at 33-34. This constitutional policy

is allegedly embodied in Calif. Const Art 11 § 18, providing

that no locality shall incur indebtedness or liability in

excess of its annual revenue without voter approval Yet

as the extensive discussion of Art 11 § 18 in Westbrook v.

Mihaly, 2 Cal. 3d 765, 471 P.2d 487 (1970) indicates, this

restriction is meant to apply only to actions requiring the

locality itself to make expenditures and assume bonded

debt.10 It should not apply to programs under the Federal

Housing Acts of 1937 and 1949, because there the federal

agency guarantees and assumes the costs of housing

10 Section 18 establishes “pay as you go” as “a cardinal rule of

municipal finance,” applicable to “projects necessitating long-term

expenditures,” Westbrook v. Mihaly, supra at 776-77, 471 P. 2d at

494. One case interpreting the purpose of the section found that

it was to avoid a situation “whereby the holders of an issue of

bonds could . . . force an uneonsented-to increase in the taxes of,

or foreclosure on the general assets and property of the issuing

public corporation.” City of Redondo Beach v. Taxpayers, Prop

erty Owners, etc., City of Redondo Beach, 54 Cal. 2d 126, 131, 325

P. 2d 170 (I960); Westbrook v. Mihaly, supra at 777 n. 16, 471

P. 2d at 494 n. 16.

1 2

development.11 Under these programs the municipality is

merely an intermediary between the funding agency and

the bondholders. The programs involve no current expen

ditures or affirmative financial obligations for the munici

pality. They are in effect federal and state projects

administered locally.

For this reason, the California Supreme Court in

Housing Authority v. Superior Court, 35 Cal. 2d 550, 219

P.2d 457 (1950) held that such local housing authorities’

acts were “executive and administrative” rather than

“legislative,” and therefore not subject to the referendum

provisions of the California Constitution. Id. at 461, 462.

Article 34 was enacted shortly after this decision, evidently

in response to it. Appellant Shaffer now contends that

Article 34 does no more than close the “loophole” left by

the Housing Authority decision, Brief of Appellant Shaffer

in No. 226 at 18, 33-34. This argument is unpersuasive

on two grounds. First, there was in fact no “loophole,”

since as shoAvn above the Art. 11 §18 prior referendum

requirement was never intended to apply to this situation.

Article 34 was in fact a substantially new enactment.

Second, even if any loophole had existed, Article 34 does

much more than “close the loophole” left by the decision.

The Housing Authority case could have been overruled,

had that been the sole object, by an amendment permitting

subsequent referendum review of decisions to build low

rent housing. But Article 34 went beyond such overruling

of the decision to impose an additional requirement Cf.

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369, 376-377 (1967); Black,

The Supreme Court 1966 Term, Foreivard: “State Action,”

11 The Federal government guarantees all such bonds issued and

reimburses the local authority for payments on principal and

interest. 42 U.S.C. §1409. There can thus be no possibility of

impairment of the municipality’s fiscal integrity by these bonds.

13

Equal Protection, and California’s Proposition 14, supra,

at 77. Article 34 requires the so called full measure of

“local democracy” only for approval of the projects which

affect the housing aspirations of the poor. Whereas a

subsequent referendum requirement might arguably bring

decisions to build public low rent housing into procedural

conformity with all other legislative programs, the prior

referendum requirement singles out programs which benefit

the poor. Such a classification on grounds of poverty is

irrational because poverty is unrelated to the objective of

democracy, Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections,

383 U.S. 663 (1966), and therefore violates the Equal

Protection Clause, Rinaldi v. Yeager, 384 U.S. 305, 309

(1966); Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535, 542 (1942);

Carrington v. Rash, 380 U.S. 89, 96 (1965).

Even if low cost housing projects did involve local

expenditures (and therefore arguably fall within the scope

of the California policy favoring prior referenda on long

term fiscal undertakings), Article 34 would be offensive to

equal protection principles. Only low income housing is

subject to its requirement. No similar burden is placed

on other state legislative actions assisted by federal funds

even where such projects, like low income housing, take

property off local tax rolls.12 As the Court below stated,

The vice in this case is that Article XXXIV makes

it more difficult for state agencies acting on behalf

of the poor and the minorities to get federal assistance

12 Appellant Shaffer professes not to see the “likeness in any

rational aspect” between such projects and low-income housing.

Brief of Appellant Shaffer in No. 226 at 46. Yet, to take but one

example, federally-funded highway construction under the Federal-

Aid Highway Act of 1956, as Amended, 23 IJ.S.C. §§101 et seq.,

also takes large tracts of local land off tax rolls and may impose

heavy future obligations on the municipality by encouraging new

residential, industrial, and commercial developments requiring util

ity improvements and municipal services.

14

for housing than for state agencies acting on behalf

of other groups to receive financial federal assis

tance. . . . Some common examples, inter alia,, are:

highways, urban renewal, hospitals, colleges and uni

versities, secondary schools, law enforcement assis

tance, and model cities. (Appendix p. 177.)

It is irrational and impermissible to limit the application

of the policy to low income housing, while all other projects

which might involve similar local fiscal obligations are not

so disfavored. A valid classification must be reasonable

in light of its purpose, McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184,

191 (1964). This classification is eminently unreasonable

and hence repugnant to the Equal Protection Clause.

The analogy between housing projects and the other

federally assisted projects just mentioned also serves to

discredit the “non-fiscal” justifications of the prior refer

endum requirement. These purported justifications are

“sociological,” “psychological,” and aesthetic, see Brief

of Appellant Shaffer in No. 226 at 19, 36-38. Yet highways,

schools and renewal projects, like low income housing,

involve displacement and relocation, affect housing pat

terns, and have substantial social consequences for the

locality.13 Nevertheless these programs are not equally sub

ject to prior referendum approval. It would appear that the

principal support for Article 34 derives less from concern

for the sociological aspects of urban development, than

from unwillingness to allow low rent housing residents

into the locality.

We do not here contend that any referendum provisions,

as for example the possibility of subsequent popular dis

13 Cf. Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, 395

P. 2d 920 (2nd Cir. 1968); Triangle Improvement Council v.

Ritchie,----- - P. 2 d ----- (4th Cir. No. 14033, May 14, 1970, reh.

denied July 14, 1970), pet. for cert, pending, O.T. 1970 No. 712.

15

approval, is necessarily invalid. We do not attack “demo

cracy” but only the discriminatory application of the

referendum requirement. We submit that the poverty-

based discrimination of Article 34 must be struck down

as an arbitrary and invidious classification lacking any

rational relationship to legitimate governmental ends.

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969); Harper v.

Virginia State Board of Elections, supra; Griffin v. Illinois,

351 U.S. 12 (1956).

B. Even If There May Be Som e Rational Justification

For Article 34, This Justification Does Not Rise to

the Level of a Com pelling State Interest in the

Measure. Absent Such an Interest, Article 34 Is

Constitutionally Defective Under the Equal P ro

tection Clause.

Even if there were some rational relationship between

Article 34’s classification and a proper governmental goal,

the Article would still violate the Equal Protection Clause.

It certainly does not further any “compelling” or “over

riding” state interest. Only such an interest should justify

official wealth-based discriminations.

As this Court has held, “Lines drawn on the basis of

wealth or property, like those of race [citation], are tra

ditionally disfavored,” Harper v. Virginia State Board of

Elections, supra, at 668; McDonald v. Board of Elections,

394 U.S. 802 (1969). Consequently, this Court has in many

instances involving wealth-related classifications declined

to adhere to the equal protection standard traditionally

applied in review of state economic or social regulations,

Lindsley v. National Carbonic Gas Co., 220 U.S. 61 (1911) ;

McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 (1961). It should not

apply any such traditional standard here.

When the discrimination cuts against the welfare of the

poor, a more demanding standard comes into play, par

16

ticularly when an important interest is thereby jeopardized.

Thus, this Court in Harper v. Virginia State Board of

Elections, supra, stated that “where fundamental rights

and liberties are asserted under the Equal Protection

Clause, classifications which might invade or restrain them

must be closely scrutinized and carefully confined,” 383

TT.S. at 670. See also Shapiro v. Thompson, supra, at 633,

638; cf. Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23, 32 (1968). Judi

cial review in such cases requires that the State demon

strate a “compelling interest” in its scheme, for mere

rationality or some conceivable justification will not suffice

to offset the important interest of the individuals adversely

affected by the classification. Shapiro v. Thompson, supra,

at 638.

For example, in Southern Alameda Spanish Speaking

Organisation v. City of Union City, 424 F.2d 291 (9th

Cir. 1970), the court found that the effect of a municipal

zoning referendum was “to deny decent housing and an

integrated environment to low income residents,” 424 F.2d

at 295. Observing that the municipality “may well” have

an affirmative duty to deal with the housing needs of the

poor, the court stated:

Surely, if the environmental benefits of land use

planning are to be enjoyed by a city and the quality

of life of its residents is accordingly to be improved,

the poor cannot be excluded from enjoyment of the

benefits. Given the recognized importance of equal

opportunities in housing, it may well be, as a matter

of law, that it is the responsibility of a city and its

planning officials to see that the city’s plan as initiated

or as it develops accommodates the needs of its low

income families, who usually—if not always—are mem

bers of minority groups. 424 F.2d at 295-296. [foot

notes omitted]

17

The court applied a much more rigorous standard of

scrutiny than the traditional standard urged by appel

lants.14

Appellants’ assertion that the case of Dandridge v.

Williams, 397 U.S. 471 (1970) requires another standard

is not well taken. That case fell squarely within the arena

of economic measures as to which this Court has always

allowed the states great latitude. Dandridge dealt with a

state public welfare assistance program, and in particular

with the “difficult responsibility of allocating limited public

welfare funds among the myriad of potential recipients,”

397 U.S. 471, 25 L, Ed. 2d 491, 503 (1970). Here, the provi

sion challenged does not significantly assist the state in

regulating its finances. Article 34 restricts the development

of housing that would not impose obligatory expenditures

on the state or its subdivisions, but would be substantially

financed by the federal government.15

Housing is a fundamental interest which must be pro

tected from discriminatory state action not firmly grounded

on a complelling state interest. This Court has long shown

concern for the problems confronting those who are handi

capped in their search for decent housing. Buchanan v.

Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917); Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S.

1 (1948); Reitman v. Mulkey, supra; Jones v. Alfred H.

Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968); Hunter v. Erickson,

supra.16 As a result of discriminatory practices and laws

14 Cf. In re Appeal of Girsh, ----- P a .------ ■, 263 A.2d 395 (1970),

holding that a municipal zoning ordinance which made no provi

sion for multiple-dwellings within the town was unconstitutional

as it had the effect of totally excluding those who, for economic

or other reasons, would prefer to live in apartments.

16 See pp. 11-12, supra.

16 Discriminatory deprivation of housing has also in recent years

been the subject matter of a substantial and increasing volume of

litigation before the lower federal courts. See, for example, Nor-

1 8

like Article 34, the housing crisis affects the poor as a

group, as it also affects racial minorities.17

Congress has over a period of years repeatedly declared

its concern for the inability of the poor to find adequate

housing. The Housing Act of 1949 states:

“The Congress declares that the general welfare and

security of the Nation and the health and living stan

dards of its people require . . . governmental assistance

. . . to provide adequate housing for urban and rural

non-farm families with incomes so low that they are not

being decently housed in new or existing housing.” 42

U.S.C. §1441.

In the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968 Con

gress affirms the goal of §1441 but then finds “that this

goal has not been fully realized for many of the Nation’s

lower income families; that this is a matter of grave na

tional concern,” 12 U.S.C. §1701 (t). And by 42 U.S.C.

§1401, first enacted in 1937, “It is declared to be the policy

of the United States . . . to remedy the unsafe and unsani

tary housing conditions and the acute shortage of decent,

safe, and sanitary dwellings for families of low income.”

walk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, 395 F. 2d 920

(2nd Cir., 1968) ; Southern Alameda Spanish Speaking Organiza

tion v. City of Union City, 424 F. 2d 291 (9th Cir. 1970); Ranjel

v. City of Lansing, 417 F. 2d 321 (6th Cir. 1969), cert den., 397

U.S. 980 (1970); Arrington v. City of Fairfield, 414 F. 2d 687

(5th Cir. 1969) ; Powelton Civic Home Owners Assn. v. HUD, 284

F. Supp. 808 (E.D. Pa. 1968) ; Kennedy Park Homes Assn. v.

City of Lackawanna, ----- F. Supp. ------ (W.D.N.Y. Aug. 13,

1970) (expedited appeal pending, No. 35320, 2nd Cir.) ; Cautreaux

v. Chicago Housing Authority, 296 F. Supp. 907 (N.D. 111. 1969) ;

Otey v. Common Council of Milwaukee, 281 F. Supp. 264 (E.D.

Wise. 1968) ; Holmes v. Leadbetter, 294 F. Supp. 991 (E.D. Mich.

1968); Western Addition Community Organization v. Weaver, 294

F. Supp. 433 (N.D. Cal. 1968).

17 The relationship of racial discrimination is more fully dis

cussed in parts II and III of this Argument, infra.

19

Adequate housing within the means of poor people is

also the key to enjoyment of other fundamental rights.

The restriction of public housing programs, particularly

when private low rent housing is disappearing through

destruction, (often by governmental action18) and increas

ing costs,19 excludes low income persons from local electoral

participation, cf. Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 IT.S. 339

(1960), and reduces the right to travel and to locate oneself

freely, Edwards v. California, 314 U.S. 160 (1941), Shapiro

v. Thompson, supra, to a limited right of passage. Freedom

of “in-migration,” including immediate availability of wel

fare support for indigents, is constitutionally protected,

Shapiro v. Thompson, supra, at 631, but this freedom is

hollow indeed where discriminatory local regulations effec

tively prevent indigents from finding housing in areas to

which they wish to migrate. Access to equal educational

opportunities, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483,

493 (1954), depends significantly on residence.20 Access to

housing is also essential to equal job opportunities for low

income workers, particularly as the pattern of job dispersal

into newer areas continues, if they are not to be prevented

from following their jobs and freely competing for new

ones. R eport of t h e N ational A dvisory C ommission on

C ivil D isorders (K eener Com m issio n ) 392-393 (Bantam

Ed. 1968). If the poor are denied housing in the very

is “Furthermore, over the last decades, Government action

through urban renewal, highway programs, demolitions on public

housing sites, code enforcement, and other programs has destroyed

more housing for the poor than government at all levels has built

for them.” B uilding t h e A m erican City , supra, at 67.

19 See, e.g., Affidavit of Franklin Miles Lockfeld, App. pp. 59,

60-61.

20 The discriminatory determination of educational opportunity

by socio-economic patterns was a basis for detailed comment and a

ground for the decision in Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401,

513 (D.D.C. 1967), aff’d sub nom. Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F. 2d 175

(D.C. Cir. 1969).

2 0

areas of most vigorous economic and demographic growth,

such as Santa Clara and San Mateo Counties, they will

remain excluded from the benefits of economic growth.

The State’s justification for its discrimination between

low rent housing and all other housing projects, therefore,

must reflect a “compelling state interest,” Shapiro v. Thomp

son, supra at 634, 638. Where “less drastic means are

available” to assure the governmental objective, “it is un

reasonable to accomplish this objective by the blunderbuss

method.” Id. at 637. As discussed supra21 the State’s inter

est in Article 34 fails even to satisfy criteria of rationality

or plausibility. California could have carried out its policy

favoring referenda without placing a special burden on

the poor, by permitting low income housing projects to

be submitted to subsequent referendum. Instead California

chose to encumber low income housing with the special

onerous requirement of prior referendum approval. As

against the vital constitutional interest in protecting the

poor minority against injury from unequal treatment with

regard to its most important interests, the State’s alleged

justifications for Article 34 merit no greater deference than

was accorded to them by the Court below. The District

Court’s summary dismissal of these justifications was

proper, and its holding that Article 34 violates the Equal

Protection clause was correct.

21 Pp. 10-14.

2 1

II.

Article 34 Establishes an Official Racial Classification

Which Is Arbitrary, Invidious, Discriminatory, and Vio

lative of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Article 34 effectively classifies people on a racial basis

for different governmental treatment, even though the

words of the Article are not explicitly racial. This violates

the right of the racial minority to the equal protection of

the laws.

A. The Scheme of Article 34 Sets up an Official Classi

fication W hich Unequally Affects Different Racial

Groups.

The case at bar closely resembles Hunter v. Erickson,

393 U.S. 385 (1969), in which this Court invalidated an

amendment to the Akron, Ohio, City Charter requiring

prior referendum approval for any local legislative action

relating to discrimination in housing. The present case

is indistinguishable from Hunter but for the fact that by

its terms, the discrimination is based on wealth rather than

on race, religion, or ancestry. However, the racially dis

criminatory effect of Article 34 can be clearly demonstrated

by examining its impact.

This Court in Hunter expressly looked behind the Charter

amendment’s terms to weigh its inevitable effect:

. . . although the law on its face treats Negro and

white, Jew and gentile, in an identical manner, the

reality is that the law’s impact falls on the minority.

The majority needs no protection against discrimina

tion and if it did, a referendum might be bothersome

but no more than that. . . . §137 places special burdens

2 2

on racial minorities within the governmental process.

393 U.S. at 391. (emphasis added)

The court below relied on the quoted passage in finding

that “here, as in the Hunter case, the impact of the law

falls upon minorities.” Appendix pp. 175, 176. Article 34,

like the Hunter measure, is neutral on its face with regard

to race. But here as in the previous case it is principally

one group—the racial minority-—which actually feels the

burden of the measure. Hunter commands the invalidation

of an enactment which has racially discriminatory effects,

without requiring a showing of discriminatory motivation

for the enactment. We submit that this Court should affirm

the District Court’s proper application of that recently an

nounced constitutional mandate.

Neither this Court nor California itself is a stranger to

attempts to cloak discriminatory legislation in superficially

neutral terms. In Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967),

this Court found both discriminatory purpose and effect,

and held the state constitution’s guarantee of the freedom

to sell property invalid as a substantial state involvement

in private discrimination. 387 U.S. at 378. The message of

Reitman is clear: superficially non-discriminatory statu

tory language will be disregarded where the full facts indi

cate that the statute visits hardship on a racial minority.

Cf. Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 357, 374 (1886).

As a California constitutional amendment adopted by

initiative and limiting equal housing opportunities, Propo

sition 10—the electoral version of Article 34—strongly re

sembles Proposition 14, the measure invalidated by this

Court in Reitman. The arguments advanced by official

proponents of Proposition 14 sounded themes of “the right

to sell or rent [the owner’s] property as he chooses”, as

sured by means of a measure that “will require the state

to stay neutral,” and urged the electorate to “vote for free

23

dom.” 22 The California court characterized such arguments

as an invitation to racial discrimination thinly disguised

“by the ingenuity of those who would seek to conceal it

by subtleties and claims of neutrality,” Mulkey v. Reitman,

50 Cal. Eptr. 881, 890, 413 P.2d 825 (1966). The official

arguments in favor of Proposition 10 are strikingly similar.

That measure’s advocates advanced it as “neither for nor

against public housing,” but as a means to “restore to the

citizens . . . the right to decide whether public housing is

needed or wanted,” and invoked the mantle of “the demo

cratic process of government.” Appendix at 50, 51, 52.

Here as in the case of Proposition 14, this Court should

look beyond the proponents’ professed concern for “self-

determination.” The benefits of the alleged “self-deter

mination” and “democratic process” embodied in Article

34 are available only to the majority, at the expense of a

racial minority oppressed thereby.

The inference of discriminatory motivation is not, how

ever, essential to showing that Article 34 sets up an un

constitutional scheme. As the Court below properly held,

“Certainly, Hunter does not demand a showing of improper

motivation.” Appendix p. 177. Once Article 34’s dis

criminatory effect is exposed, Hunter clearly controls and

Article 34 must fall on equal protection grounds. Since

measures designed to benefit the poor are of substantial

and particular importance to racial minorities, obstacles

to the construction of low-income housing particularly

affect these minorities. As a consequence Article 34 detri

mentally affects blacks and Mexican-Americans far more

severely than whites.

22 Proposed Amendments to Constitution, Propositions and Pro

posed Laws, Together With Arguments. (To be submitted to the

Electors of the State of California at the General Election Tuesday,

November 3, 1964.)

24

Article 34 by its terms discriminates on tbe basis of

wealth. The court below found the evidence of the correla

tion between poverty and race so convincing that it entered

summary judgment in part on the ground that wealth-based

discrimination amounted to racial discrimination.23

Beyond the existence of the race-poverty correlation in

Santa Clara and San Mateo Counties lies the pattern,

widely noticed in recent years, of a similar correlation

across the nation. The National Commission on Urban

23 The District Court noted in its Opinion:

“That minority groups comprise “the poor” is increasingly

clear. In his affidavit, Mr. Franklin Lockfeld, Senior Planner

for the Santa Clara County Planning Department stated:

‘The low-income areas are closely related to the areas of con

centration of minority residents and high income areas are

closely related to the nearly all white sections of the commu

nity. . . . In 1960, only 5% of the units occupied by white-

non-Mexican-Americans were in dilapidated or deteriorated

condition, while 23% of the units occupied by Mexican-Ameri

cans and 20% of the units occupied by non-whites were in

dilapidated or deteriorated condition. Minorities were thus

over represented in the less than standard housing by greater

than four to one, and occupied nearly one-third of the de

teriorating and dilapidated housing in the County in I960.’ ”

App. p. 176 n. 2.

See also Affidavit of Dovie Ruth Wylie, Planner with the San

Mateo County Planning Commission, expressing the informed opin

ion that there is a strong relationship between minority racial

status and poverty in San Mateo County. App. p. 147-148. This

view was uncontradicted below.

And see Declaration of Attorney Andrew H. Field, President of

Fair Housing Council in San Mateo County: “ . . . discrimination

in housing in San Mateo County on the basis of race and ethnic

background prevails throughout the housing industry. . . . The

major method by which laws against open discrimination are

evaded is by making most housing in San Mateo County eco

nomically beyond the means of most members of racial minority

groups.” App. p. 132-133.

25

Problems (Douglas Commission) summarized the situation

in blunt terms:

Most important, poverty families in substandard hous

ing have a high correlation with race. If you are poor

and nonwhite and rent, the chances are three out of

four that you live in substandard housing. B uilding

t h e A merican C ity , Report of the National Commis

sion on Urban Problems (1968), p. 10.24 *

Other studies have also concluded that the poor tend to

be members of a racial minority, and vice versa. The

National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Kerner

Commission) traced the same statistical correlations.

R eport oe th e N ational A dvisory Commission on C ivil

D isorders (Bantam Ed. 1968), p. 258. Federal courts have

frequently taken note of this correlation.26 In light of the

wide recognition conferred upon the race-poverty corre

spondence, it would appear undeniable that measures

24 The Commission also notes, “ . . . the incidence of poverty

is much higher among non-whites than among whites. In 1967,

41 per cent of the non-white population was poor, compared with

12% of the white population. Non whites thus constitute a far

larger share of the poverty population (31%) than of the American

population as a whole (12%). Moreover, the non white propor

tion of the poverty population has been increasing, slowly but

steadily.” Id. p. 45.

26 See, e.g., Southern Alameda Spanish Speaking Organization

v. City of TJnion City, 424 F. 2d 291, 296: “ . . . low-income

families, who usually—if not always—are members of minority

groups.”

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401, aff’d sub nom. Smuck v.

Hobson, 408 F. 2d 175: “ . . . for a majority of District schools

and school children race and economics are intertwined: when one

talks of poverty or low income levels one inevitably talks mostly

about the Negro.” 269 F. Supp. at 454.

Banjel v. City of Lansing, 293 F. Supp. 301 (W.D. Mich. 1968),

rev’d on other grounds, 417 F. 2d 231 (6th Cir. 1969), found “a

strong relationship between race and poverty,” 293 F. Supp. at 303.

2 6

burdensome to the poor cut with special cruelty at blacks,

Mexican-Americans, and other minorities. Article 34 is

such a measure. We submit that the findings of the District

Court, which was particularly familiar with these localities,

of a racially discriminatory effect, were wholly proper.

B. The Unequal Burden of Article 34 Is B ut One Aspect

of a Pervasive Pattern of Racial Discrim ination. This

Pattern Perpetuates Residential Segregation and Dis-

crim inatorily Denies to M inorities a W ide Range of

O pportunities.

The racial effects of Article 34 with respect to low rent

housing cannot be adequately considered apart from the

broader patterns of racial discrimination in housing

throughout California and across the nation. Article 34

is yet another example of the numerous ways in which

blacks, Mexican-Americans, and other minority groups are

denied equal opportunities in housing. Considered in this

light, each discriminatory device (whether by design or

otherwise) contributes significantly to the advancing evil

which this lawsuit seeks in small part to redress: a society

presently segregated and becoming ever more so.26 More

specifically, the effect of each discriminatory device for

blacks and other minorities is to limit their mobility, to

restrict their employment, educational and recreational

opportunities, and to increase the cost and decrease the

quality of the housing that remains open to them. Each

discriminatory device reinforces the effectiveness of every

other discriminatory device. Their impact on black and

minority persons is cumulative and devastating.

26 See Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil

D isorders (K erner Commission) (Bantam Ed. 1968), p. 1.

27

The racial prejudices that fueled the Proposition 14

(former Art, 1 §26, Calif. Const.) campaign27 have left a

bitter legacy in California and contributed to the “tax

payers’ revolt” as regards public housing and other pro

jects widely perceived as of special benefit to minorities.

This “revolt” has made prior referendum approval for

any such project extremely difficult to secure. (See Brief

of Appellant Shaffer in No. 226 at 32, n. 20). Although the

open bias exhibited while Proposition 14 was in effect28 has

largely ended, these discriminatory practices have again

became covert. Blacks and other minorities in California

consequently cannot compete on an equal basis for housing

27 See Affidavits in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment,

App. pp. 125-136.

28 See, for example, Affidavit of Elaine Eisenberg, Member of

San Mateo County Human Relations Commission, Appendix pp.

125-126 :

“. . . After Proposition 14 was passed, . . . attempts were made

to find housing for black families.

“Common reactions from realtors and homeowners in the

County was ‘wouldn’t they be happier with their own people,’

‘I will show you where blacks can rent—in black ghetto areas,’

‘I personally have no bias, but my neighbors would object,’

‘my other tenants would move out,’ or flat ‘no’s.’ These dis

criminatory attitudes were and still are widespread through

out the County.

“The emphasis was always on finding houses and apartments

to rent, because minority persons did not have enough money

to buy homes. . . .

“There has been no real change in attitude, even now with

Proposition 14 off the books. . . .

“When Proposition 14 was in effect, I received many threat

ening calls from persons who did not want equal opportunity

in housing, and blacks received flat denials when they at

tempted to find houses; while this overt prejudice is not as

apparent today, the underlying discrimination is. The prac

tices are more subtle, and evasive, but the result is the same.

. . . The desire to keep blacks with money out of white

neighborhoods is even stronger when the blacks are persons

of low income. The housing problem today is critical.” (Em

phasis added)

This affidavit was uncontradicted.

2 8

in the private market. Cf. Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Re

development Agency, 395 F.2d 920, 931. For many of them,

low income public housing represents their only hope for

decent, safe and sanitary housing.29

Nor is California unique for the pervasiveness of its

housing discrimination. Across the land “real estate brok

ers and mortgage lenders are largely dedicated to the main

tenance of segregated communities.” Reitman v. Mulkey,

supra, at 381 [Douglas, J., concurring]. Restrictive “neu

tral” zoning ordinances exclude minority groups. See,

e.g., Sager, Tight Little Islands: Exclusionary Zoning,

Equal Protection, and the Indigent, 21 S tax . L. R ev. 767

(1968). Discriminatory private marketing practices, Jones

v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968); Lee v. Southern

Home Sites Corp., ----- F.2d ——- (5th Cir. No. 28167,

July 13, 1970) are widespread. Public agencies have been

found to perpetuate segregation in administration of site

location in public housing projects, Gautreaux v. Chicago

Housing Authority, 296 F. Supp. 907 (N.D. 111. 1969); Hicks

v. Weaver, 302 F. Supp. 619 (E.D. La, 1969), in relocating

displacees, Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment

Agency, supra; and in misuse of regulatory procedures to

prevent the construction of housing for blacks, Kennedy

Park Homes Association v. City of Lackawanna, ----- F.

Supp. —— (W.D.N.Y. August 13, 1970) (expedited appeal

pending, No. 35320, 2nd Cir.).

One final variety of devices that effectively perpetuate

residential segregation attempts to conceal the discrimina

tory object behind a “democratic” referendum. See Hunter

v. Erickson, supra, and Reitman v. Mulkey, supra, invali

dating respectively the use and the product of such refer

enda. The lower court cases upholding the use of referenda,

29 See Affidavit of William G-. Weman, Executive Director of the

Housing Authority of San Mateo County, Appendix pp. 122-124.

29

on which Appellant Shaffer heavily relies,80 are all dis

tinguishable. In Ranjel v. City of Lansing, 417 F.2d 321

(6th Cir. 1969), cert. den. 397 U.S. 980 (1970), the Sixth

Circuit reversed a District Court decree enjoining such a.

referendum. The Ranjel situation differs fundamentally

from the case at bar in that the proposed referendum there

was a subsequent referendum in review of a legislative

decision relating to a zoning change which would permit

a low rent development. In Southern Alameda Spanish

Speaking Organisation v. City of Union City, 424 F.2d 291

(1970), the Ninth Circuit refused to nullify the result of a

referendum cancelling a similar zoning change. But as in

Ranjel, the referendum in question was of the ordinary

type, subsequent to the legislative action reviewed. In a

third case, Spaulding v. Rlair, 403 F.2d 862 (1968), the

Fourth Circuit refused to bar the submission of a state

open housing enactment to the electorate for approval or

rejection by referendum. Here again, the constitutional

challenge was directed at a subsequent referendum, which

was a mere repealer, not a bar to subsequent action, as in

Hunter, Reitman and this case. The Fourth Circuit merely

held that fair housing legislation was subject to the same

review by referendum as all other state legislation, and

was at pains to point out that the Maryland referendum

had no future effect, 403 F. 2d at 864. The gravamen of

appellee’s position here is that Article 34 does have pros

pective effect, and that it applies an extraordinary require

ment of prior review which does not (unlike the Maryland

provision) apply generally to other legislation. In none

of these three cases did the referendum force future housing

measures to run a special gauntlet.

The cases just discussed do indicate how widely the

referendum device has been used to exclude blacks and 30

30 Brief of Appellant Shaffer in No. 226 at 58-60.

30

other minorities from predominantly white areas like San

Mateo and Santa Clara Counties. To a great extent,

then, measures like Article 34 which raise insuperable

obstacles to low rent housing are in effect integral parts

of a nationwide housing pattern (not everywhere inten

tionally contrived) that perpetuates residential segrega

tion by race.

The analogy between the housing area and other im

portant fields is instructive. There, too, legislation and

constitutional litigation have all hut eliminated the gross

forms of open discrimination by race. But in those fields,

as in housing, a whole range of devices superficially neutral

hut covertly discriminatory has been developed as a result

of resourceful manipulation and the “accidental” workings

of economic realities.81

81 “Freedom of choice” school enrollment plans, Green v. New

Kent County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ; and dual school

systems within “desegregated” districts, Alexander v. Holmes, 396

U.S. 19 (1969), are among those devices to resist school integra

tion which have been recently struck down. In the voting rights

area, grandfather clauses fell long ago, Guinn v. United States,

238 U.S. 347 (1915); but more recent and subtler devices never

cease coming to light, including stringent and discriminatorily

applied literacy tests, South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301

(1966); Louisiana, v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965), cf. Vot

ing Eights Act of 1965 (42 U.S.C. §1973), Voting Eights Act