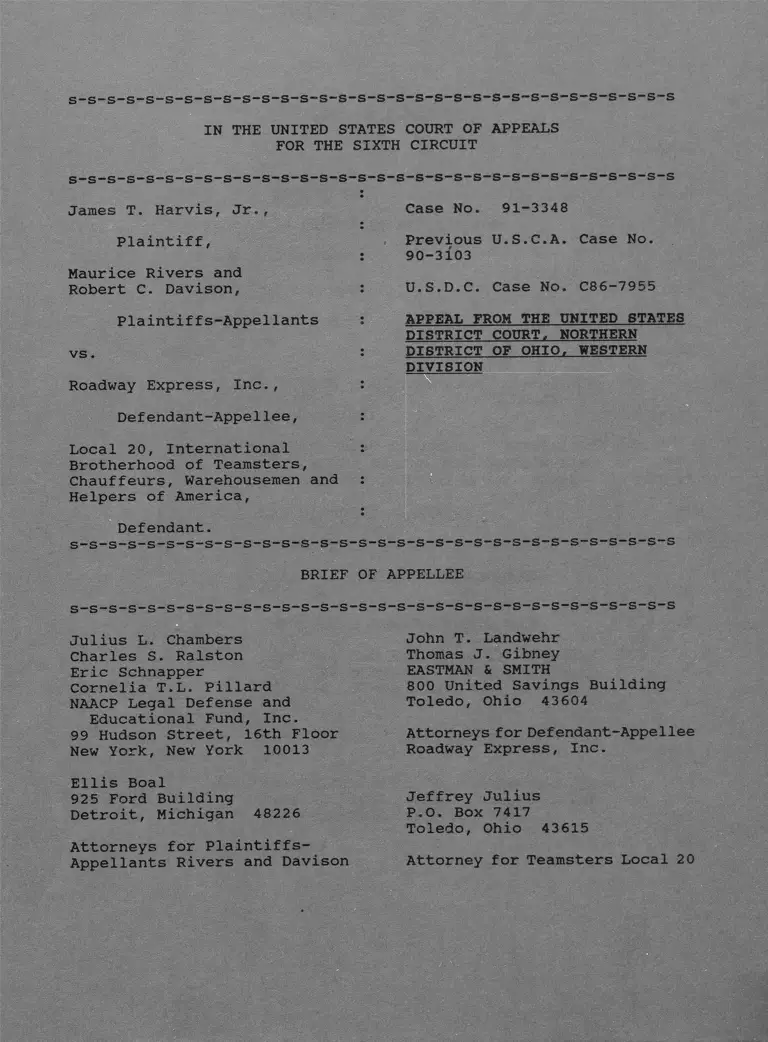

Harvis v. Roadway Express, Inc. Brief for Appellee

Public Court Documents

September 21, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harvis v. Roadway Express, Inc. Brief for Appellee, 1991. c8426da7-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8c1c6dd8-c363-4353-b457-c98288e10085/harvis-v-roadway-express-inc-brief-for-appellee. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S -S

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s

Case No. 91-3348James T. Harvis, Jr.,

Plaintiff,

Maurice Rivers and

Robert C. Davison,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

vs.

Roadway Express, Inc.,

Defendant-Appellee,

Local 20, International

Brotherhood of Teamsters,

Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and

Helpers of America,

Previous U.S.C.A. Case No.

90-3103

U.S.D.C. Case No. C86-7955

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

DISTRICT COURT. NORTHERN

DISTRICT OF OHIO. WESTERN

DIVISION

Defendant.s_s_s_s_s-s_s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s~s

BRIEF OF APPELLEE

s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s

Julius L. Chambers

Charles S. Ralston

Eric Schnapper

Cornelia T.L. Pillard

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Ellis Boal

925 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellants Rivers and Davison

John T . Landwehr

Thomas J. Gibney

EASTMAN & SMITH

800 United Savings Building

Toledo, Ohio 43604

Attorneys for Defendant-Appellee

Roadway Express, Inc.

Jeffrey Julius

P.O. Box 7417

Toledo, Ohio 43615

Attorney for Teamsters Local 20

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Paa.e

I. TABLE OF AUTHORITIES iii-iv

II. DISCLOSURE OF CORPORATE AFFILIATION V

III. STATEMENT OF ISSUES vi

IV. STATEMENT OF THE CASE 1-8

V. STATEMENT OF FACTS 9-15

VI. ARGUMENT 16-36

A. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY DISMISSED

APPELLANTS' §1981 DISCRIMINATORY

DISCHARGE CLAIMS. 17-21

B. APPELLANTS' "NEW" CLAIMS OF RETALIATION

FAILED TO STATE CLAIMS FOR WHICH RELIEF

COULD BE GRANTED UNDER 42 U.S.C. §1981. 21-33

1. The Standard of Review 21

2 . Appellants' Limited Contentions 21-23

3. Outline of the Arauments

Presented 23-24

4. Overview: The Component Parts 24-25

5. Appellants Do Not Claim That Roadwav

Impaired or Impeded Their Ability to

Enforce Their Claimed Contract

Rights 25-30

6. Retaliation Alone is Not Action-

able 30-32

7. Appellants Had the Opportunity to

Pursue Their Discriminatorv Dis-

charae Claims Under Title VII 32-33

8. Summary 33

i

C. APPELLANTS' CLAIMS CANNOT SURVIVE THE

UNAPPEALED SUMMARY JUDGMENT ORDER,

ESTABLISHING THEIR UNIMPAIRED ACCESS TO

THE GRIEVANCE PROCESS 33-36

VII. CONCLUSION 37-38

VIII. PROOF OF SERVICE 39

IX. ADDENDUM (Cross-Designation of Contents

Joint Appendix)

of

40-41

X. ADDENDUM (Statutes, Regulations, Rules

Unreported Cases, Etc.)

and

42f

ii

I. TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

Ana v. Proctor & Gamble Co.. 932 F.2d 540, 544

(6th Cir. 1 9 9 1 ) ............................................... 21

Bohanan, Jr. v. United Parcel Service, unreported,

No. 90-3155, 1990 U.S. App. LEXIS 20154 (6th Cir.

November 14, 1 9 9 0 ) ......... ................................. 25

Carter v. South Central Bell. 912 F.2d 832, 840

(5th Cir. 1990), cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2916

(1991) ...................................... 20, 24, 25, 28, 32

Christian v. Beacon Journal Publishing Co.. unreported,

No. 89-3822, 1990 U.S. App. LEXIS 12080 (6th Cir.

July 17, 1990) 25

Connelly v. Gibson. 355 U.S. 41, 45, 46 (1957) ......... 21, 35

Cooper v. City of North Olmstead. 795 F.2d 1265, 1272

(6th Cir. 1 9 8 6 ) ............................................... 20

D. Frederico Co.. Inc, v. New Bedford Redevelopment

Authority. 723 F.2d 122 (1st Cir. 1 9 8 3 )..................... 19

Dash v. Equitable Life Assur. Soc. of the U.S.. 753

F. Supp. 1062, 1066-1067 (E.D. N.Y. 1990) ................... 28

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co.. 482 U.S. 656 (1987) . 18, 26-29, 34

Groves v. Ring Screw Works. 882 F.2d 1081 (6th Cir.

1989), rev'd., Ill S. Ct. 498 (1990) ........................ 27

Hall v. County of Cook. 719 F. Supp. 721, 724-25 (N.D.

111. 1989) 29

Halverson v. Wood. 309 U.S. 344 (1940) 5

Harvis v. Roadway Express, Inc., 923 F. 2d 59

(6th Cir. 1 9 9 1 ) ...................................................4

Hull v. Cuyahoga Valiev Bd. of Educ.. 926 F.2d 505,

509 (6th Cir.), cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2917 (1991) . . 16, 25

Jackson v. Havakawa. 605 F.2d 1121 (9th Cir. 1979),

cert, denied. 445 U.S. 952 (1980)............................. 19

iii

McKniaht v. General Motors Corp.. 908 F.2d 104, 111

(7th Cir. 1990), cert. denied. 111 S. Ct. 1306 (1991) . . 28, 34

Moore v. City of Paducah. 790 F.2d 557 (6th Cir. 1986) . . . 19

Northern Pipeline Construction Co. v. Marathon Pipe

Line Co. . 458 U.S. 50 (1982) .................................. 5

Overby v. Chevron U.S.A.. Inc., 884 F.2d 470, 473

(9th Cir. 1 9 8 9 )........ ......................... 20, 25, 26, 28

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 491 U.S. 164 (1989) . . 2, 5-7,

16, 17, 21-26, 30-32, 34, 37

Prather v. Davton Power & Light Co.. 918 F.2d 1255,

1258 (6th cir. 1990), cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2889

(1991) ........ ............ ........................... 16, 18-20

Thomokins v. Dekalb County Hosp. Auth.. unreported,

No. 1:87—cv-303—RLV, 54 FEP cases 1424, 1425 (N.D.

Ga. February 7, 1990), aff'd, 916 F.2d 600 (11th

Cir. 1990) ................................................... 26

Userv v. Turner Elkhorn Mining Co.. 428 U.S. 1 (1976) ........ 5

Von Zuckerstein v. Argonne National Laboratories. 760

F. Supp. 1310 (N.D. 111. 1991) ............................ 28-30

Statutes

29 U.S.C. §159 (a) ............................................ 1

29 U.S.C. §185 ( a ) .................................... 3, 6, 33-35

42 U.S.C. §1981 . . 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 17-21, 24, 25, 30, 31,33-35, 37

42 U.S.C. §2000e, et s e g . .................................. . . 1

Rules

6th Cir. R. 1 0 ( b ) ....................... ....................... 9

Fed. R. App. P. 2 8 ( a ) ...........................................9

Fed. R. Civ. P. 8 . . . . .......... .. 20

iv

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

(This statement should be placed immediately preceding the statement of issues contained

in the brief of the party. See copy of 6th Cir. R. 25 on reverse side of this form.)

IX.

James T. Harvis, Jr.,

Plaintiff,

Maurice Rivers and

Robert C. Davison,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

v.

Roadway Express, Inc.,

Defendant-Appellee,

Local 20, International Brotherhood of

Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen

and Helpers of America,

Defendant.

) Case No. 91-3348

)

) Previous U.S.C.A. Case No. 90-3103

)

) U.S.D.C. Case No. C86-7955

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

DISCLOSURE OF CORPORATE AFFILIATIONS

AND FINANCIAL INTEREST

Pursuant to 6th Cir. R. 25, Roadway Express, Inc.

makes the following disclosure:

(name of party)

1. Is said party a subsidiary or affiliate of a publicly owned corporation? ^Yes^_

If the answer is YES, list below the identity of the parent corporation or affiliate

and the relationship between it and the named party:

Roadway Express, Inc. is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Roadway Services, Inc.

2. Is there a publicly owned corporation, not a party to the appeal, that has a

financial interest in the outcome? No.______

If the answer is YES, list the identity of such corporation and the nature of the

financial interest:

6CA-1

7/86 v.

III. STATEMENT OF ISSUES

1. DID THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY DETERMINE THAT §1981

DOES NOT APPLY TO DISCRIMINATORY DISCHARGES?

2. DID THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY DETERMINE THAT

BECAUSE APPELLANTS CLAIMED NO DENIAL OF ACCESS TO

GRIEVANCE AND JUDICIAL ENFORCEMENT FORUMS THEIR

"RETALIATION" CLAIM FAILED TO STATE A CLAIM UNDER

§1981?

3. DOES THE DISTRICT COURT'S FINDING OF NO EVIDENCE OF

ARBITRARINESS, DISCRIMINATION OR BAD FAITH IN THE

PROCESSING OF APPELLANTS' GRIEVANCES BAR ANY CLAIM

OF IMPAIRED ENFORCEMENT RIGHTS?

vi

IV. STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This action was filed on December 22, 1986 by plaintiff

James T. Harvis, Jr. ("Harvis") and plaintiffs-appellants Maurice

Rivers and Robert C. Davison ("Rivers" and "Davison" respectively

when referred to individually, and "Appellants" when Rivers and

Davison are referred to jointly), past employees of Roadway

Express, Inc. ("Roadway"). (R. 1: 1/22/86 Complaint.) Appellants

alleged race discrimination, breach of a collective bargaining

agreement, and breach of the duty of fair representation by

defendant Local 20, International Brotherhood of Teamsters,

Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers of America ("the Union").

Appellant's First Amended Complaint addressed those allegations

under 42 U.S.C. §§1981 and 2000e, et sea.. and 29 U.S.C. §§159(a)

and 185(a) ("§301"). (R. 218: 10/18/88 First Amended Complaint.)

For purpose of this appeal the difference between the First Amended

Complaint and the Complaint is not significant, because the First

Amended Complaint merely attempted to add a claim against Roadway

under 42 U.S.C. §2000e, et sea.. commonly known as Title VII.

(Compare R. 1: 1/22/86 Complaint and R. 218: 10/18/88 First Amended

Complaint.) Appellants' §1981 claim against Roadway, as stated in

the First Amended Complaint, was limited as follows:

16. The discharges discriminated against the plaintiffs

because of their race in violation of 42 U.S.C. §1981.

[Emphasis Added.]

(R. 218: 10/18/88 First Amended Complaint.) The issue in this case

is primarily whether Appellants' claim of a discriminatory

1

discharge pursuant to §1981 survives Patterson v. McLean Credit

Union, 491 U.S. 164 (1989).

Appellants moved to file a Second Amended Complaint, were

granted leave to withdraw that Second Amended Complaint, and

requested leave to file a Third Amended Complaint. (R. 68:

10/19/87 Second Motion to Amend Complaint; R. 109: 12/1/87 Pretrial

Order; R. 124: 12/8/87 Motion for Leave to File Third Amended

Complaint.) Leave was denied. (R. 173: 6/6/88 Magistrate's Report

and Recommendation; R. 203: 9/1/88 Order.) The stated purpose of

Appellants' proposed Second and Third Amended Complaints was to

attempt to state a cause of action against the Union under §1981.

(R. 68: 10/19/87 Second Motion to Amend Complaint; R. 124: 12/8/87

Motion for Leave to File Third Amended Complaint.) Adding to the

allegations in their previous two complaints, Appellants, in their

Second Amended Complaint, claimed:

7. For many years Local 20 and Roadway have negotiated

collective bargaining contracts which contain no wording

or prohibition against the company and union committing

race discrimination.

8. Local 20 has not sought to include such anti-

discrimination language in its contract with Roadway.

9. The union officers and business agents have had a

continuing pattern, practice or policy over the years of

not pursuing race discrimination claims against Roadway

in the grievance procedure, whether or not they believe

[sic] that Roadway had practiced race discrimination in

a particular case.

(R. 68: 10/19/87 Second Motion to Amend Complaint, proposed Second

Amended Complaint attached, at p. 2.) In their Third Amended

Complaint, Appellants sought to add, to the new allegations of the

Second Amended Complaint, the following allegation:

2

10. Despite having the foregoing pattern, practice,

and/or policy, Local 20 has purported to establish a non

discrimination policy in regard to representing its

membership in any area, and further purports to represent

members in discrimination grievances notwithstanding the

absence of a non-discrimination clause in a contract.

(R. 124: 12/8/87 Motion for Leave to File Third Amended Complaint,

proposed Third Amended Complaint attached, at p. 3.) Appellants

explained their desire to add a claim against the Union as follows:

The proposed new complaint alleges the same basic

transaction and conduct by the union: improper grievance

handling of the plaintiffs' discharges. It simply adds

an additional motive - race discrimination - for the

union's action.

(R. 68: 10/19/87 Second Motion to Amend Complaint, p. 2.) Both the

proposed Second and Third Amended Complaints sought to attribute

the impairment of the grievance process to the Union only; neither

proposed amended complaint alleged that Roadway had impaired

Appellants' recourse to the grievance procedure. (R. 68: 10/19/87

Second Motion to Amend Complaint, proposed Second Amended Complaint

attached; R. 124: 12/18/87 Motion for Leave to File Third Amended

Complaint, proposed Third Amended Complaint attached.) As noted,

Appellants' second and third attempts to amend were unsuccessful.

(See supra. p. 2.)

Roadway and the Union filed summary judgment motions on

all counts of the First Amended Complaint. (R. 88: 11/16/87

Roadway Motion for Summary Judgment; R. 113-115: 12/1/87 Union

Motions for Summary Judgment.) On November 30, 1988, the District

Court granted in part Roadway's Motion for Summary Judgment

dismissing Appellants' and Harvis' hybrid §301 (29 U.S.C. §185(a))

3

claim. (R. 224: 11/30/88 Memorandum and Order.) The District

Court found:

The claims of all three plaintiffs involved their

discharge from employment with defendant Company.

Grievances were filed in each plaintiff's case and each

grievance was processed through final and binding

arbitration in accordance with the collective bargaining

agreement. The record in this case is voluminous. It

includes hundreds of pages of briefing and thousands of

pages of deposition testimony and exhibits. Despite this

extensive record, plaintiffs have failed to present any

evidence of arbitrariness, discrimination or bad faith

in the processing of their grievances.

(R. 224: 11/30/88 Memorandum and Order at pp. 2-3.) Appellants'

claims that survived summary judgment were described by the

District Court, simply, as follows:

Plaintiffs claim that their discharges are racially

motivated.

(R. 224: 11/30/88 Memorandum and Order at p. 6.)

Harvis' §1981 claim1 was tried to a jury commencing May

30, 1989; at the conclusion of the trial on June 13, 1989, the jury

entered a unanimous verdict for Roadway. (R. 243: 5/30/89 Minutes

of Proceedings; R. 254: 6/13/89 Special Verdict.) On January 9,

1990, the District Court ordered judgment in favor of Roadway on

Harvis' §1981 and Title VII claims, and certified its order as

appealable. (R. 264: 1/9/90 Memorandum and Order; R. 266: 1/23/90

Judgment on Decision by Court.) Harvis appealed to this Court,

complained about the jury's role, and, ironically, sought to have

his claim redetermined by the trial judge. Harvis— v_.— Roadway

Express. Inc.. 923 F. 2d 59 (6th Cir. 1991). (Rivers and Davison

^he District Court ordered a separate trial on Harvis' claim.

(R. 229: 3/14/89 Memorandum and Order.)

4

seek the exact opposite result!) This Court denied Harvis* appeal

and affirmed the trial court's judgment. Id. at p. 62.

Shortly after the Harvis verdict, the Supreme Court

decided Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 419 U.S. 164 (1989); on

July 10, 1989 the District Court ordered Appellants to show cause

why their §1981 claims should not be dismissed. (R. 257: 7/10/89

Order.) In response, Appellants conceded that Patterson precluded

claims of discriminatory discharge.2 (R. 259: 8/25/89 Appellants'

Response to Show Cause Order.) Appellants alleged, however, for

the first time, that:

Rivers and Davison were discriminated against racially

for enforcing their contract. Accordingly to the extent

that the case rests on a retaliation claim a valid claim

under §1981 remains.

(R. 259: 8/25/89 Appellants' Response to Show Case Order at p. 11.)

Appellants offered no reason for the omission of a retaliation

claim against Roadway from their earlier Complaints. (R. 1:

1/22/86 Complaint; R. 218: 10/18/88 First Amended Complaint; R.

259: 8/25/89 Appellants' Response to Show Cause Order.)

2In their brief, Appellants' seek to preserve a claim that

their discharges violated the "right...to make... contracts"

language of §1981. (Appellants' Brief, pp. 22-23, n. 11.) There

is nothing to preserve. An appellate court should not entertain

an argument based upon a theory not litigated below. Halverson v...

Wood. 309 U.S. 344 (1940). See, also Usery v._Turner Elkhorn

Minina Co. . 428 U.S. 1 (1976). Moreover, Appellants' reliance upon

Northern Pipeline Construction Co. v. Marathon Pipe Line_Qo_._, 458

U.S. 50 (1982) to seek a stay is misplaced. In Northern Pipeline,

the Supreme Court invalidated the legislative grant of jurisdiction

to bankruptcy judges, applied its holding prospectively, and

permitted Congress a limited amount of time to reconstitute the

bankruptcy courts. (Id. at p. 88.) In Patterson the Supreme Court

applied its holding retrospectively and granted no stay. Patterson

is the law and must be applied until the legislature or the Supreme

Court compels otherwise.

5

Answering Appellants' response, Roadway argued that

Appellants' claims as stated in the First Amended Complaint should

be dismissed, objected to the District Court's consideration of

Appellants' new retaliatory discharge claim as beyond the

allegations of the First Amended Complaint, questioned the

viability of an attempt by Appellants to further amend their

complaint, argued that Appellants' desire to ''remedy their attempts

to enforce the collective bargaining contract" had previously been

disposed of by summary judgment against their §301 claims, and,

finally, argued that Appellants' "bare claim of retaliation" even

if considered did not survive analysis under Patterson. (R. 261:

9/6/89 Roadway Brief at pp. 10-19.) On that last point, Roadway

argued:

Rivers and Davison have failed to allege that they were

impeded or obstructed from access to the grievance

procedure to redress their claim of retaliatory

discharge. Indeed, as this court well knows, Rivers and

Davison not only had, but took full advantage of, the

opportunity to redress their claims through the grievance

arbitration machinery as well as by access to the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission. Equal access to the

means available to the parties to enforce contracts is

the crux of a §1981 claim. Plaintiffs had such access,

make no claim that their access was impeded or

obstructed, and ultimately complain of only a

discriminatory discharge.

(R. 261: 9/6/89 Roadway Brief, at p. 18.) Appellants responded as

follows:

Roadway argues that Rivers and Davison had the later

opportunity to address the discharges through the

grievance procedure, the EEOC, and the court. That may

be. But the claim of denial of access to those forums

is not the claim here. The claim is that the discharges

themselves were infected by racial animus in the first

place. [Emphasis Added.]

6

(R. 263: 9/13/89 Appellants' Reply, at p. 6.)3

Appellants further took the position that no new

complaint was necessary, but suggested that they were willing to

again attempt to amend their complaint "to satisfy any formality

by filing one." (R. 263: 9/13/89 Appellants' Reply at p. 4.) No

such further amendment was ever proffered or filed by Appellants.

(Record.)

After considering the memoranda filed by the parties, the

District Court ruled that:

(1) Appellants claimed in their pleadings only a

discriminatory discharge;

(2) §1981 does not apply to discriminatory discharges;

and

(3) Appellants' contention of a retaliatory discharge

failed to state a claim in light of Patterson and

Appellants' concession that "the claim of denial of

access to those [grievance and judicial forms] is

not the claim here."

(R. 264: 1/9/90, Memorandum and Order at pp. 3-4.) The Court

therefore dismissed Appellants' §1981 claims. (R. 264: 1/9/90

Memorandum and Order at p. 4.)

Appellants' Title VII claims were tried from February 27

through March 2, 1990. (R. 283-285: 2/27/90-3/5/90 Minutes of

Proceedings.) On October 18, 1990 the District Court rendered its

findings of facts and conclusions of law and ordered that judgment

be entered in favor of Roadway and against Appellants. (R. 306:

3Roadway's review of the arguments presented in response to

the District Court's Show Cause Order is necessary because

Appellants' claim of a retaliatory discharge is nowhere else

"pleaded" in the record.

7

10/18/90 Findings of Facts and Conclusions of Law, at p. 11; R.

307: 10/18/90 Judgment■on Decision by Court.) Appellants filed a

Motion for Reconsideration which was considered and denied by the

District Court on March 18, 1991. (R. 308: 10/22/90 Motion for

Reconsideration; R. 310: 3/18/91 Memorandum and Order.)

Appellants filed their Notice of Appeal on April 17, 1991

citing the District Court's January 9, 1990 Memorandum and Order4

which dismissed their §1981 claims, the District Court's October

18, 1990 Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law which dismissed

their Title VII claims, and the District Court's March 18, 1991

Memorandum and Order which denied their motion for reconsideration.

(R. 311: 4/17/91 Notice of Appeal.) Appellants did not appeal the

District Court's November 30, 1988 Summary Judgment Order. (id.)

Appellants address only the District Court's January 9, 1990

Memorandum and Order in their brief to this Court.

Actually, appellants' Notice of Appeal identifies "the

court's memorandum and order of January 19, 1990" as the order

appealed from. (R. 311: 4/17/91 Notice of Appeal.) There is no

such order.

8

V. STATEMENT OF FACTS

Much of the argumentative nature of Appellants' statement

of facts is highlighted by Appellants' frequent omission of any

reference to the record to support their statements as required by

6th Cir. R. 10(b) and Fed. R. App. P. 28(a). Roadway adopts and

repeats below the findings of fact rendered by the District Court

after a full trial on the merits, and supplements the District

Court's findings with citations to the record. The Honorable John

W. Potter — after presiding over this case for nearly four years

— rendered the following findings of fact:

1. Plaintiffs are black male citizens of the United

States and reside within the territorial jurisdiction of

this Court. [R. 218: 10/11/88 First Amended Complaint

at para. 4.]

2. Defendant does business in Toledo, Ohio and is

an employer within the meaning of 42 U.S.C. §2000(b).

[R. 218: 10/18/88 First Amended Complaint at para. 2.]

3. Plaintiffs began working for Roadway in 1972 in

Akron, Ohio. Rivers began working on the dock, while

Davison began working in the garage. Both plaintiffs

transferred to the Roadway facility in Toledo, Ohio in

1975. [R. 94: 11/16/87 Davison Deposition at pp. 7, 45-

46; R. 99: 11/16/87 Rivers Deposition at pp. 8-9.]

4. Roadway Garage Manager Ed Guy and Union business

Agent Paul Toney agreed upon August 20, 1986 as the date

on which a hearing would be held to discuss Davison's

accumulated work record. On August 15, 1986, a letter

was sent out to confirm this date. The hearing was

postponed and rescheduled for August 22, 1986 by

agreement between Mr. Guy and Mr. Toney. [Cf. R. 99:

11/16/87 Rivers Deposition at pp. 292, 295-6, 298.]

5. Paul Toney was the union representative who was

responsible for scheduling disciplinary hearings with

defendant. Mr. Toney testified that he would mislead and

even lie to Roadway in his attempts to stall hearings in

the hope of resolving the matter on an informal basis.

9

Mr. Toney used this procedure for a number of employees,

both black and white. [R. 88: 11/16/87 Roadway Summary

Judgment Motion, excerpts of Toney Deposition attached

at pp. 154-156, 159-160, 162.]

6. Toney testified that he believed that some time

prior to August 22, 1986 Guy became aware of his stalling

tactics and his history of avoiding disciplinary

hearings. Plaintiffs were employees for whom Toney had

employed such tactics. As a result, Guy demanded that

a disciplinary hearing occur within 72 hours of the

request. This procedure was a proper notification

procedure due to a 1971 ruling. [R. 88: 11/16/87 Roadway

Summary Judgment Motion, excerpts of Toney Deposition at

pp. 154-156, 159-160, 162 and O'Neill 11/11/87 Affidavit

attached.]

7. On the morning of August 22, 1986 at

approximately 7:30 A.M. , Davison was told by foreman Bill

Thompson that there was going to be a disciplinary

hearing concerning Davison. Davison was told to go to

the office and complied. When he arrived at the garage

office, Davison told Guy that he had not received a

letter in the mail informing him of a hearing and the

[sic] he would not attend the hearing. Guy told Davison

that he had received the proper notice for the hearing

and that the hearing would be held whether he was there

or not. Davison then left the office. [R. 94: 11/16/87

Davison Deposition at pp. 188-190.]

8. Davison was subsequently informed by Toney that

he had received a two-day suspension as a result of the

hearing that was conducted in his absence. That

suspension was based on Davison's accumulated work

record. [R. 94: 11/16/87 Davison Deposition at p. 191.]

9. Davison filed a grievance alleging that his

suspension was without just cause and without proper

notification. [R. 94: 11/16/87 Davison Deposition at p.

193. ]

10. Guy and Toney also agreed upon August 20, 1986

as the date on which a hearing would be held to discuss

Rivers' accumulated work record. On August 15, 1986, a

letter was sent to confirm this date. That hearing was

postponed and rescheduled for August 22, 1986 by

agreement between Guy and Toney. [R. 99: 11/16/87

Rivers Deposition at pp. 292, 295-96, 298.]

11. In the early morning of August 22, 1986,

Roadway's supervisor Bill Thompson told Rivers that he

had heard Rivers was having a disciplinary hearing later

10

that day. Rivers stated that he had not received a letter

notifying him of a hearing on August 22 and that as far

as he was concerned no hearing would take place. [R. 99:

11/16/87 Rivers Deposition, pp. 298-299.]

12. At approximately 7:30 A.M. on the morning of

August 22, a Roadway foreman approached Rivers and told

him to go to the office for a hearing. Although Rivers

went to the office, he informed Guy that he had not

received proper notice of the hearing. Although Rivers'

Union Business Agent was present, Rivers replied that he

did not think he should be there for the hearing and he

was not properly represented. While Rivers claims he was

excused, the Court finds that he was not. [R. 99:

11/16/87 Rivers Deposition at pp. 300-301.]

13. Rivers subsequently received a letter from

Roadway dated August 22, 1986 which indicated that as a

result of a hearing on his accumulated work record, he

was given a two-day suspension. [R. 99: 11/16/87 Rivers

Deposition at p. 302.]

14. Rivers filed a grievance alleging that his

suspension was without just cause and without proper

notification. [R. 99: 11/16/87 Rivers Deposition at p.

304. ]

15. The Toledo Local Joint Grievance Committee

(TLJGC) convened and heard both grievances on September

23, 1986. During the hearings, plaintiffs argued that

they had not received proper notice for their

disciplinary hearings, that if they had received proper

notice they would have been present at their disciplinary

hearings, and that white employees Sedelbauer, Bradley

and Swartzfager should have had disciplinary hearings

scheduled before plaintiffs as Roadway had requested

hearing dates for those three individuals prior to

requesting hearing dates for plaintiffs. Both grievances

were granted based upon "improprieties," and both

plaintiffs were awarded two days of back pay. [R. 94:

11/16/87 Davison Deposition at p. 218; R. 99: 11/16/87

Rivers Deposition at pp. 317-328.]

16. Disciplinary hearings had been requested for

Swartzfager on June 6, 1986, Davison on July 14, 1986,

Rivers on August 1, 1986, Sedelbauer on August 8, 1986

and for Bradley on August 11, 1986. Swartzfager had a

disciplinary hearing scheduled for July 9, 1986 which did

not occur as he was on vacation that week. Union Steward

Eugene McCord was instrumental in the postponement of

Swartzfager's hearing as he informed Guy on several

11

occasions that Swartzfager*s attendance record was not

that bad and a hearing was not necessary.

17. Based •upon these facts and the credible

testimony of Dr. Cranny, black employees were not treated

differently than white employees with respect to the

scheduling of disciplinary hearings. [R. 292: 4/11/90

Dr. Cranny Transcript at pp. 13-16.]

18. Shortly after the decision of the TLJGC was

announced, Roadway's Labor Relations Manager James

O'Neill announced there would be disciplinary hearings

on employees Rivers, Davison, Bradley, Sedelbauer and

Swartzfager within 72 hours. Both plaintiffs were present

when O'Neill announced the upcoming hearings. Davison

responded that he could not attend as he had a doctor

appointment, and McCord responded that he could not

attend as it was his day off. After some discussion,

O'Neill and Toney agreed upon the date of September 26,

1986 at 7:00 A.M. for the hearings. [R. 94: 11/16/87

Davison Deposition at pp. 218-19; R. 99: 11/16/87 Rivers

Deposition at p. 392.]

19. The race of Swartzfager, Sedelbauer and Bradley

is white. [R. 88: 11/16/87 Roadway Summary Judgment

Motion, O'Neill 11/16/87 Affidavit attached.]

20. On September 25, 1986, [R]oadway supervisor

Robert Kresge delivered and read a written notice of

hearing to Davison at work which stated that a hearing

would be held for him on September 26, 1986 at 7:00 A.M.

and asked him to sign a receipt acknowledging his

upcoming hearing. Davison spoke with McCord and refused

to sign the paper. Kresge left the written notice on a

tool box next to Davison. Davison claims that the notice

was not read to him and that he was not notified of the

hearing date and time. McCord, however, testified that

Kresge read the notice to Davison. Based on this

testimony, the Court finds that Davison was told on the

morning of September 25, 1986 that a disciplinary hearing

would be held for him on September 26, 1986. [R. 94:

11/16/87 Davison Deposition at pp. 223-226.]

21. On September 26, 1986, Toney informed Davison

that Roadway was having a hearing for him that day. He

told Davison that Davison should attend the hearing

because he had been given a direct order to do so and

that Davison could be discharged if he did not attend the

hearing. Davison maintained that he had not received the

proper notice. [R. 94: 11/16/87 Davison Deposition at

pp. 226-227.]

12

22. Davison was then approached by Roadway

supervisors Broome and Gates who ordered him to go to the

office for a hearing. Davison proceeded toward the

office but stopped to talk to Toney and McCord. [R. 94:

11/16/87 Davison Deposition at pp. 230-231.]

23. Kresge approached Davison, in the presence of

McCord and Toney, and again ordered him to go into the

office, but Davison replied, "I'm talking to Paul, get

out of my face." After some time elapsed, Davison walked

into the office. [R. 11/16/87 Davison Deposition at pp.

230-231.]

24. Once in the office, a heated discussion ensued

between McCord, O'Neill, Toney, and Davison about whether

the hearing should take place. Davison was informed that

he could be discharged if he did not attend the hearing.

Twenty-five minutes elapsed while the parties discussed

whether or not to proceed. Finally, O'Neill told Kresge

to start the hearing. Kresge started the hearing, and

Davison and McCord left the office and returned to work.

[R. 94: 11/16/87 Davison Deposition at p. 233; R. 88:

11/16/87 Roadway Summary Judgment Motion, excerpts of

O'Neill Deposition attached at pp. 75-76.]

25. On September 25, 1986 Rivers was approached by

Kresge, who delivered and read to Rivers a written notice

of hearing for September 26, 1986 and asked Rivers to

sign a form acknowledging that a hearing would be held

the next day. McCord, who was present at the time, told

Rivers that he was not obligated to sign the form.

Rivers refused to sign or take the document acknowledging

that a hearing would be held the next day. [R. 99:

11/16/87 Rivers Deposition at pp. 338-39.]

26. Shortly after 7:00 A.M. on September 26, 1986,

Roadway Supervisors Broome and Gates approached Rivers

at work. Broome ordered Rivers togo [sic] into the

office because Roadway was going to have a disciplinary

hearing concerning his accumulated work record. [R. 99:

11/16/87 Rivers Deposition at p. 342.]

27. After discussing this matter with Toney, Toney

informed Rivers that failure to attend the hearing could

result in discharge. [R. 99: 11/16/87 Rivers Deposition

at pp. 343-345.]

28. Kresge then went to the garage break room where

Rivers was speaking with McCord and Toney, told them that

the hearing was ready to begin and order [sic] Rivers to

attend the hearing. [R. 99: 11/16/87 Rivers Deposition

at pp. 346-347.]

13

29. Later O'Neill approached Rivers, McCord and

Toney and stated that the Company was ready to begin the

hearing. Rivers, Toney and McCord went into the office.

After O'Neill began the hearing, Rivers walked out. [R.

99: 11/16/87 Rivers Deposition at pp. 348-352.]

30. Similarly, on September 25 and 26, 1986,

Sedelbauer was directly ordered numerous times by various

Roadway supervisors to attend a hearing on his

accumulated work record scheduled for September 26, 1986.

[R. 88: 11/16/87 Roadway Summary Judgment Motion,

O'Neill 11/16/87 Affidavit attached.]

31. Sedelbauer, like Rivers and Davison, refused

those direct orders to attend his disciplinary hearing

on September 26, 1986. [R. 88: 11/16/87 Roadway Summary

Judgment Motion, O'Neill 11/16/87 Affidavit attached.]

32. Swartzfager was also given direct orders to

attend a disciplinary hearing to be held on September 26,

1986. Swartzfager complied with those orders and

attended the disciplinary hearing. Swartzfager was given

a disciplinary record of hearing but did not receive any

other disciplinary time off without pay. [R. 88:

11/16/87 Roadway Summary Judgment Motion, O'Neill

11/16/87 Affidavit attached.]

33. Throughout the time of these events on

September 26, 1986, Rivers, Davison, Sedelbauer and

Swartzfager were punched in and on the clock at work.

As such, they were obliged to follow the orders of their

supervisors unless the orders required unsafe actions.

[R. 94: 11/16/87 Davison Deposition at p. 226; R. 99:

11/16/87 Rivers Deposition at p. 342.]

34. Rivers was discharged on September 26, 1986 for

refusing several direct orders and for his accumulated

work record. Rivers was not discharged because of his

race. [Emphasis in Original.] [R. 99: 11/16/87 Rivers

Deposition at pp. 382-383.]

35. Davison was discharged on September 26, 1986

for refusing several direct orders and for his

accumulated work record. Davison was not discharged

because of his race. [Emphasis in Original.] [R. 94:

11/16/87 Davison Deposition at p. 249.]

36. Sedelbauer was discharged on September 26, 1986

for refusing several direct orders and for his

accumulated work record. [R. 88: 11/16/87 Roadway

14

Summary Judgment Motion, O'Neill 11/16/87 Affidavit

attached.]

37. The only employee to comply with the direct

orders of management, Swartzfager, was not discharged on

September 26, 1986 but was given a disciplinary record

of hearing. [R. 88: 11/16/87 Roadway Summary Judgment

Motion, O'Neill 11/16/87 Affidavit attached.]

38. The greater weight of the evidence clearly

demonstrates that there was no pattern or practice of

different treatment of blacks from whites at Roadway's

Toledo garage. From the statistical evidence introduced

by defendant, the Court finds that blacks and whites were

treated equally in the assignment of job duties and the

scheduling of disciplinary hearings. [R. 292: 4/11/90

Cranny Transcript at pp. 10-16.]

(R. 306: 10/18/90 Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law at pp.

2-8 .)

15

VI. ARGUMENT

Introduction

There is no dispute in this case whether Patterspn_Vj.

McLean Credit Union. 491 U.S. 164 (1989) should be applied

retroactively; it should. Hull v. Cuyahoga Valley,Bd. of.EducL,

926 F .2d 505, 509 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 111 S. Ct. 2917 (1991);

Prather v. Dayton Power & Light Co., 918 F.2d 1255, 1258 (6th Cir.

1990), cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2889 (1991). There is not much

dispute whether claims of discriminatory discharge survive

Patterson; Appellants conceded that point below but attempt to

revive it on appeal. This court has held that such claims do not

survive. (Id.)

Furthermore, Appellants do not contend that all claims

of retaliatory discharge survive Patterson and acknowledge that

most of the courts reviewing retaliatory discharge claims have

stricken those claims in light of Patterson. (Appellants' Brief,

pp. 13, 16-19.) Finally, there is no dispute that Appellants'

claims, however characterized, were actionable under Title VII,

that appellants availed themselves of their administrative and

judicial Title VII remedies but lost, that appellants' contract

claims were redressable under the grievance process and that

appellants, with unimpaired access to that process, grieved their

discharges, but likewise lost.

Yet, Appellants claim that they are entitled to another

trial on their allegations, because their claims somehow relate to

16

Becausethe right to enforce contracts protected by §1981.

Appellants' §1981 claims, as stated in their First Amended

Complaint, do not survive Patterson, because Appellants have not

claimed and have in fact admitted that their claims do not rest

upon the denial of access to any adjudicative forum, and because

the integrity of the grievance process and Appellants' unbridled

attempts to enforce their claimed contract rights are clearly

established by the record, this Court should deny Appellants'

appeal and affirm the judgment of the District Court.

A. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY DISMISSED APPELLANTS'

§1981 DISCRIMINATORY DISCHARGE CLAIMS.

Appellants' First Amended Complaint alleged only a claim

for discriminatory discharge, not a claim for retaliatory

discharge. Paragraph 16 states:

The discharges discriminated against the plaintiffs

because of their race in violation of 42 U.S.C. 1981.

[Emphasis Added.]

(R. 218: 10/18/88 First Amended Complaint.) In ruling on Roadway's

Motion for Summary Judgment and in deciding the effect of Patterson

on Appellants' claims the District Court clearly confirmed that all

that had been pled by Appellants was that "their discharges were

racially motivated." (R. 224: 11/30/88 Memorandum and Order at p.

6; R. 264: 1/9/90 Memorandum and Order at p. 3.)

Appellants knew the procedure by which to and the

importance of amending their complaint as they had attempted to do

so three times prior to Patterson. In fact, Appellants had

attempted, albeit unsuccessfully, to plead a claim of racial

17

discrimination impairing the enforcement of their contract rights

against the Union similar to the claim approved by the Supreme

Court in Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656 (1987). (R. 68:

10/19/87 Second Motion to Amend Complaint, proposed Second Amended

Complaint attached; R. 124: 12/8/87 Motion for Leave to File Third

Amended Complaint, proposed Third Amended Complaint attached.)

Yet, when Roadway argued below that Appellants' claims as pled

should be dismissed (R. 261: 9/6/89 Roadway's Brief at pp. 11-13),

Appellants merely responded that they were "willing to amend to

satisfy any formality," and did nothing to follow up even after the

District Court dismissed their limited claims. (R. 263: 9/13/89

Appellants' Reply at p. 4; R. 264: 1/9/90 Memorandum and Order at

p. 3.) Simply stated, Appellants' First Amended Complaint alleged

only discriminatory discharges, such claims are no long viable

under §1981, and the District Court properly dismissed Appellants'

§1981 claims. Prather v. Davton Power & Light Co.. 918 F.2d 1255,

1258 (6th Cir. 1990), cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2889 (1991).

In their brief to this Court, Appellants only make

passing reference to the failure of their pleadings below.

(Appellants' Brief, p. 7, n. 2.) Appellants erroneously contend

that "the district judge properly considered plaintiff's current

factual contentions, rather than the undeveloped allegations of the

First Amended Complaint." (Id.) Quite the contrary, the District

Court clearly distinguished between what Appellants had "pled," and

what they merely contended in their memoranda. (R. 264: 1/9/90

Memorandum and Order, compare pp. 3 and 4.)

18

Moreover, the case law Appellants rely upon to ameliorate

the insufficiency of their pleadings is inapposite. In Jackson v.

Havakawa, 605 F.2d 1121 (9th Cir. 1979) , cert, denied, 445 U.S. 952

(1980) the court made a special exception to the pleading rules in

order to uphold the application of the doctrine of res judicata.

Id. at p. 1129. Far from seeking to promote judicial economy and

the finality of judgments, Appellants in this case seek a second

trial, under a different statute, of their claims of

discrimination. D. Frederico Co. , Inc. v. New Bedford

Redevelopment Authority. 723 F.2d 122 (1st Cir. 1983) and Moore v.

City of Paducah. 790 F.2d 557 (6th Cir. 1986) involve,

respectively, a case where issues not raised by the pleadings had

been tried by express or implied consent of the parties, and a case

where a formal motion to amend had been denied. Neither situation

applies to this case.

Finally, Appellants opine that "the proper course" would

be for this Court to now remand the case to the District Court,

nearly five years after Appellants' discharges and the commencement

of this action, to permit them to attempt to amend their pleadings.

Appellants should have attempted to amend below, but relinquished

that right. Any amendment at this time would surely be highly

prejudicial. The District Court held some three years ago that the

proposed amendment by appellant to assert a §1981 "enforcement"

claim against the Union would unduly prejudice that defendant. (R.

203: 9/1/88 Order.) In Prather v. Dayton Power & Light Co., 918

F.2d 1255 (6th Cir. 1990), cert, denied. 111 S. Ct. 2889 (1991)

19

this Court faced a similar situation, except that the plaintiff had

proposed an amendment below, and in affirming the denial of leave

to amend, this Court held:

The magistrate denied appellant's motion to amend his

complaint because the amendment at this late date, eight

years after he was discharged and seven years after the

alleged intimidation, would be highly prejudicial to

appellee. Appellant's original and amended complaint

included only allegations of discriminatory discharge.

Appellant offers no reason for the omission of these

claims from his earlier complaint. The amendment relates

to entirely different conduct than that involved in the

original complaint, since the arbitration process was

never before at issue. To force appellant to formulate

a defense to these allegations at this late date would

be highly prejudicial. See. Foman v. Davis. 371 U.S. 178

(1962).

Id. at p. 1259. As in Prather. Appellants' original and amended

complaints included only allegations of discriminatory discharge,

and Appellants have offered no reason for the omission of their

"retaliation" claims from their earlier complaints. In addition,

Appellants have yet to offer any short and plain statement, as

required by Fed. R. Civ. P. 8, to support the paradigm elements of

a retaliatory discharge claim, see. Cooper v .__City— of— North

Olmstead. 795 F.2d 1265, 1272 (6th Cir. 1986), and Appellants have

not and cannot articulate any basis for a claim that their ability

to enforce their claimed contract rights was in any way impaired

or impeded — a necessary element for a §1981 enforcement claim.

See. Carter v. South Central Bell, 912 F.2d 832, 840 (5th Cir.

1990), cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2916 (1991); Overby v..Chevron

U.S.A.. Inc.. 884 F.2d 470, 473 (9th Cir. 1989). Appellants'

dilatory request for leave to amend should be denied.

20

In sum, Appellants were before the District Court and are

before this Court upon their First Amended Complaint. Their First

Amended Complaint alleges only that their "discharges" violated

§1981. Accordingly, the District Court properly dismissed

Appellants' claims pursuant to Patterson and this Court should

affirm.

B. APPELLANTS' "NEW" CLAIMS OF RETALIATION FAILED TO

STATE CLAIMS FOR WHICH RELIEF COULD BE GRANTED UNDER

42 U.S.C. §1981.

1. The Standard of Review

Roadway generally agrees with the standard of review

urged by Appellants. (Appellants' Brief, p. 3.) This Court

reviews dismissals de novo. all allegations in the complaint must

be taken as true and construed in a light most favorable to the

non-movant, and a motion to dismiss may only be granted if "it

appears beyond doubt that the plaintiff can prove no set of facts

in support of his claim which would entitle him to relief."

Connelly v. Gibson. 355 U.S. 41, 45, 46 (1957); Ana v. Proctor &

Gamble Co.. 932 F.2d 540, 544 (6th Cir. 1991). However, there are,

essentially, no "allegations in the complaint" at issue! The only

source of appellant's allegations of a claim of retaliatory

discharge is their memoranda responding to the District Court's

Show Cause Order.

2. Appellants' Limited Contentions

In their initial memorandum, Appellants stated their

claims as follows:

21

Rivers and Davison were discriminated against racially

for enforcing their contract.

(R. 259: 8/25/89 Appellants* Response to Show Case Order at p. 11.)

Appellants failed, however, to offer any factual allegations, nor

even any conclusory statements, that Roadway had impaired their

ability to enforce through the legal process their claimed contract

rights. (R. 259: 8/25/89 Appellants' Response to Show Cause

Order.) When Roadway raised that issue in its brief, Appellants

further refined and clarified their claims as follows:

...[T]he claim of denial of access to those forums is not

the claim here. The claim is that the discharges

themselves were infected by racial animus in the first

place. [Emphasis Added.]

(R. 263: 9/13/89 Appellants' Reply at p. 6.)

The District Court quickly disposed of Appellants*

contentions based upon that admission. The District Court reasoned

and concluded as follows:

Plaintiffs concede that "the claim of denial of access

to those [grievance and judicial] forums is not the claim

here." Plaintiffs' Reply at 6. Ironically, the denial

of access to such forums is precisely what is protected

under the "right to ... enforce contracts" provision of

§1981. Plaintiffs Rivers and Davison have been free to

grieve or litigate their discharges in the appropriate

forums. Thus, their complaint fails to allege that they

have been deprived of their §1981 rights. Accordingly,

the §1981 claims of Rivers and Davison will be dismissed.

(R. 2 64: 1/9/90 Memorandum and Order at p. 4.) The District

Court's conclusion is entirely consistent with the Supreme Court s

holding in Patterson. In Patterson, the Supreme Court stated.

The right to enforce contracts does not, however, extend

beyond conduct by an employer which impairs an employee's

ability to enforce through legal process his or her

established contract rights.

22

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 491 U.S. 164, 177-178. Later in

its Patterson opinion, the Supreme Court explained:

Nor is it correct to say that ... a breach of contract

impairs an employee's right to enforce his contract. To

the contrary, conduct amounting to a breach of contract

under state law is precisely what the language of §1981

does not cover. That is because, in such a case,

provided that plaintiff's access to state court or any

other dispute resolution process has not been impaired

by either the state or a private actor, see. Goodman v.

Lukens Steel Co.. 482 U.S. 656 (1987), the plaintiff is

free to enforce the terms of the contract in state court,

and cannot possibly assert, bv reason of the breach

alone, that he has been deprived of the same right to

enforce contracts as is enjoyed by white citizens.

[Emphasis Added.]

Id. at p. 183. By disavowing any denial of access to enforce their

claimed contract rights, Appellants failed to overcome Patterson.

3. Outline of the Arguments Presented

Appellant's argument takes a three-pronged approach:

(1) some retaliation claims survive Patterson (Appellants' Brief,

pp. 17-20); (2) retaliation after successful enforcement is as

actionable as retaliation which impairs or impedes enforcement

(Appellant's Brief, pp. 20-22); and (3) retaliation in the form of

a discharge, which itself is not actionable, is actionable

(Appellant's Brief, pp. 24-25). Roadway's response is likewise

three-fold:

(1) Only a claim that the employer, acting with a

racially-discriminatory motive, impaired or impeded

the employee's ability to enforce his employment

contract may survive Patterson;

(2) Retaliation, like any discriminatory conduct, is not

actionable alone; the employee must have been

deprived of the same right to enforce contracts as

is enjoyed by white citizens; and

23

(3) Because Title VII protects employees from

retaliation and discriminatory discharge it is not

necessary to interpret §1981 to duplicate that

protection, and, pursuant to Patterson. it should

not be so interpreted.

4• Overview; The Component Parts

As an overview, Roadway notes that Appellants are

essentially attempting to join two claims that are not actionable

under §1981, to come up with a claim that is actionable.

Appellants contend that they were discharged because:

(1) Their successful access to the grievance process;

and

(2) Their race.

§1981 is part of the federal law barring racial discrimination, and

a claim that an employee was discharged for accessing the grievance

process alone is not actionable under §1981. Likewise, a claim

that an employee was discharged for racial reasons is not

actionable under §1981. Yet Appellants combine those two claims,

assert that both reasons motivated Roadway, and apparently argue

that the sum is greater than the component parts. In commenting

on this form of "new math" the 5th Circuit in Carter v. South

Central Bell. 912 F.2d 832 (1990), cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2916

(1991) stated:

Finally, we have already held that discriminatory

discharge is no longer actionable under section 1981.

Were we to hold that section 1981 still encompasses

retaliatory discharge, we would be encouraging litigation

to determine what the employer's subjective motive was

when he fired the employee: was it to retaliate or

"merely" to discriminate? This would be pointless. Both

motives are egually invidious and the employee suffers

the same harm. Because section 1981 no longer covers

24

retaliatory termination, all suits for discriminatory

discharge must be brought under Title VII.

Carter, supra, at pp. .840-841. When claimant's allegations are

broken down to the component parts, the conclusion is inescapable

that claimant's allegations are not actionable under §1981.

5• Appellants Do Not Claim That Roadway Impaired

or Impeded Their Ability to Enforce Their

Claimed Contract Rights

Appellants' first line of argument is that some claims

of retaliatory discharge survive Patterson. In Christian v. Beacon

Journal Publishing Co. . unreported, No. 89-3822, 1990 U.S. App.

LEXIS 12080 (attached) (6th Cir. July 17, 1990), a panel of this

court disagreed holding:

We also read Patterson to suggest that claims of

retaliatory discharge may not be brought under section

1981. Retaliation and discharge do not involve the

"making and enforcement of contracts." See. Singleton

V. Kellogg Co.. No. 89-1077 [1989 U.S. App. LEXIS 17920

(attached)] (6th Cir. November 29, 1989) (per curiam).

Id. . slip op. at p. 8. See also Bohanan. Jr. v. United Parcel

Service, unreported, No. 90-3155, 1990 U.S. App. LEXIS 20154

(attached) (6th Cir. November 14, 1990) (Wellford, J. concurring:

"I would be disposed to treat retaliation as relating to the

'conditions of employment' covered clearly under Title VII and not

properly conduct 'which impairs the right to enforce contract

obligation' under §1981.") Similarly, other appellate courts have

held that retaliation claims do not survive Patterson. See. e ■g.,

Carter v. South Central Bell. 912 F. 2d 832, 840-841, (5th Cir.

1990) cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2916 (1991); Overby v. Chevron

U. S.A. . Tnc. . 884 F.2d 470, 473 (9th Cir. 1989). See also Hull v.

25

Cuyahoga Valiev Bd. of Educ., 926 F.2d 505, 509 (6th Cir.) (citing

and noting agreement with Overby, supra.)

Appellants' reliance upon the Supreme Court's reference

to Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co.. 42 U.S. 656 (1987) in its Patterson

decision, and upon dicta from other courts is misplaced. The

exclusion the Supreme Court may have carved out for a claim under

the Goodman case is very narrow. The Supreme Court, in Patterson,

stated:

Following this principle and consistent with our holding

in Runyan Tv. McCrary. 427 U.S. 160 (1976)] that §1981

applies to private conduct, we have held that certain

private entities such as labor unions, which bear

explicit responsibilities to process grievances, press

claims, and represent member[s] in disputes over the

terms of binding obligations that run from the employer

to the employee, are subject to liability under §1981 for

racial discrimination in the enforcement of labor

contracts. See. Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S.

656 (1987). The right to enforce contracts does not

however extend bevond conduct by an employer which

impairs an employee's ability to enforce through legal

process his or her established contract rights.

[Emphasis Added.]

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164, 177-178 (1989).

The Supreme Court clearly distinguished "certain private entities"

which bore "explicit responsibilities" for effectuating the redress

mechanism, from an employer whose conduct may be actionable only

if it "impairs an employee's ability to enforce through legal

process" his contract rights. Indeed, one court has held that

because actionable employer conduct is limited to that which

adversely affects the "legal process," such conduct does not extend

to include grievance procedures. Thompkins v. Dekalb County_Hosp_.

Auth., unreported, No. 1:87—cv-303-RLV, 54 FEP cases 1424, 1425

26

(attached) (N.D. Ga. February 7, 1990), aff'd, 916 F.2d 600 (11th

Cir. 1990).

Appellants have not alleged that Roadway possessed any

"explicit responsibilities" to see that their grievances got

processed, and in fact charged that responsibility, and the alleged

failure to carry out that responsibility, to the Union in their

Second and Third proposed Amended Complaints. (R. 68: 10/19/87

Second Motion to Amend Complaint, proposed Second Amended Complaint

attached; R. 124: 12/8/87 Motion for Leave to File Third Amended

Complaint, proposed Third Amended Complaint attached.) While there

may be an exception under Goodman, and Goodman may apply to

employers as well as unions (Appellants' Brief at p. 14), it only

applies to employers who "bear explicit responsibilities to process

grievances," and Roadway bore no such responsibility.5

Similarly, the assorted appellate court and district

court decisions relied upon by Appellants do not support their

cause. For the most part, Appellants acknowledge that the cited

cases hold that the retaliatory discharge claims considered were

5Unions represent and are to be the advocate for employees

through the grievance process; employers are naturally the

adversary. To open employers to claims of racial discrimination

every time they take an adversarial position would be to foster

significant litigation. Denial of access to the process of

grievance/arbitration should be the focus. For example, this court

has dealt with collective bargaining contracts that provide for

arbitration only by mutual consent of the employer and the union.

See, Groves v. Ring Screw Works. 882 F.2d 1081 (6th Cir. 1989),

rev'd., ill S. Ct. 498 (1990). If an employer refused to consent

to the process of arbitration based upon a racially-discriminatory

motive such refusal may be actionable in a claim similar to the

claim against the union in Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S.

656 (1987). No such actionable denial of access to the process of

grievance arbitration has occurred or can be claimed in this case.

27

not actionable. In particular, Carter v. South Central Bell. 912

F.2d 832, 840-841 (5th Cir. 1990), cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2916

(1991), Overby v. Chevron U.S.A.. Inc.. 884 F.2d 470 (9th Cir.

1989), and Dash v. Equitable Life Assur. Soc. of the U.S.. 753 F.

Supp. 1062, 1066-1067 (E.D. N.Y. 1990) emphasize that the alleged

conduct must have "impaired [the plaintiff's] ability to enforce

contractual rights either through... court or otherwise" Dash.

supra. , and that retaliation does not necessarily impede or impair

such ability to enforce. Appellants have never attempted to

explain how the claimed retaliatory discharges impaired or impeded

their access to legal process. At most, Appellants refer to the

general statement in McKnight v. General Motors Corp.. 908 F.2d

104, 111 (7th Cir. 1990), cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 1306 (1991) that

retaliation "is a common method of deterrence." The McKnight

court, however, went on to recognize the narrowness of the

exception under Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co.. 482 U.S. 656 (1987),

and rejected the claim of retaliatory discharge posed in that case.

Moreover, disparate treatment claims of intentional racial

discrimination are not actionable based upon judicial notice of

common knowledge; whether a claim is stated turns upon the specific

allegations offered by the plaintiff. In this case Appellants have

made no claim that their ability to enforce their claimed contract

rights was impaired or impeded.

Appellants place special reliance upon Von Zuckerstein

7-__Argonne National Laboratories. 760 F. Supp. 1310 (N.D. 111.

!99i) . Obviously, Von Zuckerstein is not controlling, but it also

28

does not support Appellants’ position and is distinguishable. In

von Zuckerstein. the plaintiffs alleged that the employer

"prevented and/or discouraged the plaintiffs from using the

available legal process to enforce the specific anti-discrimination

contract right." Id. at p. 1318. The court found only a "kernel

of a cognizable claim" in plaintiff's position and directed the

claim to trial. Id. at p. 1318. In this case, Appellants have not

and cannot allege that they were impaired or impeded from using the

available legal process.

Moreover, the Von Zuckerstein court went on to hold that:

Argonne would be exposed to §1981 liability for the

denial of access to this forum only if plaintiff sought

there to redress the alleged breach of the manual's anti-

discrimination provision.

Id. at p. 1319. A similar provision was at issue in the collective

bargaining agreement reviewed by the Supreme Court in Goodman v,

Lukens Steel Co.. 482 U.S. 656 (1987). In this case, however,

Appellants claimed that the collective bargaining agreement did not

contain an anti-discrimination provision. (R. 68: 10/19/87 Second

Motion to Amend Complaint, proposed Second Amended Complaint

attached at para. 7.) As the court in Von Zuckerstein noted,

without that "added dimension" any claim of denial of access by the

employer to the grievance process is "nothing more than a violation

of a term of its contractual agreement with plaintiffs, which is

not actionable under section 1981." Von Zuckerstein v. Argonne

National Laboratories. 760 F. Supp. 1310, 1318, 1319 (N.D. 111.

1991) , supra. . at pp. 1318, 1319, citing Hall v. County_gf_Cgok,

719 F. Supp. 721, 724-25 (N.D. 111. 1989). Appellants cannot

29

bridge that gap and Von Zuckerstein does not support the notion

that their claims are actionable; instead, Von Zuckerstein

highlights that Appellants are attempting to combine two claims

which clearly are not actionable to add up to an actionable claim.

While §1981 continues to extend to conduct by an employer

which impairs an employee's ability to enforce through legal

process his or her established contract rights, Appellants' claim

of a retaliatory discharge, which in essence remains a simple claim

of discriminatory discharge, fails to state a claim for which

relief can be granted. Appellants have no claim because their

ability to enforce their claimed contract rights was not impaired

or impeded.

6, Retaliation Alone is Not Actionable

Appellants' second and third arguments are more quickly

disposed of. Appellants' second argument is that the District

Court erred in distinguishing impaired access from post-outcome

retaliation and Appellants bemoan the notion that their right to

enforce protected by §1981 may protect only a "pro forma grievance

hearing" and the "purely formal right to go through the motions of

judicial or non-judicial dispute resolutions." (Appellants' Brief,

pp. 20-22.) Apparently, Appellants would have §1981 not only

provide access to the process but also guarantee the results, which

is far beyond what the Supreme Court held in Patterson when it

stated:

The right to enforce contracts does not. however, extend

beyond conduct by an employer which impairs an employees

30

ability to enforce through legal process his or her

established contract right. [Emphasis Added.]

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 491 U.S. 164, 177-178 (1989).

Roadway was not the ultimate determiner of the outcome of

Appellants' grievances; their grievances were ultimately decided

by the Toledo Local Joint Grievance Committee ("TLJGC"). (See, R.

306: 10/18/90 Findings and Facts and Conclusions of Law at p. 5.)

If Roadway's conduct did not impair or impede Appellants' "formal

right" to appear and have their case heard before the TLJGC, which

it did not, Roadway cannot be held liable under §1981 for

Appellants' dissatisfaction with the outcome. §1981 provides for

nothing more than the "removal of legal disabilities" from the

right to enforce. Id. at 178, quoting Runyon v. McCrary. 427 U.S.

160, 195, n. 5 (1976) (White, J. , dissenting). [Emphasis in

Original.]

Moreover, the distinction drawn by the District Court was

not, as Appellants imply, a categorical distinction between pre-

and post-grievance retaliation, but was simply a distinction

between claims which are not actionable and claims which may be

actionable premised upon Appellants' admission that "the claim of

denial of access to those [grievance and judicial] forums is not

the claim here." (R. 264: 1/9/90, Memorandum and Order at p. 4.)

A retaliatory discharge, alone, is no more actionable than a

discriminatory discharge because Appellants "cannot possibly

assert, by reason of the breach alone, that [they] have been

deprived of the same right to enforce contracts as is enjoyed by

white citizens." Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164,

31

183 (1989). Because Appellants admitted that their claim did not

encompass a claim of denial of access to the legal process their

bare allegation of a retaliatory discharge is not actionable and

this court should affirm the District Court's dismissal of their

claim.

7. Appellants Had the Opportunity to Pursue Their

Discriminatory Discharge Claims Under Title VII

Finally, Appellants' third argument addresses the

District Court's "bootstrapping" analysis; Appellants assert that

their allegations should be no less actionable simply because they

are in essence complaining of a discriminatory discharge. The fact

that the claimed actionable conduct does involve a discharge is

significant in light of the Supreme Court's admonition in Patterson

that courts "should be reluctant, however, to read an earlier

statute broadly where the result is to circumvent the detailed

remedial scheme constructed in a later statute." Patterson v.

McLean Credit Union. 491 U.S. 164, 181 (1989). As the Fifth

Circuit explained in Carter v. South Central Bell:

Title VII will protect an employee from retaliation.

[Citation Omitted.] As noted above, we should not

interpret section 1981 to duplicate that protection

unless the overlap of the two statutes is "necessary."

[See, Patterson. 491 U.S. at p. 181.] While an employer

who retaliates against an employee may discourage that

employee (or others) from using the legal process, the

employer has not impaired or impeded the employee's

ability to enforce his employment contract. While these

concepts have been construed to be synonymous [citations

omitted], we do not believe that it is "necessary" to do

so, [citation omitted].

Carter v. South Central Bell. 912 F . 2d 832, 840 (5th Cir. 1990),

cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 2916 (1991). Appellants are, undeniably,

32

trying to convert what had been for years and what continues to be

essentially claims of ' discriminatory discharge into actionable

claims under §1981, and seek not only to circumvent the detailed

enforcement procedures set forth in Title VII, but in fact a final

adverse disposition of their Title VII claims. Title VII provided

them an ample opportunity for relief. The District Court was

correct in seeing Appellants’ claims for what they are, claims of

discriminatory discharge which are not actionable, and the District

Court's dismissal of appellant's claims should be affirmed.

8. Summary

In sum, although Appellants have attempted to claim a

retaliatory discharge, they have never attempted to explain how

the alleged retaliation in any way impaired or impeded their right

to redress through the legal process. They can, in fact, not do

so. The District Court's dismissal of their purported claims under

§1981 should be affirmed.

C. APPELLANTS' CLAIMS CANNOT SURVIVE THE UNAPPEALED

SUMMARY JUDGMENT ORDER, ESTABLISHING THEIR

UNIMPAIRED ACCESS TO THE GRIEVANCE PROCESS.

In ruling on Roadway's Motion for Summary Judgment on

Appellants' §301 claims, the District Court stated:

Grievances were filed in each plaintiff's case and each

grievance was processed through final and binding

arbitration in accordance with the collective bargaining

agreement. The record in this case is voluminous. It

includes hundreds of pages of briefing and thousands of

pages of deposition testimony and exhibits. Despite this

extensive record, plaintiffs have failed to present any

evidence of arbitrariness, discrimination or bad faith

in the processing of their grievances. [Emphasis Added.]

33

(R. 224: 11/30/88 Memorandum and Order at pp. 2-3.) Appellants'

allegations of a retaliatory discharge, in their own words, seek

to "remedy their attempts to enforce the collective bargaining

contract." (R. 259: 8/25/89 Appellants’ Response to Show Cause

Order at p. 11.) In so seeking, they bring their claims squarely

within the District Court’s prior ruling, which was not appealed,

that they failed to present "any evidence of arbitrariness,

discrimination or bad faith in the processing of their grievances."

The disposition of Appellants’ §301 claims should bar them from

proceeding on any claim which must, necessarily, address the

impairment of their ability to enforce through legal process their

contract rights, because that prior determination upheld the

integrity of the grievance process.

Roadway is mindful that the Supreme Court in Goodman v.

Lukens Steel Co.. 482 U.S. 656, 661 (1987) held that §1981 had a

much broader focus than contractual rights and is part of the

federal law barring racial discrimination which involves a

fundamental injury to the individual rights of a person. Yet, in

Patterson, the Supreme Court clearly revisited the issue of the

breadth of §1981 and limited claims under "the same right — to

... enforce contracts" language of §1981 to the protection of a

legal process that would address and resolve "contract-law claims"

regarding "established contract rights." Patterson v. McLean

-Credit Union. 491 U.S. 164, 177 (1989). In McKniqht v. General

Motors Corp.. 908 F.2d 104, 112 (7th Cir. 1990), cert, denied. 111

S. c t . 1306 (1991) the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, while

34

still adhering to the notion that §1981 involved tort rights,

explained that if the rights protected by §1981 and its state

equivalents, were limited to contract rights, preemption may be an

issue.

While §301 preemption of other federal laws addressing

"contract-law claims" and "contract rights" does not stand on as

firm as ground as preemption of state laws that invade the scope

of §301, in this case the issue is whether a prior, unappealed

determination of the District Court upholding the integrity of the

grievance process bars Appellants' claims. Because the §1981 right

to enforce contracts does not "extend beyond conduct by an employer

which impairs an employee's ability to enforce through legal

process his or her established contract rights" and the District

Court found that:

(1) grievances were filed by each plaintiff;

(2) each grievance was processed through final and

binding arbitration in accordance with the

collective bargaining agreement; and

(3) plaintiffs have failed to present any evidence of

arbitrariness, discrimination or bad faith in the

processing of their grievances. (R. 224: 11/30/88

Memorandum and Order at pp. 2-3.)

Roadway asserts that Appellants cannot conceivably take the

position that Roadway engaged in any conduct which impaired their

ability to enforce their contract rights. That is, with those

facts conclusively and finally established, Appellants "can prove

no set of facts in support of [their] claim which would entitle

[them] to relief." Connelly v. Gibson. 355 U.S. 41, 45-46 (1957).

35

The District Court found that Appellants fully availed

themselves of the grievance process and the District Court upheld

the integrity of that process. Those findings preclude any claim

that Appellants' abilities to enforce their contractual rights were

impaired. The District Court's November 30, 1988 Memorandum and

Order supports its decision to dismiss Appellants' claims, and that

dismissal should be affirmed.

36

VII. CONCLUSION

Appellants' First Amended Complaint, the complaint upon

which the action below proceeded to a determination on the law and

the merits, claimed only a "discriminatory discharge." Such a

claim is not actionable under §1981 and the District Court properly

dismissed Appellants' §1981 claims. It is now far too late and it

would be extremely prejudicial to permit Appellants the opportunity

to attempt to plead some new, as yet not fully developed, claim

that may or may not survive scrutiny under Patterson v. McLean

Credit Union. 491 U.S. 164 (1989).

Certainly, Appellants' retaliation contentions discussed

briefly in memoranda below do not survive Patterson, because, as

Appellants admit, they are not pursuing claims, however they are

labeled, that they were denied access to any forum in which they

may have attempted to enforce their contract rights. Appellants

truly are pursing only breach of contract claims and such alleged

breaches alone cannot possibly satisfy their need to claim that

they have been deprived of the same right to enforce contracts as

is enjoyed by white citizens.

In fact, the District Court previously determined that

Appellants had full access to the dispute resolution mechanism, the

grievance process, and the District Court upheld the integrity of

that process. With those facts conclusively and finally

established in the record, Appellants can prove no set of facts

that would support a claim that Roadway impaired their ability to

enforce through legal process their contract rights.

37

For the foregoing reasons, defendant-appellee Roadway

Express, Inc. respectfully requests that the court affirm the

January 9, 1990 Memorandum and Order, the October 18, 1990 Findings