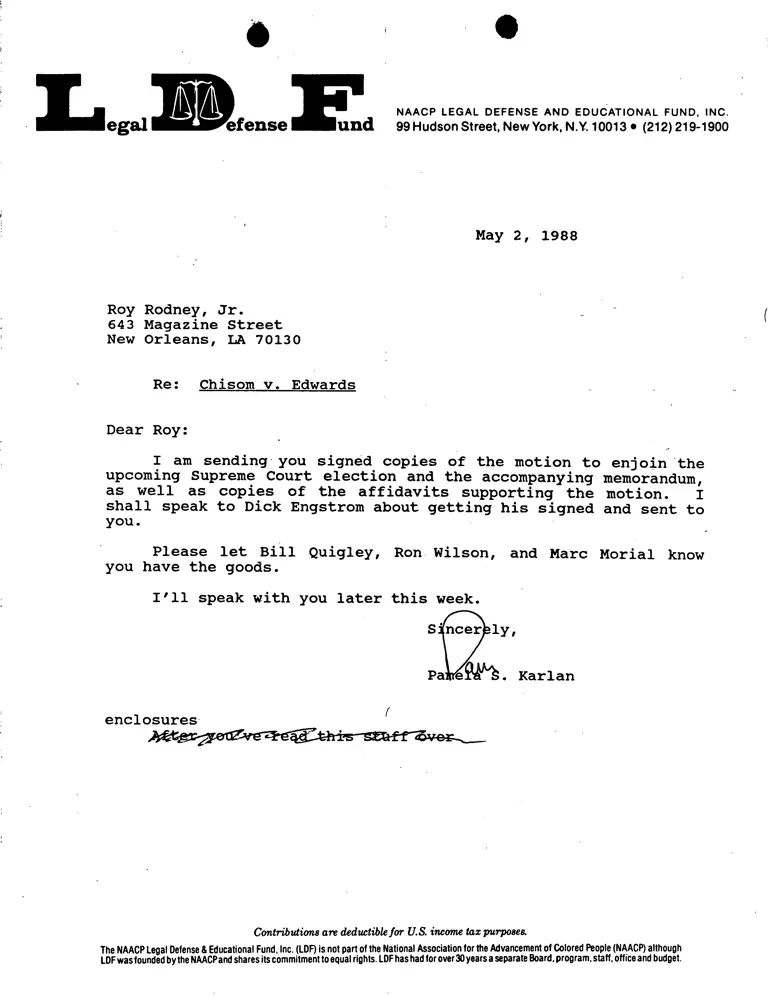

Correspondence from Karlan to Rodney

Correspondence

May 2, 1988

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Correspondence from Karlan to Rodney, 1988. d4138ca3-f211-ef11-9f89-0022482f7547. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8c3960e8-a288-43f9-9c20-32d54967eb6c/correspondence-from-karlan-to-rodney. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

egal

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

efense und 99 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y. 10013 • (212) 219-1900

May 2, 1988

Roy Rodney, Jr.

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

Re: Chisom v. Edwards

Dear Roy:

I am sending you signed copies of the motion to enjoin the

upcoming Supreme Court election and the accompanying memorandum,

as well as copies of the affidavits supporting the motion. I

shall speak to Dick Engstrom about getting his signed and sent to

you.

Please let Bill Quigley, Ron Wilson, and Marc Morial know

you have the goods.

I'll speak with you later this week.

enclosures

Contributions are deductible for U.S. income tax purpose&

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (L0F) is not part of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) although

LDF was founded by the NAACP and shares its commitment to equal rights. LDF has had for over 30 years a separate Board, program, staff, office and budget.