Motley Law Scholarship Award Announced by Legal Defense Fun

Press Release

March 22, 1972

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Motley Law Scholarship Award Announced by Legal Defense Fun, 1972. aa6958d1-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8c632724-a80b-46bf-8b9c-9ba62cb0c897/motley-law-scholarship-award-announced-by-legal-defense-fun. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

PressRelease B eae oa

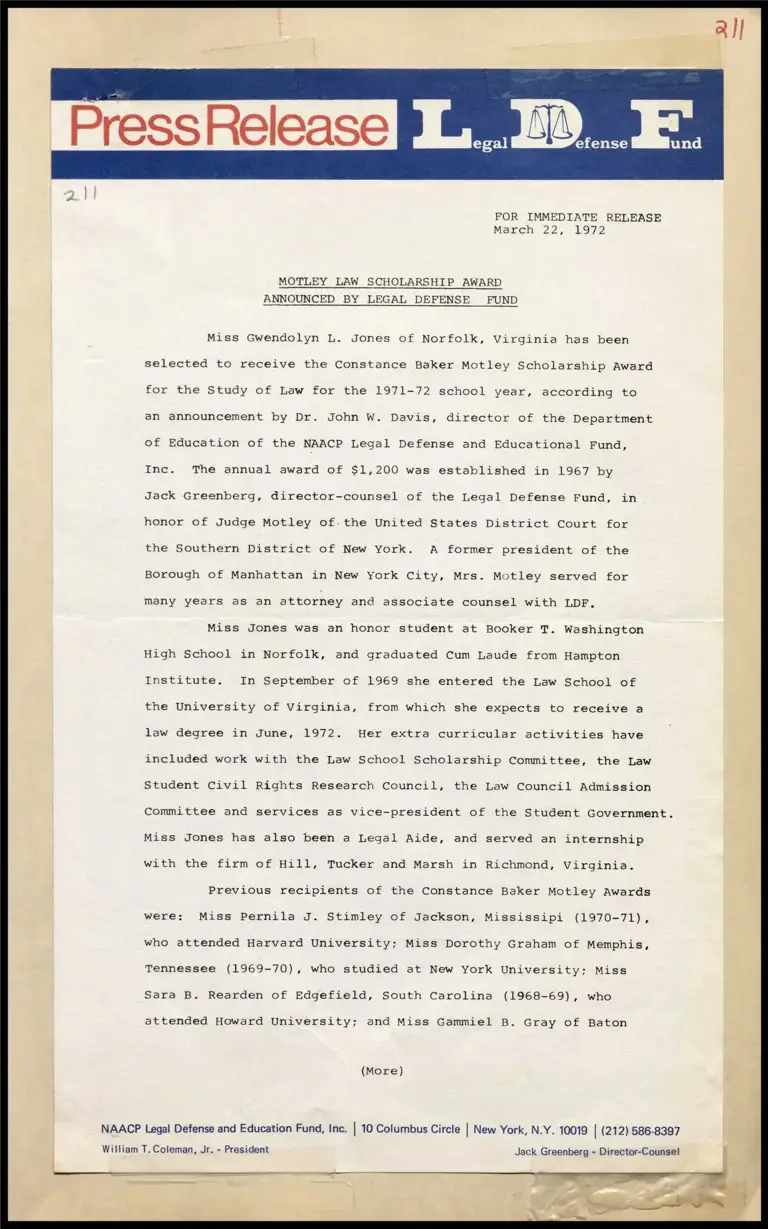

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

March 22, 1972

MOTLEY LAW SCHOLARSHIP AWARD

ANNOUNCED BY LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

Miss Gwendolyn L. Jones of Norfolk, Virginia has been

selected to receive the Constance Baker Motley Scholarship Award

for the Study of Law for the 1971-72 school year, according to

an announcement by Dr. John W. Davis, director of the Department

of Education of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. The annual award of $1,200 was established in 1967 by

Jack Greenberg, director-counsel of the Legal Defense Fund, in

honor of Judge Motley of.the United States District Court for

the Southern District of New York. A former president of the

Borough of Manhattan in New York City, Mrs. Motley served for

Many years as an attorney and associate counsel with LDF,

Miss Jones was an honor student at Booker T. Washington

High School in Norfolk, and graduated Cum Laude from Hampton

Institute. In September of 1969 she entered the Law School of

the University of Virginia, from which she expects to receive a

law degree in June, 1972. Her extra curricular activities have

included work with the Law School Scholarship Committee, the Law

Student Civil Rights Research Council, the Law Council Admission

Committee and services as vice-president of the Student Government.

Miss Jones has also been a Legal Aide, and served an internship

with the firm of Hill, Tucker and Marsh in Richmond, Virginia.

Previous recipients of the Constance Baker Motley Awards

were: Miss Pernila J. Stimley of Jackson, Mississipi (1970-71),

who attended Harvard University; Miss Dorothy Graham of Memphis,

Tennessee (1969-70), who studied at New York University; Miss

Sara B. Rearden of Edgefield, South Carolina (1968-69), who

attended Howard University; and Miss Gammiel B. Gray of Baton

(More)

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. | 10 Columbus Circle | New York, N.Y. 10019 | (212) 586-8397

William T. Coleman, Jr. - President Jack Greenberg - Director-Counsel

Bia

Rouge, Louisiana (1967-68), who completed her studies at

Louisiana State University.

For further information contact: Dr. John W. Davis or

Ed Gant at 586-8397

NOTE: Please bear in mind that the LDF is a completely separate

and distinct organization even though we were established

by the NAACP and those initials are retained in our name.

Our correct designation is NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc., frequently shortened to LDF.