Campbell v. Gadsden County District School Board Brief for Plaintiff-Appellee Cross Appellant

Public Court Documents

August 14, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Campbell v. Gadsden County District School Board Brief for Plaintiff-Appellee Cross Appellant, 1975. 303c27b8-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8c73713c-abe9-429c-9fcf-c436b004a048/campbell-v-gadsden-county-district-school-board-brief-for-plaintiff-appellee-cross-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

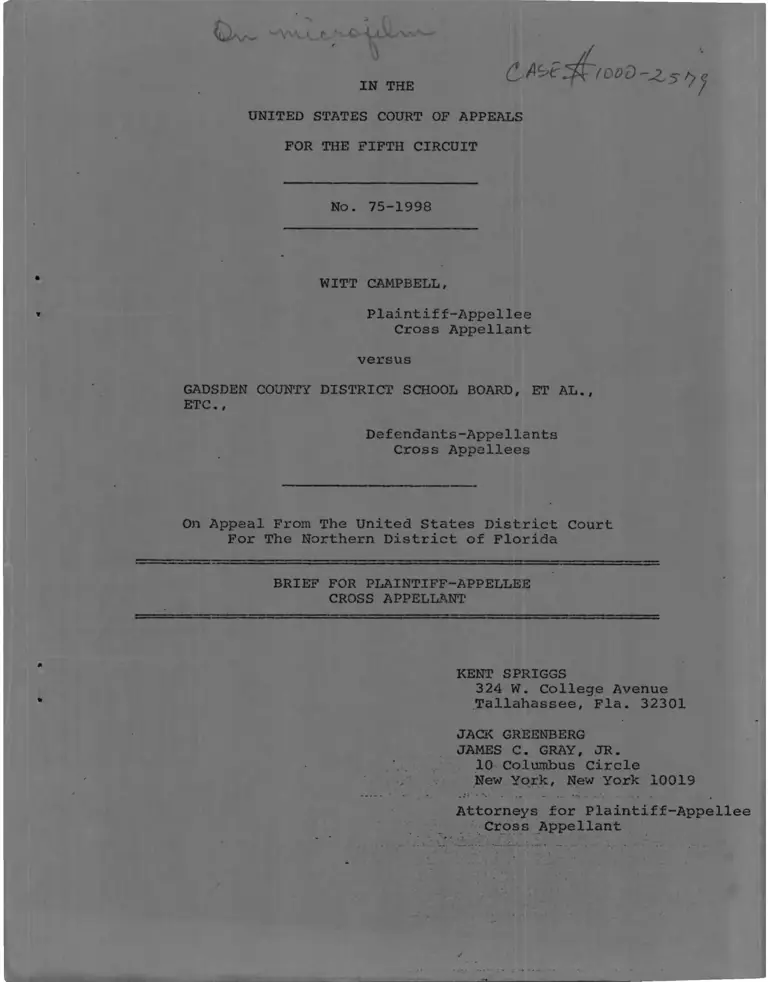

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

IN THE V

No. 75-1998

WITT CAMPBELL,

Plaintiff-Appellee

Cross Appellant

versus

GADSDEN COUNTY DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL.,

ETC. ,

Defendants-Appellants

Cross Appellees

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Northern District of Florida

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE

CROSS APPELLANT

KENT SPRIGGS

324 W. College Avenue

Tallahassee, Fla. 32301

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES C. GRAY, JR.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellee

Cross Appellant

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 75-1998

WITT CAMPBELL,

Plaintiff-Appellee

Cross Appellant

versus

GADSDEN COUNTY DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL.,

ETC. ,

Defendants-Appellants

Cross Appellees

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Northern District of Florida

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY LOCAL RULE 13(a)

The undersigned,counsel of record for plaintiff-

appellee, cross appellant certifies that the following listed

parties have an interest in the outcome of this case. These

representations are made in order that Judges of this Court

may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal pursuant

to Local Rule 13(a) : .. - - ... - .....

1. The original plaintiff who commenced this action in

1973 was Witt Campbell.

2. Plaintiff Campbell commenced this action as a class

action pursuant to Rule 23 F.R.C.P. but the district court

ruled that the action could not be maintained as a class

action.

4. The defendants are the Gadsden County Board of

Education (Florida), M.D. Walker, Superintendent, and

Edward Fletcher, Cecil Butler, C.W. Harbin, Jr., Will I.

Ramsey, Sr., and Randolph Greene, members of the Gadsden

County Board of Education.

Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellee

Cross Appellant

-2-

INDEX

Issues Presented For Review

by the Cross Appeal .........................

Procedural Statement of the Case ..............

Plaintiff's Statement of the Facts ............

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court Properly

Exercised Its Jurisdiction

Over the Defendants .................

II. The District Court Properly

Held That Plaintiff was Demoted

and that His Demotion and Non

reappointment Were In Violation

of the Singleton Requirements .......

III. The District Court Properly

Awarded Plaintiff a Reasonable Attorney's Fee ...................

IV. The District Court Properly

Ordered Plaintiff's Re

appointment to a Principalship ......

Cross Appeal

V. The District Court Erred in

Not Finding a Pattern and

Practice of Racial Discrimination ....

VI. The District Court Erred in

Not Awarding Plaintiff Back

Pay and Other Equitable

Monetary Relief .....................

CONCLUSION ....................................

Page

1

2

3

13

17

22

23

24

26

28

-i-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Aurora Education Ass'n East v. Board of

Education of Aurora Public School

District No. 131 of Kane County, 111.,

490 F . 2d 431 (7th Cir. 1974) ..................... 13

Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 416

U.S. 696 (1974) .................................. 23

Brooks v. Beto, 366 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. 1966) .......... 25

Campbell v. Masur, 486 F.2d 554 (5th Cir. 1973) ..... 13

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board

of Educ., 364 F . 2d 189 (4th Cir. 1966) .......... . 25

City of Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 U 0S. 507 (1973) .... 13, 14, 15

District of Columbia v. Carter, 409 U.S. 418 ........ 15

Haney v. County Board of Educ. of Sevier

County, 429 F.2d 364 (8th Cir. 1970) .... ......... 25

Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School

District, 427 F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1970),

cert. den. 400 U.S. 991 (1971) ................... 26

Harper v. Kloster, 486 F.2d 1134 (4th Cir. 1973) .... 14

Hines v. D'Artois, 383 F.Supp. 184, 190

(W.D. La. 1974) ........................... . 15

Jackson v. Wheatley Sch. Dist. No. 28,

430 F . 2d 1359 (8th Cir. 1970) .................... 25

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1 Denver, Colo.,

413 U.S. 109 (1973) ............................ . 25

Lee v. Macon County Board of Educ., 453 F.2d

1104 (5th Cir. 1971) .................... ......... 20

Lee v. Macon County Board of Educ. (Florence)

456 F . 2d 1371 (5th Cir. 1972) .................... 20

McCurdy v. School Board of Palm Beach

County, Florida, 367 F.Supp. 747

(S.D. Fla. 1973) 388 F.Supp. 599

(1974), aff'd per curiam 509 F.2d

540 (5th Cir. 1975) ........................ ...... 23

-ii-

Page

Maybank v. Ingraham, 378 F.Supp. 913

(E.D. Pa. 1974) 16

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) .............. 14

Moore v. Board of Educ. of Chidester Sch.

Dist., 448 F . 2d 709 (8th Cir. 1971) ........... 25

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc.,

390 U.S. 400 (1968) 22

North Carolina Teachers Assn v. Ashboro

City Board of Educ., 393 F.2d 736

(4th Cir. 1968) 25

Northcross v. Board of Educ., 412 U.S. 427(1973) 22

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,

494 F .2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974) .................. 26

Rolfe v. County Board of Educ. of Lincoln

County, 391 F.2d 77 (6th Cir. 1968) ........... 25

Singleton v. Jackson Separate Mun. Sch.

Dist., 419 F .2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert. den. 396 U.S. 1032 (1970) ........... 17, 18, 19, 20, 23

Smith v. Board of Educ. of Morrilton Sch.

Dist. No. 32, 365 F.2d 770

(8th Cir. 1966) ............................... 20

Sterzing v. Fort Bend Ind. School District,

496 F .2d 92 (5th Cir. 1974) ............... '....- • 14

United Farmworkers of Florida Housing

Project Inc. v. City of Delray Beach,

Fla., 493 F . 2d 799 (5th Cir. 1974) ............ 14

U.S. v. Jefferson County Board of Educ.,

372 F . 2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966) .................. 25

U.S. v. Wakulla County*........................... 20

Wall v. Stanly County Board of Educ.,

378 F .2d 275 (4th Cir. 1967) .................. 26

Williams v. Albemarle County Bd. of Educ.,

485 F . 2d 232 (4th Cir. 1973) .................. 18

-iii-

Page

Statutes:

20 U.S.C. § 1617 ........

28 U.S.C. § 1331 ........

28 U.S.C. § 1343 ........

42 U.SoC. § 1981 ........

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ........

42 UoS.Co § 1985 ........

F.R. Ap. P. 52(a) .......

Constitutional Provisions:

Thirteenth Amendment ....

Fourteenth Amendment ....

22

16

13

13, 15, 16

14, 15, 16

13, 16

18, 25

13, 16

13, 16

-iv

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 75-1998

WITT CAMPBELL

Plaintiff-Appellee

Cross Appellant

versus

GADSDEN COUNTY DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL.,

ETC.,

Defendants-Appellants

Cross Appellees

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Northern District of Florida

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE

____ CROSS APPELLANT

Issues Presented For Review

By the Cross Appeal________

1. Did the District Court err in not making a finding

that a pattern and practice of racial discrimination had been

shown and in finding that plaintiff's demotion was not part

of any pattern and practice? • .. - ... .

2. Did the District Court err in not awarding plaintiff

back pay and other equitable monetary relief?

-1-

Procedural Statement of the Case

Appellee-Cross-Appellant Campbell (hereinafter

referred to as "plaintiff Campbell") adopts the Statement

of the Case set forth on pages 1 to 3 of the Brief of

Defendants-Appellants Cross-Appellees (hereinafter re

ferred to as "defendants").

-2-

PLAINTIFF'S STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

a. Plaintiff's Demotion

Plaintiff Campbell is a black administrator

who has been employed by the Gadsden County Board of

Public Instruction since 1934. He has been certified

as an elementary and secondary school principal since

1952. [Finding of Fact (F.F.) 1] In the 1969-70

school year, plaintiff had thirty years of experience

as an administrator in the Gadsden County school system

and was the senior administrator in the system. [Plain

tiff's Exhibit (P.X.) 5]

The Gadsden County School District historically

operated a dual school system with racially segregated

faculties and student bodies up until the commencement

of the 1970-71 school year. Pursuant to an order by

the United States District Court for the Northern District

of Florida in the case of United States v. Gadsden County

School District, TCA-1616, enjoining further maintenance

of the dual school system, the defendant district desegre

gated its system in August 1970. Under the dual system,

the school district operated five white secondary schools

(four with senior high school grades) but only two black

secondary schools despite the fact that black students

comprised more than 50% of the student body throughout

the system. Of the schools - both secondary and elementary

none of the white schools had black principals or assistant

principals, but two of the black schools (Springfield

and Stewart Street) had white principals. (P.X. 5)

Prior to the desegregation of the Gadsden

County system, plaintiff Campbell was the principal

of Stevens Elementary School. As principal of Stevens,

plaintiff had responsibility for selecting and hiring

faculty, making teacher assignments, presiding over

faculty meetings and ceremonial occasions and for the

general operation of the school. (F.F. 9)

As a result of the desegregation of the system,

the Stevens Elementary School was phased out and the

1/number of principalships in the system reduced. (F.F. 4)

In August 1970, plaintiff was reassigned from

his position as a principal to an assistant principal's

position. Plaintiff objected to his reassignment.

(F.F. 5) Plaintiff was assigned as assistant principal

to Chattahoochee High School. As assistant principal

of Chattahoochee High School, plaintiff had no responsi

bility for selecting and hiring faculty, making teacher

assignments and presiding over faculty meetings and cere

monial occasions (F.F. 9) In September of 1973, there

were fewer students enrolled at Chattahoochee High School

than there had been at Stevens Elementary School when plain

tiff was principal. (F.F. 10)

1/ As part of its dismantling of the dual school system,

the Gadsden County school board also changed the names of

five formerly all black schools; no white schools were

similarly changed.

-4-

The position of principal is generally more

prestigious than the position of assistant principal

regardless of whether the comparison is made on or between

the elementary, junior high or high school levels. (F.F. 11)

The salary range for principals is higher than the salary

range for assistant principals. (F.F. 12)

Although plaintiff did not suffer a loss in

salary in the 1970-71 school year when his 1970-71

assistant principal's salary is compared with his 1969-70

principal's salary, a comparison of his subsequent salaries

with those of another principal with similar seniority

shows that he did suffer a loss in income over the succeed

ing years. Principal William Grice who retained his ele

mentary school principalship and had in 1969-70 twenty-nine

(29) years of seniority compared with plaintiff's thirty

(30) years earned the following amounts more than plaintiff:

in 1971-72 - $200, in 1972-73 - $500, and in 1973-74 - $500.

In 1970-71, however, plaintiff earned $300 more than Principal

Grice. (PX.5)

In August 1970, the Gadsden County school system

had not developed non-racial objective criteria, to be used

in selecting staff members for dismissal or demotion, and the

system and defendants have never developed such criteria.

The school system did not utilize objective and reasonable

non-discriminatory standards to compare the members of the

pre-desegregation order principal population.in order to

select from among all the principals which ones were to be

displaced in effecting the necessary reduction in the numbers

of principals. (F.F. 7)

-5-

At the time that plaintiff was displaced from

his principalship, he was the senior administrator in

the system. Plaintiff has been assigned less respon

sibility as assistant principal of Chattahoochee High

School than he had as principal of Stevens Elementary

School. (F.F. 8) In the crucial year of integration

when plaintiff was demoted, six new principals were

brought into the system.

In addition, in the 1970-71 school year, Charles

Boyd assumed the Munroe Elementary principalship for the

first time, and Corbin Scott assumed the Southside Ele

mentary principalship for the first time. Both new

principals were white. (P.X. 5)

In the fall of 1971 Leslie Jones, a white,

assumed the principalship of Gretna Elementary School

for the first time and his former position was assumed

by the former principal of Gretna. The combined seniority

of these two principals was twelve (12) years compared

to plaintiff's thirty-two (32) years. 'V"

Since 1970, there have been at least three

principal vacancies at the junior high school level for

which plaintiff was qualified.

Plaintiff has never been offered reassignment

as principal of any school — elementary, junior high or

high — since his displacement in August 1970. He remains

duly certified to be a principal on either the elementary

or secondary level.

-6

b . Statistical and Other Evidence of Racial

Discrimination

Plaintiff introduced other evidence to show

that his dismissal was part of a pattern and practice

of racial discrimination. This evidence shows not only

that other black administrators were demoted without

objective criteria but also that whites have enjoyed

prior to desegregation and also afterwards preferential

employment treatment in the Gadsden County public school

system.

In the fall of 1970, defendants consolidated

the black and white high schools in the Havana area,

turning the previously black Northside High School

building into a middle school. The former principal of

Northside, John Williams, a black, was reassigned as

principal of the middle school while a white was made

principal of the High School. The white, Leslie Jones,

had been prior to desegregation the assistant principal

of an elementary school. No non-racial objective cri

teria were used in demoting an experienced black high

school principal to a middle school position and promoting

an elementary school assistant principal for the high

school principalship. (P.X. 5)

Mr. Freddie Andrews was moved from his elementary

school principalship in 1969 to the assistant principalship

of a senior high school. (P.X. 4 and 5) In 1970 he was

reassigned from his line administrative position to the

county staff against his will.

-7-

Two other black principals were assigned to

assistant principalships in the wake of desegregation.

In the fall of 1970, Verdell Hamilton was demoted from

a high school principalship to a high school assistant-

ship. In the fall of 1971, Pugh Young was demoted from

an elementary school principalship to a junior high

school assistantship.

-8-

Despite the fact that the student body is and

has been predominantly black (presently approximately 78%

black), the school system has lowered black faculty employ

ment from 61% to 48% and maintained it at that level (ap

proximately 50%). (P.X's 8 and 13)

From 1968 until the present, sixteen persons

have been newly hired as principals or assistant principals

in the system. Of these sixteen, fifteen were white. Of

the fifteen whites, ten were brought in from outside of

the system and were entirely new to Gadsden County. (P.X. 1)

Nine of these fifteen white administrators were not properly

certified in supervision and administration when they were

selected and none of them had any previous experience in

administration. (P.X's 2 and 3) During this period, there

have been highly qualified blacks already in the system who

had a number of years of experience within the system and

proper certification. They however, were passed over.

Among these black candidates were Robert Love, Robert Green,

Harold Palmer, and Ms. Luree Houston. None was selected

for a principalship or assistant principalship. Messrs.

Love, Green and Palmer all have long records of service

with the defendant system and were at all relevant times

properly certified in supervision and administration. Ms.

Houston had like plaintiff Campbell served with distinction

as an elementary principal in the Gadsden system prior to

desegregation. She was displaced to a non-principal position

and has never been offered a principalship. She had twelve

(12) years experience in administration in Gadsden County

-9-

and one and a half years experience as a principal.

(P.X's 2 and 3)

Since 1968, fourteen (14) assistant principal-

ships have been filled. Of the fourteen persons filling

these positions eleven (11) have been white and only

three (3) black. All eleven whites were brought in from

outside the system, while all three blacks were former

principals who were demoted. (P.X. 2)

Because there were more white secondary schools

under the dual school system than black (five to two)

even though blacks comprised more than half the student

body, there were to begin with more white secondary school

principals. By the 1974-75 school year, however, the

number of secondary school principalships had increased

from seven to nine but the number of black secondary

principals remained frozen at two. (P.X. 5)

The teacher employment statistics show that

white teachers have also received better treatment in

hiring and retention than blacks. In 1964-65, prior to

the desegregation efforts, black teachers made up 61%

of the teachers in the system. By 1970-71, the first

year of integration, that percentage had dropped to 48%

and has remained at approximately 49% since. (P.X. 8)

A significant factor in this drop in percentage was the

failure of the school district to rehire black teachers

in 1969-70 and 1970-71. Teachers 'who are not recommended

by their principals or who are not endorsed by the superin

tendent if recommended by their principal are not entitled

-10-

to be rehired. For 1959-70, thirty-six (36) teachers did

not receive recommendation or endorsement. Of those

thirty-six, twenty-nine (29) or 80% were black; seven (7)

were white. The following year, sixteen (16) were not

recommended for rehire or for continuing contract after

the third year. Of these sixteen, thirteen (13) or 80%

were black; three (3) were white. (P.X. 6)

The hiring statistics show that the school

system has maintained the faculty balance at approximately

2/

50% despite the high turnover in white teachers through

hiring two to three times as many whites. Plaintiff's

Exhibit 7 shows the following:

New Teachers• Year % BlackWhite % Black

1972-73 55 15 21.5

1973-74 40 20 33.3

1974- 57 16 21.9

Finally, at the county staff level, whites have

received better employment opportunities than blacks. Prior

to desegregation in 1968-69, only two of the seventeen (17)

county staff professionals were black, representing 11.8%.

In 1970-71, the percentage had increased to 13.6% by adding

one more black to the county staff. The number of whites

2/ For instance, of those who. entered the system in 1972,

there were 55 white teachers and 15 black. At the end of the

first year, 64% of the white teachers (20) remained in the

system, compared to 80% (12) of the blacks. By the end of

two years 44% of the whites (24) remained while 73% of the

blacks (11) remained).'

-11-

had increased in the meantime by four. The one black

added, Mr. Freddie Andrews, was like plaintiff a former

principal who had been demoted to assistant principal

before being placed on staff. (P.X. 5 and 10) Of the

fifteen (15) persons who have assumed county staff

positions since 1970, only five (5) have been black.

(P„X. 10)

-12-

A r g u m e n t

i

The District Court Properly

Exercised Its Jurisdiction

Over The Defendants________

This action was brought against the Gadsden

County District School Board, the Superintendent of

Schools and the'five individual Board members alleging

a deprivation of rights secured by 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981,

1983 and 1985 and the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amend

ments .

1983 Jurisdiction

The United States Supreme Court's decision

in Bruno v. City of Kenosha, 412 U.S. 507 (1973) held

that a municipality is not a "person" for the purposes

of § 1983 jurisdiction. Admittedly, therefore, juris

diction does not exist as to the school board under

§ 1983 to the extent that it is within the nature of1/a municipality.

Jurisdiction under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 does,

however, clearly exist as to the defendant Superintendent

and board members who are clearly "persons" within the

meaning of the statute. Were they not "persons'" § 1983

would be stripped of any effective meaning inasmuch as

it is directed to individuals acting "under color of law."

3./ See Campbell v. Masur, 486 F.2d 554 (5th Cir. 1973) ; but see Aurora Education Ass'n East v. Board of Education

of Aurora Public School District No. 131 of Kane County, 111.,

490 F .2d 431 (7th Cir. -1974).

-13-

In Moor v. County of Alameda, 411 U.S. 693 (1973),

decided the same term as Kenosha, the Supreme Court

noted that ''substantial federal causes of action" were

stated against the individual county employees, despite

the fact that the county itself was not amenable to suit

under § 1933.

This Court has stated that while a city and

other governmental agencies may not be proper parties

under § 1983 "the individually named city council members

and the other named individual defendants are clearly

proper parties under . . . § 1983 . . .." United Farm

workers of Florida Housing Project, Inc, v. City of

Delray Beach, Fla., 493 F.2d 799 (5th Cir. 1974). See

also, Sterzing v. Fort Bend Ind. School District, 496

F . 2d 92 (5 th Cir. 1974). The Fourth Circuit in Harper

v. Kloster, 486 F.2d 1134 (1973), reached a similar

result.

In Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S- 167 (1961), the

Supreme Court specifically held that city officials are

proper defendants under § 1983 even though the city

itself was not a "person" for the purposes of a damage

action. 365 U.S. 192. The Kenosha decision, which

clarified that the Monroe ruling extended to equitable

actions as well as actions at law, did not however ex

pand the scope of exclusion from suit to city officials.

-14-

§ 1981 Jurisdiction Lies Against the Board

and Individual Defendants_________________

Unlike § 1983, 42 U.S.C. § 1981 provides

jurisdiction against the school board as a corporate

entity in the nature of a municipality as well as

against the school board members and the superintendent.

§ 1981 was was originally enacted as § 1 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1866 in furtherance of the Thirteenth

Amendment and was subsequently reenacted in light of

the additional authorization of the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

The Supreme Court, during the same term that

it decided Kenosha, pointed out the distinction that

lies between an action brought pursuant to the 1866

Civil Rights Act and one brought pursuant to § 1983.

District of Columbia v. Carter, 409 U.S. 418 (1973).

The 1866 Act is focused on enabling non-white citizens

to enjoy the same rights enjoyed by white citizens.

Its provisions, now codified as §§ 1981 and 1982, are

"not 'a mere prohibition of state laws establishing or

upholding' racial discrimination . . . but, rather, an

'absolute' bar to all such discrimination, private as

well as public, federal as well as state.” 409 U.S.

422.

Courts have recognized that employment dis

crimination actions under § 1981 may be successfully

maintained against "municipal" defendants as well as

individual official defendants. See Hines v. D'Artois,

15-

383 F.Supp. 184, 190 (W.D. La. 1974); Maybank v. Ingraham,

378 F.Supp. 913 (E.D. Pa. 1974).

S 1331 Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction was also asserted against the

school board under 28 U.S.C. § 1331 asserting that the

nature of relief sought by plaintiff met the requisite

jurisdictional amount.

The instant matter raises questions arising

under the Constitution and laws of the United States:

the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments and 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1981, 1983 and 1985.

-16-

II

The District Court Properly

Held That Plaintiff Was

Demoted and That His Demotion

and Non-reappointment Were

In Violation Of The Singleton

Requirements__________________

This Court announced the Singleton standards

in December 1969. 419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1970). Ac

cording to those standards, all future displacements

of teachers and administrators were to be conducted

in a manner designed to provide black educators with

certain procedural protections from discriminatory

treatment by school districts that had historically

maintained racially segregated school systems. Plain

tiff was displaced nine months later in a manner devoid

of any of those procedural safeguards.

Plaintiff Was "Demoted"

In Singleton, this Court specifically defined

what would constitute a "demotion" as follows:

"Demotion" as used above includes any

re-assignment (1) under which the staff

member receives less pay or has less re

sponsibility than under the assignment he

held previously, (2) which requires a

lesser degree of skill than did the assign

ment he held previously, or (3) under which the staff member is asked to teach

a subject or grade other than one f<pr

which he is certified or for which he has

had substantial experience within a rea

sonably current period. 419 F.2d 1218 (emphasis added)

Plaintiff's assignment from principal to assistant

principal - "desegregation specialist" was a demotion within

-17-

the meaning of Singleton. The district court found as

fact that plaintiff's new position involved lesser

responsibility. (F.F. 8) The court found that the

salaries of principals were generally higher than

those of assistant principals. (F.F. 12) Although,

as the court noted, plaintiff suffered no immediate

loss of salary the first year, he did incur a loss

in the succeeding year when compared to principal

William Grice.

The court's finding of fact that the new

position entailed less responsibility is not "clearly

erroneous" within the meaning of Rule 52(a) F.R.A.P.

and defendants have not argued that the court's find

ing was wrong.

The court's conclusion of law that plain

tiff's reassignment was therefore a demotion is clearly

correct. See also Williams v. Albemarle County Bd. of

Educ.. 485 F .2d 232 (4th Cir. 1973).

Defendants Failed To Comply

With The Singleton Require-

ments in Demoting Plaintiff

Although subject to the provisions announced

JJ • .in Singleton, defendants did not prepare objective 4

4 / 3. If there is to be a reduction in the

number of principals, teachers, teacher-

aides, or other professional staff employ

ed by the school district which will result

in a dismissal or demotion of any such

staff members, the staff member to be

dismissed or demoted must be selected on

the basis of objective and reasonable

non-discriminatory standards from among all the staff of the school district"

18

criteria for determining which principals were to be

demoted in order to achieve the necessary reduction

in the number of principals in the system. The

district court found that the school board had never

developed written, objective, non-racial criteria to

be used in connection with demotion and dismissal.

(F.F. 7) There is no evidence in the record which

indicated that plaintiff was compared with any other

principal to determine who was to be demoted.

The defendants 1 failure to undertake a com

parison of principals based on objective criteria is

a per se violation of Singleton denying plaintiff the

— JL/procedural protections assured by that decision. The

only apparent basis for demoting plaintiff appears to

be the closing of his former chool. It was exactly

such an approach which the Eighth Circuit deplored in 5

4/ continued

Prior to such a reduction, the school

board will develop or require the develop

ment of nonracial objective criteria to

be used in selecting the staff member who

is to be dismissed or demoted. These

criteria shall be available for public

inspection and shall be- retained by the

school district. The school district

also shall record and preserve the

evaluation of staff members under the

criteria. Such evaluation shall be made

available upon request to the dismissed

or demoted employee. 419 F.2d 1218 (emphasis added)

5 / Defendants cited the correct legal standard on pp. 12-13

of their Brief but in doing so demonstrate beyond question

that the District Court was right in finding an absence of

written standards. In place of the unequivocal command of

this Court the School Board states that the transfers were

-19-

the seminal teacher rights case of Smith v. Bd. of Educ.

of Morrilton School Dist. No. 32, 365 F.2d 770 (8th Cir.

1966). In that case, the defendants closed the Negro

school and discharged all the black teachers on the

theory that since their school was no longer operating

they were out of jobs. The Eighth Circuit rejected this

approach noting the inequitable burden placed on the

black teachers in the absence of a comparison of qualifica

tions on an objective basis.

Defendants Failed To Comply With

Singleton When They Filled Sub

sequent Principalships Within

The System With White Principals

The law is now clear within this Circuit that,

where a vacancy arises for which an educator displaced

during desegregation is qualified, that educator is

entitled to a preferential right of employment in the

position over new applicants of the opposite race.

_5 6VSingleton, supra at 1218; Lee v. Macon County Board of

Educ. (Muscle Shoals), 453 F.2d 1104 (5th Cir. 1971); Lee

5 / continued

in "strict conformity with the orders as set forth in

the case of United States v. Wakulla County . . .."

No standards are cited from that case. There were none.

6 / "In addition if there is any such dismissal

or demotion, no staff vacancy may be fill

ed through recruitment of. a person of a

race, color, or national origin different

from that of the individual dismissed or

demoted, until each displaced staff mem-

who is qualified has had an oppor

tunity to fill the vacancy and has failed

to accept an offer to do so." 419 F.2d 1218

(emphasis added)

-20-

v. Macon County Bd. of Educ. (Florence), 456 F.2d 1371

(5th Cir. 1972).

Plaintiff's many years of experience as a principal

demonstrate his qualifications as a principal. Not only

is he the senior administrator in the system, but he is

also certified for all levels — elementary, junior high

and high school principalships. Having been displaced

from his principalship in 1970, he should have been con

sidered for and offered each available principalship in

the system before any person from outside of the pre

desegregation principal population was offered it. The

school district did not do so.

Instead, in 1970-71 the school district filled

the Munroe and Southside Elementary schools with white

principals who had not been principals prior to desegrega

tion. In the fall of 1971, the school district appointed

Leslie Jones, a white to the principalship of Gretna Ele

mentary school for the first time. This was another filling

of a position for which plaintiff was qualified. The fact

that Jones' former position was assumed by the former prin

cipal of Gretna does not diminish the fact that plaintiff

could have equally filled the position. The two "swapped”

principals' combined seniority was twelve (12) years as

compared to plaintiff's thirty-two (32).

Plaintiff should have been offered the principal-

ships of the three junior high schools which have been

filled since the 1970 order. With his experience both as

-21-

as principal before desegregation and as an assistant

principal at the high school level afterwards and

with his secondary certification, plaintiff was

clearly qualified to assume those positions.

Ill

The District Court Properly

Awarded Plaintiff a Reasonable

Attorney's F e e _____________

The 1972 Emergency School AidAct, 20 U.S.C.

§ 1617, provides that:

Upon the entry of a final order by

a court of the United States against a

local educational agency, . . . for dis

crimination on the basis of race, color,

or national origin in violation of

title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, or the fourteenth amendment to the

Constitution of the United States as they

pertain to elementary and secondary educa

tion, the court, in its discretion, upon

a finding that the proceedings were nec

essary to bring about compliance, may allow

the prevailing party, other than the United

States, a reasonable attorney's fee as part

of the costs.

The Supreme Court in Northcross v. Board of Educa

tion , 412 U.S. 427 (1973); held that the prevailing plaintiff

should be awarded such fees "unless special circumstances

would render such an award unjust." The Court stated that

such plaintiffs were private attorneys general vindicating

national policy. The Court noted the similarity of the

statutory language to Title II of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 and cited its decision in Newman v. Piggie Park Enter

prises , Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968).

In Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 416 U.S. 696

-22-

(1974), the Supreme Court held that the Emergency School

Aid Act should be applied retroactively. While retro

active application is not an issue in this litigation,

the decision manifests the Supreme Court's strong policy

in favor of such awards.

IV

The District Court Properly

Ordered Plaintiff's Re

appointment to a Principal-

ship_____________________ ;_

The instant matter is almost identical in facts,

violations of law and the Constitution and relief ordered

to those detailed in McCurdy v. School Board of Palm Beach

County, Florida, 367 F.Supp. 747 (S.D. Fla. 1973). The

district court in granting plaintiff's preliminary injunc

tion ordered the removal of a white administrator who was

appointed to a principalship which plaintiff was entitled

to under the proper application of Singleton III supra.

The preliminary injunction was made permanent in 1974.

388 F.Supp. 599. This Court in March 1975 affirmed per

curiam the lower court's decision and orders. 509 F.2d

(5th Cir. 1975).

Similarly, the court should affirm the district

court's grant of reappointment to the plaintiff in the

instant matter.

-23-

Cross Appeal

V

The District Court Erred

In Not Finding A Pattern

and Practice of Racial

Discrimination__________

In the defendants' Brief, they state that "the

District Court found that "the transfer of the plaintiff

was not racially motivated." (Brief of Defendants-

Appellants Cross Appellees at p. 15). This is not

accurate. The court found that plaintiff's reassignment

was not the product of a pattern and practice of racial

discrimination. (F.F. 6) The court made no finding as

to whether or not a pattern or practice of racial dis

crimination independent of plaintiff's situation existed.

Plaintiff believes that the district court

erred in not finding that a pattern and practice of racial

discrimination had occurred and continues to occur and

in not finding that plaintiff's reassignment was part of

such pattern and practice. The matters cited in Part "b"

of Plaintiff's Statement of Facts demonstrate such a

pattern and practice. The demotion of other black principals,

the preferential hiring of whites as administrators, the

reduction through discharges and non-hiring of blacks in

the teaching ranks and the non-appointment of blacks to

the county staff creates a prima facie case which places

the burden of proof on the defendants. The statistical

and other data show that desegregation has resulted in a

disproportionate racial impact on black educators. Figures

-24-

speak and when they do, Courts listen." Brooks v. Beto,

366 F .2d 1, 9 (5th Cir. 1966).

The Courts have made it quite clear in teacher

retention cases arising out of desegregation of historical

dual school systems that when a disproportionate racial

impact is shown, the burden of proof shifts to the school

authorities and they must explain their actions by "clear

and convincing evidence." U .S. v. Jefferson County Board

of Educ., 372 F.2d 836, 895 (5th Cir. 1966). Accord,

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Educ., 364 F.2d

189, 192 (4th Cir. 1966); North Carolina Teachers Assn.

v. Ashboro City' Board of Educ., 3 93 F.2d 73 6, 743 and 745

(4th Cir. 1968); Rolfe v. County Board of Educ. of Lincoln

County, 391 F.2d 77, 80 (6th Cir. 1968); Moore v. Board of

Educ. of Chidester School Dist., No. 59, 448 F.2d 709, 711

(8th Cir. 1971); Jackson v. Wheatley School Dist._No■ 28,

430 F.2d 1359, 1363 (8th Cir. 1970); Haney v. County Board

of Educ. of Sevier County, 429 F.2d 364, 370-71 (8th Cir.

1970. See also Keyes v. School Dist. No.1 Denver Colorado,

413 U.S. 109 (1973).

In the instant matter, defendants failed to ex

plain in any manner the disproportionate impact. Under

these circumstances the district court's failure to enter

a finding of a pattern and practice was wrong and its

finding that plaintiff's demotion was not part of said

pattern and practice was "clearly erroneous" within the

meaning of Rule 52(a) of the Federal Rules of Appellate

Procedure.

-25-

VI

The District Court Erred

In Not Awarding Plaintiff

Back Pay and Other Equitable

Monetary Relief_____________

Plaintiff's earnings since desegregation were

at a minimum $900 less than those of William Grice, a

principal who retained his principalship and had comparable

seniority. Plaintiff also incurred as a result of his

demotion additional expense because he had to drive every

day an extra forty-four (44) miles to Chattahoochee. His

former position was in Quincy and subsequent principalship

vacancies arose in Quincy.

Back pay is an appropriate element of the equitable

relief to be granted a wrongfully demoted educator. Harkless

v. Sweeny Independent School District, et al., 427 F.2d 319,

324 (5th Cir. 1970); Wall v. Stanly County Bd. of Educ.,

378 F .2d 275, 276 (4th Cir. 1967).

In Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494

F .2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974) this Court stated:

Under Title VII and section 1981 the injured

workers must be restored to the economic position in which they would have been but for

the discrimination — their "rightful place."

Because of the compensatory nature of a back

pay award and because of the "rightful place"

theory, adopted by the courts, and of the

strong congressional policy, embodied in

Title VII, for remedying employment-dis

crimination, the scope of a court's discre

tion to deny back pay is narrow........

Once a court has determined that a plaintiff

class has sustained economic loss from a dis

criminatory employment practice, back pay

should normally be awarded unless special

circumstances are present . . . (emphasis

in the original and added).

The district court should have in addition to

-26-

ordering plaintiff's reappointment to a principalship

awarded him back pay for income lost and compensation

for the additional expenses incurred as a result of

his wrongful demotion. In not doing so, the court

erred.

-27-

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons,

Plaintiff-Appellee Cross Appellant respectfully

prays that the Order of the district court be

affirmed with modification granting bach pay and

other lost allowances to which he is entitled.

Plaintiff-Appellee Cross Appellant

further respectfully prays that this Court grant

him reasonable attorneys' fees in connection with

this appeal as well as his costs.

Respectfully submitted,

SPRIGGSColle'geyKENT

{ / 324 WTallahassee

Avenue

Fla. 32301

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES C. GRAY, JR.10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellee

Cross Appellant

-28-

C E R T I F I C A T E OF S E R V I C E

I hereby certify that on this 14th day of

August, 1975, I served two copies of the foregoing

Brief for Plaintiff-Appellee Cross Appellant upon

counsel for the Defendants-Appellants Cross Appellees

by depositing same in the United States mail, first

class postage prepaid, addressed to -

Brian T. HayesPost Office Box 1385

Tallahassee, Florida 32302