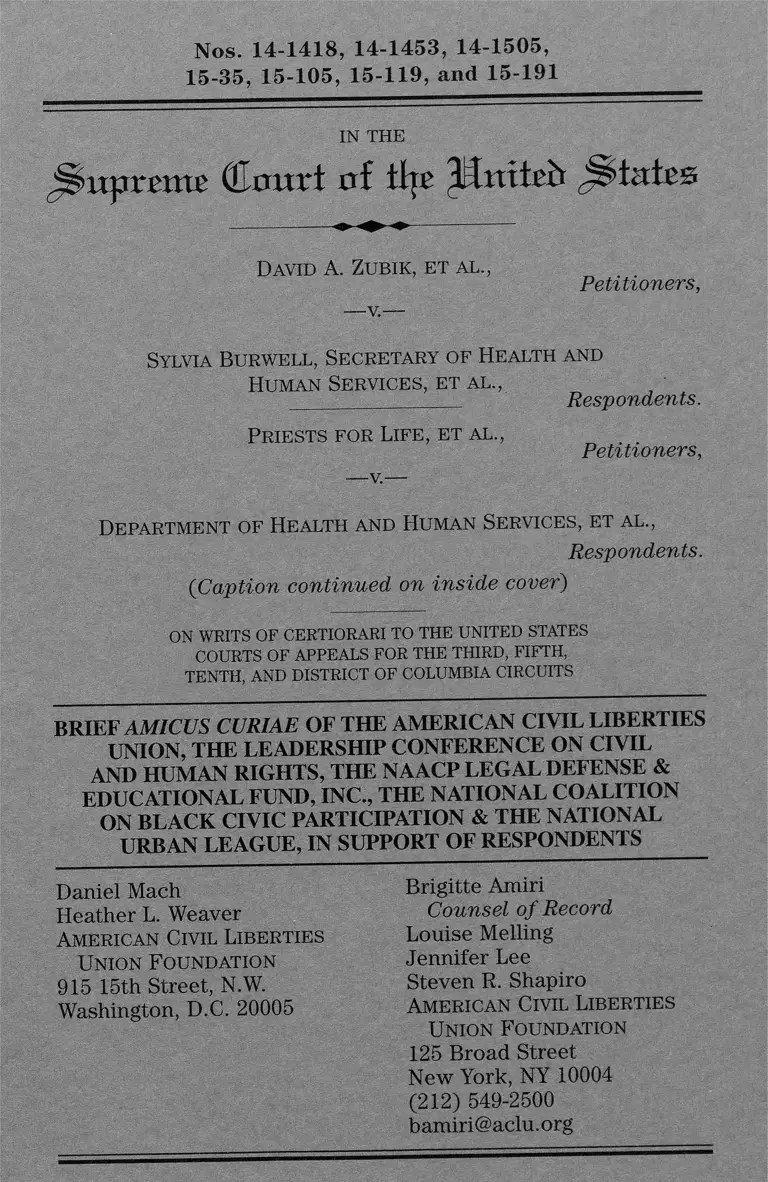

Zubik v. Burwell Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 16, 2016

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Zubik v. Burwell Brief Amicus Curiae, 2016. d50a19ce-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8c8af91d-bf32-4435-b34a-7176a44300da/zubik-v-burwell-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 14-1418, 14-1453, 14-1505,

15-35, 15-105, 15-119, and 15-191

IN THE

u p r tx x x t (JJtfurt #f t \ \ t p la te s

D a v id A. Zu b i k , e t a l .,

Petitioners,

Sy l v ia B u r w e l l , Se c r e t a r y o f H e a l t h a n d

H u m a n S e r v ic e s , e t a l .,________________ Respondents.

Pr ie s t s f o r L i f e , e t a l .,

Petitioners,

D e p a r t m e n t o f H e a l t h a n d H u m a n Se r v ic e s , e t a l .,

Respondents.

(Caption continued on inside cover)

o n w r it s o f c e r t io r a r i t o t h e u n it e d s t a t e s

COURTS OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD, FIFTH,

TENTH, AND DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUITS

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION, THE LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE ON CIVIL

AND HUMAN RIGHTS, THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., THE NATIONAL COALITION

ON BLACK CIVIC PARTICIPATION & THE NATIONAL

URBAN LEAGUE, IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Daniel Mach Brigitte Amiri

Heather L. Weaver Counsel o f Record

A m e r ic a n C iv il Lib e r t ie s Louise Melling

U n io n F o u n d a t io n Jennifer Lee

915 15th Street, N.W. Steven R. Shapiro

Washington, D.C. 20005 A m e r i c a n C iv il L ib e r t ie s

U n io n F o u n d a t io n

125 Broad Street

New York, NY 10004

(212) 549-2500

bamiri@aclu.org

mailto:bamiri@aclu.org

R o m a n Ca t h o l ic A r c h b is h o p o f W a s h i n g t o n , e t a l .,

Petitioners,-v.-

Sy l v ia B u r w e l l , Se c r e t a r y o f H e a l t h a n d

H u m a n Se r v ic e s , e t a l .,

Respondents.

E a s t T e x a s B a p t is t U n iv e r s it y , e t a l .,

-V .- Petitioners,

Sy l v ia B u r w e l l , Se c r e t a r y o f H e a l t h a n d

H u m a n Se r v ic e s , e t a l .,

Respondents.

Lit t l e S is t e r s o f t h e P o o r H o m e f o r t h e A g e d ,

D e n v e r , C o l o r a d o , e t a l .,

Petitioners,

—v.—

Sy l v ia B u r w e l l , Se c r e t a r y o f H e a l t h a n d

H u m a n Se r v ic e s , e t a l .,

Respondents.

So u t h e r n N a z a r e n e U n iv e r s it y , e t a l .

- v .-

Petitioners,

Sy l v ia B u r w e l l , Se c r e t a r y o f H e a l t h a n d

H u m a n Se r v ic e s , e t a l .,

Respondents.

G e n e v a C o l l e g e ,

Petitioner,

Sy l v ia B u r w e l l , Se c r e t a r y o f H e a l t h a n d

H u m a n Se r v ic e s , e t a l .,

Respondents.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.......................................... ii

STATEMENT OF INTEREST.......................................1

FACTUAL BACKGROUND...........................................4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT....................................... 9

ARGUMENT............................................ 13

I. THE HISTORICAL MOVEMENT

TOWARD GREATER EQUALITY FOR

WOMEN AND RACIAL MINORITIES

HAS BEEN ACCOMPANIED BY A

GROWING REJECTION OF RELIGIOUS

JUSTIFICATIONS FOR DISCRIMINATION

IN THE MARKETPLACE................................... 13

A. Racial Discrimination.................................. 13

B. Gender Discrimination................................21

II. THIS COURT SHOULD NOT ALLOW

THE EMPLOYERS HERE TO RESURRECT

THE DISCREDITED NOTION THAT

RELIGIOUS BELIEFS MAY TRUMP

A LAW DESIGNED TO ENSURE EQUAL

PARTICIPATION IN SOCIETY.......................28

CONCLUSION.............................................................. 34

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Berea College v. Commonwealth, 94 S.W. 623

(Ky. 1906), aff’d, 211 U.S. 45 (1908)................. . 15

Boh Jones University v. United States,

461 U.S. 574 (1983).................................................. 18

Bowie v. Birmingham Railway. & Electric Co.,

27 So. 1016 (Ala. 1900)............................................. 15

Bradwell v. State, 83 U.S. 130 (1872).......................22

Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954)............................................ 16, 17

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc.,

134 S. Ct. 2751 (2014)............................... 8, 9, 12, 33

Corporation of the Presiding Bishop of the Church

of Latter-Day Saints v. Amos, 483 U.S. 327

(1987)........................................................................... 19

Dole v. Shenandoah Baptist Church,

899 F.2d 1389 (4th Cir. 1990).................................27

EEOC v. Fremont Christian Schools,

781 F.2d 1362 (9th Cir. 1986).................................27

EEOC v. Pacific Press Publishing Ass 'n,

676 F.2d 1272 (9th Cir. 1982)................................. 19

EEOC v. Tree of Life Christian Schools,

751 F. Supp. 700 (S.D. Ohio 1990).......................... 27

Forziano v. Independant Group Home Living

Program, No. 13-cv-0370, 2014 WL 1277912

(E.D.N.Y. Mar. 26, 2014)...........................................28

Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677 (1973).... 21, 23

ii

Ganzy v. Allen Christian School,

995 F. Supp. 340 (E.D.N.Y. 1998)..........................27

Green u. State, 58 Ala. 190 (Ala. 1877)..................... 15

Hamilton v. Southland Christian School, Inc.,

680 F.3d 1316 (11th Cir. 2012).............................. 27

Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church &

School v. EEOC, 132 S. Ct. 694 (2012)................. 19

Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57 (1961).....................24, 30

International Union v. Johnson Controls, Inc.,

499 U.S. 187 (1991).................................................. 26

Kinney v. Commonwealth, 71 Va. 858 (Va. 1878).... 15

Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003).................... 31

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)...................18-19

Matthews v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc.,

417 F. App’x 552 (7th Cir. 2011)............................ 28

Muller v. Oregon, 208 U.S. 412 (1908)......................24

Nevada Department of Human Resources v. Hibbs,

538 U.S. 721 (2003)..................................... 23, 26, 30

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises., Inc., 256 F.

Supp. 941 (D.S.C. 1966), aff’d in relevant part and

rev’d in part on other grounds, 377 F.2d 433 (4th

Cir. 1967), aff’d and modified on other grounds,

390 U.S. 400 (1968).................................................. 20

Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2594 (2016)........... 10

Orr v. Orr, 440 U.S. 268 (1979).................................. 25

Peterson v. Hewlett-Packard Co.,

358 F.3d 599 (9th Cir. 2004) ...

iii

28

Planned Parenthood o f Southeastern Pennsylvania

v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992)................................ 30

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896).................... 16

Scott v. Emerson, 15 Mo. 576 (Mo. 1852)............... 14

Scott v. State, 39 Ga. 321 (Ga. 1869)......................... 14

Stanton v. Stanton, 421 U.S. 7 (1975)..................... . 25

State ex rel. Hawkins v. Bd. of Control,

83 So. 2d 20 (Fla. 1955)............................................ 16

State v. Gibson, 36 Ind. 389 (Ind. 1871)....................15

Swanner v. Anchorage Equal Rights Commission,

874 P.2d 274 (Alaska 1994)..................................... 28

The West Chester & Philadelphia Railroad v. Miles,

55 Pa. 209 (Pa. 1867)............................................. . 15

United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515 (1996)........26

Vigars v. Valley Christian Center,

805 F. Supp. 802 (N.D. Cal. 1992)....................... . 27

STATUTES

Title IX, Education Amendments of 1972,

20U.S.C. § 1681(a)(3)............................................... 24

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,

Pub. L. No. 111-148, sec. 1001, § 2713(a),

124 Stat. 119 (2010), 42 U.S.C.A. § 300gg-13.........4

Women’s Health Amendment,

§ 2713(a)(4), 124 Stat. 119 .......................................4

ADMINISTRATIVE & LEGISLATIVE

MATERIALS

155 Cong. Rec. S ll,979 (daily ed. Nov. 30, 2009)..... 4

IV

5155 Cong. Rec. S 12,019 (daily ed. Dec. 1, 2009).....

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Form

No. CMS-10459: Coverage of Certain Preventive

Services under the Affordable Care Act (2015)..... 7

Health Resources & Services Administration., U.S.

Departmentof Health & Human Services., Women’s

Preventive Services: Required Health Plan

Coverage Guidelines, http://www.hrsa.gov/

womensguidelines.........................................................6

Tax-Exempt Status of Private Schs.: Hearing Before

the Subcommittee on Taxation & Debt Management

Generally of the Committee on Finance, 96th Cong.

18 (1979) (statement by Sen. Laxalt)...................... 17

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Discriminatory

Religious Schools and Tax Exempt Status

(1982).......................................................................... 17

REGULATIONS

26 C.F.R. § 54.9815-2713A............................................ 8

26 C.F.R. § 54.9815-2713A(a)........................................ 7

26 C.F.R. § 54.9815-2713A(a)(3)...................................7

26 C.F.R. § 54.9815-2713A(b)........................................7

26 C.F.R. § 54.9815-2713A(c)........................................ 7

26 C.F.R. § 54.9815-2713A(d)........................................ 7

45 C.F.R. § 147.130(b)(1)................................................6

45 C.F.R. § 147.131(a)..................................................... 7

77 Fed. Reg. 8725 (Feb. 15, 2012)................................. 7

v

http://www.hrsa.gov/

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Armantine M. Smith, The History of the Woman’s

Suffrage Movement in Louisiana,

62 La. L. Rev. 509 (2002)...................................... 22

Claudia Goldin & Lawrence F. Katz, The Power of

the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women’s Career

and Marriage Decisions,

110 J. Pol. Econ. 730 (2002).................................... 30

Colleen McNicholas et al., The Contraceptive

CHOICE Project Round Up, 57 Clinical Obstetrics

& Gynecology 635 (Dec. 2014).................................32

Convention of Ministers, An Address to Christians

Throughout the World (1863).................................. 14

Guttmacher Institute, A Real-Time Look at the

Impact of the Recession on Women’s Family

Planning and Pregnancy Decisions (Sept. 2009).. 31

Guttmacher Institute, Fact Sheet: Contraceptive Use

in the United States (Aug. 2013)............................ 32

Guttmacher Institute, Unintended Pregnancy in the

United States (July 2015)........................................ 31

H.S. Pomeroy, The Ethics o f Marriage (1888).........23

Institute of Medicine, Clinical Preventive Services for

Women: Closing the Gaps (July 2011).... ................5

Jeffrey Peipert et al., Continuation and Satisfaction

of Reversible Contraception, 117 Obstetrics &

Gynecology 1105 (2011).......................... ................. 32

Jeffrey Peipert et al., Preventing Unintended

Pregnancies by Providing No-Cost Contraception,

120 Obstetrics & Gynecology 1291 (2012).......31-32

vi

John C. Jeffries, Jr. & James E. Ryan, A Political

History o f the Establishment Clause,

100 Mich. L. Rev. 279 (2001)................................... 17

Kevin Outterson, Tragedy and Remedy: Reparations

for Disparities in Black Health,

9 DePaul J. Health Care L. 735 (2005).................. 16

Martha J. Bailey et al., The Opt-in Revolution?

Contraception and the Gender Gap in Wages,

(Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Research Working

Paper No. 17922, 2012)......................................29-30

Note, Segregation Academies and State Action,

82 Yale L.J. 1436 (1973)........................................... 17

R. Randall Kelso, Modern Moral Reasoning and

Emerging Trends in Constitutional and Other

Rights Decision-Making Around the World,

29 Quinnipiac L. Rev. 433 (2011)..................... 14, 20

Rev. Justin D. Fulton, Women vs. Ballot, in The True

Woman: A Series of Discourses: To Which Is

Added Woman vs. Ballot (1869)........................22-23

Reva B. Siegel, Reasoning from the Body: A

Historical Perspective on Abortion Regulation and

Questions of Equal Protection,

44 Stan. L. Rev. 261 (1991)..................................... 23

Reva B. Siegel, She the People: The Nineteenth

Amendment, Sex Equality, Federalism, and the

Family, 115 Harv. L. Rev. 947 (2002).................... 22

Sidney D. Watson, Race, Ethnicity and Quality of

Care: Inequalities and Incentives,

27 Am. J.L. & Med. 203 (2001).............................. 16

Statement about Race at BJU, Bob Jones Univ.

(2016)..........................................................................21

vii

Susan A. Cohen, The Broad Benefits o f Investing in

Sexual and Reproductive Health, 7 The

Guttmacher Report on Pub. Poly 5 (2004)...........29

Su-Ying Liang et al., Women’s Out-of-Pocket

Expenditures and Dispensing Patterns for Oral

Contraceptive Pills Between 1996 and 2006,

83 Contraception 528 (2010)................ 31

The Leadership Conference Education Fund,

Striking a Balance: Advancing Civil and Human

Rights While Preserving Religious Liberty (Jan.

2016)............................................................. ...............28

Tom Howell, Jr., Catholic Hospitals are OK with

Obama Contraception Mandate, Protections,

Wash. Times, July 9, 2013........................................28

viii

STATEMENT OF INTEREST1

The American Civil Liberties Union (“ACLU”)

is a nationwide, nonprofit, nonpartisan organization

with nearly 500,000 members dedicated to defending

the principles of liberty and equality embodied in the

Constitution and the nation’s civil rights laws.

The ACLU has a long history of furthering racial

justice and women’s rights, and an equally long

history of defending religious liberty. The ACLU also

vigorously protects reproductive freedom, and has

participated in almost every critical case concerning

reproductive rights to reach the Supreme Court.

The Leadership Conference on Civil and

Human Rights (“The Leadership Conference”) is a

coalition of more than 200 national organizations

committed to the protection of civil and human rights

in the United States. It is the nation’s oldest, largest,

and most diverse civil and human rights coalition.

The Leadership Conference was founded in 1950 by

three legendary leaders of the civil rights

movements—A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood

of Sleeping Car Porters; Roy Wilkins of the

NAACP; and Arnold Aronson of the National

Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council.

Its member organizations represent people of all

races, ethnicities, religious ideologies and sexual

orientations. The Leadership Conference works to

build an America that is inclusive and as good as

its ideals, and to that end believes that the

1 The parties have filed blanket letters of consent to amicus

briefs in support of either party or neither party. No counsel for

a party authored this brief in whole or in part, and no person

other than amici or their counsel made a monetary contribution

to the preparation or submission of this brief.

1

core values of religious freedom and legal

and social equality are not incompatible; rather,

this nation must stand united in ensuring religious

liberty while continuing to work together

to dismantle institutionalized discrimination.

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc. (“LDF”) is a nonprofit legal organization

that, for more than seven decades, has helped

African Americans secure their civil and

constitutional rights. Throughout its history, LDF

has worked to support and provide equal treatment

and high-quality medical services, care, and

opportunities to African Americans. E.g., Linton v.

Comm’r of Health & Env’t, 65 F.3d 508 (6th Cir.

1995) (preservation of Medicaid-certified hospital

and nursing home beds to prevent eviction of

patients in favor of admitting more remunerative

private-pay individuals); Bryan v. Koch, 627 F.2d 612

(2d Cir. 1980) (challenge to closure of municipal

hospital serving inner-city residents); Simkins v.

Moses H. Cone Mem’l Hosp., 323 F.2d 959 (4th Cir.

1963) (admission of African-American physician to

hospital staff); Mussington v. St. Luke’s-Roosevelt

Hosp. Ctr., 824 F. Supp. 427 (S.D.N.Y. 1993)

(relocation of services from inner-city branch of

merged hospital entity); Rackley v. Bd. of Trs. of

Orangeburg Reg’l Hosp., 238 F. Supp. 512 (E.D.S.C.

1965) (desegregation of hospital wards); Consent

Decree, Terry v. Methodist Hosp. o f Gary, Nos. H-76-

373, H-77-154 (N.D. Ind. June 8, 1979) (planned

relocation of urban hospital services from inner-city

community). LDF has also worked on a variety of

cases challenging religious justifications for

discrimination in public accommodations or services.

See, e.g., Gifford v. McCarthy, 23 N.Y.S.3d 422

2

(N.Y. App. Div. 2016). LDF has a substantial interest

in this case because of its continuing commitment to

promoting equal opportunity for African Americans,

including access to affordable health insurance and

health care.

The National Coalition on Black Civic

Participation has been actively engaged in social

justice movements on the national, state, and local

level through our coalition-based campaigns and

organizing networks for nearly four decades.

The National Coalition is dedicated to the

empowerment of women and girls and black youth,

particularly Black males through its Black Women’s

Roundtable and Black Youth Vote! networks,

leadership development, and civic engagement

programs. The National Coalition believes that

protecting individuals’ right to worship, and to

express their religious beliefs, and protecting

reproductive freedoms, are key to the organization’s

empowerment goals.

The National Urban League is a historic

civil rights organization dedicated to economic

empowerment in historically underserved urban

communities. Founded in 1910 and headquartered in

New York City, the National Urban League improves

the lives of more than two million people annually

through direct service programs, including education,

employment training and placement, housing, and

health, which are implemented locally by more than

90 National Urban League affiliates in 300

communities across 36 states and the District of

Columbia. The National Urban League works

to provide the guarantee of civil rights for the

underserved in America. Recognizing that economic

3

empowerment in underserved communities is

inextricably linked to the reduction of racial health

disparities in America, the organization has

established the goal that by 2025 every American has

access to quality and affordable health care solutions.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

The Affordable Care Act requires health

insurance plans to cover certain preventive services

without cost-sharing. Patient Protection and

Affordable Care Act (“ACA”), Pub. L. No. 111-148,

sec. 1001, § 2713(a), 124 Stat. 119, 131-32 (2010)

(codified at 42 U.S.C.A. § 300gg-13). The Women’s

Health Amendment (“WHA”) was adopted during

debate over the ACA to ensure that the list of covered

services would include preventive services unique to

women. Id. § 2713(a)(4), 124 Stat. at 131. In passing

the WHA, Senator Mikulski noted, “ [o]ften those

things unique to women have not been included in

health care reform. Today we guarantee it and we

assure it and we make it affordable by dealing with

copayments and deductibles . . . .” 155 Cong. Rec.

S i 1,979, SI 1,988 (daily ed. Nov. 30, 2009); see also

id. at S i 1,987 (noting that the ACA as initially

drafted did not cover key preventive services for

women). In particular, the WHA was intended to

address gender disparities in out-of-pocket health

care costs, which stem in large part from

reproductive health care. As Senator Gillibrand

explained:

Not only do we [women] pay more for

the coverage we seek for the same age

and the same coverage as men do, but in

general women of childbearing age

4

spend 68 percent more in out-of-pocket

health care costs than men. . . . This

fundamental inequity in the current

system is dangerous and discriminatory

and we must act. The prevention section

of the bill before us must be amended so

coverage of preventive services takes

into account the unique health care

needs of women throughout their

lifespan.

155 Cong. Rec. S12,019, S12,027 (daily ed. Dec. 1,

2009).

Recognizing the importance of preventive

services for both men and women, Congress then

delegated the responsibility for developing a list of

preventive services covered by the ACA to the

Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”).

HHS, in turn, asked the Institute of Medicine

(“IOM”), an independent, nonprofit organization, to

recommend services that should be covered. IOM

recommended that the covered preventive services

include, among other things, the full range of

contraceptives approved by the Food and Drug

Administration (“FDA”). Inst, of Med., Clinical

Preventive Services for Women: Closing the Gaps 109-

10 (July 2011). In making this recommendation, IOM

noted that “ [djespite increases in private health

insurance coverage of contraception since the 1990s,

many women do not have insurance coverage or are

in health plans in which copayments for visits and

for prescriptions have increased in recent years.”

Id. at 109. It further noted that these cost barriers

are aggravated by the fact that women “typically

5

earn less than men and . , . disproportionately have

low incomes.” Id. at 19.

Adopting IOM’s recommendations, HHS

promulgated regulations that require non-

grandfathered plans covered by the ACA to provide

health care coverage without cost-sharing for

“ [a]ll Food and Drug Administration approved

contraceptive methods, sterilization procedures, and

patient education and counseling for all women with

reproductive capacity,” commonly referred to as the

“contraceptive requirement.” See 45 C.F.R.

§ 147.130(b)(1); Health Res. & Servs. Admin., U.S.

Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Women’s Preventive

Services: Required Health Plan Coverage Guidelines,

http://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines (last visited

Feb. 9, 2016).

In announcing the regulations, HHS

emphasized the importance of including

contraception in the designated list of preventive

services, not only to equalize women’s health care

costs but also to help women become equal

participants in society. The inability of women to

access contraception, HHS noted,

places women in the workforce at a

disadvantage compared to their male co

workers. Researchers have shown that

access to contraception improves the

social and economic status of women.

Contraceptive coverage, by reducing the

number of unintended and potentially

unhealthy pregnancies, furthers the

goal of eliminating this disparity by

allowing women to achieve equal status

as healthy and productive members of

6

http://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines

the job force . . . . The [federal

government] aim[s] to reduce these

disparities by providing women broad

access to preventive services, including

contraceptive services.

77 Fed. Reg. 8725, 8728 (Feb. 15, 2012) (footnote

omitted).

The federal government also developed an

“accommodation” for religiously affiliated nonprofit

organizations that have religious objections to

covering contraception.2 Under this accommodation,

eligible employers who object on religious grounds

can fill out a one-page form to opt out of providing

coverage “for some or all of any contraceptive items

or services required to be covered.” 26 C.F.R.

§ 54.9815-2713A(a); Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid

Servs. Form No. CMS-10459: Coverage of Certain

Preventive Services under the Affordable Care Act

(2015). This form can be sent to either the insurance

company or the federal government. 26 C.F.R.

§ 54.9815-2713A(a)(3). The insurance company then

administers and pays for those contraceptive

services, including by communicating with the

employees about the coverage.3 Id. § 54.9815-

2713A(c)-(d).

2 In addition, the regulations authorize an exemption for the

group health plan of a “religious employer,” 45 C.F.R.

§ 147.131(a), which is not challenged in this case.

3 Employers that self-insure must provide their third party

administrators with a copy of the self-certification form. 26

C.F.R. § 54.9815-2713A(b). The third party administrator will

similarly notify the organization’s employees that it will be

providing payments for contraceptive services. Id. § 54.9815-

2713A(d). The rule explicitly prohibits the third party

7

In response to this Court’s decision in Burwell

v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2751 (2014),

the accommodation for religiously affiliated nonprofit

organizations was recently extended to “closely held”

for-profit companies. Indeed, the majority in Hobby

Lobby relied on this accommodation in finding that

the original contraception rule violated the Religious

Freedom Restoration Act (“RFRA”) as applied to

closely held for-profit companies:

HHS has already devised and implemented

a system that seeks to respect the religious

liberty of religious nonprofit corporations

while ensuring that the employees of these

entities have precisely the same access to

all FDA-approved contraceptives as

employees of companies whose owners have

no religious objections to providing such

coverage. . . . We therefore conclude that

this system constitutes an alternative that

achieves all of the Government’s aims

while providing greater respect for

religious liberty. . . . The effect of the HHS-

created accommodation on the women

employed by Hobby Lobby and the other

companies involved in these cases would be

precisely zero. Under that accommodation,

these women would still be entitled to all

FDA-approved contraceptives without cost

sharing.

administrator from “imposing a premium, fee, or other charge,

or any portion thereof, directly or indirectly on” the

organizations or their employees for the separate contraception

payments. Id. § 54.9815-2713A.

8

134 S. Ct. at 2759-60; see also id. at 2786 (the

“accommodation equally furthers the Government’s

interest but does not impinge on the plaintiffs’

religious beliefs”) (Kennedy, J., concurring). The

employers in the instant cases challenge the very

accommodation that this Court relied on in Hobby

Lobby.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The government argues that the Religious

Freedom Restoration Act does not require any

further accommodation of Petitioners’ religious

beliefs and does not mandate any further dilution of

the rights of employees who seek access to the

contraceptive coverage benefit guaranteed by law.

Amici agree, and we do not repeat those arguments

here. Instead, we submit this brief to highlight an

important lesson of history: As our society has moved

toward greater equality for racial minorities and

women, it has increasingly and properly rejected the

idea that religion can be used as a justification

for discrimination in the marketplace. Petitioners’

challenge to the accommodation should likewise be

rejected.

Religion is a powerful force that shapes

individual lives and influences community values.

Like other belief systems, it has been used at

different times and places to support change and to

oppose it, to promote equality and to justify

inequality. Our constitutional structure recognizes

the importance of religion by protecting its free

exercise, and a full range of statutes and regulations

reinforce our collective commitment to religious

tolerance and pluralism. This Court in Hobby Lobby

understood the accommodation that is being

9

challenged in this case as a reflection of that

commitment. Critically, however, the accommodation

also recognizes that access to contraceptive care is an

important means of ending discrimination against

women in the workplace, and that the elimination of

such discrimination in the marketplace is a

compelling state interest.

The struggle to overcome discrimination while

respecting religious liberty is a recurring challenge in

our nation’s history. By recounting that history in

this brief, we do not question Petitioners’ religious

faith or suggest that the historical invocation of

religion to justify the most odious forms of racial

discrimination is equivalent to the religious claims

that Petitioners have raised here. But that is not the

test and should not be the legal measuring rod.

As this Court recently observed in Obergefell v.

Hodges, religious objections to anti-discrimination

laws are often “based on decent and honorable

religious or philosophical premises, and neither they

nor their beliefs are disparaged here. But when that

sincere, personal opposition becomes enacted law and

public policy, the necessary consequence is to put the

imprimatur of the State itself on an exclusion that

soon demeans or stigmatizes those whose own liberty

is then denied.” 135 S. Ct. 2594, 2602 (2016).

Religious leaders - like Dr. Martin Luther

King, Jr. — have often led the movement against

discrimination. Throughout our history, however,

religion has also been used to defend discriminatory

practices, to oppose evolving notions of equality, and

10

to seek broad exemptions to new legal norms. We

can and should learn from that experience.4

From the early years of the Republic, religious

beliefs were used to justify racial subordination,

including the forced enslavement of Africans.

Far too often, moreover, those views found support

in judicial decisions upholding racial segregation

and anti-miscegenation laws. Even as the nation’s

standards evolved to prohibit racial discrimination

in employment, education, marriage, and public

accommodations, religious arguments continued

to be used to fuel resistance to progress.

In particular, Congress and the courts faced repeated

calls for religious exemptions to non-discrimination

standards. But, by the middle of the twentieth

century, those calls were rejected by both the Courts

and Congress. Instead, the country came to recognize

the vital state interest in ending racial

discrimination in public arenas and in embracing a

vision of equality that does not sanction piecemeal

application of the law.

The story of women’s emerging equality

follows a similar pattern. Religious beliefs were

invoked to justify restrictions on women’s roles,

including in suffrage, employment, and access to

birth control. Later, religion inspired legislation

purportedly designed to “protect” women, including

their reproductive capacities. As attitudes changed,

laws were enacted prohibiting discrimination and

protecting women’s ability to control their

4 This brief focuses on efforts to justify discrimination against

racial minorities and women on religious grounds, but other

disadvantaged and marginalized groups have shared similar

experiences. See 27 n .l l , infra.

11

reproductive capacity. These measures, like those

designed to promote racial equality, were met with

resistance, including religiously motivated requests

to avoid compliance with evolving legal standards.

And, as with race, Congress and the courts have held

firm to the vision embodied in newly passed anti-

discrimination measures.

The contraception rule addresses a remaining

vestige of sex discrimination. As this Court has

recognized, women’s ability to control their

reproductive capacities is essential to their

participation in society. Contraception is not simply

a pill or a device; it is a tool, like education, essential

to women’s equality. Without access to contraception,

women’s ability to complete an education, to hold a

job, to advance in a career, to care for children, or to

aspire to a higher place, whatever that may be, may

be significantly compromised. By making access to

contraception meaningful for many women, the

contraception rule takes a giant and long overdue

step to level the playing field.

Petitioners ask to be wholly exempt from the

contraception rule, arguing that their faith prohibits

them from asking for the accommodation, and that

the government should be prohibited from requiring

the insurance company to provide separate coverage

to their employees. Hobby Lobby does not support

this position, and Hobby Lobby’s reasoning is

irreconcilable with what Petitioners now seek.

Employers do not forfeit their individual right to

oppose contraceptives on religious grounds, but a

personal religious objection is not a license to

disregard the law.

12

ARGUMENT

I. THE HISTORICAL MOVEMENT

TOWARD GREATER EQUALITY FOR

WOMEN AND RACIAL MINORITIES HAS

BEEN ACCOMPANIED BY A GROWING

REJECTION OF RELIGIOUS JUSTI

FICATIONS FOR DISCRIMINATION IN

THE MARKETPLACE.

A. Racial Discrimination

There was a time in our nation’s history when

religion was used to justify slavery, Jim Crow laws,

and bans on interracial marriage. God and “Divine

Providence” were invoked to validate segregation,

and, for decades, these arguments trumped secular

and religious calls for equality and humanity.

Eventually, due to evolving societal attitudes and the

steadfast efforts of civil rights advocates, systems of

enslavement and segregation were dismantled, and

those who clung to religious justifications for racial

discrimination were nonetheless required to obey the

nation’s anti-discrimination laws. Although the

history of religious justification for slavery, racial

discrimination, and racial segregation are different

in many ways from the instant request for a religious

exemption, the lessons derived from that experience

are instructive.

Early in our country’s history, religious beliefs

were invoked to justify the most fundamental of

inequalities. Indeed, slavery itself was often

defended in the name of faith. The Missouri Supreme

Court, in rejecting Dred Scott’s claim for freedom,

suggested that slavery was “the providence of God” to

rescue an “unhappy race” from Africa and place them

13

in “civilized nations.” Scott u. Emerson, 15 Mo. 576,

587 (Mo. 1852). Jefferson Davis, President of the

Confederate States of America, proclaimed that

slavery was sanctioned by “the Bible, in both

Testaments, from Genesis to Revelation.” R. Randall

Kelso, Modern Moral Reasoning and Emerging

Trends in Constitutional and Other Rights Decision-

Making Around the World, 29 Quinnipiac L. Rev.

433, 437 (2011) (citation and quotations omitted).

Christian pastors and leaders declared: “We regard

abolitionism as an interference with the plans of

Divine Providence.” Convention of Ministers, An

Address to Christians Throughout the World 8 (1863),

https://archive.org/details/addresstochristiOOphil

(last visited Feb. 9, 2016).

Religion was also invoked, including by the

courts, to justify anti-miscegenation laws. For

example, in upholding the criminal conviction of an

African-American woman for cohabitating with a

white man, the Georgia Supreme Court held that no

law of the State could

attempt to enforce [ ] moral or social

equality between the different races or

citizens of the State. Such equality does

not in fact exist, and never can. The

God of nature made it otherwise, and no

human law can produce it, and no

human tribunal can enforce it.

Scott u. State, 39 Ga. 321, 326 (Ga. 1869). In

upholding the criminal conviction of an interracial

couple for violation of Virginia’s anti-miscegenation

law, the Virginia Supreme Court reasoned that,

based on “the Almighty,” the two races should be

kept “distinct and separate, and that connections and

14

https://archive.org/details/addresstochristiOOphil

alliances so unnatural that God and nature seem to

forbid them, should be prohibited by positive law and

be subject to no evasion.” Kinney v. Commonwealth,

71 Va. 858, 869 (Va. 1878); see also Green v. State, 58

Ala. 190, 195 (Ala. 1877) (upholding conviction for

interracial marriage, reasoning God “has made the

two races distinct”); State v. Gibson, 36 Ind. 389, 405

(Ind. 1871) (declaring right “to follow the law of races

established by the Creator himself’ to uphold

constitutionality of conviction of a black man who

married a white woman).

Similar justifications were accepted by courts

to sustain segregation. In 1867, Mary E. Miles defied

railroad rules by refusing to take a seat in the

“colored” section of the train car. She brought suit

against the railroad for physically ejecting her from

the train. A jury awarded Ms. Miles five dollars.

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania reversed,

relying in part on “the order of Divine Providence”

that dictates that the races should not mix. The West

Chester & Phila. R.R. u. Miles, 55 Pa. 209, 213 (Pa.

1867); see also Bowie v. Birmingham Ry. & Elec. Co.,

27 So. 1016, 1018-19 (Ala. 1900) (looking to

reasoning from Miles to affirm judgment for railroad

that forcibly ejected African-American woman from

the “whites only” section of rail car). In 1906, the

Kentucky Supreme Court affirmed the enforcement

of a law prohibiting whites and blacks from

attending the same school, noting that the separation

of the races was “divinely ordered.” Berea College u.

Commonwealth, 94 S.W. 623, 626 (Ky. 1906), aff’d,

211 U.S. 45 (1908).5

5 Religious justifications for segregation also had a direct impact

on the availability and quality of health care for African

15

These religious arguments in favor of racial

segregation slowly lost currency, but not without

resistance. The turning point in our country’s history

was marked by two events. The first was this Court’s

decision in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483 (1954), which repudiated the “separate but

equal” doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163

U.S. 537 (1896), and declared racial segregation in

public schools to be unconstitutional. The second was

Congress’s passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

which prohibited discrimination in public schools,

employment, and public accommodations.

The resistance to the movement for racial

equality, both religiously based and other, was

particularly intense in the context of education.

Members of the Florida Supreme Court invoked

religion to justify resistance to integration in the

schools, noting that “when God created man, he

allotted each race to his own continent according to

color, Europe to the white man, Asia to the yellow

man, Africa to the black man, and America to the red

man.” State ex rel. Hawkins u. Bd. o f Control, 83 So.

2d 20, 28 (Fla. 1955) (concurring opinion). Indeed,

they went so far as to characterize Brown as advising

Americans. See, e.g., Sidney D. Watson, Race, Ethnicity and

Quality of Care: Inequalities and Incentives, 27 Am. J.L. & Med.

203, 211 (2001) (“Historically, most hospitals were ‘white only.’

The few hospitals that admitted Blacks strictly limited their

numbers [and] segregated [the facilities and equipment]”);

Kevin Outterson, Tragedy and Remedy: Reparations for

Disparities in Black Health, 9 DePaul J. Health Care L. 735,

757 (2005) (“Many hospitals were not available to Blacks in the

first half of the twentieth century.”).

16

“that God’s plan was in error and must be reversed.”

Id.

In the years following this Court’s enforcement

of Brown, the number of private, often Christian,

segregated schools expanded exponentially and white

students left the public schools in droves. See Note,

Segregation Academies and State Action, 82 Yale L.J.

1436, 1437-40 (1973). See also U.S. Comm’n on Civil

Rights, Discriminatory Religious Schs. and Tax

Exempt Status 1, 4-5 (1982) (recounting the massive

withdrawal of white students from public schools

after Brown, and a proliferation of private schools,

many associated with churches). The schools were

often open about their motives. For example, Brother

Floyd Simmons, who founded the Elliston Baptist

Academy in Memphis, said, “I would never have

dreamed of starting a school, hadn’t it been for

busing.” John C. Jeffries, Jr. & James E. Ryan, A

Political History of the Establishment Clause, 100

Mich. L. Rev. 279, 334 (2001).

In response, the Treasury Department issued

a ruling declaring that racially segregated schools

would not be eligible for tax-exempt status.6

Attempts by the IRS to enforce the Treasury

6 Subsequent efforts by the IRS to adopt guidelines for

assessing whether private schools were not discriminatory, and

thus eligible for tax exempt status, met with resistance. At a

hearing, for example, Senators expressed concern about the

impact on religious schools, emphasizing that the issue

“involve [d] the rights of two groups of minorities.” See Tax-

Exempt Status of Private Schs.: Hearing Before the Subcomm.

on Taxation & Debt Mgmt. Generally of the Comm, on Fin., 96th

Cong. 18, 21 (1979) (statement by Sen. Laxalt).

17

Department’s rule met resistance in the courts. Most

notably, Bob Jones University brought suit after the

IRS revoked the University’s tax exempt status

based first on its policy of refusing to admit African-

American students, and subsequently on its policy of

refusing to admit students engaged in or advocating

interracial relationships. Bob Jones Univ. v. United-

States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983). The sponsors of

Bob Jones University “genuinely believe[d] that

the Bible forbids interracial dating and marriage.”

Id. at 580. Bob Jones’s lesser-known co-plaintiff,

Goldsboro Christian Schools, operated a school from

kindergarten through high school and refused to

admit African-American students. According to its

interpretation of the Bible, “ [cjultural or biological

mixing of the races [was] regarded as a violation of

God’s command.” Id. at 583 n.6. Both schools sued

under the Free Exercise Clause, arguing that the

rule could not constitutionally apply to schools

engaged in racial discrimination based on sincerely

held religious beliefs. This Court rejected the schools’

claims, holding that the government’s interest in

eradicating racial discrimination in education

outweighed any burdens on religious beliefs. Id. at

602-04.

Progress toward racial equality was not

limited to schools. Although the anti-miscegenation

laws eventually fell, the path to that rightful

conclusion was not a smooth one. The trial court in

Loving v. Virginia adhered to the reasoning of earlier

decades: ‘“Almighty God created the races white,

black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on

separate continents. And but for the interference

with his arrangement there would be no cause for

such marriages. The fact that he separated the races

18

shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.’”

388 U.S. 1, 3 (1967) (quoting trial court). But this

Court expressly rejected the trial court’s reasoning

and declared Virginia’s anti-miscegenation law

unconstitutional. Id. at 2.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 also faced

objections based on religion, all of which were

ultimately rejected. Most notably, the House

exempted religiously affiliated employers entirely

from the proscriptions of the Act. See EEOC v. Pac.

Press Pub. Assn, 676 F.2d 1272, 1276 (9th Cir. 1982)

(recounting legislative history of Civil Rights Act

of 1964). However, the law, as enacted, permitted

no employment discrimination based on race; it

only authorized religiously affiliated employers to

discriminate on the basis of religion. Id. Later efforts

to pass a blanket exemption for religiously affiliated

employers again failed. Id. at 1277.7

Religious resistance to the 1964 Civil Rights

Act did not stop with its passage. The owner of a

barbeque chain who was sued in 1964 for refusing to

serve blacks responded by claiming that serving

black people violated his religious beliefs. The court

rejected the restaurant owner’s defense, holding that

the owner

7 The Act, while barring race discrimination by religiously

affiliated entities, respects the workings of houses of worship

and also permits discrimination in favor of co-religionists in

certain religiously affiliated institutions and positions. See

Corp. of the Presiding Bishop of the Church of Latter-Day Saints

v. Amos, 483 U.S. 327 (1987); cf. Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical

Lutheran Church & Sch. v. EEOC, 132 S. Ct. 694 (2012)

(recognizing ministerial exception).

19

has a constitutional right to espouse the

religious beliefs of his own choosing,

however, he does not have the absolute

right to exercise and practice such

beliefs in utter disregard of the clear

constitutional rights of other citizens.

Newman v. Piggie Park Enters., Inc., 256 F. Supp.

941, 945 (D.S.C. 1966), aff’d in relevant part and

rev’d in part on other grounds, 377 F.2d 433 (4th Cir.

1967), aff’d and modified on other grounds, 390 U.S.

400 (1968).

Since the middle of the twentieth century, the

argument that religious beliefs trump measures

designed to eradicate racial discrimination - whether

in toto or piecemeal — has slowly lost its force.

As courts shifted to a wholesale rejection of religious

justifications for racial discrimination and societal

attitudes evolved, religious arguments were no

longer offered in mainstream society to defend racial

segregation and subordination. In fact, “no major

religious or secular tradition today attempts

to defend the practices of the past supporting

slavery, segregation, [or] anti-miscegenation laws.”

R. Randall Kelso, Modern Moral Reasoning, supra, at

439. Reflecting this evolution, Bob Jones University

has apologized for its prior discriminatory policies,

stating that by previously subscribing to a

segregationist ethos . . . we failed to

accurately represent the Lord and to

fulfill the commandment to love others

as ourselves. For these failures we are

profoundly sorry. Though no known

antagonism toward minorities or

expressions of racism on a personal

20

level have ever been tolerated on our

campus, we allowed institutional

policies to remain in place that were

racially hurtful.

See Statement about Race at RJU, Bob Jones Univ.,

http ://www .bj u. edu / about/what-we-believe/r ace-

statement.php (last visited Feb. 9, 2016). Although

there are many differences in the discrimination

described above and the contraception rule, this

history highlights the hazards of recognizing a

religious exemption to a federal anti-discrimination

measure that promotes a compelling governmental

interest in equality and opportunity.

B. Gender Discrimination

The path to achieving women’s equality has

followed a course similar to the struggle for racial

equality. See Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677,

684-88 (1973) (chronicling the long history of sex

discrimination in the United States).8 Efforts to

advance women’s equality, like those furthering

other civil rights, were supported — and thwarted — in

the name of religion. Those who invoked God and

faith as justification for slavery and segregation also

invoked God and faith to limit women’s roles.

One champion of slavery in the antebellum South,

George Fitzhugh, plainly stated that God gave white

men dominion over “slaves, wives, and children.”

8 The Court in Frontiero noted that “throughout much of the

19th century the position of women in our society was, in many

respects, comparable to that of blacks under the pre-Civil War

slave codes,” emphasizing that women, like slaves, could not

“hold office, serve on juries, or bring suit in their own names,”

and that married women traditionally could not own property

or even be legal guardians of their children. 411 U.S. at 685.

21

Armantine M. Smith, The History of the Woman’s

Suffrage Movement in Louisiana, 62 La. L. Rev. 509,

511 (2002).

Religious arguments were invoked to limit

women’s roles in society. And in this context, as with

race, these arguments were initially embraced by

courts. For example, this Court held that the State of

Illinois could prohibit women from practicing law,

and in his famous concurrence, Justice Bradley

opined that:

The constitution of the family

organization, which is founded in the

divine ordinance, as well as in the

nature of things, indicates the domestic

sphere as that which properly belongs to

the domain and functions of

womanhood. . . . The paramount destiny

and mission of woman are to fulfill the

noble and benign offices of wife and

mother. This is the law of the Creator.

Bradwell v. State, 83 U.S. 130, 141 (1872) (Bradley,

J., concurring).

This vision of women — as divinely destined for

the role of wife and mother - was a prominent

argument against suffrage. A leading antisuffragist,

Reverend Justin D. Fulton, proclaimed: ‘“It is patent

to every one that this attempt to secure the ballot for

woman is a revolt against the position and sphere

assigned to woman by God himself.’” Reva B. Siegel,

She the People: The Nineteenth Amendment, Sex

Equality, Federalism, and the Family, 115 Harv. L.

Rev. 947, 981 n.96 (2002) (quoting Rev. Justin D.

Fulton, Women vs. Ballot, in The True Woman: A

22

Series of Discourses: To Which Is Added Woman vs.

Ballot 3, 5 (1869)); see also id. at 978 (quoting Rep.

Caples at the California Constitutional Convention

in 1878-79 as saying of women’s suffrage: “It attacks

the integrity of the family; it attacks the eternal

degrees [sic] of God Almighty; it denies and

repudiates the obligations of motherhood.”) (internal

citation and quotations omitted). It was in this same

time period that the first laws against contraception

were enacted to address what was characterized as

“physiological sin.” Reva B. Siegel, Reasoning from

the Body: A Historical Perspective on Abortion

Regulation and Questions o f Equal Protection, 44

Stan. L. Rev. 261, 292 (1991) (quoting H.S. Pomeroy,

The Ethics of Marriage 97 (1888)); see also id. at 293

(quoting physician in lecture opposed to interruption

of intercourse: “She sins because she shirks those

responsibilities for which she was created.”).

Even as times changed, and women began

entering the workforce in greater numbers, they

were constrained by the longstanding and religiously

imbued vision of women as mothers and wives.

As this Court recognized in Frontiero, “ [a]s a result

of notions such as [those articulated in Justice

Bradley’s concurrence in Bradwell], our statute books

gradually became laden with gross, stereotyped

distinctions between the sexes.” 411 U.S. at 685.9

9 Concomitant with a restricted vision of women’s roles were

constraints on the roles of men. In the idealized role, men were

heads of households, the wage earners, and the actors in the

polity. They were not caretakers, for example. See, e.g., Nev.

Dep’t of Human Res. v. Hibbs, 538 U.S. 721, 736 (2003)

(recognizing that the historic “[s]tereotypes about women’s

domestic roles are reinforced by parallel stereotypes presuming

a lack of domestic responsibilities for men”). And, for both

23

Those statutes were often upheld by this Court. For

example, in Muller v. Oregon, this Court upheld

workday limitations for women because “healthy

mothers are essential to vigorous offspring, [and

therefore] the physical well-being of woman becomes

an object of public interest and care in order to

preserve the strength and vigor of the race.” 208

U.S. 412, 421 (1908); see also Hoyt u. Florida, 368

U.S. 57, 62 (1961) (holding women should be exempt

from mandatory jury duty service because they are

“still regarded as the center of home and family life”).

But just like society’s views of race evolved,

society’s views of women progressed, and gradually

women’s ability to pursue goals other than, or

in addition to, becoming wives and mothers

was recognized. Indeed, the passage of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 was a step forward for race

and gender equality because Title VII of the Act

barred discrimination based on sex and race in

the workplace. The protection against gender

discrimination, like that for race, passed in the face

of religious objection and without the proposed

exemption that sought to permit religiously affiliated

organizations to engage in gender-based employment

discrimination.10

sexes, these visions were idealized, and unrealistic for many

households, particularly those of the working poor, where

women as well as men labored outside the home.

10 But see Title IX, Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C.

§ 1681(a)(3) (providing an exemption for “an educational

institution which is controlled by a religious organization if the

application of [Title IX] would not be consistent with the

religious tenets of such organization”).

24

Slowly the courts, too, began dismantling the

notion that divine ordinance and the law of the

Creator requires women to be confined to roles as

wives and mothers. For example, this Court held

a state law that treated girls’ and boys’ age of

majority differently for the purposes of calculating

child support unconstitutional, rejecting the state’s

argument that girls do not need support for as long

as boys because they will marry quickly and will not

need a secondary education. Stanton v. Stanton, 421

U.S. 7 (1975). This Court reasoned:

No longer is the female destined solely

for the home and the rearing of the

family, and only the male for the

marketplace and the world of ideas.

Women’s activities and responsibilities

are increasing and expanding.

Coeducation is a fact, not a rarity. The

presence of women in business, in the

professions, in government and, indeed,

in all walks of life where education is a

desirable, if not always a necessary,

antecedent is apparent and a proper

subject of judicial notice.

Id. at 14-15 (internal citation omitted); see also Orr u.

Orr, 440 U.S. 268, 279 n.9 (1979) (holding

unconstitutional law that allowed alimony from

husbands but not wives, as “part and parcel of a

larger statutory scheme which invidiously

discriminated against women, removing them from

the world of work and property and ‘compensating’

them by making their designated place ‘secure’”).

Additionally, when striking a ban on the admission

25

of women to the Virginia Military Institute, this

Court noted:

“Inherent differences” between men and

women . . . remain cause for celebration,

but not for denigration of the members

of either sex or for artificial constraints

on an individual’s opportunity. Sex

classifications . . . may not be used, as

they once were . . . to create or

perpetuate the legal, social, and

economic inferiority of women.

United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515, 533-34

(1996) (internal citations omitted).

The Court has also dismantled notions that

women could be barred from certain jobs because of

their reproductive capacity, International Union v.

Johnson Controls, Inc., 499 U.S. 187 (1991), and has

affirmed legislation that addresses “the fault-line

between work and family - precisely where sex-based

overgeneralization has been and remains strongest,”

Hibbs, 538 U.S. at 738. The courts and Congress

have thus recognized that “denial or curtailment of

women’s employment opportunities has been

traceable directly to the pervasive presumption that

women are mothers first, and workers second.” Id. at

736 (internal citations and quotations omitted).

As with race, this progress has been tested by

religious liberty defenses to the enforcement of anti-

discrimination measures. Religious schools resisted

the notion that women and men must receive equal

compensation by invoking the belief that the “Bible

clearly teaches that the husband is the head of the

house, head of the wife, head of the family.” Dole u.

26

Shenandoah Baptist Church, 899 F.2d 1389, 1392

(4th Cir. 1990). The courts rejected this claim,

emphasizing a state interest of the “highest order” in

remedying the outmoded belief that men should be

paid more than women because of their role in

society. Id. at 1398 (citations and quotations

omitted); see also EEOC v. Fremont Christian Sch.,

781 F.2d 1362 (9th Cir. 1986) (same); EEOC v. Tree

of Life Christian Schs., 751 F. Supp. 700 (S.D. Ohio

1990) (same).

Even today, laws and policies designed to

protect against gender discrimination continue to

face challenges in the name of religious belief, but

courts have limited such arguments. See, e.g.,

Hamilton u. Southland Christian Sch., Inc., 680 F.3d

1316, 1320 (11th Cir. 2012) (reversing summary

judgment for religious school that claimed a religious

right, based on its opposition to premarital sex, to

fire teacher for becoming pregnant outside of

marriage, holding that the school seemed “more

concerned about her pregnancy and her request to

take maternity leave than about her admission that

she had premarital sex”); Ganzy v. Allen Christian

Sch., 995 F. Supp. 340, 350 (E.D.N.Y. 1998) (holding

that a religious school could not rely on its religious

opposition to premarital sex as a pretext for

pregnancy discrimination, noting that “it remains

fundamental that religious motives may not be a

mask for sex discrimination in the workplace”);

Vigars v. Valley Christian Ctr., 805 F. Supp. 802,

808-10 (N.D. Cal. 1992) (same).11

11 Attempts to use religion to discriminate are not limited to

race and sex. See, e.g., The Leadership Conference Education

Fund, Striking a Balance: Advancing Civil and Human Rights

27

II. THIS COURT SHOULD NOT ALLOW THE

EMPLOYERS HERE TO RESURRECT

THE DISCREDITED NOTION THAT

RELIGIOUS BELIEFS MAY TRUMP A

LAW DESIGNED TO ENSURE EQUAL

PARTICIPATION IN SOCIETY.

The contraception rule, like Title VII and other

anti-discrimination measures, is an effort to address

the vestiges of gender discrimination. And like those

other anti-discrimination laws, this rule is being

resisted in the name of religion.12 The employers

before this Court argue that they are entitled to

evade the mandates of the law based on their

religious beliefs. As discussed supra, the argument

that religious belief justifies discrimination, the

While Preserving Religious Liberty (Jan. 2016),

http://civihrightsdocs.info/pdf/reports/2016/religious-liberty-

report-WEB.pdf. For example, religion has been invoked in an

attempt to justify discrimination based on marital status, see

Swanner v. Anchorage Equal Rights Comm’n, 874 P.2d 274

(Alaska 1994), and discrimination based on sexual orientation,

see, e.g., Peterson v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 358 F.3d 599 (9th Cir.

2004); Matthews v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 417 F. App’x 552 (7th

Cir. 2011); Br. of Amici Curiae Lambda Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc. in Supp. of Respondent. It is also a

concern for people with disabilities, who have historically faced

limitations from religiously affiliated group homes, including

the refusal to allow them to live with romantic partners, even if

married. See Forziano v. Indep. Grp. Home Living Program,

No. 13-cv-0370, 2014 WL 1277912 (E.D.N.Y. Mar. 26, 2014).

12 Although the employers in this case have religious objections

to the rule, not all people of faith share their objection. See, e.g.,

Tom Howell, Jr., Catholic Hospitals are OK with Obama

Contraception Mandate, Protections, Wash. Times, July 9, 2013,

http://www.washingtontimes.eom/blog/inside-politics/2013/jul/9/

report-catholic-hospital-ok-contraception-mandate/ (last visited

Feb. 9, 2016).

28

http://civihrightsdocs.info/pdf/reports/2016/religious-liberty-report-WEB.pdf

http://civihrightsdocs.info/pdf/reports/2016/religious-liberty-report-WEB.pdf

http://www.washingtontimes.eom/blog/inside-politics/2013/jul/9/

denial of rights, or the relinquishment of benefits is

an old, discredited theory that should, once again, be

rejected.

The contraception rule has, and will continue

to, transform women’s lives, by enabling women to

decide if and when to become a parent and allowing

women to make educational and employment choices

that benefit themselves and their families.13

“Women who can successfully delay a first birth and

plan the subsequent timing and spacing of their

children are more likely than others to enter or stay

in school and to have more opportunities for

employment and for full social or political

participation in their community.” Susan A. Cohen,

The Broad Benefits of Investing in Sexual and

Reproductive Health, 7 Guttmacher Rep. on Pub.

Pol’y 5, 6 (2004). The availability of the oral

contraceptive pill alone is associated with roughly

one-third of the total wage gains for women born

from the mid-1940s to early 1950s; a 20% increase in

women’s college enrollment; and a sharp increase in

the percentage of women lawyers, judges, doctors,

dentists, architects, economists, and engineers. See

Martha J. Bailey et al., The Opt-in Revolution?

Contraception and the Gender Gap in Wages, 19, 26

(Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Research Working Paper No.

17922, 2012), http://www.nber.org/ papers/wl7922

(last visited Feb. 9, 2016); Claudia Goldin &

13 Moreover, as the Government and other amici argue, the rule

is also important to protect women’s health. This is particularly

true for women of color who disproportionately suffer from

health conditions that can be aggravated by pregnancy. See Br.

of Amici Curiae Nat’l Health Law Program in Supp. of

Respondent.

29

http://www.nber.org/

Lawrence F. Katz, The Power of the Pill: Oral

Contraceptives and Women’s Career and Marriage

Decisions, 110 J. Pol. Econ. 730, 749 (2002). As this

Court has recognized, “ [tjhe ability of women to

participate equally in the economic and social life of

the Nation has been facilitated by their ability to

control their reproductive lives.” Planned Parenthood

of Se. Pa. v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833, 856 (1992).

Moreover, the contraception rule contributes

to the dismantling of outmoded sex stereotypes,

including those predicated on religion, because

contraception offers women the tools to decide

whether and when to become mothers. The rule

therefore remedies the notion, long endorsed by

society, that “a woman is, and should remain the

‘center of home and family life.’” Hibbs, 538 U.S. at

729 (quoting Hoyt, 368 U.S. at 62). It reinforces the

fundamental premise underlying access to

contraception, namely that society no longer

demands that women either accept pregnancy or

refrain from nonprocreative sex. As this Court has

so eloquently stated, “these sacrifices [to become a

mother] have from the beginning of the human race

been endured by woman with a pride that ennobles

her in the eyes of others . . . [but they] cannot alone

be grounds for the State to insist she make the

sacrifice.” Casey, 505 U.S. at 852.

The contraception rule changes women’s

status in one other fundamental respect. Health care

plans that cover preventive care that men need, but

not that women need, send the message that women

are second-class citizens, and that they are not

employees equally valued by the employer.

30

For these reasons, contraception is more than

a service, device, or type of medicine. Meaningful

access to birth control is an essential element of

women’s constitutionally protected liberty. See

Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558, 567 (2003)

(recognizing that sodomy laws do not simply regulate

sex but infringe on the liberty rights of gays and

lesbians). An exemption countenancing a religious

objection to contraception suggests that religious

objections are more important than women’s equality

in our society.

The contraception rule is thus an essential

step to further equal opportunities for women.

Nothing evidences the importance of the rule more

clearly than the following fact: Today, approximately

half of pregnancies are unintended. Guttmacher

Institute, Unintended Pregnancy in the United States

(July 2015), available at http://www.guttmacher.org/

pubs/FB-Unintended-Pregnancy-US.html. Several

facts underlie this statistic: Many women are unable

to afford contraception — even with insurance -

because of high co-pays or deductibles, see generally

Su-Ying Liang et al., Women’s Out-of-Pocket

Expenditures and Dispensing Patterns for Oral

Contraceptive Pills Between 1996 and 2006,

83 Contraception 528, 531 (2011); others cannot

afford to use contraception consistently, see

Guttmacher Institute, A Real-Time Look at the

Impact of the Recession on Women’s Family Planning

and Pregnancy Decisions 5 (Sept. 2009),

http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/RecessionFP.pdf;

and costs drive women to less expensive and less

effective methods, see Jeffrey Peipert et al.,

Continuation and Satisfaction of Reversible

Contraception, 117 Obstetrics & Gynecology 1105,

31

http://www.guttmacher.org/

http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/RecessionFP.pdf

1105-06 (2011) (reporting that many women do not

choose long-lasting contraceptive methods, such as

intrauterine devices (“IUDs”), in part because of the

high upfront cost).14

The contraception rule lifts these barriers,

with the promise of increased opportunity for women.

A study in St. Louis, which essentially simulated the

conditions of the rule, illustrates its impact:

Physicians provided counseling and offered nearly

10,000 women contraception, of their choosing,

free of cost. Jeffrey Peipert et al., Preventing

Unintended Pregnancies by Providing No-Cost

Contraception, 120 Obstetrics & Gynecology 1291

(2012). In this setting, 75% of the participants opted

for a long-acting reversible contraceptive method,

with 58% choosing an IUD. Compare id. at

1293, with Guttmacher Institute, Fact Sheet:

Contraceptive Use in the United States (Oct. 2015),

http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb_contr_use.html

(showing approximately 10% of all contraceptive

users have IUDs as their method). As a result,

among women in the study, the unintended

pregnancy rate plummeted, and the abortion rate

was less than half the regional and national rates.

Colleen McNicholas et al., The Contraceptive

CHOICE Project Round Up, 57 Clinical Obstetrics &

Gynecology 635 (Dec. 2014). See also Br. of Amici

14 Long-acting methods of contraception, like IUDs, are

particularly effective because there is less room for human

error, unlike, for example, oral contraceptive pills. See id. at

1111-12 (noting that the majority of unintended pregnancies

result from “incorrect or inconsistent” contraception use, but

IUDs are not “user-dependent” and thus are highly effective).

32

http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb_contr_use.html

Curiae the Guttmacher Institute in Supp. of the

Gov’t.

For all of these reasons, the contraception rule

furthers the government’s compelling interest in

ensuring women’s equality. Indeed, this Court in

Hobby Lobby recognized the importance of “ensuring

that the employees of these [objecting] entities have

precisely the same access to all FDA-approved

contraceptives as employees of companies whose

owners have no religious objections to providing such

coverage.” 134 S. Ct. at 2759-60.

This Court held that the accommodation now

being challenged in these cases was a least

restrictive alternative to fulfilling the government’s

compelling interests. It did so specifically noting that

“the effect of the HHS-created accommodation on the

women employed by Hobby Lobby and the other

companies involved in these cases would be precisely

zero.” Id. The same cannot be said in this case.

If this Court accepts the employers’ arguments

here, the employees would undisputedly not have

“precisely the same access” to contraceptives as

employees of employers who have no religious

objection to covering contraception. Instead, the

Court would be allowing the employers to deprive

their employees of a benefit guaranteed by law,

namely, contraception coverage from their health

insurance company. The government’s compelling

interests will be completely undermined because,

as the government and other amici explain in detail,

there is no other way to further the government’s

compelling interest in ensuring seamless contra

ception coverage for women. See Br. of Amici Curiae

Health Policy Experts in Supp. of Respondents.

33

Given the absence of feasible alternatives to

the contraception rule, a decision upholding the rule

in this case will not be breaking new ground, but

instead will be following a well-established path.

Although our country has made great progress

toward achieving women’s equality, more work is

needed, and the contraception rule is a crucial step

forward.

CONCLUSION

The Court should affirm the judgments below.

Respectfully Submitted,

Brigitte Amiri

Counsel o f Record

Louise Melling

Jennifer Lee

Steven R. Shapiro

A m e r i c a n C iv il L ib e r t ie s

U n io n F o u n d a t io n

125 Broad Street

New York, NY 10004

(212) 549-2500

bamiri@aclu.org

Daniel Mach

Heather L. Weaver

A m e r ic a n C iv il L ib e r t ie s

U n io n F o u n d a t io n

915 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Dated: February 16, 2016

34

mailto:bamiri@aclu.org

RECORD PRESS, INC.

229 West 36th Street, New York, NY 10018— 67473— Tel. (212) 619-4949

www.recordpress.com

http://www.recordpress.com