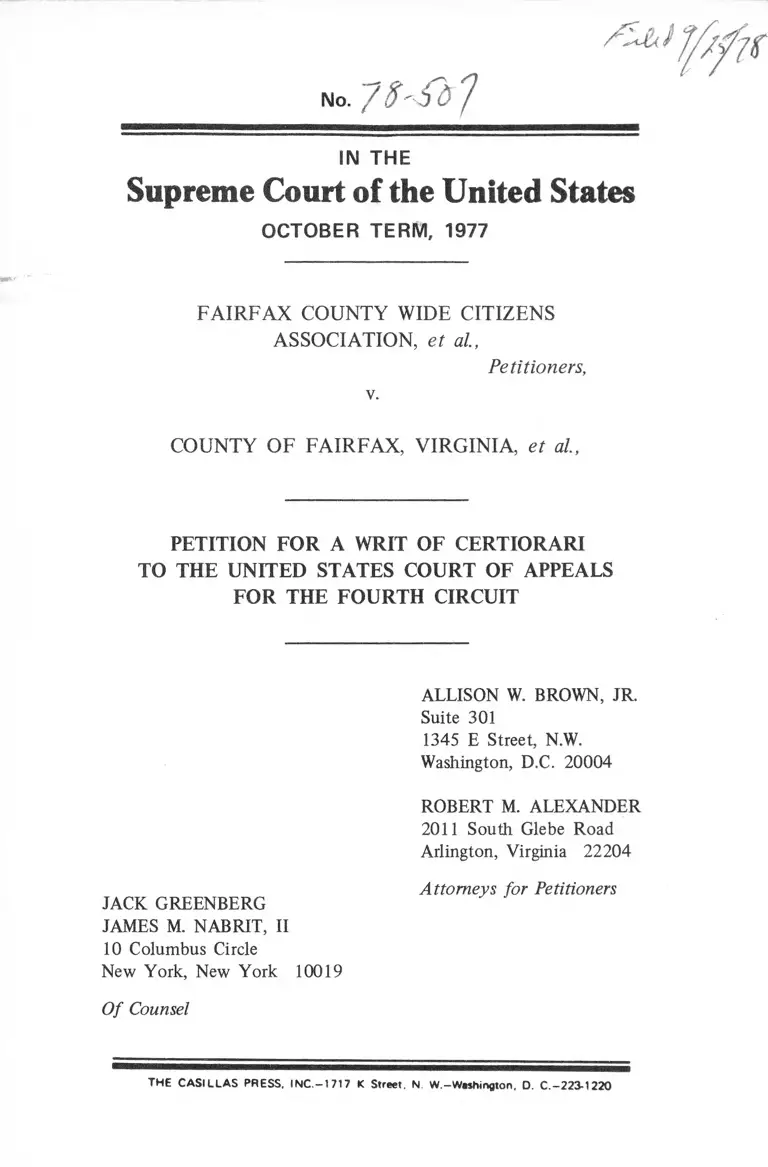

Fairfax County Wide Citizens Association v. Fairfax County, VA Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

September 25, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Fairfax County Wide Citizens Association v. Fairfax County, VA Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1978. d9390e60-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8cd197ac-b260-476f-9cda-b3779581a0b5/fairfax-county-wide-citizens-association-v-fairfax-county-va-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

No. / 8 'S d 7

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1977

FA IR FA X COUNTY WIDE CITIZENS

ASSOCIATION, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

COUNTY O F FA IRFAX , VIRGINIA, et al.,

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

ALLISON W. BROWN, JR.

Suite 301

1345 E Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20004

ROBERT M. ALEXANDER

2011 South Glebe Road

Arlington, Virginia 22204

Attorneys for Petitioners

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, II

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Of Counsel

THE C A S IL L A S PRESS. IN C .-1717 K Street. N. W.-Washington, D. C.-223-1220

INDEX

OPINIONS BELOW .................................................................... 2

JURISDICTION....................................................... 2

QUESTION P R E SE N T E D ................................... 2

STATEMENT ............................................................................. 2

A. The settlement agreement — its enforce

ment by the district court .............................. 2

B. The court of appeals’ decision . . . . . . 4

C. Further proceedings in the district court . . . 6

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W R I T ..... 6

CONCLUSION...................................................... 12

APPENDIX A ..................................................................... la

APPENDIX B ..................................................................... 15a

APPENDIX C ..................................................................... 17a

APPENDIX D ..................................................................... 18a

CITATIONS

Cases:

Albright v. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.,

350 F. Supp. 341 (W.D. Pa., 1972), affd

485 F.2d 678 (C.A. 3, 1973), cert, denied

416 U.S. 951 ............................................

Page

8

All States Investors, Inc. v. Bankers Bond Co.,

343 F.2d 618 (C.A. 6, 1965), cert, denied,

382 U.S. 830 ................................................................ 11

Aro Corp. v. Allied Witan Co.,

531 F.2d 1368 (C.A. 6, 1976), cert, denied,

429 U.S. 862 ................................................................ 6,9

Autera v. Robinson,

419 F.2d 1197 (C.A.D.C., 1 9 6 9 ) .............................. 11

Beirne v. Fitch Sanitarium,

167 F. Supp. 652 (S.D.N.Y., 1 9 5 8 ) ......................... 11

Bernstein v. Brenner,

320 F. Supp. 1080 (D.D.C., 1 9 7 0 ).............................. 8

Chief Freight Lines Co. v. Local Union No. 886,

514 F.2d 572 (C.A. 10, 1 9 7 5 ) .................................. 6

Cia Anon Venezolana de Navegacion v. Harris,

374 F.2d 33 (C.A. 5, 1 9 6 7 ) ........................ ..... 11

Coburn v. Cedar Valley Land Co.,

138 U.S. 196 (1 8 9 1 )...................................................... 10, 11

Cummins Diesel Michigan, Inc. v. The Falcon,

305 F.2d 721 (C.A. 7, 1962) ................................... 11

Dugas v. American Surety Co.,

300 U.S. 414 (1 9 3 7 )...................................................... 7

Haldeman v. United States,

23 L. Ed. 433 ( 1 8 7 6 ) ................................................. 8

Hall v. People to People Health Foundation, Inc.,

493 F.2d 311 (C.A. 2, 1974)

jj

Page

7

I l l

Ingalls Iron Works Co. v. Ingalls,

111 F. Supp. 151 (N.D. Ala., 1 9 5 9 ) ......................... 7, 11

Kelly v. Greer,

334 F.2d 434 (C.A. 3, 1965) ................................... 6, 10

Kelly v. Greer,

365 F.2d 669 (C.A. 3, 1966), cert, denied,

385 U.S. 1035 ................................................................ 6, 10

Kelsey v. Hobby,

41 U.S. 269 ( 1 9 4 2 ) ...................................................... 10

Kukla v. National Distillers Products Co.,

483 F.2d 619 (C.A. 6, 1973) ................................... 11

Landau v. St. Louis Public Service Co.,

364 Mo. 1134, 273 S.W. 2d 255 (1954) . . . . 8

Langlois v. Langlois,

5 A.D.2d 75, 169 N.Y.S. 2d 170 (1957) . . . . 8

Pacific Railroad of Missouri v. Missouri Pacific

Railway Co., I l l U.S. 505 (1 8 8 4 ) .............................. 7

Robinson v. E. P. Dutton & Co.,

45 F.R.D. 360 (S.D.N.Y., 1968)................................... 8

Skyline Sash Co. v. Fidelity and Casualty Co.

o f New York, 378 F.2d 369 (C.A. 3, 1967),

affd 267 F. Supp. 577 (W.D. Pa., 1966) . . . . 6, 10

Williams v. First National Bank,

216 U.S. 582 (1910)

Page

9

IV

Constitution, Statutes, Rules:

U. S. Constitution, Fourteenth A m endm ent.................... 2

42 U.S.C. Sec. 1 9 8 1 ........................................................... 2

42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983 ........................................................... 2

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 60(b)(6) . . . 4

Miscellaneous:

124 Cong. Rec. H1553 ff. ( 1 9 7 8 ) ................................... 7

124 Cong. Rec. H1569 ff. ( 1 9 7 8 ) ................................... 7

Annual Report of the Director of the

Administrative Office of the United

States Courts ( 1 9 7 7 ) ...................................................... 1 ,9

13 Wright, Federal Practice and Procedure

Sec. 3523 .......................................................................... 7

Page

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1977

No.

FAIRFAX COUNTY WIDE CITIZENS

ASSOCIATION, et al,

v.

Petitioners,

COUNTY OF FAIRFAX, VIRGINIA, et al.,

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari issue

to review the decision and judgments of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in this case.1

1 Petitioners, in addition to Fairfax County Wide Citizens Associa

tion, are Gum Springs Civic Association, Springdale Civic Association,

William L. and Jeanne G. Paige, Ulysses 0 . and Ada M. Scott, and

Roy and Evelyn A. Brent. Respondents, in addition to County of

Fairfax, Virginia, are Joseph Alexander, Martha V. Pennino, John

F. Herrity, Alan H. Magazine, Audrey Moore, James M. Scott, Marie

B. Travesky, John P. Schacochis, and Warren I. Cikins, individually

and as members of the Board of Supervisors of County of Fairfax,

Virginia; and Douglas B. Fugate, individually and as Virginia State

Highway Commissioner.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals (App. A., infra, pp.

la-14a) is reported at 571 F.2d 1299. The memorandum

opinion of the district court (App. D, infra, pp. 18a-23a)

is not reported.

JURISDICTION

The judgments resulting from the appeal and cross

appeal were entered by the court of appeals on March

6, 1978 (App. B, infra, pp. 15a-16a). A timely petition

for rehearing and suggestion for rehearing en banc was de

nied by the court of appeals by its order entered April

28, 1978 (App. C, infra, p. 17a). On July 19, 1978,

Justice Brennan extended the time for filing a petition

for a writ of certiorari to and including September 25, 1978.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

Sec. 1254(1).

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether a district court’s jurisdiction to enforce a set

tlement agreement which terminated a federal civil rights

action pending before it is defeated by the fact that the

parties are citizens of the same state.

STATEMENT

A. The settlement agreement — its enforce

ment by the district court

This action was commenced in August 1971 by three

civic associations and six black residents of Fairfax County

Virginia, alleging racial discrimination in the delivery of

public services, in violation of 42 U.S.C. Secs. 1981, 1983,

and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Specifically, plaintiffs alleged that as a result of dis

3

criminatory policies and practices of the defendant County,

members of its board of supervisors, and Virginia State

Highway Commissioner Douglas B. Fugate, the predomi

nantly black neighborhoods of Fairfax County, in con

trast to the white neighborhoods, were generally charac

terized by unpaved and substandard streets, inadequate

storm drainage, lack of curbs and gutters, and lack of

public sidewalks. Plaintiffs requested a mandatory injunc

tion compelling the defendants to upgrade and pave the

streets in question, and to construct adequate drainage

facilities, curbs, gutters, and sidewalks (infra, pp. 3a-4a).

Following the denial of defendants’ motions to dismiss,

the case was set for trial on June 1, 1971 (infra, p. 4a).

On May 31, 1972, following extensive pre-trial dis

covery, plaintiffs entered into two separate settlement

agreements. The first, between plaintiffs and defendant

Fugate, required the State to upgrade and pave six streets

located in black neighborhoods in Fairfax County (infra,

p. 4a). The second settlement agreement, between plain

tiffs and the County defendants, required the latter to up

grade and pave 76 streets in black neighborhoods within

a three-year period (infra, p. 4a). In view of the settle

ment of the litigation, plaintiffs, pursuant to agreement

of the parties, moved for dismissal of the suit and on

June 1, 1972, the district entered separate orders dis

missing the action as to the State and County defendants.

(infra, p. 5a).

Thereafter, the State substantially performed its obli

gations under its settlement agreement. However, the

County only partly performed its obligations and in the

ensuing three years upgraded 25 streets in black neigh

borhoods. In the spring of 1975, the County concluded

that it lacked authority under state law to perform fur

ther its obligations under the settlement agreement, and

on April 28, 1975, the County’s board of supervisors

4

adopted a resolution repudiating the agreement (infra,

p. 5a).

On August 7, 1975, plaintiffs moved in the district

court under Rule 60(b) (6), F.R. Civ. P., to vacate the

dismissal order of June 1, 1972, and for an order com

pelling specific performance of the County’s settlement

agreement. Plaintiffs, in support of their motion, disputed

the County’s claim that state law prohibited its perform

ance of the settlement agreement and asserted that, in any

event, enforcement of the statutes and regulations relied

on by the County should be enjoined because they were

administered and enforced in an arbitrary, capricious, and

racially discriminatory manner (infra, p. 6a). On January

30, 1976, under authority of Rule 60(b) (6), F.R. Civ. P.,

the district court granted plaintiffs’ motion to vacate the

dismissal and reopened the proceeding against the County

(infra, p. 6a). Following discovery procedures and a trial

of issues pertaining to the County’s breach of the settle

ment agreement, the district court, on November 26, 1976,

entered its order directing the County to perform the re

mainder of the agreement by upgrading and paving 43

streets still in controversy (infra, p. 6 a).

B. The court of appeals’ decision

Appeals from the district court’s order were taken by

both the County and plaintiffs, the latter claiming that cer

tain additional relief should have been granted. Ruling on 2

2 Rule 60(b) (6), F.R. Civ. P., provides in relevant part that, “On

motion and upon such terms as are just, the court may relieve a

party or his legal representative from a final judgment, order, or

proceeding for the following reasons: . . . (6) any other reason

justifying relief from the operation of the judgment.”

5

the County’s appeal, the court of appeals held that, upon

the County’s repudiation of the settlement agreement which

had terminated the litigation pending before it, the district

court had authority under Rule 60(b) (6) to vacate its

prior dismissal order and restore the case to its docket

(infra, p. 8a). However, the court of appeals held that

upon the district court’s vacation of its prior order of dis

missal, that court only had authority to restore the case

to its trial docket for the purpose of allowing plaintiffs

to prove their case and to obtain relief on the merits of

their original claim. Thus, the court held, because plaintiff

and the County defendants lack diversity of citizenship,

the district court did not have jurisdiction to enforce the

settlement agreement against the breaching party (infra,

pp. 13a-14a). Accordingly, the court of appeals reversed the

order of specific performance entered by the district court

against the County and remanded the proceeding to that

court to allow plaintiffs to proceed to the trial of their

original case.

In reaching its decision, the court of appeals held that

although the original complaint stated a federal civil rights

claim over which the district court had jurisdiction, the

settlement agreement was a private contract which, be

cause of the nondiversity of the parties, could only be en

forced by plaintiffs bringing a separate action in state court

(infra, p. 13a). Finally, the court of appeals noted that

the settlement agreement had not been approved or incorpo

rated into an order of the district court. This omission,

the court held, would not have affected the district court’s

authority to enforce the agreement if there had been an in

dependent ground of federal jurisdiction, such as diversity

of citizenship, but since such ground is lacking here the

district court was not empowered to enforce the agree

ment (infra, p. 8a).

6

C. Further proceedings in the district court

Pursuant to the court of appeals’ order of remand, the

district court set the case down for trial on the basis of

plaintiffs’ original complaint. Plaintiffs’ motion for a stay

of proceedings pending the filing of a petition for certio

rari was denied by the district court, and trial was held on

July 10, 1978. As of September 25, 1978, the date of fil

ing of this petition, the district court still had the matter

under advisement.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

The court of appeals’ ruling that the district court

lacked jurisdiction to enforce the settlement agreement

reached in litigation pending before it is totally without

precedent in the reported authorities and is in direct con

flict with the decisions of at least three other circuits.

The Sixth, Third, and Tenth Circuits have specifically held

that issues pertaining to compliance with a settlement

agreement that terminated litigation in a district court

may properly be resolved by that court upon the filing

of a supplemental motion or petition in the original pro

ceeding, and that an independent action need not be ini

tiated for such purpose. Since, as these three circuit

courts recognize, an action to compel compliance with a 3

3 See Aro Corp. v. Allied Witan Co., 531 F.2d 1368 (C.A. 6, 1976),

cert, denied, 429 U.S. 862; Kelly v. Greer, 334 F.2d 434 (C.A. 3,

1965); Kelly v. Greer, 365 F.2d 669 (C.A. 3, 1966), cert, denied

385 U.S. 1035; Chief Freight Lines Co. v. Local Union No. 886,

514 F.2d 572 (C.A. 10, 1975); Skyline Sash Co. v. Fidelity and

Casualty Co. o f New York, 378 F.2d 369 (C.A. 3, 1967), aff’g

267 F.Supp. 577 (W.D. Pa., 1966).

7

settlement agreement may be brought in a proceeding

that is supplemental or ancillary to the original suit, there

clearly is no need to establish a separate and independent

basis of federal jurisdiction for this purpose, as the court

of appeals held herein.4

The court of appeals’ decision in this case should be

reversed, not only because it is unprecedented and con

flicts with the decisions of other circuits, but also be

cause it poses a serious threat to the efficient administra

tion of justice by discouraging, rather than encouraging,

the settlement of cases in the district courts. Seventy-five

percent of all cases filed in the district courts are non

diversity cases in which jurisdiction is based either on the

fact that the suit involves a federal question or that the

United States is a party.5 In federal question cases, if

there is no diversity between the parties, based on the

court of appeals’ decision, the only way that litigants can

be assured that a settlement agreement they might enter

into will be enforceable by the court where the case is

4 The authority to enforce a settlement agreement reached by par

ties in pending litigation has been said to fall within a federal court’s

“ancillary jurisdiction.” 13 Wright, Federal Practice and Procedure,

Sec. 3523, n. 2, citing Hall v. People to People Health Foundation,

Inc., 493 F.2d 311, 313 n. 3. (C.A. 2, 1974). And see Ingalls Iron

Works Co. v. Ingalls, 111 F. Supp. 151, 154 (N.D. Ala., 1959). It

is well settled that absence of diversity of citizenship does not de

feat ancillary jurisdiction. Pacific Railroad of Missouri v. Missouri

Pacific Railway Co., I l l U.S. 505, 522 (1884); Dugas v. American

Surety Co., 300 U.S. 414, 428 (1937).

5 Annual Report of the Director of the Administrative Office of

the United States Courts, Table C2 (1977). A bill that would abolish

diversity jurisdiction passed the House of Representatives on Febru

ary 28, 1978, by a vote of 266 to 133, and now pending in the

Senate. See 124 Cong. Rec. H1553-1561, H1569-1570, 95th Cong.

2nd Sess. (1978).

pending is by having it approved and incorporated into an

order of the court. The imposition of such requirements

is totally contrary to the more informal practice that is

followed by untold numbers of litigants who settle a pend

ing case through agreement and then move for dismissal,

as was done in the instant case. In Haldeman v. United

States, 23 L. Ed. 433, 434 (1876) this Court recognized

that:

Suits are often dismissed according to

the agreement of the parties, and a gen

eral entry made to that effect, without

incorporating the agreement in the record,

or even placing it on file. 6̂ ̂

The formal requirements of approval and incorporation

in an order that the court of appeals would impose on

parties as conditions of having their settlement agreement

enforceable by the court where the case is pending would

discourage the informal type settlement that today is fre

quently resorted to by parties wishing to terminate their

litigation quickly and with a minimum of expense. In

addition to the extra time and cost to the litigants that

is involved in going before a judge and having a settle

ment agreement incorporated into an order, the require

ments that the court of appeals would impose create addi

tional duties for already overburdened federal judges. Be

fore approving a settlement agreement, a judge inevitably * 3

6 Also, see for example, Robinson v. E.P. Dutton & Co., 45 F.R.D.

360 (S.D. N.Y., 1968); Albright v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., 350

F. Supp. 341, 344, 348 (W.D. Pa., 1972), aff’d 485 F.2d 678 (C.A.

3, 1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S. 951; Bernstein v. Brenner, 320 F.

Supp. 1080 (D.D.C., 1970); Landau v. St. Louis Public Service Co.,

364 Mo. 1134, 273 S.W. 2d 255 (1954); Langlois v. Langlois, 5 A.D

2d 75, 169 N.Y.S. 2d 170 (1957).

9

must spend time familiarizing himself with its provisions

and, in most instances, before the judge will enter an

order incorporating a settlement he will require a hearing

for the purpose of allowing the parties to explain the

agreement and present their respective positions.

It has never been doubted that, “Compromises of dis

puted claims are favored by the courts.” Williams v. First

National Bank, 216 U.S. 582, 595 (1910). Yet, the court

of appeals’ decision would be a serious impediment to the

settlement of a substantial amount of litigation in the fed

eral courts. In a recent 12-month period there were 130,567

civil actions filed in the federal district courts and 92 per

cent of those cases (excluding land condemnation proceed

ings) were disposed of without trial.7 It cannot be doubted

that voluntary settlements without formal court action ac

counted for a substantial number of the cases that were

disposed of without trial. However, the court of appeals’

decision would in effect elirriinate this form of settlement

for federal litigants, and thus impair, rather than assist,

the efficient administration of justice.

II.

The court of appeals acknowledges in its opinion that

its decision conflicts with the Sixth Circuit’s ruling in

Aro Corp. v. Allied Witan, supra, where, on facts virtually

indistinguishable from those present here, a district court

was held to have jurisdiction to enforce a settlement

agreement, despite nondiversity of citizenship. The court

of appeals herein failed to note, however, that its decision

also conflicts, as shown supra, n. 3, p. 6, with the Third

■7

Annual Report of the Director of the Administrative Office of the

United States Courts, supra, Tables C2, C4 (1977).

10

Circuit’s decisions in Kelly v. Greer, supra, and the Chief

Freight Lines, supra, and Skyline Sash, supra, decisions

of the Tenth and Sixth Circuits, respectively. While it

is true that in the latter two cases diversity of citizenship

existed between the parties, the decisions are nevertheless

relevant here for, if, as those cases hold, a district court

has jurisdiction to resolve a dispute over a settlement

agreement entered into a suit properly pending before it

on the basis of a supplemental petition or motion filed

in the original proceeding, there obviously is no reason

to require an independent basis for jurisdiction, as the

court of appeals herein would have it.

Not only does the court of appeals’ decision conflict

with the foregoing authorities, but it is also contrary to

Coburn v. Cedar Valley Land Co., 138 U.S. 196, 221-

223 (1891), where this Court specifically rejected the

contention that a federal court lacks authority to enforce

in the original proceeding a settlement agreement reached

in a pending suit. After considering cases from the English

courts holding that a separate action for specific enforce

ment was necessary to enforce certain settlement agree

ments, the Court held the controlling principle to be that

where the agreement covers only matters encompassed by

the proceeding in which the agreement was reached, the

court has jurisdiction to enforce it by “motion or peti

tion in the original suit.” 138 U.S. at 223. See also Kelsey

v. Hobby, 41 U.S. 269, 277 (1842). Since it is unquestioned

in the instant case that the settlement agreement is limited

to matters encompassed by the complaint, the court of

appeals’ decision constitutes an unwarranted departure

from the authority of the Coburn case.

Several other cases similar factually to Coburn are cited by

the court of appeals in its opinion herein, and although the

court seeks to distinguish them on various grounds, those cases

11

in fact demonstrate a state of the law totally at odds

with the court’s decision. Thus, the cited cases all illus

trate applications of the principle laid down by this Court

in the Coburn case, that a settlement agreement entered

into in a pending case, though it creates contract rights

new and different from the rights on which the original

claim was based, is nevertheless enforceable on a motion

or petition in the original proceeding. In each of the cited

cases the parties entered into a settlement agreement con

templating that upon performance of the agreement the

action would be dismissed. When breach occurred, the

other party sought specific performance in a proceeding

that was held to be properly part of the original suit. The

common characteristic of such cases is that the settlement

agreement is not necessarily intended initially by the par

ties to be incorporated into the court’s order. Rather, it

is only after one party breaches the agreement that its

terms become incorporated into the order as a means of

compelling specific performance. Upon analysis, it is clear

that there is no meaningful distinction between cases of

that nature and the case at bar. For, after the district

court herein vacated its dismissal order and reopened the

proceeding in response to plaintiffs’ motion under Rule

60(b) (6), this case stood in exactly the same posture

as the cited cases, i.e., enforcement was sought of a

breached settlement agreement that had been entered into 8

8 See Autera v. Robinson, 419 F.2d 1197 (C.A. D.C., 1969); Cia

Anon Venezolana De Navegacion v. Harris, 374 F.2d 33, 35 (C.A.

5, 1967); All States Investors, Inc. v. Bankers Bond Co., 343 F.2d

618, 624 (C.A. 6, 1965), cert, denied, 382 U.S. 830; Cummins

Diesel Michigan, Inc. v. The Falcon, 305 F.2d 721, 723 (C.A. 7,

1962); Kukla v. National Distillers Products Co., 483 F.2d 619,

621 (C.A. 6, 1973); Ingalls Iron Works Co. v. Ingalls, supra, 111

F. Supp. at 154-155; Beirne v. Fitch Sanitarium, 167 F. Supp. 652

(S.D. N.Y., 1958).

12

with the understanding that the action would be dismissed.

Upon the reopening of the original proceeding herein, the

district court, no less than the courts in the cited cases,

possessed jurisdiction to enforce the settlement agreement

as part of the original action, and there was no necessity

to regard plaintiffs’ motion for specific performance as a

new action for jurisdictional purposes.

For the foregoing reasons, a writ of certiorari should

issue to review the decision and judgments of the court of

appeals. However, as shown supra, p. 6, as of September

25, 1978, the date of filing of this petition, the district

court had under advisement its decision in the proceeding

on remand from the court of appeals. The district court’s

decision may be a basis for resolving the controversy be

tween the parties and thus moot the issue presented in

this petition. Therefore, petitioners respectfully request

this Court to withhold action on the petition, pending the

district court’s decision. Petitioners will advise the Court

as soon as the district court acts on the matter under

advisement.

CONCLUSION

ALLISON W. BROWN, JR.

Suite 301

1345 E Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20004

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, II

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ROBERT M. ALEXANDER

2011 South Glebe Road

Arlington, Virginia 22204

Attorneys for Petitioners

Of Counsel

September 1978

la

APPENDIX A

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-1190

Fairfax Countywide Citizens Association,

Gum Springs Civic Association,

Springdale Civic Association,

Cooktown Citizens Association,

William L. and Jeanne G. Paige,

Ulysses O. and Ada M. Scott,

Roy and Evelyn A. Brent,

Earnest W. and Margaret E. Gibson,

Appellees,

v.

County of Fairfax, Virginia,

Joseph Alexander,

Mrs. Martha V. Pennino,

John Herrity,

Alan H. Magazine,

Mrs. Audrey Moore,

James M. Scott,

Marie B. Travesky,

John P. Schacochis,

Warren I. Cikins,

individually and members, County

of Fairfax Board of Supervisors,

Appellants.

2a

No. 77-1248

Fairfax Countywide Citizens Association,

Gum Springs Civic Association,

Springdale Civic Association,

William L. and Jeanne G. Paige,

Ulysses O. and Ada M. Scott,

Roy and Evelyn A. Brent,

Appellants,

v.

County of Fairfax, Virginia,

Joseph Alexander,

Mrs. Martha V. Pennino,

John Herrity,

Alan H. Magazine,

Mrs. Audrey Moore,

James M. Scott,

Marie B. Travesky,

John P. Schacochis,

Warren I. Cikins,

individually and members, County of

Fairfax Board of Supervisors, and

Douglas B. Fugate, individually,

and as Virginia State Highway Commissioner,

Appellees.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, at Alexandria. Oren R. Lewis,

Senior District Judge.

Argued January 9, 1978 Decided March 6, 1978

Before WINTER, RUSSELL and WIDENER.

3a

Robert Lyndon Howell, Assistant County Attorney (Fred

eric Lee Ruck, County Attorney, on brief) for Appellants

in 77—1190; John J. Beall, Jr., Assistant Attorney General

(Anthony F. Troy, Attorney General of Virginia, Walter

A. McFarlane, Deputy Attorney General, on brief) for

Appellees in 77—1248; Allison W. Brown, Jr. (Robert M.

Alexander; Jack Greenberg and James M. Nabrit, III, on

brief) for Appellees and Cross-Appellants.

WINTER, Circuit Judge:

The County of Fairfax, Virginia (County) appeals from

an order of the district court directing County to perform

its remaining obligations under a 1972 settlement agree

ment between it and Fairfax Countywide Citizens Associa

tion (Association). Because we conclude that the district

court lacked jurisdiction to issue the order, we reverse.

I.

In August 1971, several citizens associations located in

Fairfax County, Virginia, and six individuals, filed suit in

the district court alleging racial discrimination in the de

livery of public services in violation of 42 U.S.C. §§1981,

1983 and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Specifically, plaintiffs claimed that a dispro

portionate number of unpaved and substandard roads in

Fairfax County were located in predominantly black

neighborhoods. Plaintiffs prayed a mandatory injunction

compelling County to pave and upgrade the roads in

question, including the construction of adequate drainage 1

1 Association also filed a cross-appeal in this case to require a modifi

cation of the district court’s order. Because we decide that the district

court lacked jurisdiction to enter an order enforcing the settlement

agreement, Association’s cross-appeal is rendered moot, and we will

not consider it further.

4a

facilities, curbs, gutters and sidewalks. In addition to

naming County and certain of its officials as defendants

to the action, plaintiffs also joined Douglas B. Fugate, the

Virginia State Highway Commissioner and chief administra

tor of the Virginia Highway System. Following a denial of

defendants’ motions to dismiss, the case was set for trial

on June 1, 1972.

On May 31, 1972, following extensive pretrial discovery,

plaintiffs entered into two separate settlement agreements.

The first, between plaintiffs and defendant Fugate, required

the Commonwealth to upgrade six streets located in black

neighborhoods in Fairfax County. These streets were al-

ready part of the Virginia secondary highway system and

therefore, within the jurisdiction of the State Highway De

partment.2 3 4 The second settlement agreement, between plain

tiffs and County, required County to upgrade seventy-six

additional roads in black neighborhoods within a three-year

period. None of these roads was, at the time of the agree

ment, included in the Virginia secondary highway system.

County, however, promised to “make every effort to have

the . . . streets, when improved, taken into the State Hdgh-

2

2 This was one of many civil rights suits filed in the wake of the Fifth

Circuit’s decision in Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, Mississippi, 437 F.2d

1286 (1971), aff’d on reh’g, 461 F.2d 1172 (1972), holding that sta

tistical evidence of gross inequalities in the delivery of public services

to black and white residents is sufficient to establish a prima facie case

of unlawful racial discrimination.

3Va. Code §33.1-67 (1950) provides that: “The secondary system of

State highways shall consist of all of the public roads . . . in the sev

eral counties of the State not included in the State [Primary] Highway

System.”

4 Va. Code §33.1-69 (1950) provides that: “The control, supervision,

management and jurisdiction over the secondary system of State high

ways shall be vested in the Department of Highways and the mainte

nance and improvement . . . of such secondary system of State high

ways shall be by the State under the supervision of the State Highway

Commissioner.”

5a

way System.” If these efforts proved unsuccessful, County

nonetheless recognized a “continuing responsibility to main

tain these streets in a fair and equitable manner.”

After securing these agreements, plaintiffs moved for dis

missal of their claims against State and County. The mo

tion was granted and three dismissal orders, each naming

different defendants, were entered on June 1, 1972. The

orders each recited that on plaintiffs’ motion, and with

defendants’ consent, the case was dismissed. While Associa

tions’ later motion alleged that the settlement agreements

were filed in open court (the docket entries do not so re

cite and the clerk’s file does not contain them), the orders

themselves did not mention that the parties had entered

into settlement agreements; and they neither approved nor

incorporated either settlement agreement.

Thereafter, the Commonwealth substantially performed

its obligations under the settlement agreement. County like

wise commenced performance of its obligations and, in the

ensuing three years, upgraded twenty-five roads in black

neighborhoods. In 1975, after certain black residents not

party to the settlement agreement obtained a permanent

injunction preventing County from upgrading one of the

subject roads, County reviewed its obligations and deter

mined that the settlement agreement was, at least in part,

void as contrary to state law. Following this determination,

County’s Board of Supervisors passed a resolution, dated

April 28, 1975, repudiating the settlement agreement.5

5 Briefly, the Board’s conclusion that it lacked authority to continue

performing the settlement agreement was reached by this reasoning:

State law prohibits local government units from expending funds for

the construction, maintenance or improvement of roads not eligible

for inclusion in the secondary system of State highways. Va. Code

§33.1-225 (1950). To be eligible for inclusion in the State system,

there must exist a public right-of-way of not less than thirty feet.

Va. Code §33.1-230 (1950). In addition, by regulation of the High

way and Transportation Commission, a road must also service at

least three houses per mile in order to be eligible for inclusion in

6a

On August 5, 1975, plaintiffs moved the district court

to vacate the dismissal order of June 1, 1972. Plaintiffs

did not pray reinstatement of their law suit and an oppor

tunity to try it. Rather, they prayed enforcement of the

settlement agreements and, if state law prohibited County’s

performance, a declaration of the invalidity of the various

statutes, regulations and administrative rulings pertaining

to the Virginia State Highway System which purportedly

prohibited such performance. On January 30, 1976, under

authority of Rule 60(b) (6), F.R. Civ. P., the district

court vacated its previous order of dismissal; and, on No

vember 26, 1976, it entered an order directing County to

upgrade the forty-three roads still in controversy.6

II.

Neither in the proceedings in the district court nor in

its initial brief filed with this court, did County challenge

the jurisdiction of the district court to resolve what had

become essentially a contract dispute between the parties.

Because it appeared to us that, at the time enforcement

the State system. County believes that nineteen of the forty-three

roads still in controversy are permanently ineligible for inclusion

either because a thirty-foot public right-of-way is unavailable or be

cause the minimum service requirement is unmet. As to these nine

teen, County believes that §33.1-225 absolutely forbids the expendi

ture of county revenues for paving and other improvements. As to

the remaining twenty-four, County believes that, while these are not

permanently ineligible, they are presently ineligible in that the requi

site public right-of-way has not been obtained. Moreover, says the

County, there exists substantial resistance in the affected black neigh

borhoods to the acquisition by County of the necessary rights-of-way.

6 The district court rejected County’s contentions as set forth in

footnote 5, supra, holding in essence that County’s past disregard

for the statutory prohibition of Va. Code §33.1-225 (1950) estopped

it from denying its liability under the settlement agreement to main

tain and improve roads not eligible for inclusion in the secondary

system of State highways. Because we decide this case on jurisdic

tional principles, we express no view as to the merits of County’s

defense to repudiation or the district court’s rejection of that defense.

7a

was sought by Association, it was possible that federal

subject-matter jurisdiction was lacking, we requested that

the jurisdictional issue be briefed and argued. Upon con

sideration of the various arguments advanced and author

ities cited, we conclude that this issue is indeed dispositive

and that the district court lacked jurisdiction to enter an

enforcement order.

III.

As the sole authority supporting the district court’s exer

cise of federal jurisdiction to enforce the settlement agree

ment, Association cites Aro Corp. v. Allied Witan Co.,

531 F.2d 1368 (6 Cir.), cert, denied, 429 U.S. 862 (1976),

a case arising on facts virtually indistinguishable from those

in the case at bar.

In the Aro case, Aro Corporation had originally filed an

action for patent infringement against Allied Witan Com

pany (Allied) under 28 U.S.C. §1338. Prior to trial, Aro

and Allied settled their dispute by means of a licensing

agreement, and by stipulation of the parties, the complaint

was dismissed. Six weeks later, Allied breached the agree

ment by refusing to tender the initial royalty payment. Aro

thereupon filed a motion under Rule 60(b) (6), F. R. Civ.

P., praying both that the district court vacate its prior dis

missal order and that Allied be compelled to perform its

obligations under the licensing agreement. Defendant chal

lenged the district court’s jurisdiction to grant the relief

sought; but the district court ruled that it had the requi

site subject-matter jurisdiction, 65 F.R.D. 513 (N.D. Ohio

1975), and the Sixth Circuit affirmed, holding first that

defendant’s repudiation of the settlement agreement con

stituted “full justification” under Rule 60(b) (6) for re

opening the proceedings; and second, that the district court

was empowered to enforce the settlement agreement not-

thstanding the lack of diversity of citizenship between

parties. 531 F.2d at 1371.

8a

We are in agreement with the Sixth Circuit that, upon

repudiation of a settlement agreement which had termi

nated litigation pending before it, a district court has then

authority under Rule 60(b) (6) to vacate its prior dismis

sal order and restore the case to its docket. See also Chief

Freight Lines Co. v. Local Union No. 886, 514 F.2d 572

(10 Cir. 1975); Kelly v. Greer, 334 F.2d 434 (3 Cir. 1964)

We respectfully differ, however, with the Aro Court in its

conclusion that, once the proceedings are reopened, the

district court is necessarily empowered to enforce the set

tlement agreement against the breaching party. We are of

the opinion that the district court is not so empowered

unless the agreement had been approved and incorporated

into an order of the court, or, at the time the court is re

quested to enforce the agreement, there exists some inde-Q

pendent ground upon which to base federal jurisdiction.

A district court is a court of limited jurisdiction “ [a]nd

the fair presumption is (not as with regard to a court of

general jurisdiction, that a cause is within its jurisdiction

unless the contrary appears, but rather) that a cause is

without its jurisdiction till the contrary appears,” Turner

v. President, Directors and Company of the Bank of North

America, 4 Dali. 8, 10, 1 L. Ed. 718, 719 (1799). The

burden of establishing jurisdiction is on the party claiming 7 8

7 Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b) provides, in pertinent part, that: “On mo

tion and upon such terms as are just, the court may relieve a party

or his legal representative from a final judgment, order, or proceed

ing for the following reasons: . . . (6) any other reason justifying

relief from the operation of the judgment.”

8 Where the settlement agreement is approved and incorporated into

an order of court, the district court possesses jurisdiction to enforce

its own order. Where there has been no incorporation, it is likely

that the “independent ground” most often asserted will be that of

diversity of citizenship between the parties to the settlement agree

ment. 28 U.S.C. §1332. This is not to suggest, however, that other

bases of federal jurisdiction may not also be available in appropri

ate situations, e.g., 28 U.S.C. §§1345, 1346 (United States as party).

9a

it. McNutt v. General Motors Accept. Corp. 298 U.S. 178,

182-83 (1936). After canvassing the possible sources of

jurisdiction in the instant case, we do think that Associa

tion has not met its burden.

Association’s contract claim did not arise “under the

Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States,” 28

U.S.C. §1331. The settlement agreement between Associa

tion and County, while serving to terminate litigation of a

federal claim, was a private contract entered into after pri

vate negotiations between the parties. Both its validity and

the interpretation of its terms are governed by Virginia

law. If, instead of filing a motion under Rule 60(b) (6),

Association had filed a new complaint in the district court,

alleging breach of contract and seeking specific performance,

there is little doubt that the claim would have been dis

missed on jurisdictional grounds.9 10 See Arvin Industries,

Inc. v. Bems Air King Corp., 510 F.2d 1070 (7 Cir. 1975).

The same is true if the parties had negotiated and entered

into a settlement agreement prior to any litigation, and

thereafter Association, alleging the breach of the agreement,

sought to invoke federal jurisdiction to enforce it. See Kysor

Industrial Corporation v. Pet, Incorporated, 459 F.2d 1010

(6 Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 980 (1972).

9 It is true that, in its motion seeking specific performance of the set

tlement agreement, Association asked the district court to declare un

constitutional any state law prohibiting County’s performance. While

this presents a potential federal question, it is well established that

§1331 jurisdiction obtains only if federal law “creates the cause of

action.” American Well Works Co. v. Layne § Bowler Co., 241 U.S.

257 (1916). See also Louisville & Nashville R.R. v. Motley, 211 U.S.

149 (1908). At the time enforcement was sought, Association’s “cause

of action” was for breach of contract — a claim arising under state

law.

10 Since both parties to this litigation are citizens of Virginia, no juris

diction would obtain under 28 U.S.C. §1332, nor does there exist any

special statutory grant of jurisdiction empowering the district court in

the instant case to take cognizance over the contract dispute.

10a

Thus, since there is neither federal question nor diversity

jurisdiction in the instant case, we must look elsewhere if

the jurisdiction of the district court is to be sustained.11

In Aro, the Sixth Circuit advanced what appeared to be

alternative jurisdictional theories and we turn to them.

First, it was said that “courts retain inherent power to

enforce agreements entered into in settlement of litigation

pending before them.” 531 F.2d at 1371. See also United

States v. Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co.,

— F.2d— , — (4 Cir. 1978) (dictum); Meetings & Expo

sitions, Inc. v. Tandy Corp., 490 F.2d 714, 717 (2 Cir.

1974); Kukla v. National Distillers Products Co., 483 F.

2d 619, 621 (6 Cir. 1973); Massachusetts Casualty Insur

ance Co. v. Forman, 469 F.2d 259, 260 (5 Cir. 1972);

Autera v. Robinson, 419 F.2d 1197, 1200 (D.C. Cir. 1969);

Kelly v. Greer, 365 F.2d 669, 671 (3 Cir. 1966), cert, de

nied, 385 U.S. 1035 (1967); Cummins Diesel Michigan, Inc.

v. The Falcon, 305 F.2d 721, 723 (7 Cir. 1962).

While this principle is sound under appropriate circum

stances, it is not a principle of federal jurisdiction. An

analysis of the cases cited by the Aro court in support of

the principle shows that, except for one, they all concerned

settlement agreements which were intended to be incorpo

rated into final orders 12 or for which independent federal

11 Certainly Rule 60 supplies no grant of jurisdictional authority.

It merely permits a district court to try the original cause of action

when the district court concludes that the ends of justice warrant

reinstating the original claim.

12 Kukla v. National Distillers Products, supra; Cia Anon Venezolana

de Navegacion v. Harris, 374 F.2d 33 (5 Cir. 1967); All States In

vestors, Inc. v. Bankers Bond Co., 343 F.2d 618 (6 Cir. 1967).

In each of these cases, parties to litigation pending in district

court had entered into an agreement prior to final judgment where

by defendant consented to a judgment in favor of plaintiff; but

prior to entry of judgment, defendant had repudiated. Rather than

11a

jurisdiction existed. The single exception was a state case

which involved a court of general, not limited, jurisdiction.* 14

likewise, in Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co.,

a recent decision of this court where the principle was re

peated with approval, the jurisdiction of the district court

was not at issue.15

In our view, the inherent power of a district court to en

force settlement agreements, like any other power inherent

ly vested in a federal court, presupposes the existence of

federal jurisdiction over the case or controversy.

13

remitting plaintiff to proof of his entire case, the district court

entered judgment in accordance with the terms of the repudiated

agreement. The settlement agreement was thus viewed as a stipula

tion on the merits of the original claim whereby defendant admitted

liability. See also Cummins Diesel Michigan, Inc. v. The Falcon,

supra.

1 3 Meetings and Expositions, Inc. v. Tandy, supra. See also Massa

chusetts Casualty Ins. Co. v. Forman, supra; Autera v. Robinson,

supra; Skyline Sash, Inc. v. Fidelity and Casualty Co., 378 F.2d

369 (3 Cir. 1967), aff’g, 267 F.S. 577 (W.D. Pa. 1966); Kelly v.

Greer, supra.

14 Melnick v. Binenstock, 318 Pa. 533, 179 A. 77, 78 (1935) (“A

compromise or settlement of litigation is always referable to the ac

tion or proceeding in the court where the compromise was effected;

it is through that court the carrying out of the agreement should

thereafter be controlled.”)

The principle of a court’s inherent power to enforce settlement

agreements appears to have had its origins in state-court decisions.

However, since state courts, unlike federal courts, are courts of gen

eral jurisdiction, state courts generally need not concern themselves

with the source of their jurisdictional authority over a dispute.

Therefore, a statement such as found in Melnick should not be con

strued as a jurisdictional statement; nor should it be relied upon, as

it was in Aro, in resolving an issue of Federal jurisdiction.

15 Because in Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co. the

United States was a party to the settlement agreement, subject-mat

ter jurisdiction clearly existed on independent grounds.

12a

As a second alternative ground for upholding federal juris

diction, both the district court and the court of appeals in

Aro invoked a concept of derivative jurisdiction. Because

the settlement agreement resolved the dispute giving rise to

the original litigation over which the district court had juris

diction, any dispute involving the agreement itself was like

wise properly before the court. As stated by the district

court: “ [J] urisdiction rests on the same footing as when the

case began. . . .” 65 F.R.D. at 514. The court of appeals

developed the point as set forth in the margin.16

It is, of course, well established that, under appropriate

circumstances, a federal court may exercise derivative juris

diction over a dispute despite the absence of an independ

ent basis for federal jurisdiction. The doctrines of both

pendent and ancillary jurisdiction fall within this category.

See, e.g., Moor v. County of Alameda, 411 U.S. 693,

714-15 (1973) (dictum); United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383

U.S. 751 (1966); Dery v. Wyer, 265 F.2d 804 (2 Cir. 1959).

We think, however, that derivative jurisdiction should be

grounded on something more substantial than a mere show

ing that the settlement agreement would not have been en

tered into but for the existence of litigation pending in

federal court.

Consideration of the rationale of Gibbs and Dery supports

this conclusion. In each, derivative jurisdiction was upheld

only because the claim for which no independent jurisdic

tion existed derived from the same nucleus of operative facts

16 As stated in 531 F.2d at 1371:

The Agreement in question is not merely a patent license. It is

also the contractual vehicle by means of which the parties reached

agreement settling their litigation. Both types of agreements are con

tracts; but a settlement agreement is more than a patent license. . . .

To permit the absence of diversity to divest the court of jurisdiction

after settlement, when it could not have done so prior to settlement,

would be to exalt form over substance and to render settlement in such

cases a trap for the unwary. The license cannot be separated from the

purpose of its birth.

13a

as the claim for which there did exist independent jurisdic

tional grounds. For reasons of economy, reasoned the courts,

it makes little sense to remit one of two related claims to

state court since the same facts will form the basis of de-

1 7cision in both.

That consideration is absent here. Association’s contract

claim is factually and legally distinct from the claim giving

rise to the original litigation. To remit Association to state

court in order to have its agreement with County enforced

will not create duplicating litigation since the operative facts

bearing on the validity of the agreement bear no relation to

those underlying Association’s §1983 claim.

While not relying on the sort of economy interest upon

which the doctrines of pendent and ancillary jurisdiction are

based, Aro nonetheless suggests that to divest a district court

of jurisdiction to enforce a settlement agreement in cases

such as this will “render settlement . . . a trap for the unwary.”

531 F.2d at 1371. We think that this is not so. As in the

instant case where federal jurisdiction to sue for a breach of

a settlement agreement does not otherwise exist, a plaintiff

who claims a breach of his settlement agreement has avail

able two courses of action. Fie may take his contract claim

to state court where he may seek enforcement of the settle

ment agreement. Because enforceability is likely to turn on

questions of state law, the state court is an appropriate forum

for resolving this dispute. Alternatively, the injured plain-

57 A recent note suggests that even this rationale is overly expansive

when due weight is given to the fact that federal courts are courts of

limited jurisdiction. The note argues that consistent with Article III

of the Constitution pendent jurisdiction should be recognized only

when the rights created by state and federal law are substantially iden

tical, irrespective of the factual predicate giving rise to the assertion

of those rights. Note, The Concept of Law-Tied Pendent Jurisdiction:

Gibbs and Aldinger Reconsidered, 87 Yale L. J. 627 (1978).

18 In the instant case, the state forum is particularly appropriate be

cause of the complexity of the state law questions involved. See foot

note 5, supra; Note, Virginia Subdivision Law: An Unreasonable Bur-

14a

tiff may file a Rule 60(b) (6) motion in federal court, re

questing that the prior dismissal order be vacated and the

case restored to the court’s trial docket. This restores the

litigants to the status quo ante and allows the plaintiff to

prove his case and obtain his relief on the merits of the

underlying claim.

IV.

To summarize: We find no independent basis for assert

ing jurisdiction over the contract dispute, and we see no

considerations of either judicial economy or fairness requir

ing the settlement agreement to be enforced in federal court.

We therefore conclude that the district court lacked jurisdic

tion to enforce the agreement. We reverse the order of the

district court compelling County to perform its remaining

obligations under its agreement with Association. We do not

disturb the portion of the district court’s order which struck

its order of dismissal. Association may proceed to the trial

of its original claim if it be so advised.

REVERSED AND REMANDED

den on the Unwary, 34 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 1223 (1977). While we

do not question the competence of the district court to resolve these

questions, it is nonetheless preferable, when a decision requires inter

pretation of statutes establishing a state administrative or regulatory

regime, that such interpretation be authoritatively made in the state-

court system. Cf. Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman Co., 312

U.S. 496, 498-500 (1941).

15a

JUDGMENT

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-1190

APPEAL FROM the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia.

THIS CAUSE came on to be heard on the record from

the United States District Court for the Eastern District

of Virginia, and was argued by Counsel.

ON CONSIDERATION WHEREOF, It is now here order

ed and adjudged by this Court that the judgment of the

said District Court appealed from, in this cause, be, and

the same is hereby, reversed. This case is remanded to the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia, at Alexandria, consistent with the opinion of this

Court filed herewith.

APPENDIX B

[Filed March 6, 1978]

/s/William K. Slate II

CLERK

16a

JUDGMENT

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-1248

APPEAL FROM the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia.

THIS CAUSE came on to be heard on the record from

the United States District Court for the Eastern District

of Virginia, and was argued by counsel.

ON CONSIDERATION WHEREOF, It is now here order

ed and adjudged by this Court that the judgment of the

said District Court appealed from, in this cause, be, and

the same is hereby, reversed. The case is remanded to the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia, at Alexandria, consistent with the opinion of this

Court filed herewith.

/s/William K. Slate II

CLERK

[Filed March 6, 1978]

17a

[Filed 4/28/78]

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Appeals from the United States District Court for the East

ern District of Virginia, at Alexandria. Oren R. Lewis, Dis

trict Judge.

Upon consideration of the appellee/cross-appellants peti

tion for rehearing and suggestion for rehearing en banc,

and no judge having requested a poll on the suggestion for

rehearing en banc.

IT IS ADJUDGED and ORDERED that the petition for

rehearing is denied.

Entered at the direction of Judge Winter for a panel con

sisting of Judge Winter, Judge Russell and Judge Widener.

FOR THE COURT,

APPENDIX C

/s/William K. Slate, II

CLERK

18a

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

Alexandria Division

FAIRFAX COUNTYWIDE CITIZENS :

ASSOCIATION, et al.,

Plaintiffs

v.

COUNTY OF FAIRFAX, VIRGINIA

et al.,

Defendants

MEMORANDUM OPINION

APPENDIX D

Civil Action No.

71-336-A

This suit was originally brought in this court in 1971 as

a civil rights action for declaratory judgment and injunctive

relief — The plaintiffs alleged discrimination in the provi

sion of public services for the black residents of Fairfax

County and the Town of Herndon.

Considerable pretrial discovery took place and both par

ties were prepared for trial scheduled for June 1, 1972.

In the interim the parties had been attempting to com

promise and settle their differences.

They reached agreement on May 31, 1972 and entered

into separate settlement agreements with the County Board

of Supervisors, the Town of Herndon and the defendant

Fugate.

On June 1, 1972, the day following execution of the

settlement agreements, the plaintiffs moved to dismiss their

claims against the County of Fairfax, the Town of Herdon

19a

and the defendant Fugate on the ground that the matter

in controversy had been compromised and settled — The

case was then dismissed.

All of the defendants proceeded with the work provided

for in the said settlement agreements.

The plaintiffs admit that the Town of Herndon has done

what it agreed to do and that the defendant Fugate has up

graded the streets in the Virginia secondary highway system

as provided for in the June 1st agreements — They further

admit that the County of Fairfax has done considerable

work under its agreement — It has upgraded over 25 roads,

and has been successful in having the State include several

of the upgraded streets into the secondary road system.

The County now says it will not complete the upgrading

of the remaining roads as provided for in the settlement

agreement — The Fairfax County Board of Supervisors

adopted a resolution on April 28, 1975 so stating.

The plaintiffs immediately thereafter moved the Court

to vacate the June 1, 1972 dismissal order and to reinstate

the suit, and to compel the County of Fairfax to upgrade

the roads as called for in its settlement agreement.

The motion to reopen was heard shortly thereafter, and

both parties advised the Court they wanted time to further

negotiate in the hopes that they might settle their differ

ences to the satisfaction of the citizens living in the so-

called black communities, many of whom were not then

knowledgeable of the contents of the settlement agreements

and many of whom purportedly did not want the thorough

fares in front of their residences made into public streets.

Although some further compromises and settlements were

reached as to some of the streets, much remained to be done

when the motion to reopen was again heard by the Court on

June 21, 1976.

20a

The County now contends that the original settlement

agreement was illegal because it could not upgrade or im

prove streets in the County that did not meet the minimum

requirements for inclusion in the state secondary highway

system — it also claims mutual mistake and misrepresenta

tion of material facts.

The County now wants to modify the settlement agree

ment to allow all residents along the P.6 roads in question

which meet the state requirements for service, who wish

their road to become public, to dedicate the necessary

thirty feet of right-of-way. The County then would upgrade

those roads so they could be accepted into the state second

ary system.

The plaintiffs want the settlement agreement performed

as written.

The pertinent portions of the settlement agreement pro

vide that —

(1) The County agrees to upgrade the P.6 streets

(attached hereto) — At a minimum, the P.6

streets shall be paved. Consistent with the above

and the reasonable desires of the existing resi

dents, the P.6 streets will be brought as closely

as possible to existing surrounding area stand

ards.

(2) The County will make every effort to have the

P.6 streets, when improved, taken into the state

secondary highway system — If unsuccessful,

the County recognizes their continuing respon

sibility to maintain these streets in a fair and

equitable manner.

(3) The plaintiffs will use their best good faith ef

forts to assist the County with any land acqui

sition problems.

21a

The record here made discloses that the County has spent

more than a half million dollars and has been working on the

roads in question for more than three years.

Seven of the P.6 roads have been accepted into the state

highway system — Sixteen are being readied for acceptance

by the State.

The plaintiffs have agreed to drop six of the P.6 roads be

cause they serve no public purpose — They also have agreed

to drop Ransell Road because of severe resident opposition.

Of the remaining 45 P.6 roads, 36 are private, 7 are partly

private and partly dedicated, and 2 are completely dedicated

— Of the 36 private roads, 2 are partially outside of the juris

dictional limits of Fairfax County.

The county survey made long after the settlement agree

ment discloses that many of the private roads are ineligible

for acceptance into the state system due to insufficient

service — and on those which completely or partially meet

the state requirements for service, at least one resident indi

cated he would not be willing to grant the County a 15-foot

right-of-way from the centerline of the existing travelway in

return for public maintenance.

The County’s belated claim that it is illegal for the County

to spend money to upgrade and maintain P.6 roads that do

not qualify for acceptance into the state system is without

merit.

The record shows that the County has, both before and

after the date of the settlement agreement, upgraded and

paved many of the P.6 roads which were not then or are not

now eligible for inclusion in the state road system under the

existing statutory requirements - and has continued to main

tain many of them.

Fairfax had many roads that did not meet the state re

quirements for inclusion in the state secondary road sys-

22a

tern prior to the adoption of the so-called Byrd Road Sys

tem.

Practically all of these old roads, with the exception of

the P.6 roads in question, have been acquired and upgraded

by the County and are now a part of the state secondary

road system.

The County gives no reason for its failure to acquire these

P.6 roads and to upgrade them so they might become eligible

for inclusion in the state system.

After this suit was filed charging the County with discrimi

nation in furnishing public services for the black residents of

the County (these P.6 roads are all within Fairfax County’s

so-called black communities), the County Board agreed to

upgrade these P.6 streets — at a miminum by paving — and

to make every effort, when improved, to have them taken

into the state secondary system.

If unsuccessful, the County Board agreed to maintain

them in a fair and equitable manner.

They now say, in support of their charge of mutual mis

take and/or misrepresentation, that they did not know when

they signed the agreement that many of these P.6 streets

had not been dedicated to public use by prescription or

otherwise.

If they did not know who owned the requisite right-of-

way, all they had to do was to search their own land records.

All of the P.6 streets were in use and open and obvious to

the county officials for many years.

There is no evidence of any misrepresentation on the part

of the plaintiffs — To the contrary, paragraph three of the

settlement agreement provides that the plaintiffs will use

their best good faith efforts to assist the County with any

land acquisition problems.

23a

The County now wants the Court to modify the agree

ment to require the adjacent landowners to dedicate the

necessary rights-of-way as a condition precedent to its up

grading and paving the P.6 streets.

Courts do not modify agreements — They determine only

whether they are valid and enforceable.

The agreement in question is clear and unequivocal — Per

formance is neither illegal nor impossible.

At a minimum the P.6 streets shall be paved and brought

as closely as possible to existing surrounding area standards.

If the County is unsuccessful in having them taken into

the state system, it should maintain them in a fair and equi

table manner.

The County can acquire the necessary rights-of-way, if

needed for paving and maintenance, by gift, purchase, pre

scription or condemnation, and upgrade the streets suffi

cient for inclusion into the secondary road system, thereby

relieving the County from future maintenance.

This suit was dismissed by the plaintiffs in good faith -

The County has not lived up to its part of the bargain.

Therefore the June 1, 1972 order of dismissal will be

vacated, the suit reinstated, and an order will be entered

requiring the Board of Supervisors of Fairfax County to

perform its part of the May 31, 1972 settlement agree

ment within a reasonable period of time.

Counsel for the plaintiffs will prepare an appropriate

order pursuant to the foregoing, submit the same to coun

sel for the defendant for approval as to form, and then to

the Court for entry.

The Clerk will send a copy of this memorandum opinion

to all counsel of record.

/s/Oren R. Lewis

September 27, 1976 United States Senior Judge