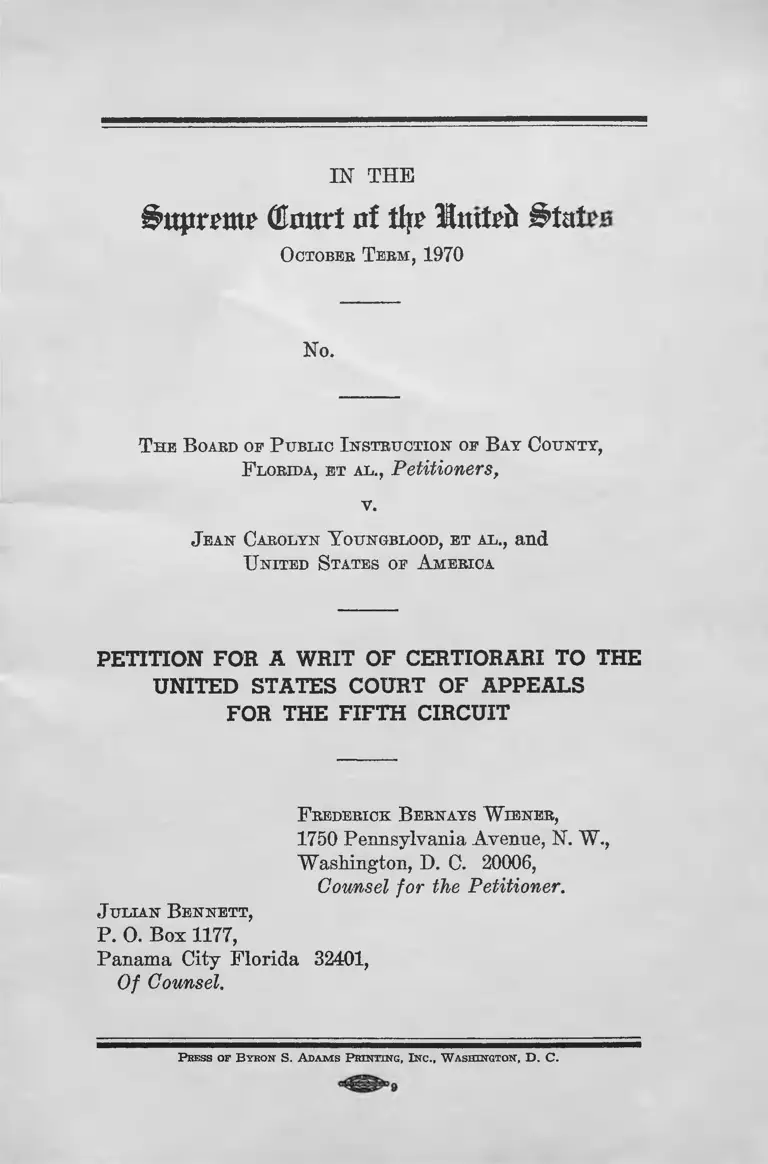

Board of Public Instruction of Bay County, Florida v. Youngblood Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Public Instruction of Bay County, Florida v. Youngblood Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1970. 46cc2600-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8cd82805-19da-4675-b0cc-790fc0af8073/board-of-public-instruction-of-bay-county-florida-v-youngblood-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed March 01, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

#>itpnw GJmtrt rtf tip? In tt^ Btut

October Teem , 1970

No.

T h e B oard of P ublic I nstruction of B at County,

F lorida, et al., Petitioners,

v.

J ean Carolyn Y oungblood, et al., and

U nited S tates of A merica

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

F rederick B ernays W iener ,

1750 Pennsylvania Avenue, N. W.,

Washington, D. C. 20006,

Counsel for the Petitioner.

J ulian Bennett ,

P. O. Box 1177,

Panama City Florida 32401,

Of Counsel.

P ress of B yron S. Adams P rinting, Inc., W ashington, D . C.

INDEX

Page

Opinions below ............................................................. 2

Jurisdiction ......................................... 2

Questions presented.............................. 2

Constitutional provisions and statutes involved......... 3

Statement ...................................................................... 4

A. Factual background............................................. 4

B. Earlier proceedings ............................................. 5

C. Present appeal and decision below....................... 6

D. Consequences of new plan directed by district

court pursuant to decision below..................... 7

Reasons for granting the w r i t ...................................... 9

Conclusion ........... 15

Appendix A—Opinion below........................................ A1

Appendix B—Order denying rehearing.........................A12

Appendix C—New plan directed by district court pur

suant to decision below...........................................A13

1. District Court’s o rder..................................... A13

2. District Court’s plan ......................................A15

Appendix D—Legislative history of the anti-busing

provisos of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ................ A21

11 Index Continued

AUTHORITIES

Cases : Page

Alexander v. Board of Education) 396 U.S. 1 9 ......... 10

Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F.2d 209, 1

certiorari denied, 377 U.S. 924 .............................. A26

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 6 0 ............................. 14

Carter v. West Feliciana School Bd., 396 U.S. 226 . . . 6

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 .................................. 13

Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 U.S. 323 ............................. 14

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S'. 430 ............. 5

McDaniel v. Barresi, No. 420, this Term .................... 11

McGhee v. Spies, 334 U.S. 1 ...................................... 14

Pinellas County, Florida v. Bradley, No. 632, this

Term .................................................................9,12,14

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 ....... .................. 14

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

Dist., 419 F.2d 1211................................................ 2, 5

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 ........ 13

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion, 372 F.2d 836, on rehearing in banc, 380 F.2d

385, certiorari denied sub nom. Caddo Parish

School Board v. United States, 389 U.S. 840 ....... 13,14

Constitution oe the U nited States :

Fourteenth Amendment............................................. 12

Section 1 ................................................................. 3

Equal Protection Clause.............................. 3,13,14

Section 5 ................................................................ 2, 3

S tatutes :

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. 88-352, 78 Stat.

241 ....................................................... 11,12, A21, A27

Sec. 401(b) .............................................2,3,11, A23,

A24, A25, A27

Sec. 407(a)....................................................3,11,13,

A24, A25, A27

See. 410 ............................................................... 4

42 U.SjC. § 2000c(b) ................................................. 3

42 U.S.C. § 2000c-6(a) .............................................. 3

42 U.S.C. § 2000c-9.................................................... 4

Index Continued iii

Miscellaneous : Page

110 Cong. Bee.:

p. 1518....................................................................A23

p. 1598 ............................... ...................................A 24

p, 2280 ....................................................................A24

p. 2805 ....................................................................A24

p. 3719....................................................................A24

pp. 5858-62 ...............................................................A25

p. 6417....................................................................A24

p. 6820 ....................................................................A25

pp. 6839-41 ...............................................................A25

pp. 8357-58 ...............................................................A25

pp. 8615-16 .............................................................. A25

p. 8621 ....................................................................A25

p. 11926 .................................................................. A24

p. 11929 .................................................................. A24

pp. 12436-37 .............................................................A25

pp. 12438-41 .............................................................A25

pp. 12706 et seq..........................................................A25

p. 12714.................................................................. A25

pp. 12715, 12717 ................ A26

p. 12717.................................................................. A26

pp. 12817 et seq..........................................................A27

p. 13310.................................................................. A27

p. 13312............ ................................................... A27

pp. 13819-22 .............................................................A27

p. 14239 ............................................... A27

p. 14511.................................................................. A27

pp. 14631, 15869 ......................... A27

IV Index Continued

Page

A21, A22. A24, A27H, R. 7152, 88th Cong., 1st sess...

H. R. Doc. 124, 88th Cong., 1st sess.:

p. 6 ........................................................................ A21

p, 7 .................................................. A21

H. R. Rep. 914, 88th Cong., 1st sess............................. A22

p. 5 ........................................................................ A23

p. 7 ...... A24

p. 8 4 ............. A23

Id., Part 2, pp. 21-22.............................................A23

Sen. 1731, 88th Cong., 1st sess............................. A21, A22

IN THE

iatprem e Gkmrt o f % lo tte d States

October Teem , 1970

No.

T h e B oard of P ublic I nstruction of B ay County,

F lorida, et al., Petitioners,

v.

J ean Carolyn Y oungblood, et al., and

U nited S tates of A merica

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

T he B oard of P ublic I nstruction of B ay County,

F lorida, and others, your petitioners, pray that a writ

of certiorari issue to review the judgment of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, entered

in the above-entitled case on July 24, 1970.

2

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the court below on the first appeal is

reported sub nom. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Sep

arate School Dist. at 419 F.2d 1211. The opinion of the

court below on the present appeal and the dissenting

opinion on such appeal (Appendix A, infra, pp. Al-All)

have not yet been reported.

JURISDICTION

The opinion of the court below was entered on July 24,

1970 (Appendix A, infra, p. Al). Under the present prac

tice of that court in school board cases, the opinion in

such cases is issued as and for the mandate. A timely

petition for rehearing was denied on September 11, 1970

(Appendix B, infra, p. A12).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the Constitution requires school boards to

achieve racial balance in each school in their districts

in an otherwise unexceptionable unitary school system,

especially where such racial balancing can only be ob

tained by busing nearly two thousand kindergarten through

sixth grade schoolchildren away from their neighborhoods

for long periods on every school day, and excludes them

from their neighborhood walk-in schools because of their

race or color.

2. Whether the court below, which decreed substantial

dislocations in order to achieve racial balance in each

school in the school district, improperly disregarded the

explicit direction of Congress, implementing the XIV

Amendment under Section 5 thereof in Section 401(b) of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, that “ ‘desegregation’ shall

not mean the assignment of students to public schools in

order to overcome racial imbalance.”

3. Whether the court below, which decreed substantial

dislocations in order to achieve racial balance in each

3

school in the school district, improperly disregarded the

explicit direction of Congress, implementing the XIV

Amendment under Section 5 thereof in Section 407(a)(2)

of the Civil Eights of 1964, that “ nothing herein shall

empower any * * * court of the United States to issue

any order seeking to achieve a racial balance in any school

by requiring the transportation of pupils or students from

one school to another in order to achieve such racial

balance. ’ ’

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS AND STATUTES

INVOLVED

1. Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment provides, in

pertinent part—-

“ nor shall any State deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor

deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal

protection of the laws.”

2. Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment provides:

“ The Congress shall have power to enforce, by ap

propriate legislation, the provisions of this article.”

3. Section 401(b) of the Civil Eights Act of 1964 (42

U.S.C. § 2000e(b)), provides:

“ As used in this title—* * *

“ (b) ‘Desegregation’ means the assignment of

students to public schools and within such schools

without regard to their race, color, religion, or na

tional origin, but ‘desegregation’ shall not mean the

assignment of students to public schools in order to

overcome racial imbalance.”

4. Section 407(a) of the Civil Eights Act of 1964 (42

U.S.C. 2000c-6(a)) provides in pertinent part:

“ Whenever the Attorney General receives a com

plaint in writing * # * to the effect that * * * minor

children, as members of a class of persons similarly

4

situated, are being deprived by a school board of

the equal protection of the laws * * * the Attorney

General is authorized * * * to institute for or in

the name of the United States a civil action * * *

for such relief as may be appropriate * * * pro

vided that nothing herein shall empower any official

or court of the United States to issue any order

seeking to achieve a racial balance in any school by

requiring the transportation of pupils or students

from one school to another or one school district to

another in order to achieve such racial balance, or

otherwise enlarge the existing power of the court

to insure compliance with constitutional standards.”

5. Section 410 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42

U.S.C. §2000c-9) provides:

“ Nothing in this title shall prohibit classification

and assignment for reasons other than race, color,

religion, or national origin.”

STATEMENT

This is another school desegregation case in which racial

balancing has been judicially decreed. The issue now

presented is a narrow one, enabling the facts essential

to its resolution to be presented in brief compass.

A. Factual Background

Bay County is located in northwest Florida, in that

State’s panhandle. The county has a total population

of some 70,000, of which 17,000 odd are school children;

of the latter 18% or about 3,000 are black. Petitioner

Board of Public Instruction is currently operating two

senior high schools, four junior high schools, and 19 ele

mentary schools.

The bulk of the black population of Bay County is

concentrated in an area in Panama City two miles square,

where originally Rosenwald Junior High and Oscar Pat

terson and A. D. Harris elementary schools were built

to serve black students.

B. Earlier Proceedings

The present action was filed in 1963, resulting in an

order in July 1964 for a “ grade-a-year transfer plan.”

This plan was thereafter voluntarily accelerated by the

Board through desegregation by six grades. The United

States intervened in the litigation in 1966, and in April

1967 the district court directed entry of a freedom of

choice plan.

In that year all the black senior high school students

were integrated into the two formerly white senior high

schools. Then, following this Court’s decision in Green

v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430, further desegrega

tion was effected, with the result that, by the school year

1968-69, 39 per cent of the black students were enrolled

in formerly white schools, although hardly any white

students had transferred or been transferred to formerly

black schools.

In April 1969, the district court entered orders ap

proving the Board’s plan for further desegregation, but

this was deemed inadequate by respondents and by the

United States, both of whom appealed to the court below.

That tribunal, in a consolidated in banc proceeding in

volving 12 other school cases, said of Bay County (Single-

ton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist., 419 F.2d

1211, 1221-22) :

“ This system is operating on a freedom of choice

plan. The plan has produced impressive results but

they fall short of establishing a unitary school system.

“ We reverse and remand for compliance with the

requirements of Alexander v. Holmes County [396

U.S. 19] and the other provisions and conditions of

this order.”

The foregoing ruling required further faculty desegre

gation by February 1, 1970, but deferred further student

desegregation until September 1, 1970. On December 15,

6

1969, following this Court’s order in another of the con

solidated oases, Carter v. West Feliciana School Bd., 396

U.S. 226, Mr. Justice Black ordered further student de

segregation in Bay County by February 1, 1970, also.

Faculty desegregation is no longer in issue.

C. Present Appeal and Decision Below

Thereafter the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare filed a desegregation plan, to which the Board

objected; the Board filed a plan of its own; and later

the Board filed an amended plan, based on geographic

attendance zones for all schools, including the remaining

black schools; the zone boundaries of the latter had been

drawn by the black principals of those schools without

regard to race. As the Board’s superintendent testified

in district court on the hearing held on those plans (Tr.

141), “ I wanted to stay out of the statistics business, and

in the business of children.”

The results of the three plans appear in tabular form

in the opinion below (Appendix A, infra, p. A4, note 7):

School Cap.

9 /1 9 6 9

E n ro llm en t

H E W P ro j.

E n ro llm en t

B d ’s P ro j.

E n ro llm en t

g /1 9 7 0

E n ro llm en t

W N T W N T W N T W N T

R osenw ald 1000 0 377 377 629 191 820 127 378 505 75 275 350

H a r r is 650 0 595 595 256 82 338 16 593 609 3 472 475

P a tte r so n 680 2 626 628 324 84 408 171 485 656 115 473 508

The district court approved the Board’s amended plan,

but on appeal the court below once more reversed, saying

(Appendix A, infra, pp. A10-A11):

“ We again note that the Bay County School Board

has ‘produced impressive results’ in desegregation.

At the same time, we have concluded that it has not

gone far enough. We reverse and remand this case

for proceedings consistent with this opinion. We

suggest to the district court that it would be helpful

to order that the team from HEW work with school

7

officials to revise the geographic zones proposed by

HEW on the basis of the up to date pupil locator

maps. These proposals should then be filed with the

court and the parties permitted to file any objections

or proposed modifications, after which the district

court should hold a prompt hearing and shall ap

prove a more effective' desegregation plan to be put

into effect in September 1970.

“ In the light of up-dated information and other

pertinent facts, HEW and the Board should explore

the feasibility of retaining the classrooms especially

designed for the Educable Mentally Retarded Unit

at Rosenwald School. Consideration should also be

given to retention of the County-Wide Education Media

Center at Rosenwald or its relocation at another

school.’’

Judge Coleman, while agreeing that the feasibility of

retaining the Educable Mentally Retarded Program at

Rosenwald should be explored, dissented in all other re

spects (Appendix A, infra, p. A l l ) :

“ It seems to me that this decision again allows sta

tistics, in isolation, to outweigh all other considera

tions. I would hold that Bay County in fact does

have a public school system in which no child is

deprived of the right to attend a school on account

of his race or color.

“ I would not further disrupt this school system

solely to attain a more evenly distributed racial bal

ance, which, as I understand it, is not required by

the Constitution if the school system is a unitary

one. ’ ’

D. Consequences of New Plan Directed by District Court

Pursuant to Decision Below

Under the terms of the Fifth Circuit’s opinion, the

“ prompt hearing” that the district court was directed

to hold in order to “ approve a more effective desegrega

tion plan to be put into effect in September 1970” was

held on August 14, 1970. But the only guidance then

8

available to the district court was that contained in the

following paragraph in the majority opinion (Appendix

A, infra, p. A7):

“ The record contains suggested alternatives avail

able to the Board which would totally eradicate all

vestiges of the dual school system and deal with the

problems of the flight of white parents and resegre

gation. This could be accomplished at the junior

high level simply by drawing a zone on the basis of

the full capacity of the school. At the elementary

level, the Negro schools could be paired with white

schools. ’ ’

At such hearing, the district court with one modification

approved a plan prepared two years previously by a De

partment of Justice attorney in this case, which plan

utilized Area Sixth Grade Centers in order to effect

desegregation. The district court rejected both the Board’s

expanded geographic zone plan as well as the HEW pair

ing plan. The district court’s order and the plan that

it approved are set out in Appendix C, infra, pp. A13-

A20.

The substance of the foregoing approved plan is this:

(a) The 453 6th grade children now in six elementary

schools (Cherry Street, Cove, Lucille Moore, Northside,

Oakland Terrace, and St. Andrew) will be bused to the

A. D. Harris school, where, with the 71 6th graders for

merly there, they will constitute a student body that is

73% white and 27% black.

(b) The 423 children formerly in A. D. Harris in grades

from kindergarten to 5th grade will in turn be bused

to the six schools listed in par. (a).

(c) The 467 6th grade children now in five elementary

schools (Callaway, Cedar Grove, Millville, Parker, and

Springfield) will be bused to the Oscar Patterson school,

where, with the 75 6th graders formerly there, they will

9

constitute a student body that is 87% white and 13%

black.

(d) The 508 children formerly in Oscar Patterson in

grades from kindergarten to 5th grade will in turn be

bused to the five schools listed in par. (c).

The elementary schools listed in par. (a) are from

4.5 to 1.7 miles distant from A. I). Harris, those in par.

(b) are between 5.3 to 1.5 miles away from Oscar Pat

terson.

Those school distances necessarily do not measure the

busing involved, inasmuch as many of the pupils originally

attending the outlying schools lived at some distance be

yond them and thus farther away from that part of

Panama City where A. D. Harris and Oscar Patterson are

located.

Consequently the busing required under the approved

plan involves for some children round trips of 18.5, 15.5,

14.1, and 12.5 miles. This requires such children to be

away from their home neighborhoods from 6 :30 or 7 :15

A.M. until between 4 and 5 :30 P.M. on each school day.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

This case presents essentially the same issues as does

Pinellas County, Florida v. Bradley, No. 632, this Term,

now pending on petition for certiorari, but with this vari

ant, that while in the Pinellas County case the Fifth

Circuit decreed massive busing to eliminate nine all-black

or almost all-black schools found to be the result of housing

patterns in St. Petersburg, here the same tribunal has

directed extensive busing over longer distances, requiring

young children to be away from their homes for long

periods every day, in order to eliminate black-majority

schools in the smaller black residential section of Panama

City.

10

Thus in this case the court below has ruled that, even

without any all-black schools, a unitary school system,

ceases to be such if it includes any black-majority schools.

The dispassionate observer may well inquire, What

constitutional, legal, or educational value is being served

by the consequent uprooting of nearly 2000 small children

from their homes, some of them for 10 hours each school

day? He may similarly ask, "What rights are being vindi

cated, what constitutional principles are being effectuated,

by a judicial order whose traumatic effect operates only

on the very young, beginning with kindergarten and

stopping with the 6th grade?

It is petitioners’ view that the order in this case issued

under compulsion of the opinion below is not required

by anything in the Fourteenth Amendment, runs directly

counter to the solemn direction of Congress in its im

plementation of that Amendment, and moreover violates the

direction of this Court (Alexander v. Board of Education,

396 U.S. 19, 20) for “ unitary school systems within which

no person is to be excluded from any school because of

race or color”—for here many hundreds of school children

are being moved long distances from their neighborhood

schools in order to satisfy the Fifth Circuit’s predilec

tions in respect of racial classification and percentages.

First. The public importance of the busing issue is

attested by this Court’s order of August 31 that set for

early argument in October a sextet of school busing cases.

Second. Up to now, however—or at least up to mid-

September, when this petition received its final substan

tial revision—up to then, the materials on file in those

six cases did not fully, or, in our view, adequately, reflect

the impressive legislative history underlying the two anti

busing provisos now in question, a history showing with

peculiar clarity that the concept of racial balancing as a

form of desegregation was explicitly and emphatically

11

disapproved by Congress when it enacted the Civil Rights

Act of 1964.

At the outset, in asking Congress to assert its authority

to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment, the President noted

the educational problems flowing from racial imbalance.

The first bills thereafter introduced contained numerous

provisions dealing with those problems, but the House

Judiciary Committee struck out every one of them. The

anti-racial-balancing clause now in Section 401(b) was

accepted on the House floor by the Chairman of the

Judiciary Committee, in charge of the bill. Following

complaints by Southern senators that the bill as it reached

the Senate would permit transportation of school children

back and forth to achieve racial balance, the anti-racial-

balancing proviso now in Section 407(a) was drafted by

the four bipartisan civil rights leaders who directed the

measure through the Senate. One of those leaders said

that “ if the bill were to compel [the busing of children

to achieve racial balance] it would be a violation, be

cause it would be handling the matter on the basis of

race and would be transporting children because of race.”

An amendment to strike both anti-busing provisos, pro

posed by the leader of the Senate opposition to the

Civil Rights Act as a whole, was defeated 18-71.

In order to avoid unduly lengthening the body of this

petition, we have set forth the essential features of the

foregoing legislative history in Appendix I), infra, pp.

A21-A27. It follows fairly closely what already appears

in the Pinellas County petition in No. 632 at pp. 14-22,

but adds a number of items not included there.

Third. In the Memorandum for the United States as

Amicus Curiae filed in McDaniel v. Barresi, No. 420 of

this Term, it is said at p. 6 (footnote omitted) :

“ 2. Equally unsound is the Georgia Supreme Court’s

notion that the school board’s plan violates Sections

401(b) and 407(a) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Those provisions, applying only to federal courts and

12

officials, do not purport to be prohibitions but are

simply disclaimers of granting new power to federal

authorities to deal with purely adventitious, de facto

segregation. Thus, they have no effect whatever on

the powers of a school board. See, e.g., United

States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, supra,

372 F.2d at 878-886; United States v. School District

151, 286 F. Supp. 786 (N.D. 111.), affirmed, 404 F. 2d

1125 (C.A. 7); Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of

Education, 311 F. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal.); Keyes v.

School District Number One, Denver, Colo., 303 F.

Supp. 289 (D. Col.); Sivann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, No. 14,517 at 20-21 (C.A. 4, May

26, 1970). See, also, 110 Cong. Rec. 1518, 1598, 12714,

13820 (1964).”

The foregoing excerpt places the United States in the

position of directly contradicting the civil rights leaders

who succeeded in placing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 on

the books, and of adopting instead the views of that

measure’s principal opponent, who complained that it was

a sectional bill aimed only at the South. Thus the Gov

ernment reads the statute, not as written, but as though

Senator Russell and his followers had succeeded in strik

ing both anti-busing provisos from the bill, success that

so notably eluded them in the Senate.

Otherwise stated, the Government rejects the interpre

tation of the anti-busing provisos formulated by the spon

sors and supporters of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and

instead adopts the position of the opponents of that

measure.

Moreover, the references to legislative history in the

quoted extract are so very fragmentary as to be com

pletely misleading, as will be seen from the short sum

mary in Point Second above and particularly from the

more extended treatment appearing below in Appendix

D, pp. A21-A27.

Fourth. This case raises the same questions regarding

the effect to be given Congressional formulations of

Fourteenth Amendment requirements as does the Pinellas

13

County petition in No. 632 in its Point Fourth at pp. 22-

23. It therefore seems to us unnecessary to repeat here

the framing of those issues already presented to the

Court.

The Board is fully aware of the final clause of § 407(a),

“ or otherwise enlarge the existing power of the court

to insure compliance with constitutional standards.” The

Board’s position is that nothing in the Constitution re

quires racial balancing any more than anything in that

instrument requires economic balancing or social bal

ancing. Those are concepts that do not flow from the

Equal Protection Clause, they are ideas sought to be

read into that Clause by their egalitarian proponents.

In short, it is the Board’s view that, just as the Equal

Protection Clause does not require racial balancing in

jury selection (Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282, 286-287,

290-291; Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 208-209), so

likewise it does not require racial balancing in school ad

ministration. Indeed, when racial balancing is undertaken

as it has been here, there is being operated a unitary

school system in which almost two thousand children are

effectively excluded from the schools nearest their homes,

simply because their race or color does not otherwise

achieve the optimum racial percentages favored by the

Fifth Circuit.

Fifth. As has been seen, Bay County’s school system

is a unitary one, except, in the view of the court below,

with respect to the schools in the black residential section

of Panama City, whose zone boundaries resulting in black-

majority student bodies were drawn by those schools’

black principals without regard to racial percentages.

The court below in the Jefferson County case (United

States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2d

836, on rehearing in banc, 380 F.2d 385, certiorari denied

sub nom. Caddo Parish School Board v. United States,

389 U.S. 840) drew a distinction between so-called de facto

14

segregation in the North and so-called de jure segregation

in the South. But in situations involving school systems

that are unitary except for the make-up of pupil popu

lations that reflect residential patterns, such as this one

and the Pinellas County case (No. 632, this Term), that

distinction is demonstrably fallacious.

Residential segregation de jure emanating from legis

lative enactment has been recognized as illegal since 1917.

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 TJ.S. 60. Residential segregation

stemming from private agreement in the form of restric

tive covenants was sustained by this Court as recently as

1926 (Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 TJ.S. 323), nor were such

covenants outlawed until 1948. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

TJ.S. 1. Significantly, the companion case in that same

litigation (McGhee v. Spies, No. 87, Oct. T. 1947) arose

in Michigan.

Consequently the segregated housing patterns out of

which this and many other school-busing cases arise had

until twenty years or so ago quite as complete a de jure

basis in the North as in the South, and therefore plainly

can not justify different treatment in different portions

of the country. Indeed, the line of decision in the court

below that began with Jefferson County involves one un

edifying paradox compounded by another equally distaste

ful: First, an unequal sectional application of the Equal

Protection Clause; second, classification of school children

by race in order to end the evils of racial classification.

Sixth. It follows that the decision below runs counter

to a solemn pronouncement made by the Congress in the

exercise of a power specifically conferred by the Consti

tution, does a disservice to the cause of education, and,

by directing that children of tender school age be shipped

back and forth like so many bags of meal, simply to re

flect particular racial percentages, commits a present act

of obvious cruelty in the guise of rectifying an ancient

wrong.

15

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this petition for a writ of

certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted.

F rederick B ernays W iener ,

1750 Pennsylvania Avenue, 1ST. W.,

Washington, D. C. 20006,

Counsel for the Petitioner.

J ulian B ennett ,

P. O. Bos 1177,

Panama City Florida 32401,

Of Counsel.

October 1970.

APPENDIX

A1

APPENDIX A

OPINION BELOW

1ST T H E U N IT E D STA TES COURT OF A PPEA LS

FO R T H E F IF T H C IR C U IT

No. 29369

J ean Carolyn Y oungblood, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

U nited S tates of A merica,

Plaintiff -Intervenor-Appellant,

versus

B oard of P ublic I nstruction of

B ay County, F lorida, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Florida

(July 24, 1970)

Before W isdom, Coleman, and S impson,

Circuit Judges.

W isdom, Circuit Judge: The Board of Public Instruction

of Bay County, Florida, faces fewer desegregation problems

than do most school boards. This Court found, last Decem

ber, that the freedom of choice plan in Bay County “ has

produced impressive results” ,1 although “ it fall[s] short

of establishing a unitary school system”.2 As of February

1 This is one of the en bane school eases decided by this Court on

December 1, 1969. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 5 Cir. 19 , F.2d [No. 26,285, ], rev’d in part,

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 38 U.S.L.W. 3265,

January 14, 1970.

2 Id.

A2

6, 1970, there were only 3,028 blacks (17%) as compared

with 14,629 whites (83%) enrolled in public schools.3 There

are only three schools (Rosenwald Junior High and Harris

and Patterson elementary schools) that pose a serious

problem. These were originally built to serve Negroes in

a Negro residential area in Panama City, hut the area is

not extensive and the combined enrollment of pupils in

these schools is only 1,413 or less than seven per cent of

the total school population of the district. There is no

serious busing problem.4 Bay County, located in the

Florida panhandle, has a population of 70,000. Most of

its residents and schools are in the Panama City area.

After the Supreme Court’s holding in Carter v. West

Feliciana Parish School Board, 1970, H.S. ,

S.Ct., 24 L.Ed. 2d 477, a companion case to this case, and

after remand of this case to the district court, the School

Board and Health, Education, and Welfare Department

filed desegregation plans. HEW acted through the Florida

School Desegregation Consulting Center, University of

Miami. The Center is partially funded by HEW and

works with the Office of Education in school desegregation

matters within the State of Florida to devise desegrega-

8 The Bay County school system is composed of 2 senior high

schools, 4 junior high schools, 19 elementary schools and 1 voca

tional school.

4 The record is not fully developed on the amount of transporta

tion required under the two plans. The Superintendent testified

that implementation of the HEW plan would require the busing

of 897 students more than the 5,134 being bused under free choice.

However, of the students being bused, only 3,117 lived more than

2 miles from school and so were required by Florida law to be

transported.

In this regard, the record indicates that Bay County transported

6,297 students in 1968-69. For that year, only four schools in the

system had no transported students. Harris was the only Negro

school without bused students. The system currently operates 45

buses.

A3

tion plans. A plan was formulated by a team from the

Center, headed by Dr. Gordon Foster of the University of

Miami, who is Director of the Center, and composed of

eleven staff members, and nine special consultants, includ

ing educators from two other Florida school districts and

from faculties of several universities both in Florida and in

other states.5

The Board filed objections to the HEW plan and on

January 14 filed a proposed plan which called for the

conversion of the three remaining black schools to special

centers and the assignment of regular black students to

white schools. On January 26, the day before the hearing

in the district court, the school board filed an Amended

Proposed Plan, which provides for geographic attendance

zones for all schools of the system. This Amended Plan

stated that the Board had formally rescinded its previous

plan.

Under all three plans, the school board would move from

a free choice system to a geographic zoning system. The

essential difference in the plans is that under the Board’s

plan there would be little desegregation in the remaining

5 The desegregation plan prepared by the Florida School De

segregation Consulting Center (HEW) had three key objectives:

(1) Moving the Bay County schools from a freedom of choice

assignment pattern at the junior and senior high and ele

mentary grade levels to assignments by geographic zones at

all levels;

(2) Desegregating the student bodies at the three schools which

were currently all-black or nearly so—Harris Elementary,

100% black; Patterson Elementary, 99.7% black; and Rosen-

wald Junior High, 100% black; and

(3) Desegregating the schools in such a manner as to minimize

additional transportation Costs and at the same time lessen

the probability of “ white flight” or the transfer of students

to private schools.

A4

Negro schools6 and for at least one of these schools it

appears the zone was drawn in a manner that restricts

desegregation. In contrast, under the HEW plan an af

firmative effort is made to desegregate the three schools

and to do so in such a manner as to “ minimize additional

transportation costs and at the same time lessen the prob

ability of ‘white flight’ or the transfer of students to

private schools. ’ ’7

We turn now to the three problem schools, traditionally

all-Negro. Rosenwald, which originally served grades 7-12,

has a capacity for 1,000 students. Since the high school

grades were phased out, the school has served only 350

Negro junior high students. At the same time the three

white junior highs have been filled to capacity for several

years. However, rather than assign white students to

Rosenwald to relieve overcrowding, the Board established

seventh grades at two white elementaries, Millville and

Hutchison Beach, which enroll about 450 junior high age

students.

The Board’s zone for Rosenwald is not based on the

school’s full capacity, but rather duplicates the limited

6 The Superintendent testified that the zones for the black schools

were drawn by the principals of these schools and were drawn

without regard to race. He testified no attempt was made to de

termine how many blacks and whites were in each zone; that no

attempt was made to draw zones so as to have both, blacks and whites

represented; and that no attempt was made to draw the zones so

they would affirmatively promote desegregation.

7 The effect of the two plans on the three traditionally Negro

schools is shown by the following chart:

School Cap.

9 /1969

E n ro llm en t

H E W P ro j.

E n ro llm en t

B d ’s P ro j.

E n ro llm en t

2 /1 9 7 0

E n ro llm en t

W N T W N T W N T W N T

B osenw ald 1000 0 377 377 629 191 820 127 378 505 75 275 350

H a r r is 650 0 595 595 256 82 338 16 593 609 3 472 475

P a tte rso n 680 2 626 628 324 84 408 171 485 656 115 473 508

A5

enrollment of tlie school under free choice. Thus, while

the school has a capacity of 1,000, the Board’s zone was

drawn to fill the school to half that number (505), and the

actual enrollment in February (350) constitutes about %

of the school’s full capacity. The effect is to restrict the

geographic area which the school serves, with the result

that the school remains predominantly black.

In contrast, HEW proposed zoning 820 students into

Rosenwald, about 180 less than the full capacity (which

would leave space for some special classes or projects, isuch

as the Educable Mentally Retarded Unit). Thus, the at

tendance zone would necessarily cover a larger geographic

area, with the result that a greater number of white stu

dents would be within the Rosenwald zone. There would be

sufficient space in the junior highs for the special seventh

grades at Millville and Beach elementaries to be absorbed

in the regular junior high program.

Under the Board’s plan, Patterson and Harris would

each serve grades K-6. Because of residential patterns

both schools remain majority Negro. As of February 6,

Harris had only 3 of a projected 16 whites enrolled, while

Patterson was attended by 115 of a projected 171 whites.

In order to reduce the probability of white flight from

these schools and their re-segregation, HEW proposed that

Harris and Patterson schools be paired with nearby white

elementaries. Under this proposal, Patterson would be

paired with Millville (approximately 2 miles away) in a

single geographic zone. Harris would be paired with North-

side, approximately 2% miles away, in a similar large zone.

All students within each zone would attend grades K-3 at

the white school, and grades 4, 5, and 6 at the Negro school.

Under such a combination geographic zone-pairing assign

ment provision, each school would have a substantial white

enrollment. HEW projected that under its proposed zones,

each school would be about 75% white.

As Florida law requires students living more than two

miles from their school to be transported, the pairing

A6

proposal would necessitate the transportation of a number

of students. Of these schools, only Patterson has had a

substantial number of its students transported in the past.

At the elementary level, HEW also proposed retaining

two “ transportation islands”, or small non-contiguous

zones, previously employed by the Board to implement dis

trict court orders directing that Negro schools be closed

and their students reassigned to white schools. The limited

number (not more than 71) Negro students from these

-small zones would be transported to two traditionally white

elementaries. However, even if these students were as

signed to the schools nearest their homes, the HEW pro

jections indicate it would not affect the majority white

enrollments at the schools.

Despite the circumstances which suggest that a plan

could be devised which would eliminate vestiges of discrimi

nation in Bay County, the Board adopted a student assign-

ment plan that to a great extent perpetuates ‘ ‘ the comfort

able security of the old, established discriminatory pat

tern”. Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 1968, 391 U.S.

450, at 459, 88 S.Ct. 1700, 20 L.Ed. 2d 733.

According to the testimony of the Superintendent at the

February hearing only 385 of the approximately 2530 Negro

junior high and elementary students would be zoned into

white schools under the Board’s plan. This number is

substantially less than the number of Negro students en

rolled in these -schools in September 1969 under the free

choice plan. Thus, strict adherence to the geographic zones

would have the effect of trapping Negro students in Negro

schools. However, the Board adopted the policy of assign

ing to white schools all Negro students who had chosen to

attend these schools under free choice, regardless of the

location of their residences. Thus, the 1286 Negro students

shown in the February report to be enrolled in white

schools represents not only those zoned into white schools,

but also all others who had selected them under free

choice. At the same time, the three remaining Negro

schools have enrollments of 60%-99% black.

A7

The report with the court shows that as of February 6,

of the 314 whites which the Board projected would be zoned

into black schools only 193 of these were actually in attend

ance. This is hardly unexpected in light of the fact that

in the past no whites (other than a handful of kindergarten

students) had chosen to attend Negro schools, despite the

Board’s proposal to improve Negro schools in order to

attract whites.

As we see it, the zone for Rosenwald should be based on

the full capacity or nearly full capacity of that school, as

proposed by HEW. (But see the last paragraph of this

opinion.) Such a zone could, as the HEW proposal sug

gests result in a majority white student population at the

school. At the elementary level, the Board made no affirma

tive effort to desegregate the two remaining Negro schools.

Indeed, as the Superintendent testified, no attempt was

made to determine the effect the Board’s zones would have

on desegregation and the Board rejected reasonably avail

able alternatives proposed by HEW which would have

totally desegregated these 'Schools.

The record contains suggested alternatives available to

the Board which would totally eradicate all vestiges of the

dual school system and deal with the problems of the flight

of white parents and resegregation. This could be accom

plished at the junior high level simply by drawing a zone on

the basis of the full capacity of the school. At the elemen

tary level, the Negro schools could be paired with white

schools.

This Court requires school boards to draw zone lines so

as to affirmatively promote desegregation of racially dual

school systems. Valley v. Rapides Parish School Board, 5

Cir. 1970, F.2d [No. 29,237, March 6, 1970;] United

States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School District, 5

Cir. 1969, 410 F.2d 626 cert, denied 38 L.W. 3254; United

States v. Greemvood Municipal Separate School District, 5

Cir. 1969, 406 F.2d 1086; Davis v. Board of School Com

missioners of Mobile County, 5 Cir. 1968, 393 F.2d 690,

A8

694; Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 5 Cir. 1969, 409 F.2d 682; United Slates v. Choctaw

County Board of Education, 5 Cir. 1969, 417 F.2d 838;

Braxton v. Board of Public Instruction of Duval County, 5

Cir. 1968, 402 F.2d 900. We approve the pairing of schools

to promote desegregation. See, e.g., Hall v. St. Helena

Parish, 5 Cir. 1969, 417 F.2d 801 at 809; United States v.

Choctaw County, 5 Cir. 1969, 417 F.2d 838 at 842; Dowell v.

Board of Education of Oklahoma City, 10 Cir. 1967, 375

F.2d 158. See also Green v. County School Board of New

Kent County, , 391 U.S. at 442, n. 6; Raney v. Gould

School District, , 391 U.S. at 448.

This Court’s decisions in United States v. Greenwood

Municipal Separate School Dist., 5 Cir. 1969, 406 F.2d

1086; Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist.,

5 Cir. 19 , 409 F.2d 682, cert, denied, 1969, 396 TJ.S. 940;

and United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School

Dist., 5 Cir. 1969, 410 F.2d 626, cert, denied, 1970, 24 L.Ed.

2d 503; accord, Valley v. Rapides Parish School Bd., 5 Cir.

1970, F.2d [No. 29,337, March 6, 1970], makes

abundantly clear that a school board does not meet its con

stitutional duty to disestablish the dual school system by

drawing geographic attendance zones according to every

other possible criterion except promotion of desegregation.

Without such a consideration of a plan’s ability to effect

desegregation, geographic zoning is no more acceptable

constitutionally than freedom of choice.

In Greenwood, we said:

Counsel for the school board argues that a geographic

zone does not contravene the Fourteenth Amendment

if it is drawn according to objective criteria and not

along racial lines. This assessment of the equal protec

tion clause as it applies to school desegregation fails

to take into account the affirmative duty of school

boards in this Circuit to abolish state-compelled educa

tional segregation and establish in its place a unitary

system. This affirmative duty was spelled out in Jef

ferson and reaffirmed in Green and Raney.

Id. at 1093.

A9

And in Henry v. Clarks dale, this Court declared a geo

graphic zoning plan constitutionally impermissible where

it was ishown to freeze in past discrimination and to be

formulated with concern for disturbing the patrons as

little as possible in their established ischool attendance pat

terns rather than effecting desegregation. In a context

where residential segregation was apparently present, the

Court indicated that that factor was irrelevant to the con

stitutional issues:

. . . The ultimate inquiry is not whether the school

board has found some rational basis for its action, but

whether the Board is fulfilling its duty to take affirma

tive steps, spelled out in Jefferson and fortified by

Green, to find realistic measures that will transform

its formerly de jure dual segregated school system into

a unitary, non-racial system of public education.

Id. at 687.

This Court went on to hold that basic criteria such as maxi

mum utilization of school buildings, density of population,

proximity of pupils to schools, natural boundaries and wel

fare of students could be used by school boards to deter

mine zoning configuration, except where the net effect

would be to freeze in past discrimination. In no event

were “ historical boundaries” —• those that historically

separated white and Negro residential areas — to be con

sidered natural boundaries in arriving at attendance zones.

Id., 687-688. But these were not the only criteria neces

sary to meet the constitutional requirements. As this

Court indicated:

. . . '[T]here is a sixth basic criterion . . . promotion

of desegregation. Jefferson, Stell, Davis, Braxton,

Polk County, Carr, Bessemer, Adams, Graves and

Greenwood and other cases decided by this Court, and

now Green v. County School Board of New Kent

County, require school authorities to take affirmative

action that will tend to eradicate all vestiges of the dual

system. For example, given a choice of alternatives,

a school board should draw zone lines, locate new

schools, consolidate schools, change feeder patterns,

A10

and resort to other measures that will reduce the effect

of past patterns tending to maintain segregation (or

token desegregation). ‘ ‘Where the board is under com

pulsion to desegregate the schools . . . we do not think

that drawing zone lines in such a manner as to disturb

the people as little as possible, is a proper factor in

rezoning the schools.”

Id., at 688.

We reiterate what was said in United States v. Jefferson

County, 5 Cir. 1966, 372 F.2d 836, 876.

The Constitution is both color blind and color con

scious. To avoid conflict with the equal protection

clause, a classification that denies a benefit, causes

harm, or imposes a burden must not be based on race.

In that sense, the Constitution is color blind. But the

Constitution is color conscious to prevent discrimina

tion being perpetrated and to undo the effects of past

discrimination. The criterion is the relevancy of color

to a legitimate governmental purpose.

At this point, and perhaps for a long time, true nondis

crimination may be attained, paradoxically, only by taking

color into consideration. Accord, Board of Public Instruc

tion of Duval County v. Braxton, 5 Cir. 1968, 402 F.2d 900;

United States v. Board of Public Instruction of Polk Coun

ty, 5 Cir. 1968, 395 F.2d 66; Wanner v. County School Bd.

of Arlington County, 4 Cir. 1966, 357 F.2d 452; Dowell v.

School Bd. of Oklahoma City, W.D. Okla. 1965, 244 F.

Supp. 971, aff’d 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir.)., cert, denied,

1967, 389 U.S. 847.

We again note that the Bay County School Board has

“ produced impressive results” in desegregation. At the

same time, we have concluded that it has not gone far

enough. We reverse and remand this case for proceedings

consistent with this opinion. We suggest to the district

court that it would be helpful to order that the team from

HEW work with school officials to revise the geographic

A l l

zones proposed Tby HEW on the basis of the up to date

pupil locator maps. These proposals should then be filed

with the court and the parties permitted to file any objec

tions or proposed modifications, after which the district

court should hold a prompt hearing and shall approve a

more effective desegregation plan to be put into effect in

September 1970.

In the light of up-dated information and other pertinent

facts, HEW and the Board should explore the feasibility

of retaining the classrooms especially designed for the

Educable Mentally Retarded Unit at Rosenwald School.

Consideration should also be given to retention of the

County-Wide Education Media Center at Rosenwald or its

relocation at another school.

The judgment is REVERSED and REMANDED for

proceedings consistent with this opinion.

Coleman, Circuit Judge, Concurring in part and dissenting

in part:

In this case, the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare recommended that the Bay County Educable

Mentally Retarded Program, established in 1967 at Rosen

wald, be relocated. The majority of this Panel directs that

the feasibility of retaining this program at Rosenwald be

explored. In this I heartily concur.

In all other particulars I respectfully dissent. It seems

to me that this decision again allows statistics, in isolation,

to outweigh all other considerations. I would hold that

Bay County in fact does have a public school system in

which no child is deprived of the right to attend a school

on account of his race or color.

I would not further disrupt this school system solely to

attain a more evenly distributed racial balance, which, as I

understand it, is not required by the Constitution if the

school system is a unitary one.

I would affirm the Judgment of the District Court.

A12

APPENDIX B

ORDER DENYING REHEARING

U N IT E D STA TES COU RT OE A PPEA L S

F IF T H C IR C U IT

O F F IC E OF T H E C LER K

September 11, 1970

Edward W. Wadsworth

Clerk

Room 408-400 Royal St.

New Orleans, La. 70130

(504) 527-6514

To A ll P arties L isted B elow

R e : No. 29369—Youngblood, et al v. Board of Public

Instruction of Bay County, Fla., et al

Gentlemen:

You are hereby advised that the Court has today entered

an order denying the Petition ( ) for Rehearing in the

above case. No opinion was rendered in connection there

with. See Rule 41, Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure

for issuance and stay of the mandate.

Coleman, Circuit Judge, dissents.

Very truly yours,

E dward W . W adsworth,

Clerh

By F rances W olff

Deputy Clerh

A13

APPENDIX C

NEW PLAN DIRECTED BY DISTRICT COURT

PURSUANT TO DECISION BELOW

I. District Court's Order

IN ' T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTR IC T COURT EOR T H E

N O R T H E R N D ISTR IC T OE FLORIDA

M A R IA N N A D IV ISIO N

Marianna Civil Action No. 572

J ean Carolyn Y oungblood et al, Plaintiffs,

U nited S tates of A merica, Plaintiff-hitervenor,

vs.

T he B oard of P ublic I nstruction of B ay County, F lorida

et al, Defendants.

Order

Pursuant to the order of this Court entered in the above

styled cause on August 3, 1970, representatives of the Office

of Education, Department of Health, Education and Wel

fare met with defendant school officials to attempt to work

out a plan to convert the existing Bay County system to

a unitary system in light of the July 24, 1970 decision of

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

The defendants and officials of the Office of Education were

unable to agree to a desegregation plan. Therefore, the

defendant school board submitted a proposed plan to the

Court and HEW prepared and submitted its proposed plan.

The Court held a pretrial conference followed by a hearing

in open Court to consider these plans and held that both

jilans were unacceptable. An alternate plan was presented

to the Court which all parties agree can establish a unitary

school system in Bay County, Florida, a copy being at

tached hereto and made a part hereof.

The Court having considered said plan, it is hereby

ordered:

1. That the attached plan is hereby approved and shall

be implemented by the Bay County School Board immedi

ately.

A14

2. The school board shall prepare and lute in. this Court

with copies to all counsel a report on the usual forms here

tofore required in this case by this Court, on or before

September 15, 1970.

3. The attached plan is hereby modified and amended

to substitute a new zone for the Parker Elementary

School zone as follows:

Beginning at the intersection of Martin Bayou Bridge

and Cherry Street, East on Cherry Street to TJ. S.

Highway 98, South on TJ. S. Highway 98 to Hickory

Street, East on Hickory Street and Hickory Street

Extension to mouth of Bailey Bayou, East down the

middle of Bailey Bayou to Callaway Bayou, South

along the center of Callaway Bayou to East Bay, East

through the center of East Bay, East through the

center of East Bay to Bay-Gulf County Line,

South on the County Line to the Gulf of Mexico, West

along the shoreline of the Gulf of Mexico to the easterly

border of Tyndall Air Force Base Reservation, North

along easterly border of the Tyndall Air Force Base

Reservation to East Bay, West through the center of

East Bay and St. Andrew Bay to the mouth of Martin

Bayou, North along the center line of Martin Bayou to

point of beginning.

4. The Court reserves jurisdiction of this cause to evalu

ate the plan in practice to determine that a unitary school

system is established in Bay County, Florida.

5. All other provisions of this Court’s order of January

30, 1970, except as herein specifically modified, shall remain

in full force and effect.

DONE and ORDERED in Chambers in Tallahassee,

Florida, this 14th day of August, 1970.

/s / David L. Middlebbooks

David L. Middlebrooks

United States District Judge

A15

2. District Court's Plan

[Caption Omitted]

PROPOSED DESEGRATION PLAN

UTILIZING AREA SIXTH GRADE CENTERS

AT HARRIS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL AND

PATTERSON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

Prepared by:

T he B ay County S chool B oard

( F ormerly

T he B oard of P ublic I nstruction

of B ay County, F lorida)

August 14, 1970

BAY C O U N T Y SC H O O L BOARD REV ISED JU S T IC E

D E PA R T M E N T P L A N

August 1970

A. D. Harris Area 6th Grade Center

All students and teachers from the sixth grades of the

following elementary schools shall attend A. D. Harris

Area 6th Grade Center:

SCHOOL NUMBER OF STUDENTS

Cherry Street 98

Cove 64

A. D. Harris 71

Lucille Moore 95

Northside 77

Oakland Terrace 83

St. Andrew 36

T otal 524

White

Black

A16

73%

27%

385

139

Total 524 100%

Capacity 527

Total K-5 Students Transferring Out 423

The Board shall assign the pupils and teachers of grades

K-5 at Harris to the elementary schools listed above. Ad

joining school zones will be adjusted and transportation

islands developed in re-assigning the K-5 students to the

nearest school center.

A17

BAY C O U N T Y SC H O O L BOARD REV ISED JU S T IC E

D E PA R T M E N T P L A N

August 1970

Oscar Patterson Area Sixth Grade Center

All students and teachers from the sixth grades of the fol

lowing elementary schools shall attend the Oscar Patterson

Area Sixth Grade Center :

SCHOOL NUMBER OF STUDENTS

Callaway 110

Cedar Grove 61

Millville 54

Parker 111

Patterson 75

Springfield 131

T o t a l 542

White 469 8 7 %

Black 73 1 3 %

Total 542 100%

Capacity 618

Total K-5 Students Transferring Out 508

The Board shall assign the pupils and teachers of grades

K-5 at Patterson to the elementary schools listed above.

Adjoining school zones will be adjusted and transportation

islands developed in re-assigning the K-5 students to the

nearest school center.

A18

BAY C O U N TY SC H O O L BOARD REVISED JU S T IC E

D E PA R T M E N T PL A N

August 1970

J unior H igh S chools

Everitt Junior High School

Beginning at the intersection of East Avenue and Easterly

extension of 19th Street, proceeding easterly along the

easterly extension of 19th Street to the Bay-Gulf County

Line, South on the County Line to the Gulf of Mexico, West

along the shoreline of the Gulf of Mexico to the Eastern

border of Tyndall Air Force Base Reservation, North along

the eastern border of the Tyndall Air Force Base Reserva

tion to East Bay, West through the center of East Bay and

St. Andrew Bay to the mouth of Watson Bayou, North up

the center of Watson Bayou to Business Highway 98, East

on Business Highway 98 to East Avenue, North on East

Avenue to point of beginning.

White 996 91%

Black 103 9%

Total 1099 100%

Capacity 1465

Mowat Junior High School

Begin at a point on the Gulf and Bay County Line, on a

line projected easterly from the junction of Highway 231

and State Road 77, proceed west to the junction of U. S.

Highway 231 and State Road 77, south on Highway 231 to

the junction of the St. Andrew Bay Railroad. Follow St.

Andrew Bay Railroad westerly to the east shore of St.

Andrew Bay, west to a projected point in the center of

Hathaway Bridge, northerly through the center line of

North Bay to a center line of the junction of North Bay

and West Bay, proceed through the center line of West

Bay to a projected line east and west from Breakfast

A19

Point, west to the Walton County Line, proceed north and

clockwise to Washington, Jackson, Calhoun, and Gulf Coun

ties to a point of beginning.

White 1161 97%

Black 41 3%

Total 1202 100%

Capacity 1184

BA T C O U N T Y SC H O O L BOARD REV ISED JU S T IC E

D E PA R T M E N T P L A N

August 1970

J unior H igh S chools

Jinks Junior High School

Beginning at a point where Business Highway 98 crosses

Watson Bayou, proceed west on Business Highway 98 to

Cove Boulevard, North on Cove Boulevard to Highway 231,

Southwest on Highway 231 to the junction of the St. Andrew

Bay Railroad, follow St. Andrew Bay Railroad westerly

to the east shore of St. Andrew Bay, West to a projected

point in the center of Hathaway Bridge, Northerly through

the center line of North Bay to a center line to the junction

of North Bay and West Bay, proceed through the center

line of West Bay to a projected line east and west from

Breakfast Point, West to the Walton County Line, South

on the Walton County Line to the Gulf of Mexico, follow

the shoreline of the Gulf of Mexico easterly to St. Andrew

Bay, East through St. Andrew Bay to the projected center

point of Watson Bayou, Northerly in Watson to the point

of beginning.

White 1111 77%

Black 332 23%

Total

Capacity

1443

1670

100%

A20

Rosenwald Junior High School

Beginning at the intersection of Cove Boulevard and Busi

ness Highway 98, north on Cove Boulevard to intersection

of Bay Line Railroad, east on an easterly extension of 19th

Street to East Avenue, south on East Avenue to Business

Highway 98, west on Business Highway 98 to the point of

beginning. All junior high school students residing on Tyn

dall Air Force Base Reservation will attend Rosenwald Jr.

High School.

White 359 56%

Black 284 44%

Total 643 100%

Capacity 663

The Board shall adjust zones and assignments in accord

ance with the capacity of this school center, provided a ma

jority white regular Grades 7-9 enrollment is maintained

at Rosenwald; provided further, that the Board is not re

quired to move the existing Media Center and Special

Education Center from Rosenwald.

The Board shall have the authority to adjust zones and

assignments in accordance with the capacity of each school

center in the county, provided such adjustments do not

affect the desegregation intent of this order.

The Board shall have the right to allow any student to

attend a school outside their attendance zone for compelling

physical and emotional disabilities.

The Board shall endeavor to maintain the current student

capacity at Rosenwald.

A21

APPENDIX D

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF THE ANTI-BUSING

PROVISOS OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS

ACT OF 1964

1. The measure that became the Civil Rights Act of

1964 was recommended to Congress by President Kennedy.

He requested Congress to “ assert its specific constitutional

authority to implement the 14th Amendment” (H.R. Doc.

124, 88th Cong., 1st sess., June 19, 1963, p. 6) with respect

to achieving desegregation in the public schools, first by

accelerating the litigation process, second by a program

of technical and financial assistance to school districts ‘ ‘ en

gaged in the process of meeting the educational problems

flowing from desegregation or racial imbalance * * * ”

(id., p. 7; italics added).

2. The first version of the bills introduced immediately

thereafter and designed to effectuate the Presidential

message (H.R. 7152, Sen. 1731; both 88th Cong., 1st sess.)

had identical provisions. Title III of each, entitled “ De

segregation of Public Education,” contained no less than

five subsections specifically looking to the correction of

racial imbalance (italics added):

“ Sec. 303. (a) The commissioner is authorized,

upon the application of any school board, State, mu

nicipality, school district, or other governmental unit,

to render technical assistance in the preparation, adop

tion, and implementation of plans for the desegrega

tion of public schools or other plans designed to deal

with problems arising from racial imbalance in public

school systems. Such technical assistance may, among

other activities, include making available to such agen

cies information regarding effective methods of coping

with special educational problems occasioned by de

segregation or racial imbalance, and making available

to such agencies personnel of the Office of Education

or other persons specially equipped to advise and

assist them in coping with such problems.

“ (b) The Commissioner is authorized to arrange,

through grants or contracts, with institutions of higher

education for the operation of short-term or regular

A22

session institutes for special training designed to im

prove the ability of teachers, supervisors, counselors,

and other elementary or secondary school personnel to

deal effectively with special educational problems oc

casioned by desegregation or measures to adjust racial

imbalance in public school systems. * * *

“ Sec. 304 (a) A school board which has failed to

achieve desegregation in all public schools within its

jurisdiction, or a school board which is confronted

with problems arising from racial imbalance in the

public schools within its jurisdiction, may apply to

the Commissioner, either directly or through another

governmental unit, for a grant or loan, as hereinafter

provided, for the purpose of aiding such school board

in carrying out desegregation or in dealing with prob

lems of racial imbalance.

“ (b) The Commissioner may make a grant under

this section, upon application therefor, for—

“ (1) the cost of giving to teachers and other

school personnel inservice training in dealing with

problems incident to desegregation or racial imbal

ance in public schools; and

“ (2) the cost of employing specialists in problems

incident to desegregation or racial imbalance and of

providing other assistance to develop understanding

of these problems by parents, schoolchildren, and the

general public.

“ (c) * # * In determining whether to make a grant,

and in fixing the amount thereof and the terms and

conditions on which it will be made, the Commissioner

shall take into consideration * * * the nature, extent,

and gravity of its problems incident to desegregation

or racial imbalance, and such other factors as he finds

relevant. ’ ’

3. Sen. 1731 never got off the ground, despite its sponsor

ship by no less than 45 senators, while H.R. 7152 was, fol

lowing extensive hearings, completely rewritten in com

mittee. There was reported out an entirely new measure,

see H.R. Rep. 914, 88th Cong., 1st sees., in which former

Title III was renumbered Title IV, and in which every

mention of “ racial imbalance” was deleted. The justifi-

A23

cation for such deletion was set forth in the additional

views of Messrs. McCulloch of Ohio, Lindsay of New York,

Cahill of New Jersey, Shriver of Kansas, MacGregor of

Minnesota, Mathias of Maryland, and Bromwell of Iowa

(id., Part 2, pp. 21-22) :

“ The committee failed to extend this assistance to

problems frequently referred to as ‘racial imbalance’

as no adequate definition of this concept was put

forward. The committee also felt that this could lead

to the forcible disruption of neighborhood patterns,

might entail inordinate financial and human cost and

create more friction than it could possibly resolve.”

Even so, the elimination of the references to racial im

balance did not satisfy one of the dissenting members,

who complained (H.R. Rep. 914, supra, at p. 84) that

‘‘this action [i.e., such elimination] is a matter of ‘public

relations’ or semantics, devised to prevent the people of

the United States from recognizing the bill’s true intent

and purpose. The administration apparently intends to

rely upon its own construction of ‘discrimination’ as in

cluding the lack of racial balance as distinguished from a

statutory reference to ‘ racial imbalance ’ * *

4. As reported out by the Judiciary Committee on No

vember 20, 1963 (H.R. 914, supra, at p. 5), Section 401(b)

provided that

“ ‘Desegregation’ means the assignment of students

to public schools and within such schools without re

gard to their race, color, religion, or national origin.”

On January 31, 1964, in the course of an explanation of

the committee substitute, Chairman Celler of the Judiciary

Committee said (110 Cong. Rec. 1518) :

“ There is no authorization for either the Attorney

General or the Commissioner of Education to work

toward achieving racial balance in given schools. Such

matters, like appointment of teachers and all other

internal and administrative matters, are entirely in

the hands of the local boards. This bill does not

change that situation.”

A24

On February 6, 1964, Mr, Cramer of Florida, who had

earlier expressed concern lest the bill as rewritten by the

Judiciary Committee had failed to eliminate racial bal

ancing from its proposals for desegregation (110 Cong.

Rec. 1598), moved an amendment to provide that “ ‘de

segregation’ shall not mean the assignment of ;students to

public schools in order to overcome racial imbalance.”

Chairman Celler accepted that amendment (110 Cong. Rec.

2280), and, as thus amended, Section 401(b) was adopted

by the House.

5. The House passed H.R. 7152 on February 10, 1964

(110 Cong. Rec, 280'5). In the Senate, the measure was

placed on the calendar without reference to committee (id.

3719, Feb. 26), and was taken up for consideration on

March 26 (id. 6417). As is well known, three months of

debate ensued.

Because of the absence of committee action, H.R. 7152

was rewritten by the joint leadership in the course of the

debate, and on May 26, Amendment No. 656 in the nature of

a substitute was offered by Senators Dirksen (Minority

Leader), Mansfield (Majority Leader), Humphrey (Ma

jority Whip), and Kuchel (Minority Whip) (110 Cong. Rec.

11926). Included in Amendment No. 656 was a new proviso

to Section 407(a) reading as follows (id. at 11929):

“ provided that nothing herein shall empower any offi

cial or court of the United States to issue any order

seeking to achieve a racial balance in any school by re

quiring the transportation of pupils or students from

one school to another in order to achieve such racial

balance, or otherwise enlarge the existing power of

the court to insure compliance with constitutional

standards.”

This proviso did not appear either in H.R. 7152 as re

ported out by the House Judiciary Committee (H.R. Rep.

914, 88th Cong., 1st sess., p. 7) or in H.R. 7152 as it reached

the Senate. Chronology indicates that the proviso was

drafted to allay the fears of numerous opponents of the

measure as a whole, who had earlier argued that, as it

A25

passed the House, it would permit the transportation of

school children back and forth to achieve racial balance