Plaintiffs' Memorandum of Law on Metropolitan School Desegregation

Public Court Documents

March 22, 1972

11 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Memorandum of Law on Metropolitan School Desegregation, 1972. e397aaaa-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8d3e3eef-146b-4132-9171-cc46a946c62e/plaintiffs-memorandum-of-law-on-metropolitan-school-desegregation. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

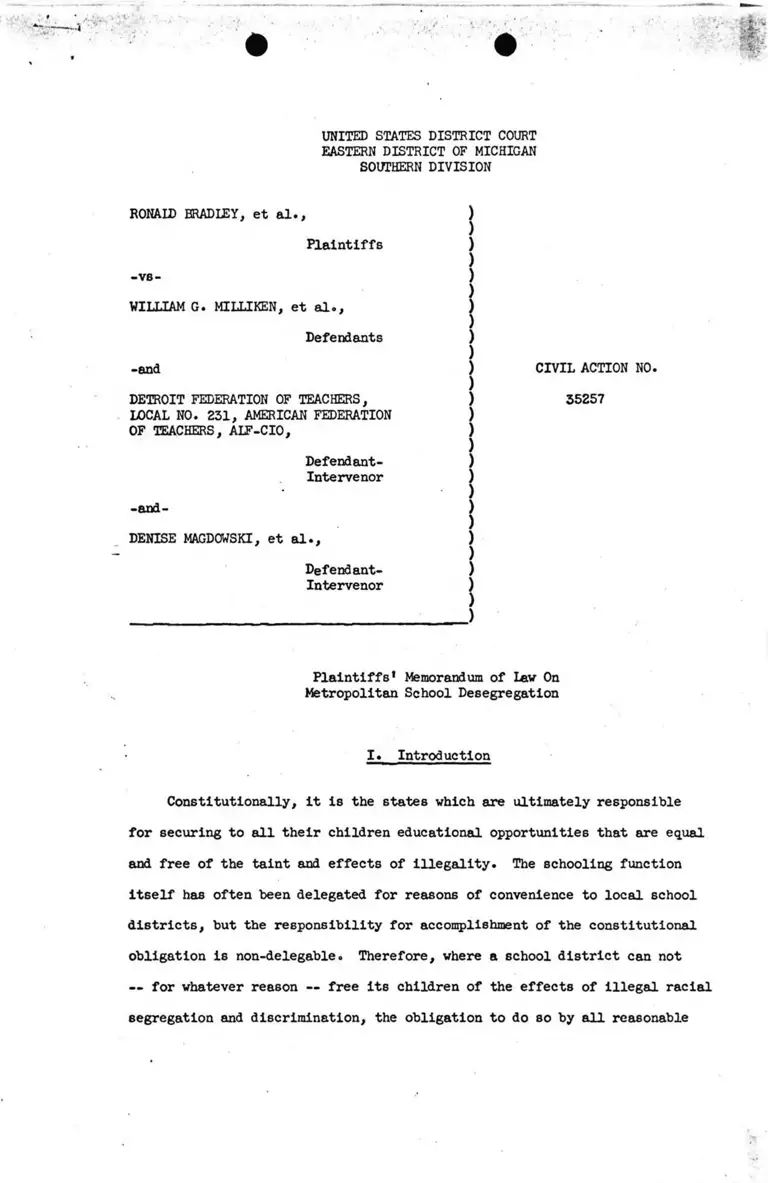

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONAID BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs

-V 8 -

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants

-and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL NO. 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, ALF-CIO,

Defendant-

Intervenor

-and-

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

Defendant-

Intervenor

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

.)

CIVIL ACTION NO.

35257

Plaintiffs’ Memorandum of Law On

Metropolitan School Desegregation

I. Introduction

Constitutionally, it is the states which are ultimately responsible

for securing to all their children educational opportunities that are equal

and free of the taint and effects of illegality. The schooling function

itself has often been delegated for reasons of convenience to local school

districts, but the responsibility for acconqalishment of the constitutional

obligation is non-delegable. Therefore, where a school district can not

— for whatever reason — free its children of the effects of illegal racial

segregation and discrimination, the obligation to do so by all reasonable

means necessary is that of the state. And in such a situation it matters

not whether the state was a malefactor in the district’s plight, because

it is the obligation of the state to accomplish for all children, through

districts or otherwise the equal protection of the laws.

In addition, where it is shown that a state has contributed to segrega

tion within, and racial isolation of, a school district, its obligations

are more affirmative and. immediate than remedial and last resort. In neither

case, however, may the constitutionally responsible educational authority

rely upon artifacts of convenience, such as school district boundaries,

as impediments to constitutionally required remedies.

We submit that the record in this case at this writing, includes

one desegregation plan (PC- 2 , as amended) that would be constitutionally

adequate if it were legally permissible or practically sensible to constrain

the operation of a plan to Detroit proper. We also submit, however, that

such a plan would not meet the ultimate educational authority's present

constitutional responsibility toward pupils in Detroit or its metropolitan

area, namely, to adopt and implement that plan which promises realistically

to accomplish now the greatest possible degree of actual desegregation,

and to maintain now and hereafter only racially unitary schools.

Therefore, we urge that it would be error for this Court not to hear

and consider plans for metropolitan school desegregation.

II. Argument

This Court has found that, because of the acts of the State of Michigan

and the Detroit Board of Education, the segregation existing in the Detroit

public schools violates the Constitution. Ruling on Issue of Segregation,

Bradley v. Milliken, C.A. No. 35257 (E.D.Mich. Sept. 27, 1971). It is

therefore the duty of this Court to intervene to "eliminate from the

public schools all vestiges of state-imposed segregation." Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenberg Bd. of Ed., 402 U.S. 1, 15(l97l). The District

Court and the parties should make every effort to "achieve the greatest

possible degree of actual desegregation, taking into account the

practicalities of the situation." Proceedings held in Bradley v. Milllken,

(E.D. Mich. Oct. 4, 1971) Tr. 6; Davis v. Bd. of School Commissioners, 402

U.S. 33, 37(1971); cf. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Bd. of Ed., 402 at 26.

The goal must be the elimination of identifiably black or white schools in

order to create just schools, now and hereafter. Green v. County School

Board, 391 U.S. 430, 442(1968); Alexander v. Holmes County School Bd.,

396 U.S. 19(1969). In this process of determining which remedy i6 proper

and necessary, the Court is guided by the principles enunciated in Green:

it is the obligation of this Court to assess the effectiveness of proposed

plans of desegregation in light of the circumstances present and the

available alternatives; the Court must then choose the alternative, or

series of alternatives, which promise realistically to work now and hereafter

to produce the maximum actual desegregation. Green v » County School Board,

391 U.S. at 439 and 442. And there can be no doubt that once having found

a right and a violation, this Court's power to fashion complete and effective

relief is very broad. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Bd. of Ed., 402 U.S.

at 15; U.S. v. Louisiana 380 U.S. 145( ). .

A. The Necessity of a Metropolitan Plan of Desegregation

In light of these controlling principles, on the basis of the findings

of this Court, Ruling on Issues of Segregation, and the evidence adduced in

the numerous hearings before this Court, it is obvious that a desegregation

plan limited to the City of Detroit is not the most effective plan for

ultimate and complete vindication of plaintiffs' rights as adjudicated in

this cause. First, where the Detroit public schools are now 65$ black

(and increasingly have higher percentages of black children at the elementary

level), while suburban schools remain virtually all white, the pattern of

containment of white and black children in separate schools by force of

state action cannot reasonably be held to be fully eradicated. City

Hearings Tr. 399(Foster). Within the context of this larger school community,

any plan of desegregation limited to the city schools will not eliminate the

pattern of racial identification affixed to the Detroit public schools by

stall action even if it may help to alleviate the racial identifiability of

schools within the city. City Hearings, Tr. 361-362, 365-367, 399(Foster).

Cf. City Hearings, Tr. 467-468(Guthrie). Second, within the 6tate-wide

system of public education, the immediate availability of white suburban

schools to white parents wishing to avoid compliance with the mandates of

the Constitution cannot help but threaten the continuing operation "now

2

and hereafter" of soundly desegregated schools, especially to the extent 1 2

1

The pattern is unmistakable: "Residential segregation within the city and

throughout the larger metropolitan area is substantial, pervasive and of long

standing. Black citizens are located in separate and distinct areas within

the city and are not generally found in the suburbs. While the racially

unrestricted choice of black persons and economic factors may have played

some part in the development of this pattern of residential segregation, it

is, in the main, the result of past and present practices and customs of racial

discrimination, both public and private, which have and do restrict the

housing opportunities of black people. Perhaps the most that can be said is

that all of them Various governmental units/*, including school authorities,

are, in part, responsible for the segregated condition which exists." Ruling

on Issue of Segregation 8-10. Moreover, an examination of PX 181, 182 and 185

shows that black children often remain isolated in predominately black schools

In the few suburban school districts with any numbers of black pupils.

2

We note here that, in our view, the defendants have consistently misunder

stood the constitutionally permissible consideration that may be given by this

Court to predictions of white flight. From the days of Brown II, 349 U.S. 294

(1955), through Cooper v« Aaron, 358 U.S. 1(1958) and Monroe v. Board of Comm-ts.,

.391 U.S. 450, 459(1968), the Supreme Court has consistently held that community

opposition to desegregation, by white flight or otherwise, may not limit the

requirement or effectiveness of desegregation plans. Similarly, it is

established that a system’s preference for majority white (or other quotas)

schools is an impermissible limit upon the "greatest possible degree of

actual desegregation" requirement, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed.,

402 U.S. 1, 24, Note 8, (1971)j Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 429 F.2d 820,

826(4th Cir. 1970). We submit that those holdings invalidate the Detroit

defendants’ principal objection to plaintiffs' Intra-Detroit plan.

On the other hand, we agree that educational soundness — as well as legal

requirements, see Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19

(1969) — mandate that the defendants shall operate only racially desegregated

schools "now and hereafter". That is, avoidance of resegregation may legitl-

mately be considered by this Court in choosing among proffered plans.

Indeed, on the facts of this record, it would be an abuse of discretion, if

not sin error of constitutional dimensions, were this Court to fail to consider

readily available (metropolitan) plans that promise more realistically than

others to operate now and hereafter only racially desegregated schools.

4

to which whites, now residents in the city, axe able to afford the move.

City Hearings, Tr. 300, 371-372, 400(Foster). Df. City Hearings, Tr. 462-464,

476(Guthrie). Third, the existence within the state-wide system of public

education of a set of white schools in the suburbs abutting another set of

black schools in the city suggests that desegregation of many city schools

may be accomplished more easily and completely by including suburban schools

in any plan. See P.X. 185, 181, 182, 184. Fourth, the immediate availability

of substantial numbers of white schools in the suburbs within convenient time

and distance of black schools within the city suggests that plans limited to

the city cannot achieve the maximum actual desegregation possible. City

Hearings, Tr. 376(Foster). Plans looking toward metropolitan desegregation

are therefore ultimately more effective alternatives to even the most effective

intra-city desegregation plan. The State attorney’s hypothetical questions

about the practical limitations on desegregation if Detroit were an islard in

the ocean only highlight the obvious: the Detroit public schools are instead

separated from white suburban schools by happenstance, conceptual lines over

lated and totally reorganized before.

3 -------------- *

Metropolitan relief is also compelled quite apart from considerations of

remedy alone: the nature of the violation also compels such relief. Cf.

Swann, supra at 16. First, the State act (Act 48) of interposition in

thwarting implementation of the April 7 plan of partial high school desegre

gation frustrated attempts lawfully taken by the defendant Detroit District to

plfi™\ffSI constitutional rights. Bradley v. Milliken. 433 F.2d 897

16th Cir. 1970). Second, in Act 48 the State impeded, delayed and minimized

r??i? Luirt! P ,ati0a in the Detroit schools and imposed a student assignment policy which had the purpose and effect of maintaining segregation. Ruling on Issue of

Segregation at 15. Third, the state through working of various state aid

reimbursement provisions for transportation and other school costs has created

systematic educational inequalities to the detriment of plaintiff children and

sch°o1 district. Ruling on Issue of Segregation at 14. Fourth,

the State, exercising its plenary power over school district organization,

acted to reorganize totally the Detroit school district. Ruling on Issue of

Segregation at 14-15. Fifth, the State was fully aware of the important impact

C0S ! rLCti!? on school segregation (see P.X. 174), but acted in keeping ,

generally, with the discriminatory practices which advanced or perpetuated racial

segregation in the schools. Ruling on Issue of Segregation at 15. Sixth, the

tate sanctioned, at least until 1959, the assignment and transportation of pupils

across school district boundaries which had as its purpose and effect the secre-

gation of pupiis on a racial basis. See, e.g., 11 Tr. 1259-60(1959 Boundary

Guide Book); Drachler Depositions 3/31/71 p. 13, 6/28/71 p. 48. Finally,

public authority at all levels has been heavily implicated in affixing to the

metropolitan area and its schools the segregated pattern and condition which

which the State has plenary power arri which have often been crossed, manipu-

3

5

B. The "Practicalities of the Situation" to be Considered

Thus the real issues before the Court concern "the practicalities of the

situation." In the first instance, this means time: is it feasible to

implement a metropolitan plan of desegregation for the 1972 school year? If

not, the constitutionally required alternative is to implement that intra-city

plan which will be most effective in achieving actual desegregation. As the

Detroit Board’s suggestions do not even purport to be plans of system-wide

desegregation, and on the record promise little, if any desegregation,

plaintiffs' intra-city plan, or a modification thereof, will remain the best

4

available plan of desegregation in the record and must be implemented.

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396 U.S. 226(1969), 396 U.S. 240

(1970); U.S. v. Bd. of Ed. of Baldwin County, 423 F.2d 1013, 1014(5th Cir.

1970). The first issue for the March 28 hearing, then, is whether a

metropolitan plan of desegregation may be implemented for the 1972 school

5

year. 3 4 5

3 continued. . .

now exists. Ruling on Issue of Segregation at 10. Compare Swann at 32. In

all these particulars have the State and its agencies, including the defendants

(and their predecessors in office) now before the Court, acted to control and

maintain the pattern of segregation in schools in this community.

Of course, if Detroit were the island as hypothesized (which as Dr. Rankin

noted, it is not), it would be the "loaded game board" aptly described by

Chief Justice Burger in Swann, supra.

4

' Quite apart from the constitutional requirement of immediacy in Alexander v.

Holmes, 396 U.S. 19(1969), equity demands that plaintiffs be given the maximum

relief possible for the 1972 fall term, a full two years after plaintiffs filed

their complaint, and thereafter in all particulars, except faculty, proved

virtually every one of their allegations, including a long-standing pattern of

illegal school segregation. Relief is long overdue. The future prospect of

"metro" may not be used to delay implementation of a plan of desegregation

limited to the City. Bradley v. Richmond, 325 F.Supp. 828(E.D.Va. 1971).

See also Calhoun v. Cook, 451 F.2d 585 (5th Cir. Oct. 21, 1971), where the

Fifth Circuit reversed the lower courts refusal to implement substantial

relief for Atlanta and ordered the District Court to consider a plan for

intra-city desegregation, even while ordering the lower court to enter

supplementary findings and conclusions on a proposal to consolidate city and

county school-systems.

5

If the proofs in this cause should show that a metropolitan plan cannot be

implemented by the precise day now scheduled for the opening of school, that

opening may be delayed to permit implementation. U.S. v. Texas Education Agency,

431 E2d.1013, 1314(5th Cir. 1970). ......

6

Under the rubric of practicability, the contours, structure, and "nuts

and bolts" working details of competing metropolitan alternatives will remain

to be considered. In our view, it would not be profitable to explore the

varieties of metropolitanism without the benefit of a record on those issues.

Of course, maximum desegregation, educational soundness, and administrative

feasibility are the touchstones. The evidence will show, we believe, that

these are plans in which factors such as actual desegregation, organizational

effectiveness, economies of scale, maximum utilization of equipment and facilities,

and travel times and distances converge at their optimum points. But the

answers to such questions should await the hearing of them. And, of course,

the burden of coming forth with a promising plan remains — undischarged —

that of the defendants] severally, collectively, or in some plausible combina

tion.

III. The Power of this Court to Order a Metropolitan Plan of Desegregation

Apparently, however, the primary "practicality" asserted by the state

defendants as an impediment to metropolitan desegregation is a matter of law:

is there anything so sacrosanct and compelling in a school district boundary,

and the state laws which accompany the existing configuration, es to prohibit

a metropolitan plan of desegregation where it is necessary to effectuate a

complete remedy for existing state-imposed segregation?

The Supreme Court has never held that the boundaries of existing

governmental units within a state may be used to prevent a Court from pro

viding a complete and effective remedy for a constitutional violation.

"Political subdivisions of states — counties, cities, or whatever — never

were and never have been considered sovereigh entities. Rather they have been

traditionally regarded as subordinate governmental instrumentalities by the

. 6

State to assist in carrying out governmental functions." Reynolds v. Sims,

6 “

This is especially true for public education which has been recognized by the

Court as perhaps the most important function of state and local governments.

Brown v. Bd. of Ed., 347 U.S. 483(1954). See also Griffin v. Prince Edward

bounty, 577 U.S. 218(1964). The situation is no different in Michigan.

Ruling on Issue of Segregation at 25-28.

7

377 U.S. 533, 575(1964). School districts and their boundaries are self-im

posed administrative conveniences.

"The equal protection clause speaks to the state. The United States

Constitution recognizes no governing unit except the federal government and

the state. A contrary position would allow the state to evade its constitu

tional responsibility by carve-outs of small units." Hall v. St. Helena

Parish School Bd., 197 F.Supp. 649, 658(E.D. la,. 1961). Accord Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 16-17(1958); Allen v. County School Bd», 207 F.Supp. 349,

353(E.D. Va. 1962); Haney v. County Board of Ed., 410 F.2d 920(8th Cir. 1969).

As the constitutional obligation of state and local authorities toward the

7

individual children is at a minimum a shared one, this Court has the power to

order defendants to implement a plan of desegregation which extends beyond the

borders of the Detroit school district in order to achieve the greatest

possible degree of actual desegregation.

In fact, plaintiffs understand that this position to some extent may

8

already be the law of the case. See Ruling on Issue of Segregation and

Oral Order of Oct. 4, 1971. In any event, "the power conferred by state law

on central and local officials to determine the shape of school attendance

units cannot be employed . . . Jto seal7 off white enclaves of a racial

composition more appealing to the local electorate and obstructing the desegre

gation of schools." Bradley v. Richmond, C.A. No. 3353(E.D.Va. Jan. 5, 1972)

Slip Op. at 64.

7

See Ruling on Issue of Segregation at 25. Under the Constitution of the

United States and the Constitution and laws of Michigan, the responsibility

for providing educational opportunity is ultimately that of the State.

Ruling on Issue of Segregation at 25 and 26. See also Art. VIII Sec. 1-3,

Mich. Const.; Welling v. Livonia Bd. of Ed., 382 Mich. 620(1969).

8

To that extent the issue of the power of this Court to order relief has

already been settled; and to that extent any disagreement may be appealed at

an appropriate time. See Ruling on Issue of Segregation, 25 to 28; and see

Bradley v. Mllllken, Nos. 72-1064, 1065, 1066(6th Cir. Feb. 23, 1972).

8

In such circumstances, even without the direct implication of the State

in the violation at hand, this Court has the power to order the State

defendants (and local districts) to assist in providing a complete remedy,

including the implementation of a plan of desegregation which extends beyond

the city limits. Bradley v. Richmond, Supra, Slip Op. at 53; Franklin v.

Quitman County Board of Education, 288 F.Supp. 509(N.D. Miss. 1968); U.S. v.

Texas Education Agency, 321 F.Supp. 1043(E.D.Tex. 1970), Aff*d; UoS. v. State

of Texas, 447 F.2d 44l(5th Cir. 1971); U.S. v. Texas Ed. Agency,_____F.Supp.

(D.Tex. 1971); Godwin v. Johnston County Board of Education, 301 F.Supp.

1339(E.D. N.C. 1969). In this cause, however, the power of the Court is even

more apparent: the State and its agencies, including the named defendants,

acted directly and discriminatorily to control and maintain the pattern of

segregation in the Detroit schools. Ruling on Issue of Segregation at 14,15,

27 and 28. ‘Vhere a pattern of violation of constitutional rights is estab

lished, the affirmative obligation under the Fourteenth Amendment is imposed

on not only individual school districts, but upon the State defendants in

this case." Ruling on Issue of Segregation at 27.

To afford an adequate remedy for unconstitutional educational inequality

and dejure segregation, this Court will be following the example of many

others in requiring that existing school district boundaries may be disregarded

or restructured and separate governmental units ordered to cooperate, con

solidate or exchange pupils and resources. Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Ed.,

448 F.2d 746(5th Cir. 1971); Burleson v. County Board of Election Commissioners,

308 F.Supp. 352(E.D.Ark.), aff'd 432 F.2d 1356(8th Cir. 1970); Aytch v.

Mitchell, 320 F. Supp. 1372(E.D.Ark. 197l);Stout v. Jefferson County Bd. of Ed.,

No. 29886 (5th Cir. July 1971); Jenkins v. Township of Morris School District,

279 A.2d 619(N.J. 1971); Haney v. County Board of Sevier, 410 F.2d 920(8th Cir.

1969); U.S. v. State of Texas, 447 F.2d 44l(5th Cir. 197l); U.S. v. Crockett

County Bd. of Ed., No. 1663(W.D.Tenn., May 15, 1967); Taylor v. Coahoma County

School District, 330 F.Supp. 174(N.D. Miss. 1971); Robinson v. Shelby County

Board of Education, 330 F.Supp 837 (W.D.Tenn. 1971); Serrano v. Priest, 5

9

Cal. 3d 584(1971); Van Dusartz v. Hatfield, 334 F.Supp. 870(D. Minn. 1971);

Rodriguez v. Texas F .Supp. (D.Tex. 1972). Cf • Calhoun v. Cooky 451

F.2d 583 (5th Cir. Oct. 21, 1971); U.S. v. Bd. of School Commissioners of.

TTY^annpoiis, 332 F.Supp 655(S.D.Ind. 1971). Nor is such judicial inter

vention to order interdistrict reorganization consolidation, cooperation, or

pupil exchange limited by state law: -

Appellees' assertion that the District Court for the District

of Arkansas is bound to adhere to Arkansas law, unless the state

law violates some provision of the Constitution, is not constitu

tionally sound where the operation of the state law in question

fails to provide the constitutional guarantee of a non-racial

unitary school system. The remedial power of the federal courts

under the Fourteenth amendment is not limited by state law.

Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier County, 429 F.2d 364, 368

(8th Cir. 1970). Accord Griffin v. Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218(1964);

North Carolina Board of Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43(l97l); Stout v.

Jefferson County Board of Edo, No. 29886 (5th Cir. July 1971); U.S. v. Greenwood

Municipal Separate School Districts, 406 F.2d 1086, 1094(5th Cir. 1969) and

Adkins v. School Board of ' Newport News 148 F.Supp. 430, 446-7(E.D. Va. 1957),

aff'd 246 F.2d 325, Cert. den. 355 U.S. 855(1957). In fact, the power of the

Court to reorganize school districts to eradicate state-imposed segregation

is not novel; it was specifically recognized in Brown II, 349 U.S. 294,

300-301(1955), as one type of action which may be utilized in formulating an

adequate remedy.

III. Conclusion .

Thus, the propriety and necessity for metropolitan relief, and the Court's

power to order such relief, are clear. The only issues to be explored at the

March 28 hearing are the particular circumstances which will as a practical

matter shape and define the most effective plan. In conclusion we wish to

remind the Court and the parties of one especially poignant fact: there can

be no question of the feasibility of suburban children crossing the boundary

of the Detroit School District. For years black children in the Carver School

District were assigned to black schools in the inner city because no white

suburban district (or white school in the city) would take the children.

10

8 Tr. 885; 11 Tr. 1259-60 (1959 Boundary Guide Book); Drachler Depositions

3/ll/71 p« 13, 6/28/71 po 48. These black children did not trip (nor,

subsequently, did their buses pause) on the school district line. Surely,

school district lines which in the past did not stand in the way of discrim

ination and segregation cannot now be used to block a complete and and

adequate and fair remedy for the constitutional violations found by this

Court.

Respectfully submitted,

/ F?/Lj£L'/-lr'C ct' ^

HAROLD FLANNERY

PAUL R. DIMOND

'ROBERT PRESSMAN

Center for Law & Education

Harvard University

Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138

LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM E. CAIDWELL

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

E. WINTHER McCROOM

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

NATHANIEL R. JONES

General Counsel, N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

, JACK GREENBERG

■ NORMAN J. CHACHKEN

10 Columbus Circle

March 22, 1972 New York, New York 10019

Certificate of Service

I, J. Harold Flannery, of counsel for plaintiffs, hereby certify that I

have served the foregoing memorandum upon the defendants and intervenors by

mailing, postage prepaid, copies to their counsel of record on March 22, 1972.

11