Finney v. Arkansas Board of Corrections Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

November 29, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Finney v. Arkansas Board of Corrections Court Opinion, 1977. cb02eca9-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8d5d5d92-f636-4619-b2cd-d1c633856a90/finney-v-arkansas-board-of-corrections-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

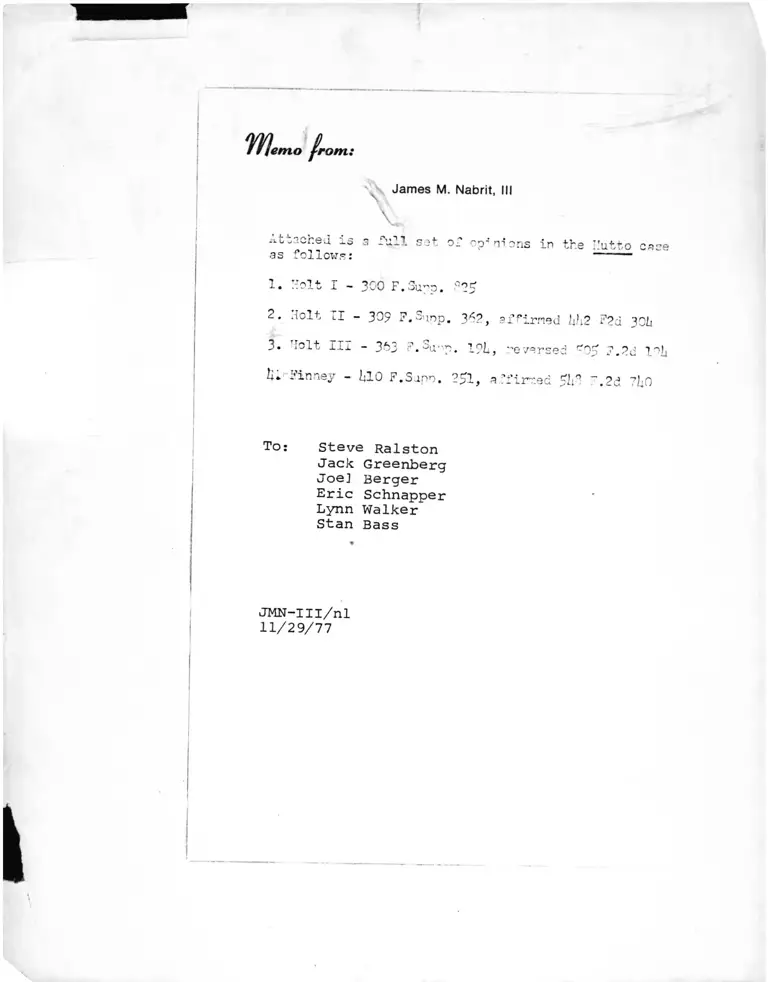

emo from

\ James M. Nabrit, III

\

At bached i s a f a l I s e t o f op-’ ni oris in the Mutt o caseas fo llo w s :

1 . Molt ~ri - 300 F . Supp. Oop

—

2 . Molt I I ■- 309 F.Supp . 3*2, ax r irn e d l>h2 F?d 3 Oh

3. Molt I I I - 3 63 F. Ou' vf . l ? h , rev e rse d POM FA2d IFli

Uir Finns y - 2dL0 F .Sapo. 251, a : f ir r .e d SU°- 7 .2d 71x0

To: Steve Ralston

Jack Greenberg Joe] Berger

Eric Schnapper Lynn Walker

Stan Bass

JMN-m/nl

11/2 9 /7 7

194 505 FEDERAL REPORTER, 2d SERIES

R obert FIN N E Y et al., A ppellants,

V.

A R K A N SA S HOARD OF CORRECTION

and Terrell Don H utto et a t ,

A ppellees.

Jam es C. ELLINGBURG, A ppellant,

v.

D ouglas NOLAN, Individually and as an

E m ployee of the C um m ins Unit, A rk

ansas D epartm ent of C orrection, Appel-

On*.

Jam es C. ELLINGBURG, A ppellant,

v.

K enneth G. TAYLOR. Individually and as

a Correctional Officer, A rkansas Board

of Correction, et a t . A ppellees.

Jam es C. ELLINGBURG, Appellant,

v.

Dan SEW ELL, Individually and as a Po

lice Captain, Texarkana, A rkansas,

Police D epartm ent, et a t , A ppellees.

Jam es C. ELLINGBURG, A ppellant,

v.

Terrell Don HUTTO, C om m issioner of

Correction, State of A rkansas, e t a t .

A ppellees.

N os. 73-1745, 74-1202, 74-1205, 71-1330.

71-1361), 74-1406, 74-1612 and

74-8102.

United States Court of Appeals,

Eighth Circuit.

Submitted June 10, 1974.

Decided Oct. 10, 1974.

Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc

Denied Nov. 4, 1974.

In cases in which distric t court had

retained continuing jurisdiction to su

pervise the improvement in state peni

tentiary system which had been found to

be unconstitutional, the District Court

for the Eastern District of Arkansas, ,J.

Smith Henley, Chief Judge, entered fu r

ther orders and determined tha t it was

no longer necessary to retain jurisdic

tion of the case and prisoners appealed.

In related cases, state penitentiary pris

oners’ petitions for individual relief

were denied by the District Court for

the ' Eastern District of Arkansas, .J.

Smith Henley, < 'hit-! Justice, Garnett

Thomas Eisele, and Oren Harris, JJ-,

and by the District Court for the West

ern District of Arkansas, Paul X Wil

liams. Chief Judge, and prisoners ap

pealed. The Court of Appeals, Lay, Cir

cuit Judge, held tha t the Arkansas peni

tentiary system was still unconstitution

a l ; directed tha t certain corrective ac

tion be taken with respect to inter alia,

housing, racial discrimination, physical

abuse, and rehabilitative programs; held

that findings of fact should have been

entered with respect to dismissal of

claims for individual relief on behalf of

two prisoners; that, other prisoners did

not state claims for individual relief;

and that the district court should have

retained continuing jurisdiction.

Affirmed in part, reversed in part

and remanded.

1. P risons 0^ 4

Although there is no such thing as

a perfect prison system, tha t fact does

not relieve prison officials of their duty

to make their system a constitutional

one in which the human dignity of each

individual inmate is respected. U.S.C.

A.Const. Amend. 8.

2. P risons C=»4, 12, 13

Continuing constitutional deficien

cies at state penitentiary, including

problems of housing, lack of medical

care, infliction of physical and mental

brutality and torture upon individual

prisoners, racial discrimination, abuses

of solitary confinement, continuing use

of trusty guards, abuse of mail regula

tions, a rb itrary work classifications, ar

bitrary disciplinary procedures, inade

quate distribution of food and clothing,

and total lack of rehabilitative programs

required retention of federal court’s ju

risdiction over the matter and the grant

ing of further relief to the prisoners.

U.S.C.A.Const. Amends. 8, 14; -12 U.S.

C.A. S 198.”,.

195FINNEY v. ARKANSAS HOARD OF CORRECTION

C ite n s no.-) ]\

3. Prisons C=17

If state choses to confine peniten

tiary inmates in barracks, some means

must be provided to protect those in

mates from assault and physical harm hv

other inmates. U.S.t '.A.Const. Amend. 8.

1. Prisons C=17

Fact that there was some compli

ance with previous court order which re

quired state prison officials to provide

for the safety of inmates was not suffi

cient and court should devise a program

to immediately eliminate the overcrowd

ing of prison barracks and to ensure the

safety of each inmate. U.S.C.A.Const.

Amend. 8.

5. Prisons 0=17

Lack of funds is not an acceptable

excuse for unconstitutional conditions of

incarceration. U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 8.

6. Prisons C=17

In case involving conditions of state

prison, district court should satisfy i t

self that no additional prisoners would

be confined at the prison if their con

finement would result in continued over

crowding and perpetuation of conditions

which failed to provide optimum safety

and sanitation for every inmate. U.S.

C.A.Const. Amend. 8.

7. Criminal Law C=1213

Transfer of juvenile offenders to

state prison constituted cruel and unusu

al punishment where unconstitutional

conditions existed at the state prison.

U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 8.

8. Reform atories C=9

State prison officials would be en

joined from transfe rr ing any juveniles

from reformatory to state prison until

constitutional infirmities within the

state prison were removed. U.S.C.A.

Const. Amend. 8.

9. Prisons C =i7

Lack of funds or facilities can not

justify an unconstitutional lack of com

petent medical care and treatment for

state prison inmates. U.S.C.A.Const.

Amend. 8.

!M 11U ( l 'J T I)

10. P risons C=17

Where state prison did not provide

basic emergency medical service, much

less any assurance of more complete

medical treatment when necessary, dis

trict court would be directed to hold ad

ditional hearings and to delineate, with

in specific terms and time limitations,

not only an overall long-range plan for

improvement of facilities a t the prison

but an immediate plan to update all

medical equipment at the facilities, to

ensure tha t every inmate in need of

medical attention would be seen by qual

ified physician when necessary. U.S.C.

A.Const. Amend. 14.

11. Prisons C=>4

State prison officials who had pre

viously been made aware of impropriety

of armed trusty system would be or

dered to, within a few months, complete

ly phase out its armed trusty system.

U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 14.

12. Crim inal Law 0=1213

Prison inmate working conditions,

under which inmates were, a t times,

forced to run to, from, and while a t work,

were required to race with other crews

in performance of the same type of work

and occasionally required to run in front

of moving vehicles or ridden horses and

under which a man who worked too

slowly or refused to work lost his enti

tlement to statutory good time and faced

solitary confinement, were unconstitu

tional. Ark.Stats. § 46-120 et seep; U.

S.C.A.Const. Amend. 8.

13. C onstitutional Law C=272

Administrative segregation, when

limited to three days’ duration pending

disciplinary action for rule infraction,

fell within correctional discretion and

did not violate due process. U.S.C.A.

Const. Amend. 14.

14. Crim inal Law C=1213

Minimal line separating cruel and

unusual punishment from conduct that

is not is the difference between depriv

ing a state prisoner of privileges he may

enjoy and depriving him of the basic nc-

j

*

1 :

j.

505 FEDERAL REPORTER, 2d SERIES196

cessities of human existence. U.S.C.A.

Const. Amend. 8.

15. l ’risons C=13

Prisoners placed in punitive solitary

confinement must not be deprived of ba

sic necessities including light, heat, ven

tilation, sanitation, clothing and a prop

er diet. U.S.C.A.Const. Amends. 8, 14.

16. P risons C=12

Where evidence indicated th a t disci

plinary committee of state prison often

acted in a summary manner displaying

an a ir of hostility towards the inmates

before it, district court properly ordered

that future disciplinary proceedings be

begun within three days of the occur

rence of the alleged offense, tha t all

hearings, to the extent possible, be held

between the hours of 6:00 a. m. and

6:00 p. m., and that they be reported in

such a manner tha t a reviewing authori

ty could determine what had transpired.

U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 14.

17. C onstitutional Law C=272

M inimum assurance of due process

requires tha t state prisoner subjected to

disciplinary proceedings be given w rit

ten notice of charges a t least 24 hours

prior to the hearing, be given a quali

fied right to call witnesses, and be given

a written statement of the factual basis

for the decision. U.S.C.A.Const. Amend.

14.

18. Prisons C=13

Officer who invokes prison discipli

nary measures should not.be allowed to

sit on the committee to review the m at

ter. U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 14.

10. Criminal Law 0=1213

Lack of rehabilitative programs at a

state prison could, in the face of other

conditions, be violative of the Eighth

Amendment. U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 8.

20. Prisons 0=1

Where state prisoners were faced

with constant th reat of physical and

mental abuse if their work or conduct

fell below arbitrary standards, where

they were left almost no time for self-

advancing activities or recreation, and

where rehabilitative programs were not

generally available, prison officials

would be required to submit to the couit

an overall program for treatment and

rehabilitation of the inmates a t the state

prison and a t state reformatory. U.S.

C.A.Const. Amend. 8 ; Ark.Stats. S 46-

116.

21. P risons C=4, 13

District court properly enjoined

prison officials from interfering with

Black Muslim religious practices, from

n# prisoners in maximum scout

rity, and from discriminating in such

areas as inmate classification, job as

signments, privileges, personal appear

ance, and disciplinary proceedings. U.

S.C.A.Const. Amend. 14.

22. Prisons 0=12

Inadequate resources cannot justify

failure of state prison system to hire

black employees and to give them posi

tions of responsibility. U.S.C.A.Const.

Amend. 14.

23. Prisons C=12

State prison system would be re

quired to adopt an affirmative action

program directed toward the elimination

of all forms of racial discrimination in

the hiring and promotion of prison per

sonnel. U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 14.

24. P risons C=1

If deemed necessary, inspection of

outgoing or incoming mail in the pies-

ence of state prison inmate is never

objectionable.

25. Convicts C=1

Prisoner does not shed his basic

constitutional rights a t the state prison

gates. U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 14.

26. C onstitutional Law C=82

State prisoners’ F i r s t Amendment

right should not be restricted by govern

mental interference unrelated to any le

gitimate governmental objective. U.S.

(!.A.Const. Amend. 1.

27. Prisons C=4

Neither state prison’s interest in in

vestigating persons who may wish to

visit a prisoner, nor the fact tha t some

\

I

!

I

f

l

i

i

I

t

<

c

<•'

oi

n

.T

v

fi

KINNEY v. ARKANSAS HOARD OF CORRECTION

< *ih* ;is .1o."

people do not wish to receive mail from

prisoners, nor allegation that some peo

ple, because of their criminal back

ground, have no right to correspond

with prisoners, was sufficient to justify

prison requirement that prisoners not

correspond with any persons who have

not previously given their consent to the

prison to be sent such correspondence.

U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 1.

28. C onstitutional Law C=82

Person does not forfeit his F irs t

Amendment rights simply because he ac

quires a had reputation and a state pris

oner does not lose the protection of the

First Amendment simply because those

with whom he wishes to communicate

are disreputable in the eyes of the

prison administrators. U.S.C.A.Const.

Amend. 1.

29. Federal Civil Procedure 0=2264

It was error for trial court, which

was hearing cases brought by state pris

oners who alleged unconstitutionality of

the treatment which they were receiving

in state prison, to fail to make specific

findings of fact with respect to individ

ual relief sought by the prisoners, even

though no requests lor such findings

were made. Fed.Rules Civ.Proc. rule

52(a), 28 U.S.C.A.

30. Courts 0=406.1 (7)

District court’s error in failing to

make findings of fact did not deprive

Court of Appeals of jurisdiction to re

view the record. Fed.Rules Civ.Proc.

rule 52(a), 28 U.S.C.A.

31. Courts 0=406.1(7)

An appellate court is in a position

to render a decision in the absence of

findings of fact by the lower court if

the record itself sufficiently informs the

court of the basis of the trial court’s de

cision on the material issue or if the

contentions raised on appeal do not turn

on findings of fact. Fed.Rules Civ.Proc-

rule 52(a), 28 U.S.C.A.

32. Courts 0=106.9(1)

Although Court of Appeals mav re

view a decision in the absence of written

findings of fact, it may not make such

197

r CM Mil ( l!)7l)

findings of fact on its own. Fed.Rules

Civ.Proc. rule 52(a), 28 U.S.C.A.

33. Courts C=400.6( 12)

Federal Civil Procedure C=22«l

It was prejudicial error for trial

court to fail to make findings of fact

with respect to denial of release to state

prison inmates who alleged tha t they

were wrongfully assaulted by prison

guards and suffered loss of good time

and that, in one case, inmate suffered

loss of good time because he was unable

to work due to foot ailment, as such

complaints stated claims upon which in

dividual relief could possibly be proper.

Fed.Rules Civ.Proc. rule 52(a), 28 U.S

C.A.

34. Civil R ights 0=13.12(6)

Although state prisoner is not enti

tled to have his record expunged or cor

rected simply because the full panoply of

due process procedures was not granted

to him, where the challenge is made that

good time was arbitrarily taken away

without any supporting evidence what

soever, the prisoner states a valid claim

for relief. U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 14;

42 U.S.C.A. $ 1983.

35. C ontem pt C=20

Where, although trial court deci

sions had indicated disapproval of armed

trusty program at state prison, where

there had been no specific order to dis

continue that program, prison officials

would not be held in contempt for fail

ing to phase out the system.

36. C ontem pt 0=21, 23

Before contempt may lie, the parties

must have actual knowledge of the order

and the order must be sufficiently spe

cific to be enforceable.

37. Federal Civil Procedure 0=664

It was e rror for district court to

refuse to file petition, in which state

prisoner sought damages from prison of

ficials because of an alleged conspiracy

to murder him, because the court

deemed petition frivolous on its face;

the complaint should have been filed

and, if the district court was still sa tis

fied that it was frivolous or failed to

j

i

i

505 FEDERAL REPORTER, 2d SERIES198

state a claim for federal relief, district

court should enter an appropriate judg

ment. 42 U.S.C.A. § 1982.

28. Civil R ights C=>12.2(1)

Physician's report which stated

that, although food service supervisor at

state prison had tubercular condition, he

was of no danger to others sustained

dismissal of prisoner's petition which

sought injunctive relief against the food

service commissioner. 42 U.S.C.A. §

1982.

2!). P risons 0 = 4

Fact that state prison inmate has

violated the criminal law, is generally

uneducated, and is in poor health, is no

justification for inhumane treatment

and brutality as segregation from socie

ty and loss of one’s liberty are the only

punishment the law allows. U.S.C.A.

Const. Amend. 8.

On Petition For Rehearing

to. Courts 0=100.1 (22)

Appellate court is not a fact-finding

court and must necessarily render its

decisions on the evidence and record be

fore it; it cannot receive new evidence.

41. Courts 0=100.9(15)

Trial court is the only court

equipped to test evidentiary compliance

with a court order and the only forum

in which to raise any allegations of con

tinuing deficiencies in that compliance.

12. Courts 0=100.9(15)

Where, over one and one-half years

af te r district court entered rulings deal

ing with disciplinary procedures in pris

ons and prison mailing regulations.

United States Supreme Court issues de

cisions on the subjects, it was for dis

trict court, on remand from Court of

Appeals, to judge, on the basis of the

Supreme Court decisions, whether the

disciplinary procedures and mailing reg

ulations were in compliance with those

‘ T l i r I lo iio i .il. li- K D W A R I ) .1. D E V I T T ,

(M iiiT J u d ^ c . I *11 il«*«i S ta te s l> is t r i( ‘l ( \ u i r l

fu r t lic I >ixl r id of M in nexo ta, s it t in g by des-

i;;nn t ion.

guidelines and it was not for the Court

of Appeals to make that determination.

48. Prisons C=4

Prison mailing regulation which has

no specificity is unconstitutional.

Philip E. Kaplan, Little Rock, Ark.,

for appellants in No. 72-1745.

0. II. Hargraves, Asst. Atty. Gen.,

Little Rock, Ark., for appellee in No.

72-1715.

Before LAY and HEANEY, Circuit

Judges, and DEVITT, District Judge.*

LAY. Circuit Judge.

In August 1972, the United States

District Court for the Eastern District

of Arkansas rendered its decision in this

class action brought by Arkansas prison

ers against the members of the Arkan

sas State Board of Correction, Terrell

Don Hutto, the Arkansas Commissioner

of Correction, and other prison officials.

The petitioners are inmates at the Cum

mins Prison Farm and the Tucker Inter

mediate Reformatory. The petitions

challenge the Arkansas prison system as

a constitutional system of correction.

Seven of the petitioners have appealed.**

They assert error in the district

court’s findings. We reverse in part

and remand the case to the district court

for fu r ther proceedings consistent with

this opinion.

This case had its origin in prior liti

gation. In 19(19 the district court gen

erally reviewed prison conditions in Ar

kansas and requested prison officials to

suggest possible remedial measures.

Holt v. Server, 200 F.Supp. 825 (E.D.

Ark.1909) (Unit 1). In 1970, a f te r ex

tensive hearings concerning Cummins

and Tucker, the d is t r ic tco u r t found that

conditions and practices at both institu

tions were such that confinement in ei

ther constituted cruel and unusual pun-

*+ T l i i s eo i i r t on i ts ow n m o t io n Inis eonsnli*

s ev en o t h e r a p p e a l s o f a n A rk a n s a s

i n m a te , . l am e s ( \ K l l in ^h n r ‘£. to lie eoitshl-

ereil w i th th e I'inm // ease .

isI

Fi-

St:

F

i

nix

ed

em.

t u t .

bo

y Oil

[

t<

ti

II

tl,

\v

al

go

to;

th

tii

209 i

T h is

ed t).

tion ,

sa la

th at

stitut

repori

ing th

Sarvei

1971).

The

report

tional

her oi

! 1971, i

! I. T h e

low in -

I T |l,

and

char:

work

and

th e i

nisei I

‘•onfii

Minin'

t a kin;

Sir'll Pi 1

Mren;

w ith

FINNKY v. ARKANSAS HOARD OF

1"ill* M S M:, l-'.LIil l!H I HIT It

COR RUCTION 199

ishmcnt, prohibited by the Kighih and

Fourteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution. Holt v. Sarver, :i0!)

F.Sttpp. 2(12 ( K.D.Aik.l‘>70) (Unit 11).

In Holt II, the district court recog

nized that not all of the reforms direct

ed could be accomplished overnight. It

emphasized that removal of the unconsti

tutional conditions and practices would

be required in a m atter of months, not

years. It stated:

[T]he obligation of the Respondents

to eliminate existing unconstitu-

tionalities does not depend upon what

the Legislature may do, or- upon what

the Governor may do, or, indeed, upon

what Respondents may actually be

able to accomplish. If Arkansas is

going to operate a Penitentiary Sys

tem, it is going to have to be a system

that is countenanced by the Constitu

tion of the United States.

209 F.Supp. a t 1185.

This court affirmed Holt I I . We direct

ed the district court to retain jurisdic

tion for a period no longer “ than neces

sary to provide reasonable assurance

that incarceration therein will not con

stitute cruel and inhuman punishment.

and to require an up-to-date

report on the progress made in eliminat

ing the constitutional violations. Holt v.

Sarver, 442 F.2d 204, 209 (8th Cir.

1971).

The district court received a progress

report on July 19, 1971. It held addi

tional hearings in November and Decem

ber of tha t year. On December 20,

1971, it ruled tha t “great progress’’ had

been made but tha t many problem areas

remained, so it retained jurisdiction. In

September of 1972 the district court ob

served that it was continuing to receive

“a constant stream of complaints” from

the inmates a t Cummins indicating that

the defendants were still violating the

court’s initial and supplemental decrees.1

The court ordered a fu rther evidentiary

hearing. Lengthy hearings were con

ducted in December, 1972, and January,

1972. More than 20 inmates testified.

Numerous defense witnesses also testi

fied. The court denied individual relief,

but granted petitioners a second supple

mental decree enjoining certain practices

of the Department of Correction. The

district court also determined that it

was no longer necessary to retain ju r is

diction of the case. It is from this de

cree tha t the petitioners have appealed.

Practice and Procedure Under S 1983

[1] We recognize tha t the district

court has received literally hundreds of

complaints from Cummins prisoners and

that until prison conditions change, the

steady stream of prisoner complaints

will continue. We arc mindful as well

of the administrative burden placed

upon the Arkansas prison officials who

must respond to individual grievances.

We further realize tha t the judicial

process often fails to provide needed re

lief promptly. Surely prisoners are also

aware of the slowness of the judicial

process, but until conditions change,

prisoners have no recourse but to take

their constitutional complaints to the

courts.-’ Bv now state correctional au-

I. The cour t noted ;it (lint t ime lici t tin* fol

lowing clmrgcs were being made :

IT | l in t inm ates a re being beaten, cursed,

and abused by employees having them in

charge; tha t inm ates assigned to field

work a re being forced to trot or mil to

and from work and to run tip and down

the rows while w ork in g ; th a t inm ates ac

cused of rule vio lat ions nee sentenced to

confinement in isolat ion in an a rb i t r a ry

m an n er ; tha t homosexual a s sau l t s are

taking p lace : t h a t inm ates have been a s

signed to tasks beyond th e i r physical

s t r en g th : th a t inm ates a re not provided

with p roper medical a t t e n t io n ; and tha t

they a re being re ta l ia ted ag a ins t or

th rea tened with re ta l ia t ion for a i r ing the ir

g rievances to the C ourt .

Record a t -1” ”>.

2. In C ruz v. Roto, -Kir. C .S . dill . !»2 S.Ct.

KITH. :;i R.Kd.l'd 9Ud (1079), the Suprem e

C o u r t faced a case in which a p r isoner 's

complaint had been dismissed w ithou t a

hear ing o r findings. T h e Court s a id :

Federa l cou r ts sit not to superv ise prisons

but to enforce the c o n s t i tu t iona l r igh ts of

all "persons ,” including prisoners. We

a re not unm indfu l th a t prison officials

m us t be accorded la t i tude in the adminis-

I

\

|

f

i

l

(

;

i

:I

I

200 .')().') FEDERAL REPORTER, 2d SERIES

thorities should have provided facilities

and programs consistent with constitu

tional standards. As the respondents

urge, there is no such thing -as a per

fect” prison system, hut this does not

relieve respondents of their duty to make

their system a constitutional one in

which the human dignity of each indi

vidual inmate is respected.-1

Substantive Review

We turn now to a consideration of the

district court’s decree and its supporting

memorandum opinion. It has been said

many times tha t the courts possess no

expertise in the conduct and manage

ment of correctional institutions. This

court has long recognized tha t it is only

in the exceptional case where the inter

nal administration of prisons justifies

judicial supervision. On the other hand,

courts need not he apologetic in requir

ing state officials to meet constitutional

standards in the operation of prisons.

The district court found tha t signifi

cant progress and improvements had

been made at both the Cummins and

Tucker institutions since Holt II. It

noted a “changing attitude and e ffo rt”

on the part of the Arkansas Legislature,

the present governor of Arkansas, his

predecessor, the Board of Correction, the

Commissioner and many employees of

the institutions. The court found that

those practices complained of in Holt II

were now not officially approved or

sanctioned. The district court did ac

knowledge that some constitutional defi

ciencies still existed and on that basis

granted the class certain additional in

junctive relief. However, the court

.................... prisnu affa ir* , ami tlisit prison-

it s iHMvssnrily a rc to appropriat**

roll's mi<l r rp i la t io n x . I »i 11 persons in

prison, like oilier individuals. Iiavr tin'

ri;dU to petit ion the 1 o n eriiinent for re

dress of gricviiiMT.s which, of course, in

cludes ’-access of p r isoners to the cour ts

for t h e purpose id* p resen t ing th e i r com

p la in ts ." Johnson v. Avery, .tlt-t I .^- Is.,.

is.1 I S !l S . t ’t. TIT. TIM. 'Jl U.Kd.'Jd T I S | :

K \ pa r te Hull, rtlli I ' .S . Alt;. AIM | til s . n .

f,|(l. ( II I . SA I,.I'M. 10-'!I|. See also

Younger v. (iil inore. Hit L .S . l-» 1MJ S M I-

found no need to retain jurisdiction of r:

the case. a.

[2] This court recognizes the diffi bi

cult issues the district court has passed .'lOD

upon since the commencement of this lit The

igation in IOCiM. We are nevertheless senci

compelled to find on the basis of the It ol

overall record tha t there exists a con sas .

tinuing failure by the correctional au mate

thorities to provide a constitutional and. provi

in some respects, even a humane environ assau

ment within the ir institutions. As will mates

be discussed, we find major constitution Comn

al deficiencies particularly a t Cummins !

j that l

in housing, lack of medical care, inflic 1 were

tion of physical and mental brutality 1' disrep

tint! to rture upon individual prisoners, i

i deploy

racial discrimination, abuses of solitary i

' In t

confinement, continuing use of trusty in 107

guards, abuse of mail regulations, arbi j a reali

t ra ry work classifications, a rb i tra ry dis ! heritor

ciplinary procedures, inadequate distri i Cor reel

bution of food and clothing, and total 1 strong!

lack of rehabilitative programs. We are j so-calle

therefore convinced that present prison overcro

conditions, now almost five years after howevet

Holt I, require the retention of federal i

i I'/c yea

jurisdiction and the granting of further 1

barrack

relief. i without

/ ’ h i/s ico l Fo cilit ics mately i

* in each

forth a detailed description of “ life in

the barracks” at the Cummins and Tuck

er Farm s:

A barracks is nothing more than a

large dormitory surrounded by bars;

the barracks are separated from each

other by wide hallways, and the com

plex of hallways is referred to as the

“yard.” At the present time the bar-

■JAO, ::<> I,.IM.'_M l l ' J I . nff'g t ii linore v.

I.yncli. AIM K.Supp. IMA tNUt'nl.).

/,/. ItlA I'.S. Ill Ml! S.t’t. at 1US1 : -we

illsn iiaincs v. Kci-ncr. -101 1 -S. ulM. MJ S.

Cl. AMI, .-.(I b.Kd.’Jd tio” ( IMT’J ).

3. The ndininist rat ivc hurden placed upon I In;

state by this never-ending stream ot S IM-S.J

iniu.’ite complaints should encourage it to

adopt more effective prisoner grievance pro

cedures. ('/. Inmate tlrievanco I'rocedures,

South Carolina .................. of Corrections

t imt:i>.

Mr. Hut

cannot

more tha

Some

undertak-

is under

facility,

rooms fo

° f the (i

The new

in the bar

imum see

bouse 8 0 t,

While II

sary to co

II, the r,

overcrowdi

4- In this r,

U is |||,.

that bill •

world jie

505 F. 2,1

racks house more than 100 men each

assigned without reward to anything

but rank and race.

:50!) K.Supp. at 276.

The court also described the total ab

sence of personal safety and security.

It observed that if the State of Arkan

sas chose to confine penitentiary in

mates in barracks, some means had to be

provided to protect those inmates from

assault and physical harm by other in

mates. At the trial of tha t case, then-

Commissioner Sarvcr “ frankly admitted

that the physical facilities a t both units

were inadequate and in a total state of

disrepair that could only be described as

deplorable.” 4-42 F.2d a t 208.

In the report submitted to' the court

in 1971, Commissioner Hutto expressed

a realization of the problem he had in

herited when he said: "The Board of

Correction and this Administration feel

. strongly that the greatest problem in the

so-called barracks is the problem of

overcrowding.” Despite this realization,

however, and the passage of more than

1V-. years, there is continued use of the

barracks and continued overcrowding

without adequate supervision. Approxi

mately 125 to 125 men are still confined

in each of the various barracks despite

Mr. Hutto’s concession that the barracks

cannot be successfully operated with

more than 60 to 80 inmates.

Some major improvements have been

undertaken. A minimum security unit

is under construction at the Cummins

facility. I t will provide individual

rooms for each of 248 inmates. Many

of the trusties will be housed there.

The new unit will reduce overcrowding

in the barracks. In addition a new max

imum security unit has been built to

house 80 to 90 inmates.

While these improvements were neces

sary to comply with the decree in Holt

II, the record indicates that serious

overcrowding has not been eliminated

}

4. In this regard t 'o m niiss ioner l i u t t o s t a le d :

I t is the experience of th is A d m in is t ra t ion

th a t only ad equa te supervis ion by free-

world personnel can ami will a s su re in-

t

u .

mates still occur.4 Moreover, relief will

apparently be short-lived, for the tes ti

mony reveals tha t inmate population in

creases each year.

[4-6] When a state confines a per

son by reason of a conviction of a crime,

the state must assume an obligation for

the safekeeping of that prisoner. One

means of protecting inmates from each

other is provision of adequate physical

facilities. Long-range plans provide no

satisfactory solution to those who are

assaulted and physically harmed today.

The fact tha t assaults and physical inju

ries have diminished does not demon

stra te compliance with the court’s decree

of four years ago. The fact that there

is some compliance is not good enough.

As long as barracks are used respond

ents must assure tha t they are not over

crowded and are safe and sanitary for

every inmate. There can be no excep

tions. Upon remand, the district court

shall meet with counsel and the respond

ents to devise a program to eliminate

immediately the overcrowding of the

barracks and to ensure the safety of

each inmate. Lack of funds is not an

acceptable excuse for unconstitutional

conditions of incarceration. An immedi

ate answer, if the state cannot otherwise

resolve the problem of overcrowding,

will be to transfer or release some in

mates. The district court shall also sa t

isfy itself tha t no additional prisoners

will be confined at the Cummins Prison

Farm if their confinement will result in

continued overcrowding and perpetua-

tion of conditions which fail to provide

optimum safety and sanitation for every

inmate.

[7 ,8 ] One fu r ther problem arises

from the overcrowding and inhumane

conditions a t Cummins. Youthful of

fenders confined at Tucker, the reforma

tory, have been transferred to Cummins,

the adult facility, because they posed

m ates personal securi ty ami sa fe ty w heth

e r w ork ing in the fields or elsewhere.

Record at

505 F. 2d—13»/a

202 .->05 FEDERAL REPORTER, 2d SERIES

!

i!

disciplinary problems for Tucker person

nel. At Cummins the youths are housed

either in solitary confinement for their

own protection or placed in the genet al

prison population. As .Judge Henley ob

serves, one could seriously question

which is worse. Apparently, some such

transfers have been completed quite

summarily. The petitioners state that

Tucker offers better conditions of con

finement with greater possibilities for

rehabilitation. They contend tha t any

transfer to Cummins, since it amounts

to a material change in their conditions

of confinement, must be accompanied by

procedures consistent with due piocess.

The trial court agreed and granted some

relief by requiring hearings on retrans

fer within a shorter period of time and

at more frequent intervals. We need

not pass on the due process issue for we

feel that the transfer of juvenile offend

ers to Cummins is cruel and unusual

punishment while unconstitutional condi

tions continue to exist there. We there

fore direct the district court to enjoin

any transfers from Tucker to Cummins

until the constitutional infirmities with

in the latter institution are removed.

Medical and Dental Facilities and Care

The respondents, through the testimo

ny of Mr. Lockhart and Commissioner

Hutto, agree tha t the medical facilities

within the Arkansas correctional system

are totally inadequate.

| <) ] At the time of the hearings, no

physician, dentist or psychiatrist was

employed by Cummins, although Mr.

Hutto testified that a full-time doctor

was being hired. A number of Cum

mins inmates are either mentally or

emotionally disturbed. These people aie,

as the district court found, “dangerous

to themselves and to their keepers and

other inmates and tend to keep other in

mates in states ol unrest and excite-

5. T h e A rk a n sa s Hoard of Correc tion sought

mil a com m it te r composed of seven physi-

cions, four pharmacologists , one hospital ail

m in i s t r a to r ami one psychologist to visit the

medical facili ties of the A rk an sas prison s y s

tem and m ake reeomtnendations. 'I 'heir ce

ment.” Holt v. Hutto, 3G3 F.Supp. 104,

200 ( E.D.Ark. 1973). In addition the

district court found that many inmates

have serious physical ailments which

render confinement in the ordinary pe

nal institution unbearable for them and,

in the case of contagious diseases, dan

gerous for others. The district court

found that deficiencies have existed and

continue to exist but tha t ‘ the Depait-

mont has done the best that it could in

the area of medical services with the re

sources at its command.” 3G3 F.Supp.

at 200. We find the problem to be much_

more complex and serious than this, and

assuming the deficiencies are of a con

stitutional nature, we again cannot

agree tha t lack of funds or facilities jus

tify lack of competent medical care.

Subsequent to the decision in Holt II,

Dr. T. II. Wortham, a member of the

Board of Correction, requested the Ar

kansas Department of Health to evaluate

the medical tacilities of the Depaitmcnt

of Correction. Its report, which was of

fered in evidence, is a comprehensive

and detailed study encompassing the

whole health delivery system, including

the future workload, the facility needs

and recommended action. The report

s tates:

One basic assumption is made upon

which this study is built. I t is this:

the primary purpose of the correction

system is to rehabilitate inmates so

tha t they become productive citizens

and a basic level of medical care is a

necessary part ot the rehabilitation

process. This assumption includes the

notion that a poor state of physical or

psychological health will detract from

rehabilitation efforts. Also included

in this assumption is the concept that

medical facilities, acceptable in quality

and quantity, are a necessary part or

[ .sic 1 providing this level of medical

care/'

port para l le ls llial of tin- D ep a r tm en t of

H eal th . They s ta le d :

All tnenihers of the visiting team consider

that all inm ates have a hash- right to med

ical. dental and psychological diagnosis,

study and t rea tm en t . We also l e d that it

is hash- that rchah i l i ta t ion is the goal of

r I i\ A rJ i v.

< III- JIN .14).]

The report itself illuminates a total dcfi

AKI\AiSSAS BOARD OF CORRECTION

('ill- ii-. "Kir, I'.LM |>i| ( IJI7I, 203

ciency in both manpower and equipment

resources. We highlight only some of

those deficiencies found to exist a t Cum

mins :

1. Lack of sufficient personnel to

s taff the facility on a 21-hour basis

with free world help. Along with the

added staffing, salary increases arc

necessary to retain those now cm-

' ployed.

2. The equipment is completely inad

equate to continue present operations

at an acceptable level.

•3. There is a tremendous need for

more professional assistance. The

lack of a physician at more frequent

intervals places an unreasonable bur

den upon the present employees since

they are called upon to do work which

they are not qualified to perform.

4. Better transportation is needed if

the present operation is maintained.

There is an immediate need for an

ambulance. The time and effort in

volved in transfers to Little Rock is

very time consuming for the already

overworked staff. In addition, it has

resulted in 4 escapes during the peri

od studied. .

There is no registered professional

nursing supervision at either of these

medical facilities. Also, data gathered

strongly suggests that in some cases a

physician is not responsible for some

of the medical care which is rendered.

Therefore, even if only temporary

medical care was offered at these fa

cilities, the standards for licensure as

an infirmary would not be met.

Some definitive, non-temporary,

medical care is provided at Cummins.

The length ot stay of admitted pa-

prisons r a th e r Ilian punishm ent . \ \Y be

lieve tha t a fact of basic wholeness of the

person is an interest in his physical self

‘""1 this in te res t should he s t im ula ted . 6

6. At the T u ck e r In te rm ed ia te Reform atory

the report relates in p a r t a s follows:

-Medications a r e ob ta ined from the C um

mins un i t as needed. T h e re is a p p a re n t ly

tients indicates that the medical unit

could be better defined as a hospital.

If the Cummins unit is, in fact, a hos

pital and not ;m infirmary, deficien

cies exist in all major areas of the li

censure regulations.

Hospital requirements for physi

cians’ care, nursing, medical records,

patient accommodations, diagnostic

and treatment service, dietary serv

ices, and physical facility are all sig

nificantly lacking.

In fact, some patients appear to not

be under the care of a physician, there

is no professional nursing, required

medical records are only partially

maintained, basic laboratory and x-ray

services are only partially available,

no professional dietary service is pro

vided, and a great many facility and

enviionmental standards are not cur

rently being met.

The Committee summarized:

Cuirent facilities do not meet state

licensure standards.

Diagnosis and treatment of emer

gency and acute illness is not ade

quately provided for due to a lack of

facilities, equipment, and only part-

time availability of professional medi

cal staff.

Efforts of the Rehabilitative Serv

ices unit arc not fully coordinated

with efforts of the other medical dis

ciplines.

Convalescent care and chronic ill

ness treatment is provided in State

Health facilities located in Little Rock

and Booneville. A security problem is

related.

Construction of adequate medical

care facilities is justified on the basis

of workload. 8

no resource iivtiiltihlo for s teri le supplies

for t rea tm en t of injuries .

An in terv iew w ith the T u c k e r medic dis

closed the following se rious problems :

1. Luck - of personnel a t the i n f i r m a r y :

there p resently is no o th e r posit ion a u th o

rized and the sa la ry level is to ta l ly made-

qunte lo a t f r a e t qualified personnel.

X - ray facili ties a r e needed.

r,0.'> FEDERAL REPORTER, 2d SERIES204

The record additionally shows that

there are no dentists a t Cummins 0 1

Tucker. When a dentist does visit, no

restorative work is done. Although the

evidence indicates tha t prisoners who

need major dental work, such as extrac

tions, are taken into the dentist a t Pine

Bluff, the record likewise shows that

none of the 12<)0 inmates a t Cummins

had made such a visit for a period of at

least eight months prior to the district

court hearing.

| 10] The long-range studies conduct

ed by the Board of Correction were

made over two years ago. Mr. Hutto

testified tha t a complete medical facility

was to be built in the future. There is

no question that Commissioner Hutto

and the Board of Correction feel tha t

they “ mnst have a full service medical

and dental program, even to the point of

restorative medical and dental problems.”

Nevertheless, on the present record,

we are convinced that they have

achieved little more than a study and a

hope to improve the present inadequate

care. This court fully realizes, as did

the district court, tha t this is a difficult

problem for the Board of Correction and

prison officials. In the meantime, how

ever, 1200 inmates are continuously de

nied proper medical and dental care, and

individuals with contagious diseases, as

well as some who are mentally and emo

tionally ill, are a t large in the general

prison population. There is not even ba

sic emergency service, much less any as

surance. of more complete medical t rea t

ment when necessary. We think it in

cumbent upon the court to hold addition

al hearings and to delineate within spe

cific terms and time limitations not only

an overall long-range plan but an imme

diate plan to update all medical equip

ment a t all facilities, ensuring tha t ev

ery inmate in need of medical attention

will be seen by a qualified physician

when necessary. We refer the court to

the comprehensive decree of Chief Judge

'I'll!' ile n (iiI <-<|iii|>in<*iit is n n lii|u n li'< l m ill

in l ic n l of

I. Ki|ui]iini-nt fur t r e a t i n g lacera t ions is

en t i re ly inai lequate.

Johnson, in Newman v. Alabama, .549 h .

Supp. 278, 28(3-288 (M.D.Ala.1972), as a

guide.

Inmate Guards

[11| Perhaps the most offensive

practice in the Arkansas correctional

system at the time of Holt 11 was the

use of armed trusties as prison guaids.

As recently as 19G9, fully 90 percent of

the security force of the Arkansas prison

system consisted of such inmate guards.

They virtually ran the prison. They sold

desirable jobs to other prisoners and

trafficked in food, liquor and drugs.

There was no way to protect prisoners

from assaults if the trusty guards per

mitted them. Several months af te r the

district court ordered abolition ot the

trusty system in Holt 11, Commissioner

Hutto reported:

T h e Trusty System of armed guards

has not in fact been dismantled at ei

ther Cummins or Tucker. The efforts

which have been made have succeeded

reasonably well in removing much of

the power formerly held by the trus

ties and placing this power into the

hands of civilian personnel. Armed

Trusties are being used on the towers

a t both Tucker and Cummins and arc

used to guard outside work forces.

This is done, however, under the di

rect. supervision of a civilian supervis

or, who is present at all times with

the work forces. Trusties have been

removed completely from any respon

sibility or authority regarding inmate

job assignments, promotions and de

motions, and all disciplinary matters

are handled by free world personnel.

Even in institutions where there is a

large number of experienced em

ployees there is the constant dangci

tha t “ trusted" inmates exercise subtle

influences on s ta ff in the area of job

assignments and discipline. In a sys

tem such as this where there is still

some shortage of employed personnel

r,. Iailioniliirv i-i|uilitiit*iit is i m i l t o

IMTforin mul im* Irs ls.

205HNNEY v. ARKANSAS HOARD OF CORRECTION

< It «• Us o<)», I

and many of these have little or no ex

perience, this problem is more acute

and, realistically, one must admit that

this is a daily problem with which we

have to deal. ( Emphasis added).

The record is deficient in updating

this report. However, the inmate com

plaints make it appear tha t the Commis

sioner’s 1971 report represents the s itu

ation as of January 1973. Apparently

some use of t rusty guards continues at

this time. This court affirmed the dis

trict court’s opinion in Holt II. with em

phasis on the admonition tha t trusty

guards were not to perform prison jobs

which ordinarily would be performed by

free world personnel.

In Holt I I the district court found the

use of field guards objectionable. I t ob

served :

The system of field guards and the

system of using trusty long line riders

and inmate pushers go hand in hand,

and the combination of the two is one

of the things tha t makes the field

guard system so dangerous to rankers.

Field guards are much less likely to

fire on a ranker or on a group of

rankers in the immediate presence of

a civilian long line supervisor than

they are in a situation where the

rankers are actually being worked by

other inmates. I t appears to the

Court that the answer, however unpa

latable it may be. is to eliminate the

positions of long line rider and inmate

pusher and to put each long line under

the immediate charge of one or more

free world people.

309 F.Supp. a t 384.

Although the district court in Holt II

found the use of t rus ty guards in the

towers less objectionable, tha t did not

mean that it was to be continued.

We feel the time for dismantling the

entire system has long passed. The dis-

7. Tim court s t a t e d :

Those employees have in general been re

cruited lo c a l ly ; they a rc poorly paid by

modern s t a n d a rd s ; they have bad l i t t le

t r a in ing or exper ience ; m any of them are

uncultured and poorly educated ; some of

Cd 101 ( 1071)

tr ic t court shall order that it be com

pletely phased out within a few months.

I ’ln/nicul and Alrntal lirultrlil//

The district court supplemented its

decree of December 80, 1971, by staling:

(g) Without limiting the generality

of the term “cruel and unusual pun

ishment” appearing in Paragraph -1 of

the Court’s Supplemental Decree of

December 30, 1971, tha t term is now

defined as including the infliction

upon any inmate of the Department of

Correction of any unreasonable or un

necessary force in any form, the as

signing of any inmate to tasks incon

sistent with his medical classification,

the use of any punishment which

amounts to torture, the forcing of any

inmate to run to or from work, or

while a t work, or in front of any mov

ing vehicle or animal, and the inflic

tion of any punishment not authorized

by the Department’s rules and regula

tions.

In its memorandum order the district

court pointed out that Commissioner

Hutto, Superintendent Lockhart and the

other high-level officers were qualified

for their iobs and were attempting to

perform well. However, the court ex

pressed concern over the lower echelon

of prison personnel.7 The court’s find

ings and discussion concerning habitual

harassment of inmates bv prison per

sonnel, through physical and mental

abuse, covers several pages of its opin

ion. As the court indicates, the con

tinuing presence of instances of brutality

is

. particularly significant here

in view of the long history of b ru

tality to inmates of both Cummins

and Tucker tha t was practiced for

so many years and that has been

described in detail in earlier opinions

tliom a re qu i te young. perhaps too young

to lie i n p o s i t i o n of a u th o r i ty over con

v ic ts ; some of them are quick tempered.

If one adjective is to lie used to describe

tbeni, ir would be "unpro fess iona l .”

8<>3 F -Supp . a t 1101.

206

505 FEDERAL REPORTER, 2d SERIES

of this Court and the Court of Ap

peals.

1563 F.Supp. a t 212.

U nquestionably the D epartm ent of

C orrection has adopted a po c.

dem ning all form s o f ^ u s e o f . n m a L .

C om m issioner H utto issued h is pohc>

m em oranda p roh ib itin g P yh* ‘ c

o f in m ates” in D ecem ber o f 1971. N

crth e less, there is evidence as ot U m

ary 1973 th a t excess ive force, v e ib a l

abuse and variou s form s o f torture an

inhum ane punishm ent continue.

The district court demonstrated a

keen perception and understanding

how conflicts arise between prison I>e -

sonnel and inmates. The court points

out tha t the overall working conditions

and prison environment provide a fu t i le

J r o l l to.- continued . h * ; and ».oU-

„ t earlier deereos. Altho»«h U»

distric t court did not find the prwoi

working conditions so harsh cons i

tute cruel and unusual punishment in

S l a v e s . it ol,nerved th a t the tnn.aten

on the “hoe squads” are m p m e d to

work long hours under constant I

ding;, that a t times inmates are a . -

signed to work at tasks beyond then

strength or medical ability; and that

older or weaker inmates are requned to

keep up with the younger inmates a t ai-

duous tasks under th rea t of disciplinary

proceedings. The court found evidence

tha t the inmates arc a t times still foioc

to run to and from work or while at

work, and that some crews arc re q u u u

to race with another crew in the P

formance of the same type- oi

The record indicates tha t the in * •

have been required to run in front of

moving vehicles or ridden horses. I >-

S l y , even af te r Holt II, a young boy

named Willie Stewart was given a w

dai, sentence. On tha t day he was put

through all forms of mental am Ph>'* C;

torture, ending when the guards shot at

his feet and inadvertently lolled lun .

This “treatment,” according to Mr H u t

to, has stopped. Unfortunately it took

the life of a young prisoner, l a th o <

tr, n c c n m i ) l S I l 1L.

In addition to physical abuse the

record reveals tha t the prison personnel

a t all levels employ profane, threatening,

abusive and vulgar language, toge the

wUh racial slurs, epithets, and sexual

and seatalogical terms when addressing

inmates. Conduct prohibited by official

prison rules is freely engaged in.

i p i i We have discussed previously

the departmental obligation to protect

j l a to » M >»«* ^ “ d

tal abuse by the correctional s taff and

other inmates. The continued infliction

of physical abuse, as well as mental dis

tress degradation, and humiliation by

correctional authorities demonstrate

that mere words are no solution. Sue

unlawful conduct by correctional peison-

1 is of major significance leading to

this court’s finding that the present

correctional system in Arkansas is stih

unconstitutional. For this reason. £

well as thus.- stated elsewhere, the d.s

tr ic t court shall retain jurisdiction and

take if it deems advisable, additional e -

idence on those conditions of confine-

• xnent. hiring policies, working conditions

and disciplinary measures which must

be changed in order to provide a con

tinuing prophylaxsis against such c u d

and inhumane treatment.

This court finds that the piesent

working conditions are unconstitutional

and must be radically changed If a

man works too slowly or refuses to work

he not only loses his entitlement to s ta t

utory good time (Ark.Stat.Ann. s

120 et seq. (1973)), but faces solitaiy

jonfinom oit * wdl.

echelon personnel are given th t p0* \

impose additional mental punishment y

threatening solitary confinement to

those who do not work to then s, - ‘

tion. Arbitrary power is thus placed

the hands of persons obviously lacking

the discretion to exercise it wisely. Ab

sent evidence of qualified supervisors

for the work crews, a possible solution is

t() deprive the line guards of this power.

The district court should review these

conditions bearing in mind this co u i ts

* U ̂ nAiivi

FINNEY v. ARKANSAS BOARD OF CORRECTION

c i t e iin non tutu m i ( 207

and treatment for the prison population

and the resultant physical and mental

abuse.

Maximum Seen r it ;/

One of the principal grievances in

both Holt I and Holt II concerned the

intolerable conditions in the old maxi

mum security units at Cummins. Since

Holt II, a pew facility has been con

structed alleviating to a great extent

problems of sanitation and overcrowd

ing- Some problems remain, however.

One such problem is the practice of plac

ing inmates awaiting disciplinary hear

ings in punitive, solitary confinement.

This court has previously held that soli

tary confinement is not, per se, cruel

and unusual punishment.* Burns v.

Swenson, 430 F.2d 771. 777-778 (8th

Cir. 1970) cert, denied, 404 U.S. 1002,

02 S.Ct. 743, 30 L.Ed.2d 751 (1972).

Under certain circumstances, such con

finement can violate the Eighth Amend

ment. This fact was demonstrated in

the original Holt decisions.

[13] Complaint is made by prisoners

who are placed in isolation for “adminis

trative segregation,” pending discipli

nary action for rule infraction. Judge

Henley limited this segregation to three

days’ duration. 363 F.Supp. a t 207.

It e find such administrative segregation

as limited by the trial court to fall with

in correctional discretion and not to vio

late due process. We assume, of course,

8. At the same time we cannot help lair ob

serve th a t a recent s tu d y conducted h.v the

-National Advisory Commission on Crim inal

Just ice led to the following observation by

that g ro u p :

The Commission recognizes th a t the field

of corrections can n o t ye t be persuaded to

give up the p rac t ice of so l i ta ry confine

ment as a d isc ip l inary measure , ftut the

t oimnission wishes to record its view th a t

the practice is inhum ane and in the long

run bruta l izes those who impose it as it

brutalizes those upon whom it is imposed.

Report on Corrections. T h e N at ional Advi

sory Committee on C r im ina l Ju s t ic e yttand-

ards and Coals, p. 32. .

9- Nee, c.rj.. L an d m an v. Roys ter , 333 F .S upp .

b-1 ( E. L>.\ a.111 < 1), where the co u r t consid

ered a bread and w a te r diet :

tha t if disciplinary action is not taken

against the inmate for lack of evidence,

full privileges will be restored and tiny

good time he would have earned ir the

opportunity had been available will be

credited to him.

[14, 15] In the punitive wing, we

note the prisoners are denied the regular

prison diet. “Grue” is the term applied

to the tasteless, unappetizing paste-like

food which is served to prisoners in soli

tary confinement as a form of further

punishment. In Holt /, the district

court found tha t grue constituted a nu

tritionally sufficient diet. 300 F.Supp.

a t 832. The procedure followed by pris

on authorities when an inmate is placed

on grue, however, makes tha t conclusion

dubious. The prisoner receives one full

meal a t least every three days and six

consecutive full meals every 14 days. At

the end of tha t period, he is given a thor

ough physical examination. I f medical

reasons dictate a regular diet then it is

ordered. Otherwise the prisoner is con

tinued on this punitive treatment. This,

in itself, indicates an awareness of pos

sible dietary insufficiencies. There ex

ists a fundamental difference between

depriving a prisoner of privileges he

may enjoy and depriving him of the ba

sic necessities of human existence.9 We

think this is the minimal line separating

cruel and unusual punishment from con

duct tha t is not. On remand, the dis

tr ic t court’s decree should be amended to

T h e prac t ice is therefore both generally

d isapproved and obsolescent even w ith in

th is penal system. I t is not seriously de

fended as essential to securi ty . It

a m o u n ts therefore to a n unnecessa ry in

f l ic tion of pain . F u r th e rm o re , ns a tech

n ique designed to b reak a m an 's sp i r i t not

j u s t by denial of physical com forts but of

necessi ties , to the end th a t his powers of

resis tance d iminish, tin- bread and w a te r

d ie t is inconsis tent with c u r re n t m inimum

s ta n d a rd s of respect for h um an dignity.

T h e Court has no d if f icu lty in de te rm in ing

t h a t it is a violation of the eighth am end

ment. J a ckson v. l i ishop, -101 F.2d ."71

(Nth Cir. 1 lifts) ; W right v. M eM ann, 321

F .S u p p . 127 (X .D.N.Y. 111701.

hi. a t (117.

I

t

It

I

i !

i \i ■!

208 505 FEDERAL REPORTER, 2d SERIES

ensure tha t prisoners placed in punitive

solitary confinement are not deprived of

basic necessities including light, heat,

ventilation, sanitation, clothing and a

proper diet.

Disciplinary Process

The district court reviewed the disci

plinary procedures employed in the A r

kansas prison system and found them

lacking in several particulars of due

process. It granted a measure of in

junctive relief. We agree with the re

lief granted, but in view of the Supreme

Court’s subsequent decision in Wolff v.

McDonnell. 418 U.S. 539, 94 S.Ct. 2968,

41 L.Ed.2d 925 (1974), we feel more is

required.

[1 6 1 The district court found that

the disciplinary committee often acted in

a summary manner displaying a decided

a ir of hostility toward the inmates be

fore it. Accordingly, the court ordered

that future disciplinary proceedings

must be begun within three days of the

occurrence of the alleged offense. It

also ordered tha t all hearings, to the ex

tent possible, be held between the hours

of 6:00 a. m. and 6:00 p. m., and that

they be reported in such a manner that

a reviewing authority could determine

what had transpired. 368 F.Supp. at

207-208.

[1 7 1 The petitioners on appeal ob

ject to the following aspects of the disci

plinary procedure now in force: I I ) the

possibility tha t the same person who

wrote the disciplinary may sit in judg

ment. (2) the absence of a r ight of con

frontation, (3) lack of sufficient prior

notice of charges, and (4) the lack of

any duty upon the “court” to explain the

basis for the result reached. In Mc

Donnell, the Court held tha t prison dis

ciplinary proceedings must contain the

following safeguards: (A) written no

tice of charges a t least 24 hours prior to

the hearing; (B) a qualified right to

10. M c lh m n c ll m akes H e a r tlmt prison a u

thor i t ies may rejeet the p r isoner ’s request

to eall witnesses where securi ty problems

call witnesses,lH and (C) a written state

ment by the committee of the factual ba

sis for its decision. These procedures

constitute the minimum assurance of

due process.

[181 There is evidence tha t on occa

sion the same officer who invokes disci

plinary measures sits on the committee

to review the matter. This practice has

been unanimously condemned by those

courts which have considered it. United

States ex rel. Miller v. Twomey, 479 F.

2d 701, 715-716 (7th Cir. 1973); Sands

v. Wainwright, 357 F.Supp. 1062, 1084-

1085 (M.D.Fla.), vacated, 491 F.2d 417

(5th t ’ir. 1972); United States ex rel.

Neal v. Wolfe, 346 F.Supp. 569, 574-575 J

(E .D .Pa.1972): Landman v. Royster,

333 F.Supp. 621, 653 ( E.D.V a.1971);

Clutchettc v. Procunier, 328 F.Supp. |

767, 784 (N.D.Cal.1971). As stated in

Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471, 92

S.Ct. 2593, 33 L.Ed.2d 484 (1972), with

reference to parole revocations: “The

officer directly involved in making rec

ommendations cannot always have com

plete objectivity in evaluating them.”

Id. at 486, 92 S.Ct. a t 2602. The dis

tric t court should bar the charging offi

cer from sitting in judgment on his.owp

complaint in disciplinary proceedings.

Rehabilitation

In Jackson v. Indiana, 406 U.S. 715,

738, 92 S.Ct. 1845, 32 L.Ed.2d 435

(1972), Mr. Justice Blackmun stated:

“At the least, due process requires that

the nature and duration of commitment

bear some reasonable relation to the

purpose for which the individual is com

mitted.” Id. a t 7.38, 92 S.Ct. a t 1858.

The Supreme Court has recognized reha

bilitation as one of the ends of correc- >

tional confinement. ' See, c. </., Procunier

v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 896, 412-413, 94

S.Ct. 1800, 1811, 40 L.Ed.2d 224 (1974).

Arkansas statutes as well stipulate that

efforts should be directed toward the re

habilitation of persons committed to the

f

might arise. It is xuggexteil when this oe-

i-n rs l ic it n ff ie in lx m a k e e le a r I lie m in im fur

l im n in g the reiinesl . t i l S . t ’t. at Ltnso.

FINNEY v. ARKANSAS HOARD O F CORRECTION

<'it** :»> K.1M l!»» ( li»7n 209

stitutional care of the Department of

Correction.11

[19, 201 In Holt. II, the district court

said that the lack of rehaldlitative pro

grams could, in tin* face of “other con

ditions,” he violative of the Eighth

Amendment. - With this we agree.

Furthermore. we find that those

other conditions persist. Convicts in the

Arkansas system • are forced to labor

long hours under arduous conditions.

They are faced with constant threats of

physical and mental abuse if their work

or conduct falls below often arbitrary

standards. They are left almost no time

for self-advancing activities or recrea

tion, and the testimony of prison offi

cials indicates tha t even if time were

available, rehabilitative programs are

generally not available. The Commis

sioner has testified concerning the build

ing' trades apprenticeship program and

ttfe increasing opportunity for basic

schooling. However, these programs at

Cummins are still very limited, accom

modating a relatively small number of

inmates. We thus deem it necessary

that the respondents be required to sub

mit to the court an overall program for

treatment and rehabilitation of the in

mates at both Cummins and Tucker.

Racial Discrimination

[21] When Holt I I was before the

district court in 15)70, racial discrimina

tion was a serious problem within all the

institutions operated by the Arkansas

Board of Correction. Living facilities

were se.v» egated at that time and there

was convincing evidence of racial dis

crimination in other areas of prison life

from job assignments to class status.

The court ordered immediate elimination

of all racial discrimination. Hy the time

the district court heard this case, there

had been a marked improvement in this

regard. Living facilities, with the ex

ception of the punitive segregation wing

at Cummins, were integrated. Nonethe

less, the court found that discrimination

still pervaded other facets of prison life.

Accordingly, the district court again en

joined racial discrimination in several

particulars, including: (1) interference

with Black Muslim religious practices:

(2) segregation of prisoners in maxi

mum security, and C!) discrimination in

such areas as inmate classification, job

assignments, privileges, personal appear

ance, disciplinary proceedings and pun

ishments. With this we agree, but once

again we find that the court’s decree

stops short of its intended goal.

The court specifically found that the

more intangible forms of racial discrimi

nation could not be eliminated until the

Arkansas Department of Correction was

integrated. This is especially true in

the areas of job classification and disci

plinary proceedings, where preconceived

ideas and often unconscious prejudices

may seriously affect an inmate’s life.

H. A rk .S la t .A m i. 5 -Kl-lHi (1!>7::> :

Classif ication anil t r e a tm e n t program s.—-

Persons committed to ' the in s t i tu t iona l

care of the D epar tm en t shall he dealt with

humanely with e t lo r ts directed to the ir re

habilitation. F o r these purposes, the De

par tm ent m ay es tablish p rog ram s of c las

sif ication and diagnosis , education , ease

work, counselling and p sych ia tr ic therapy,

vocational t r a in in g and guidance work,

and l ib ra ry and rel igious se rv ices ; o ther

rehabilita tion p rogram s o r services as mav

he ind ica ted ; and shall in s t i tu te priH-e-

dures for the s tudy and c lassif ica t ion of

inm ates ; provided, however , th a t the

Commissioner shall, with the approval of

the Hoard, establish rules and regulations

for the assignm ent of inm ates to the v a r i

ous programs, services and work activi t ies

505 F. 2d—11

Id' the D epar tm en t , and inm ates in the in

s t i tu t io n s of the D epar tm en t may p a r t i c i

pa te in and benefit from the vocational,

educational an d rehab i l i ta t ion services of

the respective in s t i tu t io n s solely with in

the rules and regu la t ions of the D e p a r t

m en t as de term ined by the Commissioner,

subject to appeal and review by the Hoard

o r a des ignated review board in acco rd

ance with procedures that shall lie e s t a b

lished therefor by the Hoard. Women in

m ates committed to the D epa r tm en t shall

he. housed separa te ly from men. W ork

ass ignm ents b.v women inm ates shall be

made by the Commissioner u n d e r rules

and regu la t ions p romulgated by the Hoard,

and an y con tac t of women pr isoners with

male inm ates shall be u nde r d irec t s u p e r

vision of the Hoard. I

j

FINNEY v. ARKANSAS BOARD OK CORRECTION 911

( ’ill* IIS I'.

to tlio suppression of expression ;m<i toe

limitations imposed were no greater

than neeessar.v to aeeomplisti that objec

tive. If deemed necessary inspection of

outgoing or incoming mail in the pres

ence of an inmate is never objectionable.

However, any kind of censorship regula

tions carry a heavy burden. The dis

trict court should review the mail regu

lations under the standards set out in

Martinez. See 94 S.Ct. a t 1811 et seep

[25, 261 The petitioners’ second com

plaint concerns the mailing list require

ment, whereby a prisoner may not corre

spond with any person who has not pre

viously consented. This procedure a f

fects potential correspondents whenever

prison officials refuse permission to in

clude a name on the list. However, it

more directly places prior restraint on a

prisoner’s freedom to correspond with

whomever he chooses. I t is now' well

settled that a prisoner does not shed his

basic constitutional rights a t the prison

gate. Cruz v. Beto, 405 U.S. till), 92 S.

Ct. 1079, 81 L.Ed.2d 268 (1972);

Haines v. Kernel-, 404 U.S. 519, 92 S.Ct.

594, 30 L.Ed.2d 142 (1972); Wilwording

v. Swenson, 404 U.S. 249, 92 S.Ct. 407,

30 L.Ed.2d 418 (1971) ; Younger v. Gil

more, 404 U.S. 15, 92 S.Ct. 250, 30 L.

Ed.2d 142 (1971); Lee v. Washington,

390 U.S. 333, 88 S.Ct. 994, 19 L.Ed.2d

1212 (19681; Cooper v. Pate. 378 U.S.

546, 84 S.Ct. 1733, 12 L.Ed.2d 1080

(1964); Screws v. United States, 325

U.S. 91, 65 S.Ct. 1031, 89 L.Ed. 1495

(1945); Ex Parte Hull, 312 U.S. 546, 61

S.Ct. 640, 85 L.Ed. 1034 (1941). While

it has been recognized that these rights

and immunities do not always assume

the same form in prison tha t they do in

free society, Wolff v. McDonnell, 418

U.S. 539, 94 S.Ct. 2963, 2975, 41 L.Ed.2d

935 (1974), they are, nonetheless, pres

ent. We need go no fu rther to recognize

that a prisoner’s F irs t Amendment right

should not be restricted by governmental

interference unrelated to any legitimate

governmental objective.

[27] At trial, prison officials of

fered three justifications for the ap-

LM l!ll (1!>7I

proved mailing list procedure. First,

they urge tha t those to whom a prisoner

writes may wish to visit him anil the

mailing list procedure gives them an op

portunity to investigate potential visi

tors beforehand to determine whether a

visit should be permitted. Second, they

contend that some people, because of

their criminal background, have no right

to correspond with prisoners. Finally,

they state that some people do not wish

to receive mail from prisoners. Apply

ing the Martinez test, we find these jus

tifications wanting.

I 28 | If prison officials have a valid

interest in investigating potential visi

tors, obviously that interest may be pro

tected by less intrusive means, such as

the submission of a visitors’ list. We

are not persuaded tha t all correspond

ents need to be investigated on the

chance tha t some may visit. It is equal

ly unavailing to argue that some per

sons, because of their criminal reputa

tion, have no business communicating

with prisoners. A person does not for

feit his F irs t Amendment rights simply

because he acquires a bad reputation.

In like manner, a prisoner does not lose

the protection of the F irs t Amendment

simply because those with whom he

wishes to communicate are “disreputa