Briggs v. Elliot Transcript of Record

Public Court Documents

June 3, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Briggs v. Elliot Transcript of Record, 1952. 33585387-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8d83fc6d-3945-43b1-b7ed-577d5b6f0490/briggs-v-elliot-transcript-of-record. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

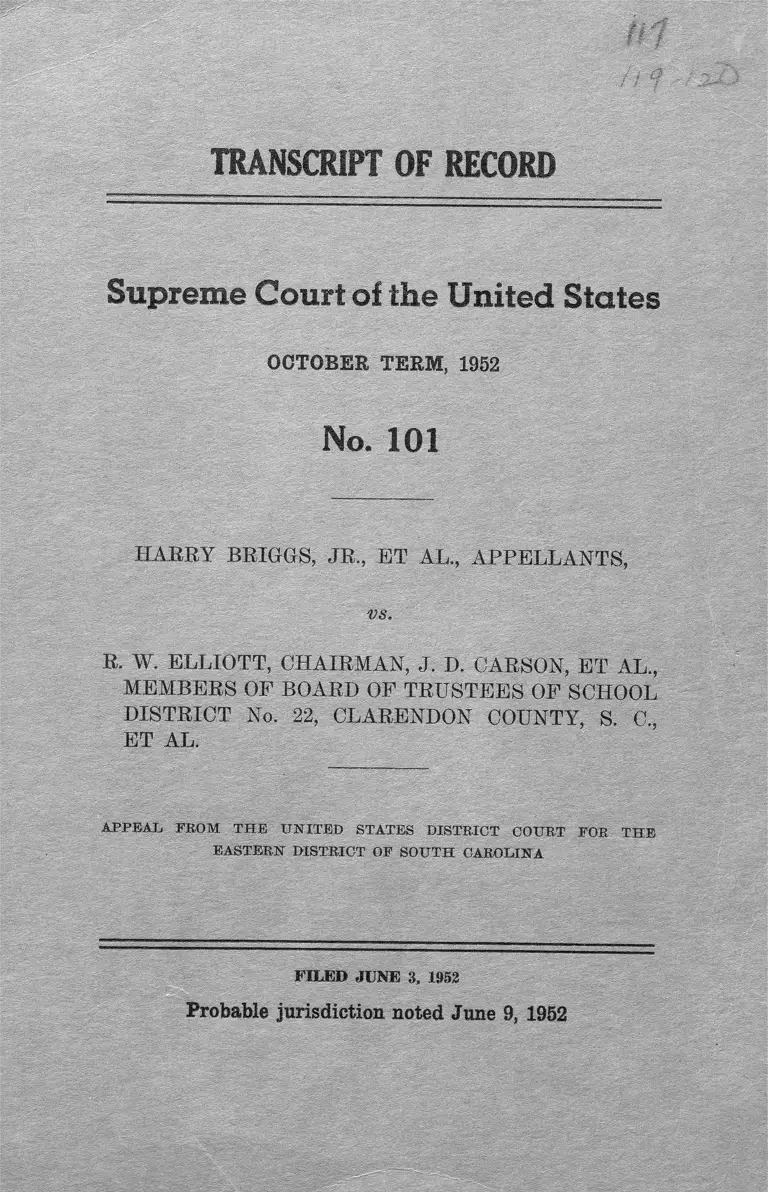

TRANSCRIPT OF RECORD

S u p re m e C o u r t o f th e U n ite d S ta tes

OCTOBER TERM, 1952

N o. 101

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., ET AL., APPELLANTS,

vs.

R. W. ELLIOTT, CHAIRMAN, J. D. CARSON, ET AL.,

MEMBERS OF BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF SCHOOL

DISTRICT No. 22, CLARENDON COUNTY, S. C.,

ET AL.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

FILED JUNE 3, 1952

Probable jurisdiction noted June 9, 1952

¥

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1951

N o. 101

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., ET AL., APPELLANTS,

vs.

R. W. ELLIOTT, CHAIRMAN, J. D. CARSON, ET AL.,

MEMBERS OF BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF SCHOOL

DISTRICT No. 22, CLARENDON COUNTY, S. C.,

ET AL.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

INDEX

Original Print

Record from U.S.D.C. for tlie Eastern District of South

Carolina, Charleston Division............................................... 1 1

Caption ................................................. (omitted in printing) . .

Complaint ......................................................................... 2 1

Answer ................................................................................ 14 12

Exhibit “ A ”— Petition of plaintiffs dated Novem

ber 11, 1949 to the Board of Trustees, etc.......... 21 IS

Exhibit “ B”— Decision o f the Board .................... 27 23

Transcript o f testimony at trial, May 28-29, 1951........ 37 30

Caption ....................................................................... 37 30

Appearances ............................................................. 37 30

Colloquy between court and counsel.............................. 38 30

Opening statement on behalf of plaintiff.............. 45 35

Judd & Dbtweile® (InO.), P rinters, W ashington , D. C., J uly 10, 1952.

— 2805

11 INDEX

Record from U.S.D.C. for the Eastern District of South

Carolina, Charleston Division— Continued

Colloquy between court and counsel— Continued Original Print

Testimony of L. B. McCord .................................... 48 37

R. W . Elliott...................................... 56 43

Matthew J. Whitehead .................... 62 47

Harold McNalley .............................. 99 70

Ellis O'. Knox .................................... 106 75

Kenneth Clark .................................. 116 83

James L. H upp................................ : 138 97

Louis Kesselmann.............................. 144 101

E. R. Crow.......................................... 151 105

H. B. Betchman.................................. 173 120

Devid Krech ...................................... 192 132

Mrs. Helen T ra ger ............................ 198 136

Colloquy between court and counsel...................... 217 148

Testimony of Dr. Robert Redfield from the ease

of Sweatt vs. Painter et al.................................... 230 156

Reporter’s certificate.............. (omitted in printing) . . 310

Opinion, Parker, C. J., filed June 23, 1951.................. 317 176

Dissenting opinion, Waring, J ........................................ 337 190

Decree ........................................................................... 358 209

Appeal papers on first appeal. . (omitted in printing) 360

Report of defendants pursuant to decree dated June

21, 1951 ........................................................................... 438 211

Appendix A— Architect’s drawing o f proposed

addition of Scotts Branch Schools...................... 451 222

Appendix B— Amended building survey and re

port of the Summerton area schools, December

1951 ......................................................................... 453 223

Appendix C— Statistical synopsis of the immediate

and ultimate results of the construction and re

modeling program of School District No. 1. . . . 469 235

Appendix D— November 1951 issue of “ The

Eagle” , student body publication of Scott’s

Branch High School ............................................ 472 239

Order transmitting defendants’ report to United

States Supreme Court ................................................. 488 255

Per curiam opinion o f Supreme Court, dated January-

28, 1952 ......................................................................... 489 256

Plaintiffs’ motion for judgment....................................... 491 258

Order setting date of second hearing for February 29,

1952 ................................................................................. 495 260

Order continuing hearing until March 3, 1952................ 496 261

Clerk’s note re letter of John J. Parker, etc................... 497 261

Letter of John J. Parker, February 9, 1952 to Judges

Waring and Timmerman and reply of Judge War

ing (omitted in printing)............................................. 499

Motion that R. W. Elliott, et al.be made parties to the

suit, etc......................................................... 500 262

INDEX 111

Record from U.S.D.C. for the Eastern District o f South

Carolina, Charleston Division— Continued

Report of the defendants supplementary to the report

filed December 20, 1951.................................................

Copy of House Bill No. 2065..................................

Letter dated .February 15, 1952, E. R. Crow, Di

rector of the State Educational Finance Com

mission to Governor Byrnes................................

Transcript of hearing March 3, 1952..............................

Reporter’s certificate.............. (omitted in printing) . .

Opinion, Parker, C. J., filed March 13, 1952..................

Decree .................................................................................

Petition for appeal ...........................................................

Order allowing appeal .....................................................

Citation on appeal.................. (omitted in printing) . .

Assignment of errors and prayer for reversal..............

Statement required by Rule 12 of the rules o f the Su

preme Court (omitted in printing)............................

Praecipe for transcript.....................................................

Designation of additional portions of the record to be

included in transcript ...................................................

Clerk’s certificate.................... (omitted in printing) . .

Stipulation as to printing.........................................................

Statement of points to be relied upon upon and designation

of parts of record to be printed..........................................

Order noting probable jurisdiction........................................

Original Print

503 263

507a 268

507b 270

508 271

559

562 301

568 306

570 307

573 309

576

578 311

580

660 312

663 314

673

674 314

676 315

678 316

[Caption Omitted]

[File endorsement omitted]

1

[fol. 1]

[fol. 2]

IN UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN D I S T R I C T OF SOUTH CAROLINA,

CHARLESTON DIVISION

Civil Action No. 2657

H arry B riggs, Jr., T h om as L ee B riggs and K ath erin e

B riggs, Infants, by Harry Briggs, Their Father and Next

Friend and Thomas Gamble, an Infant by Harry Briggs,

His Guardian and Next Friend,

W illiam G ibson , Jr., M axin e G ibson , H arold G ibson and

Julia Ann Gibson, Infants, by Anne Gibson, Their

Mother and Next Friend,

M itch ell Oliver and B ichard A llen Oliver , Infants, by

Mose Oliver, Their Father and Next Friend,

Celestine P arson , an Infant by B en n ie P arson , Her

Father, and Next Friend,

S h irley R agin and D elores R agin , Infants, by E dward

R agin , Their Father and Next Friend,

G len R agin , an In fan t, b y W illiam R ag in , His F a th er and

N ext F rien d ,

E lane R ichardson and E m a n u el R ichardson , Infants, b y

Luchrisher Richardson, Their Father and Next Friend,

J am es R ichardson , C harles R ichardson , D orothy R ic h

ardson and Jackson Richardson, Infants, b y Lee Rich

ardson, Their Father and Next Friend,

D an iel B e n n e t t , J o h n B en n ett and Clifton B e n n e t t ,

Infants, by James H. Bennett, Their Father and Next

Friend,

Louis Oliver , J r ., an Infant, b y M ary Oliver , His Mother

and Next Friend,

Gardeneia S tu k e s , W illie M. S tu k e s , Jr., and Louis W.

S tu k e s , Infants by Willie M. Stukes, Their Father and

Next Friend,

1

H

/

>

jU

V

3

/

3

J oe N ath an H en r y , Charles R. H en ry , E ddie L ee H enry

and Phyllis A. Henry, Infants, by G. H. Henry,

Father and Next Friend,

x .

6o1— 101

2

y [fol. 3] Cabbie G eorgia and J ervine G eorgia, Infants, by

Robert Georgia, Tbeir Father and Next Friend,

I R ebecca I. R ichbu rg , an Infant, by R ebecca R ich bu rg , Her

I Mother and Next Frned.

M ary L. B e n n e t t , L il l ia n B e n n ett and J o h n M cK en zie ,

Infants, by Gabrial Tyndal, Their Father and Next

Friend,

E ddie L ee L aw son and S usan A n n L aw son , Infants, by

Susan Lawson, Their Mother and Next Friend.

? y W illie Oliver and M ary Oliver , Infants, b y F rederick

Oliver , Their Father and Next Friend,

H ercules B e n n ett and H ilton .B e n n e t t , Infants, b y

Onetha Bennett, Their Mother and Next Friend,

Z elia R agin and S arah E llen R ag in , Infants, b y H azel

R agin , Their Mother and Next Friend,

\ >-Irene S cott, an Infant, by Henry Scott, Her Father and

Next Friend, Plaintiffs,

vs.

R. W. E l lio tt , Chairman, J. L. Carson and G eorge K e n

n edy , Members of Board of Trustees of School District

#22, Clarendon County, S. C.; Summerton High School

District, a Body Corporate; L. B. McCord, Superintend

ent of Education for Clarendon County and Chairman

A. J. Plowden, W. E. Baker, Members of the County

Board of Education for Clarendon County; and LI. B.

Betchman, Superintendent of School District #22, De

fendants

[fol. 4] C o m plain t—Filed December 22, 1950

1. (a) The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, section 1331. This action

arises under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution

of the United States, section 1, and the Act of May 31, 1870,

Chapter 114, section 16,16 Stat. 144 (Title 8, United States

Code, section 41), as hereinafter more fully appears. The

matter in controversy exceeds, exclusive of interest and

costs, the sum or value of Three Thousand Dollars

($3,000.00).

(b) The jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, section 1343. This action is

authorized by the Act of April 20, 1871, Chapter 22, section

1, 17 Stat. 13 (Title 8, United States Code, section 43), to be

commenced by any citizen of the United States or other

persons within the jurisdiction thereof to redress the depri

vation, under color of a state law, statute, ordinance, regu

lation, custom or usage, of rights, privileges and immunities

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, section 1, and by the Act of May 31,

1870, Chapter 114, section 16, 16 Stat. 144 (Title 8, United

States Code, section 41) providing for the equal rights of

citizens and of all other persons within the jurisdiction of

the United States, as hereinafter more fully appears.

(c) The jurisdiction of this Court is further invoked

under Title 28, United States Code, section 2281. This is

an action for a permanent injunction restraining the en

forcement, operation and execution of provisions of the

Constitution and statutes of the State of South Carolina

by restraining action of defendants, officers of such state,

in the enforcement and execution of such constitutional

provisions and statutes as will appear more fully herein

after.

2. This is a proceeding for a declaratory judgment under

Title 28, United States Code, section 2201, for the purpose

[fol. 5] of determining questions in actual controversy be

tween the parties, to wit:

(a) The question whether Article II, section 7 of the

Constitution of South Carolina (1895) and section 5377 of

the Code of Laws of South Carolina of 1942 which prohibit

infant plaintiffs from attending the only public schools of

Clarendon County, South Carolina affording an education

equal to that afforded all other qualified students who are

not Negroes and which force said plaintiffs to attend segre

gated public elementary and secondary schools set apart

for Negroes in said Clarendon County, South Carolina are

unconstitutional and void as a violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

(b) The question whether the policy, custom, practice

and usage of defendants, and each of them, in denying on

account of race and color, the infant plaintiffs and other

Negro children of public school age residing in Clarendon

County, South Carolina, educational opportunities, ad

vantages and facilities in the public elementary and second-

4

ary schools of Clarendon County, South Carolina, including

those hereinafter specified, equal to the educational oppor

tunities, advantages and facilities afforded and available

to white children of public school age, similarly situated, is

unconstitutional and void, as being a denial of the equal

protection of the laws guaranteed under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution to the United States.

(c) The question whether the policy, custom, practice

and usage of defendants, and each of them, in denying on

account of race and color, the adult plaintiffs and other-

parents and guardians of Negro children of public school

age, similarly situated, residing in Clarendon County,

South Carolina, rights and privileges of sending their chil

dren to public schools in Clarendon County, South Caro

lina, with educational opportunities, advantages and facili

ties, including those hereinafter specified, equal to the edu-

[fol. 6] cational opportunities, advantages and facilities

afforded and available to white children of public school

age is unconstitutional and void, as being a denial of the

equal protection of the laws guaranteed under the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

3. (a) Infant plaintiffs Harry Briggs, Jr., Thomas Lee

Briggs, Katherine Briggs, Thomas Gamble, William Gibson,

Jr., Maxine Gibson, Harold Gibson, Julia Ann Gibson, Mit-

chel Oliver, Richard Allen Oliver, Celestine Parson, Shirley

Ragin, Dolores Ragin, Glen Ragin, Elane Richardson, Em

manuel Richardson, James Richardson, Charles Richardson,

Dorothy Richardson, Jackson Richardson, Daniel Bennett,

John Bennett, Clifton Bennett, Louis Oliver, Jr., Gardeneia

Stukes, Willie M. Stukes, Jr., Louis W. Stukes, Joe Nathan

Henry, Charles R. Henry, Eddie Lee Henry, Phyllis A.

Henry, Carrie Georgia, Jervine Georgia, Rebecca I. Rich-

burg, Mary L. Bennett, Lillian Bennett, John McKenzie,

Eddie Lee Lawson, Susan Ann Lawson, Willie Oliver, Mary

Oliver, Hercules Bennett, Hilton Bennett, Zelia Ragin,

Sarah Ellen Ragin, and Irene Scott are among those gen

erally classified as Negroes; are citizens of the United

States and of the State of South Carolina. They are within

the statutory age limits of eligiblity to attend the public

schools of Clarendon County, South Carolina. They satisfy

all the requirements for admission to such schools and are

5

in fact attending public schools under the supervision,

operation and control of the defendants. These plaintiffs

comprise two general categories, viz., those who are eligible

to attend and are attending public elementary schools and

those who are eligible to attend and are attending public

secondary schools in Clarendon County, South Carolina,

both types of schools being under the direct supervision,

operation and control of defendants.

(b) Adult plaintiffs Harry Briggs, Anne Gibson, Mose

Oliver, Bennie Parson, Edward Ragin, William Ragin,

Luchrisher Richardson, Lee Richardson, James H. Bennett,

[fol. 7] Mary Oliver, Willie M. Stukes, G. H. Henry, Robert

Georgia, Rebecca Richburg, Gabrial Tyndal, Susan Law-

son, Frederick Oliver, Onetha Bennett, Hazel Ragin and

Henry Scott are among those classified as Negroes; are

citizens of the United States and of the State of South

Carolina; are residents of and domiciled in Clarendon

County, South Carolina. They are taxpayers of Clarendon

County, of the State of South Carolina, and of the United

States. They are guardians and parents of the infant

plaintiffs referred to in the paragraph above and designated

in the caption of this bill, and are required by the laws of

the State of South Carolina to send their children under

their charge and control to public or private schools.

4. Plaintiffs bring this action in their own behalf and in

behalf of all other Negro children attending the public

schools in the State of South Carolina, and their parents

and guardians, similarly situated and affected with refer

ence to the matters here involved. They are so numerous

as to make it impracticable to bring them all before the

court. There being common questions of law and fact, a

common relief being sought, as will hereafter more fully

appear, plaintiffs present this action as a class action, pur

suant to Rule 23 (a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Pro

cedure.

5. (a) Defendant, County Board of Education of Clar

endon County, South Carolina, exists pursuant to the laws

of the State of South Carolina as an administrative depart

ment of the State discharging governmental functions.

(Code of Laws of South Carolina of 1942, section 5316).

Defendants A. J. Plowden and W. E. Baker are members of

6

the aforesaid Board and are being sued in their official

capacity.

(b) Defendant, L. B. McCord is chairman of the County

Board of Education of Clarendon County and County Super

intendent of Schools. He holds office pursuant to the laws

of South Carolina as an administraive officer of the State,

charged with overall supervision and government of the

[fol. 8] public schools maintained and operated within the

County of Clarendon. (Code of Laws of South Carolina of

1942, sections 5301, 5303, 5306, 5316) He is being sued in

his official capacity.

(c) Defendant, the Board of Trustees of School District

#22 of Clarendon County, South Carolina exists pursuant

to the laws of South Carolina as an administrative depart

ment of the State, discharging governmental functions,

specifically the maintenance and operation of the public

schools in District #22. (Code of Laws of South Carolina

of 1942, section 5238)

(d) Defendant, R. W. Elliott, is chairman of the Board

of District #22 and of Board of Trustees of Summerton

High School District; defendant J. D. Carson is a member

of the Board of Trustees of School District #22 and Secre

tary of the Board of Trustees of Summerton High School

District; and defendant George Kennedy is a member of

Board of Trustees of District #22 and of the Board of

Trustees of Summerton High School District: all three de

fendants hold office pursuant to sections 5328, 5343 and

5405 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina of 1942. All

are being sued in their official capacity.

(e) Defendant, J. B. Betchman is the Superintendent

of Schools of School District #22. He is the executive officer

of the Board of Trustees of School District #22, charged

with the responsibility of maintaining, managing and gov

erning the public schools in the aforesaid District in accord-

[fol. 9] ance with the rules, regulations and policy laid down

by the Board of Trustees. He is being sued in his official

capacity.

(f) Defendant, the Summerton High School District is a

body corporate pursuant to sections 5404, 5405, 5409 and

5412 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina of 1942 and is

being sued as such.

7

6. (a) The State of South Carolina has declared public

education a state function. The Constitution of South

Carolina, Article II, section 5, provides:

“ Free Public Schools—The General Assembly shall

provide for a liberal system of free public schools for

all children between the ages of six and twenty-one

years . . . ”

Pursuant to this mandate the General Assembly of South

Carolina has established a system of free public schools in

the State of South Carolina according to a plan set out in

Title 31, Chapter 122 of the South Carolina Code of 1942.

The Constitution of South Carolina, Article XI, Section 6

provides for the levying of taxes by the counties of South

Carolina for the purpose of financing public education in

the respective counties. Provision is also made for the dis

tribution of other state funds for this purpose.

7. The Constitution of South Carolina, Article II, sec

tion 7, provides:

“ Separate schools shall be provided for children

of the white and colored races, and no child of either

race shall ever be permitted to attend a school pro

vided for children of the other race. ’ ’

Section 5377 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina of

1942 provides:

“ It shall be unlawful for pupils of one race to attend

the schools provided by boards of trustees for persons

of another race. ”

8. The establishment, maintenance and administration of

public schools in Clarendon County, South Carolina is vested

[fol. 10] in the County Board of Education, County Super

intendent of Education, Board of Trustees and a Superin

tendent of Schools of each school district of the County.

(Constitution of South Carolina of 1895, Article II, sections

1 and 2, Code of Laws of South Carolina of 1942, sections

5301, 5316, 5328, 5404 and 5405)

9. The public schools of the County of Clarendon, South

Carolina, are under the direct control and supervision of

defendants acting as administrative departments or di-

8

visions of the State of South Carolina. (Code of Laws of

South Carolina 1942, sections 5301, 5328, 5404, 5405) De

fendants are under a duty to maintain an efficient system of

Public Schools in Clarendon County, South Carolina (Code

of Laws of South Carolina 1942, sections 5301, 5303 and

5328)

10. The defendants and each of them have at all times

enforced and unless restrained as the result of this action,

will continue to enforce the provisions of the Constitution

and laws of the State of South Carolina set out in paragraph

“ 7” , of this complaint. In enforcement of these provisions

the defendants have set up and are maintaining* one group

of elementary and high schools for all eligible students of

Clarendon County other than Negroes and another group of

schools for students considered to be of Negro descent.

This separation, segregation and exclusion is based solely

upon the race and/or color of the plaintiffs and those on

whose behalf this action is brought and is in violation of

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States. No group of students

save those of Negro descent are excluded from the public

schools of Clarendon County set apart for “ white”

students.

11. The public schools of Clarendon County set apart for

white students and from which all Negro students are ex

cluded are superior in plant, equipment, curricula, and in

all other material respects to the schools set apart for

Negro students. The defendants by enforcing the pro-

[fol. 11] visions of the Constitution and laws of South Caro

lina as set out above exclude all Negro students from the

“ white” public schools and thereby deprive plaintiffs and

others on whose behalf this action is brought solely because

of race and color, of the opportunity of attending the only

public schools in Clarendon County where they can obtain

an education equal to that offered all qualified students who

are not of Negro descent.

12. The public school system in School District #22, and

in the Summerton High School District, Clarendon County,

South Carolina, is maintained on a segregated basis. White

children attend the Summerton Elementary School and

Summerton High School, Negro children are compelled to

9

attend the Scotts Branch High School, the Liberty Hill

Elementary School and the Rambay Elementary School

solely because of their race and color. The Scotts Branch

High School, Liberty Hill Elementary School and the Ram

bay Elementary School are unequal and inferior to the

Summerton High School and the Summerton Elementary

School maintained for white children of public school age.

In short, plaintiffs and other Negro children of public school

age in Clarendon County, South Carolina are being denied

equal educational advantages in violation of the Constitu

tion of the United States.

13. Plaintiffs have filed petitions with defendants, County

Board of Education of Clarendon County, County super

intendent of Schools and the Board of Trustees for School

District #22, requesting that defendants cease discriminat

ing against Negro children of public school age attending

public schools in Clarendon County, South Carolina and

defendants have failed and refused to cease discriminating

against plaintiffs and the class they represent solely be

cause of their race and color in violation of their rights to

equal protection of the laws provided by the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States.

14. Plaintiffs and others similarly situated are suffering

irreparable injury and are threatened by irreparable in-

[fol. 12] jury in the future by reason of the acts herein com

plained of. They have no plain, adequate or complete

remedy to redress the wrongs and illegal acts herein com

plained of other than this suit for declaration of rights and

an injunction. Any other remedy to which plaintiffs and

those similarly situated could be remitted would be attended

by such uncertainties and delays as to deny substantial

relief, would involve a multiplicity of suits, cause further

irreparable injury and occasion damage, vexation and in

convenience not only to the plaintiff and those similarly situ

ated, but to defendants as governmental agencies.

15. Wherefore, plaintiffs respectfuly pray that upon the

filing of this complaint, as may appear proper and con

venient, the Court convene a three-judge court as required

by Article 28, United States Code, Section 2281, 2284, ad

vance this cause on the docket and order a speedy hearing

10

on this action according to law, and that upon such hear

ing :

1. This Court adjudge, decree and declare the rights

and legal relations of the parties to the subject mat

ter here in controversy in order that such declaration

shall have the force and effect of a final judgment or

decree.

2. This Court enter a judgment or decree declaring

that the policy, custom, practice and usage of defend

ants, and each of them, in denying on account of their

race and color, to infant plaintiffs and other Negro

children of public school age in Clarendon County,

South Carolina, elementary and secondary educational

opportunities, advantages and facilities equal to those

afforded to white children is a denial of the equal

protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

3. This Court enter a judgment or decree declaring

that the policy, custom, practice and usage of defend

ants, and each of them, in refusing to allow infant plain

tiffs, and other Negro children, to attend elementary

and secondary public schools in Clarendon County,

South Carolina which are maintained and operated ex-

[fol. 13] clusively for white children is a violation of

the equal protection of the laws as guaranteed under

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

4. This Court enter a judgment or decree declaring

that Article II, section 7 of the Constitution of South

Carolina (1895) and section 5377 of the Code of Laws

of South Carolina of 1942 which require that infant

plaintiffs be forced to attend separate and segregated

schools solely because of their race and color is a denial

of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

and are therefore unconstitutional and void.

5. That the Court issue a permanent injunction for

ever restraining and enjoining the defendants, and

each of them, from denying, failing or refusing to pro

vide to infant plaintiffs and other Negro school chil

dren in Clarendon County, South Carolina, on account

11

of their race and color, rights and privileges of attend

ing public schools where they may receive educational

opportunities, advantages and facilities equal to these

afforded to white children.

6. That the Court issue a permanent injunction for

ever restraining and enjoining the defendants, and

each of them, from making any distinction based upon

race or color in making available to the plaintiffs what

ever opportunities, advantages and facilities are pro

vided by the defendants for the public education of

school children in Clarendon County, South Carolina.

7. That the Court issue a temporary and permanent

injunction restraining and enjoining the defendants

and each of them from operating, executing or enforcing

Article II, section 7 of the Constitution of South Caro

lina (1895) and section 5377 of the Code of Laws of

South Carolina of 1942.

8. Plaintiffs further pray that the Court will allow

them their costs herein and such further, other or addi

tional relief as may appear to the Court to be equitable

and just.

Harold R. Boulware, 11091/2 Washington Street,

Columbia, S. C.; Robert L. Carter, Thurgood

Marshall, 20 West 40 Street, New York 18,

N. Y., Attorneys for Plaintiffs. (Seal.)

A True Copy. Attest: Ernest N. Allen, Clerk of

U. S. District Court, East Dist., So. Carolina.

Dated: December 19, 1950.

12

I n U nited S tates D istrict C ourt

[Title omitted]

A n sw er—Filed January 18, 1951

The defendants above named, answering the complaint

herein, respectfully show and allege:

For a First Defense:

1. That on information and belief the defendants admit

the allegations contained in paragraph 1 of the complaint,

except so much thereof as alleges that the amount in con

troversy exceeds, exclusive of interest and costs, the sum

of $3,000, and so much of paragraph 1 of the complaint as

alleges that the plaintiffs, or any of them, have been de

prived of any right, privilege or immunity secured by the

Constitution of the United States or by the laws of the

United States, which on information and belief they deny.

2. The defendants deny the allegation contained in para

graph 2 of the complaint, and on the contrary allege and

show that the only matter in controversy between the plain

tiffs and the defendants is whether on account of race or

color the defendant The Board of Trustees for School

District No. 22, Clarendon County, South Carolina, had de

nied to plaintiffs schools and educational opportunities,

[fol. 15] advantages and facilities substantially equal to

those afforded white children attending the schools of

School District No. 22 in Clarendon County.

3. That on information and belief the defendants admit

the allegations contained in paragraph 3 (a), and on in

formation and belief admit the allegations contained in

paragraph 3 (b), of the complaint.

4. That on information and belief the defendants deny

the allegations contained in paragraph 4 of the complaint.

5. Answering the allegations contained in paragraph

5 (a) of the complaint, they admit so much thereof as al

leges that the defendants A. J. Plowden and W. E. Baker

are members of the County Board of Education of Claren

don County, South Carolina, and that the said Board was

[fol. 14] [File endorsement omitted]

13

created by Section 5316 of the Code of Laws of South Caro

lina, 1942, and for its powers, duties and functions they

crave reference to the Constitution and Statutes of the

said State.

6. Answering the allegations contained in paragraph

5 (b), the defendant admit that the defendant L. B. McCord

is Chairman of the County Board of Education of Claren

don County and County Superintendent of Education of

the said county, and crave reference to the Constitution

and Statutes of the said State for his powers, duties and

functions.

7. Answering the allegations contained in paragraphs

5 (c) and 5 (d) of the complaint, they admit so much

thereof as alleges that the defendant R. W. Elliott is Chair

man of the Board of Trustees of School District No. 22 of

Clarendon County, South Carolina, and that the defend

ants J. D. Carson and George Kennedy are members of the

said Board, and that the defendant R. W. Elliott is the

Chairman of the Board of Trustees of Summerton High

School District, and that the Board of Trustees of School

District No. 22 of Clarendon County, South Carolina, ex

ists pursuant to the laws of South Carolina, and they crave

reference to the Constitution and Statutes of said State

for its fiowers, duties and functions.

[fol. 16] 8. Answering the allegations contained in para

graphs 5 (e) and 5 (f) of the complaint, they admit the

same.

9. Answering the allegations contained in paragraphs

6 (a), 7 and 8 of the complaint, they crave reference to the

Constitution and Statutes of the State of South Carolina

applicable to public education, the system of free public

schools, the establishment of separate schools for colored

and white persons, and the establishment, maintenance,

management, control and administration of the public

system in Clarendon County, South Carolina.

10. Answering the allegations contained in paragraph 9

of the complaint, they deny the same on information and

belief, and on the contrary allege and show that School

District No. 22 is by law under the management and con

trol of the Board of Trustees of the said school district,

and they crave reference to the Constitution and Statutes

of the State of South Carolina relating to and prescribing

14

the powers, duties and functions of the several defendants

in relation to the public schools in Clarendon County,

South Carolina, and in said School District No. 22 of the

said county.

11. Answering the allegations contained in paragraphs

10, 11 and 12 of the complaint, they admit so much thereof

as alleges that in obedience to the constitutional mandate

contained in Article 11, Section 7, of the Constitution of

South Carolina, separate schools are provided for the

children of the white and colored races, and that no child

of either race is permitted to attend a school provided for

children of the other race. They also admit so much thereof

as alleges that the Summerton Elementary School has been

provided in said district for white children, and that Scott’s

Branch High School, the Liberty Hill Elementary School,

and the Rambay Elementary School have been provided

for Negro children. They allege that the school known

as the Summerton High School is not a school of School

District No. 22, but is a school of Summerton High School

District, a separate corporate school district over which

the Board of Trustees of said School District No. 22 have

no control, which is attended by the white high school

children residing in School District No. 22, along with the

[fol. 17] white high school children of the other four school

districts which comprise such centralized high school dis

trict. They deny the remaining allegations contained in said

paragraphs, and on the contrary allege on information and

belief that the schools of School District No. 22 and the

educational opportunities provieed for Negro school chil

dren attending the schools of said district are substantially

equal to those provided for white school children attend

ing the schools of said district.

12. Answering the allegations contained in paragraph 13,

the defendants admit so much thereof as alleges that the

petition dated November 11, 1949, a copy of which is hereto

attached and marked “ Exhibit A ” and made a part hereof,

was filed by the plaintiffs. They deny on information and

belief so much of said paragraph as alleges that the plain

tiffs and the class they represent are discriminated against

solely because of their race and color, and that their right

to equal protection of the laws provided by the Fourteenth

15

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States is

being violated. On the contrary, they allege on informa

tion and belief that the facts and circumstances relating

to the controversy between the plaintiffs and the defend

ants are as set forth and found in the decision of the Board

of Trustees of the said School District No. 22 filed Feb

ruary 20, 1950, a copy of which is hereto attached and

marked ‘ ‘ Exhibit B ’ ’ and made a part hereof.

13. That on information and belief they deny the allega

tions contained in paragraph 14.

For a Second Defense:

That this action is in part predicated upon the alleged

failure of the defendant The Board of Trustees for School

District No. 22, Clarendon County, South Carolina, and

the individual members comprising the same, to provide

schools and educational opportunities for colored school

children attending the schools of School District No. 22

in Clarendon County which are substantially equal to those

provided for the white school children attending the schools

of the said school district.

[fol. 18] That on the 9th day of February, 1950, the said

Board of Trustees of School District No. 22 held a hearing

upon a petition presented to said board by the plaintiffs

herein, a copy of which petition is hereto attached and

marked “ Exhibit A ” and made a part hereof, at ehich

hearing the plaintiffs as petitioners were represented by

and heard through their counsel.

That on the 20th day of February, 1950, the said Board

of Trustees of School District No. 22, after due considera

tion of the matters arid things set forth in the said peti

tion, made and filed its decision thereon, a copy of which

decision is hereto attached and marked “ Exhibit B ” and

made a part hereof.

That the matters and things set forth in the said peti

tion, and passed upon in the said decision, are matters of

local controversy between the Board of Trustees of the

said school district and the plaintiffs in reference to the

construction and administration of the school laŵ s, to de

termine which the County Board of Education of Claren

don County is by Section 5317 of the Code of Laws of

16

South Carolina, 1942, constituted a tribunal, with the power

to summon witnesses and take testimony, if necessary, and

make a decision which is binding upon the parties to the

controversy, with either of the parties having the right to

appeal to the State Board of Education under Sections

5281 and 5317 of the said Code of Laws, whose decision

“ shall be final upon the matter at issue.”

That the provision of school buildings is within the func

tions devolved by law upon the trustees of the respective

school districts of each county, and each school district is

by law placed under the management and control of the

board of trustees thereof, and the matters and things set

forth in the said petition and involved in this action are

matters of local controversy in reference to the construc

tion or administration of the school laws, for the determi

nation of which the administrative procedure and adminis

trative remedies are provided in said laws, so that adminis

trative means and power will exist to direct affirmative ac

tion on the part of boards of trustees in cases where it may

[fol. 19] be determined that they have not properly or law

fully constructed or administered the said school laws.

That the plaintiffs have taken no action to challenge

the validity or correctness of the decision of the Board of

Trustees of School District No. 22, filed on the 20th day

of February, 1950, before the County Board of Education of

Clarendon County, or to appeal the same to the State Board

of Education, and it is respectfully prayed and moved by the

defendants that the Court conclude and hold that this action

for a declaratory judgment should not be entertained and

decided by this Court unless and until the plaintiffs have

availed themselves of the administrative procedure and

remedies provided in and by the school laws of the State

of South Carolina.

For a Third Defense:

That this action is in part predicated upon the assertion

that Article 11, Section 7, of the Constitution of the State

of South Carolina, 1895, and Section 5377 of the Code of

Laws of South Carolina, 1942, providing that separate

schools shall be provided for children of the white and col

ored races, and prohibiting shildren of either race from

17

attending schools provided for children of the other race,

deny equal protection of the laws to the plaintiffs, in viola

tion of Article Fourteen of the Amendments to the Con

stitution of the United States.

That the State constitutional and statutory provisions re

ferred to were adopted in the exercise of the police power of

the State of South Carolina, and are a reasonable exercise

of such power, taking into account the established usages,

customs and traditions of the people of the said State, the

promotion of their comfort, and the preservation of the

public peace and good order.

That in and by said constitutional and statutory pro

visions the State of South Carolina has secured to each of

its citizens equal rights before the law and educational op

portunities, advantages and facilities which, while not iden

tical, are substantially equal.

[fol. 20] That the constitutional and statutory provisions

under attack herein, as a reasonable exercise of the State’s

police power under all of the considerations and circum

stances which it may in good faith take into account in

measures for the promotion of the public good, is valid

under the powers possessed by the State of South Carolina

under the Constitution of the United States, and cannot be

held unconstitutional by this Court.

Wherefore, Having fully answered the said complaint,

the defendants pray that the same be dismissed.

(S.) S. E. Rogers, Summerton, S. C. (S.) Robert

McC. Figg, Jr., 207 Peoples Office Building,

Charleston, S. C. Attorneys for the Defendants.

2—101

18

[ fo l . 21] “ E x h ib it A ” to A nsw er

P etition

S tate oe S o u th Carolin a ,

County of Clarendon:

T o : The Board of Trustees for School District Number 22,

Clarendon County, South Carolina, R. W. Elliott, Chair

man, J. D. Carson and George Kennedy, Members; The

County Board of Education for Clarendon County, South

Carolina, L. B. McCord, Chairman, Superintendent of

Education for Clarendon County, A. J. Plowden, W. E.

Baker, Members, and H. B. Betchman, Superintendent

of School District #22.

Your petitioners, Harry, Eliza, Harry, Jr., Thomas Lee,

Katherine Briggs, and Thomas Gamble; Henry, Thelma,

Vera, Beatrice, Willie, Marian, Ethel Mae and Howard

Brown; James Theola, Thomas Euralia and Joe Morris

Brown; Onetha, Hercules and Hilton Bennett; William,

Annie, William Jr., Maxine and Harold Gibson; Robert,

Carrie, Charlie and Jervine Georgia; Gladys and Joseph

Hilton; Lila Mae, Celestine and Juanita Huggins; Gussie

and Roosevelt Hilton; Thomas, Blanche E., Lillie Eva,

Rubie Lee, Betty J., Bobby M. and Preston Johnson; Susan,

Raymond, Eddie Lee and Susan Ann Lawson; Frederick,

Willie and Mary Oliver; Mose, Leroy and Mitchel Oliver;

Bennie, Jr., Plummie and Celestine Parson; Edward,

Sarah, Shirley and Deloris Ragin; Hazel, Zelia and Sarah

Ellen Ragin; Rebecca and Mable Ragin; William and Glen

Ragin; Lychrisher, Elane and Emanuel Richardson; Re

becca and Rebecca I. Richburg; E. E. and Albert Rich-

burg; Lee, Bessie, Morgan and Samuel Gary Johnson;

Lee, James, Charles, Annie L., Dorothy and Jackson

Richardson; Mary 0., Francis and Benie Lee Lawson;

Mary, Daisy and Louis, Jr., Oliver; Esther F. Singleton

and Janie Fludde; Henry, Mary and Irene Scott; Willie

M., Gardenia, Willie M. Jr., Gardenia, and Louis W.

Stukes; Gabriel and Annie Tindal, Mary L. and Lilliam

Bennett, children of public school age, eligible for elemen

tary and high school education in the public schools of

School District #22, Clarendon County, South Carolina,

19

their parents, guardians and next friends respectfully

represent:

[fol. 22] 1. That they are citizens of the United States

and of the State of South Carolina and reside in School

District #22 in Clarendon County and State of South

Carolina.

2. That the individual petitioners are Negro children of

public school age who reside in said county and school dis

trict and now attend the public schools in School District

#22, in Clarendon County, South Carolina, and their

parents and guardians.

3. That, the public school system in School District #22,

Clarendon County, South Carolina, is maintained on a

separate, segregated basis, with white children attending

the Summerton High School and the Summerton Elemen

tary School, and Neg*ro children forced to attend the Scott

Branch High School, the Liberty Hill Elementary School

or Rambay Elementary School solely because of their race

and color.

4. That the Scott’s Branch High School is a combination

of an elementary and high school, and the Liberty Hill and

Rambay Elementary Schools are elementary schools solely.

5. That the facilities, physical condition, sanitation and

protection from the elements in the Scott’s Branch High

School, the Liberty Hill Elementary School and Rambay

Elementary School, the only three schools to which Negro

pupils are permitted to attend, are inadequate and

unhealthy, the buildings and schools are old and over

crowded and in a dilapidated condition; the facilities,

physical condition, sanitation and protection from the

elements in the Summerton High in the Summerton

Elementary Schools in school district number twenty-two

are modern, safe, sanitary, well equipped, lighted and

healthy and the buildings and schools are new, modern,

uncrowded and maintained in first class condition.

6. That the said schools attended by Negro pupils have

an insufficient number of teachers and insufficient class

room space, whereas the white schools have an adequate

complement of teachers and adequate class room space for

the students.

7. That the said Scott’s Branch High School is wholly

deficient and totally lacking in adequate facilities for teach-

20

[fol. 23] ing courses in General Science, Physics and

Chemistry, Industrial Arts and Trades, and has no

adequate library and no adequate accom-odations for the

comfort and convenience of the students.

8. That there is in said elementary and high schools

maintained for Negroes no appropriate and necessary cen

tral heating system, running water or adequate lights.

9. That the Summerton High School and Summerton

Elementary School, maintained for the sole use, comfort

and convenience of the white children of said district and

county, are modern and accredited schools with central

heating, running water, adequate electric lights, library

and up to date equipment.

10. That Scott’s Branch High School is without services

of a janitor or janitors, while at the same time janitorial

services are provided for the high school maintained for

white children.

11. That Negro children of public school age are not

provided any bus transportation to carry them to and from

school while sufficient bus transportation is provided to

white children traveling to and from schools which are

maintained for them.

12. That said schools for Negroes are in an extremely

dilapidated condition, without heat of any kind other than

old stoves in each room, that said children must provide

their own fuel for said, stoves in order to have heat in the

rooms, and that they are deprived of equal educational

advantages with respect to those available to white children

of public school age of the samd district and country.

13. That the Negro children of the public school age in

School District #22 and in Clarendon County are being

discriminated against solely because of their race and color

in violation of their rights to equal protection of the laws

provided by the 14th amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

14. That without the immediate and active intervention

of this Board of Trustees and County Board of Educa

tion, the Negro children of public school age of aforesaid

district and county will continue to be deprived of their

constitutional rights to equal protection of the laws and to

freedom from discrimination because of race or color in

the educational facilities and advantages which the said

21

[fol. 24] District #22 and Clarendon Comity are under a

duty to afford and make available to children of school age

within their jurisdiction.

Wherefore, Your petitioners request that: (1) the Board

of Trustees of School District Number twenty-two, the

County Board of Education of Clarendon County and the

Superintendent of School District #22 immediately cease

discriminating against Negro children of public school age

in said district and county and immediately make available

to your petitioners and all other Negro children of public

school age similarly situated educational advantages and

facilities equal in all respects to that which is being pro

vided for whites; (2) That they be permitted to appear

before the Board of Trustees of District #22 and before

the County Board of Education of Clarendon, by their

attorneys, to present their complaint; (3) Immediate action

on this request.

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

Dated 11 November 1949

Harry Briggs

Eliza Briggs

Harry Briggs, Jr.

Thomas Lee

̂Briggs

Katherine Eliza

Briggs

Thomas Gamble

Henry Brown

Thelma Brown

Yera Brown

Beatrice Brown

Willie II. Brown

Marion Brown

Ethel Mae Brown

Howard Brown

James Brown

Theola Brown

Thomas Brown

Euralia Brown

Joe Morris Brown

Onetha Bennett

Hercules Bennett

(Signed) Maxine Gibson

(Signed) Harold Gibson

(Signed) Robert Georgia

(Signed) Carrie Georgia

(Signed) Charlie Georgia

(Signed) Jervine Georgia

(Signed) Gladys E. Hilton

(Signed) Joseph Hilton

(Signed) Henrietta Hug

gins

(Signed) Lila Mae Huggins

(Signed) Celestine Huggins

(Signed) Juanita Huggins

(Signed) Gussie Hilton

(Signed) Roosevelt Hilton

(Signed) Thomas Johnson

(Signed) Blanch E. John

son

(Signed) Lillie Eva John

son

(Signed) Rubie Lee John

son

(Signed) Betty J. Johnson

22

[fol. 25] (Signed) Hilton C.

Bennett

(Signed) William Gibson

(Signed) Annie Gibson

(Signed) William Gibson,

Jr.

(Signed) Eddie Lee Law-

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

son

Snsan Ann Law-

son

Frederick Oliver

Willie Oliver

Mary Oliver

R. M. Mose Oliver

Leroy Oliver

Mitchel Oliver

Bennie Parson,

Jr.

Plummie Parson

Celestine Parson

Edward Ragin

Sarab Ragin

Shirley Eagin

Deloris Eagin

Hazel Eagin

Zelia Eagin

Sarah Ellen

Eagin

Eebecca Ragin

Mable Eagin

William Ragin

Ellen Ragin

Lnchrisker

Richardson

Elane Richardson

Emanuel L.

Richardson

Rebecca Riehburg

Rebecca I.

Riehburg

E. E. Riehburg

Albert Riehburg

''Signed)

f Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

Lee Johnson

Bessie Johnson

Morgan Johnson

Samuel Gary

J ohnson

Bobby M. John

son

Preston Johnson,

Jr.

Susan Lawson

Raymon Lawson

Lee Richardson

James Richard

son

(Signed) Charles Richard

son

(Signed) Annie L. Rich

ardson

(Signed) Dorothy I. Rich

ardson

(Signed) Jackson Richard-

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

(Signed)

son

Mary 0. Lawson

Francis Lawson

Bennie Lee Law-

son

Mary J. Oliver

Daisy D. Oliver

Louis Oliver, Jr.

Esther F.

Singleton

Janie L. Fludde

Henry Scott

Mary Scott

Irene Scott

Willie M. Stukes

Gardenia Stukes

Willie Modd

Stukes, Jr.

Gardenia E.

Stukes

Louis W. Stukes

23

(Signed) Gabriel Tindal

(Signed) Annie S. Tindal

[fol. 26] Attorneys for Peti

tioners :

(Signed) Harold E. Boni-

ware

(Signed) Mary L. Bennett

(Signed) Lillian Bennett

(Signed) Thurgood Mar

shall

(Signed) Robert L. Carter

[fol. 27] “ E xhibit B ” t o A nswer

Before the Board of Trustees of School District No. 22

State oe South Carolina,

County of Clarendon:

In Re: H arry B riggs, et ah, Petitioners

Decision of the Board

This matter comes before the Board on the Petition of

Harry, Eliza, Harry, Jr., Thomas Lee, Katherine Briggs,

Thomas Gamble, and others, dated November 11, 1949; the

matters and things alleged in the Petition are clearly matter

of local controversy with reference to the construction and

administration of school laws, and clearly come within the

purview of Section 5317, 5343, 5358, and related sections of

the Code of Laws for South Carolina for 1942, and the

Board of Trustees has original jurisdiction to hear the mat

ters and things complained of. Accordingly, the Petitioners

were granted a hearing on the 9th day of February, 1950, at

which all of the members of the Board were present, and at

which the Petitioners were represented by Counsel, who

made an argument to the Board. Although an opportunity

was afforded to the Petitioners to introduce any testimony

relating to the allegations of the Petition, the Attorney for

the Petitioners, conceding that the Board was familiar with

all of the facts relating to the matters and things complained

of, did not offer testimony or other evidence of any kind

whatsoever.

After investigation and careful consideration, the Board

finds as follows: 1

1. The allegations of the first and second paragraphs of

the Petition are found to be true;

24

2. It is true that the public school system in School Dis

trict No. 22 is maintained on a separate and segregated basis

[fol. 28] as required by the Constitution and Laws of the

State of South Carolina, with the Negro children attending

schools maintained for them and the white children attend

ing schools maintained for them. The records of the district

show that there — 684 negro children of elementary school

age residing in, and attending the public schools of, School

District No. 22, and that there are 102 white children of

elementary school age residing in, and attending the public

schools of, School District No. 22. That likewise, there are

34 white children of high school age residing in School Dis

trict No. 22, and 150 negro children of high school age at

tending the public schools of School District No. 22; that

because of the great number of negro elementary school

students, the Board, in the exercise of its discretion and in

order to furnish education facilities which it deemed to be

to the greatest advantage and convenience of the children

and the patrons of th- school system, established and main

tains three elementary schools for negro children, located in

different parts of the District, to-wit: The Rambay Ele

mentary School, Liberty Hill Elementary School, and

Scott’s Branch Elementary School; because of the small

number of white elementary school children residing in

District 22, it was impracticable to operate and maintain

more than one elementary school for white children in the

District, and this is maintained in Summerton. The number

of negroes of High school age warranted the establishment

and maintenance of a high school in the District for negroes

and this is maintained in Summerton as the Scott’s Branch

High School. The number of white high school students

residing in the District would not, in the opinion of the

Trustees, warrant the maintenance of a high school for white

students by District No. 22; therefore, no high school for

white students is maintained;

3. The allegations of paragraph 4 are true;

[fol. 29] 4. With reference to the allegations of paragraph

5 of the Petition, the Rambay School was erected within the

last 6 years, the Liberty Hill School and the Scott’s Branch

School were erected less than 15 years ag*o; that these

schools were erected with the advice and co-operation of the

State Department of Education and according to the latest

25

approved plans for educational buildings in use at the time;

and in line with the trends for school buildings, are of one

storied construction for safety in the event of storm or fire,

with proper placement of windows for correct lighting for

student use for the prevention of eye strain, are strongly

constructed and storm sheeted, and in all respects were

properly constructed and maintained and are not in poor

physical condition or in a delapidated condition. The white

school, maintained by School District No. 22 in Summerton,

being the only one maintained by the District, is a two-

storied building made of sand block dug from the premises,

erected in 1907; improperly lighted and fails in every re

spect to meet the requirements of modern school architec

ture. A comparison of the white school and the colored

school in Summerton, both maintained by the District is

revealing. The white school as stated above is more than

43 years old, is a two-storied structure, contains 8 rooms, is

improperly lighted according to modern standards, is

antiquated, and its physical condition is such that it has

been a source of dissatisfaction to both patrons and trustees.

It was erected at an original cost of approximately $25,-

000.00, is now insured with the sinking fund for $28,000.00,

and there is a possibility of the insured value being cut even

lower than this. The Scott’s Branch School is less than 15

years old, is built according to approved plans for educa

tional buildings, taking into consideration the proper light

ing and protection from fire, contains in the main building

10 rooms and 3 additional rooms have been recently con

structed by the Trustees, making a total of 13 rooms avail

able. Its original cost was approximately $18,000.00 and

[fob 30] the building is now insured for $24,000.00. Neither

of the schools has a central heating system, both being

heated by individual stoves in the various rooms. The play

grounds provided and used in connection with Scott’s

Branch School are approximately 7 times the size of the

playgrounds of the white school. The white school is located

in one of the lowest areas in the Town, and on two highways

and on a Street over which passes the traffic of two main

North-South Highways. Since its erection, the shift of

white population has caused it to be most inconvenient and

hazardous. The Scott’s Branch High School is erected on

a site selected with advice of the patrons with due ragard for

26

the safety of the children and the convenience of the patrons.

A cursory inspection only will reveal that the facilities,

physical condition, equipment, safety, and protection from

the elements are accordingly better with the negro schools

than the whites, although the Trustees are of the opinion

that they are in all respects substantially equal;

With reference to sanitation, all of the negro schools are

provided with sanitary toilet facilities erected according to

the specifications of the State Health Department. These

same facilities were in use in the white schools until the

Town of Summerton installed a municipal water and sewer

age system. This system happens to service the area in

which the white school is located, and after its installation

by the municipal authorities, the Board of Trustees per

mitted the white Parent-Teacher Association to install sani

tary toilet facilities in two of the cloak rooms of the white

school. The municipal sewerage system does not serve the

area in which the Scott’s Branch School is situate, and no

such request has been received from the Patrons ’ organiza

tion of the Scott’s Branch School, and because of the fact

that the municipal system does not serve the area in which

[fob 31] Scott’s Branch School is located, it would be im

practicable for sanitary toilet facilities to be installed

therein. Certainly, however, there has been no discrimina

tion by the Board on account of color in its failure to provide

such facilities, first because the municipal sewer system is

not available, and second because the Board of Trustees did

not make the installation in the white school, but the same

was done by the patrons of the school. It is worth comment,

however, that although the municipal water system does not

serve the area in which the negro school is located, the

Board, at a great expense to itself, laid a water line from the

municipal system to the Scott’s Branch School for the pur

pose of furnishing municipal water, which is regularly in

spected, to the negro students, which line was installed and

terminated under the direction of the colored school au

thorities. The patrons of the white school, not the school

board, furnished drinking fountains for the white school.

There are no inside drinking fountains in the Scott’s Branch

School, but if the patrons desire to install them, there cer

tainly would be no objections to their being installed. The

School Board even went further and installed the outside

27

drinking fountains at the Scott’s Branch School, although

they did not do so at the white school;

5. With reference to the allegations of paragraph 6, the

Board calls attention to the fact that the State Aid for the

payment of teachers ’ salary is based upon average attend

ance. The average attendance in the white school of the

district is 95%, while the average attendance at the negro

school is 72%. The Board, in hiring teachers for both white

and colored schools, is governed by the State Aid, and

teachers for all schools, both white and colored, in the Dis

trict, are hired on the basis of this, and there is no dis

crimination in the hiring of teachers on the basis of color;

[fol. 32] The school operated for whites has 7 rooms for

class room for class room purposes, and 7 teachers. The

Scott’s Branch School has 13 rooms for class room pur

poses and 14 teachers. The average attendance in the white

school is 190. The average attendance in the Scott’s Branch

School is 468. Attention should be called to the fact that

the white school building, errected in 1907, formerly housed

an elementary school and a high school, but that the number

of white high school students available in the district be

came so small as not to warrant the continuance of a high

school by the District, and the same was eleiminated in

1935, while District has conducted no white high school since

then, the white elementary school continues to use the

building;

6. The allegations of paragraph 7, 8, 10 and 12 allege

that the Scott’s Branch High School is deficient and totally

lacking in adequate facilities for teaching courses in general

science, physics, chemistry, and industrial arts and trades,

has no adequate library, and no adequate accommodations

for the convenience of the students. That there is no cen

tral heating system, running water, or adequate lights, and

that the Scott’s Branch High School is without the serv

ices of a janitor or janitors, while paragraph No. 9 alleges

that the white schools have such services. These allegations

are based upon incorrect information. The fact that neither

the white nor the colored schools have central heating

system has been clarified hereinabove. Both have running

water and both have adequate electric lights. There is no

running water at the Rambay or Liberty Hill Schools,

because there is no running water available. Liberty Hill

28

School has electric lights. There is no electric line in the

vicinity of Rambay School. Fuel for all schools in the

District, both white and colored, is furnished by the Board

on request of the principal of the school, and it appears

that all such fuel has been furnished for the present school

year by the Board.

[fol. 33] Facilities are furnished in Scott’s Branch High

School for the teaching of general science, chemistry, and

agriculture. No such facilities are furnished by the District

at the white High School, inasmuch as the district maintains

no high school for whites, there being insufficient white

pupils in the District to warrant the maintenance of such

a school. The Scott’s Branch School Library contains 1678

books, containing 56 encyclopedias, 21 progressive refer

ence sets, 3 dictionaries, and other books of suitable mate

rial for a school library. The white school library contains

only 642 volum-s with 9 reference sets. None of the li

braries are furnished to any of the schools but have been

donated by various individuals and organizations. The

white elementary school has part time janitorial service.

The janitorial services of the white school are furnished

by one janitor, while at the request of the principal of the

Scott’s Branch School, the janitorial services there are

performed by various students selected by the principal.

The janitor is under the authority of the principal and

should perform, and does perform, such services as the

principal requests. The cost of janitorial services for the

white school to the district is $18.00 per month, while the

cost of the janitorial services to the colored school is $16.00

per month. If the method of using students as janitors is

not satisfactory to the patrons of the colored school, we feel

sure that the principal would be glad to discontinue the

same;

7. The allegations of paragraph 11 allege that the negro

children of public school age are not provided any bus

transportation, while sufficient bus transportation is pro

vided for white children. This allegation is based upon

misinformation. School District No. 22 provided no trans

portation by bus or otherwise for any students, white or

colored;

At the request of the Board, the principal of Scott’s

Branch School made a survey on October 25, 1949, listing

29

[fols. 34-36] the needs of the school. Under that date he

transmitted to the Board the following recommendations:

“ Wood and Coal

Twelve sc/ittles and shovels

Six Boxes of crayon and 12 erasers

11 doors and window locks

Material (Lumber and Nails) to repair windows and

sashes

Three additional classrooms

Three additional teachers

One teacher for the 7th grade, one for the second grade,

and a music teacher for eighth grade, through twelfth

grade

Sanitary material, toilet paper, soap, powder, etc.

A Janitor for the school which is very essential to good

health; who will keep plant in a good condition;”

The Board granted every request listed and all of the

things requested have been furnished, except a music

teacher. The Board made diligent efforts to locate a

teacher who could handle music, but so far has not been

able to find the proper combination. It is fitting to call

attention to the fact that no music teacher is furnished in

connection with the white school;

In conclusion, the Board finds that the negro children of

public school age in school district No. 22 are not being

discriminated against them because of their race and color,

and that there is no violation of the rights to equal protec

tion of the laws as provided by the Constitution of the

United States, but on the contrary, the Board finds that the

facilities afforded to the white and negro children of Dis

trict No. 22, though separate, are substantially equal.

B. M. Elliott, Chairman; C. I). Kennedy, J. B. Car-

son, Clerk, Trustees of School District No. 22, of

Clarendon County, South Carolina.

Summerton, S. C.

February 20, 1950.

30

[File endorsement omitted]

I n U nited S tates D istrict C ourt

[fol. 37]

[Title omitted]

Transcript of Testimony at Trial—Filed July 25, 1951

At a special term of court, trial of the above case was held

at Charleston, South Carolina, in the United States Court

room on May 28-29, 1951, at 10 o ’clock a. m.

Before Honorable John J. Parker, United States Circuit

Judge (4th Circuit); Honorable J. Waties Waring,

United States District Judge (EDSC); Honorable George

Bell Timmerman, United States District Judge

(E&WDSC)

A ppe aran ce s :

Thurgood Marshall, Esq., (Admitted pro hac vice);

Robert L. Carter, Esq., (Admitted pro hac vice); Harold R.

Boulware, Esq.; Spotswood W. Robinson, III, Esq., (Ad

mitted pro hac vice); A. T. Walden, Esq., (Admitted pro

hac vice); Arthur Shores, Esq., (Admitted pro hac vice),

for Plaintiffs.

[fol. 38] Robert McC. Figg, Jr., Esq., S. E. Rogers, Esq.,

T. C. Callison, Esq., Attorney General, State of South

Carolina, for Defendants.

C olloquy B etw een C ourt and C ounsel

Judge Parker: This court is convened in special session

to hear this case, Briggs and others vs. R. W. Elliott and

others. Is counsel for the plaintiffs ready?

Mr. Boulware: We are ready, your Honor.

Judge Parker: Are defendants ready?

Mr. F igg: Defendants are ready and I would like to make

a statement for the defendants, if the Court please. This

is an action brought by colored children of elementary,

grammar and high school grades residing in School District

No. 22 in Clarendon County, and their parents and guard

3 1

ians, for a declaratory judgment on questions which, from,

the complaint, may be stated as follows:

(a) Whether their rights under the equal protection of

the laws clause------

Judge Parker: Are you making an opening statement?

If so, we will hear that in due course.

Mr. F igg: If the Court please, I wanted to make a state

ment on behalf of defendants that it is conceded that in

equalities in the facilities, opportunities and curricula in

the schools of this district do exist. We have found that

[fol. 39] out from investigating authorities.

Judge Parker: You will do that when you make your

opening statement.

Mr. Figg: I just thought that if we made the record

clear and clarified the answer in this case at this time, it

would serve perhaps to eliminate the necessity of taking a

great deal of testimony.

Judge Parker: All right: I still think the time to do it is

when you are making your opening statement, but if you

want to make it now, go ahead.

Mr. Figg: (a) Whether their rights under the equal pro

tection of the laws clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to

educational opportunities, advantages and facilities equal

to those offered and available to white children of the same

grades have been denied; and

(b) Whether the provisions of the South Carolina Con

stitution and statutes “ which prohibit” the colored children

of the school district “ from attending the only public

schools of Clarendon County, South Carolina, affording an

education equal to that afforded” to white children are