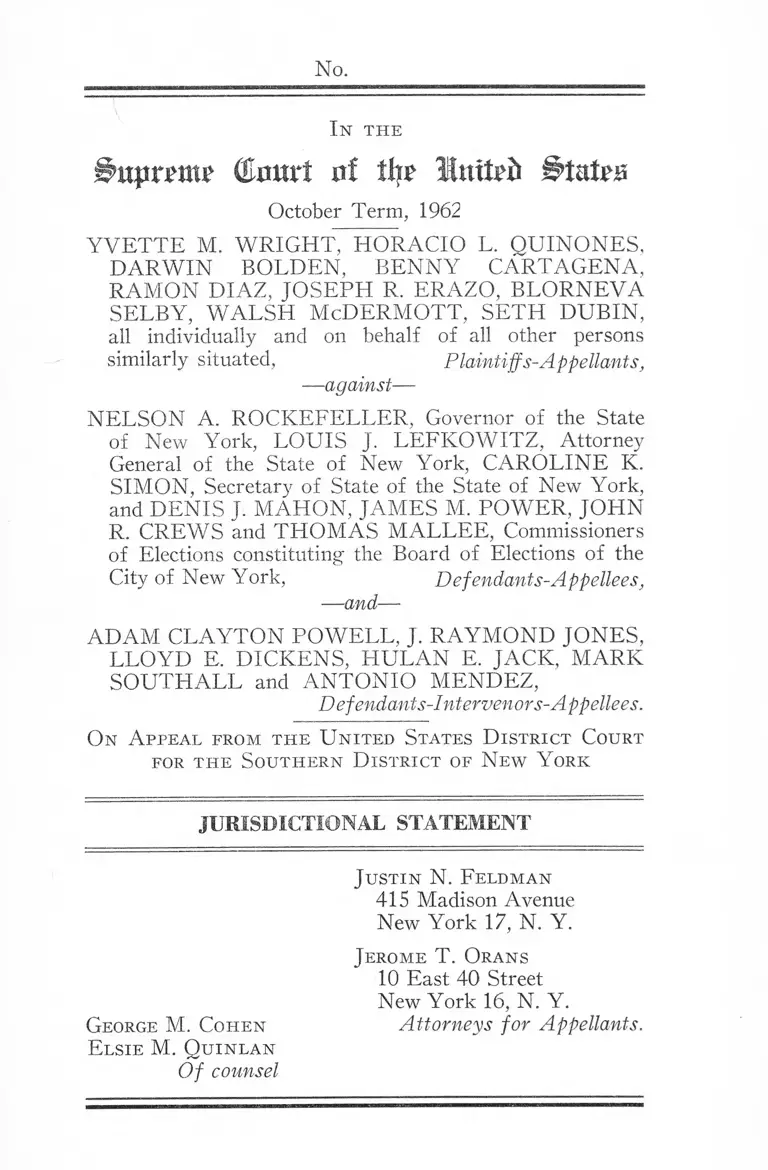

Wright v. Rockefeller Brief for Appellants Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wright v. Rockefeller Brief for Appellants Jurisdictional Statement, 1962. c90c20a3-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8d9d83f7-2202-4d58-ba1a-c883663d5593/wright-v-rockefeller-brief-for-appellants-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No.

I n t h e

^uprrn? (Emtrt n! tit?

October Term, 1962

Y V E T T E M. W RIG H T, H ORACIO L. QUINONES.

D A R W IN BOLDEN, BEN N Y CARTAGEN A,

RAM ON DIAZ, JOSEPH R. ERAZO, BLORN EVA

SELBY, W A LSH M cD ERM OTT, SETH DUB IN,

all individually and on behalf of all other persons

similarly situated, Plaintiffs-Appellants,

— against—

NELSON A. ROCKEFELLER, Governor of the State

of New York, LOUIS J. LE FK O W ITZ, Attorney

General of the State of New York, CAROLIN E K.

SIMON, Secretary of State of the State of New York,

and DENIS J. M AHON, JAMES M. POW ER, JOHN

R. CREW S and TH O M A S M ALLEE, Commissioners

of Elections constituting the Board of Elections of the

City of New York, Defendants-Appellees,

— and—

A D AM CLAYTO N POW ELL, J. RAYM O N D JONES,

LLOYD E. DICKENS, H U LAN E. JACK, M ARK

SO U TH ALL and AN TO N IO MENDEZ,

D efendants-Intervenors-A ppellees.

O n A ppeal from t h e U n ited States D istr ic t C ourt

for t h e S o u th e r n D istr ic t of N ew Y ork

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Ju s t in N. F e ld m an

415 Madison Avenue

New York 17, N. Y.

Jerom e T. O rans

10 East 40 Street

New York 16, N. Y.

G eorge M. C o h en Attorneys for Appellants.

E lsie M. Q u in l a n

O f counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion Below ....................... 1

Jurisdiction ......................................................................... 2

Questions Presented ............ 2

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved.......... 3

Statement ....................... 3

The Questions Presented Are Substantial................... 10

Conclusion .................................................................... 17

A p p e n d ix A

Opinion. Moore, C. J................................................. .. . la

Opinion, Feinbergf, D. J................................................ 17a

Opinion, Murphy, D. J.............. ................................. 25a

A p p e n d ix B

United States Constitution, Federal Statutes, State

Statutes and legislative history ............................ lb

A p p e n d ix C

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2B ................................................. 1c

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3 ..................... 2c

Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 4, 4A and 4B .......................... 3c

11

CITATIONS

PAGE

Cases :

Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 1 8 6 .................................... 13

Branche v. Board o f Education, 204 F. Supp. ISO

(E. D. N. Y. 1962) ............................................... 15

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ........ 13

Bush v. New Orleans Parish School Bd., 188 F.

Supp. 916, aff’d, 365 U. S. 569 ............................ 14

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town, 229 N. Y. 5 1 2 ........... 7

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584 ...................... 15

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 329 . ..................13, 15

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475 ..................... 4, 9, 15

N A A C P v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 ....................... 15

N A A C P v. Button, 371 U. S. 4 1 5 ............................ 15

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 .............................. 15

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 .......................... 15

Orvis v. Higgins, 180 F. 2d 537 at n. 6 (2d Cir.

1950), cert. den. 340 U. S. 8 1 0 ........................... 10

Progress Development Corp. v. Mitchell, 182 F.

Supp. 681 (N. D. 111. 1960) aff’d, 286 F. 2d 222

(7th Cir. 1961) ..................... '................................. 13

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U. S. 49 . ...................... 10

U n ited States C o n s t it u t io n :

Article 1 § 3 ............................................................. .. 4

Amendment X IV , § 1 ................................................. 3, 4

Amendment X V , § 1 ................................................... 3; 4

PAGE

F ederal S t a t u t e s :

28 U. S. C. § 2281 ..................................................... 2, 4

28 U. S. C. § 2284 ...................................................... 4

28 U. S. C. § 1253 ...................................................... 2

2 U. S. C. § 2 (a ) ...................................................... 3

42 U. S. C. § 1983 ....................................................... 3

42 U. S. C. § 1988 ...................................................... 3

28 U. S. C. § 1343 (3 ) ............................................... la

28 U. S. C. § 2201 ...................................................... 4

28 U. S. C. § 2202 ...................................................... 3

N ew Y ork State St a t u t e s :

Chapter 980 ; 1961 Laws of the State of New York 2, 3

M iscellan eous :

New York State Legislative Document No. 45

(1961) ................... .............................................. .. 3

N. Y. C. Board of Education, Toward Greater

Opportunity, 155 (1960) ...................................... 4

2 Moore’s Fed. Pract. 1687 (1953) .......................... 16

Note, 70 Yale L. J. 126 (1 9 6 0 ) .................................. 13

Bittker, The Case o f the Checkerboard Ordinance

71 Yale L. J. 1387 (1962) .................................... 13

Ill

I n t h e

ûpr̂ m? Court of fljr H&nxttb #tatro

O ctober T e r m , 1962

Y vette M. W r ig h t , H oracio L. Q u in o n e s , D a r w in

B olden , B e n n y Car ta g e n a , R a m o n D ia z , Joseph R.

E razo , B lorneva Se lb y , W a l sh M cD erm o tt , Se th

D u b in , all individually and on behalf o f all other persons

similarly situated, Plaintiffs-Appellants,

— against—

N elson A. R ockefeller , Governor of the State o f New

York, Louis J. L e f k o w it z , Attorney General o f the

State of New York, Ca r o lin e K. S im o n , Secretary of

State of the State o f New York, and D e n is J. M a h o n ,

Jam es M. P ow er , Jo h n R. Crew s and T h o m a s Mal-

lee , Commissioners of Election constituting the Board

of Elections of the City o f New York,

Defendants-A ppellees,

— and—

A dam C layto n P o w ell , J. R aym o n d Jones , L loyd E.

D ic k e n s , H u l a n E. Ja c k , M a r k S o u t h a l l and A n

ton io M endez ,

Defendants-Intervenors- Appellees.

O n A ppeal from t h e U n ited States D istr ic t C ourt

for t h e So u th e r n D istrict of N ew Y ork

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Opinion Below

The three separate opinions of the three-judge District

Court (Appendix A, infra) are reported at 211 F, Supp.

460.

2

Jurisdiction

A three-judge District Court was convened pursuant

to 28 U. S. C. §§ 2281 and 2284. On November 26, 1962

the Court entered a judgment dismissing the complaint. A

Notice of Appeal was filed in the District Court on Janu

ary 23, 1963 (R. 531-33). Jurisdiction of this Court to

review the judgment below is conferred by 28 U. S. C.

§ 1253.

Questions Presented

1. Whether appellants sustained their burden of prov

ing that the portion of Chapter 980 of the 1961 Laws of

the State of New York which delineates the boundaries of

the Congressional districts in Manhattan Island segregates

eligible voters by race and place of origin in violation of

the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment and in violation of the Fifteenth Amend

ment.

2. Whether a statute which segregates persons by

race or place of origin may be declared constitutional on the

ground (a) that no proof of specific harm to the individuals

subject to the statute has been adduced at trial or (b ) that

the segregation is benign in its effect.

3. Whether plaintiffs attacking the constitutionality

of a state statute must, in addition to proving that the

statute has the demonstrable effect of segregating persons

by race or place of origin, also prove that the “ motive” of

the legislature was to produce that effect.

4. Assuming, arguendo, that both effect and motive

must be shown (a ) whether plaintiffs’ burden of proof is

greater than that required in the usual civil case, and (b )

whether a court may sustain the constitutionality o f the

3

statute by inferring an alternative legislative motive re

garding which there is no evidence in the record and which

is not a proper subject of judicial notice.

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved

The Constitutional provisions and statutes involved are

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments to the United

States Constitution, 2 U. S. C. § 2 (a ), 42 U. S. C. §§ 1983

and 1988, 28 U. S. C. §§ 1343, 2201, 2202 and 2281, and

Chapter 980 of the 1961 Laws of New York. The pertinent

provisions of 2 U. S. C. § 2 (a ) and Chapter 980 are set

forth in Appendix B, infra.

Statement

On November 9, 1961, the Joint Legislative Committee

on Reapportionment recommended to an extraordinary ses

sion of the New York State Legislature a statute redraw

ing the boundaries of the Congressional districts of the state

in accordance with the 1960 Federal census, as required by

2 U. S. C. § 2 (a ), New York State Legislative Document

No. 45 (1961), set forth in Appendix B, infra. No hear

ings were held and no debates recorded, and the statute

was passed without change and signed by the Governor

on the next day. N. Y. Sess. Laws, Extraordinary Sess.

1961, c. 980 §§ 110-12.

On July 26, 1962, appellants filed a civil complaint pur

suant to the Civil Rights Act, 42 U. S. C. §§ 1983 and 1988,

28 U. S. C. § 1343, in which they challenged that portion of

the statute which delineates the boundaries of the four Con

gressional districts which are wholly contained in, and

comprise all of the districts in, New York County (the is

land or borough of Manhattan). Appellants are residents

and registered voters in each of these four districts. The

appellees named in the complaint are various state and city

4

officials charged with the administration o f the statute. The

complaint alleges that the challenged portion of the statute

segregates eligible voters in Manhattan on the basis o f race

and place of origin in violation of the Due Process and

Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

and in violation of the Fifteenth Amendment. The com

plaint seeks a judgment pursuant to 28 U. S. C. § 2201 de

claring the challenged portion of the statute unconstitu

tional and restraining the defendants in the enforcement

thereof and, in the event such declaration does not lead to

corrective legislation, additional equitable relief.

On July 31, 1962, on motion of appellants and after

hearing, Feinberg, D J. determined that a three-judge court

should be convened pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §§ 2281 and

2284.

At the opening o f the trial before the three-judge court,

Adam Clayton Powell, the then incumbent Congressman

from the pre-1961 18th Congressional District, and five

other individuals, alleging inter alia that “ Negroes and

Puerto Ricans now control” one of the four districts in

Manhattan, which might be affected by a judgment in the

case, were permitted to intervene as defendants.

During the trial, appellants presented evidence in the

form of charts, statistics and expert testimony, showing

the boundaries of the four districts in Manhattan and the

white and non-white and Puerto Rican* population** within

*The non-white and Puerto Rican classification derives from the

U. S. Census breakdown (R. 52-54) and the classification used by

New York City agencies. See N. Y. C. Board of Education, Toward

Greater Opportunity, 155 (1960). Puerto Ricans in New York City

are “ an easily identifiable group [requiring] the aid of a Court in

securing equal treatment under law . . .” Hernandez v. Texas, 347

U. S. 475, 478 (1954).

**Total population rather than eligible voters, residents, or other

classification, was selected because the Constitution and Congress re

quire Congressional districting on the basis of total population. U. S.

Constitution Art. I, § 3; Fourteenth Amendment § 2 ; 2 U. S. C.

§ 2(a).

5

those boundaries. Certain of appellants’ trial exhibits are

set forth in Appendix C.*

Appellants’ evidence showed that the number of Con

gressional districts in Manhattan was reduced by the 1961

statute from 6 to 4, thus requiring a redrawing of bound

aries and an increase in the population of the remaining

four districts. Appellants’ uncontroverted evidence also

showed as follows:

—-The total population of Manhattan Island is 37.7%

non-white and Puerto Rican (Pltfs.’ Exh. 3).

— The first o f the four districts drawn by the statute

(the 17th) contains a population which is 94.9%

white non-Puerto Rican, was carved out of the center

of the Island, has an irregular 35-sided configuration

and is the least populous of the four districts (P ltfs.’

Exhs. 2B and 3).

— The next district drawn by the statute (the adjacent

18th) contains a population which is 86.6% non-white

and Puerto Rican and is the second least populous

district (Pltfs.' Exh. 3).

— The boundary between the 17th and 18th is a 13-sided

step-shaped configuration which fences a maximum

number o f non-whites and Puerto Ricans out of the

17th and into the 18th (R . 99-108).**

*It should be noted that Pltfs.’ Exh. 4 does not precisely reflect

the racial distribution around the borders of the 17th District. The

shadings in the Exhibit cover entire census tracts, whereas the

boundaries of the 17th cut through 16 such tracts. As shown by the

testimony, most of the non-whites and Puerto Ricans in the cut tracts

are excluded from the 17th (R . 95-121).

**One exception is an area retained in the 18th containing 10,507

persons, of whom less than 4.9% are non-white and Puerto Rican.

However, a public housing project, authorized in May of 1959, is now

being constructed in this area (Pltfs.’ Exh. 7 ). Such projects in

New York City have an average non-white and Puerto Rican oc

cupancy of 73.4% (Pltfs.’ Exh. 7).

6

— The remaining two districts, which fill out the rest of

the Island, are approximately equal in total population

and racial composition, each containing just over 70%

white non-Puerto Ricans and just under 30% non

whites and Puerto Ricans (Pltfs.’ Exh. 3).

—-The boundaries of these remaining two districts are

drawn so as to maximize the predominantly white

non-Puerto Rican character of the 17th and the non

white and Puerto Rican character o f the 18th (R.

108-119 and Pltfs.’ Exhs. 4, 4A and 4B ),

— The 17th could not be expanded in any direction so as

to make it reasonably equal in population to the other

districts, nor could its boundary lines be significantly

straightened, without incorporating heavy concentra

tions of non-whites and Puerto Ricans (R. 99-119

and Pltfs.’ Exhs. 4, 4A and 4B ).

—-All but 3.1% of the Island’s non-whites and Puerto

Ricans are included in districts in which their votes

are 12-15% less valuable than those of the residents

of the 17th (P ltfs.’ Exh. 3).

— As a result of the three redistricting acts since 1911,

the 17th has been altered from a rectangular con

figuration to its present 35-sided irregular shape

(Defts.’ Exhs. C-H, R. 595-600).

— The two geographical areas added to the 17th by the

1961 statute were the two remaining areas in Man

hattan with the highest concentrations of white non-

Puerto Rican population, an average of approxi

mately 98% (R. 123-25 and Pltfs.’ Exh. 4B).

— In adding one all white non-Puerto Rican housing-

project (Stuyvesant Town) to the 17th, an adjacent

area containing a non-white Puerto Rican population

7

of 12.2% was omitted, thus leaving an inexplicable

loop in the boundary of the 17th and increasing its

irregular configuration* (R. 143-44 and Pltfs.’ Exh.

4B ).

— The one area dropped from the 17th by the 1961

statute was the area of highest concentration of non

whites and Puerto Ricans (44 .5% ) remaining in the

district at the time of the adoption of the statute

(R. 139-40).

— The new 17th created by the 1961 statute contains

almost 50% more persons than the old 17th, but the

percentage of non-whites and Puerto Ricans in the

district was reduced from 6.6% to only 5.1% (R. 123,

179-80).

—ETone of three hypothetical divisions of the Island into

four districts on a logical basis, using natural bound

aries or well known streets and avenues, produce con

centrations of whites on the one hand and Negroes

and Puerto Ricans on the other which even approach

the concentrations achieved by the statute (Pltfs.’

Exh. 6 and R. 142-48).

At the close of appellants’ case, no evidence was offered

either by the appellee state officials or by the intervening

appellees. The appellee state officials alleged no affirmative

defenses. The intervening appellees failed to introduce

evidence in support of the affirmative defenses alleged in

their pleading, and, because there was no evidence in the

record to support them, the court below refused to consider

*Stuyvesant Town is 99.5% white non-Puerto Rican (R . 124-25

and Pltfs.’ Exh. 4B) under sanction of the decision in Dorsey v.

Stuyvesant Town, 299 N. Y. 512 (1949).

8

or to pass upon these alleged defenses. (Appendix A, infra,

pp. 22a-23a).

In dismissing the complaint, the three-judge court di

vided two to one, and each of the judges filed a separate

opinion.

Judge Moore took the position that racially segregated

voting districts are constitutional, at least absent a showing

o f serious underrepresentation or other specific harm to the

individuals concerned. He stated that plaintiffs “ must show

more than a mere preference to be in some other district

and associated for voting purposes with persons of other

races or other countries of origin” (Id, pp. lO a-lla) and

noted that “ plaintiffs have not even shown that their vot

ing status will be changed in any way” (Id. at p. 15a).

Judge Moore also took the position that segregated vot

ing districts could be constitutionally justified, or even con

stitutionally required, because they may enable persons of

the same race or place of origin “ to obtain representation in

legislative bodies which otherwise would be denied to them”

(Id. at p. 17a).

Even if segregated voting districts could violate the

Constitution, Judge Moore was of the opinion that they

could be unconstitutional only if the legislature’s “ motive”

was to create such districts; that plaintiffs must introduce

proof of this “ motive” ; and that, in this case, no such proof

was tendered by the plaintiffs (Id. at pp. 4a, 10a, 11a,

14a, 15a).

Judge Feinberg disagreed with Judge Moore’s view that

segregated voting districts are constitutional absent a show

ing of specific harm, stating that the “ constitutional vice

[is] the use by the legislature of an impermissible standard

and the harm to plaintiffs that need be shown is only that

such a standard was used” (Id. at p. 18a). Judge Fein-

berg also disagreed with the view that segregated districts

9

could be constitutionally justified by alleged advantages to

persons of a particular race or place of origin. In Judge

Feinberg’s opinion, the Constitution is “ color-blind,” and

“ good” segregation is as repugnant as “ bad” segregation

(Id. at p. 20a).

However, Judge Feinberg agreed that plaintiffs must

show a legislative “ motive” or “ intent” to segregate as a pre

requisite to a finding of unconstitutionality (Id. at pp. 20a,

23a). Moreover, Judge Feinberg believed that plaintiffs

have a “difficult burden” to meet in attacking the constitu

tionality of a state statute (Id. at p. 20a), and that plain

tiffs had not sustained their “ difficult burden” of proving

an unconstitutional legislative motive in this case. Although

plaintiffs’ evidence, in his view, “ might justify” a finding

o f a legislative motive to segregate, he rejected such a find

ing on the ground that “ other inferences . . . are equally or

more justifiable” (Id.) The only such inference specifi

cally cited by Judge Feinberg was that the legislature

intended to classify persons by “ social and economic back

ground,” (Id. at p. 24a), an inference regarding which there

was no evidence whatever.

In his dissent, Judge Murphy agreed with Judge Fein

berg as to the applicable constitutional standards. But on

his view of the record, the plaintiffs carried their burden

of proving that “ the legislation was solely concerned with

segregating white and colored and Puerto Rican voters by

leaving colored and Puerto Rican citizens out of the 17th

District and into a district of their own (the 18th)” (Id.

at p. 2 8 a ); that the legislation had effected “ obvious segre

gation” ; and that the statute constituted a “ subtle exclusion”

o f Negroes from the 17th and a “ jamming in o f colored

and Puerto Ricans into the 18th or the kind of segregation

that appeals to the intervenors” (Id. at 32a). Accordingly,

Judge Murphy thought plaintiffs had met their burden of

proving segregation within Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S.

10

475, 479-81 (1954), and, in the absence of any proof by

defendants or intervenors, were entitled to a judgment de

claring the statute unconstitutional in violation of the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Questions Presented Are Substantial

The judgment and opinions below reflect an impermis

sible reading of the record in this case as well as the applica

tion of novel and improper Constitutional standards. If

allowed to stand, unreviewed by any appellate court, they

will not only continue the segregated pattern of political life

in Manhattan and leave legislatures everywhere virtually

free from Constitutional restraint in the creation of seg

regated voting districts, but they will also establish un

desirable precedents and create confusion in segregation

cases generally. Specifically, the judgment and opinions

below (a ) would permit unbridled segregation unless specific

harm to the individuals involved could be shown, (b ) would

sustain segregation deemed to have a benign effect or to be

prompted by an alternative legislative “ motive” , (c ) would

impose a virtually unachievable standard of proof upon

plaintiffs in segregation cases, and (d ) would permit courts

to uphold segregation statutes by drawing inferences com

pletely outside the record.

1. The record in this case, which may be reviewed de

novo here,* clearly shows that the challenged portion of the

*The court below made no findings of fact. The facts are so

' “intermingled” with the law that de novo review is warranted under

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. S87 (1935) and Watts v. Indiana, 338

U. S. 49 (1949). Moreover, the critical facts in the record are

in documentary rather than testimonial form and, because witness

demeanor is thus immaterial, may be reviewed de novo here, Orvis v.

Higgins, 180 F. 2d 537, 539 at A . 6 (2d Cir. 1950), cert. den. 340

U. S. 810. Especially since this Court is the only appellant tribunal

which may review the record, de novo review is warranted.

11

statute segregates voters by race and place of origin. The

legislation has carved out of the middle of Manhattan

Island one virtually all-white district and one virtually all

non-white and Puerto Rican district. Without further

shrinking the already under-sized 17th and 18th districts,

the legislature could not have drawn the district lines so as

to create a more segregated pattern— that is, a single dis

trict with a higher percentage of white non-Puerto Ricans

(94 .9% ) and another with a higher percentage o f non

whites and Puerto Ricans ( 86.6% ).

The record thus shows, as judge Murphy found, (a )

that segregation exists in fact and (b ) that this segregation

was purposefully created by the legislature-—assuming such

purposefulness is an issue in the case, which appellants

deny, infra pp. 14-15.

Because of his view of the law, Judge Moore did not

find it necessary to review the facts in detail. Judges Fein-

berg and Murphy, who did, came to directly contradictory

conclusions. Judge Feinberg’s conclusion that segregation

was not proved rests upon five erroneous assumptions.

In the first place, Judge Feinberg assumes that the 1961

statute expanded the 17th district in a “ logical fashion”

(Appendix A, infra, p. 21a). This assumption ignores the

fact that two areas were inexplicably omitted: the area

bounded by 98th and 100th Streets and Fifth and Madison

Avenues, with a population 44.5% non-white and Puerto

Rican, and the area bounded by 19th and 14th Streets and

Third and First Avenues, with a population 12.2% non

white and Puerto Rican. The latter area is more logically

contiguous to the old 17th than the adjoining all white

non-Puerto Rican Stuyvesant Town (bounded by 19th

Street, First Avenue, 14th Street and the East River)

which was added. Omission of these two areas results in

12

five additional zigzags in the boundary of the 17th district,*

and their inclusion would have brought the under-sized

17th closer (by 7,489 persons) to the statewide and county

wide average.

Secondly, Judge Feinberg assumes that “ many combin

ations of possible Congressional district lines, no matter

how innocently or rationally drawn, would result in com

parable figures” (Id. at p. 23a). There is no support what

ever for this assumption; indeed, the record shows quite the

contrary— namely, that short of further reducing the size

of the 17th or 18th districts, it would be impossible to create

one district with a higher percentage of non-whites and

Puerto Ricans and one district with a higher percentage of

whites.

Thirdly, Judge Feinberg assumes that only the changes

effected by the 1961 statute are relevant (Id. at pp. 20a-

21a). This assumption ignores the possibility, which appel

lants assert to be the case, that the prior boundaries of the

districts were also unconstitutional and that the 1961

changes merely perpetrated and exacerbated that un

constitutionality.

Fourthly, Judge Feinberg apparently assumed that

plaintiffs in a case challenging the constitutionality of a

state statute have a burden o f proof ( “ difficult burden” )

which is greater than that imposed upon plaintiffs in an

ordinary civil case. That assumption was legally erroneous

(see infra pp. 15-17).

Finally, Judge Feinberg assumes that proof of legisla

tive “ motive” is a prerequisite to unconstitutionality and

that plaintiffs must prove such “ motive” as part of their

affirmative case, even in the absence o f allegations and proof

*The reduction in total zigzags, emphasized by Judge Feinberg,

results primarily from moving the 17th’s eastern boundary over to

the East River as part of its expansion required by reduction of the

Island’s districts from six to four. The upper East Side area thus

added had become virtually all-white non-Puerto Rican (97.3% ) at

the time the 1961 statute was adopted (R. 123-25).

13

thereof by the defendants. This assumption was also

legally erroneous, infra pp. 14-15.

Shorn of these erroneous assumptions, Judge Feinberg’s

conclusion becomes untenable, and Judge Murphy’s view of

the record must be adopted.

2. Judge Moore’s opinion denies that segregated vot

ing districts are unconstitutional absent proof o f dilution

of voting rights or other specific harm to the persons in

volved. This view raises an important question of Consti

tutional law, applicable in segregation cases of every variety.

Although the opinion of the court in Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), noted that placing Negro

students in separate schools might be harmful to the stu

dents involved, the Court’s later decisions outlawing racial

segregation in public parks, buses and golf courses -were

per curiam opinions citing Brown without a suggestion of

specific injury to the individuals concerned. Although two

Justices have apparently taken the position that segregated

voting districts are unconstitutional, without a further

showing of or dilution of voting power*, the issue has not

been passed upon by this Court. If Judge Moore’s opinion

is allowed to stand, the states will be free to erect “ separate

but equal” voting districts and other governmental units.

3. Judge Moore adopts the intervenor’s argument that

segregated voting districts may be sustained if they benefit

a particular racial group. This “ benign quota” argument

is in conflict with the decision in Progress Development

Corp. v. Mitchell, 182 F. Supp. 681 (N. D. 111. 1960), rev’d

on other grounds, 286 F. 2d 222 (7th Cir. 1961), Note, 70

Yale L.J. 126 (1960). And see Bittker, The Case o f the

Checker Board Ordinance, 71 Yale L.J. 1387 (1962). The

“ benign quota” issue, which is dramatically presented by

*See Mr. Justice Douglas in Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186, 244

(1962) and Mr. Justice Whittaker in Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364

U. S. 339, 349 (1960).

14

this case, is emerging as one o f the most important in racial

litigation o f all kinds.

4. The prevailing judges, and probably Judge Murphy

as well, assert that a showing of legislative “ motive” is a

prerequisite to a finding of unconstitutional segregation.

According to this view, a state practice or statute which

has the effect of segregating persons on grounds of race

or place o f origin could be constitutionally justified if it

were shown, by legislative history or otherwise, that this

effect was achieved inadvertently in the pursuit o f a dif

ferent objective. This is indeed a novel doctrine of far-

reaching importance in segregation cases of all kinds. If

some legislative motives can overcome the effect of racial

segregation, can any such motive suffice or only alterna

tive motives which are deemed especially laudable? How

does a court divine the legislative motive, especially when,

as here, there is no relevant legislative history? Are not

legislatures, like individuals, presumed to intend the natural

consequences of their acts? And is there not a danger, if

legislative motive to segregate must be shown in order to

prove a case of segregation, that legislative history will

be manufactured, or, as here, avoided, thus leading courts,

especially this Court, into the frequent necessity of imply

ing motives or questioning the sincerity of individual legis

lators’ expressions ?

The Court below cited no authority for its novel view

that plaintiffs, in addition to showing effect, must also show

legislative motive. It is of course true that legislative pur

pose may be relevant when the effect of a statute challenged

as unconstitutional on its face may not be shown without

reference to legislative purpose, Bush v. New Orleans

Parish School Bd., 188 F. Supp. 916 (1960), aff’d, 365

U. S. 569 (1961). But when effect may be readily proved,

15

the Court has focused solely on effect without inquiring into

the motive of the legislature. See Gomillion v. Light foot, 364

U. S. 339, 341, 347-8 (1960), where the opinion refers to

“ effect” and “ result” rather than motive or purpose. Where

an effect o f segregating has been shown, an alleged motive

to achieve some other objective has been rejected as irrele

vant, see, e. g., Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584, 588

(1958) (purpose to preserve “ local tradition” rejected).

And see Branche v. Board, of Education, 204 F. Supp. 150

(E. D. N. Y. 1962), where purpose was held irrevelant

once an effect to segregate was shown.

And in cases where state action has been held to have the

effect of abridging the rights o f a racial minority under the

First Amendment, that action is unconstitutional even if

such abridgement was “ unintended” and even if the purpose

of the action was to protect a very real state interest, e. g.,

N AACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, 461 (1958); N A A C P

v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 439 (1963).

Nowhere in the cases is there justification for the view

advanced by Judge Feinberg in this case that a legislative

motive to classify persons according to “ social and eco

nomic background” could constitutionally justify a statute

which has the demonstrable effect of segregating persons

by race or place of origin, or Judge Moore’s apparent view

that any alternative motive could justify the statute.

5. Whether or not the Court below was correct in hold

ing legislative motive a relevant factor where plaintiffs seek

to prove that a state statute unconstitutionally segregates,

it was certainly incorrect in the crucial matter of the

standard of proof to be applied in such cases.

As indicated in cases like Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S.

370, 397 (1880), Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587, 591,

597-98 (1935), and Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475,

16

480-81 (1954), plaintiffs attacking the constitutionality of

state action on the ground that it produces segregation make

out a prima facie case by showing that such segregation does,

in fact, exist— in other words, by demonstrating the effect of

the action. It then falls on those defending the action to

attempt either to rebut the plaintiff’s proof, or to offer some

justification for the forbidden effect. Thus in such cases

traditionally, as in civil cases generally, 2 Moore’s Fed.

Pract. 1841-62 (1953), matters not within the plaintiff’s

prima facie case are reserved for affirmative defenses which

must be pleaded and proved by defendants. Finally, in these

cases, as in all civil cases, plaintiffs must prove their case

only by a preponderance of the evidence.

The effect o f Judge Feinberg’s opinion is to alter these

rules. His statement that appellants have a “ difficult bur

den” in attempting to prove the unconstitutionality of the

challenged statute indicates that he imposed a standard of

proof higher than preponderance o f the evidence. And the

consequence of his unsatisfactory answers to Judge

Murphy’s question: “ What more need plaintiffs’ prove?” is

to require plaintiffs, in order to be certain of proving a prima

facie segregation case, to assume the burden of rebutting

every theoretically possible motive for the challenged statute,

even in the absence of allegations and proof of such motive

by defending state officials. The latter is an especially un

reasonable burden when, as here, there is no relevant legis

lative history.*

In the adversary system neither the plaintiffs nor the

Court should be obliged to speculate regarding legislative

motive, particularly in constitutional litigation in which the

resources of the state, which is in the best position to aduce

*In this case the only legislative history is the legislative committee

report, Appendix B, pp. 9b-14b, infra. Although this report asserts

that the committee was motivated by a desire to achieve substantial

numerical equality, it contains nothing which would explain the con

figurations of the Manhattan districts.

17

evidence of legislative motive, are arrayed against the pri

vate litigant. Once the plaintiffs have made an adequate

showing, the Court has a right to be informed by the state

regarding the basis of the statute, and it may enforce that

right effectively only if, in the absence of allegations and

proof by defendants, it is prepared to give judgment to the

plaintiffs.

6. The judgment below rests upon Judge Feinberg’s

view that inferences regarding legislative motive, other

than that drawn by appellants, are possible. Judge Feinberg

cited only one specific example of such an inference: that

the challenged portion of the statute is based upon “ social

and economic background.” However, there is nothing in

the record regarding the social and economic background

of the population of the Island, and such a matter surely is

not a proper subject of judicial notice. A rule permitting the

Court to speculate beyond the record in order to justify state

legislation challenged as creating racial segregation is surely

improper and could lead to widespread abuse.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, probable jurisdiction of this

appeal should be noted and a hearing on the merits should

be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Ju s t in N. F eld m an

415 Madison Avenue

New York 17, N. Y.

Jerome T . O rans

10 East 40 Street

New York 16, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellants.G eorge M. C oh en

E lsie M. Q u in l a n

O f counsel

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A

Opinion

la

U N ITED STATES D ISTRICT COURT

S o u th e r n D istr ic t of N e w Y ork

C iv il 62-2601

Before: M oore, C.J., and M u r p h y and F ein berg , D.JJ.

M oore, Circuit Judge

Plaintiffs bring this action allegedly “ to redress the dep

rivation, under color of the law of the State of New York,

of rights, privileges and immunities secured to the plaintiffs

under the Constitution and laws of the United States and

to declare unconstitutional that portion o f the State statute

in question which deprives the plaintiffs o f their rights,

privileges and immunities” . More specifically, they claim

that the action arises under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

amendments of the Constitution of the United States, the

Civil Rights Act (42 U. S. C. §§ 1983, 1988 and under

28 U. S. C. §§ 1343, 2201, 2202 and 2281). The relief

sought is that a three-judge constitutional court hear and

determine the case; that such portion o f Chapter 980 of

the 1961 Laws of New York as describes the boundaries

of the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th Congressional Districts

be declared unconstitutional; that a preliminary injunction

issue against the primary election on September 6, 19621

and the general election on November 6, 1962 on the basis

o f such boundaries; that a permanent injunction issue; that

unless a redistricting of such four districts be made, there

be an election at large in New York County for the four

Congressional seats in said County; and that absent such

Appendix A

1Request withdrawn during trial

2a

legislative action, the court appoint a special master to re

define the boundaries of the four districts in question.

The plaintiffs allege that they reside and are registered

voters in these respective districts and that each brings the

action on his own behalf and all other residents of the re

spective districts. They ask, because of their claim that

they “ fairly and adequately represent” these other regis

tered voters, that this be considered a “ class suit” .

The portion of the statute (Chap. 980) under attack

establishes, according to plaintiffs, “ irrational, discrimina

tory and unequal Congressional Districts in the County of

New York and segregates eligible voters by race and place

of origin” . Plaintiffs charge that the 17th Congressional

District was “ contrived” to exclude “ non-white citizens and

citizens of Puerto Rican origin” and that the 18th, 19th

and 20th districts “ have been drawn so as to include the

overwhelming number of non-white citizens and citizens of

Puerto Rican origin in the County of New York” . They

also assert that the 17th is “ over-represented” and the 18th,

19th and 20th are “ under-represented’ ’ .

This situation, plaintiffs say, has existed for many

years, that there had been repeated and energetic efforts to

seek legislative correction of the abridgement of plaintiffs’

constitutional rights but that they have been o f no avail

“ because o f the existing unconstitutional apportionment of

the Legislature of the State of New York” ; that the Legis

lature in successive statutes has redrawn the district bound

aries in accordance with shifts in non-white and Puerto

Rican populations and that the 17th has a population 12%

less than the 18th, 15.4% less than the 19th and 14% less

than the 20th. These allegations have been set forth at some

length because of the necessity of ascertaining whether they

have been established by the proof.

Appendix A

3a

At the opening of the trial six individuals, Adam Clay

ton Powell, J. Raymond Jones, Lloyd E, Dickens, Hulan E.

Jack, Mark Southall and Antonio Mendez, by counsel moved

to intervene. They were represented to be duly enrolled

members of the Democratic Party and district leaders of

the area comprising the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th Assembly

Districts. Adam Clayton Powell, a Negro, is now serving as

Congressman from the (pre-1961) 18th Congressional Dis

trict. Intervention was granted. The intervenors thereupon

served their answer as intervening defendants alleging six

defenses which, amongst other matters, denied that plain

tiffs represented the class to which the intervenors belong

and that the redistricting of the four Congressional Dis

tricts in question deprived plaintiffs of their constitutional

rights. As affirmative defenses they alleged, in substance,

that the test for Congressional representation is based on

population rather than race, that the Republican-controlled

Legislature drew the new district boundaries “ along parti

san political lines rather than racial lines” to “ cut out as

many democrats as they possibly could” , that judgment as

sought by plaintiffs would place in jeopardy the constitu

tional rights of Negroes and Puerto Ricans to representa

tion in Congress, that a County-wide election at large would

“ deprive Negroes and Puerto Ricans and other minorities

o f fair representation and equal protection under the law” ,

that this is not a proper class action, that “ the real party-

in interest in this law suit is the Democratic County Com

mittee of the County of New York” , that said Committee

o f which intervenors are members never authorized or

approved plaintiffs’ action, and that plaintiffs are estopped

from bringing this action because o f their failure to com

mence it until some time after June 21, 1962 the initial

date for nominating petitions.

Appendix A

4a

On the trial, plaintiffs presented certain statistical ma

terial gathered from the 1960 census figures and various

maps of Manhattan Island (New York County), At the

request of the court, counsel for the Attorney-General sub

mitted maps showing the many Congressional district

changes since 1911. No proof was offered by any party

that the specific boundaries created by Chapter 980 were

drawn on racial lines or that the Legislature was motivated

by considerations of race, creed or country of origin in

creating the districts. Plaintiffs rely entirely upon their

analyses and version o f certain statistics and would impute

to the Legislature the inferences they draw therefrom.

After the Eighteenth Decennial Census (1960) had

been taken, the President according to law (2. U. S. C. 2a)

transmitted to the Congress a statement under date of

January 10, 1961 showing the number of persons in each

State and “ the number of Representatives to which each

State would be entitled under an apportionment of the exist

ing number of Representatives by the method of equal pro

portions. The statement disclosed a total population of

179,323,175 for the United States and 16,782,304 for New

York State. Apportioning the 435 Congressional Repre

sentatives amongst the States, New York became entitled

to 41 instead of the 43 previously alloted under the 1950

census.

As a result of this required change, the joint Legislative

Committee on Reapportionment submitted to the Second

Extraordinary Session o f the New York Legislature on

November 9, 1961 its interim report wherein it stated the

need for legislative action, namely, that because of the re

duction in Congressional seats all the Representatives of

the State would have to be elected at large “ unless new dis

Appendix A

5a

tricts not exceeding in number the number of Representa

tives apportioned to the state shall be created” . The Com

mittee briefly reviewed the history of the Congressional

district system as follows:

In the early days of the Republic, some of the states

elected by districts and some at large. The desire

for local representation, however, gradually led to

the adoption o f the district method by the majority

of the states. By 1842, o f the states entitled to more

than one Representative, 22 were electing their Rep

resentatives by districts, and only 6 were electing

at large.

As the practice of electing by districts became firmly

established. Congress, in connection with the suc

ceeding apportionments of Representatives among

the states, enacted statutes setting standards for the

election of Representatives within the several states.

In connection with each decennial census from 1840

to 1910, with the exception of the census of 1850,

Congress enacted a law of this character. The last of

these laws was the Act of August 8, 1911 (2 U. S.

C. A. § 2) (37 Stat. L. 13), which provided that dis

tricts should consist of contiguous and compact ter

ritory and contain as nearly as practicable an equal

number o f inhabitants. There was no apportionment

Act after the census o f 1920. The permanent act of

June 18, 1929 (46 Stat. L. 13), as originally enacted

and as amended by the Act of April 25, 1940 (2

U. S. C. A. § 2a) (54 Stat. L. 162), contained no

standards for the creation o f districts. In Wood

against Broom, 53 S. Ct. 1, 287 U. S. 1, 77 L. Ed.

131, a case involving the creation of Congressional

districts after the apportionment under the Act of

1929, the Supreme Court held that the provisions of

the Act o f 1911 requiring that districts be of con

tiguous and compact territory and, as nearly as prac

Appendix A

6a

ticable of equal population, applied only to districts

to be formed under the Act o f 1911. In Cole grove

against Green, 66 S. Ct. 1198, 328 U. S. 549, 90 L.

Ed. 1432, Plaintiffs urged that an act creating Con

gressional districts substantially unequal in popula

tion be held invalid as violating the Fourteenth

Amendment o f the Federal Constitution. In that

case the Supreme Court in its opinion, after citing

with approval Wood against Broom, supra, stated

that it was not within the competence of the court

to grant the relief asked by the Plaintiffs.

Since the above cases, various bills have been intro

duced in Congress to provide standards to be fol

lowed by the state legislatures in creating Congres

sional districts. None o f those bills has been enacted

into law. At the present time, therefore, there are

no Federal standards binding upon the states in

creating Congressional districts, and there are no

such standards to be found in the Constitution of

statutes of New York.

The Committee then set forth the standards used by it

in preparing its proposed bill, stating:

In the absence of Federal and State constitutional

and statutory standards governing the creation of

Congressional districts, your Committee has been

obliged to determine for itself what, if any, such

standards should be adopted by it in the preparation

of a bill to be recommended to your Honorable

Bodies. It is the conclusion of your Committee that

the most important standard is substantial equality

of population.

While exact equality of population is the ideal, it is

an ideal that, for practical reasons, can never be

attained. Some variation from it will always be

necessary. The question arises as to what is a per

missible fair variation.

Appendix A

7a

Your Committee has examined reports of Committee

hearings on bills introduced in Congress bearing

upon this subject, and reports and publications of

authorities on this subject. Variations of from ten to

twenty per cent from average population per district

have been suggested from time to time. After con

siderable study, your Committee decided that a maxi

mum variation of fifteen per cent from average

population per district, the variation recommended

by the American Academy of Political Science and

endorsed by former President Truman, would pre

serve substantial equality of population and permit

consideration to be given to other important factors

such as community of interest and the preservation

of traditional associations.

In addition to keeping the districts in its proposed

bill within the maximum of the fifteen per cent varia

tion from average population per district, your

Committee has also created proposed districts of

contiguous territory and has endeavored to preserve

the several metropolitan areas of the state either in

single districts or, where large populations made that

impossible, in contiguous and closely allied districts.

New York City was singled out for special comment

as follows:

In an attempt to assist the members o f the Legis

lature in their analysis o f the consideration given

Metropolitan New York by your Committee we

would like to point out that the population of New

York City according to the 1960 Federal decennial

census is 7,781,984. 19 districts have been created

in the City with an average population of 409,578

per district. The remainder of the state has a popu

lation of 9,000,400 and has 22 districts with an aver

age population of 409,109 per district. The total

Appendix A.

8a

population of the state is 16,782,384. Dividing this

population by 41, the total number of Representa

tives, gives an average population per district

throughout the State o f 409,326. A mere inspec

tion of these figures will demonstrate that there has

been no discrimination against New York City in

the proposed bill.

Refining the population figures still further, it is obvious

that New York County (Manhattan) with its population

of 1,698,281 has approximately one-tenth of the total State

population of 16,782,304 and, hence, should have on an

equal proportion basis one-tenth of the 41 Congressional

seats. This it has in being allotted four seats.

Plaintiffs do not question the necessity for the reduc

tion of Congressional districts in the State from 43 to 41

nor the boundaries of the 37 districts outside of New

York County. Inspection of these 37 districts discloses

a variation in population within New York City of from

469,908 in the 12th District (Brooklyn) down to 349,850

in the 15th District (also Brooklyn) and 348,940 in the

24th District (B ro n x ); and in the upstate (in relation to

New York City) and rural areas of from 460,409 in the

30th District comprising the counties of Saratoga, Wash

ington, Warren, Fulton, Hamilton, Essex, Clinton and part

of Rensselaer to 353,183 in the 31st District consisting of

St. Lawrence, Jefferson, Lewis, Franklin and Oswego

counties. An example of a merger of rural and suburban

interests is found in the 25th District where Putnam’s

(rural) population (31,722) is merged with part of West

chester’s (largely suburban) 406,687. Separating the 19

New York City districts from the 22 in the rest of the State,

if the 7,781,984 persons in New York City were equally

divided amongst 19 districts, there should be 409,578 per

Appendix A

9a

sons in each district. The remaining 9,000,000 persons

divided in to 22 districts should provide an average of

409,109 per district.

These figures are thus analyzed because plaintiffs fre

quently employ the words “under-represented” in relation to

the size of the 18th, 19th and 20th districts, namely,

431,330, 445,175 and 439,456, respectively, and “ over-rep

resented” with respect to the 17th district (382,320).

Testing these numbers by taking the Legislative Commit

tee’s “ maximum variation of fifteen per cent from average

population per district” , the largest New York County dis

trict, the 18th, is less than 9% above the average and the

smallest, the 17th, less than 7% below the average. Only

in Kings County is found the widest range of almost 15 %

above and below the mean.2

During the trial the court made every effort to ascertain

the real basis o f plaintiffs’ claim of constitutional violation.

Plaintiffs stated that they intended to prove that the Legis

lature in enacting Chapter 980 of the Laws of 1961 “ segre

gated the voters [in Manhattan] by virtue of race and place

o f origin” . They limit, however, their “ race” to “ non

white” and their “place o f origin” group to Puerto Rico.

Selecting certain catch phrases from one of the Go million

opinions (M r. Justice Whittaker), they argue that the

Legislature intentionally fenced Negro citizens out of the

17th District and fenced them into the 18th, 19th and 20th

2As Mr. Justice Black pointed out in his dissent in Colegrove v.

Green, 328 U. S. 349:

There is not, and could not be except abstractly, a right of

absolute equality in voting. At best there could be only a

rough approximation. And there is obviously considerable lati

tude for the bodies vested with those powers to exercise their

judgment concerning how best to attain this, in full consistency

with the Constitution.

Appendix A

10a

Districts. They ask this court to find an unconstitutional

Legislative intent solely on the basis of their analysis of

the population content of these districts.

At the outset this court (and courts generally) should

be ever watchful that it is not being made the pawn of

warring political factions.3 More than suspicion of this

possibility is created by the pleadings. The intervenors

assert that they are the six district leaders in Assembly

Districts embraced within the Manhattan Congressional

Districts and that the 18th District from which Congress

man Powell is the present representative and others in

“ public office” would be affected by any judgment in favor

of plaintiffs.

Upon the trial no proof was offered which would jus

tify a finding that plaintiffs represented a “ class” ; in fact,

the intervenors’ opposing claim dispels any such conclusion.

Neither plaintiffs nor the intervenors can speak for, or

truly represent the wishes of, some 400,000 persons in

their districts. Each individual, however, is entitled to the

benefits o f constitutional equal protection and due process.

But to receive judicial support for their respective causes,

they must show more than a mere preference to be in some

Appendix A

3In Colegrove v. Green, 328 U. S. 549, Mr. Justice Frankfurter

wrote:

Nothing is clearer than that this controversy concerns matters

that bring courts into immediate and active relations with party

contests.^ From the determination of such issues this Court

has traditionally held aloof. It is hostile to a democratic sys

tem to involve the Judiciary in the politics of the people. And

it is not less pernicious if such judicial intervention in an es

sentially political contest be dressed up in the abstract phrases

of the law.

* * *

To sustain this action would cut very deep into the very being

of Congress. Courts ought not to enter this political thicket.

11a

other district and associated for voting purposes with per

sons o f other races or other countries o f origin.

Plaintiffs’ theories of unconstitutionality are difficult

to pin down. First, they refer to disparity in size between

the districts and have attempted in their own hypothetical

districts to equalize almost exactly the population in each.

They disclaim exact equality as a basis of unconstitutionality

probably because of the history of 2 U. S. C. 2 (a ) and

because of Wood v. Broom, 287 U. S. 1 (1932).

Although plaintiffs obliquely disavow the racial per

centage theory, their statistical argument supports it. They

show that of Manhattan’s 1,698,281 inhabitants the 1960

census lists 1,058,589 or 62.3% as white (apparently all

races and places of origin) and 639,692 or 37.7% as “ non

white and Puerto Rican origin” . Why the census so dis

criminates, plaintiffs were unable to answer except as their

witness said that the census limits races to non-whites and

place of origin to Puerto Rico. Plaintiffs then show that of

the four districts the percentages of non-whites and Puerto

Rican are 3.1%, 58.2%, 19.8% and 18.9% in the 17th,

18th, 19th and 20th Districts, respectively. From these

figures plaintiffs ask this court to conclude as a matter of

law that the Legislature in 1961 drew the district lines so

as to intentionally deprive non-whites and Puerto Ricans

of their constitutional rights. “ Constitutional rights” to do

what still remains unanswered. Plaintiffs apparently want

a higher percentage of non-whites and Puerto Ricans in

the 17th. Their neighbors, the interveners, proclaim with

equal vehemence that such a change would be violative of

their rights to enjoy the redistricting as it now is. They

claim, in effect, that to take a substantial number of non

Appendix A

12a

whites and Puerto Ricans and to place them within the con

fines of a different Congressional district (namely, the

17th) would be an Acadia-like deportation designed to dis

sipate and thus make ineffectual their votes. They assert

that they now have an opportunity to elect persons of

their own race to represent them and their interests to

legislative bodies. Plaintiffs respond that this is of no im

portance.

Finally and before considering the legal problems, if

there be any, a brief review of New York County’s con

gressional districts should be made. A 50-year period has

been selected. In 1911 there were 9 full districts and parts

of 4 other districts in New York County out of a total

of 43 in the State. In 1917 the 1911 apportionment w7as

amended changing the County to 10 full districts and parts

o f 3 others. Rased on the 1910 census, the variation in

the Congressional Districts Nos. 11-22 was slight, ranging

from 204,498 to 219,772. After the 1920 census applying

the 1922 Act, the variation was larger, probably due to

population shifts, the law (from available figures) being

191,645 and the high 317,803. Wider disparity developed

after the 1930 census, the low7 being 90,671 and the high

381,212. After the 1940 census and the State was allotted

45 districts, New York County was given 6 full districts

and part of one other, the population range being from

257,879 to 315,639. Not until after the 1950 census was

New York County allotted self-contained districts, it re

ceiving 6 out of 43 for the State, the smallest district hav

ing a census population of 316,434 and the largest 336,441.

This suit is but one of many throughout the country

seeking to take advantage of the Supreme Court’s decision

Appendix A

13a

Appendix A

in Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186 (1962).4 To inject a racial

angle plaintiffs have added Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364

U. S. 329, and the school segregation cases to support their

thesis. However, the most drastic Procrustean treatment-

will not conform the shape of the present case to the pat

terns o f those cases. Baker v. Carr was simply a decision

that a federal court has jurisdiction to deal with and remedy

such a wide disparity in voting representation as to amount

to a deprivation of due process and equal protection. There

the situation was particularly aggravated because the Ten

nessee Legislature had taken no action to comply with the

state’s own Constitution. A comparable hypothetical state

4Of the cases upon the subject of apportionment which have come

to my attention, four have held the existing state apportionment pro

visions constitutional:

W. M. C. A., Inc. v. Simon, Civil No. 1559, S. D. N. Y.,

Aug. 16, 1962 (Statutory Court) ;

Wisconsin v. Zimmerman, Civil No. 3540, W . D. Wise.,

July 25, 1962 (Statutory Court) (report of Special

Master) ;

Caesar v. Williams, 9 Idaho Capital Report 161 (Sup. Ct.

April 3, 1962);

Maryland Comm, for Fair Representation v. Tawes, 31

U. S. L. Week 2155 (Md. Ct. App. Sept. 25, 1962) (up

per house).

Others have found the apportionment statutes in conflict with the

state constitution:

Sims v. Frink, 205 F. Supp. 245 (M . D. Ala. April 14,

1962) (Statutory Court) ;

Harris v. Shanahan, No. 90,476, Dist. Ct. Shawnee County,

Kan., May 31, 1962;

State ex rel Lein v. Sathre, 113 N. W . 2d 679 (Sup. Ct.

N. D. Mar. 9, 1962) ;

Lein v. Sathre, 205 F. Supp. 536 (D. N. D. May 31, 1962)

(Statutory Court) ;

Mikell v. Rousseau, No. 385, Sup. Ct. Chittenden County,

Vt., May Term, 1962.

See also Start v. Lawrence, Equity No. 2536, 1962 Com

monwealth No. 187, C. P. Dauphin County, Pa., June 13,

14a

of facts would exist had the New York Legislature taken

no action since 1901 when New York City held a high

percentage o f the State’s 37 seats whereas today the City’s

population is only one-tenth of the State’s. But this factual

situation o f non-action does not exist. The Legislature has

taken revising action after each census and at present the

ratio of voter to Representative is, as the Legislative Com

mittee has said, on a “ substantial equality of population”

basis.

The Gomillion case has no application whatsoever.

There some 400 Negro residents of the city o f Tuskegee

who were entitled to all the privileges of city residents in

cluding voting were deliberately disenfranchised from such

1962 (court refused to determine whether the apportion

ment statutes comported with the state and federal con

stitutions until the legislature had time to act).

Still others have held the apportionment provisions invalid under the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment:

Sanders v. Gray, 203 F. Supp. 158 (N . D. Ga. April 28,

1962) ( Statutory Court) ;

Toombs v. Fortson, 205 F. Supp. 248 (N . D. Ga. May 25,

1962) (Statutory Court) ;

Moss v. Burkhart, Civil No. 9130, W . D. Okla., June 19,

1962 (Statutory Court) ;

Baker v. Carr, 206 F. Supp. 341 (M . D. Tenn. June 22,

1962) ( Statutory Court) ;

Maryland- Comm, for Fair Representation v. Tawes, Equity

No. 13920, Cir. Ct. Anne Arundel County, Md., May 24,

1962 (lower house) ;

Scholle v. Hare, Sup. Ct., Mich., July 18, 1962;

Fortner v. Barnett, No. 59965, Ch. Hinds County, Miss.,

1962;

Sweeney v. Notte, C. Q. No. 643, Sup. Ct., R. I., 1962.

Sims v. Frink, 208 F. Supp. 431 (M . D. Ala. 1962) (Sta

tutory Court).

These cases for the most part involve wide disparity in the popula

tion of voting districts.

Appendix A

15a

voting by a wholly irrational drawing of new city boun

daries which did not even slightly veil the obvious purpose

of excluding Negroes as city voters.

The school cases are equally irrelevant. I f it is to be

found as a fact that only in the 17th District is there and

will there be throughout the years a Congressman who

alone can properly speak for the electorate of Manhattan

as their representative further consideration might be given

to these cases. However, both major political parties would

vigorously dispute a finding that a lone Congressman from

New York’s 17th controls or vitally influences all actions

by the Congress, no matter how able any such incumbent

might be.

From various maps and figures plaintiffs ask this court

to find constitutional deprivations. Actually plaintiffs

have not even shown that their own voting status will be

changed in any way. Prior to the reduction of New York

County’s Congressional seats to four, there were six dis

tricts, the 16th through 21st. In eliminating two, the Legis

lature apparently used the existing framework. It enlarged

the 17th substantially on the north cutting into the old 18th

and slightly on the south and it merged the balance of the

old 18th with the 16th. The old 19th, 20th and 21st were

made into two districts extending from the northerly part

o f Manhattan along the west side of the city around the

southerly end of the island and up through the lower east

side. Thus, the general district pattern was somewhat pre

served despite the elimination o f two districts.

No proof was tendered that the Legislature in drawing

the district lines in previous years was motivated or influ

enced by any considerations which have become unconstitu

tional during subsequent years. Plaintiffs wholly failed

to support their allegation of “ repeated and energetic

Appendix A

16a

efforts” to seek legislative correction or that efforts were

unavailing because of unconstitutional apportionment. Any

challenge that correction if needed could not be made be

cause o f the composition of the State legislature is squarely

met by the recent decision in W M CA Inc. et al v. Simon

et al, 61 Civ. 1559, S. D. N. Y., August 16, 1962, wherein

after a trial a three-judge court found with respect to the

apportionment of Senate and Assembly districts that the

apportionment provisions of the State of New York are

rational, not arbitrary, are of substantially historical origin,

contain no geographical discrimination, permit an electoral

majority to alter or change the same and are not uncon

stitutional under the relevant decisions of the United States

Supreme Court. Certainly federal congressional redistrict

ing would not affect New York legislative action and plain

tiffs in this action have not attacked New York’s method of

creating its own Legislature. Nor has any proof been

offered to indicate in any way that the Legislature in its

various congressional boundary enactments from 1901 to

date has redrawn district lines in conformity with non-white

and Puerto Rican population shifts.

This case presents an example of an attempt to apply

theories of completely unrelated situations ( Baker v. Carr,

Gomillion and the school cases). That the effort appears

forced is not surprising. If the Legislature had created two

Congressional districts in Manhattan each consisting of

100,000 persons, one almost wholly of race A and the other

of race B and assigning the balance o f the County to two

districts of 700,000 each, the question of discrimination

might well be raised; but it did not so act.

No citizen of Manhattan, as a result of the legislative

redistricting, has been deprived of his right to vote for the

Appendix A

17a

duly nominated candidates o f the party of his choice and

in the area in which he resides. Wherever areas have to be

divided into districts, there will be voters who may prefer

to vote in districts other than their own but such deprivation

is not a constitutional deprivation. In any large city it is

not unusual to find that persons o f the same race or place

of origin have a tendency to settle together in various

areas. Often this understandable practice enables them

to obtain representation in legislative bodies which other

wise would be denied to them. Where geographic boun

daries include such concentrations there will be a higher per

centage of one race in one district than in others. To create

districts based upon equal proportions of the various races

inhabiting metropolitan areas would indeed be to indulge

in practices verging upon the unconstitutional. Equally un-

contitutional would appear to be plaintiffs’ suggestion that

only in Manhattan should there be an election at large of

its four Congressional Representatives and that the dist

rict system be used elsewhere in the State. Any such legis

lation would definitely tend to abridge the voting status, if

not the actual voting rights, o f residents of Manhattan.

Plaintiffs having failed upon the facts and the law

to establish any violation of their constitutional rights as

a result o f the action of the New York Legislature in en

acting Chapter 980 of the Laws o f 1961, the complaint must

be dismissed. No costs.

F ein berg , D. J .

I concur in the result reached by Judge Moore because

I feel that plaintiffs have not met their burden o f proving

that the boundaries of the new 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th

Congressional Districts were drawn along racial lines, as

Appendix A

18a

they allege. I differ from the opinion of judge Moore,

however, in two major respects.

1. Judge Moore’s opinion in several places implies that

it is necessary for plaintiffs to show not only that the

boundaries of the congressional districts were drawn on

racial lines but also that there was some other dilution or

dimunition of the plaintiffs’ right to vote. I disagree with

this implication. I f plaintiffs had proved that the district

lines were constituted on a racial basis, the fact that plain

tiffs had an undiminished right to vote in such gerryman

dered districts would be irrelevant. The constitutional vice

would be use by the legislature of an impermissible stand

ard, and the harm to plaintiffs that need be shown is only

that such a standard was used. Gomiilion v. Lightfoot, 364

U. S. 339 (1960), and Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186 (1962),

provide support for the view that racially gerrymandered

districts violate the Fifteenth Amendment, which provides

that: “ The right of citizens of the United States to vote

shall not be denied or abridged . . . on account of race, color,

or previous condition of servitude.” In Baker, Mr. Justice

Douglas referred to the Gomiilion case as an instance

“where a federal court enjoins gerrymandering based on

racial lines,” 1 and further stated that:

“ Race, color, or previous condition of servitude

is an impermissible standard by reason of the

Fifteenth Amendment, and that alone is sufficient to

explain Gomiilion v. Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 339.” 2

(369 U. S. at 250 n. 5.

2Id. at 344. But see the concurring opinion of Mr. Justice Whit

taker in Gomiilion where he stated that there was no violation of the

Fifteenth Amendment by racial redistricting as long as the complain

ing voter enjoys the same right to vote as all others in the same dis

trict. Gomiilion v. Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 339, 349 (1960). Under those

circumstances, however, Mr. Justice Whittaker thought there would

be a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Ibid.

Appendix A

19a

Appendix A

It is true that the emphasis in the Gomillion opinion is on

the deprivation o f a pre-existing right to a municipal vote.

However, analysis o f that case indicates that the Negroes

of Tuskegee were free to establish their own separate

municipality merely by filing a petition signed by 25 per

sons.3 The view that racially drawn districts per se would

also violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment finds support in the per curiam decisions o f the

Supreme Court following Brown v. Board o f Educ., 347

U. S. 483 (1954). These cases4 outlawed racial segregation

in public parks, beaches, buses, and golf courses without

any discussion of harm resulting from discrimination in the

use o f those facilities. The issue can be posed by assuming

a state statute which on its face indicated that all Negro

voters would vote in one district and all white voters in

another, with the number of persons in each district ap

proximately equal. I have little doubt that such a statute

would be held unconstitutional, but whether under the

Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendment, or both,5 need not be

decided now, in view of plaintiffs’ failure to prove their

case.

The interveners contend that redistricting along the

lines suggested by plaintiffs would, in effect, jeopardize the

3See Lucas, Dragon In The Thicket: A Perusal of Gomillion v.

Lightfoot, Supreme Court Review 194, 210-11 (1961), where the

author also suggests additional reasons for viewing the case as bar

ring any segregation of voters even absent a technical loss of voting-

rights.

ANe'w Orleans City Park Improvement Ass’n v. Detiege, 358 U. S.

54 (1958); Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 (1956)'; Holmes v.

Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 (19 55 ); Mayor v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877

(1955); Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n, 347 U. S. 971

(1954). See Fay v. New York, 332 U. S. 261, 292-93 (1947). See

also Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475, 478 (1954) ; Nixon v. Hern

don, 273 U. S. 536, 541 (1927).

5Plaintiffs here rely on both Amendments.

20a

“ control” by non-whites and Puerto Ricans of at least one

congressional district. This— the loss o f an alleged advan

tage to the class of voters plaintiffs claim to represent-—is as

irrelevant to the constitutional issue as the need to show

some harm other than that inherent in the drawing o f dis

trict lines on a racial basis. The argument assumes that

under the Constitution there can be “good” segregation

along racial lines as against “bad” segregation.6 With

respect to redistricting, the answer to this is found in Mr.