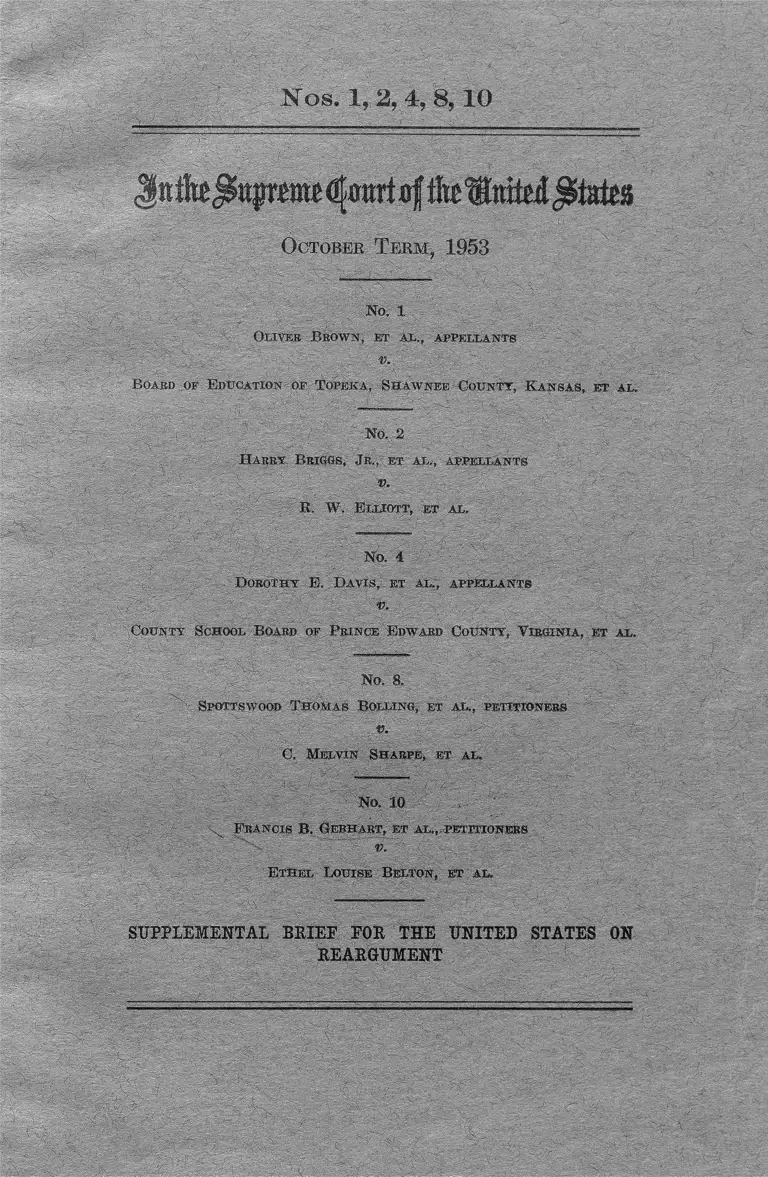

Brown v. Board of Education Supplemental Brief for the United States on Reargument

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Supplemental Brief for the United States on Reargument, 1953. 4572ede1-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8db86215-1745-426d-a77a-d825b3d19725/brown-v-board-of-education-supplemental-brief-for-the-united-states-on-reargument. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

N o s . 1 , . 2 , 4 , 8 , 1 0

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1 9 5 3

No. 1

Oliver Brown, et al., appellants

Board of Education op Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, et al.

No. 2

H arry Briggs, Jr., et al., appellants

v.

R. W. Elliott, et al.

No. 4

Dorothy E. Davis, et al., appellants

v.

County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al.

No. 8.

Spottswood T homas Bolling, et at,., petitioners

v.

C. Melvin Sharpe, et al.

No. 10

N Francis B. Gerhart, et al... petitioners

v.

Ethel Louise Belton, et al.

SUPPLEMENT A l BRIEF FOE THE UNITED STATES ON

EEAEGUMENT

I N D E X

I and II

P®gs

The contemporary understanding of the Fourteenth Amend

ment with respect to its effect on racial segregation in public

schools_______________________ ___________________________ 3

A. Introductory------------------------------------------------------------- 4

1. The reconstruction period-------------------------------- 4

2. Public education in the United States in 1866-_ 8

B. The historical origins and background of the Fourteenth

Amendment_______________________________________ 9

1. The anti-slavery origins of the reconstruction

amendments_______________________________ 9

2. The status of Negroes (legal, economic, and edu

cational) at the close of the Civil War__________ 14

C. The legislative history of the Thirteenth Amendment

and implementing legislation--------------------------------- 17

1. The Thirteenth Amendment--------------------------- 17

2. Implementing legislation: The Freedmen’s Bu

reau bills, and the Civil Rights Act of 1866.. 20

D. The Fourteenth Amendment in Congress-------------------- 32

1. The Stevens “ apportionment” amendment____ 33

2. The Bingham “ equal rights” amendment--------- 36

3. H. J. Res. 127: the Fourteenth Amendment--. 41

a. The House debate------------ 42

b. The Senate debate------------------------------- 48

E. The ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment by the

States____________________________________________ 57

F. Contemporaneous actions, federal and state, bearing on

school segregation_________________________________ 66

1. Federal legislation in the 39th Congress----------- 67

a. The Freedmen's Bureau Extension Act. 67

b. School legislation for the District of Co

lumbia_____________________________ 69

2. Legislation in Congress after 1866------------------- 72

a. Readmission of the Southern States____ 72

b. Legislative attempts to abolish school

segregation in the District of Colum

bia_________________________________ 76

c. Civil Rights Act of 1875_______________ 78

3. State legislation and decisions_________________ 86

a. Negro education in the North_________ 90

b. Negro education in the South__________ 96

c. State judicial decisions on Negro edu

cation _______________ 100

d. Significance of the contemporaneous

state laws providing for school segre

gation______________________________ 104

G. Summary and conclusions___________________________ 112

280315— 53-------1 (I)

n

in

Page

It. is within the judicial power, in construing the Fourteenth

Amendment, to decide that racial segregation in public schools

is unconstitutional. _ ^___________ ____________________ 132

IV

If the Court holds that racial segregation in public schools is

unconstitutional, it has power to direct such relief as in its

judgment will best serve the interests of justice in the cir

cumstances_____________________________:__________________ 152

V

If the Court holds that racial segregation in public schools is

unconstitutional, it should remand these cases to the lower

courts with directions to carry out this Court’s decision as

speedily as the particular circumstances permit____________ 168

A. Obstacles to integration___ ________________________ 170

B. The decrees_______________________________________ 182

Conclusion__________________________________________________ 187

CITATIONS

Cases:

Adamson v. California, 332 U. S. 46_____________________ 128

Addison v. Holly Hill Co., 322 U. S. 607_________________ 155

Alexander v. Hillman, 296 U. S. 222_____________________ 155

Armour & Co. v. Wantock, 323 U. S. 126________________ 167

Atkin v. Kansas, 191 U. S. 207__________________________ 147

Atlantic Coast Line v. Florida, 295 IT. S. 301_____________ 155

Attorney General v. Birmingham, 4 Kay & J. 528 (1858)__ 158

Attorney-General v. Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum, 4 Ch.

App. 146____ 158

Attorney General v. Corporation of Halifax, 39 L. J. Ch.

N. S. 129___________________________ 158

Attorney-General v. Finchley Local Board, 3 Times L. It. 356_ 158

Attorney-General v. Proprietors of the Bradford Canal, L. It.

2 Eq. 71___ 158

Bailey v. City of New York, 38 Misc. (N. Y.) 641________ 159

Baltimore v. Brack, 175 Md. 615________________________ 158

Beasley v. Texas and Pacific Ry. Co., 191 U. S. 492_______ 156

Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 IT, S. 45______________- ___ 144

Board of Education v. Tinnon, 26 Kans. 1________________ 102

Bonner, In re, 151 U. S. 242____________________________ 156

Boston Rolling Mills v. Cambridge, 117 Mass. 396________ 158

Breed v. City of Lynn, 126 Mass. 367_________ ___________ 158

Breedlove v. Suttles, 302 IT. S. 277_______________________ 126

Brehm v. Richards, 152 Md. 126_________________________ 158

Browder v. United States, 312 U. S. 335__________________ 131

I l l

Brown v. Board of Trustees, 187 F. 2d 20------------------------- 163

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60----------------------------------- 141

Butterfield v. Zydok, 342 U. S. 524______________________ 157

Caretti v. Broring Building Co., 150 Md. 198-------------------- 158

Central Kentucky Co. v. Railroad. Commission, 290 U. S.

264____________________________________________________ 155

Chapman v. City of Rochester, 110 N. Y. 273-------------------- 159

Chase v. Stephenson, 71 111. 383-------------------------------------------- 101

City of Manchester v. Farnworth (1930), A. C. 171------------ 158

City of San Diego v. Van Winkle, 69 Cal. App. 2d 237----- 158

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ----------------------------------------- 7, 80

Clark v. The Board of Directors, etc., 24 Iowa 267---------- 101, 103

Cohens v. Virginia, 6 Wheat. 264------------------------------------ 166

Colegrove v. Green, 328 U. S. 549----------------------------------------- 150

Commonwealth v. Davis, 10 Weekly Notes 156 (1881)---------- 104

Commonwealth v. Helm, 9 Ky. L. Rep. 532---------------------- 112

Commonwealth ex rel. Brown v. Williamson, 10 Phila. 490-_ 102

Cory v. Carter, 48 Ind. 327___________________________ 107, 146

Camming v. Board of Education, 175 U. S. 528------------- 107, 144

Dallas v. Fosdick, 40 How. Pr. Rep. 249 (N. Y. Sup. Ct.

1869)_______________________________________________ 89, 101

Davidson v. New Orleans, 96 U. S. 97------------------------------ 131

Doremus v. Mayor and Aldermen of Paterson, 79 N. J. Eq.

63___________________________________________ - ______ 159

Dove v. The Independent School District, 41 Iowa 689-------- 101

Eccles v. Peoples Bank, 333 U. S. 426____________________ 154

Euclid v. Amber Realty Co., 272 U. S. 365------------------------ 142

Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U. S. 1----------------------- 126

Fay v. New York, 332 U. S. 261_________________________ 136

French v. Chapin-Sacks Mfg. Co., 118 Va. 117------------------ 159

Georgia v. Stanton, 6 "Wall. 50__________________________ 150

Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co., 206 IT. S. 230, 237 U. S.

474, 240 U. S. 650_______________________- _________ 157, 164

Giles v. Harris, 189 U, S, 475___________________________ 150

Gompers v. United States, 233 IT. S. 604--------------------------- 130

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78------------------------------------- 145

Great Central Ry. v. Doncaster Rural Council, 87 L. J. R.

N. S. 80_____________________________________________ 158

Gregory v. Crain, 291 Ky. 194___________________________ 158

Gandy v. Village of Merrill, 250 Mich. 416--------------------- 159

Harding v. Stamford Water Co., 41 Conn. 87-------------------- 158

Harper v. Railway Co., 76 W. Va. 788----------------------------- 164

Harrisonville v. Dickey Clay Co., 289 IT. S. 334----------------- 158

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U. S. 321___________________- 155, 156

Heim v. McCall, 239 U. S. 175__________________________ 147

Helvering v. Davis, 301 U. S. 619________________________ 131

Holden v. Hardy, 169 U. S. 366_________________________ 131

Home Bldg. & Loan Ass’n. v. Blaisd'ell, 290-UTS.'398—'----- 128

Gases—Continued Pase

IV

Cases—Continued Page

I-Iurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24_________ _______ __________ - 111

Hurtado v. California, 110 U. S. 516_____________________ 131

Inland Steel Co. v. United States, 306 U. S. 153___________ 156

Joy v. St. Louis, 138 U. S,JL____________________________ 164

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214________________ 140

Legal Tender Cases, 12 Wall. 457________________________ 128

Lohman v. The St. Paul R. R. Co., 18 Minn. 174------- , ----- 159

Luther v. Borden, 7 Bow. 1______________________________ 150

Mahler v. Eby, 264 U. S. 32________________- ____________ 157

Maxwell v. Dow, 176 U. S. 581____________- __________ 126, 140

McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry. Co., 235 U. S.

151________________________________ - ______________ 164, 167

McCulloch y . Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316___________ ----------- 128

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637---------- 136,

148, 149, 151, 164

McPherson v. Blacker, 146 U. 8. 1----------------------------------- 126

Medley, Petitioner, 134 U. S. 160------------------------------------- 157

Mercoid Corp. v. Mid-Continent Co., 320 U. S. 661----------- 156

Metropolitan Rd. v. District of Columbia, 132 U. S. 1--------- 70

Minnesota v. National Tea Co., 309 U. S. 551------------------- 154

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337-------------- 65,

107, 136, 143, 146, 164

Moody v. Village of Saratoga Springs, 17 App. Div. (N. Y.)

207, affirmed, 163 N. Y. 581__________________________ 159

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370_________________________ 140

Nebraska v. Wyoming, 325 U. S. 589________________ ____ 164

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536--------------------------------- 112, 141

Northern Securities Co. v. United States, 193 U. S. 197------ 159

North Staffordshire Ry. Co. v. Board of Health, 39 L. J. Ch.

N. S. 131 (1870)_____________________________________ 158

Pacific States Telephone and Telegraph Co. v. Oregon, 223

U. S. 118____________________________________________ 150

People v. Easton, 13 Abbott’s Pr. R. (N. S.) 159 (Sup. Ct.,

1872)________________________________________________ 103

People ex rel. John Congress v. The Board of Education, etc.,

101 111. 308___________________________________________ 102

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537_____________________ 140, 144

Porter v. Warner Co., 328 U. S. 395--------------------------------- 156

The Protector, 12 Wall. 700______________________________ 150

Radio Station WOW, Inc. v. Johnson, 326 U. S. 120----- 154, 156

Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman Co., 312 U. S.

496__________________________________________________ 156

Railway Express v. New York, 336 U. S. 106-------------------- 138

Roberts v. City of Boston, 5 Cush. (Mass.) 198--------- 12, 103, 145

Rochin v. California, 342 U. S. 165_______________________ 131

Sammons v. City of Gloversville, 34 Mise. (N. Y.) 459------, 159

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91------------------------------- 136

V

Cases—Continued Page

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1______________ 111, 141, 164, 181

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631. 107, 136, 148, 164, 165

Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall. 36.---------------------- 118, 119, 139

Smith v. The Directors, etc., 40 Iowa 518-------------------------- 101

South Carolina v. United States, 199 U. S. 437------------------ 131

Southern R. Co. v. Franklin &c. M. C. R. Co., 96 Va. 693— 164

Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U. S. 1__________ 160, 162

State v. White, 90 N. J. Eq. 621--------------------------------------- 159

State Board of Equalization v. Young’s Market Co., 299

U. S. 59______________________________________________ 126

State ex tel. Games v. McCann, 21 Ohio St. 198- 92, 95,103, 107,146

State ex rel. Hatfield v. Carrington, 194 la. 785------------------ 112

State ex rel. Stoutmeyer v. Duffy, 7 Nev. 342----------------- 102, 146

Stovern v. Town of Colmar, 204 la. 983---------------------------- 158

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 IT. S. 303— 110, 111, 118,122,139

Suburban Land Co., Inc. v. Billerica, 314 Mass. 184--------- 158

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629____ 107, 136, 148, 149, 151, 164

Tod v. Waldman, 266 U. S. 113-------------------------------------- 157

Town of Purcettville v. Potts, 179 Va. 514________________ 159

Union Pacific Ry. Co. v. Chicago, <fee. Ry. Co., 163 U. S. 564. 155

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75--------------- 147

United States v. Aluminum Co., 322 U. S. 716, 148 F. 2d

416, 171 F. 2d 285, 91 F. Supp. 333___________________ 160

United States v. American Tobacco Co., 221 U. S. 106, 191

Fed. 371___________________- ______________________ 160, 185

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299----------------------------- 130

United States v. International Harvester Co., 214 Fed. 987,

274 U. S. 693__________________ - ______________ 160, 162, 163

United States v. Morgan, 307 U. S. 183-----------: ------------ 155, 157

United States v. National Lead Co., 332 U. S. 319--------- 154, 160

United States v. Paramount Pictures, 70 F. Supp. 53, 334

U. S. 131, 85 F. Supp. 881, 339 U. S. 974___________ 160, 163

United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U. S. 649---------------- 128

Van Camp v. Board of Education of Logan, 9 Ohio 406----- 12

Virginia, Ex parte, 100 U. S, 339------------ 109, 124, 137, 138, 140

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313--------------------------- 124, 137, 139

Virginian Railway Co. v. System Federation, 300 U. S. 515- _ 156

Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36________________________—-- 103, 107

Weems v. United States, 217 U. S. 349---------------------------- 129

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319

U. S. 624____________ _______________________________ 151

Wiertian v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183-------------------------------- 147

Williams v. United States, 341 U. S. 97--------------------------- 136

Winchell v. City of Waukesha, 110 Wis. 101-------------------- 159

Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25_____________________— 131, 142

Yakus v. United States, 321 U. S 414----------------------------- 156

VI

Executive Orders and Regulations: Page

Emancipation Proclamation, 1863_______________________ 4

Executive Order 9346, May 27, 1943, 8 F. R. 7183----------- 179

Executive Order 9980 of July 26, 1948, 13 F. R. 4311____ 179

Executive Order 10479, August 15, 1953, 18 F. R. 4899____ 179

Proclamation No. 16 of Sept. 22, 1862, 12 Stat. 1267______ 18

5 C. F. R. 410 1-7 (1952 Supp.)_____________ ____________ 179

Federal Statutes:

The Captured and Abandoned Property Act of 1863, 12

Stat. 820_____________________________________________ 18

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27__________________ 5, 20, 59

Civil Rights Act of March 1, 1875, 18 Stat. 335___ 7, 66, 80, 85

Confiscation Act of 1861, 12 Stat. 319----------------------------- 18

Enforcement Act of 1870, 16 Stat. 140___________________ 6

Freedmen’s Bureau Extension Act, July 16, 1866, 14

Stat. 173_____________________________________________ 21, 67

Reconstruction Act of March 2, 1867, 14 Stat. 428------ 5, 72, 98

12 Stat. 376__________________________________________ 4

Act of May 20, 1862, 12 Stat. 394_______________________ 69

Act of May 21, 1862, 12 Stat. 407_______________________ 69

12 Stat. 432____________________________________________ 4

Act of June 25, 1864, 13 Stat. 187________________________ 69

13 Stat. 567, 774_______________________________________ 19

Act of July 23, 1866, 14 Stat. 216_________________________ 69, 71

Act of July 28, 1866, 14 Stat. 343________________________ 69, 71

14 Stat. 428, sec. 5__________________________________ . . . . 98

16 Stat. 59, Dec. 22, 1869_________________________ 76

16 Stat. 62_____________________________________________ 74, 88

16 Stat. 67_____________________________________________ 74, 88

16 Stat. 80____________________________________________ 74, 88

16 Stat. 363_________________________________________ 75

18 Stat. 336____________________________________________ 136

8 U. S. C.:

41 ____________________ 124

42 _______________________________________________ 124

41-48______________________________________________ 136

44_________________________________________________ 136

18 U. S. C.:

241-243____________________________________________, 136

28 U. S. C.:

1343_______________________________________________ 136

2243_______________________________________________ 157

State Constitutions and Statutes:

Alabama Constitution of 1867, Art. I, sec. 2----------------- __ 98

Alabama Laws 1868, p. 148 (Act of the Board of Educa

tion) _________________________________________________ 100

Arkansas Laws 1866-67, No. 35, Sec. 5, p. 100----------------------- 99

VII

Arkansas Laws 1868, No. 52, Sec. 107:

P. 163_____________________________________________ 100

P. 148_________________________ - __________________ 100

California Laws 1866, c. 342, sec. 57-------------------------------- 89

Connecticut Public Laws 1868, p. 206----------------------------- 93

Delaware Laws 1875, ch. 48-----------------, ------------------------- 89, 94

District of Columbia Code (1951 ed.):

§§ 31-670, 31-671__________________________________ 171

§§ 31-1110, 31-1112________________________________ 170

Florida Constitution of 1868, Art. IX, sec. 1-------------------- - 100

Florida Laws 1865, No. 12, ch. 1475-------------------------------- 100

Georgia Laws 1870, No. 53, Sec. 32-------- ------------------------ , 100

Illinois Public Laws 1872, p. 700------------------------------------- 93

Illinois Public Laws 1874, p. 120------------------------------------- 93

Indiana Laws 1869 (Special session), p. 41---------------------- 89, 93

Indiana Laws 1877, p. 124----------------- 93

Kansas Laws 1867, ch. 125______________________________ 93

Kentucky Laws (Gen. St. 1873—Bullock & Johnson),

ch. 62,'Art. I ll, § 2_________________________________ 110

Kentucky Laws 1873-1874, eh. 521--------------------------------- 94

Louisiana Constitution of 1868:

Art, 2_____________________________________________ 98

Art. 13____________________________________________ 99

Arts. 135, 136______________________________________ 98

Maryland, Annotated Code (Flack ed., 1951), Art, 77,

§H 2 (4), 208________________________________________ 171

Maryland Laws 1868, c. 407, c. IX -------------- ------------------89, 94

Maryland Laws 1872, c. 377, c. X V III--------------------------- 94

Massachusetts Acts and Resolves 1867, p. 820----------------- 61

Michigan Laws 1867, Act. No. 34----------------------------------- 93

Mississippi Code (1942 ed.), Art. 15, §§ 6808-6811------------- 171

Mississippi Constitution of 1868, Art. I, Sec. 21--------------- 99

Missouri Laws (Wagner’s Mo. Stat. 1870 (2d ed.) ch. 80,

§ 2 )_____________________________________ ____________ 111

North Carolina Laws, 1868-1869, ch. 184, Sec. 50, p. 471__ 100

51 Ohio Laws, p. 429, sec. 31 (1853), as amended, 61 Ohio

Laws 31, sec. 4 (1864)________________________________ 88

Oregon (Gen. Laws of Oregon, 1843-1872, Civil Code,

§ 918)_________________________________________________ 111

South Carolina Code (1952), §§ 21-251, 21-290_________ 170

South Carolina Constitution of 1868, Art. X, secs. 10, 39__ 98

Vernon’s Texas Civil Statutes, title 49, ch. 8--------------- - 171

Virginia Laws 1869-1870, ch. 259, Sec. 47-------------------------- 100

West Virginia Acts of 1872-1873, p. 102, reenacting chapter

116 of the 1870 Code____________________ __________

State Constitutions and Statutes—Continued Pags

110

VIII

Congressional Reports and Documents: Pago

H. Ex. Doc. No. 315 (1871), 41st Cong., 2d Sess_________ 8,

14, 16, 17, 90

H. J. Res. 127, 39th Cong., 1st Sess__________________21, 41, 42

H. R. 380, 42d Cong., 2d Sess___________________________ 79

H. R. 613, 39th Cong., 1st Sess_________________________ 67

H. R. 783, 41st Cong., 2d Sess__________________________ 75

H. R. 796, 43d Cong., 2d Sess___________________________80, 83

H. R. 1050, 42d Cong., 2d Sess__________________________ 79

H. R. 1335, 41st Cong., 2d Sess_________________________ 76

S. 1, 43d Cong., 1st Sess________ ________________________ 79, 81

S. 9, 39th Cong., 1st Sess----------------------------------------------- 22

S. 60, 39th Cong., 1st Sess__________________________ 21, 23, 25

S. 61, 39th Cong., 1st Sess______________________________ 23, 25

S. 365, 42d Cong., 2d Sess_______________________________ 78

S. 916, 41st Cong., 2d Sess---------------------------------------------- 78

S. 1244, 41st Cong., 3d Sess_____________________________ 76

S. Doc. No. 14, 83d Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 4 -8 ------------------- 173

S. Doc. 711, 63d Cong., 3d Sess. (Journal of the Joint

Committee on Reconstruction)______ 32, 33, 36, 37, 38, 41, 42

State Miscellaneous:

Alabama Senate Journal 1866, p. 32--------------,----------------- 63

Alabama Senate Journal 1868, p. 14-------------------- ---------- 97

Alabama Convention Journal, pp. 153, 237-238--------------- 98

Arkansas Convention Debates and Proceedings, p. 645

et seq________________________________________________ 98, 100

Arkansas House Journal 1868----------------------------------------- 64, 97

Florida Senate Journal 1866, p. 8__________________ _____ 64

Georgia Convention Journal, p. 151-------------------------------- 98

Georgia House Journal 1870, p. 416-------------------------------- 97

Georgia Senate Journal 1866, pp. 65-71--------------------------- 63

Illinois Doc. 1869, vol. 2, p. 557-------------------------------------- 91

Illinois Doc. 1871, pp. 355 et seq. (Report of Superintendent

of Public Instruction 1869-1870)--------------------------------- 93, 95

Illinois Doc. 1871, pp. 355-356 (Report of Superintendent

of Public Instruction 1869-1870)--------------------------------- 95

Illinois Doc. 1873, vol. 2 (Report of Superintendent of

Public Instruction 1871-1872, pp. 115 et seq.)--------------- 95

Illinois Senate Journal 1867 (Governor Oglesby), p. 29----- 61

Indiana Doc. 1865-1866, p. 339 (Report of Superintendent

of Public Instruction 1865-1866)------------- ------------------- 94

Indiana Doc. 1867-1868 (Report of Superintendent of

Public Instruction 1867-1868)------------------------------------- 93, 94

Indiana Doe. 44th Reg. Sess. (1867), Part I, p. 338--------- 91

Indiana Senate Journal 1867, pp. 14, 40 et seq------------------ 60

Louisiana Convention Journal, pp. 60-61, 94, 200-202,

268-270, 277___________________________________ 98

IX

Louisiana House Debates 1866, pp. 209-10, 217-20, 246-7.. 100

Louisiana Legislative Documents 1870, Message of the

Governor, p. 7______________ ______ __________________ 97

Maryland Docs. 1870, House Doc. A., pp. 14-15_________ 92

Mississippi Convention Journal, pp. 316, 318, 479-480___ 98

New Hampshire House Journal 1866, p. 176, et seq_______ 62

New York Assembly Journal 1867, vol. 1, p. 13__________ 61

North Carolina Public Docs. 1867-1868, Doc. No. 2, Sess.

1868, pp. 5-6_________________________________________ 97

Ohio Doc. 1869, pp. 885, et seq. (18th Annual Report)____ 96

Ohio Constitutional Convention, 1873-1874, Debates, vol,

2, part 2:

pp. 2238, et seq____________________________________ 96

pp. 2240-41____________________________ __________ 96

Pennsylvania Leg. Rec., 1867 (Jenks Penn. Debates),

Appendix:

p. X L I----------------------------------------------------------------------- 61

p. IX _______________________________________ 62

p. C C C X L II-._________________________ 96

Pennsylvania Leg. Rec., 1867, Appendix, pp. C C C XLII.. 96

Pennsylvania Leg. Rec., 1867 (Taylor in the Pennsylvania

Debates), Appendix, p. X X II___________________________ 61

South Carolina Convention Proceedings, pp. 71, 88, 100,

685-709, 889, 894, 899-901_____________ . . . _______ . . . 98

Tennessee Senate Journal (Gov. Brownlow called Session),

1866, p. 4 . . ........................ ............... .......... ......... ............. 01

Texas Convention Journal, I, pp. 896, 898, 912__________ 98

Virginia Convention Journal, pp. 67, 299, 308, 333, 335,

336, 339, 340___________________________ 98

Wisconsin Senate Journal, 1867, p. 96___________________ 62

General Miscellaneous:

American Freedman 1866, p. 18_________ _____ _________ 68

Barnard, Special Report of the Commissioner of Education,

II. Ex. Doc. No. 315, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. (1871)___ 8,

14, 16, 17, 90

Beach, High on Injunctions (4th ed.), sec. 746____________ 159

Beach, Injunctions (1895), sec. 2________________________ 159

Bond, The Education of the Negro in the American Social

Order, New York, 1934________________________________ 16

Brandeis, The Living Law, 10 111. L. Rev. 461 (1916)........... 131

Brevier, Legislative Reports 1865______ __________ ________ 91, 95

Brevier, Legislative Reports 1867, p. 80.__________________ 64

Brevier, Legislative Reports (1869), pp. 193 et seq., 340

et seq., 490 et seq........................................ ......... ............... 95

11 Brevier, Legislative Reports (1869 Extra Session), pp. 114

et seq., 387 et seq________ ______ . . . . .

State Miscellaneous—Continued j?w

95

X

Buck, The Road to Reunion, 1865-1900 (1937)------------------- 7

Bustard, The New Jersey Story: The Development of' Ra

cially Integrated Public Schools, 21 Journ. of Negro Edu

cation, 275 (1952)_________________ 178

Cardozo, The Growth of the Law (1924)____________________ 131

Cardozo, The Nature of the Judicial Process (1921)----------- 131

Cardozo, The Paradoxes of Legal Science (1928), p. 99------- 131

Chicago Com. on Human Relations, Report of the, The

People of Chicago, 1947-1951---------------------------------- — 181

Cubberley, Public Education in the United States (1919),

p. 119, et seq_______________________________________ 8, 9, 12

Curtis, The Republican Party (1904), Vol. I, Ch. V I--------- 13

Douglas, Stare Decisis (1949)------------------------ :----------------- 132

Dunning, Reconstruction Political and Economic 1865—1877

(1907), p. 41_________ 7

Dumond, Antislavery Origins of the Civil War in the United

States (1939) ___________________________________ 10, 11, 13

Flack, The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment (1909),

Chs. I ll, IV__________________________ _____ ______ 59, 60, 63

Frankfurter, Law and Politics (1939)-------------------------------- 132

Frankfurter, Mr. Justice Holmes’ Constitutional Opinion

(1923), 36 Harv. L. Rev. 909_________________________ 131

Frankfurter, Mr. Justice Holm.es and the Supreme Court

(1938)________________________________________________ 132

Graham, The Early Antislavery Backgrounds of the Four

teenth Amendment (1950), Wis. L. R. 479---------------------- 10

Graham, Procedure to Substance— Extra-Judicial Rise of

Due Process, 1830-1860, 40 Cal. L. R. 483 (1953)______ 10

Holmes, The Common Law (1881)----- ------------- ----------- — 131

Holmes, The Path of the Law, 10 Harv. L. Rev. 457 (1897)— 131

Housing and Home Finance Agency, Public Housing

Administration, 1953, Open Occupancy in Public Housing_ 181

Hughes, Addresses (1916), pp. 354-355---------------------------- 131

Hughes, The Supreme Court of the United States (1928)------- 131

Hurd, Law of Freedom and Bondage in the United States

(1862), Vol. 2, pp. 1-218______________________________ 14

Integration of the Negro into American Society (1951)------- 182

Jackson, Full Faith and Credit (1945)------------------------------ 132

Jackson, The Struggle for Judicial Supremacy (1941)------ 132

James, The Framing of the Fourteenth Amendment (1939)- 50

Jenkins; Pro-Slavery Thought in the Old South (1935)--------- 10, 11

Knight, Public Education in the South (1922)------------------- 8, 9

Mangum, The Legal Status of the Negro (1940)------------------ 112

McPherson, Political History of the United States, 1860-1865

(1865)_____________________ 119

McPherson’s, Scrap Book, 14th Amendment, p. 84-------— 65

General Miscellaneous—Continued Page

XI

New York Times, Aug. 24, 1953, p. 21____________________ 178

Nye, Fettered Freedom (1949)_________________________10, 11, 15

Pomeroy, Equity Jurisprudence (5th ed.), Secs. I l l , 170,

176a-------------------------------------------------------------------------- 155

Pomeroy’s Eq. Rem. (1905):

Secs. 531, 535______________________________________ 159

Sec. 761______________________________ 164

Randall, The Civil War and Reconstruction (1937), p. 724__ 15

Reed, Stare Decisis and Constitutional Law (1938), No. 35

Penna. Bar Asa’n Quarterly, 131_______________________ 131

Selected Studies of Negro Employment in the South: 8

Southern Plants of International Harvester Company

(National Planning Association, 1953)_ 181

1 Seton, Judgments and Orders (7th ed.), p. 612__________ 158

Statistics of State School Systems 1949-1950 (Chapter 2 of

Biennial Survey of Education in the United States

(1948-1950)___________________________________ . _____ 172

Stephenson, Race Distinctions in American Law (1910),

Ch. IV______ ______________________ _________ _____ 14, 15

Stone, Fifty Years’ Work of the Supreme Court (1928), 14

A. B. A. Journ. 428___________________________________ 131

Stone, Law and Its Administration (1924)_______________ 131

Story, Equity Jurisprudence (14th Ed.), Secs. 28, 578__ _ 155

ten Broek, The Anti-Slavery Origins of the Fourteenth

Amendment (1951)_____________________________ 10, 11, 12, 13

Toledo Board of Community Relations, Report of the,

1951_____ 181

U. S. News & World Report, October 16, 1953, pp. 46, 99_- 180

“ Transitional Housing Area,” Report of the Director of

the Mayor’s Interracial Committee in Detroit (1952)__ 181

United Press Survey, New York Times, Jan. 22, 1951___ 181

Wickersham, J. P., A History of Education in Pennsyl

vania (1886), p. 506__________________________________ 109

Wilson, Rise and Fall of Slave Power in America (1874):

Vol. I, pp. 496-498__________ 12

Vol. II, p. 406_____________________________________ 13, 14

Woodward, Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of

1877 and the End of Reconstruction (1951)_____________ 7

General Miscellaneous—Continued pag0

Jjitihe$ttpremj<!|mtrt«f J M i t M jltstea

O ctober T e r m , 1953

No. I 1

O liver B r o w n , et a l ., app ellan ts

v.

B oard of E d u ca tio n of T o p e k a , S h a w n e e

C o u n t y , K a n sa s , e t a l .

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEE BOB THE UNITED STATES ON

REARGUMENT

On June 8, 1953, the Court ordered these eases

restored to the docket for reargument, and re

quested counsel in their briefs and on oral argu

ment to discuss certain questions. The order also

invited the Attorney General of the United States

to take part in the oral argument and to file an

additional brief if he so desires.2

1 Together with No. 2, Briggs, et al. v. Elliott, et al.; No. 4,

Dorothy E. Davis, et al. v. County School Board, of Prince

Edward County, Virginia, et al.; No. 8, SSpottswood Thomas

Bolling, et al. v. C. Melvin Sharpe, et al.; and No. 10, Francis

B. Gebhart, et al. v. Ethel Louise Belton, et ad.

2 The full text of the Court’s order is as follows (345 U. S.

972-973):

“Each of these cases is ordered restored to the docket and is

assigned for reargument on Monday, October 12, next. In

(l)

2

Since tit e United States is not a party to any of

these cases and is participating herein solely as an

amicus curiae, it submits this brief as an objective

non-adversary discussion of the questions stated in

the Court’s order of reargument. No attempt has

been made to reexamine other questions briefed

and argued at the last term.

their briefs and on oral argument counsel are requested to

discuss particularly the following questions insofar as they

are relevant to the respective cases:

“ 1. What evidence is there that the Congress which sub

mitted and the State legislatures and conventions which

ratified the Fourteenth Amendment contemplated or did not

contemplate, understood or did not understand, that it would

abolish segregation in public schools ?

“2. I f neither the Congress in submitting nor the States in

ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment understood that com

pliance with it would require the immediate abolition o f seg

regation in public schools, was it nevertheless the understand

ing of the framers o f the Amendment

“ (a) that future Congresses might, in the exercise o f their

power under section 5 of the Amendment, abolish such segre

gation, or

“ (b) that it would be within the judicial power, in light

o f future conditions, to construe the Amendment as abolish

ing such segregation o f its own force?

“ 3. On the assumption that the answers to questions 2 (a )

and (b) do not dispose o f the issue, is it within the judicial

power, in construing the Amendment, to abolish segregation

in public schools ?

“4. Assuming it is decided that segregation in public

schools violates the Fourteenth Amendment

“ (a) would a decree necessarily follow providing that,

within the limits set by normal geographic school districting,

Negro children should forthwith be admitted to schools of

their choice, or

“ (b) may this Court, in the exercise of its equity powers,

permit an effective gradual adjustment to be brought about

3

I and II

THE CONTEMPORARY UNDERSTANDING OP THE FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENT W ITH RESPECT TO ITS EFFECT

ON RACIAL SEGREGATION IN PUBLIC SCHOOLS

The first two questions asked by the Court are as

follows:

1. What evidence is there that the Con

gress which submitted and the State legisla

tures and conventions which ratified the

Fourteenth Amendment contemplated or

did not contemplate, understood or did not

understand, that it would abolish segrega

tion in public schools ?

2. I f neither the Congress in submitting

nor the States in ratifying the Fourteenth

Amendment understood that compliance

from existing segregated systems to a system not based on

color distinctions?

“ 5. On the assumption on which questions 4 (a) and (b)

are based, and assuming further that this Court will exercise

its equity powers to the end described in question 4 (b ),

“ (a) should this Court formulate detailed decrees in these

cases;

“ (b) i f so, what specific issues should the decrees reach;

“ (c) should this Court appoint a special master to hear

evidence with a view to recommending specific terms for

such decrees;

“ (d) should this Court remand to the courts o f first in

stance with directions to frame decrees in these cases, and

if so what general directions should the decrees o f this Court

include and what procedures should the courts o f first in

stance follow in arriving at the specific terms o f more de

tailed decrees?

“ The Attorney General of the United States is invited to

take part in the oral argument and to file an additional

brief if he so desires.”

4

with it would require the immediate aboli

tion of segregation in public schools, was it

nevertheless the understanding of the fram

ers of the Amendment

(a) that future Congresses might, in the

exercise of their power under section 5 of

the Amendment, abolish such segregation, or

(b) that it would be within the judicial

power, in light of future conditions, to con

strue the Amendment as abolishing such

segregation of its own force ?

Since the historical materials examined are rele

vant to both questions, they are here treated

together.3

A. INTRODUCTORY

1. The reconstruction 'period

Abolition of slavery by national action began

while the Civil War was in progress, with Con

gressional abolition in the District of Columbia

(12 Stat. 376) and the territories (12 Stat. 432)

in 1862, and President Lincoln’s Emancipation

Proclamation in 1863. The Thirteenth Amend

ment, abolishing slavery everywhere within the

United States, was proposed by Congress on Feb

ruary 1, 1865, and declared adopted on December

18, 1865.

After the termination of hostilities, new govern

ments were established in the Southern states

under Presidential authority. Negroes were not

3 The Appendix, which is contained in a separate volume,

consists of detailed factual summaries o f the materials on

the vai’ious aspects o f the historical questions which are

dealt with in this brief.

5

allowed, however, to participate in the elections

held in these states, and in December 1865 Con

gress refused to seat members chosen in such elec

tions. At the same session Congress created a

Joint Committee on Reconstruction, to which all

matters concerning the South were referred and

which originated the various measures which

formed the program of Congressional reconstruc

tion.

During 1866 Congress, over the opposition of

President Johnson, extended the functions of the

Freedmen’s Bureau, which had been created in

1865 to promote the welfare of the freed Negroes

and to protect their civil rights. In April of the

same year it enacted over a veto the Civil Rights

Act (14 Stat. 27), which was designed to enforce

by Federal authority the civil rights of Negroes,

including their right to “ full and equal benefit of

all laws and proceedings for the security of per

son and property * *

Two months later, on June 16, 1866, Congress

proposed the Fourteenth Amendment. By March

1867 most of the Northern states had ratified the

Amendment. Three border states had rejected it,

however, and of the Southern states only Ten

nessee had ratified it, making a total of less than

the required three-fourths. The elections of 1866

had returned to Congress a clear majority in

favor of the program of Congressional recon

struction. Accordingly, in March 1867 Congress

enacted the Reconstruction Act (14 Stat. 428)

280315—53----- 2

6

under which the Southern states (except for Ten

nessee) were divided into five military districts

and the existing state governments were declared

to be provisional only. The Act provided that

military supervision would be withdrawn, and a

state’s representatives readmitted to Congress,

after it had (a) framed a new constitution “ in

conformity with the Constitution of the United

States in all respects,” (b) adopted universal

male suffrage, and (c) ratified the Fourteenth

Amendment. By June 1868 seven states had met

all of these conditions and were restored to repre

sentation. On July 21, 1868, the Amendment,

having been ratified by the legislatures of thirty

of the thirty-seven states to which it was sub

mitted, was declared adopted. Subsequently, the

other three Southern states ratified the Amend

ment, and their representatives were readmitted

to Congress.

The impeachment of President Johnson in

1868, arising out of his differences with Congress

on reconstruction policy, was unsuccessful, but the

election of Grant that year brought into office a

President who was in agreement with the Con

gressional program. To assure the Negroes the

right to vote, protected by the national govern

ment, a third constitutional amendment, the F if

teenth, was proposed by Congress in February

1869 and came into effect in March 1870. In the

latter year the Enforcement Act (16 Stat. 140)

7

reenacted the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and im

posed civil and criminal sanctions for violation of

rights secured by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments.

Congress in 1875 enacted a new Civil Rights

Act (18 Stat. 335)4 declaring that all persons

within the jurisdiction of the United States shall

be entitled to the “ full and equal enjoyment” of

the accommodations of inns, public conveyances,

theatres, and other places of public amusement,

and providing civil and criminal penalties for vio

lations. That Act marked the end of attempts

during the reconstruction period to enforce by

federal legislation equality of treatment for the

emancipated Negroes.

After the determination in 1877 that Hayes

had been elected President, the use of Federal

authority to support the reconstruction govern

ments in the Southern states ceased.5

4 This Act was held unconstitutional in 1883 in the Civil

Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3.

5 An historian has described the settlement o f the Hayes-

Tilden election dispute as follow s: “ Generalized, this famous

bargain meant: Let the reforming Republicans direct the

national government and the southern whites may rule the

Negroes. Such were the terms on which the new adminis

tration took up its task. They precisely and consciously

reversed the principles o f reconstruction as followed under

Grant, and hence they ended an era.” Dunning, Reconstruc

tion, Political and Economic, 1865-1877 (1907), p. 41; see

also Woodward, Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise

of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction (1951); Buck, The

Road to Reunion, 1865-1900 (1937).

8

2. Public education in the United States in 1866

The quarter-century before the Civil War wit

nessed the initial efforts to establish free, tax-

supported public schools throughout the United

States.6 By 1861 the principle of free public

education had become accepted in ahnost all of

the Northern states. Common schools open to all,

and supported by general taxation, existed in

most of the cities and towns, and in a large num

ber of rural areas.7

In the South, however, different conditions pre

vailed. The essentially rural and sparsely settled

character of the region made communication slow

and community cooperation difficult. The institu

tion of slavery and the acceptance of class and

social distinctions were formidable barriers to the

growth of public education. In addition, reli

gious influences tended to encourage the view that

education was a parental obligation and not one

which the state should assume. Consequently,

education in the South prior to the Civil War was

left largely to private groups.8

Outside of some of the larger cities, such public

schools as existed in the South were generally

6 Cubberley, Public Education in the United States (1919),

p. 119 et seq.; Knight, Public Education in the So-uth (1922),

pp. 196-198.

7 Cubberley, supra, p. 211. A survey of the public school

systems in many cities and towns during this period may be

found in Barnard, Special Report of the Commissioner of

Education, H. Ex. Doc. No. 315, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. (1871),

pp. 77-130.

8 Knight, supra, pp. 264-265.

9

maintained for the benefit of only the children of

the poor.9 Even these were disrupted by the war.

Teachers and students were called away to other

tasks, and the state school funds were diverted

to other purposes. At the close of the war the

Southern states were faced with the task of com

pletely rebuilding their educational systems.10

The development of the present-day system of

public education did not really begin in the South

until the post-war period.11

Although public education was far more ad

vanced in the North than in the South, the condi

tions in the former region hardly approximated

those existing today. The schools were often

small one-room affairs where, in rural areas at

least, not much more than the three R ’s was

taught. In many states the school term was only

three months of a year. Compulsory school at

tendance was scarcely known. Ungraded schools

were common in rural areas, and public high

schools were rare. The quality of instruction was

generally low, judged by modern standards.12

B. THE HISTORICAL ORIGINS AND BACKGROUND OF THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

1. The anti-slavery origins of the reconstruction amenchnents

The constitutional changes of the Reconstruc

tion period, and the civil rights legislation which

9 Ibid.

10 Id., pp. 306,313-317.

11 Cubberley, supra, p. 251.

12 Cubberley, supra, ch. V III, Knight, supra, p. 294 et seq.

10

accompanied them, were the culmination of more

than thirty years of controversy engendered by

the anti-slavery movement. The growth of that

movement and the formation of its constitutional

philosophy, particularly in relation to the Four

teenth Amendment, have been the subject o f

several recent historical and legal studies.13 These

studies show that the conception of the principles

incorporated in the Constitution by the Recon

struction Amendments, and the line of their

development and growth, are to be found in the

long and bitter political and ideological conflict

over slavery that preceded the Civil War.

The abolitionists propounded a philosophy of

equality expressed most frequently in terms de

rived from the Declaration of Independence, an

equality which implied a duty of government to

apply laws impartially to protect the “ natural

and fundamental” rights of all persons, white

and black alike.14 * “ Just as the great objection

to slavery was its lack of legal protection for

slaves, as well as the concomitant, invidious,

and discriminatory treatment of free Negroes

13 Nye, Fettered Freedom (1949); ten Broek, The Anti

slavery Origins of the Fourteenth Amendment (1951); Dia

mond, Antislavery Origins of the Civil War in the United

States (1939); Jenkins, Pro-Slavery Thought in the Old

South (1935) ; Graham, The Early Antislavery Backgrounds

of the Fourteenth Amendment, (1950) Wis. L. Rev. 479, 610;

Graham, Procedure to Substance—Extra-Judicial Rise of

Due Process, 1830-1860, 40 Calif. L. Rev. 483 (1953).

14 ten Broek, supra, pp. 7, 96; Nye, supra, p. 177 et seq.;

Diamond, supra, pp. 71-73.

11

and the wholesale public and private in

vasion of the rights of abolitionists, so the first

object of the abolitionists was to gain legal pro

tection for the basic rights of members of all three

classes. ’ ’ 16 To gain that legal protection from the

governments of the states where slavery existed

was a practical impossibility; so the full impetus

of the movement was directed towards securing

national protection.16

Against the philosophy of absolute equality be

fore the law, pro-slavery advocates posed the con

cept of “ classified equality among equals.” 17 To

them, slavery was not a necessary evil but a “ posi

tive good,” for by relegating a class in society

naturally incapable of self-direction to a position

legally subordinate to that of a class which was

naturally superior and dominant, true equality

was possible within each class.18

The agitation of the anti-slavery forces for

absolute equality stimulated numerous efforts to

eradicate from the laws of Northern states dis

tinctions based on color; these were regarded as

badges of servitude irreconcilable with the equality

which was the natural right of all men.19 An

example was the campaign to open the Massa

chusetts common schools to all, without regard to

color. Those schools were tax supported and free,

16 ten Broek, supra, p. 97; see Dumond, supra, p. 43.

16 ten Broek, supra, ch. I l l , IV , passim.

17 Jenkins, supra, ch. I l l passim; Nye, supra, pp. 185-189.

18 Iiid.

19 Nye, supra, pp. 81-84; ten Broek, supra, pp. 42,54, note 17.

12

and governed by local boards.20 Some boards

yielded to local pressure to abolish segregation;

others did not, and efforts were made after 1844 to

obtain remedial legislation.21 In 1849, after failure

of these efforts, an attempt was made to secure

judicial invalidation of school segregation. In

that year, in Roberts v. City of Boston, 5 Cush.

(Mass.) 198, Charles Sumner argued before the

Supreme Judicial Court that segregation in the

Boston common schools was a violation of the

state constitutional guarantee of equality, because

segregation was in itself a denial of equality.22

He lost the case, but in 1855 the Massachusetts

legislature forbade school segregation.

In Van Camp v. Board of Education of Logan,

9 Ohio 406 (1859), it was held that mulatto chil

dren were not entitled to enter the white common

schools. The basic philosophy of the anti-slavery

movement was expressed in the dissenting opinion,

which declared that “ caste-legislation” was incon

sistent with the theory of a free and popular gov

ernment “ that asserted in its bill of rights the

equality of all men” (p. 415). Twelve years later,

Senator Wilson, a leader in the Congressional pro

gram of reconstruction, referred to these struggles

for Negro access to common schools as an integral

20 Cubberly, Public Education in the United States (1919),

p. 163 et seq.

21 Wilson, Rise and Fall of the Slave Power in America

(1872), vol. I, pp. 495-498.

22 ten Broek, supra, p. 54, note 17.

13

part of the “ contest of forty years between liberty

and equality on the one side and slavery and privi

lege on the other” for securing “ perfect and abso

lute equality in rights and privileges” for the

Negro.23

This application of the philosophy of absolute

legal equality to invalidate distinctions based on

race or color in the Northern states was, however,

a side issue. The main objective was complete

abolition of slavery, and to accomplish that pur

pose it was necessary to secure political control of

the national government.24 These efforts produced

a new national political organization—the Repub

lican Party—established in 1854, and formed

specifically to promote anti-slavery objectives.25

Control of the national government by that party

after the election of 1860 was the occasion for

assertion by the South of the right of sovereign

states to secede from the Union to protect their

domestic institutions; 26 and control of the national

government by that party after the Civil War was

the occasion for amendment o f the Constitution to

embody the principle of “ perfect and absolute”

equality before the law for which the anti-slavery

advocates had so long agitated.

23 Congressional Globe, 41st Cong., 3d Sess., p. 1061.

24 ten Broek, supra, ch. VI.

25 Wilson, supra, vol. II , p. 406 et seq.; Curtis, The Repub

lican Party (1904), vol. I, ch. VI.

26 Dumond, supra, pp. 123-126.

14

2. The status of Negroes (legal, economic, wnd educational)

at the close of the Civil War

By 1865 slavery had been ended in fact. In

that year it was constitutionally abolished.

Emancipation did not, however, make the former

slave a free man in all respects. Abolition of

slavery did not wipe out at a stroke the “ badges

of servitude” which had existed for so many

generations. The Negro “ freedmen” were still

commonly regarded as an inferior race. Legally,

economically, and educationally, the free colored

population was still subject to disabilities not

imposed on white citizens, both in the Southern

states and, to a lesser extent, in some of the

Northern states.

Before the Civil War the states had varied

in their treatment of free colored people. Some

slave states had required freed Negroes to emi

grate ; where permitted to remain, they were lim

ited in their rights to contract, hold property, sue,

appear as witnesses, and to vote or serve on

juries. In some Northern states immigration of

free Negroes was prohibited; in many more, the

right of suffrage was denied.27

27 Hurd, Law of Freedom and Bondage in the United

States (1862), vol. 2, pp. 1-218, contains a complete compila

tion and digest o f these laws; and see Barnard, Special Re

port of the Commissioner of Education, H. Ex. Doc. No.

315, 41st Cong., 2d Sess., Appendix, Legal Status o f the

Colored Population etc., pp. 301-400; Wilson, Rise and Fall

of the Slave Power in America (1874), vol. II , p. 181 et

seq.; Stephenson, Race Distinctions in American Law

(1910), ch. IV . Only in the states of Maine, New Hamp

15

At the close of the war, so-called “Black Codes”

designed to restrict the freedom of the newly-

freed colored people were enacted in the Southern

states. These Codes contained provisions dis

criminating against Negroes with regard to

such matters as employment and the right to

engage in business.28 They were regarded by the

majority in Congress as “ an attempt on the part

of Johnson’s reorganized governments to rees

tablish virtual slavery and thus reverse the result

of the war.” 29

Despite emancipation, the Negroes remained on

the lowest economic level. Cut adrift without

money or property, they generally remained de

pendent upon their former owners for employ

ment. The Black Codes only reinforced that

dependence.

In the field of education the opportunities of

the Southern Negro were far inferior to those of

his brother in the North. Long before the war,

most of the Southern states had enacted legisla

tion prohibiting the education of all Negroes, free

or slave, because of the widespread belief that

such education was conducive to rebelliousness.30

shire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island had

Negroes received the full right o f su If rage.

28 Stephenson, supra, ch. IV.

20 Randall, The Civil War and Reconstruction (1937), p.

724.

30Nye, Fettered Freedom (1949), pp. 70-71. See the

speech o f Senator Wilson (Mass.) on April 12,1860, review

ing these laws, Congressional Globe, 36th Cong., 1st Sess.,

p. 1685.

16

The few Negro schools were operated clandes

tinely. It has been estimated that ninety-five

per cent of the colored population of the South

was illiterate at the time of the Civil War.31

After the war ended, the provisional legisla

tures in the Southern states began to show great

interest in the establishment of systems of public

school education; yet, with few exceptions, they

showed no disposition to extend its benefits to

Negroes.32 This reflected the hostility of many

people in the South towards the principle of

Negro education. The establishment of schools

for Negroes was left largely to northern char

itable societies, in cooperation with the Freed-

men’s Bureau. However, the effectiveness of

these schools was impaired by the opposition of

a considerable portion of the local white popu

lation—an opposition wdiich frequently expressed

itself in violence, with Negro schools being

burned and their teachers, white and colored

alike, beaten and expelled from the community.33

In the North the situation was far different.

Nowhere were there prohibitions against Negro

education,34 although in five states Negroes were

31 Bond, The Education of the Negro in the American

Social Order (1934), p. 21.

82 Id,., p. 41.

33 Id., pp. 28-32.

34 The only border state which had had such prohibitions

was Missouri. By 1865, this prohibition was not only abol

ished, but Negroes were admitted to public schools. Bar

nard, supra, pp. 359-360. A ll the following references to

17

excluded from public schools.35 In some Northern

states they were admitted to the same public

schools as white children; in others, they were

either provided with separate schools, or ad

mitted to the white schools, depending principally

upon the number of children involved; 36 in still

others, they were provided only with separate

schools.37 38 In individual communities in many of

the states the practice varied from the state-wide

pattern, either by legislative permission or com

mon practice, without legal sanction.33

C. THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF THE THIRTEENTH

AMENDMENT AND IMPLEMENTING LEGISLATION

1. The Thirteenth Amendment,

The legislative history of the Fourteenth Amend

ment in Congress must begin with a brief account

o f the Thirteenth Amendment. Both amendments

had a conunon origin and purpose, and were con

the educational status of the Negro are taken from Appendix,

Legal Status o f the Colored Population, etc., pp. 301-400,

o f the Barnard report.

35 Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Indiana and Illinois.

86 Pennsylvania and California are examples.

37 See p. 90, footnote 93, infra.

38 For example, the Ohio state statutes provided only for

separate schools; in the greater part o f the state, however,

with the exception o f Cincinnati, colored children were ad

mitted to the same schools as white children. In Illinois,

where there was no provision for Negro public education, the

city of Chicago, after an unsuccessful experiment with sepa

rate schools during 1864-1865, maintained under its own ordi

nances a fully integrated system of public schools. On the

other hand, New York City and some towns in New Jersey

maintained separate schools for colored children. See Bar

nard, supra, pp. 96, 104.

18

sidered in Congress as related components of an

integral plan of reconstruction.

The Thirteenth Amendment originated in the

38th Congress in the form of a joint resolution

introduced by Senator Henderson in January

1864. (Congressional Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess.,

p. 145.) The resolution proposed that the Consti

tution he amended to provide that “ Slavery or

involuntary servitude, except- as a punishment for

crime, shall not exist in the United States. ’ ’ 39 The

proposal was made only after Congressional and

executive action had been taken which effectively

emancipated the slaves in the Southern states.40

In reporting the resolution, Senator Trumbull,

chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee,

noted that fact. He stated that the amendment

would not only end the institution of slavery but

would remove from the Constitution the inconsist

ency of the founding fathers, who, while proclaim

ing the equality of all men, nevertheless denied all

rights to an entire race (Globe, 38th Cong., 1st

Sess., p. 1313). The resolution passed the Sen

89 Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 1313. The Thirteenth

Amendment, as adopted, provides that “Neither slavery nor

involuntary servitude^ except as a punishment for crime

whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist

within the United States, or any place subject to their

jurisdiction.”

40 The Confiscation Act of 1861,12 Stat. 319; the Captured

and Abandoned Property Act o f 1863,12 Stat. 820; Procla

mation (No. 16) of September 22,1862,12 Stat. 1267.

19

ate, but failed of passage in the House (Globe,

38th Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 1490, 2995) ; and it be

came one of the principal issues in the 1864

national election.41

The overwhelming Republican victory that year

led President Lincoln in December 1864 to recom

mend to the lame-duck session of the 38th Con

gress that the House reconsider its vote (Globe,

38th Cong., 2d Sess., Appendix, p. 3). In Janu

ary 1865 the resolution was passed by the House

by slightly more than the required two-thirds vote

(Globe, 38th Cong., 2d Sess., p. 531). It was sub

mitted to the states for ratification in February

1865, and by December of that year a sufficient

number of states had ratified. (13 Stat. 567, 774.)

The Congressional debates on the Thirteenth

Amendment indicate that its purpose was to make

the Negro, so far as law could do so, an indis

tinguishable element of the general population.42

It was the belief of its proponents that by abolish

ing the institution of slavery they were establish

ing the constitutional principle of full equality

before the law. (Globe, 38th Cong., 2d Sess., pp.

154, 177.) To these men, freedom and equality

were coextensive; the one necessarily implied the

other. (Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess,, pp. 1482,

2957; Globe, 38th Cong., 2d Sess., p. 154.) Simi

a McPherson, Political History of the United States,

1860-65 (1865), pp. 406, 419, 422.

42 See, for example, the remarks o f Rep. Orth (Globe,

38th Cong., 2d Sess., p. 143).

20

larly, those who opposed the Amendment did not

doubt that the freedom conferred upon the Negro

slave included more than “ mere exemption from

servitude.” (Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess., p.

2962.) To them, that freedom was a reversal of

the “ natural and divine” order under which the

colored race was inferior and unequal. (Globe,

38th Cong., 2d Sess., p. 150.) This argument

proceeded on the basis of their understanding

that the Amendment would merge the Negro into

the general mass of people on a basis of full legal

equality. Those who favored the Amendment did

not deny that such was its purpose. (Globe, 38th

Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 2957, 2960, 2989; Globe, 38th

Cong., 2d Sess., pp. 154,202,237.)

£. Implementing legislation: The Freedmen's Bureau bills

and the Civil Rights Act of 1866

In the period between the adjournment of the

38th Congress in March 1865 and the convening of

the 39th Congress in December of that year, the

provisional governments in the Southern states,

which had been set up by President Johnson under

his “ restoration” policy, enacted a series of laws

discriminating against Negroes in various ways,

the so-called Black Codes discussed supra, p.

15. The first session of the 39th Congress, over

the veto of President Johnson, enacted two bills

to nullify the discriminations created by the

Black Codes: (1) the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14

Stat. 27, and (2) the law which extended the life of

the Freedmen’s Bureau and enlarged its powers,

21

14 Stat. 173. It also passed another bill dealing

with the Freedmen’s Bureau which failed of en

actment after it had been vetoed by President John-

son. (S. 60, 39th Cong., 1st Sess.; Globe, p. 94S)43 44

These three bills were expressly intended to give

content to the freedom conferred upon the Negro

by the Thirteenth Amendment by guaranteeing to

him all of the civil rights to which free men were

entitled.

These measures were related to the Fourteenth

Amendment by more than mere coincidence of

time “ and subject matter. As will appear infra,

pp. 40-45, the latter was proposed after members

of the Congress stated that the civil rights guar

anteed by statute were vulnerable to future politi

cal changes or might possibly be stricken down as

unconstitutional. Because the rights intended to

be secured to Negroes by these measures were the

same as those subsequently embodied in the Four

43 A ll references to the Globe in this section are to the Con

gressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Session.

44 The Supplementary Freedmen’s Bureau bill (S. 60) was

debated in Congress from January 11, 1866, through Feb

ruary 20, 1866: the Civil Bights bill, from January 29,1866,

through April 9,1866; and the second Supplementary Freed

men’s Bureau bill (H. B. 613), from May 22, 1866, through

July 2, 1866. Meanwhile, the two precursors to the Four

teenth Amendment, the Stevens “ apportionment” amend

ment and the Bingham “equal rights” amendment, infra,

pp. 33-41, were debated from January 23, 1866, through

March. 9, 1866, and February 26 through 28, 1866, respec

tively. Debate on IT. J. Bes. 127, containing the Fourteenth

Amendment as finally proposed, extended from May 8,1866,

to June 13, 1866.

280315— 58------3

2 2

teenth Amendment, it is appropriate to include

their legislative history as a relevant part of the

background of the Fourteenth Amendment.

(a) Immediately following President Johnson’s

message of December 5, 1865, stating that existing

state law furnished adequate protection for civil

rights, the 39th Congress established a Joint Re

construction Committee to serve as the principal

agency for developing the program of “ Congres

sional reconstruction.” (Globe, pp. 6, 30, 47.)

Senator Wilson immediately brought up for con

sideration a bill (S. 9 )45 to nullify the Black

Codes. (Globe, p. 39.) He urged Congress to

strike down these Codes without delay, so that the

Negro freedman

can go where he pleases, work when and

for whom he pleases; that he can sue and

be sued; that he can lease and buy and sell

and own property, real and personal; that he

can go into the schools and educate himself

and his children; that the rights and guar

antees of the good old common law are his,

and that he walks the earth, proud and erect

in the conscious dignity of a free man * * *.

(Globe, p. 111.)

The chief opposition to W ilson’s bill came from

those Senators who considered all civil rights

proposals as an unwarranted effort “ to confer

on former slaves all the civil or political rights

that white people have.” (Globe, p. 113.) The

45 A ll bill numbers hereafter cited in this section refer to

bills in the 39th Cong., 1st Session.

23

bill was, however, withdrawn by Wilson because

of the evident view of the majority that measures

of such a nature required more careful formula

tion. Senator Trumbull undertook this task. He

subsequently introduced two bills which, he stated,

would effectively protect all men in those basic

rights without which they would not be free.

(Globe, p. 43.)

(b) One of the Trumbull bills (S. 60) proposed

to extend the life of the Freedmen’s Bureau and

to enlarge its authority; the second (S. 61) was

intended to protect all persons in the exercise of

their civil rights and to furnish a means by which

those rights might effectively be vindicated.

(Globe, p. 129.)

The purpose of S. 60, as stated by Senator

Trumbull, was to restrain by military measures

any attempt to enforce the Black Codes. (Globe,

pp. 319-323.) The bill passed the Senate by a

wide majority. (Globe, p. 421.) The opposition

centered their attack on the basic concept of

equality underlying the bill, and on its military

enforcement provisions. (E . g., Globe, pp. 318,

319, 342.) The debate in the House emphasized

much the same issues, with the additional matter

of education for the freedrnen. (E. g., Globe, pp.

513, 585.)

There was little difference in the majority and

minority views concerning the bill’s scope. Its

proponents expressed their understanding that the

equality to be enforced did not mean “ that all

24

men shall be six feet high,” but rather that they

were to have “ equal rights before the law,” so

that it “ operates alike on both races” and without

“ discrimination against either in this respect that

does not apply to both.” (Globe, pp. 322, 343.)

Nor did the opposition indicate any disagreement

on that score. They objected, rather, to the gen

eral philosophy of the bill. Representative Daw

son of Pennsylvania observed that the bill con

stituted only a part of a broad policy to enforce

absolute equality for Negroes so that they

should be received on an equality in white

families, should be admitted to the same

tables at hotels, should be permitted to oc

cupy the same seats in railroad cars and

the same pews in churches; that they should

be allowed to hold offices, to sit on juries,

to vote, to be eligible to seats in the State

and national Legislatures, and to be judges,

or to make and expound laws for the gov

ernment of white men. Their children are

to attend the same schools with white chil

dren, and to sit side by side with them.

(Globe, p. 541.)

Several Congressmen objected to entrusting the

Preedmen’s Bureau with the responsibility of

educating the freedmen because it appeared that

the Bureau had taken over certain white schools

in the South for the use of Negro children. The

charge was made that “ unless they mix up white

children with black, the white children can have

no chance in these schools for instruction.”

(Globe, App. pp. 71, 82.) There is no other evi

dence that any particular thought was given to

the question of racial segregation in the existing

schools. The bill was passed by the House, but

was vetoed by President Johnson in February

1866. (Globe, pp. 688, 915.) The Senate sus

tained his veto. (Globe, p. 943.)

(c) After the Senate passed S. 60, it turned

immediately to consideration of the second of

Senator Trumbull’s bills, S. 61, the so-called

“ Civil Rights” bill. (Globe, p. 421.) S. 61 pro

vided (1) that there was to be no discrimination

in “ civil rights or immunities” among the in

habitants of the United States on account of

color, race, or previous servitude, and (2) that

all persons, regardless of race or color, were to

have the “ same” rights to make and enforce con

tracts, to sue and be sued, to inherit and own

property, and to have the full and equal benefit

of all laws for the security of person and prop

erty. (Globe, p. 474.) Violation of any of these

rights “ under color of law” was to carry both

civil and criminal penalties. (Globe, p. 475.)

The purpose of the bill was stated to be the

nullification of all state laws which, on grounds

of color or race, deprived “ any citizen of civil

rights which are secured to other citizens.”

(Globe, p. 474.) The Senate proponents of the

bill explained that the freedom conferred upon

Negroes by the Thirteenth Amendment was of

little value, unless they were given “ some means

26

of availing themselves of their benefits.” (Globe,

p. 474.) So long as there were state laws dis

criminating against the colored people, they re

mained in part slave. Any statute

which is not equal to all, and which de

prives any citizen of civil rights which are

secured to other citizens, is an unjust

encroachment upon his liberty; and is, in

fact, a badge of servitude which, by the

Constitution, is prohibited. (Ibid.)

To the objection that the bill’s purpose was “ rev

olutionary” , its supporters answered that the

country was “ in the midst of revolution.” (Globe,

p. 570.)

The opposition, recognizing that the bill was

intended to accomplish “ the abolition of all laws

in the States which create distinctions between

black men and white ones” (Globe, p. 603), ob

jected to this attempt to “ place all men upon an

equality before the law.” (Globe, p. 601.) They

claimed that the Thirteenth Amendment did not

confer the power on Congress to erase distinc

tions between Negroes and whites created by state

law. (Globe, p. 476.) For them, the Amendment

had merely abolished the “ status or condition of

slavery” , and there was no justification for at

tempting to use it “ to confer civil rights which

are wholly distinct and unconnected” with such a

status. Senator Cowan of Pennsylvania, oppos

ing the bill, referred to the system of racially-

segregated schools provided for by Pennsylvania

27

law as an example of the kind of legal distinction

which would be eradicated by the bill:

In Pennsylvania, for the greater conven

ience of the people, and for the greater

convenience, I may say, of both classes of

the people, in certain districts the Legisla

ture has provided schools for colored child

ren, has discriminated as between the two

classes of children. We put the African

children in this school-house and the white

children over in that school-house, and edu

cate them there as we best can. Is this

amendment to the Constitution of the

United States abolishing slavery to break

up that system which Pennsylvania has

adopted for the education of her white and

colored children? Are the school directors

who carry out that law and who make this

distinction between these classes of chil

dren to be punished for a violation of this

statute of the United States? To me it is

monstrous. (Globe, p. 500.)

No member of the Senate rose to differ with Sen

ator Cowan’s view of this objective of the bill.

The attacks on the bill failed, however, and it was

passed by the Senate in February 1866. (Globe,

p. 606.)

In the House the bill was reported favorably

by the Judiciary Committee, of which Congress

man Wilson of Iowa was chairman. (Globe, p.

1115.) The debate in the House followed the

same general pattern as in the Senate.

28