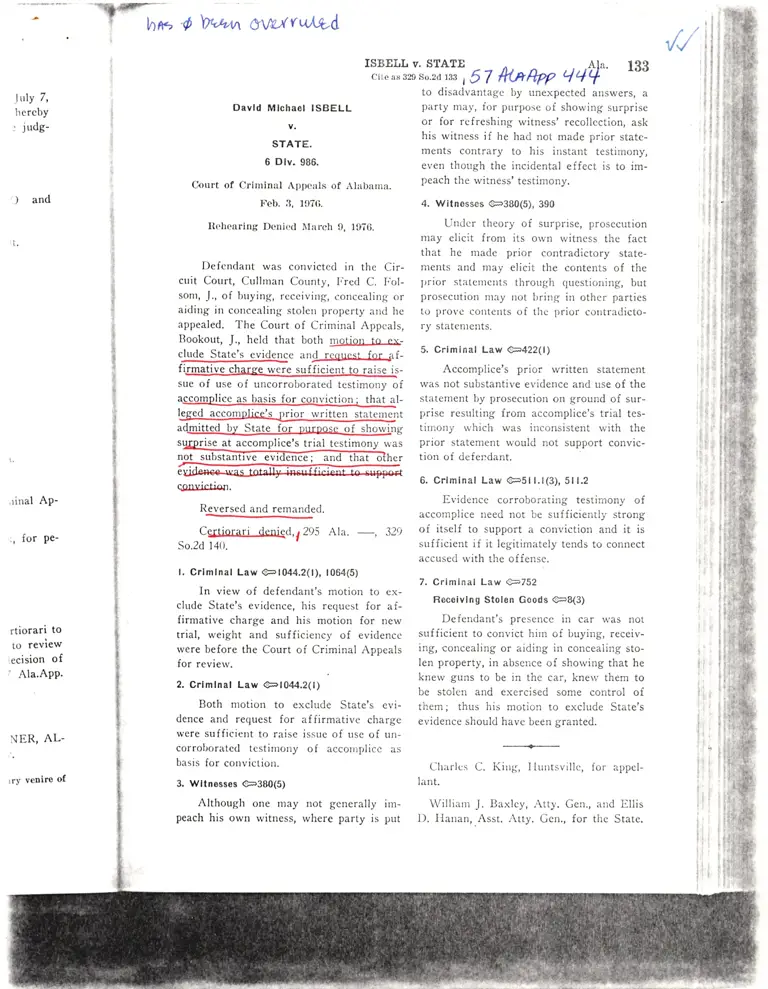

Isbell v. State Court Opinion

Working File

February 3, 1976

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Isbell v. State Court Opinion, 1976. 82561f4f-f092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8db868e9-2c4f-4ac8-b020-38181eb17009/isbell-v-state-court-opinion. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

lnx,., O \lqh,n JVu{tw\Ld

Davld Mlchaol ISBELL

v.

STATE.

6 Dlv. 986.

Clourt of Crirninrrl Aplxr:rls of lllrbirnrl.

Ifel). il, :lt)7(i.

Ilt'hcrrriug L)cnictl Ilrrrtir 1), ll)7(i.

I)efcn<lant was corrvictcd in thc (lir-

cuit Court, Cullrnan Oorrnty, [;rcrl C. I;c,l-

sorrr, J., of brrying, recciving, (:ollccalillfl ()r

ai<ling in corrccaling stolcrr prollcrty arrd hc

appealed. The Cotrrt of Crirrrinal Apprals,

Bookout, J., hcld that both nrotion to ex-

clude Statc's cvidqncc and rcc$rcst for jrf----ft-rmative charge wcrc sufficient to raise i:-

sue of use of uncorroborated tcstinrony of

accomplicc as basis for cont'iction : thxt irl-

lsged acconrrrlice's lrrior rvritten strLtcrrrcnt

ad.gjtted lrv State fomf

surorisc at accomplice's trial tt.stimony uas

not sut,stantive evidcnce: and that o{hcr

caryiclior.

Reverscd and remanded.

Ccrtiorari de niqd, 12()5 Ala.

-,

32r)

So.2d 140.

L Crlmlnal Law @1044.2(t), 1064(5)

In view of defendarrt's motion to ex-

clude Statc's evidcnce, his requcst for af-

firnrative charge and his motion for new

trial, rveight and sufficicncl'of evidencc

rvere before the Court of Criminal r\ppeals

for revierv.

2. Crlmlnal 1-"* 6=1gr14.2(l)

Both nrotion to exclude State's cvi-

dence and request for affirmativc chargc

wcre suf ficicnt to raisc issr.rc of trsc of ult-

corroboratc<l tcstirrrolry of accorrrplit:c as

basis for currviction.

3. Wltnesses e=380(5)

Although one nray not gcnerally irn-

peach his owrr rvitness, rvhcre party is prrt

'11

.1r { .r..'#,

. i'+

t' ,':

i,r

ii

:f;j

;,t,

.J::''.t

' :;*r

'u

I

ifi,:.ry.

9rl

'i r,

ISBELL v. STATE ^ Alt.

( i:o as rre srr.r,]rr r3r| | 5 7 /+lnfu r/ 4 rt

,lJ

133

lrrly 7,

lr crclly

judg-

) and

i.

riual AP-

, for pe-

rtiorari to

to review

ecision of

Ala.APP.

I'llilt, AL-

,r)' veniro of

to disadvant:rgc by rrnexpectcd allswers, a

I)arty nla\', for prrrposc crf shou.ing surprisc

or for rcfreshing rvitness' recollcciion, ask

his witncss if he had not ntade prior statc-

mcnts contrary to his inst:rnt testinlony,

cvcn though the incidental effcct is to irn-

peach the u,itness' testimony.

4. Wilnosscs e3B0(5), 390

Llntlcr th,:ory of surprisc, 1;rosccution

rrray elicit fronr its or','n rvitr-rcss the fact

that hc rn;tdc prior contradictory statc-

rncnts and nray clicit the conteltts of thc

lrrior stlrtcrrrcrrts thror:glt <lucstiorring, lttrt

prosecution r1l:ry n()t lrrirr{a in othcr partics

to l)rovc colltcllts oi thc prior culltl'ldicto-

r)'statcnlellts.

5. Crlminal Law 9=42211;

Accomplice's prior u,rittelt statcmcrrt

was r)ot substantive evidencc and rise of the

st:rtclnerlt by prosccution orr grourrri of srrr-

1.,risc rcsulting fron-r acconrplicc's trial tcs-

tirrtorty rvh:ch rvas inconsistent r*,'ith thc

prior statenrent would rlot support convic-

tion of defcndant.

6. Crlminal Law C=5ll.l(3), 511.2

Ifvidcncc corroborating testir,ton-\, of

accontplice need not be sufficientll' strong

of itsclf to support a convictiou and it is

suf ficicnt if it lcgitimatcly tcnds to conrlcct

accuscrl rvith the offer:sc.

7. Criminal Law (>752

Receivlng Stolon Goods eE3)

])c fcndant's prcsr:rlcc in clr u'as not

sr.rf ficient to convict hirn o1- Luying, rccciv-

ing, concealing or :riding in conceaiing sto-

len property, in abscuce of shorving that he

knerv guns to be in tirc car, knerv them to

l.le stolr:n and exercised solle control of

ti.lcrn; thus his ntotion to e.xclude State's

evidcnce should havc been granted.

(.lt;rrlcs C. I..irrg, I ltintsvilli:, ftrr lilrpcl-

luut.

\\/illirLnr J. Ilaxlcy, ..\tty. Ccn., arrd i:-llis

l). IIauarr, Asst. .,\tty. Ccrr., for tlrc Statc,

- t--rr4i -L +- ,.j,*k-._.

j, $;

134 AIa. 329 SOUTEER,N R,EPOR,TEB, 2d SERIES

tsOOKOUT, Judge.

Buying, receiving, concealing, or aiding

in concealing stolen property; sentence:

three years imprisonment.

The appellant in this case was charged

with burglary in the second degree in

Count I, grand larceny in Count II, and

buying, receiving, concealing, or aiding in

concealing stolen property in Count III.

The jury returned a verdict of guilty of

Count III as charged in the indictment.

Phillip Taylor, the State's first witness,

testified that he had gone hunting on No-

vember 19, 1974, and that his wifc had

gone to Huntsville to visit someone.

When he returned home oIr the 21st, he

noticed a hole in the back door and found

the following items missing from his gun

case: a Remington ,72 gauge shotgun, Se-

rial No. 5L97701; an extra barrel for that

gun; an H and R muzzie loader; a .45

caliber gun, Serial No. AL208721 ; a .22

caliber single shot rifle; a Winchester

Buf f alo Bill, 30-30 ri f le, Serial No.

114567 ; a Bcar Kodiac, Serial No.

KT495591; a S2-inch Shakespeare arrorv

bow; a Universal scope; and a quiver of

arrows that was attached to the bow. Ife

estimated the value at $650.00 to $700.00.

All of the iterns belonged to Phillip Taylor

except the .22 caliber single shot which be-

longed to his father.

Taylor stated that he had been knowing

the appellant approxinrately fifteen years,

and the appellant had been a guest in his

home from time to time. The appellant

had been in his home approximately one

month before hc left on his hunting trip,

and he believed that he asked the appellant

to go with him.

On cross exarnination by the defcnsc,

Taylor said that he saw the appellant ncar

the Star Cleancrs in Arab the day aftcr he

discovcred the theft. I'Ie testificd that hc

knew the appcllant was majoring in larv

enforcement in collcge. The appellant said

that he "nright know something" about the

break in and said "Well, I have some

fricnds, lct nre ask some questions." Tay-

lor then asked appellant to let him know if

he found out anything about his guns.

Taylor testified that he got the guns back,

receiving them at the police station in

Arab on the rnorning of November 27,

197 4.

When Roy Michael Whisenant was

called to the stand, counsel for appellant

inforrned the trial court as follows:

"Your Honor, I have interviewed this

witness and his testimony may tend to

incrinrinate him, and I think that he

should be advised of his fifth amend-

ment rights before he testifies in this

case.

The above statement was not made as an

objection, and the court proceeded with the

casc. Whcreupon, Whisenant testified that

he was with the appellant on November 26,

1974, at about 7:00 P.NI. when he picked

up the appellant at his home. Whisenant

had already gone by Ricky Harper's house

and picked him up at 6:30 P.M. After

leaving thc appellant's house, they drove to

a dirt road near Thompson Falls. They

stopped, and the appellant and Harper got

out of the car. Whisenant said he had

been awake three days studying for exams

and was sleepy and may have dozed off.

I{owcver, he rernembers the appellant and

Harpcr getting back into the car. He stat-

ed that he did not see them put anything

into the car. After he heard the door

shut, he looked in the back and saw a large

black'plastic bag.

The trio drove back by the appellant's

house for him to get his coat. The appel-

lant went into his house, and Ricky Harper

stayed in the car with Whisenant. While

the appellant was in his house, Whisenant

looked in the bag and testified that it con-

tained guns. Ricky llarpcr did not testify

in thc trial.

Whisenant said he suggcstcd carrying

the guns to shorv thenr to his cousin in

iVlorgan City, as his cousin was an avid

huntcr. Whisenant stated that neither thc

'l'ay-

rorv i f

Huns.

lrack,

, rrr irt

'r 27,

was

,t'llant

I this

nd to

;tt he

rncnd-

r this

as an

th the

,l that

er 26,

icked

enant

Irouse

A fter

,ve tO

They

r got

had

xams

' off.

: and

stat-

r hing

door

large

;ant's

ppel-

rrper

/hile

'na nt

cott-

sti fy

yirrg

rt in

avid

' the

I$BXLL v. STATE

appellant nor I I,

c'ito rs 320 so'etl 133 Ala' r35

thing about s.i,l:I;.1::,j1"1!':':',1."1'J; [j, ;1 ;:;,;[",,:0,e,

whisenant statecr

aPpellant strggestecl ,u[ins ,r,.-;;;,

.,,i

::::,:: i.l'j,1^.:

there. hirnsclf. 1r,.1.o,-Phillip T"ylo.;. hor.". to

"9t'h9r-ilgim,clq-$Ipl1,9 and brought otrt-

-Ji: ffl':;, fii!l:"r.y,liil,T:::,,:;,:i: i,"} tr [ltlif:#{,,**- li;for rcckless <lrivirg. AII threc *;;;;^;;; givc, to tlrc porice chief whire in jair. Thcto jail' whirc i, jair, whis,ra,;;';;,,;',, statcjrcrt ,un. ,.n,t ovcr trre objection ofsworn statentc,t. t'c <Jc,fc,sc, prrrportc<lly for t'c purpose ofr)rrrirrg whise,ra,rt,s,<rircct exanrination, [tJ:::]iH#;T:i.r:,,:]"; ;n';fi;.,r.

the trial judgc stoppca the testim;;;.;;o

excused the jrrry from the .o,,.t.oo,,.' ih. ,,,I, Roy whiscnant, rvc,t to Ricky FIar_trial jtrdgc tlrcn statcd intcr ulia: '

Pcr,s horrsc. Ricky a,cl nryself *.,ri ,o

;;i::'',.]f':J;' il"Xl,l,? 'li 'l::,i:ll ll[: l;X':hTr"'ii:'1" nltfjknowleclge o. ,.oron ," i'^r.'u,iJ,X,.illil lialls' Mike and Ri;;;"..; ,'iil"iroor rcason to r,.ulllntnt:,ii::.T:IJ..f. ,"-. *r,,^,hly ,,eeaea to sel. Rickylen guns, or that

erty or the .vo ,.ln'-,

y*. ,"i i*;#- ,T#,'L.,I il*::":lo r.u.,-l",ion."'r

;:th;1ffk:r il,#I [il. rilr Jy;:";t#".T.i.kll

point, it is possible that you'."r,J'n"r"t son Falls

-and got iour g.uns, anotherbccome possibly guilty of aiJ,,;;; ;;: !1".,. an<.I .cope. we left there ancter concealing or aiding in ,r,. Jon..rirg ::t bi:l to_ Arab. The police jaor.o

of. stolen property. s", , i..i"u "riX

us on 10th Street, N.W. W" r,"a'ir,.fair to tell you ,ir"r

"ro ;o;;r: ;"r"":1

guns in the back seat. I did not know

:Ffi::ir;:1J',:,:::,lTiy"fn.ffi

the g'lr,s in n,v car werc storen."'

,[,T:: ;:'i *ri:{.t .ff , #:J;3 j},t'fi ",11[-,T: *,T::'l;'iii',,*-

;'::;"1:'i"1:;*'3:::'" ?"""''#"" fffiffi T::

'y'li:'"il:

'::::o ffi*:

r*ix xt [i ffi r',.J LT,H, Ti .1il I i l;lt]

ti:;u;:';",,T;

il""f

yotr, yo, have a right to refuse to an- Lt"l ."*"u-t for approxim"r.ry,rrr." ari.]

swer them on the

l.oy:d, tr,"t it .;gr,t

:]::i,J'H.j";. T[-":.#:;:.*.:lru:;tend to incriminate me.,, he had t;ke; ,o]r. ,,ro_Oozc,,

and someThe prosecuting attorney then stated to prescription pills to stay awake and that hethe court that thc *itr.,..""1,.,',:^'^:',":

t"

imnrunity, il;;;; ,:J111:'"iil,l::,":,;:: ;',f,i'j':':i,ij:',""T l:.,::x,:,';::r:.1*the grarld jury and testified.

'lr"

.i,,,.i,- cxamiratro,,, ttr. ,r"xt morning. whisen_the court that the rvit

1.,,1it,{ u*ni,,.i'i;,,,,"1;:i,li: il :|l.1:i:: li",,il'1,"1'i.1: ff,,'llJ'"'

n':ake a statement

worrl<l bc ,,,r.,rf

'

,,*,,;rrst lirrr. .t.t,c t,j"t .llarle r ,,,,,, U,,,i ;;;;rtt1l,,ll "::i,,l"l.rlll.1]

ili-;,.',",1:::.Jl.l,;,1,,,:r"rorr,. .o",t,ou,,

iij.:1,!.:: +*;;:ll,;*::;* ;lflI

Arter runch, whisenant continuecr his ;i',i.:t:,T?:lT:.:-":#r,;: #a;{,j.jiltestimony' but when asked how *;,;;; notscethemputthegunsinhiscar.

whise_

r

136 Ala. 329 SOUTIIERN R,EPOR,TER" 2d SERIES

nant said that after the appellant saw,the

grn, ;n the back of his car' the appellant

iuggested going to Phillip Taylor's house'

Wilr.n"r',t

"gain

stated that he put the guns

in the car himself.

Chief Jack Banister, of the Arab Police

n.p"rt."nt, testified that on Novcmber 26'

1974, bet*een 8:30 and 8:45 P' M'' he saw

Vfit. Wfrit.nant, Robert Harper and the

"pp.ffrn,

when they were brought to the

poiic" st"tion by Of f iccrs Bradford and

Mazc. I'Ie stated that he was called out to

a car containing sonrc guns which had been

.lrir",t to thc station by Olficcr Ilradford'

Vernon Bradford, a policenran for thc

City of Arab, wis one of the arresting of-

ti"..r. He arrested Whisenant for reck-

less driving and arrested Harper and the

appellant for disorderly conduct' Officer

Bradford said that he saw the stolen items

in plain view inside Whisenant's car at the

tinre of the arrest. Larry Waldrop' a dep-

uty sheriff of Cullman County' and James

i^rr, ^

deputy sheriff of l{arshall Coun-

ty, both testified to the description of the

siolen items and accounted for the chain of

custody.

has endeavored to preserve any and all er-

rors possible for review by this Court' nV

appeliant's motion to exclude the State's

"rid"n..,

his request for the affirmative

charge and by his motion for a new trial'

the ieight anci suf ficiency of the evidence

is indeecl before this Court for review'

12) Both the motion to exclude the

Stut.'. evidence ancl thc request for the af-

firmative charge are sufficient to raise the

issue of the use of uncorroboratcd testimo-

rry of an accortrplice as a basis for convic-

tiou. Alerandcr z'. Slote,28l Ala' 157'2M

io.Z.l a88 0967); l'cottrd t" Stotc' 43

Ala.App. 454, LgZ So'2d 461 (1966); l'ctt-

pl.cs a.^ Stote, 56 Ala'App' 290, 321 So'2<l

257 (re7s).

tll At the end of the State's tcstimony'

the deferse moved to cxclude the Statc's

evidence on the grounds of lailure to

prove a prima {acie case and the insuffi-

.i.n.y oi the evidence, which among other

grorndr, were stated in detail to the trial

Iorrt. The motion was overruled' The

ldefer.lttt "etl"e't"tl the af firmative charge

lrna ,n. a{f irmative charge with hypothe-

lsis, which were refused' Counscl for ap-

pellant likewise filed a motion for a new

irial, challenging the sufficiency of the ev-

idence and setting forth numerous other

grounds. The trial court ovcrruled the

irotion for a new trial, and counsel for ap-

pcllant then filcd in the record on appcal'

tlrrity-ninc assigrrmcnts of error' Al-

though assignments of error are llo longer

n...fr".y in a criminal appeal per Title 15'

$ 389, iode of Alabama 1940, counsel for

ippellant, out of an abundance of caution'

I

The issue pr€sented by the appellant is

whether Whisenant's statement was cor-

roboratecl by other evidence' This becomes

an issue only if Whisenant's prior rvritten

statement was admissible and if it may be

considered substantive evidence of the

crime charged.

The only statement incriminating to the

appellant, made by Whiscnant in the coursc

oi thc trial, did not come fronr thc rvitness

stand, but was a statemellt purportedly giv-

crr to Chief Banister after his arrest' and

read into evidence by the District Attor-

ney.

Whisenant's verbal testimony in the trial

was not incriminating to the appellant' It

*o, onty rvhert thc prosccution claimed

surprise that the irrcriminating statcment

came into evidence in anY form' The

pror...ttlon rvas undoubtedly surprised by

testimony favorable to the defendant com-

ing f ,orn the State's chief witness who

,,r"pposedly $'as to testify against the de-

f cndarlt.

t3] Cascs in this jurisdiction indicirtc

that although one may not generally im-

peach his own witness, therc is an excep-

iior,. When put to a disadvantage by un-

^

In Jarrell zt. State, 3.s Ala.App. 256, S0

:::o^!:! !re4e_s,), "ft". ,.,,,in.i,,;,;; ;;rrt:

-

r\laDama Supreme Court, this CorrJtheld at p. 263, that the ,ror..rr,r!"

"r_,?.n., should have been

"lfo*.i ioclarify inconsistent statements of a State,switness. In that case, the *ir.*, *rr.evidence which was contradictory in someaspects with previously given ;.";il;;;:The prosecution asked ir,. *ii"..r";.;iiquestions with reference to his former

jl:jt*on{,-. directing his attention ,;';:tarn specific replies to questions, ,na ort.awhether or not those

tr,u,, *," .u;:;.".'.i1'n"I'11,L".'.filll_

ing statement was properly put beforeth,e jurr in allowinj the prosecutor toask the witness if he iad rnoa. ,r.i-.ir,.]

ments.

t4] It, therefore.

tr,

" ti,. o,y

"

i' .,"r,,,", ii$J;.:ii I"

",,;0".Jelicit fronr a witness ,n^, i.-i,"i":;';,::iprior contradictory

s

.r i"i t,;;; -;;;" J,,,'i:i' [':":";;1,,.," :iprior statements through qr.,.r,iorir;,' ;;o;_ever, the prosecution rvorrld not l;e al-lowed to bring in other partics to provc thccontents of the prior contradictory statc_nrents.

In thc irrst:rrrt cast

11u", 11, ..1

icit..l' ;;' ;,,lJi,;;'J'il:"L?ness. Chief ljanister r

prosecution ,o ,r"r. ;"rlt #,H,"j y :l:

329 So.2d_gy2

ISBELL v. STATE

expectea answers, a party

"r"r, ,:;r'",;J2e

so.2(r r3rJ Ala' 137

lu'l:'" of showing surprise .. i., ,.- ;H:ffi';;.":JJIT'"'. .1j1". rrci,g sur-treshing the witness' recolection, ;;i il; i;'.',t":.j"^::t

testinrony of \\&i..roni, ih.witness if he h;J;ot nrade prior state- ,?::l.|:t

Attornev cngagcd him in th;';i:

T;::,:

co.tr,lry. to his irsta,,r'

-,..",,,,",,r- ro*rrrg qrrcstiorrs:

I nrs ts permissible, aftcr proper pr..li.;;.; "(J. Arrd I will stcven thorrgh its inciJe,tar

"ii."t l, ; ;;r] p^pcr a.d o.u ,o,lol, 'rl"'r,

tli;,r1[t:n:i

peach the witness' tcstinrorry. Edr;,;;;";,,. piccc of n,,n.., 'r,r"r" ;rt 9:15 or about's/o/c, 5l AIa.App. 'l.l.l,.2li6 .s".za ii,s,'.,,". th:rt tirrrc, p.';-,.,';; rhc policc station of<lcrricrl, 291 Ala. 277, 2s6 su.za .ir.r , i;.;i, .\r-:rtr i, ,u. f r...,,,.c of Of ficcr J;rckts <ltrt'ctly in poirrt. Also scc, Mor),,,',r'l' Ir.rriste. ,,r.r i;;;,;rd i\Iartis? Is that

)!:,::_ ,, AIa.App. 616, tyz S".z;l ;; yotrr sigrrature ?jlr.fti ; IVootts 2,. S.totc, V ,lt^.A,p:,p,. iii,

li"i:'t s3s.(lesl), lr.Er.or, L;r;'";;;: "A' rhat is mv sig,rarrrre on the papcr.

tderrce ;n Alubauo (2t

(a), p. .1g7.

tcl ed.), $ 165.01(7) "Q l)id you sign it at that tirnc?

"A. yes, sir, I dicl.

"0. And to refresh your recollcction_,,

After scveral objections and voir dire ex_- amination by defensc

statcd:

: counsel, the appellant

"I nevcr said that thcy had any guns toselL"

The I)istrict Attorncl. then s1"r.6, .n

pertinent part:

this statement, nolv and I r.r,ill ,.^a ii-i"you frorn the stal

about z:r5?,,

:cnletlt ort 11-26-74,

_,\nothcr tlefensc objection u.as overruledwhercupon the District Attornel. read thestatement and conclu<.lea Uy astin* ,r-',,were true. Whisenant stated, ,,That

state_ment is falsc. I signed it, but ir i.

"r"ir..,;

. Assuming, from ihe forcgoing authori-Jties, that it rvas prope, fo. ,i. n?o;;;;,; Ito questio, its rvitness i,, tfre ofrou.';;;_ lner, was rhc sttrtemcnt read by tt" Ol.t.ict IAttorrey substantive .ula",,." ,i in;;;, icharged? -- "'" -""'"al

.,,, It ##, ffi' ;,,xr., fl,, il,,l

jil:,lj j] i,'*,rrrrpcirchrrrc.t is [.r thc 1,,,.1ru.r" .f ,;,,;;;;_ /irrg thc :tdvcrsc cffcct rri ,;r;,rr;',;;;;;_\

ny, and canrot bc uscd fo,

"uy ",1r.; ;;;_ )p!se. Unitett S/arcs u. Dubis, ++S i.)a \1262 (1971) (5th Cir.). r" poi,,t ,"Un'ii" \

.:!: Ili

.3',

i:,i

I

I ii ,.

,r'l

t,

138 Alo. 329 SOUTEEB,N R,EPORTER,, 2d SEN,IES

principle at issue in the instant case is the

statecl the view that, when caught by sur-

prise, a prior inconsistent statement of a

p".ty't own witness is admissible for im-

peachment purposes, but such statement

cannot be used as substantive evidence of

the facts stated. That Court went on to

quote the rule that, " . 'if the onlY

evidence of some essential fact is such a

:r.:,":t

s:ltement, the partv's case falls'

Eisenberg, cites Southetn Roilway u'

Gray,24l U.S. 333, 36 S.Ct' 558, 60 L'Ed'

l03d (1915), wherein the United States Su-

preme Court held that:

" . the contradictory statements

can have no legal tendency to establish

the truth of their subject-mattcr' Don-

aldson tt. New Yor&, N.H' & H' R' Co"

188 Mass. 484, 486, 74 N'E' 915; Mc'

Donald a. New York C' & H' R' R' Co''

186 Mass. 474, 72 N.E. 55; Com' a'

Starhweather, 10 Cush' 59; Sloan tt'

New York C, R, Co.,45 N'Y' 1251' Pur-

dy u. People. 140 Ill. 46, 29 N'E' 700'"

Alabama, as early as 1888, adopted the

rule that rvhile a rvitness may be im-

peached by the use of prior contradictory

statements, that such statement, " '

should not be treated as original evidence

of the facts of the case, nor be received

for any other purpose than that of contra-

dicting or impeaching the witness-Iones

a, irlhorn, 84 Ala. 208, 4 So' 22'

." KennedY u. Stote,85 Ala' 326' 5

So. 300. The Courts of this state have

consistently held that the use of prior in-

consistent statements, as used in the instant

case, may not be considered as substarltive

evi<lencc to provc the crinrc' I'cwis a'

State, 44 Ala.App. 319, 208 So'2<l 278

(196tt); Lynn u. State,37 Ala'App' 4Ot)' 69

So.2<1485 (195a); S'kinncr a' State,3(r Ala'

App. 434, 60 So.2d 363, cert' denicd, 258

Ai". ZtS, 60 So.Zcl 367 (1952); Brown u'

Stote, 3l Ala.App. 233, 14 So'2d 596 (1943)

'

cert. denied, 244 Ala, 597, 14 So'2d 598;

Manning a. State,2l7 Ala. 357, 116 So' 360

(1e28).

The latest expression on this point of

Iaw by the SuPreme Court of Alabama

comes in the civil case of Cloud a' Moon,

290 Aira.33,273 So'2d 196 (1973)' Justice

I{errill, citing Lczois and Eisenberg, stt-

pra, held that the prior inconsistent writ-

ien statement of a hostile witness called by

the plaintiff could not be used as substan-

tive evidence to establish the defendant's

liability.

Thc Kcnnedy casc, supra, indicates that I

the properunet-hod of limiting the effect of

I

the impcaching statement would normally I

be by proper instruction given to the jury'

I

Ilowever, where the only evidence incrtmt- |

nating to the defendant is the impcaching I

statement, a limiting instruction would not I

be appropriate, since the insufficiency of I

the evidence would not justify the case I

being submitted to the jury, unless it tre

I

strbmitted on the affirmative charge re- |

quested by the defendant. J

t5l Thus, Whisenant's Prior written

statement, not being substantive evidence'

rvill not support the conviction'

II

The next issue is whether there was "tn- J

er evidence, from rvhich the jury could I

draw an inference o{ guilt, to warrant *O-

Inlission of the case to the jurY'

In the instant case, the appellant was an

occtlpant in Whisenant's automobile several

days after the theft was discovered'

There is no evidcnce whatsoever to con-

nect the appellant with the break in or the

theft. There is only evidence that he was 'l

riding in an autonrobile, owned and oPerat-

|

ed by anothcr pcrson in which the stolen

/

guns were found.

tn LVhitc a. Stotc,48 Ala'App' lll' 262

So.2d 313 (1972), thc fact that thc appel-

lant, when arrested, was in the automobile

of another, which contained the proceeds

:

I

a.Z<l 598;

, t,' SO. 360

lxrint of

Alabama

t,. Ill[oon,

t. Justice

,bcr.r/, srr-

lent writ-

called by

r srrbstan-

.: f endant's

,'atcs that

effect of

norrnally

the jury.

. incrimi-

rpcaching

.,,'ould not

,:iency of

the case

css it he

rarge re-

rvritten

cvidence,

was oth-

ry could

r'ant sub-

t was an

rl S€v€f2l

,covered.

to con-

rn or the

I he was

.I operat-

're stolen

|1, 262

rc appel-

tornobile

proceeds

ISBELL v. STATE

of a recent robbe cite es 3t9 So.2rl 133 Ala' 139

ration or ,n" ,..,';];; :f::Tj.:#} surricient to..-support the co,victiorr, stand-

whe, corrprecr ,uitr,. c,ij",;J.;; ;;;;;:-."? ::T."1:":i,. 1,1i,i,.j.,.,1,.i,,::,,::"'*i:;:*thc crirrrc. ttu":]:.,- i,., t,t,;yii,.".i,'o,", helcl to fr. .uifl.i.r, to corroborate the tes_

44 Ala.App. 611, Zt7 So.2d B;i i',rori,'",. timony

"i ,r,"..".0,,... It is well settrecl3;:',H:,,i:"j;:t1:::":j:t*, that c,ia"r,c"1-,l..,r,u,uting trrc testimorly

Iant u,as ,,....,.J'Ll;ilfiJ:.i:il: :lj_:I;;XJii: n..,r n<,i r,. ,uir.r.,,try

l:#r::::^,:1j," riding i, *," ".r,ir. i. .,,iri"*,,-;;.,;"I")l,,T:l.ir.,"Jllii,il..;,,j

r|restion." ,r",,.i:; li:l;,' .:::i"'jlr,"' ':rcct

thc accuscd witrr the offense. c,u,-

considcrably fror, thc i'sta,r .o.. ,,., .."-lt

tli1qlam z'' stulc,.5'l.tr^..tpp. r,ii, jri.i".

cral aspccts.

- "'e rrrrr'tltL casc rl) scv- 2d ttZ (1975); Kel_src !. .st,';;,;-,"n;;r,

l7(), 306 So.Z<l ,l), ct.rt. tlcrricrl, 29.1 Ala.ln I'hiffcr, tltcrc rvas testir,ony by tlrcc 761, 306 so,2a .sil (1954); tr[/ltitc, supra.State,s witnesses who saw th;".;i,r;";proS'ress. They s.rw, white nui.l The appellant co,r"cncls that arthough hc

*o1' " '62 or '63, ancl had un E^t wto.x rvas in thc automobil" i, which ,,r.-lrr."Reef tag on it ,,

,, and saw ,, ,tw^ items were founcl, that th" arto*oirl;-;.colored fellows behind ,rr. ."r-*i,r, ,il longc<I to whiscnant and thus the stolentrunk up.' .,,

.one,-,r, f",".-*"li_ guns were in Whisenant,s constructiu. ro.ing down the street-with a t.l."i.i"; ;;;';; ::.-''"., .{.:gglgg, -!t,e!,!.,i, ;;""rGeach hand, and one State,s *,,n.r, irr*.." ence in fL"E a*

ateJy carrcd tr,"-fori.". A p"r;;;';;;;;;; :iq9a,*, .lA#;J;I.*#:jitestified that he ,":"i,.9..n'.",t;; ;;.;;;;n ar;.Ipp. :,, * .r;.^ 623 (tss6)) rhere,describing the autom-obile anrl ,h;r;l; Iinglisrr,s .o,rr;.,ion r.vas aflrrreri on thcthereafter, salv a car ritt;rs J,"i .r:;;;;,1 basis of rina;ng rior.n goo<Js in irs aLuto-tion and stopped it. rr" rnrnir*o'i.*i.r,11-, rnorrirc o, the,ro.ning folrowing the theft.ii,i ili 1,"'J.To,#'o:1:,]il1 ,'j*H*: 'rhis court hercr i,,grish to be in ,,con-

ttnder arrcst. for burgrar,

",r,r *.r,,*r 1",..-

structive posscssion" of the reccntry stolen

ny.' Thus, in Phiffer, we hacl three cr"

goods which was thcre agairr sufficient towltnesscs olrscrving thc crirnc ,. n."*r"J,

corroborate thc tcstirrrony of ;tn

"aaon.,-seeing thrce nren in thn ..^"^""-^;'::-:'"' plicc.

tcrevisiorr scts i, ,nin: lrorr:s. of pracing

lu" "r,: ho,r o,,'";;;.;:,,llix:'li ,r]T:: rr.t t-aza.son u. state,3s Ara.App. 3zz, BZpects almost immJately after the crinre. so'zd-8i7ltB5)-th[ cou.t stated that theunexflained-piisscssion of ,...ntty .ioi.r,

. rn.whitc, thcre was likervise an apprc_ floodt .o,r:lj1j,.,1jlSl!g from rvhich thc

l:l',o" inrrrrediately rolro*i";-;;';";;i:;. 1,,.1' ,,frIii..-liri Althotrgh that casearter an atrtomobilc chasc by ttre poli.c. il]]:".,].d larceny rathcr than t ,,yi,rg, ,.-Thc. dcfenclants u,crc in thc ",,;;;i,;;;:

ceivi,g, ctc., it rvas cited i, Ettglislt, snpra,

flvins been <lcscribed l-ry makc ;;J ;;;: rollhelllllorv;i?TioFosltio::'r'r-' :"v''.r

identificd as lrcirrg ;tt thc pl:rcc of ,f,. .ri,_trery tntnretli:rtely 1rri,r to tlrc rorrrrcry bcirrg "l),sscssi,tt is ,ot Iirrritr.rl t. :rctrrirl lrrarr-tlisc'vcr<'<1. - - -'-"v'J ,urrr*

tt;tl c.tttt'.1 ,r)()r'r or :Lrr'trt trrc pcrsor. rtrrrrrlcr orrt.,s porvct lrn<i dorniniorr the

^.[.91

It is important to notc that in bot'

thing is possessccl'

-That the

"pp.rr"ri

i:"0{il.i:i,,lft.;l, the e,,ide,ce of IlryI|l1T. ".:,'u:.,f;;ru';j *i

recentiy .tor.,,'g;o,r,-," ;": :il'::;Xil:f ,T:;iji:,1

his possession ancr contror or

140 Ala. 329 SOUTIIERN R'EPOR'TER" 2d SERIES

ln Booker u. Strrte, 151 Ala. 97, 44 So.

56 (1907), Chief Justice Tyson stated:

,fi'tt i, undoulrte<Ily true that, in order to

\ sustain a conviction for receiving stolen

,{ p.op..,y, the defendant must be shown

I to h"u. had a control ovcr the propcr-

I

Ltv.

See also'. McConncll a. State,48 Ala.App.

523, 266 So.2d 328, ccrt. denied, 289 Ala'

746,266 So.2d 334 (1972); Milamu. State,

240 A\a.314, 198 So.863 (1940).

In the recent case of. Crotpden and As-

heza t,. S,d/e, 55 Ala.App. 325, 315 So.2d

122, c.ert. dcnied, 294 Ala. 756, 315 So'2d

128 (1975), this Court held that a co-de-

fendant's mere presence in an autonrobile

with the defenclant recently after a burgla-

ry would not be sufficient evidence from

which the jury could infer that the co-de-

fendant committed or participated in the

crime of burglarl', grand larceny or receiv-

ing and concealing stolen property.

t7) In the instant casc, the appellant

was a passenger in Whisenant's arttonrobile

at the time of the arrest. Hc rvas not a

passenger immediately following discovery

of the break in or larceny, neither was hc

fleeing from the police' Pursuant to the

above authorities, his mere presence in the

automobile would not constitute construc-

tive possession of the stolen itenrs, since he

neither owned or operated the vehiclc.

In the absence of a showing that he

knew the guns to be in the car, knerv them

to be stolcn and exercised some control

over them, his presence in thc car, stand-

ing alone, woulcl not be sufficient for a

conviction. While such circumstances may

possibly tend to corroborate the statement

which Whisenant gave the police, it is to-

tally insrrfficit:trt ttl strpport a cortviction irl

rrn<l oI itsclf' 'l'hc altllcll;rrll's ttttttiott to

exclrtdc tlrc State's cvitlcltcc sltortld hltvc

been granted.

Reversed and rcmanded.

All the Judges concur.

ln re Davld Mlchaol ISBELL

v.

STATE.

Ex parte STATE of Alabama ex rel'

ATTOBNEY GENEFAL.

sc 1760.

Strprcme Cour0 of Alabanla.

APril 2, 1976.

Certiorari to the Court of Criminal Ap-

peals.

William J. Baxley, Atty. Gen., and Ellis

D. Hanan, Asst. Atty. Gen., for the State

petitioner.

No appearance for resPondent.

FAULKNER, Justice.

Petition of the State by its Atty' Gen. for

Certiorari to the Court of Criminal Appeals

to review and revise the judgment and de-

cision of that Court in IsbelL a. State, 57

Ala.APP.

-,

329 So.2d 133.

WRIT DENIE,D.

HEFLIN, C. J., and BLOODWORTH,

ALI{ON and EMBRY, JJ., concur.

2

I

t

c

l;.

la

2.

nl

ir

dr

Eugeno Blzell PENDLETON, Jr.

Y.

STATE.

6 Dlv. 881. P'

Court of Crirninal Apfrcals of Alabama-

Oct. 1' 1975.

tlolrcttrltrx I)r'ttlt'rl (k:t. !ti' 1075'

Defendant was convicted in the Cir-

cuit Court,. Jefferson County, Wallace

Gibson, J., of murder in the second degree,

and he appealecl. The Court of Criminal

o

B

di

rc