Hammon v. Barry Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

November 20, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hammon v. Barry Brief Amici Curiae, 1985. ba12da4c-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8dd9e8df-b19e-4d80-8cf2-84db917f684b/hammon-v-barry-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

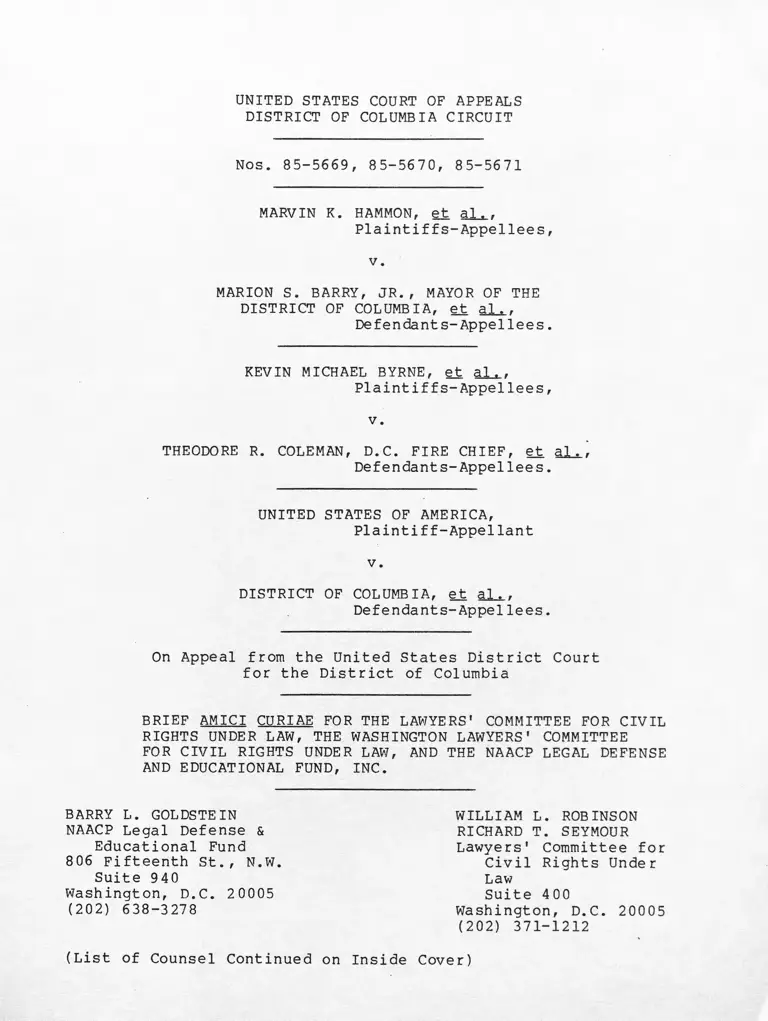

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

Nos. 85-5669, 85-5670, 85-5671

MARVIN K. HAMMON, et al ■ .

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

MARION S. BARRY, JR., MAYOR OF THE

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, et al. .

Defendant s-Appellees.

KEVIN MICHAEL BYRNE, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

THEODORE R. COLEMAN, D.C. FIRE CHIEF, et al.,

Defendants-Appel1ees.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant

v.

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, et al..

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE FOR THE LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW, THE WASHINGTON LAWYERS' COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW, AND THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund

806 Fifteenth St., N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 638-3278

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

RICHARD T. SEYMOUR

Lawyers' Committee for

Civil Rights Under

Law

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

(List of Counsel Continued on Inside Cover)

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational

Fund

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

RODERICK V.O. BOGGS

Washington Lawyers'

Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

1400 'Eye' St., N.W.

Suite 450

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-5900

Dated: November 20, 1985

INTEREST OF AMICI

Table of Contents

Page

1

COUNTER-■STATEMENT OF THE FACTS 3

A. Introduct ion 3

B. Evidence of Past Discrimination 3

1. Adverse Impact of the 1980

and 1984 Hiring Tests 4

a) Delay in Hire 4

b) The 1980 Hiring Test 6

c) The 1984 Hiring Test 9

d) The Stipulations 11

e) The District Court's Findings 13

2. The Tests' Lack of Validity 14

a) The Hearing Examiner's Findings 14

b) The Stipulations

c) The District Court's Findings

C. The Affirmative Action Plan

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

ARGUMENT

17

18

18

21

25

A. An Affirmative Action Plan Designed To Ensure

That Illegal Discrimination Does Not Occur Is

an Appropriate and Well-Accepted Use of

Affirmative Action 25

1. The Limited Purpose and Effect of the

Fire Department's Hiring Affirmative

Action Plan 25

2. The Use of Affirmative Action To

Neutralize the Discriminatory

Consequences of an Invalid Selection

Procedure Has Been Approved by the Courts 26

Page

3. The Use of Affirmative Action to

Neutralize the Discriminatory

Consequences of an Invalid Selection

Procedure is Authorized

by the EEOC's Affirmative Action

Guidelines 34

4. The Use of Affirmative Action to

Neutralize the Discriminatory

Consequences of an Invalid Selection

Procedure is Authorized by the Justice

Department's Own Regulations 37

B. The Sweeping Assertions of the Justice Department

and Local 36 that Affirmative Action Is Illegal

and Unconstitutional Are Without Merit 40

CONCLUSION 48

APPENDICES

Relevant Parts of the Uniform Guidelines

on Employee Selection Procedures,

28 C.F.R. Part 50.14 (1985) la

EEOC Guidelines on Affirmative Action,

29 C.F.R. Part 1608 (1985) 10a

Relevant Parts of Adoption of Questions

and Answers to Clarify and Provide a

Common Interpretation of the Uniform

Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures 17a

Table of Authorities

Pages

1• Cases

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975)................................. 30

Anderson v. City of Bessemer

53 U.S.L.W. 4314 (1985) .............................. 47

Association Against Discrimination v. City

of Bridgeport, 594 F.2d 306 (2d Cir. 1979)...... . 31

Berkman v. City of New York, 536 F.Supp. 177

(S.D.N.Y. 1982), aff'd, 705 F.2d 584 (2nd Cir.

1983)..................... .......................... 30

- i i -

Pages

Berkman v. City of New York, 705 F.2d 584

(2d Cir. 1983)................................... . .. 33, 34

Britton v. South Bend Community School corpora

tion, Slip Opinion, No. 84-2841 (7th Cir.,

Oct. 21, 1985)......................... ......... . .

Bushey v. N.Y. State Civil Service Comm'n

733 F.2d 220 (2d Cir. 1984), cert, denied,

53 U.S.L.W. 3477 (1985)....... ....................

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Local 542,

Operating Enqineers, F.2nd

38 FEP Cases 673 (3rd Cir. 1985)................. . . 44

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Rizzo, 13 FEP Cases

1475 (E.D.Pa. 1975)...... ........................ . . 33

Devereaux v. Geary, 596 F.Supp. 1481 (D.Mass. 1984).. . 46

Devereaux v. Geary, 765 F.2d 268 (1st Cir. 2985)___ _ . 44

Diaz v. American Telephone & Telegraph,

752 F.2d 1356 (9th Cir. 1985)..................... . 45

EEOC v. Local 638, Sheet Metal Workers,753 F.2d

1172 (2d Cir. 1985), cert, granted, No. 84-1656,

54 U.S.L.W. 3223 (Oct. 7, 1985)................. . . 44

Ensley Branch, NAACP v. Seibels, 14 FEP Cases 670

(N.D. Ala. 1977), aff’d, 616 F.2d 812 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied, 449 U.S. 1061 (1980)................ . 33

Ensley Branch, NAACP v. Seibels, 616 F.2d 812

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 449 U.S. 1061 (1980).... . 30

Firefighters Institute for Racial Equality v.

City of St. Louis, 588 F.2d 235 (8th Cir. 1978),

cert, denied, 443 U.S. 904 (1979)................. . 33

Firefighters Institute for Racial Equality v.

City of St. Louis, 616 F.2d 350 (8th Cir. 1980),

cert, denied, 452 U.S. 938 (1981)................. . 30

Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts,

104 S.Ct. 2576 (1984)..................... . 44, 45

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980).... . 42

Grann v. City of Madison, 738 F.2d 786

(7th Cir. 1984).....

- iii -

. 45

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)......... 25

Guardians Ass'n of New York City v. Civil

Service Comm'n, 630 F.2d 79 (2d Cir. 1980),

aff'd on other grounds, 463 U.S. 582 (1983)....... 32

Kirkland v. New York State Dept, of correctional

Services, 628 F.2d 796 (2d Cir. 1980),

cert, denied, 450 U.S. 980 (1981).................. 26 , 31, 34

Kirkland v. N.Y. State Dept, of Correctional

Services, 711 F.2d 1117 (2d Cir. 1983)............. 31

Kromnick v. School District of Philadelphia,

739 F.2d 894 (2d Cir. 1984), cert, denied,

53 U.S.L.W. 7483 (1985)............................. 45

Local 53, Asbestos Workers v. Vogler,

407 F . 2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969)................... . 33

Luevano v. Campbell, 93 F.R.D. 68 (D.D.C. 1981)...... 27

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971)............... 42

NAACP v. Allen, 340 F.Supp. 703 (M.D. Ala. 1972),

aff'd, 493 F. 2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974)................ 27

North Carolina Bd. of Education v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43 (1971).................................. 42

Oburn v. Shapp, 393 F.Supp. 561 (E.D.Pa. 1975),

aff'd, 521 F . 2d 142 (3d Cir. 1975)................. 33, 34

Paradise v. Prescott, 767 F.2d 1514 (5th Cir.1985).... .............. ............................. 45

Pullman-Standard Co. v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982)___ 47

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978)................................ 42, 45,

46 *

Reynolds v. Sheet Metal Workers Local 102,

498 F.Supp. 952 (D.D.C. 1980), affd,

226 U.S. App. D.C. 242, 702 F.2d 221 (1981)..... . 30

Segar v. Smith, 238 U.S. App. D.C. 103,

738 F.2d 1249 (1984), cert, denied,

53 U.S.L.W. 3824 (1985).............................25f 41

Pages

iv

Pages

Sims v. Local 65, Sheet Metal Workers,

353 F.Supp. 22 (N.D. Ohio 1972), aff'd in

pertinent part, 489 F.2d 1023 (6th Cir. 1973)..... 31

Stanley Works v. Federal Trade Comm'n,

469 F. 2d 498 (2nd Cir. 1972)........................ 23

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971).................................... 42

Turner v. Orr, 759 F.2d 817 (11th Cir. 1985).......... 45

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh

v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977)................... . 42

United States v. City of Buffalo, 609 F.Supp.

1252 (W.D.N.Y. 1985), appeal pending............ 25

United States v. City of Chicago, 631 F.2d 469

(7th Cir., 1980).... ........ ..................... . 30

United States v. City of Chicago, 663 F.2d 1354

(7th Cir. 1981)(en banc)............................ 28, 33

United States v. Nassau County, C.A. Nos.

77-C-1881 and 77-C-1869 (W.D.N.Y., March 1982).___ 28

United States v. New York, 21 FEP Cases 1286

(N.D.N. Y. 1979)........ . .......... ................. 27

Van Aken v. Young, 750 F.2d 43 (6th Cir. 1984)....... 45

Vanguardsv. City of Cleveland, 753 F.2d 479

(6th Cir. 1985), cert, granted, No. 84-1999,

54 U.S.L.W. 3223 (Oct. 7, 1985).................... 45

Vulcan Society of Westchester County, Inc.

v. Fire Dept, of City of White Plains,

505 F.Supp. 955 (S.D.N.Y. 1981)........ ........... 30 , 31

Williams v. City of New Orleans,

729 F. 2d 1554 (5th Cir. 1984) (en banc)............. 41

Wygant v. Jackson Bd. of Education, 746 F.2d 1152

(6th Cir. 1984), cert, granted, No. 84-1340,

53 U.S.L.W. 3739 (April 15, 1985)............... 45

v

2. Statutes, Regulations, and Other Authorities

Pages

Title ViI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

(as amended), 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq............passim

P.L.. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103 (Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972)...... ..................... 36

Reorganization Plan Number 1 of 1978,

43 Fed,Reg. 19807.................................... 35, 36

Executive Order 11246 (September 24, 1965,

last amended by Executive Order 12086,

effective October 8 , 1978).......................... 43

Executive Order 12067 (June 30, 1978)................. 38

Adoption of Questions and Answers to Clarify and

Provide a Common Interpretation of the Uniform

Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures,

43 Fed.Reg. 11996 (1979)............................ 38

Affirmative Action Guidelines, Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission, 29 CFR Part 1608............ 35, 36 ,

10a

Policy Statement on Affirmative Action Programs

for State and Local Government Agencies,

41 Fed.Reg. 38,814 (Sept. 13 , 1976)................. 37 , 7a

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures, 28 CFR Part 50 .14........................ 29 , 37 ,

la

- vi

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

Nos. 85-5669, 85-5670, 85-5671

MARVIN K. HAMMON, et al . .

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

MARION S. BARRY, JR., MAYOR OF THE

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, et al . ,

Defendants-Appellees.

KEVIN MICHAEL BYRNE, et al..

Piainti ffs-Appellees,

v.

THEODORE R. COLEMAN, D.C. FIRE CHIEF, et aJL*.,

Defendants-Appellees.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant

v.

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, et al . .

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE FOR THE LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW, THE WASHINGTON LAWYERS' COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW, AND THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

INTEREST OF AMICI

The Lawyers' Committee is a nationwide civil rights

organization, with local offices in Washington, Philadelphia,

Boston, Chicago, Jackson, Denver, Los Angeles, and San Fran

cisco. It was formed by leaders of the American Bar in 1963,

at the request of President Kennedy, to provide legal represen

tation to blacks who were being deprived of their civil rights.

Over the years, the national office of the Lawyers' Committee and

its local offices have represented the interests of blacks,

Hispanics, and women in many hundreds of class actions in the

fields of employment discrimination, voting rights, equalization

of municipal services, and school desegregation. Well over a

thousand members of the private bar, including former Attorneys

General, former presidents of the American Bar Association^ and

other leading lawyers, have assisted it in these efforts.

The Washington Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law has represented the plaintiffs in scores of employment

discrimination class actions in the Washington area.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., is

a nonprofit corporation whose principal purpose is to secure the

civil and constitutional rights of minorities through litigation

and education. For more than 40 years, its attorneys have

represented plaintiffs in thousands of civil rights cases,

including many significant cases before the Supreme Court and

this Court.

Many of the employment discrimination cases brought by

amici are against employers which could have cured their problems

without judicial intervention if they had developed and implemen

ted reasonable affirmative action plans such as the plan at issue

in the case at bar. Employers will not develop or implement such

plans if the plans will then be subject to the type of attack

- 2 -

made by the Attorney General in the case at bar. Amici and their

clients have a direct interest in securing a rule of law encour

aging employers to address and resolve their own problems, so

that the filing of enforcement lawsuits will be unnecessary.

Amici were granted leave to appear as amici below, and

at the invitation of the district court participated in the

briefing and argument on many of the key issues below.

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

A. Introduction

Amici offer this counter-statement of the facts because

the descriptions of the record contained in the briefs of the

United States and of Local 36 are both inaccurate and highly

misleading. In offering this counter-statement, we have in

several places set out the contrasting descriptions of the record

offered by the plaintiff and its amicus.

B • Evidence of Past Discrimination

In October 1980, Jon F. Sheffield and Theodore

0. Holmes filed administrative complaints of discrimination by

the District of Columbia Fire Department in hiring, promotions,

and other aspects of employment. The complaints were filed with

the District of Columbia Office of Human Rights, and alleged

violations of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and

District of Columbia laws.-*- The 50 days of evidentiary hearings 1

1 Hearing Examiner's Report [hereinafter, "Report"] dated

September 20, 1983 at 1-2, Defendants' Appendix [hereinafter,

"D.App."] at 26-27. The Report is Exhibit 12 to the March

14, 1985 Statement of Stipulated Material Facts [hereinafter,

"Stipulation"]. Stipulation 1f 49, D.App. 21.

3

on these charges began on December 10, 1981 and ended on April 6 ,

1982.2

Much of the record bearing on the question of past

hiring discrimination by the District of Columbia Fire Department

stems from the findings on hiring issues of Patrick E. Kelly, a

Hearing Examiner for the District of Columbia's Office of Human

Rights. Neither the United States nor Local 36 challenged

the accuracy of any of the Hearing Examiner's findings on the

hiring issues when the case was before the district court,

although they attempt to make such challenges for the first time

in this Court.

1• Adverse Impact of the 1980

and 1984 Hiring Tests

a) Delay in Hire

The history of the hiring tests for the D.C. Fire

Department was set forth in Finding 29 of the Hearing Examiner's

Report [hereinafter, "Report"] at 21-22, D.App. 46-47:

29. Prior to January 1, 1980, the responsi

bility for the testing of District of Columbia

Firefighters was vested with the Office of

Personnel Management. The Office of Personnel

Management utilized Test 21 which is essentially a

multiple choice test, and applicants were placed

on the register in rank order according to their

score. This meant that Whites who tended to score

well as a group were constantly being inserted on

the registers over Blacks, who tended to cluster

near the passing score of 70. (Tr. vol. 28, Pages

55-57). At the request of the Respondent (DCFD)

the process was changed in the early 1970['s], and

subsequently every register was exhausted before a

new examination could be administered. (Ibid).

2 Report at 12, D.App. 37 (noting the obvious typographic

error in the ending date); Stipulation 1f 47, D.App. 47.

4

The Respondent (DCFD) contends that this change

was sought as a means of improving its minority

work force.

Neither the United States nor Local 36 contested this finding

below.

Because of the policy of exhausting one register before

another register is certified, there can be adverse impact in

passing rates, but if the policy is actually followed and there

is no falloff in applicants' interest because of long delays in

hire, there would not usually be any adverse impact in the hire

rates of those who passed the test. If 50% of the persons

passing the test were black, barring unforeseen complications 50%

of the hires will be black. In these circumstances, adverse

impact as to the persons passing the test occurs in terms of how

long applicants are forced to wait before they are hired.^ The

The^ United States and Local 36 argue that there has

been no prior hiring discrimination by the Fire Department. The U.S. brief states at 35:

... the Department since 1981 has been hiring blacks

at a rate that equals or exceeds their representation

in the District labor force and any effects of the

allegedly unlawful 1981 [sic] examination have been

fully cured by the 1983 OHR Order and 1984 consent decree __ .

(Emphasis supplied). Local 36 states in its brief at 4:

Rather, on this record ... there has been no discrim

ination in hiring during the 22-year period for which

the record contains data.

(Emphasis in original). However, neither brief discusses

or considers the plight of black applicants forced to wait years

longer than white applicants before they can be reached for hire

on the rank-ordered list. Nor does either the United States or

its amicus choose to discuss the significant adverse impact in

hiring rates from the 1980 examination, or the significant

- 5 -

68. When a cutoff score is used at chance

level and hiring continues over a period of time,

the major concern is the loss and harm suffered by

those hired later, or not hired at all, compare[d]

to the benefit received by those hired first. The

difference in benefit is considerable and under

the general principle that Title VII says you

shall not discriminate in conditions of employ

ment, that is certainly true in these cases where

a firefighter['s ] eligibility to sit for promo

tional examinations is regulated by his or her

date of entry of employment with D.C.F.D. . . .

b) The 1980 Hiring Test

Hearing Examiner directly addressed this situation:4

On

administered

["FST"]. The

of the 1,362

screening, al

November 22, 1980, the D.C. Office of Personnel

the 1980 Entry Level Firefighters Selection Test

initial screening for the 1980 test disqualified 388

applicants. Of those who survived the initial

1 but 15 passed the test. Blacks were 75.11% of the

original 1,362 applicants, and 74.35% of the 959 applicants who

passed the test.5 The applicants passing the test were ranked in

the order of their scores, and hires were made in accordance with

rank order. The first twenty-three vacancies were filled on April

27, 1981; only two blacks were among this group of hires.®

Paragraph 9 of the Stipulation, D.App. 9, sets forth * 4 * *

adverse impact in passing rates from the 1984 examination. See

infra at 7-10.

4 Report at 31, D.App. 56.

® Findings 4, 5 and 26 at pp. 14 and 20 of the Report,

D.App. 39 , 45; Stipulation 1Mf 18-19, D.App. 11.

® Findings 7, 9 at p. 15 of the Report, D.App. 40.

- 6 -

the hiring statistics for the 1980 examination:7 8 *

Year Total Hires White Hires Black Hires % Black

1981 23 21 2 8.7%

1982 114 34 77 67.5%

1983 77 15 62 80.5%

1984 14 3 11 78.6%

At the oral argument in the district court, amici pointed out

that 29% of the white hires were hired in 1981, within roughly a

year after they took the test. Only 1% of the black hires

were hired within a year after they took the test. The appli

cants hired in 1983 and 1984 were forced to wait two or three

years before they were hired. Only 25% of the white hires had to

wait this long, but 48% of the black hires had to endure this

wait before they were hired.®

Moreover, only 228 applicants were hired from the

November 1980 examination, although 959 applicants passed. 73

whites were hired, constituting 35.6% of the 205 whites who

passed the test and 35.3% of the 207 whites who took the test.

152 blacks were hired, constituting 21.3% of the 713 blacks who

passed the test and 21.0% of the 724 black applicants who took

the test.® The racial disparity in hiring rates was statisti

7 The three Hispanic hires in 1982 are not shown here,

although their hires are included in the total and reflected in

the percentages shown.

8 March 23, 1985 Hearing Tr. at 103-04.

Q The racial breakdown of test-takers is set forth in

Stipulation if 19, D.App. 11. The racial breakdown of test-

passers is set forth at Finding 5 of the Report, D.App. 39.

- 7 -

cally significant; the difference between the expected rate of

hire and the actual rate of hire is 2.67 standard deviations,

corresponding to a finding of statistical significance at less

than the .008 level (less than eight chances in a thousand of

this racial disparity, or a larger racial disparity, occurring by

chance). Amici presented the standard-deviation analysis to the

Court below, were asked to set forth the calculations in writing,

and did so.-10 11

The developer of the 1980 FST "admits that if selec

tions were made from the top scoring applicants it could be

expected that the FST would show adverse impact against Blacks

(Respondents Exhibit M, Page Vii; Pages 57-61).1,11 The District

of Columbia Office of Personnel "was aware of the possible

adverse impact that would be caused if the FST was used oper

ationally, but decided to use the test operationally as a rank

ordering selection procedure. (Tr. Vol. XIV, Page 116)."12 The

District of Columbia arranged for the Personnel Decisions

Research Institute to review the validation study for the test,

and the Institute reported that, if the test were used in ranking

applicants, "it would increase the adverse impact." The Hearing

March 23, 1985 Hearing Tr. at 101, 103. The calculations

were set forth in the Affidavit of Richard T. Seymour, attached

to amicj|s March 25, 1985 Submission of Materials Pursuant to the

Instruction of the Court. The equivalence figure for 2.67

standard deviations was provided to amici by a statistician using

standard reference works.

11 Finding 32 of the Report, D.App. 48.

12 Finding 34 of the Report, D.App. 49.

- 8 -

Examiner continued:13

Therefore it can be concluded that Respondent

(DCOP) was specifically aware of the predicted

adverse impact of the FST as early as February 5,

1981.

The District of Columbia's Director of Personnel had set up a

special task force in the D.C. Office of Personnel, and was

informed in June 1981 that the 1980 FST had adverse impact

against blacks.1 ̂ The Chief of the Recruitment and Examination

Division of the Office of Personnel admitted in testimony that

"the manner in which the FST was used resulted in an adverse

impact on protected groups. (Ibid; Vol. 16, Page 18). "15

c) The 1984 Hiring Test

The parties stipulated below that:1®

16. Components of the 1984 test were substan

tially the same as the corresponding compenents of

the 1980 test; but one component, following oral

directions, was revised and substantially

modified.

In addition to the likelihood that two substantially

similar tests will have similar degrees of adverse impact against

blacks, the parties also stipulated to racially disparate passing

rates on the 1984 test:17

13 Finding 36, D. App. 49.

14 Finding 72, D. App. 56-57.

15 Finding 75, D. App. 57.

16 Stipulation,, E>. App . 11.

17 Stipulation 1f 24, D.App.

- 9 -

Race Test-Take rs Test-Passers Percent Who Passed

White 492 486

Black 1,050 830

These differences are also statistically significant; the

difference between the expected number of blacks passing the test

and the actual number is 3.6 standard deviations. This is

statistically significant at less than the .0004 level, meaning

that there are less than four chances in ten thousand that this

racial disparity, or a larger racial disparity, could have

occurred by chance.

In addition, the parties stipulated that,, although 79%

of the applicants passing the 1984 test were black, blacks

constituted only 12% of the first 100 persons on a rank-ordered

certificate, only 26% of the second 100 persons on such a

certificate, only 37% of the third 100 persons on a rank-ordered 18

98.8%

79.0%

18 Calculation of counsel, performed in the same manner

which is set forth in the Affidavit of Richard T. Seymour

submitted to the district court on March 25, 1985. The figures are:

Percent of Test-Takers Who Were Black: 64.6%

Percent of Test-Takers Who Were Not Black: 35.4%

Number of Test-Passers: 1,384

Expected Number of Blacks Passing the

Test (.644 times 1,384) 894

Actual Number of Blacks Passing the Test 830

Observed Difference Between Expected and

Actual Numbers (Shortfall) 64

Standard Deviation (square root of the

product of .644 and .354 and 1,384) 17.8

Number of Standard Deviations Between

Expected and Actual Values 3.6

The equivalence figure in text was obtained by counsel from a

statistician who consulted standard reference texts.

- 10

certificate, and only 41% of the fourth 100 persons on a rank-

ordered certificate.19 Blacks would constitute only 25% of the

first 300 names on a rank-ordered certificate, and if the 228

hires from the 1980 list are a guide, most hires from the 1984

list are likely to be drawn from the top 300 names.20 This

result is closely similar to the results from the 1980 test, in

which blacks constituted 20.8% of the first 300 names on the

list.21

d) The Stipulations

Regardless of the positions being taken in this Court

by the United States and by Local 36, there can be no reasonable

question that all parties below-- expressly including appellant

and its amicus---stipulated to the adverse impact of both the

1980 and 1984 tests:22

17. Both the 1980 test and the 1984 test had

an adverse impact upon Black applicants as more

fully described below.

* * *

20. The hearing examiner's finding of

adverse impact [as to the 1980 test] is based upon

Stipulation If If 25, 27, D.App. 12-14.

2 0 It is not possible to predict with certainty how far down

the list the Fire Department will have to go in meeting its need

for new hires. Some applicants may no longer be available by the

time they are reached, particularly if they are not reached until

years after they took the test. Other applicants may still be

available, but may not be able to meet the medical and physical

requirements of the Fire Department. Their rejection then

requires the Fire Department to continue down the list.

21 Stipulation 1f 21, D.App. 12.

22 Stipulation, D.App. 11, 13, 15.

- 1 1

the rank order use of the examination, because

such use resulted in a substantially different

rate of selection of Black and White applicants.

* * *

26. The basis of establishing the pass point

[for the 1984 test] was to eliminate the adverse

impact of the examination and to meet the 80% rule

of thumb for determining adverse impact discussed

in the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures.

* * *

30. The AAP requires the use of multiple

certificates to select firefighters and is

designed solely to eliminate the racial and sexual

disparity which would exist if the examination

results were used in rank order.

e) The District Court's Findings

The district court recited the findings of the hearing

examiner as to the adverse impact of the 1980 test, App. 36-37,

and in reliance on the above-described record and stipulations

stated:

None of the parties herein dispute that for

many years the District of Columbia Fire Depart

ment discriminated against blacks.

App. 8 . The court then addressed the 1984 hiring test, and

stated:

Like the 1980 test which Hearing Examiner

Kelly found not to be valid or job-related, the

1984 entry level examination had an adverse impact

on blacks if selections were made on the basis of

rank order. Indeed, the 1984 test was substan

tially the same as the 1980 test. . . .

The adverse impact of the 1984 test becomes

apparent if selections were to be made on the

basis of rank order. ...

Because rank order use results in this

adverse racial impact, the AAP mandates a proce

12

dure for proportional appointment to the Depart

ment of test passers based on race, sex, and

national origin. These procedures are designed

solely to eliminate the racial, sexual, and ethnic

disparity which would exist if the candidates were

selected in rank order of examination results.

App. 44-45.

The district court expressly found that the applicant-

flow data for the 1980 and 1984 examinations were the most

approrpiate measure of the availability of blacks in the labor

market. App. 53. The district court rejected the D.C. govern

ment's contention that the availability of blacks should be

measured by labor market statistics for the District of Columbia,

and rejected Local 36's arguments in favor of using unweighted

labor force data from the entire Washington, D.C. Standard

Metropolitan Statistical Area. App. 51-53.

Local 36 urges this Court to reject the district

court's finding, on the wholly speculative theory that a recruit

ing effort undertaken in 1980 and/or enactment in 1980 of a

requirement that successful applicants move into the District

within 180 days after hire, resulted in a large increase in

applications filed by blacks. Local 36 brief at 13-14. The union

did not produce an iota of proof in the district court to support

any of the legs on which its arguments before this Court depend:

■-- that there was any meaningful difference

between the recruiting efforts undertaken in

1980 and those undertaken earlier;

---that there was any recruiting effort in 1984

comparable to that in 1980;

- 13

---that there was any change in 1980 in the

proportion of applicants who were black, over

the proportion which had existed earlier; or

-- that there were any special factors whatso

ever artificially inflating the black

applicant flow in 1984 and making the 64.6%

black applicant-flow figure unreliable as an

indicator of what the applicant flow would

have been in prior years.

Such matters are usually required to be proven, rather than

surmised. In any event, Local 36 has raised this contention

solely to help make its point that there is in its view no

adequate basis for the district court to have concluded that

there was substantial underrepresentation of blacks in the ranks

of the D.C. Fire Department over the past decades. Local 36 has

raised no express claim that any speculative increase in the

percentage of applicants who were black in 1980 and 1984 produced

a disproportionately large number of unqualified black appli

cants, so as to evade the thrust of the adverse-impact evidence,

stipulations, and findings as to the 1980 and 1984 hiring tests.

2. The Tests' Lack of Validity

a) The Hearing Examiner's Findings

The hearing examiner heard expert testimony from the

U.S. Office of Personnel Management, which developed the test,

and from Dr. Richard S. Barrett, who was retained by the District

of Columbia's Office of Corporation Counsel to conduct the second

- 14 -

independent review of OPM's validation study. As had the first

independent reviewer, Dr. Barrett found the validation study

inadequate. J

The hearing examiner found that the validation study

for the 1980 test was dependent on the adequacy of the job

analysis performed by OPM,* 24 and then found that the job analysis

was "insufficient under the Uniform Guidelines."25 * 27 28 Although OPM

had agreed that the physical activities of the job of Firefighter

were the most important aspects of the jobs, the 1980 test was

not designed to test physical ability. Although OPM had agreed

that skill in communications was the second most important aspect

of the job, and that cognitive abilities were only the third most

important aspect of the job,2® OPM's test was simply a test of

"general cognitive abilities".22.

The hearing examiner recited one of the basic ground

rules in test validation:2®

40. A test is not of any value to an

employer, nor valid under the [g]uidelines, if it

cannot predict the actual job performance [t]hat

it was designed to do; or if its predictions are

not based upon criterion measures that measure a

substantial number of critical work behaviors for

the job being tested for.

22 Findings 36-77 of the Report, D.App. 49-58.

24 Finding 33 of the Report, D.App. 48.

25 Finding 45, D.App. 51.

Findings 46 and 48 of the Report, D.App. 51-52.

27 Stipulation 1f 15, D.App. 10.

28 Report, D.App. 50.

15

Instead of developing an actual measure of job performance to

fulfill this important task, OPM used paper-and-penci1 tests for

most of its measures of job "performance". The hearing examiner

found:^9

50. No measure of actual job performance was

included in the content measures for the FST.

(Intervenor Exhibit 7, p. 2).

51. All of the criterion measures of the FST

were based on performance in training and all but

one of them are based on cognitive test[s].

(Intervenor exhibit 7, Page 2).

The hearing examiner explained the significance of this

problem:* 30 31

47. The work of a firefighter (Task) is

essentially physical and when performance is

confounded by reactions to danger, heat, physical

and emotional stress, correlations with cognitive

measures are inconvincing as demonstrations of job

relatedness. (Intervenors Exhibit 7, Page 5).

* * *

55. The job of a Firefighter does not

involve filling out multiple choice test[s], but

putting out fires. The job consist[s] of doing

things not writing them down. It is a matter of

being tested for making a response in a way which

is not called for by the situation. (Ibid;

Tr. Vol.XXIV, Page 127).

The hearing examiner then found that the 1980 test

could not validly be used for rank-ordering applicants, because

there was no adequate showing that a higher-scoring applicant

would perform better on the job than a lower-scoring applicant.3-̂-

Report, D.App. 52.

30 Report, D.App. 51, 53.

31 Findings 63-66 of the Report, D.App. 54-55.

- 16 -

The hearing examiner's findings also relied upon

testimony from responsible personnel officials in the District of

Columbia Government. The special task force established by the

Director of the D.C. Office of personnel recommended that the

District of Columbia hire in a manner which eliminated the

adverse impact of the examination, and that the D.C. government

not attempt to defend the job relatedness of the test.22

The Chief of the Recruitment and Examination Division of the

D.C. Office of Personnel, Mr. Dressier, "specifically testified

in the hearing that the FST use of ranking could not be vali

dated."22 Mr. Dressier agreed with Dr. Barrett that the use of

training school grades as a measure of job performance, to

validate the hiring test, "should be suspect."24

b) The Stipulations

Three paragraphs of the Stipulation bear directly on

the validity of the 1980 and 1984 hiring tests:22

22. The District of Columbia accepted these

and other findings of the Hearing Examiner

concerning adverse impact and job relatedness [of

the 1980 test], and does not now contend that the

written examination either had no adverse impact

or is valid and job related.

* "k -k

28. The District of Columbia does not

contend that the pass point [for the 1984 hiring 32

32 Findings 72-73 of the Report, D.App. 56-57.

O'! Finding 74 of the Report, D.App. 57.

24 Finding 77, D.App. 57-58.

25 D.App. 12, 14-15.

- 17 -

test] was based on the needs of the job or was

otherwise linked to a measure of successful job

performance,

29. The District of Columbia has agreed to

validate the examination in accordance with the

May 23, 1984 consent decree in the Hammon case

but, to date, has not done so. In particular,

neither the District of Columbia nor any other

party to these consolidated cases has developed

validity evidence meeting the standards of the

psychological profession showing that those who

score higher on the test are more likely to

perform better on the job than those who score

lower.

c) The District Court's Findings

The district court described the hearing examiner's

findings that the 1980 hiring test was not valid or job-related,

App. 36, 44, and then found that the 1984 hiring test also had

not been shown to be valid:

The examination has not been validated, and there

is no evidence demonstrating that those who score

higher on the examination are more likely to

perform better on the job than those who score

lower on the test. (Joint Stipulation 11 29) .

This is consistent with the findings of Hearing

Examiner Kelly.

App. 44-45.

C. The Affirmative Action Plan

The January 3, 1985 affirmative action plan

[hereinafter, "AAP"] in question is 228 pages long. It analyzes

employment patterns for uniformed positions in the Fire Depart

ment, exhaustively analyzes the question of underutilization of

women and minorities in various ranks and jobs, describes special

problems in filling positions in various ranks, analyzes

deficiencies in what the Fire Department has done in the person

- 18 -

nel area, defines problem areas, and proposes solutions. It

recommends programs in recruitment, upward mobility, career

development, and the women's program. Most of the AAP is not

controversial.

The provision of the AAP at issue here is its system of

certificates of applicants for hire, each consisting of 100

names. Each certificate must include a group of applicants, 6 o%

of whom are black, 2.4% of whom are Hispanic, 35.1% of whom are

white, 2.6% of whom belong to other groups. 93% of the persons

certified on each certificate are to be male and 7% are to be

f e m a l e . S e l e c t i o n s are to be made in a manner which ensures

that each entering academy class be 60% black and 5% female.37

Each group is rank-ordered by a combination of test score and

veterans' preference points.38 The AAP expires in October 1986

by its own terms. App. 56.

The bulk of the AAP was developed, at least in part, to

satisfy the requirements of local legislation requiring

D.C. government agencies to analyze their own employment patterns

and develop AAP's. This appears from the face of the AAP itself,

and was also stated in Stipulation 1f 53, D.App. 21, which reads

in its entirety: "The AAP was intended to achieve compliance with

D. C. Law § 1-63." This does not mean that every provision of

the plan is based upon this legislation. Indeed, Stipulation 11

36 Stipulation 1f 32, D.App. 15.

37 Stipulation 1f 34, D.App. 17.

38 Stipulation 1f 31, D.App. 15.

- 19 -

54 states:29

54. The reasons for the AAP's adoption of the

short-term goals for Sergeants, Lieutenants and

Captains are stated in the AAP.

Local 36 argues that the hiring-certificate provisions

of the AAP were not designed to provide a remedy for past

discrimination. "The AAP at issue here has no such purpose."

Local 36 brief at 3-4. Instead, urges Local 36, the hiring-

certificate provisions were "adopted to comply with D.C. Law 1-

63". Id. This representation is unfounded. Local 36, and all

other parties below, expressly stipulated to the contrary:39 40

30. The AAP requires the use of multiple

certificates to select firefighters and is

designed solely to eliminate the racial and sexual

disparity which would exist if the examination

results were used in rank order.

(Emphasis supplied). Local 36 has not urged that its assent to

this stipulation was procured by fraud or duress, and has not

presented any other reason why it should be relieved of its

stipulation. The district court adopted this stipulation, as it

was entitled to do:

Because rank order use results in this

adverse racial impact, the AAP mandates a proce

dure for proportional appointment to the Depart

ment of test passers based on race. These

procedures are designed solely to eliminate the

racial, sexual, and ethnic disparity which would

exist if the candidates were selected in rank

order of examination results.

App. 45. Amici respectfully submit that the stipulation and its

39 D.App. 22.

40 D. App. 15.

- 20 -

adoption by the Court conclude the point.

There is no evidence of record to indicate what the

District of Columbia intends to do, with respect to Fire Depart

ment hiring, after October 1986.

SUMMARY OF ARCHMDNT

The hiring provisions of the Fire Department’s Affirma

tive Action Plan are limited in purpose and effect to the partial

neutralization of the racially discriminatory consequences of the

1984 test's passing rate and rank-ordered use of scores.

This purpose and effect are both constitutional and

lawful. They are expressly authorized by the Department of

Justice's own regulations, regulations which the Department has

chosen not to discuss either in the court below or in this

Court. Indeed, the Department of Justice has successfully

argued, in innumerable cases across the country, for the judicial

imposition of remedies which are indistinguishable from those

voluntarily adopted by the D.C. Fire Department in the case at

ba r.

The arguments of the Justice Department and its amicus,

that affirmative action is unlawful and/or unconstitutional,

result from a strained and implausible reading of caselaw and

legislative history. Every court of appeals in the country to

which such arguments have been put has rejected them.

While both the Justice Department and its amicus assert

factual propositions which cannot be supported in the record and

which contradict the necessary meaning and implications of their

- 21 -

own stipulations, neither has shown any reason to be relieved of

their stipulations, and neither has shown that the district

court's findings from an undisputed record were clearly er

roneous .

Put simply, the government of the United States has in

this lawsuit ignored the actual stipulated discrimination visited

upon black applicants for the D.C. Fire Department under the 1980

and 1984 tests, and has instead chosen to sue the D.C. Fire

Department for the temerity of following the Justice Department's

own regulations. Its challenge to the hiring provisions of the

AAP was properly denied below, and the grant of summary judgment

against the United States on the hiring issues should be affirmed

by this Court.

ARGUMENT

THE LIMITED PURPOSE AND EFFECT OF THE FIRE DEPARTMENT'S

HIRING AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PLAN---THE PARTIAL NEUTRALIZATION

OF THE RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY CONSEQUENCES OF THE RANK-

ORDERED HIRING PROCEDURES-- ARE LAWFUL AND CONSTITUTIONAL

A. An Affirmative Action Plan Designed To Ensure

That Illegal Discrimination Does Not Occur Is an

AppxQPriate_and Wei 1-Accepted Use of AffirmativeAction

1• The Limited Purpose and Effect of the Fire

Department's Hiring Affirmative Action Plan

The "procedures [of the hiring affirmative action plan]

are designed solely to eliminate the racial, sexual, and ethnic

disparity which would exist if the candidates were selected in

rank order of examination results." (Emphasis supplied).

Opinion, App. 45. The Court's finding was based upon a Stipula-

22 -

tion agreed to by all parties. Supra at 20.41 Moreover,

the plan before the Court is limited in duration: "The Fire

Department's plan will end on October 1, 1986 .... " Op. at

App. 56.

Current hiring is done pursuant to the 1984 hiring

test. The parties stipulated and the Court found that the 1984

hiring test disproportionately excludes black applicants. Supra

at 12. The Court emphasized the "apparent" discriminatory effect

Local 36 disregards its Stipulation and the Court's

express finding regarding the purpose and extent of the affirma

tive action plan. Local 36 invents a plan which was not pre

sented by the District of Columbia, or reviewed by the lower

court, and which is not before this Court. See supra at 18-21.

Judge Kaufman has written eloquently of the importance of

giving binding effect to stipulations:

No amount of statistical legerdemain justifies

disregarding the binding stipulation that controls

this case, ... . The parties conceded those

facts, the Examiner acted upon those facts, and

the Commission based its decision on those facts.

There may have been strategic litigation trade

offs that led to the adoption of the stipulation;

but we shall never know. Nor can we guess what

posture this case would have assumed had there

been no stipulation, what constellation of facts

might have emerged, but for the stipulation, is

wholly a matter of surmise, in which we may not

permit ourselves to engage. Having agreed on a

set of facts, the parties, and this Court, must

be bound by them; we are not free to pick and choose at will.

Stanley Works v. Federal Trade C.omm'n- Cir. 1972). 469 F .2d 498, 506 (2nd

It is difficult to tell which is more surprising in the

case at bar: the fact that Local 36 has chosen to disregard the

parts of the Stipulation it now does not like, or the fact that

it has done so in the pursuit of hiring issues which it did not

consider to be worth even taking a position on when the case was

before the district court. See Local 36 brief at 3.

23

of the 1984 hiring test by illustrating the racial consequences

which would result if the test were used as a rank-ordering

device to select 400 applicants. Op. at App. 45. If the test

were used without any affirmative action modification and if 400

persons were hired, then 116 black applicants would be hired,

comprising only 29% of the persons hired. App. 45.42 Since

blacks comprised 64.6% of the test-takers in 1984, Op. at

App. 44, a test without a disproportionate racial effect would

instead yield 258 black hires out of 400 persons hired. The

racially discriminatory consequences of the test would thus

result in the denial of jobs to 142 black applicants if there

were no modifications to reduce the degree of adverse impact.

"Because rank order use results in this adverse racial impact,

the AAP mandates a procedure for proportional appointment to the

Department of test passers based on race, sex and national

origin." Op. at App. 45.

The 1984 hiring test, which would have a harsh discrim

inatory consequence if used as a rank-ordering device, "has not

been validated, and there is no evidence demonstrating that those

who score higher on the examination are more likely to perform

better on the job than those who score lower on the test."

Op. at App. 45; see also the discussion supra at 18-22. "If an

employment practice which operates to exclude Negroes cannot be

42 Approximately 5% of the applicants were Hispanic or

unidentified by race or ethnic origin. Id.

If 300 applicants were hired by rank order, then only

25% of those hires would have been black. Supra at 11.

- 24

shown to be related to job performance, the practice is prohi

bited." Griggs v. Duke Power Co.. 401 U.S. 424, 431 (1971).

Where an employment practice, such as the Fire Department's 1984

hiring test, has a statistically significant racial disparity,

the employer cannot continue to hire or promote employees using

that practice unless the employer can prove that the practice is

a valid predictor of actual job performance.

It is clear that if the Fire Department used the 1984

test as a rank-order selection procedure then the Fire Department

would have violated Title VII. The black applicants denied hire

by the use of the practice would have been "identified victims"

entitled to "make whole" relief including monetary awards and a

right to preferential hire with constructive seniority.

The hiring affirmative action plan has the purpose and

effect of preventing a violation of Title VII and the creation of

a class of victims. In effect, the blacks who benefit from the

affirmative action plan are the individuals who would otherwise

likely be the actual victims of illegal use of the 1984 test.

The modification in the order in which those who passed the

test are selected for employment does not discriminate against

better-qualified whites because the test is not related to job

performance.^ jn the absence of a valid test, the original 43 44

43 See e.g,, Segar v. Smith. 738 F.2d 1249, 1282-83

(D.C.Cir. 1984), cert, denied. 53 U.S.L.W. 3824 (1985).

44 Cf. United States v. City of Buffalo. 609 F.Supp. 1252,

1254 (W.D.N.Y., 1985), appeal pending:

Since the selection procedures used by the

25

rankings have no more significance than numbers drawn by lot, and

the affirmative action plan merely eliminates the racial bias

built into the lottery. Seg. Kirkland v. New York State Dept, of

Correctional Services. 628 F.2d 796, 798 (2d Cir. 1980), ce rt.

denied. 450 U.S. 980 (1981).45

2. The Use of Affirmative Action To Neutralize the

Di.scxlm,,in.a.tQry , Consequences ,o,f an. Inyalld_..sejec

tion.Procgdure,,, Hag Bepn A.EgiLQ.y..e.d. by t h e Cour t s

The District of Columbia Fire Department, as have other

employers, found itself in a difficult situation: the Department

has a public safety need to hire firefighters but it has a

selection procedure which has a racially discriminatory effect

and which could not be shown to be job related as required by

Title VII. Moreover, the Fire Department, as with most public

employers, has a long tradition of following rank-ordered

selection procedures and the expectations of its personnel may be

built around the continuance of this tradition, regardless of the

merits of rank-ordering the results of a particular selection

City have not yet been shown to be accurate

predictors of job performance, it is, at this

juncture, somewhat presumptuous to say that an

injustice is done every time a candidate is

selected out of rank order.

4 5 In Kirkland, the Second Circuit approved the addition of

250 points to the test score of each minority in order to remove

the racially adverse impact caused by the test. Non-minority

test-takers challenged the procedure as "tantamount to a quota."

The claim was rejected because "the differential was necessary to

prevent future discrimination___ since [without the 250-point

adjustment the test] would not serve as a race-neutral predictor

of on-the-job performance." 628 F.2d at 798. The court further

observed that " [t]his program does not bump white candidates but

rather re-ranks their [estimated] predicted performance...." Id.

- 26

dev ice.

The development and implementation of a new selection

procedure which will be job-related is frequently a difficult,

costly, and time-consuming task. NAACP v. Allen. 340

F.supp. 703, 706 (M.D.Ala. 1972), aff'd. 493 F.2d 614 (5th

Cir. 1974) (Judge Johnson ordered the Alabama State Highway

Patrol to hire according to a race-conscious plan rather than

order new testing procedures because, in part, "it would in all

likelihood take several years to implement the selection pro

cedure--- "); see, e.g. , United States v. New York. 21 FEP Cases

1286, 1345 (N.D.N.Y. 1979) (The development of a job related

selection procedure for state police officers "will be no easy

task.... It should also be noted that operating under a state

civil service merit system [creates] greater obstacles [to]

performing this task than [face] private sector employers").

It is particularly surprising that the Justice Depart

ment has criticized the D.C. Fire Department for the failure to

devise in the past few years a job related hiring examination

rather than relying upon a procedure for the neutralization of

racially discriminatory consequences. U.S. Brief at 37-40. The

Justice Department negotiated and approved a 1981 consent decree

using a form of affirmative action comparable to the one used by

the Fire Department; the consent decree covered the selection

procedures for entry-level jobs for 118 professional and admini

strative occupations in the Federal service. Luevano v.

Campbell, 93 F.R.D. 68 (D.D.C. 1981). The decree provided that

- 27

the entry-level test, the PACE, would be phased out over a period

of three years and that, during the period when the PACE was

phased out and, in most instances, for a period of five years

after the entry of the Decree, the Federal agencies would be

obligated to use "all practicable efforts" to eliminate any

adverse impact on blacks or Hispanics caused by the entry-level

selection procedures. 93 F.R.D. at 79-80.

As a practical matter, it was necessary to incorporate

this neutralization of discriminatory consequences plan rather

than relying upon the development of a valid selection procedure:

To develop alternative examining procedures for

these PACE occupations which would be consistent

with the professional and legal requirements

imposed upon all Federal hiring examinations would

require a substantial period of time. Each

replacement examination must undergo a careful

technical development process which will require

extensive professional staff, time and expense.

93 F.R.D. at 79. Similarly, the Justice Department has argued

successfully for the use of race-conscious plans to remove the

adverse impact of selection procedures used by local govern

ments. See, e. g. , United States v, City of Chicago. 663 F.2d

1354, 1361-62 (7th Cir. 1981) (en banc);4® United States

A C "[W]e conclude that the 25% [promotion quota] figure

proposed in the joint motion is fully warranted by present

conditions. The 25% figure will in time establish parity at a

level that corresponds closely to the rate of minority hiring

currently produced by nondiscriminatory selection procedures.

Whether fortuitously or otherwise, the 25% figure also corrects

for the disparate impact of the 1979 sergeant examination:

minority applicants for promotion, who constitute approximately

25% of the applicants taking the 1979 sergeant examination, are

assured of receiving 25% of the promotions under the modified decree."

- 28

v. Nassau County. C.A. Nos. 77-C-1881 and 77-C-1869 (W.D.N.Y. ,

March 1982).47

Since the Fire Department uses the selection procedure

on a rank-order basis, it is even more difficult, expensive, and

time consuming for the District to establish that the selection

procedure as used is job related and lawful:

[I]f a user decides to use a selection procedure

on a ranking basis, and that method of use has a

greater adverse impact than use on an appropriate

pass/fail basis..., the user should have suf

ficient evidence of validity and utility to

support the use on a ranking basis, see sections

38, 14B(5) and (6), and 14C(8) and (9).

Section 5G, Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures,

28 CFR Section 50.14(5G).* 4® Courts have found the use of

47 paragraph 11 of the Consent Decree states:

... [X]n order to meet its needs for Police

Officers, Nassau County may make up to two hundred

(200) appointments from amongst those persons who

took the written examination (No. 66-681) adminis

tered by the County on October 17, 1977, it being

understood that any such interim appointments

shall be without adverse impact upon blacks,

Hispanics and female applicants ... .

An unsigned copy of the Consent Decree executed and filed in that

case has been lodged with the Clerk. The Justice Department

attorney in that case has assured the undersigned counsel that

the uinsigned copy is a true copy of the executed original,

except for the signatures.

4 8 The Guidelines were promulgated by the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission, the Civil Service Commission (now the

Office of Personnel Management), the Department of Labor, and the

Department of Justice. The purpose of the Guidelines is to

"incorporate a single set of principles which are designed to

assist employers ... to comply with requirements of Federal law

prohibiting employment practices which discriminate on grounds of

race.... They are designed to provide a framework for determin

ing the proper use of tests and other selection procedures."

Section IB. The Guidelines are codified in the Department of

29

arbitrary cut-off scores and unjustified rank-ordering illegal

even where the courts otherwise found the selection procedures

valid and lawful. See, e .g., United States v. City of Chicago,

631 F .2d 469, 476 (7th Cir. 1980); Firefighters Institute for

Racial Equality v. City of St. Louis. 616 F .2d 350, 357-60 (8th

Cir. 1980), ce rt. denied. 452 U.S. 938 (1981); Ensley Branch,

NAACP v. Seibels, 616 F.2d 812, 822 (5th Cir.), ce rt. denied, 449

U.S. 1061 (1980).

After a selection device has been determined invalid it

is often necessary, as here, for the employer to continue to hire

or promote. See e .a.. Berkman v, City of New York, 536 F.Supp.

177, 216 (S.D.N.Y. 1982) ("[T]o freeze all appointments [to the

Fire Department] may present a hazardous situation to the

citizens of the community"), aff1d. 705 F.2d 584 (2d Cir. 1983).

A variety of techniques, identical to or similar to the one used

by the Fire Department, have been devised by employers or the

courts to deal with this problem.^ * 49

Justice regulations at 28 CFR Part 50.14. The Supreme Court

determined that the predecessors to the Uniform Guidelines, the

EEOC Guidelines, were "entitled to great deference." Albemarl e

Paper Company v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 431 (1975); see, Reynolds

v. Sheet Metal Workers Local 102. 498 F.Supp. 952, 966

(D.D.C. 1980), aff'd, 702 F.2d 221 (D.C. Cir. 1981).

A copy of the relevant provisions of the Uniform Guide

lines is set forth at pp. la-9a below.

49 White applicants who score well on the invalid test, for

obvious reasons, may prefer a remedy which permits continued use

of these results even in a modified form. See e . cr. , Vulcan

Society of Westchester County, Inc, v. Fire Dept, of the City of

White Plains. 505 F.Supp. 955, 967 (S.D.N.Y. 1981). Under a

settlement, the City was permitted to use an invalidated written

test which had a racially discriminatory effect "only because the

30

Courts or employers have added points to the scores of

blacks in order to remove adverse impact, see e .a . . Ki rkland

V-«-.New York State Dept, of Correctional Services. 628 F.2d at

798; Bushey v. n .Y. State Civil Service Comm'n. 733 F.2d 220,

223, 227-29 (2d Cir. 1984), cert, denied. 53 U.S.L.W. 3477

(1985). In other instances the use of the selection procedure

has been modified in order to remove the rank-order process.

See, e.a., Kirkland v. N.Y. State Deot. of Correctional Services.

711 F.2d 1117, 1133-34 (2d Cir. 1983) (use of "zones" of scores

rather than rank-ordering); Vulcan Society of Westchester Countv.

Inc, v. Fire Dept, of City of White Plains. 505 F.Supp. at 959,

964 (settlement altered the use of a rank-order exam and made it

a general qualifying exam). Some courts or employers have used a

random selection method or indicated the propriety of selecting

in a random manner applicants who possessed basic qualifications.

e .u.> Association Against Discrimination v. City of Bridae-

P^rt, 594 F.2d 306, 313 n.19 (2d Cir. 1979) (adverse impact

"could be eliminated by random selection of appointees from the

group of passing candidates, rather than use of rankings"); Sims

v. Local 65. Sheet Metal Workers. 353 F.Supp. 22, 29 (N.D. Ohio

1972) (apprentices "shall be indentured from the eligible pool by

lottery"), aff'd in pertinent part. 489 F.2d 1023 (6th Cir.

City has undertaken to undo any resulting discriminatory impact

by hiring a sufficient ratio of minority applicants to achieve

the hiring goals." The intervenors, predominantly white fire

fighters unions, objected to the remedy which they regarded as "a

ratio or quota" but thought that that remedy was "preferable to

what they perceive as the dilution of hiring and promotion standa rds."

- 31

1973) .

The majority of courts and employers used the method

adopted by the Fire Department: a goal for the selection of

minorities was established which, if met, would eliminate the

adverse racial impact of the selection practice and prevent a

violation of Title VII. Of course, in effect, these methods are

all closely related as the Second Circuit has indicated:

Since interim hiring provisions, where needed to

satisfy immediate personnel requirements, are to

be used prior to the development and approval of a

valid selection procedure, such provisions cannot

meet Title VII standards by demonstrated job

relatedness. Therefore, one appropriate way to

assure Title VII compliance on an interim basis is

to avoid a disparate racial impact. This means

selecting from among adequately qualified either

on a random basis or according to some appro

priately noncompensatory ratio normally reflecting

the minority ratio of the applicant pool or the

relevant work force.

(Citations omitted), Guardians Ass'n of New York City v. Civil

Service Commission. 630 F.2d 79, 108-09 (2d Cir. 1980), aff1d on

Other grounds. 463 U.S. 582 (1983).

In general, courts and employers, like the Fire

Department, have preferred to use a specific ratio rather than

resort to a lottery. It is likely that others have preferred the

direct approach of establishing a ratio for reasons similar to

those described by the lower court: it provides an incentive and

reward to perform well on the test, provokes less opposition from

governmental bodies supervising selection for civil service

systems, "and presents a more feasible solution to the problem."

Op. at App. 58.

- 32

Accordingly, the courts have regularly approved the use

of ratios which remove adverse impact and preclude the operation

of a discriminatory practice until the implementation of a lawful

selection procedure. Se£, e. q. . Berkman v. City of._Ne.w__Yor.k, 705

F. 2d 584, 595-98 (2d Cir. 1983), affirming 536 F.Supp. 177, 216-

18 (E.D.N.Y. 1982); United States v. City of Chicago, 663 F.2d at

1361-62; Firefighters Institute v. City of St. Louis, 588 F.2d

235, 242 (8th Cir. 1978), cert, denied. 443 U.S. 904 (1979) ("We,

therefore, direct the District Court, on remand, to enter

an injunctive decree which requires that assignments to acting

fire captain positions reflect a fifty percent black ratio as far

as is practicable, pending the development of a valid examina

tion"); Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Rizzo. 13 FEP Cases 1475,

1481 (E.D.Pa. 1975); Oburn v. Shaop. 393 F.Supp. 561, 574-75

(E.D.Pa. 1975), aff1d. 521 F.2d 142 (3d Cir. 1975); Enslev

Branch. NAACP v. Seibels. 14 FEP Cases 670, 686-87

(N.D.Ala. 1977), aff1d. 616 F.2d 812 (5th Cir.), cert, deni ed.

449 U.S. 1061 (1980); see also. Local 53, Asbestos Workers

v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047, 1055 (5th Cir. 1969).

This particular use of affirmative action has occa

sioned little dispute because this use is merely a device to end

the discriminatory impact of an otherwise unlawful test, and

without the use of this form of affirmative action there could

often be no hiring for a considerable period of time. See

Op. at App. 64. This form of affirmative action implemented by

the Fire Department "only prevents additional discrimination,"

- 33

Oburn v. Shapp, 393 F.Supp. at 575, and "does not go beyond the

simple elimination of the disparate impact of the practice found

to be discriminatory and is properly regarded as compliance

relief," Be.rkman v, City of New York. 705 F.2d at 595.

Since the selection procedure is not job related, no

one can "seriously contend that [the affirmative action plan]

gives preference to some applicants over better qualified

applicants," Oburn v. shapp. 393 F.Supp. at 575; see also

Kirkland y. New York State Dept, of Correctional Services. 628

F.2d at 798. Moreover, "[n]o person has a vested interest in any

specific position on an eligibility list based upon a

discriminatory promotion examination; if a person appears in a

certain position on an eligibility list prepared in violation of

the law, his right to remain in that certain rank must give way

to the lawful requirement to avoid discriminatory promotions."

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Rizzo. 13 FEP Cases at 1481.

Furthermore, "white applicants have little expectation of being

hired merely because they passed the entry level test." Op. at

App. 64.

3. The Use of Affirmative Action to Neutralize

the Discriminatory Consequences of an Invalid

Selection Procedure is Authorized by the EEOC's

Affirmative Action Guidelines

The hiring affirmative action plan is consistent with

administrative agency guidelines. In 1979 the EEOC issued

Guidelines setting forth the standards for appropriate affirma

- 34 -

The EEOC enacted these Guide-tive action, 29 CFR Part 1608.50

lines to define lawful affirmative action because "[m]any

decisions taken pursuant to affirmative action plans or programs

have been race, sex, or national origin conscious in order to

achieve the Congressional purpose of providing equal employment

opportunity" and "[a]ny uncertainty as to the meaning and

application of Title VII [with respect to affirmative action]

threatens the accomplishment of the clear congressional intent to

encourage voluntary affirmative action," 29 C.F.R. § 1608.1(a).

The EEOC determined that "reasonable [affirmative] action may

include goals and timetables or other appropriate employment

tools which recognize the race, sex, or national origin of

applicants or employees." 29 C.F.R. § 1608.4(c). The EEOC

stressed that "voluntary affirmative action cannot be measured by

Pursuant to Executive Order 12067 (June 30, 1978), which

was issued to implement Reorganization Plan Number 1 of 1978, 43

Fed.Reg. 19807, the EEOC was designated as the lead federal

agency for the formulation of employment policy. In particular,

the Executive Order provides as follows:

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission shall

provide leadership and coordination to the efforts

of Federal departments and agencies to enforce all

Federal statutes, Executive orders, regulations,

and policies which require equal employment

opportunity....

The EEOC is charged with "develop[ing] uniform standards,

guidelines, and policies defining the nature of employment

discrimination" and all Federal departments are directed to

"cooperate with and assist the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission in the performance of its functions under this orde r...." £d.

The text of the Affirmative Action Guidelines is set out below at 10a-16a.

35

the standard of whether it would have been required had there

been litigation, for this standard would undermine the legisla

tive purpose of first encouraging voluntary action without

litigation." 29 C.F.R. § 1608.1(c).

In particular, the Guidelines direct employers to

engage in a "self analysis" in order to determine inte.r alia>

whether there is a "reasonable basis" for concluding that its

employment practices "[hjave or tend to have an adverse effect on

employment opportunities of ... groups whose employment ... op

portunities have been artificially limited...." 29 C.F.R.

§ 1608.4(b). If there is a "reasonable basis" for so concluding,

as there is with respect to the use of the hiring procedure for

the Fire Department, the employer may take reasonable action

"including] goals and timetables.... [and] the adoption of

practices which will eliminate the actual or potential adverse

impact...." 29 C.F.R. § 1608.4(c).

The EEOC Affirmative Action Guidelines sanction the

Fire Department's affirmative action plan. Furthermore, the

Equal Employment Opportunity Coordinating Council,5-1- issued a * 42

C 1 The Equal Employment Opportunity Coordinating Council was

created by P.L. No. 92-261, effective March 24, 1972, which

amended Title VII. As amended, Section 715 of Title VII,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-14, provided that the Council would have the

responsibility to coordinate the Federal Government's enforcement

of the fair employment laws. The Council was composed of the

Secretary of Labor, the Chairman of the Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Commission, the Attorney General, the Chairman of the

United States Civil Service Commission, and the Chairman of the

United States Civil Rights Commission or their respective

delegates. The Council was abolished, effective July 1, 1978,

pursuant to Reorganization Plan No. 1 of 1978, Sec. 6 , 43

Fed.Reg. 19807, 92 Stat. 3781; Executive Order 12067, June 30,

36

"Policy Statement on Affirmative Action Programs for State and

Local Government Agencies," 41 Fed.Reg. 38,814 (Sept. 13, 1976).

This Statement issued by the Justice Department and the other

federal government agencies responsible for the enforcement of

the fair employment laws approves the type of affirmative action

plan developed for the District of Columbia's Fire Department.

This Policy Statement was adopted and reissued by the govern

mental agencies, including the Justice Department, which signed

the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures. See

28 CFR § 50.14(17), set forth at 7a-9a below.

The Policy Statement expressly approves " [t]he estab

lishment of a long-term goal, and short-range, interim goals and

timetables...." and for "[rjevamping selection instruments or

procedures which have not yet been validated in order to reduce

or eliminate exclusionary effects on particular groups in

particular job classifications...." § 50.14(17(3) (a)) , -(d). It

is an ironic and an inappropriate, if not illegal, form of

federal bureaucratic mismanagement for the Department of Justice

to maintain that a local government violates the Constitution and

federal law when it follows Guidelines and a Policy Statement

signed by the Justice Department and other federal agencies.

4. The Use of Affirmative Action to Neutralize

the Discriminatory Consequences of an

Invalid Selection Procedure is Authorized

by the Justice Department's Own Regulations

Section 6A of the Uniform Guidelines, codified in the

1978, 43 Fed.Reg. 28967.

37

Justice Department's regulations at 28 C.F.R. § 50.14(6A), states

in its entirety:

Sec. 6 . Use of selection procedures which

have not been validated.---A. Use of alternate

selection procedures to eliminate adverse impact.

A user may choose to utilize alternative selection

procedures in order to eliminate adverse impact or

as part of an affirmative action program. See

section 13 below. Such alternative procedures

should eliminate the adverse impact in the total

selection process, should be lawful and should be

as job related as possible.

The Justice Department joined with the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission, the Office of Personnel Management, the

Department of Labor, and the Department of the Treasury, in the

March 2, 1979 joint Adoption of Questions and Answers to Clarify

and Provide a Common Interpretation of the Uniform Guidelines on

Employee Selection Procedures, 43 Fed.Reg. 11996.52 The Ques

tions and Answers make clear that the Fire Department's plan is

expressly authorized, and that the Attorney General has, in

essence, sued the Fire Department for having the temerity to rely

on the Justice Department's own regulations.

Question and Answer 30, 43 Fed. Reg. 12001, for

example, state in pertinent part:

30. Q. When may a user be race, sex or ethnic

conscious?

A. ... A user may justifiably be race, sex

or ethnic conscious in circumstances

where it has reason to believe that

qualified persons of specified race, sex

of ethnicity have been or may be subject

to the exclusionary effects of its