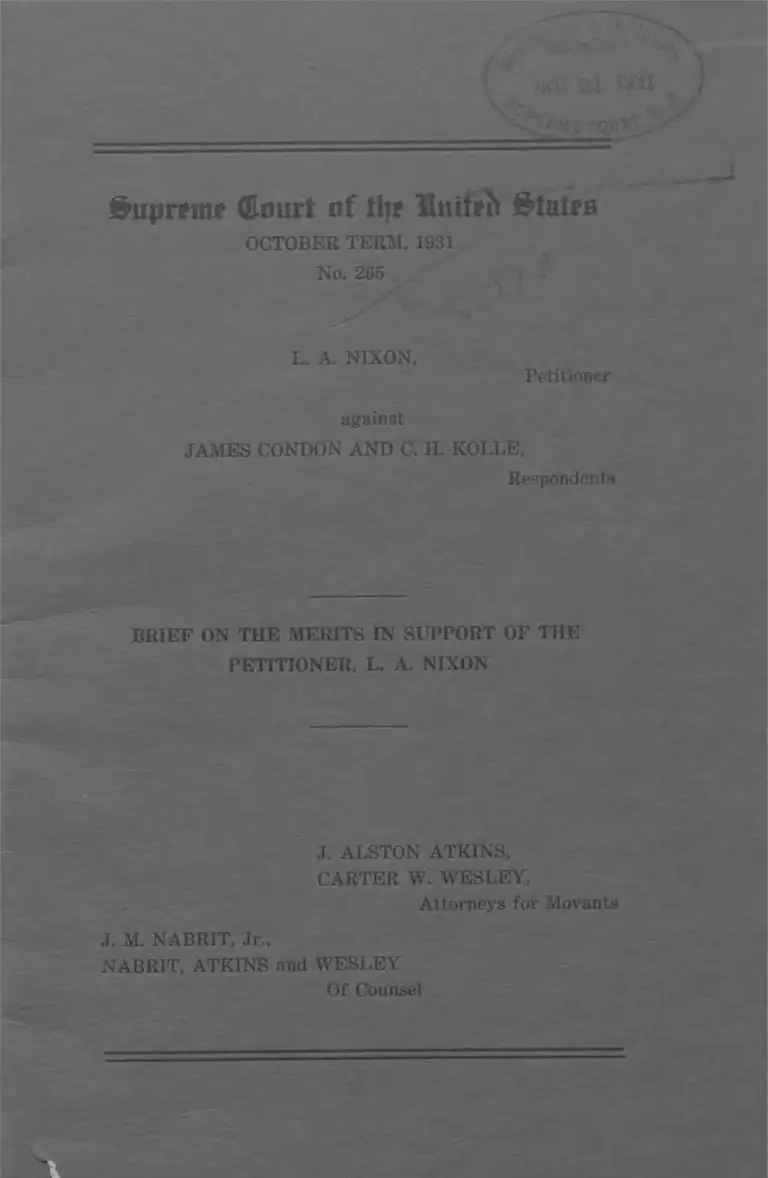

Nixon v. Condon Brief on the Merits in Support of the Petitioner, L.A. Nixon

Public Court Documents

November 21, 1931

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Nixon v. Condon Brief on the Merits in Support of the Petitioner, L.A. Nixon, 1931. ec5ee4a7-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8defb8a7-988b-4679-bc50-db0602fda7bc/nixon-v-condon-brief-on-the-merits-in-support-of-the-petitioner-la-nixon. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

^ujiremr (£ourt o f tlf* Httiirb

OCTOBER TERM, 1931

No. 265

L. A. NIXON,

Petitioner

against

JAMES CONDON AND C. H. KOLLE,

Respondents

BRIEF ON THE MERITS IN SUPPORT OF THE

PETITIONER, L. A. NIXON

J. ALSTON ATKINS,

CARTER W. WESLEY,

Attorneys for Movants

J. M. NABRIT, Jr.,

NABRIT, ATKINS and WESLEY

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF 1

CERTIFICATE OF COUNSEL ......................................... 3

BRIEF ON THE MERITS .................................................. 4

Decisions Below ............................................................ 4

Jurisdiction ........................ 4

Statement of the Case ................................................. 5

ARGUMENT:

Summary ........................................................................ 8

Detailed Argument ...................................................... 10

POINTS:

1. The statute is unconstitutional because, on its

face, it creates an arbitrary, unreasonable, and un

fair classification, which denies to plaintiff the

equal protection of the laws ................................... 10

2. The statute is unconstitutional because, as inter

preted by the state courts and the lower Federal

Courts, it recognizes an unconstitutional discrimi

nation against plaintiff and all other qualified

Negroes ........................................................................ 11

3. The purpose and intent of the Legislature in pass

ing the statute was to accomplish by indirect ac

tion that which the Supreme Court of the United

States had held in Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S.

536, it was without power to do by direct enact

ment .............................;................................................ 12

Judicial Knowledge ................................................... 13

Intent Shown by Emergency Clause ...................... 14

\

ii

Intent Shown by Legislative Debate ...................... 15

Intent Shown by Historical Facts ........................... 17

History of Effort To Bar Negroes From Demo

cratic Primaries ........................................................ 17

PAGE

4. The statute is unconstitutional because in its ope

ration, it is used as one of the instrumentalities by

which, with the approval of the State of Texas,

the plaintiff and all other qualified Negroes are

deprived of their legal right to vote in the statu

tory primary election involved in this case............ 20

5. The resolution is no defense to this suit because

plaintiff had a legal right to vote in said election

and defendants’ action in depriving him of that le

gal right was a legal w rong....................................... 21

6. The State of Texas could not by statute grant

immunity to defendants from the consequences of

that wrong (Nixon v. Herndon, supra), and, a for

tiori, the State Democratic Executive Committee,

whether it be a creature of the State or merely a

body of private individuals, has no power to grant

such immunity ............................................................ 21

7. The jurisdictional power of Federal Courts to

grant relief in any case is not limited to the en

forcement of Federal rights or to acts done either

by State Officers or in the execution of state

power ........................................................................... 23

8. The disfranchisement of plaintiff and other quali

fied Negroes disclosed by the record violates the

15th Amendment, because citizens of one race

iii

were guaranteed by law the right to vote in the

statutory election involved in this case, while

plaintiff and other qualified Negroes were not..... 24

9. This Court should decide all of the questions in

volved in this case, especially those pertaining to

the “inherent power” and “private individuals”

arguments, in order to prevent a multiplicity of

suits and to prevent undue hardship upon plaintiff

PAGE

and all other qualified Negroes in Texas ................25

CONCLUSION ...................................................................... 26

CASES CITED

Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U. S. 219 ....................................... 20

Blethen v. Bonner, 52 S. W. 571 ......................................... 14

Bliley v. West, 42 Fed (2nd) 101 ................................. 4, 12

Chicago v. Kendall, 266 U. S. 9 4 ......................................... 4

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ........................................... 22

Clancy v. Clough, —Tex— , 30 S. W. (2nd) 569 .............. 21

Columbus R. Co. v. Columbus, 249 U. S. 399 .................. 4

Connole v. Norfolk, etc., 216 Fed 823 ............................... 13

Connolly v. Union Sewer Pipe Co., 184 U. S. 540..........10, 11

Ex Parte Davidson, 57 Fed 883 ........................................... 14

Faris v. Hope, 298 Fed 727 ................................................. 13

Green v. Ry., 244 U. S. 499 ................................................... 4

Grigsby v. Harris, 27 Fed (2nd) 942 ............................... 25

Kaye v. May, 296 Fed 450 .................................................. 13

Knower v. Haines, 31 Fed 513 ........................................... 13

L. and N. Ry. v. Garrett, 231 U. S. 298, ............................ 24

Lamar v. Micou, 114 U. S. 218 ........................................... 13

\

IV

PAGE

Love v. The City Democratic Committee, No. 438 in

Equity, U. S. Dist. Ct. at Houston ............................... 25

Love v. Wilcox et al, — Tex— , 28 S. W. (2nd) 515 10, 17,

21, 24

M. K. T. Ry. v. Mcllhaney, 129 S. W. 153 ........................ 14

Mills v. Green, 159 U. S. 651 ............................................... 13

Muller v. Oregon, 208 U. S. 4 1 2 ........................................... 14

Nixon v. Condon, et al, 49 Fed (2nd) 1012.... 4, 5, 8, 21, 22

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 ......................5, 9, 12, 13, 14

15, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26

Quinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 ............................... 15

Quon Wing v. Kirkendall, 223 U. S. 59 ............................ 13

Rose Mfg. Co. v. Western Union Tel. Co., 251

S. W. 337 ........................................................................... 14

Siles v. L. and N. Railway, 213 U. S. 175 ......................... 24

Simpson v. United States, 252 U. S. 547 ............................ 14

State v. Meharg, 287 S. W. 670 .....................................14, 26

Southern Ry. Co. v. Greene, 216 U. S. 400 ........................ 11

Swafford v. Templeton, 185 U. S. 487 ............................. 5

Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312 ....................................... 11

United States v. Reese, 92 U. S. 2 1 4 .............................. 5, 24

United States v. Sanders, 290 Fed 428 ............................ 14

United States v. Wallace, 279 Fed. 401 ............................ 14

Weaver v. Palmer Bros. Co., 270 U. S. 402 ........................ 13

West v. Bliley, 33 Fed (2nd) 177 ....................................... 12

White v. Lubbock, et al., —Tex— , 30 S. W. (2nd) 722... 10,

12, 21, 24, 25

Wiley v. Sinkler, 179 U. S. 58 ............................................. 5

V

PAGE

Wiley v. Webber, et al, No. 432 in Equity, U. S. Dist. Ct.

at San Antonio .................................................................. 25

Williams v. Castleman, 247 S. W. 263 ............................... 14

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 ............................ 11, 21

REFERENCES TO CONSTITUTION

Constitution of the United States:

Fourteenth Amendment ....................................8, 14, 15

Fifteenth Amendment .........................................8, 9, 24

UNITED STATES STATUTORY REFERENCES

Judicial Code:

Section 24 (1) ................................................................ 4

Section 24 (11) .............................................................. 5

Section 24 (12) .............................................................. 5

Section 24 (14) ............................................................ 5

United States Code:

Title 8, Section 31 ........................................................ 5

Title 8, Section 43 ......................................................... 5

TEXAS STATUTORY REFERENCES

Revised Civil Statutes of 1925:

Article 2642 .................................................................... 27

Article 3002 ...................................................................... 6

Articles 3100 to 3153 (inclusive) ............................ 5

Article 3104 .................................................................... 6

Article 3105 .................................................................... 6

Article 3107 ........................ 6, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20

Title 49, Chapters 1 to 9 (inclusive) .......................... 26

Resolutions of Democratic State Executive

Committee ................................................................. 7

Laws of 1927:

Chapter 67 ...................................................................... 6

House Journal:

First Called Session of the 40th Legislature 15, 16

&uprrmr (fimirt of tlje Unitpfc &tatro

OCTOBER TERM, 1931

No. 265

L. A. NIXON,

Petitioner,

against

JAMES CONDON AND C. H. KOLLE,

Respondents.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF ON THE

MERITS, AND BRIEF ATTACHED THERETO,

IN SUPPORT OF THE PETITIONER,

L. A. NIXON

TO THE HONORABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE AND

ASSOCIATE JUSTICES OF THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE UNITED STATES:

C. N. Love, Julius White, The Houston Informer and Tex

as Freeman, and their attorneys herein, individually and on

behalf of all other Negroes in the City of Houston, in Har

ris County, and the State of Texas, who are not otherwise

represented, hereby respectfully move this Honorable Court

for leave to file, as amici curiae, the brief hereto attached,

as a brief upon the merits in the above styled and number

ed cause, in support of the petitioner, L. A. Nixon.

In support of this motion movants respectfully show that

there are in their opinion important arguments and mat

ters, pertinent to the issues involved in this case, which

have not heretofore or otherwise been called to the atten-

should have before it in deciding this case upon the merits.

■— ^ / ?'•.

As evidence thereof, without asking the Court to read the

2

entire brief for this purpose, movants call attention to Point

No. 1 in said brief, which is hereby incorporated into this

motion by reference.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, movants pray that

this Honorable Court may grant them leave to file the brief

attached hereto as a brief upon the merits, in support of the

petitioner, L. A. Nixon.

Dated November 18, A.

C. N. LOVE

JULIUS WHITE

THE HOUSTON^FORMER AND TEXAS

FREEMAN

By G. H. WEBS

J. ALSTON ATKII

One of Attorneys for Mbvants

Office and Post Office Address

409 Smith Street, Houston, Texas.

THE STATE OF TEXAS

COUNTY OF HARRIS

Before me, the undersigned authority, on this day per

sonally appeared C. N. Love, Julius White, G. H. Webster,

and J. Alston Atkins, who, having been by me first duly

sworn, on their oaths depose and say:

That they are the identical persons who executed the

within and foregoing motion, and that the allegations there

in set forth are true, according to their best knowledge and

belief.

Subscribed and sworn to before me this JJie l£th day of

November, A. D., 1931.

LELAND D. EWING'

I Notary Public in and for Harris County,

Texas.

(SEAL)

My commission expires June 1, 1933.

t

3

CERTIFICATE OF COUNSEL

I hereby certify that in my opinion the foregoing motion

for leave to file brief is well founded in law, and is filed in

good faith and not for delay.

J. ALSTON ATKIT

One of Attorri^ys fbr/

&ujjr*mr (Enurt of tlje Initeii States

OCTOBER TERM, 1931

No. 265

L. A. NIXON,

Petitioner,

against

JAMES CONDON AND C. H. KOLLE,

Respondents.

BRIEF ON THE MERITS IN SUPPORT OF THE

PETITIONER, L. A. NIXON

DECISIONS BELOW

The decisions in the courts below, which are sought to be

reversed here, are: Nixon v. Condon et al., 34 Fed. (2nd)

464, and Nixon v. Condon et al., 49 Fed (2nd) 1012.

JURISDICTION

There are at least three grounds upon which jurisdiction

may be sustained in this case:

1. That the matter in controversy exceeds in val

ue the sum of $3,000 and involves a substantial

Federal question. Sec. 24 (1) of the Judicial Code;

Chicago v. Kendall, 266 U. S. 94; Green v. Ry. 244

U. S. 499; Columbus R. Co. v. Columbus 249 U. S.

399.

That there is at least a substantial Federal question in

volved is indicated by the fact that the Circuit Court of Ap

peals for the Fourth Circuit has held to be unconstitutional

a state statute similar to the one alleged in this case to be

unconstitutional. Bliley v. West, 42 Fed (2nd) 101.

2. That the controversy involves rights created

by the Constitution and laws of the United States,

and is, therefore, in its “ essence Federal,” “ however

4

5

much wanting in merit may be the averments

which it is claimed establish the violation of the

Federal right.” Swafford v. Templeton, 185 U. S.

487.

The right to vote for senator and representatives in Con

gress is created by the Constitution and laws of the United

States. Wiley v. Sinkler, 179 U. S. 58; Swafford v. Temple

ton, supra.

The right to “ exemption from discrimination in the exer

cise of the elective franchise on account of race, color, or

previous condition of servitude” is also created by such

Constitution and laws. United States v. Reese, 92 U. S.

214.

These two Federal rights are the foundation of this con

troversy.

3. That this is a suit to recover damages for the

deprivation of one of the civil rights, namely, the

right to vote. Judicial Code, Sec. 24 (11) (12)

(14); Secs. 31, 43, Title 8, United States Code; Nix

on v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536.

Even the Circuit Court of Appeals in the instant case

concedes that plaintiff had a legal right to vote in the pri

mary election involved in this case.

“ It is of course to be conceded, since the decision

in Nixon v. Herndon, supra, that the right of a qua

lified citizen to vote extends to primary elections as

well as to general elections.” Nixon v. Condon et

al., 49 Fed. (2nd) 1012, 1013.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

By the Election Laws of Texas, Title 50, Chapter 13,

Articles 3100 to 3153, Revised Civil Statutes, the State re

quired that there be held on July 28, 1928, an election for

the purpose of nominating candidates for representatives in

the United States Congress, for United States senator, and

for state, county, district, and precinct officers in the State

of Texas. With great particularity, these statutes set

6

forth the time, place, and method of holding such election,

and the requirements for participation therein.

The defendants were election judges of said election,

their offices being created by said Election Laws (Article

3104); and as such judges, they were clothed by statute

(Articles 3002 and 3105 of said Election Laws) with, among

others, the following sovereign powers of the state of Tex

as: To administer oaths; to act with the same power as a

district judge to enforce order and keep the peace; to ap

point special peace officers; to issue warrants of arrest for

felony, misdemeanor or breach of peace; to authorize con

finement of persons arrested to jail; to compel observance

of law against loitering or electioneering within 100 feet

of polling places; to arrest or cause to be arrested anyone

carrying voters to polls contrary to law.

No private individual or organization has any such pow

ers as these.

The plaintiff was a member of the Democratic Party and

a duly qualified elector and voter under the laws of the

State of Texas, except that he was a Negro, and he attempt

ed to vote in said election.

The defendants denied plaintiff the right to vote in said

election, defending their action under the following statute

and resolution:

Chapter 67 of the Laws of 1927, passed by 1st called

session of 40th Legislature of Texas, which is now Article

3107 of the Revised Civil Statutes of Texas:

“ AUTHORIZING POLITICAL PARTIES THROUGH

STATE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEES TO

PRESCRIBE QUALIFICATIONS

OF THEIR MEMBERS

(H. B. No. 57)

Chapter 67

“ An act to repeal Article 3107 of Chapter 13 of

the Revised Civil Statutes of Texas, and substitut

7

ing in its place a new article providing that every

political party in this State through its State Execu

tive Committee shall have the power to prescribe the

qualifications of its own members and shall in its

own way determine who shall be qualified to vote

or otherwise participate in such political party, and

declaring an emergency.

“ Be it enacted by the Legislature of the State of

Texas:

“ Section 1. That Article 3107 of Chanter 13 of

the Revised Civil Statutes of Texas be and the same

is hereby repealed and a new article is hereby en

acted so as to hereafter read as follows:

‘Article 3107. Every political partv in this State

through its State Executive Committee shall have

the power to prescribe the qualifications of its own

members and shall in its own way determine who

shall be qualified to vote or otherwise participate

in such political party: provided that no person shall

ever be denied the right to participate in a nrimarv

in this State because of former political views or

affiliations or because of membership or non-mem

bership in organizations other than the political par

ty.’

“ Sec. 2. The fact that the Supreme Court of 1he

United States has recently held Article 3107 invalid,

creates an emergency and an imperative public

necessity that the Constitutional Rule requiring bills

to be read on three several days in each House be

suspended and said rule is hereby suspended, and

that this Act shall take effect and be in force from

and after its passage, and it is so enacted.

“ Aproved June 7, 1927

“ Effective 90 days after adjournment.”

Resolution passed by the State Democratic Executive

Committee of Texas pursuant to the power either conferred

or recognized by the above quoted statute:

“ Resolved: That all white Democrats who are

qualified under the Constitution and laws of

Texas and who subscribe to the statutory pledge

provided in Article 3110, Revised Civil Statutes of

Texas, and none other, be allowed to participate in

8

the primary elections to be held July 28, 1928, and

August 25, 1928, and further, that the Chairman

and Secretary of the State Democratic Executive

Committee be directed to forward to each Democrat

ic County Chairman in Texas a copy of this resolu

tion for observance.”

Thereupon, plaintiff brought this suit for damages in the

sum of five thousand dollars ($5,000) for the legal wrong

done to him by defendants in depriving him of his legal

right to vote in said election; the plaintiff alleging that the

above statute and resolution were no defense and that they

violated his rights under the 14th and 15th Amendments to

the Constitution of the United States.

The District Court sustained a motion to dismiss, 34 Fed

(2nd) 464, and the Circuit Court of Appeals sustained the

decision of the District Court, 49 Fed (2nd) 1012.

Questions:

1. Is the above statute constitutional?

2. Is the above resolution a valid defense to this action?

3. Does the disfranchisement of plaintiff and the other

Negroes disclosed by the record violate the 15th Amend

ment?

ARGUMENT

SUMMARY:

1. The statute is unconstitutional because,

(a) On its face it creates an arbitrary, unreasonable, and

unfair classification, which denies to plaintiff and all

other qualified Negroes the equal protection of the

laws.

(b) As interpreted by the state courts and the lower

Federal Courts in Texas, it recognizes and enforces

an unconstitutional discrimination against plaintiff

and all other qualifed Negroes.

(c) The purpose and intent of the Legislature in passing

9

the statute was to accomplish by indirect action that

which the Supreme Court of the United States had

held in Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, it was with

out power to do by direct enactment.

(d) In operation the statute is used as one of the instru

mentalities, with the approval of the State of Texas,

by which the plaintiff and all other qualified Negroes

are deprived of their legal right to vote in the statu

tory primary election involved in this case.

2. The resolution is no defense to this action.

(a) Plaintiff had a legal right to vote in said election,

and defendants’ action in depriving him of that right

was a legal wrong.

(b) The State of Texas could not by statute grant im

munity to defendants from the consequences of that

wrong and, a fortiori, the State Democratic Execu

tive Committee, whether it be a creature of the

State, or merely a body of private individuals, could

not grant such immunity.

(c) The jurisdictional power of Federal Courts to grant

relief in any case is not limited to the enforcement of

Federal rights or to acts done either by State offi

cers, or in the execution of State power.

3. The disfranchisement of plaintiff and other qualified

Negroes disclosed by the record, violates the 15th

Amendment because citizens of one race were guaran

teed by law the right to vote in the statutory election

involved in this case, while plaintiff and other qualified

Negroes were not.

4. This Court should decide all of the questions involved

in this case, especially those pertaining to the “ inherent

power” and “ private individuals” arguments, in order

to prevent a multiplicity of suits and to prevent undue

10

hardship upon plaintiff and all other qualified Negroes

in Texas.

DETAILED ARGUMENT:

POINT I

The statute is unconstitutional because, on its face, it

creates an arbitrary, unreasonable, and unfair classification,

which denies to plaintiff the equal protection of the laws.

It provides:

“ Every political party in this State through its

State Executive Committee shall have the power to

prescribe the qualifications of its own members and

shall in its own way determine who shall be quali

fied to vote or otherwise participate in such political

party; provided that no person shall ever be denied

the right to participate in a primary in this State

because of former political views or affiliations or

because of membership or non-membership in or

ganizations other than the political party.”

The excepting provision “ that no person shall ever be de

nied the right to participate in a primary in this State be

cause of former political views or affiliations or because of

membership or non-membership in organizations other than

the political party” has been sustained by the Supreme

Court of Texas as forbidding the exclusion of a person who

neither had supported the Democratic Candidates in toto in

the past nor would promise absolutely to do so in the future.

Love v. Wilcox et al., — Tex.— , 28 S. W. (2nd) 515.

Likewise the power to exclude Negroes under the general

power either conferred or recognized by the statute has

been sustained by the Court of Civil Appeals of Texas, at

Galveston, in a case in which it was the court of last resort.

White v. Lubbock et al.

— Tex— , 30 S. W. (2nd) 722

In Connolly v. Union Sewer Pipe Co., 184 U. S. 540,

an anti-trust statute was held invalid under the equal

11

protection clause because it contained the excepting provi

sion that it should “ not apply to agricultural products or

live stock while in the hands of the producer or raiser.”

In the Connolly Case this court said at page 558:

“ But upon this general question we have said that

that the guarantee of the equal protection of the

laws means ‘that no person or class of persons shall

be denied the same protection of the laws which is

enjoyed by other persons or other classes in the

same place and in like circumstances.’ Missouri v.

Lewis, 101 U. S. 22, 31.”

The denial of equal protection is clear.

“ Immunity granted to a class, however limited,

having the effect to deprive another class, however

limited, of a personal or property right, is just as

clearly a denial of equal protection of the laws to the

latter class as if the immunity were in favor of, or

the deprivation of right permitted worked against a

larger class.” Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312,

333.

“ The equal protection of the laws is a pledge of

the protection of equal laws.” Yick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U. S. 356, 369.

“ While reasonable classification is permitted,

without doing violence to the equal protection of the

laws, such classification must be based upon some

real and substantial distinction, bearing a reason

able and just relation to the things in respect to

which such classification is imposed; and classifica

tion cannot be arbitrarily made without any sub

stantial basis.”

Southern Ry. Co. v. Greene

216 U. S. 400, 417.

What could be more unfair, arbitrary, unreasonable, and

unjust than the exemption in this case which forbids the

exclusion of disloyal white Democrats, while permitting the

exclusion of Negro Democrats on the ground of race and

color alone?

POINT II

The statute is unconstitutional because, as interpreted

12

by the state courts and the lower Federal courts, it recog

nizes an unconstitutional discrimination against plaintiff

and all other qualified Negroes.

That the state law sought to be declared unconstitutional

in this case does recognize and protect the power of the

State Democratic Executive Committee to deprive Negroes

of their legal rights upon the ground of color alone is clear.

In the case of White v. Lubbock, —Tex.— , 30 S. W. (2nd)

722, it is held that the resolution involved in this case was

a “ valid exercise through its proper officers of such party’s

inherent power, (recognized, but not created by R. S. Arti

cle 3107) * * * ” In that case the Court of Civil Appeals

was the court of last resort in Texas.

In the instant case, the Circuit Court of Appeals held

“ The act of 1927 was not needed to confer such power, it

merely recognized a power that already existed.”

As to the power of the State of Texas, thus to recognize

and protect the State Democratic Executive Committee in

depriving Negroes of their legal right to vote in the Texas

statutory primary the holding of Judge Groner in West v.

Bliley, 33 Fed (2nd) 177, 180, which was adopted by the

Circuit Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in Bliley v.

West, 42 Fed (2nd) 101, is pertinent:

“That a law which recognizes or which authorizes

a discrimatory test or standard does curtail and sub

vert them (“ the provisions of the Constitution and

the rights of voters” ) there can be no doubt, and

such a law is therefore in conflict with the Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitu

tion of the United States.”

POINT III

The purpose and intent of the Legislature in passing the

statute was to accomplish by indirect action that which the

Supreme Court of the United States had held in Nixon v.

13

Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, it was without power to do by di

rect enactment.

The statute was passed as an emergency measure, and

the reason therefor is stated in Section 2 of the Act as fol

lows:

“The fact that the Supreme Court of the United

States has recently held Article 3107 invalid, creates

an emergency and an imperative public necessity

that the Constitutional Rule requiring bills to be

read on three several days in each House be suspend

ed and said rule is hereby suspended, and that this

Act shall take effect and be in force from and after

its passage, and it is so enacted.”

Judicial Knowledge

In the first place we mention the fact that the Supreme

Court of the United States has held that a statute’s or

law’s “ invalidity may be shown by things which will be ju

dicially noticed.” Weaver v. Palmer Bros. Co., 270 U. S.

402, 410, but it has also been held that, unless these mat

ters and things to be judicially noticed are called by counsel

to the attention of the court, it will not notice them. “ There

are many things that courts would notice if brought before

them that beforehand they do not know.” Mr. Justice

Holmes in Quong Wing v. Kirkendall, 223 U. S. 59, 64.

The Federal Courts will take judicial notice of the laws

of every state. Mills v. Green, 159 U. S. 651; Lamar v. Mi-

cou, 114 U. S. 218.

The Federal Courts take judicial notice of those laws

created by statute or judicial decisions. Faris v. Hope, 298

Fed 727; Kaye v. May, 296 Fed 450; Knower v. Haines, 31

Fed 513.

Federal Courts will take judicial notice of legislative

journals. Connole v. Norfolk, etc., 216 Fed 823.

Federal Courts take judicial notice of historical facts.

14

Simpson v. United States, 252 U. S. 547; United States v.

Wallace, 279 Fed 401; Ex Parte Davidson, 57 Fed 883.

Texas cases to the same effect are: Blethen v. Bonner, 52

S. W. 571; Williams v. Castelman, 247 S. W. 263.

Federal Courts take judicial notice of matters of common

knowledge. Muller v. Oregon, 208 U. S. 412; United States

v. Sanders, 290 Fed 428. Texas cases to same effect are:

State v. Meharg, 287 S. W. 670; M. K. T. Ry. v. Mellhaney,

129 S. W. 153; Rose Mfg. Co. v. Western Union Tel. Co., 251

S. W. 337.

Intent Shown By Emergency Clause

Prior to the decision in Nixon v. Herndon, supra, old

Article 3107 of the Revised Civil Statutes of Texas read as

follows, and contained no other provision:

“ In no event shall a Negro be eligible to participate in a

Democratic party primary election held in the State of Tex

as, and should a Negro vote in a Democratic primary elec

tion, such ballot shall be void and election officials shall not

count the same.”

This old Article 3107 dealt with only one subject, namely,

the exclusion of Negroes from voting in the Texas Demo

cratic primaries.

The said case of Nixon v. Herndon dealt with only one

subject, namely, the legal right of Negroes to vote in the

Texas Democratic primaries and the validity under the 14th

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of said

old Article 3107, which sought to deprive Negroes of that

right.

Upon the decision by the Supreme Court in said case of

Nixon v. Herndon that Negroes had a legal right to vote in

the Texas Democratic primaries and that old Article 3107,

which sought to deprive them of that right, was a violation

15

of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States, the 1st Called Ses

sion of the 40th Legislature of Texas passed new Article

3107, which is in controversy in this suit, stating in the

face of the new Artcle 3107 that the reason for its prompt

passage was that the Supreme Court of the United States

had created, by the said case of Nixon v. Herndon, “an

emergency and an imperative public necessity” ; which, we

believe, shows on its face that the intent of the Legislature

was nothing more than to circumvent, if possible, the deci

sion of the Supreme Court of the United States in the said

case of Nixon v. Herndon, and, if our belief is well founded,

said new Article 3107, under Quinn v. United States, 238 U.

S. 347, is just as unconstitutional as if the intent to exclude

Negroes had been in words stated on the face of the Article

itself.

Intent Shown By Legislative Debate

The debate in the Texas House of Representatives upon

the passage of said new Article 3107, which was House Bill

No. 57, we believe, shows that the purpose of passing said

Article was to circumvent, if possible, the decision of the

Supreme Court of the United States in said case of Nixon

v. Herndon.

The House Journal of the 1st called Session of the 40th

Legislature of Texas shows the following:

At page 302, Representative Faulk said: “ I voted against

House Bill No. 57 because it confers too much authority on

thirty-one members. I sought to amend the bill by provid

ing that these thirty-one men shall never prescribe proper

ty holding as a qualification of voting. As passed, the act

empowers the State Executive Committee to prescribe with

out limit the qualifications of a voter, and they have ample

power under the act to say that a man must be a Methodist,

16

a Mason, and a millionaire. This savors of autocracy and

I will not sanction it by my vote. I will support any rea

sonable bill to curb the negro vote.”

On the same page, Representative Stout said: “ I voted

‘nay’ on House Bill No. 57 for the following reasons:

“ In the first place, it is doubtful if the bill will accomplish

its purpose, in view of the recent holding of the Supreme

Court of the Unted States.

“ On the other hand, admitting for the sake of argument

that it would do so, then I am not willing to turn my gov

ernment over to a small number of men who compose the

State Executive Committee.

“ The South has always handled the ‘nigger’ in a satis

factory manner, and I believe that it will continue to do so.

“ In my humble judgment, it is far more dangerous to

entrust our whole political destiny to a few men than the

scare of the negro question would ever be. It is a matter

of common knowledge that we, the people of Texas, have

always voted our prejudices too often in the past. I fear

that the pendulum might swing too far one way or the oth

er, and that the day might come back when a few clicks

and klans might run out the unterrified Democrats, or that

the unterrified Democrats might get in the saddle and oust

the kluckers, as they came close to doing in the past.

“ I believe the whole affair makes a mountain out of

nothingness, and that it is un-American and un-Democratic.

I had rather take my chances on handling the ‘nigger’ than

I would on thirty-one men who would have final authority

to determine who should vote and who should not vote, and

who should be a Democrat or not be a Democrat.

“ The Constitution of Texas prescribes the qualifications

of a voter—about that there can be no doubt. The Su

preme Court has held a ‘nigger’ can vote under the present

primary law. About that there can be no doubt. If the

17

primary election is an ‘election’ in the proper and legal

sense, then a ‘nigger’ can vote, and no law can stop him.

“ If a primary is not an election, as our Texas courts have

said in the past, the State Executive Committee would have

the same blanket authority to judge the qualifications of its

own members, as does the Baptist Church. It could ostracise

a man at will and set up a standard to suit itself. In that

respect and to that extent we would be going back to the

days of crowns and jeweled baubles of Bolsheviki Russia.

“ It was Abraham Lincoln who said, ‘The heart of the

American people has never failed in a great crisis, and it

never will.’ To that philosophy I conform, when the whole

people have a chance to record their sentiments. But I am

not willing to trust my government and politics to what

could very easily become an oligarchy.”

Intent Shown By Historical Facts

Senator Thomas B. Love, who was a member of the Texas

Senate when said Article 3107 was passed, filed a brief,

signed by himself, in the Supreme Court of Texas, in the

case of Love v. Wilcox, 28 S. W. (2nd) 515, upon which the

Supreme Court granted him relief in that case, in which he

set out, in the following historical statement, the fact, that

said new Article 3107 had “ no other purpose whatsoever”

than “ to provide, if possible, other means by which negroes

could be barred from participation, both as candidates and

as voters, in the primary elections of the Democratic party,

which would stand the test of the courts” :

“HISTORY OF EFFORT TO BAR NEGROES FROM

DEMOCRATIC PRIMARIES”

“ Prior to 1903, there was no law in Texas regulating

primary elections or party nominations, and such elections

and nominations, and the control and regulations of all af

18

fairs of political parties was vested entirely in party con

ventions and executive committees. In that year, 1903, the

Texas Legislature, for the first time, provided for regulat

ing party primary elections and conventions, and party af

fairs, by law, through the passage of the first Terrell Elec

tion Law, which completely divested party conventions and

committees of the control theretofore exercised by them.

“ From the beginning of election legislation, the questions

of barring or admitting negroes in Democratic primary elec

tions was an important one, some counties, through their

representatives, desiring that negroes be allowed to vote in

Democratic primaries, while others strenuously insisted

that they should be barred by statewide law. The first

Terrell election law relegated this subject to the party

executive committees of the various counties by the follow

ing provision:

‘The County Executive Committee of the party

holding any primary election may prescribe addi

tional qualifications necessary to participate there

in;’ (see Section 94, p. 150, Acts of the First Called

Session, 28th Legislature, 1903.)

“ When the Terrell Election Law was generally revised by

the Twenty-ninth Legislature in 1905, this same provision

was re-enacted in the following language:

‘The Executive Committee of any party for any

county may prescribe additional qualifications for

voters in such primary not inconsistent with this

Act.’

“ This same provision, in the same words, was re-enacted

in the codification of the Revised Statutes of 1911, (see

Art. 3093, R. C. S. 1911) and remained in force until 1923.

“ Thus, from 1903 until 1923, just twenty years, the elec

tion laws of Texas provided that all qualified voters should

be qualified to vote in any party primary, upon taking the

Drescribed party test, and provided no other statewide quali

19

fications whatever for primary election voters, but, in ef

fect, enabled a political party in any county to bar negroes

if it saw fit to do so by prescribing ‘additional qualfica-

tons.’

“Original Enactment of Article 3107”

“ The Second Called Session of the Texas Legislature, in

1923, enacted a Statute amending Art. 3093, R. C. S. 1911,

designed specifically to bar Negroes from participating in

primary elections of the Democratic party in every county

in Texas, which afterward w'as codified as Art. 3107, R. C.

S. of 1925, and which read as follows:

‘Art. 3107: In no event shall a negro be eligible

to participate in a Democratic primary election held

in the State of Texas, and should a negro vote in a

Democratic primary election, such ballot shall be

void and election officers shall not count the same.’

“Article 3107 Held Unconstitutional”

“ It was the obvious purpose of this enactment to bar ne

groes not only from voting, but from participating in any

way, either as voters or as candidates, in Democratic pri

maries.

“ This Statute passed in 1923 was declared to be uncon

stitutional and void by the Supreme Court of the United

States, in 1927, in the case of Nixon v. Herndon, et al, Vol

ume 47, Supreme Court Reporter, page 446.

“Article 3107 Amended in 1927 so as to Give the State

Executive Committee Whatever Power

It Now Possesses”

“The Fortieth Legislature in its First Called Session held

in 1927, having in mind that, this Statute of 1923 had been

invalidated by the Courts, and desiring to provide, if pos

sible, other means by which negroes could be barred from

participation, both as candidates and as voters, in the pri

mary elections of the Democratic party, which would stand

V

20

the test of the Courts, and having no other purpose what

soever, passed a statute amending said Article 3107 so as

to read as follows:

‘Art. 3107: Every political party in this State,

through its State Executive Committee shall have

the power to prescribe the qualifications of its own

members, and shall in its own way, determine who

shall be qualified to vote or otherwise participate in

such political party; provided, that no person shall

ever be denied the right to participate in a primary

in this State because of former political views or af-

fliations, or because of membership or non-member

ship in organizations other than the political par

ty’.”

We close this point with the following quotation from a

decision by this Court:

“What the State may not do directly, it may not

do indirectly.” Bailey v. Alabama 219 U. S. 219.

POINT IV

The statute is unconstitutional because in its operation, it

is used as one of the instrumentalities by which, with the

approval of the State of Texas, the plaintiff and all other

qualified Negroes are deprived of their legal right to vote

in the statutory primary election involved in this case.

“ Without imputing any actual motive to oppress,

we must consider the natural operation of the

statute here in question (Henderson v. Mayor, 92

U. S. 268), and it is apparent that it furnishes a con

venient instrument for the coercion which the Con

stitution and the act of Congress forbid.” Bailey

v. Alabama, supra.

It is a matter of common and historical knowledge in

Texas that, under this statute and its predecessors, nobody

has been excluded from participation in the statutory pri

mary elections except Negroes.

It is also a fact that this practice has been sustained by

the Appellate Courts of Texas.

21

Love v. Wilcox et al, supra

White v. Lubbock et al, supra

In Clancy v. Clough, — Tex.— 30 S. W. (2nd) 569, the

Court of Civil Appeals at Galveston held that the party

committee was without power to place upon the statutory

primary ballot “ any pledge other than that prescribed by

the statute or one containing the additional word ‘white’ be

fore the word ‘Democrat’ in the pledge prescribed by the

statute.”

This Court has held that:

“Though the law itself be fair on its face and im

partial in appearance, yet, if it is applied and ad

ministered by public authority with an evil eye and

an unequal hand, so as practically to make unjust

and illegal discriminations between persons in simi

lar circumstances, material to their rights, the de

nial of equal justice is still within the prohibition of

the Constituton.” Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S.

356.

POINT V

The resolution is no defense to this suit because plaintiff

had a legal right to vote in said election, and defendants’

action in depriving him of that legal right was a legal

wrong.

This was determined by this Court in Nixon v. Herndon,

273 U. S. 536, and is conceded by the Circuit Court of Ap

peals in the instant case. On this point, the Court said:

“ It is of course to be conceded, since the decision

in Nixon v. Herndon, supra, that the right of a qua

lified citizen to vote extends to primary elections as

well as to general elections.” Nixon v. Condon, et

al. 49 Fed (2nd) 1012, 1013.

POINT VI

The State of Texas could not by statute grant immunity

to defendants from the consequences of that wrong (Nixon

v. Herndon, supra), and, a fortiori, the State Democratic

22

Executive Committee, whether it be a creature of the State

or merely a body of private individuals, has no power to

grant such immunity.

If a creature of the State, Nixon v. Herndon, supra, defi

nitely denies power to grant such immunity.

The Circuit Court of Appeals in this case based its deci

sion upon these grounds:

“ The distinction between appellants’ cases, the

one under the 1923 statute and the other under the

1927 statute, is that he was denied the permission

to vote in the former by state statute, and in the lat

ter by resolution of the State Democratic Executive

Committee.”

“A political party is a voluntary association, and

as such has the inherent power to prescribe the qua

lifications of its members. The act of 1927 was not

needed to confer such power; it merely recognized a

power that already existed.”

(a) The “private individuals” argument.

The following quotation from the opinion of this

court in the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, is a con

clusive answer to this argument:

“ In this connection it is proper to state that civil

rights, such as are guaranteed by the Constitution

against State aggression, cannot be impaired by the

wrongful acts of individuals, unsupported by State

authority in the shape of laws, customs, or judicial

or executive proceedings. The wrongful act of an in

dividual, unsupported by any such authority, is sim

ply a private wrong, or a crime of that individual; an

invasion of the rights of the injured party, it is true,

whether they affect his person, his property, or his

reputation; but if not sanctioned in some way by the

State, or not done under State authority, his rights

remain in full force, and may presumably be vindi

23

cated by resort to the laws of the State for redress.

An individual cannot deprive a man of his right to

vote, to hold property, to buy and sell, to sue in the

Courts, or to be a witness or a juror; he may, by force

or fraud, interfere with the enjoyment of the right

in a particular case; he may commit an assault

against the person, or commit murder, or use ruffian

violence at the polls or slander the good name of a

fellow citizen; but, unless protected in these wrong

ful acts by some shield of State law or State authori

ty, he cannot destroy or injure the right; he will only

render himself amenable to satisfaction or punish

ment; and amenable therefor to the laws of the State

where the wrongful acts are committed.”

(b) The “ inherent power” argument.

An analysis of Nixon v. Herndon, supra, is a com

plete answer to this argument.

After this court had stricken down the state statute held

unconstitutional in Nixon v. Herndon, supra, the defendants

were left with the same power that they have in this case.

The statute disposed of, if the defendants had “ inherent

power” beyond statutory control to exclude plaintiff, this

Court would not have granted relief. The fact that this

Court did not recognize any such power shows that none

existed. Defendants in this case being identical in capacity

with defendants in Nixon v. Herndon, they have no greater

powers than were there recognized.

POINT VII

The jurisdictional power of Federal Courts to grant relief

in any case is not limited to the enforcement of Federal

rights or to acts done either by State officers or in the exe

cution of state power.

This proposition has become almost axiomatic; and it is

24

settled that, once the jurisdiction of the Federal Court at

taches, it has jurisdictional power to grant whatever re

lief, whether State or Federal, may be disclosed by the rec

ord.

Siles v. L. and N. Railway

213 U. S. 175, 191

L. and N. Ry. v. Garrett

231 U. S .298,304

The assumption by the lower courts in this case that they

could not grant relief against the deprivation of the right,

which the Circuit Court of Appeals said existed, simply be

cause the deprivation was not by the State, is, therefore,

clearly unfounded. Indeed, inquiry into the capacity of the

defendants is immaterial, there being other grounds of

jurisdiction than that they are state officers. That the de

fendants in this case are also identical in capacity with the

defendants in Nixon v. Herndon, supra, would also seem to

settle this matter.

POINT VIII

The disfranchisement of plaintiff and other qualified Ne

groes disclosed by the record violates the 15th Amendment,

because citizens of one race were guaranteed by law the

right to vote in the statutory election involved in this case,

while plaintiff and other qualified Negroes were not.

That these are the facts is clear from the decisions of the

Texas appellate courts in Love v. Wilcox and White v. Lub

bock, supra, and from the facts within the judicial knowl

edge of this Court.

Construing the 15th Amendment, this Court has held:

“ If citizens of one race having certain qualifica

tions are permitted by law to vote, those of another

having the same qualifications must be.”

United States v. Reese

92 U. S. 214

25

POINT IX

This Court should decide all of the questions involved in

this case, especially those pertaining to the “inherent pow

er” and “private individuals” arguments, in order to pre

vent a multiplicity of suits and to prevent undue hardship

upon plaintiff and all other qualified Negroes in Texas.

It took plaintiff about three years to get a decision from

this Court in Nixon v. Herndon, supra, and it has taken him

about an equal period to get this case before this court.

The expense involved in getting cases before this Court is

no easy thing for Negroes to raise, who, as a matter of com

mon knowledge, are generally poor. The delay causes ir

reparable damage, in that more than one election goes by

before a decision can be had.

The reluctance of the Texas State Courts and of the low

er Federal Courts to go beyond the compelling literal lan

guage of this court in granting relief to Negroes from the

deprivation of their franchise rights seems clear from a

careful study of the cases deciding the question, all of

which have uniformly denied relief. In addition to the cas

es already referred to, the following may be cited:

Grigsby v. Harris

27 Fed (2nd) 942

Wiley v. Weber, et al

No. 432 in Equity, U. S. Dist. Ct. at San Antonio.

Love v. The City Democratic Committee

No. 438 in Equity, U. S. Dist.

Ct. at Houston.

“ I am not disturbed as to what the Supreme

Court of the United States in the omnipotence of its

judicial power may hold on the question in some fu

ture opinion, but I am not disposed to lead the way

to a change in its present views upon this question

by anticipating that they will be changed or modifi

ed in some future opinion.”

Chief Justice Pleasants, Concurring in

White v. Lubbock, supra

26

It is clear, we submit, that, if this court merely strikes

down the statute in this case, as it did in Nixon v. Herndon,

supra, and does not say in specific words that relief is

granted because neither defendants nor the State Demo

cratic Executive Committee, whether viewed as state offi

cers or private individuals, have “ inherent power” to

destroy the legal rights of plaintiff to vote in the statutory

election here involved, then plaintiff and all other qualified

Negro voters will be faced with these “ private individuals”

and “ inherent power” arguments anew, and will be forced

at great expense and delay, and with a multiplicity of suits,

to try these questions out all over again.

We trust that this Court may see fit to so decide these

questions as to prevent this undue hardship.

Conclusion

In State v. Meharg, 287 S. W. 670, a Texas Court of Civil

Appeals said:

“ Indeed, it is a matter of common knowledge in

this State that a Democratic primary election held

in accordance with our statutes is virtually decisive

of the question as to who shall be elected at the gen

eral election. In other words, barring certain ex

ceptions, a primary election is equivalent to a gen

eral election.”

Those to whom are entrusted legislative powers in the

State of Texas, therefore, feel that they owe no allegiance

or duty to the Negroes of the State, in that they have been

effectively excluded from participation in the primary elec

tions “held in accordance wth our statutes.”

As typical of what the fruits are, we mention what atti

tude these legislators have taken toward providing educa

tional opportunities for the Negro citizens of Texas. See

Title 49, Chapters 1 to 9, inclusive, of the Texas Revised

Civil Statutes.

27

Exclusively for the white youths of the State, the follow

ing educational institutions are provided:

1. A State University, which must and does have “ the

departments of a first-class university.”

2. An Agricultural and Mechanical College “ for in

struction in agriculture, the mechanical arts, and the

natural sciences connected therewith.”

3. John Tarleton Agricultural College, which “ shall

rank as a Junior Agricultural College.”

4. North Texas Junior Agricultural College.

5. College of Industrial Arts.

6. Texas Technological College.

7. School of Mines and Metallurgy.

8. Sam Houston State Teachers’ College.

9. North Texas State Teachers’ College.

10. Southwest Texas State Teachers’ College.

11. Texas College of Arts and Industries.

For Negro youth, there is provided the Prairie View State

Normal and Industrial College, and nothing more. In the

words of the statute (Art. 2642), it is limited to a “ four-

year college course of classical and scientific studies.” This

is the typical attitude of legislators whose election may not

be affected by the votes of the Negroes of the State, who

constitute about one-sixth of the total population.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, we pray that this

Honorable Court may here reverse the decisions of the Cir

cuit Court of Appeals and the District Court.

Respectfully submitted,

J. ALSTON ATKINS

CARTER W. WESLEY

Attorneys for Movants.

J. M. NABRIT, Jr.

NABRIT, ATKINS AND WESLEY

Of Counsel