Tampa Case Sets New Pace for Public School Desegregation in Deep South

Press Release

April 21, 1960

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Tampa Case Sets New Pace for Public School Desegregation in Deep South, 1960. a71ebca5-bc92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8e041dec-0470-46ff-b82c-afb0b1925d5f/tampa-case-sets-new-pace-for-public-school-desegregation-in-deep-south. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

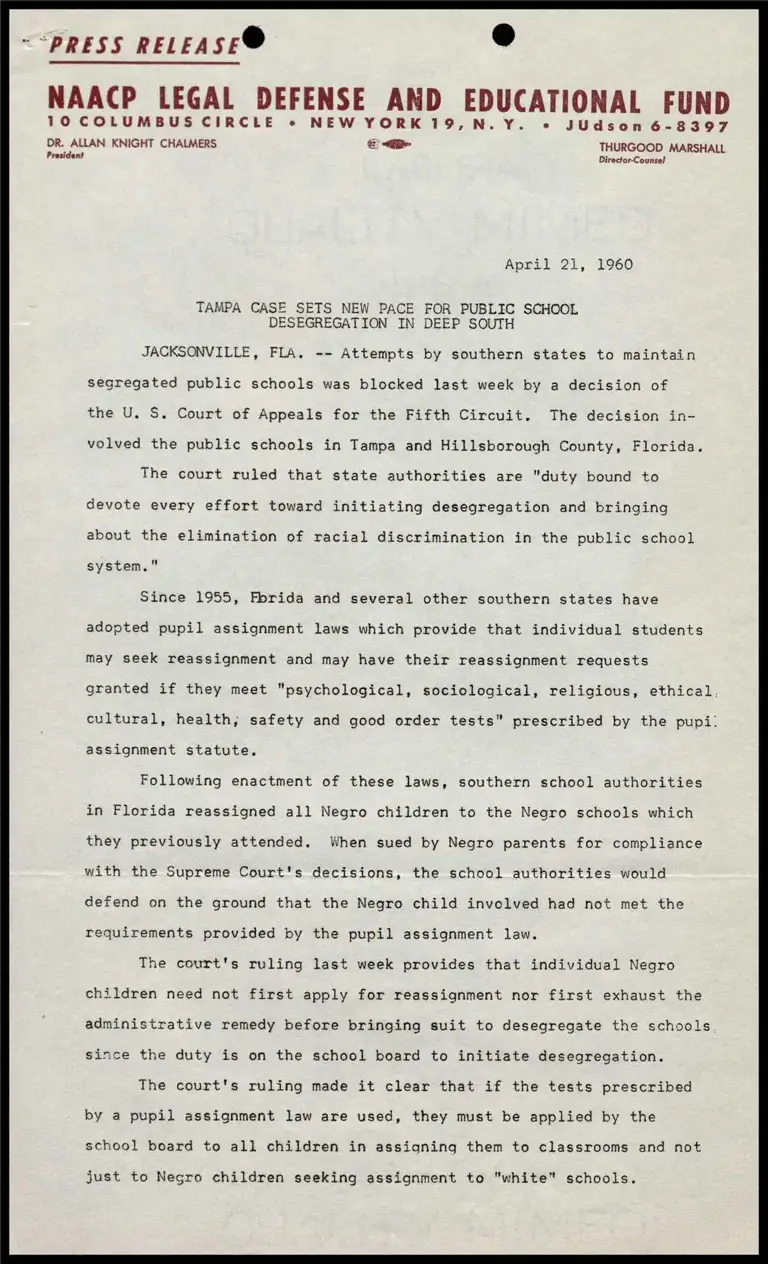

~<PRESS RELEASE® id

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE + NEW YORK 19,N.Y. © JUdson 6-8397

DR. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS <a THURGOOD MARSHALL President Director-Counsel

April 21, 1960

TAMPA CASE SETS NEW PACE FOR PUBLIC SCHOOL

DESEGREGATION IN DEEP SOUTH

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. -- Attempts by southern states to maintain

segregated public schools was blocked last week by a decision of

the U. S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. The decision in-

volved the public schools in Tampa and Hillsborough County, Florida.

The court ruled that state authorities are "duty bound to

devote every effort toward initiating desegregation and bringing

about the elimination of racial discrimination in the public school

system."

Since 1955, Fbrida and several other southern states have

adopted pupil assignment laws which provide that individual students

may seek reassignment and may have their reassignment requests

granted if they meet "psychological, sociological, religious, ethical

cultural, health; safety and good order tests” prescribed by the pupi:

assignment statute.

Following enactment of these laws, southern school authorities

in Florida reassigned all Negro children to the Negro schools which

they previously attended. When sued by Negro parents for compliance

with the Supreme Court's decisions, the school authorities would

defend on the ground that the Negro child involved had not met the

requirements provided by the pupil assignment law.

The court's ruling last week provides that individual Negro

children need not first apply for reassignment nor first exhaust the

administrative remedy before bringing suit to desegregate the schools

since the duty is on the school board to initiate desegregation.

The court's ruling made it clear that if the tests prescribed

by a pupil assignment law are used, they must be applied by the

school board to all children in assigning them to classrooms and not

just to Negro children seeking assignment to "white" schools.

-2-

The court further ruled that reassignment of all children to

the segregated schools which they had previously attended pursuant to

a pupil assignment law is nothing more than a continuance of the

segregation policy held unconstitutional.

The effect of the decision is to force school authorities to

come forward with a reasonable plan for full compliance with the

Supreme Court's decisions. The decision is binding not only on

federal courts in Florida, but also on federal courts in other

states comprising the Fifth Circuit, i.e., Georgia, Alabama, Louisians

Mississippi and Texas.

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund attorneys for the

Negro parents and their children were Francisco Rodriguez of Tampa,

and Constance Baker Motley and Thurgood Marshall of New York City.

Bae [oy =

April 21, 1960

RICHMOND, VA. -- The Greenville Municipal Airport discriminatiori

case was reversed yesterday by the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit and ordered reinstituted in the district court.

The case was dismissed on September 11, 1959, by Judge George Bell

Timmerman of the U. S. District Court for the Eastern District of

South Carolina,

The U. S. District Court will be required to hold a trial at

which the full facts of the segregation practices of the Greenville

airport may be placed upon the record.

The case originated in November, 1958, when a Negro air force

public relations man, Richard Henry, was not permitted to sit in the

white waiting room at the Greenville airport while waiting for a

flight to Detroit. Mr. Henry was returning to headquarters after

having covered an extensive air force maneuver near Greenville.

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund attorneys who repre-

sented Mr. Henry in the case were Lincoln C. Jenkins, Jr. of

Columbia, South Carolina, and Thurgood Marshall and Jack Greenberg of

New York City.

an30.=