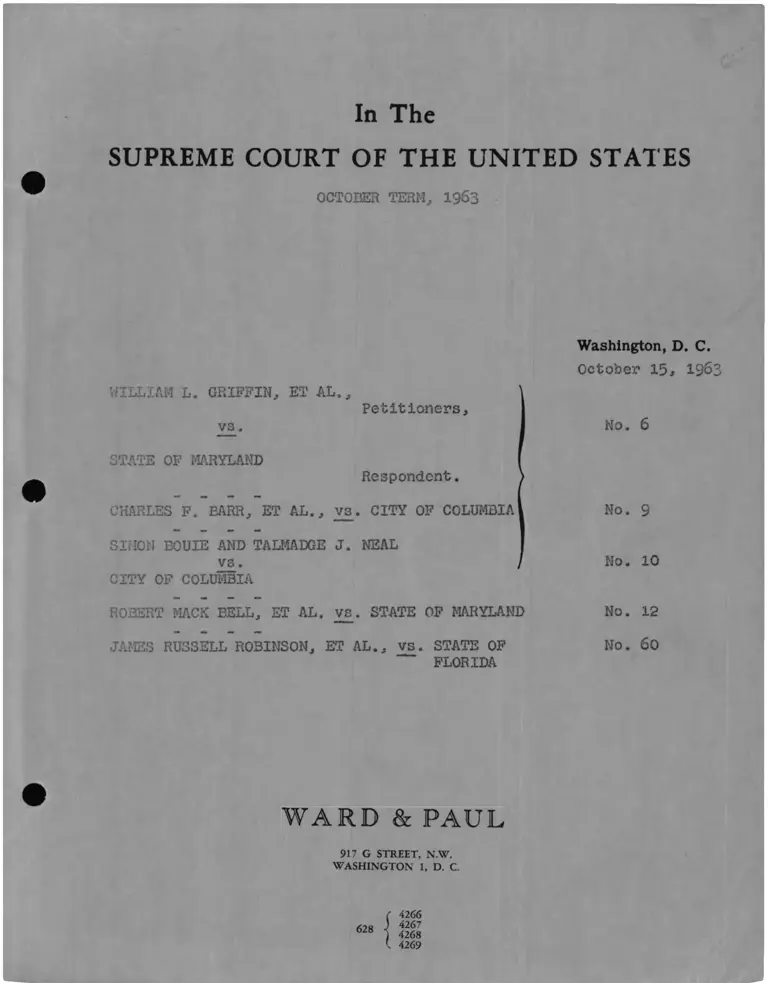

Griffin v. Maryland Transcript of Oral Argument

Public Court Documents

October 15, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Griffin v. Maryland Transcript of Oral Argument, 1963. f4991bbf-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8e09618c-cf20-4320-8129-d833d46f4527/griffin-v-maryland-transcript-of-oral-argument. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1963 •

WILLIAM L. GRIFFIN,

vs.

ET AL.,

Petitioners,

STATE OF MARYLAND

Respondent.

CHARLES F. BARR, ET AL., vs. CITY OF COLUMBIA

SIMON BOUIE AMD TALMADGE J. NEAL

vs.

CITY OF COLUMBIA

ROBERT MACK BELL, ET AL. V S . STATE OF MARYLAND

JAMES RUSSELL ROBINSON, ET AL., vs. STATE OF

FLORIDA

Washington, D. C.

October 15, 1963

No. 6

No. 9

No. 10

No. 12

No. 60

917 G STREET, N.W.

WASHINGTON 1, D. C.

c 4266

J 4267

) 4268

(. 4269

Supreme Court

ed C O N T E N T S

ao

BB

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF JAMES RUSSELL ROBINSON, ET. AL.

PETITIONERS,

By Alfred I. Hopkins

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA,

By George R. Georgieff

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF AMICUS CURIAE

By Mr. Spritzer

(AFTERNOON SESSION ~ p. 220)

ARGUMENT OF AMICUS CURIAE

By Mr. Spritzer (resumed)

REBUTTAL ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF THE STATE OF

MARYLAND, RESPONDENTS,

By Russell R. Reno, Assistant Attorney

General, State of Maryland

REBUTTAL ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF RESPONDENTS,

CITY OF COLUMBIA,

By John W. Sholenberger

REBUTTAL ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF THE STATE OF

FLORIDA, RESPONDENTS,

By George R. Georgieff, Assistant Attorney

• General, State of Florida

REBUTTAL ARGUMENT IN BEHALF OF PETITIONERS

By Mr. Jack Greenberg

PAGE

148

169

192

220

225

238

245

254

Mills #1 146

ed 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1963

WILLIAM L. GRIFFIN, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

vs.

STATE OF MARYLAND,

Respondent

CHARLES F. BARR, ET AL. ,

Petitioners,

vs.

CITY OF COLUMBIA,

Respondent

SIMON BOUIE AND TALMADGE J. NEAL,

Petitioners,

vs.

CITY OF COLUMBIA,

Respondent

ROBERT MACK BELL, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

vs.

STATE OF MARYLAND,

No. 6

No. 9

No. 10

No. 12

Respondent

x

147

-x

JAMES RUSSELL ROBINSON, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

VS M

STATE OF FLORIDA,

Respondent

No. 60

-x

Washington, D. C.

Tuesday, October 15, 1963

Oral argument in the above-entitled matters came on

for further hearing at 10:10 a.m.

PRESENT:

The Chief Justice, Earl Warren, and Associate Justices

Black, Douglas, Clark, Harlan, Brennan, Stewart, White and

Goldberg.

APPEARANCES:

148

P R O C E E D I N G S

The Chief Justice: No. 60, James Russell Robinson, et al.,

Appellants, versus the State of Florida.

The Clerk: Counsel are present.

The Chief Justice: Mr. Hopkins.

ARGUMENT ON BEHALF OF JAMES RUSSELL ROBINSON, ET AL.,

PETITIONERS,

By Mr. Alfred I. Hopkins

Mr. Hopkins. Mr. Chief Justice, may it please the Court,

this is an appeal from the Supreme Court of the State of Florida

which affirms certain criminal convictions by the Criminal

Court of Record in Fort Dade County, Florida, involving 13

appellants.

The adjudication by the trial court was had pursuant to

Section 509.141 of the Florida statutes. This chapter, or this

section, is set forth on page 8 of the appendix of appellants '

main brief.

To begin with an analysis of the statute, so we will know

what the case is about — the statute is a rather unwieldy

piece of legislation. It provides in essence, insofar as it

is germane to this case, that if any person enter a restaurant,

and if his presence or continued presence is, among other reasons,

in the opinion of the management thought to be detrimental to

the business, then the manager may request that this patron

leave the premises. If the patron declines to leave, the

149

manager may then call the police. If he still declines to

leave, he is deemed to be illegally on the preraises, and subject

to arrest and conviction for a misdemeanor.

The statute also provides for certain other criteria of

undesirability, such as persons being intoxicated, immoral, pro

fane, lewd or brawling. But then at the end it has this rather

generalized provision that any other person who in the opinion

of the management -- the presence of such a person would be

detrimental to the business, that person may be ejected from

the premises.

Justice Goldberg: Doesn’t it say the continued presence

— isn't that what it says? What is meant by the word at the

end "any longer to entertain". Does this statute at all fit

this case in any sense? Does this restaurant owner ever give

any accommodations to these particular people?

Mr’. Hopkins: Not in terms of food. They were seated.

If I may explain from the beginning —

Justice Goldberg: They took seats.

Mr. Hoplins: They took seats.

Justice Goldberg: The reason I ask you that question —

I don’t want to interfere with your argument — I thought that

this statute, if you read it in accordance with its words, is

obviously designed to cover a situation where a man might come

in and then having been a guest, admitted and invited, do some

thing or carry on in such a way that the owner decided that no

150

longer would they want him as a guest. And I did not believe

that under the facts of this case that they were ever really a

guest at the restaurant.

Am T. wrong in that, from the factual record?

Mr. Hopkins: I wish I had seen the point in the trial *

court. We did not raise that particular issue. But they were

never served any food at all. What happened was this.

The appellant, constituting 18 persons, and being both

Negroes and white persons in association with Negroes, entered

into a department store in Miami, Florida, called Shell City.

Shell City has 19 departments, one of which is a restaurant.

It serves the public, Negro and white alike, without discrimina

tion in 18 of the departments. But in the restaurant, it draws

the color bar.

Prior to the incident in question, which gave rise to

these criminal prosecutions, there had been two other attempted

sit-in demonstrations. They are mentioned very briefly in the

record and the consequences of them are not set forth in the

record.

On this particular day, which was in August 1960, the

appellants walked into the restaurant, in this department store

sat down at about five tables. They were not served when they

sat down. They waited for service. They waited for about

a half hour.

At the end of the half hour period, one of the appellants

151

got up from the table, walked over to a Mr. George McKelvey.

Mr. McKelvey is the Vice President of Shell City, and he is

also the General Manager of the store.

The appellant asked Mr. McKelvey could he be served. Mr.

McKelvey said no. The appellant asked why. He said, "I have

nothing further to say to you."

At that point the appellant went back and joined the group

and sat down.

Then Mr. McKelvey got on the phone and called the police

and told them what was happening in his restaurant.

About 10 minutes later a policeman arrived, Sergeant John

Suggs, of the Miami Police force. He then, with Mr. McKelvey,

walked to each of the table. Mr. McKelvey again made his

request to the appellant that they leave. They declined to

leave. Whereupon, Sergeant Suggs took them all into custody.

Now, going back a step — while they were in the restaurant,

there were other persons, white persons, seated there and who

were being served. That is clear from the record.

The manager of the restaurant testified at the trial that

the reason for his refusal of service was the fact that the

appellants were Negroes, or white persons in association with

Negroes, and that in his opinion would make it detrimental to

any longer entertain them.

So the source, the substance, the foundation of his reason

for refusing to serve them was their color, or their association

152

with persons of color.

There is no evidence in the record that any of the appellants

were engaged in any boisterous or noisy conduct. There is no

evidence that they comported themselves in any fashion which

would have included them in the other specific provisions of

Section 509.151. They were peaceful at all times. There is no

evidence in the record that there was any hostile crowd gathered

around the group of appellants. There is no situation that

would have erupted into violence, no indication of any kind

of situation such as that .

The facts are essentially undisputed.

The appellants put on no evidence of their own. However,

cross-examining Mr. McKelvey and his associate, Mr. Warren

Williams, also a Vice President of Shellas City certain additional

facts were adduced which I think should lead to a reversal of

the judgments below.

Mr. Williams, when he was questioned, was asked why the

appellants were refused service.

Justice Black: What page is that?

Mr. Hopkins: On page 28, Your Honor, between pages 28 to 30.

I wanted to point out Mr. Williams' statement of the custom

prevailing in Dade County, Florida, at that time. That was

August of 1960, some three years and two months ago.

He indicated not once but on four different occasions that

there was a custom in Dade County not to serve Negro and white

153

people in the same restaurant. And he indicated and said chat

this custom forced him to do what he did.

If I may read some extracts from the record.

At the top of page 29, Mr. Williams answered the question

of counsel. First the question.

"Do you know why these people were refused service at

the restaurant"?

"Answer. Well basically,it is the policy of Shell‘s City

not to serve colored people in our restaurant."

"Why?"

"Answer. That is based upon the customs, the habits,

and what we believe to be the desire of the majority of the

white people in this County."

Again, toward the bottom on page 29, in talking about why

they discriminate, Mr. Williams again answers, "Well,it goes

back to what is the custom, that is, the tradition of what is

basically observed in Dade County would be the bottom of it.”

Justice Black: What is the precise point for which you

present this language?

Mr. Hopkins: At a later point in my argument, I wanted

to make this position, Your Honor — that we have unconcra-

dicted in the record a statement by the State's own witness that

there is a custom prevalent — was ac that time, of the white

majority in Dade County which compelled the manager of the

restaurant to segregate.

154

Justice Blade: You mean that if the sentiment of the

community can only he met by taking that course, that the

Constitution would make that State action?

Mr. Hopkins: I base my position, Your Honor, on the dictum

of Just Bradley in the majority opinion of the civil rights

cases. I grant you it is only a dictum. But he did say it.

If I may read from his statement set forth on page 27 of

•t.appellants! main brief, Mr. Justice Bradley said, "Civil rights

such as are guaranteed by the Constitution against State aggres

sion cannot be impaired by the wrongful acts of individuals un

supported by State authority in the shape of lav;, customs, or

judicial or executive proceedings."

Justice Black: I am asking this for my information. Has

this Court ever had occasion to distinguish between custom of

the people as distinguished from the custom of the law enforce

ment officers in the State, in long, continued legal practice —

such as we had in the Tennessee case.

Mr. Hopkins: Your Honor, I have not found such a case.

There is a question in my mind as to what Justice Bradley meant,

what the majority of the court meant. It is also a fact that

one of the early civil rights acts, RS1983, uses the word

"custom or law.”

Justice Black: You are relying on that?

Mr. Hopkins: I am suggesting that that statute repeats

the same language, and that may have been in the mind of the

155

framers of the 14th Amendment.

Justice Black: But that doesn't have any relevance in

your argument here insofar as you want co construe the 14th

Amendment as saying that the custom of the people, or the pre

vailing sentiment of the people shall be accepted as the lav;

of the State.

Mr. Hopkins: I am suggesting that it may well have been,

the adopters, or the framers of the 14th Amendment, when they

used the word "State" were thinking not simply of the agents

of the people, that is, legislators, the administrators, the

judges, but may well have been thinking of the body politic

itself.

Por example — and examples are rare in this field — but

in the case of Neal versus Delaware, the court was dealing

with a provision of the constitution of the State of Delaware

where the people of the State of Delaware had purported to

disenfranchise or limit the franchise to white people. This

is by way of analogy. But there was a state constitutional

provision adopted by the people of the State. And the court

stated — the Supreme Court stated that that condition was

void, because it was repugnant to the 15th Amendment to the

Federal Constitution.

What I am getting at is this. It seems to me clear that

the people of the state, if they act formally and politically,

act in a political fashion through the legalism of a constitutional

156

provision, can constitute the state.

Justice Black: What percentage of the people had that

custom and sentiment? How would you find that out?

Mr. Hopkins: In this case v/e have the evidence. Mr.

Williams stated that it was the custom of the majority of the

people.

Justice Black: That is a rather slender reed, is it not,

to rest a constitutional decision on — as to whether the

people — as part of their legal system, that it has to be used

to satisfy state lav;.

Mr. Hopkins: Mr. Justice Frankfurter indicated in Terry

and Adams, and again a dictum, that custom could have the force

of lav; — in fact, it is stronger than lav;.

Justice Black: I think he wrote to that effect in a case

in Tennessee, with reference to the tax, where they had been

taxing a railroad — I have forgotten the name. But that was

in line with our cases with reference to the jury, where the

courts function so long in one way that you can say that that

has become, some might say, the custom of the lav; enforcement

officers and the state officials, and others might say its the

custom of the people.

Mr. Hopkins: Your Honor, I do not bottom my case entirely

on that ground. But I do suggest it to the Court as a possible

way of resolving this case.

As I say, authority seems to be slim or negligible. But I

157

do feel that I should bring that idea across to the Court,

inasmuch as it is in the record, and no contradiction by any

of the State's witnesses.

Justice Black: I was asking because I am familiar with

those cases. I am not criticizing you. Don't misunderstand.(2) fIs

Mills

ao 1 (2)

fls. ed Mr. Hopkins: A further statement of the facts, insofar as

they involve the Florida restaurant and hotel licensing statute.

Florida has, like many jurisdictions, elaborate regulations and

statutory provisions governing the licensing of restaurants.

Relevant provisions of our statute, Chapter 509., are set forth

in the appendix to the appellant’s main brief.

The statute provides that no one may operate a restaurant

unless he has a license. The statute provides for the establish

ment of the Hotel and Restaurant Commission, which issues the

licenses. This Commission is set up to encourage the public

health, safety, and welfare -- safeguard, rather, the public

health, safety, and welfare of the people of the State of

Florida. No restaurant may be built vintil its building plans

have first been approved

Justice Stewart: I suppose that is true of a house there,

too, isn’t it -- a home?

Mr. Hopkins: Yes, it is true.

Justice Stewart: You cannot build a house without a build

ing permit.

Mr. Hopkins: My argument will be, or I will make it now,

that the licensing requirements -- and this infusion of State

activity into private enterprise -- would, in my view, be

limited to places of public accommodation, places where signif

icant community interests are affected. I would make the same

kind of argument in this regard as counsel yesterday made with

158

ao 2 159

regard to the limit to which Shelley v. Kraemer should be

extended. I would not suggest that Shelley v. Kraemer be

extended to the privacy or intimacy of a home. I think the

Court has the power, and certainly has in many other .fields of

constitutional law, to limit the scope of certain of its doc

trines; and I suggest that the licensing argument, which I will

use as a brief label — there is no reason to extend it to the

home. It can be limited to places of public accommodation, or

situations where significant public interests are affected.

Justice Goldberg: Well, by no stretch of the imagination

could a home be conceived of in the terms of this regulatory

scheme which is designed, is it not, expressly for public food

service, --

Mr. Hopkins: That's right.

Justice Goldberg: -- and that is where it comes to bear.

Mr. Hopkins: Mr. Justice Stewart was suggesting what about

all the licensing laws, building permit laws.

Justice Stewart: And zoning laws, inspection laws, as

to plumbing and electricity and everything else. I presume they

have that in Florida. They do in most of the States.

Mr. Hopkins: Yes, sir. But, as I say, I would limit the

application of the argument, or not extend it, to situations

of actual privacy.

I would like to elaborate a little more on the statute,

to indicate its scope, and indicate the extent to which the

160

State has involved itself in licensing restaurants.

They regulate fire escapes., exits, plumbing, ventilation,

all the various safety precautions. They provide that no

employee may be employed unless he has a health certificate.

The regulations which were adopted by the Commission pursuant

to the statute go into minute detail, down to how much detergent

must be put into a deep sink to properly cleanse pots and pans.

So much for health and safety.

But the statute does not seem to stop there. In fact, it

does not stop there.

The statute talks about the welfare of the people.

Interestingly, in Section 509.032, on page 7 of the appendix,

it states:

"The Commissioners shall be responsible for ascer

taining that no establishment licensed by this Commission

shall engage in any misleading advertising or unethical

practices as defined by this chapter, and all other laws

now in force or which may hereafter be enacted."

Similar to that provision, there is another provision

on page 23 of the appendix that licenses may be revoked if

gambling is carried on on the premises.

In addition, the regulations provide for achievement

rating cards which are to be posted on the premises.

Justice Goldberg: What does that mean? "A" Restaurant,

"B" Restaurant, "C" Restaurant -- something like that?

ao 4 l6l

Mr. Hopkins: It is a big card that has points given for

their compliance with various health and safety provisions. I

can show the Court an example of it.

Justice Black: Does your argument include the regulation

of a business or activity by the State to be treated for con

stitutional purposes as though it were an actual State operation?

Mr. Hopkins: That would be my argument, Your Honor.

Justice Black: Then regulations for the home -- many of

those you mentioned are with reference to the home -- I have

difficulty in distinguishing, constitutionally speaking, between

ownership by a person and ownership by persons.

Mr. Hopkins: Let me, if I may, go back to the case of

Public Utilities Commission v. Pollack. That was the case of

the radios playing in the busses and street cars here in the

District of Columbia.

The Court, in the first part of its Opinion, stated that

the Capitol Transit System, because of its regulation by the

Public Utilities Commission, in placing these radios, and act

ing in the way it did, acted in a governmental capacity; and

that First Amendment rights or obligations were brought into play.

The Court said that it was not mere that there was a fran

chise granted -- the Court stated that this was an enterprise

regulated by a State agency. The Court went on to say that it

deemed as particularly significant the fact that the Transit

Company went to the Public Utilities Commission to get a ruling

ao 5 162

on this particular service.

Here I think if we had gone to the Florida Hotel Commis

sion 1 or a rulings we would nave gotten the same answer neces

sarily as we got from the Florida Supreme Court -- namely,

that restaurant owners may discriminate.

But the important thing about the Pollack case, it seems

to me, is that the Court has said that a regulated enterprise,

VJhen ic acts in a field of significant public importance,

public transportation, takes on characteristics of State

acoion, or there is, to use the language of the Burton case,

an interdependence between the State and private enterprise.

A similar case was Baldwin v. Morgan, a Fifth Circuit

case, which dealt with the Terminal Building in Birmingham,

a railroad terminal building. And the Fifth Circuit made the

same kind of approach: that here is a facility serving a

public need, regulated by the City, and with this interdependence

they could not discriminate against Negroes in the seating

facilities.

I would suggest that if Capital Transit Company or some

other public street railway system were to institute Jim Crow

sc cups on its streetcars, that that would be unconstitutional.

I suggest --

Juscice Stewart: In both of those cases I suggest there

may be a difference, two differences. First, you are dealing

with a monopoly, a regulated monopoly. And secondly,you are

163

dealing with instrumentalities of commerce; isn’t that true?

Mr. Hopkins: To meet the monopoly situation, the Court

said that Pollack in Pollack, that the fact that it had a

franchise, presumably was given monopolistic powers, was unim

portant. But even if the Court should consider it important,

then it would seem that the monopoly situation would lead to an

absurd result.

If you say that a monopoly, because it is a monopoly, can

not discriminate, but 100 or 1500 restaurants, because they are

not monopolies, can discriminate, then you get a very strange

result.

Justice Stewart: My contention was only this: If you

have only one mass transportation monopoly, then this is the

only way people can ride who need to use mass transportation.

If you had 1,500 or 2,000 restaurants in Dade County, Florida,

presumably some of them will choose to serve only white people,

some of them may choose to serve only Negro customers, some may

choose to serve both.

Mr. Hopkins: But where the need is there, the need can

be as great and significant to the Negro who wants to eat in

Shell's City or some other variety or department store, as the

need for an equally important service or commodity such as

transportation.

I do not see that food, in the middle of the day when you

are hungry, is any less important than transportation. And the

ao 7 164

fact that there was only one enterprise that provides the com

modity should not, in my mind, make a constitutional difference.

You have to have hundreds of restaurants in the community.

The one transportation system can serve the whole community,

can serve the purpose.

That is essentially the argument as to the licensing

problem.

Justice Black: Your argument boils down, as I understand

it, to this: that since restaurants are licensed -- you leave

them in private ownership -- but the government has just as much

power to regulate them as it would have if the government ex

ercised governmental authority, as some nations do as to own

all the property and decide how people shall use it, and with

whom they shall associate.

Mr. Hopkins: They are already regulated in a great sense.

Justice Black: You would strike down the distinction,

as I understand it, under that argument. The mere fact that

they are regulated gives the government a right to do these

other things that you say, when it would not have that if they

were not regulated.

Mr. Hopkins: I think it is the scope of the regulation,

which is vast here in this case.because, in addition to what I

have mentioned, the government has visitation powers, to inspect

Justice Black: They can do that in any hotel, can't they?

Mr. Hopkins: They can. But I suggest — •

ao 8

Justice Black: Many people live in hotels and motels.

165

They are Just as strictly regulated as the others. Would it

be held by the Constitution — does that compel them to accept

people into their hotel rooms they do not want., for whatever

reason?

Mr. Hopkins: I think when the State has gone this far.,

and indicated this much of a concern and this much of a need

for the State in adopting this kind of a comprehensive licens

ing statute., that we have a situation which is analogous to the

Burton problem. Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority. The

City needed that restaurant, otherwise its parking lot financing

would have been in great jeopardy.

Justice Black: Which one is that?

Mr. Hopkins: Burton v. the Wilmington Parking Authority.

Justice Black: Who owned that property?

Mr. Hopkins: The property was owned by the City. But I

do not think that is the only distinction. I think there was

a question of a public need, the public being dependent upon

this particular facility,

I submit that the two can be related that the Court

talked in terms of the extent — the nonobvious ways in which

the State has become involved in private enterprise, the degree

to which one is interdependent with the other, a kind of

partnership, if you will.

Justice Black: VJe have adopted in this nation, rightly

ao 9 166

or wrongly^ some people think one, some the other -- a system

of private ownership of property. And you would obliterate

that where the Government regulates it at all.

Mr. Hopkins: Only where there is a significant comrtvunity

interest at stake. I do not believe it is necessary to extend

the rule, extend the doctrine to private situations. I think

the Court can deal with this --

Justice Black: But you refer to private — what we call

private ownership is ownership by somebody other than the

Government. That is what is meant by the private system, is

it not?

Mr. Hopkins: At that point I could bring up Marsh v.

Alabama.

Justice Black: Marsh v. Alabama has many other things in

connection with it that your situation does not.

Mr. Hopkins: The Capital Transit Company was, I assume,

a private enterprise. Yet in its operation in this particular

respect it took on characteristics of a governmental activity.

The Court went to great pains to go into that.

Justice Black: Suppose the Government could go so far

where it would be a governmental activity, in terms of contracts

and so on, where the Government was actually doing it, and pur

porting to put it in somebody else's hand is that the argu

ment?

Mr. Hopkins: My argument is that this degree of interde-

ao 10 167

rbSfls

pendence --

Justice Black: — has "been reached here.

Mr. Hopkins: -- has been reached here. I think, as a

matter of constitutional adjudication that this would not pose

the impossible job for the Court in drawing lines. A classic

example would be the State regulation of interstate commerce —

how much is too much; when does a burden become undue. It is

a difficult, paradoxical problem, every time that problem arises.

But the Court meets it, and I believe the Court can meet it in

this kind of situation.

#3 168

rb-1 That same approach, juridical approach in the field of

public accommodations tilth regard to a licensing law, I think

should be applied with regard to the Shelly & Kraemer doctrine,

which I have not had time to talk about here this morning, but

I adopt the same views as my colleagues from the NA ACP — that

we do not have to get that far that we get into the club or the

private home; that we deal with the scope of the indignity,

the scope of the indignity, and the'scope of the humiliation

visited upon upon a great mass of part of our public, the Negro

citizens — indignity and humiliation which is visited upon them

every day in every community in the South, and hundreds of

restaurants and in hotels„

I think it is that — the scope of the problem should

indicate where a line must be drawn today.

In Burton vs. Wilmington Parking Authority the Court indicated

that there was a problem of examining the facts of each case.

And the multitude of facts that existed in the Eurton case led

to a conclusion of state action.

I suggest that the multitude of involvements of the state

in the restaurants and the community at large, and of the Nation,

if you will, require a finding of significant state action in this

case, substantial as to bring the action within the proscription

of the Fourteenth Amendment. And I do not believe that hypo

thetical situations of the home need concern us.

Thank you.

169

The Chief Justice: Hr. C-eorgieff.

ARGUMENT ON BEHA IE OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA

BY GEORGE R. GEORGIEFF

Mr. Georgieff; Mr. Chief Justice, may it please the Court,

I think by the time this day Is over you will have had quite

enough of these cases*

So I will be very limited in my reply.

First, I would like to clear away several things. Basically

I agree with the statement of facts that gave rise to the action

that you are about to review here — with several exceptions.

First, you will find nothing in this record to indicate

that Shell's City's Restaurant was licensed by any political

subdivision of the State of Florida. There is not a trace of

it anywhere.

You will also find —

Justice Goldberg: What do you mean by that? Are we to

assume, since you have generally applicable statutes which

require licensing, that this concern was operating without a

license?

Mr. Georgieff: No. Eut we are not free to assume that it

was .

Justice Goldberg: Isn't the logical presumption to be that

people comply with the laws of your state in licensing?

Mr. Georgieff : I agree that that would be a logical pre

sumption. But in any case we are confronted with the record that

“3 170

v/e have here. It would have beer a simple matter to establish

that there were or were not.

Justice Goldberg: Was that an Issue that was ever contro

verted in the litigation, that this was a licensed establishment?

Mr. Georgieff; No, sir.

Justice Goldberg: Well then, why should we take time to

consider that?

Mr. Georgieff; it is a factor in the case, Just as are the

situations brought up by counsel here.

Justice Goldberg: I don't follow you. Are you saying it

was not licensed?

Mr. Georgieff: I cannot say that, since I don't know, sir.

Justice Goldberg: Then you are not saying that your laws

do not apply, your licensing do not apply?

I«jr 0 Georgieff: I will say this. I assume that they were.

And if they do apply, and I am sure they do, the chances are

Shell's City was a licensed establishment.

Justice Goldberg: Well, it undoubtedly was, wasn't it?

Mr. Georgieff : I assume it was.

Sergeant Suggs, when he went around the tables, with Mr.

MeKeIvey and Mr. Williams, both of whom were vice presidents and

one a manager of the restaurant, after these people were asked to

leave by Mr. McKeivey at each table, Sergeant Suggs asked them

or suggested that they should leave before anything else followed.

When they declined, it was then that he arrested them for the

171

commission of this act. which resulted in the criminal action

being brought against them.

So in that respect it is somewhat similar to the case you

heard yesterday in which the police declined to do anything and

required the individual to go down and make his complaint before

the magistrates' court.

Now, there has been a question raised here about whether

customs of a community should form the basis for your conclusion

that this amounts to state action here, and if it does, you

should then turn around and condemn what happened in Florida in

this case.

Now, I think that there is a fair reason why you cannot

equate customs to state action in this case.

You cannot impose your sanctions against the people of Dade

County if they feel that they prefer generally not to associate

in restaurants with Negroes — the white people, that is.

Nov;, I do not for one moment suggest that either Mr.

McKelvey or Mr. Williams, whoever it happens co be, are free to

determine for this Court what the general belief, feeling, or

custom is in Dade County. There are over a million people in

metropolitan Dade County right now,

I hesitate to think that Mr. Williams is qualified to pass

on this. But even if he is, you could only impose sanctions

based upon this custom if the government of Dade County or Florida

or the City of Miami were to abdicate any duty that it had under

5

172

your constitution and our own, for that matter, based upon

this custom,,

If they found, because of what people believe they thought,

that they would not desire to turn around and arrest anybody for

failing to serve a Negro, and if that became their policy, then

I would expect that you would strike it down, based upon the

custom as developed by the act, failure to act of the law enforce

ment or the government of the state*

Justice Goldberg: Generally, suppose.your statute, carrying

out your argument ~~ suppose your statute had provided, as It

does, that the restaurant shall be licensed as a public food

service establishment; but the section had said, "Recognizing

the custom against service to I&groes, no restaurant owner shall

be required to serve colored people." "Shall be required." Would

.you think that would ba a valid statute?

Mr. Georgieff : No, sir .

Justice Goldberg: Well, then, suppose the statute was

changed and it said "No restaurant shall be required to serve

an undesirable person which shall include" if he was of the

opinion "colored people". What about that?

Mr. Georgieff: It is a little different.

Justice Goldberg: Much different? Your first answer would

encompass that, would it not?

Mr, Georgieff: I am on tenterhooks, Mr, Justice Goldberg,

You see, when you add the affirmative mention of a class of

•b~6 173

people or a creed — take your pick* it doesn't matter — then

you begin to evidence by your legislative acts and opinion some

official opinion to which you can direct a complaint.

Justice Goldberg: So your answer would have to be in the

second instance that it would be invalid.

Mr. Georgieff: More nearly invalid than valid — if you

make that mention.

Justice Goldberg: Now take the third one. Suppose then

you do not define who the undesirable class is., but you apply it

in your criminal case to what the owner has defined. That is

your case here.

Mr. Georgieff: Yes, sir. What was your question?

Justice Goldberg: Well, isn't it in practical effect the

same thing?

Mr. Georgieff: No, sir.

Justice Goldberg: Aren't you recognizing by law the custom

by permitting the owner then through the law to enforce the custom?

Mr. Georgieff: It is not in my view, sir.

Justice Goldberg: Why not?

Mr. Georgieff: I will tell you why, sir„ If we do away

with 509.141 and wipe it off the books, you are nevertheless

confronted either with common law trespass, or the statute we have.

Justice Goldberg: Common law trespass — i3 that criminal

trespass in your state?

Mr. Georgieff: Yes. Now, in those cases an owner of private

174

property exercises whatever he pleased as his reason to evict

someone from his premises . If you leave it to him — •

Justice Goldberg: Let me go back there. Are you saying in

your state you could be indicted for common lav/ trespass

indicted? I am not talking about civil actIon.

Mr. Georgieff : Well, no, sir, I will tell you why.

Indictments invariably are returned in capital cases.

Justice Goldberg: Can you be arrested and convicted for

the offense of "common law trespass" in your state?

Mr* Georgieff: Yes.

Justice Goldberg: Pardon?

Mr. Georgieff: I'm sorry. I said yes, sir.

Justice Goldberg: You did say that.

Mr. Georgieff: Yes, sir.

Now, assuming that that is so, and it is, if you allow a man

who has a farm, a home, take your pick, whatever it is, he has

some private property — if you allow him to determine who he shall

have on his premises, and if he shall have them, and for how long,

and for any reason, then does it matter that you take a section and

create it, and you codify that which you already have extended to

hirr, as, let's say, your majesty of the law, so that he doesn*t

have to take it into his own hands — I fail to see any difference.

I agree depending upon how you approach it — if you go backwards

from your illustrations, you might come to the conclusion that

if it does not make any difference, since custom is the basis ~~

rb~8 175

# 4 f Is

that "basically we go forward from poor beginnings to more

sophisticated ones * And if we say to the people who own business

establishments "If you feel" *— and who is better qualified,

knowing his clientele "that the continued presence of someone

here is going to be offensive to your business and will prove

detrimental," and you allow it to an ordinary citizen in his

home, I do not see any difference between the two.

It is one that you extend as a matter of right and law for

many years, centuries, perhaps, and now one that you simply draw

forth in specific terms in relation to business establishments.

176

MILLS(4)

jt-1

I don't know, sir, that that answers your question, but

I hope it does.

Mow, I would like to first, in Marsh vs. Alabama — that

seems to be one in which there was almost a complete abdication.

The people were denied the right to voice their expression as

guaranteed by the First Amendment.

Now, I do not know what the velocity of this court was

when you said what you did in Marsh. But I mentioned chat part

of it might have been a real fear that if you did not reverse

Marsh, that it would be a simple matter for the states to turn

over all their communities to private individuals, and they

would rule them as they like, by company towns.

Now, if that is real, it might foe a reason, I don't know.

But I would like to dwell on Shelley as the basis for the re

quest on the part of these appellants that you should imple

ment what you did there in this case.

Now, there has been so much written about Shelley vs.

Kraemer that I suppose it ill behooves me to speak of it. But

in any case, I know the one thing that you did not say about

Shelley — you did not say that the person who sold to Shelley

had to sell to him. All you did say was once Shelley earned

the lawful right entitled to that property, it was not proper,

under the Constitution of the United States, for the State of

Missouri to deprive him of the right to the anjoyraent of that

property.

177

Nov;, he had earned it by a free sale by the party who

had owned it, and he merely sought to enjoy that right.

If these people who came into Shell's City's Restaurant

had been successful in securing services from the management —

Justice Black: Did they have a contract with him?

Mr. Georgieff: They had nothing, sir. Nov;, had they

been able to secure services from them i:n exchange for their

money, you would have the situation that you do in Kraeraer.

If he sold them the food and then said, "Look, wait a minute,

you cannot eat this food in here. You can take it, but you

cannot eac it in here, because we do not allow that" — based

on custom — then you would have the comparable situation as

reflect in Shelley. But you do not have that here. All you

have is somebody who says "l want to guarantee, not only chat

I can contract, but that when I do, it will be as I wish it

to be."

Justice Goldberg: Doesn't your statute authorize the

restaurant owner, after he has sold the food, to change his

mind and give him back his money and say, "Get out"?

Mr. Georgieff: Yes, sir, if something occurs.

Justice Goldberg: Well, what if he just decides in his

opinion, he changes his mind, thinks it will be detrimental

to his business in his opinion. Wouldn't the statute author

ize under those circumstances?

Mr. Georgieff: Well, sir, I am at a loss now. We do not

173

have any decision which explains this statute.

Justice Goldberg: But the statute on its face would

purport to do that.

Mr. Georgieff: Well, there are some who say it would. I

am not certain it would. I assume that the most I can say in

honesty, not departing from my position or doing harm to that

of the appellants, is that if he were to put the people back

in the position that they were before they came in, that is to

say gave them back their money, and there were a genuine basis

upon which he could conclude that they were detrimental, I

take it chat is possible under the statutes.

Justice Goldberg: That is a question which bothers me.

If you look at your statute, which I find in Appendix VIII of

the brief for appellant — if criminal information is filed,

and the charge is that you were intoxicated, can you defend

against that by showing you were not?

Mr. Georgieff: If I should assume so.

Justice Goldberg: How can you defend against this par

ticular criminal information?

Mr. Georgieff: That i3 not a defense that was ever raised

or a point that was raised at any stage of the proceedings in

this case, Your Honor.

Justice Goldberg: Well, what would you think?

Mr. Georgieff: What would I think? You would have to

demonstrate, I suppose — well, as a matter of fact I dare say

179

that by the provisions of the statute, the very statute,

assuming that it is correctly quoted here — I do not have any

reason to believe it is not — if you leave it to management,

as you do in ordinary cases of trespass, there is no way. How

do you explain to somebody who does not want you in his home

chat you belong there? You don't.

Justice Goldberg: He says, "Get out".

Mr. Georgieff: That's right. And based upon —

Justice Goldberg: But here you are trying a person on a

criminal charge for an opinion of undesirability which pre

sumably in this record was never articulated.

Mr. Georgieff: We do that every day in an ordinary tres

pass, sir. That results in criminal action. It doesn't always,

but it may.

Justice Goldberg: I don't follow you here. You said in

your original criminal action of trespass you try him because

the owner has said, "Get out", and that is the basis of the

trespass charge. Here that is not the basis. Here the basis

is the opinion of the proprietor that he is not desirable. Is

that correct?

Mr. Georgieff: Is that not the basis of the private

owners order to get out — his own opinion that he doesn’t v/ant

him there? I do not mean to question Your Honor. Don't mis

understand. But I do not see how we can separate the two.

Isn't it opinion that generates in order to leave?

180

5 However arbitrary?

Justice Stewart: The basis is not the "Get out", the

basis is the refusal to leave after being told to get out.

Mr. Georgieff: Of course it is. Mo question about it.

And it is in 823 as well. You become a trespasser after

notice, as opposed to one who simply enters on a property.

Justice Stewart: I suppose it is conceivable chat in a

defense for a trespass charge you could say "He did not tell

me to get out" or "While he said ic, he really did not mean

it" this is at least possible.

Mr. Georgieff: Perhaps it is, Your Honor.

Nov/, as I say, putting these two side by side you simply

have an open legislative announcement as to one, whereas to

the other it has been something that has developed over the

years.

Nov/, if I, both as a private homeowner and as a restaurant

operator, decide as to the same person, one, that I do not want

him in my house once he is in there, and I tell him to leave

and I no longer want him in my restaurant and I tell him to

leave, I fail to see the difference.

Now, if there is, perhaps I can go further towards answer

ing your question, Mr. Justice Goldberg.

Justice Goldberg: General, what puzzles me about your

whole statute — if your construction is correct, then why the

necessity for all the prior language in the statute, about

l8l

intoxication and other practices — because your theory

then would be that the owner may just say, "Get out" for no

reason whatsoever, and never express it, and the statute

would govern. Then in effect you are imputing through your

legislature a concept — having enacted a statute which de

fines specific reasons against which a man can defend in a

criminal case, you are now imputing a broad provision that

for any reason, disregarding anything — and then my question

is how you can ever defend against the criminal intoxication

charge by showing you are not intoxicated, because then it

could be said that the owner in his opinion did not want you

just because you were you.

In other words, I am raising this question, which may

not have been raised. It is raised in the vagueness argument

— not exactly in these terms. Is it not to be read logically

that the undesirable person is a person of the character, of

the people who are specified — not just undesirable at large.

Mien you have a series of proscriptions in a statute which

defines why a person is to be excluded — and then you have a

general one of undesirability, isn't the only way this

could be read in the criminal statute is undesirable in the

context of the prior definition?

Mr. Georgieff: I do not think so, sir.

Justice Black: How did the court read it?

Mr. Georgieff: They did not read it at all. They simply

182

said on its face it w a 3 valid *

Justice Black: It was never under discussion?

Mr. Georgieff: No, sir.

Justice White: Did they affirm the conviction?

Mr. Georgieff: They did, sir. Inasmuch as there was no

question as to evidence, they stated, and I think you will

find in their opinion, it is in the appendix, that since the

only point raised was the validity of 509.141, that they con-

eluded on its face it was totally color-blind.

Now, I do not know what went into their deliberations.

But they did not discuss the matters chat I brought up here.

Now, if I may, Mr. Justice Goldberg —

Justice Harlan: Don't we have to take the construction

of the statute by the Florida court as a matter of state lav;

-- that this statute means a man can exclude anybody for any

reason he wants?

Mr. Georgieff: That is correct.

Justice Harlan: Then we are bound by that construction.

Mr. Georgieff: I would think you would.

If I may, Mr. Justice Goldberg, in answer to your question

— it is by nature — by the nature of the property that the

statute breaks down into four sections. And in the fourth one

you get co the section which says "and any other person".

Nov;, I would assume that in ordinary circumstances, wher

ever you might be, that these enumerated areas or situations

183

8 would probably provide a valid basis for anybody to act in

defense of themselves, their property, and so forth.

Nov;, when you get to the other, the area where it is

left to the individual, it is because it is private property

that they have to extend to him some latitude.

If the only reasons you could were for those enumerated,

there would be enough paper in the world to write out all the

reasons. You have got to leave something to an individual, as

you do in ordinary trespass, as you do in other situations.

If you do not, then you will wind up in a helpless morass. You

either enumerate beyond belief, or you leave it totally with

out mention.

(5) Now, I do not pretend to know why they bothered to say

it the way they did in the legislature, but I assume they had

a valid reason. And so far of course it has not been changed

except by an insubstantial alteration by the 1961 legislature.

But it seems to me that if you do not allow some latitude

for an individual to determine what, in his view, is going to

be detrimental, even if it be this, however vague you may

consider it to be, then there isn't anything chat you can

give. If he is not drunk, if he is not brawling, if he is

not offensive or abusive, then theoretically you cannot put

him out even if you are offended by it, and even though you

know it will be detrimental.

Justice Goldberg: The language is much broader than that.

184

"indulge in any language or conduct" which shall disturb the

peace and so on.

Mr. Georgieff: I understand. There are parts of it

which are quite broad. I do not know how specific we could

be and still have anything that was workable.

Justice Goldberg: Has this been construed by your Supreme

Court on its last phase of it and on this case?

Mr. Georgieff: No, sir. And then only on its face.

There has been no construction of it as such.

I might add, though, that these individuals, whatever we

may personally think about the conduct that resulted — one

thing they knew for certain, they were neither of the enumera-

tive things. I do not think there is any doubt about that.

The fact is that they were planning to do this very thing,

which is .apart from what we are discussing here.

But now the question of whether this is tate action.

There has been the hue and cry raised that they were in

formed against by the office of the State Attorney, that they

were sentenced by a judge in the criminal court of record,

that the district court of appeal acted on it, the Florida

Supreme Court acted on it, and the Attorney General is now a

part of it — though by lav; we are required to be.

Any criminal action in the State of Florida, as is prob

ably true in most of the jurisdictions, including the District

of Columbia, is brought by some prosecuting arm of the Executive

135

Branch. I fail to see how this type of action makes it state

action.

I further fail to see how Sergeant Suggs, when he arrested

them, after a refusal to leave, in the face of this legislation,

was doing anything but what he was required to do as a part of

his duties as a law enforcement official.

Now, if he is given the ability, the duty, the responsi

bility, the choice to decide whether a given act is or is not,

then we do not need this court or any other court, because

our police officers can decide what is a crime, then we do not

need any courts. And before too much longer, if they become

proficient at it, we won’t need any laws.

But the point is the legislation, as.' it exists, until you

have had a chance to review and pass upon it, is valid. And

we have got to presume that if you refuse to leave after you

have been asked in accordance with the statute, and this was

in the presence of a police officer who asked them, and even

suggested that they leave before he arrested them, then they

have committed those acts which, if they result in a conviction,

constitute a misdemeanor of which they ultimately were found

guilty by the trier of facts.

Now, custom is one thing; police action is another.

Any crime that is committed results in some type of

prosecution, I would hope.

Nov;, admittedly there are times when choices are made as

136

to which way to go. But that is not done by law enforcement;

that is done by prosecution and/or the court, which is the

proper place for it to repose.

But it is idle to say that because all of these circum

stances which led to the case findings its way here, that

becomes state action. The state did not advocate anything.

They had a statute which simply says that people are going to

be allowed to exercise the right over their property, and

therefore who flies into the face of this request after it has

been in accordance therewith is guilty if it results in a

trial and a finding of guilt.

Nov;, there was a reluctance yesterday on the part of some

people to enter into the question of whether this approach is

religion. I am not so reluctant. I do not see how you can

avoid it.

Let us assume, if you will, that in a given ceremony in

a Jewish synagogue you have four Catholics come in carrying

crucifixes who sit themselves in the front row. This is an

open and public indicia of a difference of creed which is of

fensive to the Jewish populace and to the Rabai. What can he

do?

Well, I suppose he could ask them to leave. But if they

decline, what could he do? Could he force them to leave?

Force them to get out? Could he call the police. I think you

should be free to

187

12 Nov;, the difference between creed and color is absolutely

nothing, if you look at the Constitution that assures the

guarantees. And yet here we do not have anything different,

not in the slightest.

If you say to me that these people cannot be discrimin

ated against by private citizens who hold themselves out to

serve the public, I say to you that there isn't any reason why

the Rabai should not be permitted to call upon lav; enforcement.

Justice Douglas: Of course, there you have the First

Amendment. Up to now, the businesses have not been included

in the First Amendment.

Mr. Georgieff: That is true, sir.

Well, it is not all as I would have it, you understand. I

realize that. And yet it seems to me chat when you get to the

area of the differences between creed, condition of servitude,

color and so on, I cannot bring myself to believe that we can

effectively separate it when it suits us and bind it when it

doesn't.

Nov;, let's take the situation —

Justice Black: It was argued yesterday that this did

violate their rights under the First Amendment, that they had

a right to go into the store and stay there whether they wanted

them to go or stay or not, in order that they might advocate

their views about their opposition to segregation.

Mr. Georgieff: Well, Your Honor, I was out of the room

188

13 for sometime. It is possible that I missed that argument, Mr.

Justice Black. But I think they do have that right. I chink

you have said that many times over.

Justice Black: That gets down to this question: Do they

have a right to appeal on the First Amendment — do you also

have the right to go to a place where there is a valid lav;,

assuming it is valid, that you could not go, to interfere

with somebody else who is exercising the right of free speech?

Do you have the right to go there to do it, or must you go

somewhere else?

Mr. Georgieff: Well, sir, they have the right to go into

Shell’s City Restaurant. But once the management determined

that they no longer wanted them in there, they did not have

the right to remain.

Justice Black: That is what 1 am talking about. You have

no right to be at a place. Does the First Amendment guarantee

people to go to places where under the lav; they cannot other

wise go on the grounds that they have got to be allowed to

advocate their views wherever they please, whenever they please

and however they please?

Mr. Georgieff: Mot in my view, sir.

I might add, which I did mean to implement — by saying

there wasn’t any evidence there was a license in this case.

But I have set out in my brief the fact that automobiles are

probably the most licensed thing in the state, and probably

189

14 in most states. I would like someone to tell me why it be

comes different when you apply it to an automobile. If you

are going to use that as your criteria — now, again, as I

say, we cannot separate it when it suits us for our argument

and then bind it together when it doesn't. If you are going

to say that licensing requirements form a satisfactory basis

on which you should conclude that there is sufficient 3tate

control to make it state action, then I submit that every car

that is driven in the state of Florida drives as a result of

state action. Every home that is occupied by anybody. We

have got a homestead exemption law that says that if I be

come a pauper, default on every debt, that they can do every

thing they like to me, but they cannot take my home from me.

Now, that is a recognition by the state that they are going

to assure my castle to me.

Now, if they go that far, which is even further than

what they have done here by a long shot, does it not follow

that they have a right to tell me who I shall and who I shall

not have in my home? Or that anybody may come in that suits

his fancy?

Now, I will agree, and there is a similarity. I think we

will all agree that someone has a right to come to my door and

ask of me what he will, i may either reply or tell him to go

on about his business — just as in Shell's City here. They

came upon the premises, sought to do business with these

190

15 people. They were declined the right to do so, and they were

asked to leave. It is not at all different from what I might

do in my home, or you, or anybody else.

Now, if we extend that on the theory of the licensing re

quirement, I submit that there is no end to it. You can go on

ad infinitum.

Nov;, I do not pose a threat — that is foolish. I would

not suggest these things are going to happen tomorrow or the

next day or any day after that. But if you are going to put

it within the legal framework that they say you should use as

one of the bases, then I say don't separate it as to the

others which you know will be there one day.

Justice Goldberg: General, is it clear from this record,

as I look it, and as the government contends, that they were

never cold why they should leave?

Mr. Georgieff: They were not told why. But the statute

contemplates that they need not be told why. It only requires

that if management had the opinion, that is all is necessary.

Nov;, I hasten to add, if Your Honors please, that the

point raised by the brief of Amicus is one which is totally

foreign to this case.

Justice Goldberg: Would you say a word about that before

you conclude your argument?

Mr. Georgieff: I was reserving some time for that.

Justice Goldberg: Any time that fits your argument.

191

16 Mr. Georgieff: Based upon the positions which have been

presented by counsel for the appellant here, and the total

non-applicability of Shelley, certainly not even Shelley vs.

Stengel, which gives people a right to contract, under the

Court of Appeals decision, it seems to me that unless you are

ready to determine that an ordinary citizen in the pursuit of

his rights — now, he doesnlt have property rights, he has

personal rights to handle this property the way it suits him.

Unless you are ready to determine, and determine that these

rights shall no longer be his own — and unless you are ready

to upset the civil rights cases, I think that the only result

can be that you affirm the Florida Supreme court and deny this

appeal.

(6)

# 6

rb-1 The Chief Justice: Mr, Spritzer,

ARGUMENT BY AMICUS CURIAE

BY MR. SPRITZER

Mr. Spritzer,* Mr. Chief Justice, may it please Your Honors,

in addressing myself to the five cases which are before the

Court, I shall attempt to first set forth the general approach

which we follow, one which is common to all of the cases, I then

propose, if Your Honors please, to discuss the Florida case,

which stands in our view somewhat apart from the others, because

its statute is unique.

Then I would like to turn to the specific arguments which

were made in the South Carolina and Maryland cases, which from

the standpoint of our analysis at least we may consider somewhat

as a group.

After setting forth the arguments I have outlined, I shall

also attempt to state briefly why I think the points that we

argue were adequately comprehended by the arguments made in the

state courts, and why in any event they are here.

let me say in that connection at the outset that even if

this Court should conclude, in one or more of these cases, that

the point which is argued in the amicus brief was not sufficiently

presented, not presented with sufficient explicitness in the state

courts, it does not follow from that, or would not follow from

that that the issue drops out of the case, as was suggested

yesterday.

192

rb-2 193

In the Avent case, which was here last term, the case

was obviously within the jurisdiction of this Court because

various constitutional arguments were raised and duly preserved.

However, the petitioner in that case did not raise at any

stage of the litigation an argument based on an allegation that

the City of Durham, which was the place where he was convicted,

had an ordinance requiring segregation„

Indeed, he had made no attempt to prove the existence cf

such an ordinance.

Nonetheless, this Court having jurisdiction of the case

concluded that that issue ought to be considered, It vacated

the judgment, accordingly, and remanded the case to the Supreme

Court of North Carolina in the light of its decision in one of

the companion cases.

Having jurisdiction of these cases, this Court has it within

its power, under the certiorari jurisdiction, tl make such

disposition as the justice of the case may require.

Let me also say at the outset that our brief does not address

itself, and I shall not in oral argument address myself, to the

broad and undeniable very serious and important question whether

there should be a re-definition of the concept of state action

for purposes of administering the provisions of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

I need hardly to dwell upon the rule so often emphasized

by the Court that it will not ordinarily reach broad constitu~

~3 194

tional issues if more limited principles are disposited.

Particularly so, I take it, where those more limited principles

are themselves well settled*

We "believe that these cases fal under that precept.

In this connection, I would alsd say that we are mindful

of the fact that the President is seeking at this very time, and

that the Congress is considering legislation — of course national

in scope — which, if it were adopted would be directed at the

very problems which underlie this kind of litigation*

Before leaving these preliminaries, I would also remind

the Court that the Solicitor General has expressed his readiness

in his brief, should the Court, contrary to our present expecta

tion, find that the grounds of reversal which we urge are not

dispositive — his readiness to address himself further at the

suggestion of the Court to the broader constitutional issues

which have been moved*

Now, in each of these cases, of course, as the Court has

heard at length, a group of Negro citizens, in some instances

accompanied by white sympathizers, unsuccessfully sought service

at a private place of business open generally to the public.

In all of the cases, as v ie read these records, the petitioners

were Invitees. In none of the cases had they received any warning

before coming on the premises that they were not to enter.

Yet in four of the cases, excluding only Florida, we deal

with statutes which on their face condemn nothing more than entry

rb-4 195

after warning not to enter.

Justice Goldberg: What about the Maryland statute that

also says cross over?

Mr* Spritzer: I do not read it as adding anything* and

neither did the Maryland courts* The Maryland courts in these

cases decided the issue before it solely on the basis that these

people had entered without notice., but that the statute covered

remaining after notice to leave as well as entering after notice

not to enter,

I shall attempt to develop that further when I get to that

phase. Your HonorP

Now, the Florida statute of course does proscribe remaining

after notice to leave. It imposes such a duty, however, only

when the entrant has behaved objectionably* by engaging in

specified types of misconduct, or when his presence is found

detrimental to business.

As has already been stated by the parties to that case* the

Florida appellants were never told that their exclusion was based

upon any one of the limited statutory grounds which alone would

their act of remaining an offense — even though they made

repeated inquiry as to why they were being directed to leave.

Broadly* then* we shall argue on all of these cases that

there was a denial of due process* a lacic of adequate warning

from the statute, that the conduct subsequently charged as unlaw

ful was in fact a violation of the state criminal law.

-5

196

We are not, of course, questioning the role of the state

Supreme Court in interpreting state statutes0 We are dealing

with the constitutional right of fair notice or fair warning.

Justice Goldberg; Does that mean that in all future cases

you would regard fair warning to he given., hut that in this

series of cases fair warning is not given? 13 that the necessary

import of your argument?

Mr. Spritzer: I think a different question would arise

if the statute had previously been interpreted. We do not have

that question here, because these statutes, as I shall develop,

were interpreted for the first time in what we regard as this

novel fashion in the cases now here.

Justice Goldberg: Where do you find that distinction drawn

in the decisions of this Court? The reason I mention that is

you cite Amsterdam a few pages prior to that, his note on vague

ness, and he says quite the contrary, summarizing the Court's

decision. He says "if the Supreme Court in passing on these

penal statutes has invariably allowed them the benefit of what

ever clarifying gloss state courts may have had in the course

of litigation in the very case at bar," citing a number of

decisions in this Court. And that seems to me to reach the whole

basis of your argument, doesn't it?

Mr, Spritzer; If adequate notice in the constitutional

sense were provided by the conviction rather than by the statute,

then the concept of fair notice to my mind would disappear. I

rb~6

would reject that completely*

Justice Goldberg: You disagree with that analysis of the

cases ?

Mr, Spritzer; I do. I am not speaking in reference —

with reference to the particular cases which he cites, "because

I do not know the context from which that comes. But I certainly

"believe that if a statute on its face fails fairly to give any

warning, that it would "be a destruction of the whole concept

of protection which the due process clause has been set to

guarantee, to say that that notice is adequately provided when

the judge — •

Justice Goldberg: What about National Dairy?

Mr, Spritzer: Well, National Dairy for one thing involved

the requirement of scienter, specific knowledge by the defendant.

There is no basis for saving that there was any scienter in this

case. So I think that falls into a quite different category*

I would lilce to make this general observation before getting

further into the specifics of these cases,, as to why we think it

is eminently proper to read these statutes with a scrutinizing

eye and to apply here with purposeful strictness the requirement

of fair notice.

In the first place of course we are dealing with criminal

statutes. These are not simply acts relating to the laws of

property. And this Court has said in Kline vs. Prink Dairy —

I do not know whether this would fit into Mr, Amsterdam's analysis

197

198

that the Fourteenth Amendment imposes upon the state an

obligation to frame its criminal statute so that those to

whom they are addressed may know precisely what standard of

conduct is required.

The state is obliged, in its statute.

oecor.dly, we are not dealing with conduct which by any

stretch of the imagination is inherently or morally wrong. The

people involved in these cases were casing what is no more than

common bread in the life of the community.

In uhe Barr case, the testimony of one of the defendants

I think epitomizes the feeling that one gets from a reading of

these records . He was on the stand, explaining what happened

when he sought service at the drugstore counter. He says that

a white lady was occupying the adjoining place at the counter.

And uhen he goes on — I will use his words — "She sat there

and began eating just as if I was a human being sitting beside

here, which I was,"

We agree with Professor Frimes1 observation that in applying

the rule against vagueness or overbroadness, something should

depend on the moral quality of the conduct.

A third reason why the statutes should be carefully scrutinized

in their application is the petitioners here wer engaging in a

peaceful and orderly protest against discrimination.

As I**. Justice Harlan observed in his opinion in the. Garner

case, such a demonstration is as much a part of the free trade in*

rb-8

Ideas as is verbal expression.

Justice Iferlan: Of course you have to recognise that was

in the context of a situation where the record shows that the

demonstration was going on with the owner's consent,

Mr. Spritzer; Yes. I would add, nonetheless — I do not

think the force of the point is destroyed by Your Honor's correct

observation — that my point here is that a vague statute is a

threat to the exercise of such First Amendment rights also.

Because if the citizen cannot be sure when his conduct falls

within a statutory ban,more than likely he will timidly force

his right to express what the lav; does not or cannot prevent.

There is another side I think to that coin — through the

overzealous policeman — this is an invitation to the abuse of

power or to discriminatory enforcement. I think it apparent

that the misuse of authority to arrest or to order an exclusion

or to order dispersion may effectively deny the exercise of

First Amendment rights, whatever the ultimate disposition of the

matter should it go to court.

Through all of these reasons, then, we urge that the statutes

involved in these cases should be sustained in their application

only if they give clear forewarning that the conduct ultimately

charged was of a prohibitive kind.

Let me turn, then, without further delay to the specifics

of the Florida case„

The counsel in that case have already referred to the statute.

199

200

It is set forth also In the government's brief, beginning at

page 18.

I would like to take a moment to stress once again the

structure of that statute.

The first numbered paragraph provides in substance that

the proprietor or the manager of a hotel, ressturant, apartment

house, motor court, and various other establishments, shall have

the right to remove a guest who is intoxicated, immoral, profane,

lewed, brawling; also one who engages in language calculated

to disturb the peace and comfort of other patrons, or to damage

the reputation of the establishment.

And then finally the management is authorized to require

the departure of one who in its opinion is a person whom it would

be detrimental to his business to serve.

Now, I think by plain, I would say, necessary implication

this statute says that there is no way to remove one who is not

obnoxious in his conduct and whose presence is detrimental to

the operation of the business»

It does not confer the right to exclude a patron of an

inn or a restaurant for any reasonc If that were the purpose,

there would have been no reason for the statute,, There were

already criminal trespass laws in the State of Florida.

We do not think it authorizes, for example, exclusion for

reasons of racial prejudice.

Justice Black: Suppose that conclusion was made because the

rt>-10

owner thought it would be detrimental to his business, in his

opinion.

Mr. Spritzer: Then I thinlc that it would meet the terms

of the statutes, yes, sir.

Nov;, it was not — well, let me pause a minute before getting

to the information.

As the Court has heard, and I v/ould emphasize again, the

invitees of this establishment, the eighteeen Negroes and whites

who walked in, were permitted to sit down — and who sat there

for some half hour, were not told at any point, that they made

repeated inquiries, as to why they were being excluded. It was

stated for the first time by the management that his reason for