State Board of Education v. Anthony Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

August 3, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. State Board of Education v. Anthony Appellants' Brief, 1973. 9c38ad57-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8e190074-061d-41df-8706-9da9e3392bfc/state-board-of-education-v-anthony-appellants-brief. Accessed January 30, 2026.

Copied!

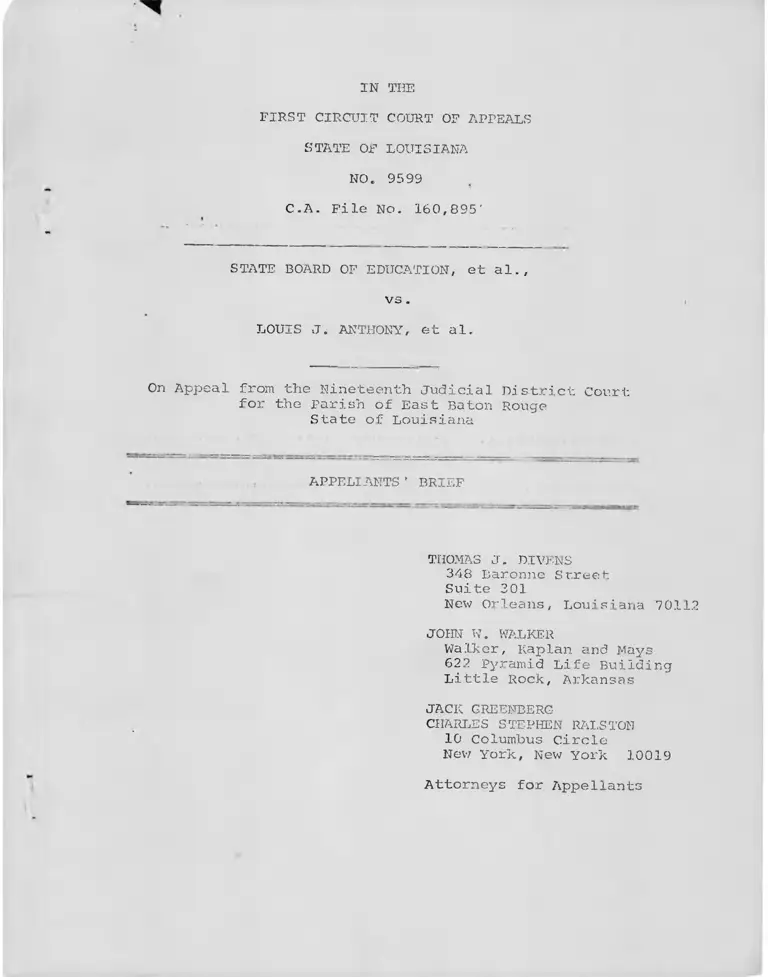

IN THE

FIRST CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS

STATE OF LOUISIANA

NO. 9599

C .A . File No. 160,895'

STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

vs.

LOUIS J. ANTHONY, et al.

On Appeal from the Nineteenth Judicial District Court

for the Parish of East Baton Rouge

State of Louisiana

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

THOMAS J. DIVENS 348 Baronne Street Suite 301

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

JOHN W. WALKER

Walker, Kaplan and Nays

622 pyramid Life Building

Little Rock, Arkansas

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

INDEX

Page.

ISSUES ------------------------------------------------ 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE------------ "------------------- 2

DISCUSSION OF THE DECISION BELOW --------------------- 6

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENTS------------------------------- 10

ARGUMENT

I. DUE PROCESS REQUIRES A HEARING BEFORE

SUSPENSION EXCEPT IN EXCEPTIONAL SITUATIONS.

IN SUCH EXCEPTIONAL CASES, THE HEARING

MUST BE HELD AS SOON AS PRACTICABLE AFTER

SUSPENSION------------------------------------- 11

II. LOUISIANA REVISED STATUTE 17:1301 ET SEQ.

IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL ON ITS FACE AND AS

APPLIED IN THAT IT IS VAGUE AND OVERBRO/AD,

IN VIOLATION OF DUE PROCESS AS EMBODIED IN

THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT ---------------------- 19

III. THE CONDUCT OF APPELLANTS IS CONSTITUTIONALLY

PROTECTED UNDER THE FIRST AND FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENTS TO THE CONSTITUTION OF THE

UNITED STATES -------------------------------- 28

TV. AN INJUNCTION ISSUE WHICH LIMITS THE

EXERCISE OF FIRST AMENDMENT' RIGHTS MUST BE

COUCHED IN THE NARROWEST TERMS WHICH WILL

ACCOMPLISH THE OBJECTIVES SOUGHT TO BE

ACHIEVED. THE INJUNCTION ISSUED BY THE

TRIAL COURT VIOLATES THE FIRST AMENDMENT

IN THAT IT IS AN ILLEGAL PRIOR RESTRAINT

ON THE EXERCISE OF FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHTS------ 32

CONCLUSION--------------------------------------------- 36

Certificate of Service ------------------------------ 37

Page

Table of Cases:

Armstrong v. Manzo, 380 U.S. 545 (1945) ---------- 12, 13

Barnes v. Merritt, 376 F.2d 8 (5th Cir. 1967) -------- 22

Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535 (1971)'-------------------13

Bishop v. Inhabitants of Rowley, 43 N.E. 191 (1896)--- 23

Burnside v. Byars, 363 F.2d 744 (5th Cir. 1966)---- 19, 28

Cafeteria and Restaurant Workers Union v. McElroy,

367 U.S. 886 (1961) -------------------------------- 13

Cole v. Young, 351 U.S. 536 (1956) ------------------- 13

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U.S. 385

(1926) --------------------------------------------- 20

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965) ---------------- 26

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U.S. 278 (1961) 21

Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F.2d

150 (5th Cir. 1961) ----------------- 10, 12, 14, 17, 33

Dunn v. Tyler Independent School District, 460 F.2d 137

(5th Cir. 1972) 15

Esteban v. Central Missouri State College, 277 F. Supp.

649 (W.D. Mo. 1967) ----------------------------- 12, 31

Fuentes v. Shevin, 407 U.S. 67 (1972) ---------------- 13

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County,

377 U.S. 218 (1964) --------------------------------- 34

Hammond v. South Carolina State College, 272 F. Supp.

947 (D.S.C. 1967) ----------------------------------- 19

Holmes v. New York City Housing Authority, 398 F.2d

262 (1968) ------------------------------------------ 22

Hornsby v. Allen, 326 F.2d 605 (1964) ---------------- 22

In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967) ------------------------ 28

ii

Page

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, ^

341 U.S. 123 (1951) ------------------------------- 23

Jones v. State Board of Education, 279 F- Supp. 190 ^

(M.D. Tenn. 1968) -------------------------------

Knight v. State Board of Education, 200 F. Supp. 174 ^

(M.D. Tenn. 1961) -----------------------------------12

t

Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471 (1972) 36

NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Flowers, 377 U.S. 288 (1964)-- 3_>

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) 25

Payne v. Board of Regents of University of Texas,

355 F. Supp. 199 (W.D. Texas 1972), affj_d, 474

F . 2d 1397 (5th Cir. 1973) --------------------------- 36

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez,

U#S . ____, 41 U.S.L.W. 4407 (March 21, 1973)---- 34

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960)------------- 24, 35

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U.S. 87 (1965) 26

Small Company v. American Sugar Refinery Co., 267 ^

U.S. 233 (1925) ------------------------------------- 21

Smith v. California, 361 U.S. 147 (1959) 35

Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp., 395 U.S. 337

(1969) ---------------------------------------------- 1

Soglin v. Kauffman, 295 F. Supp. 978 (1968) 19, 21

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 (1958) --------------- 24

Stricklin v. Regents of the University of Wisconsin,

297 F. Supp. 416 (W.D. Wis. 1965) ----------- 16, 17, 32

Sullivan v. Houston Independent School District,

307 F. Supp. 1328 (S.D. Texas 1969) ---------------- 31

Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School

District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969) ------------------- 25, 28

m

Page

United States v. Harriss, 347 U.S. 612 (1954)--------- 20

West Virginia State Board v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624

(1943) ---------------------------------------------- 28

Williams v. Dade County School Board,- 441 F.2d 299

(5th 'Cir. 1971) -------------------------------------

Wood v. Wright, 334 F.2d 369 (5th Cir. 1964) 15

Zanders v. Louisiana State Board ot Lducation,

281 F. Supp. 747 (1968)---------------------- 10/ 14/ 33

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions:

United States Constitution, First Amendment --------- passim

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment----- passim

Louisiana Revised Statutes 17:3101 et seq. 1, 8, 10, 19

Other Authorities:

Seavey, Dismissal of Students: Due Process,

70 Harv. L. Rev. 1406 ------------------------------- 33

iv

ISSUES

1. (a) Whether the action of University officials

in suspending appellants from Southern University for alleged

acts of misconduct without the benefit of a hearing or a prior

opportunity to be heard is violative of the due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States?

(b) Whether the trial court is the proper forum

to decide questions involving discipline at a tax-supported

University?

2. (a) Can Louisiana Revised Statutes 17.3101 et sect.,

which is aimed at the regulation of disruptive conduct, be

applied to punish students who engage in protest on the campus

of a tax-supported University in the absence of regulations

which prohibit the conduct engaged in?

(b) Whether Louisiana Revised Statutes 17:3101

et se_q. is so vague and overbroad as to violate the First

and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United

States?

3. Whether appellants' conduct is constitutionally

protected under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the

Constitution of the United States?

4. Whether the injunction issued by the trial court is

so vague and overbroad that it violates the First and Four

teenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United States?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This action commenced during the fall semester of 1972,

when the Southern University campus in Eaton Rouge, Louisiana

became the scene of massive protests and boycotting of classes

The protests were spearheaded by an unstructured organization

known as Students United." Students United organized in

late September, and by mid-October, acting through some of its

members, presented a list of grievances to Dr. G. Leon

Netterville, President, Southern University.

Among the grievances presented was a request for the

resignation of Dr. Netterville and other administrators at

the University. When University officials had not acted upon

the grievances, the students took their grievances to the

State Board of Education and to Governor Edwin Edwards. The

Governor, University officials, and members of the State Board

of Education, all conceded the merit of some of the student

1/complaints.

After hearing the grievances of the students, Governor

Edwards appointed a committee to investigate them. The

students met with the committee on several occasions from

late October until early November, 1972 on the campus of

Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

1/ Testimony of Gov. Edwards: "I consistently said privately

and publicly that most of their grievances were entirely in

order---" (Transcript, p. 2141.)

2

When these meetings failed to resolve their grievances,

the protest activities were escalated and the students' demand

for the resignation of Dr. Netterville became one of the

primary demands. The protest activities continued until

November 8, 1972 and by that date there was an almost total

boycott of classes.

Students were urged to attend meetings in the two

gymnasiums on campus. These meetings were attended by

students, faculty, and administrators, including

Dr. Netterville. At these meetings student leaders, especially

the defendants, exhorted the other participants not to resort

2to violence or other forms of disorderly conduct.

The method of effectuating the boycott was for a student

or group of students to enter into a classroom and ask the

instructor for permission to address the class, and only

after his permission to address the class was granted, did

the spokesman explain to the students the purposes for the

boycott and request that they join in the boycott. It should

2/ Q. What were the instructions that the group

gave...?

A. First of all, we all had this thing about love

of our people and respect for our people and

if we were going to achieve anything we had to

respect one anothers and that was...the basic

thing that we preached.... (Tr. pp. 839-840.)

3

be noted that this was the accepted method of notifying

students of "pep rallies" and other University functions,

as there was no public address system which could be used to

3/reach students in the various buildings on campus.

... On’or about November 9, 1972 Dr. Netterville sent letters

to each of the appellants notifying them that they had been

suspended from the University. Not all of the appellants

received the letters. This letter of suspension advised the

appellants that they had been suspended and that the suspensions

could be appealed to the State Board of Education within

30 days. The letter failed to specify the charges pending

against them, the person or persons making the charges, or

the time and place of a hearing.

On or about November 13, 1972 Dr. Netterville sent to

the appellants letters which reinstated them and set aside

3/ Q. Is it unusual for a student or a group of

students to come into your classroom and

ask for permission to address your class?

A. If someone comes and asks my permission,

of course, it is acceptable... We

always do that.

Q. Has it ever occurred?... Has anyone ever

come to your classroom and asked for

permission to speak to the class?

A. Yes, several times, almost every day students

came and asked permission from the teacher and

if they want to address to the class and talk

to an individual student or to the group of

students, they can do so... (Tr. pp. 461-462.)

4

the earlier suspension on the condition that the alleged

disruptions would cease. Appellants, in reliance on this

second letter, returned to campus. The boycott of classes

continued.

t

On or about November 16, 1972, at approximately 4:00 a.m.,

several of the appellants were arrested by police officers

of the East Baton Rouge Parish Sheriff's offices. At

approximately 9:00 a.m. on November 16, 1972 a group of

students, including several of the appellants, went to the

office of Dr. Netterville to secure his assistance in obtaining

the release of those students who had been arrested. The

meeting ended with the calling out of the National Guard and

police officers from the East Baton Rouge Sheriff's office.

Two students were killed later in the day.

The University was closed on the 16th of November, 1972,

and remained closed to the students until January 3, 1973.

On or about December 29, 1972 appellees, through

Dr. Netterville, applied to the district court for a

temporary restraining order and preliminary and permanent

injunctions against appellants, to restrain and enjoin them

from entry onto the campus of Southern University in Baton

Rouge, Louisiana. During the period when the University

was closed members of the staff and faculty met and decided

5

that the appellants were responsible for the disruptions

which occurred at the school and named them as defendants

in this action.

Appellants were not afforded a. hearing prior to their

suspensions or to being ruled into court, and have not to

this day been afforded such a hearing.

DISCUSSION OF THE DECISION BELOW

(1) The district court below erred in finding that

the University need not meet the requirements of due process

prior to filing this action. In his written reasons for

judgment of February 6, 1973, the trial judge totally dis

regarded the constitutional rights of appellants to a hearing

prior to suspension as established by the long line of cases

dealing with student suspensions and expulsions. The trial

court said:

4/ Q. And what is your understanding of the reason

they are under suspension. . . .?

A. For . . . persuading students to boycott classes

and to have unauthorized meetings and so forth.

Q. . . . I am ashing you, would punish them because

they refuse to acquiesce in your position on that

one point?

A. If severing them from the University to solve

the problem was punishing them if that what

you mean by punishing. . . .

Q. Yes?

A. Yes. (Tr. p. 1303.)

6

"While this Court is of the opinion that

the later letter did not completely lift

the suspensions and merely conditioned the

students' readmittance, the Court must agree

that the University failed to meet the

requirements of due process established by

Dixon and the other federal cases dealing with

student suspension or expulsions. And if the

’sole question before the Court was restricted

to the issue of the validity of the defendants'

dismissal from Southern University, the court

would agree." (Written Reason for Judgment,

P- 5. )

As stated earlier, the students were first suspended

on November 9, 1972 and later reinstated on November 13, 1972.

They were not, otherwise, notified that their reinstatement had

been revoked until they were ruled into court. Prior to being

ruled into court, appellants were under the impression that

they were students of Southern University. Thus, the first

opportunity which appellants had to challenge their suspensions

was when they appeared in court.

(2) The trial court erred in finding that the conduct

of appellants was disruptive and not constitutionally protected.

The record in this case is devoid of any testimony that any one

of the appellants committed any act which could reasonably be

construed as being intimidating, abusive, or unlawful. In

reaching his conclusion that appellants had, in fact, committed

disruptive acts which intimidated others, the court relied on

a movie which evidently had been viewed by the trial judge:

7

"Any person who saw the movie 'The Godfather

would readily understand that words do not

always have to convey actual threats to

produce the effect of intimidation, but

often a mere suggestion accompanied by the

■knowledge on the part of the listener that

means to produce a fearful result are present

will induce fear and cause intimidation."

There is no precedent for imposing such strenuous

sanctions on students when the basis of same is the trial

judge's appraisal and appreciation of a movie. Appellants

urge that the trial judge can not substitute his appreciation

of a movie for testimony which appellees did not produce at

the trial of this matter.

(3) Appellees urge that the trial court should have

issued its declaratory judgment that Louisiana Revised

Statutes 17:3101 et seg. was unconstitutional on its face and

as applied to the appellants. The evidence introduced at the

trial of this matter clearly indicated that University

officials acted under color of this statute in suspending

the students. Assuming that the Act is a legitimate exercise

of the police power of the state, the Act is defective on its

face in that it provides for summary expulsion in cases of

emergency, but fails to provide an adequate procedure for

the protection of constitutional rights after the emergency

is no longer present. In this regard, the Act provides for

_ 8 -

an appeal, but fails to prescribe a period within which the

appeal must be decided.

(4) Finally, appellants urged that the trial court

abused its discretion in granting such a broad and sweeping

injunction. Appellants recognize that University officials

have a legitimate interest in the orderly operation of the

University. However, the order of the court goes beyond

that interest and unnecessarily denies to appellants their

right to obtain an education in a state university. The

injunction, in effect, prohibits them from entry onto the

campus while appellants have not been properly dismissed

from the University. Perhaps more detrimental, is the fact

that the injunction infringes upon appellants' exercise of

First Amendment rights to free speech and association, and

has the effect of "chilling other students" in the exercise

of their First Amendment rights.

The history of this litigation of the actions of

appellees unquestionably establishes a continuous and con

sistent pattern of unreasonable and obstinate refusal to

follow the Constitution of the United States.

_ 9 -

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENTS

Appellants submit that, under the rules of Dixon v .

Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F.2d 150 (1951);

Zanders v. Louisiana State Board of Education, 281 F.Supp.

747 (1968), and a host of similar cases, their First and

Fourteenth Amendment rights to freedom of speech and their

rights to due process of law were violated in that appellants

were suspended from Southern University in Baton Rouge without

adequate notice and a prior hearing. Appellants, further, submit

that they were at all times acting pursuant to rights guaranteed

by the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

Appellants submit that Louisiana Revised Statutes

17:3101 et seg. (hereinafter Act 59) is unconstitutionally

vague and overbroad, and thus violative of the First and

Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United

States. In this regard, appellants urge that Act 59

unconstitutionally infringes on the exercise of First Amendment

rights by its broad and general language. Appellants, further,

urge that Act 59 was unconstitutionally applied in the instant

case.

10

Appellants, further, submit that their conduct was

at all times lawful and protected under the First Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States. Appellants contend

that while University officials may restrict the exercise of

First Amendment rights as to time, place and manner, said

restrictions must be narrowly defined so as not to amount to

an unlawful prior restraint.

Finally, appellants submit that the trial court judge

abused his discretion in granting such a vague and overbroad

injunction. In this regard, appellants urge that the injunction

issued against them goes beyond the scope of achieving

legitimate state objectives and operates as a prior restraint

on the exercise of their First Amendment rights.

ARGUMENT

I.

DUE PROCESS REQUIRES A HEARING BEFORE

SUSPENSION EXCEPT IN EXCEPTIONAL SITUATIONS.

IN SUCH EXCEPTIONAL CASES, THE HEARING

MUST BE HELD AS SOON AS PRACTICABLE AFTER

SUSPENSION.

Whenever a governmental body such as a state board of

education acts so as to injure an individual, the Constitution

of the United States requires that the act be consonant with

11

due process of law. The minimum procedural requirement

necessary to satisfy due process depends upon the circumstances

and the interests of the parties involved. Thus, there must

be some reasonable and constitutional ground for expelling

students from school,or the courts would have a duty to

require reinstatement. Dixon v. Alabama State Board of

Education, 294 F.2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961). In Dixon, supra

(the leading case extending the right of a hearing to students

expelled from a tax-supported university), the court said:

"...[D]ue process requires notice and some

opportunity for a hearing before a student

at a tax-supported college is expelled for

misconduct." (P. 158.)

In this context the courts, without deciding the question

of whether- education at a tax-supported college was a right or

a privilege, have held that because education is so essential

it could not be taken away without a hearing. Accord, <s.c£. ,

Knight v. State Board of Education, 200 F. Supp. 174 (M.D.

Tenn. 1961), and Esteban v. Central Missouri State College,

277 F. Supp. 649 (W.D. Mo. 1967).

The due process requirement of notice and an opportunity

to be heard must be "granted at a meaningful time and in a

meaningful manner." Armstrong v, Manzo, 380 U.S. 545 (1945).

The "meaningful time and reasonable manner" requirements are

12

always dictated by the particular circumstances of the case.

Courts have, however, held that the hearing must be afforded

prior to the actual deprivation, except in unusual circumstances

which justify postponing the hearing. This right to a prior

hearing has been upheld by the courts in a variety of situations

Armstrong v. Mango, supra (deprivation of parenthood); Cole_v.

Y0unq, 351 U.S. 536 (1956) (dismissal from employment);

Sniadach v. Family Finance Corr ., 395 U.S. 337 (1969) (pre

judgment garnishment); and more recently, Bell v,_Burson,

402 U.S. 535 (1971) (drivers license suspension), and Fuentes

v. Shevin, 407 U.S. 67 (1972) (repossession of goods upon

"buyer’s default).

In cafeteria and Restaurant Workers Union vv_McjElrgy:,

367 U.S. 886 (1961), the court recognized the difficulty in

establishing rules for due process in all cases:

"Consideration of what procedures due process

may require under any given set of circumstances

must begin with a determination of the precise

nature of the government function involved as

well as of the private interest that has been

affected by government action."

Applying this standard to the instant case, it is apparent

that the interests involved include the orderly operation of

a tax-supported institution and the right to exercise freedoms

guaranteed by the Constitution without undue restrictions.

13

in both Dixon, supra, and Zanders v.. Louisiana.State

noerd of Education. 281 F. Supp. 747 (1968) (a case involving

the appellees as party defendants), the court explained in

great detail the procedures to be afforded students faced with

expulsions for misconduct. In Dixon, supra, the court said:

"For the guidance of the parties in the

event of further proceedings, we state our

views on the nature of the notice and hearing

required by due process prior to expulsion

from a state college or university. They should,

we think, comply with the following standards.

The notice should contain a statement of the

specific charges and grounds which, if proven,

would justify expulsion under the regulations

of the Board of Education, ...the student should

be given the names of the witnesses against him

and an oral or written report on the facts to

which each witness testifies. He should also

be given the opportunity to present to the ̂ _

Board, or at least to an administrative official

of the college, his own defense against the

charges and to produce either oral testimony

or written affidavits of witnesses in his

behalf___ If these rudimentary elements of

fair play are followed in a case of misconduct

of this particular type, we feel that the

requirements of due process of law will have

been fulfilled. (Pp. 158-159.)

In Zanders, supra, the court cited Dixon with approval

and reaffirmed these basic requirements of due process. It

is rather striking that the State Board of Education, after

having been instructed on the requirements of due process,

would now seek to circumvent these requirements, which have

14

so carefully been defined by a federal court, by ruling the

appellants into state court.

It is now well recognized that in emergency situations

the due process requirement of a prior hearing may be post

poned until after the deprivation. The due process requirement

of a hearing prior to suspension has been extended to high

school discipline cases as well. Wood Wright, 334 F.2d

369 (5th Cir. 1964). While a summary suspension of students

for a short period of time may be justified where the

university officials seeh to suspend a student for more than

30 days, or as here, to expel the student, a rudimentary

due process hearing must be afforded the student. Williams

w county School Board, 441 F.2d 299 (5th Cir. 1971);

Dunn v. Tvler Independent School District, 460 F.2d 137

(5th Cir. 1972).

In the instant case appellants were summarily suspended

from school. The notice of November 9, 1972 did not specify

the period of the suspension and indicated that it would be

permanent unless the students applied for a hearing within

30 days of the suspension. Appellees contend as justification

for their unconstitutional actions that an emergency situation

existed which precluded affording appellants a hearing prior

to the suspension. Assuming that an emergency condition

15

existed on November 16, 1972, the emergency did not continue

until January 9, 1973 when appellants were ruled into court.

It is not contested that the school officials should

have responded to the situation in such a way as to calm it

down. Thus, they decided to suspend classes from November 16,

1972 until January 3, 1973. They also might have suspended

students, including appellants, immediately. However, once

the immediate situation had been brought under control, the

question then became, what might appropriately be done to

further discipline students who were involved.

The record indicates that during the period that the

'school was closed, staff and faculty members met and

discussed methods of returning the campus to its normal

operational posture. It was only at this point that they

decided to take action against the appellants. Surely, the

emergency did not continue to exist on January 3, 1973. The

record, further, indicates that there was no reason for

failing to afford appellants a hearing prior to bringing the

instant action.

The court addressed itself to this question in Stricklin

v. Recents of the University of Wisconsin, 297 F. Supp. 416

(W.D. V7is. 196 5) (a case wherein plaintiffs-students sought

a temporary restraining order for immediate reinstatement

16

following their suspensions without a hearing after several

weehs of disruptions on the University campus)- In ^ r icklin,

the court said:

"When the appropriate university authority

has reasonable cause to believe that danger

will be present if a student is permitted

to remain on the campus pending a decision

following a full hearing, an interim suspen

sion may be imposed. But the guestion

persists whether such an interim suspension

may be imposed without a prior 'preliminary

hearing' of any hind. The constitutional

answer is inescapable. An interim suspension

may not be imposed without a prior preliminary

hearing, unless it can be shown that it is

impossible or unreasonably difficult to accord

it prior to an interim suspension. Moreover,

even when it is impossible or unreasonably

difficult to accord the student a preliminary

hearing prior to an interim suspension,

procedural due process requires that he be

provided such a preliminary hearing at the

earliest practical time. (P. 420.)

Clearly, the hearing on the temporary restraining order

and the injunction was not sufficient to satisfy the due

process requirements enunciated in p.ixon.« More precisely,

Dixon provides that the student should be given notice of the

charges, and the notice should contain the names of the

witnesses and a report of the facts which each witness will

testify to. In the court proceeding appellants had no

opportunity to secure the names of witnesses against them.

Appellants were not furnished with reports on the facts which

17

the witnesses would testify to. Quite to the coni.2.ary,

University officials were permitted to testify as to reports

which, had been received from faculty and staff. Appellants

have not to this day been furnished vvith copies of these

reports. ■ By virtue of being temporarily restrained from

entry onto the college campus, appellants were, in fact,

denied the opportunity of securing witnesses in their behalf

from among the student body population.

Thus, the actions of the school officials in not affording

appellants a hearing prior to suspension or within a reasonable

time thereafter was in violation of the due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and the

suspensions should be invalidated.

IB

II

LOUISIANA REVISED STATUTE 17:1301 ET SEQ.IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL ON ITS FACE AND AS APPLIED

IN THAT IT IS VAGUE AND OVERBROAD, IN VIOLATION

OF DUE PROCESS AS EMBODIED IN THE FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENT.

Judicial intervention in school discipline cases in more

recent years has not been restricted to questions of procedural

due process. Thus, the validity of substantive school rules have

been subject to judicial scrutiny. Burnside v. Byars, 363 F.2d

744 (5th Cir. 1966); Hammond v. South Carolina State College,

272 F. Supp. 947 (D.S.C. 1967).

Appellants submit that the statute in question is

unconstitutionally vague and overbroad in violation of their

rights as guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to

the Constitution of the United States. The statute has as its

primary objective to control protest activity on the college and

university campuses within the state and to insure and preserve

the orderly educational processes. Appellants admit that this is

a legitimate state interest.

Appellants submit, however, that in achieving this legitimate

end, the state has unduly infringed upon their rights as

guaranteed by the First Amendment. In Soglin v. Kauffman, 295

F. Supp. 978 (1968), the District Court recognied the difficulty

in drafting regulations which seek to prohibit conduct which is

not protected by the First Amendment.

"Obviously it is not a simple matter to draft

a regulation which deals with means by which

‘causes' are supported or opposed, and which

19

undertake to prohibit those means unprotected

by the First Amendment without impairing those

which fire so protected, and which also avoids the

vice of vagueness."

The test under the "void for vagueness" doctrine was

established in Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U.S.

385 (1926) : '

" . . . a statute which either forbids or requires

the doing of an act in terms so vague that men

of common intelligence must necessarily guess at

its meaning and differ as to its application

violates the first essential of due process of

law. "

Also see United States v. Harriss, 347 U.S. 612 (1954),

where the court held that the constitutional requirement of

definiteness is violated by a statute that fails to give a person

of ordinary intelligence "fair notice that his contemplated

conduct is forbidden by the statute."

Appellees assert that the "conduct" of each of the

appellants is the ground for withdrawing their privilege to

attend Southern University. In this regard they rely on the

statute in question. Appellees further rely solely on disruptive

conduct as the standard for withdrawing permanently their

privilege to enter upon the campus of Southern University

Appellants maintain that imposition of such a severe

disciplinary penalty as permanent exclusion from the University

solely by reference to so vague a standard as "disruptive conduct"

violates the principle of fundamental fairness guaranteed by

the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. More

specifically, appellants contend that the standard of disruptive

conduct:

20

a) is void for vagueness in that it fails to

put students on notice of what behavior

constitutes a violation of the statute, and

would thus be sufficient grounds for permanent

exclusion from the university;

b) unconstitutionally vests university officials

with unfettered discretion to determine when

there is a violation of the statute;

■c) offends due process of the law in that its

vagueness effectively deprives a student

threatened with permanent expulsion of the

opportunity to make a defense;

d) is overbroad and impermissibly restrains the

exercise of the rights of free speech and

association guaranteed by the First Amendment.

While the void for vagueness doctrine originates and finds

its primary application in the field of criminal lav/, it has

been held applicable in other areas as well:

"the ground or principle of the decisions was not

such as to be applicable only to criminal prosecu

tions. It was not the criminal penalty that was

held invalid, but the exaction of obedience to a

rule or standard which was so vague and indefinite

as really to be no rule or standard at all." Small

Company v. American Sugar Refinery Co., 2 6 7 U .S .

233,' 239 (192 5).

Lav/s inhibiting the exercise of First Amendment rights

have frequently been set aside for vagueness. Cramp v. Board of

Public Instruction, 368 U.S. 278 (1961), a case v/here the court

declared unconstitutional a statute requiring public school

teachers to sign a loyalty oath as a condition to continued

employment.

In Soglin v. Kauffman, supra, the United States District Court

held " . . . that a regime in which the term 'misconduct' serves

as the standard violates the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment by reason of its vagueness or, in the alternative,

violates the First Amendment as embodied in the Fourteenth

Amendment by reason of its vagueness and overbreadth." Id. at

21

15-16. Appellants submit that "misconduct" as construed in

Soglin is no different from "disruptive conduct" as is

embodied in the statute in question, and thus Soglin should

control the instant case.

Unfettered Discretion

The need for "ascertainable standards," Hornsby v.

Allen, 326 F.2d 605 (1964), to govern decision-making by

administrative officials is clear. In Holmes v. New York

City Housing Authority, 398 F.2d 262 (1968), the court said

that "the existence of an absolute and uncontrolled discretion

in an agency of government vested with the administration of

a vast program . . . would be an intolerable invitation to

abuse." In the instant case, Dr. Netterville and other

University officials are vested with unfettered discretion

to determine when there has been a violation of the act. This

fact is compounded when the activity of those charged with

violation of the act was directed toward the removal of those

vested with the discretion. In many instances courts have

invalidated actions taken by administrative officials who have

taken such action without reference to ascertainable standards

embodied in rules or regulations, Holmes, supra; Hornsby v.

Allen, supra; Barnes v. Merritt, 376 F.2d 8 (5th Cir. 1967).

Appellees, including Dr. Netterville and members of the

State Board of Education, assert that school officials have

the power to determine when a student has violated the act.

This power, they assert, may be exercised without reference to

- 22 -

ascertainable standards to guide and limit the University

officials in the exercise of this discretion. Thus, the situation

exists where university officials may decide that certain conduct

is violative of the statute and are empowered to impose sanctions

in one set of circumstances, and under similar circumstances

involving like conduct determine that no violation has occurred.

The arbitrary or capricious act of a university official

in dismissing a student from the University involves the imposition

of a severe sanction. It may summarily destroy the aspirations

of appellants, their parents, and others like them, as well as

to defeat the legislative purpose embodied in the statute in

question. It is, therefore, imperative that the appellees

establish standards to limit university officials in the exercise

of discretion to legitimate purposes and to provide a basis for

review of such decision. See Bishop v. Inhabitants of Rowley, 43

N.E. 191 (1896).

Lack of Standards

Appellants are required by the statute to refrain from

"disruptive conduct." This term is susceptible of such vagaries

of interpretation and application that it is in reality no

standard at all. Appellants have, at most, been charged with

being responsible for the "disruptive conduct" which occurred on

the campus of Southern University during the fall semester, 1972.

The vagueness of the standard, the charges and their possible

ramifications deprive appellants of the opportunity to rebut the

claims of misconduct. See, generally, Joint Auto-Facist Refugee

Comm, v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123, 161-173 (1951)(concurring

opinion). In reality, the statute impermissibly shifts to the

23

appellants an impossible burden of proof: i.e., appellants are

required to establish their non-disruptive conduct. Cf. Speiser

v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 (1958), where the court held that the

enforcement of a state tax statute can not place the burden of

showing lawfulness of conduct upon the accused:

"its enforcement through procedures which place

the burdens of proof and persuasion on the

taxpayer is a violation of due process.

In the instant case university officials acting without

reference to ascertainable standards declared actions by students

to be disruptive. Thus, in any case where there was a large

gathering of students on the campus and a substantial amount of

noise was generated such a determination could have been made.

In such a case an unconstitutional and impossible burden is

shifted to the student to prove that his conduct was not

disruptive. Such a statute cannot stand without ascertainable

standards to govern the imposition of its sanctions.

Chilling Effect On First Amendment Rights

Undeniably, the behavior of students within a tax-supported

institution is an appropriate subject for regulation by appellees.

And the power to regulate clearly implies the power to impose

penalties for violation of university rules and regulations.

The regulatory power is not unrestricted, however, as noted

by the Supreme Court in Shelton _v_L_ JTucker, 364 U.S. 479, 488 (1960).

" . . . even though the governmental purpose be

legitimate and substantial, that purpose cannot

be pursued by means that broadly stifle fundamental-

personal liberties when the end can be more narrowly

achieved."

Overbreadth is inherent in the vagueness of "disruptive

conduct" as a disciplinary standard. Appellants are young, black

students in a predominantly black institution run by black

24

administrators who are appointed by an all-white Board of Education.

Appellant, being discontent with the policies of the institution,

sought redress through exercise of their First Amendment rights.

The effect of the disciplinary policy which appellees have

superimposed on the appellants' rights of free expression and

tassociation'is readily apparent. The only question, then, before

the Court is whether the instant statute, burdening as it does

fundamental constitutional rights, can withstand the strict scrutiny

called for by prior decisions of the United States Supreme Court.

It is not sufficient for appellants to come into court

and say that this statute has not in fact been used to impair

appellants' expression or association. What makes a statute

unconstitutional is that it is "broad and vague" and "lends

itself to selective enforcement against unpopular causes." See

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963).

The United States Supreme Court has held that when government

acts to limit the exercise of First Amendment rights there must

be a showing of a "compelling state interest." NAACP v. Button,

id. at 438.

It is important to stress in this brief that appellants

fully acknowledge that school authorities may, and indeed must

at times, regulate the exercise of First Amendment rights in

order to protect the educational purpose of an institution.

Appellants, further, recognize that the right to restrict First

Amendment rights by administrators must be exercised only "in

carefully restricted circumstances." Tinker v. Des Moines School

25

District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969). Thus, free speech is subject

to reasonable restrictions as to time, place, manner and duration.

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U.S. 87 (1965); Cox v. Louisiana,

379 U.S. 536 (1965).

The statute in question does not limit the exercise of First

Amendment rights with regard to time, place, manner and duration.

It, in effect, prohibits all demonstrations on the college campuses

within the state. Such a broad prohibition on the exercise of

First Amendment rights unnecessarily chills the exercise of the

right, and the statute cannot stand.

Appellants also urge that the statute was unconstitutionally

applied in the instant case. Assuming, arguendo, that the statute

is constitutional on its face, then appellants maintain that

the statute should not have been applied in this case. The

record of this trial clearly indicates that Southern University

was closed on November 16, 1972 and did not reopen until January

3, 1973. To escape constitutional invalidity the statute in

question must be construed as authorizing expulsions without

a hearing only in emergencies. Only if the statute is so

construed can it conform to the requirements of due process.

The expulsions in the instant case cannot be justified

as emergency expulsions since no such emergency was shown

to have existed on the date that the action was initiated in

District Court. The statute in question (Louisiana Revised

Statute 17:3109) provides that the president of the educational

institution experiencing a riot or similar emergency "shall request

26

that the governor proclaim the existence of a state of emergency."

No such emergency was ever declared in the instant case. Assuming,

arguendo, that such a state of emergency did exist on November

16, 1972, surely it did not continue to .exist until January 3,

1973.

t

Therefore, appellcints submit that the contention that

there was a "state of emergency" at the time of the suspensions

is without factual basis and should not be allowed as justification for

appellees' unlawful conduct.

2 7

Ill

m m CONDUCT OF APPELLANTS IS CONSTITUTIONALLY

protected under the first m b fourteenth a m e n d

m e n t™ the constitution OF THE UNITED STATES

It is now firmly settled that minors and young adults

are entitled to many, if not all, of the protections afforded

by the united States constitution. In.Re Ggult, 387 U.S. 1

(1967). indeed, the United States Supreme Court declared as

long ago as 1943 that the First Amendment rights must be

protected from encroachment by school authorities. Tne

Fourteenth Amendment, as now applied to the states, protects

the citizen against the State itself and all of its creatures-

Eoards of Education not excepted." West Virginia State Board

v . Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943). In that case the United

States Supreme Court held unconstitutional the expulsion from

school of students for their failure to salute the flag of

the United States.

in more recent years the United States Supreme Court has

also spoke on the subject of First Amendment freedoms:

"First Amendment rights applied in light

offhe special characteristics of the school

environment are available to teachers an

students. It can hardly be argued that eith students or teachers shed their constitutional

rights to freedom of speech or expression at the

schoolhouse gate."

See w-inVcr u. Des Moines Independent Community School^strict,

393 U.S. 503 (1969). See also, Burnside v. Byars, 363 F.2d

28

744 (5th Cir. 1966). Appellants believe that the settled

entitlement of university students to First Amendment

liberties, as affirmed by the Supreme Court, must control the

idetermination of the instant case.

It appears that the district court was under the impression

that the disciplining of appellants was for a violation of

school regulations respecting the unauthorized use of school

facilities. However, this was not the case. The record does

indicate that appellants conducted meetings almost daily in the

gymnasiums on campus. The record, further, indicates that Dr.

Netterville and the Committee appointed by Governor Edwards

attended these meetings. The record indicates that permission

was never obtained to use these buildings for any such meetings.

Appellees now contend that appellants violated university

regulations in conducting its meetings in the gymnasiums without

permission.

/assuming, arguendo, that there was a valid university

regulation governing the use of said buildings, then that

regulation was waived when the students conducted their meetings

with the acquiescence of Dr. Netterville who attended and

addressed the student body there. The record clearly indicates

that Dr. Netterville never advised the students that they could

not conduct their meetings in the gymnasiums even though he

had ample opportunity to do so.

29

At issue here is not the question of disruptive conduct,

but the right of students to protest the policies of their school.

The method they chose was a boycott of classes. Surely, they

urged those students in attendance to leave those classrooms.

Their methods, stated more precisely, were to enter into a class

room and to ash the instructor for permission to address the

students. Only after obtaining permission, did appellants

address the students in a classroom. This method was pursuant

to the policy and practice of the university.

Before the court,appellees support dismissal on the ground

that appellants' actions served to disrupt orderly school

operations. Appellants submit that their boycott was successful.

At times the boycott was estimated to be ninety percent (90%)

effective. Surely, the normal operation of a school is disrupted

when ninety percent (90%) of its students are boycotting classes.

Appellants submit that such a disruption is not actionable so

long as the methods employed to achieve the result are lawful.

University officials contend that appellants intimidated and

coerced students and faculty. This contention is not supported

by the evidence presented at the trial.

University officials as well as the court were unable to

distinguish intimidation from "peer group pressure.” In the

instant case, appellants merely urged other students to refrain

from going to class. The transcript is devoid of testimony by

any student or faculty member who was ever physically or verbally

30

attacked by any of the appellants. The record is devoid of any

testimony indicating actionable disruptions by any of the appellants.

Thus, the judgment of the court is unsupported by any evidence

that appellants disrupted the operation of the university.

Appellants submit that sanctions may be imposed by

university officials only on the basis of "substantial evidence."

See Jones v. State Board of Education, 279 F. Supp. 190 (M.D.

Tenn. 1968); Sullivan v. Houston independent School District,

307 F. Supp. 1328 (S.D. Texas 1969). Appellants further submit

that this substantial evidence must be presented at the hearing.

Esteban v . Central Missouri State College, supra. Appellees in

their complaint and supporting aff.idav.its alleged that appellants

intimidated and coerced students and teachers. Such allegations

are unsupported by "substantial evidence."

31

IV

AN INJUNCTION ISSUE WHICH LIMITS THE EXERCISE

OF FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHTS MUST BE COUCHED IN

THF NARROWEST TERMS WHICH WILL ACCOMPLISH THE

* OBJECTIVES SOUGHT TO BE ACHIEVED. THE INJUNCTION

ISSUED BY THE TRIAL COURT VIOLATES THE FIRST

AMENDMENT IN THAT IT IS AN ILLEGAL PRIOR RESTRAINT ON THE EXERCISE OF FIRST AMENDMENT

RIGHTS.

The final question presented to the court by appellants

appeal is whether the injunction, burdening as it does

fundamental constitutional rights, can be allowed to stand.

Appellants maintain that the granting of such a broad and

sweeping injunction violates due process of law. Before

deciding on the constitutionality of the injunction, the

court should first consider whether the district court abused

its discretion in even hearing the case. Appellees concede

that this case involved alleged acts of misconduct by students

at a state-supported university. Appellants submit that the

district court was not the proper forum to decide the question

of misconduct in the first instance. In Stricklin, supra,

the court addressed itself to this very point:

"This court is clearly not the forum for an

initial adversary proceeding on the question

whether a particular student is guilty of a

particular act or omission justifying dis

ciplinary action within the university. Had a reasonable adequate preliminary hearing been

furnished to each of the plaintiffs within the

university, and had a showing been made there

comparable to that now attempted here, and had

the Regents concluded that interim suspensions

32

were warranted, and had the plaintiffs then

attached the interim suspensions in this court

as a denial of procedural due process, the issue

would have lent itself to rather ready disposition " (pp. 421-422).

In the instant case there was an- existing administrative

procedure for handling school disciplinary problems. Appellees

circumvented that procedure and filed the instant action. in

Dixon, supra, the court quoted from Professor Warren A. Seavey's

Dismissal of Students: Due Process, 70 Harvard Law Review

1406, on the question of student suspensions:

"It is shocking that the officials of a state

educational institution, which can function

properly only if our freedoms are preserved,

should not understand the elementary principals of fair play. It is equally shocking to find

that a court supports them in denying to a student

the protection given to a pickpocket. (Underline added for emphasis).

Appellants' submit that the action of the trial court in

entertaining this action when there was an existing procedure

for dealing with school disciplinary matters is likewise

shocking, especially in view of the fact that only a few short

years ago the State Board of Education had been instructed on

procedures it should follow in school discipline cases. Zanders,

supra.

Appellants, finally, argue that the permanent ban from

the campus and subsequent denial of any public education vio

lates the equal protection and due process clauses of the

United States Constitution. Appellants urge that where there

has been an absolute denial of education, the actions of the

33

State Board of Education and the trial court are subject to

strict scrutiny. Students who have been expelled from school

are denied the right to an education that is available to all

other students. This total denial violates equal proi.ection

of the laws unless the denial serves a compelling state

interest that cannot be fulfilled by less drastic means.

Cf. San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodrique_z,

U.S. , 41 U.S.L.W. 4407 (March 21, 1973); Griffin v.

School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964).

An analysis of appellees' action clearly demonstrates

that there was no showing whatsoever that the drastic remedy

of permanent expulsion was necessary. It appears that no

inquiry was made as to the past disciplinary history of the

individual students. No exploration was made of alternative

methods of insuring that the students, whatever they may have

done prior to November 16, would in the future refrain from

disruptive behavior. Alternative remedies, e_._a. , a return to

school on a probationary status, were apparently not even

considered. Thus, the appellees failed to meet its burden

of showing that its proper objective of maintaining discipline

could not be achieved by less drastic means.

Appellants submit that the objectives sought to be

achieved by appellees must be achieved by the narrowest effective

34

means. Stated more simply:

”. . . a governmental purpose to control or

prevent activities constitutionally subject to

state regulation may not be achieved by means

which sweep unnecessarily broadly and thereby

invade the area of protected freedoms . . . even

though the governmental purposes be legitimate

and substantial, that purpose cannot be pursued

by means that broadly stifle fundamental personal

liberties when the end can be more narrowly

achieved." (NAACP v. Alabama ex. rel., Flowers,

377 U.S. 288 (1964). '

As applied to the injunction issued in the instant

case, the court clearly abused its discretion, when it issued an

injunction which denied to the student their right to an education

in order to achieve a legitimate state interest when it was

possible to achieve those objectives without infringing on

appellants' rights to an education. Lihe the requirement that

legislation which may trench on First Amendment interests meet

"strict" standards of specificity, Smith v. California, 361

U.S. 147 (1959), then an injunction which may intrude upon

constitutionally protected rights must also focus upon the

purposes sought to be achieved.

The question now before the court is whether the legitimate

interest of the state could have been achieved by less drastic

means. In Shelton v. Tucker, supra, the court said:

"and if there are other reasonable ways to achieve

these goals with a lesser burden on constitutionally

protected activities, a state may not choose the way

of greater interference. If a state acts at all, it

must choose the least drastic means."

35

Assuming, arguendo, that appellants engaged in disruptive

acts and assuming that the district court should have assumed

jurisdiction over the matter, then appellants submit that the

court in> reaching its judgment should have granted only the

relief required to achieve the lawful objectives of the state.

In Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471 (1972) (a case involving

the legality of a parole revocation hearing), the court addressed

itself not only to the relevant facts but also to the appropriate

remedy:

"This hearing must be the basis for more than

determining probable cause, it must lead to a

final evaluation of any contested relevant

facts and consideration of whether the facts

as determined warrant revocation."

See also Payne v. Board of Regents of University of Texas,

355 F. Supp. 199 (W.D. Texas 1972), affirmed 474 F.2d 1397 (5th

Cir. 1973) where the court said:

"Indeed, if the plaintiffs here present no such

danger, the Board spites its broader purpose of

providing higher education to qualified students

when it needlessly prevents them from continuing

their studies."

Appellants, therefore, submit that the harsh remedy imposed

in this case was not necessary to achieve the legitimate interest

of the state and as such constituted an abuse of discretion.

CONCLUSION

For the above and foregoing reasons, the judgment of

the trial court should be reversed and appellants reinstated as

36

students at Southern University pending a hearing consonant

with due process of law.

Respectfully submitted,

348 Baronne Street

Suite 301

New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

JOHN W. WALKER

Walker, Kaplan and Mays

622 Pyramid Life Bldg.

Little Roch, Arkansas

JACK GREENBERG CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 100.19

Attorneys for Appellants

37

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing Appellants 1

Brief were served upon counsel for Appellees by depositing the

same in United States mail, first cldss, postage prepaid,

addressed as follows:

J. Reginald Coco, Jr.

P.0. Box 44005

Capitol Station

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Vanue B. Lacour

8950 Scenic Highway Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Arnold Gibbs

301 Napoleon Street

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

This 3rd day of August, 1973.

38

*•

•