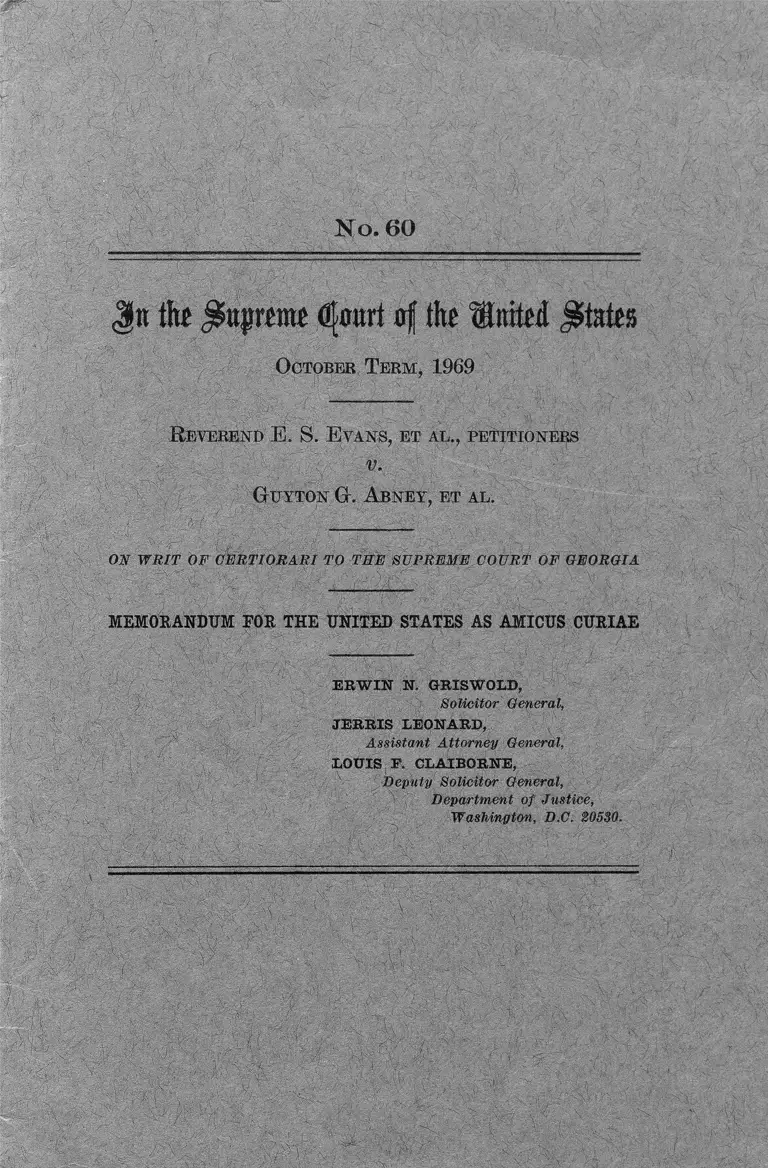

Evans v. Abney Memorandum for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Evans v. Abney Memorandum for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1969. d3bc1248-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8e3db0f9-56b3-4278-8669-7d84445db7f4/evans-v-abney-memorandum-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

N o. 60

$n tl« Supreme fl̂ ourt of the altitod JStates

October T erm, 1969

R everend E. S. E vans, et al., petitioners

v .

G uyton G. A bney, et al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

MEMORANDUM FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

ERW IN N. GRISWOLD,

Solicitor General,

JERRIS LEONARD,

Assistant Attorney General,

LOUIS F. CLAIBORNE,

Deputy Solicitor General,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D.C. 20530.

J tt the ^ttpreme fljaitrf of the United States

O cto ber T e r m , 1969

Xo. 60

R everend E. S. E vans, 'et al., petitioners

v,

G uyton O. A bney, eT al.

O N W R IT OF C E R TIO R AR I TO THE SUPREM E COURT OF GEORGIA

MEMORANDUM FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

The ease is fully stated in the brief filed on behalf

o f the petitioners and we do not recapitulate the facts

here. We submit this short memorandum to focus on

particular arguments and to express the interest of

the United States.

The government participated in this Court when the

ease was here before as Evans v. Newton, Xo. 61,

October Term, 1965, 382 U.S. 296. As it happens, the

United States has a special connection with Baeons-

field through substantial federal aid granted for the

improvement of the facility some years ago and as

surances then received that the public character of

the park would not be changed. It is, moreover, a

(l)

368- 236— 69

2

matter o f concern that all the residents of a munici

pality have been deprived of an important public

facility on account, of race. Then, as now, however,

there was more at stake than non-diseriminatory en

joyment of a large, recreational park in Macon,

Georgia.

As the case returns, it involves potentially far-

reaching questions relating to the enforcement of

racially restrictive, stipulations in grants establish

ing charitable trusts. The United States speaks to

those issues because of the continuing national con

cern to eradicate race discrimination in our public life.

... ; ABGTJMEWT

The ultimate question in this case is whether a

largo recreational park which this Court has held

subject to the constitutional rule of nondiscrimina

tion shall be closed and the property returned to

private hands rather than being opened up to the

Negro citizens of the area. The Georgia courts have

so decreed, declining to disregard the now unenforce

able racially restrictive provision of the will which

established the park half a century ago. Those who

support the judgment below—including the adminis

trators of the park, the trustees of the property, and

the heirs of the testator, with no opposition from the

municipality which would lose an important recrea

tional facility—argue that this decision ends the mat

ter, insisting that there is no federal constitutional

question involved. We disagree, sharing the view of

the petitioners that the Fourteenth Amendment stands

in the way of this result.

3

1. At the outset, we confront the claim that the

-case involves nothing more than the construction of a

will and an application of the local law of charitable

trusts and therefore presents no federal question

whatever. The answer, we suggest, is that given by

this Court when immunity from scrutiny was asserted

writh respect to a discriminatory exercise of the gen

erally absolute power to redefine municipal bound

aries: insulation from federal judicial review, “ is not

carried over when state power is used as an instru

ment for circumventing a federally protected right.”

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 II.S. 339, 347. The tradi

tionally local setting does not oust the constitutional

inquiry when the charge is, as here, that State action

threatens to deny important public benefits on the

ground of race.

What is more, the present ease does not intrude

far into the traditional domain of private choice. No

one here is remotely suggesting review of the motives—

even racial bias—which govern the decisions of testators

in writing or rewriting wills or establishing trusts. Nor,

for that matter, do the present arguments call into

question the power of any private individual to revoke

a grant, terminate a trust, or close an established facility

over which he has retained control—or to abandon a

business—rather than comply with a federal constitu

tional or statutory requirement of non-discrimination.

We deal only with affirmative State action with

drawing a public facility to avoid a declared obliga

tion to cease discrimination on the basis of race.

And, finally, the case does not involve any real issue

of construing a testator’s actual intent. Although Ben-

4

ator Bacon made clear that he shared the prevailing

prejudice of his time and place against the “mixing”

of the races “ in their social relations,” then thought

to include the use of recreational facilities (cf. Civil

Bights Cases, 109 U.S. 3, 22, 24), he did not express

himself on the question whether the racial restriction

in his grant, if unenforceable, should defeat his in

tention to establish a public park. There is no way

of knowing what his choice would have been had he

known the present alternatives when he wrote his

will. Still less is there any basis for saying that he

would wash Baeonsfield closed altogether after half

a century because the law now requires that ISTegroes

also be admitted. It is obvious the Senator never ad

verted to the eventuality that his “perpetual” grant

should be withdrawn from the public and given over

to his heirs. Indeed, it is doubtful whether any right

of reversion was meant to be attached to his gift to

the municipality.

The fact of the matter is that the decision to prefer

closure to non-discrimination is not attributable to

Senator Bacon, but to the State of Georgia, acting

through its courts, at the prompting of the administra

tors of the park (who may, in that capacity, be deemed

public officers, since they are administering a public

facility). The reversion of the Baeonsfield property to

private hands did not occur automatically, by opera

tion of law: the active participation of an agency of

the State necessarily intervened before that result

could be accomplished. Nor was the decree a mere

formality, inexorably predetermined by events. There

were many alternatives, one of which had to be se

5

lected. Our submission is that Georgia contravened

the Fourteenth Amendment by making a discrimina

tory choice.

2. What were the options? In the first place, the

restrictive provision might have been treated as not

written, because contrary to overriding public policy

embodied in the supreme law of the land. Cf. Hurd

v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24, 34-36. In the absence of any indi

cation that a comparable facility was then available to

the iSTegro residents of Macon, it is doubtful that Sen

ator Bacon’s attempt to exclude them totally from a

public park satisfied even the “ separate but equal” doc

trine of Pless-y v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, prevailing in

1911 when the will was written. And it is at least argu

able that the intervening decision in Buchanan v.

Warley, 245 U.S. 60, outlawed racial restrictions of

this kind before the bequest of the park property to the

public was executed in 1920. But even if it was only

later that it became constitutionally unenforceable, the

Georgia courts might have struck the clause prospec

tively, thus avoiding giving any effect to an offensive

stipulation. Cf. Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249, 254.

Another alternative was to decline reversion on the

ground that the park had been irrevocably dedicated

to the public. As we have noted, Senator Bacon’s will

did not provide for contingent reversion to his heirs;

on the contrary, the instrument required that “all

right, title and interest” in the property, expressly

including “ all remainders and reversions,” be vested

in the municipality, for the “perpetual and unending”

6

benefit of the public, and, specifically, to be “ forever

used and enjoyed as a park and pleasure ground,”

“ under no circumstances” to be “ sold or alienated or

disposed of, or at any time for any reason devoted

to any other purpose or use” (A. 19; see also, the

last sentence of Item 3rd of the Codicil, at A. 30).

Both the deed from the executors to the City exe

cuted upon delivery of the property in 1920 (A. 353;

see also A. 405-409) and later representations made

to the United States (A. 440-441, 448, 451) indicate an

indefeasible title in the municipality. So, also, the

actual use of the park by the public for half a century

argued against implying a requirement of reversion.

See Ga. Code § 85-410.

Of course, if the municipality had been found to

hold an irrevocable title to the property, the decree

below could not have been entered. The suit of the

heirs, lacking any legal interest, would have been

dismissed. The City itself presumably could not close

the park merely to avoid desegregation. Cf. Griffin v.

School Board, 377 U.S. 218. And, at all events, the

city was not praying for such a result; indeed, the

State Attorney General, representing the public bene

ficiaries, was, at least formally, urging continuance of

the park (see A. 502, 509, 512, 515).

Finally, the most obvious solution was to apply the

cy pres principle to continue Baconsfield as a public

park, albeit desegregated, on the ground that this

would be carrying out the dominant purpose of the

charitable trust. See Ga. Code § 108-202. Surely, it

would have been natural to view the establishment of

a public recreational facility as the main object of

7

the trust and to find that the constitutionality required

admission of Negroes—which did not oust the original

class of beneficiaries—would not defeat that goal.

A charitable court might indulge the supposition that

Senator Bacon himself would amend his grant to re

move the exclusionary clause if he were alive in the

changed circumstances of today. But, however that

may be, it was certainly within the normal boundaries

of the eij pres doctrine to treat as incidental, and not,

of the essfenee, the racial stipulation attached to the

trust. Indeed, it is difficult to understand how the

courts below could find that exclusion of Negroes,

rather than continuation of the park as a public fa

cility, was'’ the fundamental purpose of the grant.

In our tview, the availability of the several less

drastic options, each apparently consistent with loeal

law, invalidates the choice made. That is true, we

believe, even if each of the alternatives was equally

permissible as a matter of State law. Whatever the

proper limits of the principle that the Constitution is

not violated by neutral State action unavoidably sup

porting a private discriminatory decision, but see

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, the claim of neutrality

will not avail when, in light of other possible solu

tions, the means selected needlessly aids discrimina

tion. Cf. Reitmcm v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369. As a

matter of fact, however, it seems plain that the

courts below were not confronted with an evenly bal

anced series of options; everything favored a resolu

tion that would permit continuation of the park. In

the circumstances, we are inevitably led to the conclu

sion that in preferring the last resort of reversion the

8

Georgia courts were applying a special rule which

accords critical weight to racial restrictions. It is of

course immaterial whether the rule was independently

fashioned by the courts or merely reflects the public

policy of the State. In either case, impermissible

governmental action is present: the attempt to escape

official responsibility by invoking Senator Bacon’s

supposed preference cannot succeed. Cf. Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 IT.S. 715, 725.

3. It only remains to respond briefly to the sug

gestion that the decree below cannot offend the Con

stitution because the petitioners and the class they

represent have no “ federal right” to enjoy Bacons-

field Park and thus have not been legally injured by

the action which closes it. There are several answers.

To be sure, the Fourteenth Amendment does not

grant petitioners a right, simplidter, to enjoy the

Baeonsfield property. But it does assure that they

shall not be excluded from the benefits of a public

facility on the ground of race. And that is precisely

what is threatened here: the method is a total closure

of the park, but the purpose is racial, and the effect,

so far as Negroes are concerned, is the same as if

whites remained free to enjoy the park. It does not

alleviate the practical injury to the class that others

also are adversely affected by the discrimmatorily

motivated action. “ Equal protection of the laws is not

achieved through indiscriminate imposition of in

equalities.” Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, 334- U.S. at 22,

It is, moreover, plain that the disadvantaged Negro

community of Macon will suffer unequally by the

9

withdrawal of Baconsfield to private lands. Cf. Grif

fin v. School Board, supra.

There is another aspect to the decision below. The

fact is that Negroes are to be deprived o f the park

solely because they insist on exercising their declared

right to share it so long as it remains open to the

public. That is more than imposing an impermissible

penalty on the assertion of a constitutional right,

cf. Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618, 631; the con

sequence is so drastic as wholly to discourage the

bootless effort in future. Cf. Barrows v. Jackson,

supra. And there is of course a corresponding en

couragement to resist voluntary acquiescence in non

discrimination. That, too, is an involvement forbidden

to State officers by the Fourteenth Amendment. Cf.

Reitrnan v. Mulkey, supra; Anderson v. Martin, 375

U.S. 399; N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449, 463.

Finally, and perhaps most important, the decision

below injures the Negro citizens of Macon in the same

fundamental sense as all officially supported racial

discrimination. Here, as in Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U.S. 303, 308, the published official action directed

at Negroes as a race “ is practically a brand upon

them, affixed by the law, an assertion of their in

feriority, and a stimulant to that race prejudice which

is an impediment to securing to individuals of the

race that equal justice which the law aims to secure

to ail others.” This alone condemns the action of the

State courts, regardless of whether petitioners can

show any more tangible loss. Cf. Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483, 493-495. As we view it, the

decision strains to reach the extreme result of reversion

and thereby announces an official view that the

10

Negro’s presence in the park would be so obnoxious

that it is preferable to close the facility altogether.

That, we submit, is a plain denial of that “ equal

protection of the laws” which the Fourteenth Amend

ment was framed to assure.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, the judgment below should

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted.

E rw in N. Griswold,

Solicitor General.

-Terris L eonard,

Assistant Attorney General.

Louis F. Claiborne,

Deputy Solicitor General.

N ovember 1969.

U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1969