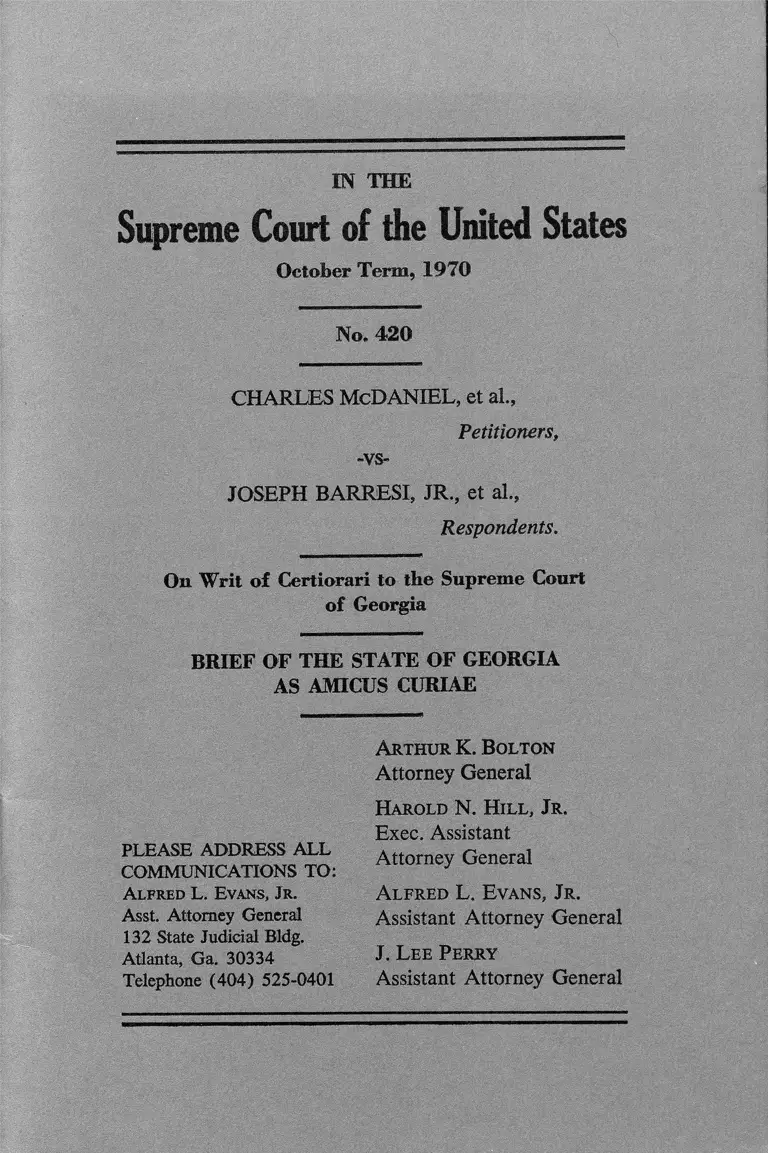

McDaniel v Barresi, Jr. Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McDaniel v Barresi, Jr. Brief Amicus Curiae, 1970. bf278384-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8e459205-a180-4656-83ae-8aff5250cbd7/mcdaniel-v-barresi-jr-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

m THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1970

No. 420

CHARLES McDANIEL, et al.,

Petitioners,

-VS-

JOSEPH BARRESI, JR., et al.,

Respondents.

On W rit o f Certiorari to the Supreme Court

o f Georgia

BRIEF OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Arthur K. Bolton

Attorney General

Harold N. Hill, Jr.

Exec. Assistant

Attorney General

Alfred L. Evans, Jr.

Assistant Attorney General

J. Lee Perry

Assistant Attorney General

PLEASE ADDRESS ALL

COMMUNICATIONS TO:

Alfred L. Evans, Jr.

Asst. Attorney General

132 State Judicial Bldg.

Atlanta, Ga. 30334

Telephone (404) 525-0401

INDEX

INTEREST OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA. . . . 1

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED..................................... 2

STATEMENT............ ................................................. 2

(1) Nature of the Case............................................. 2

(2) Statement of Facts........................................ 3

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT............................... 20

A R G U M E N T ..................... 24

(1) Governmental attempts to impose racial exclu

sions (i.e., quota, percentage or balance require

ments) upon pupils and teachers in Georgia’s

public schools are unauthorized by the Constitu

tion and laws of the United States in the first

instance, but in any event are prohibited in that

they violate transcendental rights secured to

children, parents, teachers and the State itself

under said Constitution and laws.................... 24

(a) The government of the United States is with

out legal authority to impose racial exclusions

by coercing school attendance in such manner

as to achieve any particular balance, quota,

number or percentage requirement for a given

race in a given school.................................. 26

(b) Even if a rational connection could be said to

exist between the legitimate governmental goal

of prohibiting State-required racial separation

and the imposition of racial quotas as one

available means of achieving this legitimate

end, such means is a remedial oversweep

which violates transcendental countervailing

rights, privileges and immunities secured to

parents, pupils, teachers and the State by the

Constitution and laws of the United States. 36

x

Page

(2) Even if racial exclusions in the form of quota,

percentage or balance requirements could be said

to be constitutionally permissible or required,

existing lop-sided enforcement against children,

parents, teachers and school districts in Southern

States only, constitutes invidious sectional dis

crimination which in and of itself is violative of

rights secured to such persons under the various

“due process” and “equal protection” guarantees

of the United States Constitution................... 46

CONCLUSION.......................................................... 54

u

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

Alexander v. Holmes County Board o f Education,

396 U.S. 19 (1969)................................. 3,21,30,32,56

American School o f Magnetic Healing v.

McAnnaulty, 187 U.S. 94 (1902)..................... 52

Banks v. Housing Authority, 120 Cal. App. 2d 1,

260 P. 2d 668 (1953)........................................... 21,34

Barresi v. Brown, President o f the Clarke County

Board o f Education, et al., 226 Ga. 456,_____

S.E. 2 d _____ (1970)............................................... 3

Bivins v. Board o f Public Education and

Orphanage for Bibb County, et al., No. 1926,

M.D. Ga. (Order filed Jan. 21, 1970)................... 16

Bivins v. Bibb County Board o f Education, 424 F.

2d 97 (5th Cir. 1970).........'.................................... 16

Board o f Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S.

624 (1942)............ 22,23,25,35,36,38-39,55

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954)...................... 48

Bradley v. School Board of the City o f Richmond,

Virginia, 345 F. 2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965)................. 4

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E.D.S.C.

1955)......................................................................... 4

Brown v. Board o f Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954). . 3-6,14,20-22,26,28-29,35,43,56

Brown v. McNamara, 263 F. Supp. 686

(D.N.J. 1967)...................................................... 48,49

Cain v. Bowles, 4 F.R.D. 504 (D. Ore. 1945)........... 52

Colon v. Tompkins Square Neighbors, 294 F.

Supp. 134 (S.D.N.Y. 1968).......................... 21,33-34

in

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Dixon v. District o f Columbia, 129 U.S.App.

D.C. 341, 394 F. 2d 966 (D.C. Cir. 1968)............. 52

Dismuke v. United States, 297 U.S. 167

(1936)........................................................................ 52

Dobbins v. Los Angeles, 195 U.S. 223

(1904).............................................................. 23,51-52

Ellis v. The Board o f Public Instruction of

Orange County, Florida, 423 F. 2d 203

(5th Cir. 1970)......................................................... 15

Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97 (1968). . .. 22,28,39

Erie Railroad Company v. Tompkins, 304 U.S.

64 (1938)................................................................... 35

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963)............................... 35

Fulwood v. Clemmer, 111 U.S.App.D.C. 184,

295 F. 2d 171 (D.C. Cir. 1961)................................. 49

Georgia, et al. v. Mitchell, et al., No. 265-70

(D.D.C.), appeal pending, No. 24,423,

D.C. App.................................................................. 14

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479

(1965)......................................................... 22,36,48,49

Harper v. Virginia Board o f Elections, 383 U.S.

663 (1966)................................................................. 50

Harrell v. Tobriner, 279 F. Supp. 22

(D.D.C. 1967)........................................ 48

Henry v. Clarksville Municipal Separate

School District, 409 F. 2d 682 (5th Cir.

1969)......................................................................... 15

Kwock Jan Fat v. White, 253 U.S. 454 (1920)............ 52

iv

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967).................... .... 30

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S.

637 (1950)................................................................. 5

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390

(1923)............................................... 22,27-28,37,41,42

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S.

337 (1938)................................................................. 4

Myers v. United States, 272 U.S. 52 (1926).............. 51

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 (1958).... 36-37

Northcross v. Board o f Education o f The

Memphis, Tennessee City Schools, 397 U.S.

232 (1970)......................... 46

Pierce v. Society o f Sisters, 268 U.S.

510 (1925)....................................................... 22,37,41

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960)............... 22,36

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

Dist., et al., 419 F. 2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969).......... 15

Social Security Board v. Nierotko, 327 U. S.

358 (1945)................................................................. 52

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950)....................... 5

Taylor v. Leonard, 30 N.J. Super. 116, 103 A.

2d 632 (1954)............................................................ 33

Todd v. Joint Apprenticeship Committee, 223 F.

Supp. 12 (N.D.I11. 1963)......................................... 49

Truax v. Raich, 239 U.S. 33 (1915)...................... 21,34

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970)...................... 18

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

v

United States v. The State o f Georgia, et ah,

Civil Action No. 12,972, N.D.Ga. (Order

filed Dec. 17, 1969).................................................. 16

United States v. Greenwood Municipal School

District, 406 F. 2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969)................ 15

United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate

School Dist., 410 F. 2d 626 (5th Cir. 1969).......... 15

United States v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, 380 F. 2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967).............. 14

United States v. Walker, 109 U.S. 258 (1883).......... 35

Windsor v. McVeigh, 93 U.S. 274 (1876).................. 35

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886)........... 23,51

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer,

343 U.S. 579 (1952)................................................. 50

Constitutional Provisions

U.S. Const. Art. IV, § 2, par. 1............................... 47

U.S. Const. Amend. 1..................................... 22,36,38

U.S. Const. Amend. V ................................... 22,47-49

U.S. Const. Amend. IX .................................. 47,49-50

U.S. Const. Amend. X ................................... 47,49-50

U.S. Const. Amend. XIV......... 3-5,26,29,42-43,47-48

Statutes

79 Stat. 911, 8 U.S.C. §§ 1151 et seq........................ 24

42 U.S.C. § 2000c(b).................................................... 44

42 U.S.C. § 2000c-6(a)................................................ 44

42 U.S.C. § 2000d........................................................ 45

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Miscellaneous

Page

1965 U.S. Code and Admin. News, pp. 3328-3354... 24

Alsop, “The Tragic Failure”, Newsweek,

Feb. 23, 1970........................................................... 6

Bickel, “Desegregation, Where Do We Go

From Here?”, The New Republic, Feb. 7,

1970, p. 20...................................... 32-33,40,42,46-47

Bickel, “The Supreme Court and the Idea of

Progress”, Harper & Row (Feb. 1970)............... .. 43

Perry, “Racial Imbalance and the Fourteenth

Amendment—Equal What?”, 52 A.B.A.

Journal 552 (1966)................................................... 43

Raspberry, “Concentration on Integration

is Doing Little for Education”, The

Washington Post, Fri., Feb. 20, 1970................... 6

The Atlanta Constitution, Vol. 103, No. 67

(Wed. Sept. 2, 1970)................................................ 18

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, “Racial

Isolation in the Public Schools”, 1967

Report......................................................... 6-10,53-54

U.S. Department of Health, Education and

Welfare, “HEW NEWS”, Jan. 4, 1970.............. 6

U.S. Department of Health, Education and

Welfare, “Revised Statement of Policies for

School Desegregation Plans Under Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964” (March

1966).................................................................... 11-12

U.S. Department of Health, Education and

Welfare, “Revised Statement of Policies for

School Desegregation Plans Under Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964” (Dec. 1966,

as amended for the school year 1967-68)............. 12

Vll

U.S. Department of Health, Education and

Welfare, “Policies on Elementary and

Secondary School Compliance with Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964” ......................... .. 12

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

viii

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1970

No. 420

CHARLES McDANIEL, et al.,

Petitioners,

-vs-

JOSEPH BARRESI, JR., et a l,

Respondents.

BRIEF OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA

AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA

The State of Georgia has many and varied interests in

the mental and physical development of its children, not

the least of which is that they become productive mem

bers of our multiracial, culturally variegated society. The

cynic may doubt the truth of this assertion. The con

cerned and knowledgeable observer will not. The impor

tance to the State of Georgia of a continually improv

ing rather than deteriorating program of public educa

tion would seem self-evident. As we will show, the State’s

ability to achieve this goal is in jeopardy.

1

2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Are attempts of the federal government to impose

racial exclusions (i.e., quota, percentage or balance re

quirements) upon pupils and teachers in Georgia’s pub

lic schools authorized by the Constitution and laws of

the United States?

2. Assuming arguendo that the answer to question

one is in the affirmative, are attempts to coerce racially

motivated exclusions nonetheless prohibited to the gov

ernment in that they violate transcendental countervailing

rights, privileges and immunities which the Constitution

and laws of the United States secure to the children, par

ents, teachers and public school districts of Georgia as

well as to the State itself?

3. Assuming arguendo that the federal government

is authorized by law to impose racial exclusions upon

pupils and teachers in the public schools, may it engage

in invidious sectional or geographic discrimination in its

exercise of this power—coercing only those children, par

ents and teachers who happen to reside in the Southern

States?

STATEMENT

(1) Nature of the Case.

Presented for decision is a case involving a local board

of education in Georgia which in response to the funds

termination power of the United States Department of

Health, Education and Welfare adopted racial ratios of

black 20% to 40% and white 80% to 60% in all but

two of the elementary schools within its jurisdiction.

This goal was to be attained by the exclusion of both

black and white pupils from the schools nearest their

homes or of their choice, solely on the basis of their race

3

or color, and by assigning these pupils, again solely

because of their race or color, to more distant schools—

not of their choice. In the two excepted schools, the bal

ance sought was 50% black and 50% white. It appears

that these exceptions were made in response to the

desire of citizens within the black community to main

tain some degree of racial identity in the two schools.

The plaintiffs below (here respondents) are both black

and white parents and children. Objecting to being ex

cluded solely for racial reasons from the schools they

desire to attend, they filed suit to enjoin implementation

of the local school board’s plan. Although it is not, in

our view of the case, material to the issues presented, we

note that each of the pupils either walks or is bused to

his (or her) school, depending upon its distance from

his (or her) place of abode. The Supreme Court of Geor

gia held that the racial exclusions were contrary to this

Court’s ruling in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of

Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969), that “no person is to

be effectively excluded from any school because of race

or color”. See Barresi v. Brown, President of the Clarke

County Board of Education, et al,, 226 Ga. 456, ____

S.E.2d ____ (1970). As we will show, the Supreme

Court of Georgia was correct.

(2) Statement of Facts.

The precise “holding” of Brown v. Board of Education1

was that State-enforced exclusion of black children from

a public school pursuant to State laws either “requiring

or permitting” segregation by race violated rights secured

to such children by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution. In the context of its express prohibition

x347 U.S. 483 (1954).

4

of State-enforced racial separation or segregation, there

is no doubt but that implementation of the decision has

been an unqualified success in those States generically

described as “the South”. Despite strong emotional as

well as intellectual opposition to Brown, the overwhelm

ing majority of Southern school officials have long since

come to accept the fact that State-enforced racial separa

tion is dead. These officials recognize that black children

have a personal, present and unqualified constitutional

right to be neither excluded from a particular school

because of their race nor required to attend a particular

school because of their race.

In Georgia, as in other Southern states, most school

districts sought to implement the newly defined “personal

right” through adoption of “freedom of choice” plans.

In essence, these plans gave each child’s parents the right

to choose the school their child would attend. While this

quite predictably resulted in most students electing to

attend schools in which their own particular race was in

the majority, it was generally thought that this normal

ethnocentric phenomenon was in no way inconsistent with

Brown. The existence of a truly free choice as to school

assignment was ipso facto considered to negate the pres

ence of State enforcement respecting the assignment. See

e.g., Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

Virginia, 345 F.2d 310, 313, 316-17 (4th Cir. 1965);

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F.Supp. 776 (E.D.S.C. 1955) [3

judge]. Under this concept of Brown, it is a personal right

which the Fourteenth Amendment protects. This view

is thoroughly consistent, of course, with the repeated

declarations of this Court that it is “the individual” who

is entitled to equal protection of the laws. E.g., Missouri

ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337, 351 (1938);

5

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 635 (1950). As stated

in McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637,

641 (1950):

“State-imposed restrictions which produce such in

equalities cannot be sustained.

It may be argued that appellant will be in no

better position when these restrictions are removed,

for he may still be set apart by his fellow students.

This we think is irrelevant. There is a vast differ

ence— a Constitutional difference— between restric

tions imposed by the state which prohibit the in

tellectual commingling of students, and the refusal

of individuals to commingle where the state presents

no such bar.” (Italics added)

But another view of Brown arose. This second view

was one which construed the underlying philosophy of

that decision not as the vindication of a personal right

of black students not to be subjected by the State to

racial segregation, but as a broad policy attack against

the very fact of racial separation, whether resulting from

personal choice, State compulsion or otherwise.2 It is this

view of Brown which the federal government has so

diligently sought to implement in Georgia and the various

other Southern States—while ignoring the fact of racial

separation elsewhere. For the South and the South alone,

the effort has been one of achieving racial quotas or bal

ance. If in fact and law this second view is the ultimate

mandate of Brown, it can only be said that while federal

officials may have achieved a certain degree of educa

2The particular alchemy by which the former personal constitu

tional “right” is converted into a personal constitutional “duty”

under the Fourteenth Amendment has never been explained.

6

tional disaster in the South, implementation has been an

abysmal failure nationally.3

The scope of the national failure to achieve, approach

or even hold even with this second (and we think de

based) view of Brown is well described by the govern

ment s own statistical releases. While the level of racial

integration in the public schools of Georgia and the

other Southern States has been forced upwards, the

national trend has for the most part been in exactly the

opposite direction, i.e., towards increased racial separa

tion. The most recent statistical information released by

the United States Department of Health, Education and

Welfare (January 4, 1970) shows that by the Fall of

1968, the national level of racial separation in the public

schools had risen to the point where only 23.4 percent

of black pupils enrolled in the Nation’s public schools

were attending schools with a predominantly white enroll

ment, and further shows that fully 61 % of the country’s

black pupils were enrolled in almost totally (95 to 100

percent) black schools.4

Nor can this Nation-wide trend be said to be “newly

discovered”. Discussing the great increase in racial segre

gation in the public schools of 15 selected Northern

cities5 between 1960 and 1965, the 1967 report of the

8The totality of the failure has been increasingly recognized by

writers, both black and white, who have long been associated

with the furtherance of Civil Rights. See e.g., Stewart Alsop, “The

Tragic Failure”, Newsweek, Feb. 23, 1970; William Raspberry,

“Concentration on Integration is Doing Little for Education”,

The Washington Post, Friday, Feb. 20, 1970.

“See U. S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare “HEW

NEWS”, Jan. 4, 1970.

^Cincinnati; Milwaukee; Pasadena; Philadelphia; Pittsburgh; In-

7

United States Commission on Civil Rights entitled

“Racial Isolation in the Public Schools” noted at p. 8:

“Eighty-four percent of the total Negro increase in

these 15 city school systems was absorbed in schools

that are now 90-100 percent Negro, and 94 percent

in schools more than 50 percent Negro. In Cin

cinnati, Ohio, the Negro elementary school enroll

ment doubled over the last 15 years, but the num

ber of Negro children in majority-Negro schools

almost tripled. In 1950, 7 of every 10 Negro ele

mentary school children in Cincinnati attended ma

jority-Negro schools. In 1965, nearly 9 of 10 did.

In Oakland, Calif., almost half of the Negro ele

mentary school children were in 90-100 percent

Negro schools in 1965. Five years earlier, less than

10 percent were. During the 5-year period, Negro

elementary school enrollment increased by 4,100

but the number of Negro students in 90-100 percent

Negro schools increased by almost 8,000.”

The exact increases in percentages of black pupils attend

ing almost all (90 to 100 percent) black schools and

dianapolis; Cleveland; Oakland; Detroit; Buffalo; San Francisco;

Chester; Harrisburg; Springfield, Massachusetts; and New Haven.

8

predominantly black schools in the specified Northern

cities were set forth by the Report as follows:

C ity Y e a r

90-100%

N egro

E n ro ll

m en t

M ajo rity -

N eg ro

E n ro ll

m en t Y e a r

90-100%

N egro

E n ro ll

m en t

M ajo rity -

N eg ro

E n ro ll

m en t

Cincinnati _ —1950 43.7 70.7 1965 49.4 88.0

Milwaukee .-1 9 5 0 51.2 66.8 1965 72.4 86.8

Pasadena _ -1 9 5 0 0.0 26.2 1965 0.0 71.4

Philadelphia -1950 63.2 84.8 1965 72.0 90.2

Pittsburgh __-1 9 5 0 30.4 51.0 1965 49.5 82.8

Indianapolis -1951 83.2 88.2 1965 70.5 84.2

Cleveland ...__1952 57.4 84.4 1962 82.3 94.6

Oakland _ -1 959 7.7 71.1 1965 48.7 83.2

Detroit _ .I960 66.9 91.1 1965 72.3 91.5

Buffalo ___ -1961 80.5 89.4 1965 77.0 88.7

San Francisco 1962 11.6 75.8 1965 21.1 72.3

Chester __ -1963 71.1 85.8 1965 77.9 89.1

Harrisburg _

Springfield,

-1963 58.1 82.7 1965 54.0 81.3

Mass. ... -1963 0.0 58.8 1965 15.4 71.9

New Haven -1963 22.5 71.0 1965 36.8 73.4

As for the other side of the racial polarization, the Re

port showed that the bulk of the white pupils were being

permitted to attend virtually all (90 to 100 percent) white

schools. It showed the following percentages respecting

enrollment of the white pupils in 90 to 100 percent white

schools:

Cincinnati _________ 63.0%

Milwaukee _________ 86.3%

Pasadena __________ 82.1%

Philadelphia________ 57.7%

Pittsburgh____ ________62.3 %

Indianapolis________80.7%

Cleveland________ 80.2%

Oakland ___________ 50.2%

Detroit ____________ 65.0%

Buffalo __________— 81.1%

San Francisco ___ — 65.1 %

Chester ________ -3 7 .9 %

Harrisburg ______ -5 6 .2 %

Springfield, Mass__ __82.8%

New Haven - ___ -4 7 .1 %

The pattern of increasing racial separation, isolation

9

or segregation within these particular Northern cities was

found by the United States Commission on Civil Rights

to be typical of Northern school districts. The Report

pointed out that by the 1965-66 school year fully 89.2

percent of Chicago’s black students were attending vir

tually all (90 to 100 percent) black schools while at the

same time 88.8 percent of the city’s white pupils were

being permitted to attend virtually all (90 to 100 per

cent) white schools. Statistics for some of the other

Northern cities, as set forth at pp. 4-5 of the Commis

sion’s report, showed the following situation by 1965:

City

% of Negro Pupils in 90-100% Negro Schools

% of Negro Pupils Majority Negro Schools

% of White Pupils in 90-100% White Schools

Richmond, Calif. ______ ___ 32.9 82.9 90.2

San Diego, Calif. _ ___ 13.9 73.3 88.7

Denver, Colo. .. _ _ _____ 29.4 75.2 95.5

Hartford, Conn. ____ ___ 9.4 73.8 66.2

New Haven, C onn.____ ___„ 36.8 73.4 47.1

East St. Louis, 111. .. _ . . ___ 80.4 92.4 68.6

Fort Wayne, Ind. _ . . ___ 60.8 82.9 87.7

Gary, Ind. ____________ ___ 89.9 94.8 75.9

Wichita, Kans.__ ___ 63.5 89.1 94.8

Baltimore, Md. _______ ___ 84.2 92.3 83.8

Boston, Mass. _______ ___ 35.4 79.5 76.5

Flint, M ich.___ ______ ___ 67.9 85.9 80.0

Minneapolis, Minn. ____ ____ None 39.2 84.9

Kansas City, Mo. __ - ___ 69.1 85.5 65.2

St. Louis, Mo. ____________ 90.9 85.5 65.2

Omaha, Neb. _ ___ _ ____ 47.7 81.1 89.0

Newark, N. J. ______ ___ 51.3 90.3 37.1

Camden, N. J . __ ____ ___ 37.0 90.4 62.4

Albany, N. Y. ______ _______ None 74.0 66.5

New York, N. Y_______ _ _ 20.7 55.5 56.8

Columbus, Ohio ____ ____ 34.3 80.8 77.0

Tulsa, Okla___________ ___ 90.7 98.7 98.8

10

C ity

(C o n t’d .)

% o f N eg ro

P u p ils in

90-100%

N egro

Schools

(C o n t’d .)

% o f N eg ro

Pup ils

M ajo rity

N eg ro

Schools

(C o n t’d .)

% o f W hite

P up ils in

90-100%

W hite

Schools

(C o n t’d .)

Portland, O re ._____ - 46.5 59.2 92.0

Providence, R. I . ___ - 14.6 55.5 63.3

Seattle, W ash._____ 9.9 60.4 89.8

Washington, D. C .__ __ 90.4 99.3 34.3

The Report concluded at p. 6:

“Nor does the pattern necessarily vary according to

the proportion of Negroes enrolled in the school

system. For example, Negroes are 26 percent of the

elementary school enrollment in Milwaukee, Wis.,

and almost 60 percent of the enrollment in Phila

delphia, Pa., yet in both cities almost three of every

four Negro children attend nearly all-Negro schools.

Negroes are 19 percent of the elementary school

enrollment in Omaha, Nebr., and almost 70 per

cent of the enrollment in Chester, Pa., yet in both

cities at least 80 percent of the Negro children are

enrolled in majority-Negro schools.”

Noting that during the time covered by its study (i.e.,

primarily before 1966 and the start of federal official

dom’s intensive efforts to impose racial quota and racial

balance requirements upon Southern school districts) the

level of racial separation was only slightly higher in the

South, the Commission concluded at p. 7 of its Report:

“The extent of racial isolation in Northern school

systems does not differ markedly from that in the

South.”

Due to the lop-sided efforts of the Justice Department

and HEW, the Commission’s conclusion of substantial

similarity between Northern and Southern school systems

has become wholly inaccurate. While the general dearth

of black pupils in many Northern systems may tend to

give misleading statewide figures, examination of rec

11

ords of the federal government respecting those Northern

school systems which do have any appreciable number

of black students clearly demonstrates that these systems

have far higher levels of racial separation, isolation and

segregation than federal officials have ever been willing

to tolerate in Georgia and other States in the South.

Intensification of the disparity of treatment between

Northern and Southern school systems respecting racial

quota and racial balance requirements began at least as

early as 1966. In that year, HEW, apparently unhappy

over the way in which black parents and pupils in the

South were exercising their “freedom of choice”, decided

to limit the use of such plans. It decided that henceforth

these plans would be acceptable only if the choices were

exercised in the way in which HEW officials thought they

should be exercised. The March 1966 “Guidelines for

School Desegregation” commenced HEW’s march to

wards racial quota or balance requirements as a requisite

for continued federal financial assistance. The guidelines

announced:

“The single most substantial indication as to

whether a free choice plan is actually working to

eliminate the dual school structure is the extent to

which Negro or other minority group students have

in fact transferred from segregated schools. . . .

Where a free choice plan results in little or no actual

desegregation, or where, having already produced

some degree of desegregation, it does not result in

substantial progress, there is reason to believe that

the plan is not operating effectively and may not be

an appropriate or acceptable method of meeting con

stitutional or statutory requirements.”6

6See U. S. Department of HEW, “Revised Statement of Policies

for School Desegregation Plans Under Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964”, (March 1966).

12

HEW indicated that it would be satisfied with the “prog

ress” of local school systems only if:

(1) school districts which had at least 8 or 9 percent

of their pupils transfer under such a plan during

the 1965-66 school year at least doubled the per

centage during the 1966-67 school year,

(2) school districts which had only 4 or 5 percent of

their pupils transfer under such plans during the

1965-66 school year at least tripled the percent

age during the 1966-67 school year, and

(3) school districts having a lower percentage of

transfers achieved a proportionately greater rate

of increase for the 1966-67 school year.* & 7

The “guidelines” went on to say that if a “freedom of

choice” plan did not produce results satisfactory to HEW

(i.e., sufficient racial balance) it might “require the

school system to adopt a different type of desegregation

plan”. The racial quota requirements of the March 1966

guidelines were continued in the December 1966 guide

lines for the 1967-68 school year.8

In March 1968, the United States Department of

Health, Education and Welfare published its “Policies

on Elementary and Secondary School Compliance with

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964”. There HEW

announced that in order to continue to receive federal

financial assistance, school districts (meaning, of course,

7Ibid.

&U. S. Dept, of HEW, “Revised Statement of Policies for School

Desegregation Plans Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964”, (Dec. 1966, as amended for the School Year 1967-68).

13

Southern school districts only) would have to “bring

about an integrated unitary school system . . . so that

there are no Negro or other minority group schools and

no white schools. . . .” The deadline was the 1968-69

school year or, at the latest, the 1969-70 school year.

Nor was there any doubt as to the fact that under the lexi

con of HEW “integrated unitary school system” meant

racial balance or at least a reasonable likeness thereof.

According to HEW, Southern school systems were to be

expected to go beyond freedom of choice and to accept

the pairing of schools, closing of schools, reassignment of

pupils, and the redrafting of geographic attendance zones

to maximize affirmative integration (or, in other words,

racial balance).

While HEW was in this manner compelling local

school systems in Georgia and other Southern States to

accept racial quotas and balance requirements as a con

dition of continued federal financial assistance, the De

partment of Justice occupied itself by seeking judicial

sanction for its “special treatment” for Southern school

systems and pupils. Between enactment of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 and January 1, 1970, the Justice

Department initiated or otherwise participated in almost

200 legal actions to compel integration in at least 400

local school districts within the 11 States of the South.9

Twenty-six of these suits (involving approximately 107

local school systems) were filed within the State of Geor

9Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi,

North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia.

Two of the suits were filed on a statewide basis. One, in Alabama,

affected 100 local school districts while the other, against the

State of Georgia, affected 81 local school districts. Other cases

similarly have involved a multiplicity of school district defendants.

14

gia alone. In all of the remaining 39 States of the Union,

the Department of Justice has seen fit (as of January 1,

1970) to file or otherwise participate in actions against

only 8 local school districts.10

The Justice Department’s initial success in converting

the personal constitutional right of a pupil not to be ex

cluded from a school or required to attend a school

solely because of his race into a duty to accept exclusion

or assignment for precisely this reason (i.e., his race)

was achieved in United States v. Jefferson County Board

of Education, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967) [en banc].

There, for the first time, the Justice Department per

suaded a majority of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit, at least insofar as Southern schools and pupils

were concerned, to abandon the concept of Brown as a

protection of personal rights of the governed from gov

ernmental interference. The new rule was one of Federal

power and individual duty. A majority of the Court of

Appeals for this Circuit even went so far as to deny that

freedom of individual choice was a valid constitutional

goal! By dicta, it approved the percentage guidelines or

racial quotas established by HEW. As the dissenting opin

ions so correctly foresaw and so forcefully pointed out,

Jefferson’s disclaimer of any “racial balance” requirement

was naught but window dressing. The untimely (al

though we hope temporary) end at the hands of Jefferson

of those personal rights and freedoms born of Brown is

now a matter of public record and common knowledge.

Within two years after Jefferson, the Fifth Circuit was

saying:

“ “Defendants’ Answers to Certain of the Mitchell Interrogatories”,

filed in Georgia, et al. v. Mitchell, et al., Civil Action No. 265-70

(D.D.C.), appeal pending, U.S. Court of Appeals for the District

of Columbia Circuit, No. 24423.

15

. . we are firm that a point has been reached in the

process of school desegregation ‘where it is not the

spirit, but the bodies which count’.” United States

v. Indianola Municipal Separate School Dist., 410

F.2d 626, 631 (5th Cir. 1969).

“The transformation to a unitary system will not

come to pass until the board has balanced the fac

ulty of each school. . . .” United States v. Green

wood Municipal School District, 406 F.2d 1086,

1094 (5th Cir. 1969).

“If there are still all-Negro schools, or only a small

fraction of Negroes enrolled in white schools, or

no substantial integration of faculties and school

activities, then, as a matter of law, the existing plan

fails constitutional standards. . . . The board should

consider .. . closing all-Negro schools, consolidating

and pairing schools, rotating principals, and taking

other measures. . . .” Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal

Separate School District, 409 F.2d 682, 689-90 (5th

Cir. 1969).

As a result of this “southern strategy”, the imposition of

racial quota and racial balance requirements has with

but a few exceptions11 become the pattern within the

Fifth Circuit. Singleton, et al. v. Jackson Municipal Sep

arate School District, et ah, 419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir.

1969), ordered a mid-term reassignment of teachers so

that as of February 1, 1970, the ratio of black to white

teachers in each school would be the same as existed

within the entire school system. It was further ordered

that student bodies be merged “into unitary systems” by

11In Ellis v. The Board of Public Instruction of Orange County,

Florida, 423 F.2d 203, 208, 213-16 (5th Cir. 1970), a neigh

borhood school attendance system was upheld notwithstanding the

existence of all-Negro schools in a predominantly white school

system..

the Fall of 1970. A district court which held on January

21, 1970, that nothing in the Constitution required racial

balance of pupils within the public schools was sum

marily reversed by the Fifth Circuit on February 5,

1970.12 As a result of litigation instituted by the federal

government directly against the State of Georgia and the

State Board of Education, all State school funds were

ordered to be withheld from some 81 local school systems

within Georgia unless such school systems agreed to the

implementation of judicially specified racial quotas. See

United States v. The State of Georgia, et al., Civil Action

No. 12972, N.D. Ga. (Order filed Dec. 17, 1969).

The demoralizing disruption of the educational process

in Georgia and in the other Southern States subjected to

the discriminatory actions of these federal officials has

long been obvious to all who can see and are willing to

see. Massive transfers of teachers and pupils have been

and are being required without the slightest regard for

established teacher-pupil relationships, without the slight

est regard for the location of schools and distances to be

traveled, without the slightest regard for curricula needs

and desires, and without the slightest regard for the

individual pupil or teacher and his personal friendships

and attachments. Is it at all surprising that about 40%

of the State’s county and municipal school superinten

dents have departed from their offices over the past two

years? Does this loss of administrative experience some

how further equal educational opportunity?

Nor can the damage to public education in the South

12Bivins, et al. v. Board of Public Education and Orphanage for

Bibb County, et al., No. 1926 (M.D. Ga., Order filed Jan. 21,

1970), rev’d. sub nom, Bivins v. Bibb County Board of Educa

tion, 424 F.2d 97 (5th Cir. 1970).

17

be disregarded upon the highly questionable theory that

it is only transitory wreckage during an “adjustment pe

riod”. How does one calculate the loss of a single com

petent teacher who forever departs from his chosen pro

fession rather than accept transfer from a school near

his residence to a more distant facility? The number of

experienced teachers who have departed from the school

systems in which they had been teaching is already sub

stantial. Evidence indicates that an even larger number

will depart during the current school year. Other teach

ers, forced by economic circumstances to remain in the

school system, become disheartened upon finding them

selves not only in a new school, but forced to teach out

side the area of their particular competency and choice.

Overlooked in the shuffle to achieve racial balance of

faculty in each school has been the detail that no cor

relation whatsoever is apt to exist between the system-

wide racial composition of faculty and the black-white

ratio for French teachers, science teachers, math teach

ers, remedial instruction teachers, etc.

Perhaps one of the most lasting of all injuries to public

education, an injury which may indeed prove fatal to

public education in some areas of Georgia, is the change

of attitude of those who ultimately foot the bill for its

continuance. Along with parents and pupils, the general

public, regardless of race, has become quite disenchanted

with a system of public education which takes funds

which could be utilized for direct educational expendi

tures, as for books and teachers’ salaries, and requires

them instead to be expended to transport children to more

distant schools in order to receive racially balanced in

struction from a newly transferred teacher who very

likely is teaching an unfamiliar subject and thoroughly

18

unhappy about her transfer in the first place. Nor does

the general citizenry appreciate the social value of clos

ing perfectly adequate (not to mention expensive) school

facilities in one place in order to spend hundreds of thou

sands of dollars more for the construction of new facili

ties elsewhere just because someone thinks (usually er

roneously) that more racial integration will result.13 The

dangerous decline of public support for public education

renders the defeat of proposed school bond issues at the

polls more likely and can cause intense opposition to any

increase in taxation for public education. Another omin

ous aspect of public disenchantment with public educa

tion is seen in the sharp increase of actual withdrawal

from the public schools. In Taliaferro County, Georgia,

for example, the government’s efforts resulted in each

and every white teacher and each and every white pupil

withdrawing from the public school system of that county

in favor of either the newly created private schools within

the county or public schools elsewhere. See Turner v.

Fouche, 396 U.S. 346, 349 (1970). Preliminary Fall

1970 enrollment figures for the Atlanta public schools

indicate that some 6,000 pupils have withdrawn

from this school system, and similar figures for Bibb

County (Macon), Georgia indicate that that system has

lost 4,000 students. The Atlanta Constitution, Vol. 103,

No. 67 (Wed., Sept. 2, 1970). Particularly ominous is

the fact that it is generally the children of middle and up

13When, due to the government’s racial balance pressures, the

Fulton County (Georgia) school system closed the all-black Eva

Thomas school in order to transfer its pupils to more distant

predominantly white schools, a massive sit-in by black students

developed. It ended when the Eva Thomas school was at least

temporarily reopened with judicial approval. Then too, people

often vote with their feet.

19

wards economic and social backgrounds who first de

part. It is this segment of society which traditionally has

been the pillar of local moral and financial support for

public education.

Needless to say, the wreckage which thoughtless fed

eral officials have inflicted upon public education in Geor

gia has caused incalculable injury to the State itself as

well as to its citizenry. Hundreds of thousands if not mil

lions of State supplied dollars have been lost through the

pressured closing of adequate school facilities. The les

sening of Georgia’s ability to provide a sound program

of public education for its youth, in addition to irrepar

able injury to those pupils who are unable to afford ade

quate private instruction, adversely affects the State’s

competitive position respecting the areas in favor of

which federal officials discriminate. Other things being

equal, industry will prefer to expand to those states which

have not had their educational systems dismantled by the

government.

Yet as destructive of public education as racial quotas

and balance requirements are, as unsatisfactory as they

have proven to be to reduce rather than increase racial

polarization and animosity, we reluctantly could ac

cept this punishment if it were to be inflicted equally

upon all sections of the Nation—North as well as South.

As of now this most demonstrably has not been the

case. Nor will it ever become the case if this Court does

not take action to end the existing disparity of treatment.

The most recent statistics available from the United States

Department of Health, Education and Welfare respect

ing the high but still increasing level of racial segregation

in Northern school systems well illustrate that although

the War Between the States ostensibly ended over 100

20

years ago, there continues to be one set of “guidelines”

for the South and quite another for the rest of the Nation

—one rule for the conquerer and one for the conquered.

While we doubt that anyone disputes the national scope

of racial separation in public education, we have set

forth specific examples, taken from HEW’s most recent

statistics, in our appendix to this brief. We respectfully

refer the Court to the same, thinking that it is worth

looking at these few examples of the inordinately high

levels of apartheid which have been achieved in Northern

school systems without any noticeable interference by the

same federal officials who have been so active in the

derogation of meaningful public education in so many

areas of Georgia and the other Southern states.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954),

held that a black child cannot be excluded from one

school and required to attend another school solely be

cause of his race. All too many governmental officials

have misconstrued Brown to require that black and white

children must be excluded from one school and required

to attend another solely because of their race (i.e., to

meet racial quota or balance goals).

The situation might be likened to the invalidating of

laws requiring black citizens to sit in the rear of a bus.

A great many governmental officials are in the position of

insisting that the decision requires black and white pas

sengers to be seated according to a percentage or quota

system so as to enforce a uniform racial distribution

throughout the bus. We object to the government’s con

version of a personal right into a personal duty just as

21

we would object to its equating a citizen’s right of re

ligious freedom with a duty to go to church.

The evil is magnified when obeisance to a particular

dogma is demanded only of those citizens of the United

States who happen to reside in the South.

While we think that the nature of our argument causes

attempts to summarize it almost inevitably to result in

oversimplification, we would state its principal thrust as

follows: Racial quota, percentage or balance require

ments are among the most obvious of racial exclusions.

An “at least” for one race is a “not more than” for the

others. Quota and percentage requirements based upon

race are necessarily “a guaranty of inequality of treat

ment of eligible ‘persons’ ”, Banks v. Housing Authority,

120 Cal.2d 1, 260 P.2d 668, 673-74 (1953), and have

been uniformly condemned by the courts. See, e.g. Truax

v. Raich, 239 U.S. 33, 42-43 (1915); Colon v, Tomp

kins Square Neighbors, Inc., 294 F.Supp. 134, 139

(S.D.N.Y. 1968).

In the field of public education, we read Brown, and

more recently, Alexander v. Holmes County Board of

Education, 396 U.S. 19, 20 (1969), as prohibiting State-

imposed racial exclusions absolutely and without regard

to their form. But whether or not we are correct in this

view, and whether or not the latter case meant what it

said and said what it meant when it defined the consti

tutional requisite as a school system:

“within which no person is to be effectively ex

cluded from any school because of race or color”,

we think that constitutional analysis, in the light of many

other of this Court’s past decisions, impels the conclusion

that racial quota, percentage or balance requirements are

22

as much at war with the Constitution as they are with

human dignity and those basic moral foundations upon

which we hope our Nation rests. To start with, we think

that the federal government lacks any power whatsoever

to establish racial quotas for children and teachers in the

public schools. This sort of activity simply is not a means

which can be said to be reasonably related to the further

ance of any legitimate governmental end or purpose. As

we show in our argument, the activities in question ac

tually negate rather than further the legitimate govern

mental goal (recognized in Brown) of equal educational

opportunity. In some instances the racial exclusions

coerced by federal officials actually serve to guarantee

non-education for the poor.

Moreover, even were it to be assumed, arguendo, that

racial exclusions in the form of quota and balance re

quirements did reasonably relate to furtherance of the

legitimate governmental end of equal educational oppor

tunity, such exclusions are nonetheless prohibited by the

Constitution because they are an oversweep in remedy,

see e.g. Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479, 488 (1960);

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479, 485 (1965).

They violate transcendental countervailing rights, privi

leges and immunities secured to parents, pupils and

teachers by the First and Fifth Amendments. The rights

in question have been well defined by this Court in such

cases as Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624,

637, 640-41 (1942); Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268

U.S. 510, 534-35 (1925); and Meyer v. Nebraska, 262

U.S. 390, 399-403 (1923); as well as again more re

cently in Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97, 105-106

(1968).

We agree that State-compelled racial separation is

23

dead. We do not think, however, that the corpse should

be replaced with a procrustean bed of uniform racial

balance, which in many areas already threatens public

education with loss of vitality if not of life. Other options

are available. The ability of local school systems to inno

vate and experiment ought not to be foreclosed in favor

of the same moribund uniformity of educational doctrine

(this time it is racial balance) which this Court con

demned in Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624,

640-41 (1942).

Finally, in the event the Court disagrees with our view

that racial exclusions are prohibited by the Constitution

regardless of their form or purpose, we urge it to ter

minate the invidious sectional discrimination which has

until now permeated federal enforcement. Surely regional

bigotry is as offensive as racial bigotry. How long is the

“conquered province” approach to continue? The existing

situation, aptly termed a “monumental hypocrisy” by

Senator Ribicoff of Connecticut, is well documented by

the government’s own records, reports and statistical re

leases—to which we have referred in our fact statement.

It is a national scandal for which judicial correction has

long been overdue. There can be no such thing as true

constitutional government in the United States if the laws

of the land mean one thing in Georgia and another in

Ohio. If children and teachers must be prodded about to

achieve racial balance in Charlotte, North Carolina or

Athens, Georgia, what moral or constitutional justifica

tion could possibly exist to ignore the situation in Cleve

land, Chicago, and New York? This Court has not hesi

tated to strike far lesser discriminations in the past. E.g.

Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 373 (1886); Dob

bins v. Los Angeles, 195 U.S. 223, 240 (1904). We im-

24

plore the Court to point out once again that there is but

one Constitution for all citizens and that children who

happen to reside in Georgia also are entitled to its pro

tection.

ARGUMENT

1. GOVERNMENTAL ATTEMPTS TO IMPOSE

RACIAL EXCLUSIONS (i.e. QUOTA, PERCENT

AGE, OR BALANCE REQUIREMENTS) UPON

PUPILS AND TEACHERS IN GEORGIA’S PUB

LIC SCHOOLS ARE UNAUTHORIZED BY THE

CONSTITUTION AND LAWS OF THE UNITED

STATES IN THE FIRST INSTANCE, BUT IN

ANY EVENT ARE PROHIBITED IN THAT

THEY VIOLATE TRANSCENDENTAL RIGHTS

SECURED TO CHILDREN, PARENTS, TEACH

ERS AND THE STATE ITSELF UNDER SAID

CONSTITUTION AND LAWS.

Persons concerned with human dignity have almost

universally looked upon quota or percentage require

ments based upon race with revulsion. The unsavory

practice of some colleges of establishing quotas for the

admission of certain religious minorities, the subject of

heated debate in the ’30s and ’40s, is for the most part

but an unpleasant memory today. More recently, the

inherently arbitrary and discriminatory nature of ethnic

and racial quotas has led to drastic revision of our Na

tional Immigration Laws so as to eliminate their con

sideration in determining who shall be admitted into the

country. See, 79 Stat. 911, 8 U.S.C. §§ 1151 et seq;

1965 U. S. Code and Admin. News, pp. 3328-3354.

Needless to say, it matters not whether the quota or

25

percentage is cast in terms of “at least” or “not more

than”. One quite necessarily includes the other.14

We think it obvious that the question of whether these

roundly condemned racial quotas or percentages can be

constitutionally imposed by governmental authority in the

field of public education requires two related yet dif

ferent inquiries. Inasmuch as the federal government and

its officers are possessed of but limited powers under our

federal system, the first inquiry must be whether under

the Constitution and laws of the United States the federal

government legally is empowered to take any action at all

respecting racial quota or percentage exclusions in the

public schools. Then, assuming that the federal govern

ment does have power to act in the matter, we must look

to see whether there exist limitations upon its exercise

by way of transcendental countervailing rights, privileges

or immunities secured to parents, pupils and teachers

under the Constitution and laws of the United States. In

a somewhat analogous situation involving a compulsory

salute to the flag,15 this Court explained in Board of Edu

cation v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624, 635 (1942) :

“It is not necessary to inquire whether nonconform

ists beliefs will exempt from the duty to salute unless

we first find power to make the salute a legal duty.”

14An “at least” for one race is a “not more than” for the other.

Hence a racial quota, percentage, number or balance requirement

is one of the clearest possible forms of racial exclusion. It also is

rather important to note that the race which is the majority varies

from school district to school district.

15Here the federal government seeks to compel school assign

ments based wholly on race in order to achieve racial balance or

quotas.

26

(a) The government of the United States is without

legal authority to impose racial exclusions by coercing

school attendance in such manner as to achieve any

particular balance, quota, number or percentage re

quirement for a given race in a given school.

It must be emphasized that we do not attack the

holding of Brown that State-enforced segregation ac

cording to race is violative of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. To the extent that it is a vindication of the

present and unqualified constitutional right of a pupil to

be neither excluded from nor forced to attend any par

ticular school solely because of his race, we indeed insist

upon Brown. It is exactly this right which the federal gov

ernment denies. The situation may be likened to the in

validating of a law requiring a black citizen to sit in the

rear of a bus. We do not in the least object to the sub

stitution of a personal right and freedom (to sit any

where) in place of his former duty and obligation (to sit

in the rear). To the contrary, we insist upon this per

sonal right and freedom. What we object to is the bus

conductor seizing the body of any black citizen who

happens to choose a seat in the rear and dragging him

forward against his will to compel him to sit beside some

one just because the someone is white. We strenuously

object to this conversion of the black citizen’s newly

acquired constitutional right and freedom into a govern-

mentally imposed duty.

In attempting to fathom the claimed legal basis (if

any) for any governmental official’s self-asserted power

to deny individual freedom and liberty to both black

and white pupils and teachers respecting school assign

ment (apparently upon a “democracy doesn’t work”

theory) and substitute in its place a duty on the part of

individuals of both races to submit to such racial quota,

27

percentage, or number requirements as the federal official

may from time to time deem appropriate, it would seem

that the approach sanctioned by this Court is to define

first the governmental purpose or objective to be served,

which must itself be legitimate, and then, in light of this

purpose or objective, to examine the means to see if

they are appropriate and reasonably related to attainment

of the goal. Particularly is this so where as here the

selected means constitutes an obvious deprivation of in

dividual liberty. In a similar setting of attempted govern

mental restraint upon parental rights and liberties re

specting their children’s education, Meyer v. Nebraska,

262 U.S. 390, 399-400 (1923), this Court explained:

“The established doctrine is that this liberty may

not be interfered with, under the guise of protecting

the public interest, by legislative action which is

arbitrary or without reasonable relation to some pur

pose within the competency of the State to effect.”

In Meyer, the governmental purpose had been defined as

the desire for unity and the development of a more

homogeneous people who would be imbued with Amer

ican ideals. To this end Nebraska adopted as its means

a statute prohibiting the teaching of a foreign language

to any child prior to his completion of the eighth grade

[the thought being that this would provide a common

cultural base by making English the mother tongue of

all]. While the Court agreed that it might be highly

advantageous if everyone had a ready understanding of

our ordinary speech, it pointed out in no uncertain terms

that even this presumably valid legislative end did not

justify a means which resulted in the deprivation of per

sonal freedom. It rejected the means chosen by Nebraska.

At 262 U.S. 403, the Court said:

28

“No emergency has arisen which renders knowledge

by a child of some language other than English so

clearly harmful as to justify its inhibition with the

consequent infringement of rights long freely en

joyed. We are constrained to conclude that the stat

ute as applied is arbitrary and without reasonable

relation to any end within the competency of the

State.”

The Meyer principle of rejecting undue restrictions upon

the liberty of teachers and pupils was quite recently re

affirmed in Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97, 105

(1968).

Looking first to what valid governmental purpose or

objective racial quota requirements are supposed to serve,

we obviously must start out by rejecting such cant as

“necessity of dismantling the dual school system” and the

acceptability of desegregation plans only if “they work”.

Such semantical shibboleths, aside from the fact that they

obfuscate rather than clarify, utterly fail to answer “why”

and hence, like the terms “desegregation” and “inte

gration” themselves, are really concerned only with the

“means”. While they sometimes are, they really ought

not to be confused with (much less equated with) the

ultimate governmental purpose or objective to be served.

In defining just what the legitimate governmental goal

is, it is perhaps best to return to the taproot of the entire

question, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954). In speaking of the inherent inequality of edu

cational opportunity when students are compelled by law

to attend racially segregated schools, it appears to be

quite clear that this Court viewed the primary vice of

such legally-enforced apartheid to be the psychological

effect upon the hearts and minds of black pupils. The

Court said at 347 U.S. 494:

29

“To separate them from others of similar age and

qualifications solely because of their race generates

a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the com

munity that may affect their hearts and minds in a

way unlikely ever to be undone. The effect of this

separation on their educational opportunities was

well stated by a finding in the Kansas case by a

court which nevertheless felt compelled to rule

against the Negro plaintiffs:

‘Segregation of white and colored children in

public schools has a detrimental effect upon the

colored children. The impact is greater when it has

the sanction of the law; for the policy of separating

the races is usually interpreted as denoting the in

feriority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority

affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segrega

tion with the sanction of law therefore, has a ten

dency to [retard] the educational and mental de

velopment of negro children and to deprive them

of some of the benefits they would receive in a

racial [ly] integrated school system.’ Whatever may

have been the extent of psychological knowledge at

the time of Plessy v. Ferguson, this finding is amply

supported by modern authority.”

The rationale of Brown, in other words, was that

State-compelled segregation according to race engendered

feelings of inferiority in the black student which pre

cluded the possibility of “equal educational opportunity”.

It is, in other words, “equal educational opportunity”

which is the right protected by the Fourteenth Amend

ment. It is the protection or furtherance of this right

which is ipso facto the legitimate goal or purpose of the

Federal government. Subsequent decisions of the Court

have continued to demonstrate that in protecting this

personal right it is the harmful effect of State compul

sion (and not the consequences of individual freedom

30

of association) which is the proper object of govern

mental attack. In Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 10

(1967), it was said:

“The clear and central purpose of the Fourteenth

Amendment was to eliminate all official state sources

of invidious racial discrimination in the States.”

(Italics added)

Similarly, in one of its most recent decisions concerning

school desegregation, the Court again stated the matter

in terms of State-enforced racial separation when in

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19, 20 (1969), it referred to the termination of a

dual school system and coming into being of a unitary

system as the point where the system is one:

“within which no person is to be effectively excluded

from any school because of race or color.”

We do not dispute the fact that racial quota, percent

age and balance requirements constitute a means of

eliminating this constitutionally impermissible barrier

(State-compelled segregation) to the legitimate govern

mental goal of equal educational opportunity. But the

test is not whether the means removes a barrier to the

end. It is achievement of the end itself to which the

means must be appropriate and reasonably related. A

means which merely supplants the old impediment with

a new one does not necessarily bring the goal closer.

The precise question to be answered is whether the racial

exclusions currently coerced by governmental officials (in

the form of racial quota, percentage or balance require

ments) are appropriate and reasonably related to the

legitimate governmental goal of “equal educational op

portunity”.

In answering this question, it is perhaps appropriate

31

that we first pause to consider just what “equal educa

tional opportunity” is. A simplistic answer, of course,

is that each and every child, regardless of background

and desires, regardless of whether he is mentally retarded

or a child prodigy, must receive exactly the same educa

tion. Yet we doubt that anyone in this or any related case

will argue in favor of this equality of input and devil

take the hindmost approach to public education. More

likely we will find a rather general agreement that the

ultimate goal of public education is to make available

to each child (a highly individual and complex being)

that variety and degree of learning which he needs, de

sires, and is capable of absorbing. Looking at “equal edu

cational opportunity” in the light of this goal (which we

assume to be quite generally accepted), we see that

uniformity of educational treatment is in fact the anti

thesis of “equal educational opportunity”. One of the

advantages of open enrollment, for example, is the very

fact that schools can differ, that they can have varying

curricula and standards which can be designed to meet

the particular needs and desires of the children who

choose to attend each particular school. Needless to say,

this progressive approach to education is completely

ruled out where the school assignments are made on a

racial basis rather than upon the students’ needs, desires

and aptitudes.

For this reason among others we think that the cor

rect answer to the question is that racial quota, per

centage, number or balance requirements have no place

in public education. As a means, they are inappropriate

and not reasonably related to the legitimate governmental

goal of equal educational opportunity. In too many in

stances, they instead absolutely preclude attainment of

the goal. As we have previously shown, the factual result

32

of such racially motivated assignment, regardless of high-

flown theory, in all too many school systems has been but

a general deterioration of public education for all. Pupils

and teachers who find themselves assigned to schools and

excluded from others solely because of their race—in

order to achieve what some governmental official at a

given moment deems to be a suitable racial blend (seem

ingly in direct contradiction of what this Court said in

Alexander v. Holmes County, supra), are not apt to be

at their teaching and learning best. Their sense of frustra

tion is increased when they are forced to teach and study

outside of the areas of their needs, desires and aptitudes.

It is increased further when they are required to get up

earlier and arrive home later—in order to travel longer

distances to the school they have no desire to attend in

the first place. Too often the net result has been physical

withdrawal from and consequential resegregation of the

public schools, accompanied by diminished financial sup

port generally. In referring to the utter failure of such

racial quota or percentage requirements to achieve even

the immediate and improper ambition of federal officials

(he., varying degrees of racial balance), Professor Alex

ander M. Bickel states in “Desegregation, Where Do We

Go From Here?” :16

“But whatever, and however legitimate, the reasons

for imposing such requirements, the consequences

have been perverse. Integration soon reaches a tip

ping point. If whites are sent to constitute a minor

ity in a school that is largely black, or if blacks are

sent to constitute something near half the population

of a school that was formerly white or nearly all

18The New Republic, Feb. 7, 1970, pp. 20, 21. Professor Bickel,

long having been associated with the vanguard of the civil rights

movement, can scarcely be dismissed as a “racist”.

33

white, the whites flee, and the school becomes all

or nearly all-black; resegregation sets in, blacks

simply changing places with whites. They move,

within a city or out of it into suburbs, so that under

a system of zoning they are in white schools because

the schools reflect residential segregation; or else

they flee the public school system altogether, into

private and parochial schools.”

Professor Bickel asks:

“What is the use of a process of racial integration

in the schools that very often produces, in absolute

numbers, more black and white children attending

segregated schools than before the process was put

into motion?”

There is no doubt as to the fact that in other civil

rights arenas, the courts have looked upon racial quotas

with something less than approval. In the context of racial

quotas in public housing it was stated of such a require

ment in Taylor v. Leonard, 30 N.J. Super. 116, 103 A.2d

632, 633 (1954):

“. . . it is also a violation of section 1 of the Four

teenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United

States.

It is immaterial that the quota actually used

bears some relation to the percentage of Negro pop

ulation in the particular municipality.

The evil of a quota system is that it assumes

that Negroes are different from other citizens and

should be treated differently. Stated another way,

the alleged purpose of a quota system is to prevent

Negroes from getting more than their share of the

available housing units. However, this takes for

granted that Negroes are only entitled to the enjoy

ment of civil rights on a quota basis.”

Similarly (and more recently) in Colon v. Tompkins

34

Square Neighbors, Inc., 294 F.Supp. 134, 139 (S.D.N.Y.

1968), the district court declared:

“The ‘Tenant Selection Policy and Guidelines’ sub

mitted to this Court by defendant Tompkins Square

is basically sound. However, the document, in its

reference to the desirability of a ‘balanced tenant

body’ vaguely smacks of a quota system which in

the opinion of this Court, represents a constitution

ally impermissible process requiring arbitrary rejec

tion of applicants after a set quota has been met.”

In striking such a racial quota or percentage system

respecting public housing, it has been noted that quotas

based upon race bear no relationship to individual

eligibility and in reality constitute:

“. . . an arbitrary method of exclusion, a guaranty

of inequality of treatment of eligible ‘persons’ ”,

and that:

“[i]t is the individual, . . . who is entitled to the

equal protection of the laws, — not merely a group

of individuals or a body of persons according to

their numbers.” Banks v. Housing Authority, 120

Cal.App. 2d 1, 260 P.2d 668, 673-674 (1953).

Another trouble with quotas and the exclusions they nec

essarily entail was pointed out in Truax v. Raich, 239

U.S. 33, 42-43 (1915). In holding quotas respecting

alien employment rights unconstitutional under the Four

teenth Amendment, this Court observed:

“If the restriction to twenty per cent, now imposed

is maintainable the State undoubtedly has the power

if it sees fit to make the percentage less!”

The existence of racial quotas would presumably require

constant quota readjustments as the racial composition of

the body upon which the quotas are based changes, if

35

not for other reasons which might from time to time be

deemed appropriate by those who govern. The best way

to avoid the problem is obviously to avoid its beginnings.

See Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624, 641

(1942).

Returning to the field of public education, we think the

vices of racial quotas and their consequential racial

exclusions are of no different import in the constitutional

sense. We find it difficult to see any rational connection

at all between the Brown theory of psychological injury

to a black child through State-imposed racial exclusion

and the situation where a black child attends a pre

dominantly black or even all-black school because he

personally desires to do so due to his preference for com

panionship with members of his own race, because he

considers it to be the best school for his own personal edu

cational needs and desires, or because it is the school

closest to his home. In the latter situation, the dangers of

psychological injury (and denial of equal educational

opportunity) are manifestly much less than where he is

required to attend a school he doesn’t want to attend

once again simply because he is black.

Because the racial exclusions we have described are

contrary to the Constitution, they are outside the execu

tive, legislative and judicial powers of the United States.

To the extent that any court order requires them, it

is unconstitutional and a complete nullity. See e.g., Erie

Railroad Company v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64, 78-80

(1938); United States v. Walker, 109 U.S. 258, 265-66

(1883); Windsor v. McVeigh, 93 U.S. 274 (1876);

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391, 423 (1963).

36

(b) Even if a rational connection could be said to

exist between the legitimate governmental goal of pro

hibiting State-required racial separation and the im

position of racial quotas as one available means of

achieving this legitimate end, such means is a re

medial oversweep which violates transcendental coun