Mapp Et Al v Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga TN Opening Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 5, 1974

42 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mapp Et Al v Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga TN Opening Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1974. 4a2b5c41-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/8e465398-c25d-47e7-8e09-fdb92080b73d/mapp-et-al-v-board-of-education-of-the-city-of-chattanooga-tn-opening-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 74-2100, 2101

JAMES JONATHAN MAPP, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Cross Appellees,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

CHATTANOOGA, TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees-Cross Appellants.

Cross Appeals From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District Of Tennessee, Southern Division

OPENING BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellants-Cross Appellees

INDEX

Table of Authorities ....................................... n

Issues Presented for Review ............................... 1

Statement of the Case ...................................... 4

Statement of Facts ......................................... 5

ARGUMENT:

I. Areas Added To The City Of Chattanooga

By Annexation Must Be Included In The

System's Plan Of Desegregation .............. 10

II. The District Court Should Have

Required A Completely New And

System-Wide Desegregation Plan

For Chattanooga In 1973 ..................... 30

III. The District Court Should Have

Amended Its Decree So As To Include

Therein A Comprehensive Reporting

Provision .................................... 34

Conclusion .................................................. 35

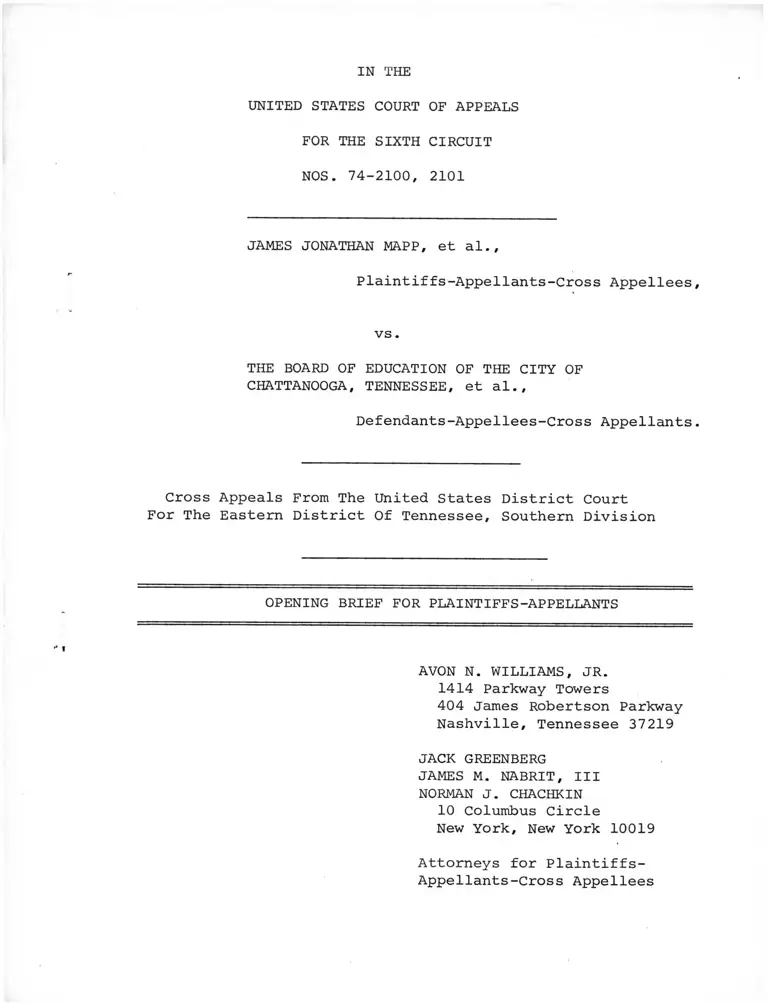

Appendix A - schematic representation of Chattanooga

Schools ....................................... la

1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Page

Berry v. School Dist. of Benton Harbor, No. 71-1957

(6th Cir., Nov. 1, 1974) ................................ 20,25,28

Bradley v. Milliken, 484 F.2d 215 (6th Cir. 1973),

rev'd on other grounds, U.S. (1974) ....... ...... 23,24

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 317 F. Supp. 555

(E.D. Va. 1970) ......................................... 15

Bowman v. County School Bd. of Charles City County,

382 F.2d 326 (4th Cir. 1967), companion case reversed

sub nom. Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ............................. 13

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ., 457 F.2d 1091

(5th Cir. 1972) ......................................... 13,31,32

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37

(4th Cir. 1968) ......................................... 31

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School Dist.,

467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972), cert. denied, 413 U.S.

920 (1973) ................................................ 18

Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile, 402

U.S. 33 (1971) ........................................... 20

Dowell v. Board of Educ. of Oklahoma City, 465 F.2d

1012 (10th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1041

(1972) .................................................... 13

Drummond v. Acree, 409 U.S. 1228 (1972) .................. 4

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange County,

465 F . 2d 878 (5th Cir. 1972) ............................ 13

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 444 F.2d 632

(6th Cir. 1971) .......................................... 17

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968) .......................................... 12,19,31

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd. 443 F.2d 1181

(5th Cir. 1971) .......................................... 27,35

11

Table of Authorities (Continued)

Cases Page

Hereford v. Huntsville Bd. of Educ., No. 74-3363

(5th Cir., Nov. 20, 1974) ............................ 13,31

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., 463 F.2d

732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1001

(1972) ................................................. 15,16,31

Kelly v. Guinn, 456 F.2d 100 (9th Cir. 1972), cert.

denied, 413 U.S. 919 (1973) .......................... 20

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189

(1973) ......................................... 17,19,21,28,32

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Bd., 444 F.2d 1400

(5th Cir. 1971) ....................................... 27

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ...... 20

Mapp v. Board of Educ., 477 F.2d 851 (6th Cir.), cert.

denied, 414 U.S. 1022 (1973) ......................... 1

Medley v. School Bd. of Danville, 482 F.2d 1061

(4th Cir. 1973), cert. denied, 414 U.S. 1172 (1974).. 24

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 391 U.S.

450 (1968) ............................................. 12,30

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 427 F.2d 1005

(6th Cir. 1970) ....................................... 13

Newburg Area Council v. Board of Educ. of Jefferson

County, 489 F.2d 925 (6th Cir. 1973), vacated and

remanded on other grounds, __ U.S. __ (1974) ....... 16,31

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 466 F.2d

890 (6th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 410 U.S. 926

(1973), vacated and remanded on other grounds,

412 U.S. 427 (1973) ................................. 13,15,31

Raney v. Board of Educ. of Gould, 391 U.S. 443

(1968) ................................................ 27

Sloan v. Tenth School Dist. of Wilson County, 433 F.2d

587 (6th Cir. 1970) ................................... 21,25,35

- iii -

Cases Page

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971) ............................... 26,27,28,29,36

United States v. Aluminum Co. of America, 91 F. Supp.

333 (S.D.N.Y. 1950) ................................ 14

United States v. DuPont deNemours & Co., 366 U.S.

316 (1961) ......................................... 14

United States v. Hinds County School Bd. 433 F.2d

611 (5th Cir. 1970) ................................ 35,36

United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., 334 U.S.

131 (1948) ......................................... 20

United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of Educ.,

497 U.S. 484 (1972) ............................... 23,24

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 467 F.2d 848

(5th Cir. 1972) .................................... 18

United States v. Union P.R. Co., 226 U.S. 470

(1913) ............................................. 14

United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., 391

U.S. 244 (1968) ............................... 21

Wright v. Board of Public Instruction of Alachua

County, 445 F.2d 1397 (5th Cir. 1971) ............. 27

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, 407

U.S. 451 (1972) 23,24

Statute

§ 803, Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C.A.

§ 1653 ........................................ 4

Table of Authorities (Continued)

IV -

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 74-2100,-2101

JAMES JONATHAN MAPP, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Cross Appellees

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

CHATTANOOGA, TENNESSEE, et al..

Defendants-Appellees-Cross Appellants

Cross Appeals From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District Of Tennessee, Southern Division

OPENING BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Issues Presented For Review

These cross appeals are taken from Orders entered by the

District Court in proceedings which followed this Court1s

affirmance and remand, Mapp v. Board of Educ., 477 F.2d 851

(6th Cir.), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1022 (1973), and which were

occasioned by the filing of a "Motion for Further Relief" by

defendant Chattanooga Board of Education. The trial court

denied both the defendant School Board's motion and also certain

post-hearing alternative motions of the plaintiffs. The Board

of Education's appeal, No. 74-2101, seeks review of the District

Court's refusal to permit it to amend its plan of desegregation

in the manner set forth in its Motion for Further Relief. The

issues on the plaintiffs' cross-appeal, briefed herein, are as

follows:

1. When a school system has never fully implemented a

system-wide desegregation decree and has not therefore achieved

unitary status, nor maintained such status for a period of time

sufficient to indicate that the decree is effective, is it

proper to exclude from the operation of the desegregation plan,

areas annexed to the school system (either after the framing of

the decree but before its full implementation, or during the

initial stages of compliance therewith) which are overwhelmingly

white, when schools serving such annexed areas will thereby have

student populations substantially disproportionate to the system-

wide racial composition? 2

2. in light of the evidence reflecting the lack of success

even of those portions of the 1971 desegregation decree which

were implemented, and the significant change in demography of the

Chattanooga school system between entry of that decree and the

1973 hearing, did not the District Court err in refusing to order

the preparation and implementation of a new, comprehensive, and

2

effective desegregation plan for the entire Chattanooga school

system?

3. Is not the District Court's decree inadequate because it

contains only a vague, virtually voluntary, reporting provision?

Statement of the Case

In 1971, the District Court entered a decree approving a

Chattanooga school board-submitted desegregation plan and

requiring its implementation as soon as, and to the extent that,

transportation facilities became available (329 F. Supp. 1374

[E.D. Tenn. 1971]). Thereafter, the District Court granted a

stay pending appeal of so much of its Order as might require the

transportation of pupils, acting pursuant to its interpretation

of § 803 of the Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C.A. § 1653

(341 F. Supp. 193 [E.D. Tenn. 1972]). Compare Drummond v. Acree,

409 U.S. 1228 (1972).

That stay remained in effect until this Court, en banc, in

1973 determined cross-appeals which had been taken from the

1971 decree. (The school board had contended it was under no

legal obligation to act affirmatively in order to bring about

any greater desegregation of the Chattanooga public schools than

had existed prior to the 1971 decree; plaintiffs contended that

the board's desegregation plan was inadequate and discriminatory.)

This Court affirmed the judgment of the District Court.

4

At the time that the mandate of this Court issued, the

Chattanooga School Board had put into effect portions of the

desegregation plan incorporated into the District Court's 1971

decree. Rather than proceeding to implement the remainder of the

plan in September, 1973, however, the Board in August of that

year filed a "Motion for Further Relief" which indicated that,

in light of demographic changes in Chattanooga between 1971 and

1973, that plan was no longer expected to be effective. By its

motion, the Board sought to implement a new plan, the object of

which would have been to maintain a limited number of Chattanooga

schools with a "viable racial mix" (majority white), while

1/assigning other students to virtually all-black schools (A. 8-30).

Plaintiffs filed objections to the Board's proposal, and

following a hearing the District Court denied the Board's request

and ordered full implementation of its 1971 decree. The Board

appeals from this denial.

The Court's Order also granted certain relief which had not

been sought either by the plaintiffs or by the Board: it directed

that the Board, in its discretion, might make zone changes affecting

areas annexed to Chattanooga or zones contiguous to such annexed

areas. Plaintiffs thereupon filed a timely motion to amend the

1/ Citations are to the single-volume Appendix on this appeal.

5

judgment so as to require that areas annexed to the City of

Chattanooga be included in the desegregation plan through

modification, for a new trial, or for further relief so as to

require the development and effectuation of a new plan of

desegregation for the city's public schools. Plaintiffs cross

appeal from the denial of their post-judgment motions.

Statement of Facts

The prior history of this case is well known to this Court,

2/

and will not be repeated here. Facts relevant to this appeal

begin with a description of the posture of this case at the time

it was last remanded by this Court.

During the 1971-72 and 1972-73 school years, while appeals

were pending here, the Board of Education "implemented" those

parts of its 1971 plan which did not require additional pupil

3/

transportation. The term "implemented" is used advisedly, since

some parts of the “plan" which were "put into effect" called for

2/ See the reported opinions herein: 295 F.2d 617 (6th Cir. 1961);

203 F. Supp. 843 (E.D. Tenn. 1962), aff'd 319 F.2d 571 (6th Cir. 1963)

373 F .2d 75 (6th Cir. 1967); 274 F. Supp. 455 (E.D. Tenn. 1967); 329

F. Supp. 1374 (E.D. Tenn. 1971), 341 F. Supp. 193 (E.D. Tenn. 1972),

aff1d 477 F .2d 851 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1022 (1973).

3/ The city school board was already providing home-to-school busing

in areas annexed from surrounding Hamilton County, such as RiVermont

and Amnicola (see schematic representation of school locations in

Appendix A, infra p. la, which does not, of course, represent

topographical characteristics except for the river).

6

the unaltered continued operation of racially identifiable schools

with the same zones they had before (e.£., Elbert Long Elementary

and Jr. High Schools). The net results during the 1972-73 school

year were as follows: 63% of all black elementary students, 53%

of all black junior high students, and 59% of Chattanooga's black

high school pupils, remained in virtually all-black schools

(A. 147-48). At the same time, 59% of all white elementary and

66% of white junior high school students were in schools at least

78% white (A. 148-49). 60% of Chattanooga's schools remained

grossly identifiable by race in this fashion.

Between 1970-71 (the school year whose enrollment data were

the basis for the projections offered when the 1971 plan was

developed) and 1972-73, the Chattanooga school system continued

to lose both white and black student enrollment; due to differential

losses, the percentage of white pupils declined from 51 to 43 (A.

20; see A. 45). Pupil population declined in areas unaffected

by the partial implementation of the 1971 plan, as well as in

those serving schools with altered or paired zones (A. 46, 124, 152)

and was paralleled by a disparity in the issuance of housing

permits which heavily favored the county (A. 82-83, 340-41).

Although this demographic change altered the specific racial

proportions which could have been anticipated to result from

implementation of the remaining pairings and rezonings of the 1971

plan, it would not have produced school populations disproportionate

7

to the new system-wide ratio, in most instances (A. 203-05).

However, heavily white schools called for under the 1971 plan

were even more glaringly disporportionate than had been anticipated

when the decree was entered, in light of the changes.

The matter was further complicated by the effect of annexa

tions to the City of Chattanooga. Between 1971 and 1973, two

areas were taken into the city from Hamilton County: one which

encompassed an existing county school building (Hillcrest) and

one which did not ("Area 10D" adjacent to the city's eastern

boundary, and to the Elbert Long elementary and junior high school

zones). The Board's Motion for Further Relief, in addition to

seeking a general modification of its plan in the direction of

5/

greater segregation, proposed the following disposition of

these heavily white areas, for school assignment purposes:

4/ At the high school level, the 1971 plan had proposed zoning

the four regular academic schools (Brainerd, Chattanooga, Howard and

Riverside) so as to assign a 25% white minority at each of the

formerly black schools. Dr. Stolee had testified in 1971 that such

a plan would lead to resegregation and the relocation of white

families, and he therefore favored a more even distribution of

students among the schools (the system was 51% white at that time).

Unfortunately, the Board's plan did not work; Riverside and Howard

have been over 95% black since the 1971-72 school year.

5/ The nature and effect of the Board's proposed modifications will

be the subject of dispute between the parties in connection with

the Board's appeal, No. 74—2101, and it will not be further described

herein, except to note that it proposed the retention of eight

elementary, four junior high, and two high schools with all-black

student bodies (A. 42).

8

maintain the existing Hillerest zone for elementary students

(96% white); and add Area 10D to the Elbert Long zone (82% white)

(A. 15). Although the District Court rejected the Board's attempt

to change its 1971 plan, the court did approve its proposals for

the Hillerest and 10D annexed areas.

The parties also presented considerable descriptive testimony

at the 1973 hearing about additional, overwhelmingly white areas

of Hamilton County which were due to be annexed to the city (e.£.,

A. 48-54, 61-62, 349-52). Although the Board had not requested

such relief in its Motion, and although the school system had not

yet developed recommendations for assignment of pupils in these

areas upon completion of the annexation process (A. 51-67), the

District Court nevertheless added to its Order the following

provisions:

The Board may at any time effect changes in school

attendance zones under the following circumstances:

. . . (c) where such changes involve the alteration

of school attendance zones to include contiguous

annexed areas; and (d) where school attendance zones

are created wholly within newly annexed areas.

(A. 432-33, 436).

Since entry of the decree, additional territory has been added to

the city school district; pursuant to these provisions of the

Court's ruling, the Board has retained their isolated, predominantly

white enrollment characteristics despite the large number of

predominantly black schools which it operates in the older part

6/

of its system, (a . 483-89) and despite the fact that it furnishes

6/ With the latest annexations, Chattanooga's overall school

population is again majority whiteo (A. 430).

transportation to pupils in such annexed areas (A. 48, 80-83,

90) .

Plaintiffs' objection to the provision for annexed areas to

be exempted from operation of the Chattanooga desegregation plan,

to the continued approval of the 1971 desegregation plan —

particularly at the high school level — and to the failure of

the court to include a comprehensive reporting requirement, were

specified in timely post-judgment motions and supporting documents

(A. 438-53; see ici., at 450-64) . These contentions were summarily

rejected by the District Court as being "without merit" (A. 467).

This appeal followed.

ARGUMENT

I

Areas Added to the City of Chattanooga

By Annexation Must Be Included•in the

System's Plan of Desegregation

The error committed by the District Court in not requiring

that areas annexed to the Chattanooga school system be desegregated,

along with the other public schools of the district, is typified

by its ruling with respect to the Hillcrest and Area 10D annexa

tions. At the time the city became responsible for providing

educational services in these regions, no system-wide desegregation

V

had ever taken place in Chattanooga. For purposes of measuring

7/ A plan which purported to provide system-wide relief was approved

by the District Court in 1971 but was never fully implemented.

See pp. 6-7, supra.

10

compliance with the Fourteenth Amendment, therefore, the school

system was in the same position as it had been the day after this

lawsuit was initially filed. There had been a systematic

Constitutional violation which had never been remedied, the

effects of which had never been eliminated; plaintiffs were

entitled to a system-wide remedy which would, at the time of its

effectuation, extirpate the vestiges of segregation from all of

Chattanooga's schools. This demand of the law was clearly not

satisfied by the approval of a plan which creates heavily black

schools in one part of the system, and heavily white schools in

another, making no attempt whatsoever to alter the racial

identifiability of the facilities.

Moreover, the District Court's decree erects serious road

blocks to the successful functioning of the very Chattanooga

desegregation plan of which it directs implementation. For it

creates, and insures the future creation and perpetuation of, a

ring of suburban, heavily white, "neighborhood" schools — to

which white students may nevertheless continue to be bused at

public expense — within a school system, the remainder of whose

schools have become increasingly black. The result is a built-in

incentive toward resegregation. One need not have extraordinary

psychic powers in order to foresee the accelerated relocation of

Chattanooga's white population within newly annexed areas of the

city, leaving the "core city" schools ever more heavily black.

11

Thus does the District Court's "desegregation" decree work

substantial mischief.

Although the District Court fails to articulate any legal

kasis for its ruling, it is possible, based upon comments made

by the court (orally and in its opinions), to examine some of

the mistaken notions upon which the court may have rested its

decision:

1. The District Court may have proceeded on the assumption

that entry of its 1971 decree sufficed to create a unitary school

system in Chattanooga, and for that reason, it had no concern

with changes affecting schools covered by its decree, or schools

added to the system by annexation since issuance of the ruling.

("The plan submitted by the Board and approved by the Court in 1971

was addressed to this problem and remedied the constitutional

defects remaining in the system" [A. 429].) Such an approach

conflicts with applicable legal principles.

(a) It is settled law that a unitary school system

is established only when a desegregation plan works in practice,

and not merely on paper. This cardinal tenet of school desegrega

tion law underlies all modern decisions, starting with the Supreme

Court's rejection of ineffective free choice plans in Green v.

County School Bd. of New Kent County. 391 U.S. 430 (1968) and

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson. 391 U.S. 450 (1968). It

has long been given regular application by this Court. E.g.,

12

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 427 F.2d 1005 (6th Cir.

1970); Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis. 466 F.2d 890

(6th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 410 U.S. 926 (1973), vacated and re

manded on other grounds, 412 U.S. 427 (1973). Decrees which seemed

satisfactory have frequently been reopened and altered when, due

to population movement, withdrawal, or for other reasons, projected

results have not materialized. E.g., Hereford v. Huntsville Bd.

of Educ., No. 74-3363 (5th Cir., Nov. 20, 1974), typewritten slip

op. at p. 2: "We view this case as presenting no more than a

motion in the district court for further relief in a typical school

desegregation case where modification is indicated because of lack

of success." [Emphasis supplied]. Accord, Ellis v. Board of

Public Instruction of Orange County, 465 F.2d 878 (5th Cir. 1972);

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ., 457 F.2d 1091 (5th Cir. 1972);

Dowell v. Board of Educ. of Oklahoma City, 465 F.2d 1012 (10th Cir.),

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1041 (1972). Entry of the District Court's

1971 decree in this case, therefore, cannot be viewed as some sort

§/

of legally talismanic act which circumscribed the further

jurisdiction and responsibility of the court to see to it that

Chattanooga actually established a unitary system.

This is all the more so in light of the fact that the 1971

decree was never fully effectuated, because of the District Court's

stay. Under these circumstances, the court was required to take

8/ Bowman v. County School Bd. of Charles City County. 382 F.2d 326,

333 (4th Cir. 1967)(Sobeloff, J., concurring), companion case rev'd

sub nom. Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, supra.

13

a fresh look at the Chattanooga system, as it actually existed

and functioned at the time system-wide relief was to be implemented.

As in antitrust cases, the decrees of a court of equity speak to

conditions actually existing at the time of their entry,

irrespective of the more limited, or different, circumstances

which may have prevailed at the time of the original violation.

E.g., United States v. Aluminum Co. of America. 91 F. Supp. 333,

339 (S.D.N.Y. 1950); United States v. Union P.R. Co., 226 U.S. 470,

477 (1913); United States v. DuPont deNemours & Co., 366 U.S. 316,

331-32 (1961).

By mechanically calling for the defendants merely to finish

up the 1971 plan, and removing from its review or consideration

all future additions of territory and schools to the Chattanooga

system, the District Court abdicated its responsibility to insure

the establishment of a unitary system in practice, as well as

on paper.

(b) The District Court's reliance upon its 1971 ruling

may also indicate an assumption that its Constitutional

responsibility and jurisdiction were limited to the Chattanooga

system as constituted at the time that decree was entered,

irrespective of the fact that the 1971 plan was not fully

implemented. Such an interpretation of the law is likewise

erroneous.

14

In numerous school desegregation cases, the contours and

characteristics of school districts have been altered by a

variety of forces (including the addition of territory by

annexation) between the initial finding of Constitutional violation

and implementation of an effective remedy. in such instances,

judicial decrees have not been limited to separate portions of

the school systems. In Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of

Educ., 463 F.2d 732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1001 (1972),

for example, individual actions against the City of Nashville and

against Davidson County were consolidated after the political

subdivisions were merged into one metropolitan government. Never

theless, the desegregation plan ultimately ordered by the district

court and approved by this Court did not treat the former systems

independently. Similarly, this Court directed formulation of a

comprehensive desegregation plan for Memphis in Northcross v.

Board of Educ., supra, and that plan included all areas within

the City of Memphis at the time of its submission, see Civ. No.

3931 (W.D. Tenn., May 3, 1973), aff'd 489 F .2d 15 (6th Cir. 1973),

cert, denied, 416 U.S. 962 (1974); see also, No. 74-2232, pending.

And the district court's interim and final orders in the Richmond,

Virginia case, for further example, required complete desegregation

of schools in a large area added to the city in 1970, Bradley v.

School Bd. of Richmond, 317 F. Supp. 555 (E.D. Va. 1970); 325 F.

Supp. 828 (E.D. Va. 1971).

15

In short, annexations — like other demographic changes

occurring before effective and complete desegregation takes

place, e.g., Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ.. supra,

463 F.2d, at 732; Newburg Area Council v. Board of Educ. of

Jefferson County, 489 F.2d 925, 931 (6th Cir. 1973), vacated and

remanded on other grounds, __ U.S. __ (1974) — must be taken

account of in school desegregation orders.

(c) Finally, the District Court's indifference to the

composition of the schools in the annexed areas cannot be justified

on the basis of its 1971 Order for two additional and different

reasons. First, the intervening demographic and other changes

which have taken place have significantly weakened the factual

basis for the Court's approval of the Board plan in 1971. Schools

which were a part of the Chattanooga system in 1971, and which

were not substantially affected by the Board plan (such as, for

example, Elbert Long), now appear far more substantially dis

proportionate in their racial composition than may have been the

case at that time. Schools proposed for closure in the 1971 plan,

with their students assigned so as to further desegregation (e.g.,

Lookout Jr. High) were retained. It was thus clearly error for

the District Court to affirm its 1971 decree without revisiting

the factual bases for its approval.

16

intervening decisions have undercut the legal analysis upon which

the District Court's 1971 approval of the Board's plan rests.

Cf. Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 444 F.2d 632, 634 (6th

Cir. 1971) ("We believe, however, that Knoxville must now conform the

direction of its schools to whatever new action is enjoined upon

it by the relevant 1971 decisions of the United States Supreme

Court"). We discuss some of these developments below; but we

should like to emphasize at this point one of the most significant.

The District Court in 1971 conducted a school-by-school analysis

of the Chattanooga system, determining that heavily white schools

such as Dalewood and Long were Constitutionally acceptable since

it could not find evidence of direct school board manipulation

to establish or preserve their uniracial character. 329 F. Supp.,

at 1382, 1384. That analysis, we submit, failed to take account

of the principle which has been enunciated by the Supreme Court

in Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189 (1973), that

"racially inspired school board actions have an impact beyond the

particular schools that are the subjects of those actions," id., at

203. As the Court put it (in language unexpectedly

appropriate to this case):

[Segregative acts which] have the clear effect

of earmarking schools according to their racial

composition . . . together with the elements of

student assignment and school construction, may

have a profound reciprocal effect on the racial

composition of residential neighborhoods within

Second, developments in school desegregation law and

17

a. metropolitan area, thereby causing further

racial concentration within the schools.

413 U.S., at 202. See generally, id., at 201-03; United States

v * Texas Educ. Agency. 467 F.2d 848, 888 (5th Cir. 1972);

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School Dist.. 467 F.2d

142 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 413 U.S. 920, 922 (1973).

We thus conclude that entry of the Orders now under

consideration can in no way be justified by reference to the

earlier ruling of the court.

2. The District Court may have assumed that relief in this

school desegregation case was limited to ameliorating segregative

conditions at individual schools shown to have been directly

caused by the activities of these defendants and their predecessors

in office, as indicated by these comments:

- . . it's my further recollection that

in the hearings two and a half years ago

that the evidence identified one school

after another that had been built and

located for the purpose of establishing

and maintaining a segregated school system

back at the time when Chattanooga was

operating dual school systems.

Now, as I understood, it was our respon

sibility to try to eliminate the segre

gation that was caused by that lawfully —

it was lawfully imposed at the time it

was done, but since it's been held to be

unconstitutional. . . .

What does that have to do — what I have

difficulty understanding is what does

18

that have to do with the elimination of

the dual school system that the School

Board built and operated up until 1962

or '64? . . .

[The School Board] should look and see

whether each school now has any conse

quences in that school that resulted

from their having operated it as a

segregated school back in 1961 and prior

to that time. . . .

Now, the Supreme Court has said that equal

protection of the law means that we must

remove all vestiges of segregation that were

imposed by reason of the past actions of

the Board or any more recent actions that

caused segregation. [A. 222, 223, 224, 225].

Proceeding upon this hypothesis, the court would naturally have

excluded areas not a part of the historical Chattanooga official

dual system from its consideration. However, this approach finds

no support in the decisions of the United States Supreme Court

or of this Court.

(a) Whatever may have been the proper characterization

of the Constitutional violation in this case (but see Keyes v.

School Dist. No. 1, Denver, supra, and discussion thereof at pp. 17-

18 above), the remedial authority and responsibility of a federal

district court in a school desegregation case is broad. "Root and

branch," Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, supra,

391 U.S., at 437-38, or "all-out," Keyes, supra, 413 U.S., at 214,

desegregation of the school system is required. Racially identifi

19

able schools — the hallmark of the dual system — must be

eliminated by any successful, adequate remedy. cf. Kelly v.

Guinn, 456 F.2d 100, 109-110 (9th Cir. 1972), cert, denied,

413 U.S. 919 (1973). "Having once found a violation," Davis v.

Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile, 402 U.S. 33, 37 (1971), the

District Court has "not merely the power but the duty to render

a decree which will . . . so far as possible eliminate the

discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like discrimina

tion in the future." Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145,

154 (1965).

That the schools which must be affected by such a decree may

include facilities newly added to the system since the finding

of Constitutional violation is not cause for concern, but rather

is consistent with the application of settled equitable principles.

In antitrust law, for example, in order to remedy unlawful

practices "equity has the power to uproot all parts of an illegal

scheme — the valid as well as the invalid." United States v.

Paramount Pictures, Inc., 334 U.S. 131, 148 (1948). Thus, it

would be error to limit the operation of a remedial decree to the

Chattanooga school system as it existed in 1971, ignoring the

9/ See Berry v. School Dist. of Benton Harbor, No. 71-1957

(6th Cir., Nov. 1, 1974), slip op. at p. 6 , n. 4 and accompanying

text.

9/

20

fact that a pattern of annexations from Hamilton County would

very rapidly lead to the reestablishment of racially identifiable

10/

schools in the system.

(b) This record contains affirmative evidence which

negates any assumption that state action was unrelated to the

composition of the Hamilton County schools which have recently

been made a part of the Chattanooga school system.' Although it

is presently operating pursuant to an HEW-approved pupil assign

ment plan, the County formerly maintained dual overlapping zones

for black and white students as did Chattanooga (A. 54-63). Thus,

viewing the Chattanooga board as the successor to the Hamilton

County board, the Fourteenth Amendment imposes affirmative

desegregation obligations even with respect to the annexed

territory.

(c) A narrow approach which limits the remedial

11/obligation to only one portion of the Chattanooga district

10/ Similarly, in antitrust cases, the court's obligation is to

"prescribe relief which will terminate the illegal monopoly, deny

to the defendants the fruits of its statutory violation, and ensure

that there remain no practices likely to result in monopolization

in the future,11 United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., 391

U.S. 244, 250 (1968)(emphasis supplied). Cf. Sloan v. Tenth School

Dist. of Wilson County, 433 F .2d 587 (6th Cir. 1970).

11/ Absent a finding that the violation was limited to a physically

or otherwise separable portion of the school district, see Keyes,

supra, 413 U.S., at 203, 213.

21

undercuts the Constitutional requirement of a workable, effective

plan. At the time it entered its Orders in 1973, the District

Court was presented with an elaborate argument by the Chattanooga

Board (in support of an effort to return to segregation) to the

effect that white population movement within and out of the City

of Chattanooga had seriously interfered with the expected success

of those portions of the 1971 plan which the Board had implemented.

Approval of the Hillcrest zone, and the assignment of Area 10D

students to Elbert Long, when those students were being transported

to school anyway pursuant to the plan of services filed by the

City in its annexation case (A. 368) could only exacerbate the

tendency of whites to relocate in the suburbs from which blacks

were largely excluded by discrimination (A. 417). Common sense

alone should have told the District Court that exclusion of

annexed areas from the operation of the plan would doom it. The

testimony was to that effect (A. 383-85).

The District Court's action was equivalent to subdividing

Chattanooga into predominantly black and predominantly white

subsystems — an action whose results were certain to be the

forestalling, rather than the advancement, of desegregation. The

Supreme Court has indicated the unacceptability of such a course

of action:

Nor does a court supervising the process of

desegregation exercise its remedial discretion

responsibly where it approves a plan that, in

the hope of providing better "quality education"

to some children, has a substantial adverse effect

22

upon the quality of education available to

others. In some cases, it may be readily

perceived that a proposed subdivision of a

school district will produce one or both of

these results.

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451, 463

(1972). And while the District Court was undoubtedly correct

in rejecting the school board's proposals despite the argument

that reestablishment of segregated schools in the "core city"

would counteract the withdrawal of white students from the public

system (see discussion infra), see United States v. Scotland Neck

City Bd. of Educ., 497 U.S. 484, 491 (1972), it erred in not

exercising its remedial discretion to the fullest extent and in

such a manner as would both maximize desegregation and eliminate

opportunities for resegregation within the areas under the

jurisdiction of the Chattanooga school board, see Wright, supra,

407 U.S., at 464-65.

This case presents an appropriate, perhaps ideal, opportunity

for the application of the sound remedial principles enunciated

by this Court in Bradley v. Milliken, 484 F.2d 215 (6th Cir. 1973),

rev1d on other grounds, __ U.S. __ (1974). For, unfettered by

considerations of school district boundaries, federalism, or

state law, it involves a plan ostensibly intended to remedy a

Fourteenth Amendment violation which proposes to create and

maintain "[predominantly] black school[s] . . . immediately

surrounded by practically all white suburban school[s] . . . with

23

[a predominantly] white majority population in the total [district]

area," 484 F.2d, at 245. The school population disproportions

which are proposed to be maintained are, with little dispute,

so great as to render unacceptable any plan which purported to

effect them. See, e.g., Medley v. School Bd. of Danville, 482

F.2d 1061 (4th Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1172 (1974).

Many of the additional factors which motivated this Court in

Bradley v. Milliken to direct that district boundary lines be

crossed, are also present here, such as the differential provision

of home-to-school transportation between annexed and non-annexed

areas. Surely, then, these circumstances warrant application

of the meaningful remedy principles of Bradley and the inclusion

in the plan of territory annexed to the Chattanooga system.

3. The District Court may have shaped its decree as it

did in order to prevent further loss of white-students from the

Chattanooga system, for it evidenced concern over the demographic

changes in the district but stated:

Annexation, and not resegregation of the

schools, is the obvious answer to this loss

of affluence as well as a declining residential

population and a declining school enrollment.

It should be noted in this regard that next year,

as a consequence of recent annexations, the

Chattanooga Public Schools will have an all time

high student enrollment as well as again having

a majority of white students.

(A. 430). While the Court paid lip service to the principles of

Wright, supra and Scotland Neck, supra, which reject the prevention

24

of white flight as a justification for limiting desegregation

(A. 430-31), its Orders ultimately embodied a mechanism whereby

the Chattanooga school system could retard white withdrawal from

its system by limiting the number of schools within that system

which would be desegregated.

The only justification offered by the District Court for

this material incentive to resegregation, is contained in a

footnote (A. 431) labelling such resegregation as may occur,

"de facto." Not only does this simplistic approach ignore the

responsibility of board and court to implement an effective,

workable plan by avoiding foreseeable resegregation, but it

is also an inaccurate statement of the law. In this Circuit the

action of the Chattanooga Board in annexing heavily white areas

without altering their zone lines so as to alleviate obvious

racial imbalances would, without regard to the long history of

official segregation in the State of Tennessee and the City itself,

constitute evidence of intentional, cte jure segregation. Berry v.

School Dist. of Benton Harbor, supra, slip op. at p. 7? cf. Sloan

v. Tenth School Dist. of Wilson County, supra, 433 F.2d, at 589,

590 (6th Cir. 1970) (dicussing reciprocal school-residential

incorporation of institutional segregation).

For these reasons, it would be impermissible for this Court

to affirm the judgment below on the theory that the District Court

was, with benign intent, attempting to prevent "white flight"

from Chattanooga.

- 25 -

4. Finally, in an effort to cover all conceivable bases

for the District Court's ruling, we consider the possibility

that (although it did not specifically advert to it) the Court

thought this case was governed by Section VI of Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 31-32 (1971).

The relevant portions of the Supreme Court's opinion provide:

At some point, these school authorities and

others like them should have achieved full

compliance with this Court's decision in

Brown I. The systems will then be "unitary"

in the sense required by our decisions in

Green and Alexander.

It does not follow that the communities served

by such systems will remain demographically

stable, for in a growing, mobile society, few

will do so. Neither school authorities nor

district courts are constitutionally required

to make year-by-year adjustments of the racial

composition of student bodies once the affirma

tive duty to desegregate has been accomplished

and racial discrimination through official

action is eliminated from the system. This does

not mean that federal courts are without power to

deal with future problems; but in the absence

of a showing that either the school authorities

or some other agency of the State has deliberately

attempted to fix or alter demographic patterns

to affect the racial composition of the schools,

further intervention by a district court should

not be necessary.

The Supreme Court's language does not fit this case, so as

to justify the District Court's abstention from "further

intervention," for several reasons.

(a) The prerequisite established by the Supreme Court

the achievement of "full compliance" — must be understood in

26

the context of the requirements of effectiveness and workability

which we have previously discussed. This is the reason for

the retention of jurisdiction beyond entry of a decree approving

a plan, see, e.g., Raney v. Board of Educ. of Gould, 391 U.S.

443 (1968); Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 443 F.2d 1181

(5th Cir. 197.1) ; Wright v. Board of Public Instruction of Alachua

County, 445 F.2d 1397 (5th Cir. 1971); Lemon v. Bossier Parish

School Bd., 444 F.2d 1400 (5th Cir. 1971). Since the 1971 decree

calling for sysrem-wide relief was never put into effect, and

since its Constitutional adequacy is open to serious question

in light of intervening changes of fact and law’, it can hardly

be said that Chattanooga has reached "full compliance."

(b) The eventuality assumed in this passage from the

Supreme Court's opinion in Swann is that demographic changes take

place within a school system wholly without the connivance or

participation of state agencies or officials. Once again, that

is hardly the situation which the court confronted in this case.

First, as Dr. Stolee predicted in 1971, the ineffectual high

school plan adopted by the Board in 1971 could be expected to

prod\ice exactly the sort of demographic change which took place

in Chattanooga (A. 403-06). Second, the School Board members,

school officials and attorneys spent two years making self-fulfilling

prophecies about the inevitability of "white flight" in the event

of desegregation (See A. 88-89, 240-41, 312-14, 329-31, 334-38,

385-86). Third, the action proposed by the Board and the District

27

Court with respect to assignments of pupils in the annexed areas

is the equivalent of an extensive, periphery or suburban school

construction program which cannot but have a marked effect on

residential patterns. See, Swann, supra, 402 U.S., at 20-21;

Keyes, supra, 413 U.S., at 202. For these reasons, then, it

would not be accurate to consider recent demographic changes in

Chattanooga as being so divorced from discriminatory state actions

as to bring the system within the purview of Part VI of Swann.

(c) Finally, the quoted language appears at the

conclusion of the Court's decision in Swann in order to emphasize

that full and effective compliance by a school district does not

require constant redrafting of a plan to maintain perfect racial

balance, or to compensate for minor demographic shifts. The

Court was not faced with, nor did it purport to establish legal

rules for, determining when a school board's refusal to act to

relieve segregation may amount to a violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Subsequently, in Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver,

supra, the Court endorsed the thesis that school boards are

Constitutionally responsible for the natural or foreseeable

consequences of their actions, or failures to act. 413 U.S. 189,

aff1g 303 F. Supp. 279 (D. Colo. 1969). This Court, in Berry v.

School Dist. of Benton Harbor, supra, has recognized the justifiable

corollary principle that a decision "not to adopt new attendance

28

boundaries [for a consolidated or annexed area] in the face of

a readily discernible pattern of residential segregation" may

indicate a Constitutional violation. The principle is most

assuredly applicable to Chattanooga, and it takes the case outside

Part VI of Swann.

In conclusion, careful study of all possible grounds which

might support the District Court's action respecting annexed

areas reveals no valid ground therefor. The Court's Order

represents an abdication of its authority and duty to retain

jurisdiction to insure the establishment and operation of unitary

schools; it should be reversed and the court instructed to require

inclusion of these areas in an effective Chattanooga desegregation

plan.

i--

„

»* •

• W : -

a, > %

T

• ^

II

The District Court Should Have

Required A Completely New And

System-Wide Desegregation Plan

For Chattanooga In 1973

At the time of the 1973 hearings on the School Board's

Motion for Further Relief, the District Court had given only

tentative approval to the high school zoning portion of the

1971 plan — the only grade level at. which the plan had been

"fully implemented" (A. 115-17, 125). Although the court had

indicated that its ultimate endorsement of the high school plan

would depend upon the results attained thereunder (A. 125), and

despite the uncontested failure of the plan, in actual operation,

to alter the all-black character of Riverside or Howard High

Schools, the court nevertheless concluded after the evidentiary

hearing on the Boeird's motion that the plan had made Chattanooga's

high schools "unitary."

Such a conclusion can hardly be supported under any reasonable

interpretation of the law. The high school plan simply did not

work at all; not for the first three minutes, days, weeks, months

or years after it was put into effect. When a desegregation plan

— particularly one which relies upon zoning — is such a total

flop, the courts have uniformly required the development and

implementation of a new method which is more likely to produce

actual results. Monroe v. Board of Coram1rs of Jackson, 427 F.2d

30

<-

1005 (6th Cir. 1970); Northcross v. Board of Educ, of Memphis,

466 F.2d 890 (6th Cir. 1972); Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ.,

supra; Hereford v. Huntsville Bd. of Educ., supra; Brewer v.

School Bd. of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968).

The District Court's lame excuse for its decision on the

high school plan: that demographic changes had resulted in

the plan's ineffectiveness, is irrelevant and unconvincing.

Since the Chattanooga school system, including the high school

subsystem, had never been adequately desegregated, demographic

changes of whatever sort or cause do not relieve the school

authorities of their continuing obligation to bring about

« jL\r~ -L. .J-C3 y v • i»iC u i U } J U ± l . t a l l J3U. • U I

Educ., supra; Newburg 2\rea Council v. Board of Educ . of Jefferson

County, supra.

To accept demographic change which totally prevents even

the momentary effectiveness of a desegregation plan, or white

refusal to attend desegregated schools which produces the same

result, is but to return to "free choice" days when the paper

promise of a plan sufficed. Just as the refusal of white students

to desegregate all-black schools by freedom of choice signalled

the unacceptability of that method of desegregation, e .q., Green

v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, supra, so the immediate

withdrawal of white students assigned under a zoning plan to

- 31 -

Riverside and Howard denotes the ineffectiveness of the plan.

Boykins v. Fairfield 13d. of Educ., supra.

Not only should the District Court have required a new

plan for assigning high school students, but it should have

ordered preparation of an entirely new and coniprehensj.ve pupil

assignment scheme for the entire Chattanooga system. As set

out above, p. 17, the 1971 District Court opinion approving the

Board's plan, and this Court's en banc affirmance thereof, were

issued prior to the decision of the United States Supreme Court

in Keyes v. School Dtst. No. 1, Denver, supra. The District

Court's analysis, upon which it determined to permit the

continuation of numerous severely d j.sproportj.onate one-race

schools, was based on the notion that segregative acts affecting

each school in the system had to be shown by plaintiffs. See

329 F. Supp., at 1381-84. That burden is not one which plaintiffs

must carry in a desegregation suit initiated in a State which never

required segregation by law, much less in one where the

affirmative obligation to terminate dual systems and uniracial

schools has existed since 1954. Keyes, supra, 413 U.S., at 200.

Thus, the legal basis upon which the District Court originally

approved the plan, and upon which this Court's affirmance may

have been based, can no longer withstand scrutiny.

Furthermore, and again as discussed above, the elementary

and junior high school portions of the 1971 plan were never fully

32

implemented in Chattanooga. During the period of the District

Court's partial stay, the underlying factual pattern against

which the sufficiency of the plan must be judged, underwent

significant alteration. Shifts in racial concentration through

residential relocation and annexation by the City of Chattanooga

worked substantial changes in the projected results which could

be anticipated (without considering the Board's further speculation

about increased "white flight") if the remainder of the 1971 plan

were implemented. Schools whose assignment zones may have been

approved because their racial composition did not seem to the

District Court in 1971 to be "substantially disproportionate"

look entirely different in relation to the 1973 Chattanooga school

system. For this reason as well, the District Court should have

reexamined the Constitutional sufficiency of the 1971 plan in

light of changed conditions and circumstances. It was not

enough to deny the Board's motion seeking greater segregation;

the District Court's obligation was to ensure the creation,

at long last, of a unitary system in Chattanooga.

Finally, of course, we have argued above that the annexed

areas must be desegregated. This, too, would require the

redrafting of the entire Chattanooga desegregation plan; and

this Court should so instruct the District Court on remand.

33

Ill

The District Court Should Have

Amended Its Decree So As To

Include Therein A Comprehensive

Reporting Provision

The 1971 plan submitted by the Chattanogga Board of

Education contained the following provision:

It is proposed that the Chattanooga Board

of Education submit to the Court a report

by October 31, 1971, based on tenth day

enrollment figures and staff assignments.

The report will encompass pertinent data

relative to plan implementation in both

student enrollment and staffing. Other

reports would be forwarded to the Court

pertaining to those specific instances in

which directions and/or positions of

compliance arise.

(Appendix in 6th Cir. Nos. 71-2006, - 2007, Vol. I, p. 112).

The 1971 decree of the District Court accepted this non-specific

virtually voluntary procedure for the submission of compliance

reports, adding only that they should be made annually (329

F. Supp., at 1388):

Paragraph VII of said amended desegregation

plan is modified to provide for the continuation

of annual reports of the continued implementation

of all approved provisions of said plan, until a

final order of compliance may be entered, copies

of said reports to be furnished counsel for

plaintiffs.

In their 1973 post-hearing motions, plaintiffs called the

inadequacy of the reporting provisions to the attention of the

District Court, and sought modification of the court's decree to

- 34 -

strengthen the reporting requirement so that the Court might

be more properly informed of the progress, or lack thereof,

in establishing a unitary system in Chattanooga. The District

Court declined to alter its orders.

The reports which the school board proposes to furnish

deal only with a small portion of the information relevant

to the continuing responsibilities of the District Court.

Notification of new construction proposals, or possible annexations,

for example, is not required. Cf. Sloan v. Tenth School Dist.

of Wilson County, supra.

mi, _ -v- A 4- 'hne r). 1-3 LlVGlv StlOl. u lC>U.C

complete and informative reporting requirement which it has

uniformly applied to school systems undergoing desegregation

during the transitional process. Hall. v. St. Helena Parish

School Bd., 443 F.2d 1181 (5th Cir. 1971); see United States

v. Hinds County School Bd., 433 F.2d 611, 618-19 (5th Cir. 1970).

We urge this Court to require the same, either m all school

cases as a matter of Circuit policy, or at the least m this

case, so that the Court and the parties may better carry out

the terms of an adequate plan and take all necessary action to

maintain a unitary school system in Chattanooga.

35

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the District

Court should be reversed, and the case remanded with instructions

to the District Court to require the submission and implementation

of a new,,updated and comprehensive desegregation plan for all

of Chattanooga's schools, including those in areas annexed to

the city since 1971 and in the immediate future, in accordance

with the remedial guidelines cf Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Bd. of Educ., supra, and the decisions of this Court; and with

the further instruction that the District Court include within

its final decree a reporting requirement similar to that set

u x i x u o u u e u o u o v • n a .x x

Respectfully submitted,

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG ■

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellants-Cross Appellees

36 -

CERTIFICATE C)F SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this daY °f December, 1974,

I served two copies of the foregoing Opening Brief for

Plaintiffs-Appellants upon counsel for the Defendants-Appellees

herein, by depositing same in the United States mail, first

class, postage prepaid, addressed as follows:

Raymond B. Witt, Jr., Esq.

.1100 American National Bank Building

Chattanooga, Tennessee 37402

37

,̂vrp\hu6

///

I

6 H0W V ■CAWWW-oc^A w

\V /

o iX R>’m u_

v ftA t-i \CG

og>f-fcC,N

X

r.fK. -

o r' ̂V ft A

O yVB';c/'1

i

• \VoCNJ~'*"-'*:~

Oc. FifTtt

o \\0m ̂ M 6

o S(A\' r*t

1 rfOPtOS^^J

c3C>Mf

X*'

'< r-C* •* U

•v ‘.'“Ne V\ U

0 uXaxcrtcQ

e\jl u <~ cX

V \volOPt̂ a

o ’ttf' «•♦£,< Pe CO ft Oc * y yjjj j i t c£

Os, t'C

C{‘-v̂

<Jy-^ P"ni

Bctû

Oesfvcc^

.AfV^R-

LttiftOSCW

OKI** v’iW-

ôw.frcN•9 i/ V*

oOV-.CN-

• ̂ T f ^ * fWt'X

«3CC9»_

1 | o (ISDAN.

\ VMU-

V ^ 0 -* yAV*. a--^-

0~rc-

n ? ■K iMvo.’d\0'i<t,f' \

4 <j Va 1 !> V* k k̂j